The Novelist, His Wife, and His Fantasized Lover

JOHN FOWLES ON THOMAS HARDY: EROTIC FANTASY IN MALE FICTION

John Fowles

From John Fowles, ‘Hardy and the Hag’ (1977) in his Wormholes: Essays and Occasional Writings, ed. Jan Relf (London: Vintage, 1998) 159-168

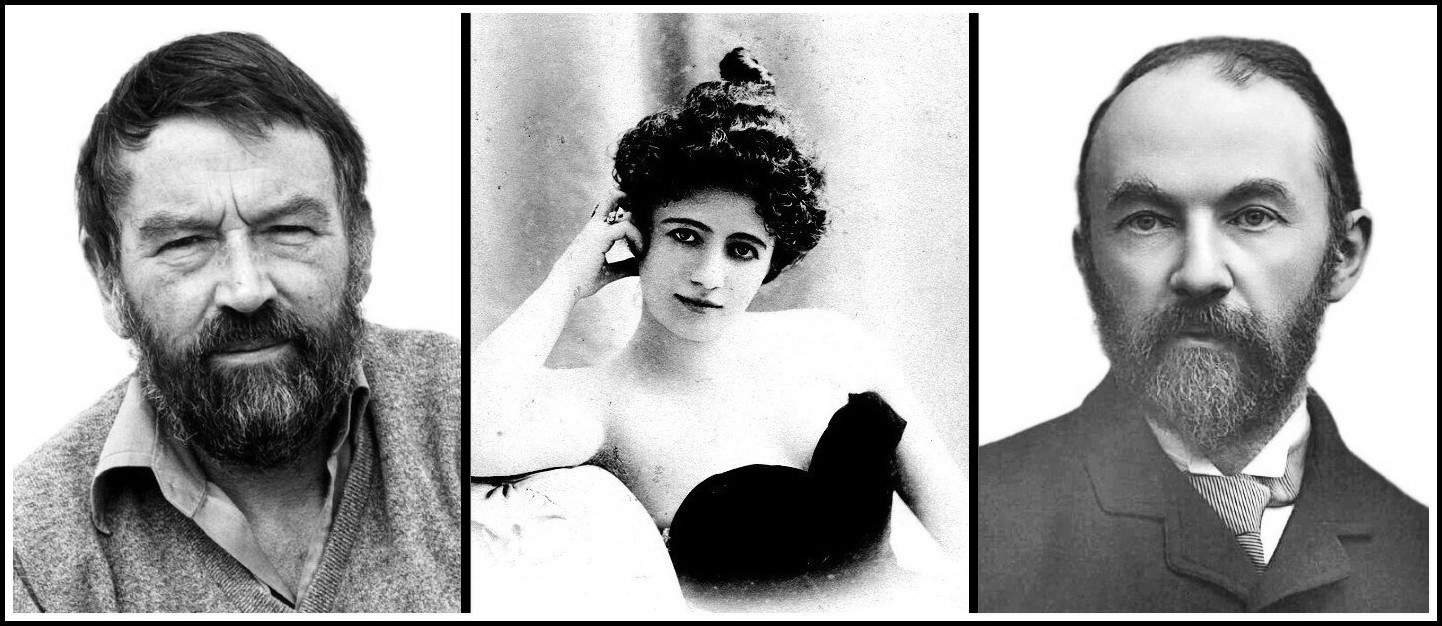

John Fowles, 1974 (Photo: Dmitri Kasterine) | ‘Ravishing Actress’ (Photo: Reutlinger, Paris) | Thomas Hardy, 1889 (Photo: H.R. Barraud)

I.

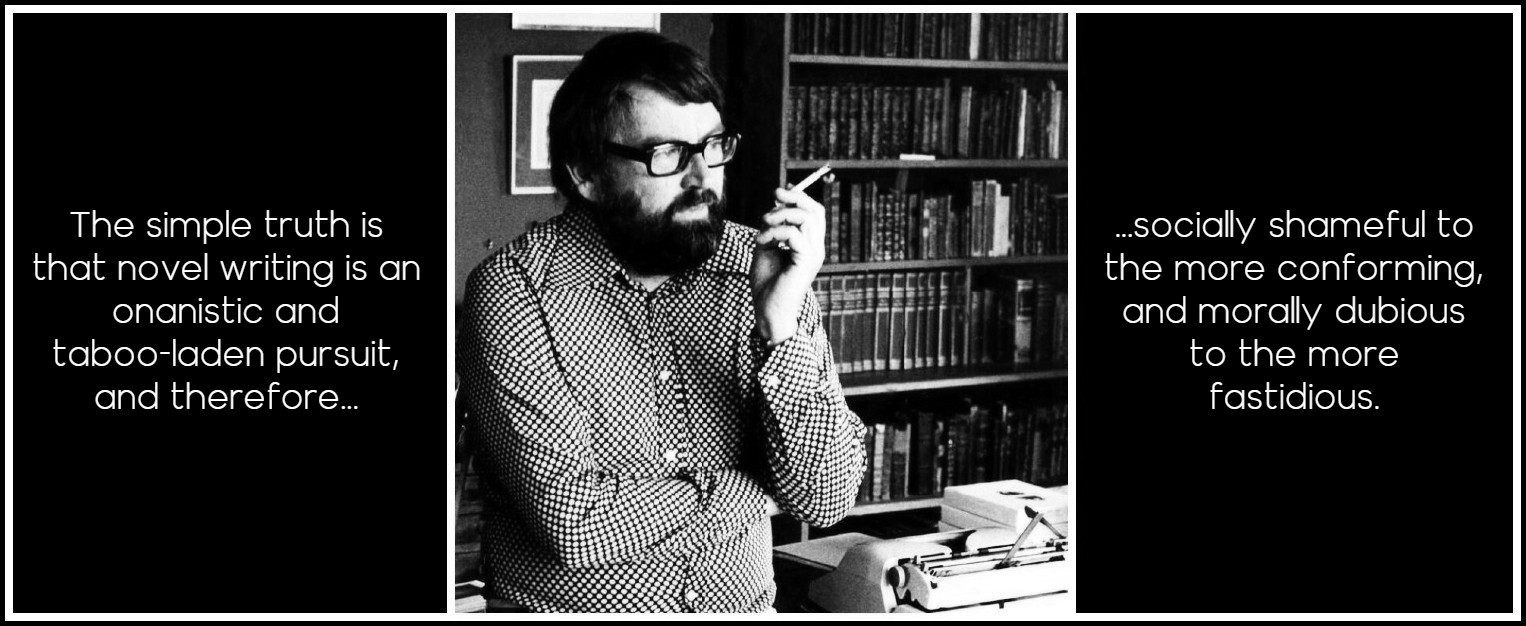

Most English novelists, however happy to indulge in literary gossip, are fanatically shy of talking of the realities of their private imaginative lives, just as they entertain an ancient preference for a narrating persona that is above all unpretentious and clubbable—a predilection that extends well beyond the strict arctic of the middle-class novel. I believe this proceeds far more from the cunning puritan in our make-up (our fear that investigation of the unconscious may lessen the pleasure we derive from being its playground) than from some fatuous association between amateurishness and gentlemanliness. The simple truth is that novel writing is an onanistic and taboo-laden pursuit, and therefore socially shameful to the more conforming, and morally dubious to the more fastidious. Hemingway’s is only an extreme case of the kind of public mask that knowledge of this truth forces most novelists to assume.

John Fowles, 1974 | Photo: Roger Mayne

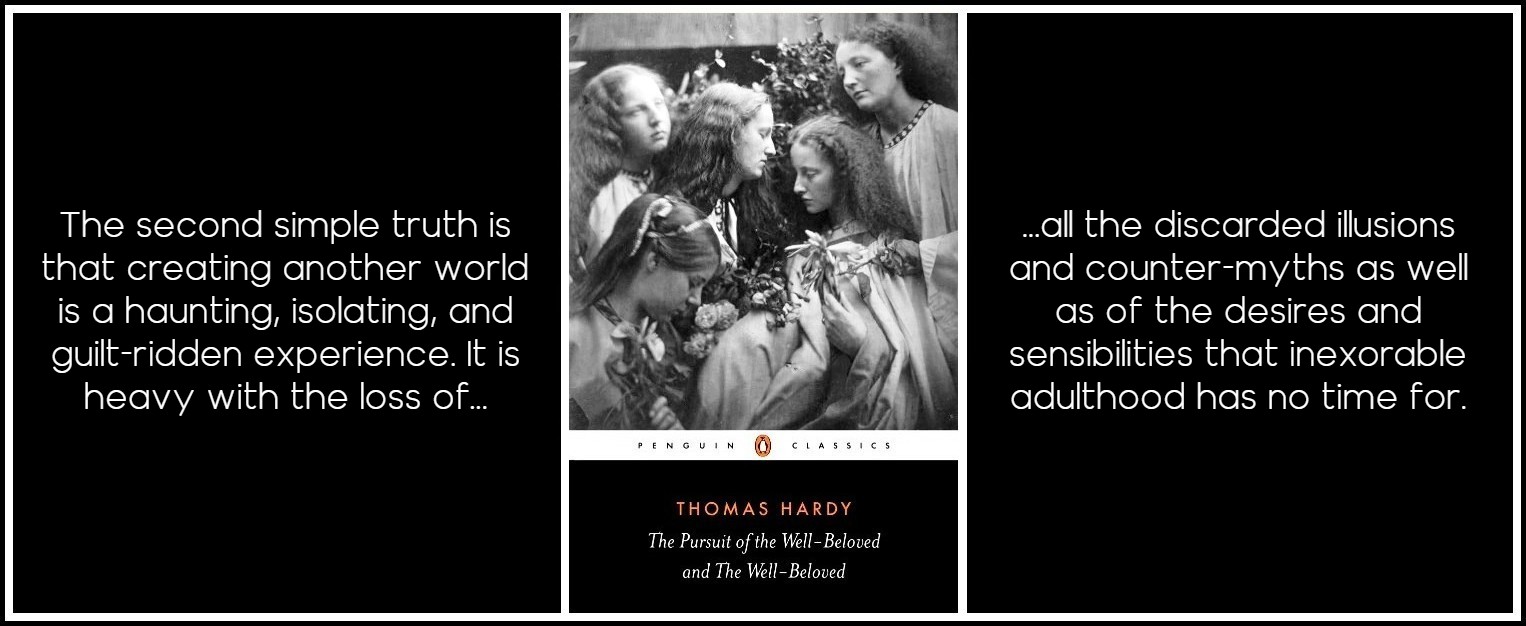

Yet we English have been so successful at the novel—and at poetry—very much because of this tension between private reality and public pretence. If the glory of the French is to be naked and lucid about what they really feel and make, ours is to be veiled and oblique. I do not see this as evidence of our finer taste and greater seemliness, I think we just enjoy it more that way, in bed as in books; for the second simple truth is that creating another world, however imperfectly, is a haunting, isolating, and guilt-ridden experience, very similar indeed to the creating of a ‘real’ perspective on the actual world that every child must undertake. As with the child, this experience is heavy with loss—of all the discarded illusions and counter-myths as well as of the desires and sensibilities that inexorable adulthood (or artistic good form) has no time for. The cost of it is a constant grumbling ground-bass in the Hardy novel I wish to consider, The Well-Beloved.1 Pierston/Hardy feels cursed by his ‘inability to ossify’, to mature like other men. He feels himself arrested in eternal youth; yet he also knows that the artist who does not keep a profound part of himself not just open to his past, but of his past, is like an electrical system without a current. When Pierston finally elects to be ‘mature’, he is dead as an artist.

1 – Readers who have not read Hardy’s novel will find it useful to read the Wikipedia entry on The Well-Beloved.

Thomas Hardy, The Pursuit of the Well-Beloved and The Well-Beloved, 1892 & 1897

A seriously attempted novel is also deeply exhausting of the writer’s psyche, since the new world created must be torn from the world in his head. In a highly territorial species such as the human, such repeated loss of secret self must in the end have a quasi-traumatic effect. This may be why, like many other novelists, I cannot think very critically of Hardy; there is too strong a sense of a shared trap, a shared predicament. In any case I have long felt that the academic world spends far too much time on the written text and far too little on the benign psychosis of the writing experience—on particular product rather than general process. Equivalents of the now-dominant ethological approach (the living behaviour) in zoology are sadly lacking in the world of letters. This is what I should like to try here with the Hardy of The Well-Beloved, not least because with this approach the artistically less excellent may often be the ‘behaviourally’ more revealing. I should add, first, that my main private interest in life has always been nature, not literature—understanding function rather than making value judgements—and second, that if I seem to cite personal experience too frequently, my aim is emphatically not to suggest invidious comparisons, but to try to explain a little the view from the inside, some of the natural, and unnatural, history of my peculiar subspecies.

Photo: Patrick Fore, Unsplash

II.

By supposing the ubiquitous skimping on technique and the almost algebraic impatience with anything but the basic formulae of his fiction to have been intentional on Hardy’s part, I have over the years tried to see The Well-Beloved as a black farce. But even if that was the original premise (as the very last lines of the 1892 version hint), its execution was badly botched. Taken straight, the book cannot be judged as anything but a disastrous failure by Hardy’s standards elsewhere. Despite the avuncular preface from 1912, The Well-Beloved, seething as it is with the suppressed rage of the self-duped, is fiction at the end of its tether. It is also the closest conducted tour we shall ever have of the psychic process behind Hardy’s written product. No biography will ever take us so deep. One thinks of Hoffmann, of the maker whose automata become so lifelike that they enslave him. But here it is a stage worse: the case of a god whose supposedly living Adams and Eves are now seen to be a tatter of trompe l’oeil, a creak of cogs and levers, and who can only abscond in horror from the realization that he himself is the arch-automaton. There is evidence that this grim revelation, accompanied by Hardy’s equally grim disillusion with his marriage, was dawning long before the 1892 version of the story. However, two failures in his own self-destructive logic in that version (to be mentioned later) suggest that he had not yet fully seen his ‘sickness’. There is also the striking enigma that the two versions of this technically worst novel span the writing of one of the finest, Jude the Obscure. That, too, I hope to explain in part.

Thomas Hardy, 1900 | Photo: Thomas Perkins

Hardy’s nightmare is painfully familiar to most contemporary novelists. The question of whether fiction is at the end of its tether is now universally in the air. It comes to us, far more consciously, as a nausea at the fictionality of fiction (less of a tautology than it may seem), or as a dread of once more entering an always ultimately defeating labyrinth. No further explanation is needed of the marked drop in fertility that has beset novelists during the last fifty years. The more you are aware of a hopeless obsession, the less you are driven by it. This is why The Well-Beloved is infinitely the most important of all Hardy’s books for a practising or intending writer of fiction to establish an attitude towards. The others, his far greater novels in ordinary terms, are now Victorian monuments, safe prey for the literary surveyors. The Well-Beloved still waits, potent, like a coiled adder on the Portland cliffs that brood distantly on where I sit, across Lyme Bay.

Thomas Hardy, 1905 | Photo: Clive Holland

III.

I had the interesting experience, a few years ago, of being psychoanalyzed by proxy—through one of my own novels, The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Professor Gilbert Rose, who teaches clinical psychiatry at Yale, wrote a good paper on the book, but I was rather more interested in his general theory of what produces the artistically creative mind, since it largely confirmed—and greatly clarified—intuitive conclusions of my own. In simple terms, his proposition was that some children retain a particularly rich memory of the passage from extreme infancy, when the identity of the baby is merged with that of the mother, to the arrival of the first awareness of separate identity and the simultaneous first dawn of what will become the adult sense of reality—that is, they are deeply marked by the passage from a unified magical world to a discrete ‘realist’ one. What seemingly stamps itself indelibly on this kind of infant psyche is a pleasure in the fluid, polymorphic nature of the sensuous impressions, visual, tactile, auditory, and the rest, that he receives; and so profoundly that he cannot, even when the detail of this intensely auto-erotic experience has retreated into the unconscious, refrain from tampering with reality—from trying to recover, in other words, the early oneness with his mother that granted this ability to make the world mysteriously and deliciously change meaning and appearance. He was once a magician with a wand; and given the right other predisposing and environmental factors, he will one day devote his life to trying to regain the unity and the power by re-creating adult versions of the experience: he will be an artist. Moreover, since every child goes through some variation of the same experience, this also explains one major attraction of art for the audience. The artist is simply someone who does the journey back on behalf of the less conditioned and less technically endowed.1

1 – Sensitive female readers may not be too happy about the pronoun used in this paragraph and below, but the theory helps to explain why all through more recent human history, men have seemed better adapted—or more driven—to individual artistic expression than women. Professor Rose points out that the chances of being conditioned by this primal erotic experience are (if one accepts Freudian theory) massively loaded towards the son. The novel is, of course, something of an exception to the general rule, but even there the characteristic male preoccupation with loss, non-fulfillment, non-consummation, is usually lacking in women writers. I can think of only two, among the great, who seem clearly to have been ‘fixed’ in the normal male way: Emily Bronte and Virginia Woolf. Perhaps the masculine component in their psyches was stronger.

Emily Brontë | Virginia Woolf

I find Professor Rose’s theory a plausible and valuable model. One enigma about all artists, however successful they may be in worldly or critical terms, is the markedly repetitive nature of their endeavour, the inability not to return again and again on the same impossible journey. One must posit here an unconscious drive towards an unattainable. The theory also accounts for the sense of irrecoverable loss (or predestined defeat) that is so characteristic of many major novelists, and not least of Thomas Hardy in particular.1 Associated with this is a permanent—and symptomatically childlike—dissatisfaction with reality as it is, with the ‘adult’ world that is the case. Here too one must posit a deep memory of ready entry into alternative worlds, a dominant nostalgia for what Hardy himself called metempsychosis.

1 – This sense of loss does not, however, give automatic birth to the tragic novelist. It may generate irony and comedy in the writer, and indeed has preponderantly done so in the English novel, perhaps because the comic is, given our national penchant for the veiled and oblique, a better public mask over the basic situation. Waugh and Nabokov exhibit interesting alternations of reaction—’tragic-naked’ and ‘comic-concealed’—in this context. Hardy evidently attempted the latter in The Well-Beloved. But the true comic novelist dulls the loss by mocking it.

Thomas Hardy, 1893 | Painter: William Strang

Beyond the specific myth of each novel, the novelist longs to be possessed by the continuous underlying myth he entertains of himself—a state not to be attained by method, logic, self-analysis, intelligent judgement, or any other of the qualities that make a good teacher, executive, or scientist. I should find it very hard to define what constitutes this being possessed, yet I know when I am and when I am not; know, too, that there are markedly different degrees of the state; that it functions as much by exclusion as by awareness; and above all, that it remains childlike in its fertility of lateral inconsequence, its setting of adultly ordered ideas in flux. Indeed, the workbench cost of this possession is revision—the elimination of the childish from the childlike, both in the language and in the conception. Like Venus with Cupid, each muse has her accompanying imp. It is also a state that withdraws (like the Well-Beloved) as the text nears consummation; and its disappearance, however pleased one may be with the final cast, is always deeply distressing: one other sense of loss, or reluctant return to normality, that every novelist-child has to contend with.

Photo: Patrick Fore, Unsplash

This obsessive need to find Pierston’s ‘conduit into space’—to transcend present reality—opens a Pandora’s box of associated problems in more ordinary life. One that I wish to discuss, partly because it is so generally ignored, and partly because I believe it very important with Hardy, is that of marital guilt. No one who spends most of his life in pursuit of a chimera can live comfortably with his everyday self or with that of the person closest to him. At one level he must know that for as long as he is on his voyage, the central emotional truth of his life is not where it should be; at another, that he is constantly, if only imaginatively, betraying his wife in other ports. It is easy to dismiss the first Mrs Hardy; but I have no doubt that she underwent many years of feeling herself shuffled off—in some cases, flagrantly travestied—by the man she had married. I am equally sure that, ‘drunk with the lure of love’s inhibited dreamings’, her husband knew it.

Thomas Hardy, 1914 | Photo: E.O. Hoppé

One may view the wife’s predicament in terms of an important sub-theme of The Well-Beloved: the conflict between the pagan and the Christian on Portland—Portland as the combined arena, peninsula-womb and domaine perdu of Hardy’s imagination. If the pagan there stands for permitted incest, premarital relations, the unchecked id, it also stands for consummation; and if the Christian stands for current social convention (as in the first Avice’s ‘modern feelings’ about staying chaste), the superego, and ‘mainland’ reality in general, it also forbids consummation—in other words, it forbids what Hardy as a writer needs to have forbidden. The role of a wife in this conflict (and some such polarized tension between creative ‘desire’ and social ‘duty’ will exist in every novelist’s mind) is complex. The one trait she possesses of the permissive pagan, available presence, is the very one the writer does not need; and in all else she stands against the cherished dream: she is the Marcia without make-up of the final chapter of The Well-Beloved, the ‘real’ reality, armed with the sanctity of the conventional institution and so on. Her function and value are therefore certain to be oxymoronic to her husband’s creative self: if she is potentially the strongest ally of his conscious, outward self, she can equally seem the greatest threat to his inward, unconscious one.

Thomas Hardy

There is a further complicating factor. An essential part of the novelist’s mental equipment is an iconogenic faculty that is crystalloid (repetitive of structure) in process—and that certainly, like the crystal, needs a stable nurturing culture. Although the wife is the mortal enemy of the mother as Ashtoreth-Aphrodite, she is also required to assume a rather more practical aspect of maternity, to be protective Jocasta against the cruel Laius of the review columns. This relationship is in my experience a far more important consideration in the writing and shaping of a novel than most critics and biographers seem prepared to allow. We must also remember that the voyage undertaken is back to an indulged primal self and all its pleasures, and that the main source of those pleasures was that eternal other woman, the mother. The vanished young mother of infancy is quite as elusive as the Well-Beloved; indeed she is the Well-Beloved, though the adult writer transmogrifies her according to the pleasures and fancies that have in the older man superseded the nameless ones of the child—most commonly into a young female sexual ideal of some kind, to be attained or pursued (or denied) by himself hiding behind some male character. In one extraordinary and very revealing early case, Hardy hid behind a female stalking horse, Miss Aldclyffe in Desperate Remedies. The transmogrification can also, of course, be vindictive, as in so much of The Well-Beloved, or in any novel where Eve is treated as the betrayer of Adam. Both transmogrifications, into the idolized love-object and into the unforgiven ‘whore’, may very often be seen side by side in the same novel.

Liane de Pougy, 1901

Against this constant emotional fugue must be set the real presence of the woman the novelist shares his life with. She is bound willy-nilly to take on the face of the moral (in Hardy’s case, the ‘Christian’) censor; and this can seriously alter both the shape of a particular text and the general tenor of the novelist’s career. I am convinced that this was the case with Hardy, who had the additional problem of a childless marriage to contend with. There is his lifelong need, self-parodied in The Well-Beloved, to avoid consummation. I cannot believe his reasons were solely artistic, or some effect of ‘natural reticence’; a much closer reality had to be placated. For me this plays an important part in explaining the extraordinary difference in the quality of his last two novels. I can see the two attempts at The Well-Beloved only as an admission of sin,1 and Jude the Obscure as a ‘recklessly pleasant’2 relapse into the enduring obsession—almost a case of a burglar’s so relishing his penitential memoirs that he is driven back to the old game. I do not know how Mrs Hardy could not have seen more of herself in Arabella than in Sue Bridehead; or, even in the intended mea culpa itself—since the obsession remained far stronger than the will to repent—more of herself in Marcia and in Nicola Pine-Avon (both ‘corpses’ as soon as they become amenable) than in the three Avices, even if she did not know they stood for the three Sparks sisters. In short, The Well-Beloved was written less for a public audience than to assuage a private guilt. This also explains a great deal of its cursory impatience with realism, and its obfuscating classification under ‘Romances and Fantasies’. Essentially the damage was long done, and the would-be ‘Christian’ husband must have known his cause was hopeless.

1 – Not least because the self-flagellation is so overdone. When Pierston terms the experience of the Well-Beloved as ‘anything but pleasure’, ‘a racking spectacle’, ‘a ghost story’, I must reach for the salt cellar. It is also noticeable that the flagellant’s loudest (and least convincing) cries are usually given a ‘Christian’ colouring: ‘I have lost a faculty, for which loss Heaven be praised!’

2 – Pierston feels the Well-Beloved shift from Nicola to the second Avice: ‘A gigantic satire upon the mutations of his nymph during the last twenty years seemed looming, but it was recklessly pleasant to leave the suspicion unrecognised as yet, and follow the lead.’

Woman Reading a Book, 1925

The only proof of real contrition would have lain in silence; and even the genuineness of that proof would be suspect, since self-exposure to his public in such matters must become more and more painful to a writer who was far from regardless of his conventional reputation and social status. I hasten to add that I am not suggesting Hardy would have been a finer writer if he had been less trammelled, more frank. In practical terms this form of marital censorship is far more generally a valuable check on excess—the real woman in one’s life symbolizing both social consensus and artistic common sense—than an unhappy stifling. But what must often remain, alas, is a reciprocal accusation: on the wife’s side—with far more justice—of imaginative infidelity and mauvaise foi, of being unfairly condemned as inadequate in a situation in which the desired adequacy (erotic elusiveness, unattainability) is plainly impossible; and on the husband’s side—much less reasonably—of lack of pity (plentifully demonstrated in Pierston for himself) over his ‘disease’. Fair-copying wives know far better than anyone else the extent to which texts are lived in the writer’s mind; and a final aggravating factor is the very specific and detailed way in which the novelist, given the length and dominance of realism in the form, is obliged to body forth his infidelity—‘the carnate dwelling-place of the haunting minion of his imagination’, in a stiffly embarrassed phrasing from The Well-Beloved itself. I suspect that one strong reason Hardy reserved himself to poetry after 1896 is precisely because verse is, in this context, a less ‘naked’ medium than prose: not an exposed field, but a shady copse.

Norman Parkinson, Wenda at the Peabody Buildings, 1950

IV.

Since it is in the nature of pleasure to wish to prolong itself, the writer will always invent obstacles (such as Hardy’s favourite hurdles, malign coincidence and class difference) to his hunt of the Well-Beloved—one further cruel-vital function for the wife, it may be noted. But because the real goal is eternally doomed to failure, its attainment no more feasible than that the words on the page can become the scene they describe, the fundamental nature of the hunt is tragic. The happy ending, the symbolic marriage between hero-author and heroine-mother, is in this light mere wish fulfilment, childish longing of the kind reflected in the traditional last sentence of all fairy stories. This is another major psychological dilemma (in his myth of himself) for the novelist, and one in which Hardy, by so often choosing the unhappy solution, foreshadowed our own century.

Horst P. Horst, Nina de Voogh, New York 1951

However, his choosing of the ‘reality’ as against the ‘dream’ cannot be explained simply in terms of a pessimistic temperament and a deterministic philosophy, of some put-upon Atreid cursing the unkind gods. To a psyche such as Hardy’s, both highly devious and highly erotic, it is not at all axiomatic that the happy consummation is more pleasurable. The cathartic effect of tragedy bears a resemblance to the unresolved note on which some folk music ends, whereas there is something in the happy ending that resolves not only the story, but the need to embark on further stories. If the writer’s secret and deepest joy is to search for an irrecoverable experience, the ending that announces that the attempt has once again failed may well seem the more satisfying. Like the phoenix, Tess in ashes is Tess, under another name, released and reborn. In the deeper continuum of an artist’s life, where the doomed and illicit hunt is still far more attractive than no hunt at all, the ‘sad’ ending may therefore be much happier than the ‘happy’ ending. It will be both releasing and therapeutic.

Thomas Hardy

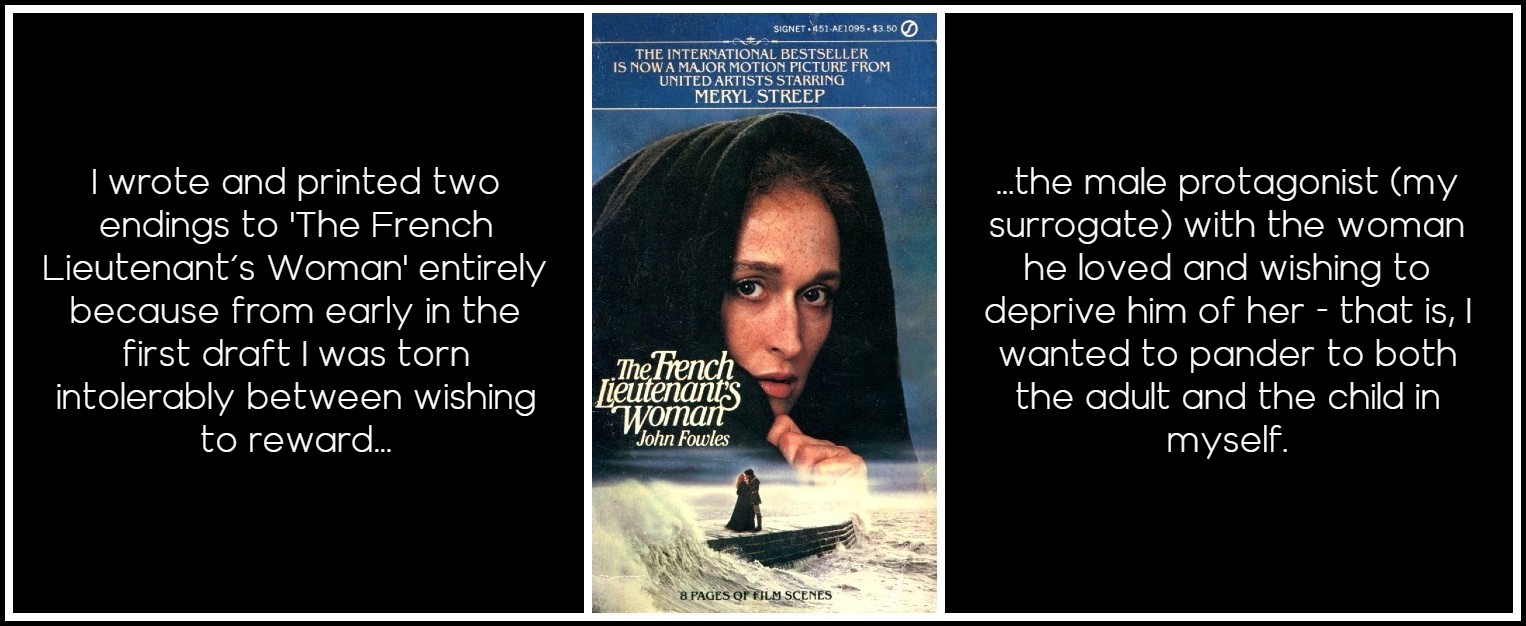

If this seems paradoxical, I can call only on personal experience. I wrote and printed two endings to The French Lieutenant’s Woman entirely because from early in the first draft I was torn intolerably between wishing to reward the male protagonist (my surrogate) with the woman he loved and wishing to deprive him of her—that is, I wanted to pander to both the adult and the child in myself. I had experienced a very similar predicament in my two previous novels. Yet I am now very clear that I am happier, where I gave two, with the unhappy ending, and not in any way for objective critical reasons, but simply because it has seemed more fertile and onward to my whole being as a writer.

John Fowles, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, 1969

From the very beginning, from the schoolroom of An Indiscretion, there can be seen in Hardy a violent distaste for resolution, or consummation. The chance of happiness is almost always put in jeopardy by physical contact, the first hint of possession. His two earliest heroines, Geraldine and Cytherea, both behave absurdly like startled roe deer when they are first kissed; and their continuing capacity for not fulfilling their respective lovers’, and the reader’s, expectations exhibits a striking lack of psychological realism in a young writer who already showed ample command of it with less emotive characters. Even here it is clear that Hardy finds his deepest pleasure in the period when consummation remains a distant threat, a bridge whose crossing—or collapse—can be put off for another chapter. I think it must be said that this endlessly repeated luring-denying nature of his heroines is not too far removed from what our more vulgar age calls the cock-tease. It is a very characteristic movement—advancing, retreating, unveiling, reveiling—of the meetings in The Well-Beloved, and like so much else, this is done with the angry disregard of a man forced to lampoon himself. The actual sexual consummations in both versions are totally without erotic quality, indeed are merely recorded by implication; and they bring nothing but disillusion to both partners.

Julia Margaret Cameron, Ellen Terry at Age Sixteen, 1864

This leads me to that most Hardyesque of all narrative devices: the tryst. The isolated meeting of a man and a woman, preferably by chance, preferably in ‘pagan’ nature and away from the ‘Christian’ restraint of town and house, preferably trap-set with various minor circumstances (whose introduction often shows Hardy at his weakest, as if emotional pressure choked invention) that oblige a greater closeness and eventual bodily contact—all this was transparently a more exciting concept than the ‘all-embracing indifference’1 of marriage. Significantly, Hardy always gives the trysting Well-Beloved the same physiological reaction, the rush of blood to the cheeks. This tumescent sexual metaphor is once again used to the point of self-satire in the present novel: Marcia is ‘inflamed to peony hues’, and so on. One may see a disguised death wish where the first bodily contact is so perversely made the secret trigger (not post, but ante, coitum tristitia) of the frustration and misery to come. But I suspect this predilection for the first faint erection of love, and the distaste for the thereafter of it, is one of Hardy’s most enduring attractions. He had his finger on a very common death wish, if such it is.

1 – The phrase is used of the second Avice’s marriage to Ike: ‘having as its chief ingredient neither love nor hate, but an all-embracing indifference’.

John William Waterhouse, Ophelia, 1889

The importance of the tryst becomes clear when we realize that the Well-Beloved is never a face, but rather the congeries of affective circumstances in which it is met; as soon as it inhabits one face, its erotic energy (that is, the author’s imaginative energy) begins to drain away. Since it cannot be the face of the only true, and original, Well-Beloved, it becomes a lie, is marked for death. In other words, the tryst is not the embodiment of a transient hope in the outward narrative so much as it is a straight desire for transience, since gaining briefly to lose eternally is the chief fuel of the imagination in Hardy himself. In The Well-Beloved this is shown in the highly voyeuristic treatment of the early relationship with the second Avice, and in the corollary masochistic—or ‘Christian’— misery of their life in Pierston’s London flat, where the girl is put, with a ghastly irony, to ‘dust all my Venus failures’.

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888

Plainly the tryst is also a scarcely concealed simulacrum of the primary relationship of the child with the vanished mother. In The Well-Beloved, when Marcia and Pierston retreat from the storm under the tarred and upturned lerret [rowboat], foetally crouched since they cannot stand, the model is particularly clear. He could ‘feel her furs against him’; he thinks of himself as playing Romeo to her Juliet, implicitly breaking a taboo far greater than that dividing two rival families. As they walk on to Weymouth, he goes on thinking ‘how soft and warm the lady was in her fur covering, as he held her so tightly; the only dry spots in the clothing of either being her left side and his right, where they excluded the rain by their mutual pressure’; and then finally there is the strange near-fetishist scene, the most overtly erotic in the book, when Pierston dries Marcia’s wet clothes at the inn, manipulating the veils while the baggageless dancer stands naked in his imagination, if not his sight, upstairs.

Pierre-Auguste Cot, The Storm, 1880

Nor can it be a coincidence that incest plays so large a part in the novel, not only in its triple-goddess central theme but also in the Portland setting. There are constant references to shared blood relationships; the second and third Avices live in Pierston’s natal house, even in his former room there. The kimberlin, or non-Portlander, is unmistakably associated with the Oedipal father, the frustrator of the dream, the intruder in the primal unity. In the 1892 version Hardy followed the lerret scene with the marriage of Pierston and Marcia instead of the more casual hotel liaison of the final revision. He also had Pierston marry the third Avice in the earlier text. These were both, it seems to me, errors of his unconscious, results of a lingering desire to give himself, behind his hero, some reward—characteristically enough, in the form of a sanction on the pagan by a ‘Christian’ institution. But on reflection he must have seen that this was the last novel—last novel indeed—in which he could indulge such conditioned wish fulfilment.1 When all is to reveal the tyranny, it is absurd to behave at its behest. One cannot exorcise witches—least of all the ultimate witch—by symbolically marrying them.

1 – Although there is an interesting relic of what one might call the sultan syndrome of male novelists in the final paragraph of chapter 8 in part 2, where Pierston thinks of ‘packing’ the second Avice off to school—finishing her in all senses!—and then marrying her and ‘taking his chance’.

Julie Delance-Feurgard, Le Mariage, 1884

This abnormally close juxtaposition, or isolating, of a male and a female character is so constant a feature of the male novel that I think it adds further support to Professor Rose’s theory. I know myself how excitement mounts as such situations approach, and how considerably their contrivance can alter the preceding narrative.1 It is a very grave fallacy that novelists understand the personal application of their own novels. I suspect in fact that it is generally the last face of them that they decipher. Just as the Well-Beloved passes from glimpsed woman to woman in our private lives, so it is with our characters. This is one other principal reason we can, as we grow older, kill them off with so little real pain. Creating an embodiment of the Well-Beloved is like marrying her, and she would never stand for that.

1 – Although I gained the outward theme of The Collector from a bizarre real-life incident in the 1950s, similar fantasies had haunted my adolescence—not, let me quickly say, with the cruelties and criminalities of the book, but very much more along the lines of the Hardy tryst. That is, I dreamed isolating situations with girls whom reality did not permit me isolation with—the desert island, the air crash with two survivors, the stopped lift, the rescue from a fate worse than death, all the desperate remedies of the romantic novelette—but also, more valuably, countless variations of the chance meeting in more realistic contexts. A common feature of such fantasies was some kind of close confinement, as in Hardy’s lerret, where the Well-Beloved was obliged to notice me; and I realize, in retrospect, that my own book was a working-out of the futility, in reality, of expecting well of such metaphors for the irrecoverable relationship. I had the very greatest difficulty in killing off my own heroine; and I have only quite recently, in a manner I trust readers will now guess, understood the real meaning of my ending, Of the way in which the monstrous and pitiable Clegg (the man who acts out his own fantasies) prepares for a new ‘guest’ in the Bluebeard’s cell beneath his lonely house.

Émile Friant, Les Amoureux, 1888

In his biography Young Thomas Hardy, I was taken to task by Dr Robert Gittings for having swallowed whole the Tryphena ‘myth’. Although I would, accepting both the biographical and the autobiographical evidence in The Well-Beloved itself, concede at once that the likelihood of there having been only one Tryphena in Hardy’s life is non-existent, I remain a total apostate when it comes to dismissing this type of experience as unimportant. The reference to Tryphena’s death (in 1890) in the preface to Jude the Obscure cannot be ignored; nor can I think what else, or who else, could have delayed the smashing of the psychic generator, apparently already decided on by 1889, to enable that last great output of fictional power. There is reinforcing evidence of her potency in the present book, in the scene (part 2, chapter 3) where the London high society in which Pierston finds himself fades to nothingness before the ‘lily-white corpse of an obscure country-girl’; he refers to the ‘almost radiant purity of this new-sprung affection for a flown spirit’. The very title of the chapter—stylistically one of the best-written and emotionally one of the most deeply felt in the book—is ‘She Becomes an Inaccessible Ghost’.

Thomas Hardy, Jude the Obscure, 1895

If the Well-Beloved ever took a quasi-perennial ‘carnate’ form in Hardy’s life, I believe it was in the ‘charm idealized by lack of substance’ of the Tryphena of the Weymouth summer of 1869.1 The outward of the Well-Beloved may flit from shape to shape, but she is also a spirit, and spirit inheres much more tenaciously in its most powerful original manifestation. Pierston says of the second Avice that ‘he could not help seeing in her all that he knew of another, and veiling in her all that did not harmonize with his sense of metempsychosis’. And when the second Avice later plays tacit procuress, at Pierston’s command, to her own daughter, we are surely to see that the Well-Beloved, if discontinuous in the epiphany, is one in the genesis. After all, it is not only novelists who cherish and recall first loves most dearly and deeply.

1 – Lack of substance was already inherent in the affair long before the final separator, Emma Gifford, appeared, in March 1870. Tryphena’s hopes of going to Stockwell Normal College, and the strict propriety of conduct expected of candidates, must have borne a ‘Christian’ connotation for Hardy. Already loss offered itself, and the frustration of the pagan-permissive.

Emma Gifford | Thomas Hardy | Tryphena Sparks | Source: Ralph Pite, Thomas Hardy: The Guarded Life (London: Yale University Press, 2007) Composite: RJ

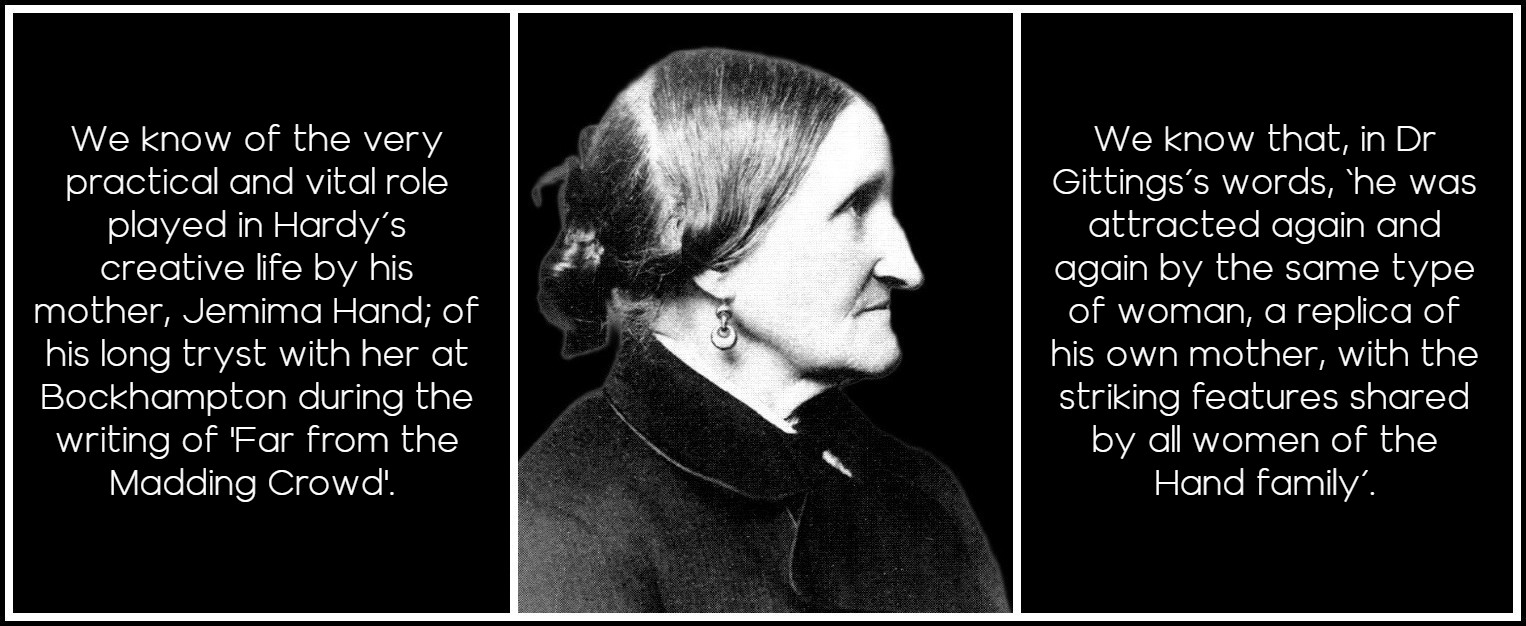

We know of the very practical and vital role played in Hardy’s creative life by his mother, Jemima Hand; of his long tryst with her at Bockhampton during the writing of his first indisputable masterpiece, Far from the Madding Crowd. We know that, in Dr Gittings’s words, ‘he was attracted again and again by the same type of woman, a replica of his own mother, with the striking features shared by all women of the Hand family’—of which one was the eyebrows like musical slurs reflected in the ‘glide upon glide’ Hardy used to describe the heroine of the novel he was writing during the 1869 summer. We know of his previous attraction to Tryphena’s sister Martha; know how closely a dry shrewdness in each of the Avices echoes a similar quality in the three sisters of real life and in Jemima herself; how exactly the social differences between the second and third Avices parallel the ‘peasant’ and ‘educated’ sides of Tryphena. We also know how resolutely Hardy ostracized his ‘pagan’ relations after the mid-1870s—thus making his continuing use of them in his fiction and his imagination doubly illicit. Hardy may have seen the emotional tug-of-war between Emma Gifford and Tryphena in the early 1870s only in terms of pain and suffering; but it seems clear that this is where the Well-Beloved first consciously manifested herself in his life, never to leave it again. Marriage simply meant that her lasting dominance was assured, and that his wife from then on was condemned to the punishment foreshadowed in the poem ‘Near Lanivet 1872’: ‘In the running of Time’s far glass, / Her crucified…’

Jemima Hand, Thomas Hardy’s Mother, 1876 | Photo: W. Pouncy

Of course it would be absurd to suppose that Hardy ever realized who truly lay behind Tryphena and all the other incarnations of the Well-Beloved, and indeed I suspect that the power—and frequency—of a novelist’s output is very much bound up with his failing to realize it; and that we later novelists have yet to come to terms with that knowledge. If ignorance here can hardly be termed bliss, it is certainly more fertile.1 The difficult reality is that if in every human and daily way (‘In one I can atone for all’), the actual woman in a novelist’s life is of indispensable importance to him, imaginatively it is the lost ones who count, first because they stand so perfectly for the original lost woman, and second (but perhaps no less importantly) because they are a prime source of fantasy and of guidance, like Ariadne with her thread, in the labyrinth of his other worlds.

1 – Thus, in my view, the characteristic abundance of the Victorian novel—and novelist—can be partly attributed to the taboo on sexual frankness, which in turn prevented the potentially inhibiting awareness of underlying psychic process. In short, outward sexual ‘honesty’ in the novel may be creatively far more limiting (or lethal, if The Well-Beloved is to be believed) than we generally imagine.

Edward Burne-Jones, Love in a Tangle, 1885

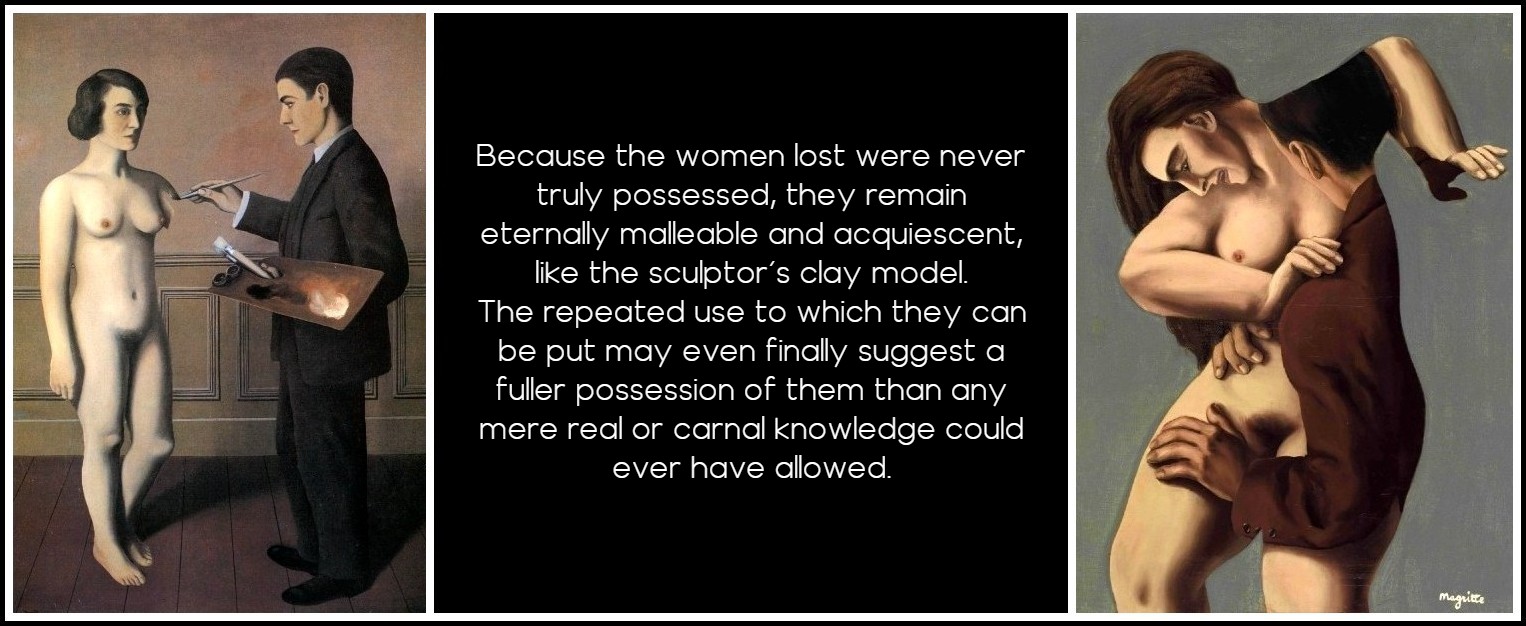

Because they [the women lost] were never truly possessed, they remain eternally malleable and acquiescent, like the sculptor’s clay model. The repeated use to which they can be put may even finally suggest a fuller possession of them than any mere real or carnal knowledge could ever have allowed. And this above all is why, to the extent that a creator of fiction needs such a figure behind his principal heroines, he is unlikely to want to grant her even imaginary happiness at the end of the narrative; and must therefore deny it to himself in the male character who is his surrogate. Hardy seems to have grasped this indispensable corollary under the shock of the suicide of Horace Moule in 1873, since it is first clearly enunciated in the fate allotted Farmer Boldwood. From then on, the doomed and thwarted child sits firm inside all his major male characters. They too become phoenixes, sacrificed so that their sacrificer may once again summon up the Well-Beloved and her further victim. Lost, denying and denied, she lives and remains his; given away, consummated, she dies.

Magritte, Tentative de l’impossible, 1928 | Magritte, Les jours gigantesques, 1928 (detail)

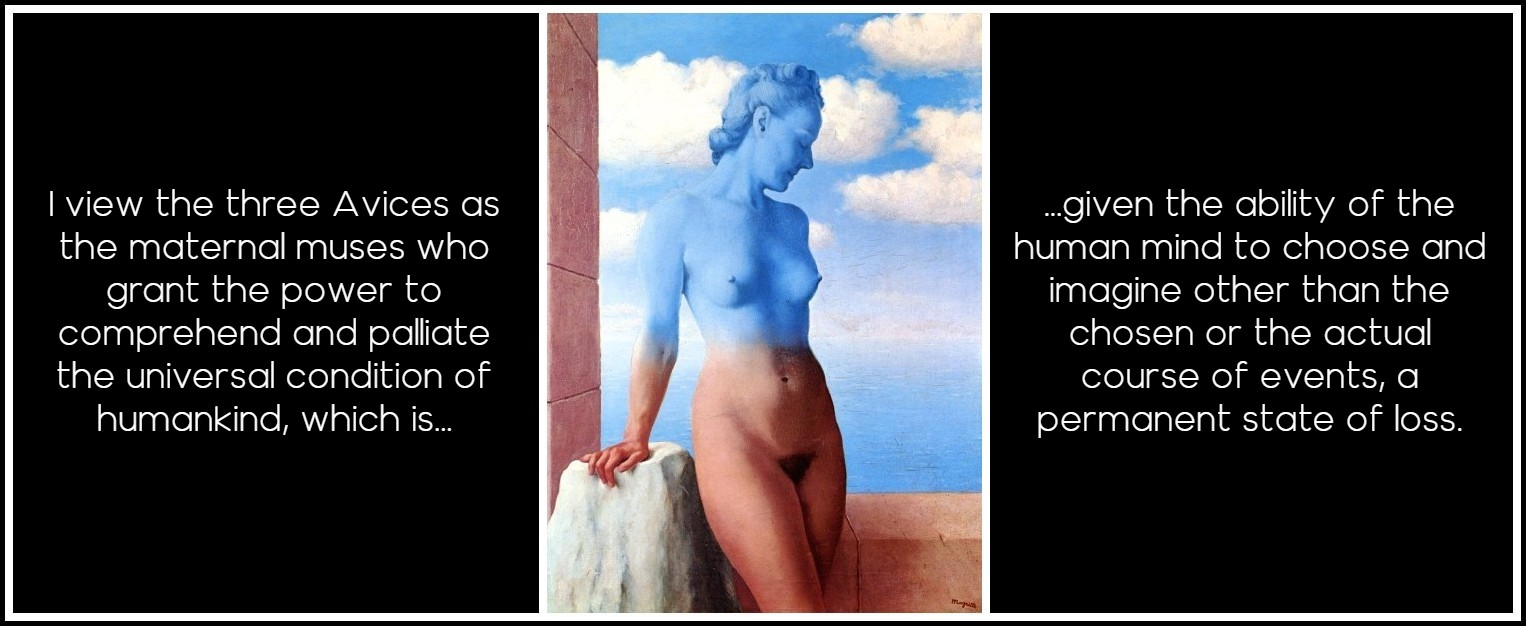

This is the redeeming secret behind all the self-disgust in The Well-Beloved. If superficially the three Avices may be seen (by the reader) as sadistic sirens, luring the poor sailor to his death in the Race, or (by Pierston-Hardy) as the trumpery puppets of his own morbid and narcissistic imagination, more deeply I view them as something quite contrary: the maternal muses who grant the power to comprehend and palliate the universal condition of humankind, which is, given the ability of the human mind to choose and imagine other than the chosen or the actual course of events, a permanent state of loss. I spoke earlier of the book’s lying like a coiled adder on the cliffs of the Isle of Slingers, but I think finally that it contains its own antidote; it remains a grave warning, but against the sailor, not the voyage. And then surely, in the last account, one has to smile. Who, faced with the hell of being a true and deeply loved artist (‘How incomparably the immaterial dream dwarfed the grandest of substantial things’) and the paradise of being Mr Alfred Somers, that ‘middle-aged family man with spectacles’, painting for the ‘furnishing householder through the middling critic’, would not still rush to tryst with the hag, and book a seat on the first broomstick down to Bockhampton?

Magritte, La magie noire, 1935

JOHN FOWLES: THREE NOVELS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE NOVEL

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments