Persephone

PART I: Persephone 2014 | PART II: Mara, Marietta | PART III: The Unspeakable Girl: The Myth & Mystery of Kore | PART IV: D.H Lawrence & Persephone

PART I

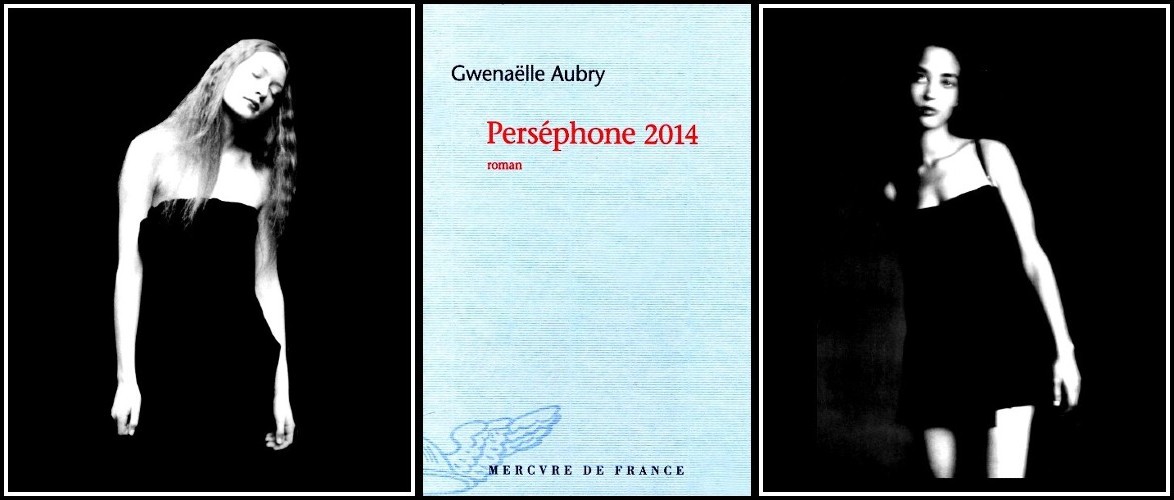

GWENAËLLE AUBRY: PERSEPHONE 2014

Author’s Presentation of the Novel

For years I lived in a myth. I wrote about this myth in a text that was always in process. Everything I was going through went into it—men, cities, books, seasons in hell, joys, rages, everything, the myth was both a vital structure and a novelistic machine that took everything in. One day I set the manuscript aside to write other novels. They have only ever encrypted it. So I returned to the matrix, went back underground. Persephone 2014 is a new point of intersection between this story (this mad old story) and mine, between the ancient and the ultra-contemporary. What happens when a myth takes over a life, pulverising it into raw passions and elementary events? What I hear of Persephone, of this very ancient, lilting voice, is the desire to be matter, the desire of a self undermined and a world turned upside down. And also, how is it possible to leave this desire behind and come back from Hell? And then, should it be left behind? And where is Hell? Does it lie in roots, magnificent devastation and silent fires? Or in surface realms, smooth forms, legitimate orders and established rites? Returning to Persephone means stubbornly continuing to investigate the secret that binds pleasure, death and writing tightly together. (G.A.)

Votive relief to Demeter and Kore, 415 BC (Getty Museum)

Gwenaëlle Aubry, Persephone 2014

CHAPTER 3: ABDUCTION

Translated from the French by Richard Jonathan

Translator’s Introduction

A hidden gem lies buried in the plethora of Persephone-themed productions: Perséphone 2014, a novel by Gwenaëlle Aubry. Where screenwriters coordinate plot points on their whiteboards, where cheap writers tick boxes on their checklists, Gwenaëlle Aubry offers us something far more interesting: an investigation of her own relation with Persephone, a confrontation between versions of herself and the mythic heroine. The result is a breath of fresh air that leaves one breathless, an intellectual high that’s experienced in the body. The kinship between fiction and the feminine, between literary art and the art of becoming, is evident. If, among the arts, the novel is supreme in its ability to provide access to another’s consciousness while expanding one’s own, then a novel true to its génie is one that shakes us up, replenishes our being and heightens our sense of being alive. Gwenaëlle Aubry does just that in Perséphone 2014. If you do not read French, however, know that at present (January 2022), the book has not been translated into English. I have therefore taken it upon myself, with the author’s kind permission, to offer you, as a foretaste of the novel, my translation of chapter 3. You can also find, on Asymptote, an excellent translation by Wendeline A. Hardenberg of five of the six sections that precede chapter 3. (R.J.)

Fragment of a votive relief, Hades Abducting Persephone, 465 BC (MET)

He laughed as he told me to tie him up. (Euripides, The Bacchae)

They say that in your case the ground opened up and he surged out of it. We don’t name him, he who is going to seize you, you and your name; him we only invoke, and in a roundabout way (master of multitudes, Commander- and Host-to-Many). It’s as if, for the others too (those who spoke your language, told your story), he was indistinguishable from his movement, all but invisible for his swiftness: surge/seize.

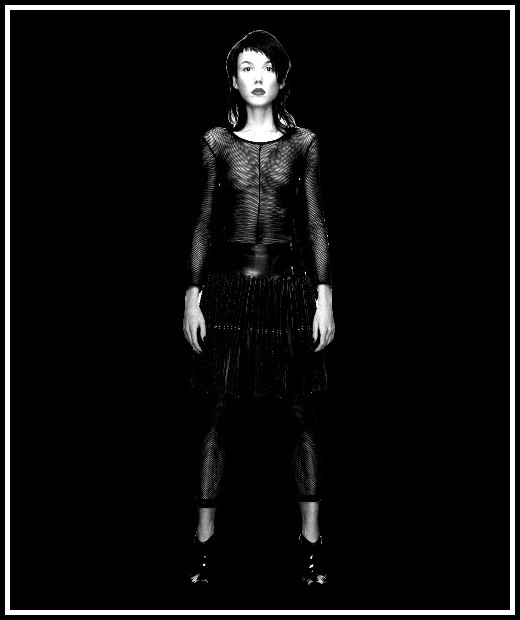

Photo: Ben Ingham

They embroider a little, they embellish, they fabulate; they speak of horses, a golden chariot, tears. They try to restrain the lightning, to encircle the void.

Photo: Jane McLeish

They also say (and I’m prone to believe it) that you screamed, that you never stopped screaming, that even when you’d already gone underground your shrill cries still resounded, but no-one, neither god nor beast nor man (no-one, except Hekate, she alone, tender of heart), heard you, or wanted to hear you. Yes, man and beast had long since vanished while the gods, impatient for prayer in their temples, remained aloof, but you, you don’t pray, you no longer have any idea what it is to pray: you, you scream.

Photo: Alex Caley

I’m looking at the fresco that tries to capture that, the lightning deed, the abduction, the instant. It’s an organic fresco, cinnabar, a lacquer of pink and malachite, where only the details, the décor, are really visible. What do I see? The wheel and the axle of the chariot, the woman (servant, witness) crouched in a corner, raising her hand in a futile gesture of supplication or surcease. And your faces, your faces too are distinct, both your head and his are crowned in red curls, a tangle of sparks; his face, half-hidden by a beard of the same red, is seen in three-quarter profile, a fine head of a he-god, disdainful, solemn, sensual, with, however, a touch of trepidation in the frank gaze; your face, so fine, a perfect oval, off kilter, imploring, shaken—but your bodies, your bodies where all is at stake, seem to be merged with the stone, on the verge of disappearing. Indeed, without that pink cloth that envelops the two of you, that falls from his shoulders to your hips, swells out and collapses into folds, without that veil you two would barely be distinguishable: one would have to look very closely to see the delicate line that traces the contours of your body, your arms raised, your girl’s wrists cuffed in gold, your belly hollowed out and on your breast, his hand.

Vergina fresco, Hades Abducting Persephone, Macedonia (Greece), 340 BC

Of what is happening in that instant (of which no-one, in truth, can be a witness: in the face of it, neither gaze nor prayer has any purchase) the bodies have already taken leave. They travel faster than the two of you, you who still cling to your faces and your names; erased by their own celerity, they are already elsewhere, already there where contours merge, leaving nothing on the wall but a trace of their incandescence.

Photo: Donald Christie

They say that in your case it happened that way. And reading again your old story, looking at the Vergina fresco (a lousy reproduction, bought in a museum shop), I recall certain details (the blazing red, the whiteness of the bodies, the restrained wrists). But what I would like to see directly (what I’ve never stopped searching for all these years) is the crack, the gaping ground, the instant you disappeared into it (I’m still there with you, we’re there together: you know that); yes, what I would like to see is that which in one blow shattered everything—time, recurrence, your prancing and gamboling, your dancer’s steps, your skill as a weaver, the texture of the works and days you once wove, and, of course, you yourself—the abstract doll-like creature you were, the irritating little idol—young girl, young goddess, it’s all the same: images, nothing but images, pure, vague, vacuous. It’s the precipice-instant when everything slipped—ploughed fields, lush meadow, girls’ laughter, surface rites—all that diurnal hell you abandoned in a scream, a scream in which (I like to believe, I remember) terror mingled with triumph.

Photo: Ben Ingham

I would like to see directly the crack that already marked you: scratch on marble, fingernail streak on waxen body, the wounding of your girlish frame. A few years before, barely out of childhood, you opened a book: Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein. I think you didn’t understand the title, you didn’t try to go beyond its music (that sound of crumpled wings), the lettering, those S’s, those L’s, that V in particular, where you saw not an initial but an animal spoor (footprint of bird on sand), a sign (open triangle). For the rest, I have no idea what you were reading: a sort of parallel state, I imagine, that led you to an elsewhere, a locus of the real where, no doubt, you sensed you belonged. I remember only that once you’d finished the book, you needed to copy a sentence from it; you did so on a scrap of paper that you pinned on your wall beside your demi-gods of the time (Marilyn, Garbo, Ziggy Stardust). I also remember the sentence (simple, neutral, elementary): ‘The idea of what she is doing does not cross her mind’.

Photo: Demon Pruner

I could laugh, scratch you again, cut the girl, cut into the vain little idol, the crazy little virgin: the fact remains that that book, that sentence, acted upon you: a very scrutable bird flight pattern, an augury of sorts, your story inscribed in it: the ball, the walk in the meadow of the two women, daughter and mother, the blonde form stretched out in the field of rye, and above all the instant, the lightning instant that leaves a hole in time.

Photo: Jane McLeish

To be abducted, ravished, was already what you wanted; your desire was manifest there, except that you are not the witness of the scene, the third person, the woman crouched in the corner of the fresco, the silhouette hidden in the rye. No, what you want is to no longer be a witness, and especially not of yourself: what you want is to have no idea what you’re doing, to no longer be able to say, or even to think: up to there, it’s me.

Photo: Kent Baker

GWENAËLLE AUBRY: PERSÉPHONE 2014

Présentation du roman par l’auteur

Perséphone, Fée Personne. Tu nommes pour moi la faille et l’élan, le massacre et le sacre, la vérité muette et les mots qui la scandent, le désir d’être matière et la forme à trouver. Tu condenses les corps que j’ai aimés et l’espace glacé qui les sépare. Les livres s’écrivent entre les corps. Ils naissent des révolutions fragiles qui bouleversent la chair et défont l’ordre des mots, de ces précaires mondes à l’envers. Je n’écris pas à la place de la vie. Et pas non plus depuis la place du mort. J’écris en écho à la souveraineté de certains instants vitaux, pour combler le manque où ils m’ont laissée, pour perpétuer leur intensité. Je ne sais pas d’autre façon d’en revenir, d’en sortir sans les trahir : farder leur matière, changer en monde ce qui gît sous les jupes de la terre, peindre un masque victorieux, écrire pour maquiller le cri en rire et le sexe en visage. (G.A.)

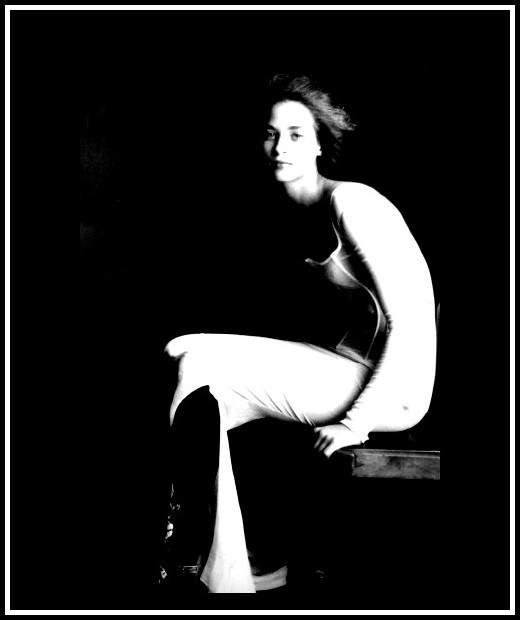

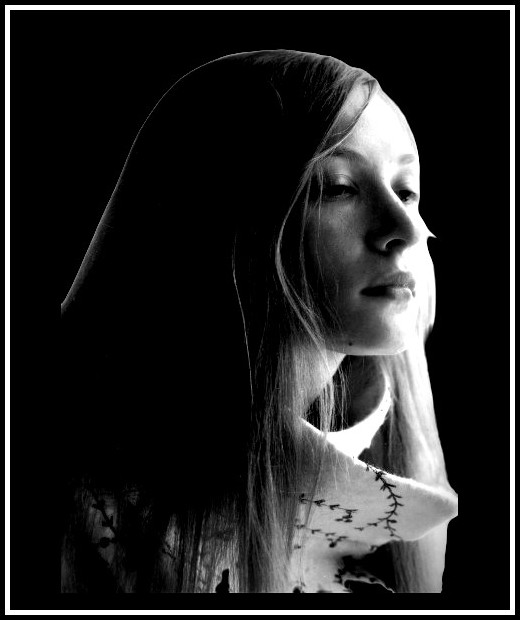

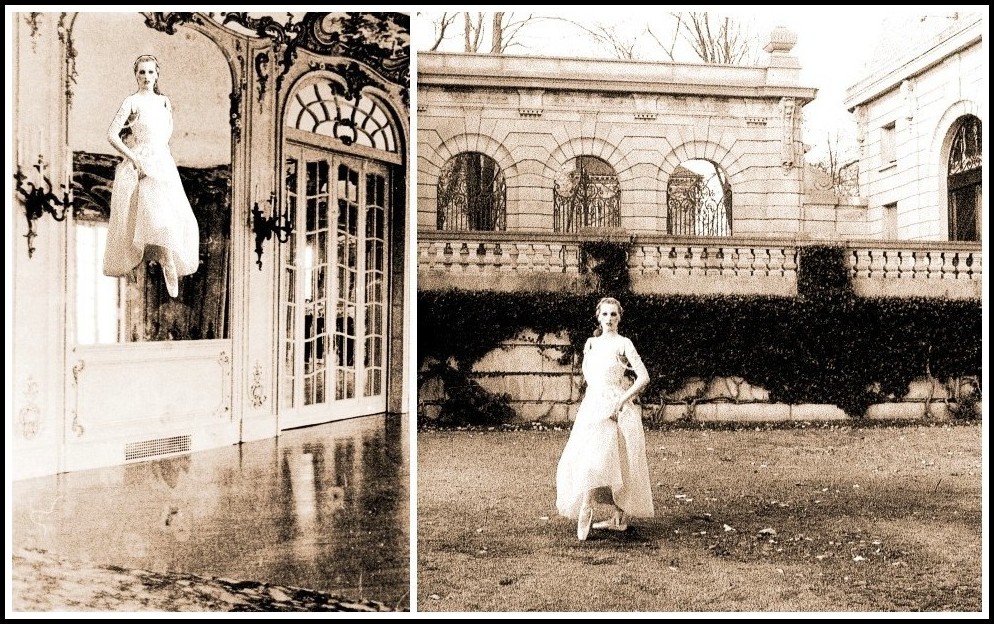

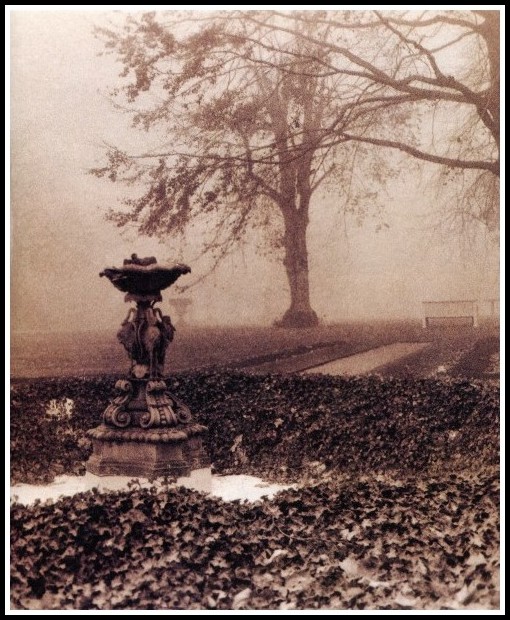

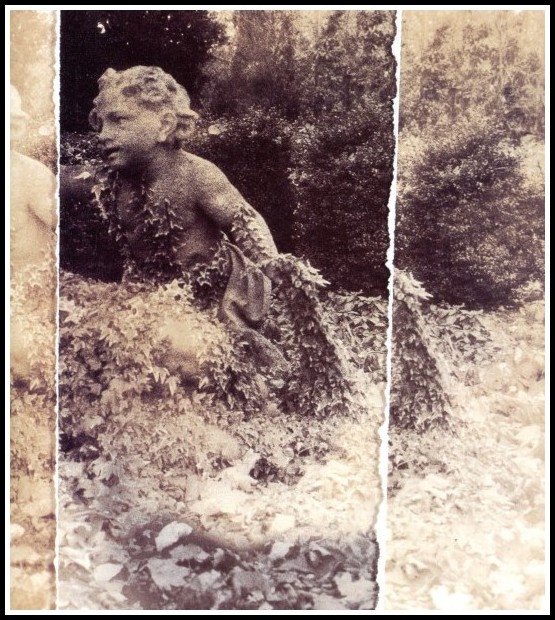

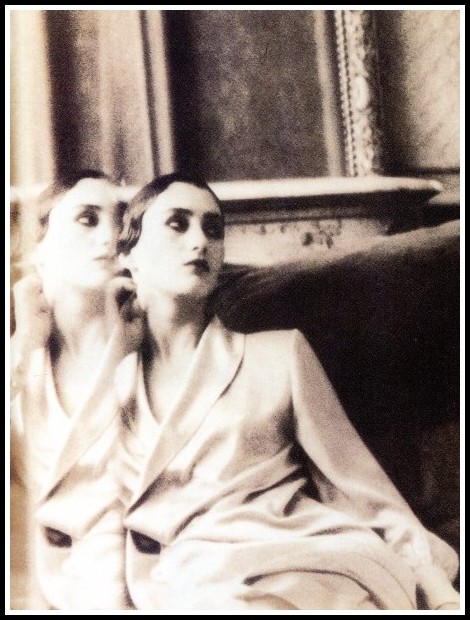

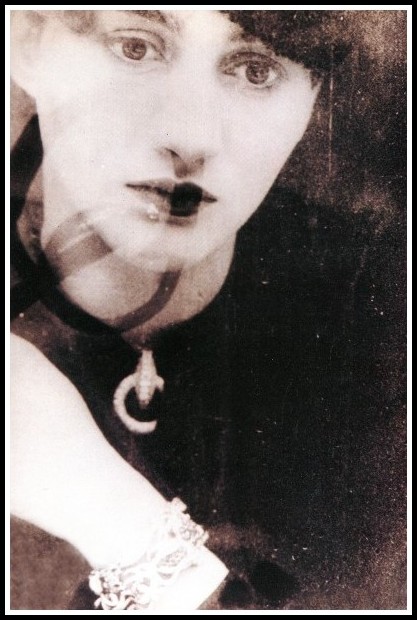

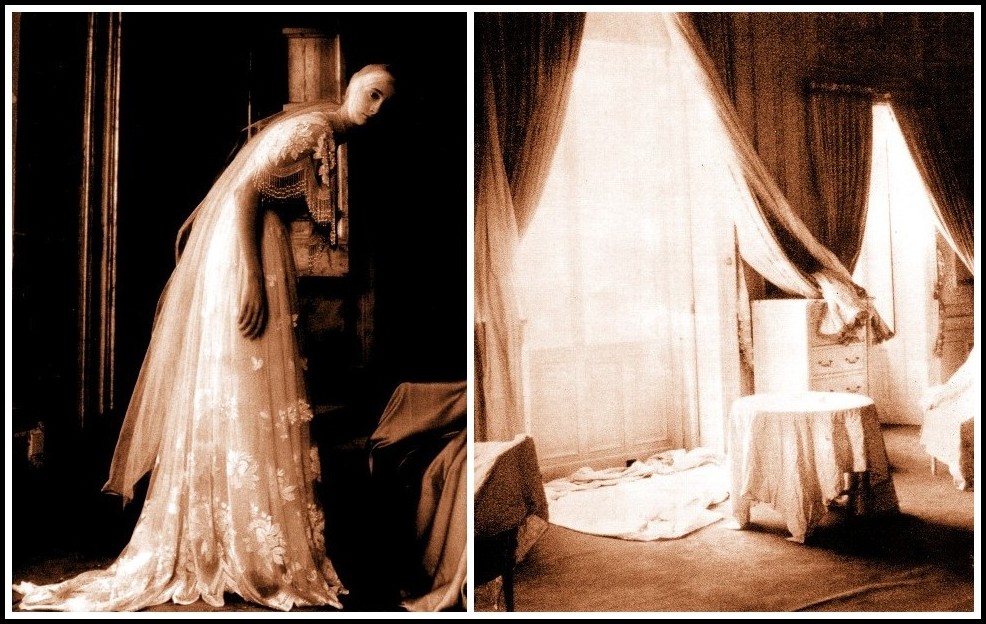

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992 | Composite: RJ

CHAPITRE 3: RAPT

Gwenaëlle Aubry, Perséphone 2014, pp. 45-49

Il riait en me disant de l’enchaîner. (Euripide, Les Bacchantes)

On dit que dans ton cas la terre s’est ouverte et qu’il en a surgi. On ne le nomme pas, celui qui va vous prendre, toi et ton nom, on l’invoque seulement, on le dit de biais (le maître de tant d’êtres, le seigneur de tant d’hôtes). C’est comme si, pour les autres aussi (ceux qui parlaient ta langue, racontaient ton histoire), il était tout entier contenu dans ce mouvement, presque invisible à force de rapidité : surgir/saisir.

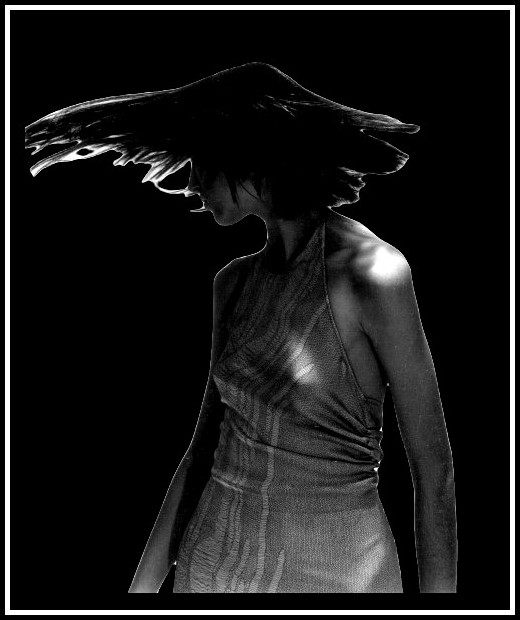

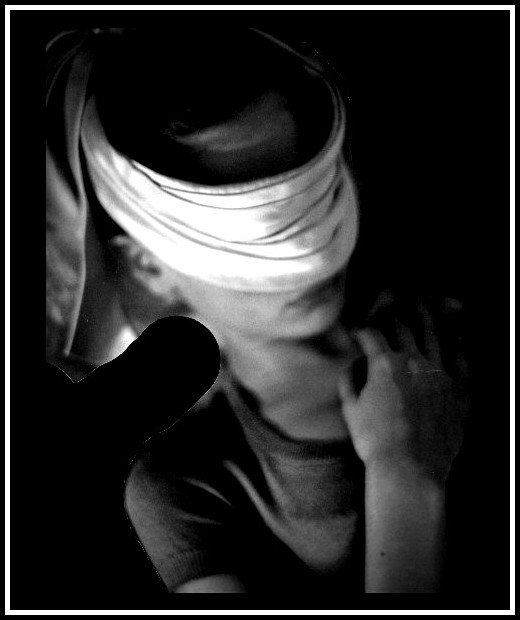

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992

On brode un peu, on décore, on légende, on parle de chevaux de char de larmes et d’or, on essaye de retenir la foudre, de cercler le vide.

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992

On dit aussi (et ça, je suis tentée de le croire) que tu as crié, que tu n’as pas cessé de crier, tu avais déjà disparu que la terre retentissait encore de tes cris, mais personne, ni dieu, ni bête, ni homme (personne, sauf Hécate, seule, dans sa tendresse), ne t’a entendue ou n’a voulu t’entendre, hommes et bêtes depuis longtemps perdus de vue, dieux repliés dans leurs temples à guetter avides les prières, mais toi, tu ne pries pas, tu ne sais plus du tout ce que c’est que prier, toi, tu cries.

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992

Je regarde la fresque qui essaye de capturer ça, l’acte éclair, le rapt, l’instant. C’est une fresque organique, cinabre, laque rose et malachite, où seuls sont vraiment visibles les détails, le décor : la roue et l’essieu du char, la femme (servante, témoin) accroupie dans l’angle droit et qui lève la main en un geste inutile d’arrêt ou de supplication, vos visages, vos visages aussi sont distincts, tous deux couronnés de boucles rousses, de flammèches emmêlées, le sien, à moitié mangé par une barbe rousse encore, de trois quarts, une belle tête de dieu mâle, grave, sensuel, dédaigneux, avec pourtant dans le regard, clair et frontal, une nuance d’effarement, le tien, si fin, à l’ovale parfait, déjeté, implorant, bouleversé — mais vos corps, vos corps où tout se joue, sont comme fondus dans la pierre, presque déjà disparus, sans ce voile rose qui vous enveloppe tous deux, tombe de ses épaules à tes hanches où il gonfle et se plisse, c’est à peine si on les distinguerait, il faut regarder de très près pour voir le trait délicat qui marque les contours du tien, tes bras levés, tes poignets de fille menottés de bracelets d’or, ton ventre creusé, et sur ton sein sa main.

Fresque de la tombe de Vergina (Grèce), Enlèvement de Perséphone par Hadès, 340 av. J.-C.

De ce qui se passe en cet instant (et dont nul, en vérité, ne peut être témoin, face à quoi nul regard, nulle prière ne tient) les corps sont déjà absentés. Ils vont plus vite que vous, qui vous accrochez encore à vos visages et à vos noms, ils sont déjà ailleurs, effacés par leur propre vitesse, déjà là où les contours se fondent, et seul s’imprime sur le mur leur tracé d’irradiés.

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992

On dit que dans ton cas c’est arrivé ainsi. Et relisant ta vieille histoire, regardant la fresque de Vergina (une mauvaise reproduction, achetée dans la boutique d’un musée), je me souviens de certains détails (la rousseur flamboyante, les corps très blancs, les poignets entravés). Mais ce que je voudrais voir en face (ce que depuis toutes ces années je n’ai cessé de chercher), c’est la terre qui s’ouvre, la faille, l’instant dans lequel tu t’es engouffrée (j’y suis encore avec toi, nous y sommes ensemble, tu le sais) : c’est ce qui d’un coup a tout cassé, le temps, le cycle, tes bonds de cavale, tes pas de danseuse, ton habileté de tisseuse, la trame des travaux et des jours que jadis tu filais, et toi aussi bien sûr, l’espèce de poupée abstraite que tu étais, l’irritante petite idole, jeune fille, jeune déesse, c’est pareil : des images, rien que des images, pures, vagues, vides. C’est l’instant-précipice où tout a glissé, champs labourés, prairie étincelante, rires de filles, rites de surface, tout cet enfer diurne que tu as quitté dans un cri où (j’aime à le croire, je m’en souviens) l’effroi se mêlait de triomphe.

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992

Je voudrais voir en face la fêlure que déjà tu portais : éraflure sur le marbre, coup d’ongle sur ton corps de cire, blessure de ton corps de fille. Quelques années auparavant, tu sortais à peine de l’enfance, tu as ouvert un livre : Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein. Je crois que tu n’as pas compris ce titre, que tu n’as pas cherché à aller au-delà de sa musique, ce bruit d’ailes froissées, de son dessin, ces S, ces L, ce V, surtout, où tu ne voyais pas une initiale mais une empreinte (patte d’oiseau sur le sable), un signe (triangle ouvert). Pour le reste, je n’ai aucune idée de ce qu’a été ta lecture : une sorte d’état parallèle, j’imagine, qui t’a emmenée dans un lieu du réel dont, sans doute, tu pressentais qu’il était le tien. Je me souviens seulement que, le livre refermé, tu as eu besoin d’en recopier une phrase sur un bout de papier et que, ce bout de papier, tu l’as punaisé dans ta chambre à côté de tes demi-dieux d’alors (Marilyn, Garbo, Ziggy Stardust). Je me souviens aussi de la phrase (simple, neutre, élémentaire) : « L’idée de ce qu’elle fait ne la traverse pas. »

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992

Je pourrais rire, plus encore t’érafler, couper tailler dans la jeune fille, la vaine petite idole, la petite vierge folle : mais le fait est que ce livre, cette phrase, ont agi sur toi, vol d’oiseaux très lisible, comme une sorte d’augure, ton histoire s’y inscrivait, le bal, la marche de prairie des deux femmes, fille et mère, la forme blonde allongée dans le champ de seigle, et puis surtout l’instant, l’instant de foudre qui troue le temps.

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992

Ravie, raptée, tu voulais l’être déjà, ton désir se lisait là, à ceci près que de cette scène tu n’es pas le témoin, la femme en tiers accroupie dans l’angle droit de la fresque, la silhouette dissimulée dans les seigles, ce que tu veux c’est ne plus être témoin, et surtout pas de toi, c’est, précisément, n’avoir aucune idée de ce que tu fais, c’est ne plus pouvoir dire, ni même penser : jusque-là, c’est moi.

Deborah Turbeville, Newport Remembered, 1992

GWENAËLLE AUBRY

Perséphone 2014

GWENAËLLE AUBRY

Perséphone 2014

PART II

PERSEPHONE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 13

Once, when your eyes were dazzled by a blanket of blue mist, he showed you it was sea holly, a whole colony whose thistle-like leaves had changed from green to blue. Another time, when you came across a field of chasteberry, he told you the legend that it cools the heat of lust, that women would use it as bedding during the festival for Demeter and Persephone. And thus began his giving you an education in Greek mythology, and thus began your passion for Persephone. You would go on to read Hesiod’s Theogony, you would go on to read the ‘Hymn to Demeter’ in The Homeric Hymns. What was it about that homeless girl, fated to ferry between two worlds, that appealed to you so? Was it her being an abandoned child, ravished and left on the cusp of girlhood, forever ambivalent toward her mother? Was it her descent into a secret world, her encounters on the boundary crossing? Or was it simply her blending of sexuality and play? Whatever it was, she provided you with a mirror to reflect on yourself. Is that why you consider Persephone your sister?

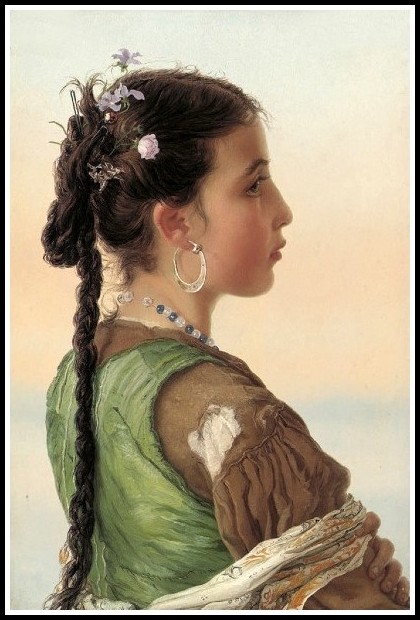

Adriano Bonifazi, A Capri Girl, 1879

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Six Chapter 2

Do not swallow the pomegranate seed: On your pyjamas an owl stares out from her domain of darkness.

̶ The orphanage—when did he get out of it?

̶ When he turned sixteen. 1958. He was already an exceptional athlete; they saw his promise. Rome was 1960, Tokyo 1964.

̶ And when exactly did you find out about…

̶ All those horrible things?

̶ Yes.

̶ Just before we got married. One night, after we’d made love—

̶ Mama!

̶ How do you think you were conceived?

̶ All right, all right.

̶ One night, after we’d made love, he just started crying. Crying and crying and crying. And then it all came out…

Too late, too late, the owl has seen me swallow: Never shall I escape for long now into the light of day… Warm, warm, your tears flow, across the icy surface of history, trying to find a river to take you to the sea.

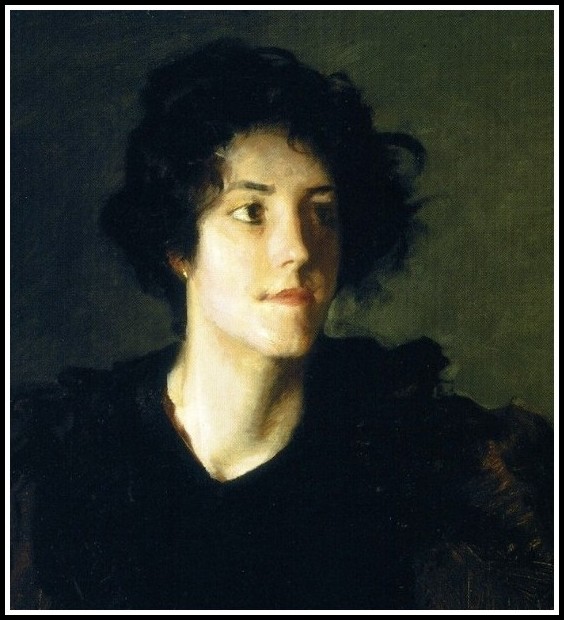

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, The Greek Girl, 1870

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

PART III

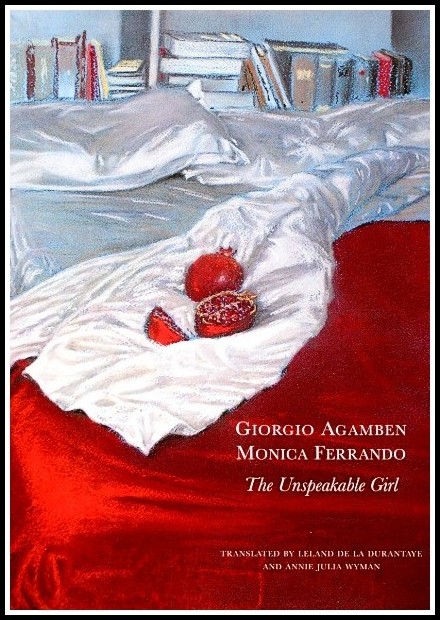

THE UNSPEAKABLE GIRL: THE MYTH AND MYSTERY OF KORE

Giorgio Agamben

Abbreviated from Giorgio Agamben & Monica Ferrando, The Unspeakable Girl: The Myth and Mystery of Kore, tr. Leland de la Durantaye & Annie Julia Wyman (Seagull Books, 2014) pp. 1-21

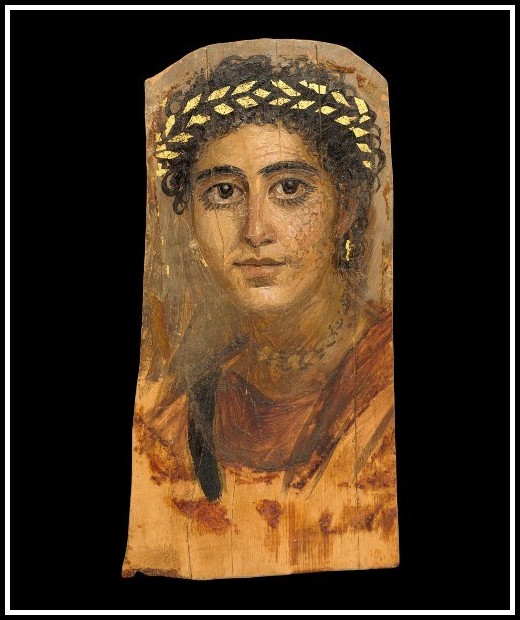

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Egyptian Girl, 1877

The fifth-century Alexandrian lexicographer Hesychius refers to a lost play by Euripides in which figures an ‘unspeakable girl’. Hesychius explains that she is none other than Persephone. One of Persephone’s more common epithets is ‘little girl’—kore. Kore, the ‘divine girl’, seems at once to call into question and to annul the distinction between the two essential figures of femininity—woman (or mother) and girl (or virgin). Of the Eleusinian Demeter, the scandalized Church Father Clement of Alexandria asked, ‘Am I to call her mother or wife?’ Between daughter and mother, virgin and woman, the ‘unspeakable girl’ presents a third figure which puts into question all we think we know about femininity, and all we think we know about man and woman.

Franz Xavier Winterhalter, Study of an Italian Girl, 1833

The Greek term kore does not refer to a precise chronological age. Derived from a root meaning ‘vital force’, it refers to the principle that makes both plants and animals grow. A kore can thus be old. Aeschylus calls the Furies, the terrifying avengers of blood crime, ‘korai’, as well as ‘ancient children with white hair’. It is telling in this regard that the rage and the implacable pursuit of vengeance which the tragic hero—and, in The Eumenides, Athena and Apollo—seek by every means to domesticate are embodied by children. One of these ‘aged girls’—benevolent this time—is Iambe, who appears in the myth of Persephone, of Kore—the girl par excellence. Kore is life in so much as it does not allow itself to be ‘spoken’, in so much as it cannot be defined by age, family, sexual identity or social role.

John Phillip, A Gypsy Girl, 1860

Erwin Rohde claimed that the Eleusinian mystery cult consisted of dramatic action or, more precisely, of a sort of ‘pantomime accompanied by sacred chants and formulae’ representing ‘the sacred story of the rape of Kore, the wanderings of Demeter and the reunion of the two goddesses’. Clement of Alexandria defined the Eleusinian mystery cult as drama mystikon or ‘initiatory drama’. The verb myein, ‘to initiate’, means etymologically, ‘to close’—notably the eyes but, more importantly, the mouth. At the beginning of the sacred rites, the herald would ‘command silence’. In his version of ‘Eleusinia’, Giorgio Colli asked what meaning the requirement of secrecy for initiates into the Eleusinian mysteries could have had so that the entire Athenian population was eligible for initiation. The source materials make clear that everyone, including slaves, was eligible for initiation (as long as they had not defiled themselves through a blood crime). Colli, for his part, stresses that the officiating families of the Eumolpidae and the Kerykes undertook a careful selection of initiates, at least for the ‘grand mysteries’, culminating in what was called the ‘vision’.

Jan Portielje (1829-1908), Spanish Girl

It is nevertheless possible that the point of the silence was not to keep the uninitiated ignorant but intended for the benefit of the initiates themselves. In other words, it is possible that those who had been given an experience of the unknowable—or, at least, the discursively unknowable—were encouraged to refrain from attempting to put into words what they had seen and felt. Clement of Alexandria was either himself initiated into the mystery cult at Eleusis or was told of the process by more or less reliable sources. He relates that, at Eleusis, the hierophant presented the initiate with a cut ear of wheat and recited the formula hye, kye (‘rain’, ‘render fertile’). ‘And this was the grand and inexpressible Eleusinian mystery,’ he contemptuously writes. In so doing, Clement displays the degree to which he had lost all sense of the role and meaning of the unspeakable in pagan religion. Through the mystery cults one was not held to learn something—such as a secret doctrine—about which one had to then remain silent. Instead, the initiate was meant to ecstatically experience his or her own silencing—’when confronted with the gods great wonder silences the voice’. The initiate was thus to experience the power and potentiality offered to mankind of the ‘unspeakable girl’—the power and potentiality of a joyfully and intransigently infantile existence. As Rohde remarked: ‘It was impossible to reveal “the mystery” because there was nothing to reveal’.

Arthur Melville (1858-1904), The Babylonian Girl

In light of the preceding it should come as no surprise that, in Greek, the expression for ‘divulging the mystery’ is exorchesthai to mysteriai—literally, ‘dance it away’ or ‘dance it out’, which also means ‘fake it’ or ‘imitate it poorly’. What is more, in the Hymn to Demeter, it is said of the orgia kala (‘sacred rituals’) that it is not possible to ‘seek to know’ them. At two points in esoteric dialogues which have been lost, Aristotle compared philosophical wisdom to mystical vision. The first of these was in Eudemus, where we read that ‘those who have directly touched pure truth claim to possess philosophy’s ultimate term, as in an initiation’ (Eudemus frag. 10). It was, however, in De philosophia that Aristotle makes the comparison most comprehensively. Therein, Aristotle affirms that ‘the initiates do not have to learn something but that, after having become capable, they experience and are disposed to it’ (De philosophia frag. 15). In that same work, Aristotle distinguishes between ‘that which is proper to teaching and that which is proper to initiation. The first comes through listening, the second comes only when the intellect itself is illuminated.’

William Merritt Chase, Study of a Spanish Girl, 1885 (detail)

It is important to eschew the facile interpretation of these passages which would have Aristotle veiling philosophical wisdom in clouds of mysticism and, instead, to carefully analyse them. This is necessary not only to understand Aristotle’s sense of supreme philosophical wisdom but also for the light they cast on the essence of mystical initiation. If we recall the decisive role that the concepts of pathos and hexis play in Aristotle’s theory of knowledge as it is put forth in De anima, this fragment proves singularly illuminating. Aristotle distinguishes between two meanings for the term paschein. The first refers to someone in the process of learning something, for whom ‘to undergo’ implies the sense of ‘destruction through the working of an opposing principle or concept’. The second refers to someone who has already become familiar with a certain subject matter and for whom ‘to undergo’ implies ‘the conservation of potentiality in an act that is similar to it’. In the second case, ‘he who has a certain knowledge becomes a knower in act, and this is not an alteration because there is increase (“supplementary gift” both towards oneself and towards the act’.

Émile Munier, Italian Girl, 1874 (detail)

The two modes of philosophical wisdom described here correspond exactly to the two types of knowledge presented in fragment 15: the didactic and the initiatory. Aristotle affirms this without reservation in a passage which may be considered an allusion to De philosophia: ‘The intelligent and thinking being should call that which leads from potentiality to actuality not learning but by another name’. In the esoteric dialogue, this ‘other name’ is drawn precisely from the language of the mystery cults—’the initiatory’. According, thus, to the testimony of Aristotle, that which the initiate experienced at Eleusis was not irrational ecstasy but a vision analogous to theoria, to supreme philosophical knowledge. What in both cases is essential was that the experience in question no longer concerned material which was learnt as much as it did a manner of experiencing, a way of undergoing, a giving of self and a completion of thought. And it was this completion of thought that Aristotle, at two decisive instances in Metaphysics, expresses through the term thigein (touch) which, in the fragment cited from Eudemus, is compared to the experience of initiates.

Jan Portielje (1829-1908), Albanian Girl (detail)

In Metaphysics, Aristotle says that, in knowing uniform things, the truth lies in ‘touching and naming’, and immediately specifies that ‘naming’ is not the same as ‘proposition’. The knowledge conveyed at Eleusis could thus be expressed in names but not in propositions; the ‘unspeakable girl’ could be named but not said. In the mystery cult, there is thus no place for assertion but only for the name. And in the name is something like a ‘touching’ and a ‘seeing’. By likening philosophical knowledge to the mystery cults, Aristotle was returning to and taking up a Platonic motif. In Symposium, Diotima speaks of love’s ‘mysteries’ and ‘initiatory visions’; she affirms that in love’s mysteries there will not be ‘either discourse or science’ and that beauty ‘renders itself visible for itself and with itself in a single eternal vision’. In Phaedrus, the philosopher is compared to ‘a man ceaselessly initiated into perfect mysteries’ (this means that, in ancient Greece, philosophy seemed to locate itself with respect to mystical experience, just as, later, it sought its legitimation with respect to religion as vera religio). When she was abducted by Hades, Kore was ‘playing with the girls of Ocean’. That a girl at play became the ideal figure for the supreme initiation and the completion of philosophy, the figure for something that is at once thought and initiation and thus unspeakable—this is the ‘mystery’.

Egypt, Portrait of a Young Woman, 110 AD

Giorgio Agamben & Monica Ferrando

The Unspeakable Girl: The Myth and Mystery of Kore

GIORGIO AGAMBEN & MONICA FERRANDO

The Unspeakable Girl

PART IV

D.H. LAWRENCE: TWO PERSEPHONE POEMS

BAVARIAN GENTIANS

D.H. Lawrence

Not every man has gentians in his house

in soft September, at slow, sad Michaelmas.

Bavarian gentians, big and dark, only dark

darkening the day-time, torch-like with the smoking blueness of Pluto’s gloom,

ribbed and torch-like, with their blaze of darkness spread blue

down flattening into points, flattened under the sweep of white day

torch-flower of the blue-smoking darkness, Pluto’s dark-blue daze,

black lamps from the halls of Dis, burning dark-blue,

giving off darkness, blue darkness, as Demeter’s pale lamps give off light,

lead me then, lead the way.

Reach me a gentian, give me a torch!

let me guide myself with the blue, forked torch of this flower

down the darker and darker stairs, where blue is darkened on blueness

even where Persephone goes, just now, from the frosted September

to the sightless realm where darkness is awake upon the dark

and Persephone herself is but a voice

or a darkness invisible enfolded in the deeper dark

of the arms Plutonic, and pierced with the passion of dense gloom,

among the splendour of torches of darkness, shedding darkness on the lost bride

and her groom.

‘Reach me a gentian, give me a torch!’ | Composite: RJ

PURPLE ANEMONES

D.H. Lawrence

Who gave us flowers?

Heaven? The white God?

Nonsense!

Up out of hell,

From Hades;

Infernal Dis!

Jesus the god of flowers—?

Not he.

Or sun-bright Apollo, him so musical?

Him neither.

Who then?

Say who.

Say it –and it is Pluto,

Dis,

The dark one.

Proserpine’s master.

Who contradicts—?

When she broke forth from below,

Flowers came, hell-hounds on her heels.

Dis, the dark, the jealous god, the husband,

Flower-sumptuous-blooded.

Go then, he said.

And in Sicily, on the meadows of Enna,

She thought she had left him;

But opened around her purple anemones,

Caverns,

Little hells of colour, caves of darkness,

Hell, risen in pursuit of her; royal, sumptuous

Pit-falls.

‘Flowers came, hell-hounds on her heels’ | Composite: RJ

All at her feet

Hell opening;

At her white ankles

Hell rearing its husband-splendid, serpent heads,

Hell-purple, to get at her—

Why did he let her go?

So he could track her down again, white victim.

Ah mastery!

Hell’s husband-blossoms

Out on earth again.

Look out, Persephone!

You, Madame Ceres, mind yourself, the enemy is upon you.

About your feet spontaneous aconite,

Hell-glamorous, and purple husband-tyranny

Enveloping your late-enfranchised plains.

You thought your daughter had escaped?

No more stockings to darn for the flower-roots, down in hell?

But ah, my dear!

Aha, the stripe-cheeked whelps, whippet-slim crocuses,

At’em boys, at’em!

Ho, golden spaniel, sweet alert narcissus,

Smell’em, smell’em out!

Those two enfranchised women.

‘All at her feet, hell opening’ | Composite: RJ

Somebody is coming!

Oho there!

Dark blue anemones!

Hell is up!

Hell on earth, and Dis within the depths!

Run, Persephone, he is after you already.

Why did he let her go?

To track her down;

All the sport of summer and spring and flowers snapping

at her ankles and catching her by the hair!

Poor Persephone and her rights for women.

Husband snared bell-queen,

It is spring.

It is spring,

And pomp of husband-strategy on earth.

Ceres, kiss your girl, you think you’ve got her back.

The bit of busband-tilth she is,

Persephone!

Poor mothers-in-law!

They are always sold.

It is spring.

‘Hell on earth, and Dis within the depths!’ | Composite: RJ