Rainer Maria Rilke

PART I: RAINER MARIA RILKE AND THE ARTIST AS TRANSFORMER | PART II: RAINER MARIA RILKE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

PART I

RAINER MARIA RILKE AND THE ARTIST AS TRANSFORMER

Judith Eleanor Bernstock

Posted by kind permission of Judith Eleanor Bernstock, Associate Professor Emerita, History of Art and Visual Studies, Cornell University

From Judith Bernstock, Under the Spell of Orpheus: The Persistence of Myth in Twentieth-Century Art (Southern Illinois University Press, 1991) pp. 25-29

Carl Milles, Study for Orpheus, 1923 | Barbara Hepworth, Orpheus, 1956

Rainer Maria Rilke’s image of the legendary hero in his Sonnets to Orpheus, written in February 1922, has far surpassed any other figure in modern literature in its international fame and impact on representations of Orpheus by twentieth-century artists and writers. Rilke is one of the few twentieth-century poets to have reached a worldwide audience and in France is read even more than French poets of this century. The Sonnets were inspired by a French prose version of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a postcard reproduction of a drawing by Cima da Conegliano of Orpheus playing for the animals (ca. 1505-10), and the recent death of Vera Knoop, the nineteen-year-old daughter of Dutch friends. The Sonnets to Orpheus arose from ‘a hurricane in the spirit,’ as the poet paced back and forth across his room ‘howling unbelievably vast commands and receiving signals from cosmic space and booming out to them my immense salvos of welcome.’ Rilke’s extraordinary burst of inspiration resulted in a work resounding with the freedom and joy of their creation, the clearest and fullest possible apotheosis of the powers of feeling, which can effect metamorphoses.

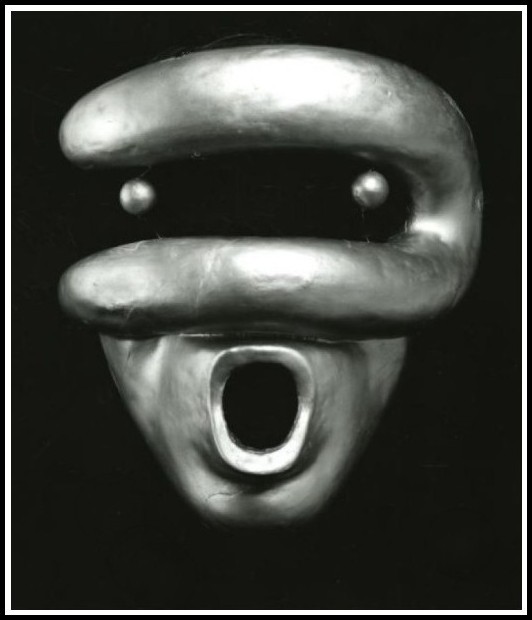

Isamu Noguchi, Mask of Orpheus, 1948

Under the influence of his friend Lou Andreas-Salomé who had studied with Freud and introduced Rilke to him in 1913, Rilke had considered entering psychoanalysis for his depressions; with the close knowledge that he had gained of Freud’s theories he was inspired to write his Third Elegy. Similarly, the Sonnets, expressing an overwhelming desire to save himself by change, may have been Rilke’s tacit acknowledgment of his need for some form of therapy and reflect at once his interest in Freudian analysis and his repulsion and rejection of the Freudian method of effecting self-change. Instead, like his compatriot Franz Marc, who had also suffered from a sense of failure over attempts to fulfill the demands of an ego ideal, Rilke tried other means, including idealization of Orpheus and identification with him, to save and strengthen his ego.

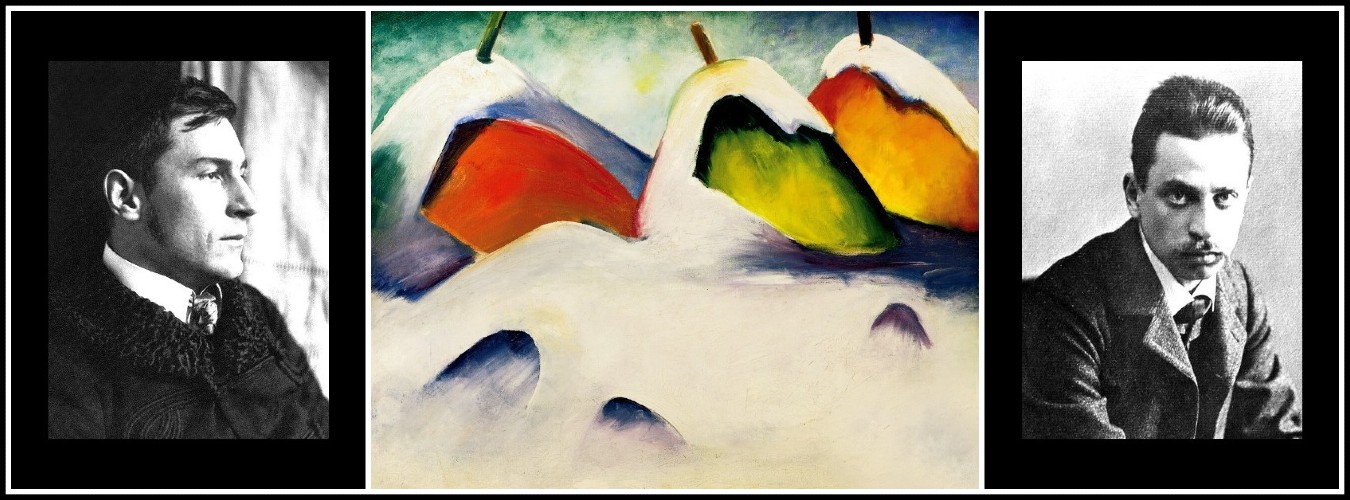

Franz Marc, 1880-1916 | Franz Marc, Hocken im Schnee, 1911 | Rainer Maria Rilke, 1875-1926

To Rilke, Orpheus symbolized the poet’s ability of self-transcendence (and his song, pure transcendence). Through creative activity the poet transforms the visible into the invisible—from experience into inwardness, a true state of awareness—and thus escapes an unworthy, rejected self and achieves perfection. Rilke regarded his rigid, reactionary father as incapable of loving and as possessing ‘a kind of indescribable fear of the heart toward [him], a feeling against which [he] was very nearly defenseless.’ Rilke’s mother, who always appeared to her son to be superficial and excessive in her religious piety, had hoped for a girl and raised him as such. With a mother who would have liked to change his sex and a father who rejected his son’s character, it was inevitable that Rilke would suffer from identity crises, depressions, psychosexual self-doubts, and longings for transformation to a more acceptable, even transcendent self.

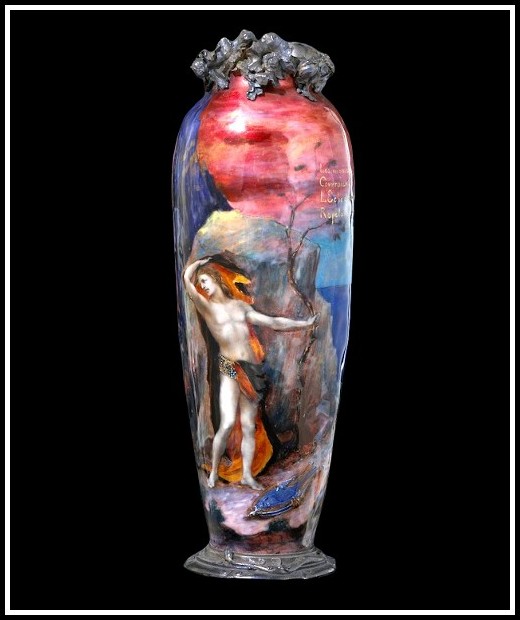

Paul Grandhomme, Orpheus, 1892

Rilke required of himself that he reach the realm of the angel in the Duino Elegies: ‘I must get beyond man and pass over (as a novice) to the angels.’ The angel was the witness and the warranty of the highest perfection of feeling, the invisible configuration of sheer inwardness, and the realization of transcendence. Rilke explained that the Elegies show our need and ability to accomplish the transformation of the visible and tangible into the invisible vibrations and agitations of our own nature, for we are ‘transformers of the earth, our whole existence.’ According to Rilke, the contemporaneous Elegies and Sonnets ‘support each other continually,’ and the theme of transformation was furthered in the Sonnets through the figure of Orpheus, who symbolized the poet’s ability to change the world into rhythmic vibrations. He believed that our greatest and most permanent tasks are those of transformation and transmutation, which attain their highest expression in the song of Orpheus, who demonstrates eternal metamorphoses.

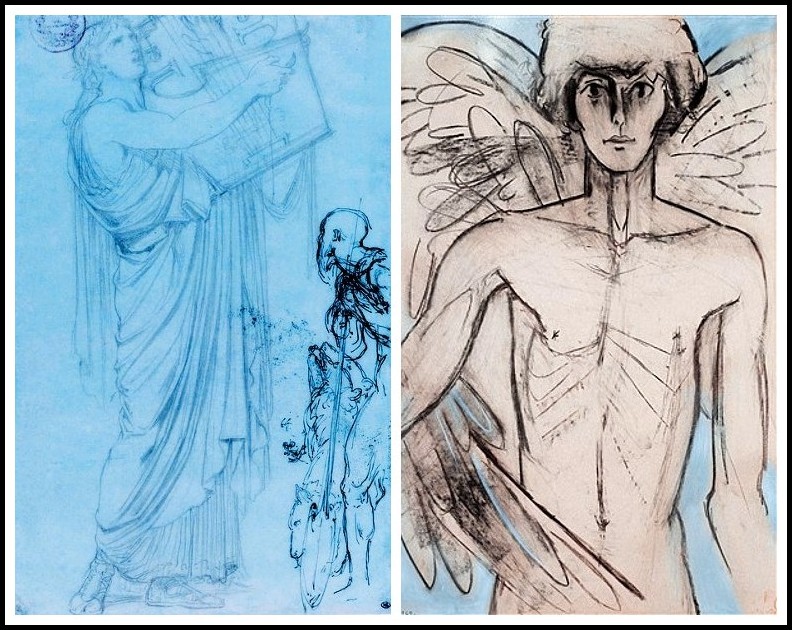

Henri Regnault, Orpheus, 1865 | Françoise Gilot, Angel (Jacob), 1966 (detail)

Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus (I:1) open with an image of the ideal poet whose song is a tree that effects transcendence and is a symbol of creation and recreation.

DIE SONETTE AN ORPHEUS – I: 1

Rainer Maria Rilke

Da stieg ein Baum. O reine Übersteigüng!

O Orpheus singt! O hoher Baum im Ohr!

Und alles schwieg. Doch selbst in der Verschweigung

ging neuer Anfang, Wink und Wandlung vor.

Tiere aus Stille drangen aus dem klaren

gelösten Wald von Lager und Genist;

und da ergab sich, daß sie nicht aus List

und nicht aus Angst in sich so leise waren,

sondern aus Hören. Brüllen, Schrei, Geröhr

schien klein in ihren Herzen. Und wo eben

kaum eine Hütte war, dies zu empfangen,

ein Unterschlupf aus dunkelstem Verlangen

mit einem Zugang, dessen Pfosten beben,—

da schufst du ihnen Tempel im Gehör.

SONNETS TO ORPHEUS – I: 1

Rilke | Christiane Marks

There, see—a tree ascended. Pure transcendence!

Oh, Orpheus sings! Oh, tall tree in the ear!

And all was silent. Yet that silence yielded

beginnings, beckonings, and transformations.

Creatures of stillness issued from the clear,

wide-open forest filled with lairs and nests.

And it turned out that neither cunning

nor fear had caused this inner quiet,

but listening had. Bellow and shriek and roar

seemed small inside their hearts, and where just now

there’d scarcely been a hut to take this in—

a hidden refuge made of darkest longing,

the very doorposts of its entrance quaking—

you raised up temples for them in their ears.

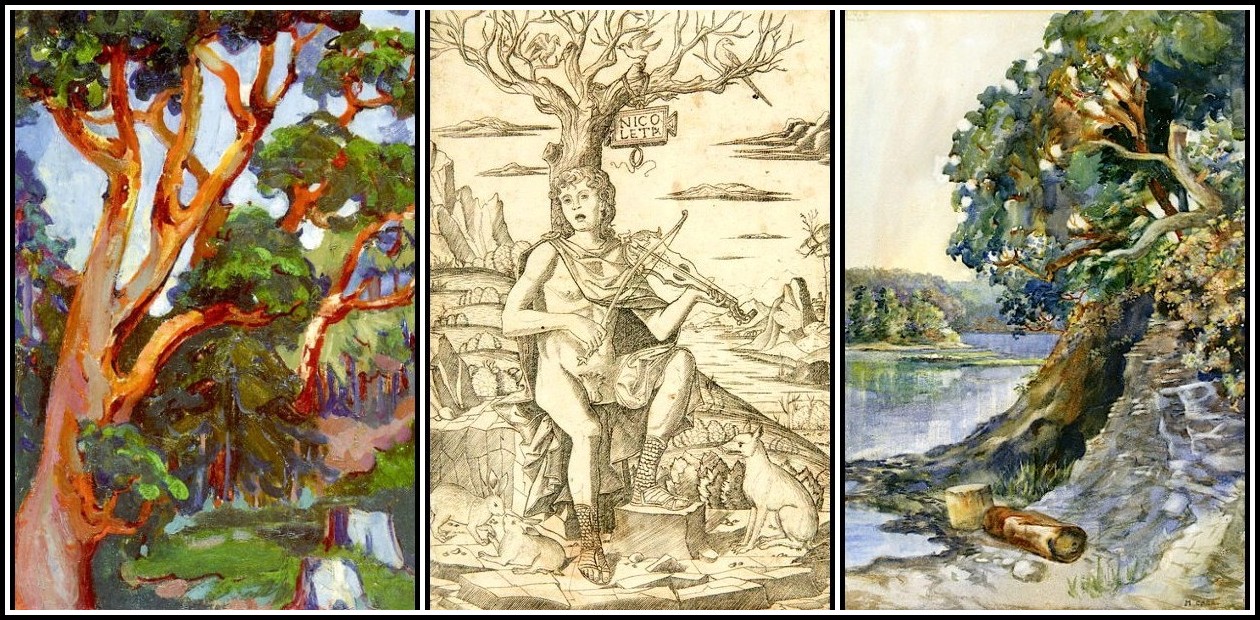

Emily Carr, Arbutus Tree, 1922 | Nicoletto da Modena, Orpheus, 1505 | Emily Carr, Arbutus Tree, 1909

Since antiquity the metamorphosing powers of art and the animation of brute nature have been implied in Orpheus’s charming of trees to follow him. Ovid presents an arrangement of trees that symbolize the feelings of Orpheus himself (Metamorphoses 10.89-107). As G. Karl Galinsky notes: ‘The literalness of the theme of movement of trees is superseded by its transference to its imaginative and tonal qualities,’ the whole reflecting the situation of the singing and grieving Orpheus. The tree, traditional symbol of vegetable rebirth and self-renewal, was associated with Dionysos, who, according to Plutarch (Moralia 5.3i), was worshiped ‘almost everywhere in Greece’ as ‘the tree god.’ The self-identification of the poet with the tree was frequent in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Baudelaire expressed his complete identification with nature by comparing himself to a tree: ‘First you lend the tree your passions, your desires or your melancholy; its sighs and its oscillations become yours and soon you are the tree.’. For Rilke, a tree is a symbol of creation and growth as well as a descent into roots.

Louis Français, Orpheus, 1863 | Aristide Croisy, Orpheus, 1880 | Hendrick Voogd, Italian Landscape with Umbrella Pines, 1807

Considering the strong visual element in Rilke’s poetry and his characteristic sensitivity to art and inspiration from it (as in his earlier Orpheus poem) and the fact that he went to the trouble of procuring a copy of the drawing by Cima da Conegliano that he had seen in a shop window and kept it constantly in view of his worktable, it seems important to study the Renaissance drawing. For some reason, scholars have neglected to discuss it fully in considering the origins of the Sonnets.

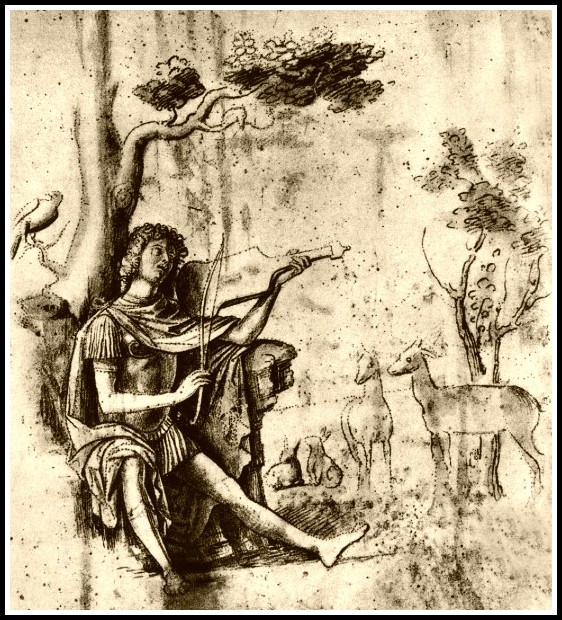

Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano (1459-1517), Orpheus (detail)

Although Rilke clearly did not intend a literal description of the drawing, the first sonnet about Orpheus is strangely reminiscent of Cima’s image of Orpheus. His plaintive singer sits before a tree that seems to sprout ambiguously above and from him. The outline of Orpheus’s chest resembles that of the trunk of the tree, his legs seem like its roots, and the branch bursting into foliage above echoes the contour of his lira da braccio. On 31 January 1922, a few days before Rilke began the Sonnets, he had written a triptych titled ‘Short poetic cycle with the vignette: lyre breaking into foliage.’ One may speculate that the first of his Sonnets emerged partly as a result of the drawing’s reaffirmation of his feelings about Orphic creativity. A delicately drawn tree has ‘ascended there’ and is identified with the creator whose song transforms the disorder of nature into art. ‘A new beginning, a beckoning’: all becomes silent before the poet’s song. Quietly (‘so quiet in themselves’), barely perceptible creatures (gazelles, rabbits, birds) have crowded from the bright, unbound forest to listen to the music. The square design becomes a sacred realm, a temple for ‘creatures of stillness’—those who hear and allow themselves, their visible forms—to become invisible in this universe of feeling.

Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano (1459-1517), Orpheus

By identifying with Orpheus, Rilke evidently gained greater confidence that he could transcend his unworthy self and satisfy a demanding ego ideal. Orpheus transforms even himself through the power of his song, the metaphor for the principle of existential change (II, 12).

DIE SONETTE AN ORPHEUS – II: 12

Rainer Maria Rilke

Wolle die Wandlung. O sei für die Flamme begeistert,

drin sich ein Ding dir entzieht, das mit Verwandlungen prunkt;

jener entwerfende Geist, welcher das Irdische meistert,

liebt in dem Schwung der Figur nichts wie den wendenden Punkt.

Was sich ins Bleiben verschließt, schon ists das Erstarrte;

wähnt es sich sicher im Schutz des unscheinbaren Grau’s?

Warte, ein Härtestes warnt aus der Ferne das Harte.

Wehe—: abwesender Hammer holt aus!

Wer sich als Quelle ergießt, den erkennt die Erkennung;

und sie führt ihn entzückt durch das heiter Geschaffne,

das mit Anfang oft schließt und mit Ende beginnt.

Jeder glückliche Raum ist Kind oder Enkel von Trennung,

den sie staunend durchgehn. Und die verwandelte Daphne

will, seit sie lorbeern fühlt, daß du dich wandelst in Wind.

SONNETS TO ORPHEUS – II: 12

Rilke | Christiane Marks

Trust transformation. Oh, thrill to the glow of the flame

veiling a thing that eludes you while flaunting its changings.

For the creative spirit that masters all earthly things

loves in the flow of the figure only its pivoting point.

Locked into permanence, all is frozen already.

Is there safety, then, in inconspicuous gray?

Wait! The hardest of all gives warning to hardness.

Oh, look out! A faraway hammer is raised.

Those who pour themselves out like a stream are acknowledged by knowledge,

and in delight she leads them through her serene creation,

which with beginnings often concludes, to begin with the end.

Each radiant space is the child or grandchild of separation,

and in amazement they cross it. Daphne transformed

utters a laurel tree’s wish that you might transform into wind.

Bernini, Apollo and Daphne, 1625

Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus have been called the most consistent myth of artistic experience in modern German literature and one of the strongest affirmations ever of the promise of existential salvation through poetry. Rilke’s Orpheus exemplifies the artist capable of remaking himself, for Rilke had decided that self-analysis and healing through his art were his only salvation. His thinking shows a distinct similarity to Nietzsche’s in Thus Spake Zarathustra, in which the idea of self-overcoming is expressed through the concept of the will to power, which is a striving to transcend and perfect oneself.

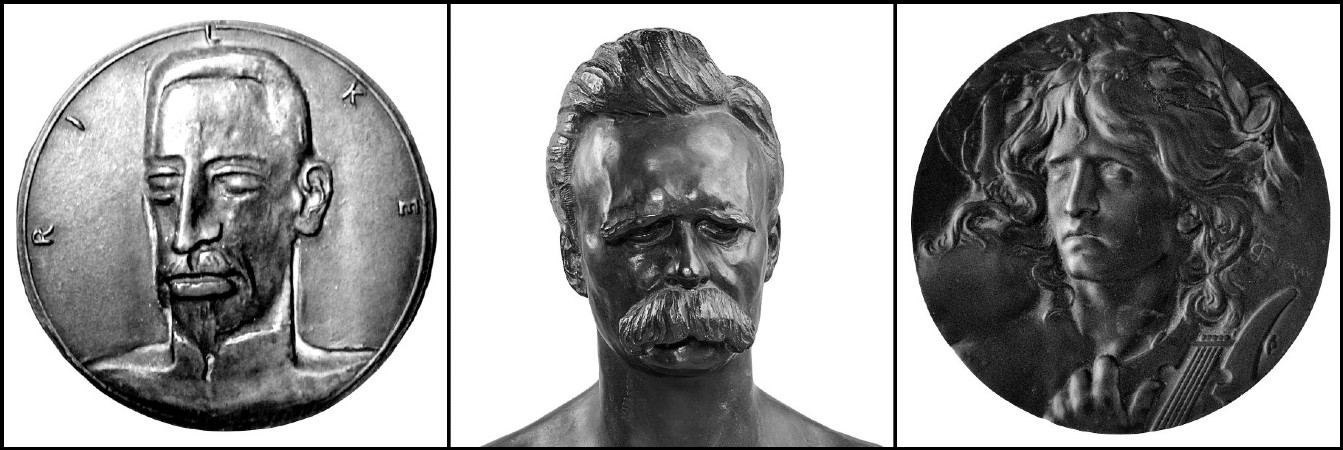

K. Weizenegger, Rilke, 1975 | Max Klinger, Nietzsche, 1904 | Lucien Coudray, Orpheus, 1897

In his attempts at salvation through self-deification as Orpheus, Rilke apotheosizes the poet as the singing savior who can redeem himself from the misery of his fragmentary existence. The Sonnets completed Rilke’s world view; while writing them he felt that the antinomies of his existence were transformed into a rhythmic event as he became Orpheus, a model of virtual connection. He dwells freely in a double realm, where opposites are reconciled in an eternal wholeness. The Sonnets reveal Rilke’s spirit rising above the doubt and despair into which he had initially plunged, with a final impression of liberation, harmony, and rhythmic equilibrium.

Rilke, Château de Muzot, Le Valais (Switzerland)

JUDITH ELEANOR BERNSTOCK

Under the Spell of Orpheus: The Persistence of Myth in Twentieth-Century Art

Click or tap the image to go to a description of the book

JUDITH ELEANOR BERNSTOCK

Under the Spell of Orpheus

PART II

RAINER MARIA RILKE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Four Chapter 6

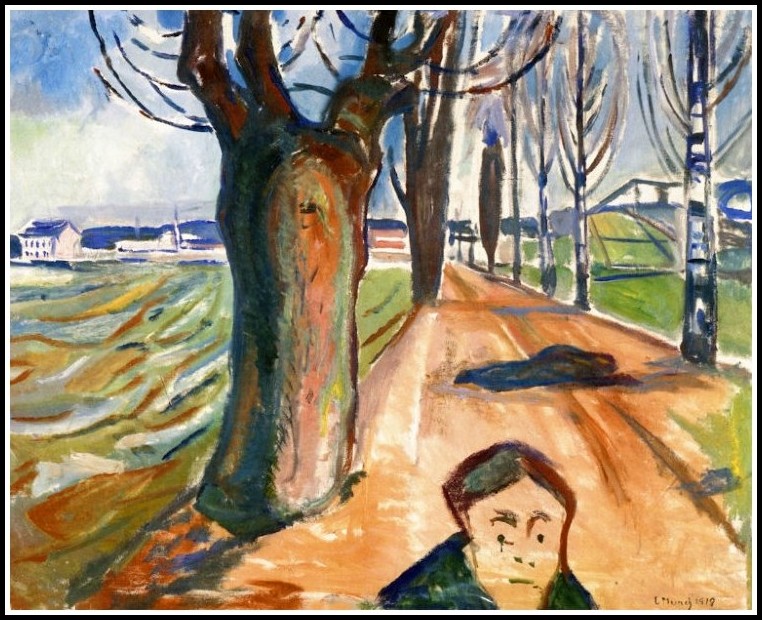

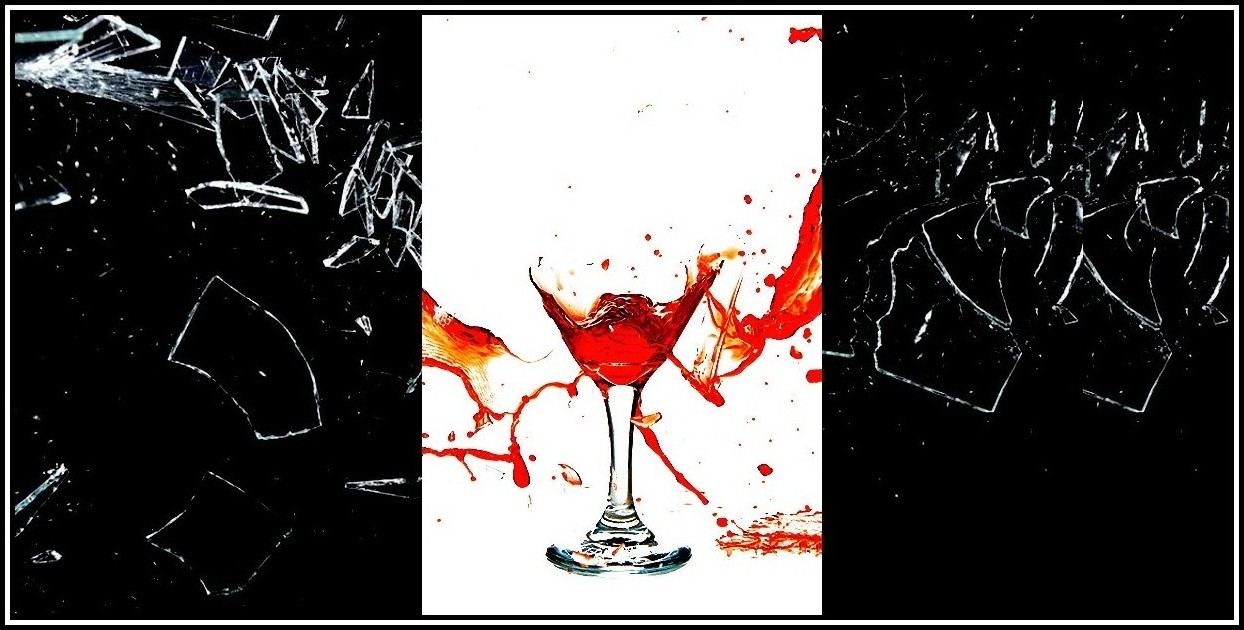

She swings around from the waist. Her mouth forms a word but her breath won’t come. Lowering the rifle a touch, the marksman tightens his finger on the trigger: Firing pin strikes percussion cap, powder ignites as primer explodes. ‘Be a resonant glass that shatters while it is ringing.’ The deflagration gases expel the bullet, sealing the cartridge case against the chamber wall. In the bore of the barrel the spiral grooves impart a spin to the projectile; out of the muzzle the bullet sizzles through the air. ‘Be a resonant glass that shatters while it is ringing.’ In its copper jacket the lead slug continues its flight. ‘Be a resonant glass that shatters while it is ringing.’ Scorching the skin, the bullet perforates the flesh and enters the body through the right shoulder. Tearing through the tissues, it passes through the scapula. ‘Be a resonant glass that shatters while it is ringing.’ Above the clavicle it passes, through the apex of the right lung, perforating the pulmonary artery and penetrating the pericardium—deep in the heart it comes to rest. Before the blood spills inside it, the shocked body has already surrendered: Your father’s mother is dead.

Edvard Munch, Murder on the Road, 1919

DIE SONETTE AN ORPHEUS – II: 13

Rainer Maria Rilke

Sei allem Abschied voran, als wäre er hinter

dir, wie der Winter, der eben geht.

Denn unter Wintern ist einer so endlos Winter,

daß, überwinternd, dein Herz überhaupt übersteht.

Sei immer tot in Eurydike –, singender steige,

preisender steige zurück in den reinen Bezug.

Hier, unter Schwindenden, sei, im Reiche der Neige,

sei ein klingendes Glas, das sich im Klang schon zerschlug.

Sei – und wisse zugleich des Nicht-Seins Bedingung,

den unendlichen Grund deiner innigen Schwingung,

daß du sie völlig vollziehst dieses einzige Mal.

Zu dem gebrauchten sowohl, wie zum dumpfen und stummen

Vorrat der vollen Natur, den unsäglichen Summen,

zähle dich jubelnd hinzu und vernichte die Zahl.

SONNETS TO ORPHEUS – II: 13

Rainer Maria Rilke | C.F. MacIntyre

Keep ahead of all parting, as if it were behind

you, like the winter that is just now passed.

In winters you are so endlessly winter, you find

that, getting through winter, your heart on the whole will last.

Be ever dead in Eurydice—arise singing

with greater praise, rise again to the pure relation.

Among the fleeting, in the realm of declination,

be a resonant glass that shatters while it is ringing.

Be—at the same time, know the terms of negation,

the infinite basis of your fervent vibration,

that you may completely complete it this one time.

To teeming nature’s store of used, as of dumb

and moldy things, to that uncountable count,

add yourself joyously, and annul the amount.

‘Be a resonant glass that shatters while it is ringing.’