Dora Maar – The Young Photographer 1930-35

Mary Ann Caws

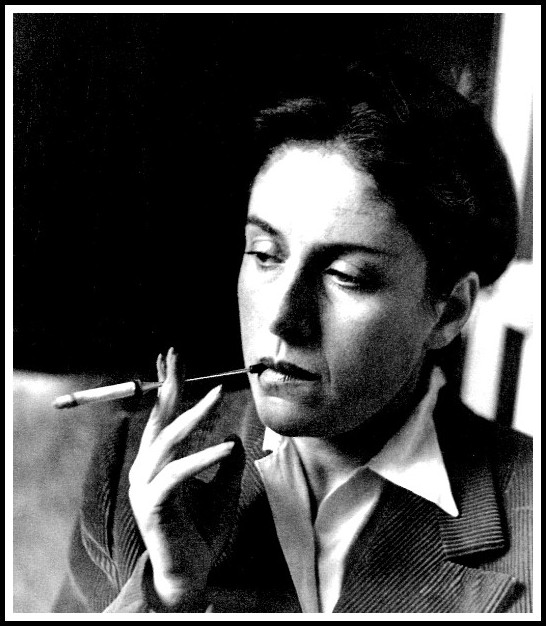

Man Ray’s portrait of Dora Maar, taken in1936, suggests the sphinx-like sophistication of this woman who lured Picasso by her solitary games with a penknife across the Café des Deux Magots.

DORA MAAR – THE YOUNG PHOTOGRAPHER 1930-35

Mary Ann Caws

From Mary Ann Caws, Dora Maar With and Without Picasso: A Biography (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000) pp. 18-54

Posted by kind permission of Mary Ann Caws, Distinguished Professor Emerita of Comparative Literature, English, and French at the Graduate School of the City University of New York.

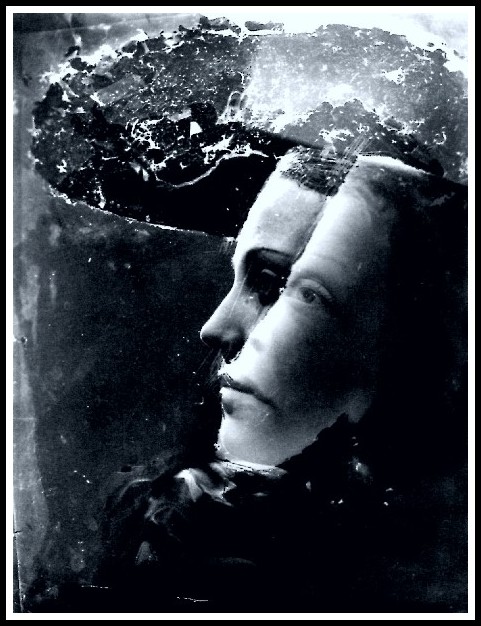

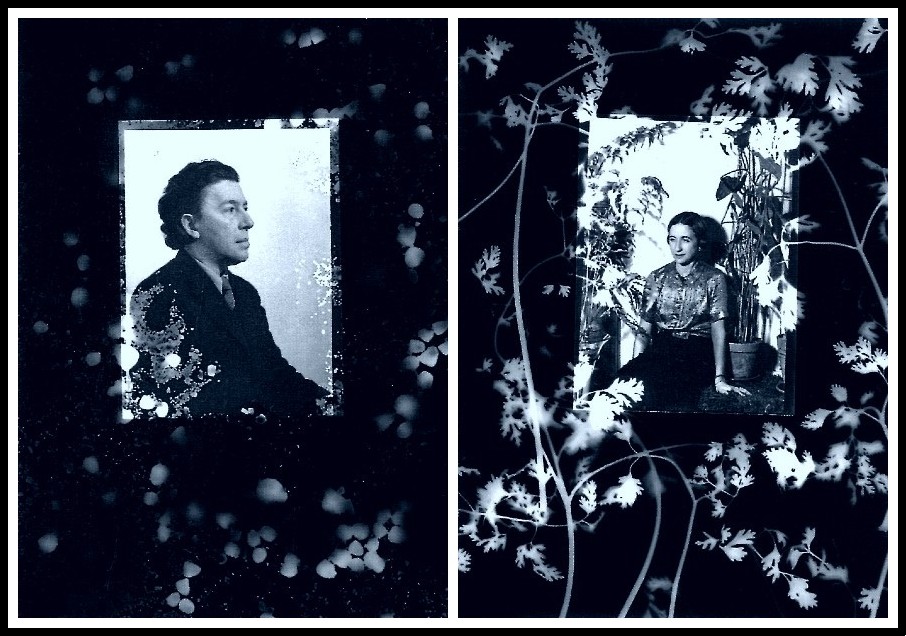

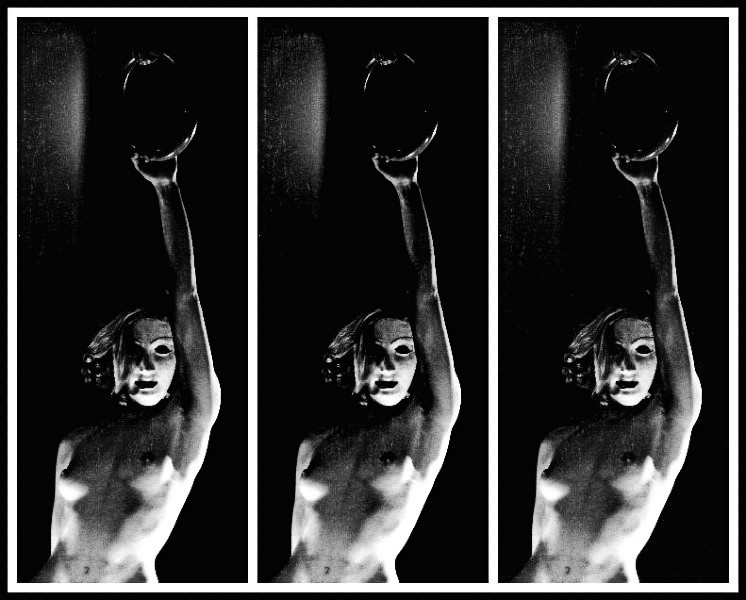

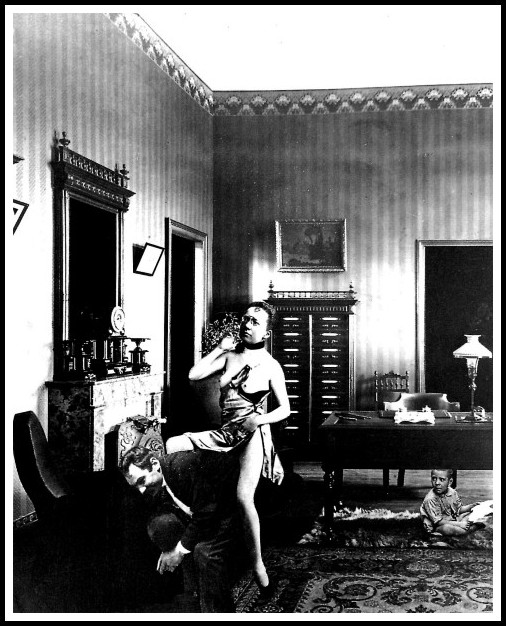

Dora Maar, Photomontage, early 1930s

I. EARLY EXPLORATIONS & FIRST YEARS AS A PROFESSIONAL

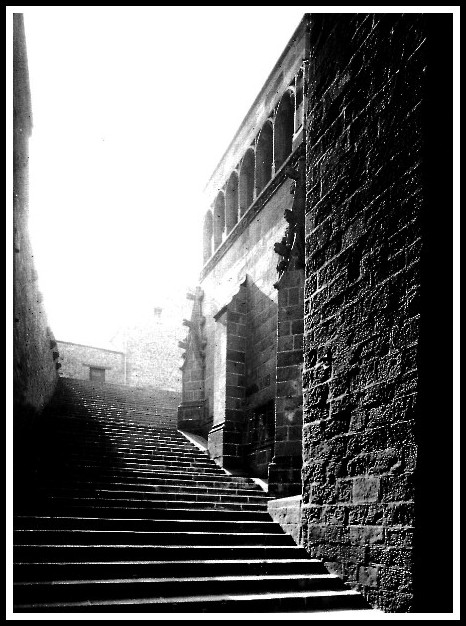

In 1931 Dora Maar photographed Mont-Saint-Michel for an illustrated book by the art critic Germain Bazin. Her pictures, made in partnership with Pierre Kéfer, another young photographer, capture the sense of mystery that pervades the island monastery, seen upon its rocks against the sky. They concentrate on the play of angles and shadows and on sharply plunging perspectives caught in the downward fall or the vertical ascent of the flight of steps, leading into a sort of nothingness, like the beginning of a good mystery. A drama of desertion permeates Mont-Saint-Michel, and these photographs give the feeling of abandonment, sensed in those lonely walls against the open heavens. Humour is also at play: above the fabled and dangerous inrush of tides, she and a fellow photographer (probably Kéfer) spoof themselves and their tricks in a picture that shows them apparently about to fall off the edge—clutching their cameras, of course.

Dora Maar & Pierre Kéfer

The power of Dora Maar’s photography often arises from her feel for plunging perspective. It is particularly effective in her rendering of a rainswept Paris, photographed from high above the treetops. She captures the mysterious, in a combination of the unresolved and the sharply angled. This frequently creates a sense of ambiguity, even menace. Objects jut out across the field of vision or the view plunges downwards in a way that owes much to the tradition of Japanese prints, such as those of Utamaro and Hiroshige.

Like many of Dora Maar’s photographs, these late-1920s shots of Paris after heavy rains owe their impact to sheer perspective.

Dora Maar set up a studio with Pierre Kéfer in the early 1930s. Kéfer had previously worked as a set designer: he created the sets for the film The Fall of the House of Usher, directed by Jean Epstein and Luis Buñuel in 1928. Their first studio was in the garden of the Kéfer family residence at Neuilly, but they soon moved to their own premises at 9 rue Campagne Première, in the fourteenth arrondissement, in the vicinity of Raspail-Montparnasse. They were lent this space by a mutual friend, Harry Ossip Meerson, a Pole who was to become an American citizen and a famous fashion photographer for Paris-Magazine; he would eventually join his brother, the art director Lazare Meerson, in Hollywood. In exchange for the loan, Dora Maar helped Meerson retouch his photographs, sharing the darkroom with the Hungarian-born photographer Brassaï. He was already famous by that date, and Dora Maar was an admirer of his work. This meeting marked the beginning of an acquaintance that lasted well into the 1940s, throughout and beyond her years with Picasso. In 1931, art historian Germain Bazin commissioned Dora Maar and Pierre Kéfer to take a series of photographs of Mont-Saint-Michel to illustrate his book about the island monastery. This was one of her first jobs as a professional photographer.

Dora Maar, Mont-Saint-Michel, 1931

Through her connection with Marcel Zahar, an art historian and critic, Dora was introduced to Emmanuel Sougez, whom she would always regard as her mentor. Louis-Victor Emmanuel Sougez (1889-1972) began his career with publicity and archeological photography. He was one of the founders of the important magazine L’Illustration and in later years an influential historian of photography. In the 1930s he was a prominent spokesman in France for the New Photography. This international movement rejected what its practitioners saw as the sentimental and painterly photography of the past in favour of a much starker and more realist aesthetic. In Germany it was called the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity; the Group f.64 in the United States shared similar objectives.

Dora Maar, Autumn Trees on a Riverside, 1927

In France, where pictorialism and tradition remained strong, the strictness of this new northern style (which flourished first in Holland, Belgium and Germany) met with a certain resistance. Sougez studied in Germany and Switzerland, and back in France, along with Florence Henri, became a leading advocate of the new school, while at the same time remaining vocal in his support for French photography within the highly international artistic community of Paris. As a professional practitioner, Sougez worked a great deal in advertising and publicity. He was also known for his large-scale still-lifes of ordinary objects, including piles of rags and cords, which typified the New Photography’s emphasis on directness of vision, on materials, and on the beauty of everyday and manmade objects. When Dora Maar returned to painting in 1937, she was often to focus on a single mundane object in just this style.

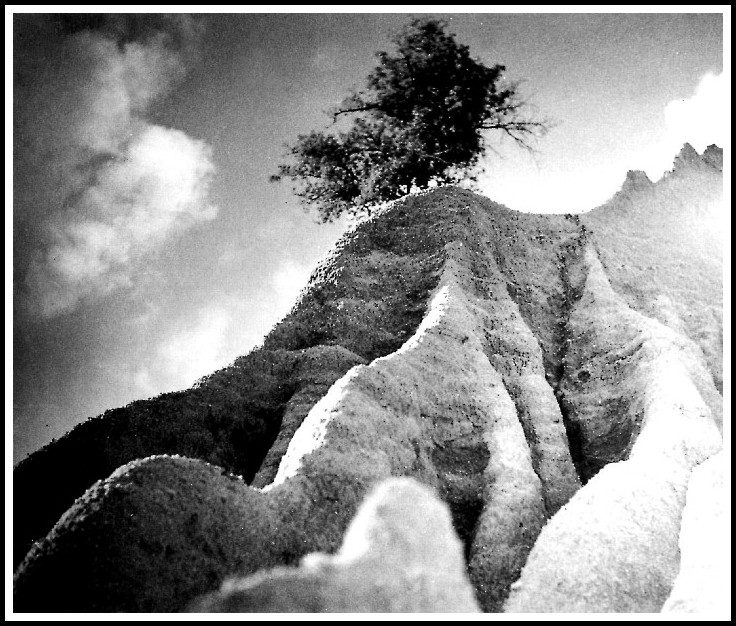

Dora Maar, Rock Formation, late 1920s

II. ADVERTISING & ‘NEW PHOTOGRAPHY’

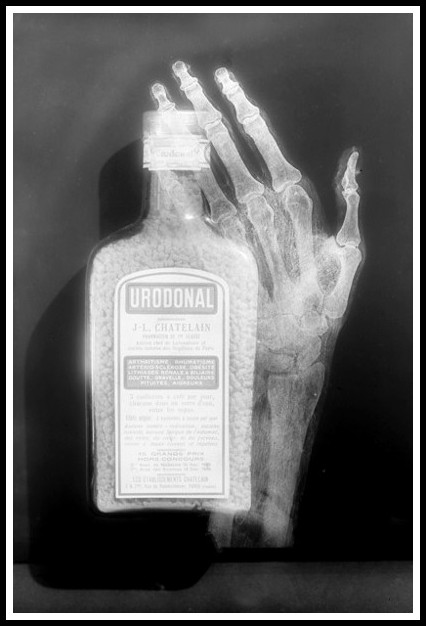

Dora Maar was also fascinated by the technical innovations of the contemporary avant-garde: shifts of viewpoint, plunging perspectives, photomontage, and deformations produced during the shoot or in the darkroom. Commercial photographers made use of all of these techniques. In advertising, atmosphere was often given greater weight than the product itself, as in an influential advertisement by Sougez for Urodonal (an anti-arthritis medicine), which made high drama from the x-ray of a hand.

Emmanuel Sougez, Urodonal advert, 1930

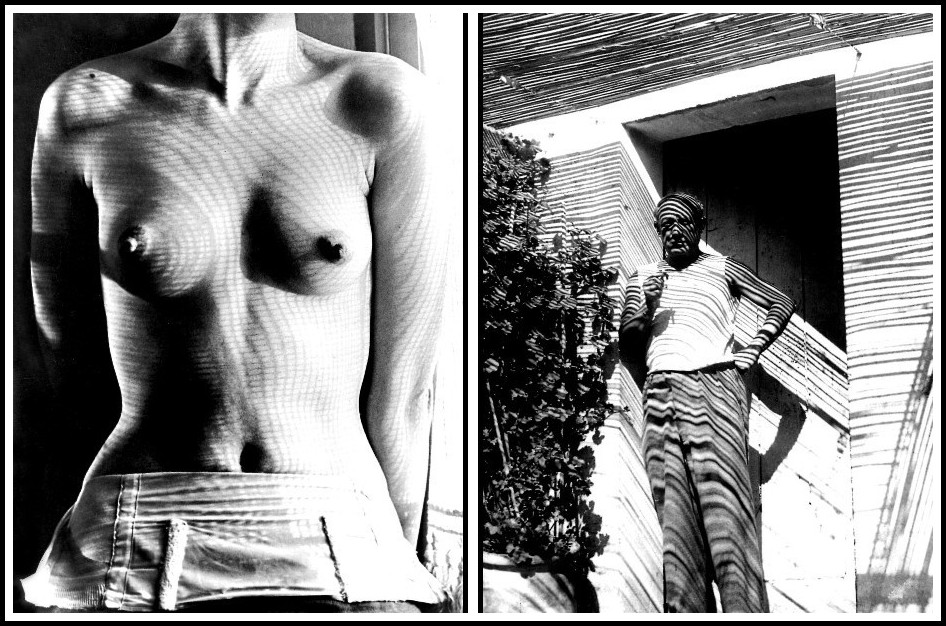

By 1929-30, just as Dora Maar was embarking on her career, the New Photography was at its height in France. When she was hesitating between painting and photography, Sougez was among those who recommended she continue as a photographer, and his was a persuasive voice. Impressed with her talent and her beauty, he helped her locate the best sources from which she could purchase cameras, projectors and other equipment. In an interview with Victoria Combalia, Dora recalled that on leaving art school she had approached Man Ray and asked to be his assistant. His response was to claim that he never used assistants (facts to the contrary — Lee Miller and Berenice Abbott were particularly successful examples), but he did promise to be at her disposal if ever she needed advice. During her years as Picasso’s lover, she was to become well acquainted with Man Ray, and some of her photographs are strongly reminiscent of his. The striping sun and shadow of her images taken in the gardens of the Hôtel Vaste Horizon in Mougins, where she and Picasso stayed in 1936 and 1937 with André Breton, Roland Penrose, Lee Miller and others, recall Man Ray’s photographs of Lee Miller with sunlight striping her nude torso through a blind.

Man Ray, Lee Miller, 1930 | Dora Maar, Picasso at the Hôtel Vaste Horizon, 1936 or 1937

In the 1930s Emmanuel Sougez was the leading spokesman in France for the New Photography movement. He was also a friend and mentor to Dora Maar, urging her to pursue photography professionally.

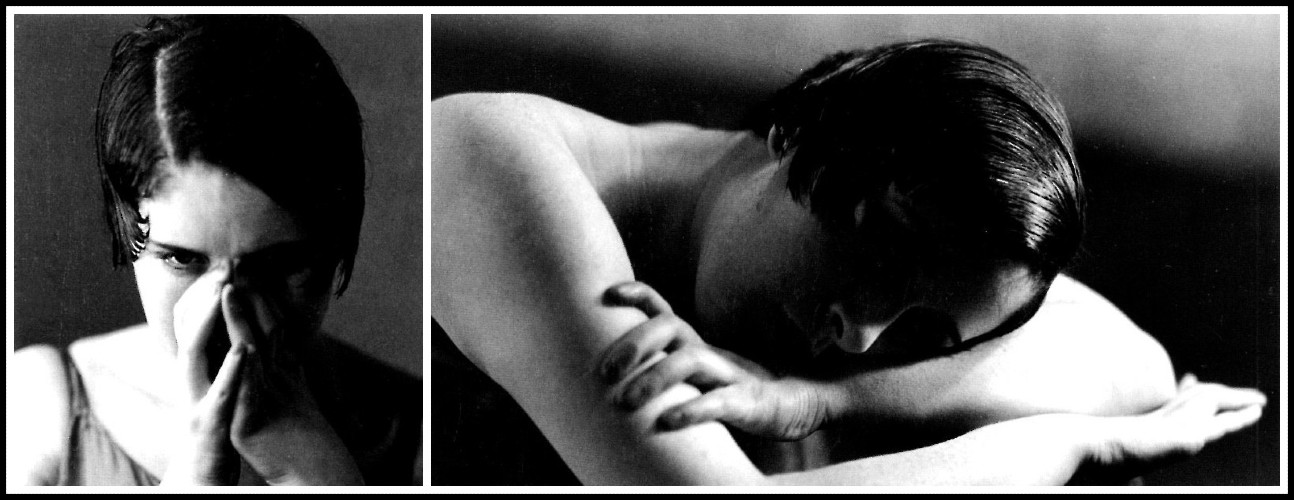

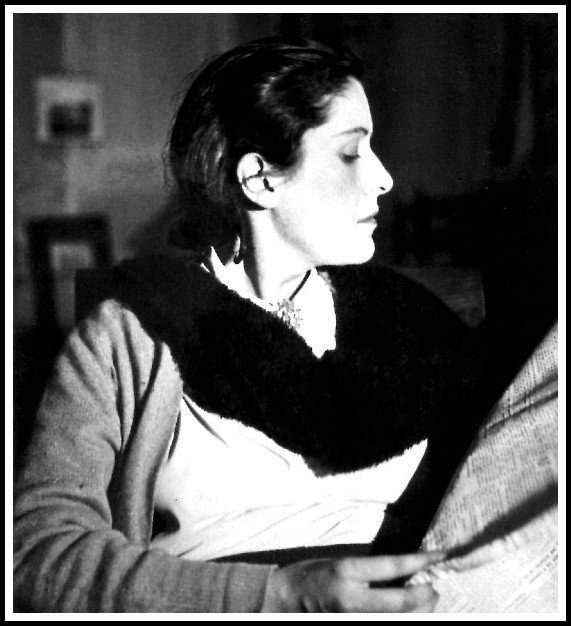

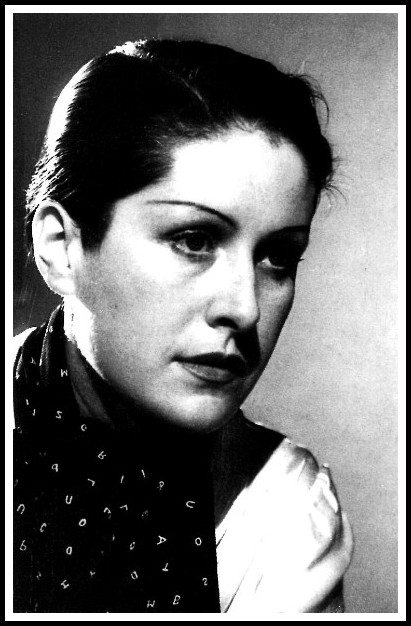

Anonymous photographs of Dora Maar in her student days, her hair fashionably cropped and parted.

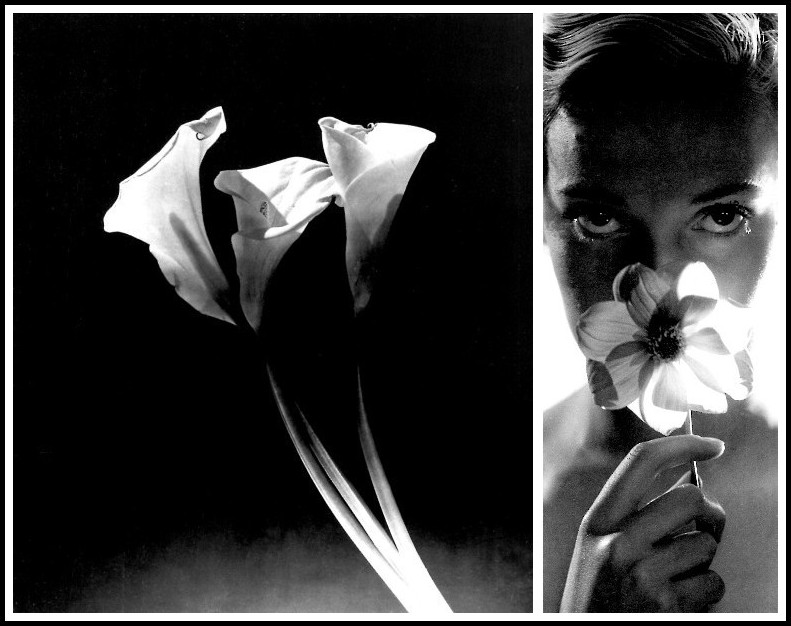

Close-ups of plant-heads, seeds or flowers were one of the genres that flourished during the years of the New Photography. Dora Maar’s expressive flower studies, delicate compositions of light and shade, have a sensuous, luminous quality.

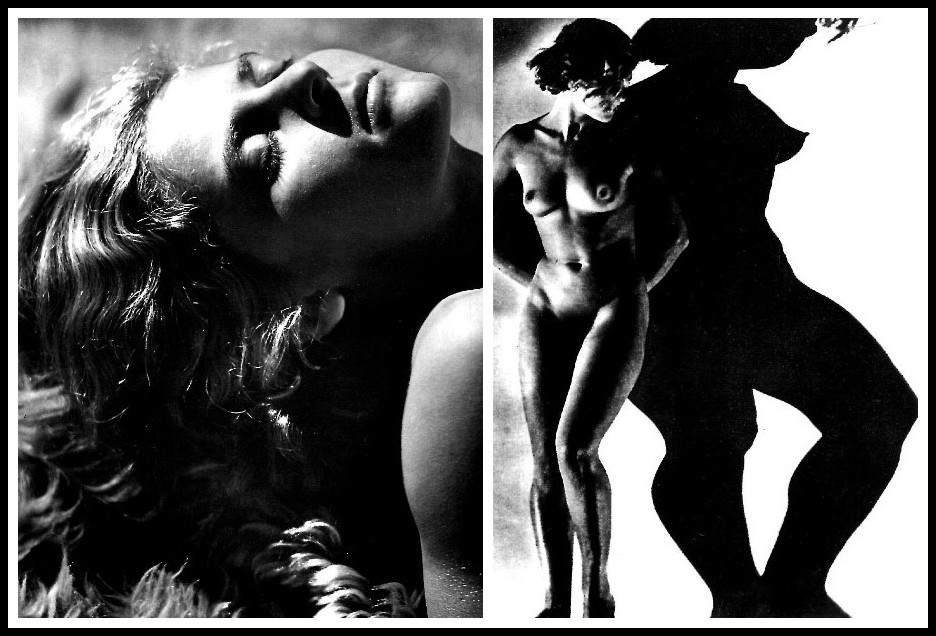

Dora Maar, Arum Lilies, 1930 | Dora Maar, Assia, 1934

Brassaï recollected Dora Maar in these early days in her long white coat, a true professional already and always, stalking about her subject as a huntress around her prey as she searched for the most telling detail. Later, in the autumn of 1935, Brassaï described her as having ‘bright eyes and an attentive gaze, a disturbing stare at times’. ‘Sometimes we had a show together,’ he recalled. When she became Picasso’s companion, she also became his photographic collaborator. Brassaï found her watching ‘jealously over this role that she considered as a prerogative and assumed moreover with diligence and talent. She was the one who photographed his sculpted stones, some of his statues, helped him in his photographic experiments in the darkroom. So as not to provoke her sensitivity, inclined as she was to storms and outbursts, I was very careful not to tread on what was from now on her domain.’

Picasso, Dora Maar in Profile, 1936

Her association with Brassaï brought Dora Maar into contact with many photographers and photojournalists. She thrived in the atmosphere of collective excitement of these years, as she would in that of the Surrealists. She maintained a fierce intensity in all the work she did, public and private: in her portraits and her still lifes, in her photography and her poetry. This was heightened by the strain she constantly put herself under, in her career and her emotional life. For she was, by all accounts, as intense a personality as her later lovers: Georges Bataille, no less than Picasso, was a notorious bundle of contradictions and ferocities. There was in all Dora Maar’s relationships and her work an authenticity as disquieting, sometimes as off-putting, as it was admirable. She could be extreme, even absolutist in her most private emotions. One poem of this period reads: ‘Here are our fates face to face / we shall love each other reverently.’

Anonymous, Dora Maar, 1935

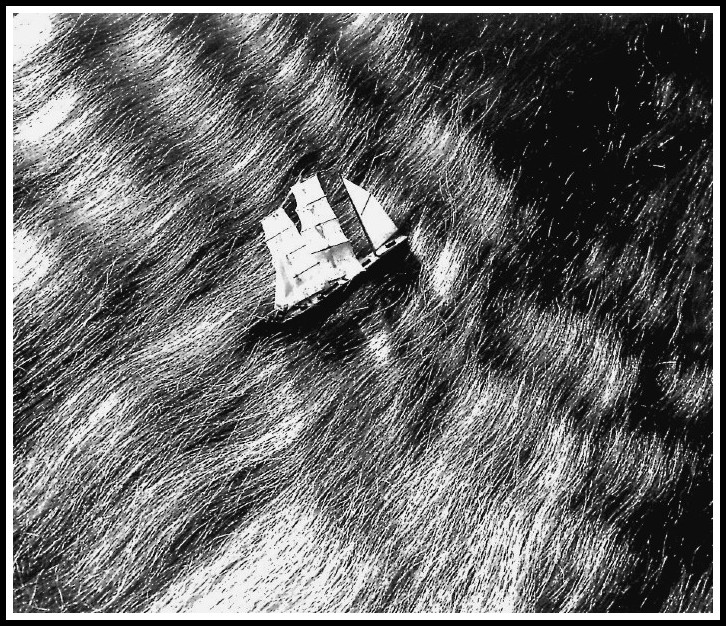

Some of Dora Maar’s own works of these years, particularly her photograph of Arum Lilies of 1930 and other flower studies, are in accordance with the aesthetics of the New Photography. Her close-ups can be as startling as the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, as if they took up all of the viewer’s breathing space. One of the most effective publicity photographs turned out by the Kéfer-Dora Maar studio, advertising a hair oil, shows a miniature ship gliding diagonally up a mane of thick, smooth hair, as if borne upon the waves.

Pierre Kéfer-Dora Maar, Study for Pétrole Hahn advert, early 1930s

Dora Maar also made photograms (or rayographs), the technique invented by Man Ray in which he made images without a camera by placing objects directly onto light-sensitive paper. She made these alone, and later in collaboration with Picasso, concentrating an intense gaze on one object from a plunging perspective, or on its transformation by superimpression. The technique recurs in her photographs from beginning to end: in the 1980s, without the benefit of instruments of any kind, she rediscovered her early fondness for manipulating photographic images and superimposed some of her old portraits with crystals, parsley and corn kernels. Her contact in the 1930s with great photographers and the worlds of photojournalism and photo-publicity exerted an indelible influence all her life. In the 1980s, when she was in her seventies, she returned to her old craft of photography. She resumed the photogram technique that she had practised in the 1930s, placing corn kernels over an old portrait of André Breton and sprigs of parsley over a portrait of Lise Deharme. She was fascinated by her Polaroid camera, and took many pictures with it, including of her assistant Rose Toro Garcia. ‘I was a famous photographer’, she told Rose proudly.

Dora Maar, André Breton & Lise Deharme, 1980s

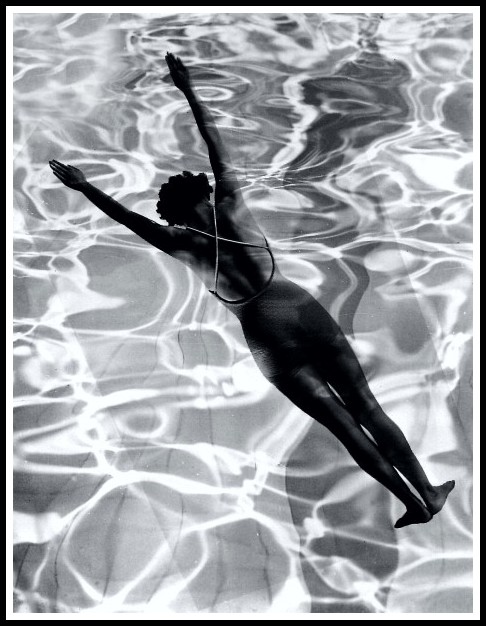

Pierre Kéfer and Dora Maar’s productions bore their joint signature: Kéfer-Dora Maar. In the centre of their studio there was a pool, subject of a notable photograph in which the sun beats down and casts a moiré pattern on the water and on the bathing suit of a stretched-out model. Her body in its dark suit is a sweep of stillness against the texture and ripple of the pool, poetic and paradoxical. There is a sense of high adventure in these pictures, including those commissioned for advertisements and fashion magazines, and in the ideas they provoke in the observer’s mind.

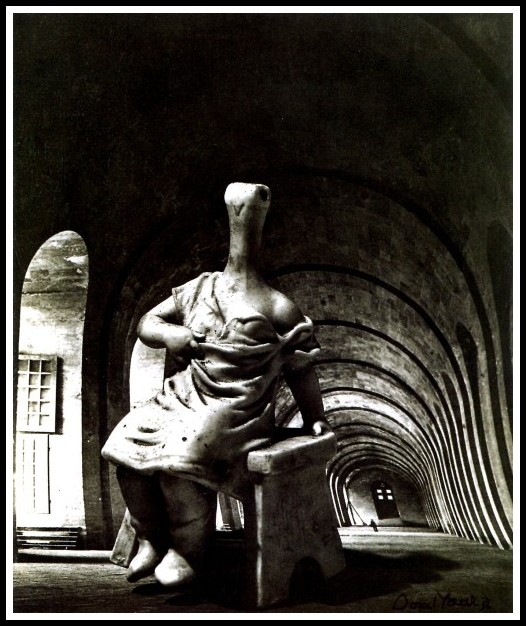

Dora Maar, Photomontage, 1935

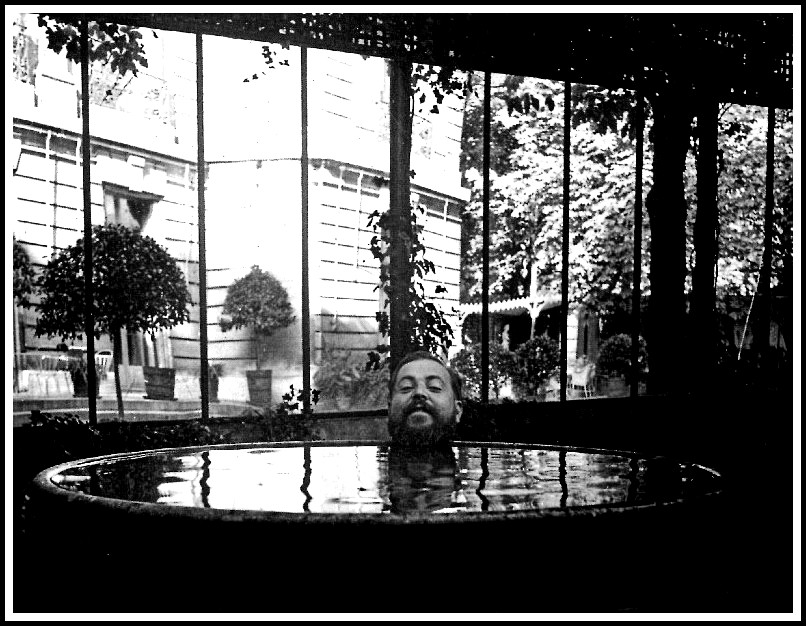

At the Paris home of Marie-Laure de Noailles—in future years a close friend of Dora—she pictured the artist and designer Christian (‘Bébé’) Bérard with his head appearing to float above the water of an ornamental cistern. The pose is described by Michael Kimmelman as ‘wry and mischievous, with only his head perceived above a fountain, as if he were John the Baptist on a silver platter’.

Dora Maar, Christian Bérard, early-mid 1930s

III. FASHION & EROTICISM

Dora Maar and Pierre Kéfer also took portraits of such beauties as Assia, the celebrated model of the Surrealists.

Dora Maar, Assia, 1934

Assia, nude, mysteriously masked and hanging from a gymnast’s ring in a photograph of 1934. Dora Maar worked to commission not only for conventional fashion magazines but also for erotic reviews such as Beauté et Sex Appeal. This may have been destined for such a publication.

Dora Maar, Assia, 1934

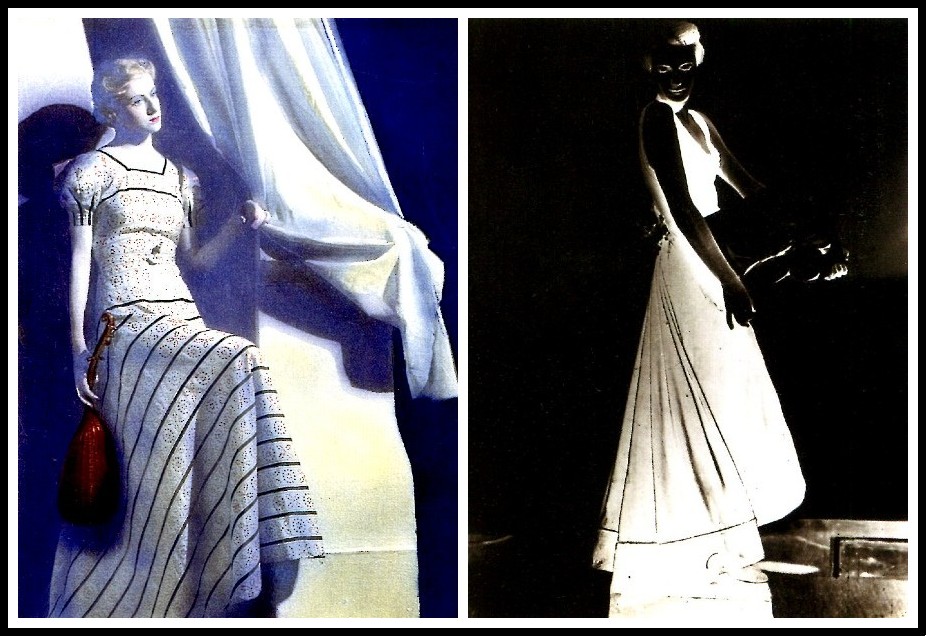

Dora and Pierre Kéfer’s fashion photographs have a sophisticated wit and inventiveness. In one a star replaces the model’s head and looks out on the starry night a double play on the idea of stardom.

Dora Maar, Fashion photo, 1936

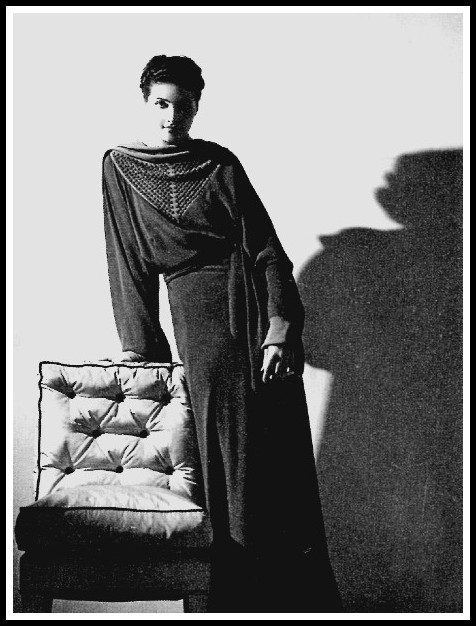

A model in a simple black dress takes a provocative pose beside the padding of a cushioned, buttoned chair: the furniture is buttoned down, but she seems not.

Dora Maar, Fashion photo, early-mid 1930s

Objects appear to dream along with the models. The draped dress of a woman holding a mandolin echoes the drape of a curtain; the sound of mandolin music seems to accompany her reverie. Elegantly inventive fashion photography was a staple of the Kéfer-Dora Maar studio. Their pictures were commissioned by a variety of magazines, including Madame Figaro and Magazine Beauté. Dora Maar continued to produce this kind of work after she and Kéfer parted company in 1934. The model with a mandolin, a hand-colored print, was made in 1936, when Dora Maar was working independently from her own studio at 29 rue d’Astorg.

Dora Maar, Fashion photos, 1936

IV. 29 RUE D’ASTORG

The Kéfer—Dora Maar studio closed in 1934. Dora Maar had always been on good terms with her father and he now provided her with the money for her own studio and dark room at 29 rue d’Astorg, in the eighth arrondissement, near the church of Saint-Augustin. Its address was to become the title of one of her most famous Surrealist photomontages. It was, by chance, near Picasso’s apartment on the rue la Boétie and next door to the Galerie Simon at 29 bis rue d’Astorg, owned by Picasso’s dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (who chose the name Simon because his own sounded too Jewish). Since the family’s return to Paris in 1926, Dora had met up with her father every Sunday for lunch at the Lutétia, near Sèvres-Babylone. Monsieur Markovitch was a fussy and irascible client, and his failure to find fault with a meal was rare. Indeed his vociferous complaints were so much the rule that the head waiter at the Lutétia would simply respond with gestures of resignation, sighing ‘Monsieur Markovitch is always right.’ Dora found this funny, but acknowledged her father’s ‘tyrannical and captious temperament.’ Without the studio he gave her, however, she would have been forced to take on commissions instead of pursuing her creative work, and for that she was grateful.

Dora Maar, 29 rue d’Astorg, 1936

V. STREET PHOTOGRAPHY – LONDON, PARIS, BARCELONA

In the early 1930s, the period in which Dora Maar’s photographic work was at its finest, she was politically aligned with the Left. Her images of street life in Barcelona, Paris and London, of the poverty-stricken, the lame, the blind and the down-and-out, mark clearly her interest, personal, artistic and political. Dora Maar travelled alone to Spain in 1934. The country offered splendid subjects for photographers and her friends made many suggestions of where to go; but she had, as always, her own ideas. Her first destination was Tossá de Mar on the Costa Brava, where the sun beat down heavily, and where many of her photographs were overexposed and had to be discarded. But her pictures of Barcelona have survived. They show, as do those taken in London that same year, her attraction to what might seem the antithesis of her fashion and avant-garde photographs: the street life of modest, often impoverished people. The contrast between these approaches reflects what the Parisian intellectual Bernard Minoret sees as the constant pull between the two sides of her character, between her exuberance and her self-constraint. Dora Maar’s street photography—taken in Barcelona, London and Paris—combines a strong sense of social justice with an eye for the uncanny and for inadvertent humour.

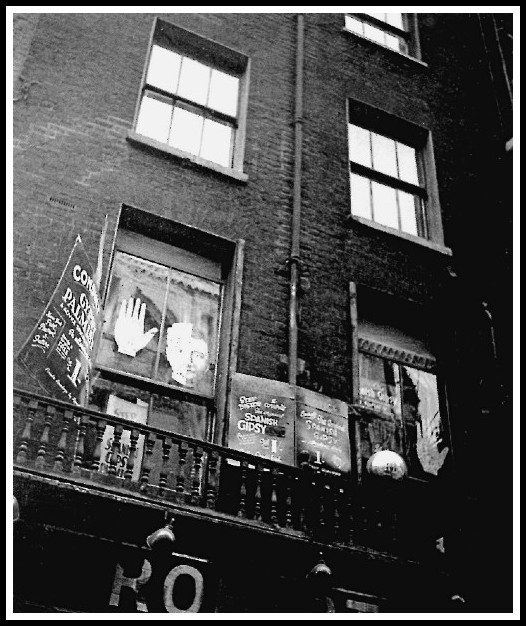

Dora Maar, Consult the Gypsy, London 1934

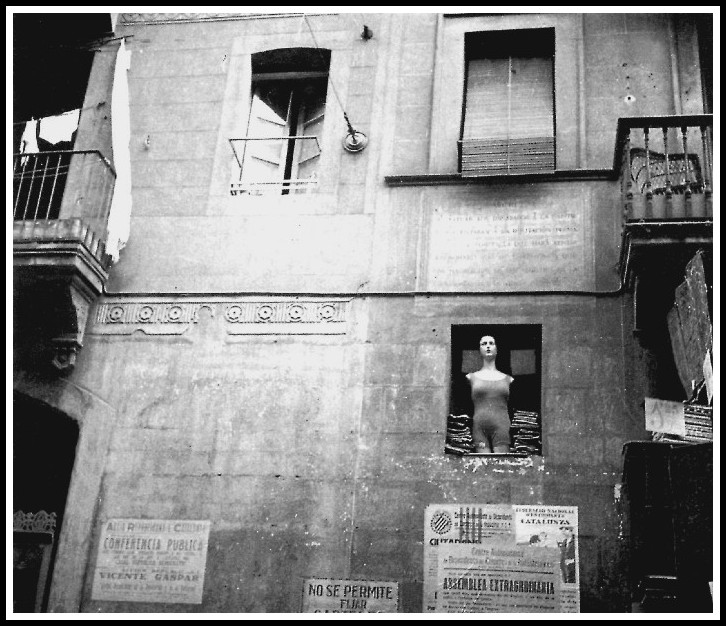

Dora Maar was especially apt to seize on the ironies and mysteries of the street. In Barcelona, a wall bears posters announcing a lecture and a public gathering either side of a sign clearly forbidding the sticking up of posters. The inadvertent humour caught here does not trouble the lonely mannequin, armless and hairless, who calmly surveys the street from on high in her underwear, flanked by piles of old papers. The photograph, with its shutters and blinds, gives a strong sense of the hidden and the exposed, of what you can see and what you cannot depending on where you are placed.

Dora Maar, Barcelona, 1934

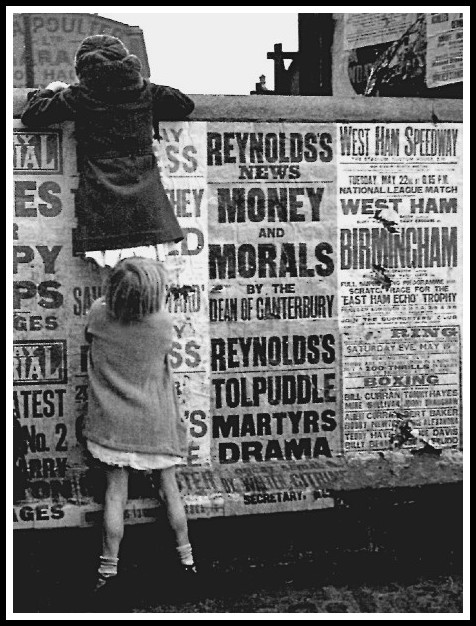

In Money and Morals two little girls clamber up to peek at something out of sight, innocent of the weighty words posted around them. Dora Maar’s fascination with sight and the absence of it, things open and closed, determines what she sees and what she permits us to see. Blindness—literal or metaphorical is ever-present in these images.

Dora Maar, Money and Morals, 1934

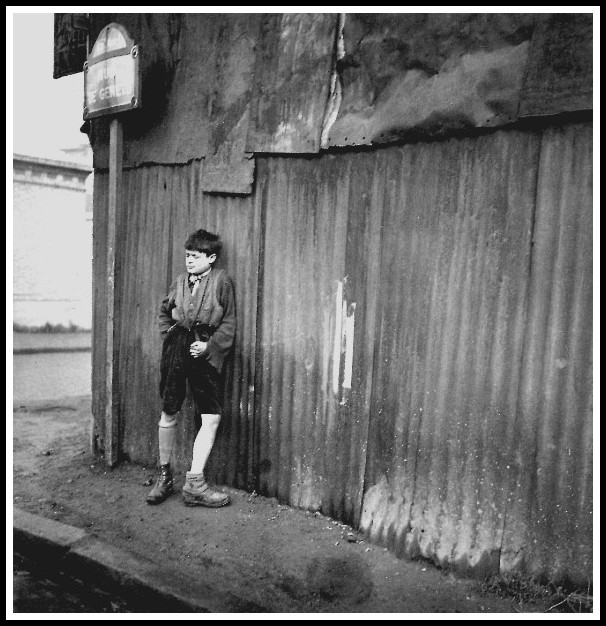

Her pictures of poverty seize the desperation and desolation of the Depression. A ragged Parisian urchin with one sock falling down around his ankle strikes a defiantly nonchalant pose. Dora’s sense of justice is powerful and her photographs make a clear moral statement, sometimes leavened by humour.

Dora Maar, Rue de Genets, Paris 1933

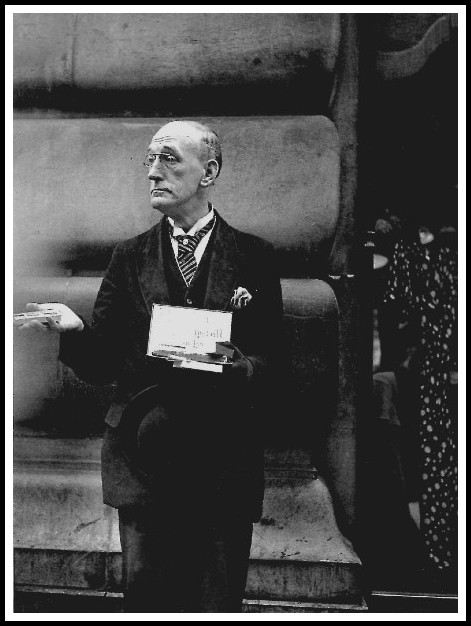

In London she continued to photograph the paradoxes of poverty and wealth. What the crash of a business enterprise can do to the spirit is all too clear in No Dole: the gentleman in his suit reduced to selling matches on the street projects a terrible contrast of garb and occupation.

Dora Maar, No Dole, London 1934

VI. EROTICISM

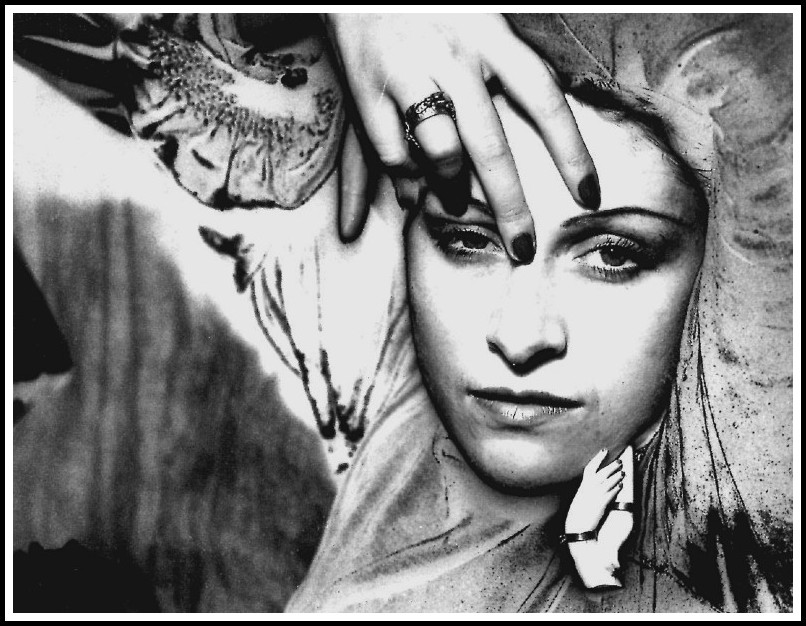

Man Ray’s famous solarized portrait of Dora Maar was taken in 1936. Dora approached Man Ray and asked to be his assistant when she first left college, but he declined. By the time she met him again through the Surrealist circle, she had gained considerable sophistication and allure. Like Picasso, Man Ray was fascinated by the erotic aura of her perfectly manicured hands.

Man Ray, Dora Maar, 1936

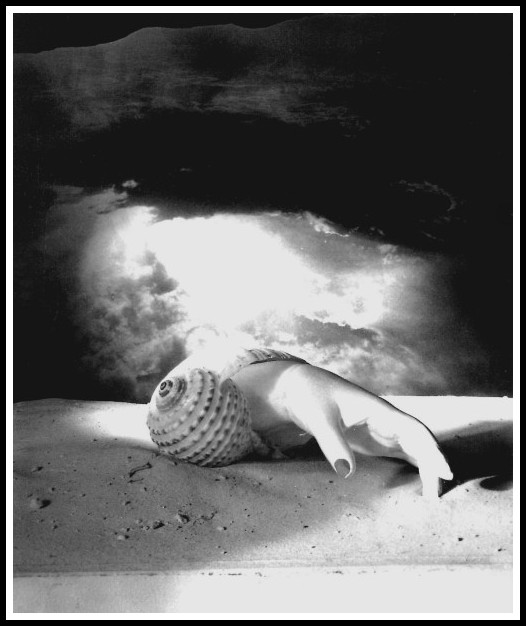

The violent sensual impact of an unexpected visual combination, particularly that of the human and natural worlds, is perfectly illustrated by Dora Maar’s remarkable image of a miniature artificial hand emerging from a conch shell, its finger poking languorously into the sandy surface. The very slowdown or delay felt in the touch is monstrously erotic, while the heavy play of cloud and light in the heavens above gives this monstrousness a strange weight. The painted fingernails remind the viewer of Dora’s own brightly painted nails–red, green or black. Her most famous Surrealist photographs date from 1935-36, but Dora Maar was already making arrestingly strange images a couple of years before that. This photomontage creates an eerie sense of time slowed down, as the hand emerges from the shell to finger gently the sandy surface under glowing light filtered through lowering clouds.

Dora Maar, Untitled, 1933-34

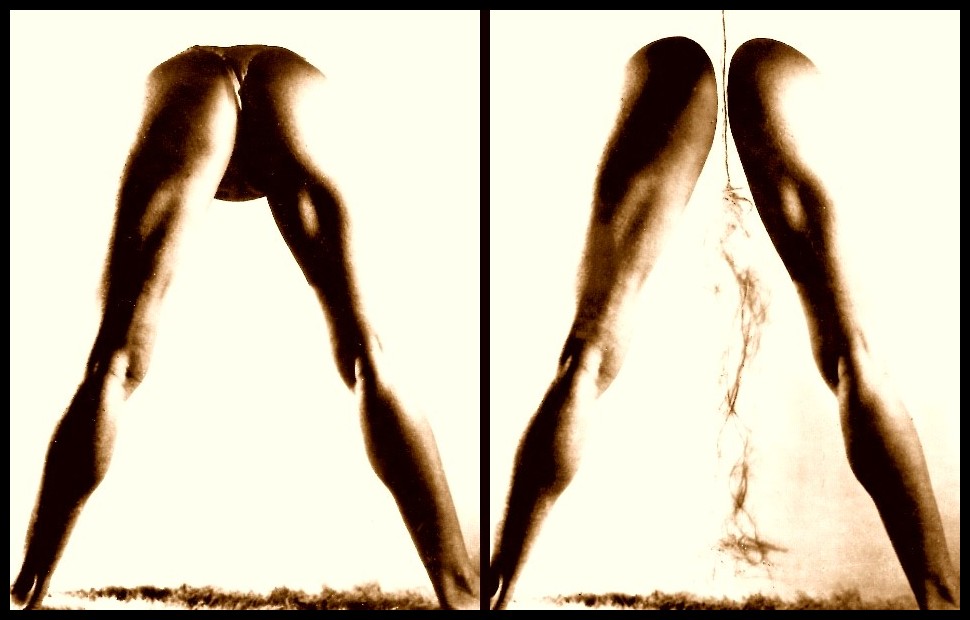

Anatomically frank and strikingly erotic, this remarkable pair of images demonstrates a very daring eye and lens. With their triangular openings and the smoky intrusion in the second print, they invoke both the human and the animal.

Dora Maar, Legs I and II, 1935

Dora Maar was a highly independent, unconventional, flamboyantly dressed young woman, fully in control of herself and aware of her magnificent talent as a photographer. She had an appetite for mysticism and transgression. In the mid-1930s she produced a great deal of photography for erotic magazines. Douglas Cooper described her as ‘always spirited and provocative but already utterly self-possessed, aged twenty-six or so.’ Transgression clearly appealed to her. Her conceptually scandalous photographs are like so many dangerous experiments. In Forbidden Games the erotic thrill is intensified by the child voyeur watching on the sidelines, hiding under a table and witness to the scene. The riding lady keeps her spectacles on and her neck ribbon neatly in place as she perches atop a smartly suited man. The image invokes the old tale of Phyllis riding Aristotle, the wise philosopher mastered by his domineering wife, a favourite misogynist motif of Medieval and Renaissance art. Many of these photographs are heavy with transgressive erotic play, and with the ironies such consciousness exploits. The child voyeur peeping out from under the table adds a disturbing dimension to an otherwise preposterous satire on bourgeois respectability. The boy is taken from one of her Barcelona street photographs; the woman’s body is that of a dancer at the Folies-Bergère, with a mannish, bespectacled head tacked on. The scene is played out in a heavy bourgeois turn-of-the-century interior.

Dora Maar, Forbidden Games, 1935

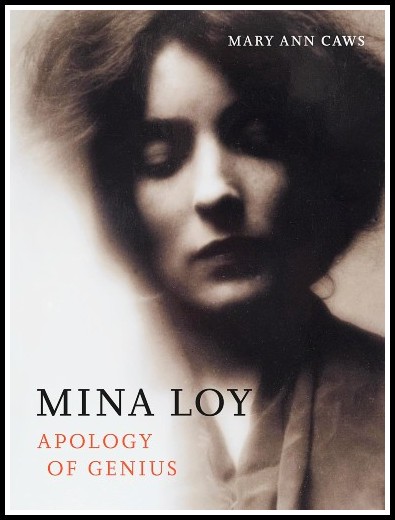

MARY ANN CAWS: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

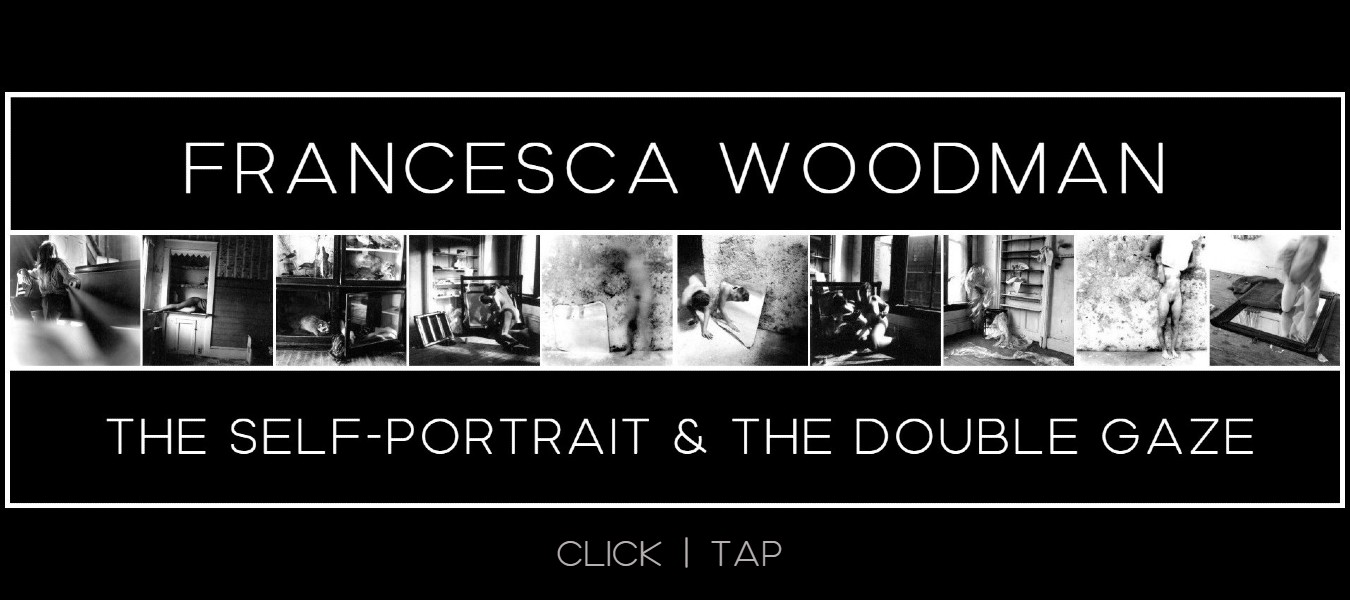

DORA MAAR IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel, ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 11

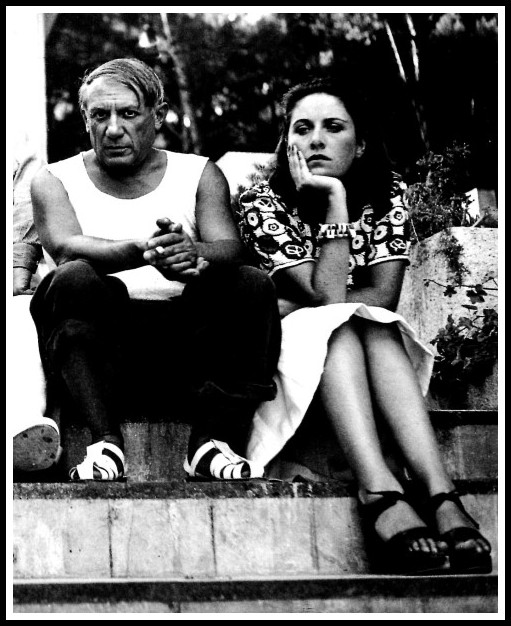

̶ Imagine her jet-black hair and ruby-red nails, her glowing skin and dark eyes; imagine the flash of the dagger as time and again she stabs it between her fingers. Picasso wanted to change his life, he was ready to fall in love. That afternoon on the terrace of the Deux-Magots was when Dora Maar seduced him.

Over the meal, we spoke of the master and his mistress: In your purse you’d discovered a bookmark from the Picasso Museum in Barcelona.

Izis, Dora Maar, 1946

̶ What I don’t get, Sprague, is why as soon as his women got close to him, he turned them into doormats.

̶ They weren’t all like Dora Maar. Françoise Gilot never let him wipe his shoes on her. And Jacqueline Roque always had the upper hand. She appealed to the worst in him, and it worked. She didn’t commit suicide until thirteen years after he died.

̶ And what about Marie-Thérèse Walter?

̶ She hanged herself four years after Picasso’s death.

̶ But Dora—

̶ She said, ‘After Picasso, there is only God’. She sought refuge in religion.

̶ What a man! But why did he go in for this goddess-to-doormat thing? Why would he need to abuse and humiliate?

̶ He had a genius for manipulation. Never allowed himself to be vulnerable, always insisted on complete control. What’s behind that, we’ll never know.

Man Ray, Pablo Picasso & Dora Maar, Antibes 1937