Stories Must Enchant and Astonish

MARIO VARGAS LLOSA ON THE NOVEL: AN INTERVIEW

Alonso Cueto

Translated here from the French by Richard Jonathan

From Mario Vargas Llosa: La vie en mouvement: Entretiens avec Alonso Cueto (Paris: Gallimard, 2006) pp. 71-81.

Original Spanish edition: Lima: Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas, 2003.

Translated here by Richard Jonathan from Albert Bensoussan’s French translation from the Spanish.

Julio Cortázar & Mario Vargas Llosa, 1967 | Mario Vargas Llosa

I. DRAFTING A STORY

You once explained that to write your novels you rough out a few lines of the story, which you do not necessarily pursue afterwards.

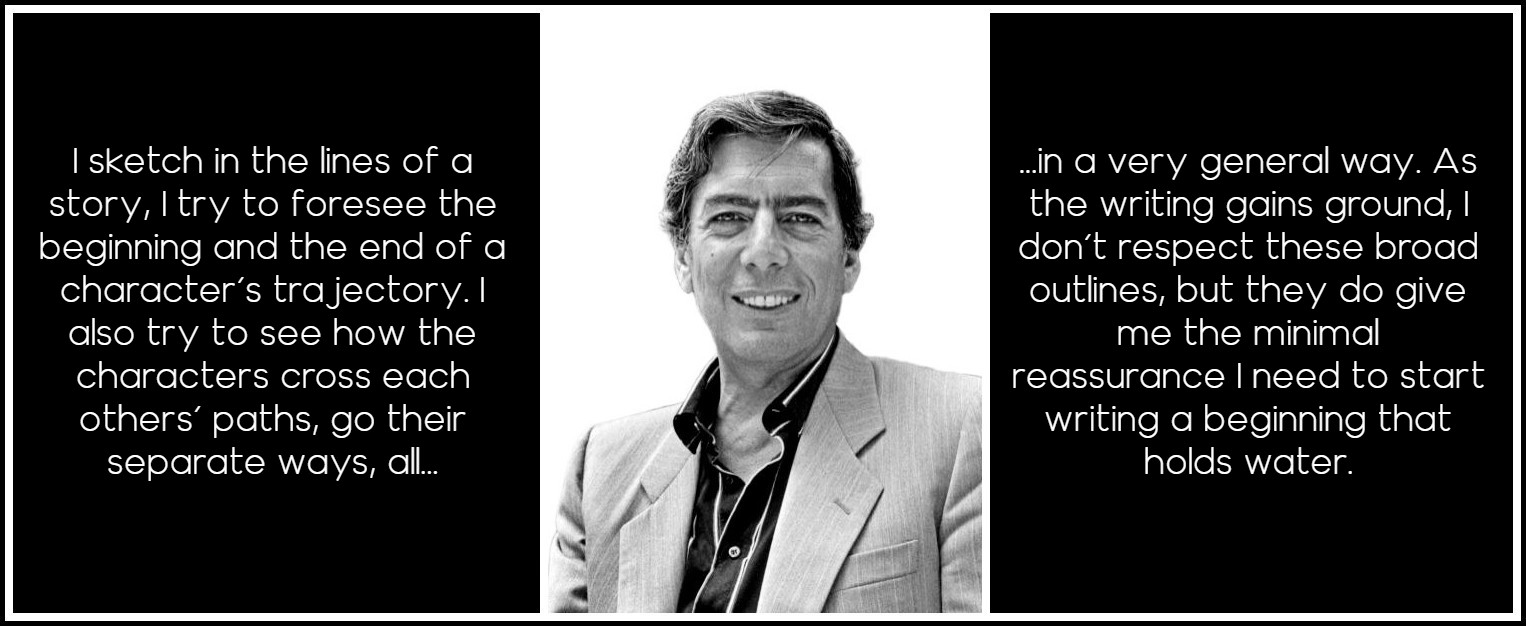

Yes, I do sketch in the lines of a story, though only in a very general and vague way. I try to foresee the beginning and the end of a character’s trajectory. I also try to see how the characters cross each others’ paths, go their separate ways, still in a very general way. Of course, as the writing gains ground, I don’t respect these broad outlines, but they do give me the minimal reassurance I need to start writing a beginning that holds water. In other cases the story arises out of a situation, or an anecdote. It’s rare that I’ve conceived a character right from the start. It does happen, of course. In a novel like The Way to Paradise, the character [Flora Tristan, Paul Gauguin’s grandmother] was of course the starting point of the story. But it’s altogether different for stories where the material is not historical. Very often the character is but a shadow, a vague silhouette, who becomes more substantial as the work progresses. While working on the sketch—which is very chaotic, very conventional, very repetitive—the character acquires distinctive traits and qualities. I often have a lot of trouble feeling confident with the character; it only happens after a great deal of work.

Mario Vargas Llosa

And then there comes a time when the character takes responsibility for himself and becomes more independent, propelling the story forward?

Yes. That’s a turning point: the author starts obeying the character. You have to follow him, respect him, wherever he may lead you. He now has his own autonomy.

The relations between a writer and his characters are often intimate. Would you agree that many of your characters have something of yourself?

I believe an author is diffused in his characters, even in the most antagonistic ones. A character is always a product of the writer. If the writer has put nothing of himself in the character, then the character will never breathe, will never become lifelike. This process, of course, is largely unconscious.

Urania Cabral in The Feast of the Goat and Santiago Zavala in Conversation in the Cathedral are two of Mario Vargas Llosa’s strongest characters.

II. THE ART OF STORY-TELLING

You have spoken of the importance of the story in a novel. Do you believe every novelist should tell a story, or should the story be subordinate to ideas, digressions, or the description of anecdotes?

Well, some writers—myself among them—are story-tellers. That is what I try to do when I write—which, I hasten to add, does not mean that I disregard the purely formal or technical aspects. A good story depends in large measure on technique, form, the elaboration of the structure. There are, of course, writers in whose novels the story is but a pretext for formal development or the creation of a literary language. One sometimes wonders, in the case of great novelists, to what extent they have any real interest in the story. I’m thinking, for example, of a novel like Paradiso, by Lezama Lima. It does have a story, but it is largely secondary, in the background, and ends up very vague, a pure pretext for verbal luxuriance, for the creation of a strictly verbal reality. That is not at all what I do. The story excites me, and what impresses me most in a novel is a story that takes on a life of its own, that is not subservient to or dependent on anything else. That, of course, requires great technical competence.

Mario Vargas Llosa

Would you agree that stories are essential to a community? That, as a heritage, they nourish social and cultural life, and, in a way, constitute the foundation of a society?

Stories have always been instrumental in assuring social cohesion. Sagas, for example, were folk stories; at the same time they constituted a tradition that referred to historical continuity and a mythical past. Sagas are the distant ancestors of the novel.

I believe that at the beginning, when the first stories were being told, it was the astonishment they engendered in listeners that made communities adopt them. I believe no modern writer, however civilized, can renounce this precious gift of astonishment.

I agree. Fundamentally, stories must enchant and astonish. I think that has to do with our collective unconscious, going back to a very distant time when the border between reality and imagination was not firmly fixed. Reality and imagination were blended, they bled into each other. Religion was expressed via literature. The Bible abounds in stories, which one can read as literature, not religion. They are marvelous, surprising stories. Literature then became secular. No longer religious, it nevertheless continued to enchant. In general, in religion as well as in literature, belief in the story one is telling is fundamental. A secular writer must strive to draw out this conviction via effects of language, not the powers of revelation or religious belief. That’s the big difference.

Mario Vargas Llosa, 1967 | Photo: M.C. Orive

III. FLAUBERT, VICTOR HUGO, FAULKNER

Among the many writers who have counted for you, three are of fundamental importance: Flaubert, Victor Hugo, and Faulkner. What has each one brought you?

Victor Hugo goes back the furthest. I read him when I was very young, still almost a child. Ever since then I’ve been enchanted by the variety and complexity of the worlds he depicts, the big adventures. He creates characters who refuse to be confined, who become prototypes of generosity, cruelty, justice. They push themselves to the limit. Whether in kindness or in meanness, they have greatness. The generosity and magnanimity of Jean Valjean; the innocence, mischievousness, and grace of Gavroche; all the other characters—Marius, Javert, Cosette—they are unsurpassable models. It’s in Hugo that we find characters who transcend limits, who create a kind of human prototype. I’ve read a lot of Victor Hugo, and of all his work it’s Les Misérables that has had the greatest impact on me.

Victor Hugo

I read Faulkner at university and right away I was fascinated by his stories, by his compact world where characters pass from one novel to another, one story to another. I came under the spell of his technique. It’s thanks to him that I understood the role technique plays in creating literary enchantment. His novels demand a lot from the reader, they can be difficult at times, but that effort proves very rewarding. It’s like going on an expedition in a virgin forest and discovering treasures one by one.

In Faulkner, in spite of the verbal complexity, one finds very distinct visual images.

Yes. Technique in Faulkner does not diminish the intensity of his characters or his scenes. Quite the opposite. It creates an atmosphere, a state of uncertainty. In distracting one from the essential, it brings the essential into relief.

William Faulkner, 1956 | Photo: Richard Crowder

The violence of Faulkner’s language reflects the violence of the reality he is presenting, doesn’t it?

Yes. That is why Faulkner is so close to Latin American writers: his world has affinities with ours. Our social and cultural traditions derive from a heritage of brutal violence, unassimilated in the present. It’s a heritage of different races and traditions. Faulkner’s entire universe is Latin American. I remember that scene in Light in August where Percy Grimm kills and castrates Joe Christmas, and there’s an immense metaphor.1 Well, that is what dazzles a budding writer—that technique and those images, they raise the story to a mythical level. Faulkner creates such rich and subtle atmospheres, often of a prodigious brutality and humanity.

1 – ‘From out the slashed garments about his hips and loins the pent black blood seemed to rush like a released breath. It seemed to rush out of his pale body like the rush of sparks from a rising rocket; upon that black blast the man seemed to rise soaring into their memories forever and ever.’ Faulkner, Light in August, chapter 19.

William Faulkner, 1960 | Passport photo

Flaubert’s case is much more concrete. His is the type of novel that was clearly the type I wanted to write: a novel that simulates reality via a technique that simulates objectivity. That’s the big difference between Flaubert and Faulkner. Faulkner is subjective. In Flaubert, everything is rendered with the precision, exactitude and distance that characterizes objective reality. That really impressed me. The notion of the invisible narrator, of the novel that presents itself as self-sufficient—those are the notions that founded the modern novel, and they first take form in Flaubert. His example is very important to me because it showed me that discipline and perseverance bring out one’s talent. I didn’t feel very sure of myself and Flaubert became my model; he gave me a method of working and an attitude towards literature.

Gustave Flaubert

IV. THE BEGINNING OF A NOVEL

What is the starting point of a novel for you?

It changes a lot. Sometimes it’s a character, sometimes a situation. In The Way to Paradise, as I mentioned, it began with the character, Flora Tristan. Afterwards came the political context, landscapes, nineteenth-century history, the utopians, Peru, and so on. But at the beginning there was only the character. In The Time of the Hero, on the other hand, my starting point was an atmosphere: the world of Leoncio Prado, which was a self-sufficient world, a Darwinian world of great violence where the weak were crushed by the strong. The characters arose afterwards.

1 – Leoncio Prado Gutiérrez (25 August 1853 – 15 July 1883), was a Peruvian soldier and adventurer who participated in various military actions against Spain; in Cuba and the Philippines in the 1870s. He also participated in other wars such as the Chincha Islands War (1865-1866) and the War of the Pacific (1879-1883), dying in the latter. (Wikipedia)

Mario Vargas Llosa: The Way to Paradise & The Time of the Hero

In the case of The Storyteller it was a conversation. When I met a sociolinguist at the Summer Institute of Linguistics in 1958, a story she told me became lodged in my memory, a story about a man who joined a community and who talked and talked throughout the night. His speech was chaotic, mixing anecdotes, stories, personal confessions, commentaries and legends. That’s the image that remained with me, this storyteller who goes from village to village, family to family, with his continuous speech, speech in which people recognize themselves, and so in a way he becomes part of the community. At the beginning that’s all I had, there was no concrete character.

Mario Vargas Llosa, The Storyteller

The origin of the story ‘The Cubs’ was something I read in a newspaper, an article about the castration of a boy bitten by a dog. What interested me was to tell a story about a wound which, in contrast to other wounds which close with time, was going to open. My idea was to write a story about a gang of kids in a neighbourhood and to link the story of the wound to the atmosphere of the neighbourhood. I recalled how the gang of boys and girls lived, how they grew up together, how they had their own rites of passage, and so on. The protagonist of ‘The Cubs’ suddenly became associated with the neighbourhood, and so I set him in that particular milieu.

Mario Vargas Llosa, Los jefes, Los cachorros

The same process—a character who finds his context only later in the build-up to the writing—has been repeated for other novels. For example, I had in mind a story about Spanish anarchists and I discovered that a group of anarchists in Barcelona had been fascinated by phrenology. Phrenology, as they conceived it, demystified God. It was the science of a materialism that affirms that the nature of the soul is inscribed in the bones of the head. These phrenological anarchists attracted me greatly as characters, but I didn’t know how to work them into a story. When I was writing The War of the End of the World, I thought they would fit in perfectly, via a character like Galileo Gall. That’s how it works: I have a vast attic of ideas in my mind, some of which, with time, link up with other ideas and find a place in the writing process. What’s best is when long-forgotten ideas suddenly arise and contribute to the story. I would add that one is not totally free to choose one’s stories. They are imposed on one by that secret attic that stores images, characters, situations—in a word, memories. Of course, most of them have been altered in one way or another, since that is the nature of memory.

Mario Vargas Llosa, La guerra del fin del mundo

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments