PART I: THE PLAY OF THE DOUBLE IN POSTMODERN FICTION | PART II: THE DOUBLE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

PART I

THE PLAY OF THE DOUBLE IN POSTMODERN FICTION

Gordon Slethaug

Posted by kind permission of Gordon Slethaug, Professor of English Literature, University of Waterloo

The following text constitutes the Prescript, titled ‘Rewriting the Double’, in Gordon E. Slethaug, The Play of the Double in Postmodern Fiction (Southern Illinois University Press, 1993) pp. 1-6

Andy Warhol, Tina & Lisa Bilotti, 1981

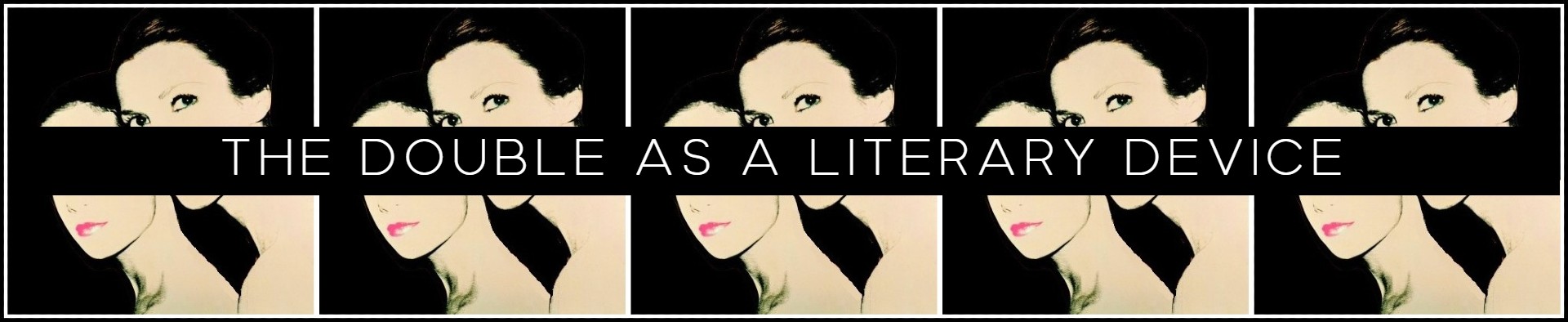

During the quarter century since Albert Guerard’s Stories of the Double reminded readers of a rich nineteenth-century literary tradition, stories like Melville’s ‘Bartleby the Scrivener,’ Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Dostoevsky’s The Double, and Conrad’s ‘Secret Sharer,’ with their haunted gothic centers and mysterious, twinned, but mirrored characters, have become fresh once again after having been eclipsed for a time by novels of social realism. Moreover, the idea of the double has seized the imagination of a number of the major modernist and postmodernist writers. Although there are many reasons for the appeal of the double, its continuing importance, Guerard insists, lies primarily in its serious exploration of the psyche: ‘Double literature (if it proceeds from a genuine imaginative act) is rarely trivial, though not infrequently comic. The issues are real and sometimes tragic, the psychomachia definitive or barely survived—whether the experience of seeing one’s double lead to a sense of resurrection or to a descent into psychosis, whether to classic split personality or to epileptic episode or to obsessive-compulsive behavior.’

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde | The Secret Sharer | The Double | Bartleby, the Scrivener

Elusive as the concept of the double is, a number of modern critics agree that doppelgänger are manifestations of psychological phenomena, and Clifford Hallam insists that ‘the Double (in fiction or otherwise) is directly related to Freud’s breakthrough in understanding the human personality.’ But if Freud made the breakthrough, it was Jung and Rank who gave the most precise analysis of ‘the mysterious bond between the protagonist and his closest friend, as well as the link between him and his enemy.’

Photos: Adrian Swancar

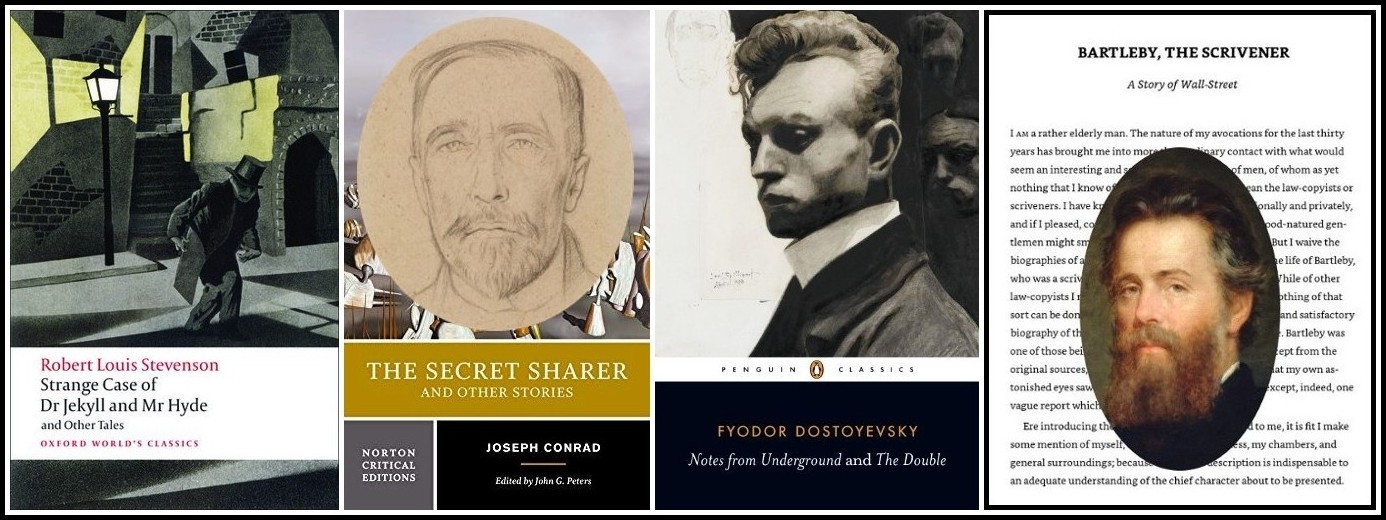

Recent critics, however, have begun to question the exclusive dependence of the double on some mysterious psychological bond. Tzvetan Todorov, for example, remarks in The Fantastic that:

Significations can even be opposed to one another, as they are in Hoffmann and Maupassant. The double’s appearance is a cause for joy in the works of the former: it is the victory of mind over matter. But in Maupassant, on the contrary, the double incarnates danger: it is the harbinger of threat and terror. Again, there are contrary meanings in Aurélia and The Saragossa Manuscript. In Nerval, the double’s appearance signifies, among other things, a dawning isolation, a break with the world; in Potocki, quite the contrary, the doubling becomes the means of a closer contact with others, of a more complete integration.

Aurélia | Tales of Hoffmann | The Manuscript Found in Saragossa | Apparition

Todorov’s observations about opposing significations reflect the rich variety of meanings attached to the sign of the double, which has been used to illustrate the desire for unity in the human personality and spirit but now signals double purposes, fragmented understandings, and self-parody in all life and literature. (Robert Rogers calls the self-parodying double a baroque double.)

Tzvetan Todorov, The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre

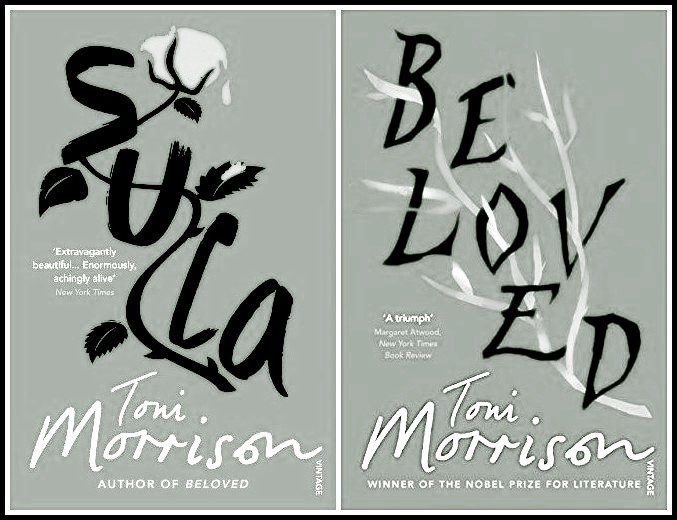

Traditionally, authors have employed the double to affirm rational humanist views of a unified and stable self and totalized cultures—what Paul de Man calls the self-mystified, transcendent symbol or signified—the coherence of God, self, and the word. We might call this position mimetic, representative, or natural, for as Carl Malmgren points out, the Aristotelian view that art imitates nature usually involves a ‘higher sense of a unified ethical vision connected in some way with the way we live now.’ While this view generally informs premodern texts dealing with the double, it is also common to such moderns as Saul Bellow, John Updike, Ursula LeGuin, Toni Morrison, Flannery O’Connor, and John Knowles. Both male and female writers have been attracted to this approach, which strives for pattern and order, values the subject, and emphasizes the synthesis and resolution of differences between dual aspects of the self, men and women, and privileged and repressed. Feminist fiction, especially that of a black writer such as Toni Morrison, is filled with doppelgangers that explore the status of ‘the other’ within a white patriarchal society. Sula and Nel, of Morrison’s Sula, embody opposite aspects of black women coerced by dominant cultural beliefs and practices into acting against their better instincts. Her Beloved presents the emotional and legal difficulties of a black woman who kills her daughter to protect her against her white master, only to discover that she comes back to life to seek the love she was denied. Here the use of the double reveals the complex nature of the sacrifices and love borne by black women.

Toni Morrison: Sula | Beloved

Recently, however, the double has taken on a new identity: moving away from a consideration of the Cartesian self—an indivisible, unified, continuous, and fixed identity—and universal absolutes, the double in postmodern fiction explores a divided and discontinuous self in a fragmented universe. Its mission is to decenter the concept of the self, to view human reality as a construct, and to explore the inevitable drift of signifiers away from their referents. It assumes that the human being is a locus of contradictions in a reality of conflicting discourses and discursive practices. This formalist, performative position displaces the mimetic stance, values artifice over verisimilitude, substitutes writing for experience, pluralizes narrative points of view, and esteems the autotelic and self-referential in fiction. In recognizing previously marginalized modes of narration and depictions of characters, it confirms the split sign, the split self, and the split text.

Tom Wesselmann, Still Life No. 20, 1962

It should be made clear at the outset that this study is not an inquiry into postmodernism; it is concerned with how the idea of the double is employed by certain American authors generally considered postmodern. John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Richard Brautigan, Robert Coover, Raymond Federman, Leslie Fiedler, William Gass, John Hawkes, Vladimir Nabokov, Thomas Pynchon, and Kurt Vonnegut, for instance, steer clear of realistic presentation, frustrate the reader’s search for coherence, and demystify transcendent symbols of unity. Like the work of other postmoderns, theirs interrogates the present order of things not to present a single, clear-cut new answer but to call into question a rational, consistent order of reality, to transgress social and literary conventions, to debunk a correspondence between the experiential or real world and the text, to raise possibilities of a multiplicity of credible answers, and to use traditional elements of fiction ironically and parodically but without satiric motives. This approach, as Linda Hutcheon suggests, results from the ‘postmodern urge to trouble, to question, to make both problematic and provisional any desire for order or truth through the powers of the human imagination.’

Tom Wesselmann, Bathtub No. 3, 1963

For some, like Jean-François Lyotard, Fredric Jameson, and Terry Eagleton, postmodernism is an art form located within a particular epoch and responsive to historical conditions, though it may choose to ignore the lessons of history. Lyotard thinks that postmodernism is a way of seeing closely linked with existential assumptions and beliefs, but Jameson and Eagleton view it as a product of late capitalism and the postindustrial society in which nothing has value in itself but is nevertheless bought and sold at a frantic pace. History itself has become a commodity; that is, concepts of history are readily incorporated into corporate structures and art and are thus commodified. Although Lyotard makes no objection to postmodernism on these grounds, Jameson and Eagleton do. Because of the blurring of forms, juxtaposing of social periods, and ambiguity and duality of perspective, Jameson finds in postmodern art a depthlessness and commodification, a weakening of historicity, a depleting of contextuality, and a trivializing of culture.

Andy Warhol, Diamond Dust Shoes, 1980 | Vincent van Gogh, A Pair of Boots, 1887

Another critic, postcolonialist Helen Tiffin, goes even further in condemning postmodernism, claiming that it is European in origin and ‘operates as a Euro-American western hegemony,’ appropriating cultural and historical materials of the marginalized and oppressed everywhere. Linda Hutcheon and Charles Jencks, however, find that its refreshing irreverence for both history and literature implies a recall and reappropriation of the past as well as a reassessment of its relationship to the present. To some extent these two critics exist on the boundary between those who see postmodernism in a political sense and part of the contemporary period and those who regard it as an aesthetic form consisting of various textual strategies and devices. Jencks regards postmodernism as an artistic phenomenon that breaks down traditional codes of art and, when it uses conventions, does so ironically and parodically. It is a peculiar kind of reinvention without a discursive message beyond the confines of art itself.

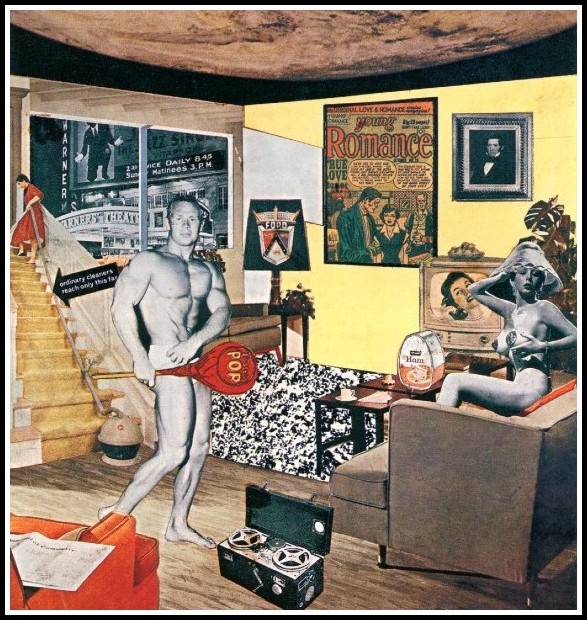

Richard Hamilton, Today’s Homes, 1956

Although some critics, like Jerome Klinkowitz, assume that structure and theme are likely to be identical in postmodern texts, no such conclusion can generally be drawn: these works are as often as not self-contradictory, self-divided, and fragmented. It is this self-contradiction that Todd Gitlin identifies as characteristic of the movement: ‘It consistently splices genres, attitudes, styles. It relishes the blurring or juxtaposition of forms (fiction-non-fiction), stances (straight-ironic), moods (violent-comic), cultural levels (high-low). It disdains originality and fancies copies, repetition, the recombination of hand-me-down scraps. It neither embraces nor criticizes, but beholds the world blankly, with a knowingness that dissolves feeling and commitment into irony.’

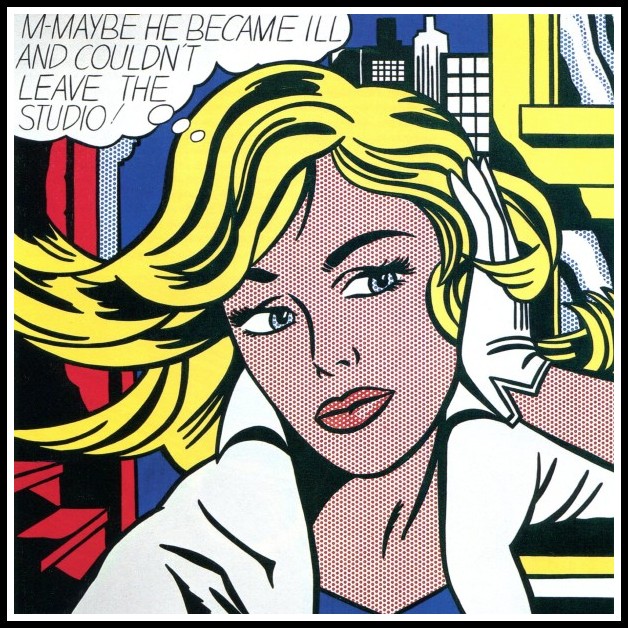

Roy Lichtenstein, M-Maybe, 1965

lhab Hassan constructs a similar list, emphasizing pluralism: for example, indeterminacy, decanonization, and carnivalization. These contradictory perceptions of postmodernism bring home fully the issues of plurality, fragmentation, and historical discontinuity that are at the heart of the movement. Although few agree on what postmodernism is or what it accomplishes, I see it as rejecting the existence of consistent personalities and psychological wholeness as well as any stable relationship between signifiers and signifieds. To me, it also emphasizes destabilized and duplicitous meanings, self-reflexivity, discontinuous and polyphonic discourses, arbitrary codes, and inclusion of previously excluded or ignored discourses.

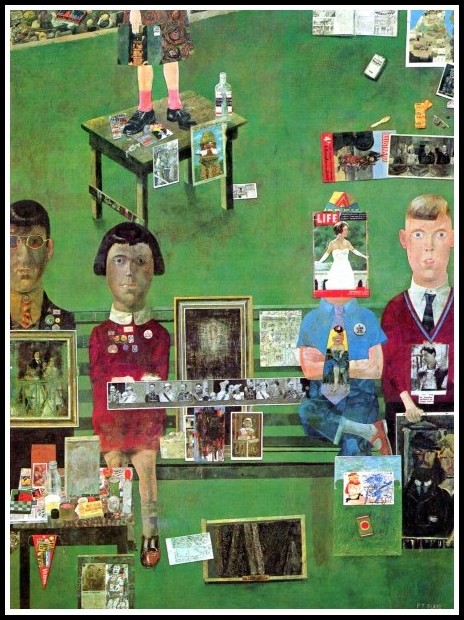

Peter Blake, On the Balcony, 1955-57

In denying spiritual and psychological completeness or transhistorical, permanent meaning, postmodern authors of the double often make assumptions about culture in general, for personal identity is caught up in the relationship between self and culture, self and history, self and language. Identity, like other linguistic and social codes, is wrapped in the tissue of signification, and it demands de-formation. As John Stark suggests, the creation of doubles often ‘implies that identity is a false category: if two people are alike, or in a simplified double relationship, neither has a unique, well defined identity of his own.’ Paul Coates similarly finds that the double exists in literature because of our inchoate knowledge that we are incomplete and that we cannot master ourselves. The postmodern double raises questions about fixed categories and constructs, especially about the notion that any human being has a unified identity.

Sigmar Polke, Friends, 1966

As a result, the fiction of the double tends to be anti-mimetic and anti-epiphanic, undercutting the view that a literary character must of necessity learn something new and grow to maturity and psychological wholeness. It often accomplishes this aim by introducing multiple narrative perspectives or faulty first-person ones, so that the basis of human perception is questioned. For Dick Higgins, postmodernism rejects reality’s and fiction’s dependence upon stable cognitive underpinnings or goals; this ‘post-cognitive’ interrogation of self, as he calls it, is part of a major reassessment of the self within contemporary culture and becomes a metaphor for the interrogation of all formal social structures and discursive practices. For Linda Hutcheon, the metaphor of splitting in Salmon Rushdié s Midnight’s Children and the doubling effect in D. M. Thomas’s The White Hotel help to identify the postmodern emphasis upon multiple subjectivity, cultural diversity, and plural narratives as well as the erosion of ‘the empirical basis of the humanist and positivist concepts of knowledge.’

D.M. Thomas, The White Hotel | Giorgio de Chirico, La matinée angoissante, 1912 | Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children

In exploring these postmodern possibilities for doubles and doubling, my study will deal with representative works of six postmodern American writers: Nabokov, Pynchon, Hawkes, Barth, Brautigan, and Federman. Each in his own way has significantly ‘deformed’ and ‘re-formed’ the double; each is concerned with the postmodern inquiry into structures and rules of signification in society, fiction, and language; and each is interested in undermining and replenishing them. Nabokov, Pynchon, Hawkes, and Barth are chosen not only because of their pervasive use of the double but because they are generally considered to be among the most important postmodern American writers; Brautigan and Federman are included because their use of the double is more eccentric, more outrageous, more avant-garde, and less privileged than that of other postmodernists. Other figures, such as Barthelme and Vonnegut, could no doubt be added, but their inclusion would not significantly alter my thesis. This study will not, and cannot of course, be exhaustive. Neither postmodernism nor the double is a static literary motif, construct, movement, or style. Both contain numerous irreconcilable contradictions, and both will continue to change; readers should rightly challenge some of my implicit assumptions and explicit categories. Still, I have defined postmodernism and looked at the double in ways that I hope will indicate their wide-ranging possibilities and help readers rethink their ways and uses.

Richard Brautigan by Dave McKean | Vladimir Nabokov by RJ | Thomas Pynchon by Joe Ciardiello

GORDON SLETHAUG: THREE BOOKS

GORDON SLETHAUG

Music and the Road

GORDON SLETHAUG

Adaptation Theory

GORDON SLETHAUG

Beautiful Chaos

PART II

The Double as a Literary Device in ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

THE MOTIF OF THE DOUBLE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

A Variation of the Double Motif in the Novel by Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan

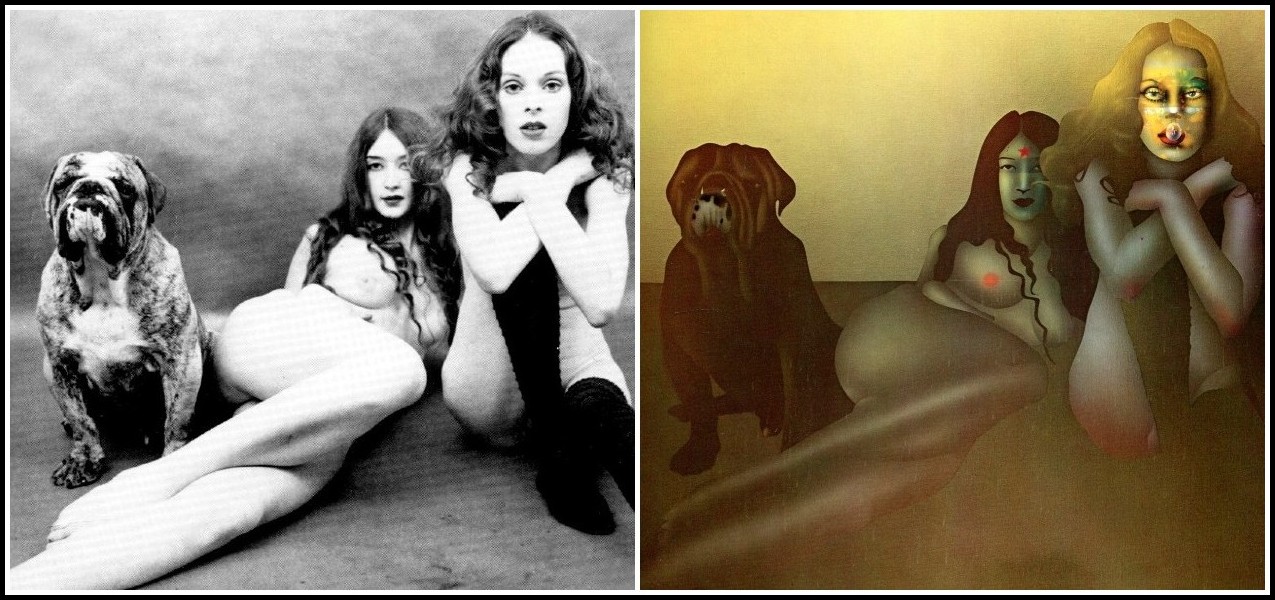

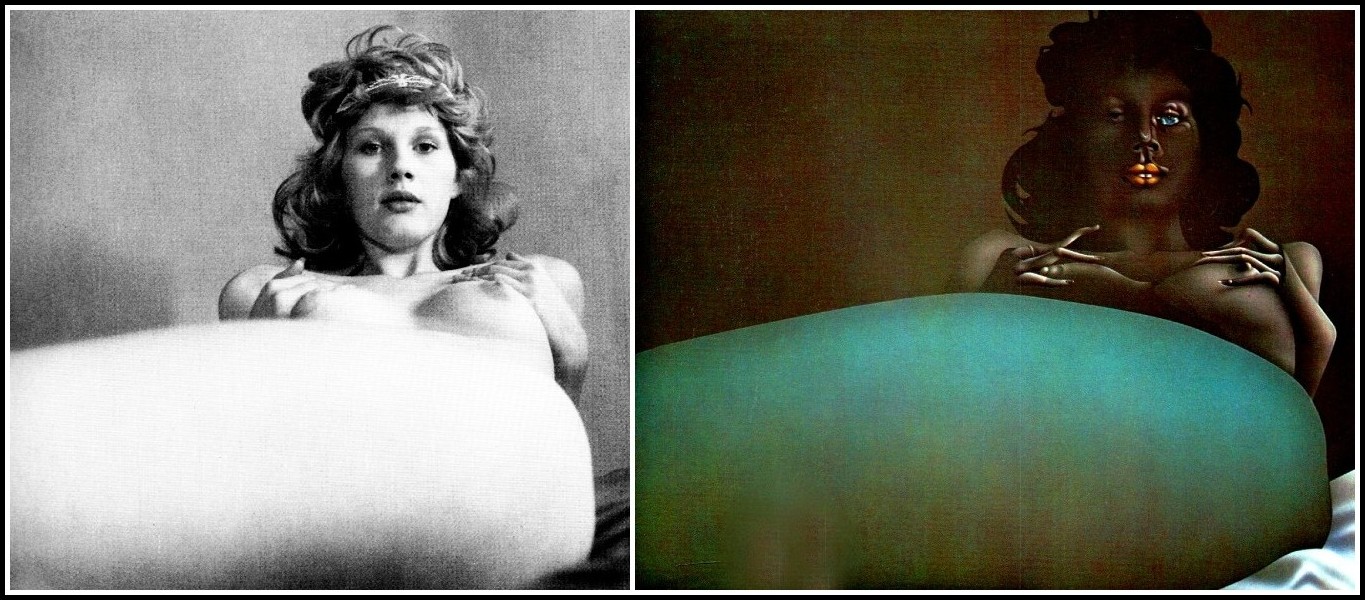

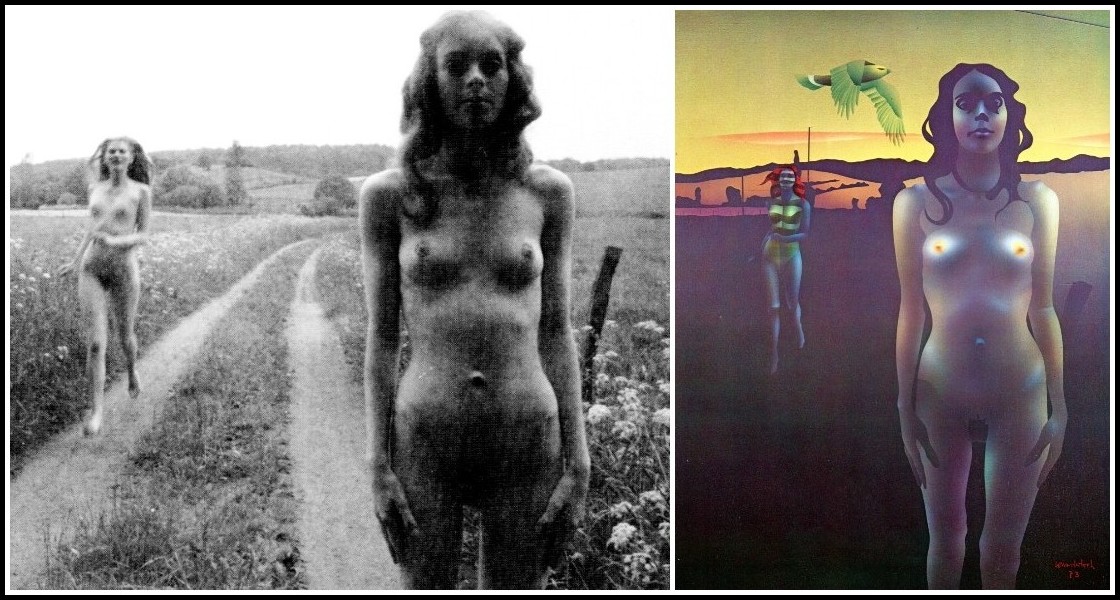

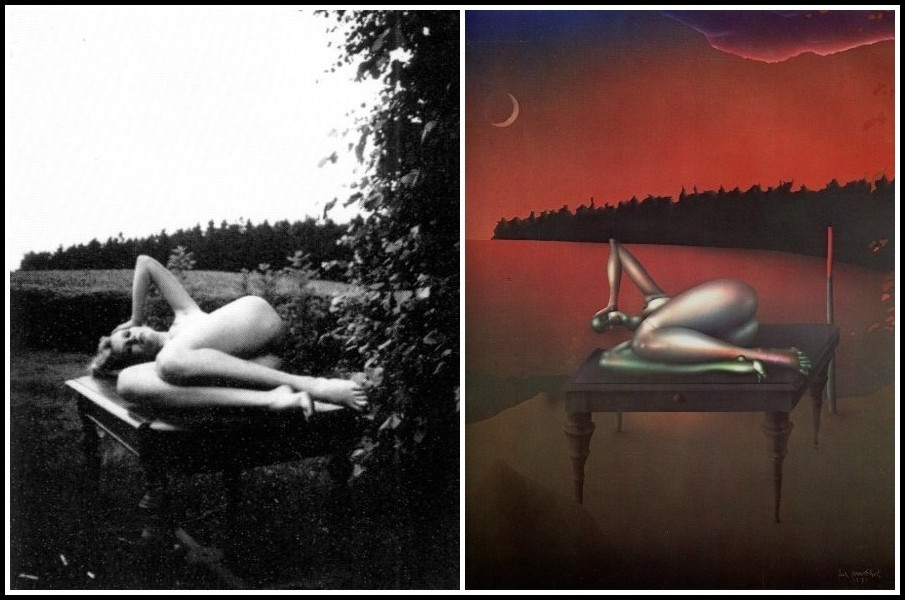

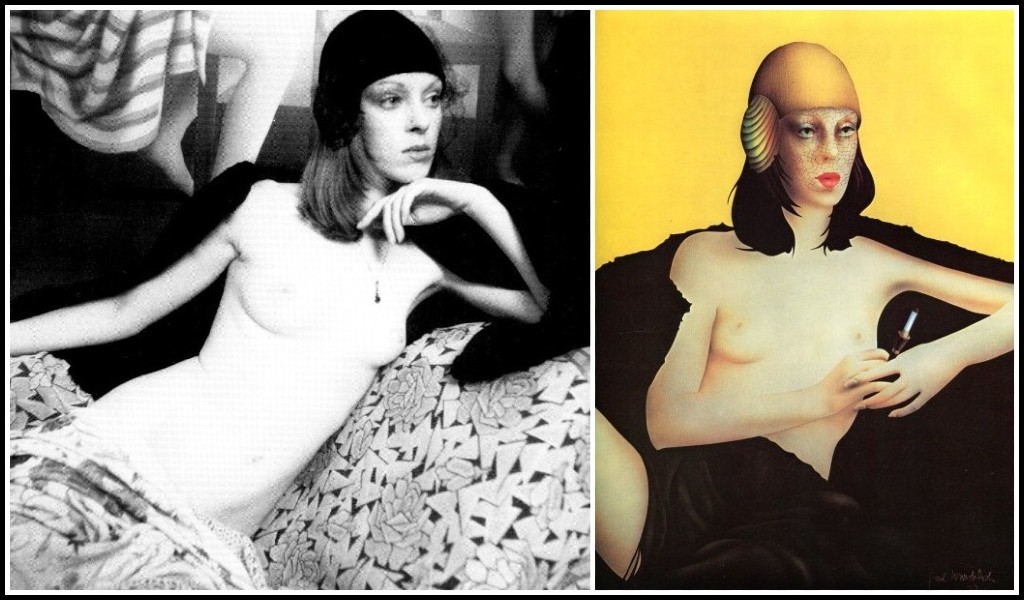

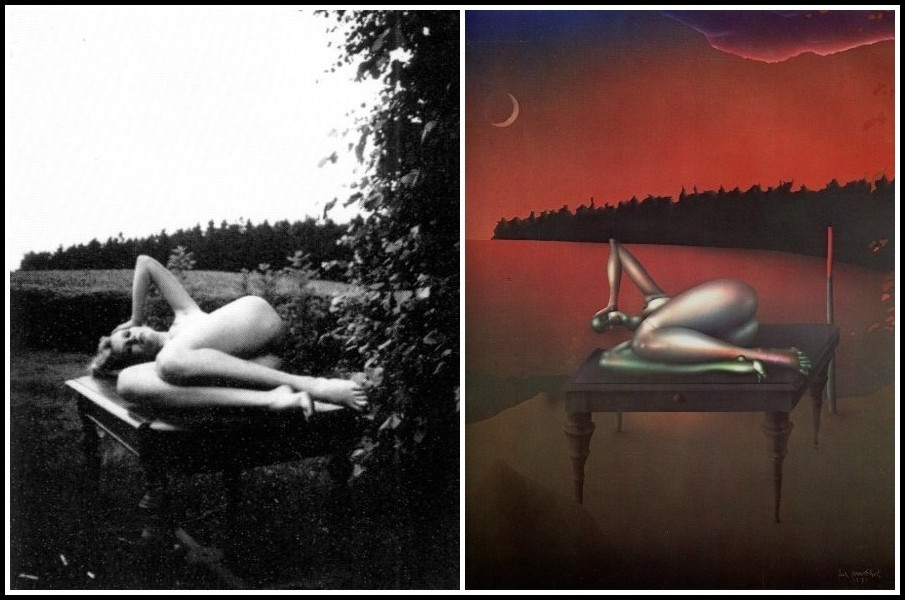

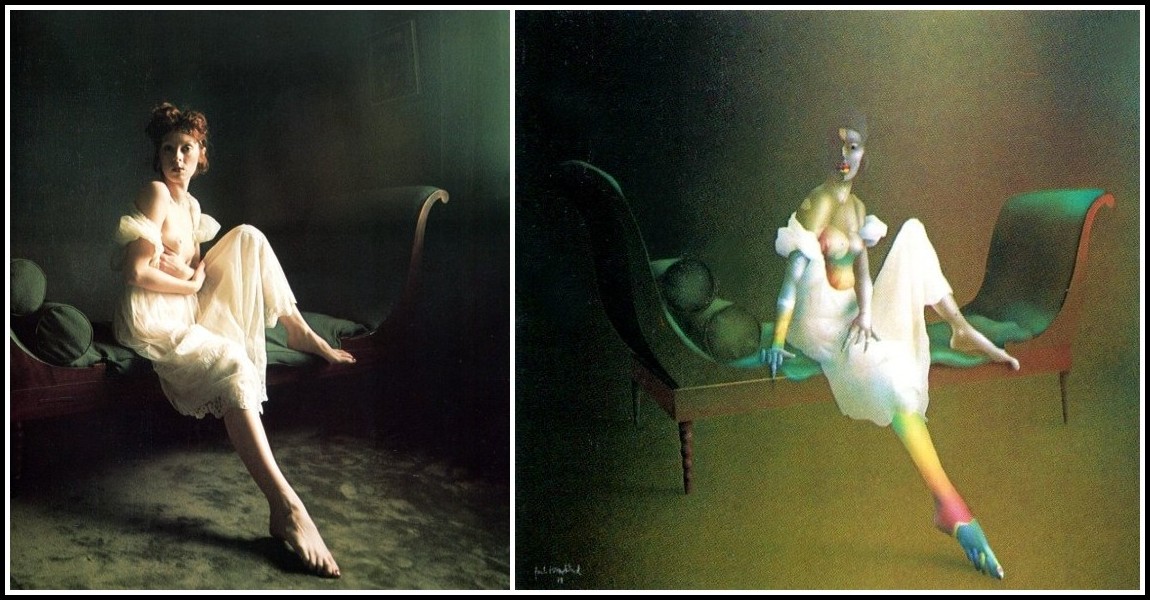

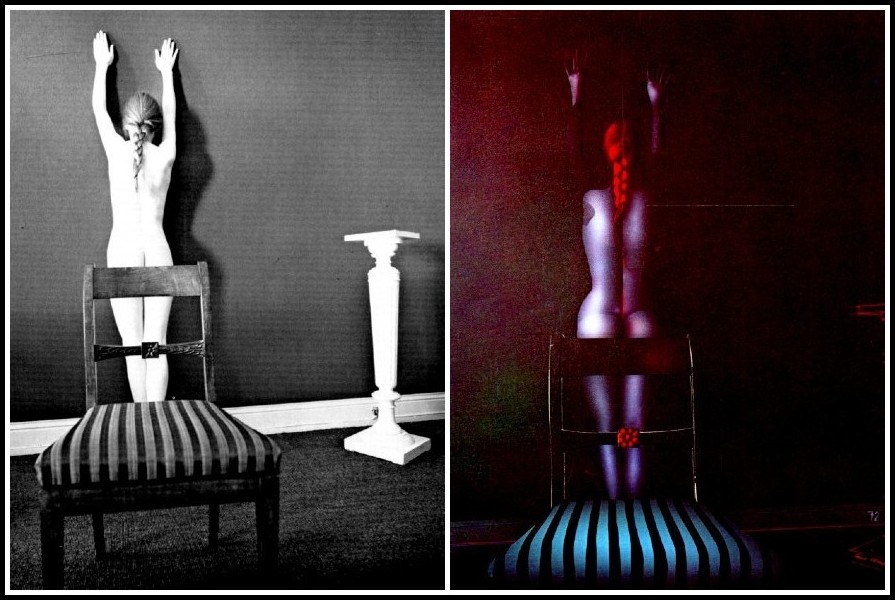

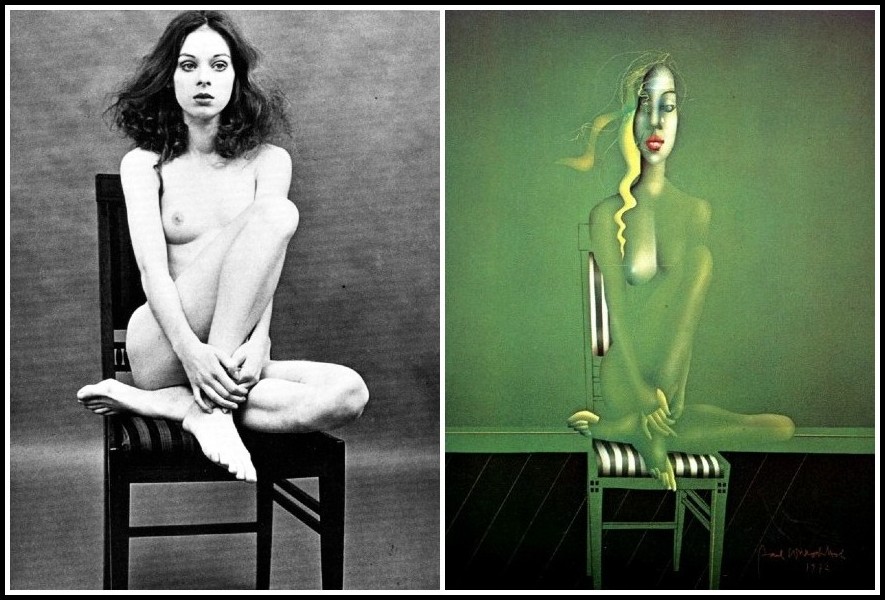

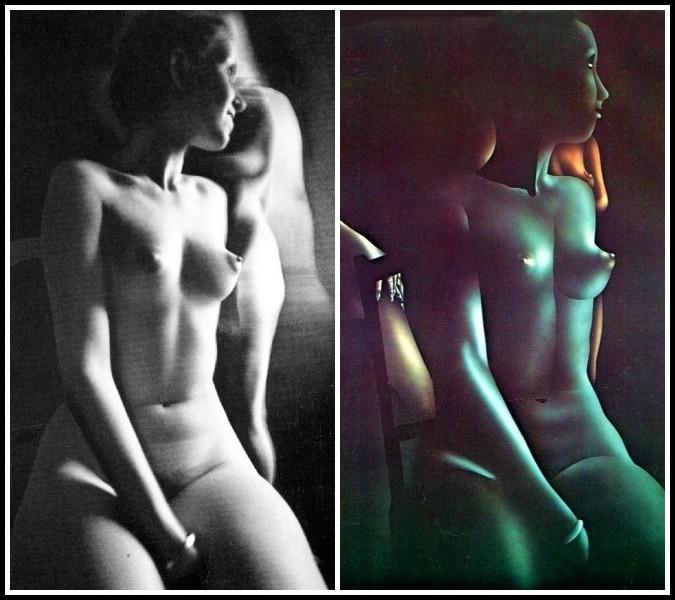

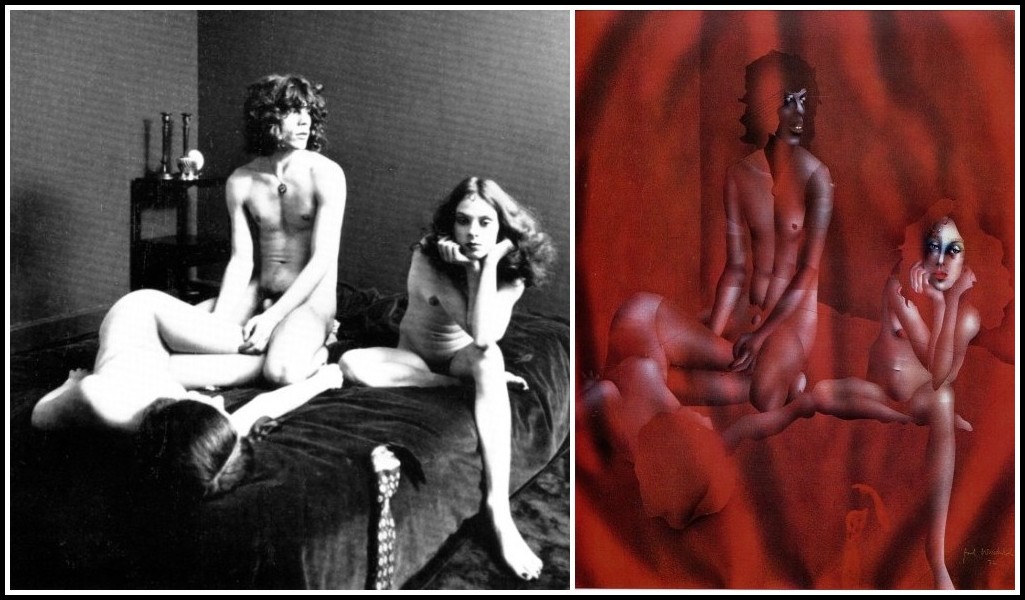

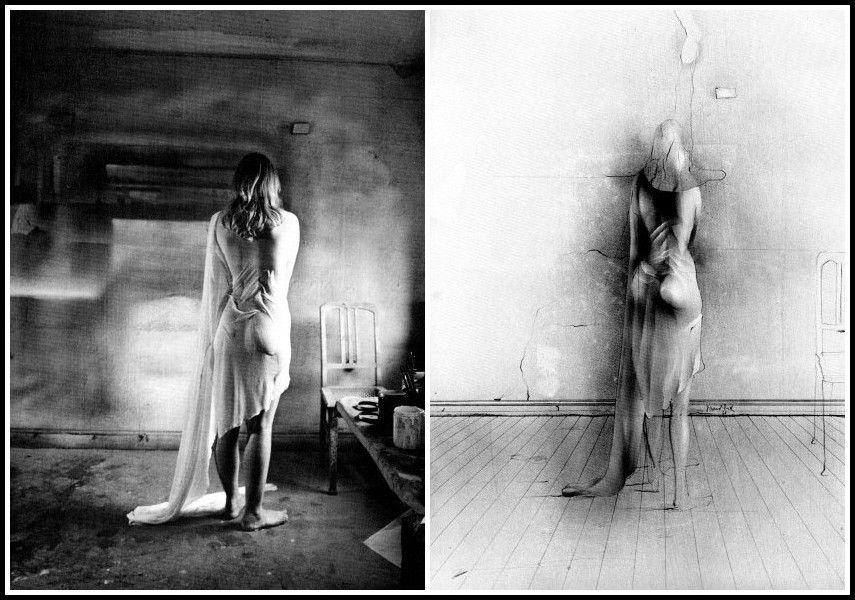

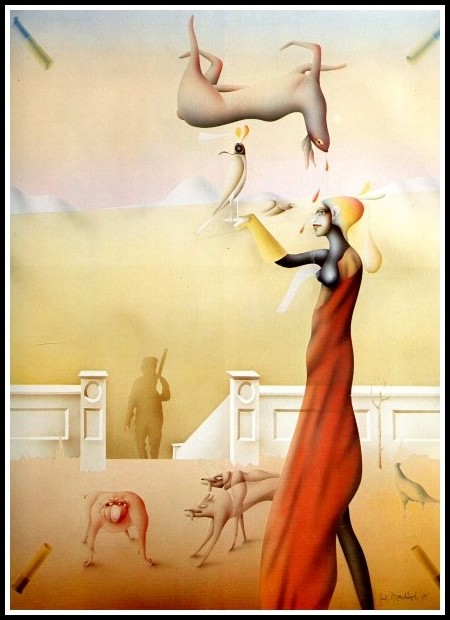

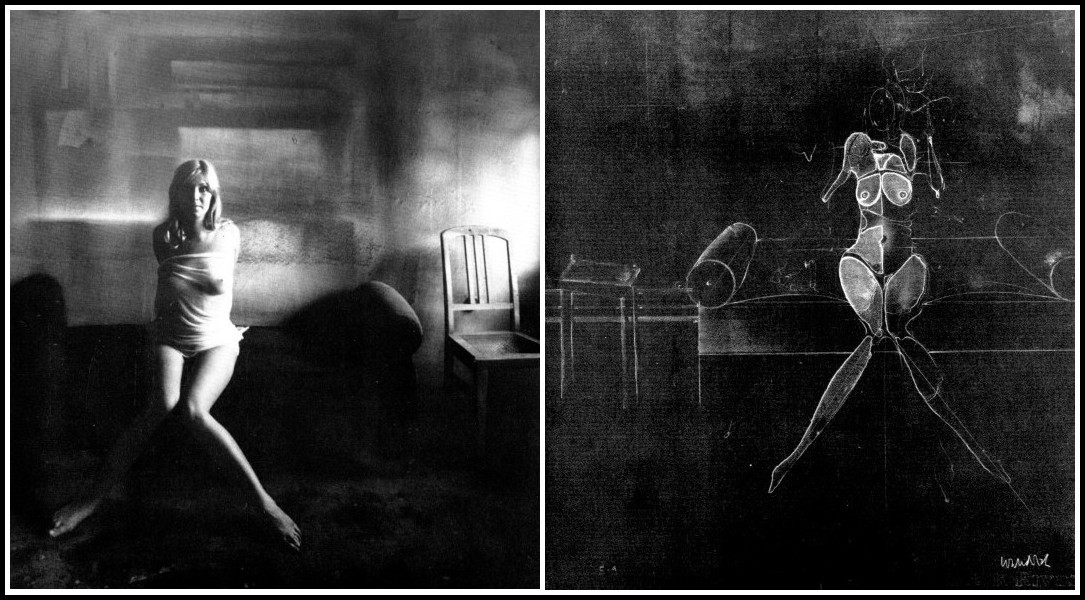

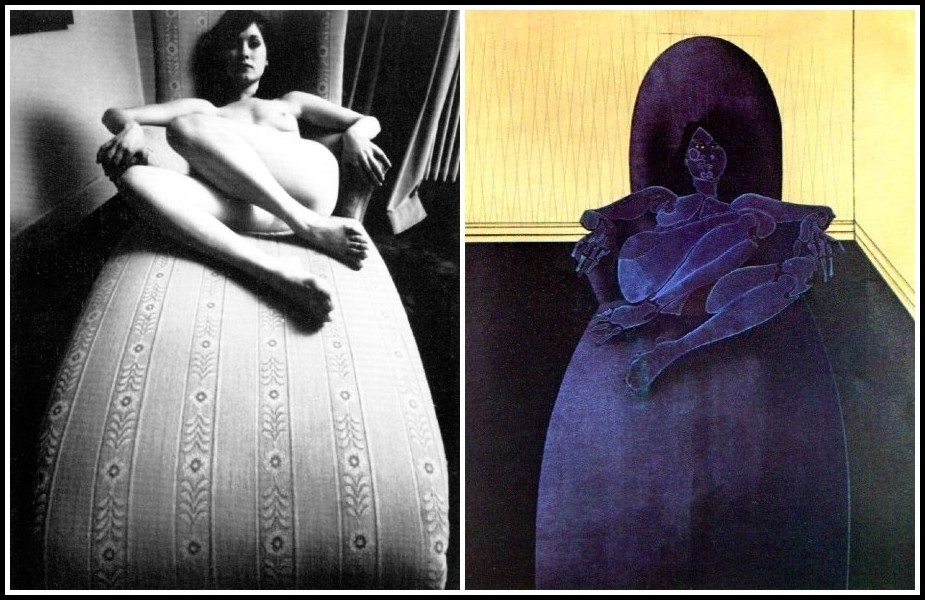

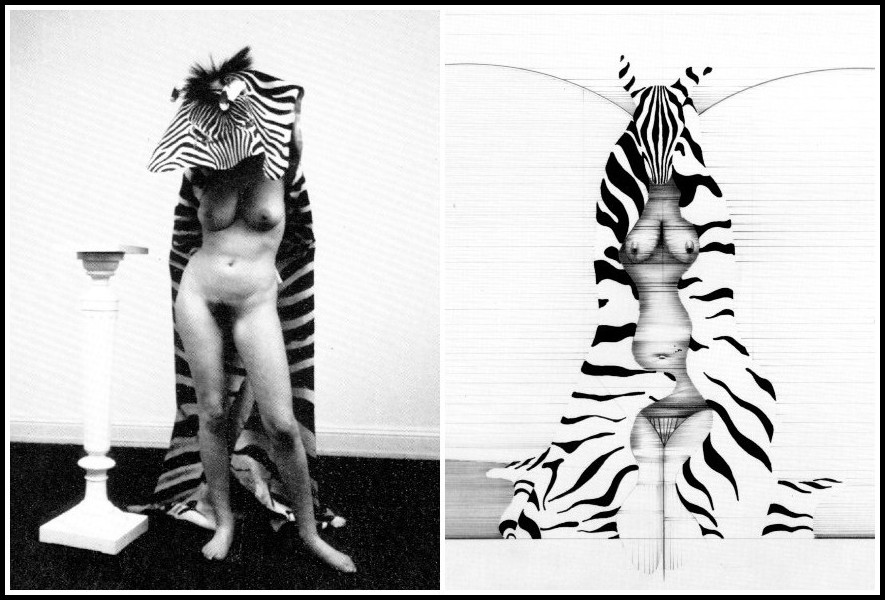

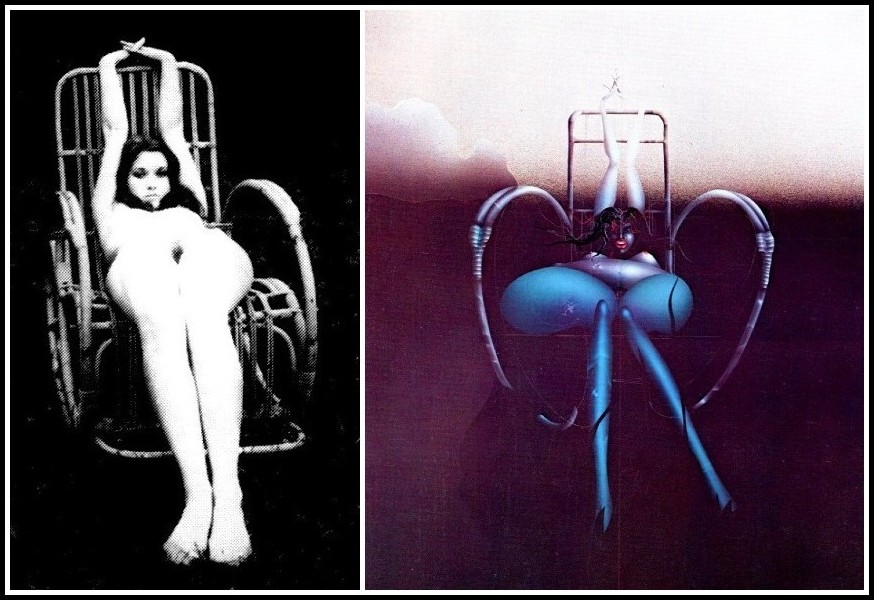

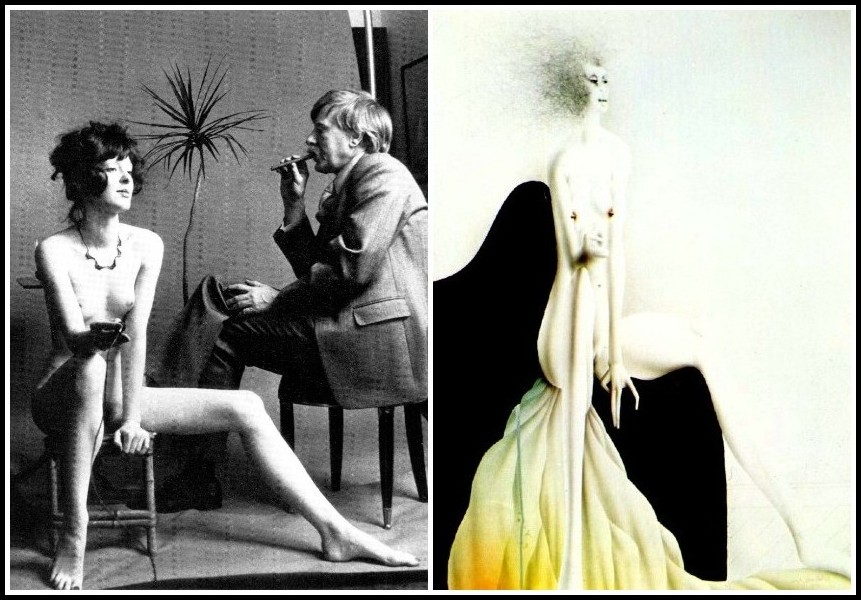

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

MARA, MARIETTA: ONE CHARACTER, TWO INCARNATIONS?

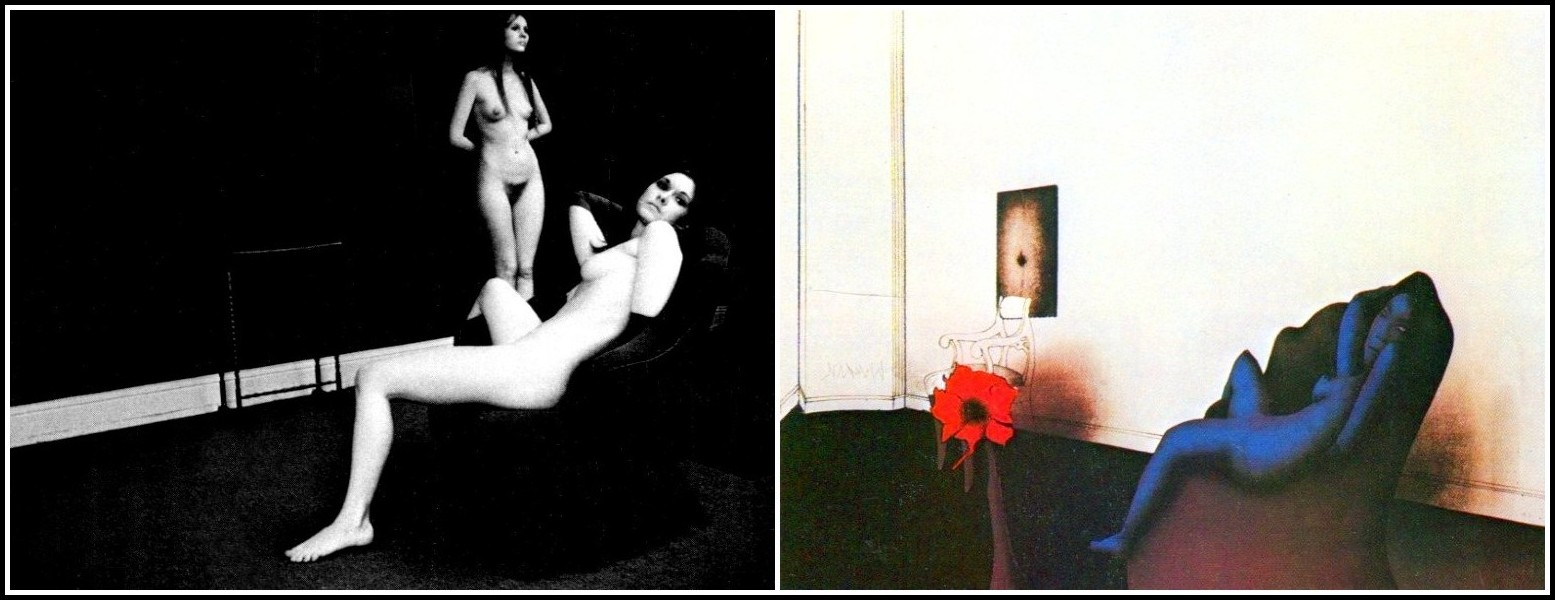

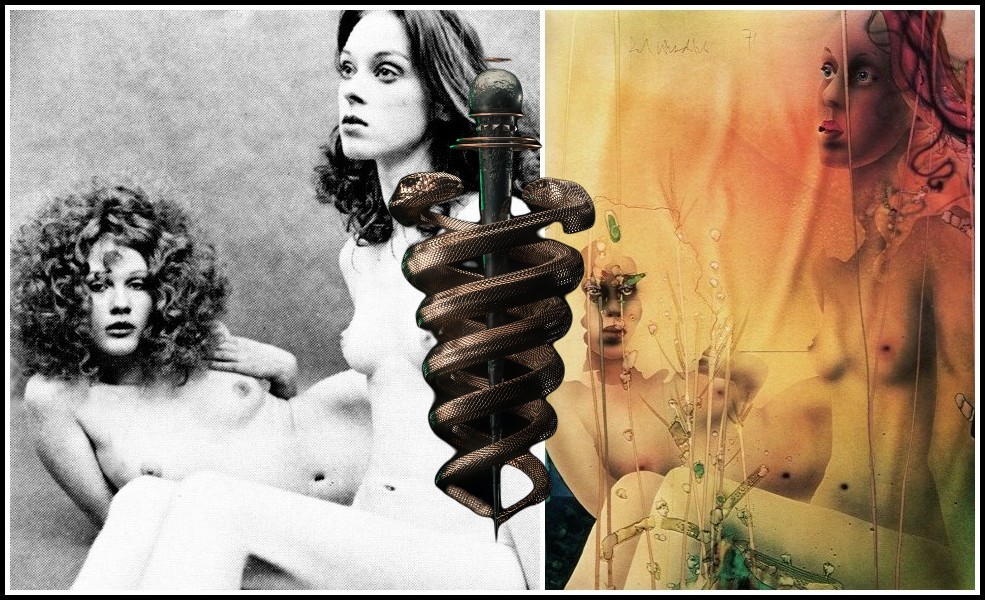

The motif of the double figures prominently in my novel, Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms. I employ the device, however, differently from the way it is traditionally used. To simplify, we can say that the ancients used it to indicate a physical/spiritual division and the Romantics a good/evil split, while the postmoderns used it as a vehicle to undermine verisimilitude. Today I can still read with pleasure the ancients and the Romantics, but the postmoderns leave me cold. Why? Because they do not engage my emotions. Consider the caduceus, the emblem of Hermes, which I use to represent my literary aesthetic. It shows two serpents threaded in opposite directions around a wand. In my appropriation of the symbol, one serpent stands for thought and the other for emotion, while the wand represents a magic synthesis of feeling and form.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork) | Shrey Deepranjan (caduceus)

That synthesis is precisely what I set out to achieve in Mara, Marietta. Without feeling form is sterile, and without form feeling is ephemeral. Feeling—risking one’s skin in an attempt to find an organic form to express one’s obsession—is a big factor, I suggest, in accounting for why some works stand the test of time and others do not. Manet’s Olympia was derided in the same year Cabanel’s Birth of Venus was applauded: today it is Manet’s individual vision that is more esteemed than Cabanel’s academicism. Form derived from feeling, then, surpasses feeling subservient to form. And thus it is that if I, like the postmoderns, employ the double as a means to negate unicity and thereby undermine mimesis, my literary outcomes are the opposite of theirs. Indeed, where in their novels you find ‘depthlessness, ahistoricity, absence of context and trivializing of culture’ (cf. the reference to Frederic Jameson’s argument in Part I), in Mara, Marietta you find depth (psychological, for example), history (Srebrenica, for instance), context (‘what we make of what others have made of us’, as Sartre puts it), and culture (from culinary art to visual, from dancing in a club to colliding particles in a lab).

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

The reader of Mara, Marietta will decide for themself, should the question occur to them, whether the two heroines are in fact one, but they will not be led on a wild ‘postmodern’ goose chase searching for clues: that kind of game playing may be fun for a while, but ultimately it is sterile. No, what I am offering you, dear reader, in Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms, is a much more rounded experience, one in which both heart and mind will be engaged in depth. I reject both the recycling of clichés and the reshuffling of conventions; instead, I find new forms for feeling. Here, then, I offer you five sets of parallel excerpts from the novel. Each set, as ‘parallel’ suggests, consists of two excerpts, one with Mara and the other with Marietta. The echoes between them figure the double in Mara, Marietta, a figuring that is reinforced by the multiple instances of twinship in the novel, and reinforced again by secondary doublings (Marietta and Jagrati, for example, or Mara and Ingrid). I leave you to discover these affinities for yourself: a good novel requires nothing more than a good reader.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

I. MARIETTA: THE ABSENT MOTHER | MARA: THE ABSENT FATHER

What is of interest to someone—what Freud called their preconditions for loving—is both recondite and profoundly idiosyncratic, a function of the strange weaving of personal history and unconscious desire.

Adam Phillips, The Beast in the Nursery (Faber & Faber, 1998) p. 57

In this set of parallel excerpts, we see an element of the heroines’ personal history (an absent mother for Marietta and an absent father for Mara) that, the novel shows, have been influential in forming their respective ‘preconditions for loving’, particularly as regards sexuality and eroticism.

[The first excerpt is a dialogue between Marietta and Sprague, with Sprague speaking the first line.]

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 2 | Marietta

̶ You know the landscape well.

̶ Yes, we’d often go hiking. My father would teach me the names of the plants and animals, their characteristics.

̶ Do you still remember them?

̶ Of course. Creeping buttercup and rock rose, Bonelli’s eagle, the Barbastelle bat. Speaking of bats, one evening, when I was alone in the house, a bat flew into my bedroom!

̶ Wow! What did you do?

̶ Scream!

̶ And then?

̶ Well, my first reflex was to get out and close the door, but then I realized that if I didn’t actually see the bat leaving my room, I’d never be sure it had left.

̶ That’s a scenario for a horror story!

̶ And that’s what it felt like. So I closed the door, left the window wide open, then crouched down in a corner and waited.

̶ For how long?

̶ Ages, it seemed. The damned creature kept tracing crazy patterns in the air and wouldn’t fly out. Finally, it clung to the stucco wall and stayed still. I could barely make head or tail of it, only its beady eyes caught the light.

̶ Foreboding, a vampire!

̶ I’ll say!

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

̶ Then what did you do?

̶ I remembered a pair of gardening gloves had been left on the window ledge. I put them on, approached the bat, and caught it! Oh Sprague, I can’t tell you what I felt at that moment, holding the bat in my hands!

̶ You felt aroused.

̶ How did you know?

̶ It’s a transgression, holding a bat in your hands. You’re holding the absolute other. That’s perfect for generating sexual excitement. Did you masturbate that night?

̶ No, but I had nightmares. Nightmares in which I’m sure I came!

̶ Nightmares about bats?

̶ Bats, boars, eagles—tearing my insides out! It was… thrilling…

Never confusing desire with the love you saw in his eyes, your father could be a bat, an eagle, a boar, but you’d never know it: He’d always remain your father.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Four Chapter 7 | Mara

Hand-in-hand with your father in a field bright with poppies, you walk down to a lake. Along the shore he points out the wild ducks and water hen, the lilies and the reeds, and shows you how damsels differ from dragonflies. Faeringa! Panicked wings scrape your skin, claws harrow your flesh: In a fever of determination a crow—trapped under your shirt—tries desperately to free itself. His black feathers turn crimson as your white shirt turns red; in a pandemonium of movement his talons lacerate your flesh. Between your flayed back and your blood-wet shirt, the bird grows bigger and bigger; when you feel the shroud of his blackness spreading around your body, you wake up screaming.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

II. SELF-TRANSCENDENCE VIA MUSIC – MARIETTA: VIOLIN | MARA: VOICE

For one minute after another Van Morrison cries, moans, pleads, shouts, hollers, whispers, until finally he breaks with language and speaks in tongues, growling and rumbling. The feeling is that whoever it is that is singing has not simply abandoned language, but has returned himself to a time before language, and is now groping toward it.

Greil Marcus, Listening to Van Morrison (Faber & Faber, 2010) p. 64

In this set of parallel excerpts, we how music, for both Mara (voice) and Marietta (violin), serves as a vehicle for self-transcendence.

[In the second excerpt, Sprague is writing to Marietta, reflecting on his experience of listening to a recording of Mara singing.]

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 3 | Marietta

High your elbow brings the bow across to the deep string; when you draw it you draw out my entrails: With a wrenching intensity you sculpt the phrase, then singe the air with the determination of your down-bow. Your hair shivers as you resume the attack, inundating the auditorium with your dark, shuddering tone. Isolated in the spotlight, your body is a blend of tension and serenity, a suicide’s razor before it kisses the wrist. Listen! There’s violence in that melody, there’s death in that dance! You are Ravel’s gitane, determinedly asserting her identity. In the face of all who would rather forget, you affirm that in Lucifer’s blackness there’s a brightness no other angels possess. The slide of your fingers between the pitches, the biting attack of your bow; the brilliance of your left-hand pizzicati, the idiosyncratic pulse of the beat: Infused with savage resolve, you walk the razor’s edge. Swift as blood, slow like honey, into the night-space you pour out your spirit. In searing tenderness your violin soars; out of silence you coax secrets. You are the object of all eyes as you stand in the spotlight, but for yourself you are no object: Your concern is not about how you move but about what moves you. You spread your legs, flex your knees, and play the melody in pizzicati. Gone is any notion of the female body as a burden; absolute in its freedom, with precision and grace your body deploys itself in its own private space.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Seven Chapter 2 | Mara

Silence. And then it comes, the sense beyond signification, the singular voice threading its mystery through me. How, Marietta, could I ever convey the ravishment I experienced in those thirteen minutes? The voluptuous fusion of language and body, the festive return to a primordial state—how? Music alone can fetch a world from beyond meaning; only song itself can communicate the incommunicable. In those thirteen minutes, the ecstatic performance by an unaccompanied soprano of four electrifying songs shivered my spine and shook my bones. Listen! Intricate melismas, awkward intervals; sublime tone, perfect pitch: Along the full range of her tessitura, the soprano places the syllables of her idiomatic song. Subtlety of nuance vies with intensity of expression, full-throated glory with elusive transparency. Expressing a dark and passionate vehemence, she varies the pressure as she moulds the vowels; evoking an other-worldly dreaminess, she drains her voice of all vibrato: I hear the scream of the butterfly. Listen! Floating a pure, ringing tone, she soars to a radiant high; in brilliant dark timbre, she marks the subterranean movement of a line. Speech-song or cantabile, vocalise or outcry, beyond vocal effects, the colouristic expression of pitches gives sense to the sound. Between attack and extinction, what artistry in sustaining tension! Listen! The sober gravity of incisive articulation, the compelling beauty of a long-breathed line; the beguiling movement across a span of pitches, the furtive emergence of muted vowels. Operatic in its breadth of register, dramatic in its large intervallic leaps—What is this masterpiece? Listen! Glissando connections and glottal attacks, a shimmer of rich overtones; the exhilaration of continuous vocalization, the sadness of decay between notes. Essence of music, purest of instruments, the voice as miracle: What immediacy, what intimacy, what bodily presence! When the final tone dies it is I who am breathless.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

III. SELF-TRANSCENDENCE VIA SPORTS – MARA: SKIING | MARIETTA: HANG GLIDING

Where danger is, grows the saving power also.

Hölderlin.

Both Mara and Marietta are drawn to extreme sports, finding the risk inherent in it irresistible. For each, the sharpening of the senses is a sharpening of the self, and daring to risk is the opposite of neurosis. Their motto, as Sprague reminds Marietta, is: ‘You can’t commit suicide with a safety blade’. But Marietta, like Mara, hardly needs reminding: risk is the foundation of her ethics of living.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Six Chapter 2 | Mara

Bending the straight line of momentum into arabesques of grace, you speed down Mount Kanin. On a white planet where people don’t belong, there you feel free! You’re amazed you’re capable of such feeling again (you’re thirteen and a half years old, it’s five months since your father killed himself). Faster, faster, faster! You thrill to the throbbing in the soles of your feet and to the touch of snow on your tongue; in command of your body, you push to the limit of losing control. Catching the air after a bump you catch a glimpse of the Adriatic; adjusting your edge angle you round a mogul then once more face the fall line. Schuss! Over ice, down an extreme steep, tucked down low you glide. Under your body you feel the mountain; fascinated by its secrets, you court the danger of short-changing friction for gravity. What is it you are looking for? Falling weightless into the turn, you hover between bliss and foreboding. You drop your hips, bringing your body farther inside the arc of the curve; to a higher edge angle the stance ski rises: In movement the smallness of your body embraces the immensity of the mountain. The side-cut and camber of your skis give a brisk bite to your edging; searching for the position that knifes the blood, in the place where desire confronts fear you carve a crisp, clean arc. Rushing on your run, zigzagging down the mountain, into the time that forms your history you insert yourself. Schuss! You’re certain now that your future depends on how you interpret the past. At the bottom of the piste you perform the phantom move and parallel turn to finish. Lifting up your goggles, you raise your eyes to the mountain. Your racing heart grows heavy: You know that even as you change, something immovable inside you will remain.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 6 | Marietta

̶ I was out hang gliding with Aravane, and—

̶ Hang gliding?

̶ Yes. There’s a photo in the study. She goes hang gliding off the Alborz mountains.

̶ Where’s that?

̶ Outside Tehran. Anyway, we’re in the air, maybe twenty meters apart. Below us, there’s the slopes, brown and barren; ahead, the sprawling city. Then, before I know it, everything disappears. I’m alone in the void. No Aravane, no city, no dry plateau—nothing but blue. I don’t panic, but I do feel anxious. Suddenly, out of this anxiety, comes a wonderful feeling of serenity. I couldn’t see the world, I understood, because the world and I were one!

̶ Hmmm…

̶ I felt euphoric—until I realized there was nowhere to land! After an instant of panic, I felt strangely elated. Nothing could hurt me, nothing could touch me—I was invulnerable! And then, just as suddenly as they had vanished, the land was back, the city was back, but Aravane, she was nowhere to be seen. I picked myself a landing spot, started my descent, and just as I touched the ground I found myself beside Aravane—in bed!

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

̶ Are you sure it was just a dream?

̶ Quite sure!

̶ The dream’s rather transparent, isn’t it?

̶ Dreams are never as simple as they seem.

You’re the sundial that tells moon-time, you’re the warrior that fights for peace; you’re the grass that grows in tarmac, you’re the black sheep with the golden fleece: So what does the dream mean?

̶ It’s like this, Sprague. Aravane’s hair is jet black, like yours. Her eyes are emerald, like yours. Her skin is the same coffee colour, and it glows like yours. She looks me in the eye the way you do; she tilts her head like you do. And she wears the same watch you wear.

̶ And when did you have this dream?

̶ The night of our first kiss, after Le Muguet.

̶ Hmmm…

̶ So you see, identity’s just a set of ruses subject to revision.

I’m a tinderbox of longing, I’m a jukebox of jive; I’m a failed suicide, I’m happy to be alive!

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

IV. DEATH OF FIRST BELOVED – MARIETTA: MARCO | MARA: ZOLI

Out on the wily, windy moors / We’d roll and fall in green / You had a temper like my jealousy / Too hot, too greedy / How could you leave me / When I needed to possess you? / I hated you, I loved you, too.

Kate Bush, ‘Wuthering Heights’, 1978

While it is Catherine, not Heathcliff, whose dies a death that leaves the lover woefully bereft and ready to be haunted (unlike in Mara, Marietta, where it is the dual heroines who, in adolescence, are left bereft), I’ve chosen Kate Bush’s lyric as an epigram here precisely because of its survivor, feminine and adolescent perspective. Indeed, in the Mara–Zoli and Marietta–Marco couples, there is something of the passionate intensity and transformative power, of the ‘rightness’ and timeliness, of Catherine and Heathcliff’s love.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 13 | Marietta

Then, one Sunday morning while Marco was riding towards Ballaigues on the Lignerolle road, a car came to a stop at the intersection near La Maladaire. As the car began turning left into the road, it cut off Marco’s passage. The motorcycle struck the car, Marco was thrown off the bike and landed on the road. He died instantly. The car driver suffered shock but no injury. The police determined that both he and the motorcycle rider had obeyed all the rules of the road. In the afternoon a taxi pulled up at your door. You opened the door to the ashen face of Marco’s father. He embraced you and then said, ‘Marco’s dead’. You went numb. He explained how it happened, then embraced you again and said, ‘Marco was never happier than when he was with you’. He then left to fly back to Rome. You collapsed onto the sofa. Pascale and your father, each in turn, took you in their arms. You couldn’t cry. You got up. You had to move. You went into the garden. You could no longer see clearly. You tried in vain to dry your eyes. You went up to your room. You couldn’t enter it: Just hours ago Marco was inside. You sat on the stairs wanting to scream. You couldn’t get a sound out of your throat.

Paul Wunderlich

In the bathroom you drank directly from the tap: You feared what you might do with a glass, were you to hold one in your hand. You didn’t dare look in the mirror. You decided to go for a walk. You put on your shoes. You no longer wanted to go for a walk. You asked for a glass of wine. Is this a nightmare? When will I wake up? The wine offered no answers. You went upstairs to your room. This time you entered it and locked the door behind you. You collapsed into your chair and stared at the bed. He appeared, sitting crossed-legged, stripped to the waist. On your tongue you could taste the salt of his skin, his dark skin whose scent of hot stone and wet linen, pine needles and green melon, moved you so. ‘Hold me’, you said to him. He just smiled at you, with that shy smile that would bring forth all your tenderness. ‘Hold me’, you said again. As he reached out, his stark beauty turned bleak; he floated, then faded away. ‘Now that you found yourself losing your mind, are you here again?’: Through your tears you saw his guitar, propped up against the wall. You heard the chords, the loping rhythm; you heard him singing ‘I Believe in You’. He’d taught you that Neil Young song just before he left to go to Vallorbe station. You realized with a shudder that he’d never come back. Your breathing faltered; you fell to the floor and let your tears flow. And then your world turned white.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Four Chapter 7 | Mara

Gasping for breath at the surface, you taste your devastation; staring into the empty sky, you feel at one with nothing. Total disbelief, utter bewilderment. In shock, dumbstruck, numb. Killed in a car crash nine months after you met, your only love is the lone fatality of the four people in the Fiat. Zoli was seventeen; you were fifteen-and-a-half. As soon as you saw him you knew he was the one. Doing street theatre on the waterfront in Maribor, you spent every spare moment together. In the hostel or on the island, on the banks of the river or in a café, like a starving child eating a stolen apple you opened your heart to his. It wasn’t long before you were thick as thieves, your faith in each other absolute. His quiet courage, his ability to surprise, the tenderness and laughter in his eyes: Never again will you meet anyone who can move you the way he did! Down your temples your tears flow, the empty sky your only consolation. Drained of all vitality, you reach into your reserves and swim to the jetty.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

V. SELF-CURE – MARIETTA: ANOREXIA | MARA: CUTTING

Every symptom is an attempt at self-cure.

Freud

For Marietta, maternal abandonment and the onset of adolescence culminate in a crisis from which anorexia offers a way out, while for Mara, cutting is a form of self-soothing for the transgenerational trauma she experiences upon the suicide of her father.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 1 | Marietta

Why can’t my body be like a boy’s, profiled for action? Why must it betray me with its loathsome blood and swelling flesh? My body is hollowing out, emptying out, unfolding; my body is scandalous! And all of it aimed at one thing: At making me—my God, never! Never! I don’t want to be a woman: I want to be myself. With this decision you begin your swim to the source, determined to be reborn in a body that belongs to you alone. And so you make yourself immune to others, you remove yourself from everything impure and begin to shed your flesh. Why should you eat? You lack nothing. It’s working! What a thrill when the scales testify to your will, what a thrill when your cross a threshold! Before long you’re flirting with death like a matador, convinced that readiness to die allows you to live: In elation you realize that your ideal weight is not thirty-five, thirty or twenty-five kilos; no, your ideal weight is zero! The joy of needing no-one and nothing, why didn’t you think of it before? Accepting neither reasoning nor coercion, neither love nor interest, you declare yourself sole judge of who you are and recognize no link to anyone. You need starvation to live, you’re in complete control—no one will take that away from you! What do they know, thinking you were trying too hard to please the opposite sex? The fools—if they only knew you were putting an end to sex itself! Why can’t they see that in your infinite nostalgia you are hungry for something else? No, it’s all or nothing. You will make no concession, you will not be reduced to servitude! No!

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Four Chapter 6 | Mara

Low over the bank of earth they ramble, fleshy, needle-like leaves, flashing clusters of tiny crimson buds on dark red bracts. Cracks and fissures run through fragments of fallen bark; from a patch of dry mud, lengths of filament stretch out. Faeringa! A shock of talons leaps out of the earth, black limbs articulate doom! From coxa to tarsus their movements mesh, until in the grapnel of the spider’s embrace the cicada is clenched. Serrated claws press into the abdomen of the insect; fangs snap out of their groove. Hail! Into the head, between the eyes, fangs sink as venom flows: Into your skin, just below the elbow, you guide the razor blade. Down through dermis and epidermis, down past the capillaries to the dominion of pain, you press the bright steel flake. Around the burning edge a shimmering bead wells up; down the whiteness of your forearm you draw the mesmerizing red. Lifting open a secret trapdoor, the spider enters its burrow; as blood flows in rivulets across your skin, the predator descends with its prey. I stare into the tumult in your eyes; you bring your fingers to my lips. How do we measure the distance between God and man? Twenty-two finger-breadths make the universe: The cubit of your forearm bridges heaven and earth.

Karin Székessy (photo) | Paul Wunderlich (artwork)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments