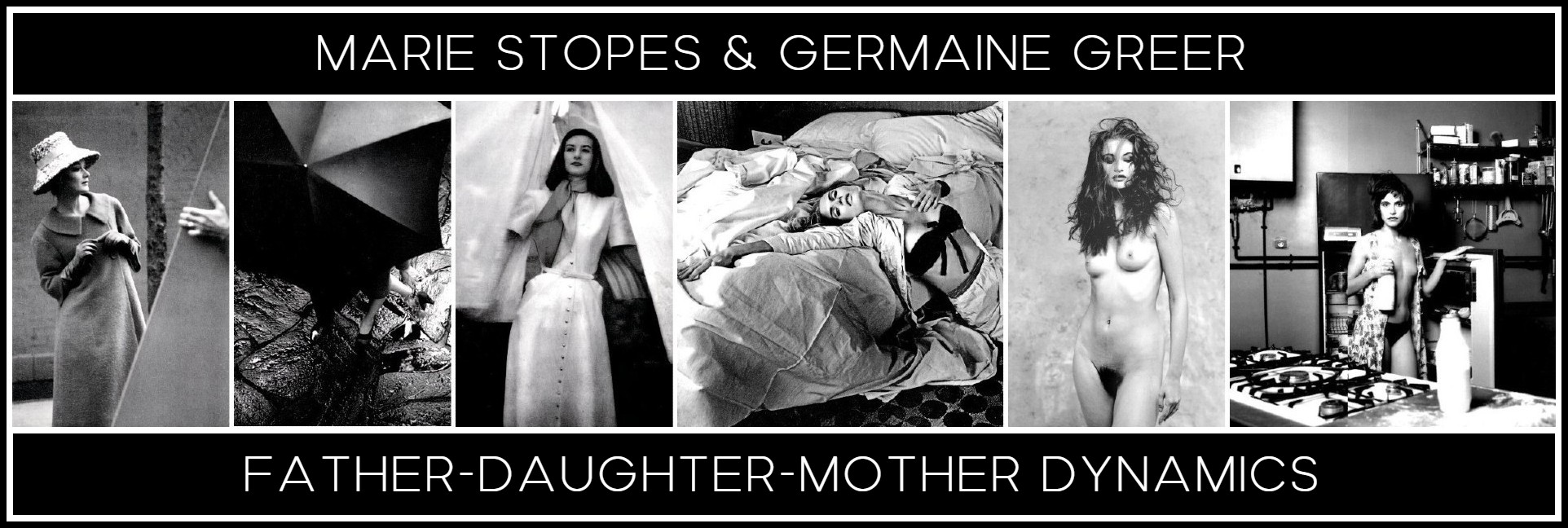

MARIE STOPES & GERMAINE GREER: FATHER-DAUGHTER-MOTHER DYNAMICS

OR

ENDURING PASSION AND THE STUMP CROSS CRONE

Christina Hardyment

Posted by kind permission of Christina Hardyment, author and journalist.

Before embarking on a trilogy of novels centred on Geoffrey Chaucer’s granddaughter Alyce, Christina Hardyment wrote eleven books on subjects drawn from literary geography, the historical background to our everyday lives, and fifteenth-century England and its literature. This essay, under the title ‘Marie Stopes and Germaine Greer: Enduring Passion and the Stump Cross Crone’ first appeared as a chapter in the book Telling Lives: From W.B. Yeats to Bruce Chatwin, edited by Alistair Horne (London: Macmillan, 2000) pp. 34-49.

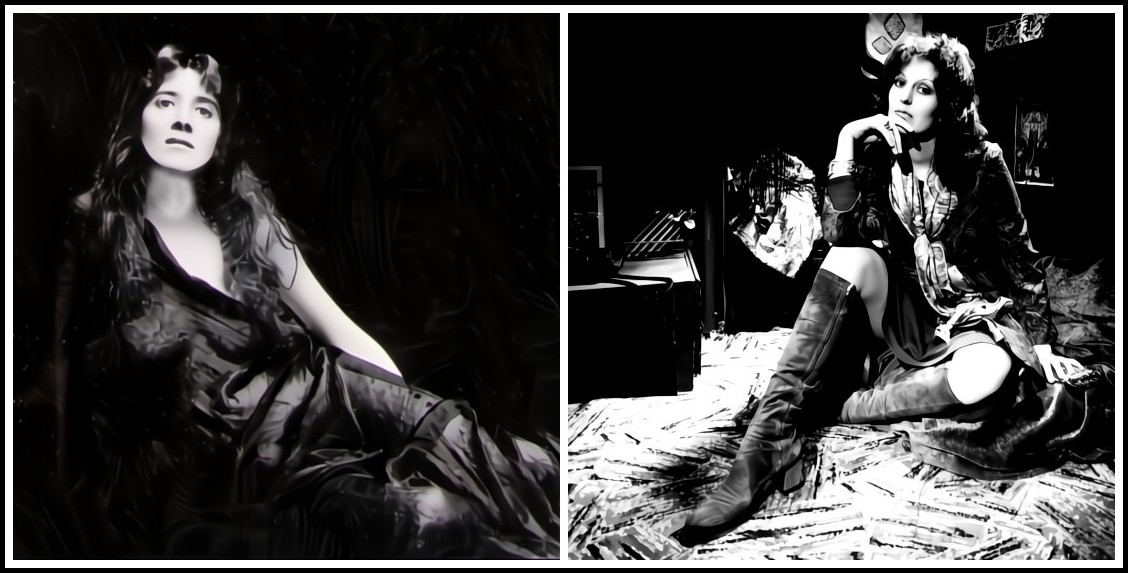

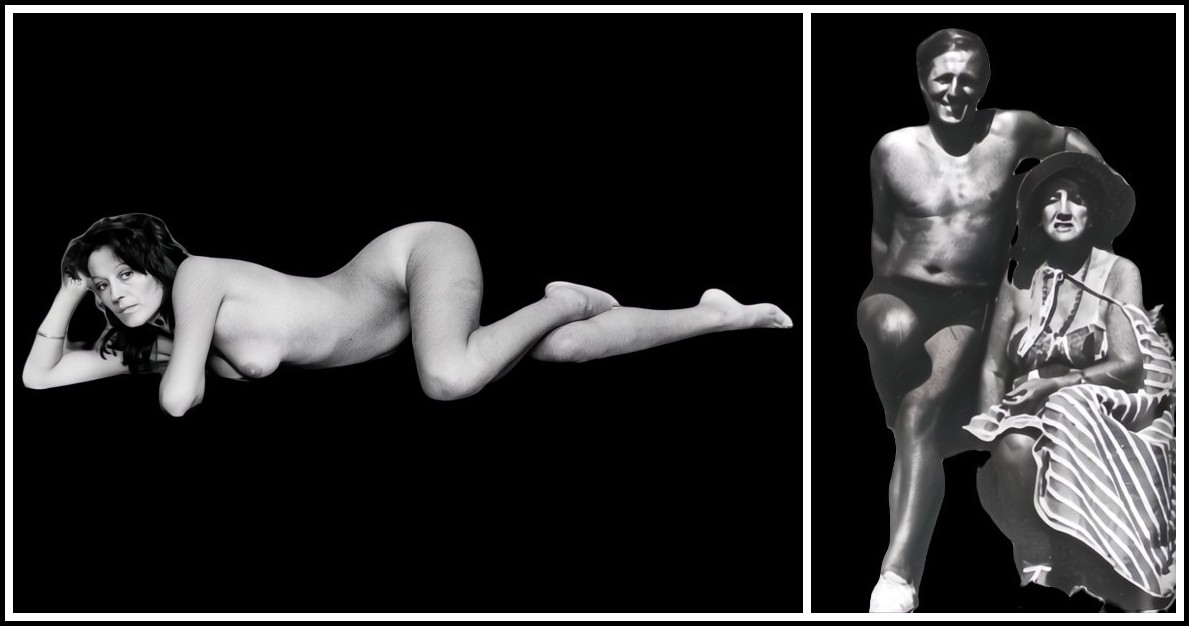

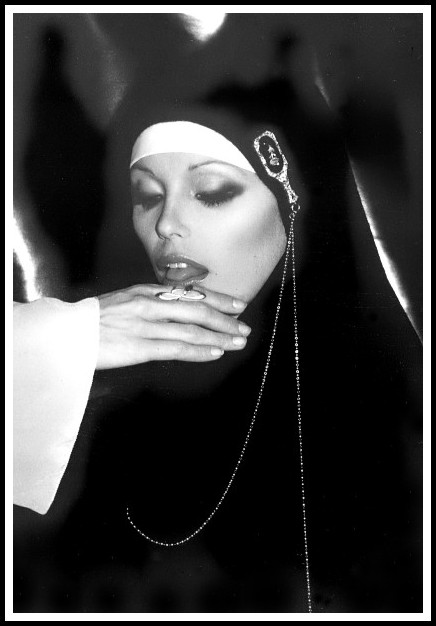

Marie Stopes | Lord Snowdon, Germaine Greer, 1971

THE INSIGHT EXPLORED IN THIS ESSAY

How did the personal lives of Marie Stopes and Germaine Greer affect their writing? And was the black pessimism of the second sexual prophet of our age caused by the manic optimism of the first? Both Marie and Germaine were oldest daughters. Both were deeply involved with their fathers and virtually at war with their mothers. Through childhood, each operated in a troika situation, an unholy competitive trinity of father, daughter and mother. Stopes won her battle for paternal attention, hence her unshakeable confidence in the ideal mate. Judging by what she says in Daddy, Greer seems to think she lost hers. Hence, perhaps, her deep-rooted distrust of such a notion.

Dudley Reed, Germaine Greer, 1983 | Marie Stopes

ONE

If your love life is good, declared forty-eight-year-old Marie Stopes in 1928, you can differ from your partner in almost every way imaginable. Conversely, though you may be compatible in every other way, if sex is unsatisfactory, happiness will be hard to come by and divorce unsurprising. Few people realize that the woman whose name became synonymous with birth control was also the person who set the agenda for today’s high expectations of sustained sexual activity in marriage. She even coined a new term for the new age of which she was the self-appointed high priestess: ‘erogamy’, by which she meant erotic love in marriage. In adopting it, she added, with what some might feel is unresolved ambivalence, we can ‘leave the ugly, slimy-sounding word “sexual” to those who still roll in the filth and who delight in the unclean echoes of the centuries’.

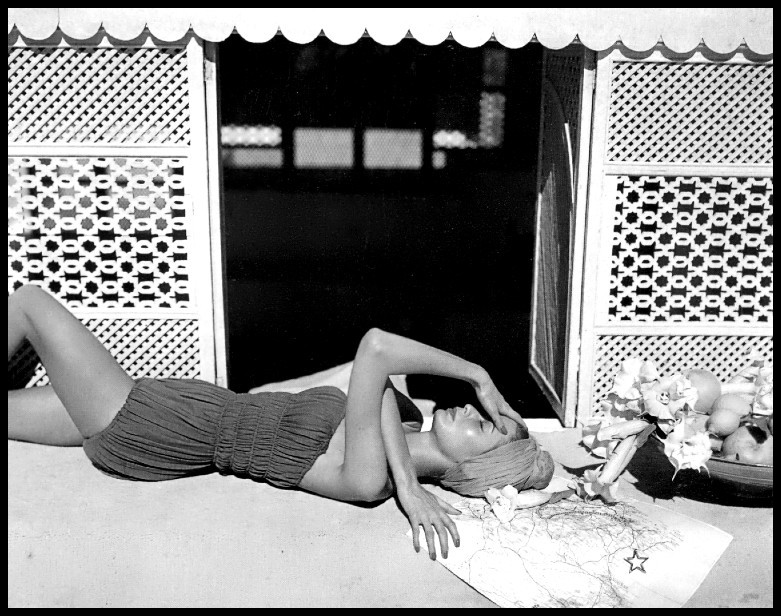

Herman Landshoff, Junior Bazaar, 1946

When Marie Stopes died in 1958, Germaine Greer was a nineteen-year-old student at Melbourne University, delighting in all things sexual and in using far stronger words as poisoned darts in her flamboyant invasion of the man’s world of the 1950s. Two decades after Stopes was tossing condoms into student audiences during her hugely popular lectures, Greer was jangling bracelets made from used diaphragm springs and was already set in the rutting that would make her in her turn a sexual high priestess. Nervous men lined the walls of the Oxford Union like hypnotized rabbits while she held forth on how sexually unattractive she found the English; she reportedly paid no attention to a request from one William J. Clinton to ‘give a Southern boy a chance’.

Herman Landshoff, Junior Bazaar, 1946

The similarities between the two women, both intellectually brilliant, socially flamboyant and bubbling with sexual energy, are startling. Both chose to write their first major book about the female orgasm. Both followed up with books about contraception, the menopause and lifelong relationships between men and women. Most striking of all, perhaps, is the way both assumed that their own lives could provide patterns for those of women in general. ‘She used her own life as the raw material to wreak changes in social attitudes, often with startling courage and with equally startling indifference to other people’s feelings’ is a sentence that could well have appeared in Christine Wallace’s biography of Greer, Untamed Shrew (1997). In fact it comes from June Rose’s 1992 Marie Stopes and the Sexual Revolution. But the differences between them were profound. To the end of her days, Stopes sang the joys of ‘enduring passion’ between the sexes. In her seventies, she was still skinny-dipping off Portland Bill with a handsome toyboy. Greer announced in her early fifties that sex had lost its attraction. She has deliberately vamped up a new role as ‘a batty old hag’, celebrating the joys of good food, friendship, animals and gardening, and writing men off as mad, bad and dangerous to know.

Keith Morris, Germaine Greer, 1971 | Marie Stopes & Avro Manhattan, 1957

TWO

Before I delved into her extraordinary career, I imagined Marie Stopes as a motherly pragmatist. Contraception has connotations of carefulness and forethought—family planning indeed. While writing a history of childcare theories, I had read her two babycare manuals, and recalled her elaborating on the importance of natural food, fresh air and exercise, and instructing mothers to have no truck with what she called the ‘aberrant mind of Freud’. Hardly a new woman. But when I turned to Married Love, her best-selling and most famous book, I soon realized that it was far from being the practical guide to contraception that I had assumed. Only two or three pages refer to the subject, and then only in the vaguest of terms. As its original title They Twain suggests, Married Love was in fact an astonishingly explicit, if rosily romantic, vindication of the sexual rights of women. Dedicated to ‘young husbands and all those who are betrothed’, it described in detail how to give their loved ones the greatest possible erotic satisfaction.

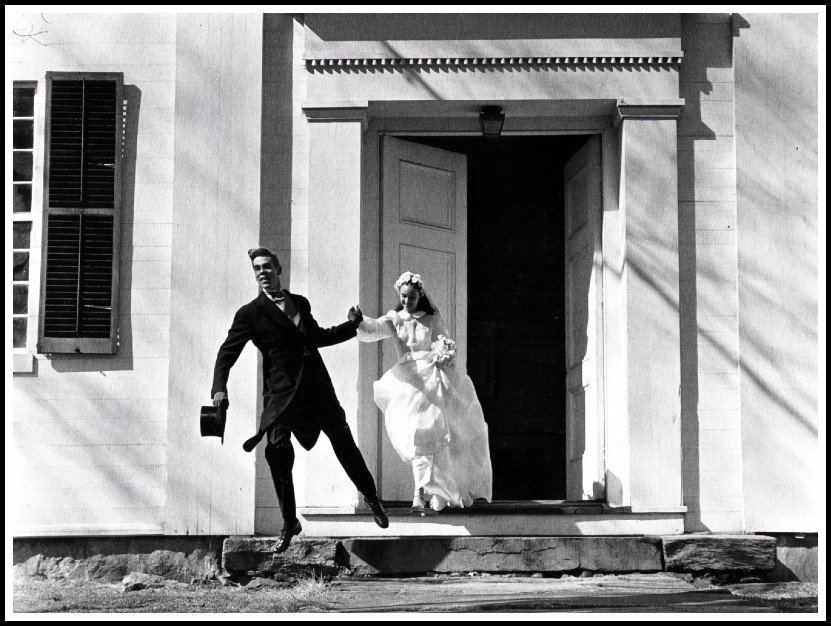

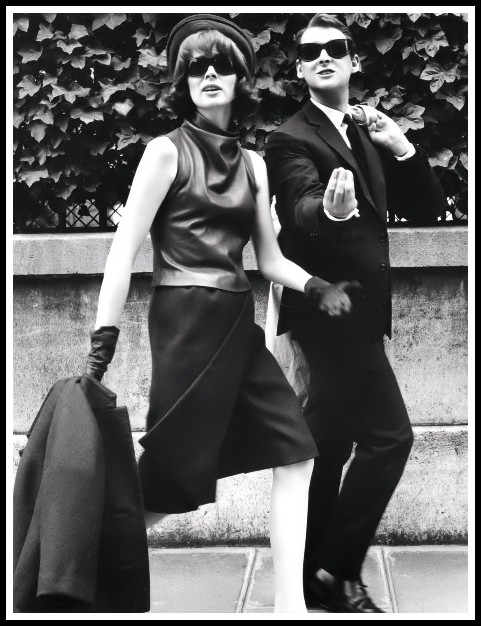

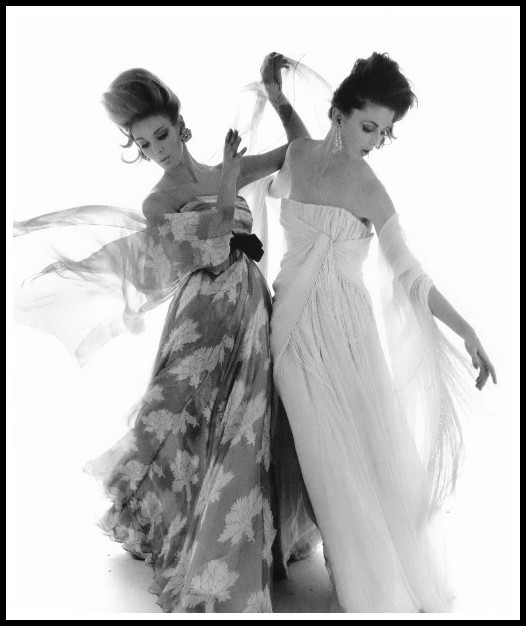

Richard Avedon, Suzy Parker & Mike Nichols, 1962

Its style is a startling combination of the passionate and the practical. Here, for example, is how Stopes introduced the concept, hitherto unheard-of in ‘nice girls’, of female desire: ‘Welling up in her are the wonderful tides, scented and enriched by the myriad experiences of the human race from its ancient days of leisure and flower-wreathed love-making, urging her to transports and to self-expression, were the man but ready to take the first step in the initiative or to recognise and welcome it in her.’ Detailed descriptions of successful foreplay techniques followed. Stopes tried (unsuccessfully) to pre-empt accusations of obscenity by claiming that her Exocet missile into the bedrooms of the nation was merely the fruit of her own ‘scientific investigations’, undertaken when (she claimed) she realized, three years after her wedding, that her own marriage had never been fully consummated. Although she read widely on the subject of ‘sexual congress’, ranging from Havelock Ellis to the Kama Sutra, objectivity was never the hallmark of her research. She described reading Ellis’s Studies in the Psychology of Sex as ‘like breathing a bag of soot: it made me feel choked and dirty for months’. Nor was Freud any better. ‘Don’t please think about your subconscious mind,’ she wrote to one sexually anxious correspondent. ‘All the filthiness of this psychoanalysis does unspeakable harm.’

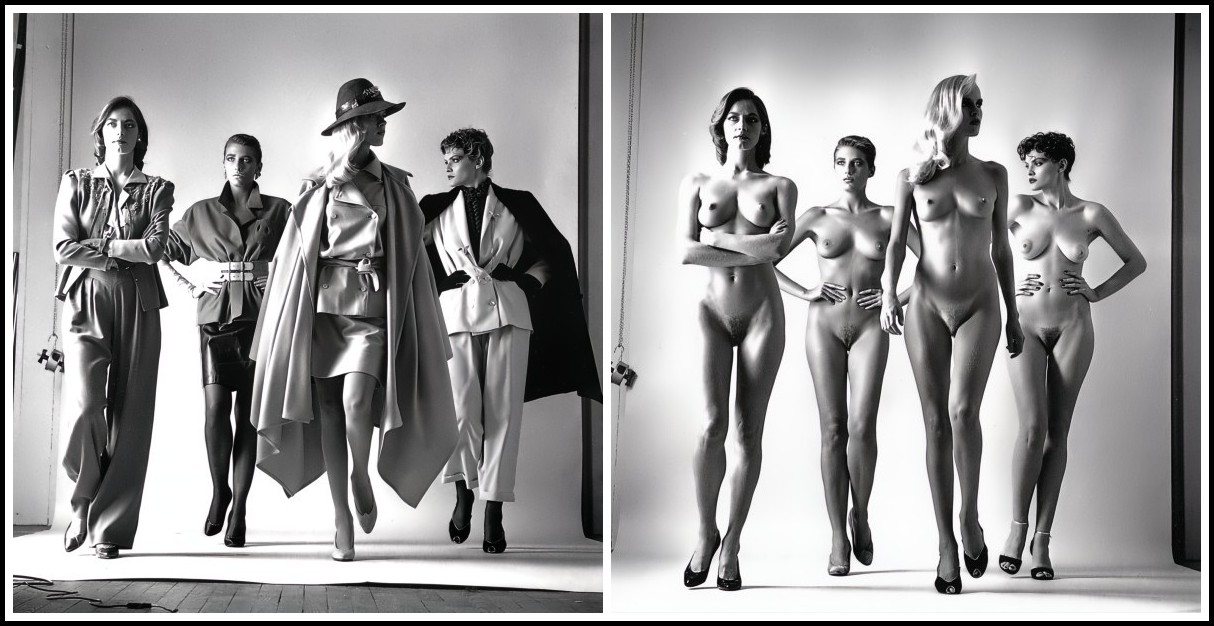

Helmut Newton, Amica, 1982

The publication of Married Love was financed by Humphrey Roe, a wealthy supporter of feminist ideals in general and birth control in particular whom Stopes would soon marry. The book first appeared in 1918, just eight months before the end of war. It was perfect timing. Women had become used to working; those over thirty had just been awarded the vote. The time was ripe for a new frankness between the sexes, though it still needed to be frankness shrouded in euphemism. The book was a runaway best-seller. Within ten years it had been reprinted eighteen times and translated into twelve languages, including Afrikaans, Arabic and Hindi. In 1935 it was placed sixteenth on a list of the most important books of the last fifty years—higher, and undoubtedly more read, than Einstein’s Relativity, Hitler’s Mein Kampf and Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. Thousands of those who bought it wrote Stopes letters registering both their gratitude and their need for much more information, especially on birth control. It was this response that made her realize how essential contraception was to sexual ecstasy.

Herman Landshoff, Junior Bazaar, 1946

Wise Parenthood, a guide to contraceptive practice, followed swiftly. Its opening line declares that, ‘A family of healthy and happy children should be the joy of every pair of married lovers.’ Note the last two words. Stopes believed that passion between twin souls, true hearts, soulmates, need never end if you got the technique right. Many of her readers found otherwise. ‘After the poetry of your book what has actually happened?’ wrote a Newark vicar. ‘We go to rest, my wife always lies with her back towards me, I make a “tender advance” and suggest that she turn round so that we may chat and cuddle–the end of the poetry is “I do not like your breath in my face!’’’ Stopes took note. In later marital manuals she made the point that people’s sex drive was as likely to be as variable as their appetite for food. Some couples made love only once in two years, some seven times a day. She added provocatively that the chance of finding a sexually compatible mate was considerably slimmer than finding someone who shared your taste in food. She estimated in Enduring Passion that 30% of men wanted more sexual action than their partner. But, she added with considerable originality, 30% of women also felt themselves inadequately served. Only 15–20% of couples were well matched erogamously. Around 20-25% did without sex altogether.

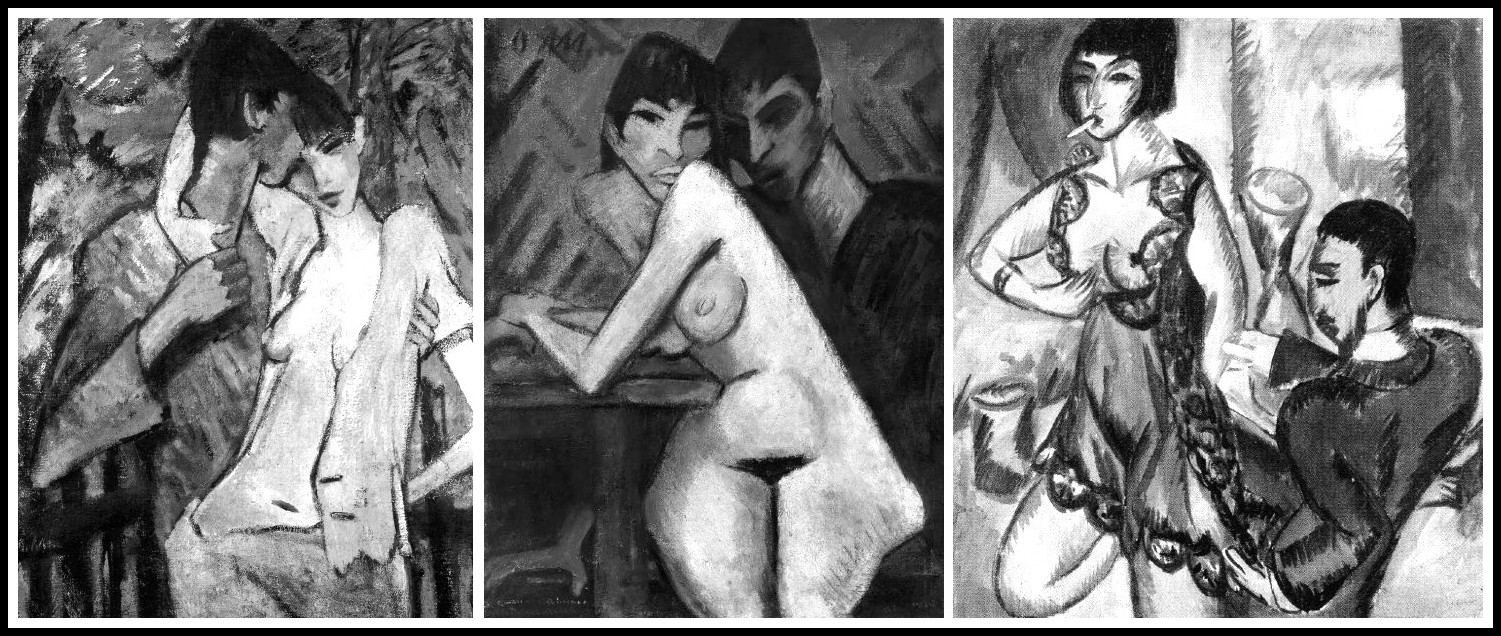

Otto Mueller, Lovers, 1919 | Otto Mueller, Couple at Table, 1925 | Ernst Kirchner, Couple in Room, 1912

The trouble with guesstimates like these is that most people like to think of themselves as on the passionate rather than the puddingy end of the erotic scale. The long-term effect of Married Love was undoubtedly to put more emphasis on the importance of enduring sexual satisfaction in marriage, and to legitimate the idea of ending a marriage because of sexual incompatibility. Stopes herself was evidently among the 30% of unsatisfied Messalinas.

Bettina Rheims, Vanessa Paradis, 2004 | Lothar Schmid, Eva Green, 2004 | Dominique Issermann, Monica Bellucci, 2003

A long train of adoring, soon-to-be-deflated men accompanied her whirlwind progress through life. The odd percipient drone escaped. ‘She is more in love with Love than with me,’ said a young zoologist, Charlie Hewitt. ‘I can see that to her man is only the personification of her great ideal love—that I cannot be.’

Helmut Newton, Calvin Klein – Vogue, 1975

Intensely feminine in her frills and furbelows and proud of her ‘buoyantly physical nature’, Stopes relished her struggle against a highly disapproving establishment. In 1920 she sent her own privately printed New Gospel to each of the 267 bishops attending the Lambeth Conference of Bishops. ‘Paul spoke to Christ nineteen hundred years ago. God spoke to me today,’ it began. His message through His new medium, imparted as she was sitting under a yew tree, was very different from Paul’s killjoy ‘marry lest ye burn’ stuff. The gospel according to Stopes was that ‘no act of union fulfils the Law of God unless the two not only pulse together to the highest climax but also remain thereafter in a long brooding embrace without severance from each other’. The bishops doggedly stuck to St Paul; the Catholic Church was predictably even more outraged. Undaunted, Stopes continued a high-profile media guerrilla war to promote birth control. Her unorthodox methods of furthering the cause included passing round Dutch caps at dinner parties and creeping into Westminster Cathedral with a Press Association photographer in tow to chain her critical pamphlet Roman Catholic Methods of Birth Control to the altar rail.

Horst, Gloved Hand and Apple, 1947

Altered image: ‘A Dutch cap in one hand, an apple in the other’

THREE

Fifty-three years after Married Love was first published, another outrageous woman’s name was on everyone’s lips and another seminal twentieth-century sexual classic was the most discussed book of the day. Sales of The Female Eunuch began slowly in 1970, but by the end of 1971 the striking latex torso of the paperback edition seemed to be on every station bookstall in the country. The book’s purpose was to call for sexual liberation by delivering a coruscating attack on the way in which women held themselves in thrall to what they thought men wanted. Its author, a 31-year-old Australian, was every bit as outrageously outspoken and passionately body-conscious as her predecessor in what one might call the Virtual Chair of Radiant Womanhood—and just as bonny a fighter.

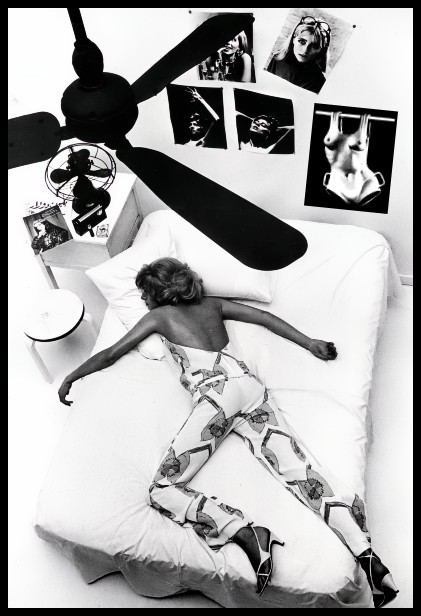

Helmut Newton, Vogue, 1966

Altered image: ‘Intrusion of The Female Eunuch’

Where did Germaine Greer come from intellectually? Born in 1939, she escaped as soon as she could from her family home in Melbourne, and went to Sydney University to write an MA on Lord Byron and enjoy a wild life with the free-living, free-loving counter-culture group known as Push. In 1964 she went to the Leavisite Cambridge Faculty of English to do a PhD on Love and Marriage in Shakespeare. From the point of view of myself and my cocoa-sipping friends in Newnham, she and Clive James between them were the swinging 60s. She pranced around the stage of the Footlights dressed only in a Union Jack, she became co-editor of the pornographic magazine Suck; she boasted not just of jettisoning her bra but of wearing no panties. Six years later, as a lecturer at Warwick University, she produced The Female Eunuch, a book as remarkable for its range of literary, philosophical and political reference as for its sexual politics. Within two years her name was synonymous with Women’s Liberation.

Helmut Newton, Queen, 1966

Altered image: ‘Intrusion of The Female Eunuch’

Since then, Greer has confounded her supporters and delighted her critics by repeatedly reneging on the cause she once epitomized. Having roused women to live a man’s life in The Female Eunuch, reinforcing her message with erudition and style in the dreadful warnings of The Obstacle Race (1981), the story of Mozart’s lost sister and other female geniuses domesticated into extinction, she went sour, disagreeing with everybody. In Sex and Destiny (1984), she remapped Western womanhood and modern contraception methods as a disaster area and glorified Third-World-style extended families. In Daddy, We Hardly Knew You (1990) she explored her thwarted desire for her father’s approval and inability to get on with her mother in painfully personal terms.

Helmut Newton, Vogue, 1966

Altered image: ‘Intrusion of Daddy, We Hardly Knew You’

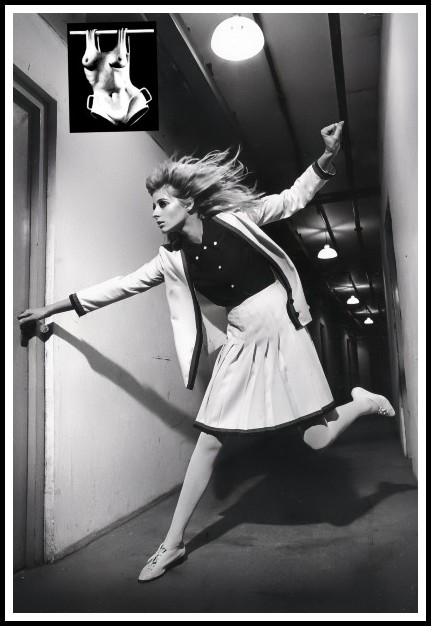

In The Change (1991) she announced that sex was overrated, and claimed that she got more joy in the tiny compass of seeing a chrysalis transformed into a butterfly than she ever had in bed with a man. In Slipshod Sibyls (1995) she dismissed all women poets before 1800 as second-rate. Now sixty, she has just published The Whole Woman (1999), a pessimistic diatribe constructed from media horror stories that bears as much resemblance to the average family’s experience as Hieronymus Bosch’s vision of Hell. Its bent is profoundly reactionary. The Sunday Telegraph headlined its appraisal of it as ‘The Female Enoch [Powell]’. But was Greer ever a genuine revolutionary? ‘I am a woman of the 50s, I wait to be asked,’ she said in an interview in You magazine in 1989. Yes, 1989. ‘I have an unusual amount of emotional insecurity. There have been complaints that I very seldom make advances, even in a relationship. Men have to court me and make the running. I have never rung a man up in my life. I realise how absurd that is.’

Man and Woman in Bed | Lady with a Flower Head | Butterfly in a Chrysalis

Marie Stopes, on the other hand, was quick to take the initiative and constantly insisted that the men in her life danced to her tune. She even offered to write a letter for her proposed second husband Humphrey Roe, breaking off his earlier engagement to another girl. In her fifties, deprived of sexual fulfilment by Roe’s latter-day impotence, she dictated an agreement for him to sign, which condoned the lovers she intended to enjoy from then on. It has to be said that Stopes did not publicize details such as these in the way that Germaine has done. But both might fairly be described as obsessed with sexuality, very definitely men’s women. Both expressed their admiration of splendid male physiques and were often derogatory about other women. Both dressed with dashing eccentricity. Both women remained remarkably attractive as they grew older, and succeeded in maintaining lifelong friendships with some of their former lovers. But there is a highly significant difference between them. Greer, rarely without an obscenity on her lips, talks of sex with a disgust worthy of Mrs Grundy. Stopes’s writing, radiantly euphemistic, holds it transcendentally joyful. Greer is a Snow Queen, her vision forever marred by some internal splinter of glass that makes the world seem implacably hostile. Stopes is Cinderella’s fairy god-mother, egging Western girlhood on to trust themselves to the rapturous embrace of their Prince Charmings.

Richard Avedon, Jean Shrimpton, 1970 | Frances Mclaughlin, Broadway, 1953 | James Moore, Harper’s Bazaar, 1965

Was this contrast an effect of childhood experience? Both Marie and Germaine were oldest daughters. Both were deeply involved with their fathers and virtually at war with their mothers. Through childhood, each operated in a troika situation, an unholy competitive trinity of father, daughter and mother. Not that they were only children. Marie had one younger sister who was, perhaps tactically, a chronic invalid. Germaine had two much younger siblings, a sister and a brother, whom her parents found it easier to get along with. Stopes won her battle for paternal attention, if there can be winners in such a game, hence her unshakeable confidence in the ideal mate. Judging by what she says in Daddy, Greer seems to think she lost hers. Hence, perhaps, her deep-rooted distrust of such a notion.

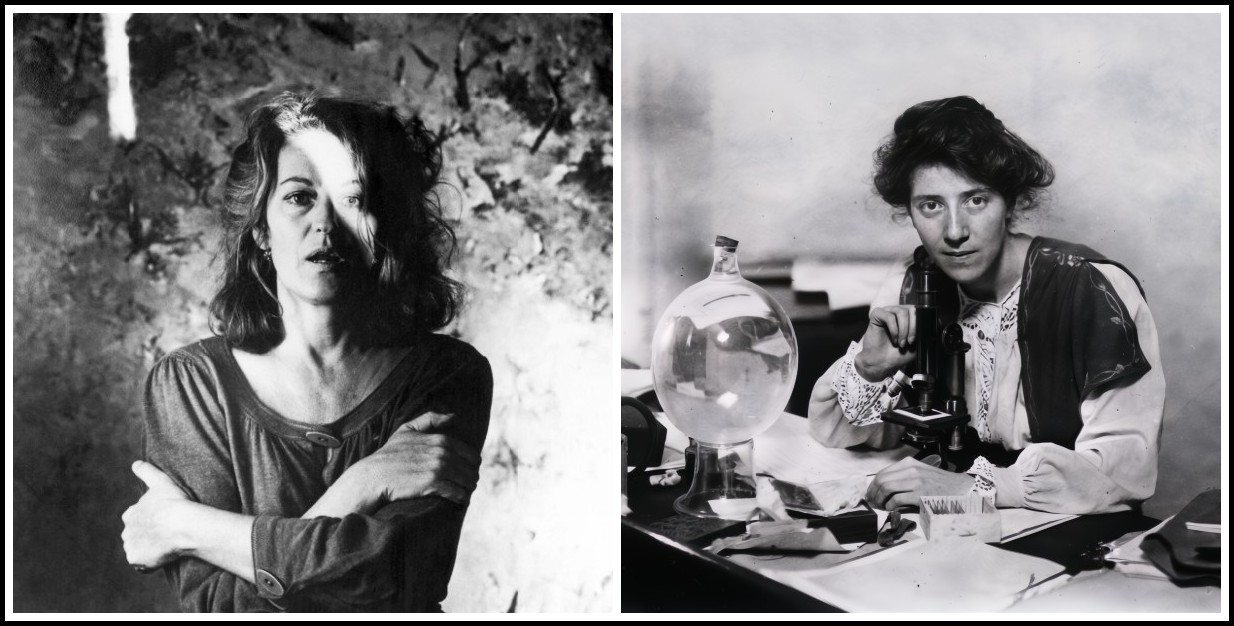

Sandra Lousada, Germaine Greer, 1970 | Marie Stopes

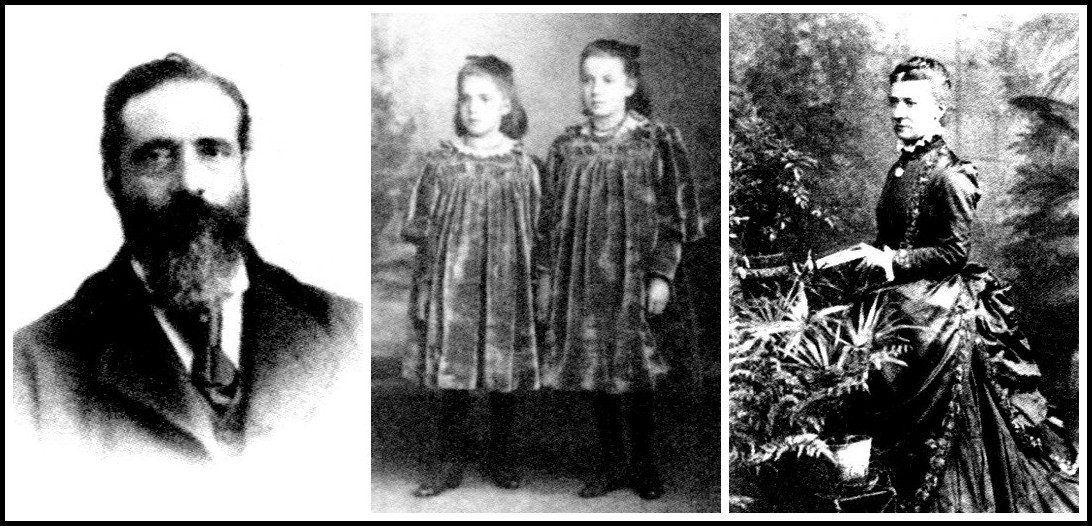

Both daughters felt their mothers to be as dominant as the mythic witch Baba-Yaga. Marie’s mother, Charlotte Carmichael, born in 1841, had to earn her own living as a governess after the death of her father when she was thirteen. Undaunted and self-directed, she was the first woman in Scotland to get the certificates of education to MA standard. Her intellectual interests ranged from Shakespeare to experimental physics—she met Henry Stopes at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1876. She was then thirty-five, a fundamentalist Protestant of ancient Scottish lineage. He was twenty-four, thoughtful, intense, and hiding his youth behind a luxuriant beard and moustache. A Quaker from a wealthy brewing family, he was a keen amateur archaeologist and paleontologist. Maybe their shared disapproval of the potentially atheistic implications of Darwin’s theories brought them together, maybe Henry’s money spelt security for the fatherless Charlotte.

Henry Stopes, Marie’s father | Winnie & Marie Stopes, sisters | Charlotte Carmichael Stopes, Marie’s mother

They married three years later, and Marie was conceived early on the six-month honeymoon they spent exploring archaeological sites in Italy, Egypt and Palestine. Cracks in the marriage were already apparent by the time they returned to England. Charlotte disliked the incessant domestic interruptions to her studies. ‘I can’t read, let alone write books,’ she complained. Although a second daughter appeared in 1884, when she was forty-three, sexual relations between the couple had evidently by then become rare. ‘Dearest,’ ran a pleading letter from Henry in 1886, when Charlotte was away on a seaside holiday with the little girls, ‘will you not put from you the teachings of your splendid brain and look only into the depths of your heart and see if you can but find there the love that every woman should hold for the father of her babies? We would put from us the seven blank years that ended and commence the truer honeymoon.’

Marie Stopes

How aware of all this was their daughter Marie? Browsing through Marriage in Our Times, a potboiler she wrote fifty years later in 1935, I found this passage: ‘I remember my father saying that his father used to say that the marriage bed should be seven feet square!’ She then recalls the wonderful atmosphere of her parents’ four-poster when she was tiny. It was succeeded by a brass bedstead from Maples. Or were there two? Was there some connected train of thought that led to the next passage: Though of course the twin bedstead was used long before I came into the world, its recent widespread invasion of the home is one of the features of marriage to-day. The twin bedstead, each bed narrow, each bed covered with sheets and blankets of ‘single bed size’, is one of the enemies of true marriage. It gives a false pretence of nearness in union which is a travesty. Its narrowness creates cold draughts at a time when warm comfort and space is vital. It secures the ever-present sense of intrusion when real solitude is desired. It enforces continual proximity and deadens feelings, without that intimate and close contact which rests, soothes and invigorates. Marriage to-day would do well to go back to the Victorian era and throne itself in a marriage bed, large and square and comfortable, attended by a single bed either in the same room or in a near-by dressing room for one or other of the partners when either desires solitude. The Victorian double bed from which there was no retreat created problems people thought to solve by the twin bedstead, but in turn the twin bedstead creates graver problems which often go unrecognised. As Marie grew older, she rather than her mother became Henry’s closest confidante. He was intensely proud of her, frequently taking her on the fossil-hunting expeditions that sowed the roots of her first career in paleobotany.

Vojtech Bruzek (background photo) | Chris von Wangenheim, Vogue, 1974 (inset photo)

How well did our other heroine’s parents get on? In 1935 Reg Greer was thirty, an established and successful seller of newspaper advertising space in Melbourne, Australia. He dressed with style, hinted mysteriously at a gentlemanly English ancestry, and spoke as if he’d been to a public school. One day he wandered out into the street at lunchtime and saw eighteen-year-old Peggy Lafrank, a milliner, with a gaggle of girl friends. His sophistication swept Peggy off her feet; she also enjoyed his evident admiration of her use of lipstick and her sassy frocks. She had abandoned her Catholic convent scholarship to try her luck in the fashion business when her mother separated from her over-possessive Italian husband. Peggy was pretty enough to be featured in at least one magazine advertisement; the odds are that Reg got the job for her. He certainly impressed Mrs Lafrank with his good manners and ‘avuncular’ care for all her children. He also had such a good job that he was a fine catch for Peggy. He took instruction in Catholicism and married her in 1937.

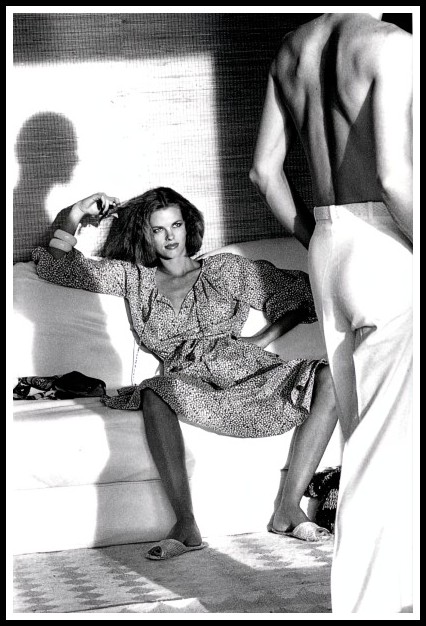

Arthur Elgort, Wendy Whitelaw, 1981

Two years later, on 29 January 1939, Germaine was born. Three years later again, Reg went to war along with thousands of other more or less willing Commonwealth volunteers. He was old enough at thirty-seven not to have been sent overseas but he elected to go (‘Did he run away from a difficult marriage and a trying three-year-old?’ asks Germaine with wistful anguish in Daddy, We Hardly Knew You). He found his way to what should have been a cushy bum-shiner job in ciphers. But months spent 80 feet underground in GHQ Malta shattered his nerves and sent him to the military hospital at Deovlali (from which the slang ‘doolally’ comes). He was discharged as suffering from anxiety syndrome. Germaine remembers going to the station with her mother in 1944, both dolled up to the nines, to meet him. Neither of them recognized the toothless wreck they found there.

Bill Silano, Vogue, 1963

But the marriage survived. Two years later Germaine’s sister was born and then her brother. They all lived together until Germaine flounced off to Melbourne University at the age of seventeen, but she seems to have felt herself to be an ugly duckling. Telling shards of her experience of early childhood are on offer in Daddy: a mother primarily concerned with perfecting her suntan and curling her hair, and who didn’t hesitate to discipline Germaine physically; a father who found it increasingly difficult to cope with his restless, brilliant, demanding daughter and seemed in constant retreat to his cronies. Was Germaine’s young mother in much the same sexually neglected boat as Marie’s father? For whose benefit were the perfect suntan, the meticulous make-up and hairdos? Germaine drops dark hints at GI dancing partners while her father was away in the war, and found the sight of her mother pencilling her eyebrows and painting her greasy red lips in a pouting bow ‘obscene’. ‘Why couldn’t I have a mother who was motherly instead of a frustrated pin-up?’ she once complained. Lipstick remains one of her bêtes noirs.

Louise Dahl-Wolfe, Claire McCardell, 1950

When she was older and stronger she came to blows with her ‘mad dog’ of a mother in the kitchen while her father shut himself away next door muttering, ‘It takes two to make a quarrel.’ Was she avenging her bruised childhood self or unconsciously defending her father’s lost honour? Did twin beds arrive from the Melbourne branch of Maples? History does not relate what measures Harry Stopes and Peggy Greer took to satisfy what seem likely to have been buoyant sexual temperaments, but it is tempting to ask how deeply their parents’ perceived behaviour affected Marie and Germaine, both of whom became flamboyant sexual spokeswomen for their generations.

Helmut Newton, French Vogue, 1981

It is easier to idealize a father if he doesn’t hang about too long. Marie Stopes’s adored father became seriously ill while she was doing her finals at University College, London. She was given her (excellent) results early so that he could know them; he died a week after seeing them. She spent as little time as possible at home with her mother and sister after this, and went to Munich to study. There she began to realize how much she had been deprived of a sense of the importance of femininity by her mother. She learned to dress more dashingly, adopting furs and short skirts. ‘There is hardly anything in the world so gloriously beautiful as a woman’s body,’ runs a passage she wrote in an unpublished autobiographical novel. ‘And while I am one, and a young one, I think it would be wickedness not to enjoy the loveliness of it.’

Gilda Grey in beaded evening dress with fox fur trim

She went to the theatre to watch Isadora Duncan wowing spellbound Munich audiences. When she went home, she wrapped herself in flimsy voiles and imitated Isadora’s highly erotic dancing. But at this time she went no further. Most of her relationships were with older men, professors to whom she could relate in a filial way. She was, she wrote of herself later, ‘a child in a woman’s body’. But her father’s early death had allowed her to write her own script. She could abandon his strait-laced family code and enjoy her intense physicality without losing the evergreen memory of his admiration.

Bert Stern, Vogue, 1961

At the same sort of age, Germaine’s relationship with her father was very different. He was all too real: adored but in her eyes infuriatingly unresponsive. In a violent reaction, she decided not to act as the sort of woman he would have admired but as a female version of the brilliant, aggressively masculine man she thought he ought to be. It was all too evident on the rare times they met that he simply did not know what to make of her; was in fact intensely nervous of her. When he died in 1983, she was chilled that he had chosen not to mention her in his will. It was to cope with her sense of being rejected by him that, attracted by the romantic hints of noble ancestry he used to throw out, she decided to dig into the past to find early family faces to whom she could perhaps relate better. It was a disillusioning experience. It emerged that Reg was in fact the illegitimate son of a housemaid seduced by a local businessman. His real name was not even Greer, but Greeney. Daddy is full of intense longing for kinship, but Greer does not seem to perceive its implications: perhaps only her looks are her father’s; her energy and moral dynamism, her inclination towards Mediterranean-style extended families must all come from her much despised mother’s healthily mongrel ancestry: part Italian, part Irish and part Danish.

Art Kane, Vogue, 1962

FOUR

So much for the genesis of our heroines’ obsessions. How did they learn to universalize them so tellingly? Both women were ambitious, outstandingly intelligent and intensely moral girls. Religion had a high profile in their upbringings: regular attendance at Presbyterian and Quaker services for Marie; a convent education from the age of four for Germaine. Although both disengaged themselves from conventional religious observances rapidly, each retained a habit of morality coupled with a deep sense of mission. Marie’s mother, a committed early feminist, sent her to North London Collegiate, the most forward-looking girls’ school in the country. Marie outdid her mother’s scholastic achievement by becoming the first woman to read science at University College, taking her honours degree—with distinction—in only two years instead of three.

Chris von Wangenheim, 1976

Germaine has put on record how much she enjoyed her long convent education, dismissing the family home as a cultural desert. Her maternal grandmother was the person who first took her to the Art Gallery in Victoria; perhaps she also introduced her to the public library in the same building, the ‘Valhalla’ to which Germaine made repeated pilgrimages in her youth. ‘More of my waking life has been spent in libraries than anywhere else,’ she tells us in Daddy in a rare moment of serenity. ‘Libraries are reservoirs of strength, grace and wit, reminders of order, calm, continuity, lakes of mental energy, neither warm nor cold, light nor dark. The pleasure they give is steady, unorgiastic, reliable, deep and long-lasting.’

Guzel Maksutova | Bruce Weber | Leon Seibert

By the age of twelve she had begun to formulate an ambition to go to university and be an intellectual. The nuns had given her a social conscience. They also spotted the potential of her singing voice, and introduced her to music, a lasting love. What the convent did not prepare her for was the unromantically sudden approach of Melbourne boys to dating. ‘I waited a year for romance, then gave up, as I realised I was considered a tease’ was the way she explained her first sexual experiences to an interviewer from Today in 1989. She became more laddish than the lads, suffered for it, swallowed hard and continued to try to outdo them at their own game. Talking later of the wild years that followed in Sydney, she acknowledged the role played by her own instincts as well as that of the prevailing climate of permissiveness. Those were the rules that governed the lives of many who are now seen as the apostles of permissiveness. Utter honesty, no jealousy or possessiveness, no sexual game playing, no bra, no cosmetic aids, no bullshit. Yet anyone who paid any attention to me when I was two years old would have seen it coming. The nuns used to say, You’ll be a great saint or a great sinner. I chose sin because it seemed more straightforward. And if God doesn’t like it, he can lump it.

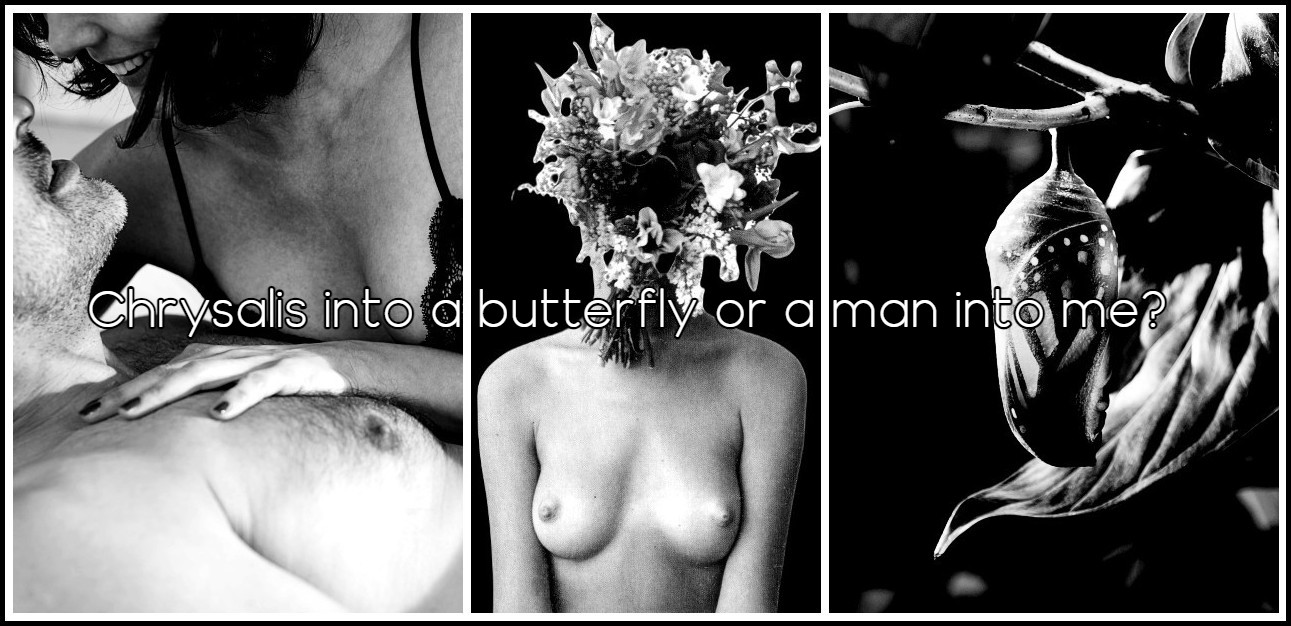

Bruce Weber, Coffee Shop, 1987

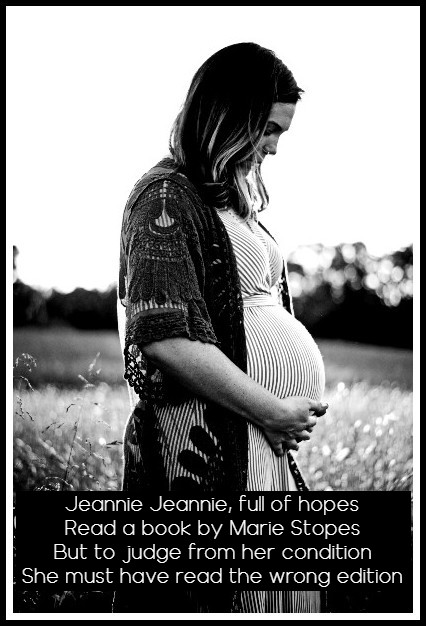

Once they were sexually active, contraception became a key issue in the lives of both women. In this context, it is Stopes who was both more radical and more rational. Wise Parenthood (1918) was a useful guide to what limited contraceptive techniques were then available. It was also far from reliable. In her own book on the subject, Greer ridicules Marie Stopes for getting caps muddled with diaphragms. She was right about Stopes’s blunders. A 1920s playground skipping rhyme ran (see text on image):

Photo: Devon Divine, Unsplash

But Sex and Destiny was a very different kind of book from either Wise Parenthood or Stopes’s follow-up history, Contraception: Its Theory, History and Practice (1923). Its condemnation of sexploitation reflected Greer’s realization of the damage her gynecological history had dealt her chance of having the child that she had jauntily announced she was ready to create at the age of thirty-seven. A panoramic sweep across the history and anthropology of contraception, it concludes that chemical and mechanical means of contraception are mixed blessings if not unmitigated evils. She also idealized Third World extended families in terms reminiscent of Margaret Mead’s thoroughly misleading Coming of Age in Samoa, and argued that the idea of population explosion was a fantasy and that Western contraceptive methods were unnecessary. She actually ended up recommending several of the same methods for achieving sexual satisfaction short of full intercourse as Stopes. Liberated women’s jaws dropped in horror at such retrograde ideas. But arguably, there is a sense of the wheel turning full circle, of Stopes’s erotically ambitious social experiment having been tried and found wanting by a stern, though no longer young, Antipodean judge. The book may also owe something to Greer’s Catholic upbringing.

Polly Borland, Germaine Greer, 1999

In mid-life, both women pursued successful academic careers in subjects quite separate from the field for which they became most famous. Stopes was a paleobotanist with a special interest in the nature of coal who had lectureships set up for her in what was then a little-explored field. Greer’s field is English literature; she has held academic posts at Tulsa, Oklahoma and at Newnham College, Cambridge. Stopes wrote to the papers frequently on all sorts of matters. She asked Lloyd George if she could lead an armed force against the striking miners. She also wrote second-rate novels and very derivative poetry. Greer’s pungent tirades on every issue imaginable are sought-after media properties. Both took to celebrity status like ducks to water. Stopes suggested to Kipling that ‘If’ should be rewritten to deal with women and invited Thomas Hardy to her Portland Bill lighthouse holiday home. Greer’s presence guarantees the success of literary parties.

Maritally, both had low boredom thresholds, though Stopes’s marriage to the always adoring and extremely long-suffering Humphrey Roe lasted in name until his death, aged seventy, in 1949. Despite the early memories of that cosy four-poster (and perhaps her own place in it), she insisted on separate bedrooms for husbands and lovers alike. Greer too has said that she prefers to sleep on her own. She has had one very short marriage, and numerous proudly flaunted affairs. Both women proclaimed the joys of maternity but found them hard to experience personally, although that did not stop them expressing very definite ideas on the upbringing of children to both their friends and the world at large. Greer has put on record her profound regret at not having a child of her own. But she has some seventeen godchildren and numerous cats. These favoured pets, together with her books, her love of and talent for teaching, her personal connections with many Third World women and children, and a succession of human and animal waifs and strays who come and go at her well-tended small-holding near Saffron Walden, all testify to her abundant maternal instinct.

Stopes had one son when she was forty-four, and named him after her father. She fostered a series of boys in a search for a companion for this second adored Harry; all were ruthlessly disciplined, found wanting and returned. But when he grew up, Harry proved to be one of the few men his mother could not dominate. She was so unpleasant about his chosen wife that after marriage Harry removed himself from her orbit almost completely, and she left him only her Oxford English Dictionary in her will.

The age of fifty found our heroines marching to very different drums. Stopes’s Enduring Passion was for mature lovers. It was frank-spoken on impotence among older, professional men. She was also one of the first people to identify the possibility of a ‘male menopause’ in her 1936 book The Change of Life in Men and Women. (H.G. Wells hotly denied the notion in a letter to her: ‘It’s a great and selling idea. But I don’t find much in the book. I am seventy. I have never been able to detect any lunar periodicity in my life although I kept a very careful private diary.’) For herself, Stopes declared that she was still ‘psychologically twenty-six’. In Greer’s own book on the menopause, The Change, written when she was fifty-two, she resigns herself (and as usual all other women) to celibacy with considerable wit and serenity. She also offers the compensation of a likeable quality called Post Menopausal Zest.

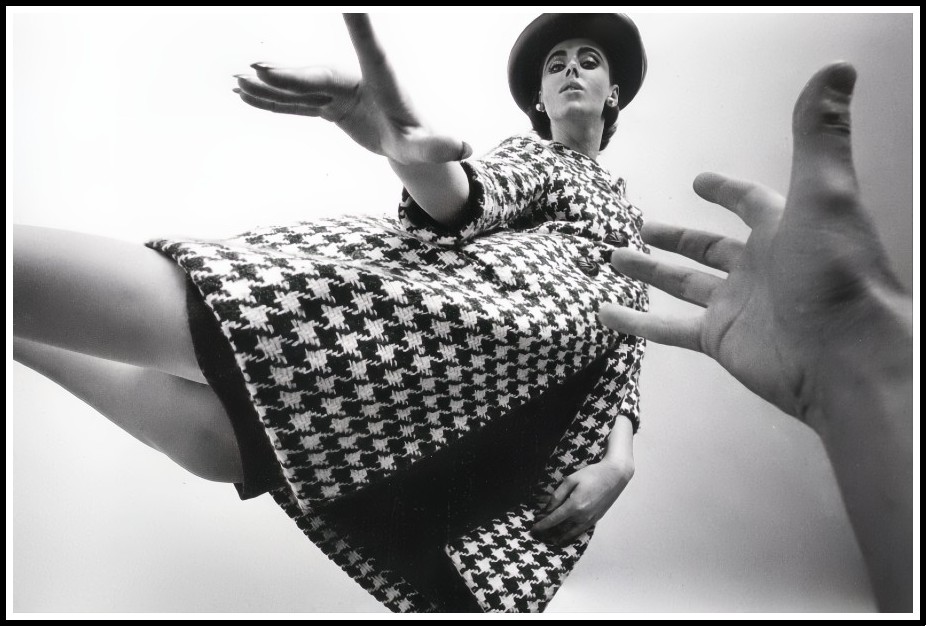

Hiro, Harper’s Bazaar, 1965

What of their final legacies? Although the Marie Stopes Clinics are at the forefront of family planning work in the Third World, Stopes herself can be seen in the long-term as no more than a courageously prominent surfer on the wave of an unstoppable movement. To some extent her jealous insistence that she and only she should control the organization of family-planning clinics actually delayed their development. Moreover, for her, contraception was merely the means to a much more important end. The greatest tribute to her impassioned advocacy of sex for sex’s sake came in 1958, two months before her death, when the Lambeth Conference she addressed so fruitlessly in 1910 changed its tune. It not only acknowledged the need for birth control but declared that, ‘The procreation of children is not the sole purpose of Christian marriage; implicit within the bond of husband and wife is the relationship of love with its sacramental expression in physical union.’ Since then a sea change in marital expectations has taken place. It is a sobering thought that, forty years on, the failure of more than one marriage in three may reflect both the accuracy of her guesstimate percentages of sexual compatibility in marriage and the extent to which many of us mistakenly adopted her demanding New Gospel of erogamy. Many of us didn’t. Authoritative British and American sex surveys in the 1990s have revealed that the majority of us rest content with a distinctly low-key love life.

Richard Avedon, Suzy Parker & Mike Nichols, 1962

Germaine Greer took a distinctly maverick line when she in turn surfed the crest of the wave of the 1960s Women’s Liberation movement. Many of the more serious-minded feminists condemned The Female Eunuch as (literally) sleeping with the enemy. But millions of women now in their fifties still give that shocking but unforgettable book the credit for shaking them out of a rut. It is impossible as yet to define the legacy for which Greer will be most famed—she’s surprised us before and no doubt will again. She is certainly growing old gracefully. She could yet single-handedly revive the tradition of respect for the sagacity of wise old women; from all accounts she could also write a better book about home-making than Constance Spry or Martha Stewart. As to her past, it is now more often pointed to as a warning than as an inspiration. Despite the current vogue for a superficial laddishness, her maverick exploration of the frontiers of sexuality discouraged more women than it converted, not least because, by her own admission, it has proved a far from fruitful experiment. The latest Hollywood heroines once again extol the value of virginity, of ‘saving yourself’ for Mr Right.

Saul Leiter, 1959 | G. P. Lynes, 1947 | Saul Leiter, 1957 | Javier Valhenrat, 2009 | Bettina Rheims, 1988 | Bettina Rheims, 1986

But arguably the life Greer lived as a young woman was also a brave and a necessary experiment; its outcome proof positive of the hollowness of Marie Stopes’s promise of never-ending ecstasy. Women today are the wiser for both women’s high-profile experiments. More independent, more tolerant, and better friends with each other, they enjoy far more stimulating and balanced relationships with men both in the workplace and the bedroom than they have in any previous century. Between the Scylla of Stopes and the Charybdis of Greer, they are slowly but surely constructing a middle way.

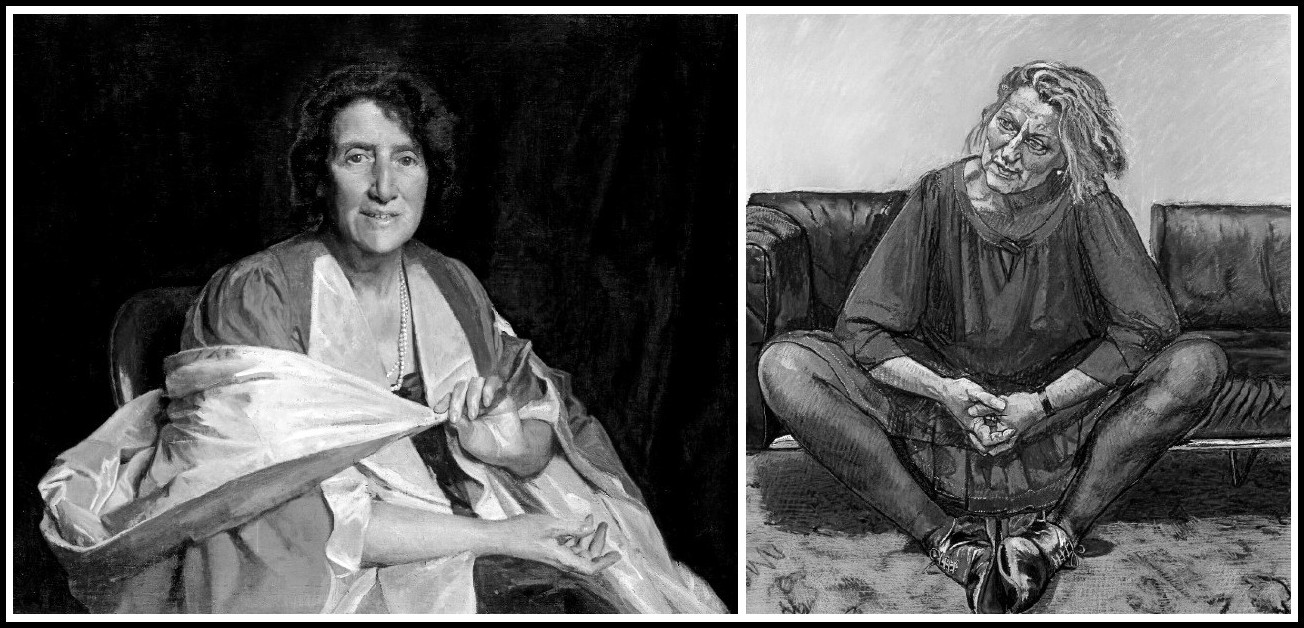

Gerald Kelly, Marie Stopes, 1953 | Paula Rego, Germaine Greer, 1995

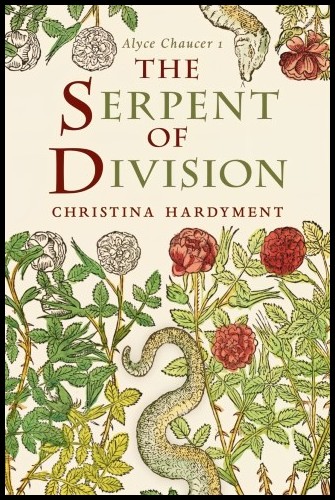

CHRISTINA HARDYMENT: THE ALYCE CHAUCER NOVELS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

CHRISTINA HARDYMENT: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments