An Experiment in Criticism

TOP TEN GUITAR SOLOS: AN ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVE

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

‘How little is needed for happiness! The note of a bagpipe. Without music life would be a mistake.’ So wrote Nietzsche in Twilight of the Idols.1 All music lovers, whether adept instrumentalists, gifted composers or simply responsive listeners know exactly what Nietzsche means. I assume, dear reader, that you like I are a music lover. Let this shared passion suffice to justify the experiment in criticism I propose: to what extent can I, neither a musician nor a musicologist, ignorant of both music theory and guitar technology, legitimately select and comment on ‘top ten guitar solos’? Selecting is easy—it’s the commentary that’s difficult. Indeed, in music form and content are one—form is content— so without the ability to analyze form (make a musicological analysis), what is there to ‘hang one’s hat on’? Strictly speaking, nothing. So why do I insist on conducting this experiment? What might I have to offer you, dear reader? Well, whenever possible, I will ‘hang my hat’ on extracts from interviews with guitar players, as well as on a text by John Perry (the Only Ones) on the art of the guitar solo. For the rest, I trust my responsive heart and mind to compensate for my uneducated ear. If, at the end of this post, your pleasure in the music I discuss is enhanced, then I’ll consider the experiment to have been worthwhile. Are you ready? Let’s go!

1 – Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols. Number 33 in the ‘Maxims and Arrows’ section. (London: Penguin Books, 1990) p. 36

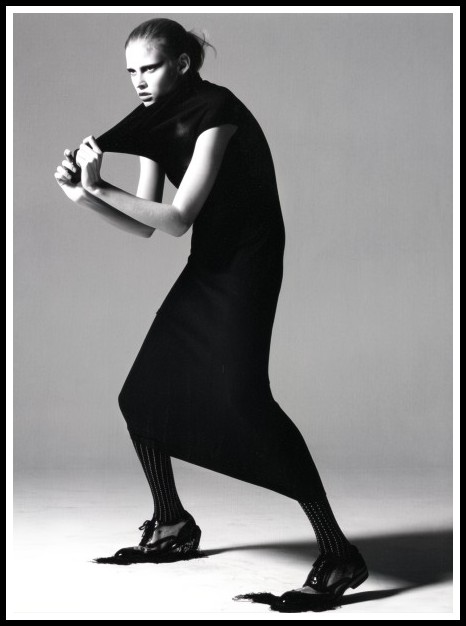

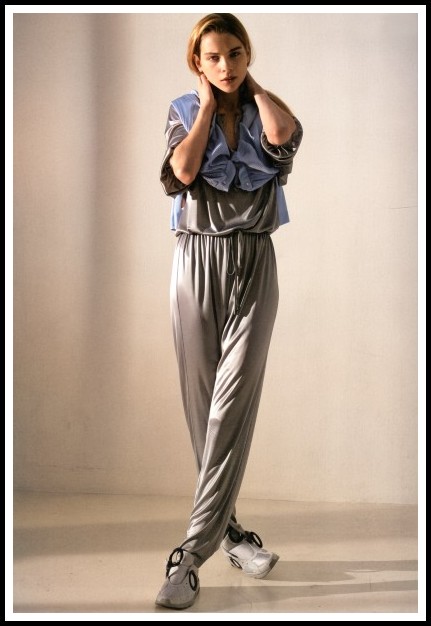

Yohji Yamamoto, Stella Tennant | Thomas Schenk, 2001

INTRODUCTION: THE ART OF THE GUITAR SOLO – EIGHT POINTS OF VIEW

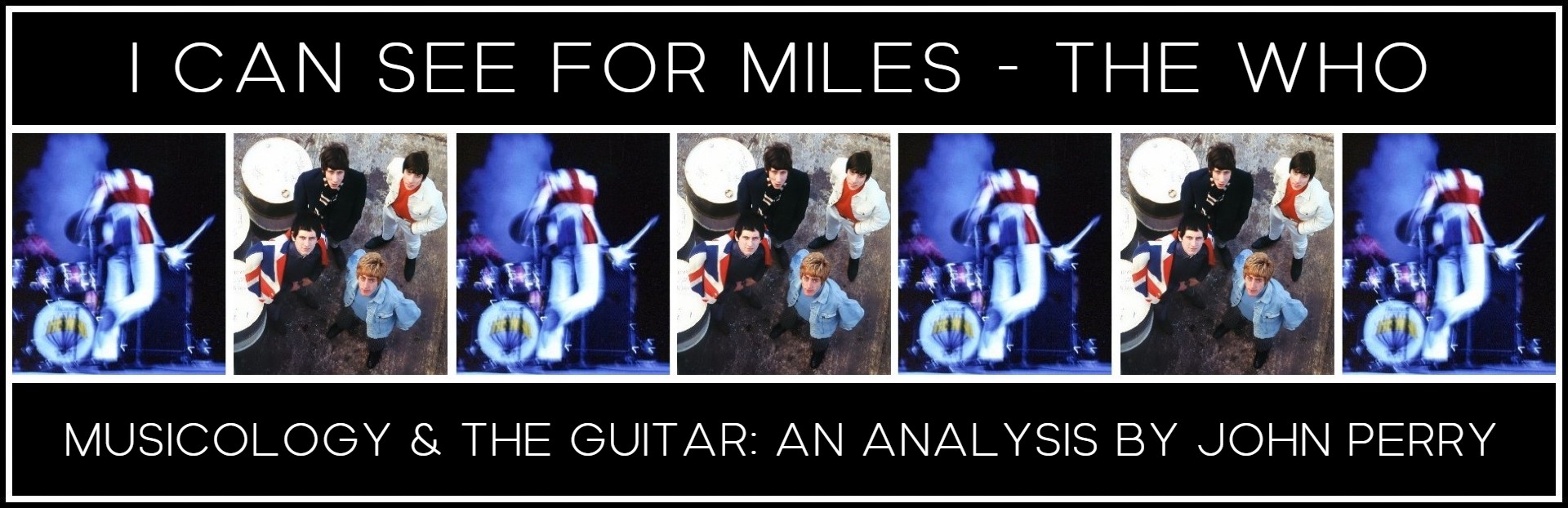

1. JOHN PERRY (THE ONLY ONES)

Source: Abbreviated from John Perry, ‘The Top Ten Guitar Solos’,1 The Sunday Times, 19 August 2007

There are few sounds in rock to rival a great guitar player hitting his stride. Power, melody, the tension between attack and delicacy–all these separate the real players from that vast band of also-rans. Let’s define terms. The solo exists to break up the typical verse-chorus-verse-chorus structure of songs from every genre of popular music. A well-turned guitar phrase can form a song’s principal hook (as in ‘Satisfaction’).

1 – Here is John Perry’s top ten:

– Robby Krieger, Moonlight Drive – The Doors, Strange Days, 1967

– Mick Taylor, Love in Vain (live) – The Rolling Stones, Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out, 1969

– Jerry Miller, Omaha / Hey Grandma – Moby Grape, 1967

– Alex Chilton, Bangkok, 1978

– Eddie Phillips, Painter Man – The Creation, 1966

– Jimi Hendrix, Drifting – First Rays of the New Rising Sun, 1966

– Pete Townshend, I Can See for Miles, 1967 / Neil Young, Cinnamon Girl – Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, 1969

– Hubert Sumlin, You’ll Be Mine – Howlin’ Wolf, 1961

– Bert Jansch, Chambertin – The River Sessions, 1974

– Scotty Moore, I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone – Elvis Presley, 1955

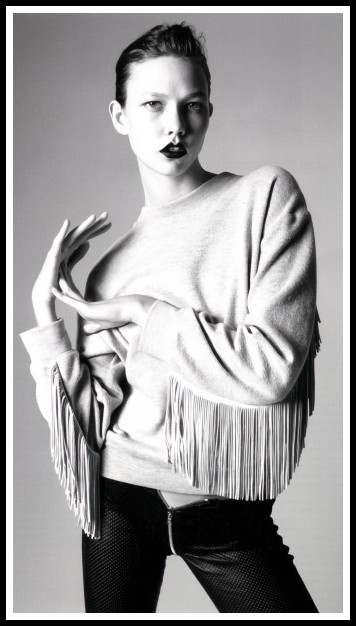

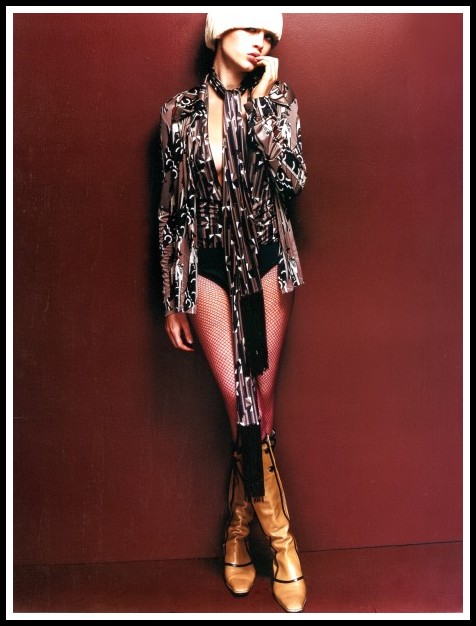

Nicolas Ghesquière, Kate Moss | Craig McDean, 2002

What makes a great soloist? Technical virtuosity is not enough. Top jazz-rock and fusion players have amazing facility, but all too often nothing to say. Theirs is the musical equivalent of juggling seven balls while balancing a chair on your nose. It’s impressive in its way, but nothing that moves the heart; ultimately, it is just glib. Great guitar-playing bypasses the intellect and connects straight to the soul. The fusion wizards can’t be dismissed as unaccomplished, but their style is ‘like developing one tiny part of a person and calling it a whole human being’.1 Classical guitarists such as Julian Bream have great virtuosity, but their technique is transparent. It serves the music, and that is the vital distinction—the precise opposite of the jugglers we have just been discussing. Whenever technique becomes an end rather than a means, there is aesthetic trouble ahead. After punk made ignorance a virtue—so long as the result was exciting—a reaction was inevitable and, spurred on by the emergence of MTV, the 1980s made a cult out of pure technique (and big hair). Private guitar ‘institutes’ flourished, teaching speed-guitar techniques. The schools churned out lightning-fast young wizards with precocious facility and nothing to express.

1 – To paraphrase the baffled priest preparing Rex Mottram in Brideshead Revisited.

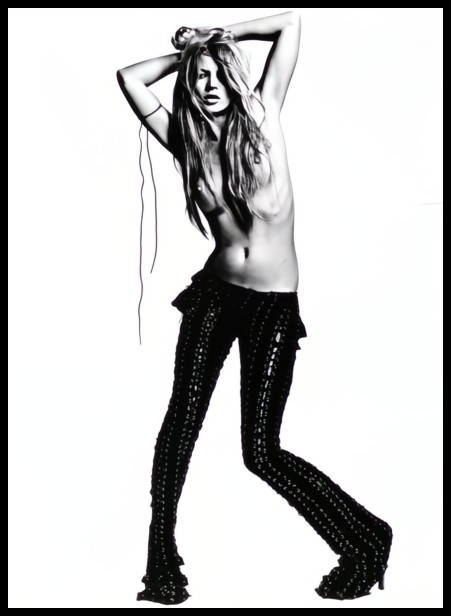

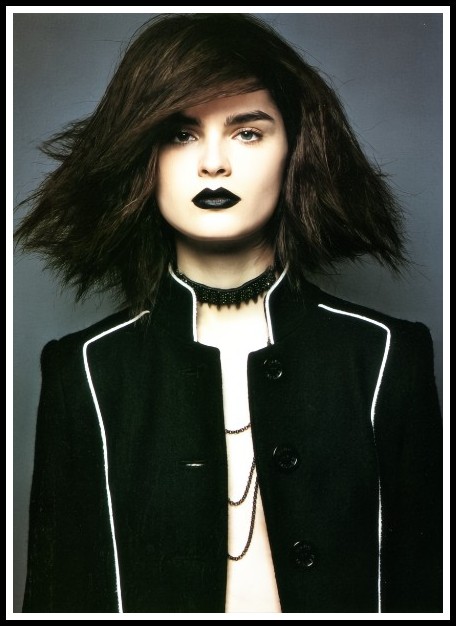

Giorgio Armani, Erin Wasson | Willy Vanderperre, 2004

So, what’s going on in a solo? The interplay of two main elements: melody, meaning the notes selected and the order in which they are placed (the tune) and rhythm, meaning the length of each note and of the intervening gaps (phrasing). I emphasize the gaps, since it’s not what you play so much as what you leave unplayed that speaks loudest. The soloist with no feel for rhythm is less likely to create a satisfying, completed structure and is more prone to meaningless ‘widdling’—widdley, widdley, widdley—the stock phrase of the classic guitar cliché: fast triplets. Compare Keith Richards’s simple but perfect solo on ‘Gimme Shelter’ with almost anything from the blues-boomers of the year 1969. Jimi Hendrix had a point when he asked Eric Clapton, ‘Man, how come you can’t play rhythm guitar?’. To invert the popular wisdom, Hendrix was a supreme rhythm guitarist who happened to play exquisite lead guitar. In any case, his work often disposes of the distinction between lead and rhythm.

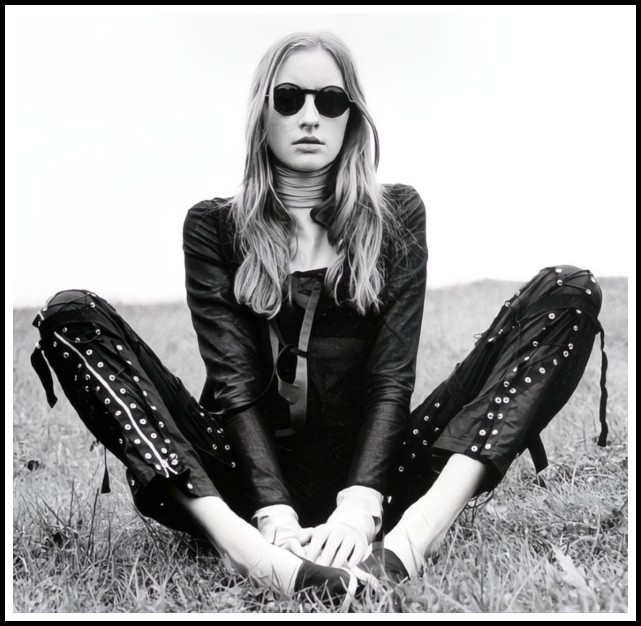

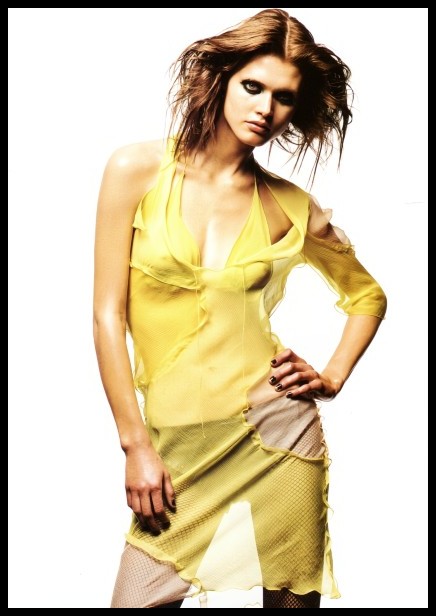

Junya Watanabe, Anja Rubik | David Vasiljevic, 2008

2. ANDY SUMMERS

Source: June 2007 interview, The Guitar Player Book, Michael Molenda, editor (London: Backbeat Books, 2007) p. 81

Any good solo takes the essence of the song, encapsulates its spirit, and then raises the whole thing to another level. It’s also important to twist the song slightly and throw in a few piquant notes to catch people’s ears—it’s like throwing a spice into a soup. Suddenly, there’s another flavor, a different color. I grew up with the giants. People like Monk and Mingus were always in my head, and they were intensely difficult for me to grasp when I was young. I could typically rip off a Wes Montgomery solo without any problem, but to play like Mingus and Thelonious Monk was something else altogether. There was a wonderful abstraction in their music—both in note choices and phrasing. The time thing in jazz phrasing is really where it’s at—playing away from the time, playing out of the time, and playing across the bar lines. You almost don’t know where they are, and yet they still come out right where they’re supposed to be. To me, timing is what ultimately determines how good a player is going to become. Anyone can learn about playing scales over chords, but the ability to twist and bend time is the mark of a great player.

Alexander Wang, Missy Rayder | Daniel Jackson, 2009

3. NEIL YOUNG

Source: March 1992 interview, The Guitar Player Book, Michael Molenda, editor (London: Backbeat Books, 2007) p. 98

Elevation. You can feel it. That’s all I’m looking for in a solo. You can tell I don’t care about bad notes. I listen for the whole band on my solos. You can call it a solo, because that’s a good way to describe it, but it’s really an instrumental. It’s the whole band that’s playing. It doesn’t matter if you can play a scale. It doesn’t matter if your technique is good. If you have feelings you want to get out through music, that’s what matters. If you have the ability to express yourself, and you feel good when you do it, then that’s why you do it. The technical side of it is a complete boring drag, as far as I’m concerned. I mean, I can’t play fast. I don’t even know the scales. A lot of the notes I go for are notes that I know aren’t there. They’re just not there, so you can hit any note. I’m just on another level as far as all that goes. I appreciate these guys who play great. I’m impressed by metal bands with their scale guys. I mean, Joe Satriani and Eddie Van Halen are genius guitar players. They’re unbelievable musicians of the highest caliber. But I can’t relate to it. One note is enough.

Riccardo Tisci, Suvi Kaponen | David Vasiljevic, 2009

4. THE EDGE

Source: June 1985 interview, The Guitar Player Book, Michael Molenda, editor (London: Backbeat Books, 2007) p. 82

I’ve never really had any guitar heroes. All of the guitarists that I’ve liked have been total antihero stuff. I think of Neil Young—that guy gets so much feeling into his playing, but he’s stumbling around a few notes. It means so much, but it’s so simple and basic. Tom Verlaine was never an incredible virtuoso, yet he revolutionized guitar playing. He suddenly said, ‘Look, you can do something different. You don’t have to do the same thing. This is nothing like anything you’ve heard before.’ U2 has never put up with anything that lacked that vitality, that originality. We’ve always changed it if we felt it smacks of an era gone by or that it isn’t musically relevant.

Ann Demeulemeester, Natasa Vojnovic | Tesh, 2001

5. PETE TOWNSHEND

Source: May 1972 interview, The Guitar Player Book, Michael Molenda, editor (London: Backbeat Books, 2007) p. 84

I started out as a rhythm player, and a few of my lead licks are things I’ve basically developed in recording sessions. I’ll never be able to play the kind of leads I want. I was happiest listening to Jimi Hendrix—that, to me, was heaven. For me, it was probably a good thing that he died, because it made me realize that I wasn’t going to be at any more Jimi Hendrix concerts and feel that bit of downfall. I was going to have to try and do it for myself again.

Yohji Yamamoto, Lara Stone | Daniel Jackson, 2007

6. EARL SLICK

Source: Guitar Player Presents 50 Unsung Heroes of the Guitar (London: Backbeat Books, 2011) p. 182

I’ve gotten very inspired by playing within song structures rather than soloing over them. This is probably due to the fact that I understand song forms better because I’ve been writing more myself. And—believe me—I am sick and tired of the chops thing! Playing with David Bowie in the 1970s, it was about not staying too close to the structure and doing lots of soloing. Nowadays [2004], I’m more apt to cop some stock parts. I’ll still add my edge to those parts—and I do all the rhythm stuff my own way—but I’m playing a lot less of the dramatic solos. I’m doing stuff like catching two strings and hitting them for the entire solo. Anything I’m doing is still aggressive, but there are a lot fewer notes. I’m playing a lot more with my sound than I am with my chops.

Alexander Wang, Karlie Kloss | Daniel Jackson, 2009

7. KEITH RICHARDS

Source: November 1977 interview, The Guitar Player Book, Michael Molenda, editor (London: Backbeat Books, 2007) p. 74

You can’t go into a shop and ask for a ‘lead guitar’. You’re a guitar player, and you play a guitar. What’s interesting about rock ’n’ roll for me is that if there are two guitarists, and they’re playing well together and they really gel, there seems to be infinite possibilities open. It comes to the point where you’re not conscious anymore of who’s doing what—it’s not at all a split thing. It’s like two instruments becoming one sound. It’s never been the technique thing with me. I’ll never be a George Benson or a John McLaughlin, and I’ve never tried to be. I’ve been more interested in creating sounds and something that has a real atmosphere and feel to it.

Tom Ford, Kate Moss | Craig McDean, 2002

8. A COMMENTARY ON THE INTERVIEW EXTRACTS

Running through these interview extracts is the question of the relative weight to be given to technique versus feeling in making music on a guitar. Theoretically, it’s a false question, since virtuosity can serve musicality, as is evident in classical music. In rock music, however—to judge by the cited guitarists’ comments—it would seem that artistically, virtuosity is often more vacuous than fulfilling, more sterile than fruitful. Why should this be the case? My guess is that in order for craft to become art it must confront constraint and disrupt the given. Virtuosity implies reduced constraint and compliance with the given. A virtuoso guitarist, then, if they aspire to be an artist, needs a ‘hygiene of living’ that enables them to ‘wake to wonder’ rather than to ‘conform to the crowd’. In the same way that the opposite of stupidity is not intelligence but humility, the opposite of virtuosity is not limited technique but risk-taking and exploration. The lives of David Bowie, Tom Verlaine, and Leonard Cohen, for example, all exemplified this: their creativity arose organically from their ‘hygiene of living’, as did their ‘attitude’, ‘personality’ and ‘feeling’. This meant they had ‘something to say’—music as a progress report from a life being truly lived—and that ‘something’, however humble, was, almost always, compelling. And that is why, dear reader, in my ‘top ten guitar solos’, you will find names other than those that invariably populate such lists.

Hussein Chalayan | Paul Wetherell, 2002

TOP TEN GUITAR SOLOS

Note: This list is not a ranking. Instead, I’ve sequenced the songs in terms of complementarity and contrast.

1. John Perry, ‘In Betweens’ – The Only Ones, Even Serpents Shine, 1979

When asked in an interview to name his influences as a guitar player, John Perry answered: The obvious ones to anyone born in 1952. Hank Marvin [The Shadows], because to begin with he was the only guitar player we saw. Then along came Townshend and Hendrix and Jeff Beck, and a whole different way of using volume and attack. Peter Green for his delicacy. Robbie Krieger from the Doors, for the beautiful way he had of painting pictures with a song instead of just playing blues guitar. Later on I started listening to horn players, Coltrane and Pharoah Saunders both played in a way that could be adapted to the guitar. The country pianist Floyd Cramer had a way of phrasing the major scale that he’d taken from pedal steel. I copied that and adapted it to guitar. The American West Coast bands as a whole were doing interesting stuff. Jorma Kaukonon’s playing on the song ‘Good Shepherd’1 still sends a shiver down my spine. Bert Jansch. Davy Graham. Keith’s playing as a rhythm guitarist at the very heart of any song is an abiding influence. Richards does that as well as it’s possible to do. I could go on for ages, but that’s enough to give you an idea. When punk happened, they weren’t influences, but I thought X-Ray Spex made fantastic, original records. Listen to any Only Ones song and you will hear how effectively John Perry has assimilated these influences and forged a singular identity as a guitarist.

1 – The Jefferson Airplane, Volunteers, 1969

Nicolas Ghesquière, Linda Evangelista | Paolo Roversi, 2004

Both the tone and the rhythm of ‘In Betweens’ are governed by the singer’s delivery of the lyric, ‘dark and slow like molasses, yet somehow luminous’. The vocal feels like it’s welling up ‘from some deep subterranean source’,1 at once chthonic and majestic, qualities John Perry’s lead guitar reflects in the brief solos between the verses. And then, at the 2:40 mark, the tempo begins its accelerando as the lead guitar embarks on its outro solo. Highly melodic, at once raw and refined, the guitar sings silvery notes dipped in vitriol: it has a rage and glory akin to that in Mick Taylor’s ‘Heartbreaker’ solo. Effortlessly fluid, it is no less rock ‘n’ roll for being elegant. At the 3:10 mark, the guitarist reverts to hitting chords as rhythm guitar, bass and drums take the accelerando through a series of crescendos before a final lead guitar figure comes to close out the piece. Transposed to painting, the song evokes, for me, the Symbolist imagery of Gustave Moreau: primitive yet sophisticated, mythic and timeless yet here and now. Of the influences John Perry mentioned, I note the Robby Krieger-like ‘painting pictures’ in the ‘seagull cries’ that Perry coaxes out of his guitar as he evokes the sea, as well as the ‘delicacy’ of Peter Green as Perry picks his notes. Other outstanding solos abound in the Only Ones repertoire; if you’d like to hear more, listen, in particular, to ‘Another Girl, Another Planet’, ‘Miles from Nowhere’, and ‘The Big Sleep’.

1 – This and the previous quote are from Richard Jonathan, ‘The Only Ones, or the Elusive Scent of Commercial Success’

Caught between right and wrong

Tell me, is there no escaping?

I just can’t go on

Living from day to day

Sometimes when I wake up

Feel like I never woke up at all

Sordid clandestine love

It burns your heart out

Try to fix up an hour

In the back seat

Get to know each other

Can’t you wait till the evening

When the stars are shinning bright?

There’s no-one around

Who could cause any danger

Who else but you

Would stay with me baby?

Ships out at sea

Oh to be free

Just like a sailor at sea

In the middle of the sea

Marc Jacobs, Iris Strubegger | Daniel Jackson, 2009

2. John McGeoch, ‘Shot by Both Sides’ – Magazine, Real Life, 1978

‘Shot by Both Sides’ impresses by the sheer conviction of its presence: guitar and drums, at once underpinned and propelled by a relentlessly driving bass, send sounds racing along a highwire fuse where, emitting sparks, they self-consume as they explode. The nerves and blood of the notes come from John McGeoch’s guitar. Imbued with the urgency of an ambulance racing to the scene of an accident, they mirror the mind of the singer caught in the crossfire. He is an outsider indifferent to both warring parties, seeking only to preserve his private space: a fine metaphor of the predicament of the artist struggling to safeguard his singularity in a sea of conformism.1 ‘Shot by Both Sides’ distills the spirit of rock through the filter of Altamont, not Woodstock. It is one of the finest examples of what rock is capable of when sensibility, intelligence and technique fall into a favorable configuration. That both Magazine and the Only Ones have fewer than 150,000 monthly listeners on Spotify while absolute mediocrities have millions reminds us how difficult it can be for the ‘ethics of the artist’ and the ‘amorality of the audience’ to confront each other fruitfully.2 John McGeoch, fed up that, after three albums, Magazine had failed to find a viable audience, left to join Siouxsie and the Banshees.3 ‘Shot by Both Sides’ remains to remind us of the compelling musicality of his guitar playing with Magazine: his solo, bringing the energy of the song to a peak, propels it into the sublime.4

1 – This relates to the notion of ‘hygiene of living’ I discussed earlier.

2 – Again, David Bowie is the finest example of a fruitful confrontation between the ‘ethics of the artist’ and the ‘amorality of the audience’. I am tempted to call on Mathew 7:6 KJV here—Give not that which is holy unto the dogs, neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet, and turn again and rend you—but Bowie is there to remind me that the artist, by definition, is ‘Outside’. Cf. ‘On the run to the outside of everything’ in ‘Shot by Both Sides’.

3 – Where his singularity found a counterpart in Siouxsie’s individuality, enabling him to produce some of the finest guitar work on record.

4 – See Adrian Woodward’s post on his ‘Anyone Can Play Guitar’ blog for a magnificent demonstration of what John McGeogh is doing on ‘Shot by Both Sides’.

This and that, they must be the same

What is legal is just what’s real

What I’m given to understand

Is exactly what I steal

I wormed my way into the heart of the crowd

I was shocked to find what was allowed

I didn’t lose myself in the crowd

Shot by both sides

On the run to the outside of everything

Shot by both sides

They must have come to a secret understanding

New offenses always in my nerves

They’re taking my time by force

They all sound the same when they scream

As a matter of course

I wormed my way into the heart of the crowd

I was shocked to find what was allowed

I didn’t lose myself in the crowd

Shot by both sides

On the run to the outside of everything

Shot by both sides

They must have come to a secret understanding

‘Why are you so edgy, kid?’

Asks the man with the voice

One thing follows another

You live and learn, you have no choice

I wormed my way into the heart of the crowd

I was shocked to find what was allowed

I didn’t lose myself in the crowd

I was shocked to find what was allowed

Didn’t lose myself in the crowd

Well, I wormed my way…

Shot by both sides

I don’t ask who’s doing the shooting

Shot by both sides

We must have come to a secret understanding

Jeremy Scott | Kayt Jones, 2003

3. Tom Verlaine & Richard Lloyd, ‘Days’ – Adventure, 1978

In a 1992 radio interview, Tom Verlaine said: When I went to New York in 1968 I played with a few guys and it was all Allman Brothers-type stuff, which I didn’t like, even in ’68. I had a guitar all the time, but I was much more concentrated on writing [poetry]. And then I remember going out to see some bands—around ’72 I think it was, the New York Dolls and a couple of other bands—which I didn’t care for at all. And I thought, well maybe I should put together a band, because I could use some of the stuff I was writing, along with music. And that eventually became Television. Tom Verlaine is a poet and his music works the way poetry does. Let me explain. Contrary to popular belief, poetry is not pretty words and clever rhymes, but a verbal evocation of ‘waking to wonder’. A lyric is not a poem. A poem has its own music and resonates best in its own word-sound framework. To set a poem to music1 is to over-egg the pudding. A lyric, in contrast, lends itself to music, in the same way that, in the sexual act, each partner lends themself to the other: what they accomplish together is greater than what either partner can achieve alone. In the lyric of ‘Days’, Verlaine disrupts the discursive2 content—lovers walking hand-in-hand-in the hills—with ‘splinters’ of poetry (silver, footprints, stream/dream). By doing so, he is prompting listeners to ‘float’ their attention and give play to their imagination, while the music, ‘working like poetry’, wakes the listener to wonder.3

1 – I’m talking of rock music, not classical or contemporary ‘art music’.

2 – Put simply, discursiveness tells, while poetry shows.

3 – I like to think the title of Verlaine’s 1990 album—The Wonder—is a nod to my analysis.

Alber Elbaz, Pauline Blassel | Kayt Jones, 2003

In the same 1992 radio interview, Tom Verlaine said: Working with Richard [Lloyd] is really different from song to song. In some cases he won’t have a part until he’s got his guitar solo, and he’ll take a bit of that solo and use it as a part through the song. On another song he might just be playing the chord bit, and on yet another song he may have come up with a counterpoint part to my guitar part. And in certain places he’s just doubling the bass. The better parts are the ones where he comes up with this counterpoint thing, where you have these two-voiced guitars, neither of which are just hitting chords. It is these ‘two-voiced guitars’, of course, that compose ‘Days’. Together with the bass and drums, the music they make is intensely lyrical without being sentimental, ravishingly lovely without being ‘pretty’. As for the solo, it has a proud humility, a tender virility; like the song itself, it is intimate without being indiscreet. These paradoxes abound in Verlaine’s lyrics, accounting for their surrealistic character.1 In formal terms, then, music and lyrics mirror each other. Compare Television’s ‘Days’ to Lou Reed’s ‘Perfect Day’ or to ‘Days’ by the Kinks: you will see that Verlaine’s poetic approach is much richer, both lyrically and musically, than Reed’s and Davies’ discursive2 aesthetic. In terms of the guitars, Tim Mitchell has pointed out that ‘Days’ features the reversal of a guitar line: Verlaine asked Richard Lloyd to reverse [play back to front] the guitar part from the Byrds’ version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Hey Mr. Tambourine Man’.3 Dispensing with volume and flash, Verlaine and Lloyd show, in ‘Days’, how touchingly beautiful a guitar solo can be.4

1 – Surrealism is but one component of Verlaine’s aesthetic. More broadly, his aesthetic is aligned with that of imagist poetry, characterized by ‘brevity, precision, purity of texture and concentration of meaning. There is no superfluous word, no merely ornamental adjective. The image itself is the speech’. (Ezra Pound in Imagist Poetry, Peter Jones, ed. [London: Penguin Classics, 2001])

2 – Recall that discursiveness tells, while poetry shows.

3 – Tim Mitchell, Sonic Transmission: Television, Tom Verlaine, Richard Hell (2006, Kindle edition). Mitchell adds: ‘The result gives a dreamy, ethereal lilt to a song in which love and nature are cyclical and eternal.’

4 – See Eric Haugen’s post on his ‘EricHaugenGuitar’ channel for a fine demonstration of what Tom Verlaine and Richard Lloyd are doing on ‘Days’.

Up in the high, high hills

With my floating friend

Watching all the silver

No one will ever spend

I feel the touch of her hand

And all it will erase

These footprints I followed

Though they followed my every pace

Days…

Be more than all we have

No matter how much I cross

I always see the same stream

I’m standing up on these bridges

That are standing in a dream

Days…

Be more than all we have

Days…

Véronique Branquinho, Kim Noorda | Cédric Buchet, 2007

4. Earl Slick, ‘Stay’ – David Bowie, Station to Station, 1976

Chris O’Leary: The intro assembles the group in formation. First Slick’s coiled spring of a riff on his Stratocaster, mixed right and echoed left: he needles his guitar’s D string until breaking off with two viciously-sounded G9 chords. Dennis Davis and Murray peg in a foundation, soon joined by congas, cowbell, shakers and an airy keyboard that sways between two chords. A second Slick track, perched center in the mix, dominates in roars and waves (Murray’s bass now paralleling Slick’s opening riff) while Alomar makes tart interjections. If Slick ruled the intro, the verses and refrains fell to Alomar, whose jaunty rhythm guitar paces the track, leaving Slick to bluntly echo his moves. At last in the closing solo the two fully go at it, Alomar lightly sparring and dodging while Slick plays variations of his opening riff and breaks into long, searing runs.1 Earl Slick: I think had we not been in that state of mind, that record would have never sounded like that. Staying up for two days at a time, and half out of our minds, just loosened us up to the point that we would do or try anything. We were very focused.2 ‘Stay’ pulls off the feat of being both dignified and dirty, earthy and aerial, hard rock and funky. Along with the contrast between the bluesy lead guitar and the James Brownesque funk of the rhythm, it is the opposition between the vocal line/voice and the music as a whole that gives the track its distinctive magic. Indeed, if the ‘searing runs’ of the lead guitar have a brooding, slow-burn quality, the vocal melody—complex, difficult to sing—is borne by a voice that is transparent in its blending of intimacy and distance, confidence and doubt. Given these contrasts, this solo (the long outro excluding the main riff), unlike my other selections, can only be fully appreciated, I feel, in its context.3

1 – Chris O’Leary, Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie From ’64 to ’76. (London: Zero Books, 2015) p. 400

2 – Dylan Jones, David Bowie: A Life (Random House, Kindle Edition, 2018) p. 234

3 – See Earl Slick and Carlos Alomar discuss the guitars in ‘Stay’ here.

This week dragged past me so slowly

The days fell on their knees

Maybe I’ll take something to help me

Hope someone takes after me

I guess there’s always some change in the weather

This time I know we could get it together

If I did casually mention tonight

That would be crazy tonight

Stay, that’s what I meant to say, or do something

But what I never say is stay this time

I really meant to so badly this time

‘Cause you can never really tell when somebody

Wants something you want too

Heartbreaker, heartbreaker, make me delight

Life is so vague when it brings someone new

This time tomorrow I’ll know what to do

I know it’s happened to you

Stay, that’s what I meant to say, or do something

But what I never say is stay this time

I really meant to so badly this time

‘Cause you can never really tell when somebody

Wants something you want too

Michael Kors | Hiroshi Kutomi, 2002

5. John Ashton, ‘Heaven’ – The Psychedelic Furs, Mirror Moves, 1984

If we define ‘taste’ as ‘the ability to make discerning judgments about artistic matters’, then John Ashton’s guitar in ‘Heaven’ is among the most tasteful in the rock repertory. The foundation of the track is the thumping drone of the bass and the shadowy, low-in-the-mix drums that parallel it. On top of this foundation is a repeated keyboard phrase in the verses, providing some ‘roll’ to the ‘rock’, and in the choruses, John Ashton’s ringing guitar. Against the density of the bass and drums, the spareness of his sequence of 3- or 4-note figures—beautifully ‘coloured’ in tone and with a lovely, bell-like clang—stands out like flowers in a forest. As for the solo, I find it at once exquisite and exciting, combining as it does delicacy and drive, enhancing the rhythm even as it sails upon it. Throughout the song, Ashton’s guitar is the surf to the gravel of Richard Butler’s voice. John Ashton’s ‘discerning judgment’ meant that he knew what to leave out—less is more—and it is largely because of this ‘taste’ of his that ‘Heaven’ is such a superb rock song.

Heaven

Is the whole of our hearts

And heaven

Don’t tear you apart

There’s too many kings wanna hold you down

And a world at the window gone underground

There’s a hole in the sky where the sun don’t shine

And a clock on the wall and it counts my time

And heaven

Is the whole of our hearts

And heaven

Don’t tear you apart

There’s a song on the air with a ‘love you’ line

And a face in a glass and it looks like mine

And I’m standing on ice when I say that I don’t hear praise

And I scream at the fools wanna jump my train

And heaven

Is the whole of our hearts

And heaven

Don’t tear you apart

Narciso Rodriguez | Rebecca Lewis

6. Pete Townshend, ‘Slow Burn’ – David Bowie, Heathen, 2002

‘Teenage Wildlife’, ‘Heroes’ and ‘Slow Burn’ constitute a kind of trilogy, as Nicholas Pegg has observed: Both ‘Heroes’ and ‘Teenage Wildlife’ are instantly recalled in the rolling bassline and soaring lead guitar of ‘Slow Burn’, although the shifting chords, doom-laden lyrics and soulful saxophone harmonics offer something entirely new. As most reviewers noted, ‘Slow Burn’ is distinguished by an excellent lead guitar performance by Pete Townshend.1 Chris O’Leary, discussing Bowie’s ‘deliberate amateur-ness’, mentions ‘Townshend wringing sustained notes across ‘Slow Burn’ as if trying to patch up a broken song’.2 To my ears, Townshend is not trying to ‘patch up a broken song’; instead, he is trying to underscore the fragmented nature of the music. ‘Heroes’: Berlin. Defiance in the teeth of despair. ‘Teenage Wildlife’: London. The ugliness of a teenage millionaire. ‘Slow Burn’: New York. The ghost in the machine. The reality ‘Slow Burn’ speaks of is a fractured one, the inevitable outcome of trying to live out one’s humanity (the ghost) in a dehumanizing society (the machine). The guitar solo, then, is not trying to paper over the cracks in the system, but to bring them to our attention. Bowie described Townshend’s playing on ‘Slow Burn’ as ‘eccentric and aggressive’,3 and that is how I hear it. Bowie has the courage of his convictions, and Townshend, aligning himself with songwriter’s vision, affirms it. It’s as if Pete is saying, ‘This is not the place for guitar heroics; these are the textures, this is the mood, and my job is to intensify them’. And he does so, playing against the rolling bass, opposing splinters and fractures, angularity and roughness—anxiety and fear—to its seductive assurance. What makes the guitar solo great, then, is the way is perfectly ‘reads’ the song and goes ‘out of the box’ to find what fits it.

1 – Nicholas Pegg, The Complete David Bowie (London: Titan Books, 2016; Kindle edition) p. 655

2 – Chris O’Leary, Pushing Ahead of the Dame

3 – Nicholas Pegg, ibid.

Here shall we live

In this terrible town

Where the price for our eyes

Shall squeeze them tight like a fist

And the walls shall have eyes

And the doors shall have ears

But we’ll dance in the dark

And they’ll play with our lives

Like a slow burn

Leading us on and on

Like a slow burn

Turning us round and round and round

But who are we

So small in times such as these?

Slow burn

These are the days

These are the strangest of all

These are the nights

These are the darkest to fall

But who knows?

Echoes in tenement halls

Who knows?

Though the years snare them all

Like a slow burn

Leading us on and on and on

Like a slow burn

Turning us round and round and upside down

There’s fear overhead

There’s fear all around

Slow burn

Like a slow burn

Leading us on and on and on

Like a slow burn

Turning us round and round and round

And here are we

At the center of it all

Slow burn

Rei Kawakubo, Missy Rayder | Richard Burbridge, 2004

7. Eric Clapton, ‘I’d Have You Anytime’ – George Harrison, All Things Must Pass, 1970

On ‘I’d Have You Anytime’, Eric Clapton delivers one of the loveliest solos in all of rock, a solo that is at once an outro and a development of the embellishments the guitar has been providing the vocal line all along. Pianist Alexis Weissenberg declared in an interview that ‘the most formidable technical and musical task for a pianist to achieve is not the playing of a bravura piece, but rather to play a slow movement from Beethoven, Mozart or Schubert—to play it well, with perfect nervous and sound control’.1 If the loveliness of Eric Clapton’s solo is so touching, it is precisely because, in the context of this slow song, he plays it ‘with perfect nervous and sound control’. On condition the artist has something to say, understatement, as an artistic strategy, can be extremely effective. A child holding back their tears, for example, is far more moving than a child who is crying. The guitar solo in ‘I’d Have You Anytime’ demonstrates the virtue of such understatement. But what exactly is the song saying? As I see it, it is a convincing demonstration of the aesthetics of grace. It comes out of the burgeoning friendship between George Harrison and Bob Dylan, at a time when both of them were vulnerable. The song asserts their shared desire to deepen their friendship (Dylan wrote some of the lyrics), and it exhibits all the features of grace: dignity and mercy, charm and beauty, gratitude and elegance. Insofar as it deals with an intersubjective relation (Harrison-Dylan), it is a fusion of the aesthetic and the ethical. It is this that Clapton’s guitar is called upon to evoke, and if it does so so sublimely, it is also because this song, arising out of Harrison’s desire to deepen his friendship with Dylan, is served by Clapton’s friendship with Harrison.

1 – Alexis Weissenberg in David Dubal, Reflections from the Keyboard: The World of the Concert Pianist (New York: Summit Books, 1984): 333

Let me in here, I know I’ve been here

Let me into your heart

Let me know you, let me show you

Let me roll it to you

All I have is yours

All you see is mine

And I’m glad to hold you in my arms

I’d have you anytime

Let me say it, let me play it

Let me lay it on you

Let me know you, let me show you

Let me grow upon you

All I have is yours

All you see is mine

And I’m glad to hold you in my arms

I’d have you anytime

Let me in here, I know I’ve been here

Let me into your heart

Marc Jacobs, Anouck Lepère | Greg Lotus, 2001

8. Mick Taylor, ‘Can’t You Hear Me Knocking’ – The Rolling Stones, Sticky Fingers, 1971

That Mick Taylor’s solo in ‘Can’t You Hear Me Knocking’ emerged spontaneously from a jam that prolonged the recording of the ‘planned’ song is, I believe, significant. Why? Because it is supreme testimony to the power of music to summon up the spirit realm, to induce in the listener a state of surrender, an oceanic feeling of oneness with one’s ‘authentic self’, a self freed from its neurotic armour: ‘letting go’ during the jam is what enables this state. From this perspective, Mick Taylor is the shaman of the trance, the one whose guitar solo, emerging from the rest of the music, penetrates into the beyond, consecrating, as it were, the arrival in the spiritual realm. Jean Jacques Rousseau: As long as we choose to consider sounds only through the commotion they stir in our nerves, we will never have the true principles of music and of its power over our hearts.1 It is not surprising that music, along with dance, was the first of the arts; just as it is not surprising that poetry existed long before prose. It is this primal quality of music that Mick Taylor makes resonate with the pulse of our hearts, and that is why I consider his solo among the very finest in the repertoire.

1 – Jean Jacques Rousseau, Essay on the Origin of Languages.

Yeah, you got satin shoes

Yeah, you got plastic boots

You all got cocaine eyes

Yeah, you got speed freak jive now

Can’t you hear me knocking

On your window?

Can’t you hear me knocking

On your door?

Can’t you hear me knocking

Down your dirty street?

Help me, baby, ain’t no stranger

Can’t you hear me knocking?

Are you safe asleep?

Can’t you hear me knocking?

Down the gaslight street now

Can’t you hear me knocking?

Throw me down the keys

Hear me ringing, big bell tolls

Hear me singing, soft and low

I’ve been begging, on my knees

I’ve been kicking, help me please

Hear me prowling

I’m gonna take you down

Hear me growling

I’ve got fight in me now, now, now

Hear me howling

All around your street now

Hear me knocking

All around your town

Sylvia Venturini Fendi | Thomas Schenk, 2000

9. Robby Krieger, ‘Five to One’ – The Doors, Waiting for the Sun, 1968

Just as the Doors have an unmistakable musical identity, Robby Krieger has, to my ears, the most distinctive guitar style in rock. In ‘Five to One’, the filigree of his fingerstyle solo, played high up the neck, bursts through the brutish monolith of the bass and drums to throw the song into relief: a floodlight in the night, a face coming into focus, the punchline of a joke. Its urgency and anger fit the song perfectly. That anger, I note anecdotally, also characterized the recording session. Robby Krieger: Relatively, Jim was on his best behavior when we recorded our first two albums. Sure, he hosed down the studio with a fire extinguisher, but we would’ve preferred that any day over dragging him through endless drunken vocal takes. The worst experience was when we were recording ‘Five to One’. On the finished album, a casual listener will hear an iconic vocal take. It’s classic Morrison, howling for a long-awaited revolution. When he sings ‘Your ballroom days are over, baby,’ it’s wonderfully anarchic, but in the studio we couldn’t believe how out of time he was. If you close your eyes and listen closely, you can hear the tension. You can hear an exasperated producer and three cringing bandmates who have all been dealing with the effects of endless technical tweaks, who have all been coping with the obnoxiousness of the Magic Tramps [Jim Morrison’s drinking companions], who have been forced to sit through a bunch of completely unusable takes, who are staring daggers at their drunken singer, who are desperately hoping they’ll get something that will work. It’s almost a tragedy that Waiting for the Sun ended up being our only album to hit number one. Because it normalized everything. It gave Jim an excuse not to change his behavior, and it gave the rest of us an excuse to ignore it. We were happy when we heard we had topped the charts. Maybe we shouldn’t have been.1 As often in art, beauty arises out of ugliness. Indeed, Robby Krieger—endlessly inventive, always true to himself—came up with a magnificent solo in ‘Five to One’, lighting up the darkness of the song while preserving its scowling swagger.

1 – Robby Krieger, Set the Night on Fire: Living, Dying and Playing Guitar with the Doors (London: Orion, 2021) pp. 195-196

Five to one, baby

One in five

No one here gets out alive

Now, you get yours, baby

I’ll get mine

Gonna make it baby

If we try

The old get old and the young get stronger

May take a week and it may take longer

They got the guns but we got the numbers

Gonna win, yeah, we’re taking over

Come on

Your ballroom days are over, baby

Night is drawing near

Shadows of the evening

Crawl across the years

You walk across the floor with a flower in your hand

Trying to tell me no one understands

Trade in your hours for a handful of dimes

Gonna make it, baby, in our prime

Get together one more time

Olivier Theyskens | Sophie Delaporte, 2001

10. Steve Hunter & Dick Wagner, ‘Intro/Sweet Jane’ – Lou Reed, Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal, 1974

Among the finest live rock ‘n’ roll performances ever recorded, Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal and Lou Reed Live present a total of eleven Lou Reed/Velvet Underground songs revisited by a band chosen for the occasion of the concert. Lou Reed submits his songs to this revisioning and sings the lyrics accordingly. Recorded at the same concert, the performance paints what is perhaps the finest portrait of Lou Reed. It is from this perspective, then, that I will discuss the guitar solos in ‘Intro/Sweet Jane’. Both guitarists, Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner, played on Berlin, Lou Reed’s then-latest album. Consciously or not, they assimilated something of Lou Reed’s spirit, and ‘what they have to say’, in their playing on ‘Intro/Sweet Jane’, is precisely their interpretation of that spirit. How to describe it? The guitarists conjure a defiant dignity, a searing pain that refuses self-pity, a disdainful violence edged with anger and a stately pride bordering on majesty. The guitars play on the other side of the fire of individuality, the struggle to ‘become who one is’, and only those who have walked through that fire can hear all the music has to offer. On 21 December 1973, the night of the concert, Lou Reed was in a troubled frame of mind. Berlin, which he considered his finest work, had been vilified by the critics. Heroin had a hold on him. Acting out his homosexuality did not satisfy him. And yet, thanks mainly to Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner and their ‘re-creation’ of his songs, he delivered one of his finest performances. As with Robby Krieger and ‘Five to One’, out of ugliness the guitarists made beauty. The solos in ‘Intro/Sweet Jane’ are great, then, because they are driven by ‘something to say’, and that something is the spirit of Lou Reed.

Standing on a corner, suitcase in my hand

Jack’s in his corset, Jane is in her vest

Me, honey, I’m in a rock n’ roll band

Riding a Stutz Bearcat, Jim

Those were different times, they studied rules of verse

And the ladies, they rolled their eyes

Sweet Jane, Sweet Jane, Sweet Jane

Jack he is a banker

And Jane she is a clerk

Both of them save their money

When they come home from work

Sitting there by the fire

The radio does play—a little classical music there kids—

The March of Wooden Soldiers

You can hear Jack say

Sweet Jane, Sweet Jane, Sweet Jane

Some people like to go out dancing

And other people like us we gotta work

There’s even some evil mothers

They’ll tell you that life is just made out of dirt

That women never really faint

That villains always blink their eyes

That children are the only ones who blush

That life is just to die

But anyone who had a heart

Wouldn’t turn around and break it

Anyone who ever played a part

Wouldn’t turn around and hate it

Sweet Jane, Sweet Jane, Sweet Jane

Horsting & Snoeren, Yasmin Le Bon | Sølve Sundsbo, 2009

So there you have it, dear reader, my alternative perspective, my own ‘top ten guitar solos’. What is your verdict on this ‘experiment in criticism’? Have I managed to procure you a measure of ‘instruction and delight’? Have I enhanced your pleasure in the music? Whatever the case may be, I welcome your comments via the comment box below. Long live rock! Thank you.

Marios Schwab, Julia Stegna |Magnus Unnar, 2006

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments