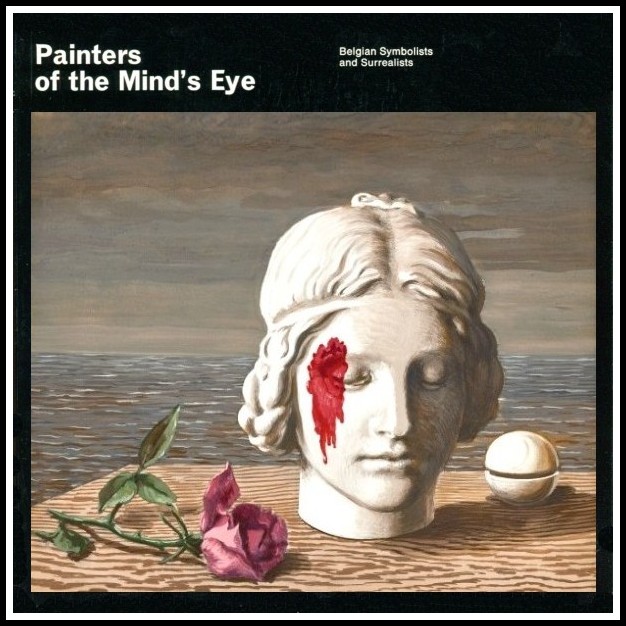

Painters of the Mind’s Eye

BELGIAN SYMBOLISTS AND SURREALISTS: AN OVERVIEW – PART 1

Francine-Claire Legrand

From Francine-Claire Legrand, Belgian Symbolists and Surrealists: Painters of the Mind’s Eye

(New York Cultural Center, Fairleigh Dickinson University & Houston Museum of Fine Arts, 1974) pp. 9-18. Translated from the French by J.A. Underwood.

FRANCINE-CLAIRE LEGRAND

Painters of the Mind’s Eye: Belgian Symbolists and Surrealists, 1974

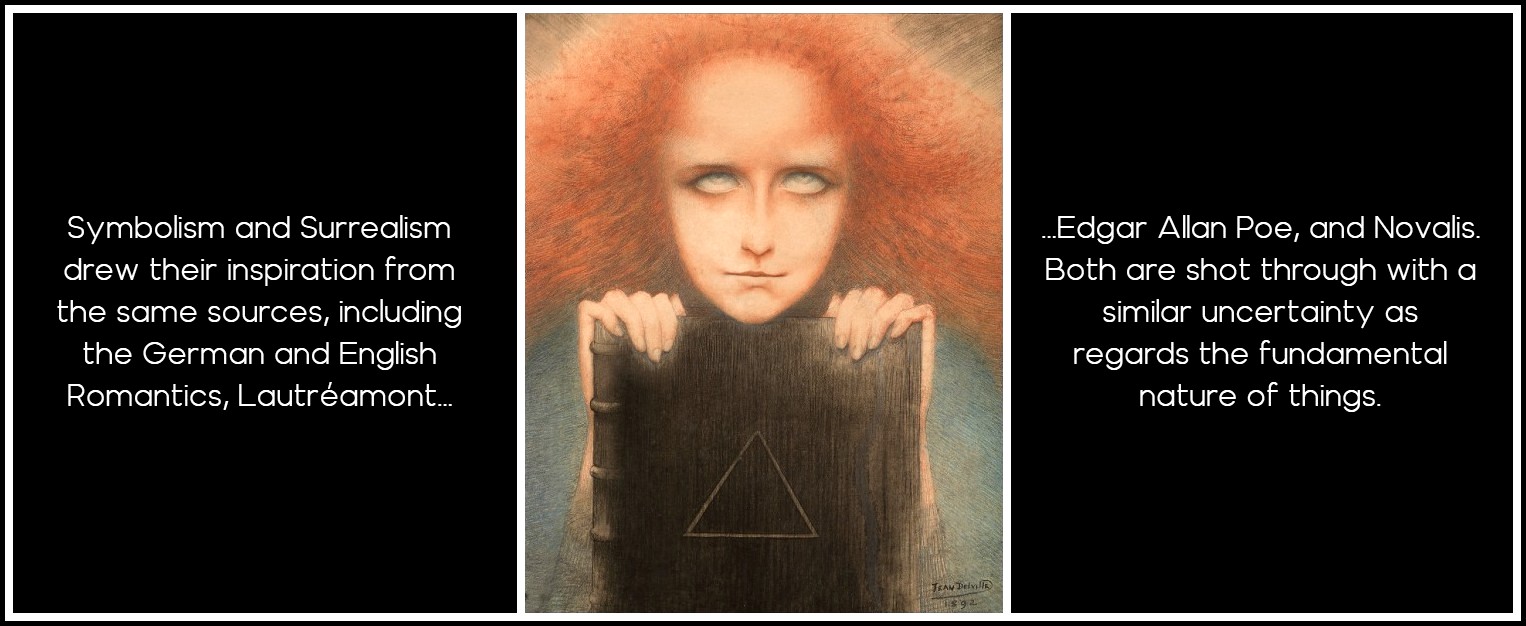

There are disturbing connections between Symbolism and Surrealism. Possibly they arise out of something that both have in common: the domain of the ‘mind’s eye,’ where wonder and imagination roam. Possibly they stem from a common rejection of what Magritte called ‘that dreary part people would have the real world play’. In both Symbolism and Surrealism it is poets that call the tune; in both, imagination triumphs through a tissue of allusion. Imagination imposes the values of dream at the expense of rationalism and determinism, which are held in fruitful check. Submission to the dangers of coincidence, sought after as a virtue by the Symbolists, was practiced as a discipline by the Surrealists. Both Symbolism and Surrealism drew their inspiration from the same sources, including the German and English Romantics, Lautréamont, and Edgar Allan Poe. And Novalis’ affirmation, ‘The world will become dream, and dream become a world’ would seem to apply to the imagery of Surrealism and the iconography of Symbolism equally well, for both are shot through with a similar uncertainty as regards the fundamental nature of things.

Jean Delville, Portrait de Madame Stuart Merrill (Mysteriosa), 1892

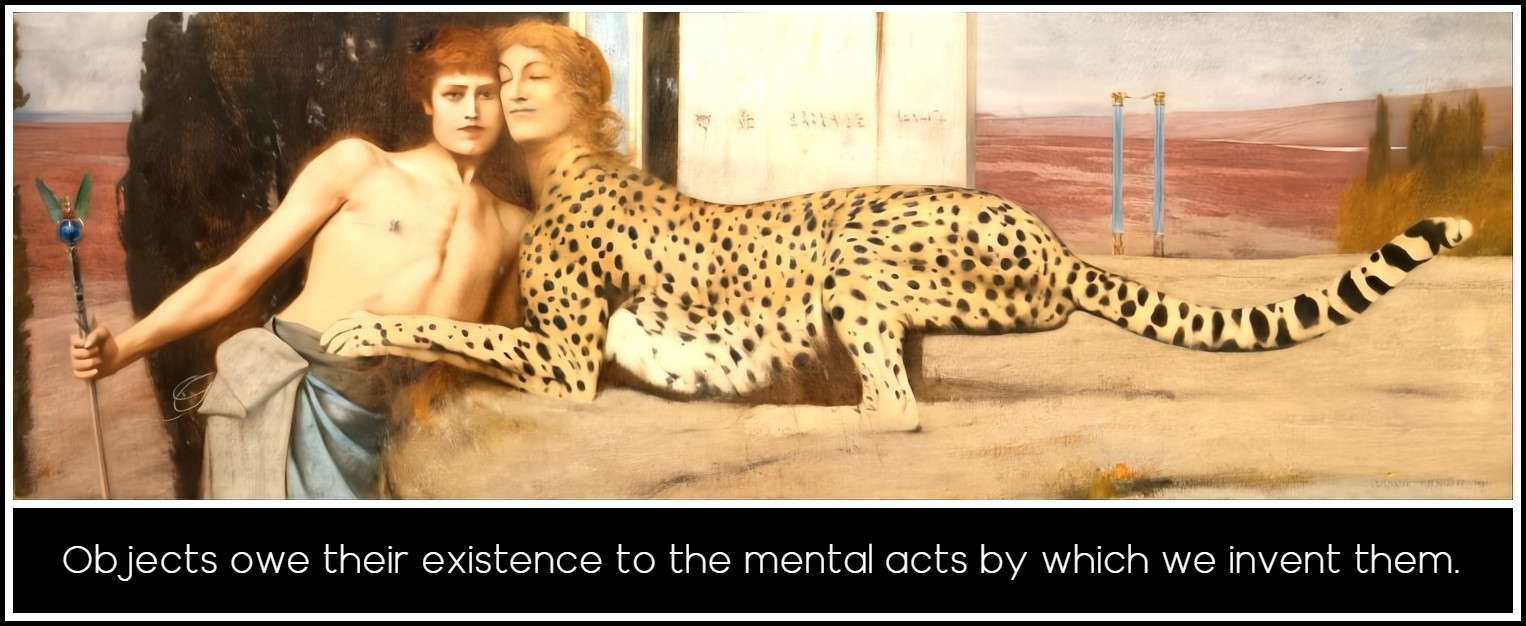

In the words of Paul Nouge, the towering figure around whom the Brussels Surrealist group formed, ‘objects owe their existence to the mental acts by which we invent them,’ and ‘essentially our position could be summed up as follows: an ethic backed up by a psychology colored by mysticism.’ Further: ‘We put the accent on the occult powers of the mind; we believe in these occult powers and in other powers of the mind as yet unknown; we place our faith in the mind’s yet-to-be-discovered potential’, a credo to which the Symbolists could also have subscribed. Likewise the ambiguity in which the Belgian Surrealists are fond of steeping their pictures was already latent in the work of certain precursors, who also sought to represent the invisible by means of the visible. When the Belgian Symbolist poet Charles van Lerberghe wrote that ‘all profound beauty is a mystery, its mysterious aspect being a sign that one has glimpsed it’, was he not suggesting a definition of poetry as a mode of approach to vision and to second sight, a definition wholly in conformity with the aims of Surrealism? The depths of sleep, memory, and silence—those inner realms that would seem to defy pictorial representation—find expression in different ways but with the same urgent insistence in the canvases of both Symbolism and Surrealism.

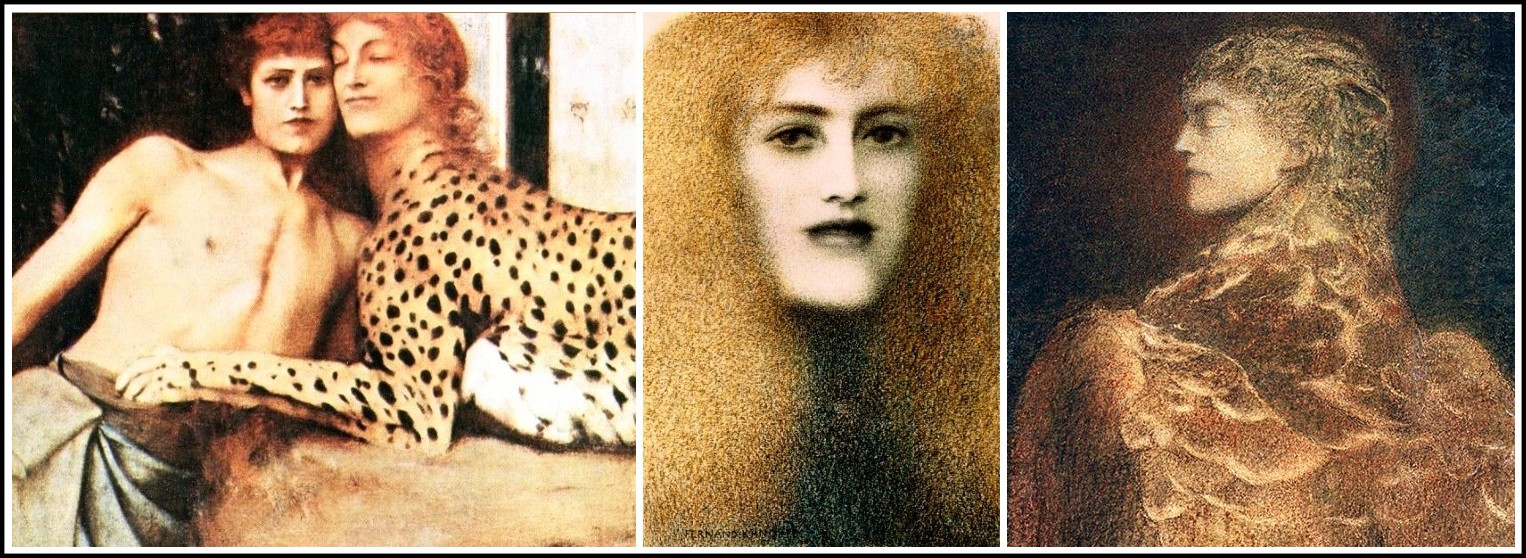

Fernand Khnopff, L’art ou les caresses, 1896

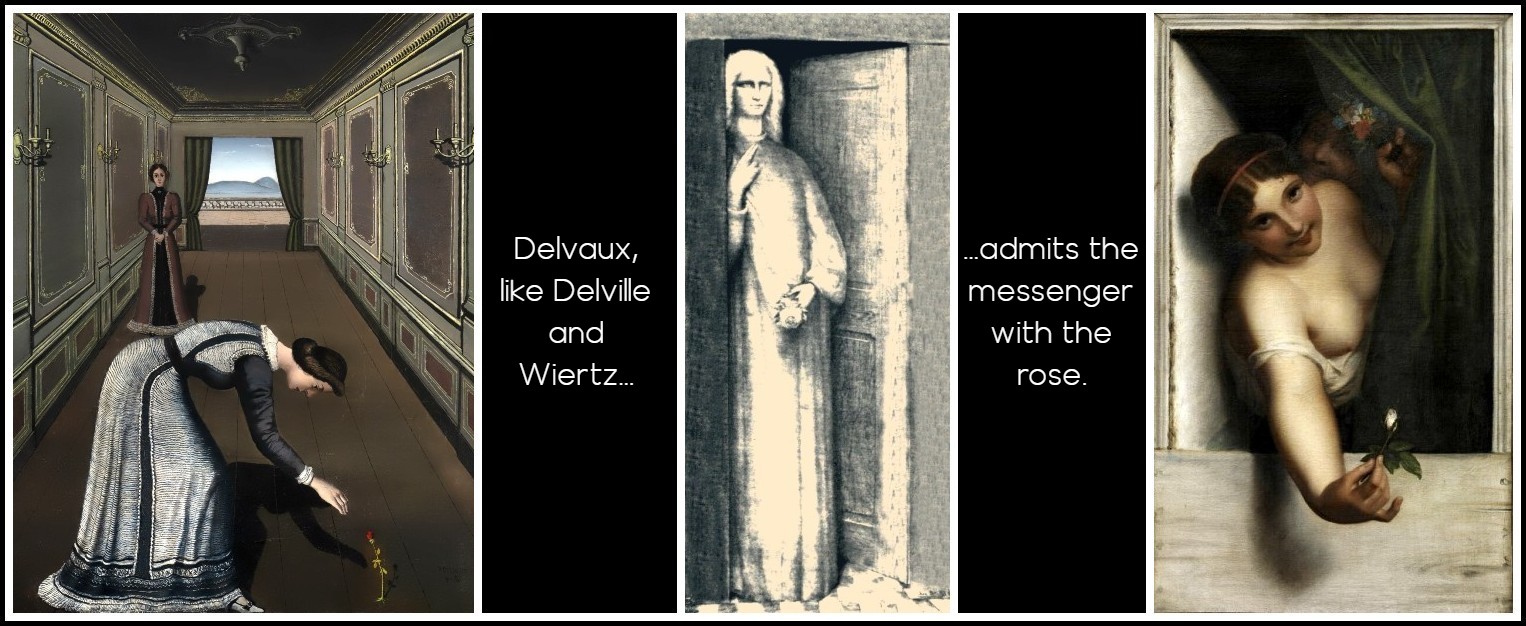

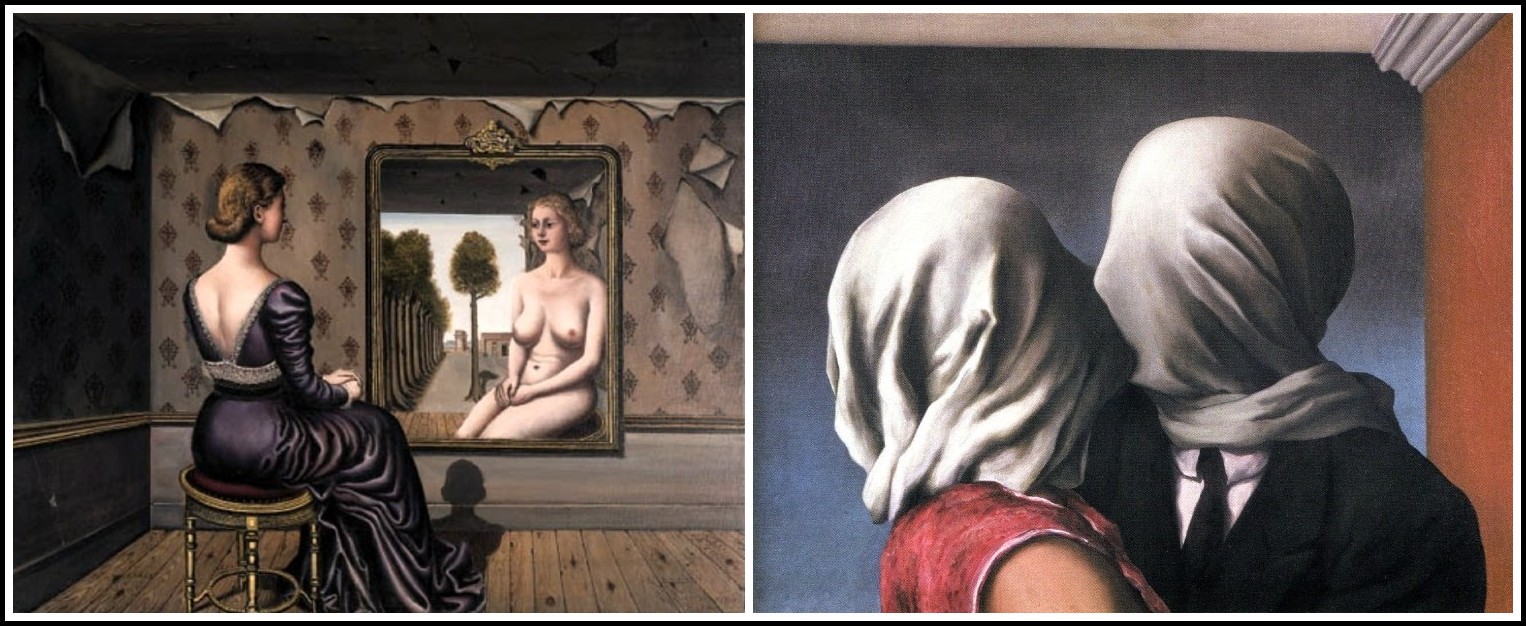

Other subjects beloved of the Symbolists find unexpected echoes in Magritte and Delvaux: nocturnal landscapes, lost, solitary figures viewed from behind, the arrested gesture of the somnambulist, reflections and mirror-effects, trees maturing in the light of stars or streetlamps. The cowled heads of the Lovers and other figures in Magritte are reminiscent of the veiled women of his predecessors. The Symbolists’ doors, closed or ajar, are matched by Magritte’s doors, eaten away by what lies beyond them. At a more simple level Delvaux, like Delville, admits the messenger with the rose.

Paul Delvaux, La rose (Femme à la rose), 1936 | Jean Delville, L’attente, 1903 | Antoine Wiertz, Le bouton de rose, n.d.

In order to understand the extraordinary flowering of Symbolism in Belgium we must look back at what was happening in poetry in the decade 1885-95. If the precursors and early masters of Symbolism were Frenchmen, French-speaking Belgians soon formed a bridgehead of the first importance, enriching Symbolism with the nuances of a more mystical sensibility and coloring its verbal explorations with unsophisticated, occasionally savage echoes that were to contribute toward forming what was to be called ‘the esthetics of the strange’. The poets Albert Mockel, Georges Rodenbach, Maurice Maeterlinck, Charles van Lerberghe, and Émile Verhaeren set up a dialog between Belgian and French circles on the meaning of ‘their retreat into the deepest part of the inner man, into the dark and fantastic interior of dream and vision’. And it was probably the author of these lines, Émile Verhaeren, who first pointed out that this attitude toward ‘a new unknown’ might find pictorial expression in an ‘art of dream and evocation’. A new task fell to painting—to mirror in its turn the emotions, the ‘soul swell’ of the modern age, something that music alone had been able to suggest hitherto, but that literature had now succeeded in capturing.

FERNAND KHNOPFF

Une aile bleue, 1894 | Acrasia Faerie Queen, 1892 | La Méduse endormie, 1896

Romanticism provided the sap by which Symbolism was constantly renewed and without which it would have withered and died. Thus Antoine Wiertz (1806-1865), one of the most astonishing visionaries in Belgian painting, heralded the dreamy hallucinations and convulsive beauty of Jean Delville, for example, or Léon Frédéric, or Henry de Groux. Like the writers Villiers de l’Isle-Adam and Barbey d’Aurevilly, he delighted in macabre visions peopled by ghosts; he was obsessed with death and worshipped Satan, whom he invested with the mystery of the Sphinx.

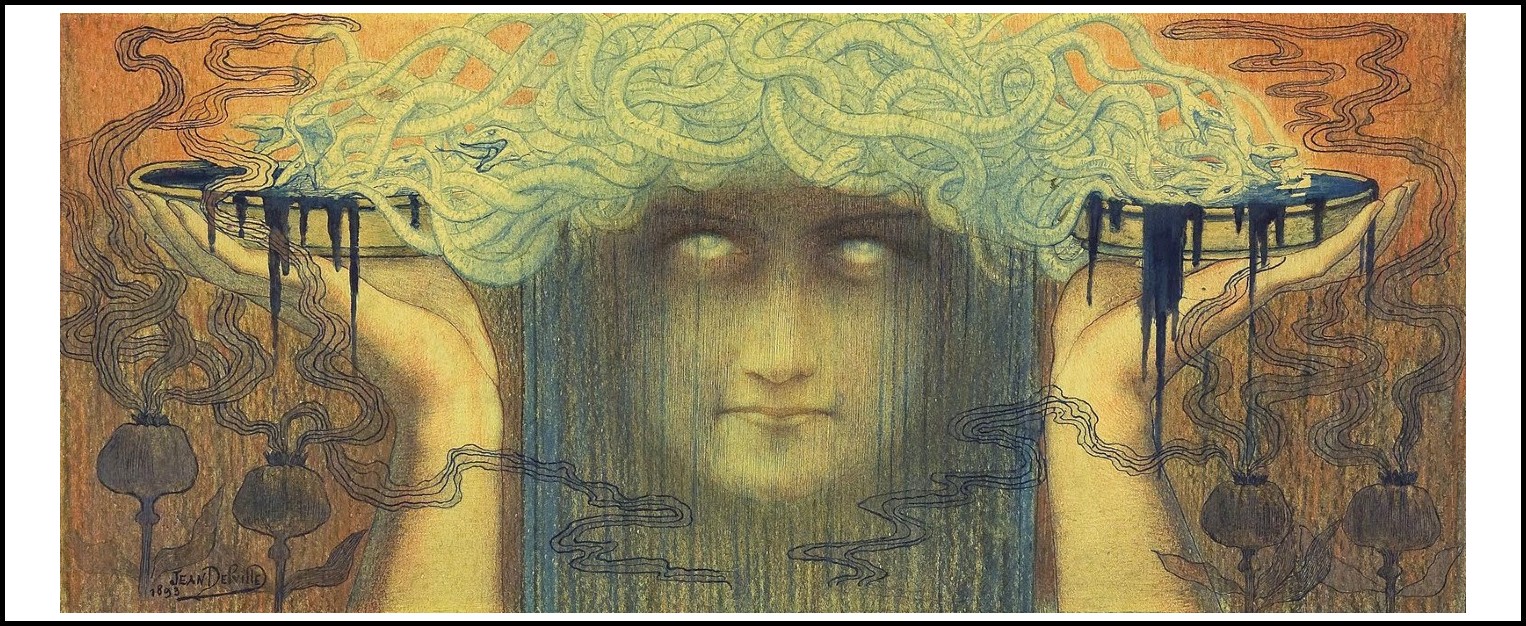

Jean Delville, La Méduse, 1893

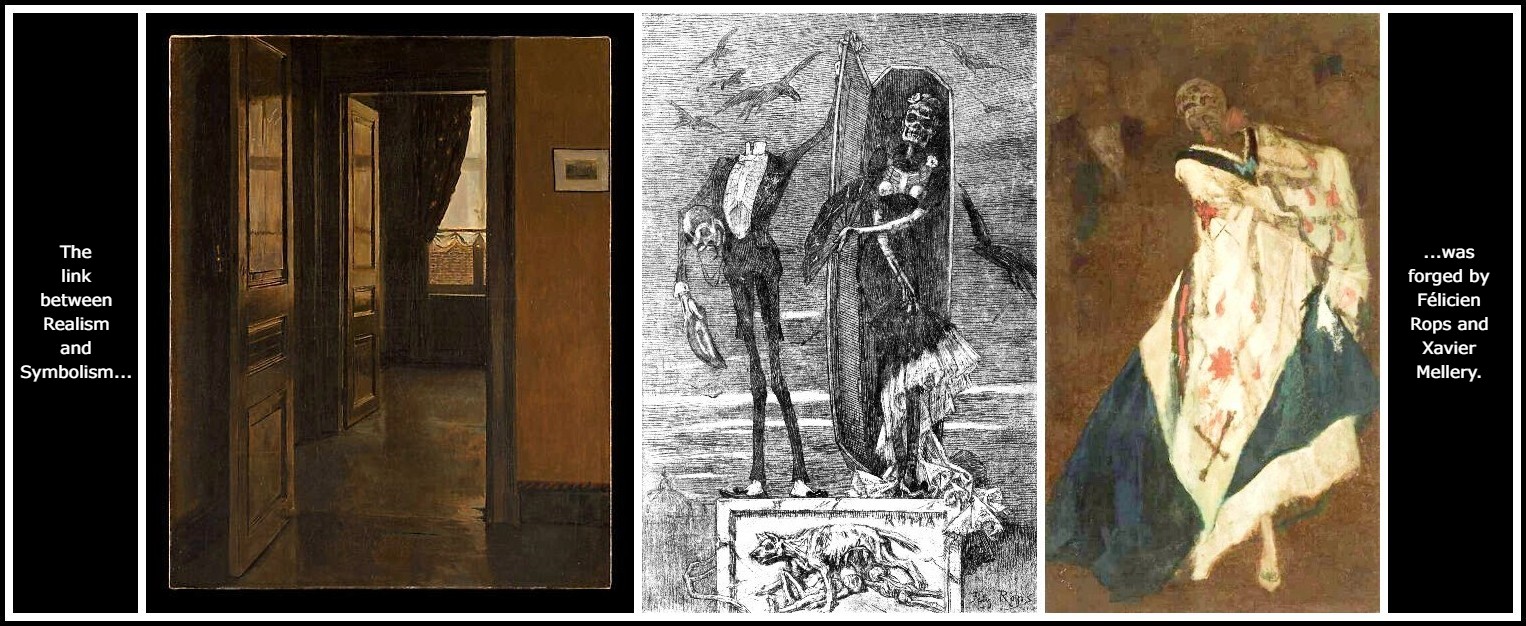

The link between Realism and Symbolism was forged by Félicien Rops (1833-1898) and Xavier Mellery (1845-1921). Rops, the greatest engraver of his day, was held in high esteem by Joséphin ‘Sâr’ Péladan, the ‘high priest’ of the French Rosicrucians. In his frontispiece for Péladan’s Le Vice suprême (1884) he combined the ideas of death and eroticism as he had already done in a famous painting, Death at the Ball. Xavier Mellery’s art crystallized around two contrasting poles. On the one hand, his ambition ran toward large-scale mural decoration, prompting a number of allegories with draped figures against a gold background that show the influence of both Puvis de Chavannes and the Pre-Raphaelites and that strike us today by their quality of motionless undulation in an atmosphere more hospitable to the silent life of symbols than to purely physical being. On the other hand, he left us a series of intimate drawings under the evocative title The Soul of Things in which he captured a certain quality of silence and spiritual concentration with an economy of means worthy of a master.

Xavier Mellery, Les portes, n.d. | Félicien Rops, Le vice suprême, 1883 | Félicien Rops, La Mort au bal masqué, 1885

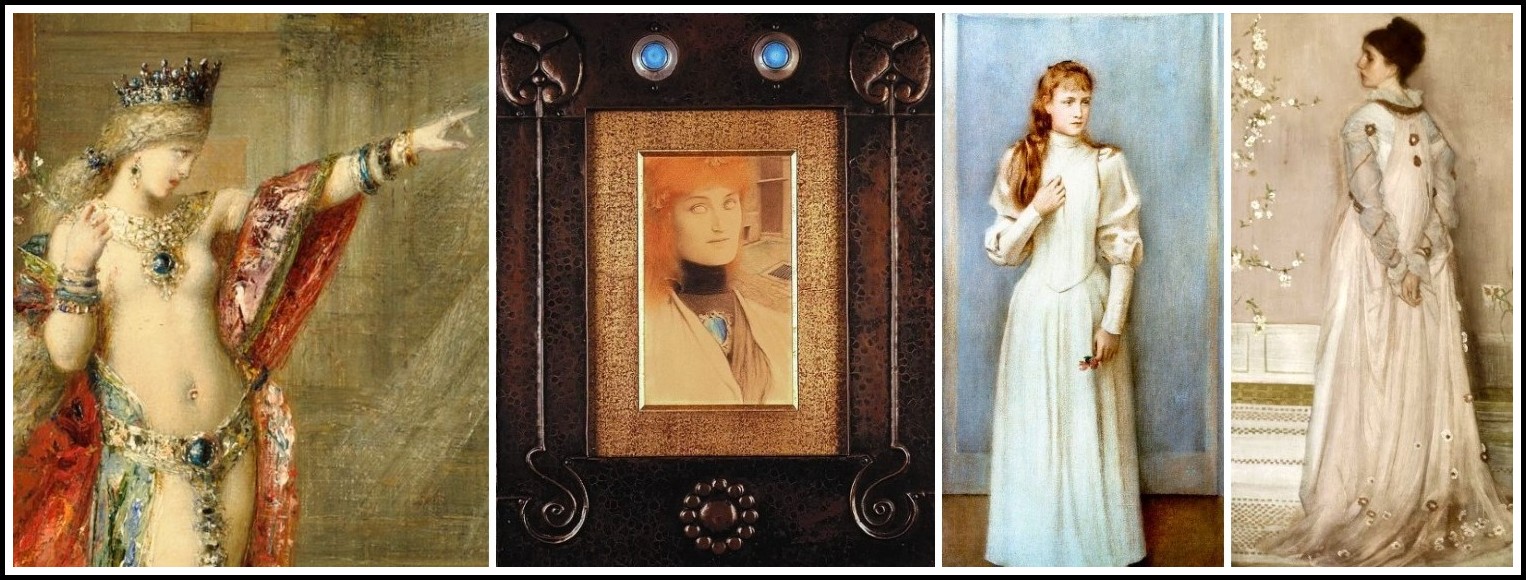

The work of Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921) invites numerous comparisons with literature. Pictorially it shows the influence of Gustave Moreau, then of Whistler…

Moreau, Apparition, 1876 (detail) | Khnopff, Who Shall Deliver Me?, 1896 | Khnopff, Posthumous Portrait of Marguerite Landuyt, 1896 | Whistler, Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink (Portrait of Mrs. Frances Leyland), 1874

…and finally of Burne-Jones.

Fernand Khnopff, Britomart the Faerie Queen, 1982 | Edward Burne-Jones, The Wheel of Fortune, 1879

Fernand Khnopff, Comme des flammes ses longs cheveux roux, 1892

Yet the climate he introduced into the painting of his period was quite unique. He appears to have been haunted by two opposing female types: on the one hand, the angel, the sister-figure, the Muse, incarnation of silence, servant of Hypnos, dispenser of a sleep that opens the door to another world…

Fernand Khnopff, I Lock My Door Upon Myself, 1891 (detail)

…on the other hand, the demon-possessed, perverse, enigmatic, often half-animal woman, the sphinx. His finished technique made him a Parnassian rather than a modern Symbolist.

FERNAND KHNOPFF

L’art ou les caresses, 1896 (detail) | Portrait, n.d. | La Méduse endormie, 1896 (detail)

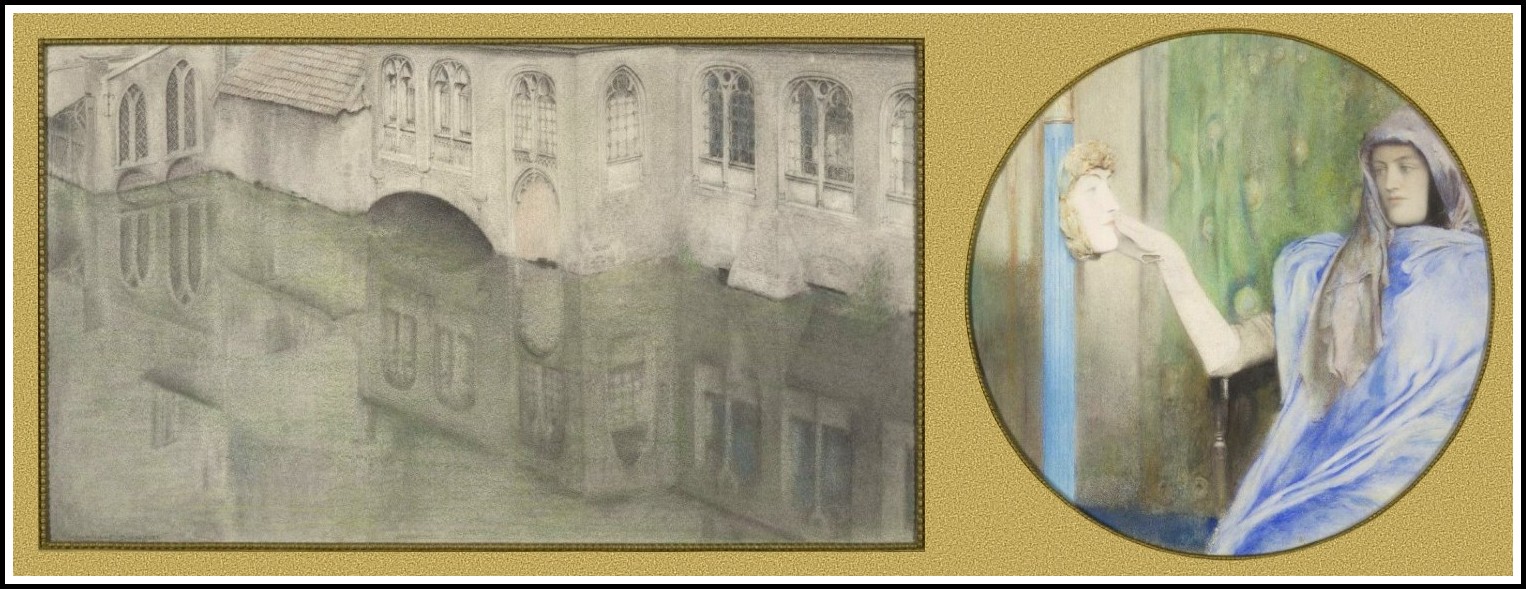

His tall, still figures, with their subtle coloring and mixed techniques, and his landscapes, veritable visions of the impossible that look forward to Surrealism, express a feeling of incommunicability between things, heightened by a dimension that is peculiarly his, the dimension of the daydream, of the memory laden with messages that the past projects into the present, the dimension of Symbolist distance.

Fernand Khnopff, Secret-reflet, 1910

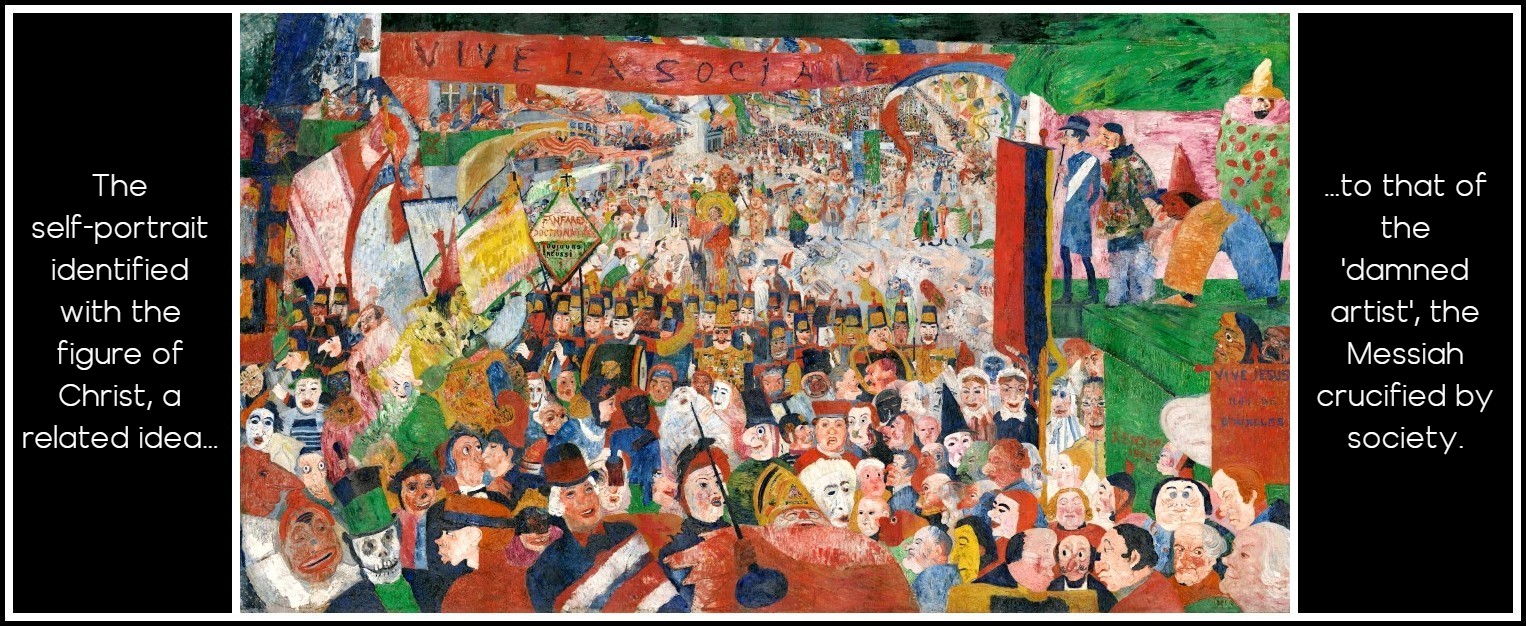

Although the genius of James Ensor (1860-1949) transcended all schools and movements, some of his favorite subjects were among the principal themes of Symbolism: skeletons, masks, and the self-portrait identified with the figure of Christ, a related idea to that of the ‘damned artist’, the Messiah crucified by society.

James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889, 1888

As for Jean Delville (1867-1953), founder of the Idealist Art Circle, an admirer of Péladan, subsequently a convinced Theosophist and painter of astral light, certain of his works require to be interpreted not as allegories of which all the terms add up but as apparitions more embedded in the subconscious than this theorist of a da Vinci-type beauty believed.

JEAN DELVILLE

L’Idole de la perversité, 1891 | L’Ange des splendeurs, 1894 | Parsifal, 1890

The more intimate Symbolist tradition represented by Mellery was continued by William Degouve de Nuncques (1867-1935) and Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946). Writing of Degouve de Nuncques, Andre de Ridder said something that might apply to all these visionaries of the everyday : ‘The Symbolist artist draws from his own deeper self, from his most private life, from his experience and his dreams, from memory and from imagination the meaning with which he seeks to imbue raw nature, the thrill of a more intense humanity with which he sets about investing it.’

WILLIAM DEGOUVE DE NUNCQUES

Paysage (Effet de nuit), 1896 | Nocturne au Parc Royal de Bruxelles, 1897

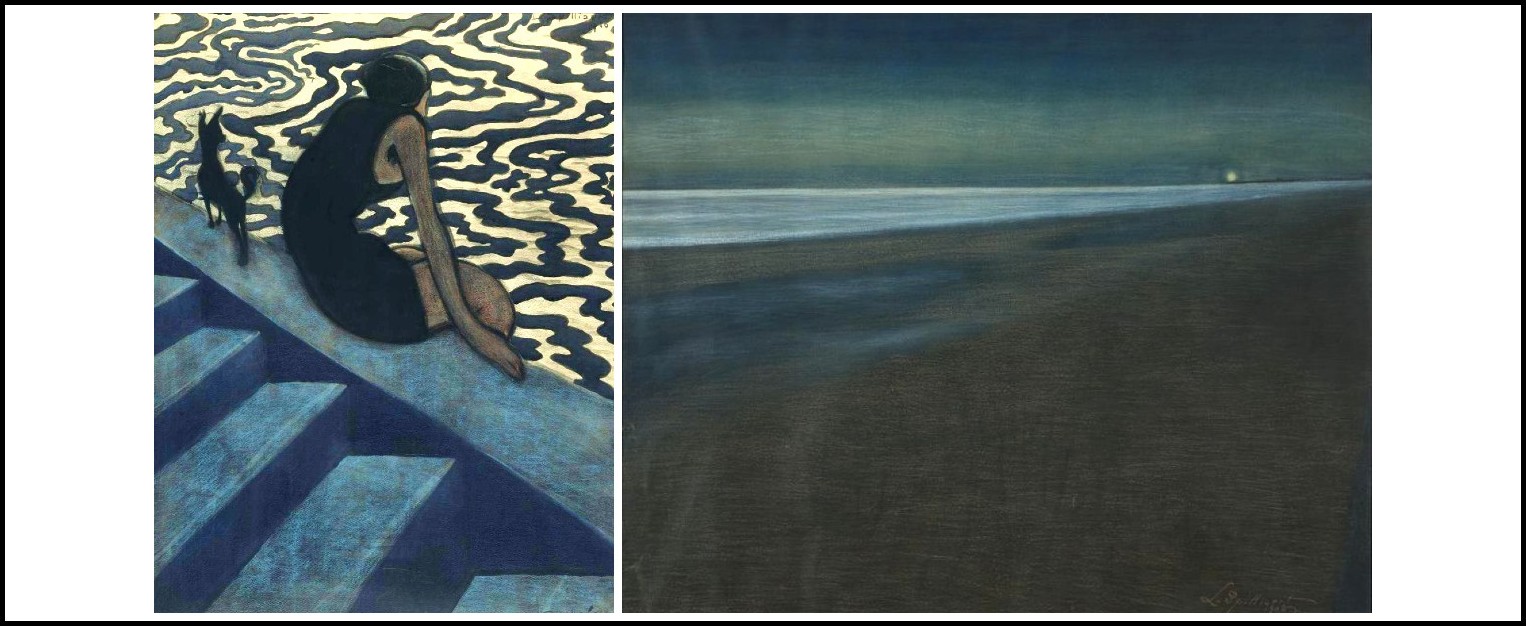

Spilliaert, like Redon and Ensor, began as a painter of darkness. He was a master of nighttime effects, of waiting figures facing the vastness of sea and sky. He admirably digested Ensor’s lesson and yet the strange in his work is rarely haunted by the eery. He used the sinuous, whippy line typical of Art Nouveau but made it join up with itself as in the decorative forms of the Nabis.

LÉON SPILLIAERT

Paysage sous un ciel rouge avec vol d’oiseaux migrateurs, 1919 | La rafale de vent, 1904

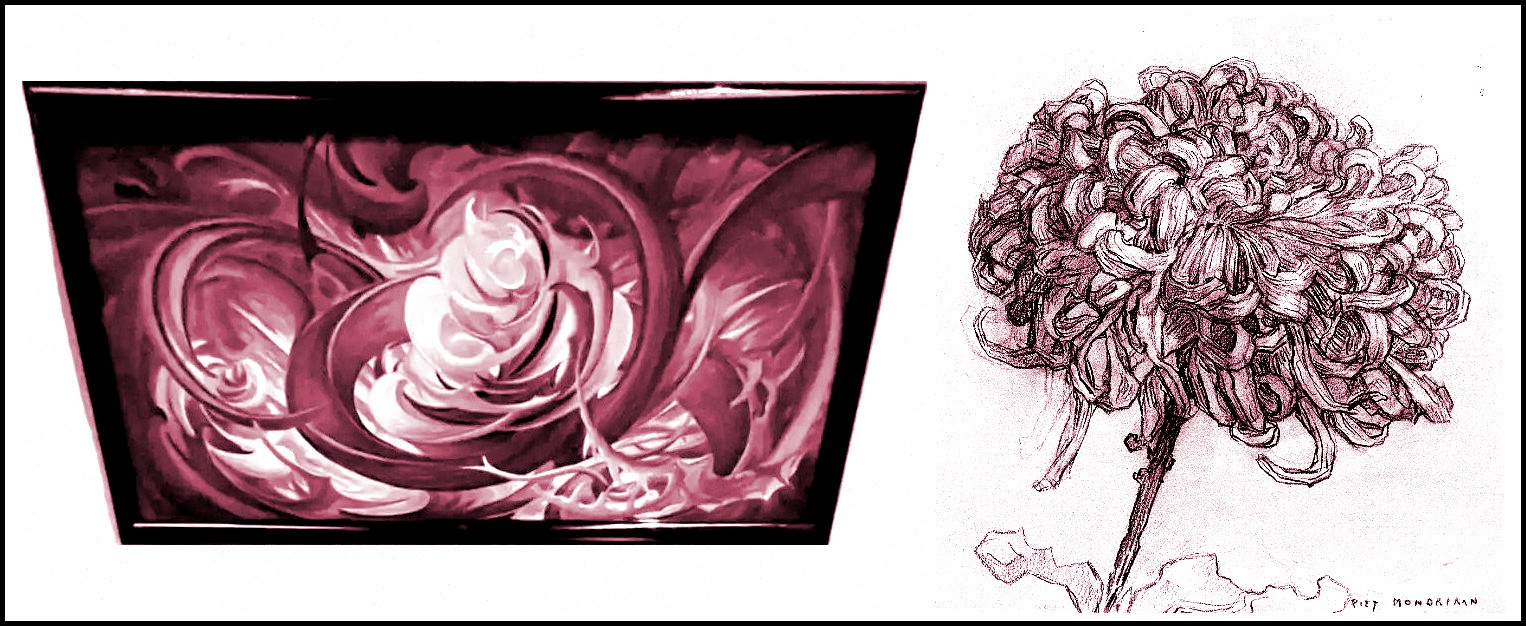

Through successive simplifications it took on a monumental quality, in spite of the small formats Spilliaert was so fond of using, lending itself to a kind of expressive distortion. Occasionally, as for example in the superimposed shapes of clouds reflected in water, this total simplification came very close to Abstraction. Spilliaert came close to what Henry van de Velde had so miraculously adumbrated around 1893: a quasi-abstract symbolic ornamentation, the fruit whose vibrant colors and curves have something Eastern about them, the plant form that an unusual composition erects into a cosmic symbol drawn from a philosophical notion of the fusion of being and everything…

Léon Spilliaert, Baigneuse, 1910 | Léon Spilliaert, Nocturne à la plage, 1905

…a notion we also find in the German Hermann Obrist, with his coral trees and smoke spirals, and in Piet Mondrian’s strange chrysanthemums. It was where Symbolism marked a pause, its echoes already launched.

Herman Obrist, Wall Decoration, 1899 | Piet Mondrian, Chrysanthemum, 1905

On the threshold of Surrealism we again find poets. Andre Breton, and with him Paul Éluard, Aragon, René Char, Benjamin Péret, Robert Desnos, Tristan Tzara, and many others revolutionized language in a way that had repercussions far beyond the frontiers of France. The Belgian contribution to Surrealist literature—less lyrical on the whole, often tinged with humour, and unobtrusive to the point of cultivating secrecy—is beginning to receive due recognition. As regards painting, two Belgian Surrealists, René Magritte (1898-1967) and Paul Delvaux (1897-1994), are so well known as virtually to have become household words. We say of some strikingly unusual sight that it is pure Magritte or just like Delvaux in the same way as we tend to refer to everything disconcerting in modern art as Picasso. Our eyes have become so conditioned that they turn out forgeries uninvited.

Paul Delvaux, Le miroir, 1936 | René Magritte, Les amants, 1928

CONTINUED IN PART 2 (SEE ‘RELATED POSTS’ BELOW)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2026 | All rights reserved

Comments