Looking into the Abyss: The Poetics of Manet’s ‘Bar’

MANET: A BAR AT THE FOLIES-BERGÈRE – ANALYSIS – PART 2

Jack Flam

Jack Flam, Emeritus Faculty, is Distinguished Professor of 19th- and 20th-Century European and American Art, City University of New York Graduate Center.

Condensed from Jack Flam, ‘Looking into the Abyss: The Poetics of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère’

in Twelve Views of Manet’s ‘Bar’, ed. Bradford Collins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996) pages 168-173

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY: READ PART 1 FIRST

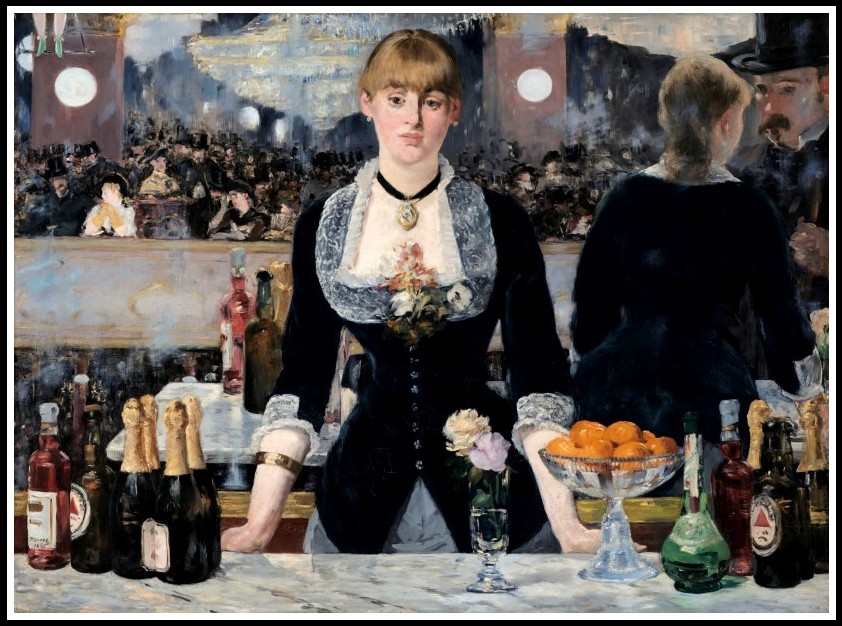

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82

III. STRUCTURE AND ICONOGRAPHY

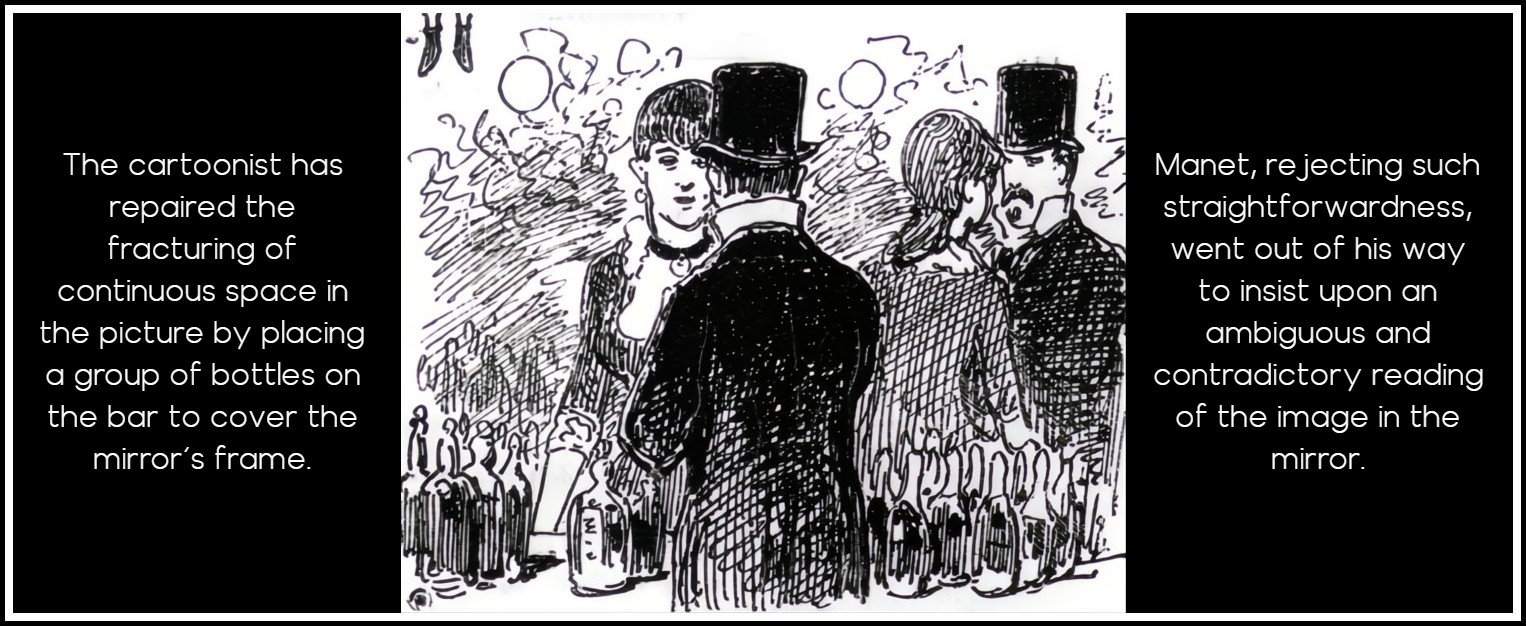

In Stop’s cartoon satirizing A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, the cartoonist has automatically, and without mentioning it in the caption, repaired the fracturing of continuous space in the picture by placing a group of bottles on the bar to cover the mirror’s frame. If Manet had also done this, he would have encouraged (or at least permitted) the argument that perhaps the right side of the mirror is not parallel to the picture plane, and it would be much less clear that the image in the mirror represents a physical impossibility. Instead, Manet went out of his way to insist upon an ambiguous and contradictory reading of the image in the mirror.

Stop, A Merchant of Consolation at the Folies-Bergère | Le Journal Amusant, 27 May 1882

The Bar offers the most striking instance in Manet’s art of the primacy of mental vision over actual sight. The spatial ambiguity in the construction of the painting is more extreme than anything in Manet’s earlier painting; more extreme, for example, than that in the Execution of Maximilian or in The Railway (Gare Saint-Lazare), both marked by a severe compression and contraction of space. Although the spatial ambiguities in those paintings enhance the ‘modernity’ of their realism, the spatial contradiction in the Bar calls into question the very notion of realism.

Manet, The Railway (Gare Saint-Lazare), 1873 | Manet, The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, 1868-69

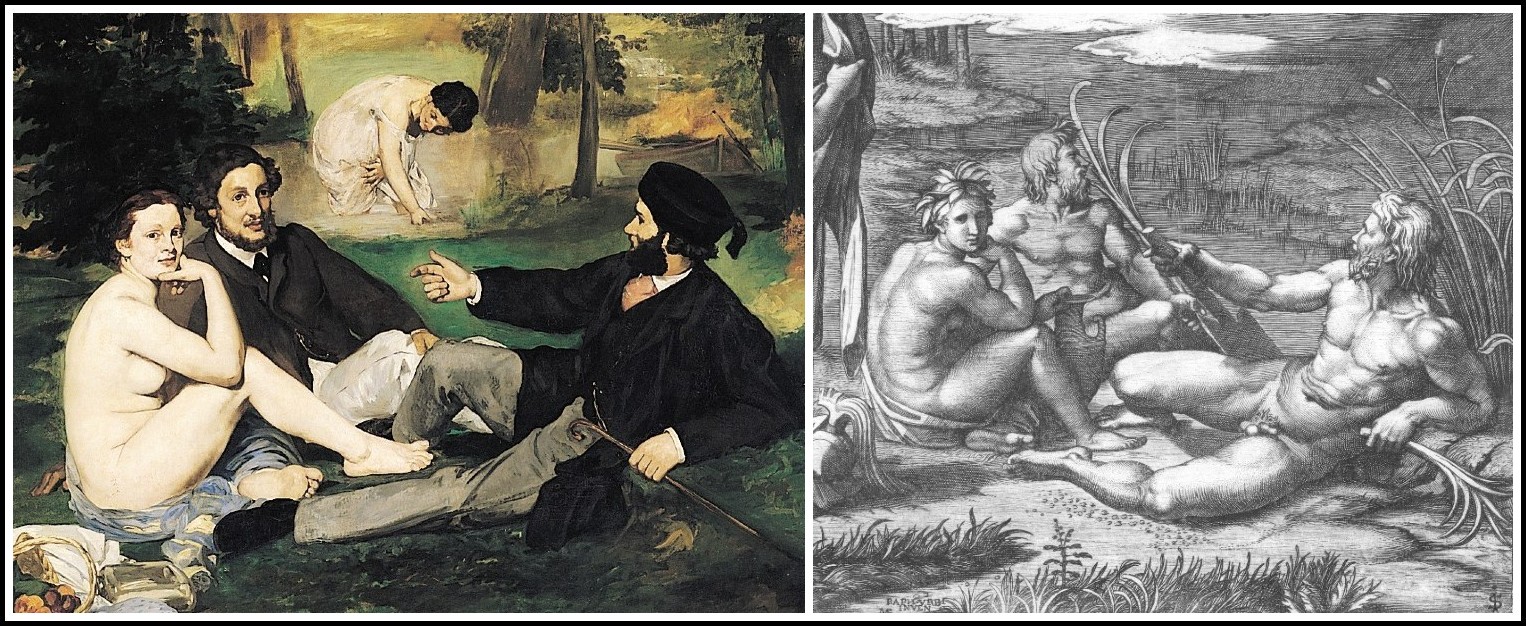

In fact, one of the most striking aspects of the Bar is the way in which it embodies the transformation of Manet’s attitude toward realism, which began to change drastically after around 1870. In most of his major paintings of the 1860s, Manet had found a way to go beyond representing merely the surface of everyday life by filling his pictures with allusions to earlier art, as in the Déjeuner sur l’herbe…

Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863 (detail) | Raimondi after Raphael, The Judgment of Paris, ca. 1510–20 (detail)

…and Olympia.

Manet, Olympia, 1863 | Titian, Venus of Urbino, 1538

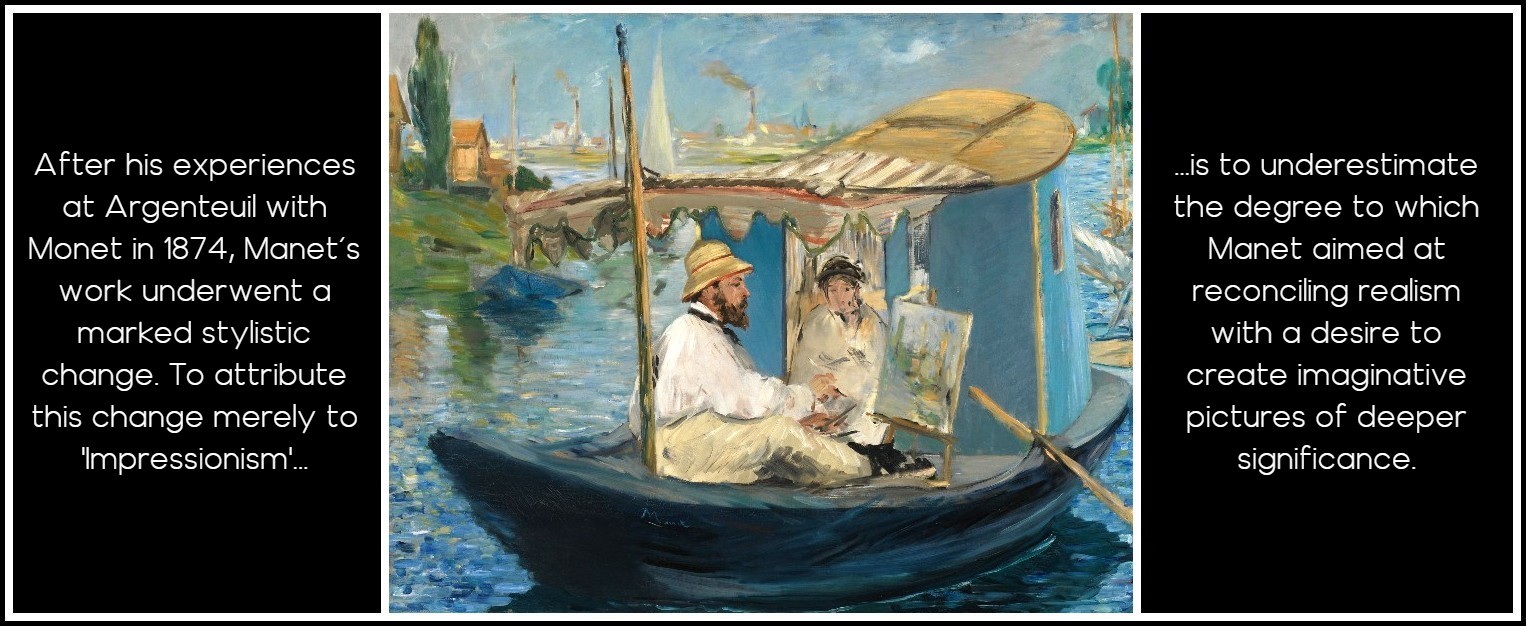

After around 1870, these obvious allusions virtually disappear from Manet’s art. This shift in his ongoing dialogue with the history of painting coincided with his growing friendship with Monet, and is usually called Manet’s ‘Impressionist’ phase. But something else may actually be involved here. Granted, especially after his experiences at Argenteuil with Monet and Renoir during the summer of 1874, Manet’s work underwent a marked stylistic change. To attribute these changes merely to ‘Impressionism’ as an abstract force, however, is to assume something like a disavowal of his earlier work and to underestimate the degree to which so much of Manet’s enterprise had been involved with reconciling the realism associated with everyday life—il faut être de son temps—with a desire to create imaginative pictures that had a deeper significance.

Manet, Claude Monet Painting in His Studio Boat, 1874

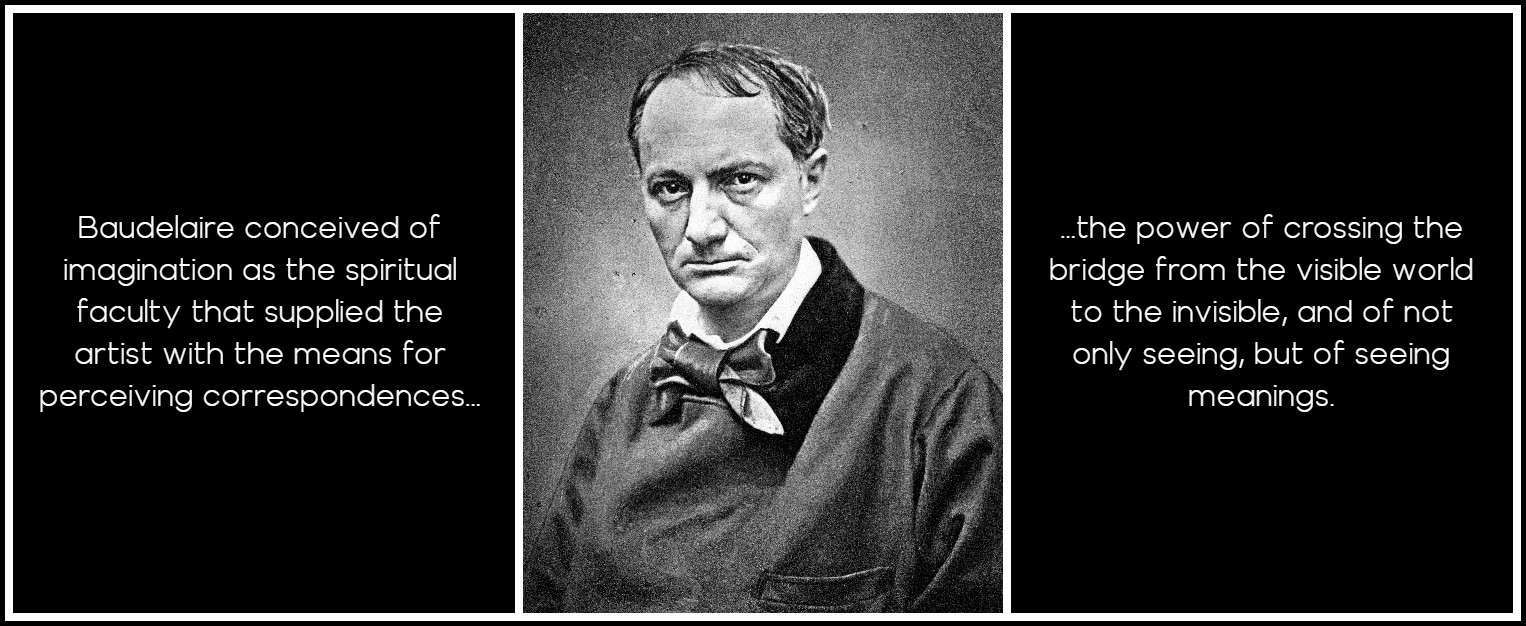

On the evidence of his paintings, Manet’s attitude toward realism seems to have been quite similar to Baudelaire’s. In his ‘Salon of 1859,’ Baudelaire had discussed imagination as the primary faculty of the artist, which combined ‘both analysis and synthesis’ and allowed him to rise above the mere imitation of nature. Moreover, as Margaret Gilmore has noted, Baudelaire conceived of imagination as the spiritual faculty that supplied the artist with the means for perceiving correspondences, the ‘power of crossing the bridge from the visible world to the invisible,’ and of ‘not only seeing, but of seeing meanings.’ The imaginative use of the mirror is one of several aspects of A Bar at the Folies-Bergère in which a bridge is created between imagination and reality—in which the visible world is explored in a realistic way, but without being limited merely to surface realism.

Charles Baudelaire

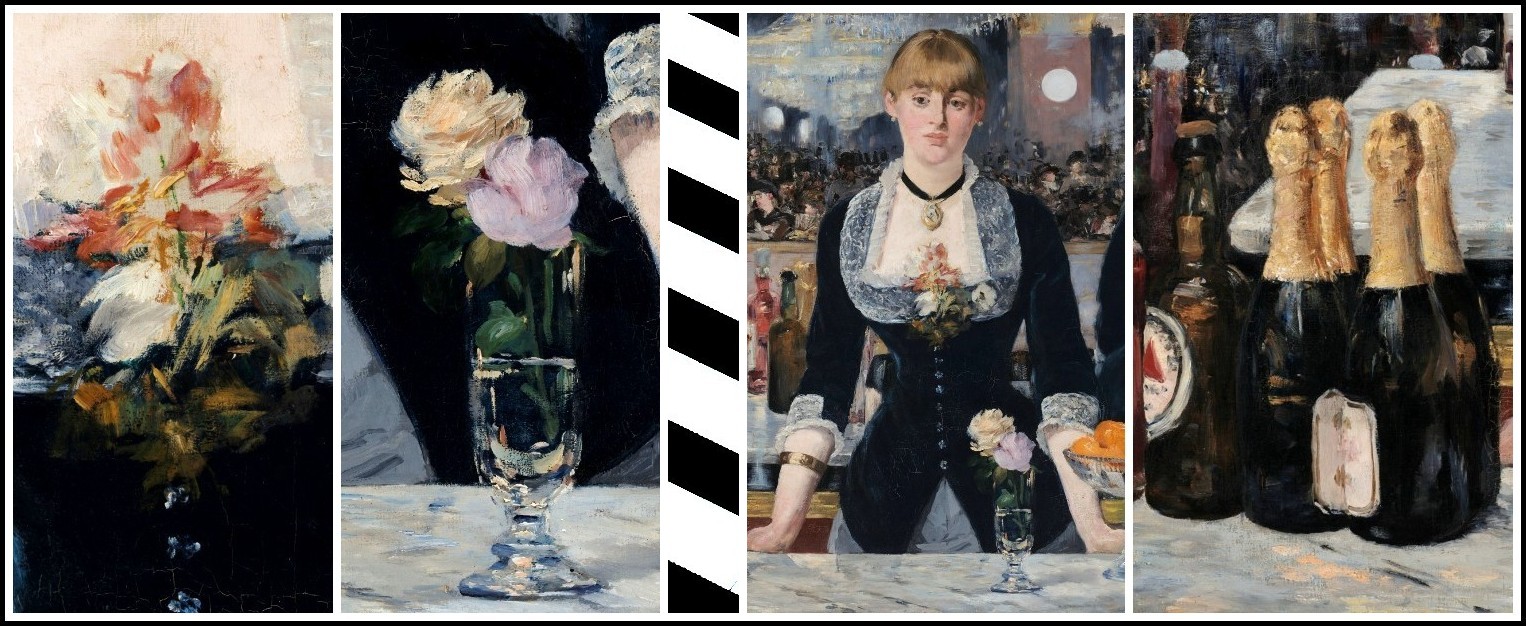

As we have seen, the essence of the Bar develops around a series of related polarities. One of the most crucial is that between the center and the margins, which is echoed in the polarity between foreground and background, real and reflected. Whereas in most of Manet’s paintings of cabaret scenes and public life during the 1870s the compositions tend to be asymmetrical and frequently employ open centers, in the Bar the woman occupies the exact center of the painting and is conceived as a nearly symmetrical, triangular form. It is hard to imagine a compositional motif that is more hieratic or that could supply a greater sense of stability. Around her, however, everything is in flux. She is surrounded by glitter and reflections and she herself is the only undeniably real person in the picture. Everyone else is seen only through the untrustworthy mirror. The woman is at once separated from and intricately related to her immediate environment, with which her body is engaged in an elaborate network of visual rhymes and echoes. Principal among these is the audacious way that her torso in its tight-fitting jacket rhymes with the champagne bottles on the counter next to her, and the way the flowers on her bosom echo those on the bar. She is, among other things, an object of desire among other objects of desire, a commodity among other commodities. But it seems to me that to deduce from this that she is merely, or even clearly, a prostitute—as has been insisted upon in recent writings about the painting—is to ignore the extraordinary, and systematic, complexity of the painting as a whole. The world of the picture is full of disjunctions. And among them is this one: that if the woman is a sign of desire, desire itself is fractured and ambiguous.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (details)

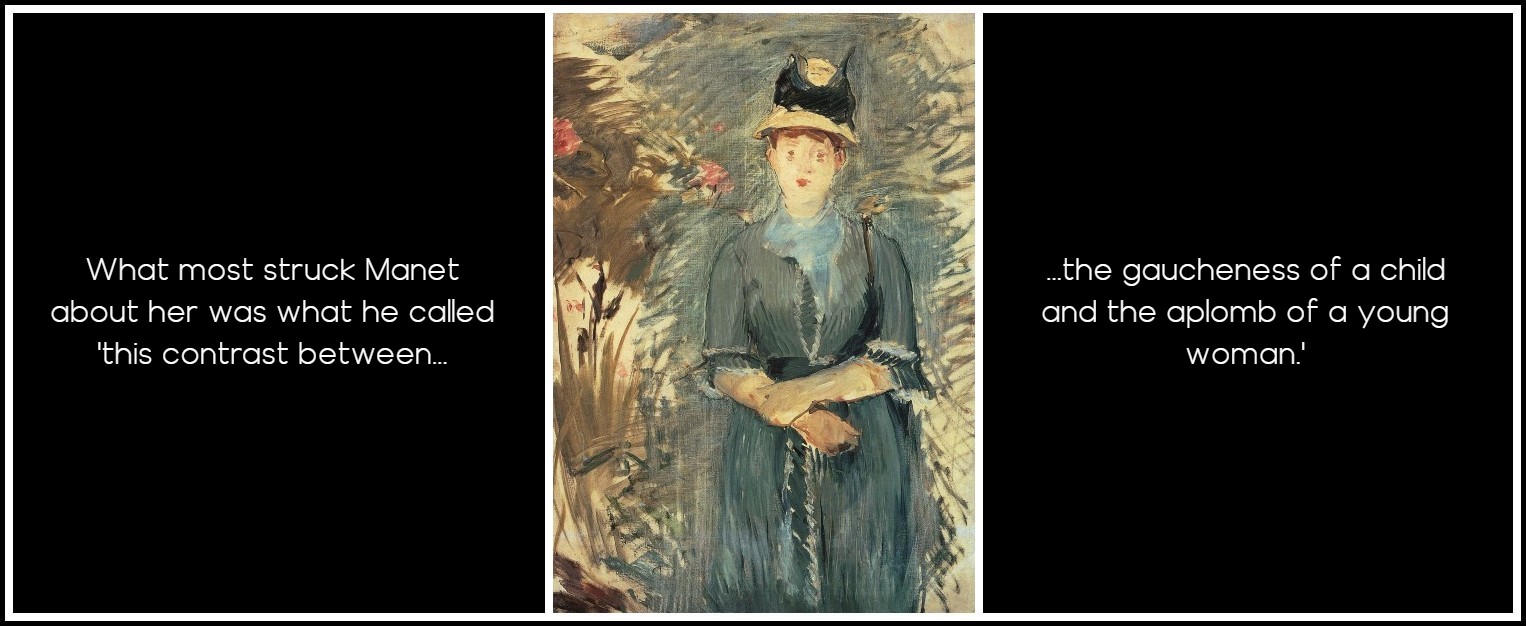

This sort of ambiguity toward women, and toward desire itself, runs throughout Manet’s paintings. Still, the bridge between the visible and the invisible is one that the art of painting cannot easily cross, and it is one that Manet seems to have contemplated a good deal during the final years of his life, along with the contradictory nature of human behavior. Antonin Proust tells us how one day during those last years, when he and Manet were walking in Meudon, they met a young girl who was selling flowers. What most struck Manet about her was what he called ‘this contrast between the gaucheness of a child and the aplomb of a young woman.’ The contradictory and mysterious reflection of the woman in the mirror, which allows us to see reality in more than one way at the same time, presents the same kind of contradiction that Manet had noted in the young flower girl.

Manet, Girl among Flowers, 1877

Although this kind of multiple point of view has been described as anticipating the supposed multiple viewpoints of Cubism, it seems that something very different is involved here. What we seem to be offered instead is the sort of psychological view of a person that is commonly given in literature but generally almost impossible to give in painting: we are shown two different realities at the same time. The mirror quite literally forms a bridge between the visible and the imaginary, inscribing on its surface both an image of the real world and a representation of reverie. This discrepancy makes us sharply aware of a difference between inner and outer perceptions of things—a task nearly impossible in traditional painting. A kind of interior monologue develops as we become intensely aware of the interaction between these two different psychological realities. It has been suggested that at least some of what we see in the mirror can be taken to be a visualization of what the woman is actually thinking. Although this may be too literal a statement when baldly stated this way, it should not be dismissed out of hand, since the image in the mirror is surely to be taken as a mental construction as well as the depiction of a physical reality.

Photo: Nick Page, Unsplash

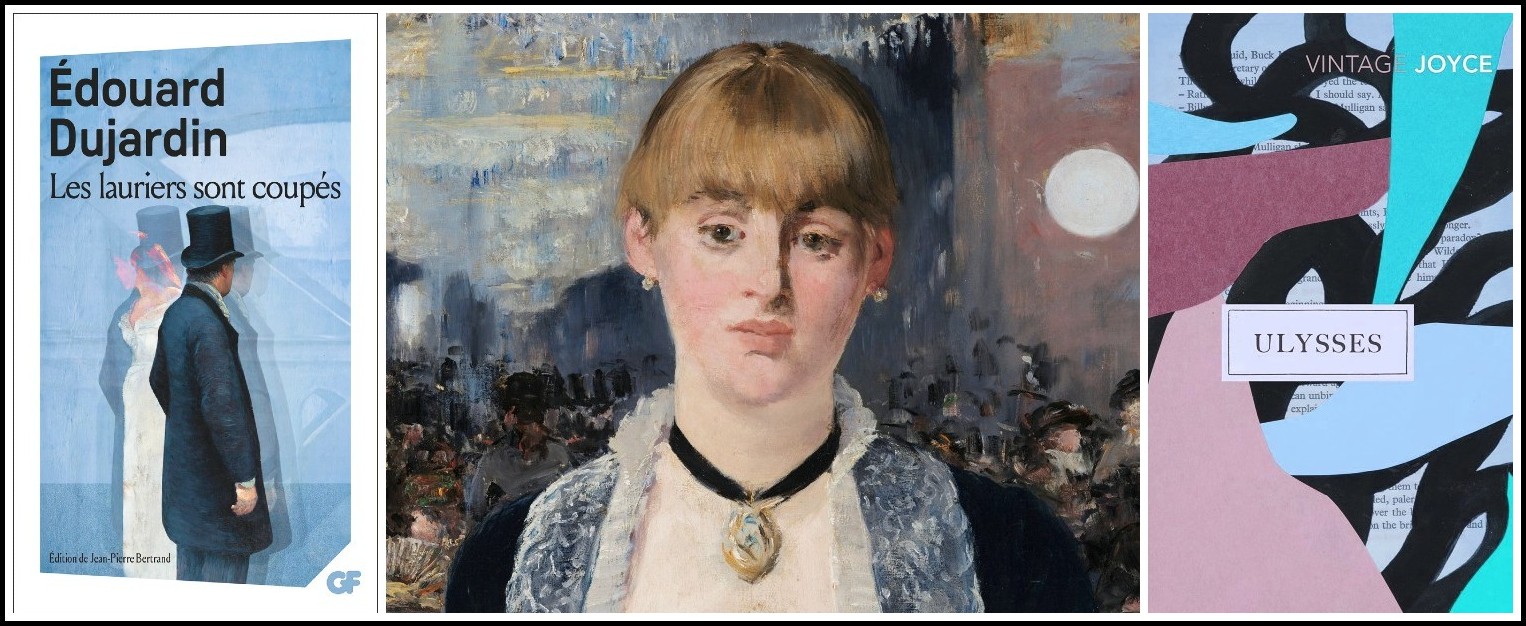

In fact, the use of multiple viewpoints in the Bar is strikingly similar to Edouard Dujardin’s development of what he called monologue intérieur, in his novel Les lauriers sont coupés, published in 1887, just a few years after the Bar was painted. In the same way that Dujardin’s interior monologue (which directly inspired Joyce’s ‘stream of consciousness’) made it possible for the reader to perceive experience both from the inside and the outside of his characters, so Manet in the Bar allows us a similar double vision through the medium of the magical mirror. Leon Edel has remarked that in ‘the novel of subjectivity,’ which was pioneered by Dujardin, ‘we become observer and actor at the same time.’ In the same way that Dujardin stresses the ‘unheard and unspoken speech by which a character expresses his inmost thoughts,’ and the way those ‘inmost thoughts’ are recorded ‘without regard to logical organization,’ so Manet probes the interiority of the woman through a multiplication of narrative surfaces. Valerie Larbaud’s description of the motivation for Dujardin’s innovation could also describe what Manet was doing in the Bar—and what, in very different ways, he had done in so many of his other paintings: ‘He wanted to express something that had not been expressed before him; and it is this that led him to the discovery, to the creation of this form.’

Dujardin, Les lauriers sont coupés, 1877 | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (detail) | Joyce, Ulysses, 1922

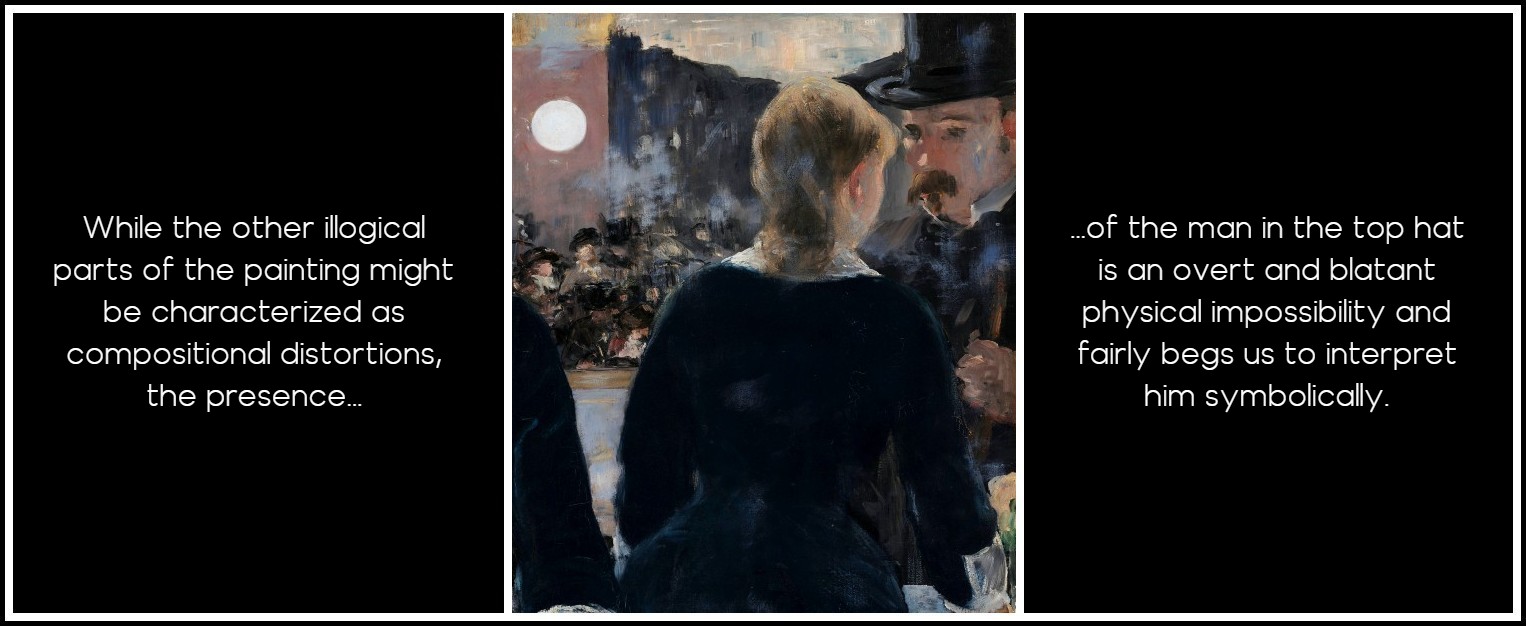

As Stephen Kern has pointed out, Dujardin’s development of monologue intérieur was indicative of radically changing ideas about time and happening during the 1880s, and symptomatic of abrupt shifts in chronological sequence and narrative viewpoint in writing of the period. In many ways Manet’s painting, like Dujardin’s book, expresses ‘the inner workings of the mind with its brief span of attention, its mixture of thought and perception, and its unpredictable jumps in space and time.’ If part of the modernity of Manet’s earlier paintings was expressed in their discordant spatial shifts, sense of alienation, and paralyzed narratives, in the Bar he explores the possibilities of multiple narratives and multiple levels of consciousness, and connects the manipulation of space to that of time. Our sense of actual space and time are particularly called into question by the presence of the man in the top hat. For while the other illogical parts of the painting might be characterized as compositional distortions, his very presence is an overt and blatant physical impossibility and fairly begs us to interpret him symbolically.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (detail)

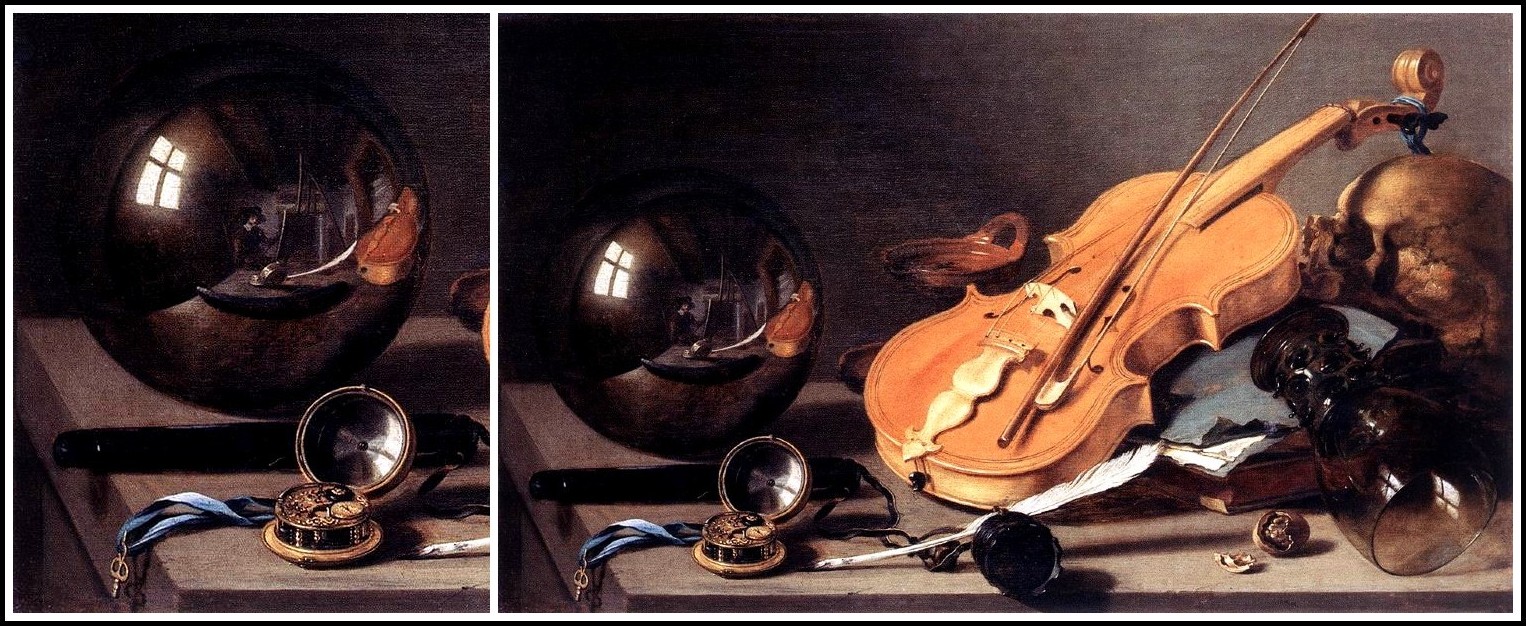

One aspect of the Bar that seems to have been given surprisingly little serious attention is the way that it draws upon a number of fairly traditional iconographical points of reference. The combination of the mirror reflection, the young woman, the flowers, and the worldliness of the place and of the objects within it are standard features of the iconography of vanitas paintings, or remembrances of mortality.

Pieter Claesz, Vanitas with Violin and Glass Ball, 1628

Even the kind of flowers represented is significant: roses were considered a symbol of love and beauty, an image of the transience of beauty, and an emblem of Venus.

Jan Davidszoon de Heem, Vanitas with Skull, Book and Roses, 1620 | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (detail)

Within this context, it is interesting to see the man in the top hat as playing some of the same eerie role that figures of Death do in danse macabre imagery and in representations of the theme of Death and the Maiden, further reinforcing the vanitas symbolism. This is a theme that was dealt with in poetry and music by a number of Manet’s contemporaries. Saint-Saëns’ Danse Macabre was published in 1874, and Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death dates to 1875-1877. The theme had also been treated by Baudelaire, by Sully-Prudhomme, and by Theophile Gautier. And Manet, moreover, presumably would have been familiar with numerous Renaissance depictions of the theme. The mysterious, eerie quality of the figure of the man, whose features have been described as ‘almost waxen in their rigidity,’ is emphasized by the fact that he quite literally appears to be a kind of phantasm without a clear corporeal reality. My point here is not that this man must unequivocally be read as a literal personification of Death, but rather that Manet strongly suggests the possibility of such a reading, thus adding an allegorical overtone to what at first appears to be a scene from everyday life. And within the generally naturalistic framework of the painting, he pushes this suggestion as far as he can without crossing the line into overt fantasy. The Bar not only contains certain traditional aspects of vanitas imagery, such as the mirror, the young woman, the flowers, and the fruit, but the very nature of the place that is represented—the music hall with its atmosphere of manufactured gaiety—reinforces the subject of the vanity of worldliness, of material possessions, and of sensuality. Moreover, the picture is painted with a tremulous, suggestive brushstroke that emphasizes the fleeting nature of the worldliness that we see reflected in the mirror.

Mussorgsky, Songs & Dances of Death | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (detail) | Saint-Saëns, Danse Macabre

If in this painting Manet pushes the art of painting to a limit, he also pushes the capacities of the viewer to a limit, perhaps beyond the limits that we ordinarily are willing to tolerate in a naturalistic painting. In giving us more than one view of that which is present, the artist evokes other, absent meanings. A Bar at the Folies-Bergère gives to everyday life a resonance that transcends the quotidian. In this way, Manet was able to remain within the general framework of realist painting without having to accept its more mundane limitations. In the Bar at the Folies-Bergère, he transcends the limits of naturalism by deconstructing naturalistic space from within its own conventions and in a sense deconstructing realism itself.

Architectural photo: Ricardo Gomez Angel, Unsplash | Photo of Manet: Alphonse Leroy

CONTINUED IN PART 3 (SEE ‘RELATED POSTS’ BELOW)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments