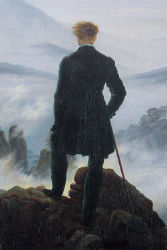

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh, Dr. Paul Gachet, 1890

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Two Chapter 10

Dear Tilda,

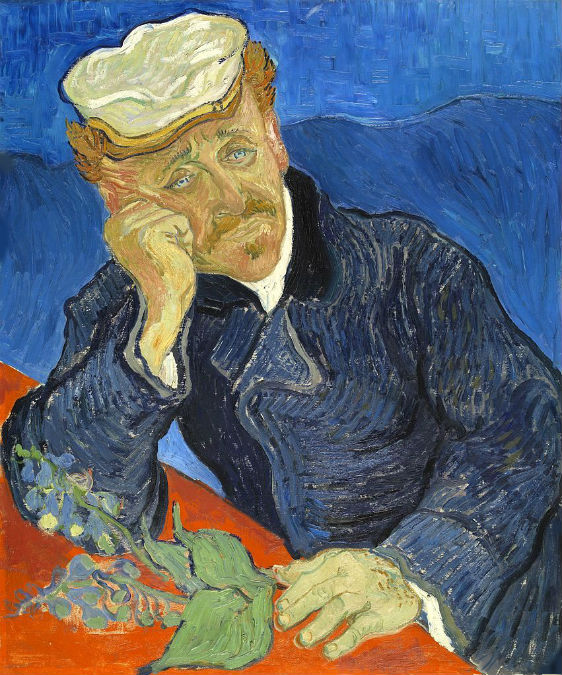

On 23 March 1890, in Auvers-sur-Oise, Doctor Paul Gachet received a letter from Theo van Gogh asking whether he would be willing to look after Theo’s brother, Vincent, who’d been suffering from nervous complaints. The doctor was willing, and Vincent ended up spending the last months of his life in Gachet’s care.

One day, after taking his midday meal at the inn where he was staying, he went out into the fields and shot himself. The bullet entered his body just below the heart. He bled profusely, but managed to get back to the inn by nightfall.

Gachet and a second doctor who saw him determined that the bullet was inaccessible and that Vincent’s life could not be saved. Theo was called to his brother’s bedside. Going against the doctors’ pessimism, he urged them to encourage Vincent to hold out. But Vincent would invariably reply, ‘There’s no point. The sadness will last all my life’.

Two days later, at one-thirty in the morning, he died.

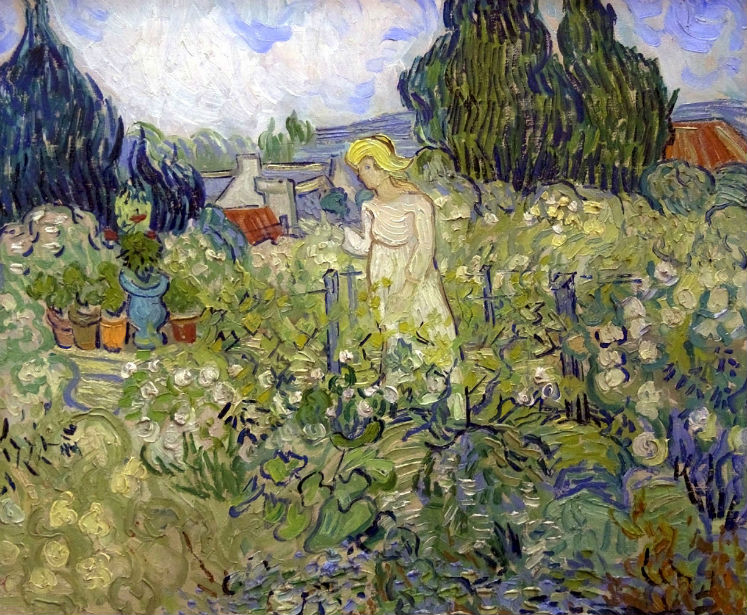

Marguerite, Gachet’s daughter—whose kindness had touched Vincent during these last months of his life—said of him, ‘His life was one moment of weakness after another, but in the end, what strength!’.

I’m no Vincent, Tilda, but on a night like this, when you are so near and yet so far, I console myself with the hope that one day you will see my moments of weakness redeemed by an ultimate strength.

And I say this despite the certainty lodged in my soul, the certainty that you too hold, that for me ‘the sadness will last all my life’.

Sprague

Vincent van Gogh, Marguerite Gachet in the Garden, 1890

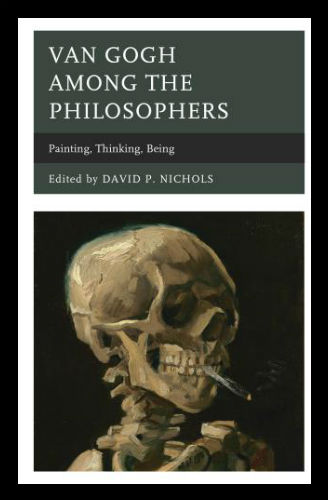

VINCENT VAN GOGH IN THE EYES OF FREDERIC JAMESON

Van Gogh / Warhol

From Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991) pp. 8-10

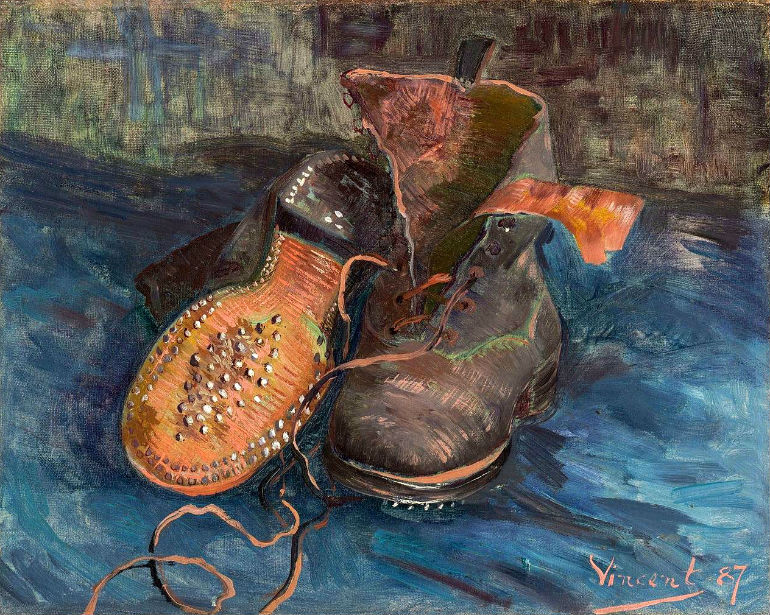

Vincent van Gogh, Pair of Shoes, 1887

Van Gogh’s well-known painting of the peasant shoes is one of the canonical works of high modernism in visual art. I want to propose two ways of reading this painting, both of which in some fashion reconstruct the reception of the work in a two-stage or double-level process.

I first want to suggest that if this copiously reproduced image is not to sink to the level of sheer decoration, it requires us to reconstruct some initial situation out of which the finished work emerges. Unless that situation—which has vanished into the past—is somehow mentally restored, the painting will remain an inert object, a reified end product impossible to grasp as a symbolic act in its own right, as praxis and as production.

‘Production’ suggests that one way of reconstructing the initial situation to which the work is somehow a response is by stressing the raw materials, the initial content, which it confronts and reworks, transforms, and appropriates. In Van Gogh that content, those initial raw materials, are, I will suggest, to be grasped simply as the whole object world of agricultural misery, of stark rural poverty, and the whole rudimentary human world of backbreaking peasant toil, a world reduced to its most brutal and menaced, primitive and marginalized state.

Fruit trees in this world are ancient and exhausted sticks coming out of poor soil; the people of the village are worn down to their skulls, caricatures of some ultimate grotesque typology of basic human feature types. How is it, then, that in Van Gogh such things as apple trees explode into a hallucinatory surface of color, while his village stereotypes are suddenly and garishly overlaid with hues of red and green? I will briefly suggest, in this first interpretative option, that the willed and violent transformation of a drab peasant object world into the most glorious materialization of pure color in oil paint is to be seen as a Utopian gesture, an act of compensation which ends up producing a whole new Utopian realm of the senses, or at least of that supreme sense—sight, the visual, the eye—which it now reconstitutes for us as a semi-autonomous space in its own right, a part of some new division of labor in the body of capital, some new fragmentation of the emergent sensorium which replicates the specializations and divisions of capitalist life at the same time that it seeks in precisely such fragmentation a desperate Utopian compensation for them.

Vincent van Gogh, Pollard Willow with Setting Sun, 1888

Vincent van Gogh, Pair of Shoes, 1886

There is, to be sure, a second reading of Van Gogh which can hardly be ignored when we gaze at this particular painting, and that is Heidegger’s central analysis in The Origin of the Work of Art, which is organized around the idea that the work of art emerges within the gap between Earth and World, or what I would prefer to translate as the meaningless materiality of the body and nature and the meaning endowment of history and of the social. Recall some of the famous phrases that model the process whereby these henceforth illustrious peasant shoes slowly re-create about themselves the whole missing object world which was once their lived context. ‘In them,’ says Heidegger, ‘there vibrates the silent call of the earth, its quiet gift of ripening corn and its enigmatic self-refusal in the fallow desolation of the wintry field.’

He goes on: ‘This equipment belongs to the earth, and it is protected in the world of the peasant woman. Van Gogh’s painting is the disclosure of what the equipment, the pair of peasant shoes, is in truth. This entity emerges into the unconcealment of its being,’ by way of the mediation of the work of art, which draws the whole absent world and earth into revelation around itself, along with the heavy tread of the peasant woman, the loneliness of the field path, the hut in the clearing, the worn and broken instruments of labor in the furrows and at the hearth. Heidegger’s account needs to be completed by insistence on the renewed materiality of the work, on the transformation of one form of materiality—the earth itself and its paths and physical objects—into that other materiality of oil paint affirmed and foregrounded in its own right and for its own visual pleasures, but nonetheless the account has a satisfying plausibility.

Vincent van Gogh, Pair of Shoes, 1887

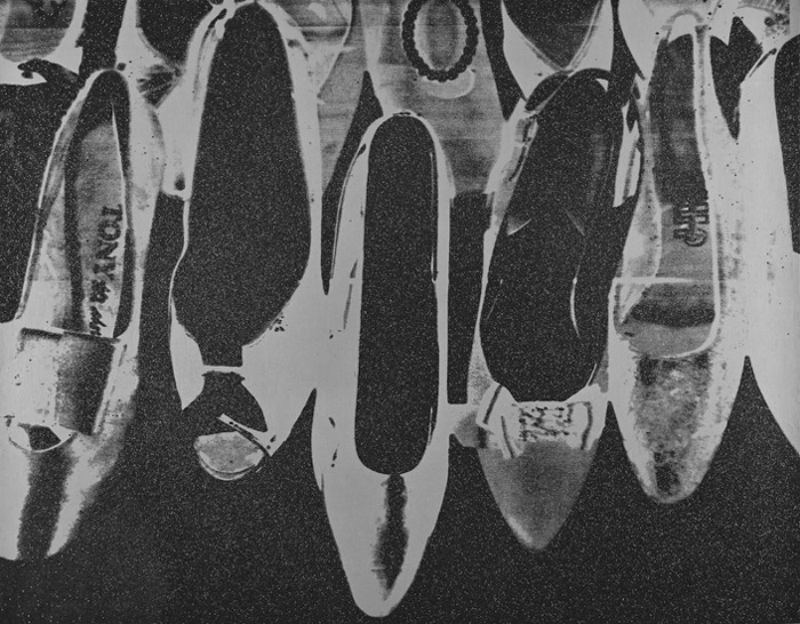

Andy Warhol, Diamond Dust Shoes, 1980

At any rate, both readings may be described as hermeneutical, in the sense in which the work in its inert, objectal form is taken as a clue or a symptom for some vaster reality which replaces it as its ultimate truth. Now we need to look at some shoes of a different kind, and it is pleasant to be able to draw for such an image on the recent work of the central figure in contemporary visual art. Andy Warhol’s Diamond Dust Shoes evidently no longer speaks to us with any of the immediacy of Van Gogh’s footgear; indeed, I am tempted to say that it does not really speak to us at all. Nothing in this painting organizes even a minimal place for the viewer, who confronts it at the turning of a museum corridor or gallery with all the contingency of some inexplicable natural object. On the level of the content, we have to do with what are now far more clearly fetishes, in both the Freudian and the Marxian senses. Here, however, we have a random collection of dead objects hanging together on the canvas like so many turnips, as shorn of their earlier life world as the pile of shoes left over from Auschwitz or the remainders and tokens of some incomprehensible and tragic fire in a packed dance hall.

There is therefore in Warhol no way to complete the hermeneutic gesture and restore to these oddments that whole larger lived context of the dance hall or the ball, the world of jet set fashion or glamour magazines. Yet this is even more paradoxical in the tight of biographical information: Warhol began his artistic career as a commercial illustrator for shoe fashions and a designer of display windows in which various pumps and slippers figured prominently. Indeed, one is tempted to raise here one of the central issues about postmodernism itself and its possible political dimensions: Andy Warhol’s work in fact turns centrally around commodification, and the great billboard images of the Coca-Cola bottle or the Campbell’s soup can, which explicitly foreground the commodity fetishism of a transition to late capital, ought to be powerful and critical political statements. If they are not that, then one would surely want to know why, and one would want to begin to wonder a little more seriously about the possibilities of political or critical art in the postmodern period of late capital.

Andy Warhol, Diamond Dust Shoes, 1980

Andy Warhol, Diamond Dust Shoes, 1980

But there are some other significant differences between the high-modernist and the postmodernist moment, between the shoes of Van Gogh and the shoes of Andy Warhol, on which we must now very briefly dwell.

The first and most evident is the emergence of a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality in the most literal sense, perhaps the supreme formal feature of all the postmodernisms.

The second feature is the role of photography and the photographic negative in contemporary art of this kind; and it is this, indeed, which confers its deathly quality to the Warhol image, whose glacé X-ray elegance mortifies the reified eye of the viewer in a way that would seem to have nothing to do with death or the death obsession or the death anxiety on the level of content. It is indeed as though we had here to do with the inversion of Van Gogh’s Utopian gesture: in the earlier work a stricken world is by some Nietzschean fiat and act of the will transformed into the stridency of Utopian color. Here, on the contrary, it is as though the external and colored surface of things—debased and contaminated in advance by their assimilation to glossy advertising images—has been stripped away to reveal the deathly black-and-white substratum of the photographic negative which subtends them. Although this kind of death of the world of appearance becomes thematized in certain of Warhol’s pieces, most notably the traffic accidents or the electric chair series, this is not, I think, a matter of content any longer but of some more fundamental mutation both in the object world itself—now become a set of texts or simulacra—and in the disposition of the subject.

Andy Warhol, Diamond Dust Shoes, 1980

Andy Warhol, Diamond Dust Shoes, 1980

The third feature is what I will call the waning of affect in postmodern culture. Of course, it would be inaccurate to suggest that all affect, all feeling or emotion, all subjectivity, has vanished from the newer image. Indeed, there is a kind of return of the repressed in Diamond Dust Shoes, a strange, compensatory decorative exhilaration, explicitly designated by the title itself, which is, of course, the glitter of gold dust, the spangling of gilt sand that seals the surface of the painting and yet continues to glint at us. Think, however, of Rimbaud’s magical flowers ‘that look back at you,’ or of the august premonitory eye flashes of Rilke’s archaic Greek torso which warn the bourgeois subject to change his life; nothing of that sort here in the gratuitous frivolity of this final decorative overlay.

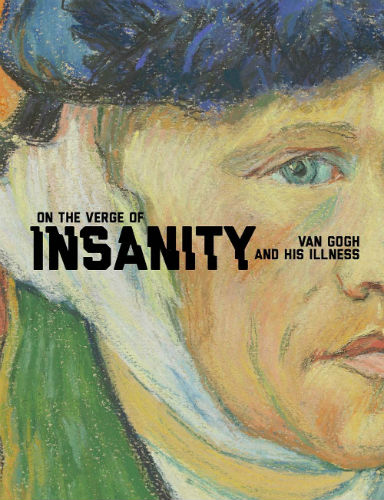

VINCENT VAN GOGH IN THE EYES OF HAROLD P. BLUM

Fantasies of Replacement: Being a Double and a Twin

From Harold P. Blum, ‘Van Gogh’s Fantasies of Replacement: Being a Double and a Twin’. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, January 2010.

Van Gogh had a confused double identity as a re-created, creative replacement, and as a ghost of himself and his deceased brother. The double represented triumph over loss and death, but was also a menacing harbinger of death. Theo joined Vincent in living out the parental shared fantasy of a twinship, a double, and eerily soon joined his brother in death. (Theo’s death has now been attributed to tertiary syphilis. His body was moved by his widow to Auvers, France, where the brothers are buried beside each other.)

Van Gogh experienced an acute psychotic episode shortly after learning of the pregnancy of Theo’s wife. He committed suicide in July 1890, six months after this new Vincent van Gogh’s birth. The replacement child was replaced by “Vincent van Gogh,” and this repetition contributed to his final psychological decompensation. With a despondent sense of failure as an artist, and anticipating Theo’s loss, van Gogh succumbed to depressive hopelessness. He had taken refuge in paintings of fantasized merger with Mother Earth, his namesake in the earth, and his idealized narcissistic objects in the heavenly blue sky. “We take death to reach a star, we cannot reach a star while we are alive” (letter to Theo, August 3, 1888). His suicide enacted the fantasy of merger, as well as murderous aggression against himself and his object world.

Diane Arbus, Identical Twins, Roselle, N.J. 1967

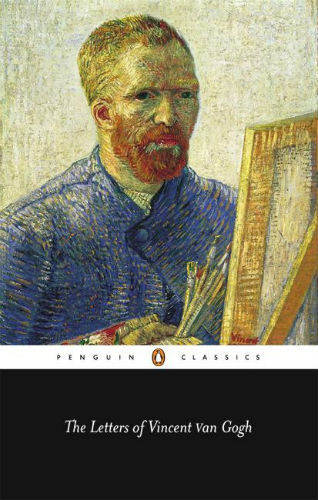

VINCENT VAN GOGH IN THE EYES OF ANTONIN ARTAUD

Suicided by Society

From Antonin Artaud: Selected Writings, edited and with an Introduction by Susan Sontag (University of California Press, 1988) pp. 489-90 (written in 1947).

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield with Crows, 1890

Vincent van Gogh, Wheatfield, 1888

These crows painted two days before his death did not, any more than his other paintings, open the door for him to a certain posthumous glory, but they do open to painterly painting, or rather to unpainted nature, the secret door to a possible beyond, to a possible permanent reality, through the door opened by van Gogh to an enigmatic and sinister beyond.

It is not usual to see a man, with the shot that killed him already in his belly, crowding black crows onto a canvas, and under them a kind of meadow—perhaps livid, at any rate empty—in which the wine color of the earth is juxtaposed wildly with the dirty yellow of the wheat.

But no other painter besides van Gogh would have known how to find, as he did, in order to paint his crows, that truffle black, that ‘rich banquet’ black which is at the same time, as it were, excremental, of the wings of the crows surprised in the fading gleam of evening.

And what does the earth complain of down there under the wings of those auspicious crows, auspicious, no doubt, for van Gogh alone, and on the other hand, sumptuous augury of an evil which can no longer touch him?

For no one until then had turned the earth into that dirty linen twisted with wine and wet blood.

The sky in the painting is very low, bruised, violet, like the lower edges of lightning. The strange shadowy fringe of the void rising after the flash. Van Gogh loosed his crows like the black microbes of his suicide’s spleen a few centimeters from the top and as if from the bottom of the canvas, following the black slash of that line where the beating of their rich plumage adds to the swirling of the terrestrial storm the heavy menace of a suffocation from above.

And yet the whole painting is rich. Rich, sumptuous, and calm. Worthy accompaniment to the death of the man who during his life set so many drunken suns whirling over so many unruly haystacks and who, desperate, with a bullet in his belly, had no choice but to flood a landscape with blood and wine, to drench the earth with a final emulsion, both dark and joyous, with a taste of bitter wine and spoiled vinegar.

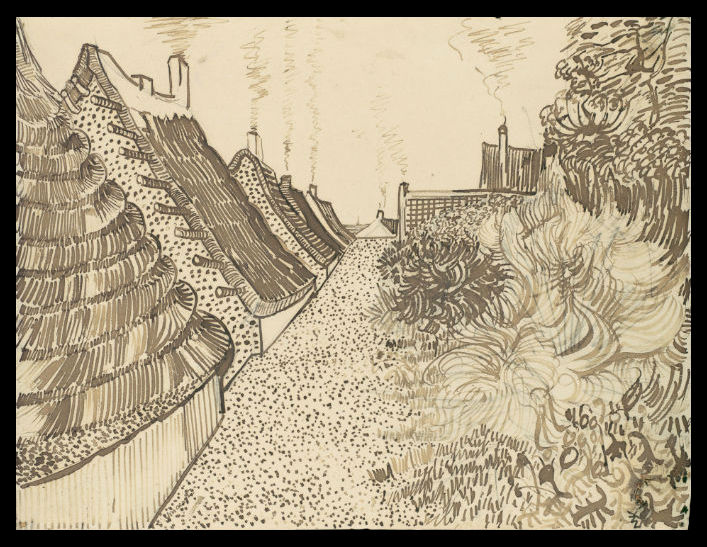

Vincent van Gogh, Street in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, 1888

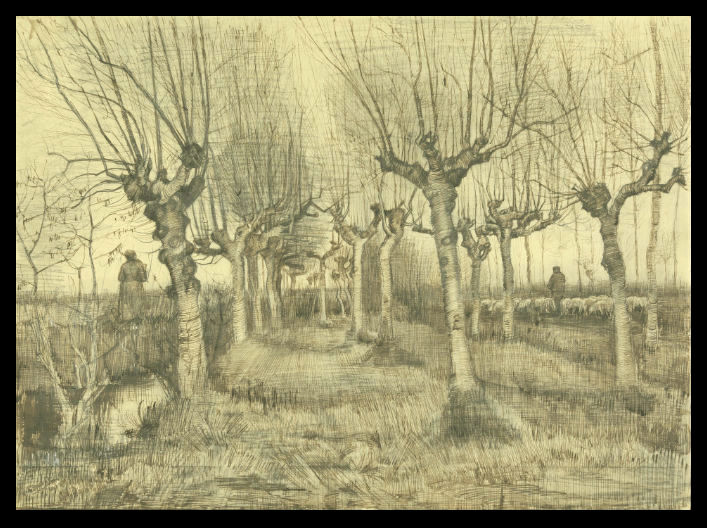

Vincent van Gogh, Pollard Birches, 1884

And so the tone of the last canvas painted by van Gogh—he who, elsewhere, never went beyond painting—evokes the abrupt and barbarous tonal quality of the most moving, passionate, and impassioned Elizabethan drama.

This is what strikes me most of all in van Gogh, the most painterly of all painters, and who, without going any further than what is called and is painting, without going beyond the tube, the brush, the framing of the subject and of the canvas to resort to anecdote, narrative, drama, picturesque action, or to the intrinsic beauty of subject or object, was able to imbue nature and objects with so much passion that not one of the fabulous tales of Edgar Allan Poe, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Gérard de Nerval, Achim von Arnim, or Hoffmann says more on a psychological and dramatic level than his unpretentious canvases, his canvases which are almost all, in fact, and as if deliberately, of modest dimensions.

In French: Visite virtuelle : Van Gogh / Artaud au Musée d’Orsay.

VINCENT VAN GOGH IN THE EYES OF GEORGES BATAILLE

I Am the Sun

By Eric Michaud

Excerpted from Eric Michaud, ‘Van Gogh, or The Insufficiency of Sacrifice’, October, Vol. 49 (Summer, 1989), pp. 25-39. The full article is availabe on JSTOR.

My intention here is not to reinscribe Van Gogh’s automutilation within the economy of sacrifice as elaborated by Bataille. I want only to try to inflect his analysis by means of Van Gogh’s famous letters to his brother Theo, wherein the painter little by little discovered, with a deep horror, the destructive effects that are attached to artistic activity.

But what exactly does Bataille say? Very simply, first, that ‘Van Gogh’s life was dominated by the overwhelming relations he maintained with the sun’; that his ‘sun paintings only become intelligible when they are seen as the very expression of the personality (or, as some would say, of the sickness) of the painter’; that although these ‘sun paintings’ appear fairly early on within his production, for the most part they postdate that Christmas night of 1888. That night, the tension with Gauguin—who had come to stay with him and to paint at Arles—having reached an extreme pitch, Van Gogh severed his left ear (or rather the lobe of the ear), wrapped it, all bloody, in a newspaper, and sent this package to the prostitute Rachel in the brothel he frequented on the rue du Bout-d’Arles.

Vincent van Gogh, Four Withered Sunflowers, 1887

Vincent van Gogh, Still Life with Sunflowers, 1889

Bataille observed that ‘in order to show the importance and the development of Van Gogh’s obsession, suns must be linked with sunflowers, whose large disks haloed with short petals recall the disk of the sun, at which they ceaselessly and fixedly stare throughout the day’.

In this way he quickly succeeds in revealing a ‘double bond uniting the sun-star, the sun-flower, and Van Gogh,’ a double bond which he characterizes as ‘a normal psychological theme in which the star is opposed to the withered flower, as are the ideal term and the real term of the ego’. One expects what Bataille, having so strongly marked this double bond or double identification between painter and sun and painter and sunflower, will enlist here in the way of that functional ambivalence that Freud had recognized in all identification. And this all the more so in that he underlines how, in Van Gogh’s very painting, the ego ideal and the real ego sometimes exchange their characters: ‘The sun in its glory is doubtless opposed to the faded sunflower, but no matter how dead ‘it may be this sunflower is also a sun, and the sun is in some way deleterious and sick: it is sulphur-colored [il a la couleur du soufre], the painter himself writes twice in French’.

But it’s less this ambivalence that engages Bataille than the heroic perspective which he will state in his ‘Sacrifices’ of 1936: the ‘heroic form of the me’ is that which, through the revelation that ‘life’s avidity for death’ is ‘pure avidness to be me,’ this me identifies itself with ‘the god that dies’. And in 1930 he writes: The relations between this painter (identifying himself successively with fragile candles and with sometimes fresh, sometimes faded sunflowers) and an ideal, of which the sun is the most dazzling form, appear to be analogous to those that men maintained at one time with their gods, at least so long as these gods stupefied them; mutilation normally intervened in these relations as sacrifice: it would represent the desire to resemble perfectly an ideal term, generally characterized in mythology as a solar god who tears and rips out his own organs.

This enlistment of Van Gogh in the great heroic lineage of the West, certainly understandable on the part of the author of ‘The Solar Anus,’ the one who would write ‘I AM THE SUN’, such an enlistment is soon reinforced by the pure and simple identification of Van Gogh with Prometheus.

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1887