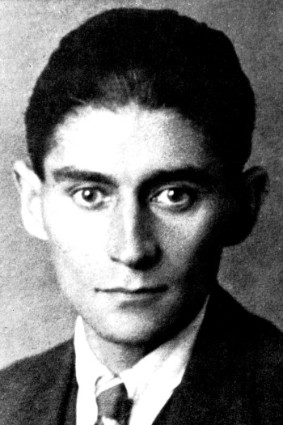

JOHN FOWLES

A Conversation with Fowles on the Art of Fiction

JOHN FOWLES INTERVIEWED BY SUSANA ONEGA

Posted by kind permission of Susana Onega, Professor Emeritus, University of Zaragoza

From Dianne Vipond, ed., Conversations with John Fowles (University Press of Mississippi, 1999). The interview took place in Zaragoza, during the 10th Conference of the Spanish Association for Anglo-American Studies (16–19 December 1986). It originally appeared in Actas del X Congreso Nacional de A.E.D.E.A.N., 1988, and was subsequently published in Susana Onega, Form and Meaning in the Novels of John Fowles (U.M.I. Research Press, 1989). The interview was also published as ‘Fowles on Fowles: An Interview’ in Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses 17(1988): 175–190. It is slightly abridged here.

Susana Onega: In an interview with Lorna Sage you talked about a tension in your work, an opposed pull between the English, realistic tradition, and your French, experimental background. What are the basic ideas you have accepted from each and to what extent have they conditioned your literary evolution?

John Fowles: When I was much younger I taught in a French university for a year and I was supposed to teach English there. Now I was a disaster as a lecturer at that university because I really knew nothing about English literature. I did know a little, I had been to Oxford and had studied French literature and I knew French novels and that country historically quite well, but when I suddenly had to get up and start talking about Shelley, Keats, Byron, and Rupert Brooke, whatever was on the French syllabus in the English Faculty, I was absolutely at sea. I ought never to have been appointed. In fact, at the end of that year the university said goodbye to me with no regrets at all. I then went to Greece, and the school in Greece where I taught also said goodbye to me at the end of my stay there—in other words, I was sacked, or fired. That was for rather different reasons but I think, in general, it is quite good for novelists to have failures like that early in life. What you have to do if you are to be a novelist is not to be a teacher.

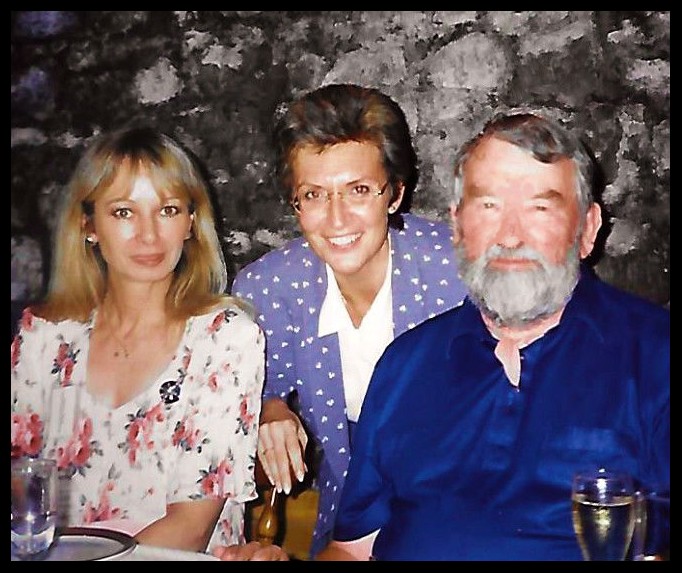

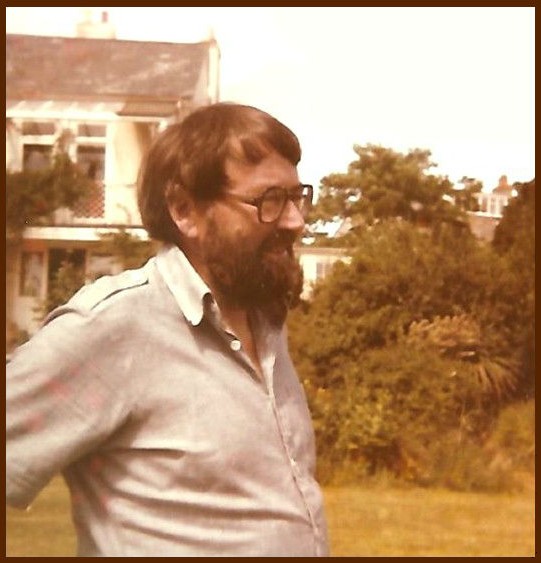

John Fowles, Belmont House, Lyme Regis, 2001 | © Susana Onega

John Fowles: There is a theory in England that if you want to be a novelist—and it is even stronger in the United States—that all would-be writers go ‘on campus.’ They go to university and they do not earn their living from books, they earn it from some job they have in a university. I think teaching is a very bad thing for a creative writer to do, if we are talking about it as a career, and whenever young novelists in England say, ‘What advice have you got?,’ I always say, ‘Anything, but don’t be a teacher.’ It is curious because obviously teaching a language with its literature and writing might seem to be parallel and close activities, but in some ways teaching literature is a very bad basis for actually writing or creating literature. This is why you do not get many professors of literature who are really good writers in a creative sense. There have been one or two. We have two famous professors of English in England at the moment who are also good writers. One is Malcolm Bradbury and the other is David Lodge, but they are exceptions to the rule. There have been one or two in America, too. Lionel Trilling in America was a famous critic and teacher of English as well as a novelist, but on the whole you do not learn to write books by being good at analyzing them and explaining them. That may seem strange to you, but, believe me, it is true.

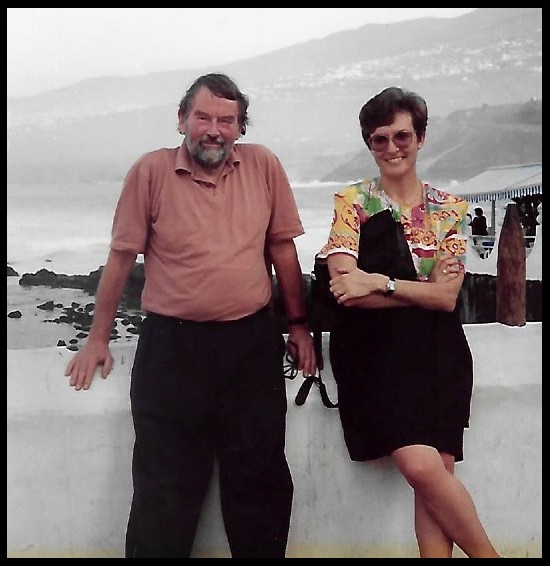

John Fowles & Susana Onega

Belmont House, Lyme Regis, 2001 | © Susana Onega

Susana Onega: Do you think every novelist, even the most experimental one, should write only about things and places he has first-hand knowledge of? Or to put it another way, do you think that real life experience is as necessary as genius?

John Fowles: I think for the young writer it is important. I am greatly in favor because I am an internationalist by spirit. I think it is very important for young writers, I would say for all young people really, to travel. I traveled a lot when I was young, but I am now at an age when I have a little bit of that complacent syndrome, I have seen everything and I have read everything. This is a danger when you get to my age. I am sixty years old at the moment [the interview, as mentioned in the credits, took place in December 1986]. You think you have travelled everywhere and you will get no new experiences, but this is not true, as I have just learnt in Spain. It is really more than that. I am at the moment thinking, no more than tossing around in my mind, an idea for a new novel and I find coming to Spain lovely and fertile for the writer. All feeds in, objects you see suddenly attract you and you think, ‘My goodness, I could use that!’ or ‘That’s something I must remember.’ So, this is why I am always persecuting my very kind hosts here about strange words I see, or habits. Novelists are magpies and steal objects if they can. We really have to be magpies, and amass masses of information we will never put in our books and perhaps will never use. If you have a novelist’s mind it is rather like owning a junk room in a house or an old brocante, an old second-hand dealer’s. In some way you have got to have this room full of old furniture, in our case events and characters, characters you have never developed. Then suddenly one day you feel there will be a place for such and such a character or event.

John Fowles & Susana Onega, Tenerife, 1991 | © Susana Onega

Contemporary Literature Conference, University of La Laguna

John Fowles: This, I think, is one important way we really are very, very different from professors, teachers of English. I feel I am a sheep among goats here in Zaragoza, or a goat among sheep. A novelist is truly very different from an expert on literature. We do not have to have ordered minds, we do not have to know Derrida or Barthes or the great theorists backwards, we have very loose ideas, a mass of mixed information that is really of no use to us or anybody else, but we have to carry round our minds stuffed with these facts. You have to have a private treasury, a house which is full of objects or memories that one day may be useful—may be useful, you may use them, or they may disappear and sink out of sight. It is by writing like this that we get an important response with that other person, the reader. The novelist does not have a relationship with readers, in the plural. We have to remember it is always with one reader and that reader you have to tickle as you ‘tickle’ a trout, you have to evoke a world, to tease their emotions. You are appealing in most novels, I think, to the corresponding junk-room nature of the reader’s mind from your own. It is not by theory, by logic, by order, as a rule, that you establish this communion with this one reader who is your brother or sister in the experience of reading a book.

Dianne Vipond, Susana Onega & John Fowles

Symposium in Lyme Regis, 11 July 1996 | © Susana Onega

Susana Onega: You have often explained that some of your novels developed from a single image: The French Lieutenant’s Woman, for example, developed from the image of a woman standing on the quay at Lyme Regis, and looking out over a rough sea; or The Collector, from a piece of news in the papers about the kidnapping of a young woman who was held prisoner in an air-raid shelter in London. Did any of the other novels also originate in a similar way?

John Fowles: It used to happen to me by something like a cinema ‘still.’ I used to get one vision. In another novel, one of my favorite novels, in fact, Daniel Martin, I did have an image that in the novel is at the very end of the book. It was of a woman standing in a desert somewhere. I did not at that time even know where it was. She seemed to be weeping, to be lost, a moment of total desolation. It is from tiny images like that, very like cinema stills, say good Buñuel stills or Eisenstein stills, the way they can evoke the whole film even though there is only one frame, one picture. That seems to have some effect on me. I do not think this is true of many novelists, it is just a peculiarity of my own. I am a visual person in other ways. I would normally much rather go to an art gallery than sit on a literary discussion. Pictures have always spoken to me, in emotional terms anyway.

Catherine Deneuve, Tristana, Luis Buñuel

Susana Onega: In The French Lieutenant’s Woman the narrator protests that he cannot control his characters, and that once created, they are free to choose what they do; if you agree with your narrator, the obvious conclusion is that you do not have a preconceived plan when you start writing a novel, that you haven’t decided the ending beforehand. Is that right?

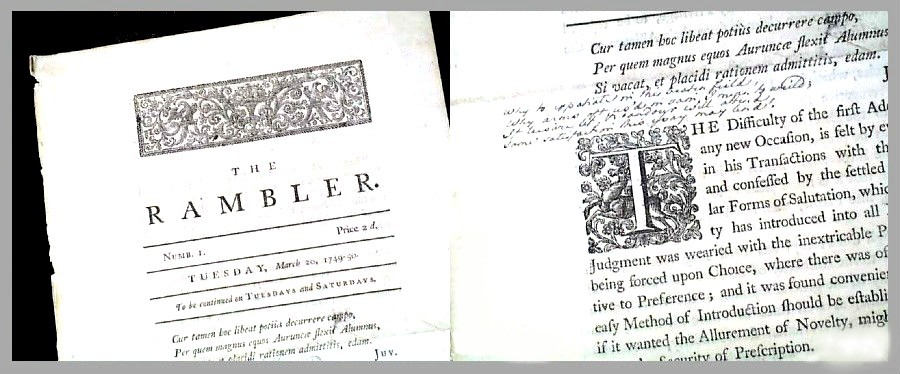

John Fowles: Yes. Again please remember this is one person speaking to you and that you must not take this as applying to all novelists. I know others do write to carefully preconceived, prepared plans, and if you read books on how to write a novel, usually they will say, ‘Make a careful plan and keep to it.’ I am completely different. I am, I suppose, a wanderer or a rambler. The Rambler was a famous eighteenth-century periodical in England and the title has always attracted me. The wanderer, the person who strolls and deviates through life. I always think the notion of the fork in the road is very important when you are creating narrative, because you are continually coming to forks. Now, if you write to an elaborate, prepared plan, the choice is taken out of your hands, your plan says you must take this fork to the right, you must take this fork to the left, but I do not like that. I like, in the actual business of writing, this feeling that you do not know where you are going. You have in this to know deep principles or feelings that guide you very loosely, but on the actual page you often do not know when a scene is going to end, how it is going to end, or, if you end it in one way, is it going to change the future of the book.

The Rambler, 20 March 1750

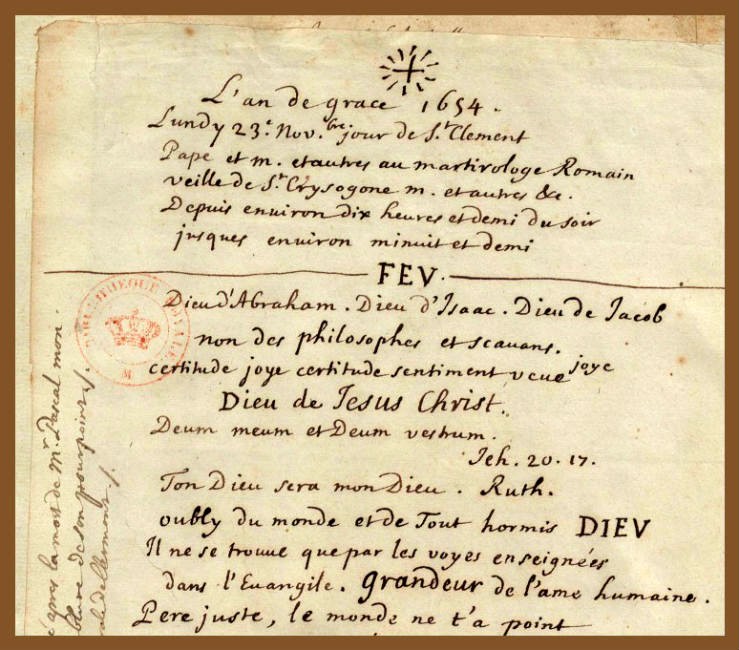

John Fowles: This, you see, is a state of uncertainty, or in terms of the modern physics, indeterminacy. You are never quite sure where the concrete facts and characters that the narrative develops in a book are going to lead. You sometimes have extraordinary mornings and these are the only times in my life when I would, very modestly, claim a genius. That is when ideas flow in on you with such force that very often you cannot write them down, they come so fast, in my case often fragments of dialogue, so fast that you literally cannot write them down. They are very rare, these moments; you pray for them, you can’t create them in any way, they just come; and I have noticed, rather oddly, usually when you are feeling ill and depressed. I do not know whether you know the French religious philosopher Pascal, but Pascal once had a religious experience like this which he could never describe. He just had to say ‘Fire! Fire! Fire!’ He means ‘I was flooded with fire and it was beyond description.’

Blaise Pascal, ‘Feu-Dieu’ (detail from a manuscript of the Pensées), 1654

Source: gallica.bnf.fr | Bibliothèque nationale de France

John Fowles: Very occasionally you have these feelings, almost visions, when you see the whole book. You see all sorts of developments and these moments give you an extraordinary feeling of euphoria, of happiness. Very often later on, when you look at things you have scribbled down frantically, you realize they were nonsense, but usually you get one or two grains, sometimes much more, that are important in your book. This is another distinction between creative writers, poets, and teachers of literature. These are not rational moments, they are much more shamanistic. A shaman, if you remember, in Stone Age and earlier times, was a kind of tribal magician, a tribal priest. Somebody in England at the moment, a writer called Nicholas Humphreys, who is really a zoologist, he studies animal behavior, has recently written a book suggesting that playwrights, poets, novelists can all be associated with the notion of the shaman speaking both to and for the tribe.

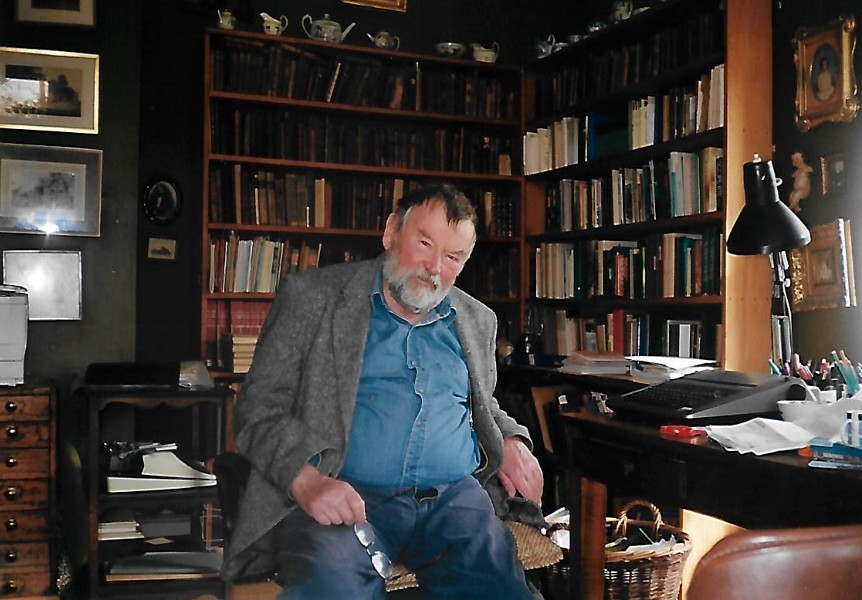

John Fowles at his writing desk in Belmont House, Lyme Regis, 2001 | © Susana Onega

Susana Onega: But if this is so, how do you explain the structural perfection of your novels?

John Fowles: I do not think they are perfect.

Susana Onega: Yes, for instance, the symmetrical embedding of Miranda’s and Clegg’s complementary narrations in The Collector. This cannot happen by chance. Or can it?

John Fowles: Well, perhaps I could answer rather obliquely. There are two stages in writing a novel; there are many stages but there are two broad ones. One is the slightly shamanistic first draft. To say that one is inspired by the muses, as they used to in the eighteenth century, is ridiculous, but this is an area where you have to suppress the teacher, the censor, the critical part of you. Many very clever people linguistically cannot write novels because you have to learn to be two people. One has to be innocent, self-hypnotized, and the other has to be very stern and objective, a kind of professor of himself. I once had a letter from America from an American student who said, ‘Dear Mr. Fowles, I understand you are something of an expert on the fiction of John Fowles.’ Now that amused and interested me, because he obviously thought there must be two different people. One was a kind of unofficial professor of John Fowles and there was this other chap, Mr. Fowles, who he had to write to. But that schizophrenia he had, you need yourself. In that second period or self you have to be very stern, you have to have your blue pencil in hand. The old rule in English is, if you are going through a page of your own prose, the first thing you strike out is what you think is the best sentence in it. There is some sense in that. You very often get so attracted by one single phrase or sentence that you cannot see it is distorting the whole page, or even a chapter. The best solution is often to drop it.

John Fowles in his writing room in Belmont House, 2001 | © Susana Onega

Susana Onega: And the open endings of The Magus and of The French Lieutenant’s Woman aren’t meant to echo the thesis of the novels that the existentialist hero’s quest is the quest itself?

John Fowles: Yes, I was when I was younger, when I was well below half of my present age, we all were in England at that time, and we were on our knees before Camus and Sartre and French existentialism. It was not because we truly understood it but we had a kind of notion, a dream of what it was about. Most of us were victims of it. I quite like that philosophy as a structure in a novel and in a sense I still use it. I would not say now that I am any longer an existentialist in the social sense, the cultural sense. I am really much more interested, in terms of the modern novel, in what fiction is about. I read quite recently most of Italo Calvino, the Italian novelist. That had a considerable effect on me because I felt he was doing what I am trying to do, or what I have tried to do. We writers are of course always slightly jealous and envious of each other and we can stab each other in the back very often, but there are some writers with whom you feel a brotherhood, a fraternal or even sisterly feeling, and Calvino is one of those. I feel great sympathy for Marquez, too, for Borges, the whole South American influence on the current European novel. I think this is for me the major influence on fiction today. It is much more important than that of Beckett or the black novel, the absurdist novel, and also the existentialist novels, Sartre’s theater and so on. I really feel that has passed, that is gone.

JOHN FOWLES: ‘THERE ARE SOME WRITERS WITH WHOM YOU FEEL A BROTHERHOOD’

Gabriel García Márquez

Jorge Luis Borges

Italo Calvino

Susana Onega: In The Collector, The Magus, and The French Lieutenant’s Woman the heroes are invariably left in a ‘frozen present,’ but this is not so in Daniel Martin. Would you say that the happy ending at the end of this novel expresses your jump beyond existentialism?

John Fowles: Well, this is slightly difficult. When I was writing that book I had got very fed up, very displeased with the whole black, absurdist strain in European literature. I do sincerely admire Beckett as a writer, but I suppose Beckett would be the obvious representative of that, Ionesco and so on. I suddenly felt, ‘This novel I am going to end happily,’ and believe me, in our age it is a difficult thing to force yourself to do because the whole drift of modern intellectual European life is that life is hell, it is absurd, it is tragic, there are no happy endings. God knows it has been tragic in a very literal sense, but I somehow thought I would like to end the book happily, just as the Victorian novelists did. The Victorian novelists often tied themselves in knots so that they could have a happy ending, but I felt I would like to try that in a modern British novel. Daniel Martin was very much against Britain because, like all good English writers, I hate many aspects of my country. It seemed right somehow that at least it should end happily when I had said so many things against Britain, and America also, incidentally. It was a very anti-Anglo-Saxon book.

JOHN FOWLES, ‘DANIEL MARTIN’: THREE COVERS

Vintage Classics

Little, Brown & Co.

Back Bay Books

Susana Onega: The hero, Daniel Martin, finally decides to give up script-writing in order to write a novel, after he has succeeded in recovering the love of Jane: are love and creativity the two antidotes against the void?

John Fowles: Well, love, obviously, I should have thought. But creativity, you see, is so unkind. I mean, we can talk about how good democracy enhances many things, but, as I know from the manuscripts I get from other would-be writers, very often they are very handicapped. They have defects of body, or of mind, or of career, they have had to leave school early or whatever it is. Clearly life is cruel, you can only say, ‘I have sympathy for your problem.’ But when it comes to actually judging the novel, I am afraid aesthetic justice is without feeling. You have to say, ‘You can’t write’ or ‘This is badly written’ or ‘This is a cliché.’ Only the Marxists allow clichés, political in their case, to count. Really, I do not know how you deal with this, but there are points when you have to say to people, ‘You can’t write,’ ‘You can’t think,’ or even more important, ‘You can’t imagine,’ because this is a part of the human mind we know very little about: why some people can imagine vividly and why some people can organize that imagination, because creation does need a certain amount of organization. Why some people can do these things and also learn to suppress themselves, because novelists cannot do everything they like.

John Fowles (photo Fowles gave to Susana Onega in 1978) © Susana Onega

John Fowles: You soon learn when you write novels that you are in a prison. I do not deny for a moment I am in a prison when I am writing a book, but it is really like being in a prison that is perhaps six-by-four and you think, ‘How could I make it a little bit larger?,’ perhaps seven-by-five. In other words, you try to create a little bit of freedom, as a prisoner might do in prison circumstances. It can be intolerable when you are writing a novel, when you know you are in this cell, you do not know how to get out of it. Occasionally the escape attempts are what makes the novel, you have got yourself into a kind of fixed code, a fixed theorem, like a geometrical theorem, and it is escaping from that which, I think, often produces remarkable books. Beckett is a good example of trying to get out of the prison we are all in.

JOHN FOWLES: ‘BECKETT IS TRYING TO GET OUT OF THE PRISON WE ARE ALL IN’

Malloy, Malone Dies, The Unamable

I Can’t Go On, I’ll Go On

Watt

Susana Onega: At a given point in the novel, Daniel Martin says: ‘I create, I am. All the rest is dream, though concrete and executed.’ Would you say that Mantissa fictionalizes this statement?

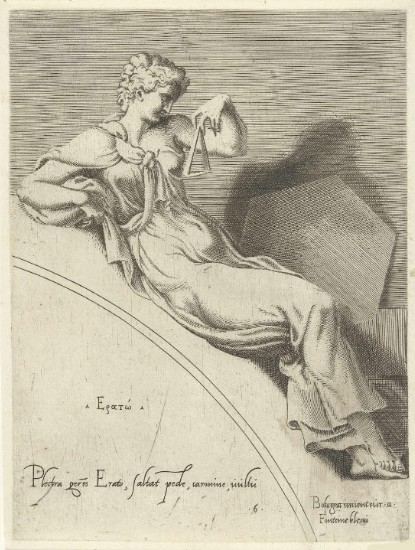

John Fowles: Mantissa was meant to be a joke. It was first going to be published by a Californian private printer—he prints very nice books—but unfortunately I was under contract with large British and American publishers. They turned cruel on me, they said, ‘No, we want this,’ and this nice little Californian publisher was just pushed out by these large publishing houses. In America and Britain it was really taken much too seriously. I like the French idea of the jeu d’ esprit, the lighter book. Something you suffer from in America is this belief that your novels must get larger and larger, longer and longer, more and more important, bigger and bigger in every way. This is blowing up a balloon of hot air. I liked the much more European idea of producing very minor works, something you enjoy doing perhaps, do not spend a great deal of time on and that you will not go to the stake for. You will not be martyred for this book. Mantissa was really meant to be a comment, no more, on the problems of being a writer. I have always had a kind of belief in the muses. Of course there is not a muse of the novel, but I chose Erato, the muse of lyric love poetry in ancient Greece. The notion that she was locked up with a would-be novelist and of course they really hate each other.

Cornelis Bos, Erato, c. 1540-55

John Fowles: You get this kind of problem when you are writing, or at least I get it, because I am a man often very attached to women characters. You just do not know when you are writing dialogue—dialogue is the most difficult part, technically, of any novel—you do not know what they are going to say. I had a famous case in The French Lieutenants Woman. I remember spending a whole day, I needed one sentence that Sarah, the heroine of The French Lieutenant’s Woman, was saying. I tried sentence after sentence, all in the wastepaper basket—and then I realized she was actually saying, inasmuch as a literary character can be real, ‘I don’t say anything at this point.’ She was saying, ‘Your mistake is thinking that dialogue here is necessary. It isn’t necessary,’ and so, that is how it is in the book. She is silent. This relationship you have with main characters is slightly like the dialogue I put in Mantissa: they often seem to be fighting you. They say, ‘I’m not going to walk down this road,’ ‘I’m not going to be burgled,’ whatever it is. In a strange way you have to listen to this. It is a little bit as it is with schoolchildren. Occasionally you have to smack them and say, ‘No! You’re going to do what I tell you to do!’ but, like schoolchildren, occasionally they are telling you something which you had better listen to if you are going to be a good teacher.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Blue Bower, 1865

‘The Blue Bower is the portrait I’ve always imagined inspired Fowles in developing the character of Sarah in The French Lieutenant’s Woman.’ Susana Onega

Susana Onega: What was your real aim in writing Mantissa? How consciously did you have Roland Barthes’s Le plaisir du texte in mind when you were writing it?

John Fowles: I do not think particularly. Dr. Federman yesterday was giving his views on Derrida, Lacan, Barthes… I am exactly like him. I have read quite a lot of them on deconstruction and post-structuralism and all the rest of it. I really do not understand what it is all about. I speak French and I read French quite well but I am afraid most of it is absolutely over my head. A much more scholarly English novelist than myself is Iris Murdoch. I heard her saying only the other day that she regarded it as philosophical nonsense, very largely. Of course it can be very elegantly expressed; especially Roland Barthes I think is a good writer, but I am really very doubtful whether all of that has had much influence on me. In Mantissa I was making fun of it, rather crude fun in places. But I was really expressing the old English view that most of French intellectual theory since the war has been elegant nonsense, attractive nonsense. This is the old business of the practical English never understanding the very rhetorical and clever French. France and England are undoubtedly the two countries in Europe that are furthest apart, although they are so near geographically. The English are much nearer to Spain, Italy, Greece, than England and France will ever be.

JOHN FOWLES, ‘MANTISSA’: THREE COVERS

Little, Brown & Co, 2013

Vintage Classics

Little, Brown & Co, 1997

Susana Onega: Mantissa also brings to mind the deconstructivist theory that there is a unique, all-enveloping written text, a text that is prior to the writer himself. This reduces the role of the writer to a mere ‘scriptor,’ somebody whose only task is to endlessly rewrite this unique and polymorphous text. Would it be right to say that, for all their thematic and stylistic differences, all your novels are simply ‘variations’ of the same novel?

John Fowles: Yes, in one sense. I have often said I have only written about one woman in my life. I mean, I feel that. I do not put it in the novels but I feel when writing that the heroine of one novel is the same woman as the heroine of another novel. They may be different enough in outward characteristics, but they are for me a family, just one woman, basically. Novels, where they come from in your mind, whether they come from some prior unconscious text, I think I would really not like to say. I am not sure. I think also we are touching on an area where it is dangerous for the novelist to be too clever. It is like the old story of your watch being slow and you take it to bits to improve the time—and of course you have finally no watch anymore. By trying to repair it you have lost it. Usually, when I am asked this kind of question, I say I would rather let others judge, as they certainly have in the past. I think this is a job for the critics. They can say that I have certain characteristics of fictional literary behavior and structure and so on. It is not for me to discover that I am a poor conditioned guinea pig or rabbit. It is safer that I keep that at a distance.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, La Ghirlandata, 1865

Susana Onega: Most of your novels seem to have been written with a view to parodying well-worn literary traditions: the ‘confession’ and epistolary technique, in The Collector, for example; the historical romance, in The French Lieutenant’s Woman; or the ‘Examinations and Depositions’ of convicts in A Maggot, which strongly echo the reports made by Daniel Defoe at Newgate. Also, in all your novels there is an explicit reference to certain writers of the past, like Shakespeare, Dickens, Thomas Hardy, or T. S. Eliot, and they even include literal quotations from their works. Why do you do this?

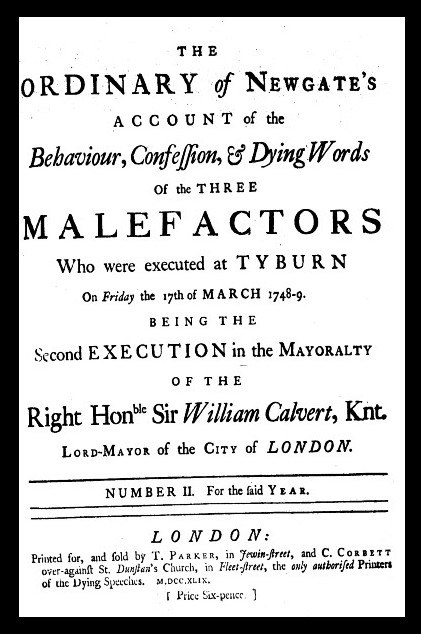

John Fowles: A Maggot is set in the year 1735 and what I did, although the novel itself is fiction, I suddenly thought one day, I have never liked historical novels—why I have written two I am not quite sure, but in general I am much more interested in real history. I would much rather read the historical texts of the period. It occurred to me that in A Maggot it would be nice, because I am imitating eighteenth-century dialogue, to give the reader passages from a well-known magazine of the time called The Gentleman’s Magazine, which all educated people once read. It is also useful because it does give you many authentic facts of the time, and shows how they were printed. English printing was then different. And an impression of the cruelty of the time, because the English then had a barbarous judicial system. If you stole a handkerchief or a spoon then you would probably be hanged in eighteenth-century London—an awful system. I have also always liked the old trial report, where trials are reported in dialogue alone: purely question, answer, question, answer.

The Ordinary of Newgate’s Account…

John Fowles: It did not start with Defoe by any means but I like it, as a novelist, because it sets you an enormous problem. This is another strange thing that novelists have to do to themselves. They have to set themselves difficult situations. If you use this trial technique—question, answer, question, answer—you lose half your arms, half your weapons as a novelist. There is no description of what people are doing—‘She smiled,’ ‘She lit a cigarette’ (not in the eighteenth century!); but anything you can say in an ordinary novel is forbidden by using this technique of the trial report. I like that because it also makes your dialogue much better. You have to express far more through your dialogue than you will in an ordinary conversation. A friend of mine in England is the playwright Harold Pinter, and I think he is the chief exponent of this in English. That is, really cutting down to an incredible degree—that is why he is such a good scriptwriter in films—unnecessary dialogue by making every line of his dialogue really work. Every word of it works, even the silences, in his best plays, work. I really wanted in A Maggot to use that difficult power of pure dialogue a little, although he is a playwright and of course I am a novelist.

JOHN FOWLES: ‘HAROLD PINTER MAKES EVERY LINE OF HIS DIALOGUE REALLY WORK’

The Caretaker | The Dumb Waiter

The Dwarfs

Betrayal

John Fowles: I think that the novel has not caught up with the modern world in the sense of what the novelist can leave out. This is one of the great qualities a novelist must have, knowing what to omit, what to leave out. Many novelists, I am afraid I would accuse the Americans a little bit here, write far too many words. They do not let the reader do any work. You must, you see, get the reader on your side and the way to get people on your side is to give them pleasant work or intriguing, interesting work. Therefore, all that you leave out, all the gaps in your text, are so much fuel for this one-to-one relationship you have with the reader.

JOHN FOWLES, ‘A MAGGOT’: THREE COVERS

John Fowles: I am guilty of this fault myself. I look through old texts I have written and think I ought to have left many things out. You realize you are much too fat, you are much too rich always; you can be sparer. I was reading a little bit of Cervantes, Don Quixote, the other day. Of course that is historical, but I was tempted even then to pick up my blue pencil. There are whole passages where you think, ‘Well, he doesn’t really need that.’ He is a great writer and of course it is historical and enjoyable, but from a strictly modern point of view—the same is true of Defoe in England—it is their prolixity, their unnecessary prolixity, that strikes me personally when you reread them.

John Richard Fox, Untitled 7601, 1976

John Fowles: ‘You can always be sparer…’

Susana Onega: Another recurrent feature in your novels is the existence of two complementary and opposed worlds. One seems to be described in realistic terms, while the other is symbolic and mythical. Invariably the mythical realm is an untrimmed garden, a valley, or a combe. This dichotomy between the city and the green world is a traditional one in literature, but in that delightful little autobiography of yours, The Tree, you describe the green world as something real and at hand, you even use proper names, such as Ware Common or Wistman’s Wood. Should we take it that there are no boundaries, then, between the real and the unreal?

John Fowles: Well, the real in the general sense, the real for me does not lie where we are now, in other words, in cities. It lies for me very much in the countryside and in the wild. They had a phrase in medieval art, the ‘hortus conclusus,’ that is, the garden surrounded by a wall. Very often the Virgin Mary and the Unicorn would be inside this wall and, you see it in medieval painting, everything outside the pretty little walled garden is chaos. I must not get on to ecology and conservation terms. We have ruined the nature of Europe very largely and of course we are busy ruining it in South America and elsewhere now. Man really hates everything outside the ‘hortus conclusus,’ this walled garden. We do not like the wilderness, the chaos.

Upper Rhenish Master, The Little Garden of Paradise, c. 1410-1420

Susana Onega: Women also seem to have a double nature in your novels: Alison’s ‘oxymoron quality, ‘ for example, expressed in the splitting into twins, in The Magus; Sarah’s baffling double nature, alternately innocent and corrupt, like Rebecca Hocknell in A Maggot, etc. Are women as complex and polymorphous as reality, or literature?

John Fowles: I have always found them quite exceptionally difficult to… well, ‘handle’ is rather an ambiguous word in English. Let me say, to have relations with. I am not a ‘feminist’ in the fiercely active political sense it is usually used in England and America nowadays, but I have sympathy for the general ‘anima,’ the feminine spirit, the feminine intelligence, and I think that all male judgments of the way women go about life are so biased that they are virtually worthless. Man is really being a very prejudiced judge of his own case and of course when judging against women. It is counted very bad taste in England now to talk favorably of women’s intuition. The real feminists in England do not like this sentimental talk of female intuition. I am afraid I still have some faith in that. Women cannot, I think, sometimes think as logically or rationally as men can, but thinking logically or rationally often leads you into error. It is by no means certain that the result is any worse in a woman, if you like, muddling her way through to a decision, or feeling her emotional way to a decision, than that of a highly rational man. My impression in Spain is that feminism has not really quite got there to the same extent it has with us. Perhaps that is to come.

John Fowles & Dianne Vipond (right), Belmont House

John Fowles Symposium, Lyme Regis, 10–12 July 1996 | © Susana Onega

Susana Onega: At the end of Mantissa, the mental walls of Martin Green’s hospital room become solid again, trapping the Staff Sister within them. Assuming that she stands for the prototypical literary critic, do we have any reason to hope that there is, after all, a little corner reserved for her within the creative mind, that she is creative in a way?

John Fowles: Well, the whole of this book, Mantissa, takes place in a cell, but of course the cell is the human brain. It all takes place in the brain. It is supposed to be a lunatic asylum and this is where the hero, or anti-hero, of the book is incarcerated. If I could just say, there is an Irishman—we talked a lot about Joyce and Beckett yesterday, but there is a third Irish novelist who I could put very near their level—I do not know if he is known here, his name is Flann O’Brien. He was a journalist, a very funny, humorous journalist also. He had several pseudonyms. Flann O’Brien, I think, was a genius at really absurd humor and that book was behind Mantissa. If I went in for dedicating books to other writers, I would have dedicated it to Flann O’Brien. I suspect his humor is very difficult indeed if you are not Irish. Even the English have a little trouble with it. The Irish are a marvelous literary race. Everyone who is not Irish issues a secret little prayer, ‘I wish I were Irish.’ They really have superb writers. We owe them a great deal in England, Wales, and Scotland. Sorry, now I have forgotten the question.

JOHN FOWLES: ‘FLANN O’BRIEN WAS A GENIUS – THAT BOOK [AT-SWIM-TWO-BIRDS] WAS BEHIND MANTISSA.’

The Poor Mouth

At-Swim-Two-Birds

The Third Policeman

Susana Onega: No, that was a very diplomatic answer. I was asking whether the literary critic has a right to have a corner within the creative mind.

John Fowles: Yes, yes, I think so. If you remember, a part of the muse herself is a critic. Whatever inspires you also usefully criticizes what you are.

A corner of John Fowles’ garden at Belmont House, Lyme Regis, 1996 | © Susana Onega

SUSANA ONEGA: THREE BOOKS

JOHN FOWLES & THE WOMAN WITHIN

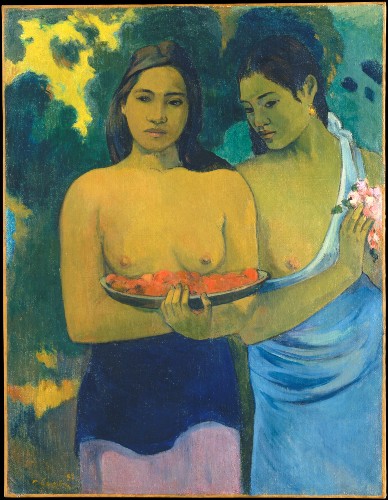

Jung’s Stages of the Anima (As Seen in Art)

1 – Primitive | 2a – Romantic Idealized | 2b –Classical Idealized | 3 – Spiritualized Eros | 4a – Wisdom | 4b – Transcendence

From Carl Gustav Jung, Man and His Symbols (Aldus Books, 1964) pp. 184-85

John Fowles: ‘I have sympathy for the general anima, the feminine spirit, the feminine intelligence … I feel when writing that the heroine of one novel is the same woman as the heroine of another novel. They may be different enough in outward characteristics, but they are for me a family, just one woman, basically.’

Paul Gauguin, Two Tahitian Women, 1899

Piero di Cosimo, Simonetta Vespucci, 1490

Gavin Hamilton, Venus – Helen – Paris, 1785

Jan van Eyck, Lucca Madonna, 1437

Head of Athena, Roman copy (Greek original)

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa, c.1503–06

JOHN FOWLES IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 9

As you feel Pascale’s presence, as you realize how young she is, you feel yourself a child, even as you rush headlong into becoming a woman. You swing your torso around and run your fingers along the spines of the books (novels in German and English), and as you do so, you find it curious that Pascale, a hard-nosed lawyer, should so like reading love stories. Albert Cohen being from Corfu, she decided this was the time to finally read Belle de Seigneur; before that, she’d read G. by a guy called John Berger (a writer you’d grow to love) and The French Lieutenant’s Woman by one called Fowles (who’d also become one of your favourites). Will I ever fall in love? you wonder. Here you’re surrounded by lovers who never tire of showing each other their affection. I’d like to, you think, just to know what it’s like. In the meantime I’ve got Jürgen. He’s my school of sex.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Il Ramoscello, 1865

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 15: Iskra

The next day, after lunch, Iskra gave me a tour of the Botanic Garden. She showed me John Fowles’ favourite orchid, Ophrys tenthredinifera. Yes, she’s a Fowles fan, with a particular affection for Rebecca Lee in A Maggot. (She was pleased to lean the English title: She’d read the book in French, where it’s called La Créature.)

Ophrys tenthredinifera

John Fowles: ‘When I was in a hospital bed just after having had a stroke recently, I was near weeping with self-rage and self-pity, reciting a mantra to myself: tenthredinifera, tenthredinifera, tenthredinifera… That unpronounceable name belongs to one of the most beautiful Ophrys, or bee orchids, of Europe. I had come upon it on a Cretan mountain the previous spring, and I was saying that name like a mantra because I thought I should never climb that remote mountain again.’

John Fowles, interview with James R. Baker in Conversations with John Fowles, Dianne Vipond, ed., (University Press of Mississippi, 1999) 192-93

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 9

̶ Ingrid reads a lot when she’s pregnant. For Lia it was Tolstoy, and for Joost, Dostoevsky.

̶ Maybe I could send her a book?

̶ Of course.

̶ But what?

̶ Whatever you think she’d enjoy.

The Book of Laugher and Forgetting? Nights at the Circus? Letty Fox: Her Luck?

̶ I know: Ada, or Ardor.

̶ Nabokov? She’s read all his novels.

The Hearing Trumpet? The Transit of Venus? Hunt the Slipper?

̶ How about Two Serious Ladies?

̶ What’s that?

̶ Jane Bowles. ‘I dreamed I climbed upon a cliff, my sister’s hand in mine’.

̶ Don’t know it.

̶ Perhaps A Maggot?

̶ Rebecca Lee the Puritan? I think Ingrid would find her strategy of dissent tedious.

̶ Mantissa, then. It’s Fowles at his most Nabokovian.

̶ Yes! She’d love it!

‘A MAGGOT’: REBECCA LEE PERCEIVED AS MYSTIC-HYSTERIC AND AS PURITAN

John Maler Collier, Lilith, 1887

Young Puritan Woman

‘MANTISSA’: MILES GREEN’S IMAGININGS

Georg Scholz, The Lovers, 1920