Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol, Ten Lizes, 1963

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 5

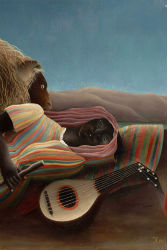

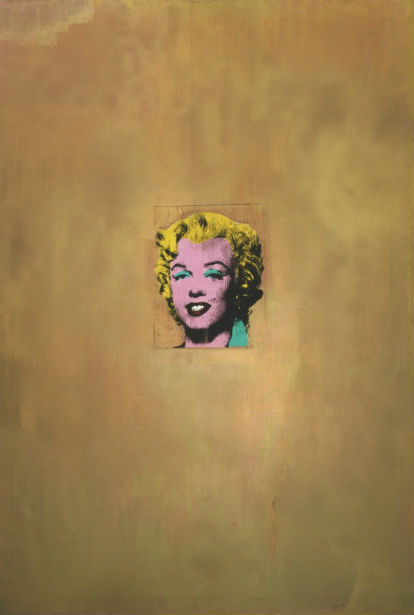

On the floor, in a corner by a cabinet, dry reeds in a jar of smoked ginger compose a still life. The shadow of the reeds on the wall leads to a garish Warhol: Marilyn. I imagine her in the cast-iron clawfoot bathtub, soaping a raised leg; I imagine her leaning against the sloping rear, its curves harmonizing with hers.

Lost in thought in a cone of incandescence, you sit in your panties on the vanity counter, picking at your split ends. The medicine cabinet, through the frosted glass of its diamond-grid door, emits a glow that sculpts the contour of your shoulder. Legs crossed, head lowered, in a hand-over-hand movement you isolate a sheaf of hair and twirl it around your finger; as the ends pop out of the twist, you lean back into the light and inspect them dreamily.

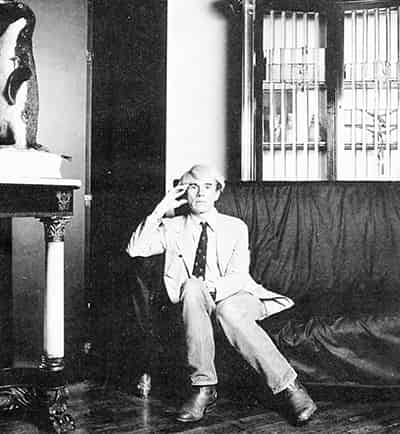

Andy Warhol, 1964 | Photo: Billy Name

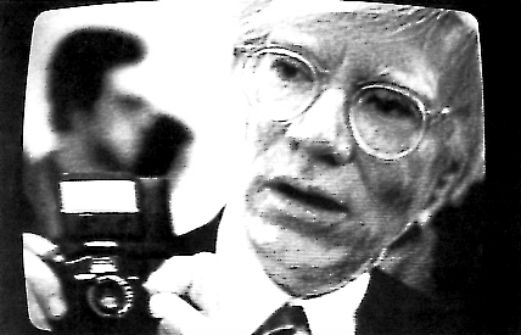

Andy Warhol, 1981 | Photo: Marcus Leatherdale

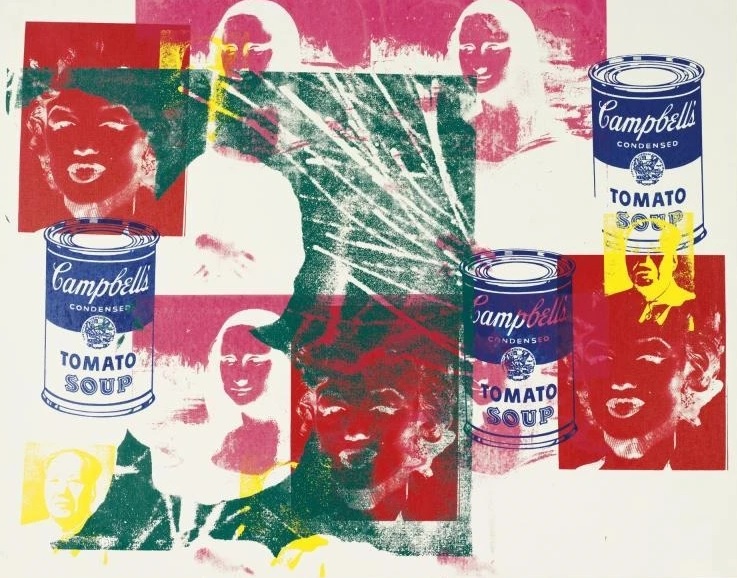

̶ It’s tiring, Sprague, always being shadowed by your own image. That’s why I like Warhol: He out-objectifies the object itself, draining it of any trace of sentimentality. I like the way he conveys the obscene: so ascetic, so ironic.

̶ Yes.

̶ As soon as I became a teenager I had to learn a foreign language, the language Marilyn had mastered.

̶ Femininity?

̶ Yes.

You look up from your hair.

̶ Pass me the scissors—they should be in the drawer of the cabinet you’re sitting on.

Snip, snip, snip: Into the trash bin the trimmed hairs drop.

̶ I feel completely out of step with how people see me. It has nothing to do with how I perceive myself.

Pale gold against pearl white, your tresses swing off your breasts to create a veil of modesty; left hand, right hand, left, you isolate a sheaf of hair, find a split end and rip it apart.

̶ It’s alienating, being reduced to one dimension.

̶ I never realized—

̶ ‘Cause you’re not a woman! Even if you are beautiful.

Gentle it comes, your smile. Left hand, right hand, left: You return to inspecting your hair.

̶ Have you ever felt like a mannequin in a shop window, Sprague?

̶ No.

̶ I have. That’s why I love Warhol. He shows what it’s like to feel like a mannequin—or a Christmas tree!—in a department store.

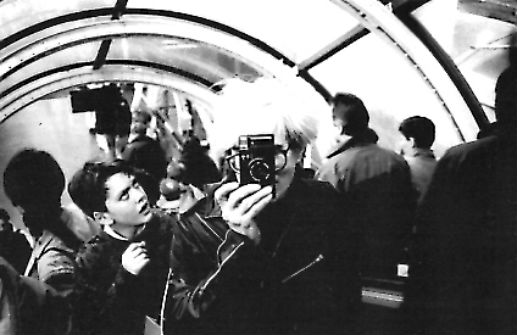

Andy Warhol shortly before his death | Christopher Makos, 1987

Andy Warhol at the Centre Pompidou | Christopher Makos, 1986

Behind the implacable symmetry of its diamond-grid door, the medicine cabinet calmly diffuses its frosted light. Cross-eyed, you zoom in on a split end: Your steely gaze turns rapturous as you rip the strand apart.

̶ I like that arid coolness he had, the coldness of his regard. He was the master of insignificance. He’d often say his ideal was to be a machine.

Over, under, over: Weaving your hair through the loom of your fingers, you shuttle down the sheaf, snipping off the split ends as they pop out.

̶ I like the honesty of that, his lack of faith in art. It’s very refreshing.

From the hollow of your clavicle you draw a golden curl. Search and destroy! Deft in their dirty work, your fingers rip the split end apart. On the vanity you float away, glazed eyes aglow.

JEAN BAUDRILLARD ON ANDY WARHOL

Absolute Merchandise

Translated from the French by David Britt

This text was originally published in French in Artstudio, No. 8, Spécial Andy Warhol, Spring 1988.

From Andy Warhol: Paintings 1960-1986, Martin Schwander, editor (Stuttgart: Verlag Gert Hatje, 1995)

(Exhibition Catalogue, Kunstmuseum Luzern | Exhibition: 9 Jul–24 Sep 1995)

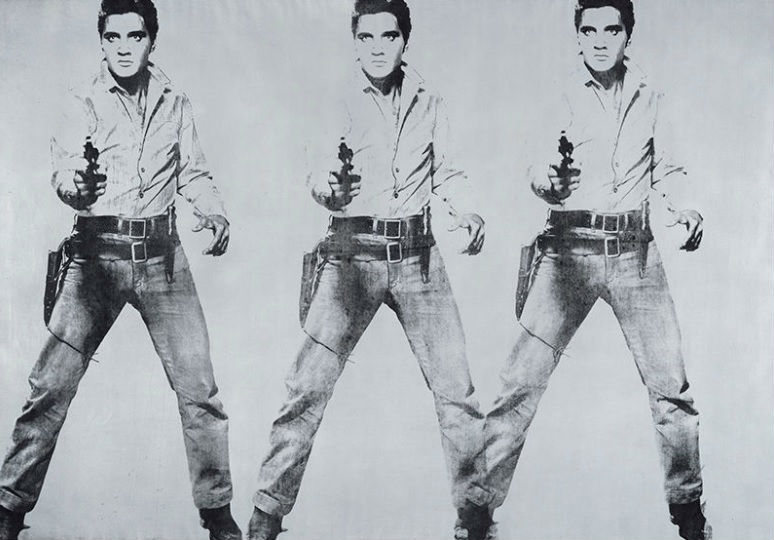

Andy Warhol, Triple Elvis, 1964

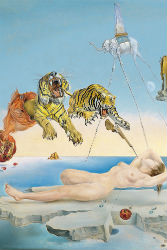

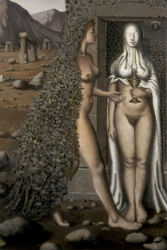

In the tradition initiated by Hegel—when he spoke of the ‘rage to disappear’ and proclaimed that art was henceforth caught up in the process of its own disappearance—a direct line runs between Charles Baudelaire and Andy Warhol; its theme is that of ‘absolute merchandise’. In the great confrontation between the artwork concept and modern industrialized society, it was Baudelaire, right from the start, who hit upon the radical solution. He faced the threat posed to art by a commercial, vulgar, capitalist, advertising society—the unprecedented threat that mercantile value would reduce the work of art to the status of a mere object—and countered it, not by defending art’s traditional status but by totally objectifying art. Where aesthetic value is in danger of being alienated by mercantile value, it is no use putting up a defence against alienation: alienate all the way, and fight alienation with its own weapons. Relentlessly pursue the indifference and equivalence of mercantile value; turn the work of art into absolute merchandise.

Faced with the modern challenge of merchandise, art can find no salvation in a critical posture of denial (which would reduce it to ‘art for art’s sake’, risibly and ineffectually holding up a mirror to capitalism and the inexorable advance of commerce). Its salvation lies in taking to extremes the formal, fetishistic abstraction of merchandise, the magical glamour of exchange value. Art must become more mercantile than merchandise itself: more remote from use value than ever before, art must take exchange value to extremes and thus transcend it.

Any Warhol, Self-Portrait, 1962

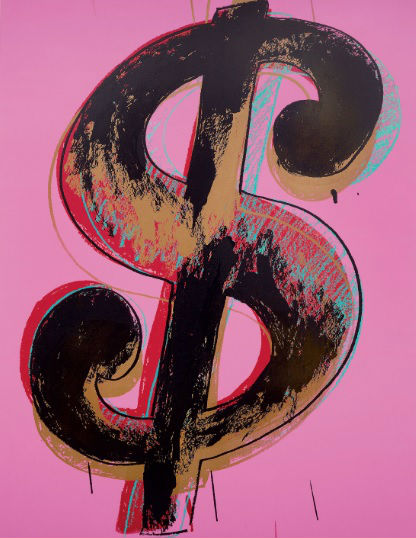

Andy Warhol, Dollar Sign, 1981

The absolute object is the object whose value is zero, whose quality is indifferent, but which escapes from alienation and acquires a fatal inevitability by out-objectifying the object itself. This bypassing of exchange value—this destruction of the mercantile by its own value—can be seen in the inflation of the art market: all that insensate speculation in works of art is itself a parody of mercantile forces, a mockery of market value. All the laws of equivalence are overturned, and we leave behind the realm of value to enter the realm of a phantasm of absolute value: we are in value ecstasy. Aesthetically, as well as economically, we are in value ecstasy: all aesthetic values (those of style, manner, abstraction versus figuration, neo-this, revival of that) are simultaneously and exponentially maximized. By a special dispensation, all can go straight onto the hit parade, and it is impossible to compare them or to revive any form of value judgment whatever. We are in a jungle, where objects turn into fetishes; and a fetish, as we know, is an object that has no value in itself—or rather, it has so much value that it can no longer be exchanged.

This is the point we have reached in present-day art. And this is the eminent irony that Baudelaire wanted to see manifested in art. Art has become a form of merchandise that is eminently ironic, because it no longer means anything; it is more arbitrary and irrational even than merchandise itself, and therefore circulates even more rapidly and gains value in direct proportion to its loss of meaning and referentiality. Ultimately, beneath the triumphant banner of modernity, Baudelaire came close to identifying art with fashion: fashion as the apotheosis of merchandise, and therefore as a radical parody and a radical denial of merchandise itself.

When the art object takes on the form of merchandise, it loses its a priori ideal nature (beauty, authenticity, even functionality); and we must not try to revive that ideal by negating the merchandise form itself. On the contrary—and this is the whole strategy of modernity as Baudelaire saw it, the perverse and perilous seductive power of the modern world—we must take the dichotomy of values to its absolute extreme. No dialectic between the two: synthesis is a soft option, dialectic a nostalgic option. The one and only radical and modern option is to potentiate all that is new, original, unexpected, inspired, in the merchandise object: that is, its formal indifference both to utility and to value. Circulation is all. The work of art must acquire all the qualities of shock, strangeness, surprise, unease, liquidity—even self-destruction, instantaneity and unreality—that pertain to merchandise.

Andy Warhol, Gold Marilyn Monroe, 1962

Andy Warhol, Brillo Box, 1964

It must carry the inhumanity of exchange value to an exponential, ecstatic extreme—which is also an ironic comment on the value-free processes of alienation. This is why, in the magical, ironical (but also non-dialectical) logic of Baudelaire, the work of art aligns itself absolutely with fashion, with advertising and with all the ‘magic of the code’. It becomes a work of dazzling venality and mobility, its effects dizzily unpredictable—a miraculously protean, pure object. There are no more causes, and all effects are virtually equivalent.

Those effects can also be void, as we well know; it is for the work of art to fetishize that void, that disappearance, and to draw extraordinary effects from it. This is a seductive power of a new kind, which no longer consists in the mastery of conventional effects, of illusion and aesthetic order, but in the dizzying impact of the obscene. But, then, who is to say where the difference lies? Common merchandise yields only a world of production, and God knows how melancholy that world is. Merchandise acquires seductive power when it becomes absolute.

As a new and triumphant fetish (and not a sad, alienated fetish), the art object must work to deconstruct its own traditional aura, its authority and its power of creating illusion, so that it is left resplendent in the pure obscenity of being merchandise. It must abrogate itself as a familiar object and become something monstrously strange. But this strangeness is no longer that of the repressed or alienated object. The object glows, not with some secret obsession or dispossession, but with a true seductive power derived from outside itself: it glows because it has transcended its own form to become a pure object, a pure event.

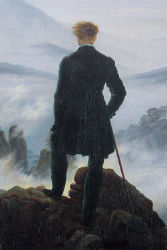

This insight of Baudelaire’s—prompted by the spectacle of the transfiguration of merchandise at the Universal Exposition of 1855—is superior in many respects to that of Walter Benjamin. In ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technical Reproducibility’, Benjamin shows that the art object loses its aura and its authenticity in the age of reproduction, and from this he draws a desperately political (i.e. politically desperate) conclusion, which turns modernity into a melancholy prospect indeed. Baudelaire takes the infinitely more modern option—but then, perhaps in the nineteenth century you really could be modern—of exploring new forms of seductive power that are linked to pure objects, to pure events, and to the modern passion that we call fascination.

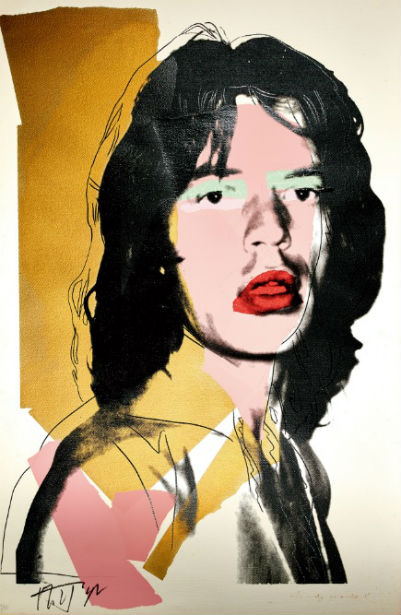

Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger, 1975

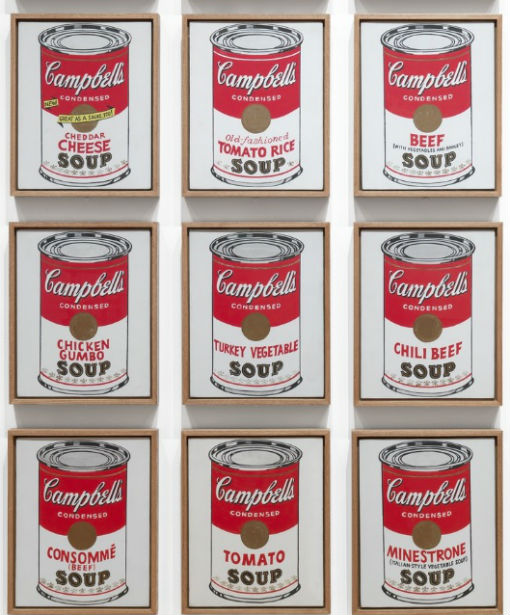

Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Cans, 1962 (detail)

Benjamin saw the aura as something unique to the authentic original; but the simulacrum or simulation can perfectly well have an aura of its own. I am tempted to say that simulation can be authentic or unauthentic. Paradoxical though it may seem, there are such things as ‘true’ and ‘false’ simulation. When Warhol painted his Campbell’s Soup Cans in the 1960s, this was a sensational coup, both for simulation and for modern art. At a stroke, the merchandise object or the merchandise sign was consecrated by the only ritual we have left: that of transparency. But by the time he came to paint the Soup Cans in 1986, the simulation was no longer sensational but stereotypical. In 1965 Warhol was attacking the concept of originality in an original way; in 1986 he was reproducing the unoriginal in an unoriginal way. In 1965 the whole aesthetic trauma of the invasion of art by merchandise was conveyed in a way both ascetic and ironic (the asceticism of merchandise, simultaneously puritanical and magically enigmatic, as Marx said). The practice of art was simplified at a stroke. The genius of merchandise, its Cartesian demon, invoked a fresh demon in art—the genius of simulation. By 1986 none of this remained: the genius of promotion presided over a new phase of merchandising. Official art returned to cast its aesthetic spell over merchandise, and we were back with the sentimental aestheticism that Baudelaire condemned.

You may say that it is still more eminently ironic to do the same thing all over again twenty years later. I don’t think so. I believe in the genius of simulation, but not in its ghost. Nor in its corpse, even in stereo. I know that in a few centuries’ time there will be no difference between a real Pompeian villa and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, or between the French Revolution and its Olympic commemoration in Los Angeles in 1989: but we still live by that difference, and we draw our energy from that difference. I don’t deny that there may be a dizzying thrill in total indifference, the total confusion of forms and their doubles; but for the time being we cannot help telling the difference.

Andy Warhol, Multi-Colored Retrospective, 1979

Andy Warhol, Silver Liz, 1963

When Andy Warhol insists on becoming a total ‘machine’—more mechanical even than a machine, since he aims at the automatic, mechanical production of objects that are mechanical and manufactured already, whether they be soup cans or portraits of movie stars—then he stands in direct line of succession to Baudelaire’s ‘absolute merchandise’. Warhol is simply carrying through Baudelaire’s vision, which is also the destiny of modern art, even when Warhol denies it: to act out to the utmost—to the point of self-negation—the ecstasy of negative value, which is also the ecstasy of negative representation. And when Baudelaire says that it is the modern artist’s vocation to endow merchandise with heroic stature—whereas the bourgeoisie, in advertising that merchandise, can do no more than give it sentimental expression—he is saying that heroic stature lies not in resanctifying art and value as against merchandise (an impulse which is sentimental, and which still powers much of our own art to this day), but in sanctifying art as merchandise. Warhol is thus the hero or anti-hero of modern art, because he goes farthest with the ritualized disappearance of art, and of all sentimentality from art; he goes farthest with the ritualized, negative transparency of art, its utter indifference to its own authenticity. The modern hero is no longer the hero of the artistic sublime: he is the hero of the objective irony of the merchandise world, as embodied by art in the objective irony of its own disappearance.

That disappearance is not negative or depressing, any more than merchandise as such is. Viewed in the spirit of Baudelaire, it is a cause for enthusiasm: there is a modern magic in merchandise, and a parallel magic in the disappearance of art. But, of course, there is a right and a wrong way to disappear. Art’s disappearance—that is, its modernity—consists in the art of disappearing. And the whole difference between the triumphalist ‘pompier’ art of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—official art, art for art’s sake etc., the art which knows no boundaries and can range from the figurative to the abstract or to any other category whatever; the art which was born in Baudelaire’s time, which he so loathed, and which is far from dead yet, since it is now being triumphantly rehabilitated in the international museums—the whole difference between that art and the other lies in this secret abnegation (abnegation being a heroic virtue): the way in which authentic art almost involuntarily, almost unconsciously, opts for its own disappearance.

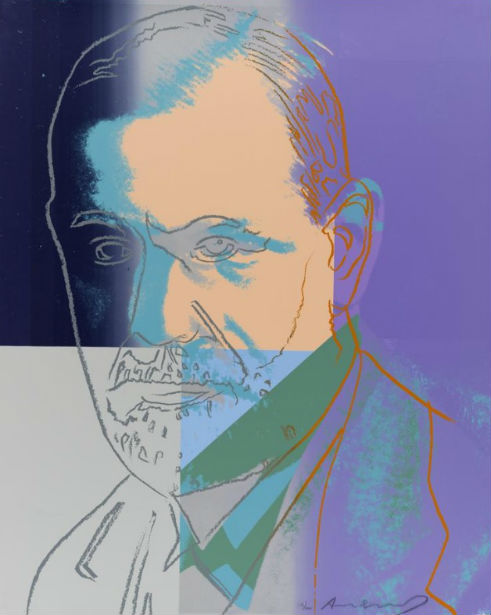

Andy Warhol, Sigmund Freud, 1980

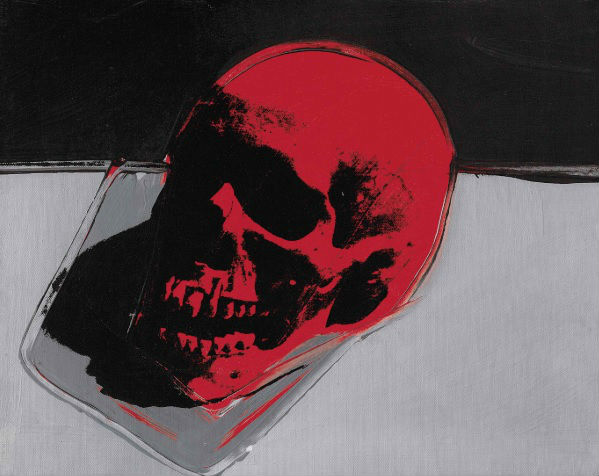

Andy Warhol, Skull, 1976

Official art does not want to disappear. It does not act out its own disappearance. And that is precisely why it disappeared from our minds for a century. Its triumphant reappearance today, in the postmodern age, signifies that the great modernist adventure, that of the disappearance of art, is over.

In Warhol, the choice is acted out consciously, almost too consciously, too cynically; it is none the less a heroic choice.

Andy Warhol and His Dog Archie, 1973

Andy Warhol paints the Statue of Liberty in Paris, 1986

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

Andy Warhol: Giant Size, Phaidon

Arthur Danto, Andy Warhol, Yale U Press

Andy Warhol (right) imitating Truman Capote (left)

Photo of AW: Duane Michaels, 1949

Andy Warhol, Truman Capote, 1979

From Andy Warhol: 1928-1987, ed. Jacob Baal-Teshuva (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1993)