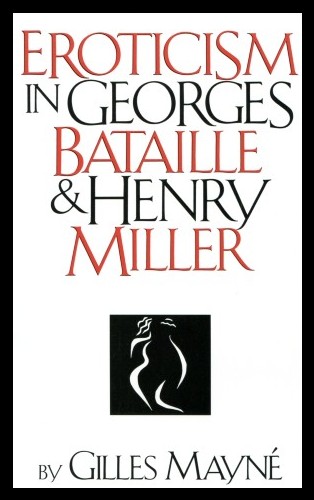

Eroticism in Georges Bataille and Henry Miller

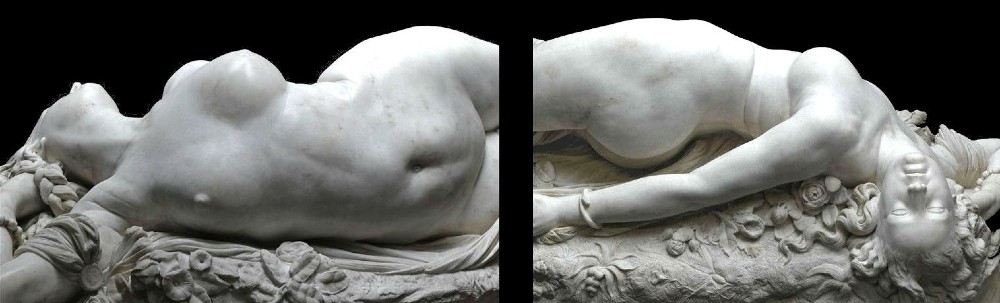

Auguste Clésinger, Femme piquée par un serpent, 1847 (detail)

GILLES MAYNÉ ON WRITING AND THE EROTIC IN BATAILLE AND MILLER

Posted by kind permission of Gilles Mayné, Professor Emeritus of American Literature at Université Jean Monnet, Saint Etienne (France)

From Gilles Mayné, Eroticism in Georges Bataille and Henry Miller (Birmingham, Alabama: Summa Publications, 1993) pp. 1-6 (Introduction) and 163-168 (Conclusion)

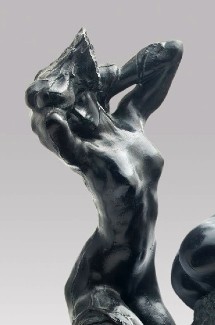

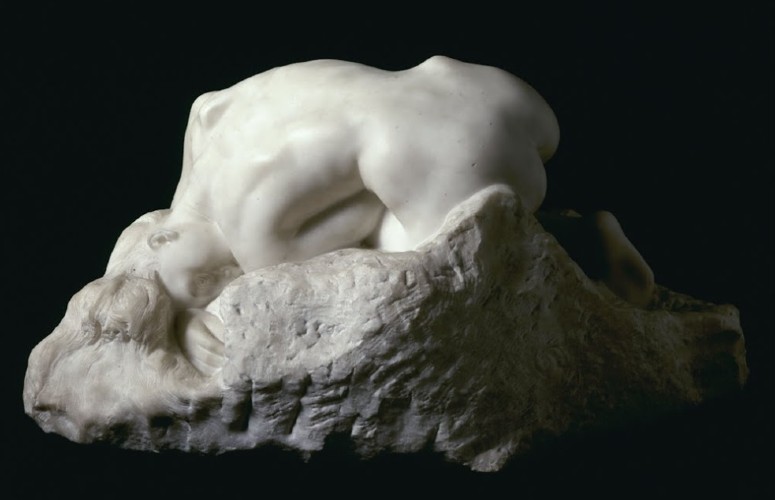

Rodin, Meditation (The Inner Voice), 1896-97 (detail)

I. EROTICISM, PORNOGRAPHY, THE OBSCENE

The following text constitutes the Introduction to Eroticism in Georges Bataille and Henry Miller.

The Conclusion, contrasting Bataille’s and Miller’s conceptions of writing the erotic, follows the section, ‘Eroticism in Literature in Mara, Marietta’.

If the adjective ‘erotic’ points to a quality, ‘eroticism’ seems to put into play a constellation of qualities whose unstoppable movement suddenly tears us away from the quiet ordering of our day-to-day reality. The erotic experience brutally confronts us with the following choice: either live such an experience fully, ‘now,’ or altogether miss (the intensity of) such an experience. In pornography we do not experience the urgency of a choice which does not really present itself as one since, in order to get excited, we have decided to rely on a medium that guarantees such a sexual excitement. In Webster’s dictionary, pornography is defined as ‘the depiction of erotic behavior (as in pictures or in writings) intended to cause sexual excitement.’

Tracey Emin, Sunday Morning, 2015

If pornography is generally considered to be the calculated arousal of sexual desire, eroticism disconcerts us so much that the arousal of our desire seems to exist prior to and against calculation. Eroticism defies calculation and we sense that conversely, calculation might mark its very end. In the erotic experience, there is always an unknown, whether in the other person (the lover) or in ourselves (in the way we are going to react to what the lover does). Such an uncertainty is at the source of our growing desire: we can never tell what will happen next, and it is precisely to the extent that we cannot, that we get increasingly excited.

Tracey Emin, Spending Time with You, 2015

By contrast, pornography is the domain of certainty. Under our initially fascinated eyes, beautiful bodies make love and we know they are going to make love again. The fascination, however, recedes as we realize that such bodies almost always do so according to the same mechanical scenarii but with different partners. The show becomes more and more monotonous as the partners, more often than not, have to demonstrate the whole gamut of sexual positions, as if they were trying to establish some kind of record. To make a long story short, in pornography the act of love is repeatedly carried out, performed, consummated, and never fails to culminate in the—real or fake—ecstatic cries of the performers. Pornography has its rules. Pornography, as any other business, must sell, and for want of quality it must be able to at least grant a certain ‘quantity.’

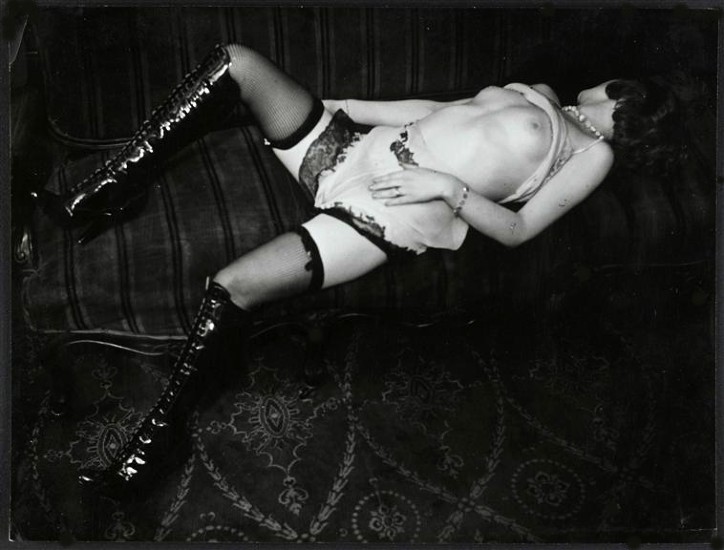

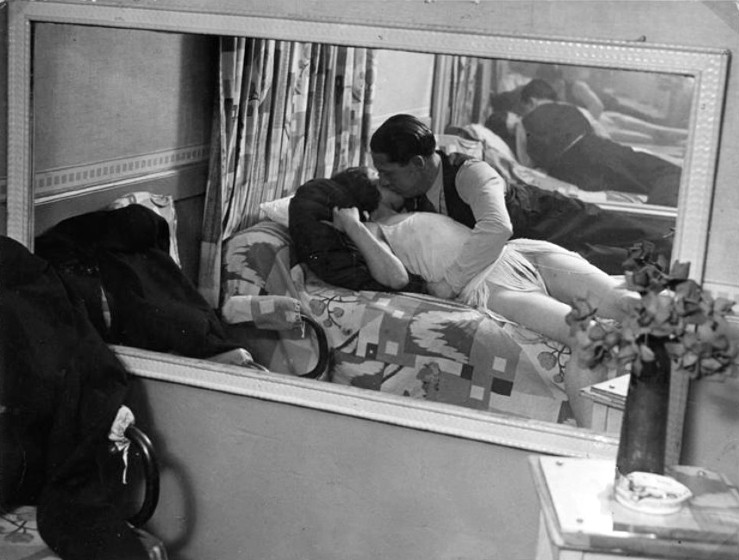

Brassaï, Fille dans un hôtel de passe, c.1932

Definitions of obscenity are so tinted by moral overtones that for the most part they leave us in a state of perplexity. Declared obscene is that which is ‘disgusting,’ ‘filthy,’ ‘grossly repugnant,’ ‘shocking,’ ‘offensive,’ ‘revolting,’ ‘lewd,’ ‘lustful,’ ‘provocative,’ ‘repulsive,’ ‘coarse,’ etc. (The list of such adjectives could become monotonous.) As one can see, what all these definitions have in common is not to inquire further about, precisely, what is ‘obscene’ (examples of obscene objects or situations are conspicuously lacking) nor to whom. They all seem to ignore that whatever is declared obscene in one country is not necessarily declared so in another. We have to go, in this respect, far beyond national boundaries to consider not only states (in the U.S., laws on obscenity vary from one state to another) but also societies of various sizes, and even tribes—that is, potentially any human community—not only geographically, but also historically, for obviously what is obscene in one period is not necessarily so in another.

Brassaï, Black Corset, c.1934

Furthermore, these definitions do not draw a clear line between pornography and obscenity inasmuch as they declare obscene, for instance, that which is ‘designed to incite to lust, depravity, indecency.’ Such a sentence stresses in obscenity, as in pornography, the intentionality to shock. But if obscenity equals pornography, why bother using two different words to designate the same notion? Is obscenity always intentional? If it is not (as it does not seem to be), what is the ‘non-intentional’ obscene, the obscene per se that these definitions seem to repeatedly ignore (repress)? We should obviously recognize that some objects, animals, situations disgust us for what they are (as they initially appear to us) and not, necessarily, for having been ‘designed to disgust us.’

Graciela Iturbide, Conejos en la luna, 1987

The French dictionary Robert dissipates somewhat the confusion surrounding the notion by declaring obscene ‘that which offends decency directly and presents a very shocking character while displaying without alleviation, with cynicism, the object of a social prohibition, especially one of a sexual nature’. This definition has the advantage of stressing, in order for something to be declared ‘obscene,’ the necessity of the transgression of a social prohibition. Every social community has its own taboos, and in particular, its sexual taboos. This allows us to look at the three notions: eroticism, pornography, and obscenity from a different perspective. Animals do not know prohibitions. In pornography, the actors are not animals, but in just performing the sexual act, they reduce it to a state of mere animality. Nowhere do we find any indication at all that the performers might encounter problems transgressing a social taboo. On the contrary, everything conspires to create the impression that, indeed, there is no prohibition involved and that, consequently, no violation of such a prohibition ever occurs. Sexual taboos are being violated right before us, immediately—without the mediation of consciousness—and so casually that, if we are ever shocked by such a transgression, its effect slowly recedes and leads almost invariably to boredom.

Andy Warhol, One Hundred and Fifty Multicolored Marilyns, 1979 (detail, desaturated)

The obscene confronts our consciousness more directly than pornography and forces on us a more violent reaction of disgust. But whether the display of the transgression of a social prohibition is intentional or not, the initial profound shock we experience, as with pornography, abates as we are allowed to contemplate such a display at length (‘with cynicism’ and ‘without alleviation,’ that is to say without restriction).

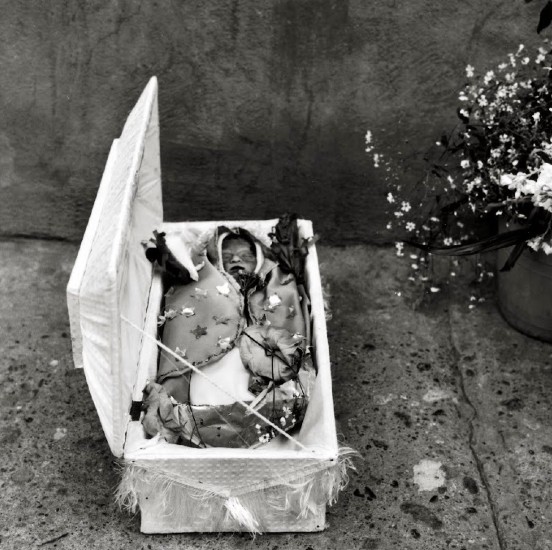

Graciela Iturbide, Cemetario de Dorlores Hidalgo, 1978

What characterizes eroticism, in sharp contrast to pornography and obscenity, is the fact that in an erotic experience the prohibition arrests us and suspends our consciousness: we keep telling ourselves that we cannot transgress a prohibition until the very moment when we realize that we must transgress it, that we are indeed already transgressing it and, what is more, that we are enjoying such a transgression to the utmost. In other words, we are enjoying the transgression of the impossibility to transgress the social prohibition. Clearly, between awareness of the impossibility to transgress this taboo and the actual experienced transgression of such a taboo, we have entered a phase in which we do not know what is happening to us (this passive mode is here unavoidable); a phase of supreme(ly enjoyable) hesitation which, as the transgression goes on, forces us to distort our own social, religious, and, above all, linguistic preconceptions.

Brassaï, Phénomène de l’extase, c.1933

The fact that it is our very language that eroticism ‘threatens’ is confirmed by the way society ‘deals’ with pornography. Every society has its prostitutes, its pornographic shows, films, magazines, and books. Pornography has always been, and still is, a business protected by society. But, paradoxically, it is not the brothels, sex-shops, magazines, or movies that society censures as ‘pornographic,’ but its Stendhals, Flauberts, D. H. Lawrences, Joyces, Henry Millers, not to mention its Sades. Such a list would be too long to enumerate—a list, by the way, still growing. In what constitutes more than a little hypocrisy, while society condones the diffusion of pornographic materials, it censures as pornographic serious literature (let us understand by this the literature of people who really have something to say and say it well: Literature with a capital ‘L’).

‘SOCIETY CONDONES PORNOGRAPHY BUT CENSURES SERIOUS LITERATURE’: LAWRENCE, JOYCE, MILLER

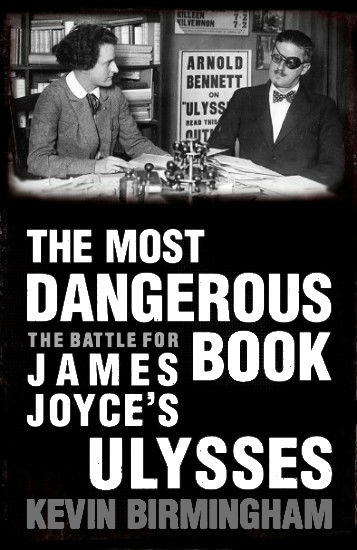

Joyce, Ulysses (1922)

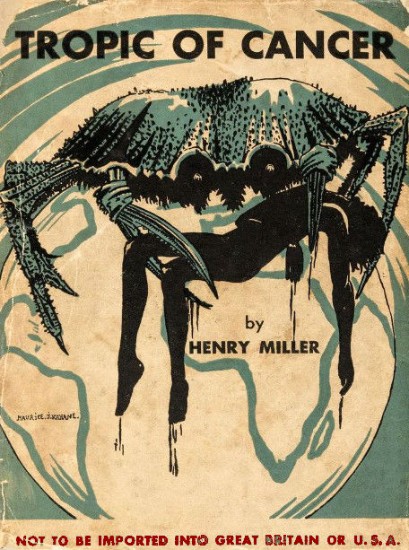

Miller, Tropic of Cancer (1934)

Lawrence, Lady Chatterley (1928)

Joyce, Ulysses (2020)

Miller, Tropic of Cancer (2020)

Lawrence, Lady Chatterley (2020)

Thus, society accuses Literature of being obsessed with openly prurient sex—all the while tolerating its expression in other media. But, in so doing, what it actually censors is clearly not the pornographic character of such a Literature, but its eroticism. This allows us to conclude that eroticism is socially dangerous not as a private practice (eroticism lived ‘privately’ within the couple is even considered a factor of social homogeneity), but whenever it is made sensitive through artistic symbols and particularly through words and word-arrangements—that is to say, as soon as it is represented. The representation of eroticism—that is the language of such representation—disturbs society much more severely than its mere practice.

Brassaï, Chez Suzy, rue Grégoire de Tours, c.1934

The two authors I shall compare, Henry Miller (1891-1980) and Georges Bataille (1897-1962), were both well aware of that fact. Both were particularly sensitive to the necessity to question and break away from the linguistic canons of literature in order to express their revolt. Henry Miller, a great admirer of European literature, once declared, ‘When the Europeans are shocked, it is because of the language itself, what has been done to it and with it by the author, not by the moral or immoral implications of this language’.

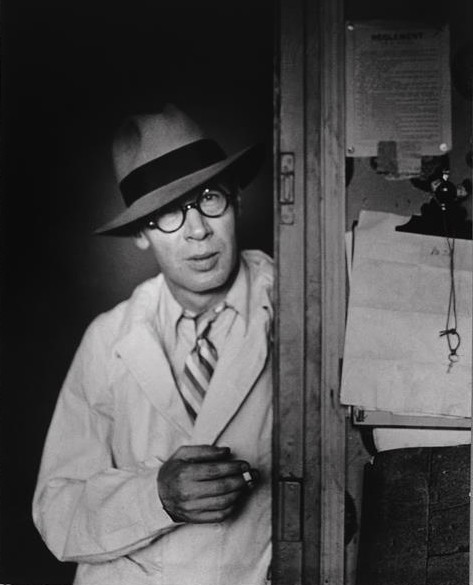

Henry Miller, Paris, 1931 | Photo: Brassaï

Both perceived their revolt against society as a necessary revolt against the language of that society and strongly felt that they had to wallow in obscenity in order to force the reader to experience the strong chaotic reactions characteristic of eroticism. According to Miller, obscenity functions as a privileged ‘technical device’, not in the least pornographic, which has to be used in order to disclose a greater realism, as the following quotation attests [from Henry Miller on Writing, New Directions, 1964, p. 186]: ‘When obscenity crops out in art, in literature more particularly, it usually functions as a technical device: the element of the deliberate which is there has nothing to do with sexual excitation, as in pornography. If there is an ulterior motive at work it is one which goes far beyond sex. Its purpose is to awaken, to usher in a sense of reality.’

Henry Miller, Paris, 1931 | Photo: Brassaï

In order to ‘usher in’ such a ‘sense of reality’ Henry Miller displays in his fiction one of the most violent movements of revolt in twentieth-century literature. On the opening page of his first book, Tropic of Cancer, Miller writes: ‘This then? This is not a book. This is a libel, slander, defamation of character…. No, this is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art, a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty… what you will.’

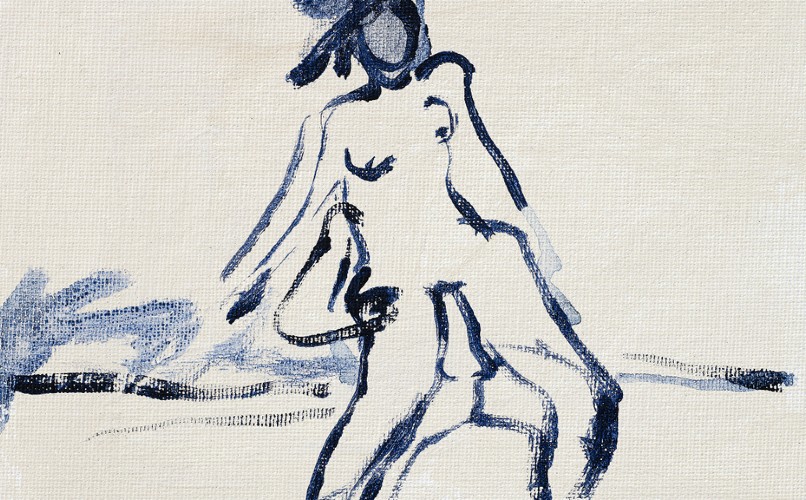

Tracey Emin, from the Egon Schiele series, c.2015

According to Georges Bataille, whom La Grande Encyclopedie Larousse consecrated in 1976 as ‘the greatest philosopher of eroticism’, the part that obscenity plays in eroticism is central. In L’érotisme, a major work which Bataille wrote near the end of his life (1957) and in which he condenses, regroups, and sometimes clarifies concepts and analyses spread over more than thirty years of writing, he declares: ‘I see a close relation between my repulsion for things that are rotting and the feeling I have for obscenity. I can say to myself that repugnance, that disgust, is the principle of my desire.’

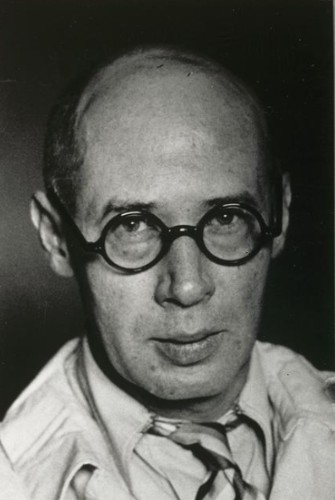

Georges Bataille, Paris, 1957

In the early thirties, Bataille’s ‘obscenity’ outraged Breton and inspired in him a quasi-visceral movement of rejection of Bataille. Soon afterwards, in an article on Sade, Bataille pushed his investigations on the obscene so far as to form the apparently insane project of establishing what he called a ‘heterology’ or, more suggestively, a ‘scatology’, and defined as the ‘science of excrement’. A philosophy, a science? These are disciplines that we do not usually associate with eroticism—although it does not escape our memory that the same Sade once wrote a book called La Philosophie dans le boudoir. Obviously in life, the practice of eroticism seems to have very little to do with, and even seems poles apart from, the practice of philosophy. However, if one wants to represent in writing the great intensity of the erotic experience without losing anything of such an intensity, one faces unfathomable—and indeed epistemological—problems.

Georges Bataille, 1933

Georges Bataille is the first writer in the history of Western thought to have become aware of such epistemological problems with relation to eroticism; the first to have seen clearly that the erotic experience is impossible to represent—simply because language takes us so forcibly and relentlessly away from it—and to have squarely faced the consequences.

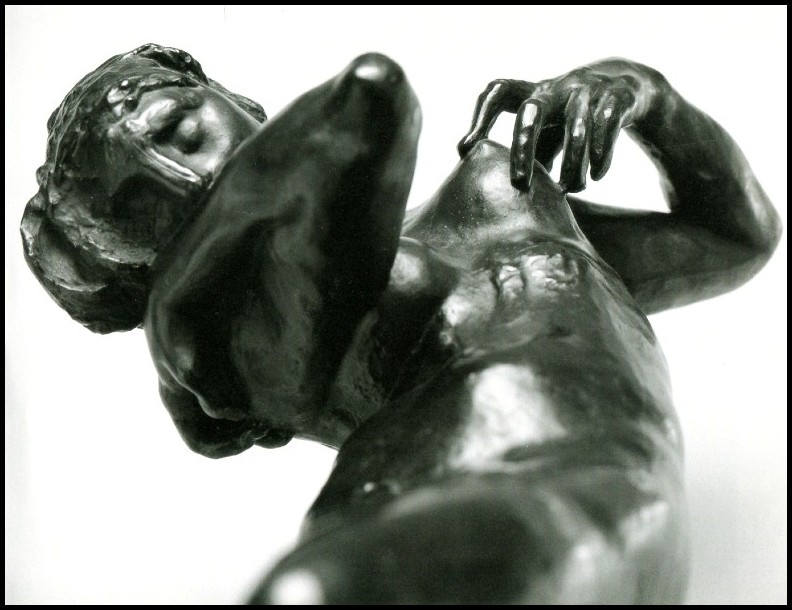

Rodin, One of the Danaides, 1885-89

This doesn’t mean, however, that the writer should quit trying to write about such an experience. Far from it, the writer, being aware of such an impossibility, faces an enhanced challenge: the necessity to reach, through words, what Bataille calls, in many instances, ‘the absence of poetry’, and in so doing, to give access to an experience equivalent in intensity to that of the erotic experience.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647-52 (detail)

‘EROTICISM IN LITERATURE’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 13

̶ And you, Sprague, what do you do? Maya asks.

̶ I’m trying to turn a haiku into a novel.

̶ That’s very ambitious.

̶ Yes.

̶ Do you have enough material—how many syllables are there?

We all laugh.

̶ Seventeen. But it’s not the poem, it’s the image that inspired it.

̶ And what’s the image?

̶ It’s a woman observing herself in a mirror while sperm slowly spills from her mouth.

̶ I see!

She slurps another oyster.

̶ And what’s it going to be? A porno novel, a summer bestseller, a literary masterpiece?

̶ All three!

Decidedly, I do like her green-grey eyes, her shaggy black bob.

Shunga scene | British Museum

̶ Recite me the haiku.

̶ All right.

The blue of your eye

Scintillates: You surrender

My temporal soul

̶ It’s very subtle.

̶ There’s another version. An image of her dripping the sperm into her bath. It goes like this:

Milky cloud, swirling;

Evanescent smoke, curling:

Who am I? she asks.

̶ I like that one! Put the two together and you’ve got a perfect poem. It makes a sequence, it gives it closure.

̶ Closure’s against the Zen aesthetic. Anyway, those are the seventeen syllables I’m trying to turn into a novel.

Shunga Scene | National Museum of Asian Art (Washington DC)

̶ And what’s the story?

Danger comes to edge her eyes, mischievousness to wet her lips.

̶ The book begins when the story’s over.

̶ Then it won’t be a bestseller. People want stories. That’s why they read novels.

̶ I know. But for me, everything interesting happens when the story’s over. That’s when you can cut to the bone, that’s when there’s nothing left to distract you from your soul.

̶ Then it won’t be a porno novel. Readers of porno don’t want introspection.

̶ I know. But pornography’s only interesting when it’s combined with philosophy.

̶ Then it won’t be literature. Readers of serious books don’t want pornography.

̶ I know. So what do you suggest I do, Maya?

̶ I don’t know.

She slurps her last oyster.

̶ But whatever you try, here’s to you!

She raises her glass. You and Raphaël join in the cheer.

̶ To your literary-porno bestseller!

In the lambent silver-blue light, in the daring-glass of my dreams, I see an artist who can accomplish anything, because you are part of his schemes.

Shunga Scene | British Museum

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

II. WHAT MAKES WRITING EROTIC?

The following text constitutes the Conclusion to Eroticism in Georges Bataille and Henry Miller by Gilles Mayné.

What makes writing erotic, what permits us to conclude that a text is erotic when another is not? If in life eroticism presents itself to us in its immediacy as a force that directly takes us away from the quiet ordering of day-to-day reality, in any writing we have to deal with eroticism mediated with words, that is with abstract symbols. Words, as part of organized sentences, try with the utmost insistence to mold the genuine movement of eroticism, which has no rules, into the syntaxico-grammatical rules of which language is made. At the same time, as symbols, words always project us into a higher conceptual reality to which this erotic movement does not belong. Language deviates by nature from the most intimate movement of eroticism—whose principal characteristic is that it cannot be fixed in any static reality, whether of the high or of the low, of the beautiful or of the obscene, of the good or of the evil. Eroticism does not belong to either one of these opposite realities; in fact it cannot belong at all: it can only be the constant interplay between such opposites, the constant slippage from one into the other without any possible end, or without any possible end other than the ecstatic point at which they undo themselves and come to ‘coincide’ or to ‘marry’ each other—the point at which each comes to be the other.

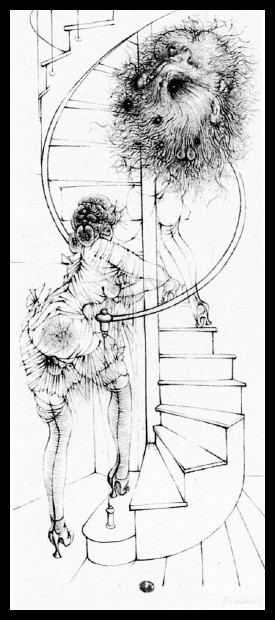

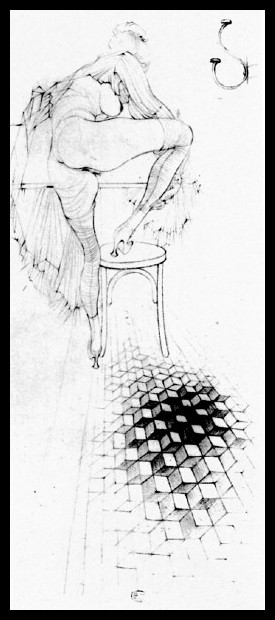

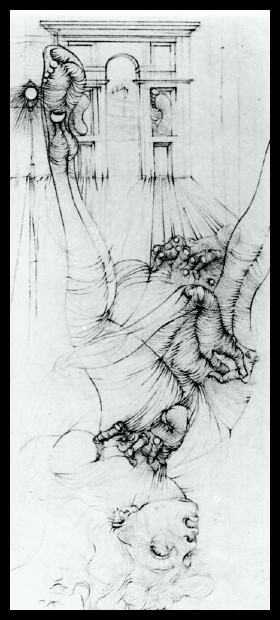

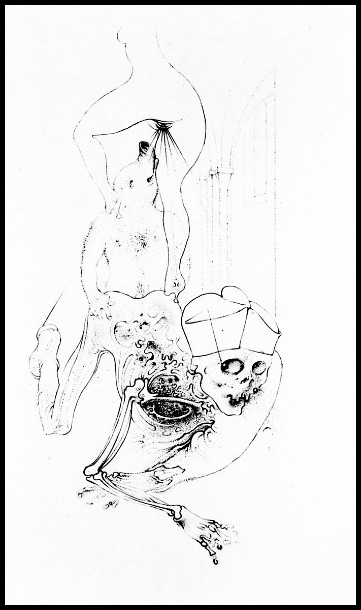

Hans Bellmer

Madame Edwarda I, 1965

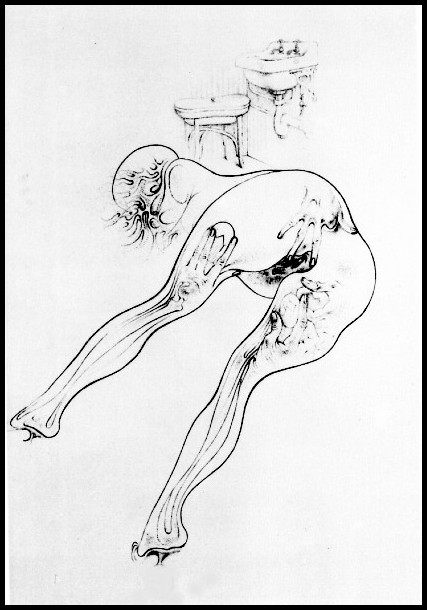

Hans Bellmer

Madame Edwarda II, 1965

But language makes such a point at which opposites come to ‘copulate’ with their Other extremely difficult to attain, not only because it naturally elevates the intimate movement of eroticism, but also because eroticism is generally perceived as joy, rapture, in any case as elevated feelings. A writer who will not resolutely address the elevating virtues of language will therefore always place writing in a position of succumbing to these elevating virtues, of yielding to their charm and, in so doing, of transforming writing into a quest for pleasure and an instrument of self-gratification. This sort of writing will consequently project its readers into a superior reality capable of providing them with the easy satisfaction of a ‘soft’ or ‘mild’ or ‘flabby’ eroticism which would altogether fail to meet eroticism’s fundamental challenge.

Hans Bellmer

Madame Edwarda III, 1965

Hans Bellmer

Madame Edwarda IV, 1965

Any writing which, consciously or not, makes eroticism an object of satisfaction no longer leads to eroticism but to eroticism satiated or satisfied. Such writing necessarily fails to see that these moments of rapture that we associate with the reality of happiness have only been made possible by our having confronted ourselves and having taken part in the most intimate way in realities that are strictly speaking unspeakable. So-called happiness is only the dead remains of a ‘successful’ erotic experience: the eroticism one speaks of is always successful eroticism and that is quite normal because one simply cannot speak of pure eroticism, of the one that may or may not be successful. One cannot speak of chance: chance can only ‘fall’ at the most unexpected moment; one can only give oneself entirely to it, be ‘played with’ by it, be it. In the endnotes to Le Petit, Bataille writes: Of chance I cannot say: ‘it belongs’ (chance can slip away at any moment); nor exactly: ‘I’m looking for it’: I can be it, I cannot look for it. In eroticism we are sovereign, we are chance in the making, chance as it takes possession of our selves so insistently that it keeps preventing our selves from recovering, from regrouping, from making a new possession of our being possessed by it, a new object of knowledge.

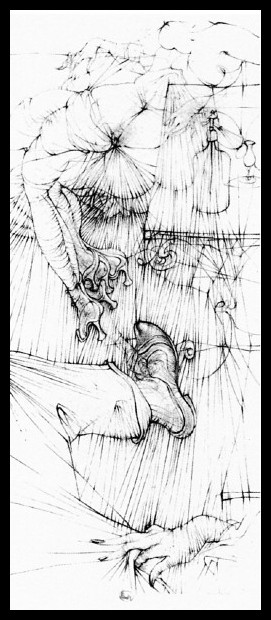

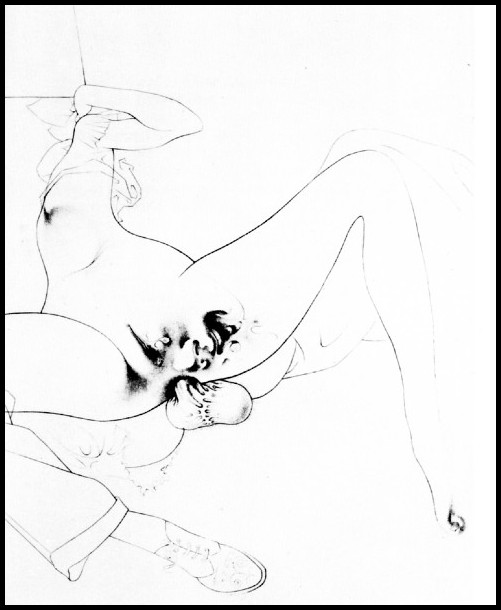

Hans Bellmer, Story of the Eye I, 1944

One cannot emphasize too much such a movement: chance is no object that we can possess, but a thing-that-keeps-evading-our-control: a ‘no-thing.’ The only way to speak of eroticism is to try by all means to make this no-thing, this ‘thing’ which can never become a thing and thus cannot be spoken of ‘speak for itself,’ that is, just happen: be spoken of by chance. But this means much more than to speak of nothing and everything. It implies on the contrary being unable to speak of nothing else except the impossibility of speaking of that ‘thing’ that cannot be spoken of—to have no other choice than to question unremittingly this language which constantly reduces the impossible force of desire to the possibilities of words, keeping open the eventuality—the chance—of words appearing that cancel themselves out and go out of themselves as violently as the lovers go out of profane reality.

Hans Bellmer, Story of the Eye II, 1944

In general, modern art subscribes to such a movement—at least theoretically—not only in literature and painting, but also in architecture, sculpture, and music as well. In the second half of the nineteenth century, certain artists realized that if art were still to express the most powerful, most profound feelings of man, it could no longer be a plain, mimetic representation of external reality, but a perversion from the inside of the traditional modes of representation showing reality as it was represented before—and thus the medium responsible for such representation—in the process of undoing themselves.

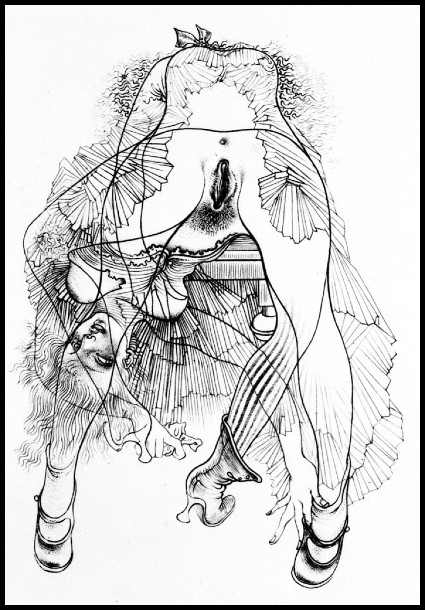

Hans Bellmer, Story of the Eye III, 1944

The reflexivity of modem art, the impossibility in which it places the medium of art not to question the canons of beauty, and thereby not to question itself, finds its best illustrations in Rodin, Turner, Manet, Van Gogh, Picasso, Duchamp, Bacon, and, long after Sade, in such writers as Lautréamont, Rimbaud, Mallarmé, Artaud, Bataille, Blanchot, and Derrida. Of all these, it was Bataille who envisioned most clearly the challenge at stake in modern writing, a movement which Derrida takes up again in the sixties and seventies under the motto of ‘problematics of representation’ and whose argument can be summed up as follows: ‘How can a work re-present the impulse which is at its origin without betraying such an impulse by shutting it up inside a form which obviously cannot contain it?’

Hans Bellmer, Story of the Eye IV, 1944

At the time when Bataille was writing and after Bataille, during the period when French modernité made such problematics central, Henry Miller remained absolutely impervious, if not hostile, to its argument: in fact, he seems to have been completely unaware of it. Instead of testing the chance for words to be other-than-what-they-are, instead of affirming the chance of their ‘Otherness,’ Miller’s writings tend to repress such a chance, to control it and sublimate it by always yielding to more words, more metaphors, more stories, under the enormous weight of which this chance eventually disappears. Miller does not ignore the fact that eroticism makes us take part in the intimacy of the lowest realities. Instead of trying to preserve the integrity of the movement of interplay which, at one point, leaves beings and words with no other choice than to encounter these low realities and force them out of themselves, out of language, he is content with preserving unconditionally the transparencies of language to depict the low realities of eroticism, knowing that he always has at his disposal the ultimate weapon of obscenity.

Matisse, Le guet, nd

Miller ‘decides’ to shock, to be obscene, but he obstinately refuses to see that obscenity in itself can only become less and less obscene if it is not forcefully related to the prohibition of obscenity. In not doing so, he almost makes obscenity the object of a cult. By trying too hard to shock, to be too systematically obscene, Miller fails to be really disturbing: he deflates obscenity and delineates a superior reality, a dream world in which ‘there can be no taboos’ (Capricorn, 192) since all prohibitions can be easily removed from it. Instead of butting against an impossible thing, he takes refuge in a reality where nothing is impossible, thus in which everything becomes possible. Such a ‘total’ reality, since it is not that of knowledge (Hegel’s), is that of a flashy, almost beautiful fiction in which Miller traps himself. Miller confines himself to a ‘desperate game of provocation’ directed at others; at us: ‘In the horror of no longer being tricked he moves towards his last resort—he tries to trick someone else in order to trick himself for an instant.’ (Bataille, Literature and Evil, 160).

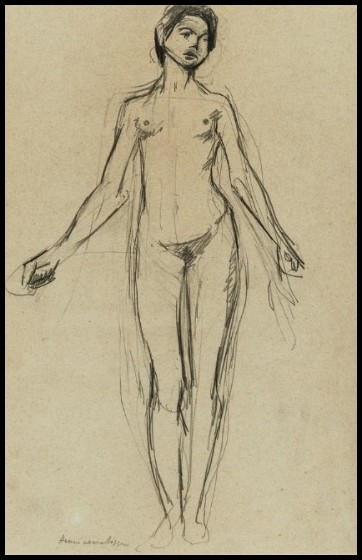

Matisse, Nude Study, 1900

By systematically plunging into the low, Miller converts this low into just another high. By yielding without reservation to evil, Miller ends up changing this evil into a good. One can apply almost word for word to Miller the terms of the criticism that Bataille, in La littérature et le mal, addresses to Genet. Discussing Sartre’s Saint Genet, Bataille opposes two forms of communication: ‘weak communication’ is the profane, rational communication that rules almost all compartments of our existence, whereas ‘strong communication’ is the ‘sovereign’ moment when profane communication ‘fails and becomes the equivalent of night’ (Literature and Evil, 170). For Bataille there is no difference between ‘strong communication’ and ‘sovereignty’. Bataille accuses Genet of having refused such a ‘sovereign’ communication: ‘It is for denying himself communication that Genet never reaches the sovereign moment, the moment when he would at last cease bringing everything back to the preoccupations of an isolated being. It is to the extent in which he abandons himself completely to Evil that communication escapes him.’ (Literature and Evil, 173).

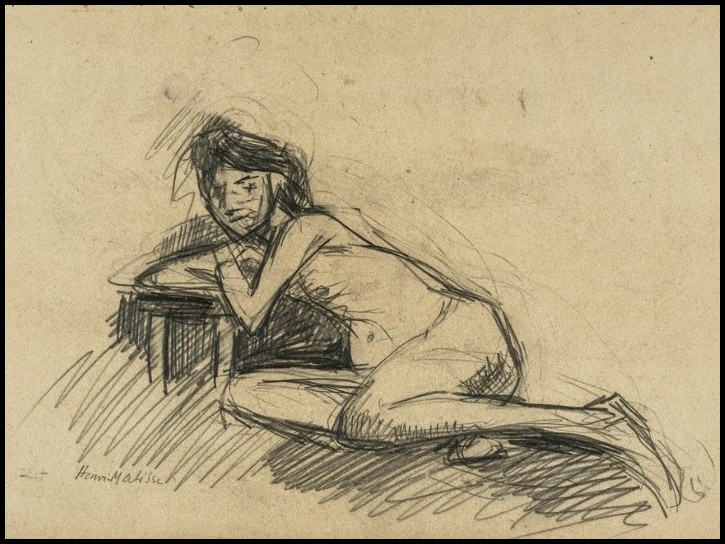

Matisse, Nude Study, 1902

Like Genet, Miller resorts to Evil ‘in order to exist sovereignly for his own benefit alone’. To the extent that he tries to make it a good, a possession, Miller’s sovereignty becomes ‘sovereignty confiscated’; ‘the dead sovereignty of him whose solitary desire for sovereignty is the betrayal of sovereignty’. In what can be interpreted as a puritanistic reflex, Miller, instead of yielding to the vertigo of the moment, ‘prefers’ to let himself be projected, by the project that words form, towards a Golden future in which he deifies himself. If Bataille, by being surreptitiously god-transgressing-his-own-limitations, is more god than god, or ‘GOD’ (making in this instance the concept of ‘God’ literally burst), Miller wants to become ‘more and more (the) God’ (Capricorn, 204) of a universe in which it is apparently forbidden to forbid (for such is the understatement that his prose makes). But this universe hides another, much more disquieting one, which is not that of the ‘whole man’ which he claims so much to be, but that of ‘total man’ who finds himself again and regroups in order to complete himself and better secure his identity. Miller stands in this universe as the monarch whose absolute (and ‘omnivorous’) powers do not exclude the power of being comical, the most important thing for him being at any rate to be something and to show that he is someone (to be recognized). Like Genet, Miller wants to ‘petrify himself,’ freezing the sovereign movement of eroticism.

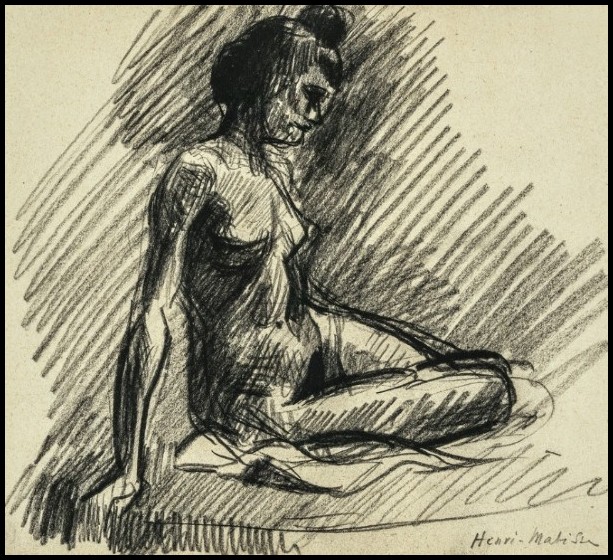

Matisse, Seated Nude, 1902

Under the guise of liberalism, Miller’s universe hides the most cynical, dangerous realities. His transforming evil into a good does not make evil a ‘lesser’ entity but, on the contrary, what Heimonet calls the ‘worst’ evil: evil not felt as an evil and just performed without the awareness of it (although with a certain pleasure); the icy evil of brutal force; evil legitimated, legalized and institutionalized—made a totalitarian system: ‘Opposed to the unleashing of passions, the worst evil is apathetic, coldly performed evil in which power uses passion in order to turn its force into a thing or a law, making it ‘this servile, well under control, overfed passion, which is the basis for all police systems and which serves as a mainspring for totalitarian regimes.’

Matisse, Standing Nude, 1902

To compare Georges Bataille to Henry Miller implies not only distinguishing between an author in whom eroticism transpires in every word, and another who, for being ‘weakly’ erotic, eventually fails to be erotic at all—but also measuring the enormous difference between a writing that must at all costs challenge itself unremittingly and one, such as we find in Miller, which brutally represses this challenge and denies its crucial centrality to a (post-)modern writing that, because of such a challenge, should only be erotic.

Henri Matisse, The Model, 1901

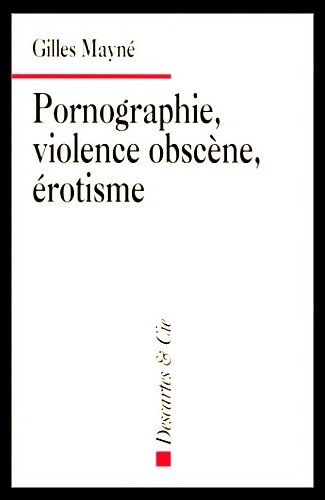

GILLES MAYNÉ: THREE BOOKS

Pornographie … érotisme

Bataille & Miller

Georges Bataille