Each writer has to sing his own song

JOHN UPDIKE ON THE NOVEL: AN INTERVIEW

T.M. McNally and Dean Stover

From ‘An Interview with John Updike’ in James Plath, editor, Conversations with John Updike (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 1994) pages 192-207. Interview conducted by T.M. McNally and Dean Stover in Tempe, Arizona on 24 March 1987. First published in Hayden’s Ferry Review 3 (Spring 1988). Questions and answers not bearing directly on writing have been deleted. Intertitles added by Richard Jonathan.

John Updike, 1970 | Photo: Irving Penn

I. JOHN UPDIKE: EACH WRITER HAS TO SING HIS OWN SONG

In their criticism of your work, critics range from praising the accuracy of your vision to criticizing its triviality. How do you see yourself as a writer and what you are doing?

Well, I didn’t set out to be a social commentator. I write out of deeper, more childish motives than that, which begin with a wish to make a mark on paper—the perhaps irrational belief, which I began to get about the age of twenty, that I had something to say, that I was a witness of things which somehow should be told about and that hadn’t yet been put into print. I’ve led in some ways a sheltered life. I’ve not been wounded in Italy like Hemingway and I’ve never fought marlin at sea. I’m a product of the nearly forty years of Cold War. So naturally I’ve written about domestic, rather peaceable matters, while trying always to elicit the violence and tension that does exist beneath the surface of even the most peaceful-seeming life. That is, I see human life as basically difficult and paradoxical. Just being a thinking animal puts us into a paradoxical and somewhat painful situation: we are a death-foreseeing animal and an animal of mental appetite; we have a Faustian side, always wanting more or something else. Anyway, I’ve never felt myself trivial. It’s up to other people, I suppose, to decide how important or relevant what I deliver is. Each writer has to sing his own song, has to deliver what has struck him as worth telling.

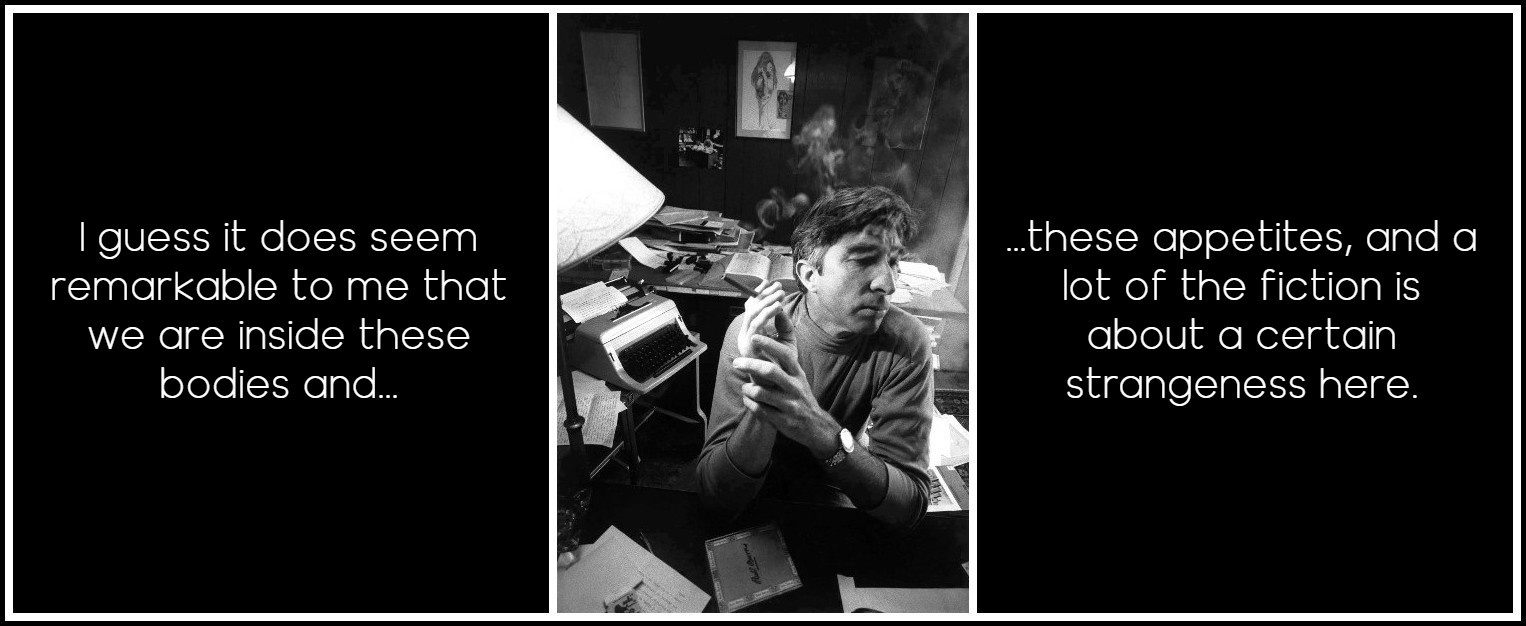

John Updike, 1962 | Photo: Dennis Stock, Magnum

II. JOHN UPDIKE: POET, SHORT STORY WRITER, NOVELIST

What are the differences you see between being a poet, a short story writer, and a novelist?

I’ve explored the genres in that order. I was a poet first. Poetry very much belongs to childish making. I wanted to be a cartoonist, and from quite young on my love of humor and of things clicking and jumping and squeaking and talking led to an appreciation of so-called light verse. I began to write light verse at about the age of fourteen and have remained something of a poet ever since. I’ve tried also to write poetry that isn’t light, or that says what seems to me to be true and interesting about the world. It’s a satisfying thing to write a poem that you think works; it begins and ends rather quickly, often in one sitting. It has a neatness, an inbuilt order that we like. Somehow something deep in us likes looking for order, a completeness that composes well. Short stories are something more, really; something that takes most of us several days if not several weeks to write. I didn’t begin to write stories seriously until I was midway through my college career. If a story goes well, you feel it has a beginning, middle, and end, and in some ways, within its own terms, couldn’t be better: I mean it couldn’t click shut better.

John Updike

I never saw myself as a novelist until my mid-twenties, when it seemed to me that this was the challenge in front of a so-called creative word person in the twentieth century: if you couldn’t attempt a novel, you weren’t really playing in the major leagues. This sounds a little false as I say it. I’m aware of Raymond Carver, Isak Dinesen, and a number of others who have done quite well without ever leaving the short story form; but it seemed to me something that I should try. The novel is a little like living. You don’t know what’s going to happen from day to day. You have the general direction and a sort of general hopefulness that something nice will happen each day, and you sit down to it in that spirit. Novels have a slightly unsettling arbitrariness. I mean they could have gone some other way, very possibly, and be just as good or even better, but they do harden into the shape they take. You do your best by them and try to move on to something else.

What are the determining criteria for what becomes a poem and what becomes a work of fiction?

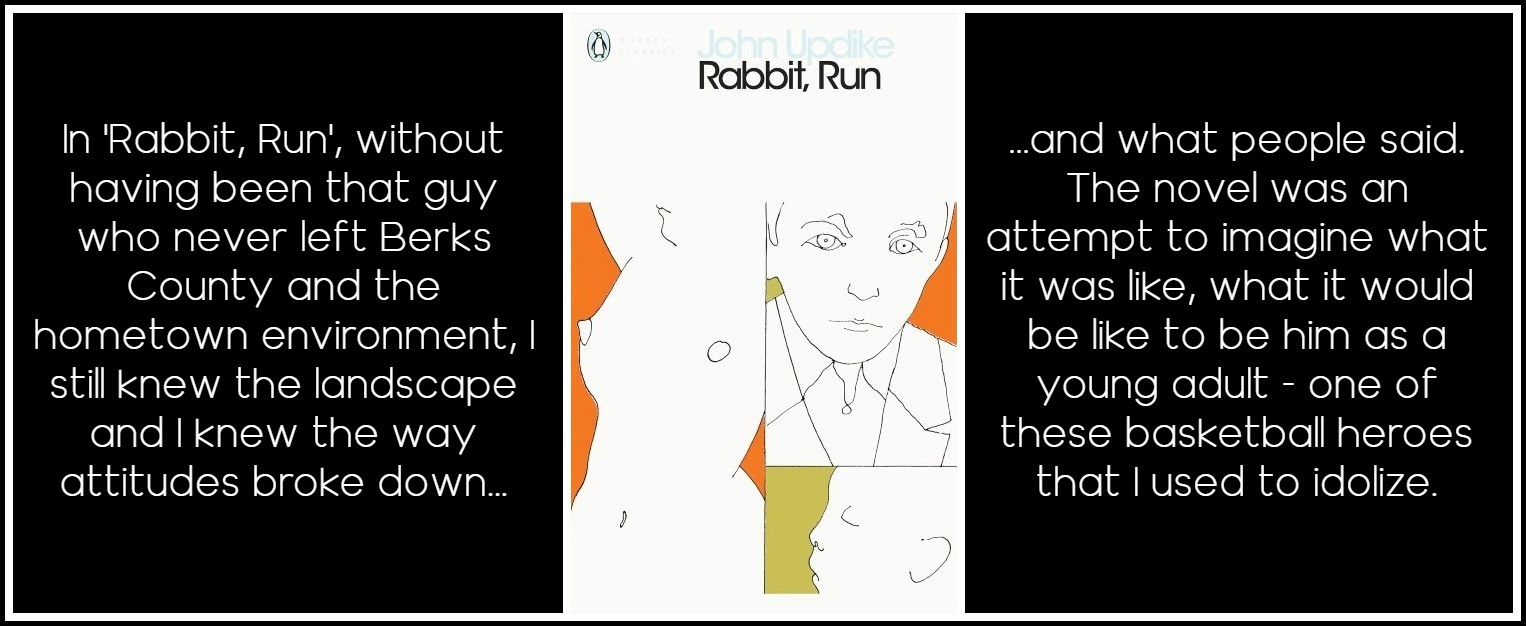

You don’t always know, of course. Some things that begin as poems work out only as short stories, and some things which try to become novels maybe should have been poems. But in general it seems fairly clear that a little tingle or even a very small shiver, but a distinct shiver, should produce a poem if it’s going to produce anything. And in the short stories—I don’t write as many as I used to—the shiver is somewhat broader and often takes a twist or two of manipulation. There has to be some corner you turn in a short story. And in a novel you have a number of corners that have to be turned. A novel begins with a wish to make a statement of a fairly large order about society. It may not seem large when it’s delivered, but it seems large to the writer. For example in Rabbit, Run, one of the impulses was the observation that the small city landscape I had come out of was littered with the unsuccessful later lives of heroic high-school athletes. At least there was something in American society which led a lot of young men to peak at the age of eighteen, and left them really with nowhere to go but down; and this seemed an observation worth somehow embodying.

John Updike, 1962 | Photo: Dennis Stock, Magnum

You also wrote a poem about an ex-high-school athlete.

Yes, I did. In fact I worked that idea all three ways. It also was in one of my early short stories, about an ex-basketball player, called ‘Ace in the Hole.’ So I’ve been lucky with my ex-basketball players. I really wasn’t one, either, although I did, obviously, handle a ball and shoot a lot of baskets. In those days, in Pennsylvania at least, there were an awful lot of baskets up on telephone poles and above people’s garage doors; and so we all were exposed to the glamour of basketball and the beauty of it. I went to a lot of high-school basketball games, too, and still remember the smell and the sense of excitement and the mixture of the sexes and the cheerleaders out on the waxed floor with their sturdy, young legs and short skirts. It was a kind of romance, and it was something of what being an American meant to me: the ability to get turned on by basketball. And Couples, a somewhat later book, had behind it a general sense that all of the old institutions which used to keep people in their houses and in their marriages had broken down, and that what had grown up instead was a kind of intensity of camaraderie, which led often to adultery and to the breakup of these homes. But I wasn’t thinking this was altogether bad; I was saying that a kind of institution had evolved out of the decay of other institutions.

John Updike, Couples, Penguin Modern Classics cover

Other than the obvious reason that most people think of you as a fiction writer, why do you think your poetry for the most part has been ignored?

Well, let’s put aside the possibility that it might deserve ignoring. I think people who decide what is worthwhile poetry are by and large people who have devoted their major efforts to it. And somebody who writes poetry on the side is from the start looked on with suspicion. It’s taken quite a while for example, for Melville’s poetry to emerge from total insignificance to where it now has a standard place in the anthologies. And Hardy, too. Not that I’m Melville, or Hardy, but anybody who writes a lot of prose is viewed as a prose writer and his best self will be searched for there, and maybe found there. That might be a wrong supposition. In truth, the needs of my career, of supporting myself and putting my best self forward most fully, have led me to write more and more prose. And in a way I’ve abandoned the robes of poet. But I’m not ashamed of the poems, of course. In fact, some of them I like quite well. But they were certainly written at odd moments: often on vacation, an airplane trip. I’m not sure this is the way Yeats wrote poetry.

John Updike | Photo: Vineyard Gazette

What is the relationship between imagination and personal experience in your poetry and your fiction?

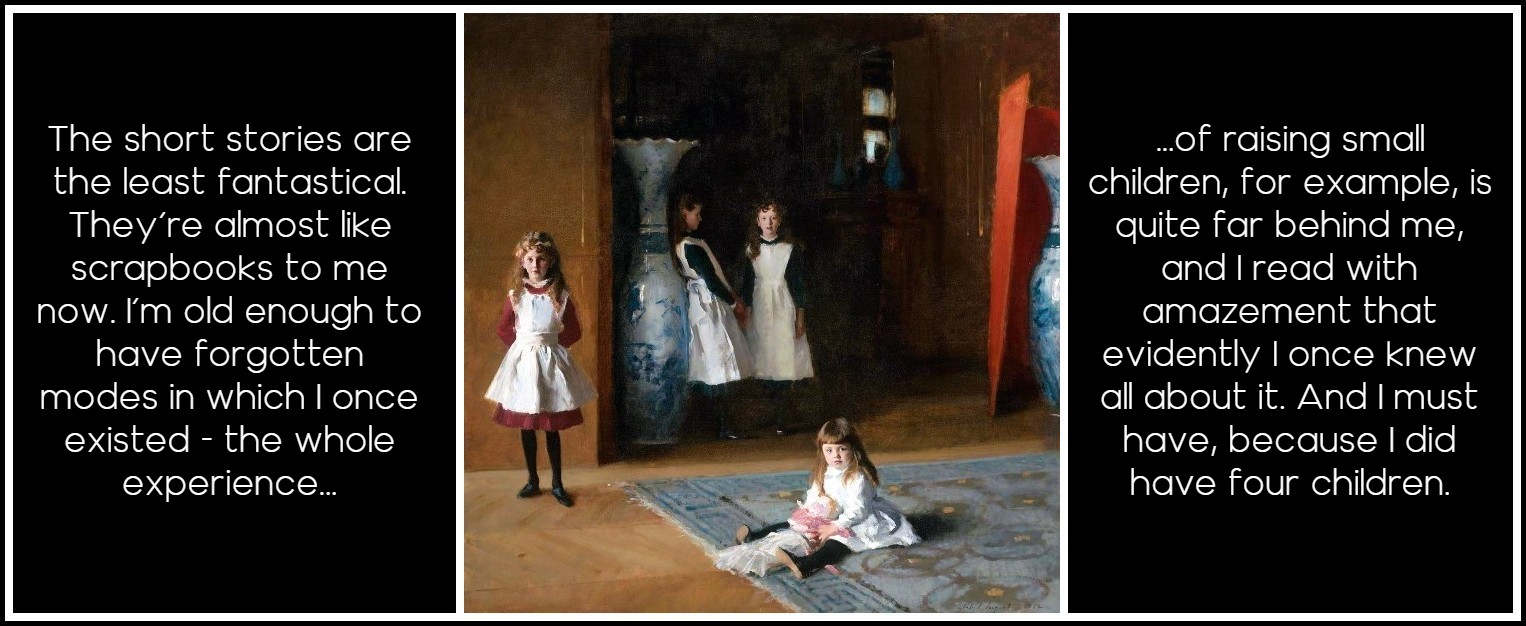

My poetry is often quite impersonal, and may suffer because of it. I rarely put my most ardent and suffering self into it. Maybe my early light verse inhibits me, but the poetry tends to be observational. The short stories are probably the most me, the most autobiographical, because you can have even an uninteresting life and have short stretches of it that can be cut into short stories, with a little twist. Almost always there is an extra twist. I mean you slightly exaggerate, you sometimes combine experiences, you often combine experiences you had with ones you didn’t have. But the short stories, on the whole, are the least fantastical. They’re almost like scrapbooks to me now. I’m old enough to have forgotten modes in which I once existed—the whole experience of raising small children, for example, is quite far behind me, and I read with amazement that evidently I once knew all about it. And I must have, because I did have four children.

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882

The short stories were a kind of running letter to mankind about my inner adventures, my domestic adventures; whereas the novels almost always are in some large part fantastic. There has to be something to make it interesting for me to spend the months or the years with them. There must be a kind of leap for me. My first novel, my first published one, was about old people. I never write totally without some personal hook; I had lived with my grand-parents, so I knew a little bit about old people—how they smelled and talked, their cadences, and enough to feel the poignance that a whole world dies with them. It’s not just that they die, but that they carry with them accents and memories and ways of construing reality that won’t come again. A sort of extinction of the species goes on all the time in the generations. So I felt I had some authority to write a book about old people. In Rabbit, Run, without having been that guy who never left Berks County and the hometown environment, I still knew the landscape and I knew the way attitudes broke down, and what people said, or thought I did. The novel was an attempt to imagine what it was like, what it would be like to be him as a young adult—one of these basketball heroes that I used to idolize. A book like The Coup I wrote in part because I wanted to say something about Africa and about the world, but also I wanted to go to Africa. So, it was sort of my way of taking a trip.

John Updike, Rabbit, Run, Penguin Modern Classics Cover

I think unless we’re going to become slaves to the autobiographical or only write one vast autobiographical book like Proust, or several vast somewhat autobiographical books like Joyce, the American novel must force its imagination outward, try to stretch it as much as possible without losing that urgency of the person writing it, that personal urgency which makes a book alive.

Marcel Proust (Painting: Jacques-Émile Blanche, 1892 | James Joyce (Photo: Berenice Abbott, 1926)

III. JOHN UPDIKE: ON AMERICAN FICTION

How would you define American fiction?

There is certainly a distinctive American vein. Just for a matter of survival and trying to plot your own life, you have to do some thinking about American writing. I majored in English, and when I say English I mean the Metaphysical Poets, the Victorians, and I didn’t really read much American writing in college. So I’ve had to slowly attempt to educate myself in the likes of Hawthorne and Melville, and in fact I came here with a novel by William Dean Howells in my suitcase because in a month I’m supposed to give a lecture on him. He had a very instructive career: an American writer who was pre-eminent in his day, and who has distinctly faded now. The novels are quite readable and part of the fun of it is, firstly, to enjoy them, and secondly, to try to locate what makes them not terribly important now. But he was also trying to cope with this problem—how to be an American writer. And there was no doubt in his mind that one should deal with American materials and get away from the English models: get away from Sir Walter Scott, get away from Dickens, get away from Flaubert and face the American reality. Howells did try, and I think the Howells way still, one hundred years later, has to be our way. We must try to write about ourselves, and write about a continent and a social system which in some ways is still wild. There is something improvised about the American way of life and American art. When you look at what we view as our own classics, you’re struck by how peripheral they are to ordinary experience. I mean, how many of us go on whaling ships? Hemingway also was a great avoider of the American landscape; he did not like to write about what went on inside the American home. The Great American Novel hardly takes place in America at all.

Hawthorne (M.B. Brady, 1862) | Hemingway (Yousuf Karsh, 1957) | Melville (J.O. Eaton, 1870)

That certainly doesn’t seem the case today in fiction, with its trend toward hyper-realism, especially in the short stories.

Yes. Post World War II American writers have tended to stay home at last. I think there was a way of looking at America as late as the twenties: either the writer like Hemingway left and wrote about charming European cafés and bullfights and everything in fact that was not American but appealed to him and entertained him; or the writer like Sinclair Lewis stayed at home and wrote critiques of the awful banality and suffocating hypocrisy and religiosity of American life. So when Lewis faced the music, he faced it from above; he faced it from a sort of superior position, saying this isn’t me, this is what I’m avoiding or looking down on. My feeling is that if America and its manifestations aren’t worthy of being written about now, they never will be. A writer like Bellow certainly can’t be accused of avoiding American reality; that Chicago of his is so alive and so much Chicago it could only be Chicago. Indeed the American Jewish writers have been very willing to embrace their local reality.

Saul Bellow (photo: Richard Meek) | Sinclair Lewis (photo: Port Washington Public Library) | Ernest Hemingway (photo: Ermeni Studios)

My perception of the American writer’s difficulties is that he lacks that sense of an embracing society which enables him to write easily about other people. The English, for all the rigors of their class system, seem to have wonderful imaginative access to each other, so that in Trollope or Henry Green or even the contemporary British fiction—however pale or babbling it might seem—there is a wonderful ease about putting people on paper and making them talk the way they do. Whereas for Americans, we’re locked into our life histories in an unhealthy but interesting way. I guess the flip side of this is that we write more honestly about the little we do write about. There is something about our sense of what a person is that compels us to be more searching. But if you’re going to have an extended career as a writer, I think you do need to try to be empathetic and, in a way, playful.

Henry Green | Anthony Trollope

In contemporary American fiction, what do you think are the differences between a work from the East and a work from the West?

I’m not sure I’ve read enough to really answer the question with any real intelligence, but my impressionistic answer would be that the basic violence that is part of the American reality is more accessible in the West. And it’s even true of California fiction; the West Coast you would think is a fairly settled coast now, but even there—I’m thinking of Nathanael West—lies a scary sense of there being a scorpion under any leaf and of violence breaking out abruptly, and of lives contending against Nature. Fiction of the East is a little more padded, has a little more greenery, a little more illusion of safety in numbers and safety in an established and long history. But the West is closer to the bone of American experience. Here in Arizona the quality of the landscape has to it this feeling of being very thinly covered and temporary, as if it all might be blown away; it’s a subjective sensation. The East has, of course, the Atlantic, which isn’t a very wide ocean, and the East has looked toward Europe often. I think you can kid yourself that you’re a kind of branch of European literature more in the East than you can in the West.

Nathaneal West

IV. JOHN UPDIKE: ON THE NEXT GENERATION OF WRITERS

Recently, a good many younger writers have been published: Jay McInerney, David Leavitt, Amy Hempel. What kind of effect, if any, do you think these younger writers will have in shaping fiction?

Well, I’ve read some and not all, and I just finished reading a long short story by a woman called Deborah Eisenberg who for my taste is one of the best of the youngish writers—but they tend to be a little less young than one thinks. At least they’re in their thirties and not their twenties. I think it’s a lot harder to get a career going now than it was. In my generation there were a number of us who published a lot, by the time we were thirty, for good or ill. I don’t want to harp on the economics of it all, but I do think it’s harder now to take writing seriously. When I went to college, Eliot was firmly on his throne; one had no need to defend writing as something worth doing. Now I think anyone who sets out to write must at some point wonder if it is really not sort of a dying little dead-end. The Gutenbergian age is in its twilight: why should I be doing this for an American audience which basically doesn’t read anymore, just flicks on the tube or whatever else it does—goes out and has a beer?

‘…an American audience which basically doesn’t read anymore…’

Some of these new writers are very good. There’s a strong sense of their coming out of very unsettled upbringings. The presence of step-parents or split families is almost more the rule than the exception now. There’s also a kind of geographical wandering, people who have been a lot of places and haven’t really put down roots anywhere, so that the America you see is an oddly generalized glittery America of parking lots and supermarkets that could be anywhere. This is the way they see it and this is where their lives have led them, so you can’t quarrel with it. But it does make it harder for them to be warm. You think of the warmth that Faulkner’s able to generate from a moldering old corner of the South, but in contemporary fiction there’s a funny, shallow feeling of ‘So what?’ And the ‘So what’ extends even to ‘So what if my boyfriend and I broke up? So what if it turns out I’m gay and not straight? So what if I lose a job?’ These things seem to happen almost as if on a TV screen. You don’t feel they’re so much happening to the people as happening outside of them.

Photo: Curated Lifestyle – Unsplash

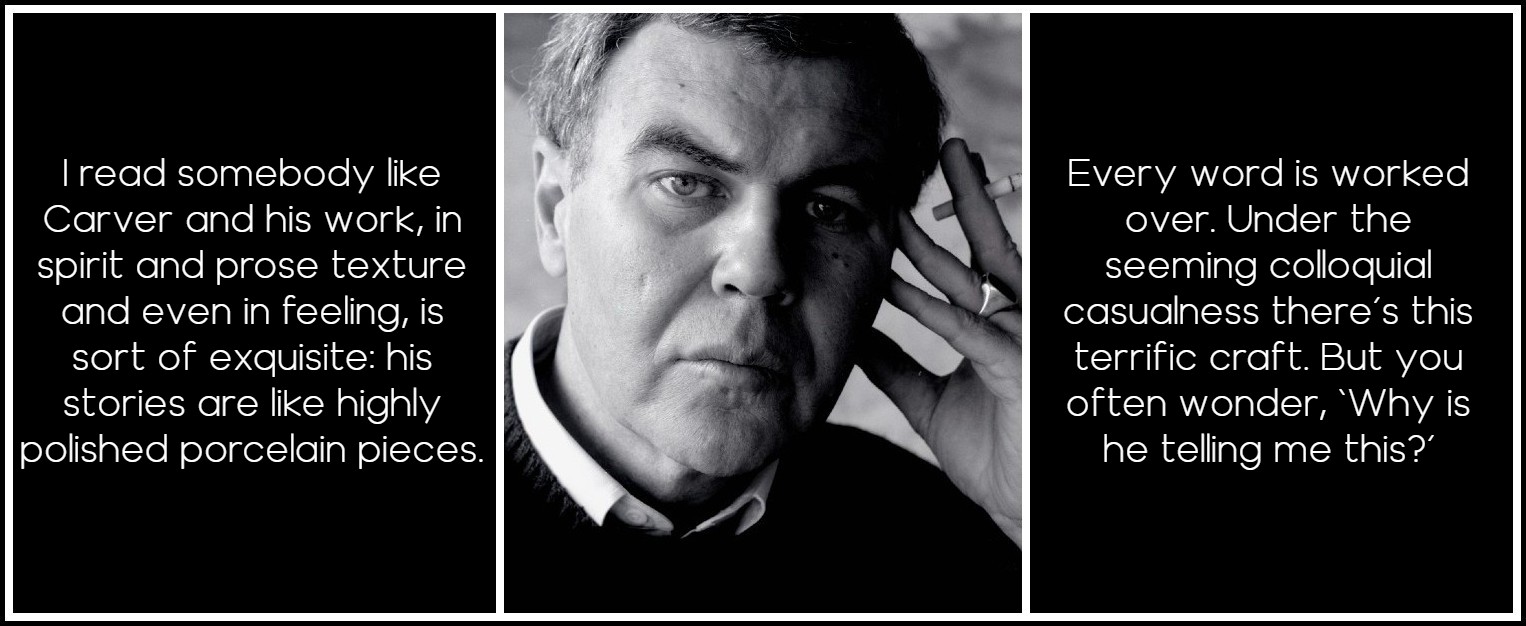

So the traditional warmth and empathy and caring that leads us to enter fiction is not easy to generate. I read somebody like Carver—who of course is no young writer, he’s about my age, but in a way he belongs much more to the younger writers now than I do—and his work, in spirit and prose texture and even in feeling, is sort of exquisite: his stories are like highly polished porcelain pieces. Every word is worked over. Under the seeming colloquial casualness there’s this terrific craft. But you often wonder, ‘Why is he telling me this?’ As for Jay McInerney, I’ve read only Bright Lights, Big City, which seemed to me fine, as long as you were on this sort of stoned, disco-to-disco level—a life going in funny directions and no direction. When at the end he tried to pump a little warmth into it, it felt phony in a strange way. That is, the very wish to make you care about it made you care less.

Raymond Carver, 1984 | Photo: Bob Adelman

Frederick Barthelme is a writer I read because he appears in The New Yorker and because he seems to me the master of a kind of glazed hardness: his fondness for describing the way the restaurant tables look; and the way the women are dressed; and the wonderful scary way the hero can never make a connection with these women, all of whom seem to be pretty much on the make. These women are still alive in the old-fashioned way, throwing themselves at this man, this narrator who’s scarcely alive and can’t often respond sexually, and certainly not emotionally. But the young writers are each different. You can’t generalize. Although many of them seem to share a fear of saying too much—of having too many adjectives and volunteering too much information and a fear of trying to steer you emotionally until there’s something faintly repellent about the surface of the story. Obviously these young writers are interesting, and I applaud them for having been led into this venture of writing when so much would seem to mitigate against it.

FREDERICK BARTHELME: Second Marriage | The Great Pyramids | Moon Deluxe

V. JOHN UPDIKE: SEX IN FICTION

Your work explores taboo, especially sexual taboo. What is the place of taboo in modern fiction?

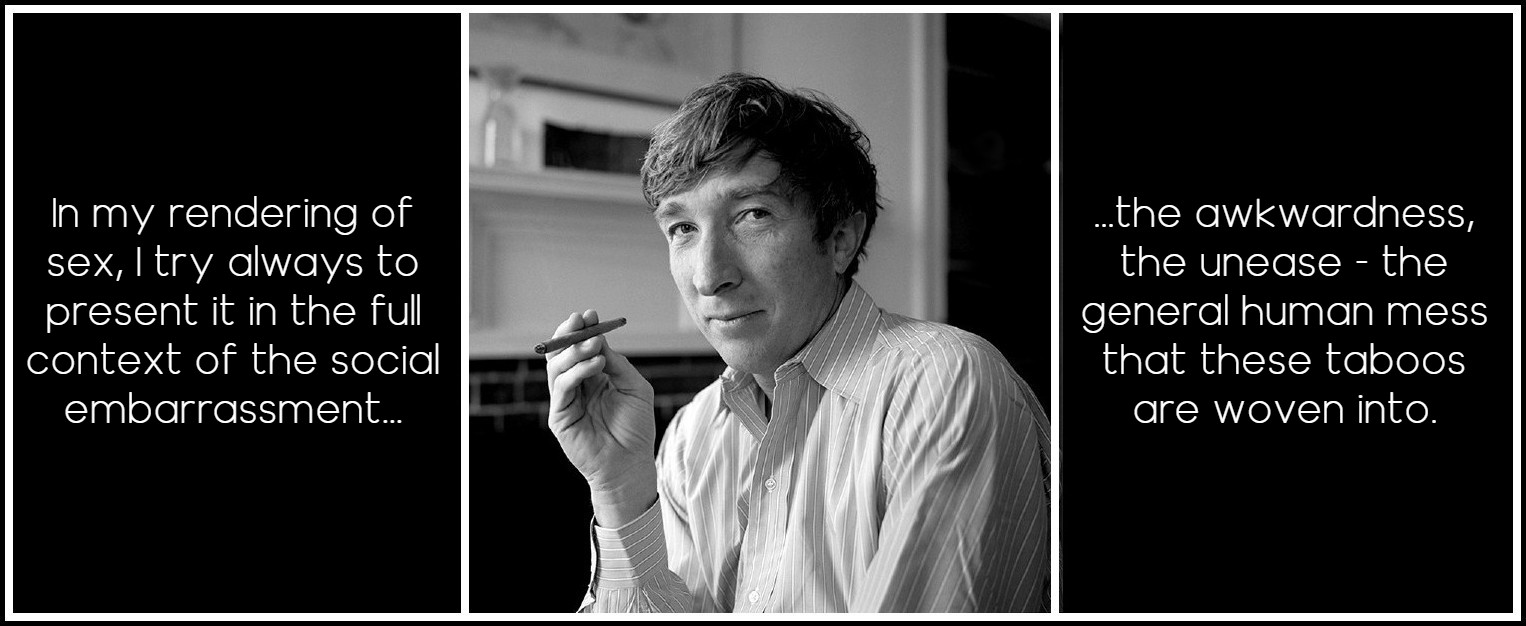

Modern fiction, at least from Cervantes on, to some extent is trying to bring out the intimate life of the individual person, and part of that is his sexual life. And so I think it natural that fiction has again and again seemed to skate near taboos. There isn’t much left in this day and age of triple-X films and triple-X books, and after respectable fiction like Ulysses and Lolita and Lady Chatterley’s Lover. My own criterion is that we describe whatever we feel exists, but it must exist: it must be somehow mixed in also with the other parts of being human. In my rendering of sex, I try always to present it in the full context of the social embarrassment, the awkwardness, the unease, the nimbly stomach—the general human mess that these taboos are woven into. Freud said some very nice things about taboos, of course; he said that if the old ones break down, people have to construct new ones just to make sex interesting.

John Updike, 1971 | Photo: Baron Wolman

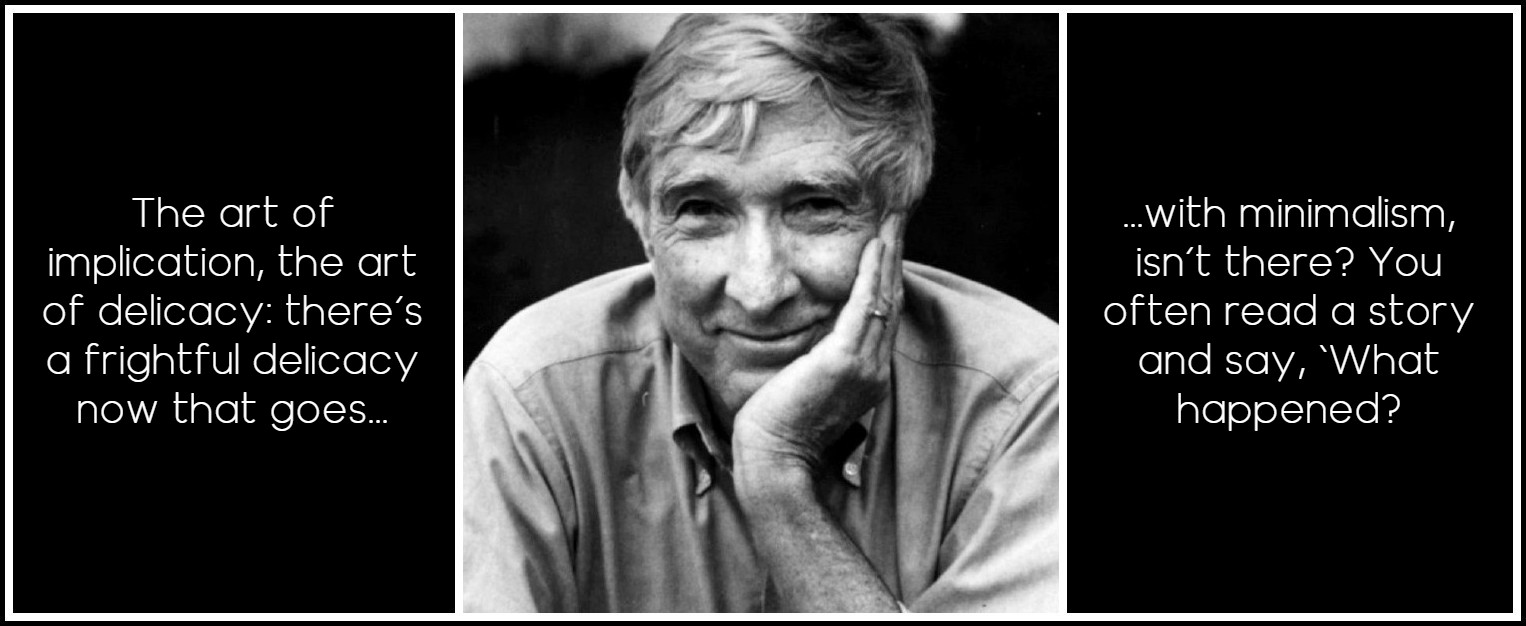

For every movement, there’s a counter movement. There is, of course, a very strong Puritanical reaction in this country that would put us back into Victorian clothes and Victorian mores; but also within fiction itself. Each fiction writer has to do something he feels hasn’t been done before. And certainly I don’t see much specific sex in the younger writers. My generation, and the one a generation before, was keen on breaking sexual taboos in print, but I don’t think it is viewed as an artistic frontier now. I don’t know what’s going on in writing courses, but what I feel in the younger writers is their interest in seeing how much they can imply and not say, on every level. The art of implication, the art of delicacy: there’s a frightful delicacy now that goes with minimalism, isn’t there? You often read a story and say, ‘What happened?’ That seems to be what interests the younger people who I read, instead of spelling it out or shocking grandma or any of that stuff that used to interest me—maybe does still interest me, since it’s hard for an old dog to learn really new tricks.

John Updike, 1974 | Photo: Ara Güler

VI. JOHN UPDIKE: ON HIS CONTEMPORARIES

Where do you think the strongest poetry and fiction are being written?

On the theory that enough butter gets in the middle of the sandwich anyway, I’ve looked abroad for inspiration, away from America and American writing. I’ve read people like Calvino and Grass and some English writers whom I’ve really admired like Murdoch and Spark; and the Latin Americans I’ve gotten into, not as heavily as many have gotten into them, but I have read quite a lot of Garcia Marquez—and Mario Vargas Llosa and Machado de Assis. I think Latin Americans are in some way where Americans were in the nineteenth century. They really have a whole continent to say; suddenly they’ve found their voice; they’re excited about being themselves and their continent and their history. And that’s a great weapon in the armory of an artist, to be excited by your subject.

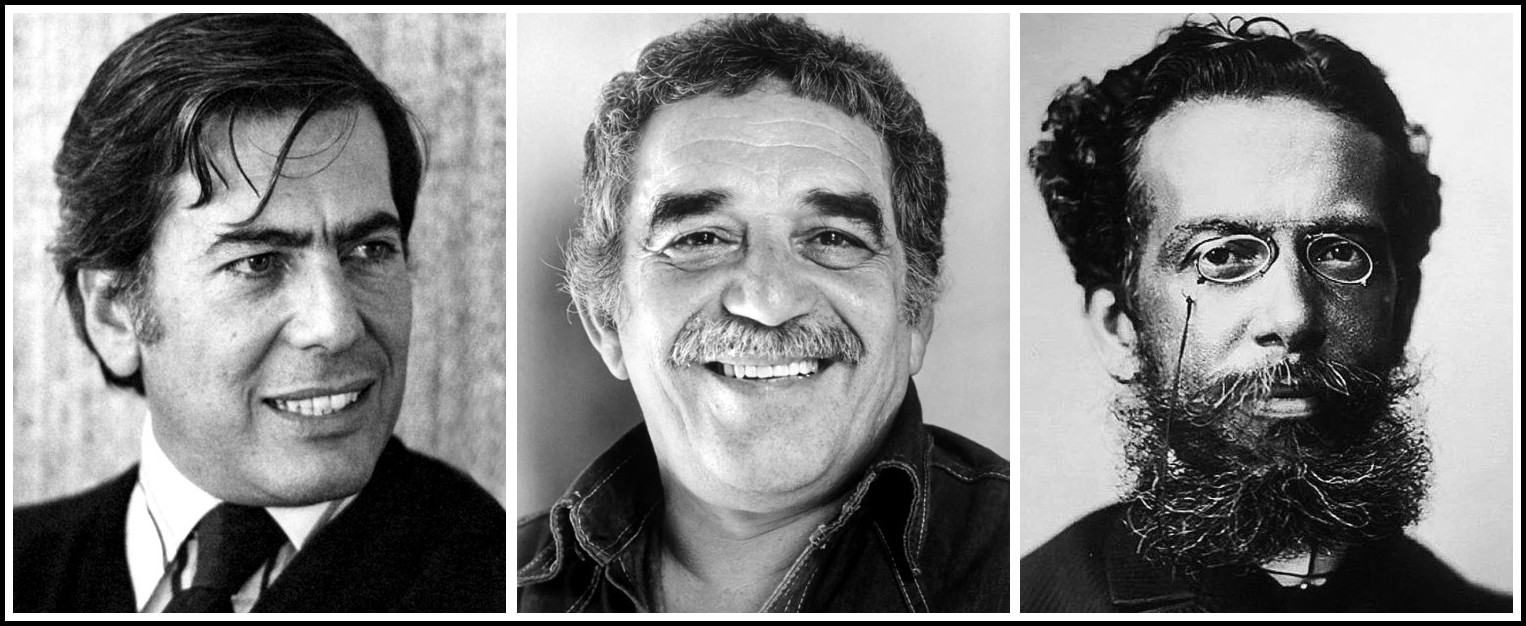

Mario Vargas Llosa | Gabriel García Márquez | Machado de Assis

I was chastised when I was in Paris last April, scolded for always saying I wasn’t aware of anything interesting coming out of France, but it is true I’m not aware of much. I think criticism in France has become almost the all-devouring art. Roland Barthes was, in his way, a jolly life-enhancing figure, but deconstruction doesn’t have much in it to encourage a creative writer, because it says that everything you say is not that at all anyway. As for Germany, I think it is a country—a language, really—that has a lot to work out still, and there is good stuff coming out of there. Perfume, for example, by Patrick Süskind.

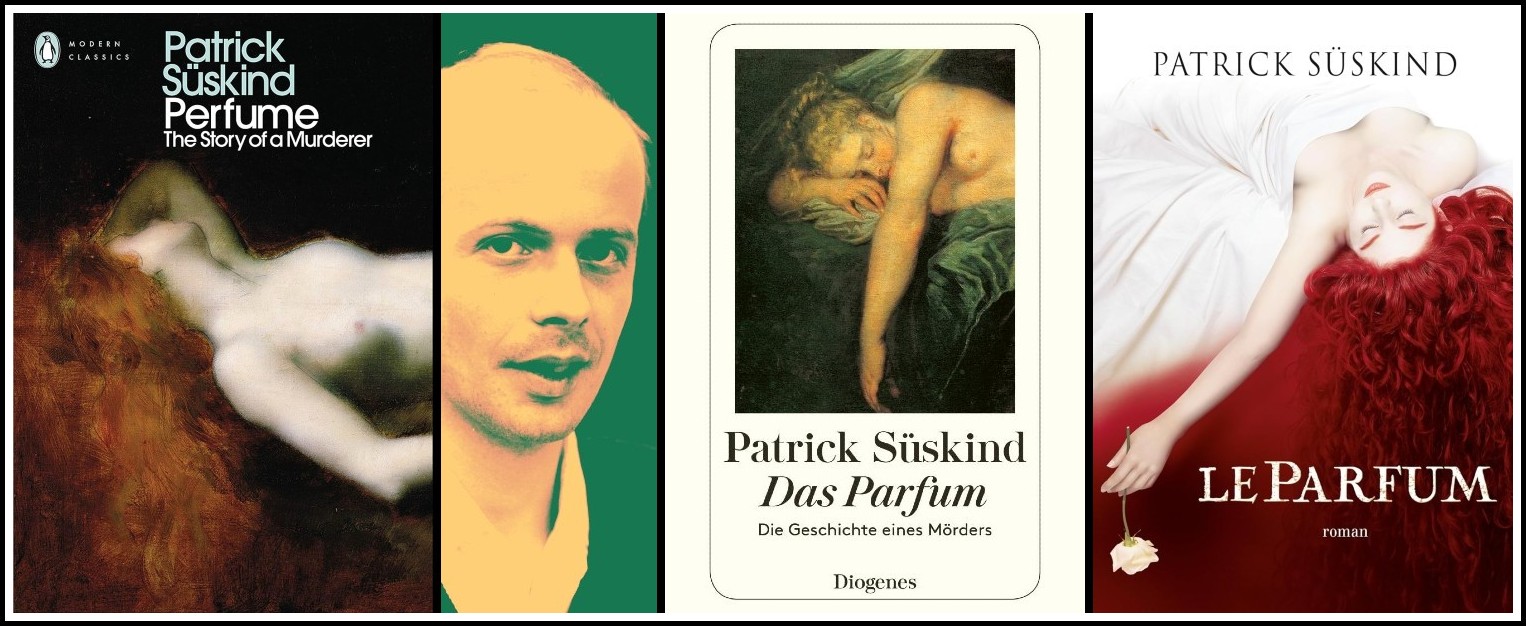

Patrick Süskind – Perfume: The Story of a Murderer

The formal problems that were of interest to me when I was young were exemplified by Robbe-Grillet and Donald Barthelme, who were trying to reinvent what fiction could do, to make it look different. But that has kind of run its course now. There were some wonderful formal experiments made, but I feel it’s rather exhausted. You can still write a book with some trickiness in it, but you can no longer write a book just because it’s going to be tricky. We’re post-experimental in a way.

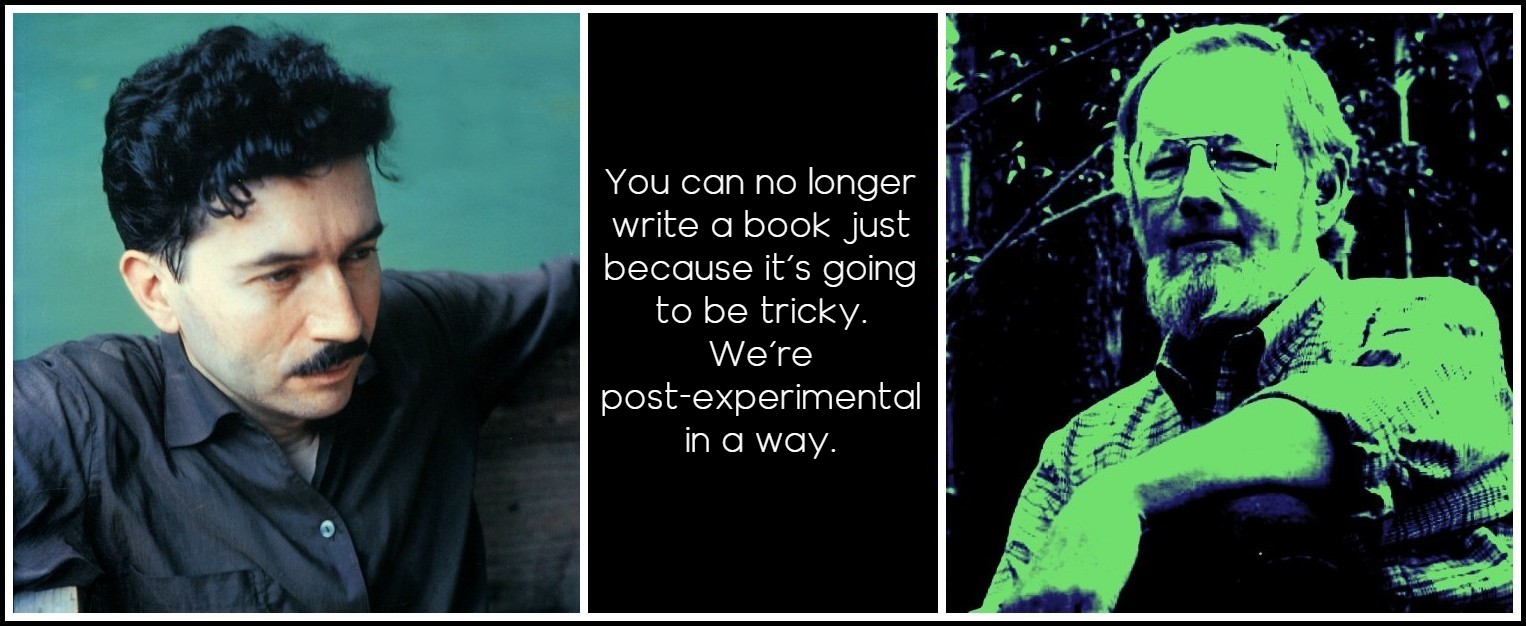

Alain Robbe-Grillet | Donald Barthelme

The American writers who still excite me most are people like Bellow and Roth and Cheever and Salinger and Malamud—writers who meant a lot to me when I was young. I suppose we’re all in thrall to people who got their thumbs on us while the clay was still fairly moist. The older you get the harder it is to make a dent, so that although I can certainly admire the younger writers, I’m less apt to want to steal from them than I was from Bellow. I mean, you read a page of Bellow at his best and you think, ‘My God, nobody’s ever written like this. Nobody’s ever put those things on paper before.’ So, I guess I’m still reading fiction in hope of finding things there, news about life, news about what it’s like to be alive in a certain place.

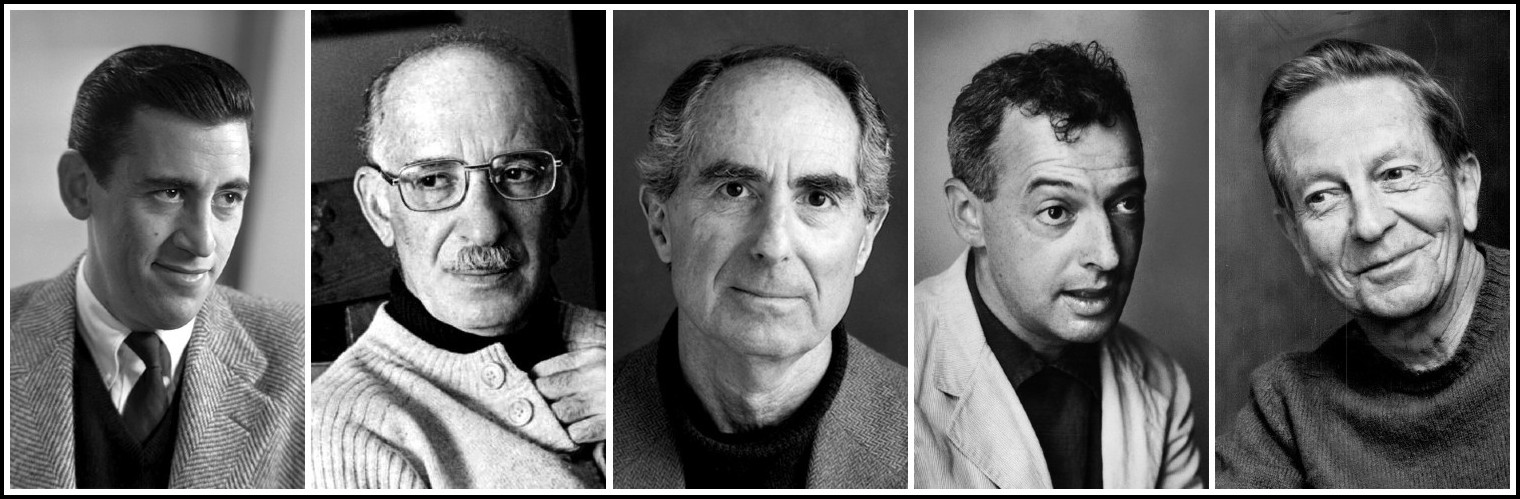

J.D. Salinger | Bernard Malamud | Philip Roth | Saul Bellow | John Cheever

VII. JOHN UPDIKE: INFINITE SPIRIT, FINITE BODY

There seems to be a debate in your poetry as well as your fiction between the infinite nature of the spirit and the finite nature of the body. How has this debate changed over the years?

It’s a large way to look at it, and we may be approaching an area here where psychoanalysis and not self-analysis is what’s called for. I don’t quite know why and I don’t know why my poetry has taken the exact form it has. Religiously, I was raised as a Lutheran in a county where Lutheranism was taken for granted; just like anything that’s taken for granted, it didn’t seem very important. But it was worked into my system, so that when I left this world I found it was a part of me that I didn’t want to let go of, couldn’t let go of—I was scared without it, frankly. So in some way I’ve remained a religious person off and on, kind of a lackadaisical Christian, but a Christian nevertheless, and certainly it’s figured in the writing. You wonder in a way—why write about people if they’re just bundles of neurons and cartilage and going to live and die like a set of chickens in the yard? I guess it does seem remarkable to me that we are inside these bodies and these appetites, and a lot of the fiction is about a certain strangeness here. My early novels were framed in terms of animals; that is, Rabbit being a kind of impulsive darting creature and the Centaur being a horse person. The Centaur is very much about this being half spirit and half body, or being caught in an incongruous physical frame. Not just incongruous, but of course painful: death is painful, toothaches are painful, love is painful; so much that our bodies ask of us is painful.

John Updike, 1974 | Photo: Ara Güler

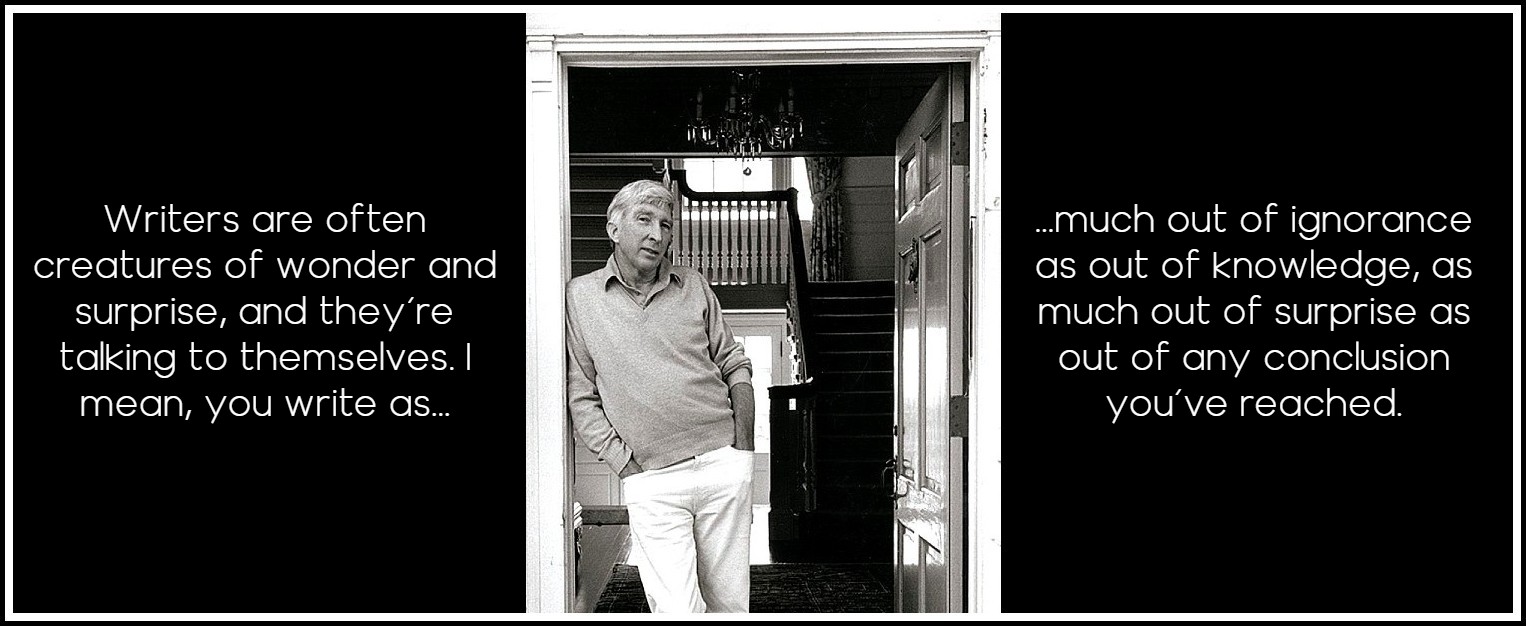

I don’t know if I’ve changed an awful lot. Or enough. I should change. We all should change. One thing that’s given me courage in writing has been this belief that the truth, what is actual, must be faced and is somehow holy. That is, what exists is holy and God knows what exists; He can’t be shocked, and He can’t be surprised. There is some act of virtue in trying to get things down exactly the way they are: how people talk, how they act, how they smell. So I have felt empowered in some way to be as much of a realist as I could be, to really describe life as I see it. I’m not ignorant scientifically, but there is something supernaturalist in the way people have always written, from the Bible on. We are used to dualism in our fiction. We feel like spirits to ourselves as well as bodies. So, yes, it is hard for me to write, I suppose, without some sense of that dualism. It makes life interesting. We seem to be dual, we seem to be double in some odd way. We are witnesses to ourselves, too. We witness our intimate and helpless acts, except when we sleep. I really never set out to be a Christian writer or theological writer. I’m just trying to announce with a sense of wonder the surprise that I’m here at all. It has always struck me as slightly odd that I’m me instead of you. There’s a tendency to view writers as founts of wisdom who know something and who are writing away trying to deliver some instructions; but often they are creatures of wonder and surprise, and they’re talking to themselves. I mean, you write as much out of ignorance as out of knowledge, as much out of surprise as out of any conclusion you’ve reached.

John Updike, 1987 | Photo: Nancy Crampton

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments