Painters of the Mind’s Eye

BELGIAN SYMBOLISTS AND SURREALISTS: AN OVERVIEW – PART 2

Francine-Claire Legrand

From Francine-Claire Legrand, Belgian Symbolists and Surrealists: Painters of the Mind’s Eye

(New York Cultural Center, Fairleigh Dickinson University & Houston Museum of Fine Arts, 1974) pp. 9-18. Translated from the French by J.A. Underwood.

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY. READ PART 1 FIRST.

FRANCINE-CLAIRE LEGRAND

Painters of the Mind’s Eye: Belgian Symbolists and Surrealists, 1974

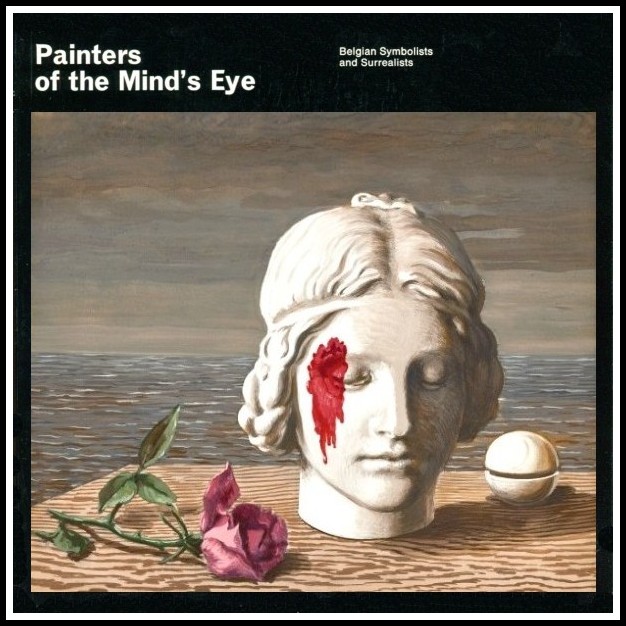

Various other movements came between Symbolism and Surrealism, the most important in terms of the way things developed being Dada, that bombshell that burst like an engine of destruction—or like a ripe fruit scattering its seed to the four winds. One or two demonstrations showed that Belgium had not been unaffected by the blast. Magritte was among the contributors to and founders of a number of publications that rang with the mighty laugh of the ‘cheerful terrorists’. The ferment of Dada persisted throughout E.L.T. Mesens’ life and work, in both his writing and his collages, and throughout the writing and nonchalance of Jean Scutenaire. Magritte, however, branched off. If we regard Dada and Surrealism as having been successive waves of the same tide, it was unquestionably the second that washed Magritte closer to his particular shore. Yet he still retained that bewildering irony that derives from the stubborn application of common sense to areas apparently utterly foreign to it, and which was probably what bound him to Dada in the first place. The Brussels Surrealist group was officially founded in 1926. Its central figures was the well-informed poet and theorist Paul Nouge, the others members Magritte, E.L.T. Mesens, Camille Goemans, Marcel Lecomte, Paul Hooreman, and Andre Souris, joined almost immediately by Jean Scutenaire and a few years later by Paul Colinet. As in France, sharp differences often split the group, leading to resignations and exclusions. In the same way differences of thought and language at times came between the Belgian Surrealists and their counterparts in France. But the spirit of inquiry that drove them all on never flagged.

Magritte, Tentative de l’impossible, 1928 | Hannah Hochs, Dada Dolls, 1916 | Man Ray, Portmanteau, 1920 | Magritte, L’Évidence éternelle, 1930 | Magritte, Les jours gigantesques, 1928

Even before the group was formed Rene Magritte had begun a series of pictorial experiments whose richness has yet to be exhausted. As regards the device of removing objects from their context, by photographic or other means, Magritte’s thought, as illustrated by his paintings, continues to provoke artists to further thought. In 1925 Max Ernst began his frottages, questioning the very substance of things and introducing automatism and the exploitation of chance—the mainspring of French Surrealism—into the act of painting itself. About the same time Magritte started using painting to examine the nature of visible reality by means that were diametrically opposed to Ernst’s. Depicting commonplace objects and scenes in a precise and neutral fashion, he arranged them in such a way that they upset our habits of thought and that this upheaval releases, like an instantaneous illumination, the idea—midway between sense and feeling—that there is something hidden behind appearances.

Magritte, Au seuil de la liberté, 1937 | Max Ernst, Untitled (Loplop Presents), 1932 | Magritte, Reproduction interdite, 1937

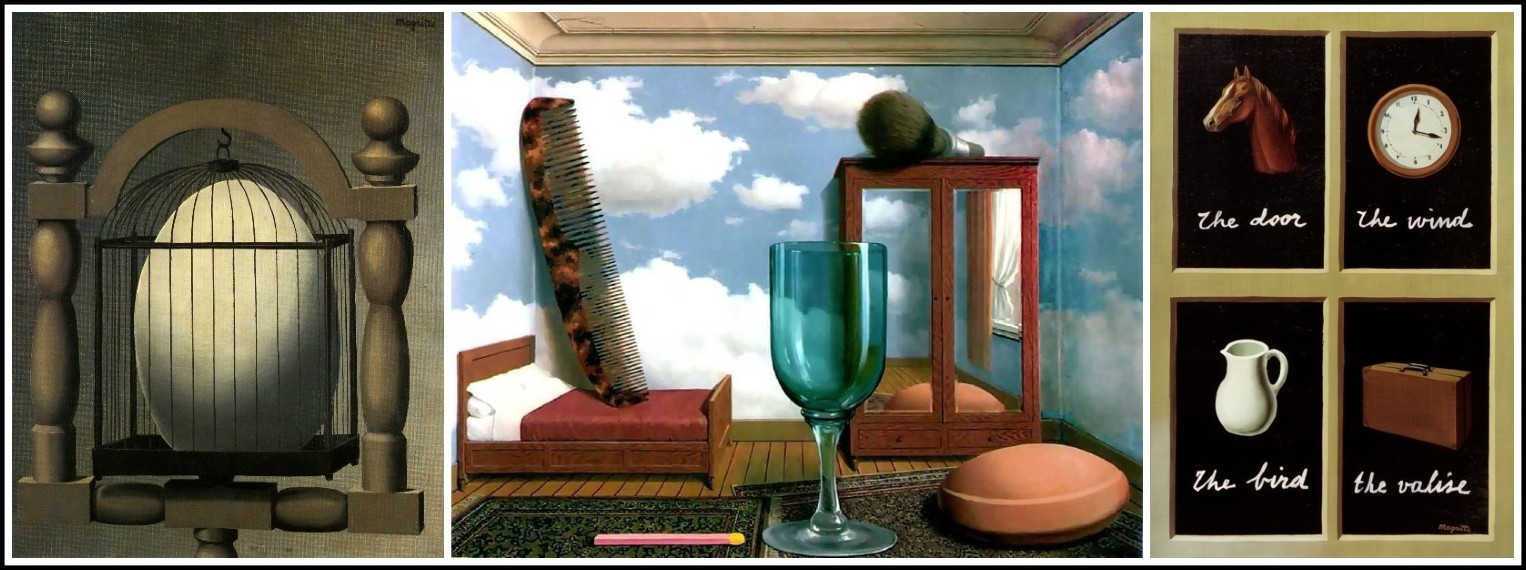

Where Breton’s disciples limited the artist’s responsibility, Magritte shouldered his without flinching. His approach was based on a lucid and methodical exploitation of the subversive potential of the pictorial image, studiously avoiding all vagueness, woolliness, and arbitrariness and using instead a universal language of primary and generally communicable signs such as a door, an egg, or a woman, in other words all the things we so swiftly ‘recognize’ yet of which we lack any real cognition. André Souris was to compare Scutenaire’s approach with Magritte’s, pointing out that both paint the commonplace not in order to lead off into the fantastic or into dream or into the subconscious but in an attempt to give a new and poetic attribution to ordinary, existing objects. Incidentally, although Magritte was the only painter to approach his art in this way, the Brussels Surrealists in general had their reservations about the kind of psychical automatism to which Breton so wholeheartedly subscribed. They were wary both of esthetic fraud and equally of the slippery slope leading to highly questionable habits of thought. The Surrealist challenge, the summons to take a fresh look at the world, was for them the outcome of a particular strategy much more than a general upheaval of mind and perception.

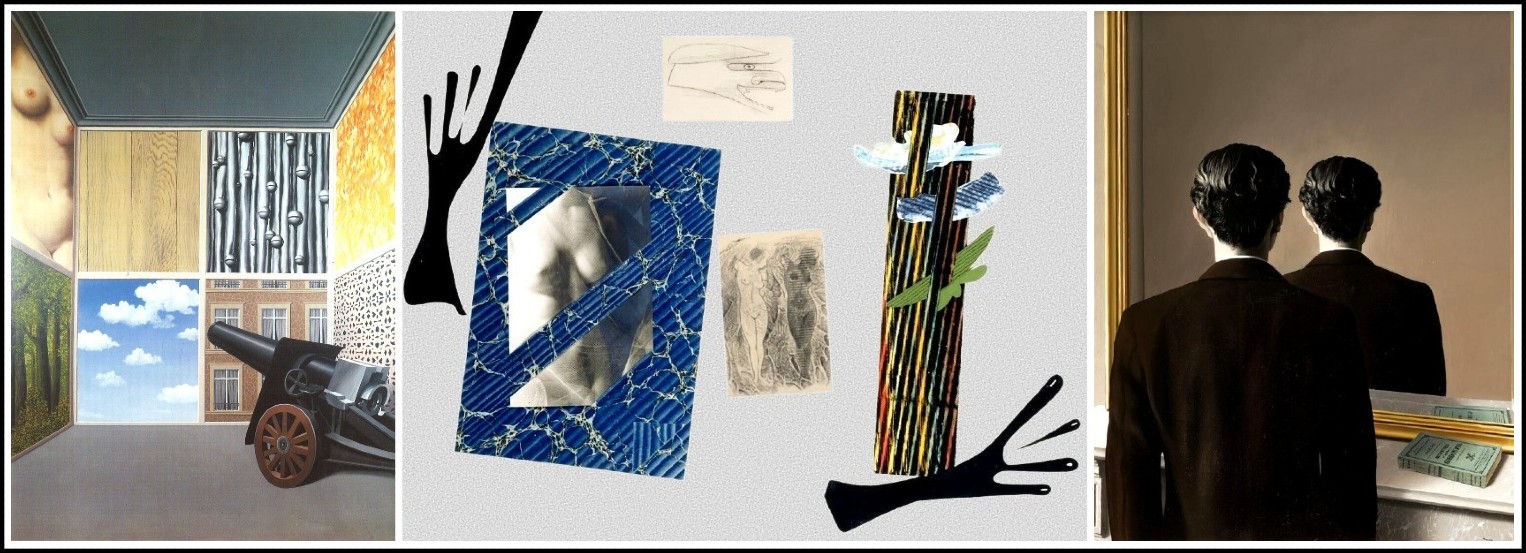

Max Ernst, Épiphanie, 1940 | Magritte, La clairvoyance, 1936

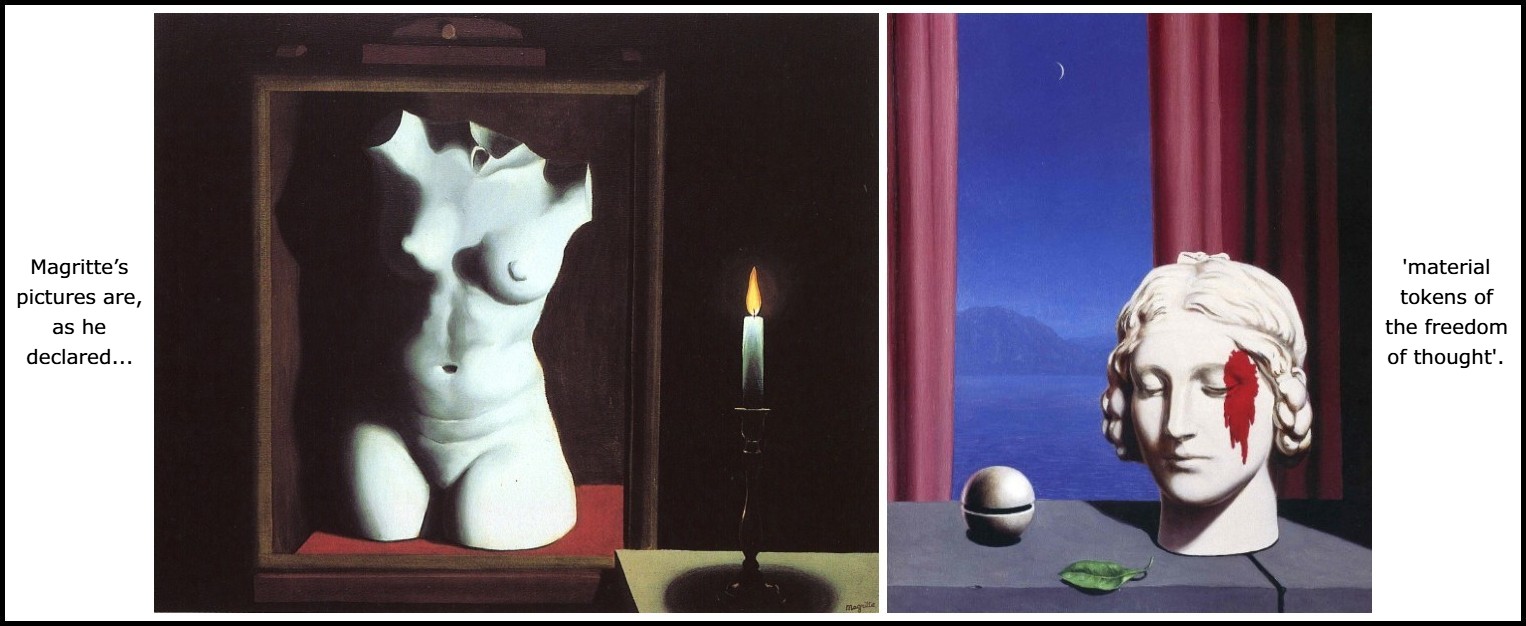

Magritte fiercely and persistently rejected any equation of the objects he painted with symbols. And he was, of course, absolutely right in so far as his pictures are, as he declared, ‘material tokens of the freedom of thought’, while symbols are defined in relation to a body of conventional references. For the Symbolists themselves, however, and particularly for the Belgian painters of the Symbolist school, the meaning of a symbol lay within a circle of feelings and perceptions, a circle that lay open to the mysterious. ‘It is the perfect exploitation of mystery that makes the symbol,’ wrote Mallarmé. Magritte was sufficiently alive to what Mallarmé was doing to write, ‘the passing of Mallarmé marks the end of a humanity in which the veil of authenticity was able to give poetry the aspect of an answer’. Nevertheless he quite deliberately pursued his own investigations in the opposite direction, bringing them to bear on the object as such, i.e. as representing nothing but itself.

MAGRITTE

La lumière des coïncidences, 1933 | La mémoire, 1948

He directed his attention at the relationships between objects, at their actual properties, and at the dialogue they maintain with their surroundings, a dialogue full of unexpected sounds and effects. It was not a case of handling symbols or even concepts—that was something he deliberately avoided. Magritte used pictorial images as a philosopher uses ideas; he arranged them, not gratuitously for the pleasure or the fun of it, but in order to embody the coherent development of his essentially poetic conception of the world. For him poetry was the description of thought as inspired by mystery. The object of poetry was the kind of apprehension of the secrets of the world that would offer a purchase on its elements. Magic was thus admissible. He went about his art in a highly rigorous manner, experimenting systematically with a number of procedures in turn, bringing them to perfection like a research chemist modifying the titration of a product in order to increase its efficacy. Let us have a look at some of those procedures.

MAGRITTE

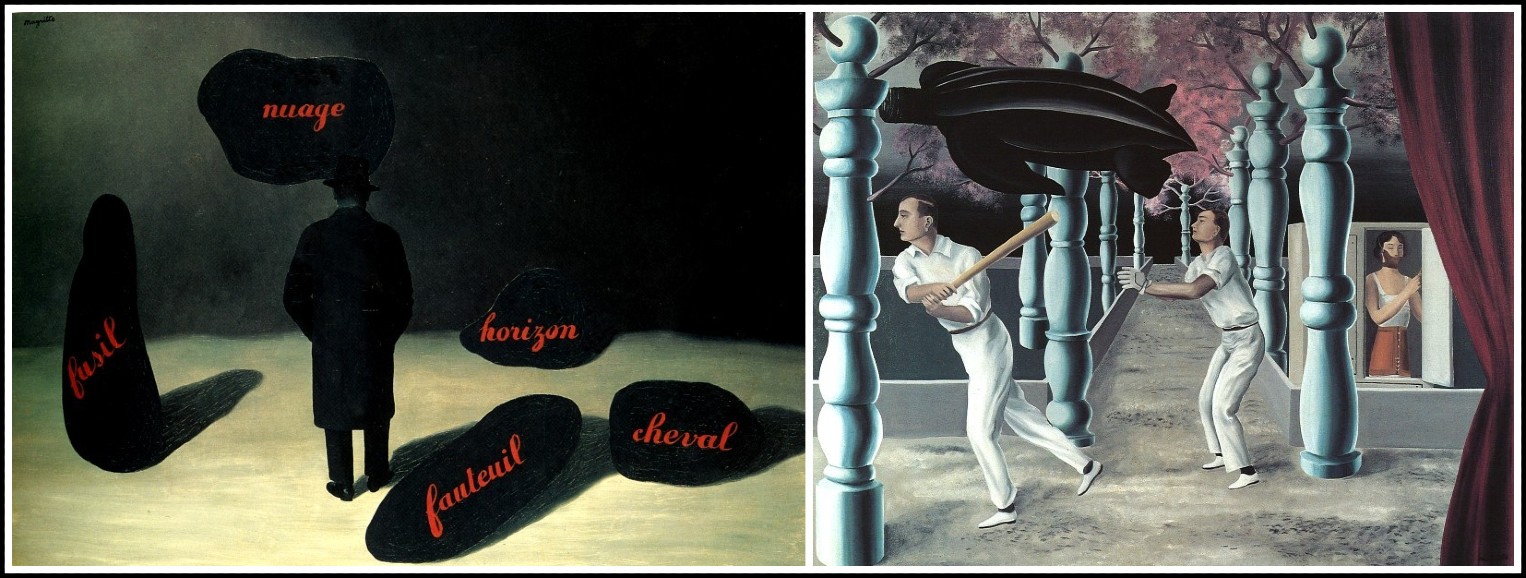

L’Apparition, 1928 | Le joueur secret, 1927

Often Magritte appears to be transferring to canvas the kind of confrontation that Lautréamont had in mind when he talked about the fortuitous encounter of a sewing-machine and an umbrella on a dissecting-table. Except that there is nothing fortuitous about such encounters in Magritte. They are quite deliberate, though they sprang from an inner spark. At one point he conceived the idea of representing objects in a kind of chrysaloid form. A naked woman’s flesh, for example, becomes monstrously metamorphosed into grainy wood or into a man violating her; a pair of boots standing by a wooden fence end in real toes; nipples, navel, and crotch form a woman’s face.

MAGRITTE

La découverte, 1927 | Le viol, 1945 | Le modèle rouge, 1935

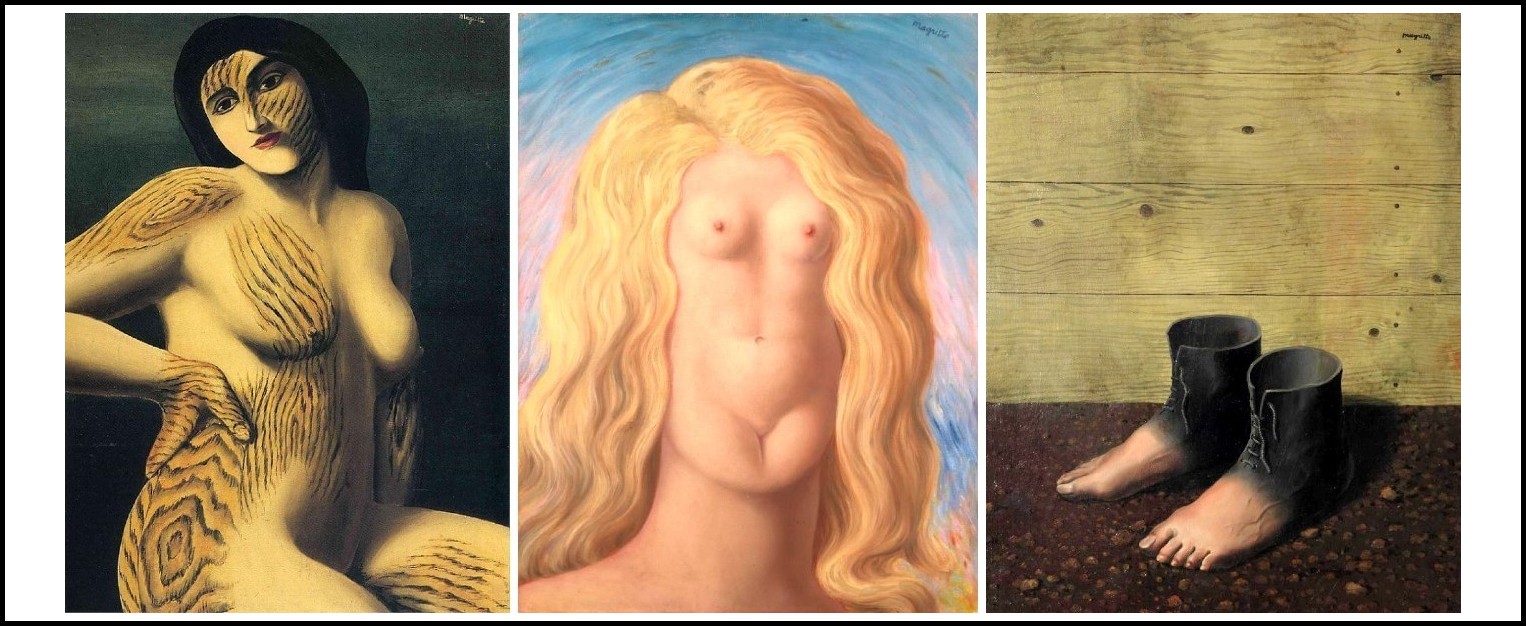

At other times Magritte experimented with modifications of the relative proportions of things, painting a feather and the Leaning Tower of Pisa the same size, or he turned appearances inside-out, putting a streetlamp in the middle of a room.

MAGRITTE

Souvenir de voyage, 1955 | Noctambule (Le réverbère), 1928

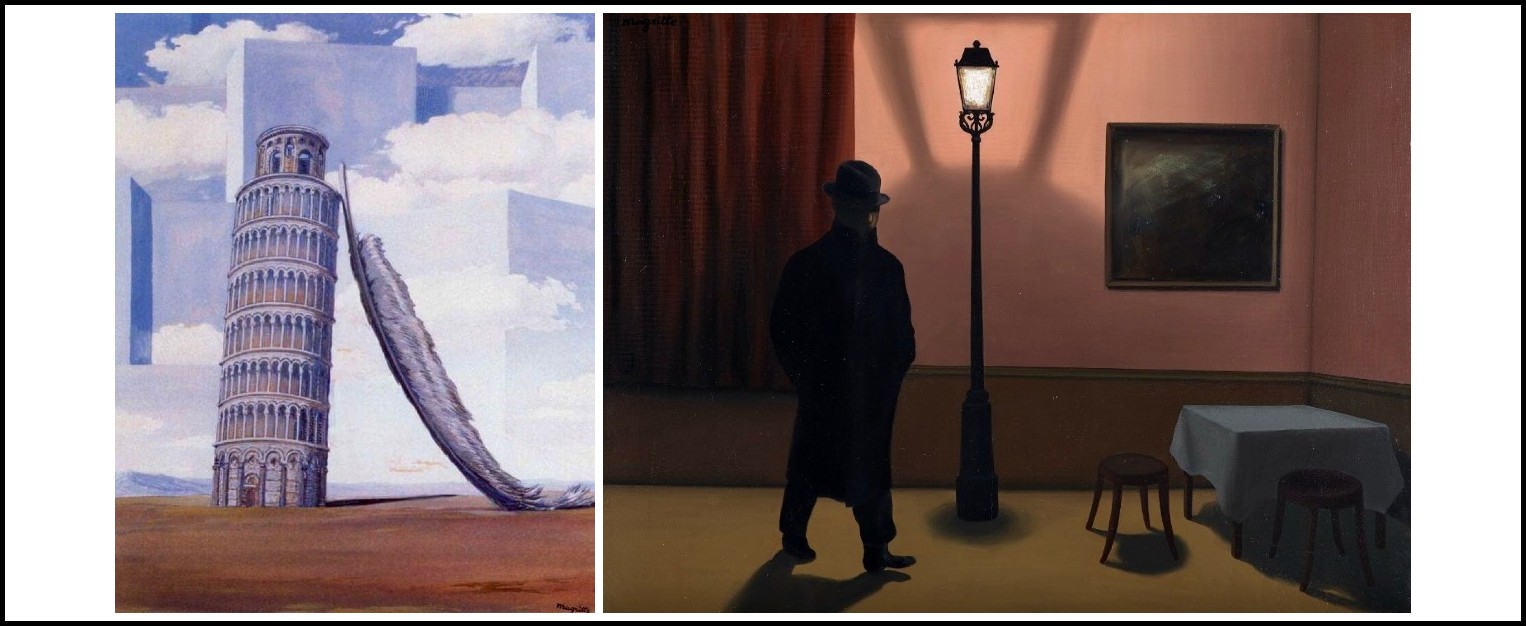

He spent a long time challenging the equivalence of the names we give things, renaming objects by putting other names to pictures of them in order, as he said, to ‘set up new relationships between words and object’, questioning both the status of objects and the function of words in order to draw attention to the arbitrary nature of our powers and the fragility of our convictions. Experience showed him that the shock set up between two objects might also stem from their relationship: ‘The conviction grew upon me in the course of my researches that I invariably knew in advance the element to be discovered, the special thing attached obscurely to the object, but that my knowledge of it was as it were buried beneath my thoughts.’ All these efforts were directed as much at the painted image as at its model, or rather at the fallacious identification of the two through the looking-glass of resemblance. For Magritte explored the negative relationships between real object and painted illusion, between painted illusion, object, and the word arbitrarily used to designate it. Arising out of this it becomes clear how Magritte’s objects are bewildering objects that assume totemic significance. Without being symbols, they nevertheless work symbolically. Magritte’s images appeal to the same thought mechanisms as do symbolic images but aim at a salutary effect by engaging those mechanisms in reverse. So when Magritte wrote that ‘a symbol is not identical with what is symbolized,’ was he not situating his work in a kind of hiatus, a hiatus within which the relative reality furnished by the senses is not identical with absolute reality? A work that both bears witness to a world barely glimpsed and provides the keys to that world. All his pictures are prophetic. Equally they are revelations of the past.

MAGRITTE

Les affinités électives, 1932 | Les valeurs personnelles, 1952 | La clef des songes, 1935

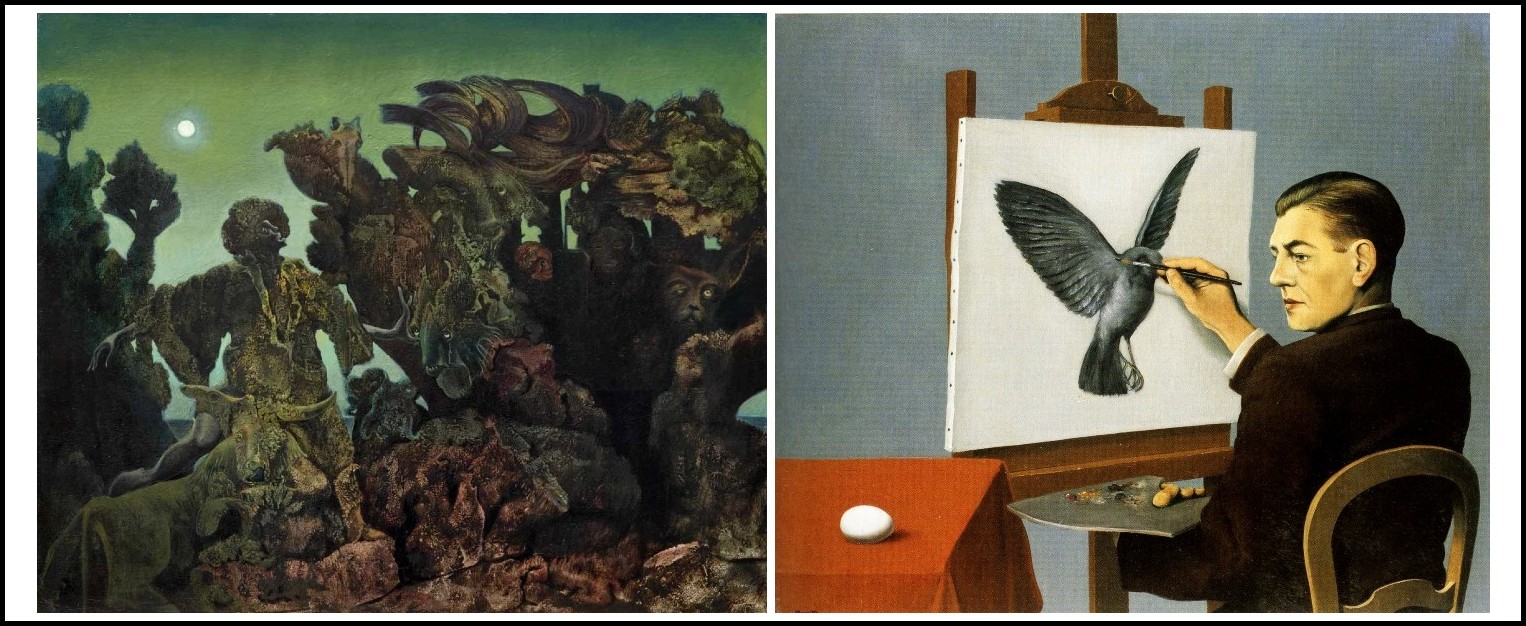

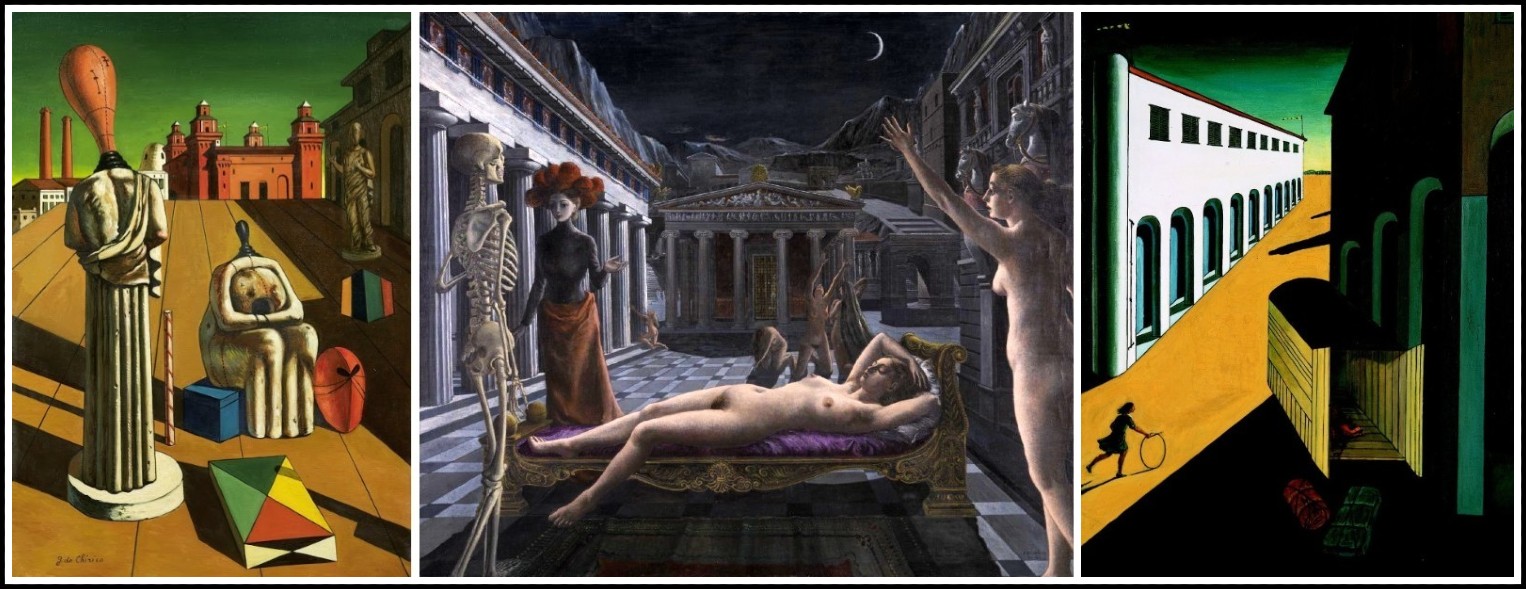

Paul Delvaux has made it quite clear how he stands toward Symbolism: ‘I don’t like Symbolism. Not at all. It runs completely counter to my deepest feelings. But when you tell me ‘Khnopff’ and I go off and see Khnopff—well, it’s very beautiful, really, despite everything. One cannot but acknowledge the fact. One doesn’t like what it’s called, but in practice it’s splendid.’ A horror of the label combined with a lively emotional response to the work—more or less his attitude as regards Surrealism, too, except that the Surrealist label has proved stronger than he and he has ‘acknowledged’ it in order to protect his enchanted odyssey. We must judge from externals, then. Not only has Delvaux never belonged to a Surrealist group, he has never accepted the dogmas of the movement. He has formally denied any kind of revolutionary motivation, for example, and when he has provoked a scandal it has been unwillingly. The fact remains that Delvaux discovered his true self through Chirico, whose early work represents a similar convergence. In Chirico’s case clearly prescience was at work, for his greatest years were before Surrealism’s ‘campaign for the total emancipation of man’ was really under way. Chirico in fact drank at the well of Symbolism as Delvaux was later to bathe in the river of Surrealism in order to inure himself to fear of the wonderful.

Giorgio de Chirico, The Disquieting Muses, 1960 | Paul Delvaux, Sleeping Venus, 1944 | Giorgio de Chirico, Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (1948/1965)

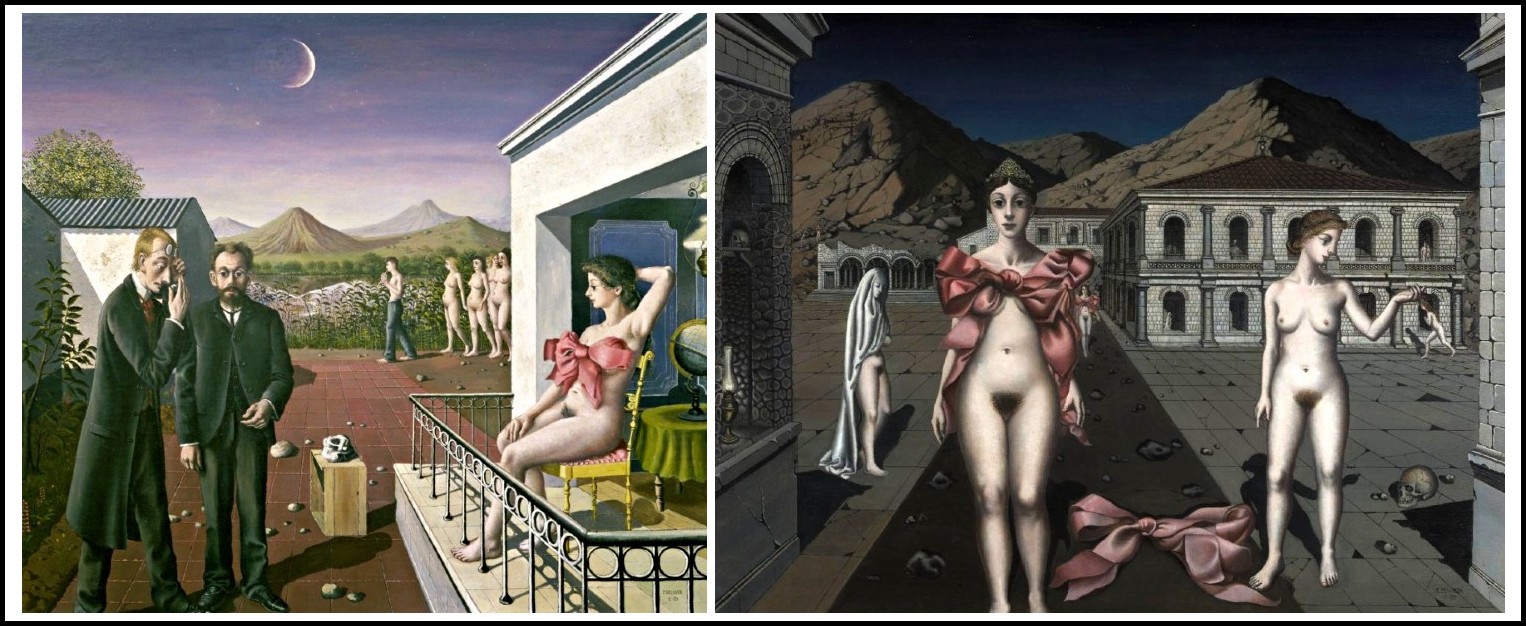

There came a time when the Surrealists hailed Delvaux as one of themselves. Éluard first, for the needle of his exceptional sensitivity was tuned to a farther pole than the early explorations of his companions disclosed. And then Breton, whose words unfortunately stray so far from the straight and narrow in their facile picturesqueness that they perhaps do not even convey the artist’s true stature: ‘Delvaux has turned the world into the empire of one always identical woman who rules the sprawling suburbs of the heart where the ancient mills of Flanders revolve a pearly necklace through a luminosity of ore’. Some purists distinguish a Surrealist period in Delvaux’ work from 1934 to 1942 or 1945, rejecting the “Sirens’ song” that continues to echo in his work until long after those dates. There seems no reason why the trains and skeletons that occur more frequently after 1942 should not people the world of dream as well as do the arrested gestures of the tall, nude goddesses whose Pink Bows fade as they fall. And it was in terms of the capturing of images seen in dream that Breton made his position with regard to painting more flexible and won over certain painters.

PAUL DELVAUX

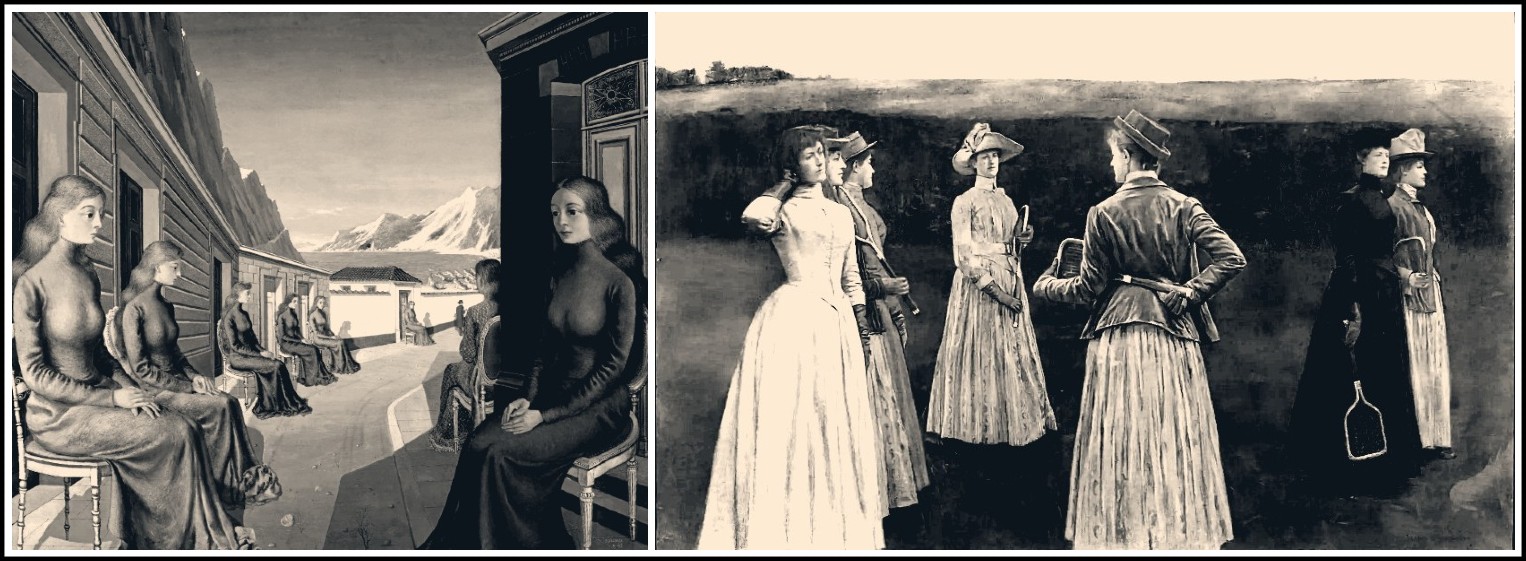

Phases of the Moon, 1939 | The Pink Bows, 1937

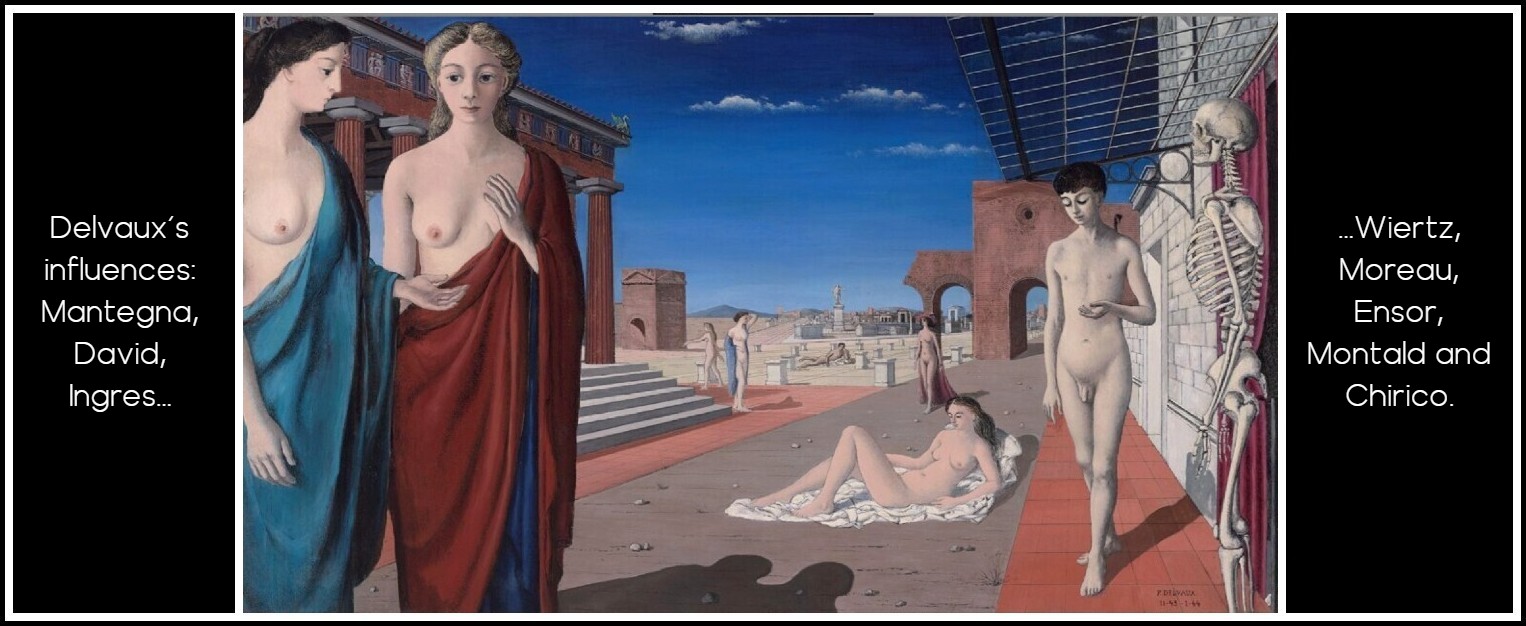

Here too Delvaux has made himself quite clear: he has never painted a picture that was a dream. What he paints is always a second reality. So Claude Spaak is closer to the truth about Delvaux when he writes, ‘Delvaux is a Surrealist. He has been one ever since 1936 if we regard painting not as a means of interpreting the external world but as an act of liberation more unconscious than directed on the part of a person looking inside himself, studying his enigma, and seeking to resolve it.’ In which case Khnopff too was a Surrealist. Where we can agree is in saying that Delvaux is a visionary. His visions are prompted by various reminiscences and influences: a classical training, Mantegna, David, Ingres, Wiertz, Moreau, Ensor, Montald—his master, an ‘escapee’ from Symbolism—and finally Chirico. They are illuminated by contemporary experience. They are elicited by the stimuli that have inspired all visionaries, be they poets or painters, since the Romantic age. It is through Romanticism that one may draw parallels with the principal subjects treated by the Symbolists, so that in spite of his denials it is tempting to place Delvaux in the wake of Symbolism. Among those subjects are love, death, night, and solitude and silence.

Paul Delvaux, La ville rouge, 1944

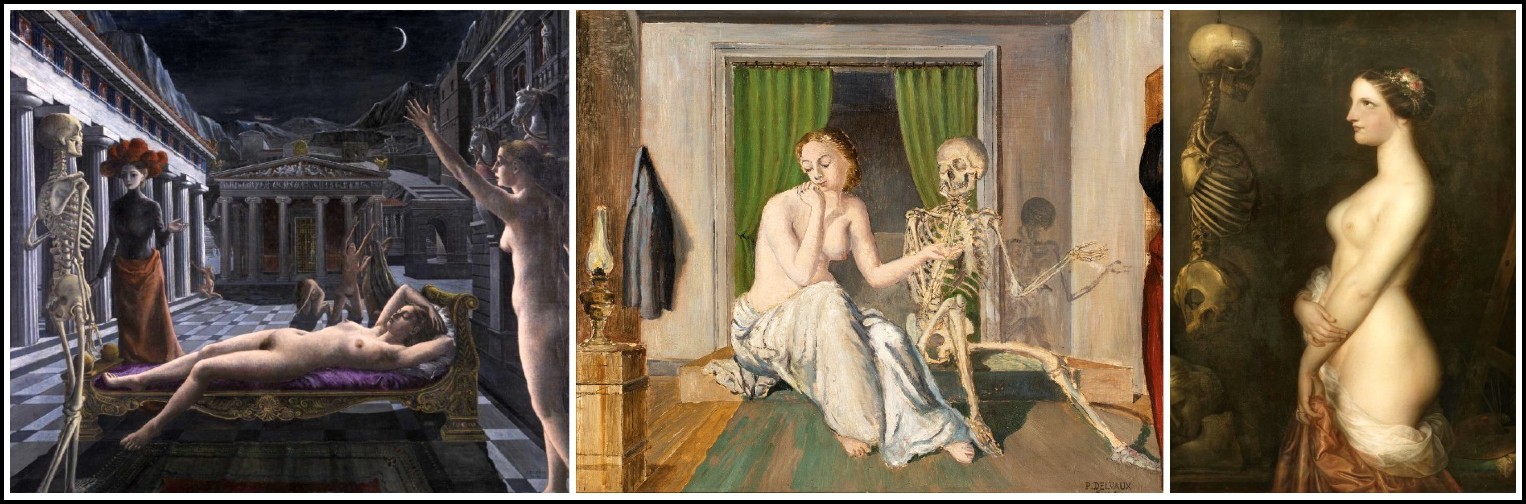

LOVE. Love, never fulfilled; the lack of and search for it; love as the vehicle of initiation, very like the definition of eroticism proposed by Bataille and seconded by Breton: ‘a direct aspect of inner experience in opposition to animal sexuality’. Love and its nostalgic incarnation multiplied indefinitely by the depth of memory in Village of the Sirens, as Khnopff multiplied it in his Memories, repeating seven times the features and silhouette of his sister, his other self, his double on the point of leaving him. Notice that there is nothing perverse about Delvaux’ world, as there is about those of Bellmer and Balthus, for example, with whom he has often been compared. When in the later work the bodies of his women become more youthful and almost transparent, a serenity born of distance accepted lightens the motionless dance of their feet.

Paul Delvaux, Village of the Sirens, 1942 | Fernand Khnopff, Memories, 1889

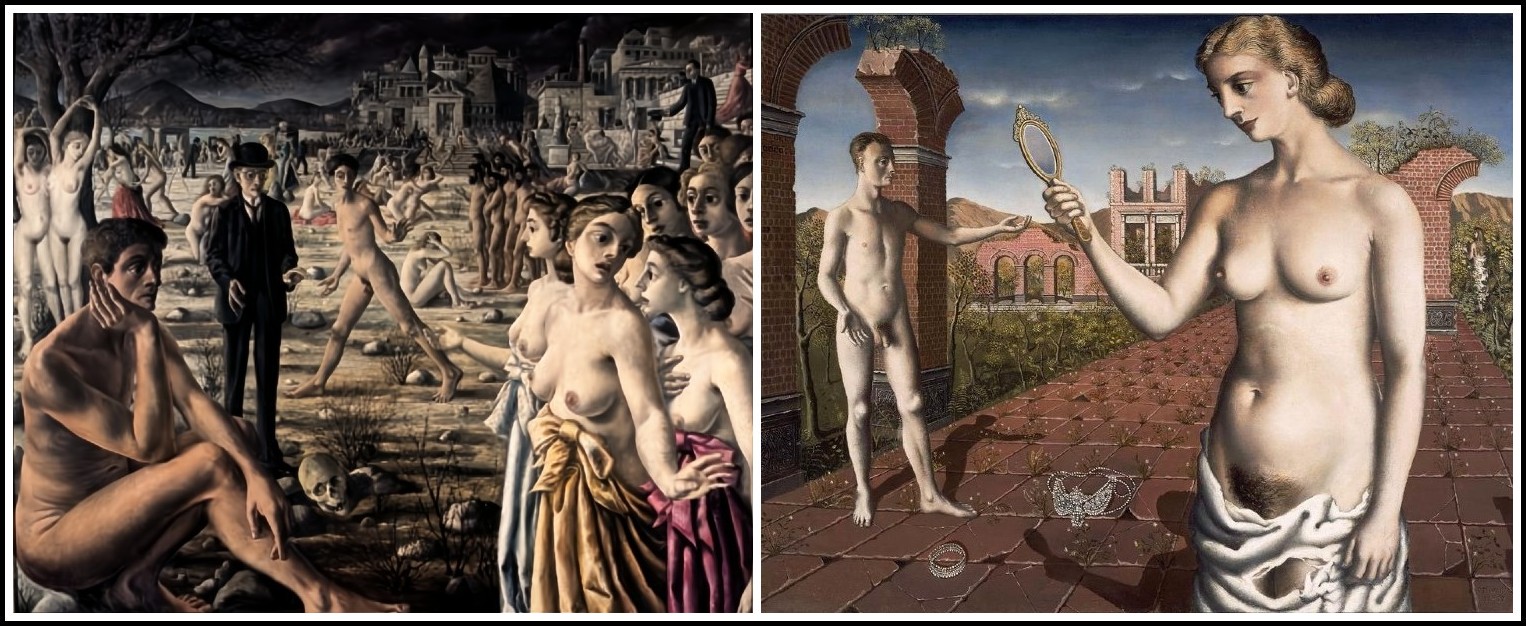

DEATH. Like that of the door, the skeleton theme arose out of the painter’s habits of life and work. The story of the visit to the Spitzner Museum, with its disturbing juxtaposition of a sleeping Venus and a skeleton amid a fairground atmosphere of light-hearted revelry, is the story of a revelation. The first version of the painting no longer exists; we have only the sketches for it. The second version has, besides the remembered apparition, a knot of absent-minded spectators, friends of the painter—much as Magritte, in another famous painting, placed objects on a level with his friends’ eyes to give them a look of clairvoyance. During the war years the skeleton came into its own as a result of studies Delvaux made at the Natural History Museum. Here the skeleton no longer represents death but the framework of the human body; it is not a symbol but a creature as much alive as any other. Delvaux placed it in his studio, in a book-lined interior. He cast it in the role of a seducer, holding the hand of a nude woman with downcast eyes, mimicking her gesture. The latter image, while not unlike Wiertz’ Lovely Rosine, is at the same time utterly different: instead of Wiertz’ disturbing encounter we have an amorous intrigue between the belle and her double. Ultimately skeletons were to become the protagonists of the Passion. Ensor had the same idea, but what was important for him was the figure of Christ and his flesh tormented by the hosts of hell. Delvaux, in associating skeletons with Christ, sought to coerce them into a more intense existence.

Paul Delvaux, Sleeping Venus, 1944 | Paul Delvaux, The Conversation, 1944 | Antoine Wiertz, Lovely Rosine, 1847

NIGHT. Night is as powerfully present in Delvaux as it in Magritte, and as invasive as in Spilliaert and Degouve de Nuncques. Lighted windows, lamps, candles, and streetlights make it more mysterious by peopling it with shadows whose expectant gestures echo those of the creatures of flesh and blood. Night invites myth. It leads to legend, which is the night of time. Sleeping Venuses, Sleeping Beauties such as Burne-Jones loved too, seeing a second meaning in them, namely the ‘tangle of right and wrong’ of The Briar Rose. Delvaux’ rose, Delville’s rose, the Pre-Raphaelites’ rose—three flowers of miracle. It is in a legendary past, the past of his own childhood, that Delvaux sets his reveries. Like his guides, the masters of the Quattrocento, Delvaux is an archeologist. Details consign the picture to the mythical climate of memory from which sublimation derives its strangeness. Surely the same applies to the Romantics and their later brethren, the English Pre-Raphaelites, as well as to certain Belgian and French Symbolists who invested Psyche and Perseus, Medusa and the Sphinx with their fears. According to P.A. de Bock, Delvaux’s art ‘is and remains his refuge, filling the place of the maternal lap.’ Be that as it may, the painter’s childhood is constantly cropping up, becoming crystallized in borrowings from an old illustrated edition of Jules Verne, and in the choice of his absent-minded hero, Professor Otto Lindenbrock, a key figure in one of the most beautiful of the nocturnes, The Phases of the Moon, III (1942).

PAUL DELVAUX

The Break of Day, 1937 | Woman in the Mirror, 1936

SOLITUDE AND SILENCE. This theme, which arises out of the preceding ones, is present even in the pictures that are full of figures—The Anxious City, for example—for ‘solitude and promiscuity are the two most identical opposites in the world.’ It was also one of the Belgian Symbolists’ favorite subjects. There is hardly a picture of theirs in which it is not alluded to—in the form of an arrested gesture, for example in Mellery, or of allegory and suggestion, as in Khnopff and Delville, or the melancholy atmosphere that reigns in Degouve de Nuncques and Spilliaert.

PAUL DELVAUX

La ville inquiète, 1941 | Proposition diurne (La femme au miroir), 1937

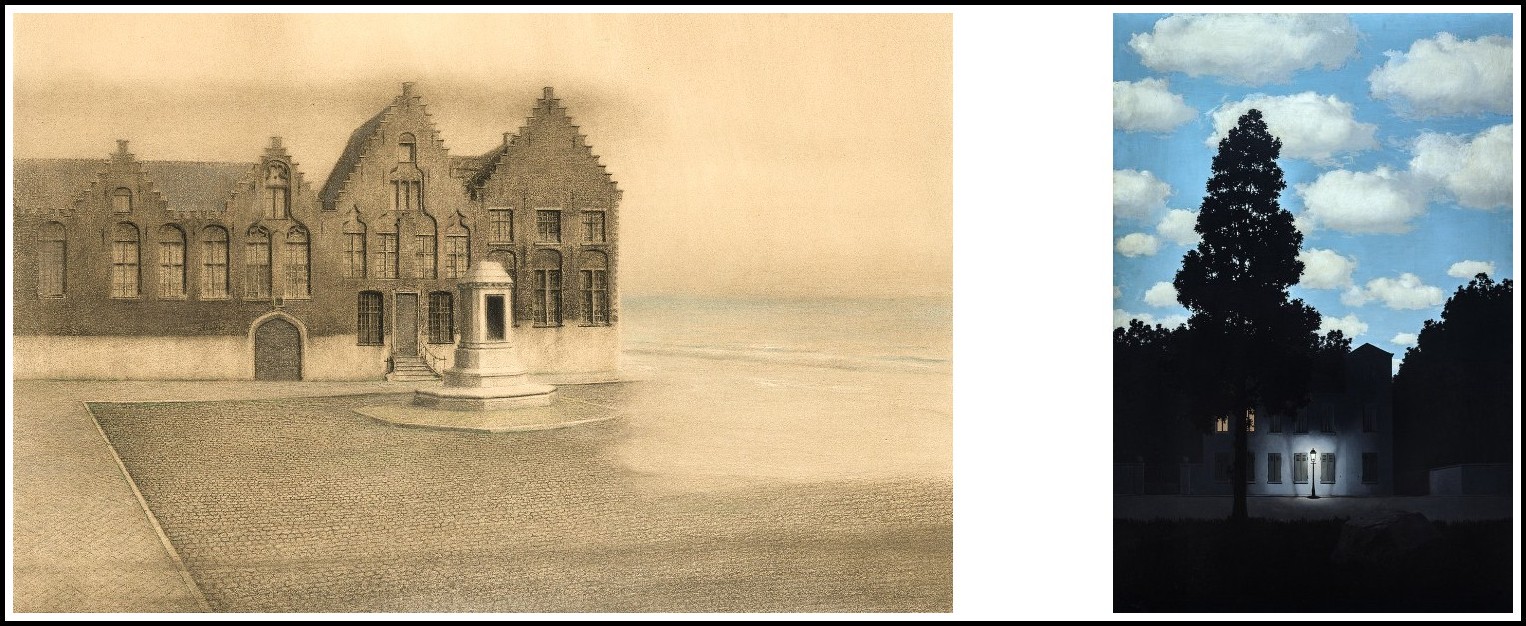

Breton: ‘It is true that our approach to Symbolism and the present craze for it bear the stamp of Surrealism. We want to replot the early path of a line that has been too long cut by the grade crossings of nothingness.’ Before Khnopff’s The Derelict City we think of Magritte’s The Empire of Light because both pictures crystallize the impossible. The Symbolist landscape par excellence is in fact the representation of a place glimpsed in dream. Khnopff’s deserted square of gabled houses, invaded by the sea as grass will obliterate the neat layout of a garden and lying open to that other source of obliteration, the sky, is a true poetic intersection, the crossroads of memory; it is also the capturing of an image that raps on the windowpane, in the Surrealist sense. Yet this apparition is a résumé of events that actually happened in the course of time, namely the silting up of the port of Bruges and the resultant decline of the city. The Empire of Light, on the other hand, juxtaposes two profoundly related opposites: in the upper part of the picture, a bright daytime sky; in the lower part, the facade of a house and a path plunged in darkness. The link between the two works derives from the fact that we look at the past through eyes that Surrealism has changed; its campaign of total emancipation has conditioned our reactions. Thanks to it we know that it is wrong to try and decipher Symbolist pictures, that their meaning goes much deeper than any code vaguely derived from an esoteric tradition, that no sieve of interpretation is fine enough to catch the subtle substance of their message.

Fernand Khnopff, The Derelict City, 1904 (detail) | René Magritte The Empire of Light, 1954

The mystery of Magritte, the mystery of Delvaux, the mystery of Khnopff, the mystery of Degouve de Nuncques and Spilliaert—each one a crystal ball transfiguring poetry, each one revealing that, as Novalis wrote, ‘all that can be seen cleaves to what cannot be seen, all that can be heard to what cannot be heard, all that can be felt to what cannot be felt; perhaps all that can be thought to what cannot be thought,’ each one stimulating our minds and senses with a desire to live poetry, passionately to immerse ourselves in it in order ultimately to fecundate life with the wild seed of seeing.

Paul Delvaux, The Viaduct, 1963

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2026 | All rights reserved

Comments