The Poetic Image as a Bearer of Meaning

JEAN RHYS – VOYAGE IN THE DARK – INTRODUCTION 2

Carole Angier

Posted by kind permission of Carole Angier, eminent biographer of Jean Rhys, Primo Levi and W. G. Sebald; fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

From Carole Angier, Afterword to Jean Rhys, Voyage in the Dark (Penguin Classics, 2000) pages 157-165

Jean Rhys | From Voyage in the Dark, page 4

When Jean Rhys wrote Voyage in the Dark in the early 1930s she was in her early forties. She had returned to England from France, which she had sworn never to do. She made a second unhappy marriage; her daughter chose to live with her father, not with her; she fell into a deep pit of misery, and was drinking heavily. And yet this, her third novel, would be her youngest, warmest and most daring of all. That is the mystery of Jean Rhys. I was so struck by her mystery that I became her biographer. That did not solve the mystery, of course, but confirmed it. It convinced me that, as well as universal works of art, Jean Rhys’s novels were a quest for the truth about her own painful life. Behind each of them lies the question she gives to Antoinette in the last one, Wide Sargasso Sea: ‘Why do such terrible things happen?’ And with each her answer became more honest and less self-justifying. Jean Rhys’s work, in other words, seemed to me not just a great artistic progress but a great moral one: a growing-up she never managed in life.

Jean Rhys, 1977 | Photo: Paul Joyce

In her two earlier novels she had set out two different answers to her question. The first, Quartet, was the story of an unhappy love affair, like Voyage in the Dark.1 For a first novel it is astoundingly good—as an artist Jean was born fully formed, like Pallas Athene from the forehead of Zeus. But it is flawed by her demon of self-pity. The heroine, Marya, sometimes seems to us selfish and cruel, but she never does to the novel. All the ‘terrible things’ that happen in Quartet are the man’s fault, or the world’s, never her own. Marya is Jean’s first attempt at the heroine as innocent victim, and she fails. Only two years later came After Leaving Mr Mackenzie, and Jean’s second answer. Julia is no longer young and innocent; she is ageing, alcoholic and full of rage. She is Jean’s first attempt at harsh honesty about her heroine; and her ‘fifty–fifty lover’, Mr Horsfield, Jean’s first attempt at seeing a man’s vulnerability, a man’s point of view.

1 – And like Voyage in the Dark, based on one that had happened to her.

Paul Klee, Portrait of a Yellow Man, 1921

In the novel after Voyage in the Dark, Jean pursued her second answer: Sasha of Good Morning, Midnight plots a cruel revenge against men, and herself destroys her last chance of love. Finally, in Wide Sargasso Sea, the first answer returns—or rather, Jean finds an extraordinary resolution of the two. Antoinette is the maddest, most vengeful heroine of all: because, of course, she will become Bertha Rochester, the purple-faced destroyer of Jane Eyre. But in Wide Sargasso Sea itself she is an innocent victim, seen from inside: a child and little more than a child, broken by the hatreds in her own society, and by the encounter with a colder, harder one. Anna of Voyage in the Dark belongs to this answer. She is young and innocent, abused and abandoned by a man—but a weak and vulnerable man like Julia’s Mr Horsfield, not a monster of cruelty like Marya’s Heidler. Anna is more than halfway to Antoinette, almost a rehearsal for Antoinette: a heroine we meet as a child in the West Indies; and if she never grows up, at least we know why. Until the great resolution of Wide Sargasso Sea, Anna was Jean Rhys’s most successful innocent heroine, and she remained the most innocent of all. For that reason (I suspect) Voyage in the Dark was Jean’s own favourite among her novels.

Gwen John, Self-Portrait in a Red Blouse, 1902

After Mackenzie, Jean wrote to Francis Wyndham, her friend and future literary executor, ‘the West Indies started knocking at my heart.’ That was the new element that would transform our understanding of the heroine: her West Indian childhood. Jean’s first title for Voyage in the Dark reflected the importance of this new, or old, world in Anna’s story: Two Tunes, two musics which neither she nor Anna could ever fit together. By the end of 1931 she was ‘very down’, and put the novel aside. Finally she picked it up again some time in 1933, and finished it on ‘two bottles of wine per day’. Cape, who had published Mackenzie, turned it down. At last Michael Sadleir of Constable took it; but there was one last battle. He wanted to cut most of the final part, Anna’s stream-of-consciousness memories as her mind clouds; and—worst of all—he wanted Jean to change the ending. She was furious and frantic, but she did it. And Sadleir was right. Until Part IV she’d kept her (self-)pity for Anna under iron control, but in the end she’d let go: for in the original version, Anna dies. That made Voyage in the Dark a more cliched and sentimental story. With Sadleir’s change, the last trace of special pleading, of emotional blackmail of the reader, was removed; leaving a pure and perfect Jean Rhys novel.

Augustus John, Study for a Portrait of Gwen John, 1901

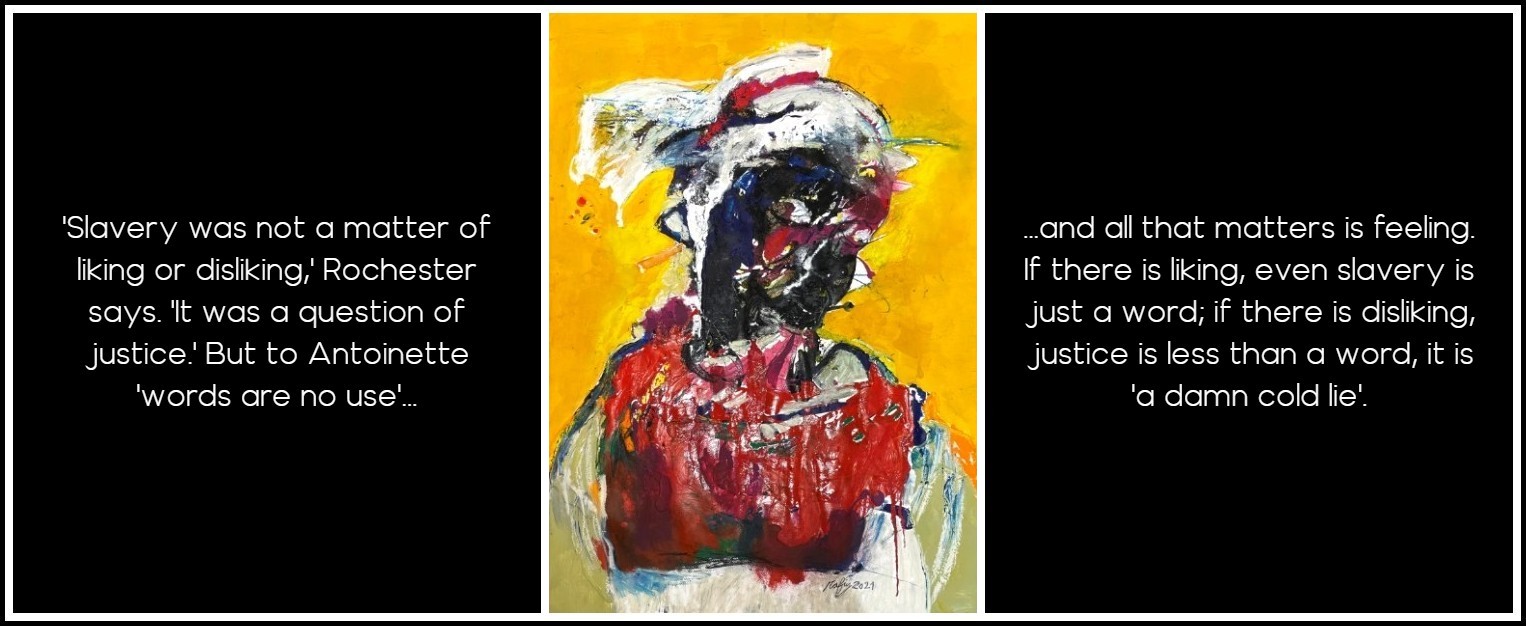

Anna is halfway to Antoinette not only in her successful innocence, but in her whole strange, new, subversive point of view. This is the heart of Jean Rhys’s daring, which is perhaps even greater in this novel than in Wide Sargasso Sea. Antoinette’s world is one of colour and sound, of light and dark, and of passionate, personal feeling—love, hate, happiness, fear. Rochester’s—and Walter Jeffries’—England is its opposite: a grey world of conformity, of words and rules, of money, ‘morality’ and law’. ‘Slavery was not a matter of liking or disliking,’ Rochester says. ‘It was a question of justice.’ But to Antoinette ‘words are no use’, and all that matters is feeling. If there is liking, even slavery is just a word; if there is disliking, justice is less than a word, it is ‘a damn cold lie’. That is already Anna’s world, and Anna’s feeling. Words and rules are meaningless to her. Morality is an advertisement on the back of a newspaper: ‘What is Purity? For Thirty-five Years the Answer has been Bourne’s Cocoa.’ All that matters is that when Walter kisses her, she is utterly happy. ‘I am bad,’ she thinks, ‘not good any longer, bad. That has no meaning, absolutely none. Just words.’ Yet like Antoinette, on a deep, wordless level she knows what is waiting for her: ‘But something about the darkness of the streets has a meaning.’

Rafiy Okefolahan, Portrait of a Soul 2, 2021

Now, the way that Jean tells Anna’s story is the perfect expression of this wordless point of view. In Quartet she had tried (a little) to generalize from Marya’s case, to seem to write for all underdogs, with their ‘drably terrible lives’. Not any more. She cut every ‘objective’ description, every logical connection, every general idea. We are wholly inside Anna: inside her feelings, her sensations, her memories; inside the vivid and sinister images that fill her mind. Even—especially—for her own acts there are no connections, and no explanations. As Uncle Bo says, ‘She sent us a postcard from Blackpool or some such town and all she said on it was, “This is a very windy place,” which doesn’t tell us much about how she is getting on.’ When Walter drops her she disappears without leaving an address, though she hasn’t a penny; she goes to Ethel, whom she fears and loathes, without telling herself, or us, why. It is like Antoinette’s dream: ‘This must happen.’ And underneath it is like Julia’s rage, and Sasha’s revenge: desperate, self-punishing pride. ‘You must have known that Walter would look after you,’ Vincent says. ‘So much every Saturday,’ Anna replies bitterly. ‘Receipt-form enclosed.’

Gwen John, The Convalescent, late 1910s (detail)

Jean Rhys was a writer who distrusted words. She used the fewest and shortest ones she could, as though she were trying not to use words at all: Voyage in the Dark, she said, was written ‘almost entirely in words of one syllable. Like a kitten mewing’. She put her meaning in what she does not say (she does not say ‘bitterly’, for example, in the exchange above), and in what her characters do not say (Are you sure these are all the letters?’ Vincent asks, removing all traces of Walter’s affair. ‘I’ve told you so,’ Anna replies. ‘Well, there you are, I’m trusting you,’ he says. ‘Yes,’ Anna says, ‘I see that.’) She put her meaning behind the words, like the menace all the heroines feel ‘under the more or less pleasant surface of things.’ And since it lurks hidden and wordless for us, as it does for them, we feel it in the same hidden and wordless way. We read Voyage in the Dark like this because we must, because that is how it is written. But Jean also tells us that that is how we should read it: or rather, she hints that that is how we should read it, through images of meaning. The first comes right at the start, in the first thing we see Anna do: she is reading a book ‘about a tart’, as Maudie says—which is, in cold external words, what we are doing too. And this is what Anna says about her reading: ‘The print was very small, and the endless procession of words gave me a curious feeling—sad, excited and frightened. It wasn’t what I was reading, it was the look of the dark, blurred words going on endlessly that gave me that feeling.’ That is how we must read Voyage in the Dark: attending to ‘looks’ and ‘feelings’, not to the words, which belong to the powerful, like the laws (and that, of course, is why Jean Rhys distrusts them).

Manet, Nana, 1877

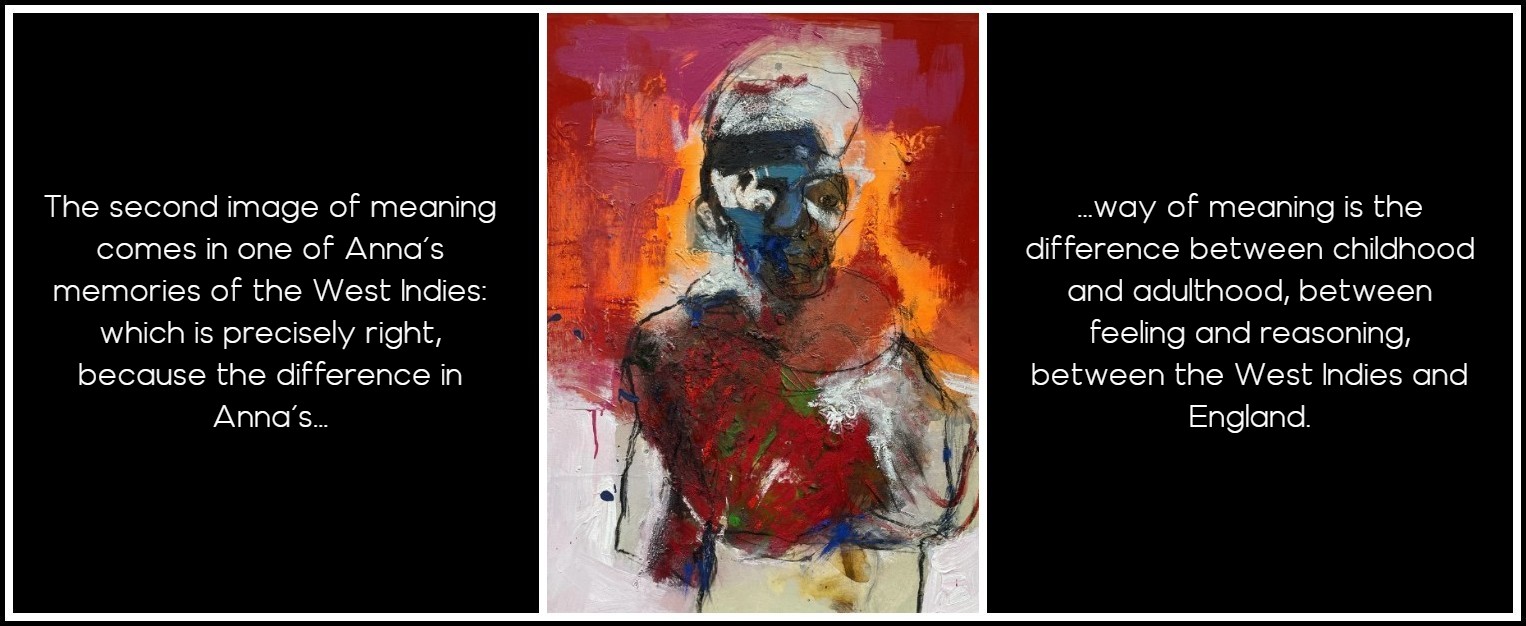

The second image of meaning comes in one of Anna’s memories of the West Indies: which is precisely right, because the difference in Anna’s way of meaning (and Antoinette’s, and Jean Rhys’s) is the difference between childhood and adulthood, between feeling and reasoning, between the West Indies and England. Anna’s stepmother, Hester, is the arch-Englishwoman, cold, snobbish and disapproving. Francine was the black servant girl of Anna’s childhood, who made her feel safe and happy, who made her want to be black. And this is Anna’s memory: Hester always hated Francine. ‘What do you talk about?’ she used to say. ‘We don’t talk about anything,’ I’d say. ‘We just talk.’ But she didn’t believe me. White people think that words mean what they say – what the words say. Jean Rhys knows they mean what they, the white people, say. Black people talk as they sing and laugh, to share their feelings; and they know that people, not words, mean things. That is the radical idea of meaning that informs Voyage in the Dark.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2021

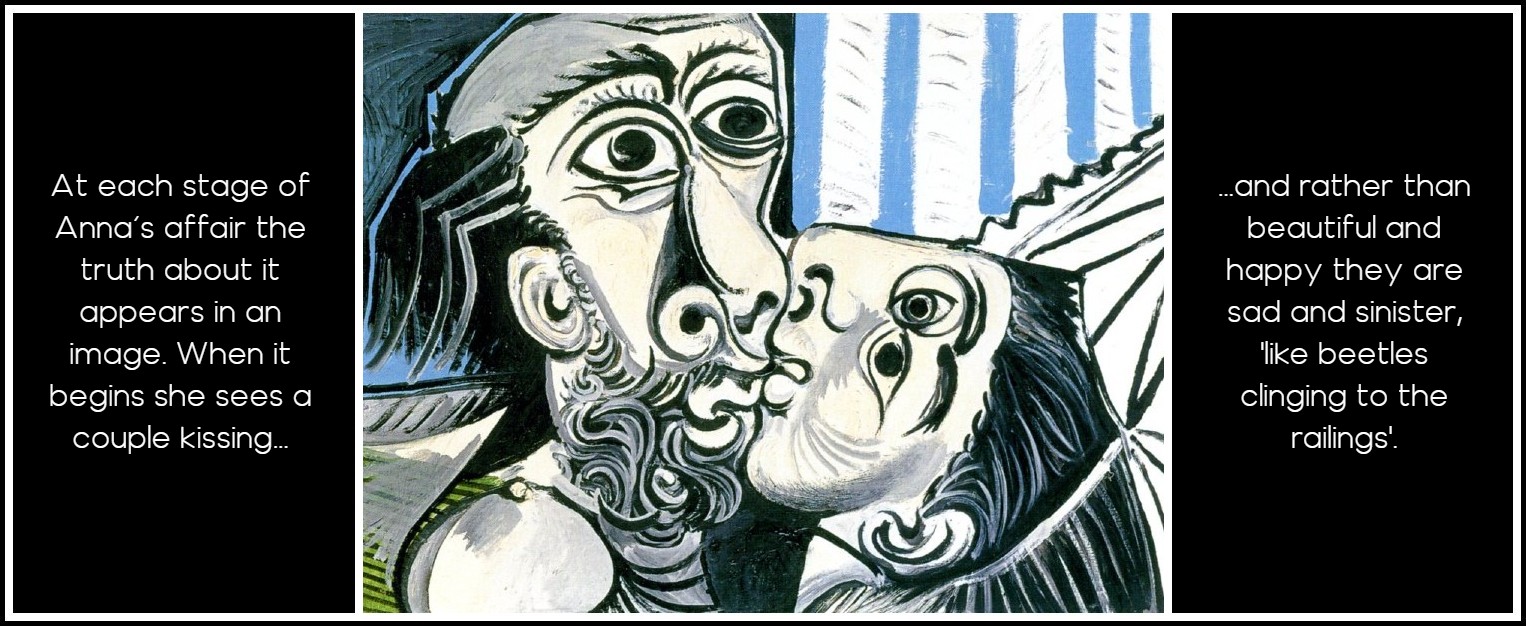

With all rational explanation cut, with the past as real as the present, Voyage in the Dark is close to poetry. And the main bearer of its meaning is a poetic one: imagery. At each stage of Anna’s affair the truth about it appears in an image. When it begins she sees a couple kissing: and rather than beautiful and happy they are sad and sinister, ‘like beetles clinging to the railings.’ When she sees the letter that will end it on her table, she remembers something that happened years ago: coming upon her favourite uncle asleep on the verandah, his mouth open. ‘Uncle Bo moved and sighed and long yellow tusks like fangs came out of his mouth and protruded down to his chin—you don’t scream when you are frightened because you can’t and you don’t move either because you can’t.’ ‘What the hell’s the matter with me?’ she thinks. ‘This letter has nothing to do with false teeth.’ But it has everything to do with a beloved face suddenly sprouting cruel fangs against you. This is what Anna has feared from the start, what she has always known would happen: ‘I’d been afraid for a long time, I’d been afraid for a long time.’

Picasso, The Kiss, 1969

The beetle-lovers and snake-uncle are part of a whole system of animal imagery in the novel. Ethel, the nastiest person of all, is an ant, ready to transform into a still more sinister and efficient insect: ‘Feelers grow when feelers are needed and claws when claws are needed and cunning when cunning is needed.’ Crabs lurked in the bathing pool of Anna’s childhood, like the monster crab in Wide Sargasso Sea; barracuda lurked in the sea, ‘flat-headed, sharp-toothed’, ‘swimming by the side of the boat, waiting to snap.’ Plants and trees, too, bulge with meaning. The shiny spiky red rubber plant expresses the smug hostility of Anna’s boarding house; trees throughout the story express her own state of mind—lopped, ‘like a man with stumps instead of arms and legs’, before she meets Walter; ‘perfectly still, as if it were dead’, when their affair is over. (Why did you make me want to live?’ Antoinette asks Rochester. ‘Why did you do that to me?’)

Photo: Matt Johnson, Unsplash

England, the apotheosis of power and possession, both everything Anna longs for—protection, security—and everything she fears—rejection, exclusion—England is a high, dark wall. English voices are ‘high, smooth, unclimbable walls’; the look in Vincent’s eyes is like ‘a high, smooth, unclimbable wall. No communication possible.’ All of this—the desired protection, the dreaded rejection—is summed up in another image, another memory: the picture on the English biscuit tin at home in the West Indies. A little boy, a little girl, a green tree, a blue sky; and behind the little girl a high, dark wall. ‘And that used to be my idea of what England was like,’ Anna says—thinking, we guess, of the safety and solidity of that high wall. ‘And it is like that, too,’ she thinks: with her, we know, on the other side of the wall. This flight from words to pictures is not just the perfect expression of Jean Rhys’s distrust of language, which someone else owns: it works. As long as she said things about society, about people, we could resist her, as we do in Quartet. But these fearful, enigmatic images slip under our conscious guard, and persuade us before we have noticed. Her genius was to cut everything she did less well, and use images.

Photo: Angela Baker, Unsplash

Anna is Jean Rhys’s most innocent heroine, but she is not as innocent as all that. She is extraordinarily passive, then suddenly, violently proud—turning on Laurie, jamming her cigarette on Walter’s hand. She is only nineteen, but she is already starting to drink (‘I should go slow on the gin if I were you,’ Laurie says, ‘You’ve been taking too much lately.’) And something else is starting too. When a man speaks to her on the street, she wants to hit him, and nearly does. ‘What happened to me then?’ she thinks. ‘Something happened to me then?’ What happened is that she has already moved from hurt child to vengeful woman; from herself to Julia, Sasha and Antoinette.

Photo: Lisa Horbach, Unsplash

And if Voyage in the Dark’s heroine is not unbelievably good, its villains are not unbelievably bad. When they are bad, they are utterly believable: Hester, Ethel and Vincent are so well observed we cannot doubt for a moment their smug, self-protective cruelty; and Vincent’s and Ethel’s letters are masterpieces of (respectively) smiling and spitting betrayal. But the other villains of the piece are hardly villains at all: Carl and Joe, who meet Anna as a tart and treat her as one, but who are decent, ordinary men, with struggles of their own (Nobody wins,’ Carl says, ‘Don’t worry. Nobody wins’); above all, Walter, whose abandonment of Anna ‘smashes her up’, as Marya was smashed up by Heidler, and Julia by Mr Mackenzie. Walter is cautious, cowardly and weak, he lets Vincent do his dirty work, and worries more about his health than about Anna. But he is more than half on Anna’s side; and like Rochester with Antoinette, briefly he forgets caution (‘Shy Anna, I love you so much. Always, Walter.’) Walter was based on the one man Jean truly loved; and that glimpse of the possibility of love—as much hers for another human being as his for her—produces her best balance. If you respond to her dark vision of haves and have-nots, of masters and slaves, you will want to read everything she wrote. But if you will only ever read one of her novels, I recommend this one.

Brassaï, Couple d’amoureux dans un café parisien, 1932

CAROLE ANGIER: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments