PART 2 — III. HUMANWORLD — THE LAST SIX SONGS | IV. CONCLUSION | PHOTO: GILLES BENSIMON, CHRISTY TURLINGTON, 2000

Humanworld

PETER PERRETT: THE FLAME OF INDIVIDUALITY – PART 2: THE LAST SIX SONGS

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY. TO READ PART 1, CLICK OR TAP THE IMAGE BELOW.

7. PETER PERRETT | WAR PLAN RED | HUMANWORLD

War Plan Red, shame it never happened

War Plan Red, it’s a shame

War Plan Red, shame it never happened

War Plan Red, it’s a shame it never happened

Lindbergh’s fascist babies filled Madison Square Garden

War Plan Red, it’s a shame

Stars and stripes and swastikas filled Madison Square Garden

War Plan Red, it’s a shame

As the second plane entered your skin

I felt a chill come from within

Some of my childhood heroes, my family and friends

I’m not ashamed to admit, are Americans

But the so-called free world stands for evil incarnate

So many people ignorant of the reasons for the hate

As the second plane entered your skin

I felt a chill come from within

When people realize there’s no justice in this world

It should come as no surprise that they resort to acts of desperation

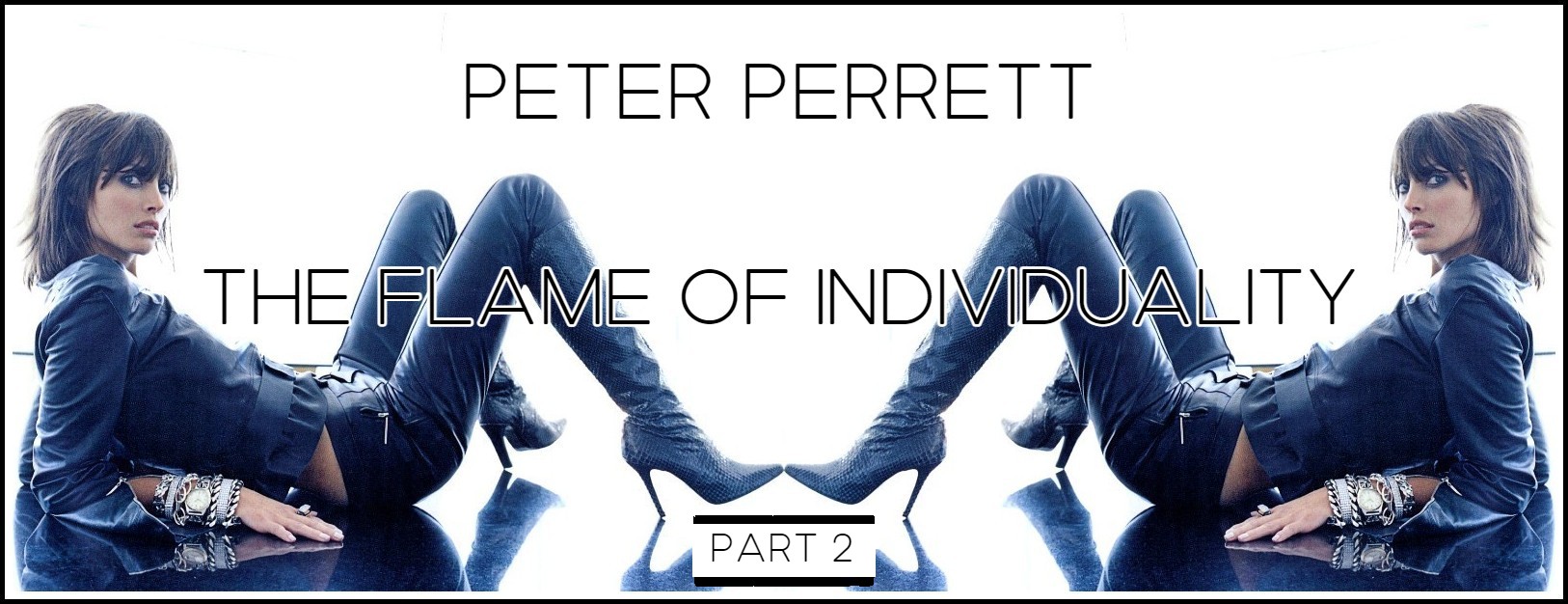

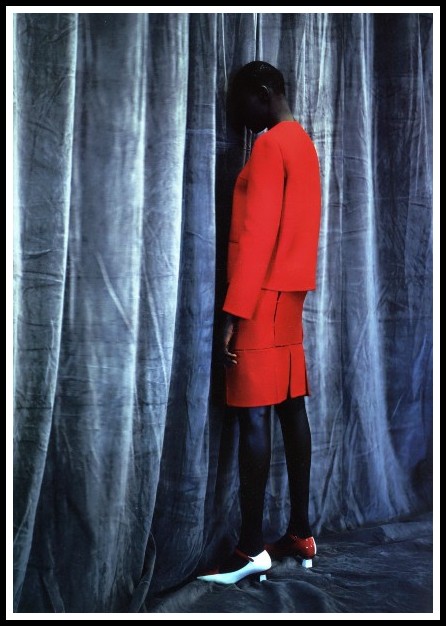

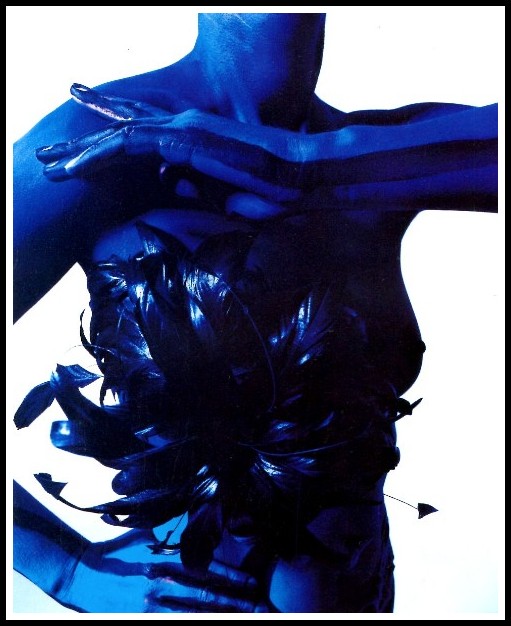

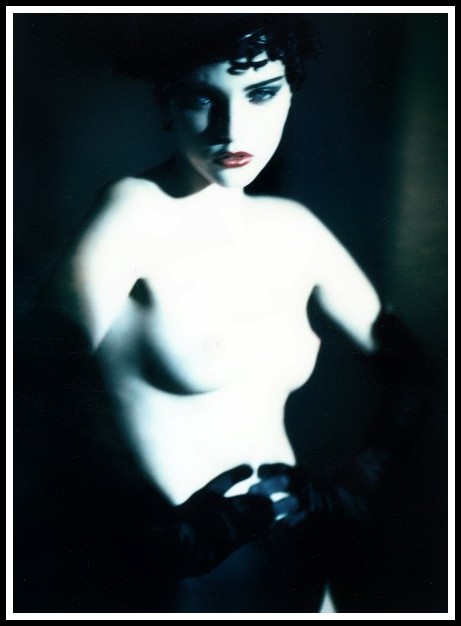

Serge Lutens, Mécanique rouge, 1989

Peter Perrett: I don’t like songs that rant on about political things. Basically, you won’t convert people.1 It’s so easy to get depressed about the state of the world, so I suppose you have to have some sort of safety mechanism to escape from it. For me, I just try to talk to people so that I realize that there is still good in humanity and have faith that it will eventually prevail. Maybe not in our lifetime, but at some point.2 While Peter Perrett adopts a humanistic stance and makes reasoned arguments in his interviews, his anti-Americanism in this lyric—‘The so-called free world stands for evil incarnate’; ‘When people realize there’s no justice in this world / It should come as no surprise that they resort to acts of desperation’—is no more amenable to rational discussion than is any other fossilized discourse.3 That being the case, I have nothing to say about ‘War Plan Red’, except this: It is a superb rock song. Richly textured and beautifully arranged, it transmits an urgent energy to thrilling effect. The musicianship is outstanding, from the drummer’s musicality as he solicits all of his kit to the synth pulses’ alignment with the mania of the lyric, from the throbbing base to the lead guitar licks. Finally, I note that Perrett is as effective in the vicious mode (‘War Plan Red’) as he is in the tender (‘Heavenly Day’).

1 – The Arts Desk Q&A: Musician Peter Perrett

2 – Fear and Loathing interview: Peter Perrett

3 – The one domain where Peter Perrett renounces his individuality and embraces a conformist discourse is that of anti-Americanism.

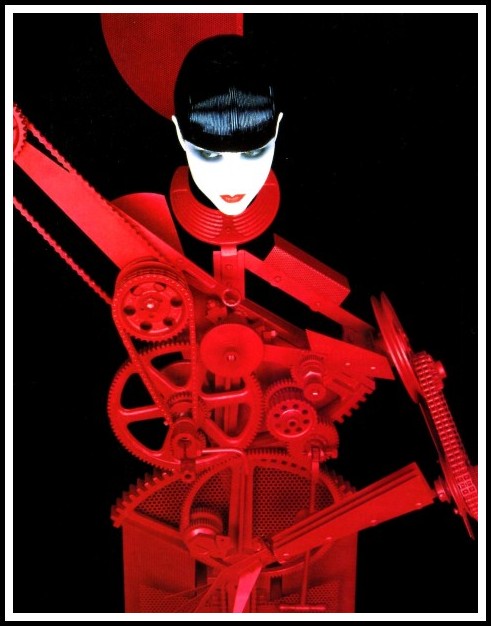

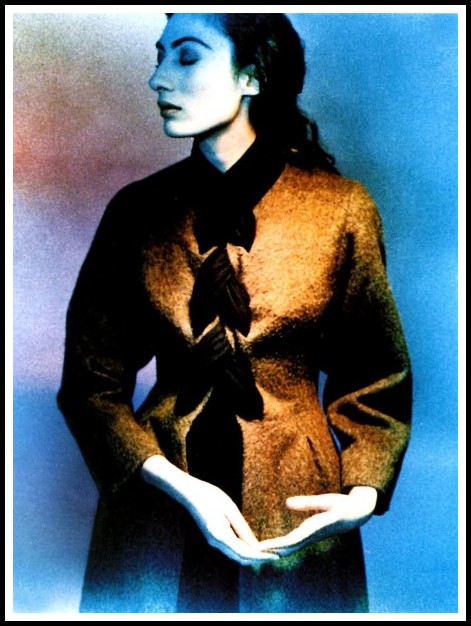

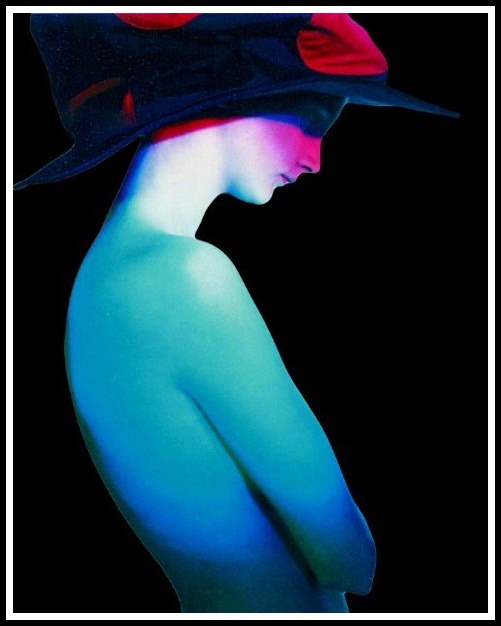

Satoshi Saikusa, Paris 1990

8. PETER PERRETT | 48 CRASH | HUMANWORLD

They want a home they said

Just take another’s instead

One in a cage, the other one dead

They took her cousin and they shot him in the head

I wanna go there

I wanna blow it up

I gotta be there

I wanna do something

They said the night will fall

A shadow over us all

They’re only good when they’re dead

They took her cousin and they shot him in the head

I wanna go there

I wanna blow it up

I gotta be there

I wanna do something

Where did it all go wrong?

Is this a place where we belong?

They said he showed restraint

When she slapped his face

You could tell she was mad as hell

When they came they took her mother as well

I wanna go there

I wanna blow it up

I gotta be there

I wanna do something

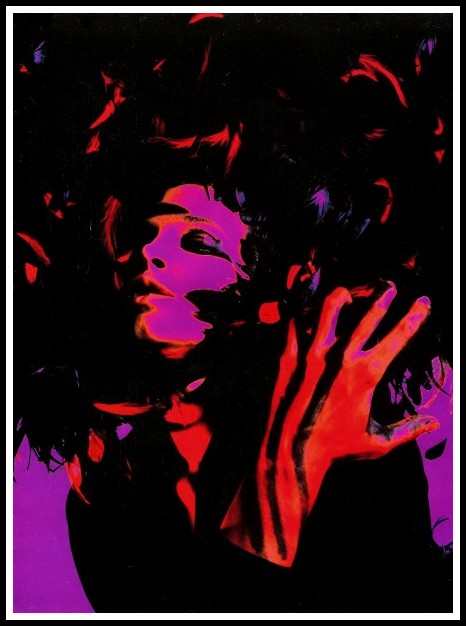

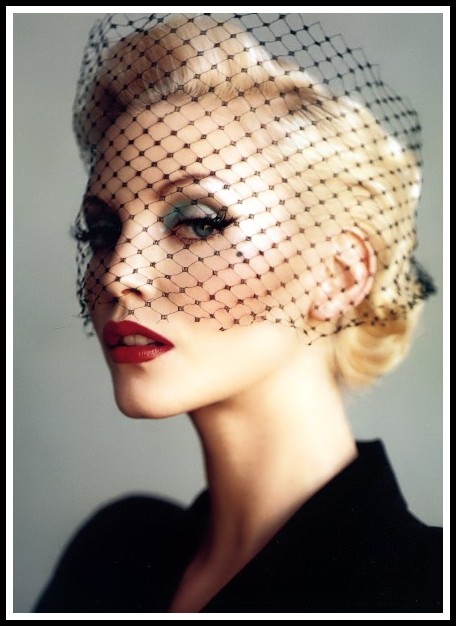

Gilles Bensimon, Alek Wek, 1997

‘48 Crash’ depicts scenes of ethnic cleansing. Where? It could be Bosnia, Myanmar, Darfur, or any number of other regions of the world. My guess, however, is that it is Palestine. Why? Because, given the lyrics, the title ‘48 Crash’ can plausibly be interpreted as referring to the 1948 Palestine War (‘48’) and in particular to the Nakba (‘Crash’)1 and an emblematic event in it, the Deir Yassin massacre.2

1 – This hypothesis is supported by a remark made by Perrett’s Arts Desk interviewer: ‘Perrett explained in detail how he consumes the news via documentaries on Al-Jazeera.’

2 – Daniel McGowan: ‘Early in the morning of Friday, April 9, 1948, 130 commandos of the Irgun and the Stern Gang attacked Deir Yassin, a village with about 750 Palestinian residents. It was several weeks before the end of British Mandate rule in Palestine. The village lay outside of the area assigned by the United Nations to the Jewish State; it had a peaceful reputation. But it was located on high ground in the corridor between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. By the end of the day, over 100 Palestinians, children, women, and men, were dead. It was a massacre, and the participants knew it. The leaders of the mainstream Zionist army, the Haganah, had distanced themselves from their peripheral participation in the attack and issued a statement denouncing the dissidents of Irgun and the Stern Gang just as they had after the attack on the King David Hotel in July 1946. They admitted that the massacre “disgraced the cause of Jewish fighters and dishonored Jewish arms and the Jewish flag.” They played down the fact that their Palmach troops had reinforced the terrorist attack, even though they did not participate in the massacre and looting subsequent to it. Of about 144 houses at Deir Yassin only a few were destroyed. By September, Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Poland, Romania, and Slovakia settled there over the objections of Martin Buber, Cecil Roth, and others, who believed that the site of the massacre should be left uninhabited. The center of the village was renamed Kfar Shaul. The cemetery was bulldozed, and like hundreds of other Palestinian villages to follow, Deir Yassin was wiped off the map.’ Daniel McGowan, ‘Deir Yassin Remembered’ in Daniel A. McGowan & Marc H. Ellis, editors, Remembering Deir Yassin: The Future of Israel and Palestine (New York: Olive Branch Press / Interlink Publishing, 1998) pp. 3-4

Gilles Bensimon, Alek Wek, 1998

‘They want a home they said / Just take another’s instead’: Right from the first line of the lyric, the Palestine hypothesis is affirmed. Indeed, establishing a ‘home’ in Palestine for the Jewish people was the central tenet of Zionism. ‘Just take another’s instead’ can refer not only to the Nakba, but also to the continuing Israeli colonization of the West Bank, characterized by an insidious form of harassment and under-the-radar violence apt to arouse indignation: ‘I wanna go there / I wanna blow it up / I gotta be there / I wanna do something’. The protagonist in the song can no longer bear to stand idly by, he wants to ‘do something’—a stance that, ironically, brings to mind Raul Hilberg’s book on the Holocaust, Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders. ‘One in a cage’ may refer to a Palestinian in an Israeli jail, while ‘They’re only good when they’re dead’ is characteristic of the ethnic cleansing mentality. ‘They said the night will fall / A shadow over us all’ refers, I conjecture, to the fact that violence begets violence and diminishes the humanity of all involved. ‘Where did it all go wrong? / Is this a place where we belong?’: This line would suggest an Israeli is questioning the status quo; if so, it is the only line that offers a glimmer of hope in this tragic conflict. ‘48 Crash’ may first come across as a throwaway song; as I’ve tried to demonstrate, it is anything but that. Whether or not listeners interpret it as the expression of indignation that it is, the fact remains that Peter Perrett’s refusal to be a complacent bystander—even if that refusal only takes the form of a two-minute rock song—testifies to the vigor of his individuality.

Gilles Bensimon, Alek Wek, 1997

9. PETER PERRETT | WALKING IN BERLIN | HUMANWORLD

She’s walking in Berlin, she looks a bit like you

Reminds me of the way you dressed

She walks a bit like you

She’s walking in Berlin, she looks a bit like you

Could never be that good

But close enough to work for me

She’s walking through the service station

Trucks parked up for the night

She’s walking in the sunshine

She walks the day, she walks the night

She’s walking in Berlin

She’s walking in the street, cars are passing by

She really owns the street, you know she owns your eyes

She’s walking through the service station

Trucks parked up for the night

She’s walking in the sunshine

She walks the day, she walks the night

She’s riding in a car, she’s riding in a car

She’s walking in the street

Now she’s riding in a car

She’s walking in Berlin

Walk away

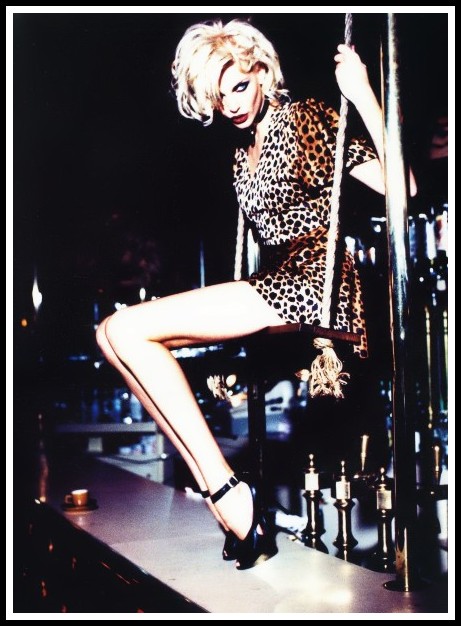

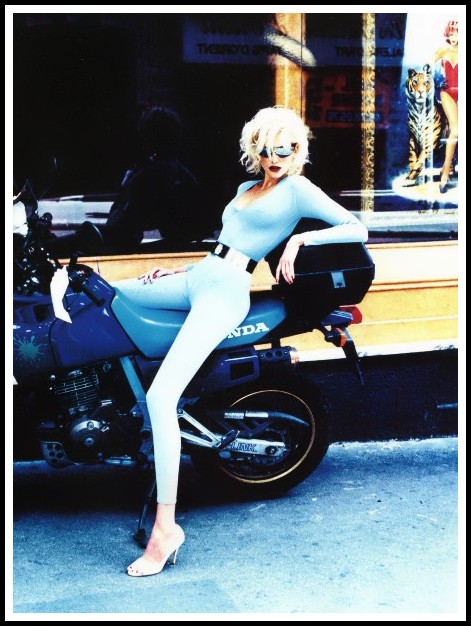

Mario Testino, Nadja Auermann, 1995

‘Walking in Berlin’ is a breezy rocker set to the beat of a brisk walk. A woman is doing the walking; a man, beguiled, is watching her. The play of the male gaze and the female reception of it: that is the vignette this song stages. In Berlin,1 a man (the singer) sees a woman who ‘looks a bit like you’. Thus we learn there are three actors in this ‘film’:2 the woman walking, the man watching, and the woman the man is remembering as he watches the woman walking. The woman walking is both real (she is physically active in the world) and a fantasy (animated by the man’s desire, she struts the stage of his mental theatre). She reminds the man of the way the remembered woman dressed. Perrett might have been more bold and specified what exactly in her dress triggered the association—the sleekness of her black tights, the kitten heels of her ankle boots, or the silken fall of her off-the-shoulder blouse? In other words, he might have revealed to us the man’s fetish, for in the male gaze, fetishism invariably accompanies voyeurism.3

1 – Where Perrett had been gigging after the release of How the West Was Won. See Peter Perrett interview, Loud and Quiet

2 – Cinema, indeed, is the ideal technology for staging the play of the gaze. Here, Perrett’s lyrics make it easy for the listener to convert the verbal to the visual.

3 – See, for example, E. Ann Kaplan, ‘Is the Gaze Male?’ in E. Ann Kaplan, editor, Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera (London & New York: Methuen, 1983) pp. 23-35.

Ellen von Unwerth, Nadja Auermann, 1994

‘She’s walking in Berlin, she looks a bit like you / Could never be that good / But close enough to work for me’: the walking woman’s resemblance to the remembered woman is sufficient to turn on the man. The remembered woman, one supposes, is no longer sexually accessible, but thanks to the walking woman the man can now, in fantasy, regain access to her. ‘She’s walking through the service station / Trucks parked up for the night’: What woman walks among parked trucks at night? A whore, of course. And so the singer—prompted by a sudden intrusion of reality, perhaps—accepts that he’ll have to go home with his hard-on.1 ‘If I can’t fuck her, let some trucker have her’: in his subconscious, in my speculation, that is his thought.

1 – Leonard Cohen, ‘Don’t Go Home with Your Hard-On’, Death of a Ladies’ Man (Warner Bros. Records, 1977)

Ellen von Unwerth, Nadja Auermann, 1994

‘She’s walking in the street, cars are passing by / She really owns the street, you know she owns your eyes’: the demon of sex won’t let the man go. As for the woman, she is turned on by the man’s gaze, she is turned-on by the truckers’ stares, she is turned on by the turned heads of the car drivers—but only in her fantasy, for in reality, she fears, that would be too dangerous. Perhaps she’s had enough of her Saturday night lover; perhaps, fed up with routine, she longs for adventure. Spurred on by the male gaze, she feels herself powerful, desired and in control, but she knows that state can only last as long as she keeps on walking. And so she walks, walks, walks; ‘she walks the day, she walks the night’, for she realizes that ‘assigned the place of object (lack), she is the recipient of male desire, passively appearing rather than acting; her sexual pleasure in this position can thus be constructed only around her own objectification’.1

1 – E. Ann Kaplan, ‘Is the Gaze Male?’ in E. Ann Kaplan, editor, Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera (London & New York: Methuen, 1983) p. 26

Ellen von Unwerth, Nadja Auermann, 1994

Finally, ‘She’s riding in a car / Now she’s riding in a car’: Has the walking woman hopped into the car of a man with whom she’ll find the sexual adventure she seeks? Or is the car that of her boring Saturday night lover? Either way, the man who’s been watching her is resigned to letting her go: ‘Walk away’. He has enjoyed the fantasy, but he lives in reality. And thus it is that Peter Perrett, in giving voice to his fantasy, reconnects us with our own. In so doing, he leaves us with a heightened sense of being. What more can one ask of art?

Miles Aldridge, Acid Candy, 2008

10. PETER PERRETT | LOVE’S INFERNO | HUMANWORLD

I came up the stairs and you were there, you looked eternal

Our eyes met and I don’t regret crossing swords with love’s inferno

Thought it over and over the whole of the night

And nobody gets out of this alive

The last time I looked into a mirror it cracked

The person I was staring at couldn’t look back

You desecrate the altar you pretend to worship at

The road to redemption never runs straight

When it came to the day of judgement you turned up late

You expected more from Him but God decided not to wait

I came up the stairs and you were there, you looked eternal

Our eyes met and I don’t regret jumping into the inferno

Thought it over and over the whole of the night

But it’s out of my mind once she’s out of sight

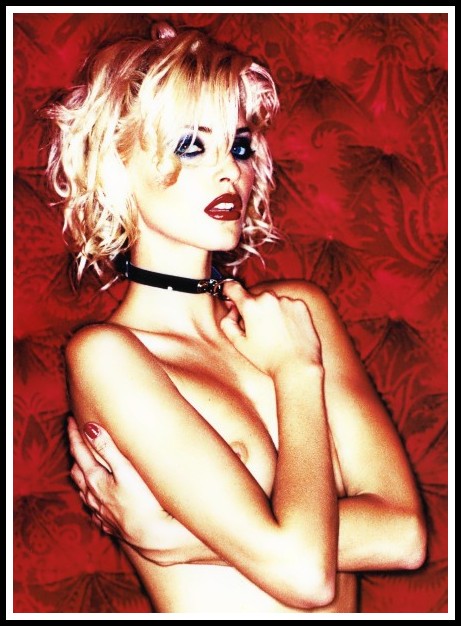

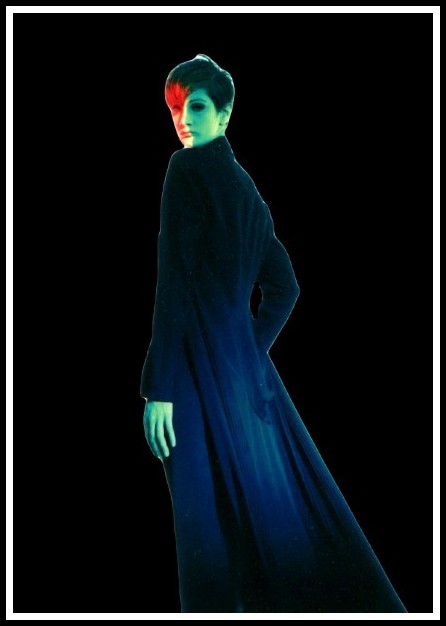

Serge Lutens, 1986

Thematically, ‘Love’s Inferno’ is one of the many Peter Perrett versions of Marlene Dietrich’s ‘Falling in Love Again’:

Falling in love again

Never wanted to

What am I to do?

I can’t help it

Love’s always been my game

Play it how I may

I was made that way

I can’t help it

I’m drawn to women like a moth to a flame

And if my wings burn I know women are not to blame

Falling in love again

Never wanted to

What am I to do?

I can’t help it

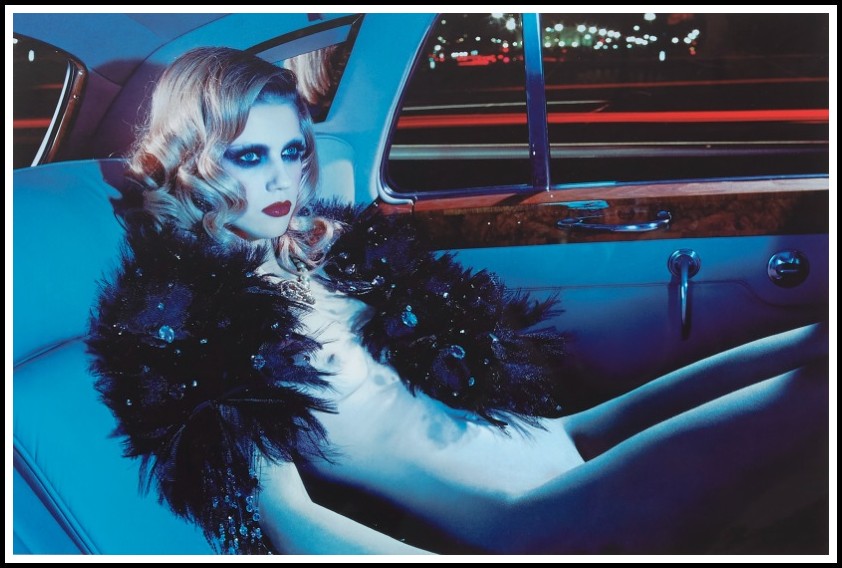

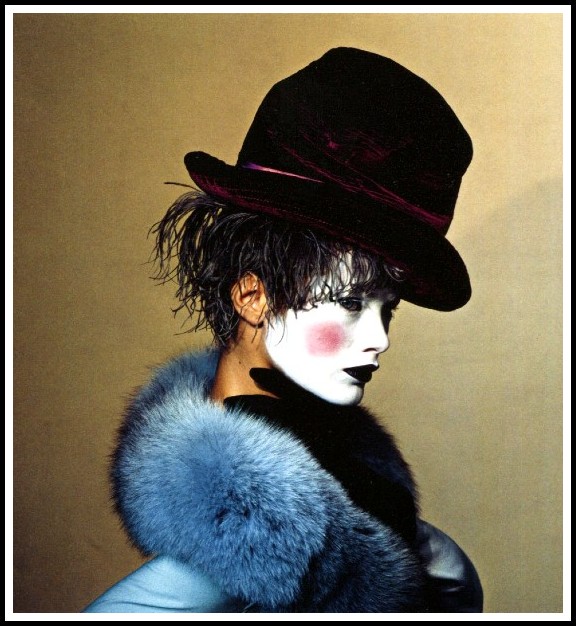

Jean-Baptiste Mondino, 1987

This time Perrett gives a mock-serious twist to the tale. ‘I came up the stairs and you were there, you looked eternal’. Eternal? In the eyes of the man, the woman at the top of the stairs is not a person but a myth: she is the ‘eternal feminine’, ‘elusive, seductive, capricious, and ultimately fatal’ as Sandy Flitterman-Lewis puts it, at once ‘fascinating vision and destructive essence’.1 In this vision, the woman is ‘constructed as eternal, mythical, and unchanging, an essence or a fixed set of meanings’.2 For the man, the ‘eternal feminine’ in a woman represents an opportunity to draw together and unify his fragmented being, to access his unconscious and to fathom the divine. At the same time, she represents an unreal dream of love and happiness, a dream that can lure the man away from reality.3 In ‘Love’s Inferno’, the lyrics make it clear that the man has been ’burned’ by love before and now has learned from his experience: ‘Thought it over and over the whole of the night / And nobody gets out of this alive’. He realizes there are diminishing returns from ‘crossing swords with love’s inferno’; still, he ‘doesn’t regret’ doing so again.

1 – Sandy Flitterman-Lewis, ‘Fascination, Friendship, and the “Eternal Feminine,” or the Discursive Production of (Cinematic) Desire’. The French Review, Vol. 66, No. 6 (May, 1993), p. 942 & p. 944

2 – Annette Kuhn , cited in Flitterman-Lewis, ibid.

3 – See ‘Feminine, the Eternal’ in Jean Chevalier & Alain Gheerbrant, The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols, tr. John Buchanan-Brown (London: Penguin Books, 1996) pp.374-75

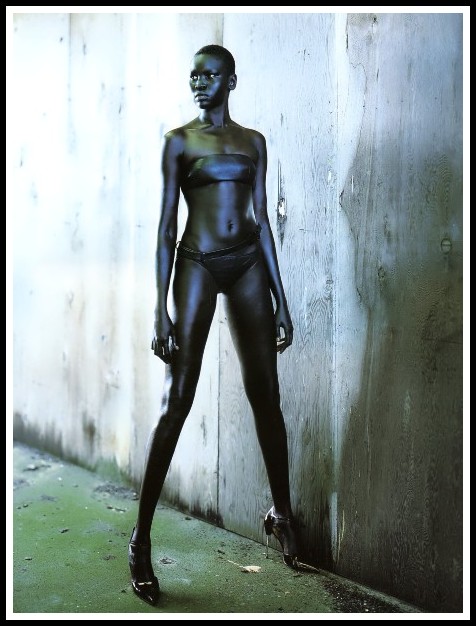

Satoshi Saikusa, Paris 1990

Why doesn’t he regret it? My guess is because the encounter always holds out the promise of surprise: if not a dream of transcendence, if not a pleasurable experience in bed, then at least an opportunity to learn something about oneself: ‘The last time I looked into a mirror it cracked / The person I was staring at couldn’t look back’. We notice the singer says ‘I’, but as we’ve seen in other songs we’ve examined, even when he shifts to ‘you’ he still means ‘I’: ‘You desecrate the altar you pretend to worship at’, the altar being, perhaps, the ‘eternal feminine’. And to anyone familiar with Perrett’s biography, the verse, ‘The road to redemption never runs straight / When it came to the day of judgement you turned up late / You expected more from Him but God decided not to wait’ seems singularly applicable to himself: here too, ‘you’ is really ‘I’. Overall, then, this encounter at the top of the stairs,1 this encounter between the man-pilgrim and the ‘eternal feminine’, has not been productive. On the spectrum of the eternal feminine’s ambiguity, the man finds himself much closer to the pole of repulsion than to that of attraction. We sense he’s undergone some unpleasant experience; we sense it has to do with the vicissitudes of desire and the challenges of aging. ‘Falling in Love Again’: The moth is still attracted to the flame—‘[he] can’t help it’; he still needs to think it ‘over and over the whole of the night’, but this time ‘it’s out of my mind once she’s out of sight’. Over this particular instance of obsession, then, he achieves something of a victory.

1 – The stairs being, of course, the axis mundi the hero ascends once he’s endured his ordeals in the underworld.

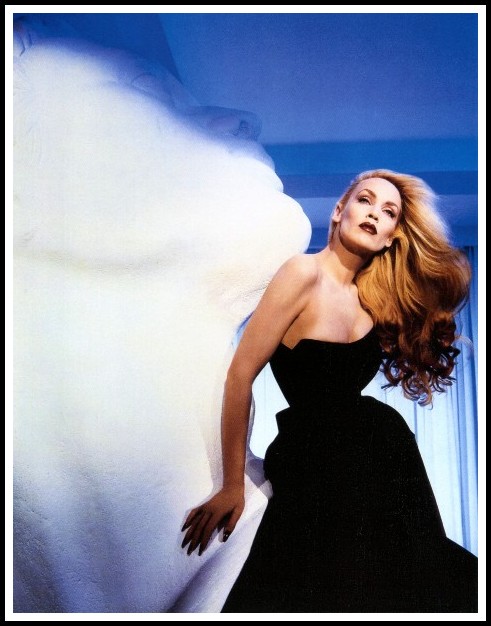

Thierry Mugler, Jerry Hall, 1995

Before leaving ‘Love’s Inferno’, it’s worth returning to the notion of ‘eternal’ as seen in the dynamics of the song. The phenomenon of ‘falling in love again’ (and again, and again) could be illuminated by psychoanalysis, where Freud’s concept of the ‘compulsion to repeat’ would prove particularly useful. Even if sufficient biographical facts were available, however, ethically, attempting such an analysis here would be unacceptable. I will therefore turn to Nietzsche instead: his concept of ‘eternal return’ is intriguing. ‘Yes’, you may be thinking, ‘but is it useful for understanding Perrett’s lyrics?’ I will leave you, dear reader, to consider the following citations yourself, and then to make up your own mind.

‘Eternal return’ is the Nietzschean myth of history depicted as working in a series of never-ending repetitive cycles. Nietzsche thought the realization of this truth would encourage each individual to consider their decisions carefully, in order to ensure that their lives were worth repeating. The doctrine has been endlessly interpreted as an ethical challenge (only do those things you feel you could happily repeat), and as an aesthetic stimulus (construct your life as an aesthetic whole, so its repetition is worthwhile).1

Let us therefore agree that the idea of eternal return implies a perspective from which things appear other than as we know them: they appear without the mitigating circumstance of their transitory nature. This mitigating circumstance prevents us from coming to a verdict. For how can we condemn something that is ephemeral, in transit? In the sunset of dissolution, everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia, even the guillotine.2

I am content to live it all again,

and yet again…

I am content to follow to its source

Every event in action or in thought;

Measure the lot; forgive myself the lot!

When such as I cast out remorse

So great a sweetness flows into the breast

We must laugh and we must sing,

We are blest by everything,

Everything we look upon is blest.3

1 – Dave Robinson, Nietzsche and Postmodernism (Cambridge UK: Icon Books, 1999) pp. 68-69

2 – Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, quoted in Michael Tanner, Nietzsche: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2000) p. 63

3 – W.B. Yeats, from ‘A Dialogue of Self and Soul’, quoted in Michael Tanner, Nietzsche: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2000) p. 63-64

Terence Donovan, Jerry Hall, 1978

11. PETER PERRETT | MASTER OF DESTRUCTION | HUMANWORLD

You used to have a hold on me but now the spell is broken

You used to have a hold on me but now I am awoken

You drew me in against my will, potent siren highly skilled

You are the master of destruction, you specialize in breaking hearts

So many times you fail to realize the pain that you have caused

You are the mistress of seduction, you specialize in the dark arts

So many times you fail to realize the pain that you impart

Give me some strength to resist your existence

Give me some strength to resist your persistence

Trapped in a magnetic field, losing touch with what is real

You are the master of destruction, you specialize in breaking hearts

So many times you fail to realize the pain that you have caused

You are the mistress of seduction, you specialize in the dark arts

So many times you fail to realize the pain that you impart

Don’t know why I keep returning to a place I know that’s bad

You are the master of destruction, you specialize in the dark arts

So many times you fail to realize the pain that you impart

We’re a poisonous combination, we specialize in breaking hearts

So many times we fail to realize the pain that we have caused

Don’t know why I keep returning to a place I know that’s bad

Don’t know why I keep returning to a place I know that’s bad

Don’t know why I keep on yearning for a love I’ll never have

Don’t know why I keep returning to a place I know that’s bad

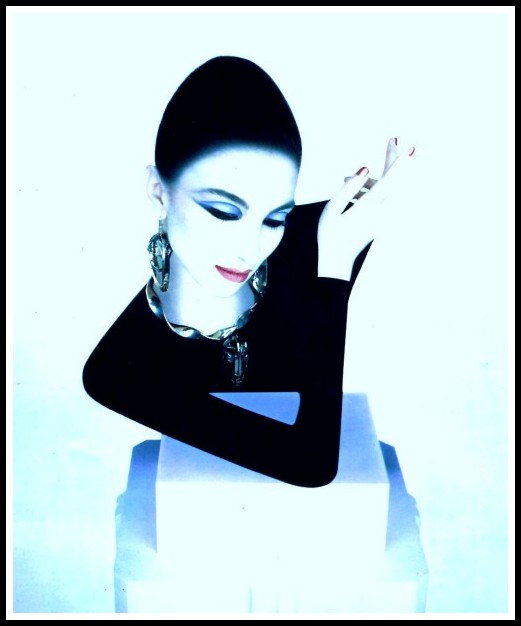

Satoshi Saikusa, Paris 1988

Thematically, ‘Master of Destruction’ comes across as a later stage of ‘Love’s Inferno’. Written by Jamie Perrett,1 the song is simply one of the finest rockers of recent years. Knowing nothing of the circumstances of its composition, I can only remark how uncannily it fits into the album’s scheme of things. The ‘eternal feminine’ is no longer a ‘fascinating vision’ but a ‘potent siren’, stripped down to her ‘destructive essence’. She is a femme fatale, drawing the singer in ‘against his will’. A ‘mistress of seduction’, a practitioner of ‘the dark arts’, she leaves a trail of pain in her wake. The singer believes he has awoken from her spell, but in fact he still feels trapped, ‘losing touch with what is real’. He appeals for ‘strength to resist [her] persistence’; he does not want to be lured away from reality.

1 – Jamie Perrett not only wrote ‘Master of Destruction’, he also produced the song and sings the lead vocal, in addition to doubling up on rhythm guitar with Peter.(Peter Perrett, Fear and Loathing interview).

Javier Vallhonrat, Paris 1987

And then he decides to acknowledge his own responsibility for the situation he finds himself in: ‘We’re a poisonous combination, we specialize in breaking hearts / So many times we fail to realize the pain that we have caused’. Finally, he recognizes the presence of the ‘eternal return’—‘Don’t know why I keep returning to a place I know that’s bad’—and then he identifies his ‘compulsion to repeat’: ‘Don’t know why I keep on yearning for a love I’ll never have’. And thus it is that ‘Master of Destruction’, in its intellectual honesty, refuses to join the ranks of rock songs in which the singer evacuates his vulnerability—the feminine in himself—by a put-down of a woman. To say that the song manifests an ‘ethics of responsibility’ is a grand claim, but it is a claim I shall make. ‘To live outside the law you must be honest’:1 that is what ‘ethics of responsibility’ means. You assume your individuality, you don’t run with the pack, you don’t hide in the crowd. These qualities are those of Peter Perrett, and in ‘Master of Destruction’ Jamie Perret has expressed them brilliantly.

1 – Bob Dylan, ‘Absolutely Sweet Marie’, Blonde on Blonde (Columbia Records, 1966)

Enrique Badulescu, No Direction, 1989

12. PETER PERRETT | CAROUSEL | HUMANWORLD

There was something about you girl, that haunts me

I found that living without you girl, ain’t all it’s meant to be

You know I can’t be your lover, some things are painful to discover

It was like a carousel turning in my heart

I fell in love with you and all the things you said

But it was getting hard to carry on, my love

It was such a nebulous line that we crossed

That separates basic attraction from love at all cost

Our love was made in heaven, it seemed to be forever and

We rode the carousel with music in our hearts

I fell in love with you and all the things you said

But it was getting hard to carry on

I know I should’ve babe, I done you wrong, my love

Trying everything was something I had to do

All the things I only ever tried once I tried with you

I’m empty now that you’re gone, my love

The spirit is broken, we were into love out in the open

Love’s carousel whirled us round and round

I fell in love with you and all the things you said

But it was getting hard to carry on

I know I should’ve babe, I done you wrong, my love

It’s best for both of us that I am gone, my love

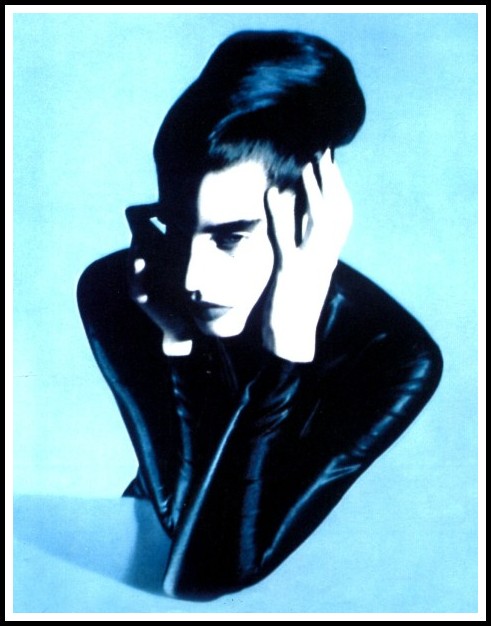

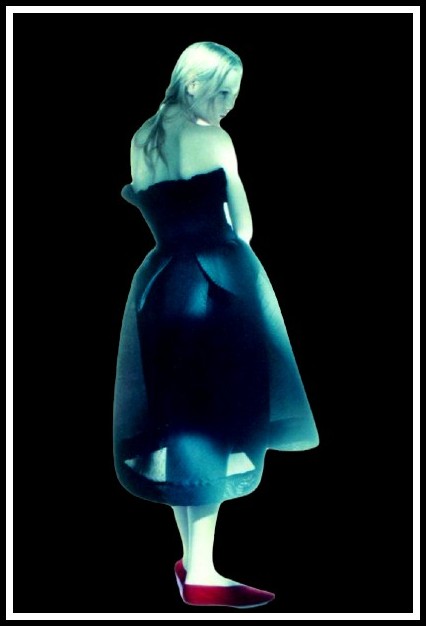

Paolo Roversi, Kirsten, Paris 1987

‘Carousel’ takes us back to ‘Falling in Love Again’. There’s a touchingly wistful air to this song about the break-up of a relationship, yet I find its very tenderness suspicious. Love relationships, no matter how ‘kind’ the leaver, never end so gently.1 Indeed, consider the line, ‘It was getting hard to carry on’. It strikes me as an awfully lame excuse for leaving—just put yourself in the place of the woman being left and imagine how she’d feel on hearing that. Moreover, I imagine she’d resent being addressed as ‘my love’ while being told ‘it’s best for both of us that I am gone’. And I wonder how she’d reconcile ‘Our love was made in heaven, it seemed to be forever’ with ‘Living without you ain’t all it’s meant to be’. The disjuncture between the shallowness of the second line (even allowing for understatement) and the depth of the first is flagrant. ‘Was our relationship real’, the woman may wonder, ‘or was it just a fantasy?’.

1 – For a more realistic depiction of a break-up, just listen to Fionna Apple’s ‘Shadowboxer’ (which I discuss in my essay, Fiona Apple: Ten Songs, Ten Echoes).

Paolo Roversi, Nadja Auermann, 1992

That said, if we accept the lyrics at face value, I can say I find the ring of these lines particularly true: ‘Trying everything was something I had to do / All the things I only ever tried once I tried with you’. Very Peter Perrett—individualized, particularized, evocative; poetic in their very conception. Also very evocative, I find, are the lines, ‘You know I can’t be your lover / Some things are painful to discover’. Only an aging rocker whose erotic past speaks for itself could write that. In contrast, I find very woolly the lines, ‘I’m empty now that you’re gone, my love / The spirit is broken, we were into love out in the open’. I find the verbal sleight-of-hand that turns the reality of ‘I dumped you’ into ‘you’re gone’ rather too complacent, while ‘I’m empty’ and ‘the spirit is broken’ strike me as a disingenuous, if subtle, appeal for pity.

Paolo Roversi, Sasha, Paris 1985

Two final observations. First, the image of the carousel is perfect for portraying the dynamics of ‘Falling in Love Again’: it conveys the breezy lightness of infatuation. Second, I find the line, ‘I fell in love with you and all the things you said’ very telling. You can ‘fall in love’ with how somebody says something or when they say it, but if you ‘fall in love’ with what they say, my guess is you’re ‘falling in love’ with the ‘sameness to yourself’ (what you want to hear) and not with the alterity of the person as perceived through their style (how and when they ‘say’). Indeed, a person’s way of ‘saying’—their style—is far more revealing of who they are than what they might say.1 So I find myself back at square one, finding it difficult to believe that the relationship in ‘Carousel’ was real rather than a fantasy. I envy listeners of this song who don’t understand English: the language won’t impede their access to its beauty.

1 – Adam Phillips argues that ‘lovers are like detectives: the are trying to find something out that will make all the difference… They are notoriously frantic epistemologists, readers of signs and wonders’.* As everyone knows, detectives pay more attention to how and when a suspect says something than to what he/she says. Consider also the song ‘These Foolish Things’: The man fell in love with the woman not because she told him, ‘I enjoy smoking’, but because he saw her ‘cigarette that bears a lipstick’s traces’.

* Adam Phillips, ‘On Love’ in his book On Flirtation (London: Faber & Faber, 1994) pp. 40-41

Paolo Roversi, Sasha, Paris 1985

In the context of my thematic analysis of Humanworld, the lyrics of ‘Carousel’, as I’ve tried to demonstrate, do not stand up well to scrutiny. Lyricists who write alone need to be vigilant about their ‘quality control’. Paul McCartney’s lyrics were much better when he had John Lennon looking over his shoulder. Bob Dylan’s poetic gift has not prevented him from releasing an awful lot of lazy writing. The more bloated U2 became, the more hot air entered Bono’s lyrics. What I’m getting at is this: individuality is reinforced when it confronts alterity; the fresh air from open windows fosters innovation. David Bowie’s body of work is the finest testament to this fact. He regularly changed collaborators, stepped out of his comfort zone, and was diligent in ‘caring for his soul’. The greatness of Peter Perrett’s work is due to a large extent to the fact that it comes out of the ’hot house’ of his mind which, turning base metals into gold, functions like the furnace of an alchemist. In the case of ‘Carousel’, the risks inherent in a hot house materialized in a poor lyric (by Peter Perrett’s standards); individuality became solipsism, and ’care of the soul’ narcissism. So, on balance, what does Humanworld present? Twelve great songs, one lousy lyric. Not bad, hey?

Irving Penn, Carolyn Murphy, 1997

IV. CONCLUSION

Among the women in the singer-songwriter tradition, every decade has thrown up a singularly distinctive artist, one that fiercely upholds her individuality: Laura Nyro in the sixties, Joni Mitchell in the seventies, Tanita Tikaram in the eighties, Fiona Apple in the nineties, Amy Winehouse in the 2000s… Among the men, singularly distinctive individuality as a lyricist/composer in the rock tradition (the one relevant here) is found, of course, in the context of a group: Lou Reed, Tom Verlaine, David Bowie, Bryan Ferry, Robert Smith, Ian Curtis, Peter Perrett… While the excellence of the way all these artists express their individuality is impressive, it is the individuality of Peter Perrett that I find most striking. Why? Because, in addition to individuality in terms songwriting and performance, worldview and way of being, Peter Perrett succeeds in conveying individuality in terms of the ‘taste’ of his intimacy, the ‘color’ of his consciousness, the ‘feel’ of his emotions, the ‘texture’ of his touch, the ‘resonance’ of his hearing and the ‘scent’ of his experience. In this respect he matches Fiona Apple, the greatest active singer-songwriter, in my view, when it comes to honouring individuality in an artistically outstanding manner. This matters because, in a world of cultural conformism buttressed by hyper-consumerism, uncorrupted individuality in conjunction with artistic excellence offer us an opportunity to intensify our own individuality and so gain a heightened sense of being, one that has no need of a culture of perpetual ‘having’ that, ultimately, degrades our humanity. Long live rock! Long live Peter Perrett!

Mario Testino, Karlie Kloss, 2012

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments