RICHARD WAGNER’S WOMEN

TANNHÄUSER: ‘THE GLITTER OF A HIGH-CLASS BROTHEL’

EVA RIEGER

Translated by Chris Walton

Posted by kind permission of Eva Rieger, Professor Emeritus in Historical Musicology at the University of Bremen, and Chris Walton, Lecturer in Music History at the Hochschule für Musik Basel and Freelance Writer, Translator, and Editor.

From Eva Rieger, Richard Wagner’s Women, tr. Chris Walton (Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press, 2011) pp. 42-55

Richard Wagner

‘The women cast their frigidity into the ears of all men with their top Cs, while the men dream themselves out of everyday marital boredom into a seven-year holiday of boundless pleasure at the Venusberg—even if a hangover is lurking just round the corner. How sultry it all is, what a potage of overcooked, pulverized lust!’ Carl von Ossietzky’s sharp criticism of Tannhäuser was matched by Thomas Mann on hearing the Venusberg music on the radio: ‘A thoroughly sexual product at the close, with moist glances oozing through the hypocritical yearnings of the Pilgrim’s Chorus. Romanticism is an unclean world. I don’t want to hear of it any more’. And Ernst Bloch wrote of the work’s ‘glitter of a high-class brothel, with a rose of hell’. Tannhäuser prompted critics to salacious comments right from the very start, and during his lifetime Wagner himself experienced extreme reactions to the work. At one rehearsal, even his patron Otto Wesendonck found fault with its ‘lascivious tones’, and Wagner joked that Otto was probably scared he might have dangled them in front of his wife Mathilde. But there were also contrary voices, who criticized Tannhäuser’s love of Elisabeth as unworldly. Wagner found this ludicrous: ‘How absurd these critics must seem to me, who in their modern wantonness have become so ingenious. They want to interpret my Tannhäuser as specifically Christian and impute to him a tendency to impotent glorification!’ Wagner had to defend himself on all sides, whether against accusations of sexual excess or chastity.

‘The glitter of a high-class brothel, with a rose of hell’

Upon first approaching the work, one might assume that it was written in the traditions of the Enlightenment and Romanticism. As Hans Mayer has remarked, the contrast between bourgeois virginal dignity and the libertine tendencies of female nobility was a characteristic feature of the bourgeois Enlightenment. We see it over and over again in the novels and plays of Gellert, Richardson, Lessing and others. At first glance, it seems as if Elisabeth is the typically strait-laced, pious, domestic woman, who remains subject to her man throughout her life. Venus on the other hand is, in this interpretation, the evil femme fatale, feared by men because she enchants them only to enslave them. But it is all rather more complex than this. Wagner was probably inspired in part by the discussions of sexuality that were popular at the time of the Young Germany movement, and that will have led him to ponder the hypocrisy prevalent in all matters erotic.

Giovanni Boldini, Lady Colin Campbell, 1897 | Meredith Frampton, Winifred Radford, 1921 | Peter Lely, Jane Bickerton, Duchess of Norfolk, 1677

Before composing Tannhäuser, Wagner had conceived the plot of an opera entitled Die Sarazenin (‘The Saracen woman’). He was inspired by a drawing that depicted Friedrich II, ‘surrounded by his court, almost all of them Arabs, in which singing and dancing oriental women transfixed my imagination in lively fashion’. This scene later came to his mind when he created his Flower Maidens in Parsifal. The plot of Die Sarazenin hinges on Manfred, the son of Friedrich II von Hohenstaufen, who conquered Apulia and Sicily and was then crowned Holy Roman Emperor. Alongside these historical facts, Wagner concocted a young Saracen woman as a leading role ‘of the highest Romantic significance’. She appears at the court as a prophetess, urges Manfred on to victory under her protection, and finally has him ascend the throne. When an attempt is made on his life, she ‘takes the deadly blow in her own breast and in dying confesses her identity as that of Manfred’s sister. She thus lets him know the fullness of her love for him’, he wrote in his Communication to my Friends. The fate of this ‘Saracen woman’ resembles that of Senta and Elisabeth, though in her character she is closest to Brünnhilde. At the same time, she refers back to Irene, Rienzi’s sister. These thematic layerings show us how intensely Wagner was concerned with the topic of the redeeming woman and how he sought her artistic realization in ever new ways.

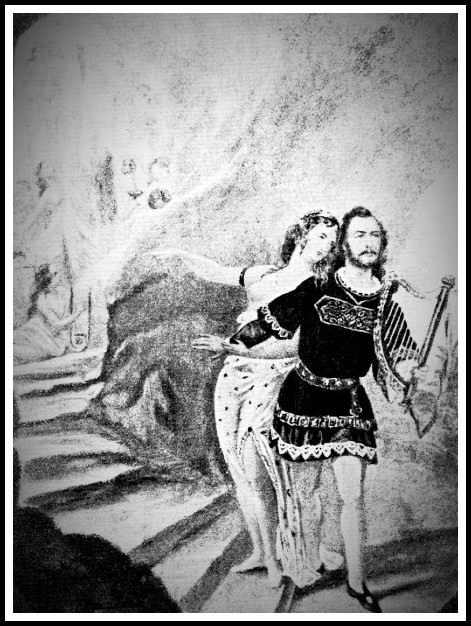

Richard Wagner: ‘Dancing oriental women transfixed my imagination in lively fashion.’

But he soon found that this plot did not offer him sufficient scope, so he replaced the idea of Manfred with that of Tannhäuser. Tannhäuser was, for Wagner, ‘the man of today, the man at the very heart of the artist hungry for life’, as he described him further in his Communication. He had discussed the characterization of the Saracen woman with the leading dramatic singer Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, who had already sung his Senta to his fullest satisfaction. He was not only impressed by her artistic accomplishments, for they both felt touched by the political matters of the day and saw their art as something that extended above and beyond mere matters of the stage. ‘She felt urged to feel things as a whole, to merge everything into one greater entity, and this wholeness in life and art was our very life in society itself and our theatrical art’, he wrote admiringly. The role of the Saracen woman, however, was not one that Wilhelmine could accept as Wagner conceived it.

Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, Tannhäuser, Venus

He had determined that the prophetess ‘could not become a woman again’—in other words, she could not be a prophetess and a feminine woman at one and the same time. Wilhelmine disagreed with him, as she was perfectly well able to imagine such a combination. It was not just this argument, but above all the unsettled life she led that destroyed the image Wagner had constructed of Wilhelmine as an ideal, devoted woman. We know from her authorized biography that she never succeeded in finding a partner worthy to match her, and that she–like Wagner–tried to dampen her yearnings by indulging in superficial pleasure. Her biographer, Claire Glümer, writes as follows of her loneliness: ‘In order to escape her unhappiness at being alone, Wilhelmine sought feverishly for a man to whom she could give her passionate heart. But it was not her talent to be lucky in love. With some men she would soon become convinced that they were insufficiently devoted to her; with others she would have to recognize that she had misjudged their qualities. Then she would turn away in pain and anger.’

Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, Tannhäuser, Venus

Richard’s contact with Wilhelmine put him ‘out of kilter, in a highly disconcerting manner’. He saw how she plunged into one inept relationship after another and was himself torn between his emotional desires and his need for superficial physical enjoyment. He was unsuccessful in finding any equilibrium between the domestic care provided by Minna and the passionate desire in which he indulged from time to time without ever being properly satisfied. It was at this time of inner turmoil that he wrote Tannhäuser. He said that he was in a mood in which ‘the figure of Tannhäuser returned to admonish me and urged me on to finish my libretto. I was in a state of gnawing, sensuous agitation that excited continually both blood and nerves when I sketched out the music for Tannhäuser and brought it to completion. My true nature, which had returned to me in my disgust at the modern world and in my urge to find something more and more noble, subsumed the most extreme aspects of my being in a powerful, passionate embrace, merging to find a climax in a single sweep that was the most intense desire for love’.

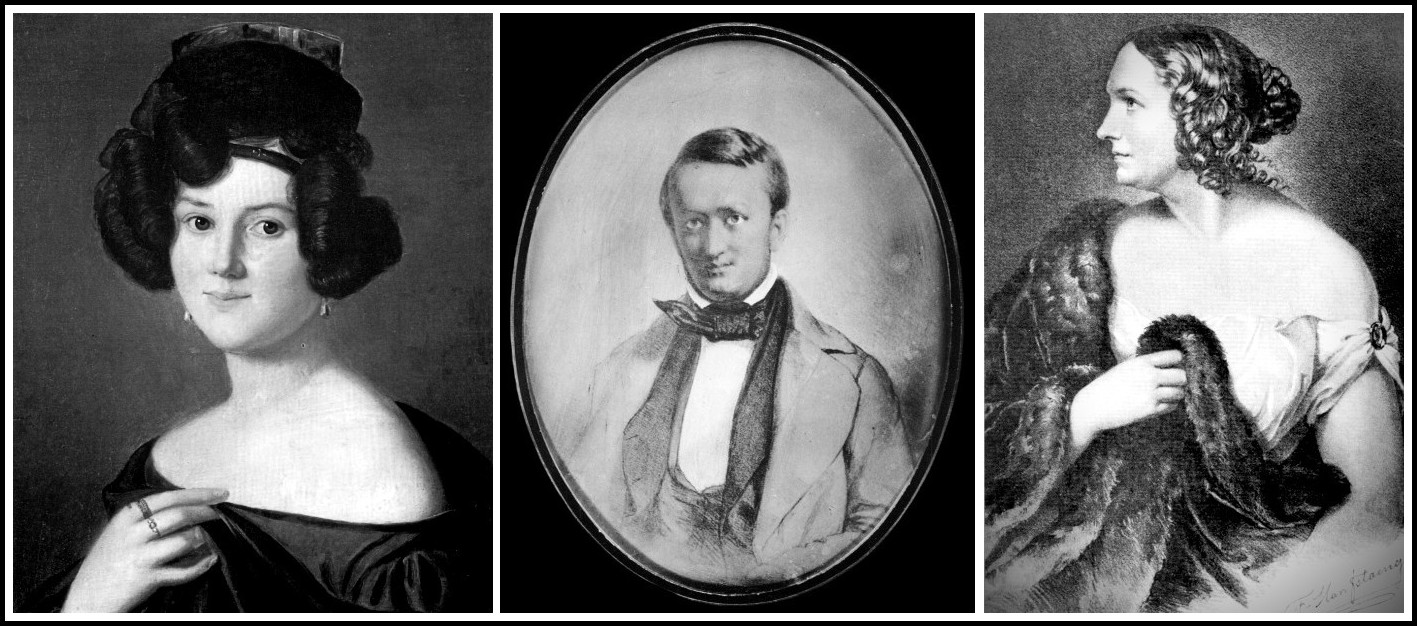

Christine Wilhelmine ‘Minna‘ Planer | Ernst Benedikt Kietz, Richard Wagner, Paris 1850 | Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient

This desire for love, which he was unable to fulfil in the ideal manner that he imagined, led him to give in time and again to ‘the urge for more or less swift enjoyment’. Later, he recalled this time thus: ‘Until then my being had maintained itself by an equilibrium of two warring elements of desire within me, one of which I sought to pacify through my art, whereas I would from time to time still the other by erotic, fantastic, sensual indulgences’. His ‘being’ was thus diverted from its ‘true nature’, he said. These confessions make it sound as if he was visiting prostitutes in Dresden. The 19th century saw an increase in population in the big cities that resulted in a corresponding increase in the number of prostitutes. It was particularly common for women with a low income, such as serving girls, shop assistants, flower girls and washerwomen to dabble in occasional prostitution. The sale of female flesh was especially common in the theatrical world, where voluntary prostitution on the part of the female staff—actresses, singers and dancers—was even taken into account by theatre directors when calculating their salaries. Wagner thus had plenty of opportunity to gather experience elsewhere, not least because he had irregular working hours and Minna could not keep a check on him. Several years later, when Richard wanted to flee to Greece with Jessie Laussot, Minna wrote angrily that ‘He gets itchy feet every few years, but this time is the worst’. So she was used to bearing a good deal from him.

Henri Gervex, Rolla, 1878 | Richard Wagner | Sassoferrato, Madonna in Prayer, 1645

Without any help from Minna, Wagner’s ‘urge’ disgusted him after a certain time, as we may infer from his Communication to my Friends. His yearning for a pure, ideal love finds expression in Tannhäuser: ‘In Tannhäuser I yearned to set myself free from the frivolous sensuousness that itself repelled me—it was the only expression of sensuousness that our modern times know. My urge was towards what was unknown to me and what was pure, chaste, virginal, all of which I hoped might provide fulfilment for a more noble, yet at the same time still essentially sensual desire—but a desire such as the frivolity of the present day could not satisfy.’ This desire to turn away from superficial eroticism is combined with his criticism of the entertainment that was offered to audiences in the theatres and concert halls of the big towns. Speculators, capital and the striving for profit dominated the cities, he said; plays of lesser quality were performed in order to provide a good income. Wagner criticized the stance of many a theater director, who ‘today offers vulgar jokes, tomorrow a piece for Philistines and on the third day a spicy delicacy for gourmets’. This condemnation of commercialized art led in the long run to the creation of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de’ Benci, 1476 | Manet, Nana, 1877 | Leonardo da Vinci, Virtutem Forma Decorat – Beauty Adorns Virtue, 1476

However much Wagner kept his eye open for possibilities of ‘erotic adventure’, he remained in many respects dependent on his wife Minna. He needed his ‘very best Minel’ as a crutch in everyday life and as the protector of his creative work. In May 1843, when he was working on Tannhäuser, she went on a trip and Richard was overcome by a great feeling of restlessness. He wrote to her: ‘I have to avoid distractions as much as possible and go walking a lot on my own. It has to continue like this if I am to bear your absence’. He obviously tried to lessen her suspicions (no doubt well founded) that he was being unfaithful by assuring her that he stayed at home in the evenings. Furthermore, he wrote, people had told him he was getting fat. ‘You see, that comes from my serious attitude to life, the avoidance of pleasure, going to bed at 10, sometimes even at 9:30 – and anyway, you know that capons get fat.’ It is undeniable that he nevertheless gave in to his erotic fantasies time and again, though they always led him into that ‘terrible empty desert’, as he called it, resulting in the end in an irreconcilable conflict. It was in the fictitious world of his operas that Wagner worked through this conflict. As so often with him, life and art are intertwined.

RENE MAGRITTE

La magie noire, 1935 | Philosophie dans le boudoir, 1966 | Les jours gigantesques, 1928

It is thus unlikely that Tannhäuser was inspired only by Wagner’s musings on the role of the artist or the work of art of the future, as is often claimed. It is also—indeed, primarily—about woman. Even if many commentators have difficulty in accepting the powerful influence that women have on the lives of artists and thus on their artistic production, it remains a fact: Wagner’s longing for ‘the trusted shade of a loving human embrace’ occupied him throughout his life and is thus also of central importance in his works. From this summit my yearning glance saw—woman; the woman for whom the flying Dutchman yearned from the sea-depths of his misery, the woman who became the star of heaven that showed Tannhäuser the way to salvation from out of the lustful pleasure caves of the Venusberg, and the same woman who drew Lohengrin from his sunlit heights down to the comforting, warming breast of earth.

Sandro Botticelli, Young Woman (Simonetta Vespucci) in Mythological Guise, 1485 | Ridolfo Ghirlandaio, Lucrezia Sommaria, 1510 | Girolamo di Benvenuto, Portrait of a Young Woman, 1508

In the ‘Legend of the Knight Tannhäuser’ in the collection of legends that Ludwig Bechstein published in 1837, on which Wagner drew, the erotic is largely sidelined. Besides sources by E. T. A. Hoffmann, Ludwig Tieck and others, Wagner was also influenced by Heinrich Heine’s great poem Der Tannhäuser, though as in the case of Der fliegende Hollander he excised everything that was ironic or banal. Heine could do nothing with the topics of sin and redemption—addressing these themes, his verses descend into the trivially comic. He says of Venus, for example, ‘She gave him soup, she gave him bread, she washed his wounded feet, she combed his straggly hair, and all the while laughed so sweet’. Such episodes were of no use to Wagner. In the first edition of his Tannhäuser libretto, he describes Venus and underlines in particular the fascination that she exuded in the Germanic legend in which she figured. She united ‘all notions of a being magical but unhappy, and who entices one to indulge in sinful, sensual pleasure’. He did not want to make Venus too negative, for Tannhäuser was obviously very much at home with her. All the same, the sinfulness of what she does had to be made clear. In any case, there was no room for irony.

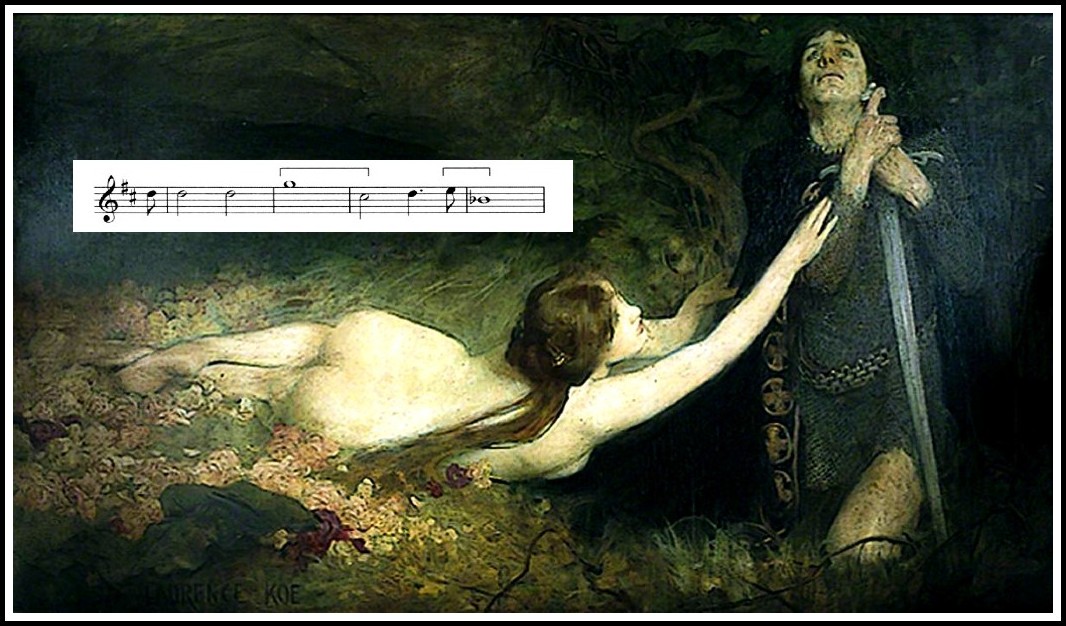

Henri Fantin-Latour, Tannhäuser on the Venusberg, 1864

When he was in Paris in 1860-61, several years after finishing the opera, Wagner refined the music of the Venusberg. His experience of life in the meantime had expanded his vision, as he wrote to Mathilde Wesendonck: ‘I have worked somewhat on the music for my new scene. It is strange: everything interior, passionate, I could almost say: feminine and ecstatic, I was unable to realize at the time I wrote Tannhäuser. I have had to cast everything overboard and sketch it anew. Truly, I am horrified by my cardboard-cut-out Venus of back then!’ He presumably wanted Mathilde to know that only she was able to awaken the emotional and the sensual within him that in turn made possible a higher level of compositional maturity. In his correspondence with Otto Wesendonck, on the other hand, we read: ‘I have not yet been able to finish the orchestration of the new scene between Tannhäuser and Venus. The first—the dance scene—isn’t written at all, and I have as yet no idea how I want to do it’. Whereas Mathilde learns that he is only now experienced enough in life to be able to compose erotic music, he tells Otto tactfully that he is devoid of ideas for it.

Mathilde Wesendonck | Otto Wesendonck

The impact of eroticism on the world of man—at once enticing yet dangerous—is clearly audible in the music. The overture comprises the melody of the Pilgrims’ Chorus, Tannhäuser’s hymn to Venus and a description of Venus. At first, calm chords are heard in the wind, intoning the Pilgrims’ Chorus. The major mode, the triad at the beginning of the melody, the periodic construction and the chorale-like chords make for a dignified, ceremonial atmosphere. This becomes ever more highly charged until the trombones repeat the melody emphatically, accompanied by rapid ornaments in the violins. This is a ‘man’s world’ to a tee, into which, however, the world of the erotic suddenly enters: the slippery, descending chromaticism, the trills and the lack of a bass line deprive the music of its firm foundations, and this effect is strengthened by the diminished-seventh chords announced in the violas.

RICHARD WAGNER, OVERTURE TO TANNHÄUSER

HERBERT VON KARAJAN, BERLINER PHILHARMONIKER, 1975

In European music, the bass usually forms the backbone upon which everything else is built. Whereas the music of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, which grew out of Gregorian chant, is based on a cantus firmus—a melody played throughout that is embellished by instruments and/or voices—the tendency became ever clearer after 1600 to build up harmonies from a supporting bass line. The decisive novelty in musical Classicism (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven) was cadence-based composition, which enabled major/minor tonality to achieve its final breakthrough. Chords were now built upon a bass line that utilized dissonance to create tension that is then resolved by ending in the tonic. Any lack of bass support thus has a destabilizing impact. This is the case here, and its disconcerting effect is heightened in Wagner’s depiction of Venus, in which he employs unusual harmonic combinations. The aria with which Venus intends to seduce Tannhäuser contains two tritones that convey the danger she signifies.

Laurence Koe, Venus and Tannhäuser, 1896

Wagner gives stage directions for Venus’s realm whose boldness is surprising, for he here makes evident his knowledge of female anatomy. In a grotto that extends as far as the eye can see, there is a lake with a greenish waterfall, under which the waves billow. Tropical foliage grows everywhere, and everything is bathed in a gentle rosy light. On the stage lie young men entwined with nymphs. It is noteworthy that Minna did not like the musical expansion of the Bacchanale that Wagner undertook in Paris, calling it ‘Venus shenanigans’. Baudelaire, on the other hand, spoke appropriately of ‘ever new onslaughts of pleasure’. Wagner also added an obviously exotic element to the music. In the scene he sketched afterwards, he imposed no limits on his imagination. The depiction of the sexual act, which was at the time never spoken of in public and was at best a source of smut in the male boudoir, is here lavishly embellished. Triangle, castanets, timpani, cymbals and tambourine all evoke an exotic sound-world. Everything turns upon the satisfaction of sexual desire, and the sirens sing: ‘Approach the land where blessed warmth in the arms of glowing love will still your urges!’ These unfettered, sensuous, enticing sounds are furnished with extensive stage directions by Wagner. A procession of Bacchantes approaches, and their ‘gestures of enthusiastic inebriation’ urge the lovers to indulge in ‘wild pleasure’. They throw themselves into ‘erotic loving embraces’. Satyrs and fauns dance in between the couples, and the ‘chaos increases to a point of the greatest intensity’. In the midst of the ‘highest frenzy’, three graces emerge, who endeavour to dampen the excitement. They shake the sleeping Amorettes, who flutter up and from above shoot six arrows into the hurly-burly. In contrast to the pious pilgrims’ music at the beginning, here it is women who determine the course of events.

School of Mantegna, Venus, 1450 | Joseph Collyer after Joshua Reynolds, Venus, 1786 | Virgil Solis, Venus, 1545

In his first ideas for the scene, as Wagner described them to the Wesendoncks, which were later omitted from his stage directions, this utopian vision was mixed with scenes of fear. The wild tumult was to have seen appearances by tigers, panthers and imaginary creatures, including giant birds with human torsos, or animals that were half lion, half eagle. The graces were to have been ‘overpowered’ by the centaurs and carried off (in other words, raped). Here we see that Wagner’s conception of the scene was at first contradictory: he wanted the charms that Venus exuded, but also the terrible fear of the vagina dentata. When Baudelaire speaks in admiration of the ‘true, terrible’ Venus, ‘dominant everywhere’, he stresses that aspect of her being that tends to possession. Despite the unending pleasure that she is ready to give, she provokes fear at the same time because she threatens to ensnare men. But Wagner did not want to see Venus damned, and Tannhäuser was not to criticize her expressly. This ambivalence can also be observed in Wagner’s essay ‘On performing Tannhäuser’, in which we learn that the singer of the Venus in Weimar was so successful because she was unselfconscious and played her role with warmth.

Diego Velázquez, The Toilet of Venus, 1649 | Piero di Cosimo, The Fight between the Lapiths and the Centaurs, 1507

Wagner’s characterization of Venus makes her a precursor of those fantasies of ineffably enticing yet repellent women developed by artists, writers and musicians particularly towards the end of the 19th century. In 1890 Lovis Corinth painted a Bacchanale that conveys both lust and fear, in which a woman has pushed a man to the ground and places her foot on his body in a gesture of triumph. In 1885 Paul Cézanne had also painted a wild Bacchanale, while Alfred-Philippe Roll painted Festival of Silenus, in which the activity of the entwined naked couples is obvious to all. Arnold Böcklin, Maximilian Lenz, Franz von Stuck, William-Adolphe Bouguereau—the list of painters goes on and on.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Nymphs & Satyr, 1873 | Franz von Stuck, The Sin, 1893 | Alfred Philippe Roll, The Festival of Silenus, 1871

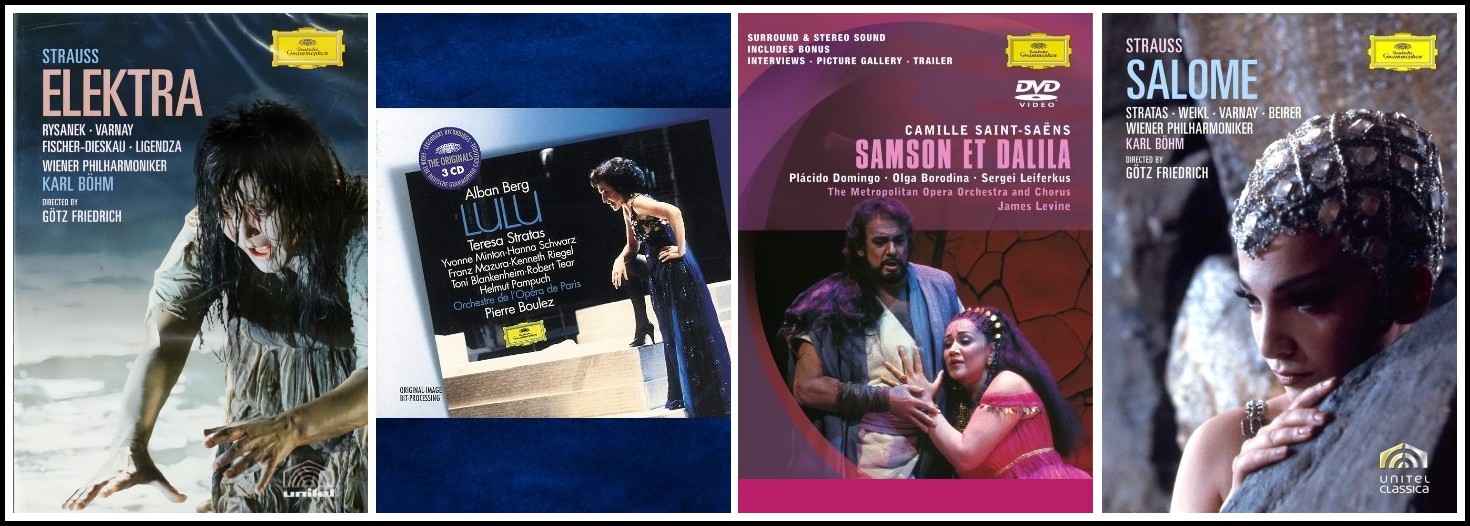

The erotically enticing woman who stands outside bourgeois norms was also a theme of numerous operas in the late 19th century and into the 20th. From Richard Strauss’s Elektra and Salome via Samson and Delilah by Camille Saint-Saëns down to Alban Berg’s Lulu, these characters reflect the fears conjured up at the time by the notion of a strong, independent, sexually potent woman.

Richard Strauss, Elektra | Alban Berg, Lulu | Saint-Saëns, Samson & Dalila | Richard Strauss, Salome

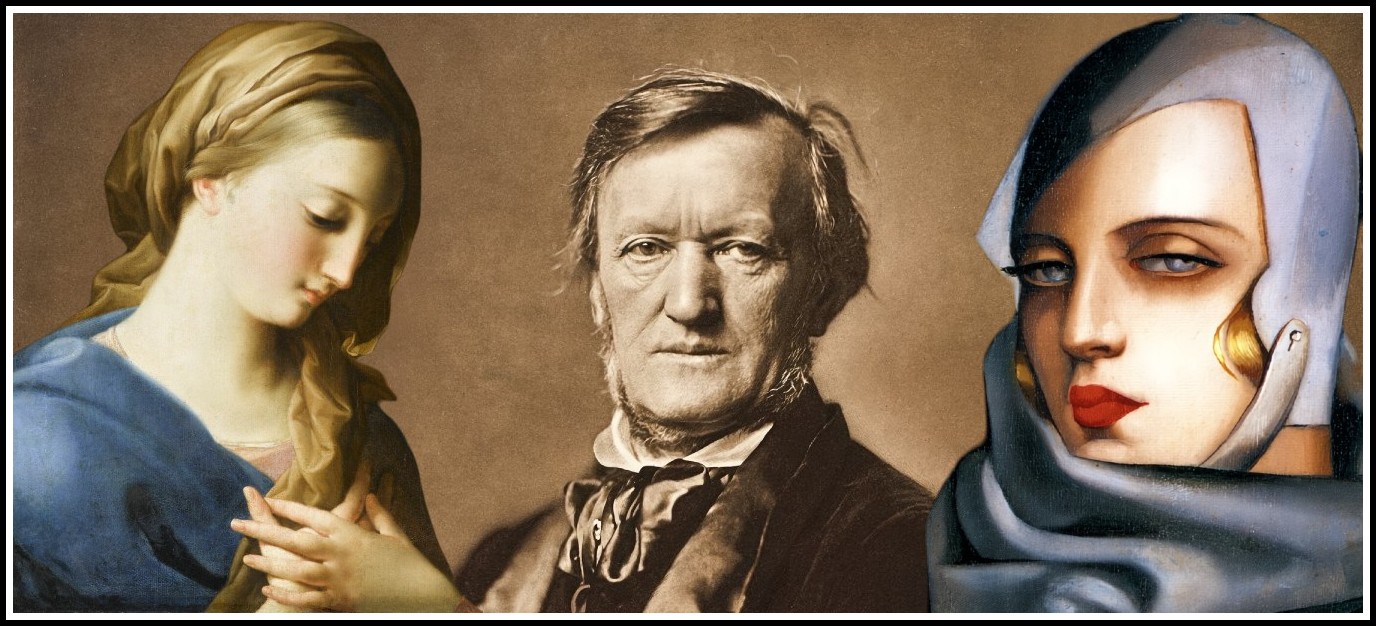

It is not simply sexuality itself that is condemned in Tannhäuser when Venus is rejected, but the act of being ‘swallowed up’ by one’s lover. To be captured is, in the end, unbearable, even if it promises endless erotic fulfillment. It is not that Tannhäuser has simply had his fill of the love of Venus, but rather that he feels himself a prisoner in her realm, for she possesses ‘excessive enchantment’ from which he wishes to flee. For a man it is impossible to bear being trapped in woman’s territory for a long period of time. He would prefer to measure himself against his own kind—at the hunt, making music, fighting. ‘My yearning is for the fight, I do not seek pleasure and lust’, cries Tannhäuser in despair, using a typically gender-specific cliché. His song is simple and in lied form. Venus’s part, on the other hand, has an extremely high tessitura. Her palette of sounds creates an impression of glimmering will o’ the wisps that ascend higher and higher. Venus tries to seduce Tannhäuser once more with the words ‘Come, beloved, see the grotto there’, and we hear the fascinating sound of eight-part divisi violins and a chromatically winding melody. But she does not succeed. Tannhäuser’s final refuge lies in religion, which he conjures up in the form of another woman: ‘I will not find peace and calm in you! My salvation lies in Mary!’ As Venus sinks away with a shriek, a further contrast between Christian faith and the sinful underworld is drawn: only a saint such as the Holy Virgin can help resist the influence of Venus.

Pompeo Batoni, The Virgin of the Annunciation, 1740 | Richard Wagner | Tamara de Lempicka, Self-Portrait, 1929 (detail)

Tannhäuser then finds himself in a lovely valley under blue skies. Cowbells tinkle in the distance. A shepherd plays a folk-like tune on the cor anglais, its lack of any accompaniment contrasting starkly with the sultry, passionate sounds of the Venusberg; then he sings a naïve song in praise of the love goddess, Frau Holda. Here in the upper world, the sensual magic of love is gone and the pastoral is dominant—the countryside was regarded in the 19th century as the bearer of all that was healthy and genuine. A procession of pilgrims passes by, singing. Clarinets, bassoons and horns are heard, and their deep sonority is intensified by the entry of violas and cellos, until finally the whole orchestra joins in, with the trombones predominant. Ceremonial chords underline the music’s religious, ecclesiastical context, and serve to ‘ennoble’ the sound of the chorus of pious men. The Landgrave now appears, with men in hunting outfits. There is an onstage hunting horn, plus a further nine off stage—a large complement for such a small scene. The sounds of the hunt are employed intentionally to underline the contrast between the two worlds. Tannhäuser has freed himself from the sultriness of the Venusberg and has arrived in the natural world, where a typically male activity awaits him—one that can guarantee joy in life. The happy freedom of nature thus has masculine connotations, whereas the suffocating underground caverns are female.

Gustave Courbet, The Quarry, 1856 | John Collier, Lilith, 1887 | Jed Owen, Cave, 2022

The second act opens in the Hall of Song in the Wartburg. Elisabeth enters, excited and joyful, singing the aria ‘I greet thee again, beloved hall’. Although Tannhäuser is the reason for these emotions, he is not named—she projects her happiness onto the four walls of the hall, and this in itself alerts us to how pure and innocent she is in matters of the heart. Yet her emotions overcome her: ‘But what a strange, new life your song has awakened in my breast! It seemed at first to be a pain that surged through me, then it pierced me like a sudden joy. Emotions that I have never felt! A longing that I never knew!’ As a loving woman who has erotic feelings, she is now no longer innocent, but ‘knowing’.

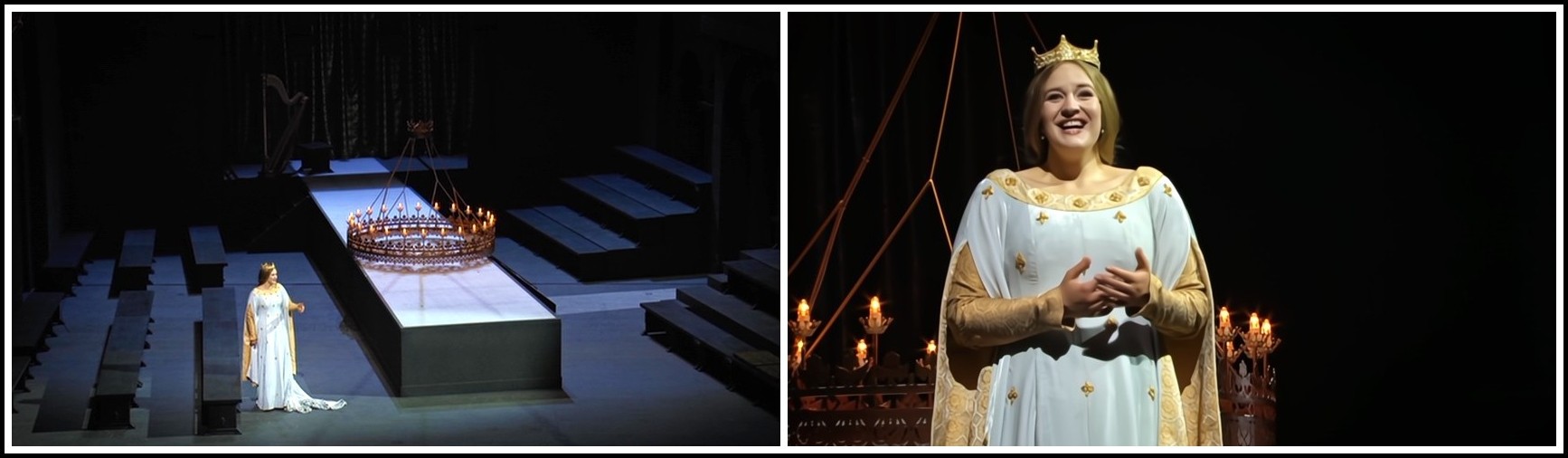

Lise Davidsen (Elisabeth), Tannhäuser, Bayreuth 2019

The Landgrave makes a stately entrance and talks with her. His part is mostly diatonic and conveys a sense of lordly authority. Three trumpets on the stage announce the imminent festival, and they are followed by the ceremonial entry of the guests in honour of the singing contest. The procession moves along to a brilliant diatonicism, with dotted rhythms and sonorous chords, the full sound of the strings complemented by the gentleness of the horns. ‘We joyfully greet this noble hall’ sings the chorus of knights, and this joy is communicated in the music. The noble women continue the song, which provides a certain equilibrium, given the dominance in the ensemble of the (male) singers, counts and knights.

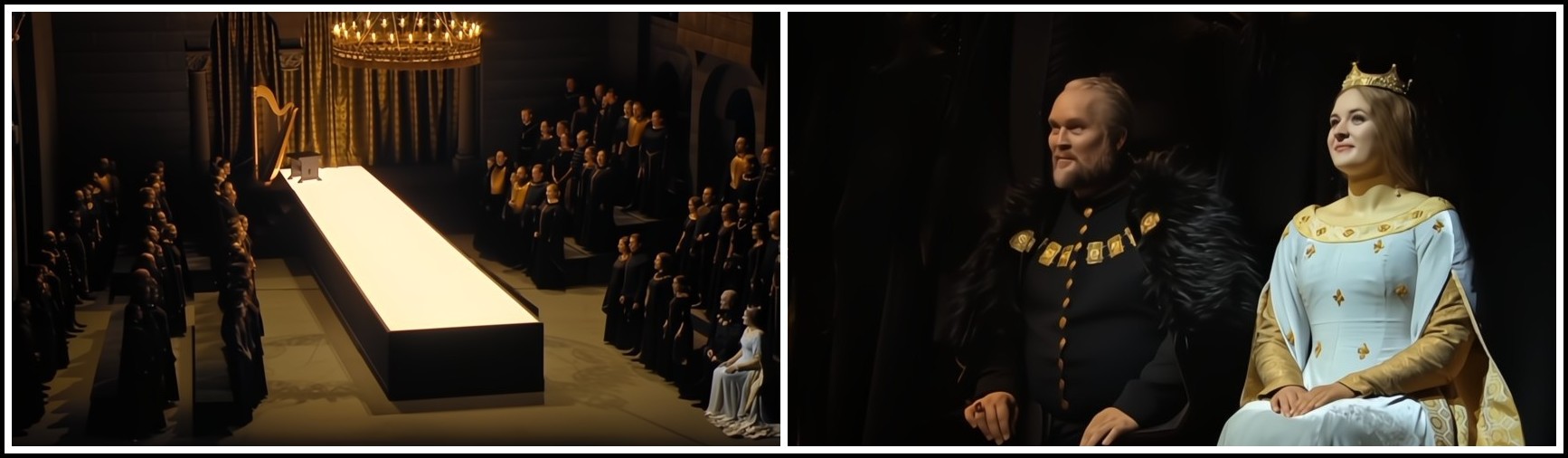

Stephen Milling & Lise Davidsen, Tannhäuser, Bayreuth Festival 2019

Elisabeth is characterized by a mixture of virginal innocence and experience. In E. T. A. Hoffmann’s novella Der Kampf der Sänger (‘The battle of the singers’), which influenced Wagner, the countess Mathilde is married; but Wagner needed a virgin. He required that the singer in the role of Elisabeth should in performance ‘give the impression of the most youthful, most virginal innocence, without any suspicion of how subtly those feminine emotions, born of much experience, could make her able to solve the task appointed her’. This combination of contradictory, almost mutually exclusive characteristics—virginal and yet mature—points us towards Wagner’s ideal picture of the loving woman, strong in love, and yet at the same time subordinate to her male partner. Time and again the oboe is heard in scenes with Elisabeth, as for example in her conversation with the Landgrave. When Wolfram describes her to Tannhäuser as the ‘most virtuous maid’, the oboe underlines her virtue. The composer thereby conveys a double message: Elisabeth has deep feelings, even sexual longings, but she retains her virtue.

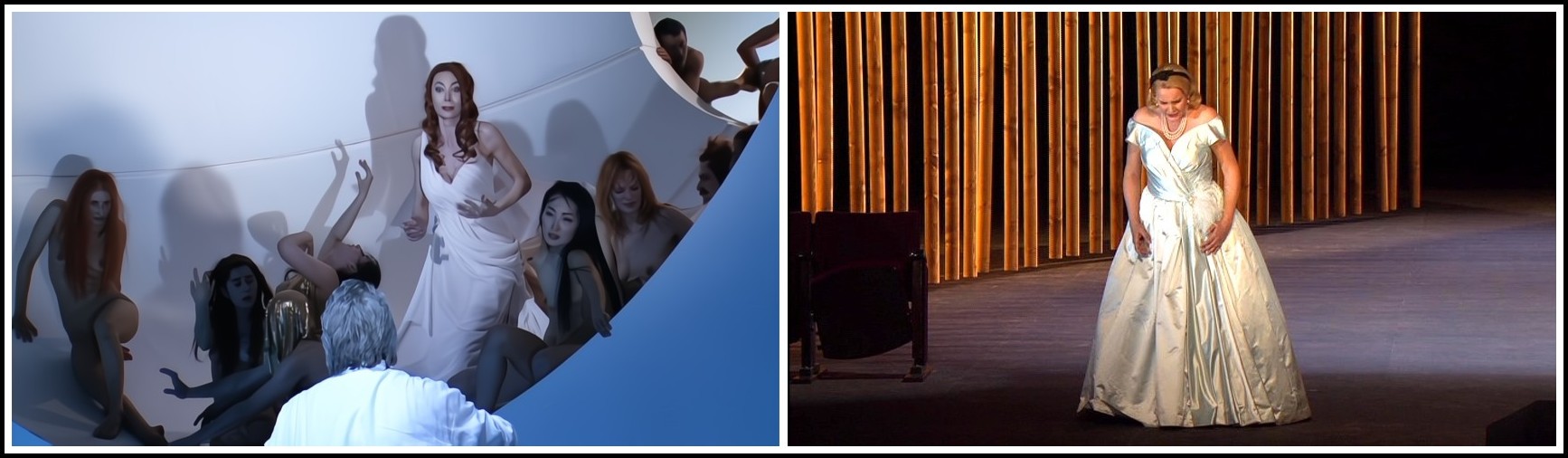

Lise Davidsen & Elena Zhidkova (Venus), Tannhäuser, Bayreuth Festival 2019

Towards the end of the opera, Elisabeth’s transformation into an ‘angel’ is praised, and she dies as an ideal Mary-type. In the final act—above all after her suicidal prayer—she is nothing more than a chimera, a figure without any life of her own. She serves merely to personify Tannhäuser’s ‘highest longing for love’. But it has been a long journey for Elisabeth to get this far—the passion she displays in her opening aria, ‘Dich, teure Halle’, stands in contradiction to her later angelic self.

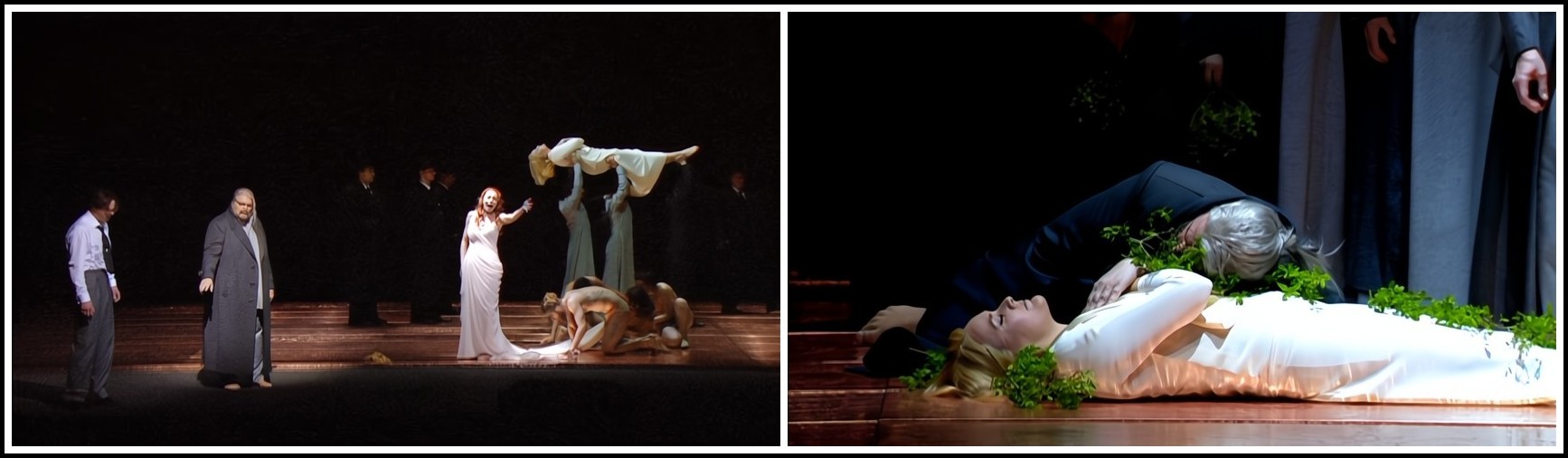

Stephen Gould, Lise Davidsen, Markus Eicher& Manni Laudenbach, Tannhäuser, Bayreuth Festival 2019

She understands Tannhäuser’s conflict, not just through feelings of solidarity, but because she too knows desire. Sensual passion was at that time a taboo topic for women. A woman in the 19th century was not allowed to experience lust, because this threatened to make her independent and would in turn endanger male dominance. The fact that Elisabeth admits to her desire is thus a breaking of taboos, even if that desire is watered down by being centred on one man alone.

Lise Davidsen, Markus Eicher& Manni Laudenbach, Tannhäuser, Bayreuth Festival 2019

Wagner thus accepts the sexual origins of Elisabeth’s passion and understands that it is a component part of her being—albeit only when channelled and fixed on a single lover. When Elisabeth learns that this man has given himself to unlicensed sexual pleasure, she is as shocked as are the knights, but her love is so strong that she overcomes her feelings of revulsion. She saves her lover from the threat of murder by the knights and hopes for a pardon from the church, so that she may yet be united with him. When the news of his rejection arrives from Rome, life has no more purpose for her and she begs the ‘almighty virgin’ Mary to hear her prayer. At this point, we see and hear Elisabeth’s pious side. Her earlier passion has receded into the background, and she is transformed into an ‘angelic’ being: ‘Let me enter into thy blessed realm, pure and angel-like / If ever, ensnared by foolish fancies, my heart did stray from thee / if ever a sinful longing or a worldly yearning sprang up within me / I wrestled it amidst a thousand torments to kill it in my heart!’.

Manet, Olympia, 1863 (detail) | Lise Davidsen, Tannhäuser, Bayreuth Festival 2019 | Andrea Celesti, Virgin at Prayer, 17th-century

Her prayer is influenced by the French/Italian preghiera tradition. Wagner had written a similar prayer in the third act of Rienzi (‘Allmächt’ger Vater, blick’ herab’ — ‘Almighty Father, look down’), though there the singer is a man. The content of the two prayers is indebted to the usual gender-specific models: whereas Rienzi begs to be saved and is anchored firmly in the here and now (‘Do not yet take away the power that your miracle gave me’), Elisabeth has given up all hope and yearns for death. Her prayer is accompanied in the orchestra only by woodwind, and its individual lines are organized largely symmetrically, conveying an impression of naivety. Despite occasional chromaticism in the melody, which accords the character a certain individuality, the tradition of simplicity and modesty prevails. The clarinet, bass clarinet and bassoon accompany her lament. The first four lines all lead downwards—a clear sign of sadness. Only in the middle section is there any movement—when she speaks of her guilt (though there is no hint of what this could possibly be). The melodic line is enriched and chromaticized by diminished-seventh chords, the words ‘thousand pains’ are stressed by a descending octave leap, the harmony loses its sense of stasis and the woodwind instruments flute and oboe (both of which carry feminine connotations) join in.

Lise Davidsen, Tannhäuser, Bayreuth 2019

But this confession of guilt sinks away in the recapitulation of the first section, so that the prayer ends as it began: at a slow, regular tempo, clearly periodic in construction and with transparent, tender orchestration. After Elisabeth has fallen silent, the woodwinds—instruments from the ‘feminine’ realm—play during her long exit (59 bars). Wolfram offers to accompany her, but she rejects his offer. According to the stage directions, she is to make clear to him by her gestures that ‘her path is leading her to heaven, where she has a high office to perform’. Three flutes ascend to a high, bright note that signifies her spiritual ascent. Oboes and clarinets join them, then the bassoon. The long-held, organ-like chords create a feeling of devoutness and solemnity. The slinking descent of the melody, the reduced accompaniment, the dark, strange sound of the bass clarinet, the simple rhythm, devoid of tension, the emphatic accentuation of pain and suffering by means of high notes—all these depict a woman who, here on earth, thinks of nothing but her lover and is ready to die for him. Here we find another example of how Wagner unfolds his musical material in conjunction with his dramatic and character-specific ideas.

Lise Davidsen & Stephen Gould, Tannhäuser, Bayreuth 2019 | Camille Claudel, Imploring Woman, 1900

Elisabeth’s contradictory aspects cannot be resolved by the juxtapositions in her musical characterization—namely, the fact that she is supposed to be a woman with sensual experience and yet at the same time a pure, angelic girl, who is by nature devoid of any such experience. We find a similar ambivalence in Wagner’s reaction to the Madonna by Carlo Dolci (1616-86), of which he saw a copy in the city church of Aussig, while working on the prose sketch of Tannhäuser. It had a decisive impact on his image of Elisabeth. The picture delighted him, and ‘if Tannhäuser had seen it, I could fully understand how it came about that he turned away from Venus to Mary, despite not being particularly enamoured of piety. In any case, now the holy Elisabeth stands clearly before me’. The Madonna, with her slightly bowed head and downward glance, comes across as modest, but not devoid of sensuality. Wagner imagined his Elisabeth as an incarnation of religious love, yet she could not be a saint, for Tannhäuser could hardly fall in love with someone who was untouchable. In contrast to the sexually active, experienced Venus, however, she remains unawakened, inexperienced and childlike. That could hardly result in a satisfying character portrait of a woman, let alone a realistic one.

Elena Zhidkova (Venus), Tannhäuser, Bayreuth 2019 | Carlo Dolci, Mater Dolorosa, 1655 | Lise Davidsen, Tannhäuser, Bayreuth 2019

In the Wagner literature, we find time and again the claim that Elisabeth’s is not a ‘fractured’ character. Compared with Tannhäuser’s own vacillations between two different women, that may well be true. But a woman who is supposed to be transformed into a ‘pure angel’ would hardly be allowed an element of sexual desire if she possessed a unified character. If one takes Elisabeth’s undivided concern for Tannhäuser alone as proof of the consistency of her character, then one merely views the plot unquestioningly from Tannhäuser’s perspective. But if one takes Elisabeth’s point of view, then Wagner’s idealization of her suicidal wishes cannot be convincing. She thereby loses what actually makes her alive. She becomes unreal, an artificially created male fantasy. The fact that she turns to Mary is no mere happenstance. The figure of Mary ‘is not enclosed in the psychotic circle of theological historicity and so gives the artist room to play with creations of pure imagination’.

Klimt, Judith and the Head of Holofernes, 1901 (detail) | Tannhäuser, Elisabeth facing Venus, Bayreuth 2019 | Domenico Ghirlandaio, Portrait of a Lady, 1485

Although the character of Elisabeth remains ambivalent, the well-known dichotomies of the time also dominate her music, namely spirit/body, mind/ feeling, culture/nature, and thus also man/woman. When Wolfram sings to the evening star, his song’s solemn, sad momentum is directed towards the good, untouched woman. Although Wagner commentators like to remind us that the evening star is Venus, his expansive, descending, chromatic melody signifies sadness rather than sensuousness. Above it all there hovers an impression of ‘decency’: regardless of his love, Wolfram keeps a certain distance; he refrains from slipping into dangerous waters and remains noble and dignified. While it is often assumed that the knights are bound by a brittle dogmatism, this does not correspond to the music we hear, which is positive in its connotations and depicts the knights of the Wartburg as an honourable band. The contrast of hunting party and pilgrim band presents us with two sides of male activity, namely physical exertion and spiritual contemplation.

The pilgrim band | Daniel Barenboim, Tannhäuser, Staatskapelle Berlin 2014 | The hunting party

Everything that is actively feminine is confined to the sinful, fear-inducing underworld, while feminine passivity comes across as pure and noble.

Marina Prudenskaya, Venus | Daniel Barenboim, Tannhäuser, Staatskapelle Berlin 2014 | Ann Petersen, Elisabeth

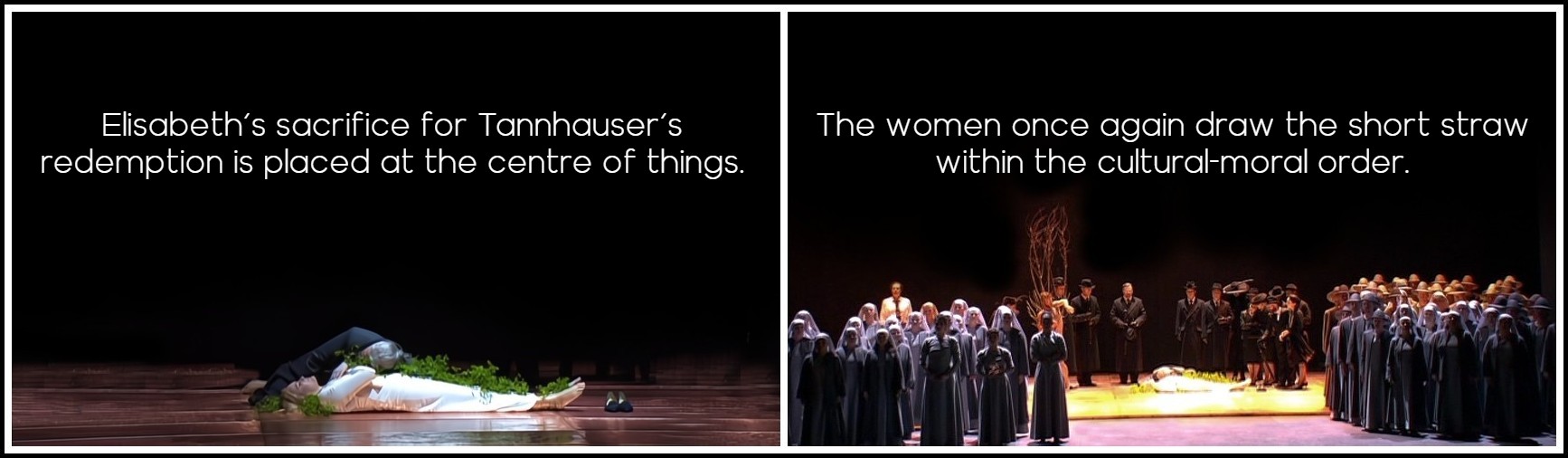

Whereas Tannhäuser is depicted as an active figure, who takes the necessary steps to achieve maturity, Elisabeth remains static and seems almost unalive: she is characterized by emotions that she does not live out, by an uncompromising submission to fate and by a yearning for death. What can Tannhäuser expect from such a woman? Many interpretations of the opera completely ignore the role of the women in it. In an otherwise excellent article, Hans-Klaus Jungheinrich deals only with Elisabeth’s death: ‘What the loving woman could not give him, the dead woman can: heavenly peace, redemption.’ But what would Wagner want to convey to the audience if that were his message? No bourgeois man could seriously wish for the death of his wife. Nor would a dead lover afford any prospect of fulfilment of desire to the creative artist. Death is rather to be understood here in a more symbolic fashion—as the ultimate sign of unshakeable fidelity. That is why Wagner was keen to stress the importance of Elisabeth’s role; in his revised version of the opera he even decided to show her coffin on stage. The dead woman was to be visible to the audience so that the sacrifice she has made will be even more evident. It was not her death that was the central point for him, but the ability of woman to love her lover more than herself. And it is her sacrifice that brings about Tannhäuser’s redemption: ‘It was precisely this that I wanted to stress clearly with the new ending, namely that Tannhäuser is redeemed not by a church that declares itself impotent, but by the boundless love of a woman (despite the church). The staff that grows green leaves comes only from the sacrificial death of Elisabeth: it disavows the church’. So Tannhäuser is moved to repentance not by the knights’ disgust, but solely through the pain of Elisabeth. Her fidelity to him, beyond death itself, is able to free him from his inner turmoil and to redeem him.

Peter Seiffert, Tannhäuser | Daniel Barenboim, Tannhäuser, Staatskapelle Berlin 2014 | Ann Petersen, Elisabeth

Wagner reshaped the end of the plot and discarded the usual configuration, in which Tannhäuser chooses Venus. Instead, Elisabeth’s sacrifice for Tannhäuser’s redemption is placed at the centre of things. The goddess of love is Venus; the God of love leads Tannhäuser to Elisabeth—here the world of the spirit reigns. The women once again draw the short straw within the cultural-moral order. But before her transformation into an angelic being, Elisabeth is indeed a woman of flesh and blood who is able to desire a man. That, at least, offers a ray of hope that Wagner was not wholly dependent on culturally fixed images, but was able to break through them, if only hesitantly. This is the good news. The bad news is that this breakthrough is not borne along by Wagner’s music: by remaining fixed on specific gender aspects in the musical depiction of his characters, Wagner thwarts the possibility of a new evaluation of this work.

Daniel Barenboim, Tannhäuser, Staatskapelle Berlin 2014

EVA RIEGER: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON IMAGES 1 & 3 TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

CHRIS WALTON: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

RICHARD WAGNER IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel, ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

PART THREE CHAPTER 12

̶ What did Tadzio do?

̶ Oh, he was ridiculous! Felt himself possessed of a sudden power, just because he was cheating on his wife. The poor bugger bought himself a wardrobe more fitting for his son, thinking his new look would please me.

̶ And Niels just kept his old jeans?

The glint in your eye is as golden as your Calva.

̶ Sprague, are you jealous?

̶ I’m jealous of his composure, yeah.

̶ Don’t be. You’re a poet. You’re in a whole other register.

̶ Sturm und Drang? I’d rather be cool and calm, like your Marlboro man.

̶ You’re an artist. Much more interesting.

̶ True. The meanders of sublimation can be magnificent.

̶ Indeed.

̶ Do you know, Marietta, if Wagner hadn’t had an affair with Mathilde Wesendonck, he’d never have written Tristan und Isolde?

̶ Yes, I’m aware that art owes a good deal to adultery.

If erotic life makes a world, with you I have a world. But am I capable of the pleasurable relationship?

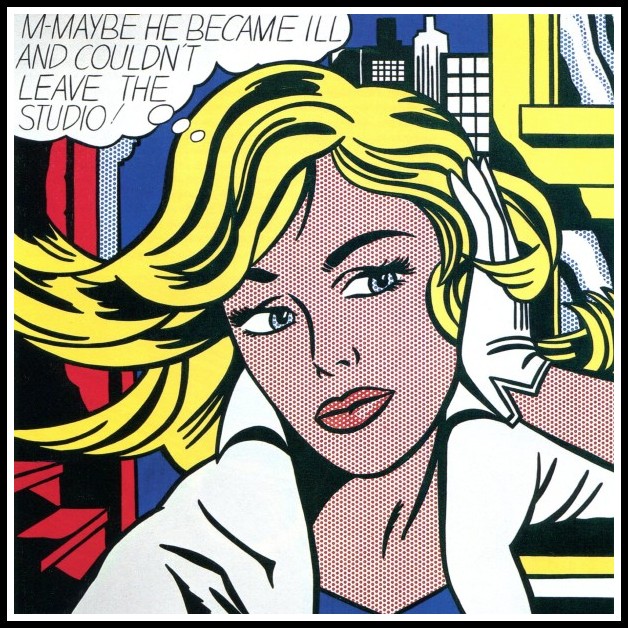

Roy Lichtenstein, M-Maybe, 1965

̶ Was it in Copenhagen that you met, you and Niels?

̶ No, in Sicily. International School of Subnuclear Physics.

̶ Summer school?

̶ Uh-hm. I was the only woman among thirty physicists.

̶ I can imagine the electro-magnetic forces!

̶ Yeah. Poor me, all alone among the dorks looking for quarks.

̶ The strange particle!

̶ Yeah!

In your eyes the sparkle comes to a point: You fix me.

̶ Now listen to me, Sprague: Your desire is more important to me than your desire for me. I will do everything I can to sustain it. That’s my way of loving.

You take my glass and raise it; I take yours and do the same.

̶ To our making up love.

̶ To our…?

̶ ‘Making up love.’

I hesitate an instant, then understand. We clink glasses.

̶ To our making up love.

Liquorice, undergrowth and leather, the last of the Calva reveals a new aroma. Just how potent it was, you’d show me before the afternoon was over.

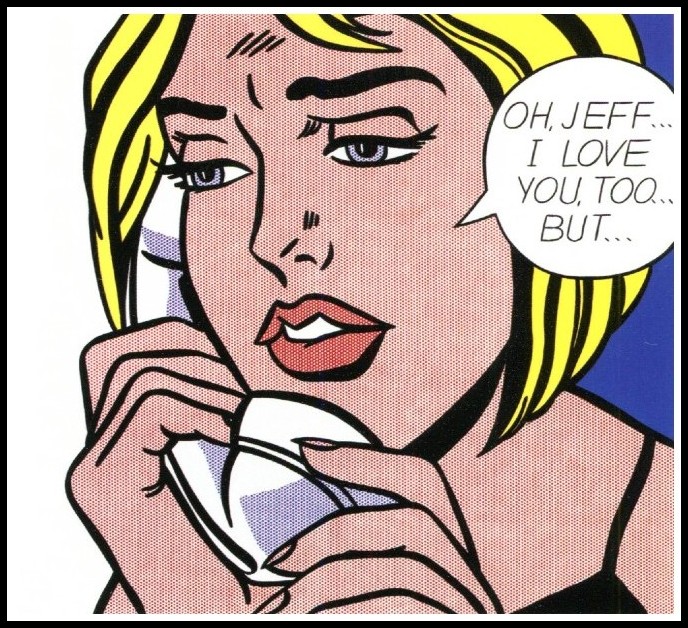

Roy Lichtenstein, Oh Jeff, 1964

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

INTERMEZZO 14: IZOLDA

The bold demeanour of your breasts,

The rose-petal lips of your pussy;

The arch of your instep,

The refinement of your fingers,

The dimples in the small of your back:

They are pavane and bolero,

Madrigal and canticle,

Sonata, concerto and symphony to me.

Yes, your breasts are Ravel, your ass Purcell,

And your pussy, pure Wagner!

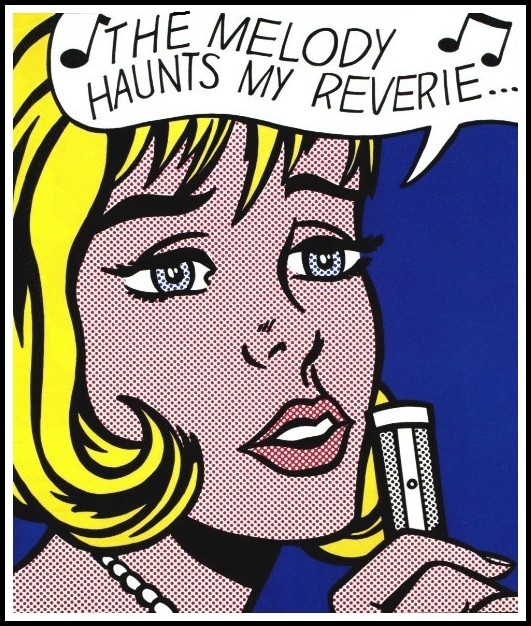

Roy Lichtenstein, The Melody Haunts My Reverie, 1965

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments