Looking into the Abyss: The Poetics of Manet’s ‘Bar’

MANET: A BAR AT THE FOLIES-BERGÈRE – ANALYSIS – PART 3

Jack Flam

Jack Flam, Emeritus Faculty, is Distinguished Professor of 19th- and 20th-Century European and American Art, City University of New York Graduate Center.

Condensed from Jack Flam, ‘Looking into the Abyss: The Poetics of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère’

in Twelve Views of Manet’s ‘Bar’, ed. Bradford Collins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996) pages 174-180

THIS IS PART 3 OF THE ESSAY: READ PART 1 FIRST

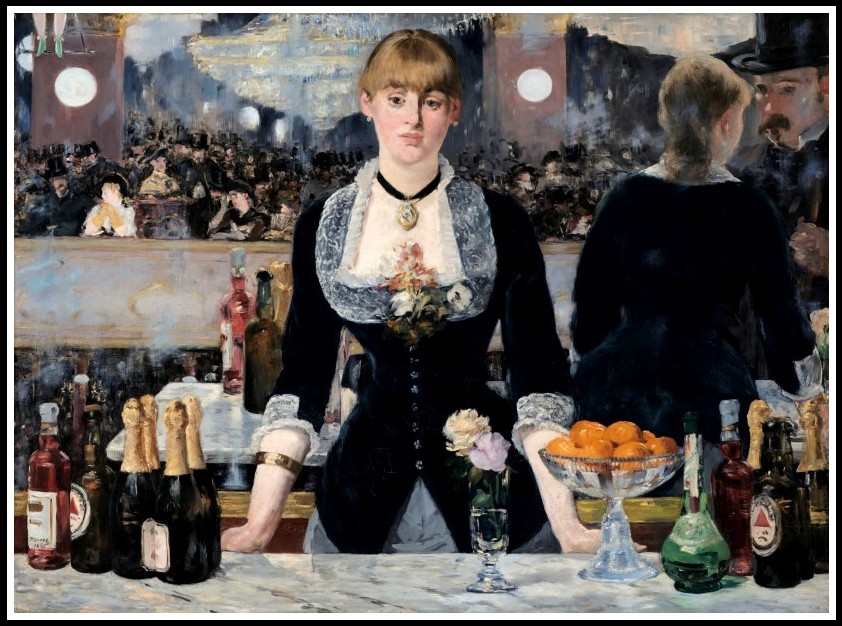

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82

IV. ART AND ARTIFACT

Clearly, one of the main subjects of A Bar at the Folies-Bergère is desire. I do not think that one can say, however, that this projection of desire necessarily privileges only one of its forms. While the possible sexual availability of the woman can be seen in relation to clandestine prostitution, this is only one of the forms that desire takes in this picture, and I believe that to insist on its primacy limits our view of the painting. The woman is presented as an object of desire, whether or not she is actually available. And in a sense she is emblematic of the world that is mirrored behind her, which is full of pleasures that are in themselves desirable—as are the bottles, the flowers, and the sunny mandarin oranges in the bowl before her. Aside from the fact that Manet painted the picture when he knew he was dying, I think that one has to see this painting in large measure as a projection of desire in the abstract, as a kind of longing to grasp that which is fragile and fleeting, very much present yet constantly elusive.

Photo: Arpit Dhore, Unsplash | Manet

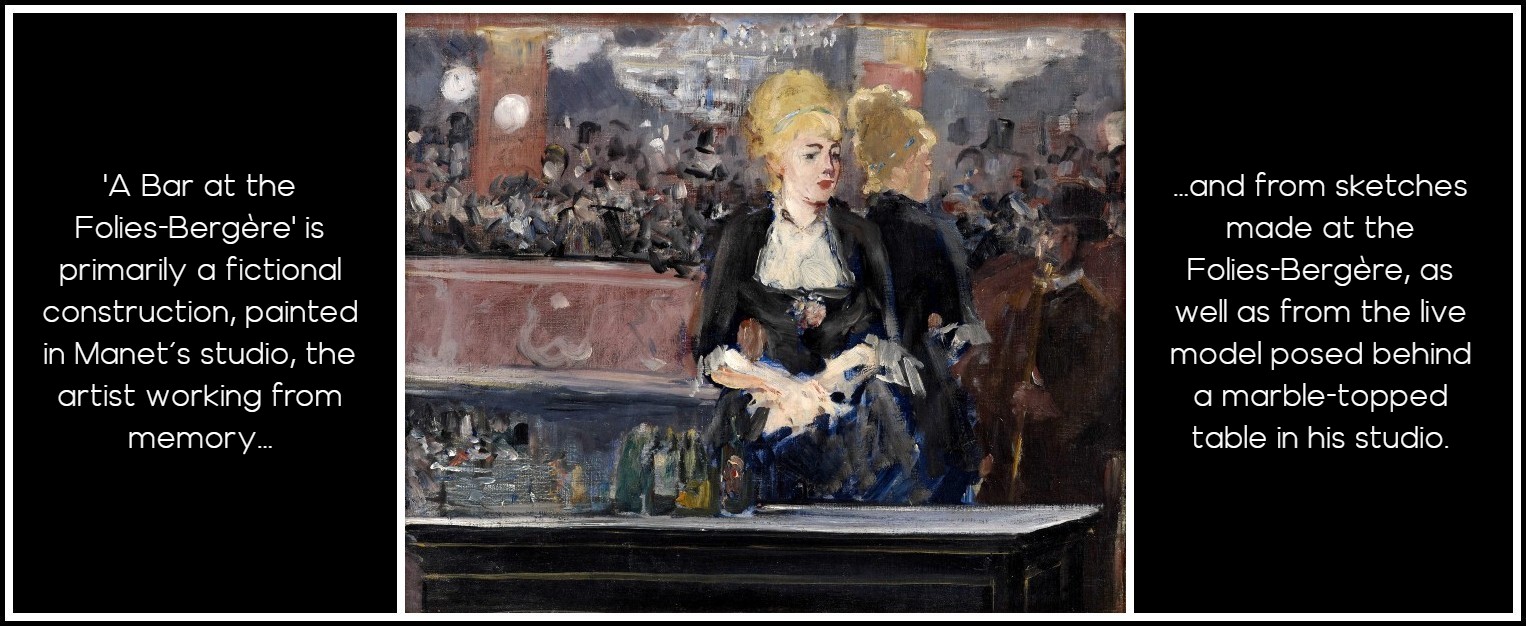

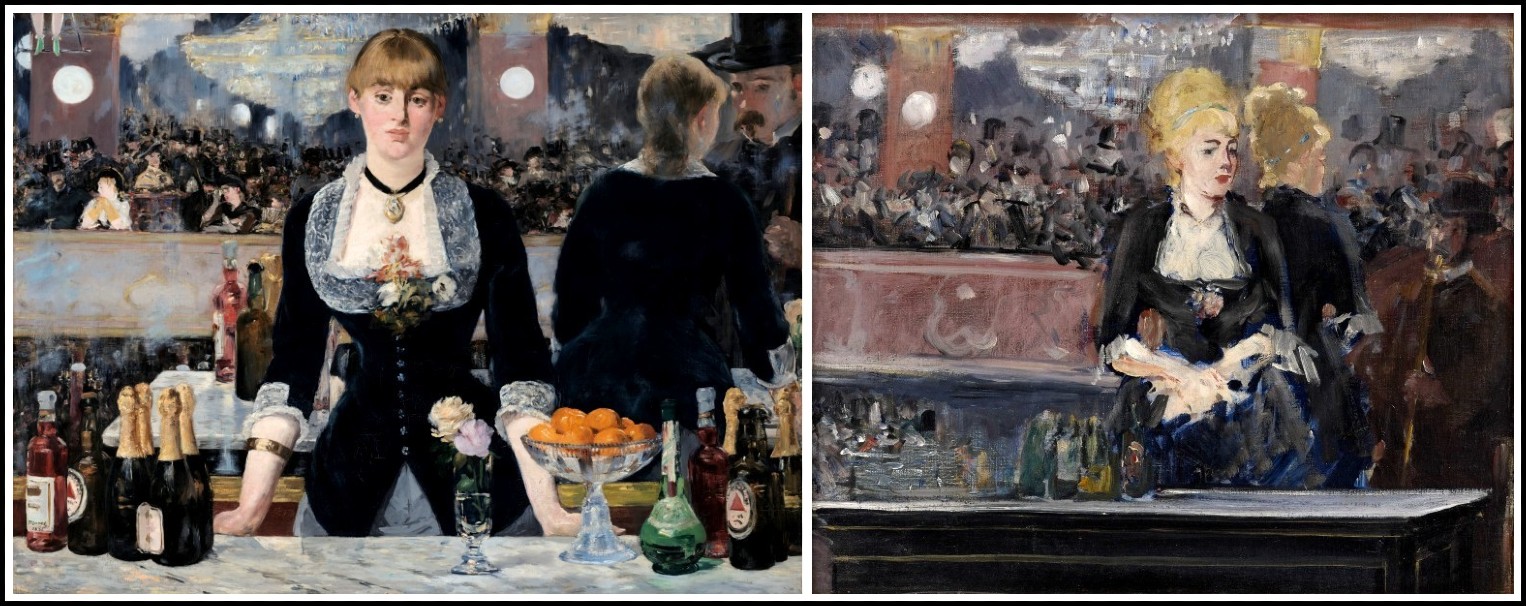

A painting like A Bar at the Folies-Bergère can, of course, be used as a form of social documentation, as an image of an actual place and ambiance, as a kind of illustration of manners and mores. At the same time, it is difficult to say what this sort of information tells us about the Bar as a work of art, or just how reliable the deductions drawn from an unmediated consideration of such information may be. For A Bar at the Folies-Bergère is primarily a fictional construction, painted in Manet’s studio, the artist working from memory and from sketches made at the Folies-Bergère, as well as from the live model posed behind a marble-topped table in his studio. According to the painter Georges Jeanniot’s eyewitness account, the model, a pretty girl, was posing behind a table laden with bottles and comestibles. Manet, though painting from life, was in no way copying nature; I noticed his masterly simplifications; the woman’s head was being formed, but the image was not produced by the means that nature showed him. All was condensed; the tones were lighter, the colors brighter, the values closer, the shades more diverse. In fact, the degree to which Manet meant the Bar to be a poetic rather than a literal interpretation of its subject can be seen by comparing the painting to the small oil sketch he did during the summer of 1881, before he started the final painting, which shows a rather different scene. Leon Leenhoff described this picture as follows: Sketch for the Bar at the Folies-Bergère. First idea for the picture. It is the bar on the first floor, to the right of the stage and the proscenium. Portrait of Dupray. Was painted in the summer of 1881. The information on the Lochard photograph card is more specific: Painted from sketches made at the Folies-Bergère. Henri Dupray is talking to the barmaid in the studio on the rue d’Amsterdam.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881 (oil sketch)

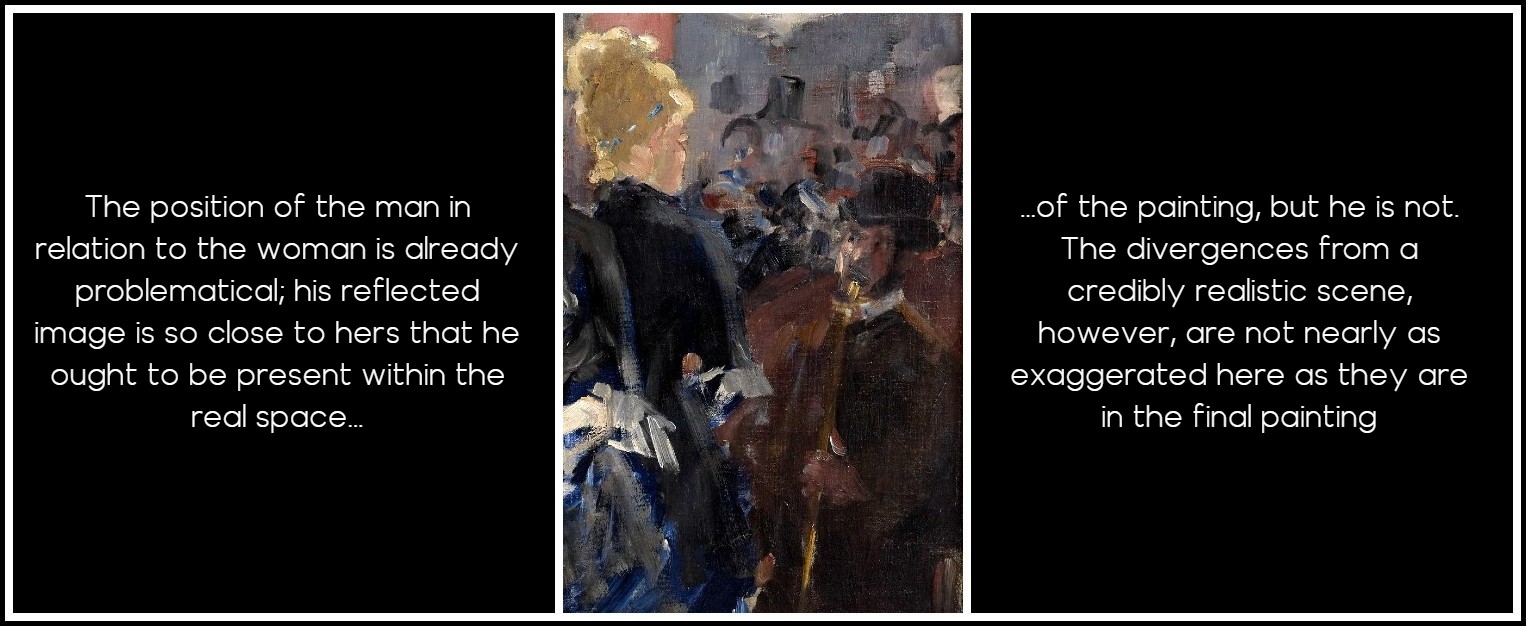

The oil sketch provided the basis for the Courtauld painting in a very direct way. As is apparent from x-rays, Manet originally had transferred the basic elements of the oil sketch to the larger Courtauld canvas and used that composition as a point of departure, which he gradually modified and developed into the image that we now see. The painstaking process of revision was made even more difficult by Manet’s illness. According to a letter from Eugene Manet to Berthe Morisot, Manet reworked the canvas extensively: ‘He is still reworking the same picture: a woman in a café.’ In the oil sketch the barmaid and the man beside her are seen at a greater physical distance than in the final painting. The objects on the bar are more realistic, as is the woman’s reflection in the mirror. (It ought to be noted, however, that the position of the man in relation to the woman is already somewhat problematical; his reflected image is so close to hers that he ought to be present within the real space of the painting, but he is not.) The divergences from a credibly realistic scene, however, are not nearly as exaggerated here as they are in the final painting; and because of the sketchy paint application, and because the frame of the mirror is not shown, the spatial discrepancies are not nearly as troubling.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881 (oil sketch; detail)

The psychological relationship between the man and the woman is also much less equivocal in the sketch. The man regards her with an openly hungry look. The discrepancy between their heights, and between the impassivity of the woman and the man’s apparent lust are quite striking. Here one could clearly make a case for the image overtly representing a potential sexual encounter. Because the large, rather blowsy woman seems so hard-bitten and so indifferent to the nasty-looking little man’s advances, we are intensely aware that his only possibility of possessing her would be by purchasing her favors. And because of the way Manet has represented them, it is also evident that this possibility is very much on the man’s mind. But one of the main themes of the painting is that his open (and rather repellent) lasciviousness seems to be thwarted by her aloofness. Compared to the final painting, the oil sketch seems more like a slice of life, with a more nearly narrative subject. It is much closer to the modalities of popular illustration than is the final painting. One might even say that the oil sketch shows us to a large degree the kind of everyday subject that Manet eventually distanced himself from in the course of reworking and revision. It is anecdotal and contains a fair measure of what might be called social realism—elements that were utterly transformed in the final painting. In a sense, it tells us a lot about what the final painting is not.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881 (oil sketch)

My emphasis on the fictive, poetical qualities of the final painting is not meant to imply that we can simply disregard either the social context in which the painting appeared or those aspects of its setting that are relevant to our interpretation of the image as a painting. The question remains as to how we can judge the degree of mediation involved. What are some of the things that it might be useful for us to know in order to reintegrate the painting into its social context? There has been a good deal of discussion, for example, about just where within the actual Folies-Bergère this painting is supposed to be set. It now seems fairly certain that the setting evokes a bar on the first floor balcony of the Folies, although Manet largely reinvented the place in his picture. As will be seen below, knowing where in the Folies-Bergère the Bar was set does help enhance our sense of the picture. A good deal of attention has also been given to the people who posed for the characters in the painting. The model for the barmaid has been identified as a woman named ‘Suzon’ who actually worked in such a job at the Folies. Other than her given name, though, virtually nothing is known about her—apparently not even her family name. Moreover, as she is represented in this painting, she has quite clearly been transformed into a kind of fictional character. This is especially evident when one compares the way she is depicted in a pastel portrait that Manet did of her around the same time that he painted the Bar, in which she bears strikingly little resemblance to the woman represented in the Bar.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881 (oil sketch; detail) | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (detail) | Manet, Study for the Barmaid, 1881

In much of the literature about the Bar, there seems to be a certain amount of confusion between what might be called seeing the work of art as an historical artifact, and seeing it as a work of art, or poetic image. Although Manet’s Bar draws upon the ambience of the Folies-Bergère as it actually existed in the 1880s, it is not so much a painting about Paris per se, as it is a painting about Manet’s relationship to his Parisian milieu—and, by extension, about the uncertainty of human relationships and of life itself. And this of course raises the question of what is actually happening in the painting, and the related question of whose story the painting tells.

Photo: Sairo, Unsplash | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (detail) | Manet

V. FURTHER REFLECTIONS

The relationships between the various elements of the painting suggest several different scenarios, all of which have a certain internal consistency, and none of which, I believe, can be privileged exclusively over the others. Like the pictorial structure of the painting, its narratives are complex, fractured, disjunctive, and self-reflexive. The mirror in the Bar both reveals and distorts much of what we see. On a simple physical level, it shows us what the woman is seeing, for the mirror that is behind her and in front of us allows us to see what else (besides ourselves) is in front of her. The mirror reflection also allows us to see what is behind us as we contemplate the painting, and locates us within a spatial continuum that makes us to some degree participants in the painted event. This is something that Manet had done in a number of his earlier works, such as Olympia and the Déjeuner sur l’herbe, in which the viewer’s presence is made explicit by the outward stare of someone inside the painting.

Manet, Olympia, 1863 | Manet, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863

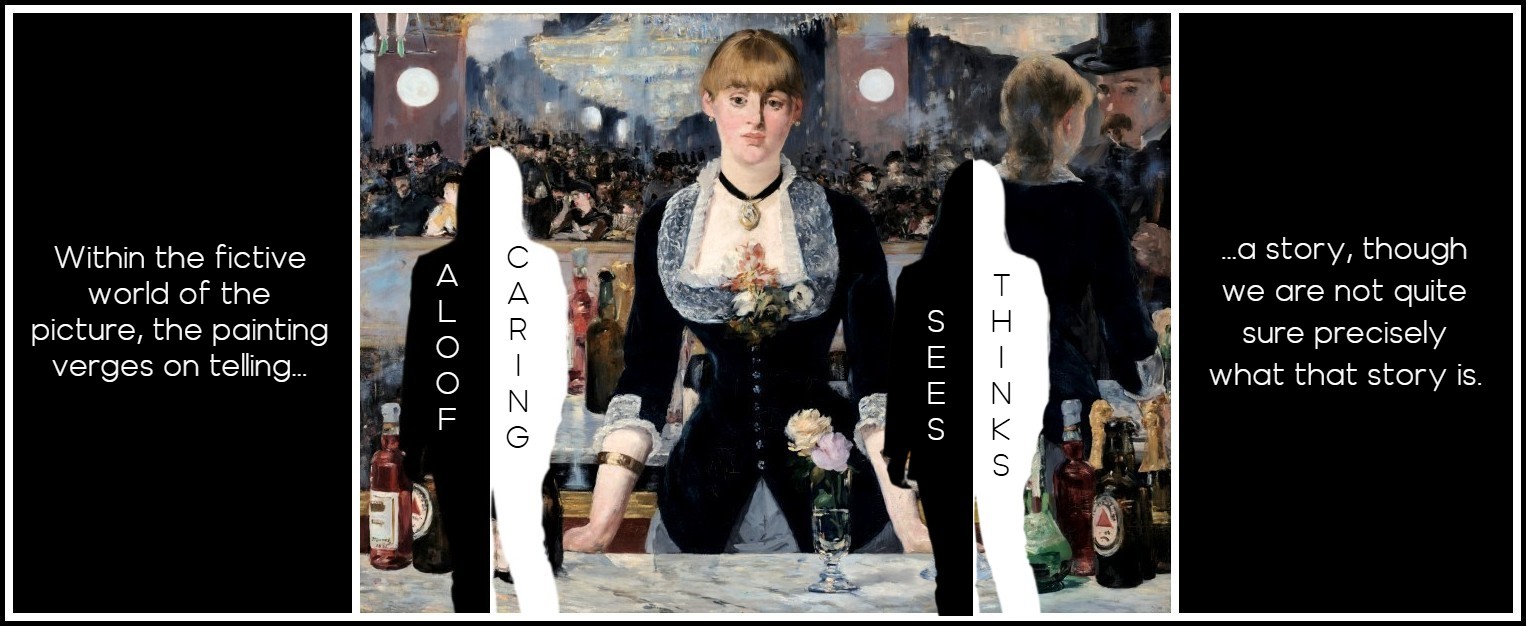

But in the Bar, the relationship between the woman and the spectator is much more ambiguous. She looks out toward us, but does not really engage us, nor even seem to see us. She seems in fact to look past us, or even to look through us, as if we were not even there. And it is this combination of our own simultaneous presence and transparency that is one of the most unsettling aspects of the whole picture.

Photo: Pascal Meier, Unsplash | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (detail)

The painting also seems to verge on telling a story, though we are not quite sure precisely what that story is. One obvious possibility is that the image in the mirror brings together what the barmaid sees and what she thinks. In this reading, the presence of the man is like the visualization of a thought in her mind, something contemplated, perhaps even desired, but not actually present. Another reading is that it is the observer who reflects upon the duality of the woman, seeing her on the one hand as cool, aloof, and detached, and on the other as responsive, warm, and caring. This reading allows for two definitions of ‘the observer’: either as ourselves as we stand before the painting, or as ourselves as embodied by the man in the top hat. Although these are radically different constructions of the observer, the openness and equivocal nature of the painting support and seem to invite them both. And of course, within the fictive world of the picture, it is possible to conceive of ourselves as both, just as we psychologically position ourselves differently to a written text that changes from the first to the third person in the course of its narrative.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82

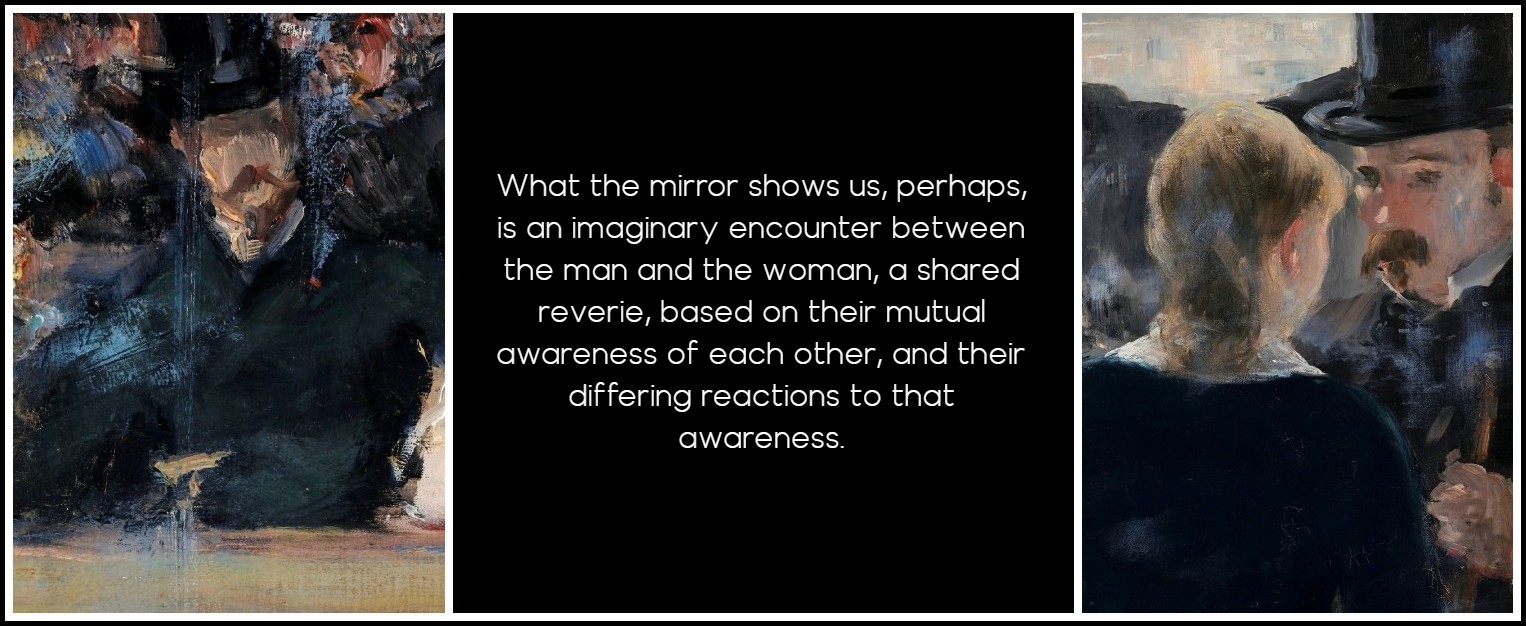

As we have seen, the mirror reflection allows neither room for us nor for the man in the top hat, so that in a sense we are equally disembodied viewers, though in different ways: we are able to exist only outside the mirror, while he is able to exist only within it. In a sense, we are his double. Another, rather more literal narrative reading emerges. We have noted that only a single figure on the far balcony seems to look directly at the woman—the mustachioed man with the top hat who bears a striking resemblance to the man who addresses the barmaid. This suggests another persuasive reading: that what we see is this man’s view of the woman. It is he who stares at her from the distant balcony, unseen by her, imagining himself as the object of her attention. He not only resembles the man addressing the girl, but formally rhymes with him and is in a sense his double. The compression of the picture space, what we have referred to as the magnifying effect of the mirror, lends an added force to the energy of his gaze. Once we realize this, we must also acknowledge that someone seen in a mirror can usually be seen by the person he sees. This phenomenon underlies what I take to be one of the strongest narrative readings of the picture, and one that is borne out by the three-part organization of the composition, as read from left to right: namely, that what the mirror shows us is a kind of imaginary encounter between the man and the woman, a kind of shared reverie, based on their mutual awareness of each other, and their differing reactions to that awareness.

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (details)

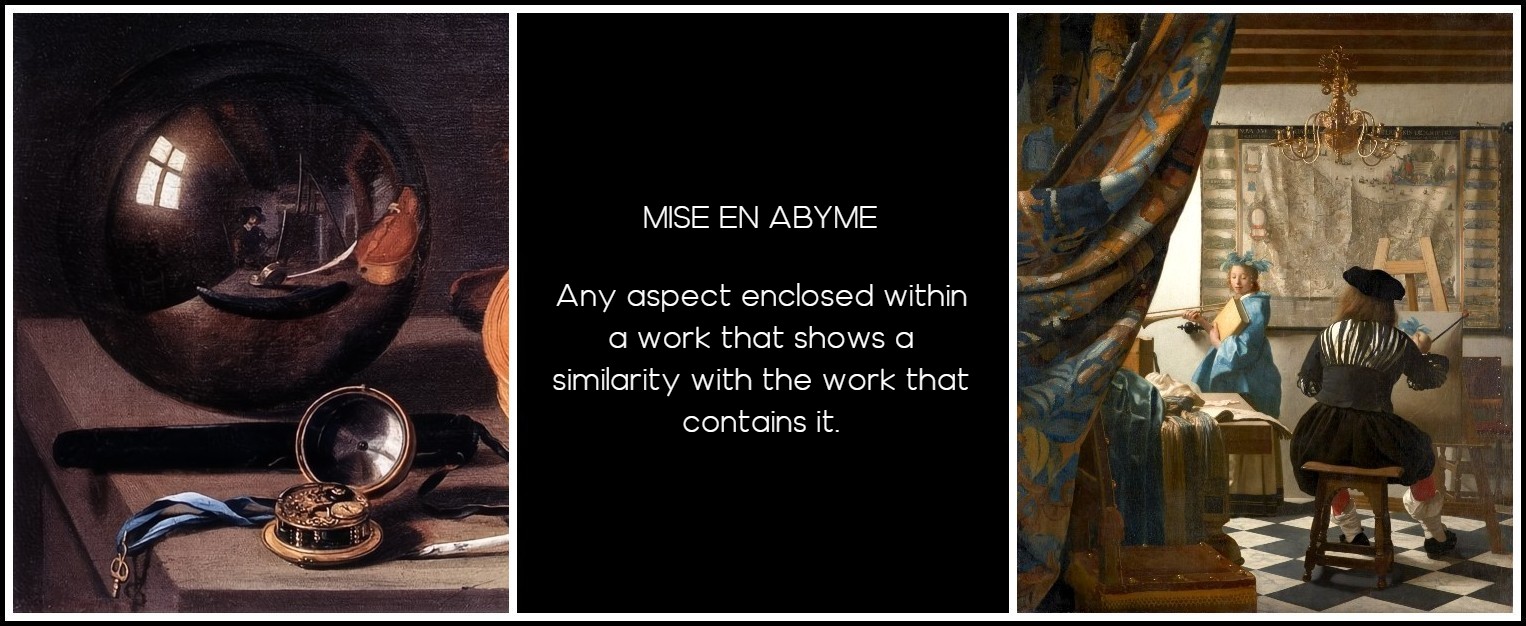

It would be tempting, given the physical resemblance between the man in the mirror and Manet himself—and given the fact that the man who posed for it was himself a painter—to privilege this reading above the others. But it is not possible to do so, any more than it would be possible to know what exactly is on the woman’s mind, or exactly how available she might be for a flirtation, or for a price. One is, nonetheless, tempted to say that in a sense the barmaid is a kind of surrogate for the artist—observer and observed—the person who unifies and mediates everything that we see before us. The paradox of the simultaneous intensification and undermining of our sense of our own reality through the use of the mirror, and the crossing of different narrative lines to multiply the picture’s narrative possibilities, is a powerful example of the expressive and symbolic potentials of mise en abyme. This untranslatable term has been described by Lucien Dallenbach as a kind of reflexion, ‘a means by which the work turns back on itself,’ and he lists among its principal devices mirrors and pictures within pictures. Dallenbach defines mise en abyme broadly as ‘any aspect enclosed within a work that shows a similarity with the work that contains it,’ and he gives three paradigms that describe the nature of mise en abyme: what he calls ‘simple’ reflexion,’ ‘infinite reflexion,’ and ‘paradoxical reflection.’

Pieter Claesz, Vanitas with Violin and Glass Ball, 1628 (detail) | Vermeer, The Art of Painting, 1667

Manet appears to use, in varying degrees, all three kinds of mise en abyme in A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. Within the mirror image are inscribed divergent doubles of things depicted in the ‘real’ space, and the undecipherable image contained within the barmaid’s locket acts as an impenetrable form of a representation contained within the overall representation, another kind of picture within the picture. Equally provocative and nearly as ambiguous are the suggestions of the infinite reflections of the mirrors on the opposing balconies of the Folies-Bergère, which Manet was able to evoke with fragmentary indications of the repeated lantern globes precisely because he assumed his viewers’ familiarity with such arrangements. But of course the most striking sort of mise en abyme in the Bar is the ‘paradoxical reflexion’ between the mirror images of the woman and the top-hatted man and the way they relate to the ‘real’ spaces around them. As Jorge Luis Borges has suggested, what disturbs us most about such paradoxical instances of mise en abyme, such as Don Quixote being a reader of the Quixote and Hamlet a spectator of Hamlet, is that ‘these inversions suggest that if the characters of a fictional work can be readers or spectators, we, its readers or spectators, can be fictitious.’

Photo (whirlpool): George C., Unsplash | Photo (man): Jaanus Jagomagi, Unsplash | Composite: RJ

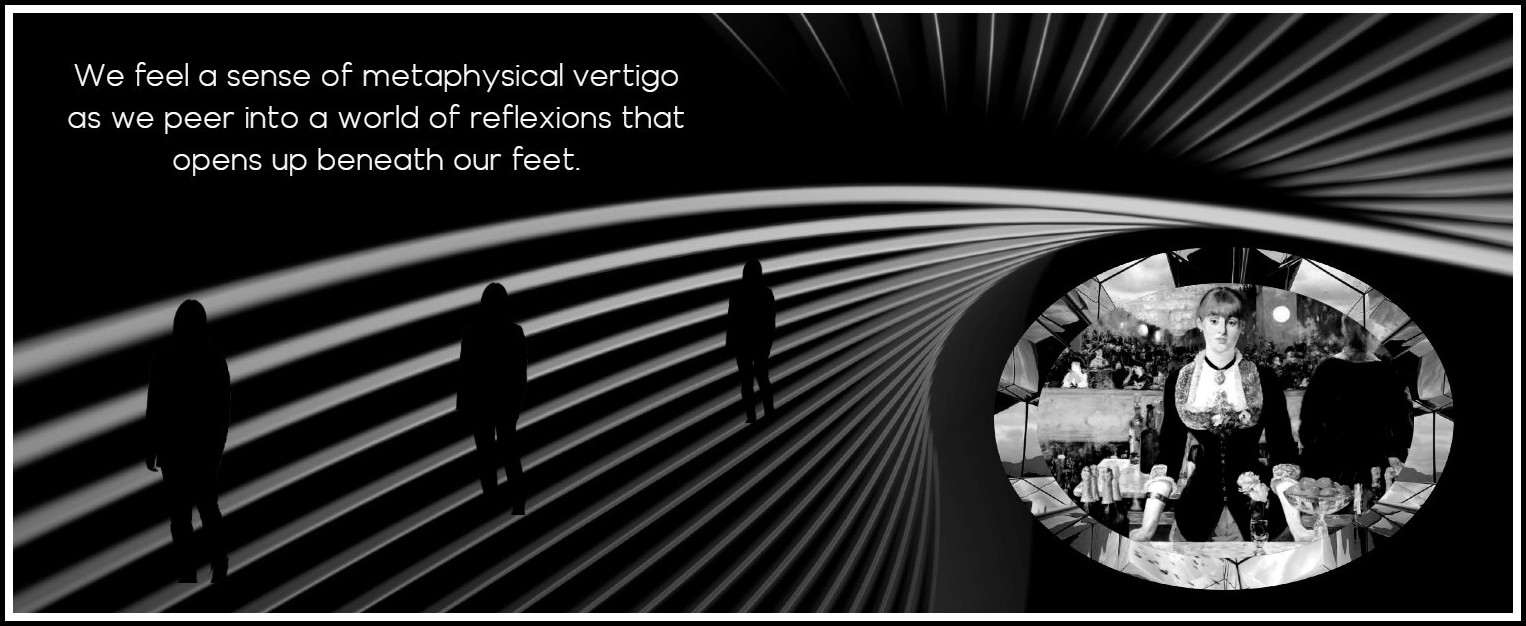

This annihilation, as it were, of the spectator’s physical reality is a crucial aspect of A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. And it is part of Manet’s more general strategy, through the use of mise en abyme, to transform what at first appears to be straightforward physical description into a kind of elliptical, metaphysical narrative. The contradictory reflections create the visual equivalent of what C. E. Magny has referred to in a literary context as ‘the sense of metaphysical vertigo we feel as we peer into this world of reflexions which suddenly opens up beneath our feet; in short, the illusion of mystery and depth inevitably produced by these stories whose structure is thus ‘en abyme.’

Photo: Kamran Abdullayev, Unsplash | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (detail) | Composite (incl. silhouettes): RJ

As is well known, Manet painted A Bar at the Folies-Bergère when he was terminally ill and aware that he would soon die. Although the readings that we have just discussed, including the interpretation of the painting as a vanitas picture, exist independently of the artist’s biography, one cannot help feeling that this picture is, among other things, a kind of farewell painting. In this context, the fact that his dear friend Méry Laurent (at the left, wearing yellow gloves and a round black hat) is the most clearly identifiable person among the portrait representations on the far balcony seems significant. (The woman to the right of her, dressed in beige, is said to represent the actress Jeanne Demarsy). In a sense, the world reflected in the mirror represents much of what Manet was most fond of—and what through memory he was able to summon up and give form to as he worked in his studio from the sparsest props: ‘A pretty girl posing behind a table laden with bottles and comestibles.’

Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (details) | Manet, Spring [Jeanne Demarsy], 1881 | Manet, Autumn [Méry Laurent], 1882

It is a world of frivolity, gaiety, high spirits, and erotic encounters, a world dedicated to surfaces and to the stirring of appetites and desires. When Manet painted this picture it was also a world that he could no longer move in, and that he quite literally had to summon by an act of imagination aided by memory. A Bar at the Folies-Bergère not only seems to sum up a number of Manet’s artistic concerns, but also appears to embody a contemplation of his own past. One can’t help remarking, for example, that the black ribbon and the gold bracelet remind us of two memorable props from Olympia; and that this bracelet had belonged to Manet’s mother, and that she had kept in it a lock of her son’s baby hair. Perhaps in this valedictory painting, Manet both personified and personalized desire in this woman, by decorating her with this bracelet. Perhaps within this context of reflection answering reflection with reflection, she is also a surrogate for the artist, both detached and engaged, absent but always present. Like the artist, she stands at the edge of an abyss, contemplating the transience of all pleasures and all things.

Manet, Olympia, 1863 (details) | Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1881-82 (details)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments