A First-Person Emphasis New to Painting

PIERRE BONNARD: A NEW SPACE FOR THE SELF

Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman (1946-2024), painter and curator, was one of the most refreshing and invigorating writers on art in the first quarter of this century.

From Timothy Hyman, The World New Made: Figurative Painting in the Twentieth Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 2016) pp. 116-117; 128-133

Pierre Bonnard, 1 February 1934 (detail, colorized)

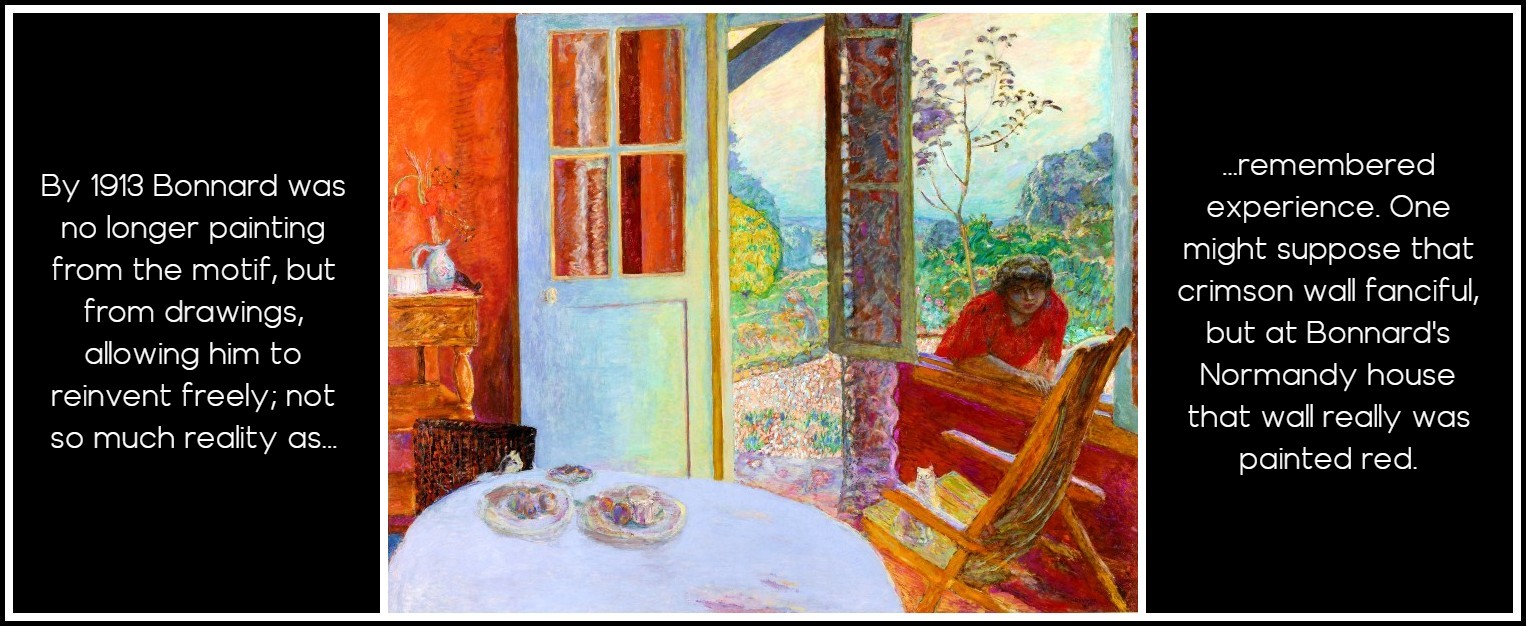

The early years of the twentieth century were a time of difficult transition for Bonnard. At their outset he had felt himself to be part of a group endeavour; the Intimists wanted ‘to pick up the research of the Impressionists, and to take it further. Art is not Nature. We were stricter in composition. There was a lot more to be got out of colour as a means of expression’. Bonnard had been interested in the philosophy of Henri Bergson, in his emphasis on the subjectivity of sensory experience: the self as rebuilding or reassembling the world into images. But meanwhile the notion of art as an evolutionary progression of movements took hold. After the ascendancy of Cubism in 1910-11, the Intimist quest appeared retrograde: ‘We were left, so to speak, dangling in mid-air.’ Yet by 1913, when Bonnard was forty, he was able to fulfil that project in a defining masterpiece, Dining Room in the Country. Bonnard employs here the approximate qualities of Impressionist mark-making to stress the personal, the individual. If the Impressionists had aspired to remove the self from perception, Bonnard would put it back again, registering the place of the spectator—Bonnard’s own place—with a first-person emphasis new to painting.

Pierre Bonnard, Dining Room in the Country, 1913

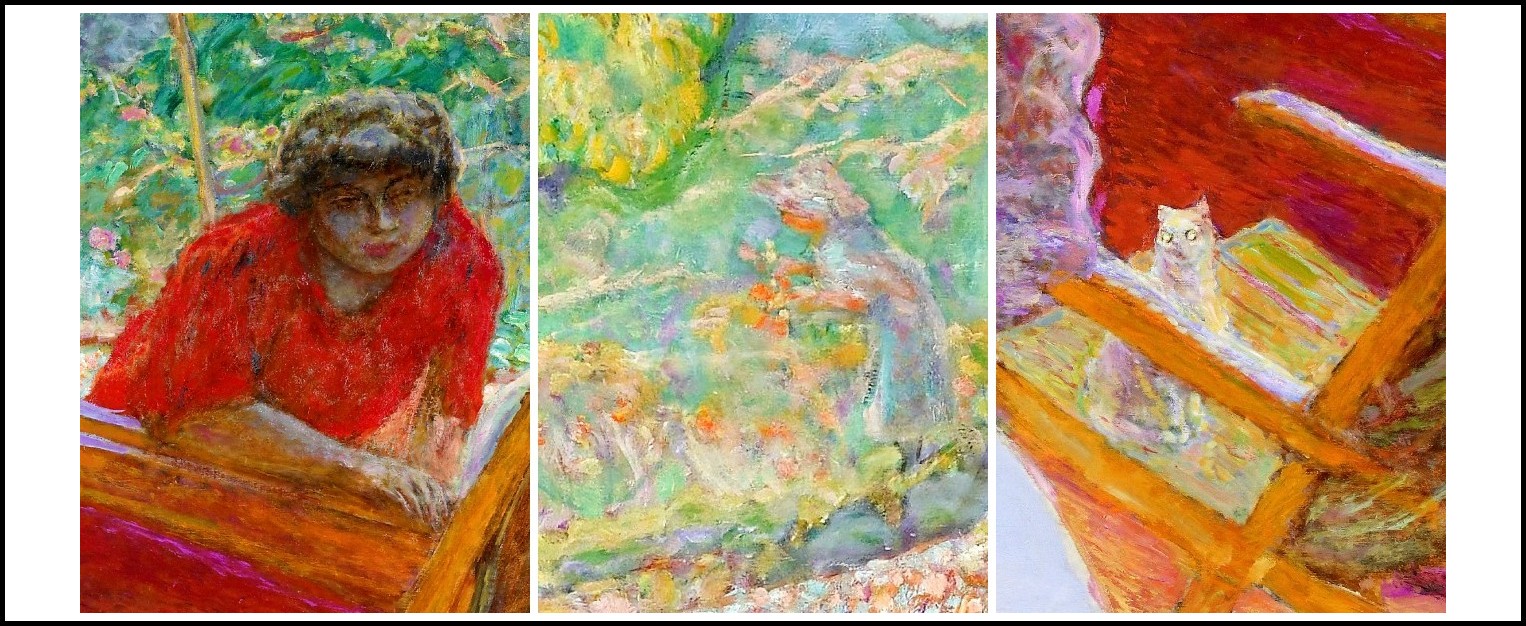

The almost seven-foot scale is surprising—much larger than one might expect from reproduction, and larger than such an intimate space might seem to call for. The subject is not immediately evident, its inventory only slowly unpacked to our sight. We are placed this side of a wide expanse of milky, mother-of-pearl table-top, and at first we may think we are in an empty room, dominated by the bold central geometry of door and frame; until we find ourselves in eye contact with the shadowed figure off to the right, who looks in at us from outside the window. (Eventually we make out also two little kittens, and—perhaps quite some while later—a child picking flowers in the garden.) Once we have glimpsed her presence, everything is charged with that relationship. The room becomes the vessel of an extraordinary tenderness, its red walls an extension of that red, smiling figure. We might see the table as a kind of wheel, turning the successive planes one after the other, enacting the transformation: of the quotidian into the epiphany, of solitude into love, and of ‘reality’ into first-person experience.

Pierre Bonnard, Dining Room in the Country, 1913 (details)

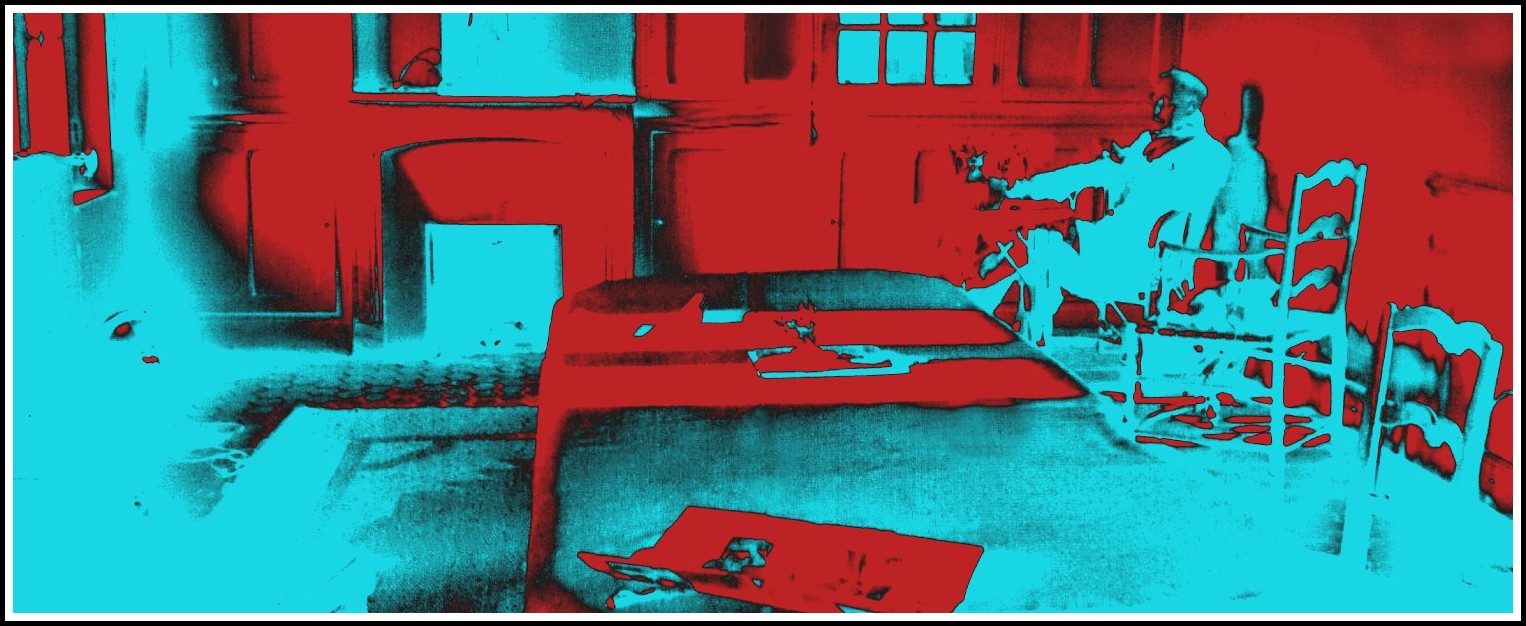

Bonnard developed his own radical procedures of very rapid drawing—accumulating small sheets on which nearly all his greatest paintings depended. In his later works, Bonnard makes explicit, more than any artist before, the space that extends between the self and the world. He becomes acutely attentive to the mechanics of seeing; those ‘adventures’ increasingly set in question the conventions through which earlier artists had conveyed our experience of space. Phenomena that had long been observed in the literature of perception (such as the bending lines at the junction of wall and ceiling, or the darkening and striation that occurs on the periphery of the visual field) begin to appear in painting after painting. Pencil in hand, Bonnard set himself to unlearning the kind of seeing associated with the fixed stare of the art-school life room. After 1916, he’d ceased to use his Kodak camera, which has been described as ‘a little Brunelleschi box’; that is, the image restricted to the same forty degrees as one-point linear perspective. He’d become more aware of the disparity between lens and seeing: ‘The eye of the painter gives to objects a human value and reproduces things as the human eye sees them. And this vision is mutable, and this vision is mobile.’ To monumentalize the glimpse, to make altarpieces out of the ephemeral; in his later work, Bonnard transfers the terms of an 1890s symbolist quest (the storing-up of aesthetic moments) to the harsher world of twentieth-century modernism—renewing it, and in a sense redeeming it. (That seems to me also true of the writings of, say, Proust and Yeats, Robert Musil and John Cowper Powys: they all explore the epiphany through the medium of the self.)

Pierre Bonnard in the living room of his villa, Le Bosquet, in Le Cannet, 1944 (detail, colorized)

When Bonnard in so many of his bathroom pictures signals his own presence within the image, he marks out a special territory of feeling. I suppose we are all familiar with seeing a part of ourselves intrude into the visual field: the tip of one’s nose, a spectacle-rim, a knee, a hand. In his Large Blue Nude (1924) Bonnard’s pale leg edges in, and a ‘nude’ is transformed into a relationship; not Artist and Model, but Pierre and Marthe. We now know that throughout much of her life ‘Marthe’ (Maria Boursin) was afflicted with a mania for cleansing herself. Bonnard had come close to leaving her. But having committed at last to marriage, he moved with her to the south of France, where they became increasingly isolated. As he wrote to his friend Georges Besson in 1930: ‘For quite some time now I have been living a very secluded life as Marthe has become completely antisocial and I am obliged to drop all contact with other people. I have hopes though that this state of affairs will change for the better but it is rather painful.’ The presence of the self charges everything with subjectivity, with emotional ambiguity and psychological complexity. Bonnard sits, holding his knee, gazing in contemplation—perhaps not so much at Marthe as the dazzling patch of light on her back, rendered in thick impasto. The shadowy blue and purple surrounding this radiant form evokes an underwater world, and Marthe, reaching into darkness, seems more remote than ever.

Pierre Bonnard, Large Blue Nude, 1924

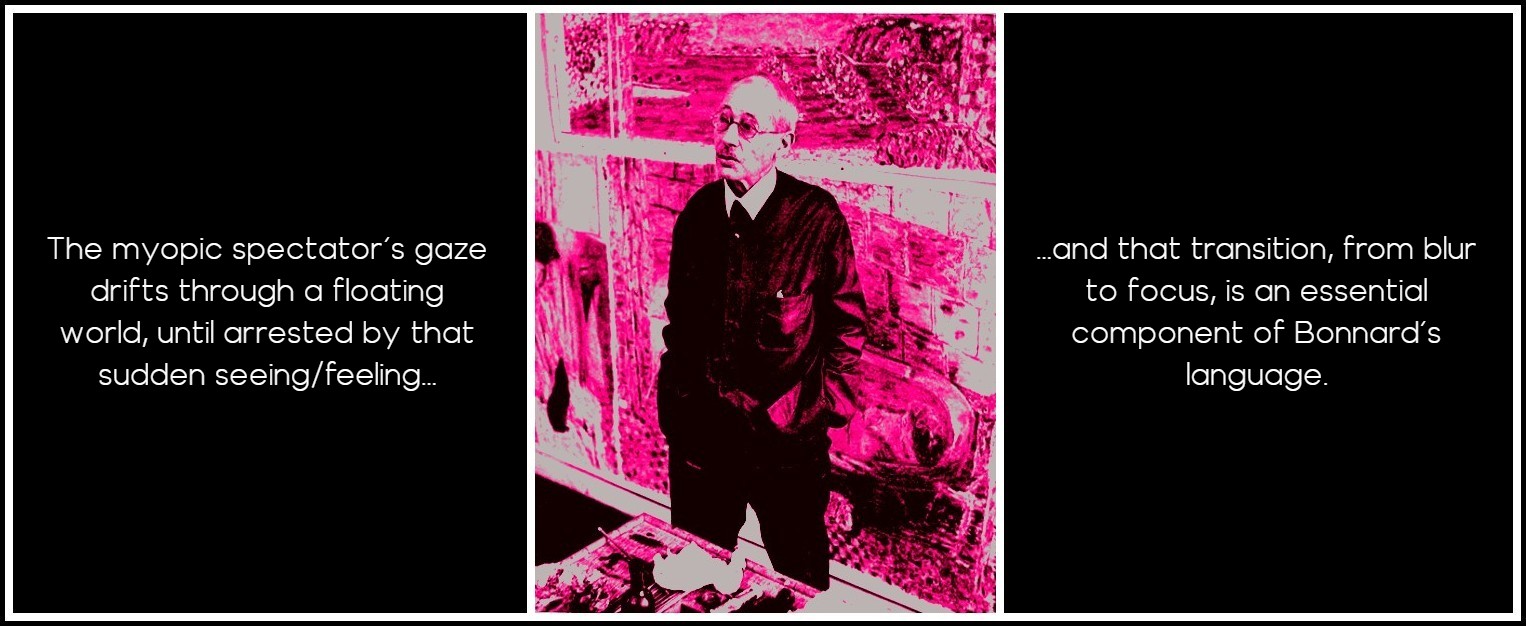

Bonnard associated the inception of each picture with a sudden involuntary heightening of emotion. ‘Consciousness’, he writes, ‘the shock of feeling and of memory.’ The myopic spectator’s gaze drifts through a floating world, until arrested by that sudden seeing/feeling—and that transition, from blur to focus, is an essential component of Bonnard’s language. His art, centred on the exceptional moment—on the moment that detaches itself from the flow of everyday living—discovered new constructions of wide-angled space, and astonishing intensities of colour, pictorial equivalents to his startled epiphanies. In the previously uncharted territory of peripheral vision, it was as though the central area of fact were surrounded by much less predictable, almost fabulous margins; where subjectivities—imagination, reverie, memory—could be asserted.

Pierre Bonnard | Photo: André Ostier, 1941 (colorized)

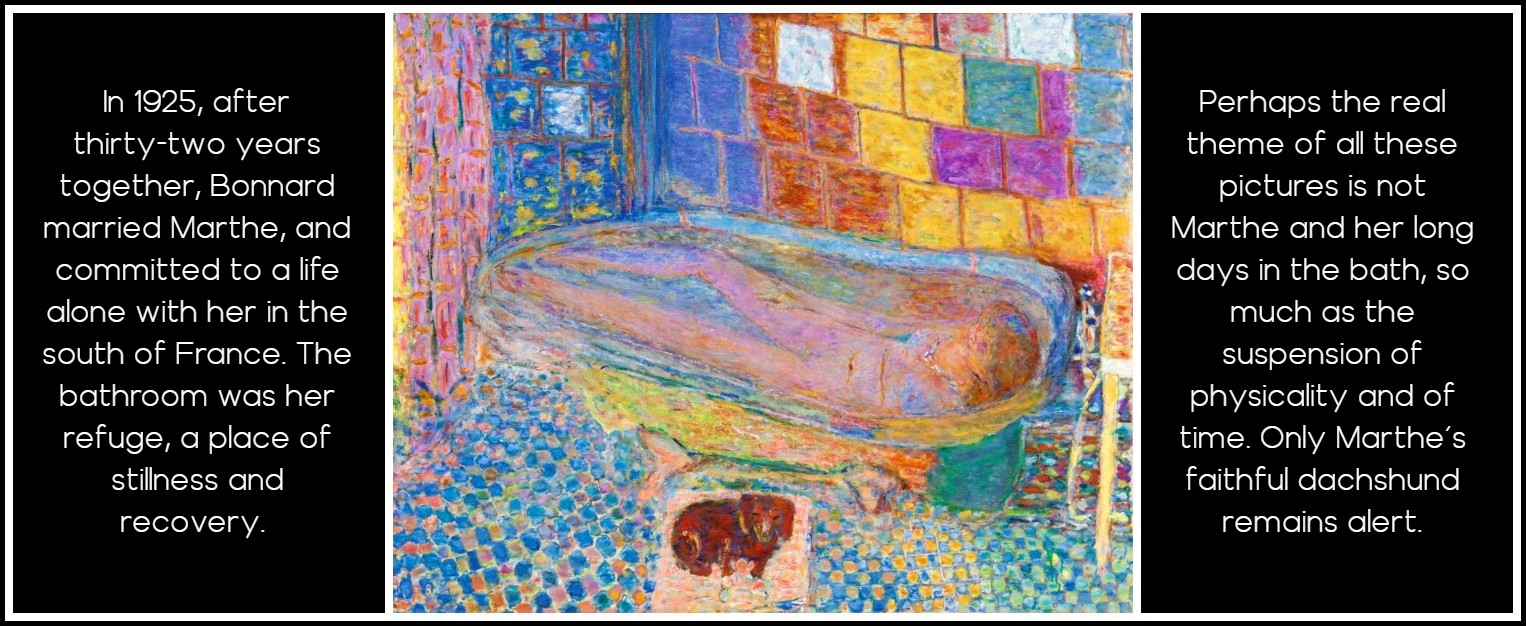

The third and by far the most extreme of Bonnard’s large baignoires was begun two years into the Second World War, in 1941, when Marthe was already in her seventies, and completed in 1946 four years after her death. The stricken woman took her hours-long baths in full sunlight, in the middle of the day. Dazzlingly reflected in tiles and floor, the Riviera sun is shown flooding in from the two windows—those inexplicable shifts of light and hue that seem to stand here for the passing of time, extended in reverie. A pale-tiled, very ordinary bathroom has over several years become utterly transformed, until it wraps the bather in a kind of crazy quilt. Most amazing of all are those passages where the bath narrows, then seemingly exhales and expands, buckling, merging with the vibrating floor; the paint here is crusty, layer upon layer, and the drawn edges of bath and figure just barely defined, by a brush—or a fingertip—dipped in crimson, dragged loosely across the surface. The bath appears a crystalline sarcophagus, in whose light the dead woman becomes transfigured.

Pierre Bonnard, Nude in Bathtub, 1941-46

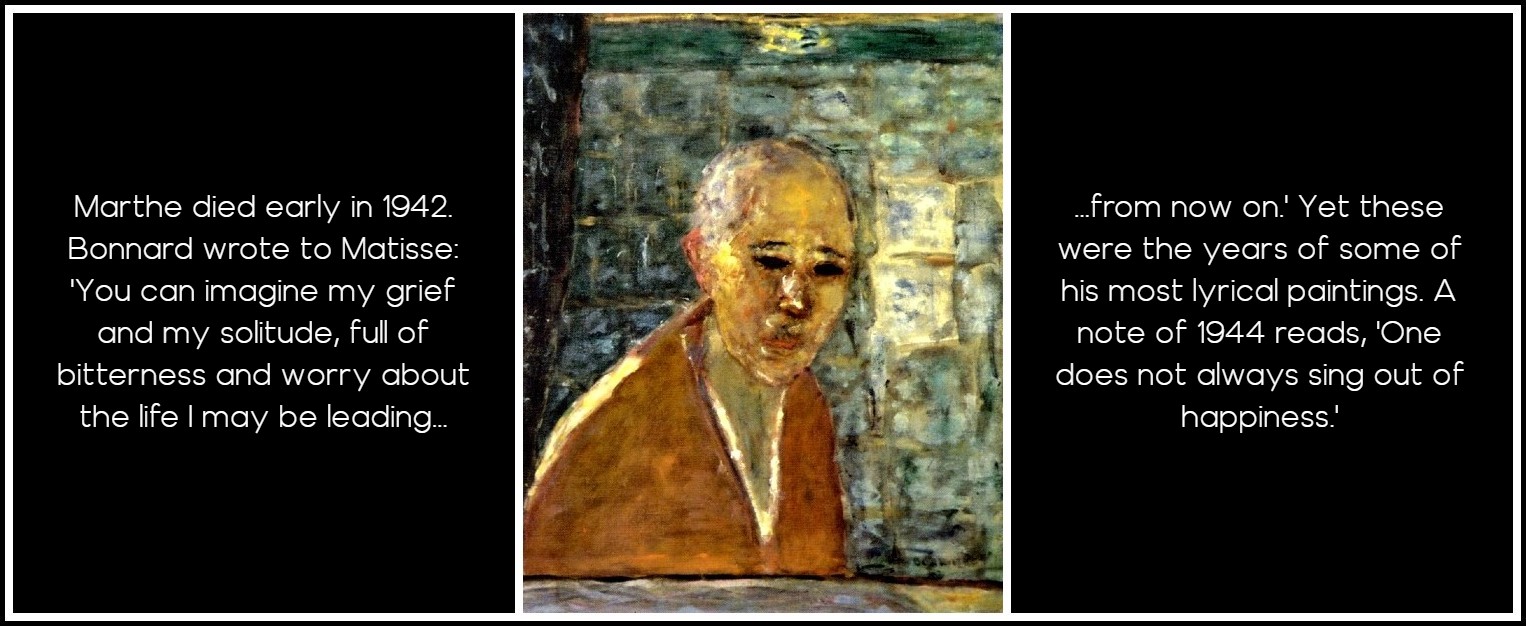

Bonnard’s late self-portraits (most of them glimpsed in the bathroom mirror under artificial light) are among the most poignant in all painting—linked formally by their use of contre-jour, rendering the self always in shadow. The most disquieting and confessional is The Boxer of 1931, squaring up to the mirror with puny fists. From the battered red pulp of the head—a lump of raw meat set atop the naked torso—there emanates a terrible pathos, eyes lowered in impotent defeat.

Pierre Bonnard, The Boxer, 1931

In a self-portrait completed nearly a decade later the bathroom shelf in the foreground presents a dazzling treasure trove: ruby hairbrush, golden bottle, emerald stopper. The wall behind is a fiery Indian yellow, streaked with orange and pale green. Bonnard’s white shoulders retreat into the gold, but the hands are crimson and mauve, silhouetted against the light—and rising from them, the astonishing hot darkness of the head. As our eyes adapt, we make out all the colours that are stored in shadow: the vermillion ear alongside the apple-green jowl; the bristle of blue eyebrow and moustache; and on the forehead, burning, an impastoed highlight of brightest cadmium yellow. Photographs of Bonnard in his final years make him look strangely Japanese: sometimes a sage; sometimes, as here, the shabby, grief-stricken penitent of Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 film Ikiru.

Pierre Bonnard, Self-Portrait, c.1938-40

His last self-portrait dates from 1945, some eighteen months before his death. The face has become a Noh mask; the eyes, empty greenish-black slits, the darkest notes in the picture. Everywhere, the brush has been supplemented by the artist’s fingerprinting, yellow and white, blobs and smears of an unmatched tenderness. The bathroom’s tiles are now painted so fluidly we could be in an aquarium. A visionary dissolving—a watery, boneless melting of all division—pervades Bonnard’s last paintings; as though the fabled Age of Gold really has come round again; and with it a new, more fluid and vulnerable self has come into being.

Pierre Bonnard, Self-Portrait, 1945

TIMOTHY HYMAN: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments