FRANCESCA WOODMAN: THE SELF-PORTRAIT & THE DOUBLE GAZE

ELISABETH BRONFEN

FRANCESCA WOODMAN: THE SELF-PORTRAIT & THE DOUBLE GAZE

Posted by kind permission of Elisabeth Bronfen, Professor of English and American Literature, University of Zurich

Global Distinguished Professor, New York University

From Elisabeth Bronfen, ‘Leaving an imprint: Francesca Woodman’s Photographic Tableaux Vivants’

in Gabriele Schor & Elisabeth Bronfen, ed., Francesca Woodman: Works from the Sammlung Verbund (Cologne: Walther König, 2014) pp. 11-31 (here pp. 19-23)

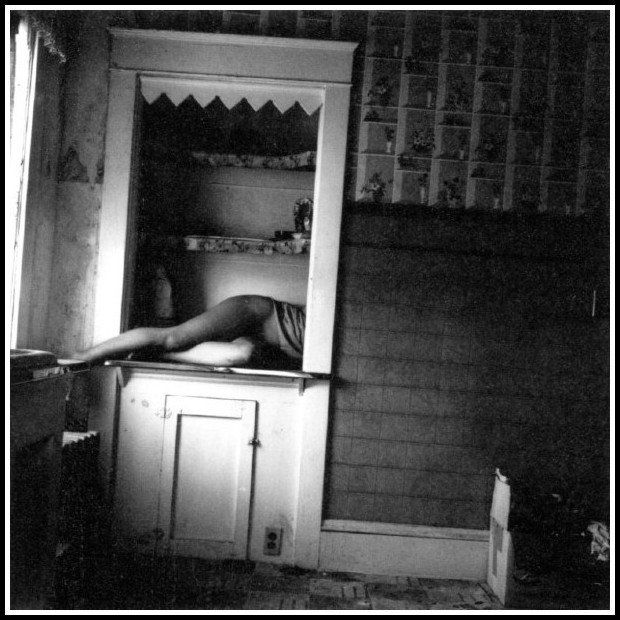

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, 1975-76

As John Berger already pointed out in the 1970s, the decisive feature of any female artist’s intervention in the genre of the self-portrait is the double gaze inherent in the way Western culture consistently compels women to think of themselves as objects of sight. Berger’s visual essay Ways of Seeing came out the same year that Woodman took the Self-portrait at Thirteen in which she resolutely turns her face away from the camera.

Francesca Woodman, Self-Portrait at 13, 1972

A woman, Berger notes polemically, is born into a confined space allotted to her by the male gaze. There she can develop, but only at the price of being split in two. She is accompanied by her own image of herself, having been taught and persuaded from childhood on to survey herself continually. To gage the effect her looks have, she must constantly watch herself. Berger’s point is that while men act, women appear. Men look at women, while women watch themselves being looked at by others, usually (but not always) men. Decisive for a female artist, who works with her self-image, is that this exchange of looks not only defines most relationships between men and women but also, and more importantly, woman’s relationship with herself: ‘The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object—and most particularly an object of vision: a sight’.*

* John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London, 1972), p. 47

John Berger, Ways of Seeing, p. 47 | Bettina Rheims, Sybil Buck, 1996

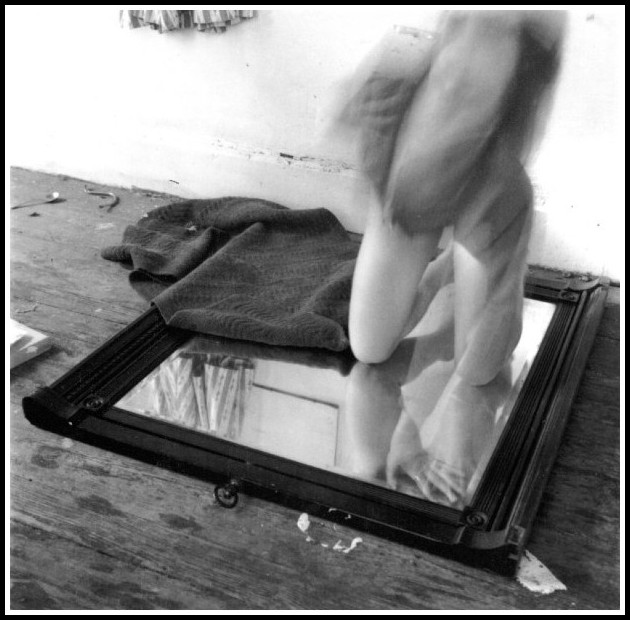

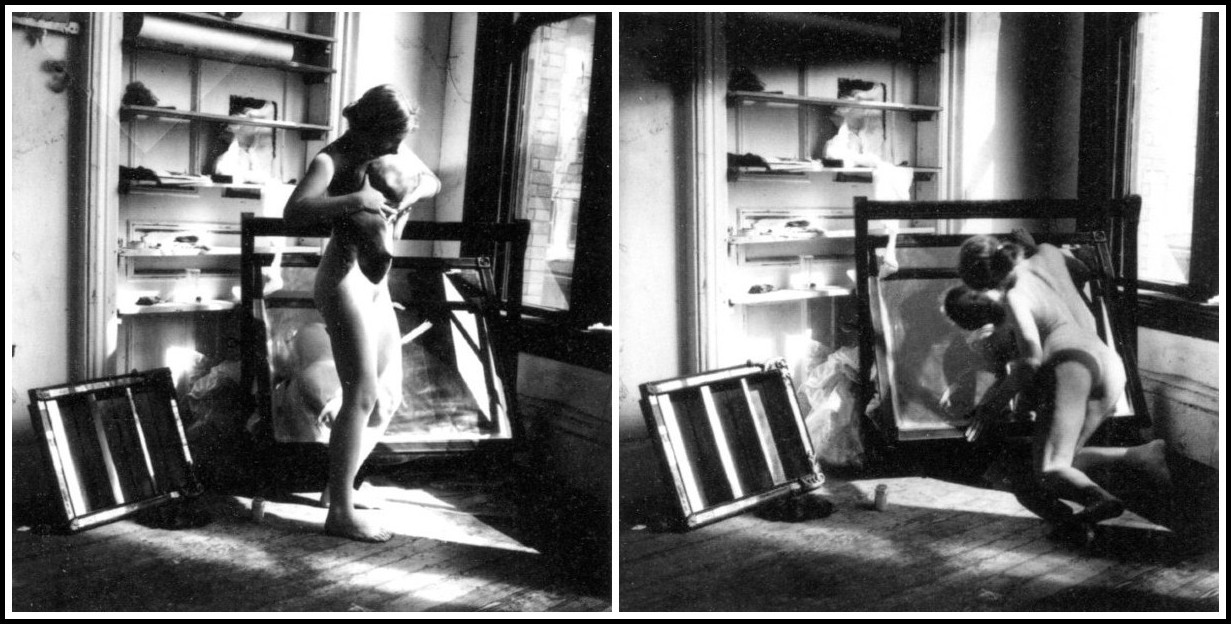

Any female artist must engage with this double gaze of herself, always aware of the effect she has for an implied viewer. At the same time, her self-determination consists in manipulating the way she is surveyed. She need not fully identify with a male encoded gaze, indeed, she may also ironically trouble it. In the photographic series A woman. A mirror. A woman is a mirror for a man, Woodman carries to an extreme art history’s conventional reduction of the female body to a sight meant to give pleasure to an outside viewer. Turning her back to the mirror, she holds a sheet of glass in front of her naked body as though, trying to squeeze herself into the frame, she were viscerally turning herself into an image. Yet her fingers, feet, and head stick out so that no unified sight emerges. Instead, our attention is explicitly drawn to the visual tension between the part of the body pressed flat by the glass and those body parts that fall outside the frame. In other photographs from the series, her movements and the play of light on the glass blur the contours of her body, such that it appears only as a distortion. The image in the cheval mirror moreover includes its exterior frame, so that in the photograph that shows Woodman calmly contemplating her own self-image like a female Narcissus, the blurry body in front of the mirror is reflected by a surface which, on the upper edge, offers a double frame.

Francesca Woodman, A woman. A mirror. A woman is a mirror for a man – I & II, 1975-78

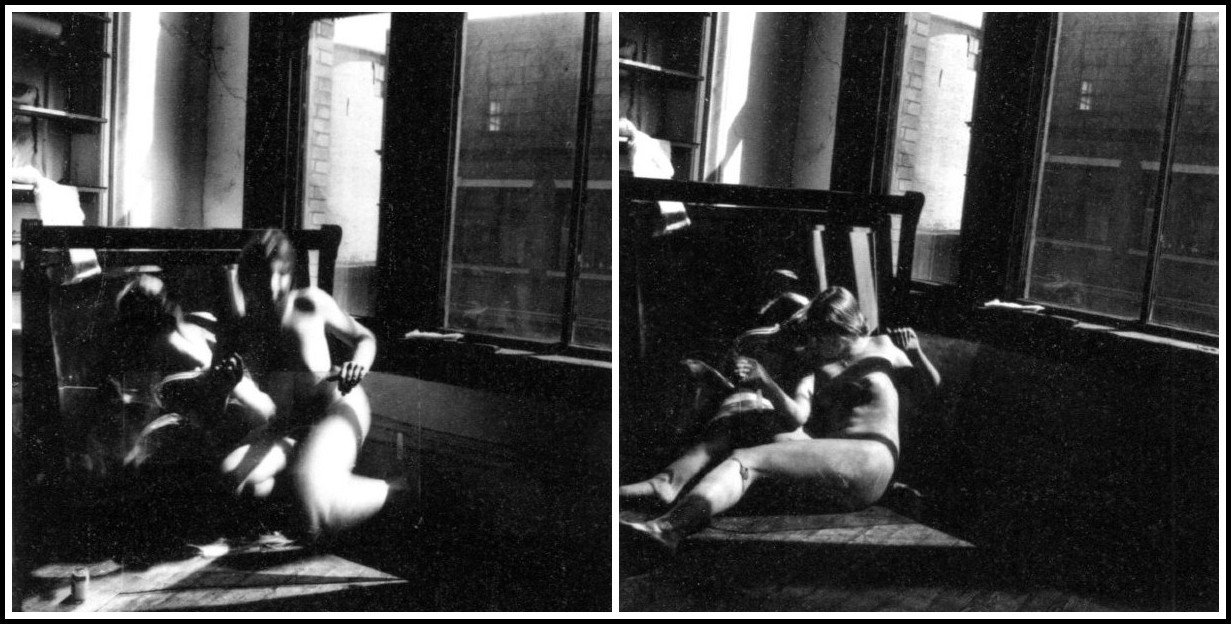

Each of these pictures troubles an economy of the gaze that puts the female body on display so as to offer visual pleasure to a male observer. The photographs move beyond a splitting of the portrayed female self into a male surveyor and a female object of the gaze by not only simultaneously staging the reflection in the mirror and the body there reflected, but by also adding a third element to the reflected image: the imprint behind the glass and the play of shadows on the skin of the artist. Both the figure in front of the mirror and her rendition in the mirror are blurred, distorted, fragmented: a fleeting appearance that refuses to remain fixed. The seriality of this set of photographs, moreover, suggests that to capture the female appearance in an image means splitting it into different embodied images. What emerges in the photograph is not a unified image of female charm but rather the destructive aspect of any desire to arrest a woman’s appearance in a pleasurable sight. Woodman appears only as a fragmented body, troubling the viewer’s wish to assure himself of his own wholeness and plenitude by virtue of this sight. At the same time, this visual self-dismemberment also serves a ludic intervention in precisely the image repertoire of classic nude painting with which, and against which, Francesca Woodman fashions herself. Although the woman in these photographs has appropriated the male gaze, she uses it to explore a plethora of possibilities by which, with the help of perpetual movement and transformation, she might elude being subsumed into one single, static image.

Francesca Woodman, A woman. A mirror. A woman is a mirror for a man – III & IV, 1975-78

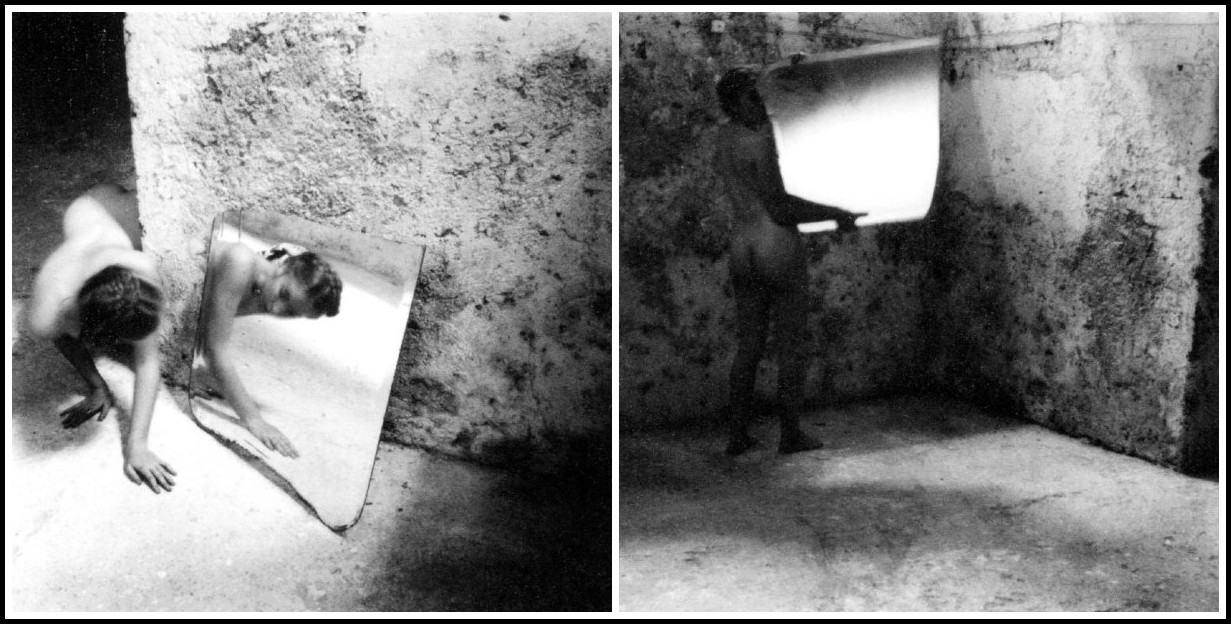

This self-conscious, ludic engagement with aesthetic processes that reduce her to a visual object is not the only strategy Woodman makes use of in her incessant engendering of her own self-image. The series Self-deceit has recourse to the traditional feminine vanitas motif, doing so, however, in order to perform ways by which the self might literally fade into an image. These photographs do not show a woman gazing into the mirror, so that the sight of her as yet untarnished body might allow her to pretend to herself that she can keep death at bay. Only in one photograph does the large mirror reflect the figure of Woodman as she crawls on the floor. In the other pictures, she uses this mirror to conceal her face, sits on it, or, due to the long exposure time, appears next to it like a phantom.

Francesca Woodman, Self-Deceit 1 & 2, 1978

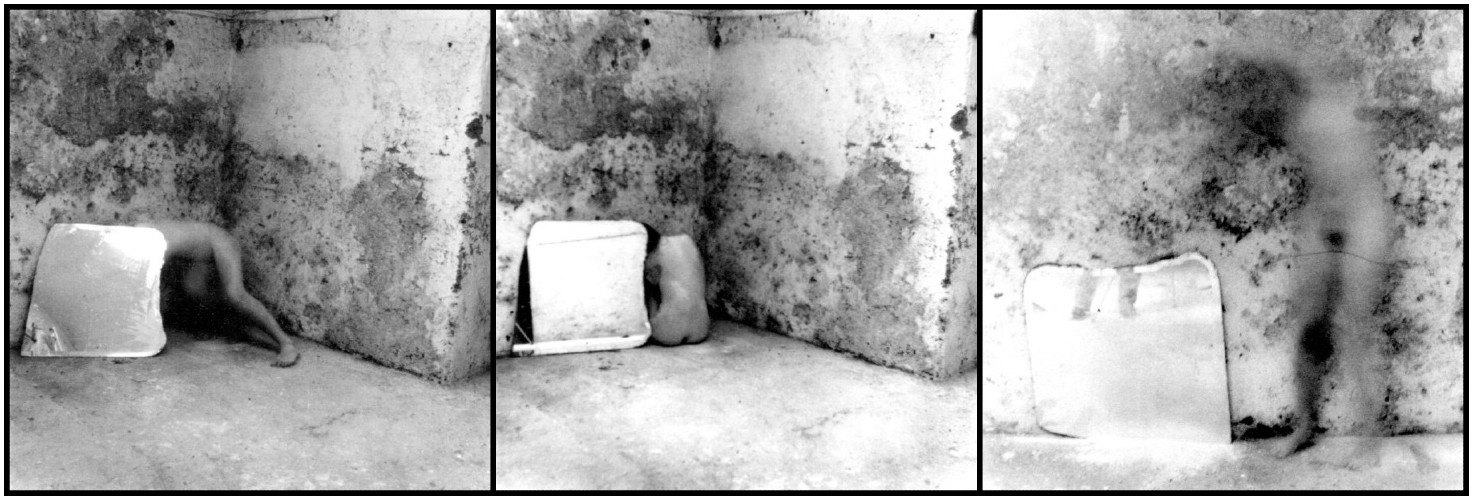

In each instance, a visual correspondence is played through between the naked body and the empty mirror image, even as these photographs self-consciously deny the viewer the sight of a feminine beauty intact. We are called upon to ask: at whose self-deception are these poses aimed? What is thwarted is not just woman’s vanity, because, by not looking into the mirror, she is denied the enjoyment of her self-image.

Francesca Woodman, Self-Deceit 3 & 4, 1978

The conspicuous absence of this reflected likeness, however, also anticipates the transience which the vanitas motif comes to articulate, by virtue of splicing together feminine beauty with bodily decomposition. Yet we also begin to suspect that the self-deception is being staged for us. The empty mirror beside or behind which Woodman hides is turned to face us. More is withheld from us than merely the image of female beauty onto which we might project our wish for plenitude. The reflection itself veers toward an empty space. It reflects absence.

Francesca Woodman, Self-Deceit 5, 6 & 7, 1978

Francesca Woodman’s play with the fading of her own self-image appears most uncanny in those works in which she literally stages herself as a lifeless object on display. In one photograph, she reclines on a shelf in a wall closet, packaged grocery products behind her bent knee. Her head has disappeared behind the wall. Her right foot sticks out from the shelf but is obscured by the tabletop edge around the sink in front of the window. Only her exposed pudendum offers itself up directly to our gaze. This sexualized body part finds a visual correspondence in the flower pattern on the paper lining the shelves as well as the numerous little bouquets neatly arranged on the wall shelf next to the closet. The fragmented body presents itself as a consumer object while also rendering an ordinary scene uncanny. The wallpaper peeling off the wall and the carelessness with which the lining paper has been laid out on the shelves evoke a sense of neglect.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, 1975-78

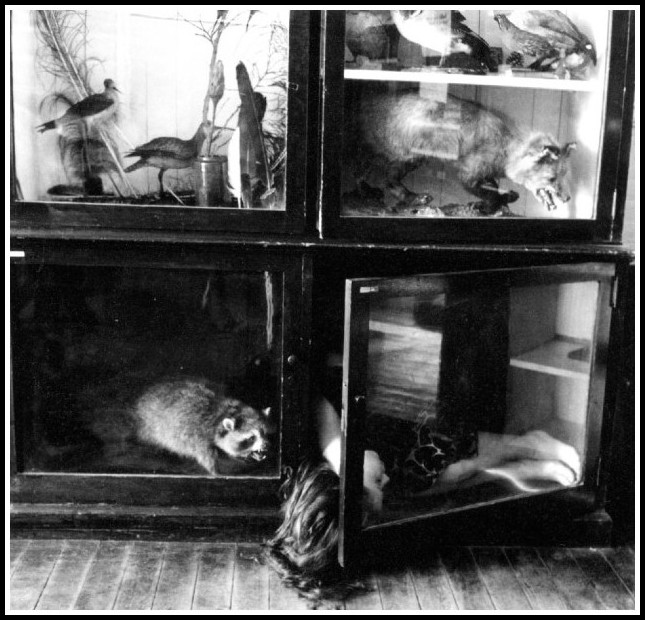

In another photograph, the symbolic equation between lifeless objects and the artist staging herself is even more sinister. This photograph shows her head, but she lies in a glass case next to mounted animals baring their sharp teeth at her, as though she herself were both a hunting trophy and a prey still in danger. Moreover, the open door cuts her figure into two halves so that we see the face and body only through the glass pane. Her hair flows from the display case and thus gains a peculiar tangible quality. The body may be immobilized, frozen into an object on display, but the visual fragmentation once again renders it intangible. It fades into the reflection of the room in the glass pane through which alone it comes into view.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, 1975-76

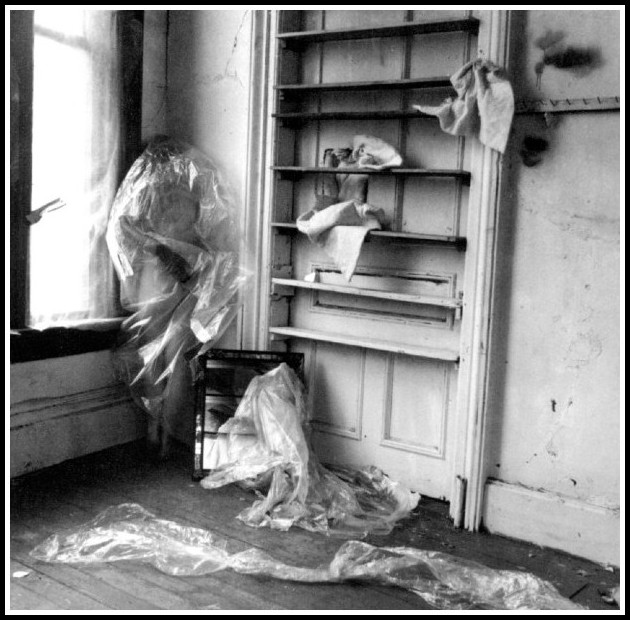

In a third photograph bearing the ominous title My House a seemingly lifeless Woodman stands in a corner next to a shelf. A plastic sheet covers her like a discarded mannequin, thoughtlessly left behind like the shreds of fabric on the shelf and the mirror at her feet. Her figure is barely discernible through the folds of the cover draped over her. Only one detail strikes the eye—the dark glove she wears on her left hand. This picture is Woodman’s most radical response to the visual tradition that defines the female body as a consumer object available for the viewer’s visual pleasure. If, in her self-portraits she plays with attributes that serve to characterize the pose she has struck, and if, in her nude photographs, she frequently plays a game of hide-and-seek with her own body, in this photograph the artist’s body emerges as a pure thing in our field of vision. The self-chosen transformation into an image-object offered up to the viewer for his voyeuristic pleasure plays with the multiple meaning of the word exposure. As a figure exposed by the light of photography, Francesca Woodman exposes herself, bares herself before a strange, external gaze, turns herself into an exhibited object. And yet the photograph records no more than the imprint that has been left behind. The immobilized woman appears only through the plastic cover. The artist resolutely eludes the photograph she has fashioned by and of herself.

Francesca Woodman, My House, 1976

ELISABETH BRONFEN ON OTHER FRANCESCA WOODMAN IMAGES

Beyond the photographs discussed in the preceding excerpt, you will find a very stimulating discussion of other Francesca Woodman images in the rest of Elisabeth Bronfen’s ‘Leaving an Imprint: Francesca Woodman’s Photographic Tableaux Vivants’, including the images presented below. Here, a short extract from the essay follows each image.

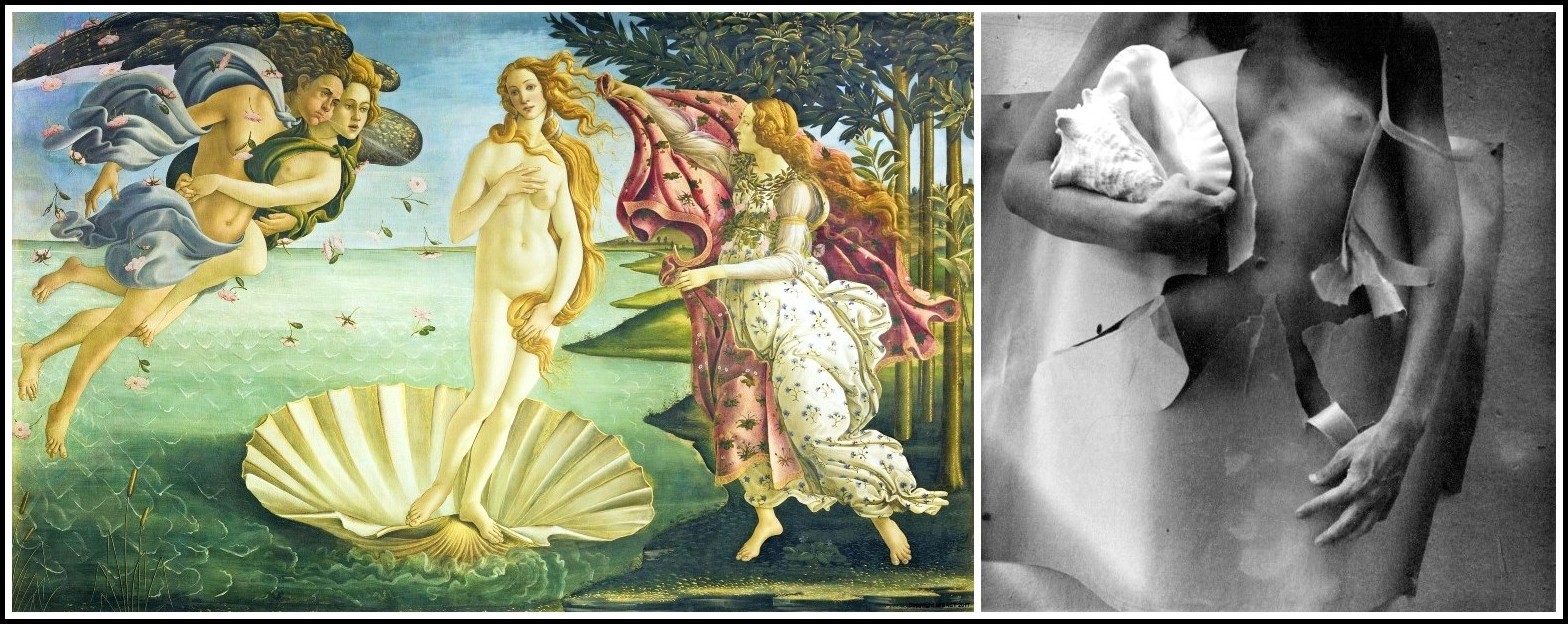

Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, 1485 | Francesca Woodman, Untitled, 1975-78

‘In a brilliant adaptation the artist uses her own body to rewrite the traditional image formula of the Birth of Venus. In her photo, a decapitated young woman rises not from the ocean’s waves but from a piece of paper pinned to the wall with thumbtacks. The seashell she cradles in her right arm symbolizes the female sex and its life-giving power while also attesting to the self-creation taking place. This too is a movement arrested.’

FRANCESCA WOODMAN

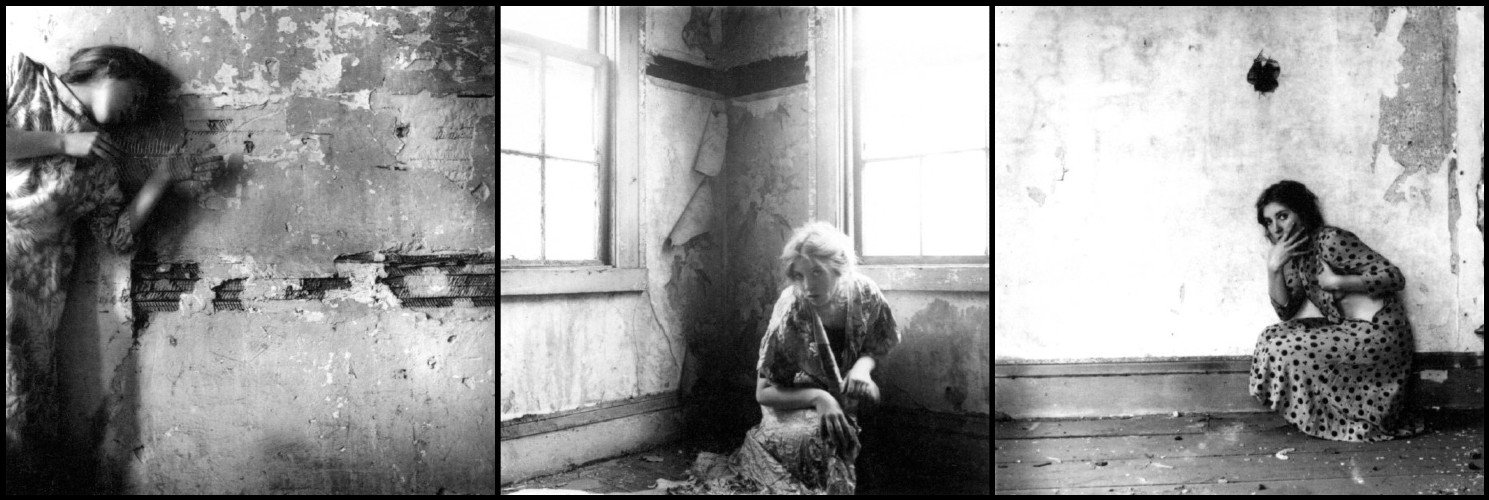

Untitled, 1976 | Untitled, 1975-78 | Polka Dots, 1976

‘The staged drama of these poses recalls the passionate attitudes photographed by Lady Hawarden. Francesca Woodman was convinced that she had been born in the wrong period and would have been more at home in the Victorian age.’

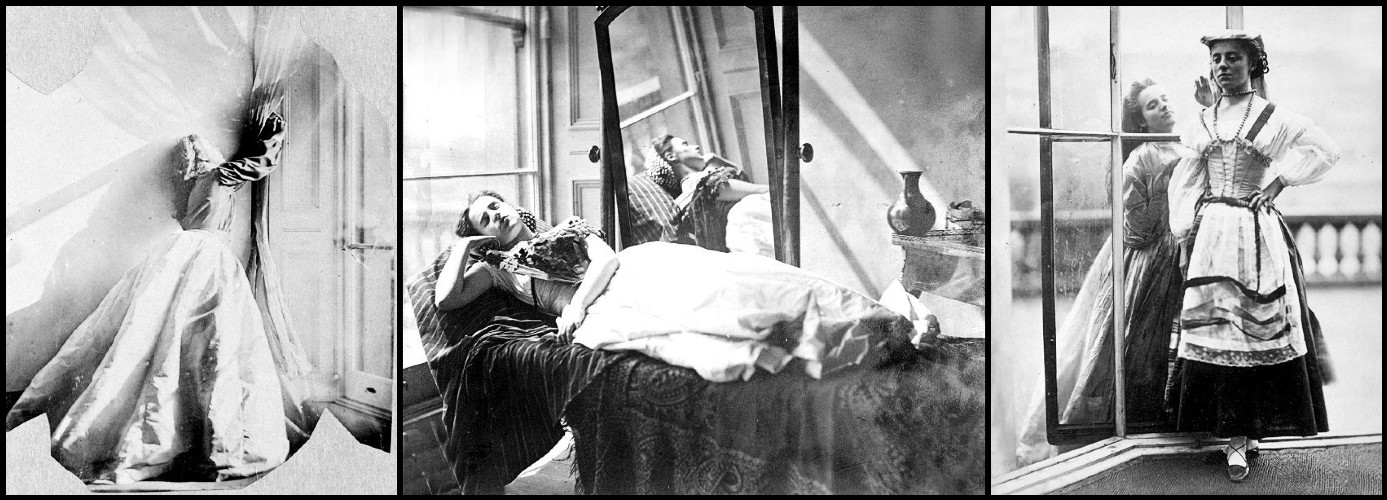

LADY CLEMENTINA HAWARDEN | © Victoria & Albert Museum

Clementina Maude, 1862 | Clementina Maude at 5 Princes Gardens, 1863 | Clementina Maude & Isabella Grace, 1864

‘For her compositions, this Victorian master of the tableau vivant frequently chose young women absorbed in their own thoughts.’

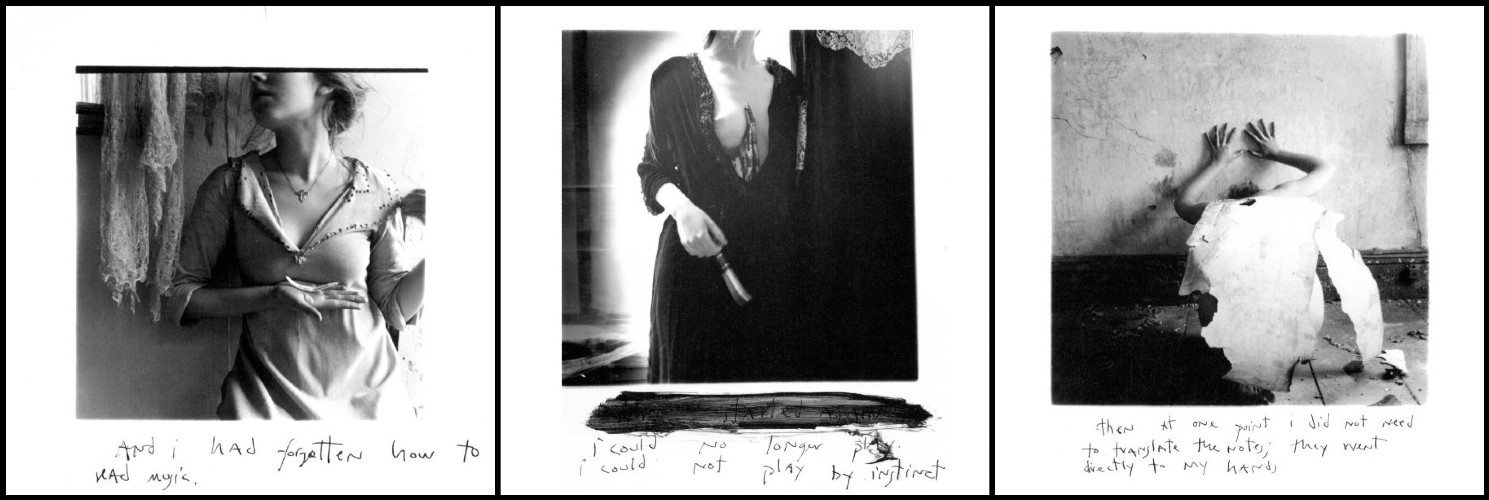

FRANCESCA WOODMAN, 1977

And I had forgotten how to read music | I could no longer play, I could not play by instinct | Then at one point I did not need to translate the notes; they went directly to my hands

‘In And I had forgotten how to read music, Woodman holds a strip of paper with writing on it in her outstretched palm; her face turned away from it. The exaggerated gesture stands in for the music that has been interrupted. In I could no longer play, I could not play by instinct, the knife Woodman holds in her right hand suggests melodramatic pathos while the upper edge of the picture cuts off her face. The bare right breast is also framed by a strip of photographic paper on which we can discern contact prints of several self-portraits. These stand in for the cropped face. At the same time the title draws us into an ominous mood. The streaks running down the pictures of the contact print suggest bloodstains. The inability to play invoked by the title allows us to anticipate the violent termination of theatrical playing as such. The photograph captioned Then at one point I did not need to translate the notes; they went directly to my hands shows Francesca Woodman cowering in front of a wall. Her back and posterior are almost entirely covered by shreds of wallpaper; imprints on the wall above her fingers vaguely suggest the keyboard of a piano. In this melodramatic pose, the negation contained in the subtitle obliterates all mediation. The expression of pathos no longer requires any notes. Instead, it flows directly into the hands which all three photographs employ as instruments of the conversion of the self into writing.’

ELISABETH BRONFEN: THREE BOOKS

Click or tap on the image to go to a description of the book

OBSESSED

The Cultural Critic’s Life in the Kitchen

CROSSMAPPINGS

On Visual Culture

SERIAL SHAKESPEARE

Appropriations in American TV Drama