MARGUERITE DURAS

L’Amant | L’Homme assis – Maladie

MARGUERITE DURAS: ERROR, INTERTEXTUALITY, AND ‘ÉCRITURE COURANTE’

James S. Williams on L’Amant and L’Homme assis dans le couloir – La Maladie de la mort

Posted by kind permission of James S. Williams, Professor of Modern French Literature and Film at Royal Holloway, University of London

From James S. Williams, The Erotics of Passage: Pleasure, Politics, and Form in the Later Work of Marguerite Duras, pp. 72-76 and 83-87

L’AMANT

For the adolescent girl-narrator of Amant, the supreme moment of jouissance would be to make her Chinese lover do to her schoolgirl friend, Hélène Lagonelle, exactly what he does with her, and in her presence:

I want to take Hélène Lagonelle away with me to that place where every evening, with my eyes closed, I have imparted to me the pleasure that makes you scream. I’d like to give Hélène Lagonelle to that man who does this to me, so that he may do it in turn to her. I want it to happen in my presence according to my wishes. I want her to give herself where I give myself. It’s via her body, through it, that I would then experience from him ultimate pleasure. A pleasure unto death.

L’Amant, Jean-Jacques Annaud

This stunning scene of imaginary fulfilment, locus of all the sexual and racial crossings in Amant, has been celebrated in various ways. For some critics it shows how each participant can occupy all positions, and thus how the feminine self in particular can gain power by envisioning herself as other. For others, it represents both interchangeability and fusion, the culmination of the text’s ‘ethics of non-differentiation’ and ‘ex-centricity’, i.e. its openness to the third which enriches jouissance and opens up the union of the couple to an absolute. Even Elizabeth Meese, while recognizing that the narrator refuses one unthinkable move, i.e. herself and Hélène as lovers, nevertheless argues that this configuration of desire signals a partial disruption of the usual subject/object relation and, hence, the ‘perpetual unease of (ex)tension and change in the subject’.

Hélène (Lisa Faulkner) & the Young Girl (Jane March), The Lover, Jean-Jacques Annaud

Any idea, however, that this imaginary encounter is a benign passage of giving and non-possession is contradicted somewhat by the fact that the girl-narrator would be in total control of the other participants’ desire. Indeed, the scene is conceived primarily as a tribute to her own uncompromising will-power: ‘She says that she wants to do it. She does it’. More importantly, when seen in context, although the episode is presented as a formulation of ultimate heterosexual bliss between je and lui, it actually marks the resolution of an uncontrollable, murderous, female desire for Hélène expressed by je just moments before: ‘Hélène Lagonelle makes you want to kill her. She conjures up the wonderful dream of putting her to death with your own hands. I am worn out with desire for Hélène Lagonelle. I am worn out with desire’.

The Young Girl (Jane March) & Hélène (Lisa Faulkner), The Lover, Jean-Jacques Annaud

The principal reason for Hélène’s attraction is the ‘fabulous power’ of her breasts which receive in Amant the kind of narrative attention never accorded to the body of the Chinese who is merely the ‘motor’ of jouissance. These impossible white objects of desire, which demand to be kneaded and retained by an other, any other (‘She [Hélène] offers these things for hands to knead, for lips to eat’), inspired in je a masochistic desire that took the particular textual form of a chiasmus: ‘To be devoured by those flour-white breasts of hers’). In this sequence, ‘seins’ has been reversed into ‘les siens’, which, although in the context clearly means ‘hers’ (i.e. Hélène’s), could also, theoretically, denote ‘his’ (i.e. the Chinese lover’s). Masochistic desire is indiscriminate, and it is left to the differentiating structure of the chiasmus to emphasize this point.

Hélène, The Lover [from the rushes], Jean-Jacques Annaud

Inspired, as it were, by this chiastic ordering of forces, the girl-narrator’s controlled circuit of imaginary desire, where she positions herself both masochistically (she is excluded from the sexual act) and sadistically (she is in total control), allows her to desire Hélène narcissistically as a projection of her own desire for sexual ravishment. In the process, Hélène’s ‘sublime’ and amorphous body, ‘incomparable’ like the ‘sea without form’ of sexual jouissance, finds itself rechannelled into the rediscovered, protective, ‘lagoon’ waters of formal, heterosexual desire ([le]Lagon-elle), there to function as no more than a mirror reflecting in the clearest of light the jouissance experienced between je and lui. This reorientation of sexual desire restages and reinvests all the other crossings in the novel made by je, in particular her crossing of the Mekong river, an event of mainly metonymical displacement since her male fedora hat was only ‘displaced’ like the vehicles doubled up against each other on the ferry, and because the ensuing sexual ‘experiment’ with the Chinese led simply to a repetition of her family’s violence, pain, despair and dishonour.

Jane March, L’Amant, Jean-Jacques Annault

Yet the chiastic twist on ‘seins’ and ‘siens’ also represents the culmination of the adult narrator’s own sustained play on Hélène’s floating, ineffable name: elle, ‘aile’ (wing), Hélène L., Hélène Lagonelle, H.L. For as soon as Hélène has been made formally equivalent to the Chinese—’I see her as being of the same flesh as that man from Cholon’—she is then dispensed with, almost indifferently, by a selectively erratic memory: ‘I don’t know what became of Hélène Lagonelle, or even whether she’s dead’.

Jane March & Tony Leung, The Lover, Jean-Jacques Annaud

If Hélène was presented earlier as the only female figure to escape the ‘law of error’, or ‘that self-lacking in women brought about by themselves’, due to her arrested mental development, she now becomes one of its victims. For this reason, Amant celebrates less Hélène’s escaping of the ‘rule of error’ than its own ironic ‘errors’ of accelerating textual abstraction, a strategy highlighted by the ideal, ‘defectless’ immortality of the narrator’s ‘younger brother’, revealed in a late correction to have been two years her senior. All the while, the text’s founding ‘error’—the apparent omission of an answer to the question posed on the first page: what happened at age eighteen to make the narrator’s face change so dramatically?—has gone by unchecked.

Hélène Lagonelle (Lisa Faulkner), ‘L’Amant, Jean-Jacques Annaud

But Amant’s dedication to Duras’s long-time film cameraman, Bruno Nuytten, also hints at the possibility of another ‘experiment’ operating in the novel since it encourages us to consider the cinematically prolonged, ‘absolute image’, the Mekong crossing, in properly cinematic terms. The only overt reference to cinema in the text hinges on a detail of the young girl’s hair during that momentous day, a detail linked directly to the image’s ‘determining ambiguity’ of the fedora hat. The narrator states: ‘I had never seen a film with those Indian women who wear those same flat-brimmed hats and plaits coming down in front of their body … I have two long plaits coming down over the front of my body like those women in the films whom I have never seen but they are children’s plaits’. Je/elle’s precocious powers of invention here are such that they pre-empt cinematic influence and twist it around in the form of a double plait.

Jane March & Tony Leung, L’Amant, Jean-Jacques Annaud

If we bear in mind the chiastic nature of this process—’I had never seen a film with those Indian women | plaits coming down in front of their body | two long plaits coming down over the front of my body | those women in the films whom I have never seen’—we see that it actually prepares for the narrator’s later eclipsing of Hélène’s breasts. Could it be, in fact, that Hélène is somehow linked to Indian cinema, or at least films about India? One such film is Jean Renoir’s The River (1950), a colour film shot in English on location near Calcutta and acknowledged by Duras as one of her favourite films precisely because it recalls her childhood spent in the bush. While the case for an intertextual link with The River cannot be proved, the autobiographically charged nature of Amant and its emphasis on foreknowledge invites the viewer to speculate that at each mention of the Mekong crossing it is actually ‘crossing over’ to Renoir’s classic. Let us therefore look briefly at the key elements of The River.

Jean Renoir, The River

Like Amant, The River offers a coming-of-age story set in the colonies. It is narrated on the soundtrack by the protagonist’s older self. Harriet, a misguided young girl and would-be poet, loses the love of Captain John who returned home to marry one of his cousin’s daughters (he remains the only character in the film to escape across the Ganges). Upon the death of her younger brother by snake-bite, Harriet finally resigns herself to a life of submission. In fact, the film is obsessed with the spiritual need for resignation (its motto is: ‘Consent to everything’), to the point even that it never performs the act of metaphor and metamorphosis which it constantly invokes. And whereas Amant emphasizes the sexual violence and pain of growing up, The River is content merely to evoke yearning, especially in its use of Indian actors for long sequences of festival dancing and in its creation of a general romantic mood, features which Duras admits in Yeux to finding highly problematic.

Jean Renoir, The River

By playing chiastically with Hélène’s ravishing, formless body, Amant can be said to have straightened out the different threads of The River, in particular Harriet, who is also a symbol of abortive passage and wasted potential (a fact reinforced by the superfluous, silent h of ‘Hélène’). Indeed, by projecting H.L. into an imaginary sexual scenario which lifts her temporarily out of regression and the destiny of her name, i.e. HomosexuaLité, Amant comments again self-reflexively on its own ‘experiment’, i.e. its correction of a classic foreign film made in English and dominated by ‘those Indian women’ of cinema.

Harriet (Patricia Walters), The River, Jean Renoir

Just as je/elle’s silence in Amant colluded with the family’s humiliation of the Chinese in a club named ‘La Source’, so, too, the novel elides the indigenous population of its cinematic precursor, consigning it to a space behind the shutters of the garçonnière and forcing it to function as no more than ‘the volume of a film turned on too loud’. Amant will continue to cross over (and cross out) The River in a perfect Duras marriage of form and content until je/elle’s first journey into sexual pleasure with her father-lover is finally replayed in reverse by her return crossing of the Pacific to the fatherland of France and the subsequent rediscovery of her mother’s ‘profound grace’.

Jane March & Tony Leung, The Lover, Jean-Jacques Annaud

Once this has taken place, the one imaginary moment of passage over Hélène’s body can finally be replayed and relegated to pure conjecture, as merely a probable scene of ‘domestic’ penetration between the Chinese lover and his Chinese wife:

Then the day arrived when it must have been possible. That day, precisely, when the desire for the little white girl must have been such, so impossible to control, that, as in an extreme, high fever, he could have rediscovered his complete image of her and penetrated the other woman with this desire for her, the white child.

Tony Leung, The Lover, Jean-Jacques Annaud

It is only through Renoir’s film that we can fully appreciate the effect of the fairy-tale end to Amant immediately following this last, narcissistic display of erotic attraction and which has seemed to many critics so untypical of the text as a whole. The Chinese’s swearing of eternal love, presented by the narrator in the controlling form of indirect speech (‘[he said that] he would love her until he died’), is nothing less than a final ironic spin, the kind of adolescent wet-dream that Harriet may have indulged in but which the always adult narrator of Amant expressly forbids.

L’Amant [composite image], Jean-Jacques Annaud

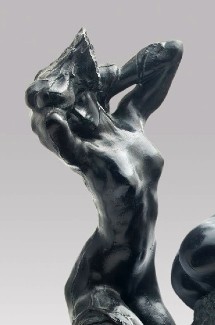

We see, then, that the major intrigue of Amant is intertextual in nature, and that rhetorical manipulation constitutes only the most visible aspect of a long and involved process of textual sublimation.

L’Amant, Jean-Jacques Annaud

L’HOMME ASSIS DANS LE COULOIR – LA MALADIE DE LA MORT

Without a circumscribed intertext there can be no intertextual perversion in Duras’s work and it risks falling into abjection. To gain a full measure of what is at stake here, not only for the Duras text but also for the Duras reader, let us see what happens when Duras directly approaches the sexualized body in her so-called ‘erotic’ texts, Homme assis and Maladie. Duras makes clear in Les yeux verts that she never intended the first of these to be published by Minuit and we shall quickly discover why.

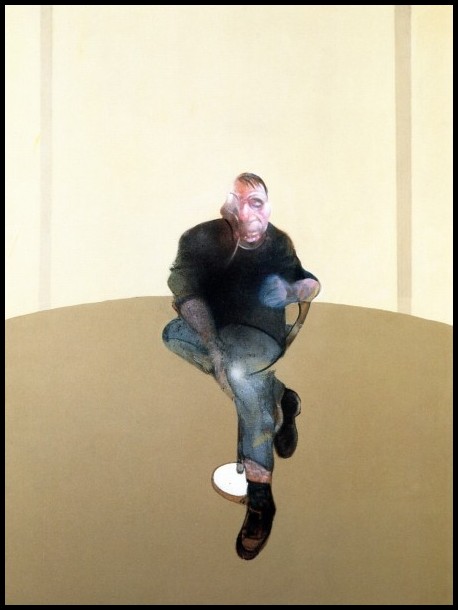

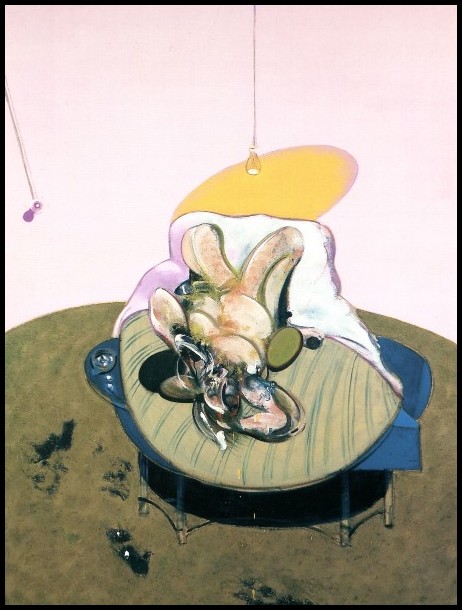

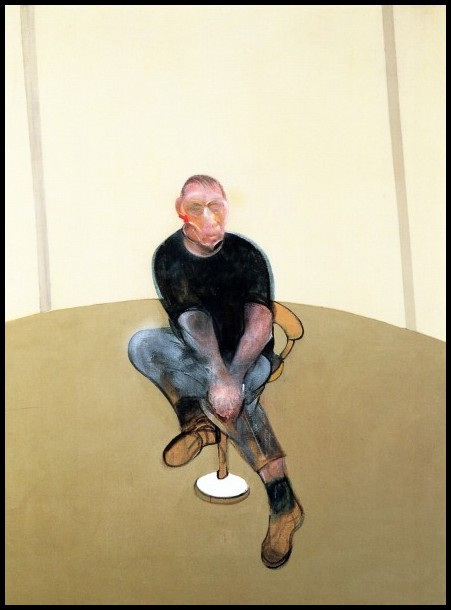

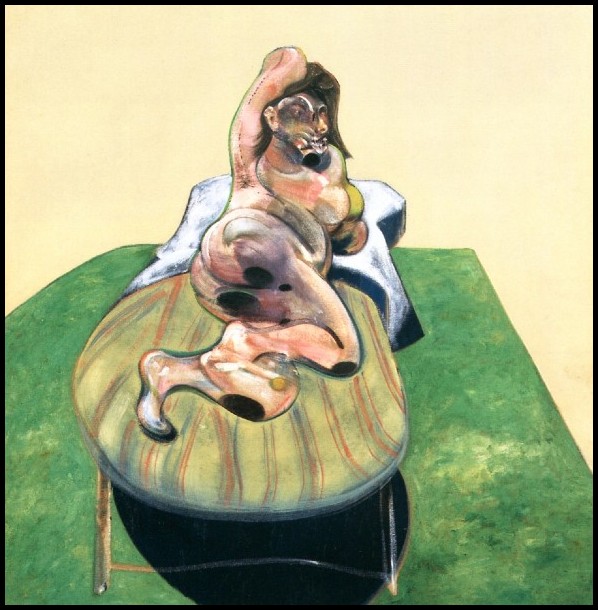

Francis Bacon, Study for Self-Portrait -Triptych (II), 1985-6

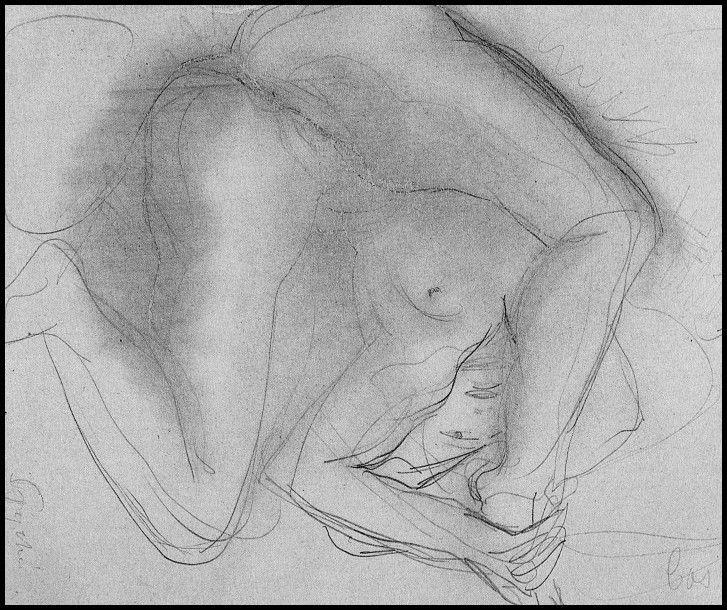

As in its original version as a short extract published by L’Arc in 1962, the first-person narrator-voyeuse of Homme assis sets out to describe the strange and violent sexual scene taking place before her between a man and woman left unnamed as lui and elle. The sadomasochistic ‘acts’ of the couple’s desire become progressively more extreme and je attempts to form an alliance with elle against lui and an unspecified on. This is not reciprocated, however, and so the narrator’s ambition to enter into the scene herself and direct it (e.g.: ‘What I desire is that she sees’) is never realized. Instead, her role is reduced to that of a passive spectator or go-between (‘I speak to her and tell her what the man is doing’), and she eventually falls victim herself to elle’s unbridled masochism and wish for ‘self-deformation’.

Francis Bacon, Lying Figure, 1969

There is no intertextual ‘screen’ here on which to project elle’s intensified anal and oral regression and so negotiate the increasing semantic confusion between elle (the lover), elle (her counterpart’s penis [‘la pine’]), and elle (his hand [‘la main’]), a confusion which runs parallel to elle’s fetid journey into ‘that other femininity’ of lui’s (ungendered) anus. From page 31 on, after the ‘lovers’ have experienced orgasm, Homme assis does no more than catalogue with silent fascination their slide into madness, leaving the narrator to conclude impotently: ‘I know nothing. I do not know if she is asleep’. The text, too, has ended up a ‘dead thing’.

Francis Bacon, Study for Self-Portrait -Triptych (III), 1985-86

Marcelle Marini [in ‘La mort d’une érotique’] has celebrated Homme assis as a subversion of the pornographic genre on account of its moments of pronominal ambiguity and its use of the conditional perfect. Yet what may initially have been a subversion of sexual identity on the level of the signifier (that a penis be ‘she’, for example, and thus elle’s desire for ‘elle’ be read as a daughter’s pre-Oedipal desire for the mother) is immediately nullified once the act of mechanical and ‘material’ consummation has taken place. An overwhelming literalness now takes over: ‘lèvres’ refers only to lips, not the vagina, and ‘la’ is linked only to one feminine noun, ‘la femme’.

Francis Bacon, Henrietta Moraes, 1966

Lacking what could be called a ‘genital’ process of metaphorical penetration, the text pursues its pre-Oedipal, metonymical movement of regression without offering any reformulation of lui’s ‘criminal’ penis: ‘It [elle] [her tongue] retains it [la] [his penis] which is on the point of being swallowed up in one continuous sucking movement’. Indeed, like elle with lui’s penis, ‘that vulgar and brutal thing’, Homme assis has choked on the punctiliously punctuated matter of its large typographical font. No poetic or rhetorical irony here, just a confirmatory repetition: ‘I see that nothing equals the power of this softness except the formal prohibiting of any injury to it. Prohibited’. The ‘dead point of the world’, intertextually passed over in Été, has now been fatally reached.

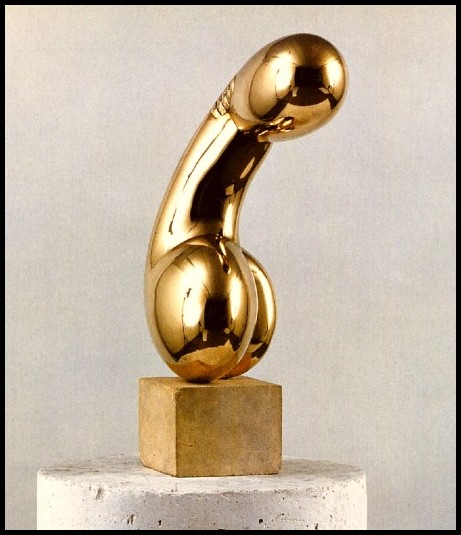

Brancusi, Princess X, 1915-16

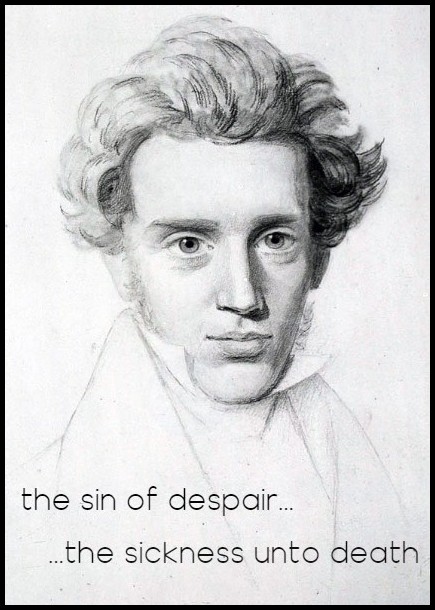

Maladie, published three years later, rectifies these structural faults in design and produces a very different sort of conclusion. Its formal address to vous corresponds to its transfer to an archetypal Great Man, Sören Kierkegaard, and his 1894 treatise, The Sickness unto Death (A Christian psychological exposition for upbuilding and awakening). Kierkegaard can sometimes appear completely self-sufficient and thus bar all intertextual access. This is not the case, however, in The Sickness unto Death. Indeed, its anatomy of the Christian sin of despair needs to be up-dated to the present day. Accordingly, Maladie redefines Man’s immaturity not as a lack of Christian belief but as a specifically sexual problem, that of one man’s fear of the female body, so great that it leads him into a state of regression, as exemplified by his retelling of boyhood tales and his homosexual love of the same (the grace of the bodies of the dead, the grace of those like yourself’).

Kierkegaard

Maladie stages a carefully prepared, dynamic climax. I am referring not to the moment of sexual consummation when vous’s initial oral desire to ‘drink’ elle’s breasts is remotivated into an act of penetration, but rather to the act of renaming whereby Kierkegaard is simultaneously capitalized and truncated. For once elle has delivered to vous her crucial instructions in heterosexual recognition and metaphor (the ‘hollow’ between her legs is the real ‘dark night’), and after this process has itself been replayed on the textual level through the multiple use of the verb reconnaître, the naming of vous’s sickness as ‘la maladie de la mort’ is re-executed hypervisibly, and Anti-Climactically, by the narrator as: ‘Maladie de la mort’. This unexpected but calm rupture of the textual surface by the discovery and transformation of an intertext is Maladie’s primary erotic moment.

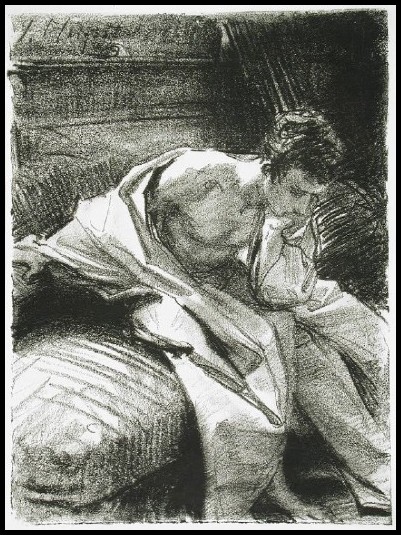

Rodin, drawing 6187

It is rounded off self-ironically in a generalizing, clichéd statement on the evanescence of love, the last part of which, significantly, is just one syllable short of becoming a perfect line of alexandrine verse: ‘… you have managed to live that love in the only way possible for you, losing it before it happened [en le perdant avant qu’il soit advenu]’.

J. S. Sargent, Study of a Young Man Seated, 1895

The delicate self-cutting and intertextual transmemberment in Maladie, which extends even to a dialogical space of narratorial doubt (‘And then you do it. I couldn’t say why’), constitutes a sublimation of the oral retention and anal fixation recorded so naïvely in Homme assis. Through its calculated use of single and double-sized blocks of white spacing, Maladie also creates calligraphically an erotic play of differentiation. Yet the intertextual act in Maladie represents above all else a ‘rebuilding’ of Kierkegaard since it reinstates dialectically a true Kierkegaardian sense of the potentialities of mastered, vertical irony and seduction displayed in other works by Kierkegaard such as Diary of a Seducer. The malady of homosexual non-loving, worse even than Kierkegaardian despair in the sense that there is no life left to die from, is played off hyperbolically as a playable and repeatable element, i.e. as simply ‘the sickness of living, wickedness, the devil’.

Kierkegaard

Indeed, it is the text of Maladie itself, rather than its male or female protagonist, which acquires the deliverance and self-reflexiveness usually accorded to Kierkegaardian consciousness and selfhood. Its textual ‘accidents’ allow it to transcend both the ‘sickness of death’ and elle’s body, offered as the sign of sexuality itself. Elle’s careful and emphatic distinction during her lesson on love between ‘accident’ (or ‘mistake’) and ‘will’ is effectively dismissed, the two concepts being fused together on a different level in a textual fantasy of formation and controlled deformation. Moreover, elle’s ‘buried sex’, which ‘swallows up’ and ‘holds’ without appearing to do so, functions less as an object in itself than as a metaphor for the textual process, i.e. the swallowing up and holding down by Maladie of its intertextual filter, reflected in the ‘filtered green’ of ‘elle’s eyes.

Rodin, drawing 5411

Maladie’s use of its ‘lacking’ intertext also confronts us directly with the reality of our own position as reader. By exposing first its projective identification with, then introjection and final reprojection of, the ‘bad’ intertext now made magically ‘good’, it brings us to a stunning recognition of our own critical ‘fading’. This happens only after the text has energetically tapped the libidinal basis of our Wisstrieb [instinct for knowledge or research] daring us, like elle’s slender body ‘crying out’ to be strangled and raped, to assume the aggressive and penetrative role of interpreter. The same is equally true, of course, of Amant, whose ideal male readers are portrayed by Duras as having a centuries-old desire for incest and rape. What this means in practice is that ‘he’ is often ‘put right’ even when not ‘in error’. For example, the narrator of Amant notifies the reader for no apparent reason that ‘he’ has been misled, that it was not, after all, at the cantine in Réam that she met the Chinese but two or three years later, after the concession had been abandoned. Such gifts of surplus information demand that we read Amant and Maladie as intertextual revisions not simply of Duras’s previous work but, more profoundly, of ourselves as ‘faulty’ readers.

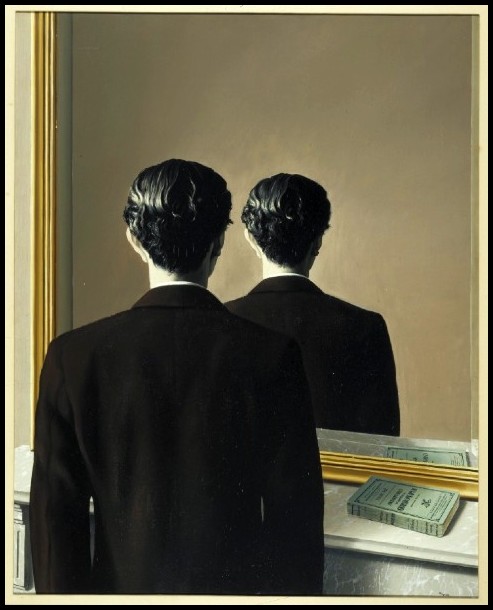

Magritte, Reproduction interdite, 1937

For if we are solicited to take part in the telling of legendary stories (‘Look at me, on the ferry’), we are also quickly cut short by Duras’s corrective impulse. Such a position refutes the author’s view of Amant as a ‘constant, unending metonymy which never “cuts out” the reader, or takes his place’, although Duras does admit elsewhere that ‘Amant is a book which acts upon the reader’. We ‘exist’ in écriture courante by default, being simultaneously drawn in, drawn up, and beheaded in order for a sublime moment of intertextual re-crossing to snap the Duras text back into ironic life. That shock, at the moment of apocalyptic unveiling, when the reread intertext is finally released, is the text’s ‘properly’ erotic moment and another tangible instance of Duras’s desired ‘hygienic orgasm’. We have become no more than an ‘immediate’ reader of ‘monitor’ screens, the personification of a provisional intertextual construction always to be corrected and even relegated as an inverted mirror image. ‘Scandalous’ the Duras Minuit text may be but only because it has chosen to market itself under the misleading label of écriture courante.

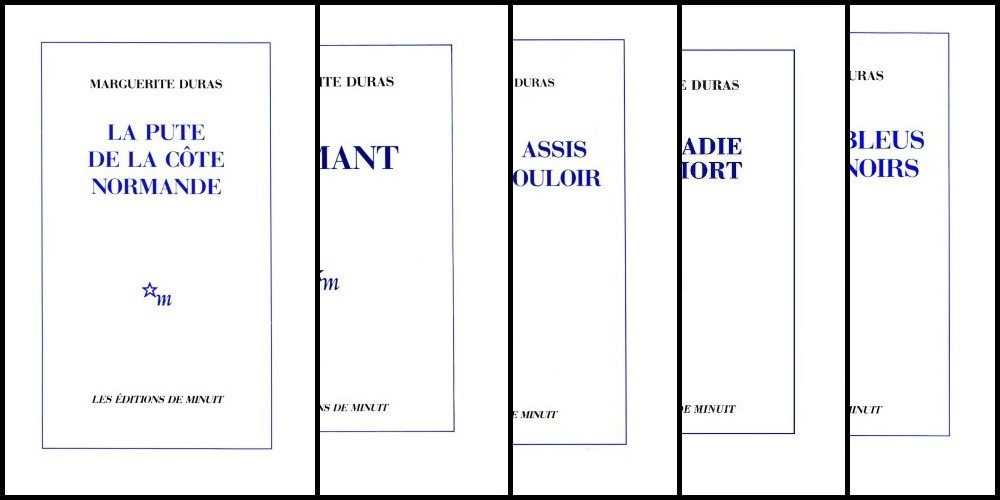

Marguerite Duras at Éditions de Minuit

JAMES S. WILLIAMS: THREE RECENT BOOKS

Contemporary French Cinema | Contemporary African Cinema | Encounters with Godard

JAMES S. WILLIAMS: THREE EARLIER BOOKS

Jean Cocteau: Cinema | Jean Cocteau: Biography | Duras: The Erotics of Passage

A RESONANCE OF DURAS IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 7

The radiance of the morning can’t eclipse the brilliance of the night, the whiteness of the swans can’t outshine the blackness of your art: With exquisite subtlety you made me come without touching me. How did you do it? As the swans fly in formation, as the air scintillates in the sun, let me linger in the ravishment you staged in our room.

Turner, Landscape, c.1845

You were no cliché of a Salomé, no decadent daughter of Herodias; you did no dance of the seven veils, you asked for no head on a platter: With your eyes alone you did it. Naked, my hands tied above my head to a post of the bed, I stood before you as you sat on a roller chair, dévoré flowers tumbling down the folds of your kimono. Afloat on the floor, your feet slowly wheeling you to me, in turn you stared into my eyes and fixed your gaze on my cock. (How did you find that rhythm in the shift, that rhythm that maintained such tension?)

Gustave Moreau, L’Apparition, 1876

I envisioned myself as Saint Sebastian, until the onslaught of your eyes made me an ecstatic pagan. When your gaze held mine I felt myself in freefall; when you stared at my sex, the Cyclops stared back. The parting of your lips raced my heart, the tilting of your head stayed my breath. You made my cock the very core of my being – I became that blood-throb that knows no bounds. At the end of my tether, desperate for your touch, I felt a firebrand in my hand: the chafing of the rope on my wrists. And the light? The light came from your eyes, burning your beauty into the depths of me, inviting me to defile it. I felt my tendons tightening, myself in command of nothing. Cupping your hands before my craving, with the flaming amber of your eyes you licked me: In the intensity of your regard I delivered my elixir, in the rapture of your look I dissolved into darkness…

Guido Reni, Saint Sebastian, 1615