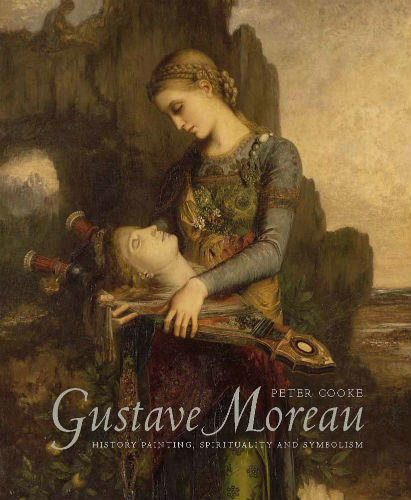

Gustave Moreau

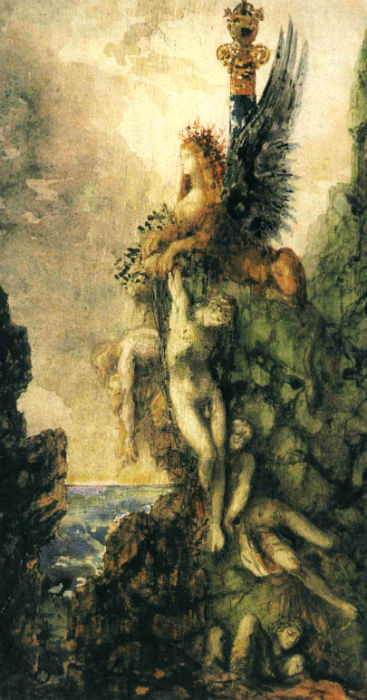

The Sphinx at Delphi

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 11: Pavlina

̶ Well, I don’t know how mad you were when you wrote Self-Portrait with Sphinx…

The fervour of her mouth, the lushness of her lips: Bocca basciata non perde ventura, anzi rinnuova come fa la luna.

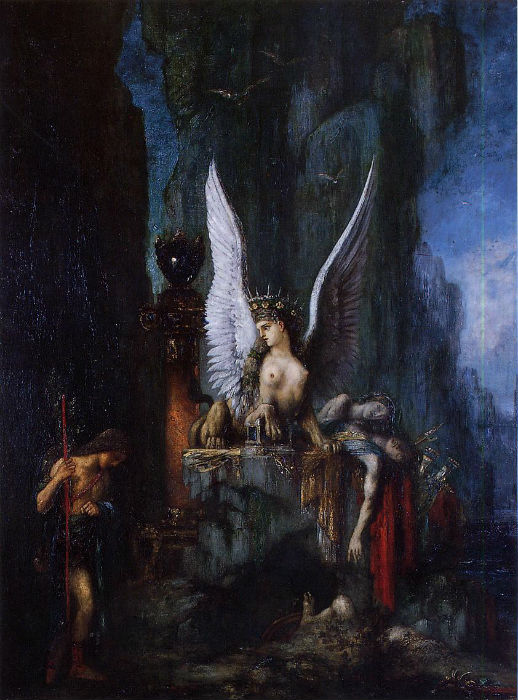

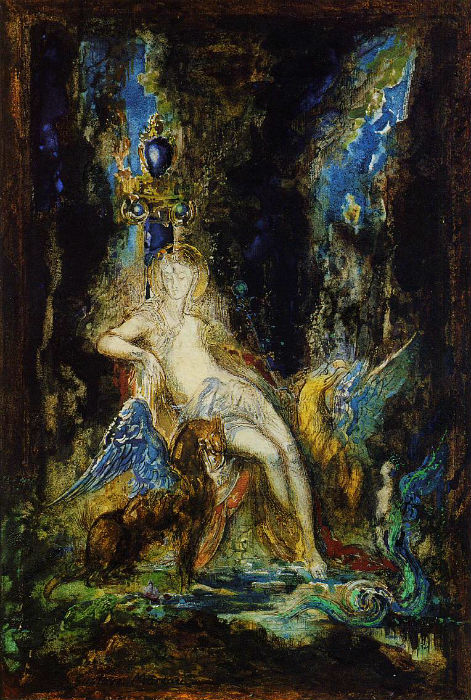

̶ …all I know is that I love it! Especially the Winged Fiend! Where does it come from, your view of the Sphinx?

̶ The Greeks. The Egyptian Sphinx is masculine. He’s a figure of the sun god, an emblem of royal power. The Greek Sphinx is far more interesting, simply because she’s feminine. In Hesiod’s Theogany she’s the child of a woman-serpent and her son, a dog with two heads.

̶ Charming!

̶ On ancient Greek vases she’s an incubus—lion’s body, woman’s head, eagle’s wings and serpent’s tail.

̶ Like on the cover of the album?

̶ Yes. And what do you see in it?

̶ In Moreau’s painting?

̶ Yes.

̶ Well, it’s very erotic. You feel the attraction.

The syncopation of her speech, the accent of her English: Is it only because we’ve just made love that I find her voice hovers between music and language?

̶ Yes. And that’s far more interesting than the fight between hero and monster.

̶ Because of the enigma?

̶ Yes. The enigma substitutes for the fight. And the fight, of course, is already a substitute for fucking.

̶ And the second enigma?

̶ ‘Who are the two sisters who bring each other into being?’

̶ The night and the day! Where does that come from?

̶ It’s not in Sophocles. It’s a later addition.

̶ You use it brilliantly, that sun and moon motif.

̶ Masculine-feminine. Everything derives from that.

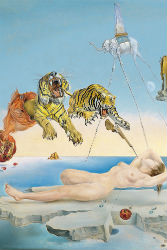

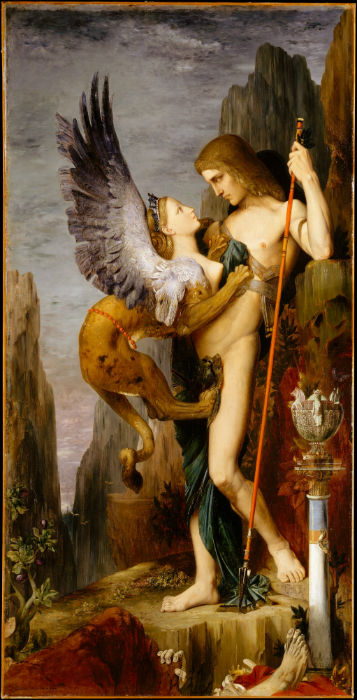

Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1864

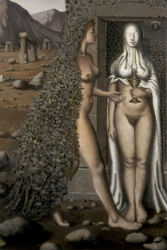

Gustave Moreau, The Apparition, 1876-77

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 8

And then I told you of La chambre secrète, Robbe-Grillet’s instantané that, at Film School, Fernando had asked Ariane to read. She did. And when he asked her if she’d play the woman in it, she said she would. A few weeks later there she was, naked on her back on velvet cushions, chains stretched from her ankles and wrists and blood dripping from her breast: You could have heard a pin drop in the screening room. Fernando had brilliantly captured the mystery in Moreau’s painting, the allure of Robbe-Grillet’s narration. Out of the play between curling smoke plumes and shadowy colonnades, Oriental tapestries and a brilliant blood stain, Ariane’s body distilled an intense eroticism: I knew that body, and I felt proud. But more than pride, I felt gratitude, for it was Ariane who’d shown me that sex in the bedroom need not be the shadow of sex in the head: It can be its enactment.

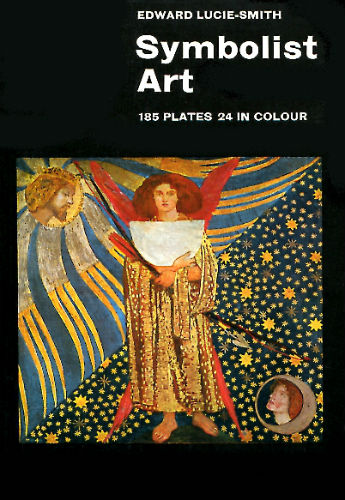

GUSTAVE MOREAU AND SYMBOLIST ART

From Edward Lucie-Smith, Symbolist Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1972) pp. 63-69

Gustave Moreau must be the central figure in any discussion of Symbolist art. In comparison with his contemporaries, Moreau emerges as an artist of a very special and distinctive kind. As Mario Praz points out in The Romantic Agony, ‘Moreau followed the example of Wagner’s music, composing his pictures in the style of symphonic poems, loading them with significant accessories in which the principal theme was echoed until the subject yielded the last drop of its symbolic sap.’ We may also apply to Moreau’s work a comment made by the American critic Victor Brombert on Flaubert’s Salammbô. He remarks on the ‘immobilization of life and animation of the inanimate’ to be found in that work: ‘As a result of this double tendency, the distinction between the organic and the inorganic vanishes, and being and becoming tend to merge.’

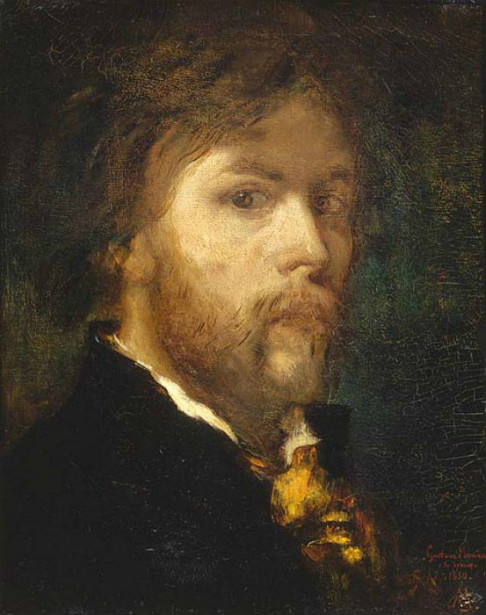

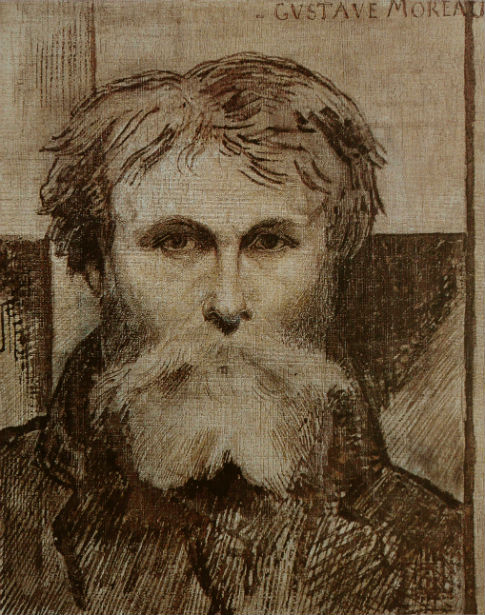

Gustave Moreau, Self-Portrait, 1850

Gustave Moreau, Self-Portrait, 1872

Moreau was an advocate of two linked principles: the Beauty of Inertia and the Necessity of Richness. He himself remarked: ‘Where a work of the imagination is concerned, one must only love, dream a little, and refuse to be satisfied—under pretext of simplicity—with the obvious.’ Like that of Burne-Jones, Moreau’s rise to fame was a gradual one. Despite the eminence of his admirers and the vocal nature of their enthusiasm, he has always remained something of a special taste.

His earliest work shows the very pronounced influence of Delacroix. In 1850 he met and was much influenced by Chassériau, whose taste for spangled, jewelled colour had a great influence on the formation of Moreau’s style. In 1856 he followed a long-established tradition among French artists by making a visit to Italy. He remained there for four years, and was especially attracted by the Primitive painters, archaic vases, early mosaics and Byzantine enamels. In 1864, he made his first real impact in the official Salon with his Oedipus and the Sphinx. Already his work was gaining a reputation for being eccentric and odd; one commentator said it was ‘like a pastiche of Mantegna created by a German student who relaxes from his painting by reading Schopenhauer’.

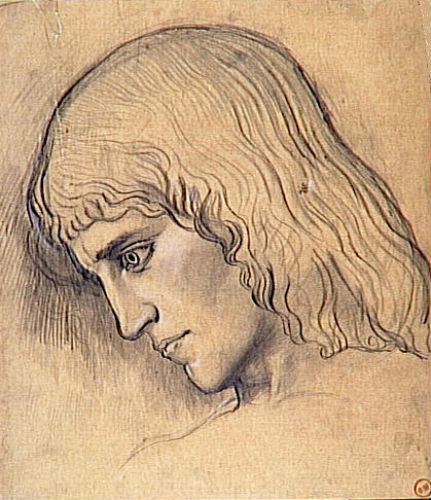

Gustave Moreau, Study for the Head of Oedipus, 1860-64

Gustave Moreau, Study for the Head of the Sphinx, 1860-64

He was savagely attacked by the critics for the works which he sent to the Salon of 1869, and thereafter he tended to withdraw more and more from the rat-race of official art. He was represented in the Salon of 1872, for example, and then not until that of 1876. After 1880, he no longer exhibited.

It was, however, at the Salon of 1880 that Moreau seems to have attracted the attention of J. K. Huysmans, then a moderately well-known novelist. In his account of the exhibition, Huysmans reserved the best of his enthusiasm for Moreau’s work. ‘Gustave Moreau’, he wrote, ‘is a unique, an extraordinary artist. After having been haunted by Mantegna, and by Leonardo whose princesses move through mysterious landscapes of black and blue, Moreau has been seized by an enthusiasm for the hieratic arts of India. From the two currents of Italian and Hindu art he has—spurred on by the feverish hues of Delacroix—brought forth an art peculiarly his own, an art personal and new, one whose disquieting flavour is at first disconcerting.’ This was, in fact, the first trumpet-blast of Symbolist enthusiasm, and Moreau’s special position in the Symbolist pantheon was to be confirmed when, four years later, Huysmans included descriptions of his work in his novel, A Rebours.

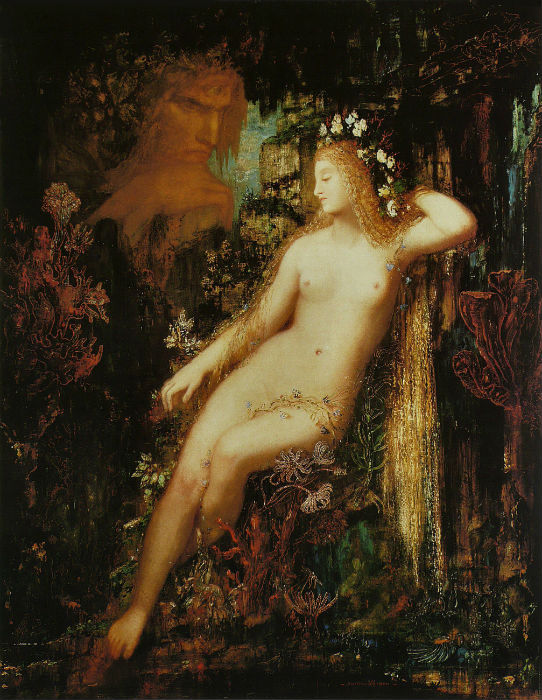

Gustave Moreau, Galatea, 1880

Gustave Moreau, The Voices, c.1880

In the 1880s and 1890s, after his withdrawal from the Salons, Moreau also achieved, paradoxically enough, a certain degree of official recognition. He had been given the Legion of Honour in 1875; in 1883 he was given the croix de l’officier; in 1889 he became a Member of the Institute, and in 1892 he was made a chef d’atelier, a professor with a studio of his own at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. This last appointment was something more than an empty honour. The reclusive Moreau turned out to be a teacher of genius, and among those who passed through his hands were Matisse and Rouault.

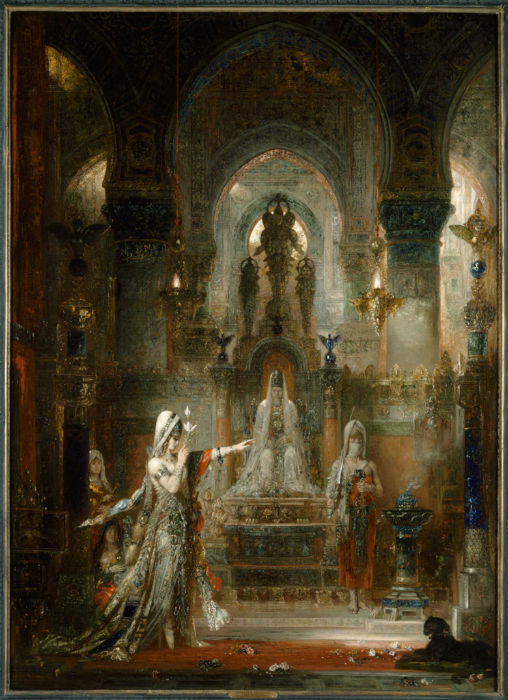

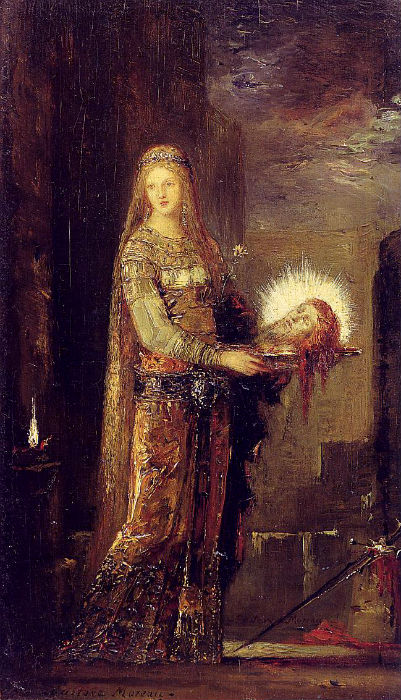

In writing about Moreau’s work in A Rebours, Huysmans naturally selected those aspects of it to which he felt most akin by temperament, and which best suited his own artistic purposes. The novel’s hero, des Esseintes (and by implication Huysmans himself), saw Moreau as the creator of ‘disquieting and sinister allegories made more to the point by the uneasy perceptions of an altogether modem neurosis’, as someone ‘forever sorrowful, haunted by the symbols of superhuman perversities and superhuman loves’. What fascinated des Esseintes/Huysmans was Moreau’s treatment of the Salome theme. A watercolour version of The Apparition, in which the severed head of the Baptist appears in a vision to the young Judaean princess, is the subject of pages of ecstatic description in A Rebours.

Gustave Moreau, The Apparition, 1876 (watercolour)

Gustave Moreau, Salome Dancing before Herod, 1876

Moreau cannot altogether have appreciated this kind of attention. He always much resented the idea that he was a literary painter. In his own mind he was quite the opposite. His own notes are enlightening on this score. ‘Oh noble poetry of living and impassioned silence!’ he wrote. ‘How admirable is that art which, under a material envelope, mirror of physical beauty, reflects also the movements of the soul, of the spirit, of the heart and the imagination, and responds to those divine necessities felt by humanity throughout the ages. It is the language of God! To this eloquence, whose character, nature and power have up to now resisted definition, I have given all my care, all my efforts: the evocation of thought through line, arabesque, and the means open to the plastic arts—that has been my aim!’

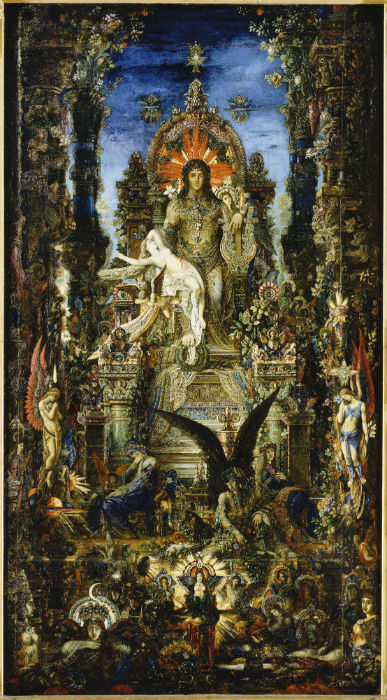

Each work was based upon an elaborate programme. Of his Jupiter and Semele, for example, Moreau noted: ‘It is an ascent towards superior spheres, a rising up of purified beings towards the Divine—terrestrial death and apotheosis in Immortality. The great Mystery completes itself, the whole of nature is impregnated with the ideal and the divine, everything is transformed.’

Gustave Moreau, Jupiter and Semele, 1889-95

Gustave Moreau, Jupiter and Semele, 1889-95 (detail)

How far did the artist succeed in fulfilling his own programme? That he is literary, scarcely anyone would now doubt. He has, in fact, been seen as the direct successor of the Flaubert who created not only Salammbô but La Tentation de saint Antoine. The swarming visionary detail of the latter work seems particularly close in spirit to Moreau’s paintings.

Detail, indeed, was a kind of trap to Moreau. The conception of his works gave him no difficulty, but the elaboration frequently did. He was a genuinely visionary artist in that his first idea seems to have presented itself to his mind’s eye complete in all its main outlines. It was when he tried to fill in these outlines, using material taken direct from nature, or even from other works of art, that he ran into trouble, as Théophile Gautier noted. Moreau’s earliest sketch for a composition often comes closer to the final version than any intermediate stage.

Gustave Moreau, Study for Jupiter and Semele, 1889-95

Gustave Moreau, Oedipus Wanderer, c.1888

But swarming detail was also a form of personal reticence. Odilon Redon, always shrewd in his comments on other artists, said of Moreau: ‘We know nothing of his inner life. It remains veiled by an art which is essentially worldly, and the beings evoked have laid aside instinctive sincerity. Will these beings step out of the picture in order to act? No.’

At the same time we must concede his power to fire men’s imaginations. Huysmans was inspired by him; the Sâr Péladan worshipped him despite the fact that Moreau was deeply suspicious of Rosicrucian hocus-pocus. Later, André Breton, pope of the Surrealist movement, was to haunt the Musée Gustave Moreau at a time when scarcely anybody else bothered to visit it. Looking at a work such as the Mystic Flower, with its tumescent forms, it is easy to understand Breton’s fascination with a painter who seems to have been very much the prisoner of his own unconscious.

Gustave Moreau, The Mystic Flower, c.1890

Gustave Moreau, Apollo and the Satyrs, c.1893-95

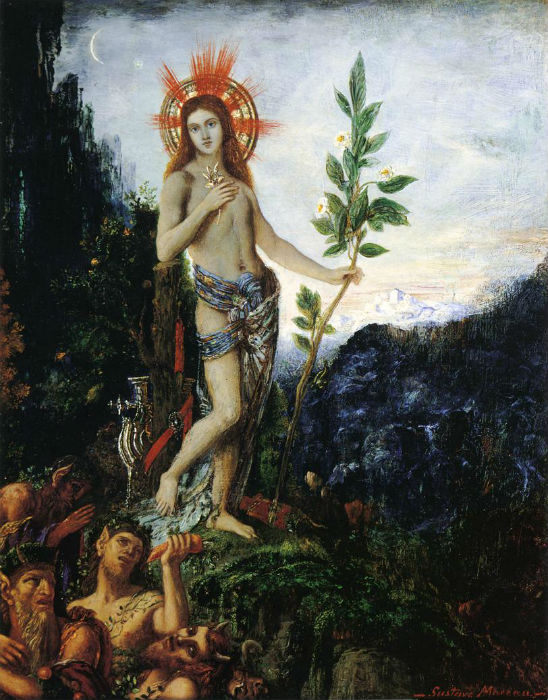

Particularly influential, so far as the artists of Moreau’s own time were concerned, was the languid androgynous type with which he peopled his compositions.

The Neoplatonic idea of the androgyne was to exercise a powerful fascination over late nineteenth-century critics and aestheticians, but it was Moreau who gave form to this idea in paint upon canvas.

Gustave Moreau, The Song of Songs, 1893

Gustave Moreau, Wayfaring Poet, 1868

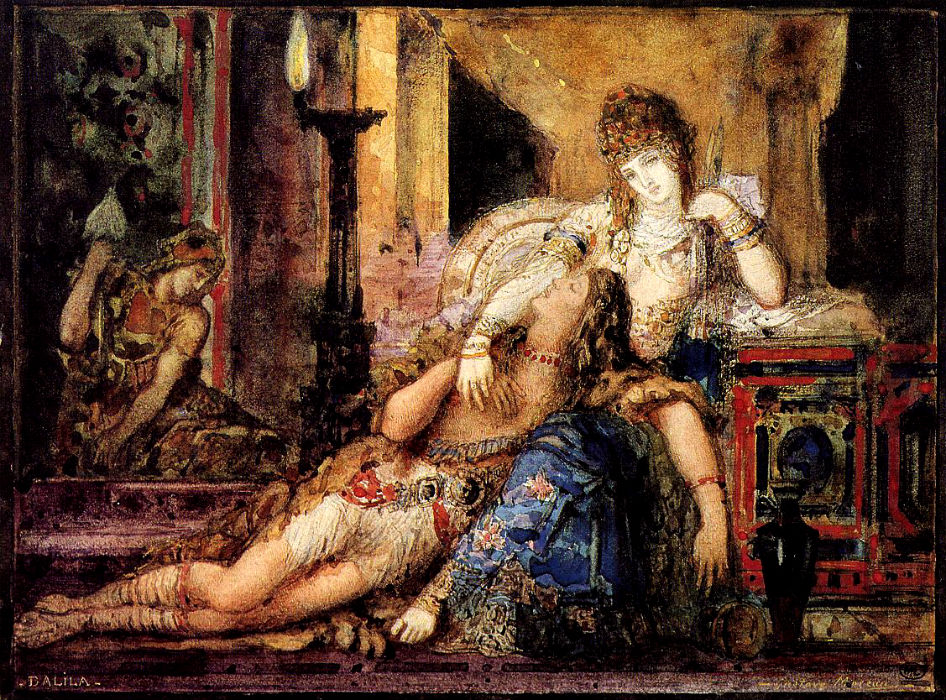

But there was more to it than this. In Moreau, it is above all the male who is languid and doomed to destruction. The poets who appear often in his compositions are frail, passive creatures.

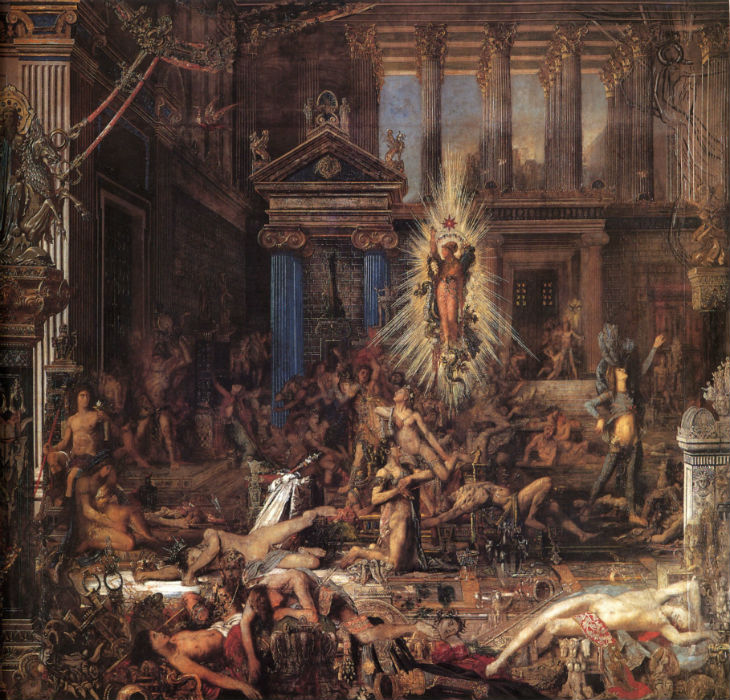

In The Suitors, we witness the massacre of beautiful effeminates—our sympathy goes out to them, rather than to Ulysses, whose house they have invaded.

Gustave Moreau, The Suitors, 1852/59/82

Gustave Moreau, Salome – Head of John the Baptist, c.1876

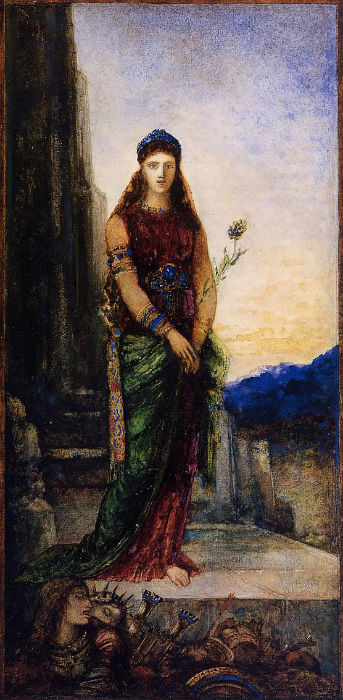

Moreau’s women, on the other hand, even if not active destroyers, like Salome, are beings whom it would be unwise to offend.

His fairies, for instance, are never the frail, fluttering creatures of early Romanticism, but personages who are both powerful and, for all their beauty, sinister. They seem, like much of his other imagery, to be part of a powerfully imaginative celebration of male fears of castration and impotence.

Gustave Moreau, Fairy and Griffon, c.1876

GUSTAVE MOREAU AND ROMANTIC AGONY

A selection of quotations from Mario Praz, The Romantic Agony (London: Oxford University Press, 1970), pp. 303-312

First published in Italian as La carne, la morte e il diavolo nella letteratura romantica in 1930

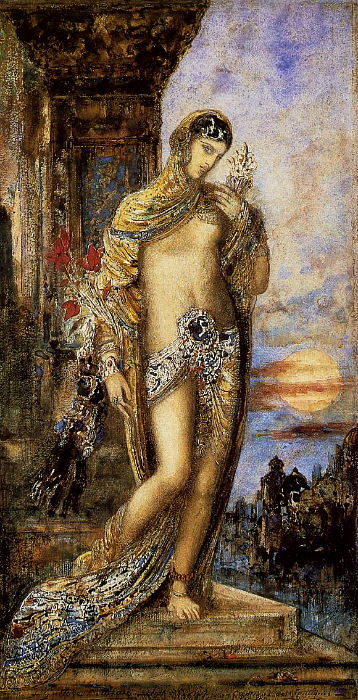

Gustave Moreau, Goddess on the Rocks, c.1890

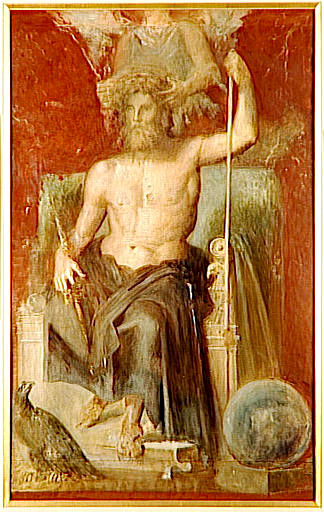

Eugène Delacroix, as a painter, was fiery and dramatic; Gustave Moreau strove to be cold and static. The former painted gestures, the latter attitudes.

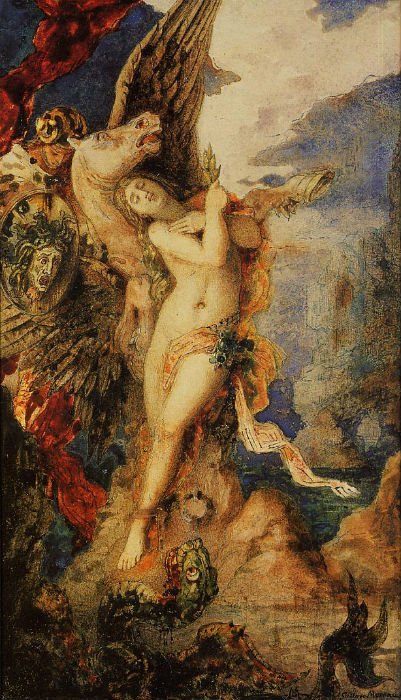

Moreau sought the theme of satanic beauty in primitive mythology and treated it in his pictures of the Sphinx series. This began with the painting which was the success of the 1864 Salon, in which the cruel beast with the face of an imperious woman plants her claws on the breast of the languid youth Oedipus [see second image from top of page]. It ended with the watercolour The Victorious Sphinx, in which the Sphinx reigns supreme over a promontory bristling with bleeding corpses.

Gustave Moreau, The Victorious Sphinx, 1886/88

Gustave Moreau, Helen on the Ramparts of Troy, 1885

He also treated the theme in Helen on the Ramparts of Troy, in which the femme fatale, glittering with jewels, stalks, as though entranced, among the dying.

Moreau’s figures are ambiguous; it is hardly possible to distinguish at first glance which of two lovers is the man, which the woman. All his characters are linked by subtle bonds of relationship, as in Swinburne’s Lesbia Brandon. Lovers look as though they were related, brothers as though they were lovers; men have the faces of virgins, virgins the faces of youths. The symbols of Good and Evil are entwined and equivocally confused. There is no contrast between different ages, sexes or types. The underlying meaning of Moreau’s paintings is incest; its most exalted figure is the Androgyne, its final word is sterility.

Gustave Moreau, Jason and Medea, 1865

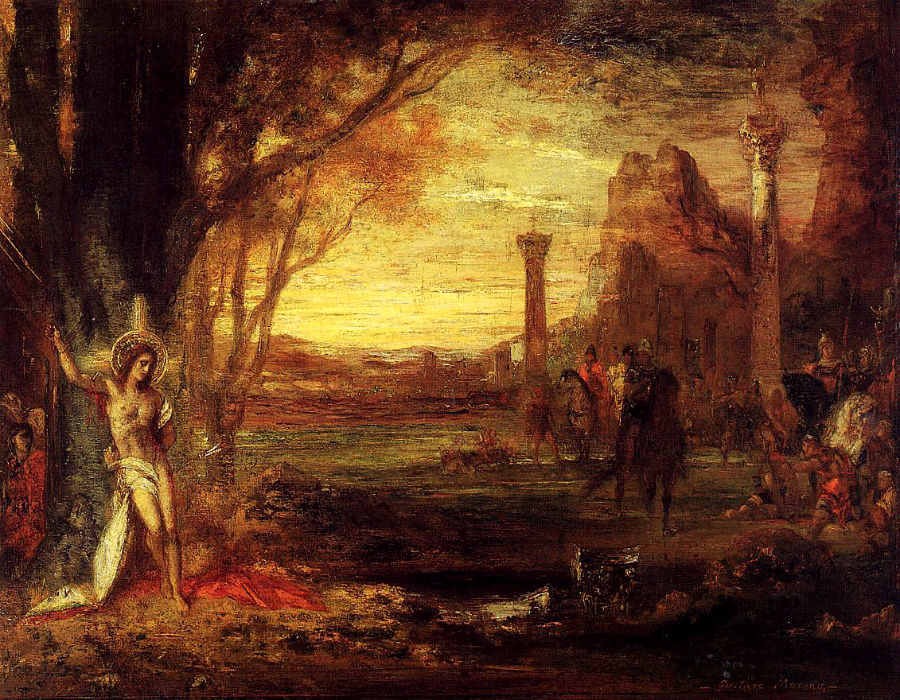

Gustave Moreau, Saint Sebastian and His Executioners, 1870

Salome, Helen, and the Sphinx are not the only incarnations of eternal feminine cruelty in the work of Moreau, whose morbid delight in subjects of sensual cruelty and suffering beauty is testified by the innumerable canvases which cover the walls of the museum he bequeathed to the State. The Athenians who were delivered to the Minotaur, slaves given as food to lampreys, the young man conquered by the fascination of Death, Diomede torn by horses, the Thracian maiden half-fainting as she gazes at the severed head of Orpheus, Saint Sebastian, the heap of beautiful bodies at the feet of the Hydra, the slaughter of the Suitors: Moreau justified his predilection for such subjects by an ethical-religious theory—he claimed that he was celebrating ‘the glorification of sacrifice and the apotheosis of redeemers’.

The favourite theme of Moreau is that of fatality, of evil and death incarnate in female beauty. It is in his painting, at the same time sexless and lascivious, that the spirit of the Decadent movement is most vividly expressed.

Gustave Moreau, Samson and Delila, 1882

Gustave Moreau, Perseus and Andromeda, 1867-69

Other pictures illustrate tremendous, monstrous loves—Pasiphae waiting for the bull; Semele, palpitating victim on the knee of Jupiter; Leda, Europa, subjects whose sensuality has become frozen in the visionary symbolism of languid and lascivious forms. The painter lingers in this world of his like a child who never tires of listening to terrible and mysterious stories; his figures have exactly that suggestion of the abstract and epicene which is characteristic of the childish imagination.

One has the impression in Moreau, as in Swinburne, of an ambiguous, troubled sexuality.

Gustave Moreau, Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra, 1875/76

For more on Symbolist art, see ROBERT SMITH, ROMANTIC SYMBOLIST: THE CURE AND SYMBOLIST ART in the MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG.