Susan Sontag

The Pornographic Imagination

SUSAN SONTAG: SEVEN THESES FROM ‘THE PORNOGRAPHIC IMAGINATION’

From Styles of Radical Will (Penguin Classics, 2009; originally published in 1969)

THESIS ONE

The pornographic imagination has its peculiar access to some truth. This truth—about sensibility, about sex, about individual personality, about despair, about limits—can be shared when it projects itself into art.

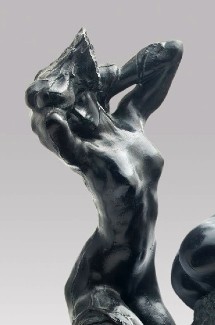

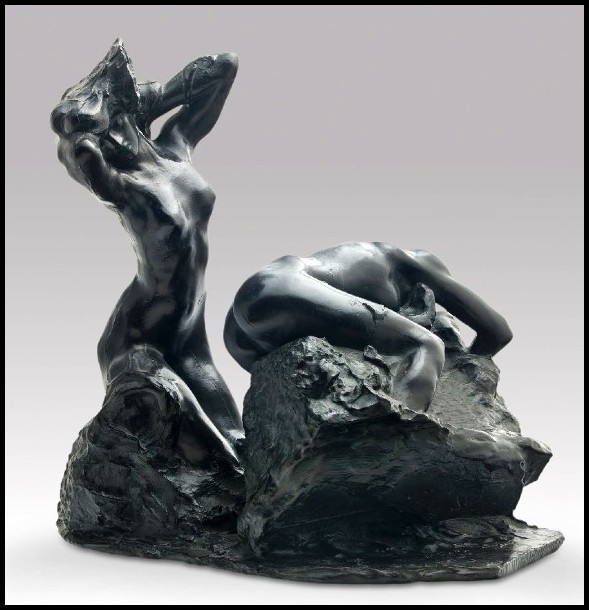

Rodin, Toilette of Venus and Andromeda, c.1886

THESIS TWO

Everyone, at least in dreams, has inhabited the world of the pornographic imagination for some hours or days or even longer periods of his life; but only the full-time residents make the fetishes, the trophies, the art.

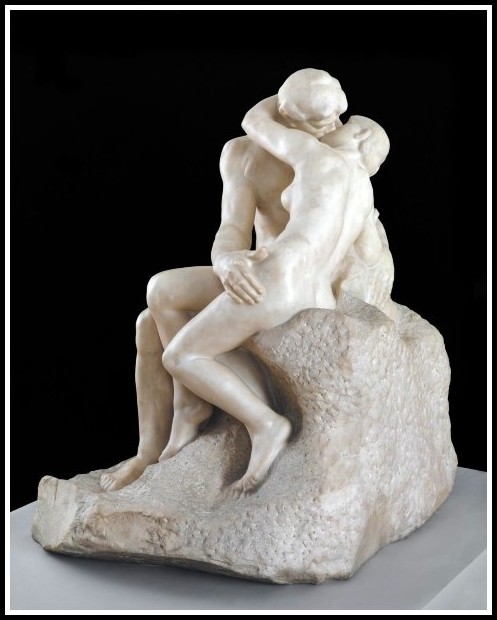

Rodin, The Kiss, 1901-04

THESIS THREE

That discourse one might call the poetry of transgression is also knowledge. He who transgresses not only breaks a rule. He goes somewhere that the others are not; and he knows something the others don’t know.

Rodin, Eternal Spring, 1889

THESIS FOUR

There is, demonstrably, something incorrectly designed and potentially disorienting in the human sexual capacity—at least in the capacities of man-in-civilization. Man, the sick animal, bears within him an appetite which can drive him mad.

Rodin, The Eternal Idol, 1893

THESIS FIVE

Such is the understanding of sexuality—as something beyond good and evil, beyond love, beyond sanity; as a resource for ordeal and for breaking through the limits of consciousness—that informs the French literary canon [Histoire de l’œil and Histoire d’O, among others] I’ve been discussing.

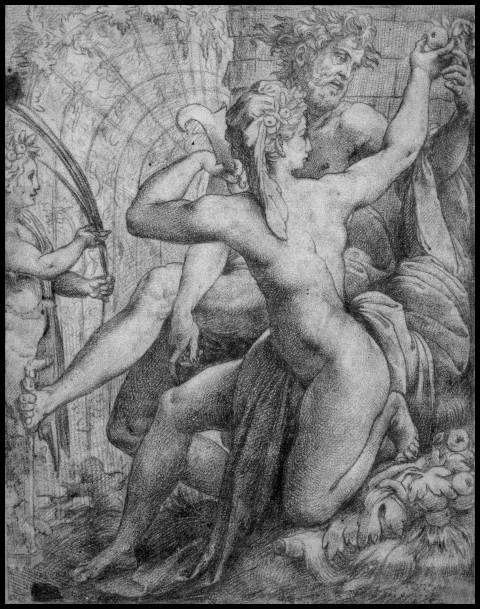

Perino del Vaga, Vertumnus and Pomona, c.1530

THESIS SIX

There’s a sense in which all knowledge is dangerous, the reason being that not everyone is in the same condition as knowers or potential knowers. Perhaps most people don’t need ‘a wider scale of experience’. It may be that, without subtle and extensive psychic preparation, any widening of experience and consciousness is destructive for most people.

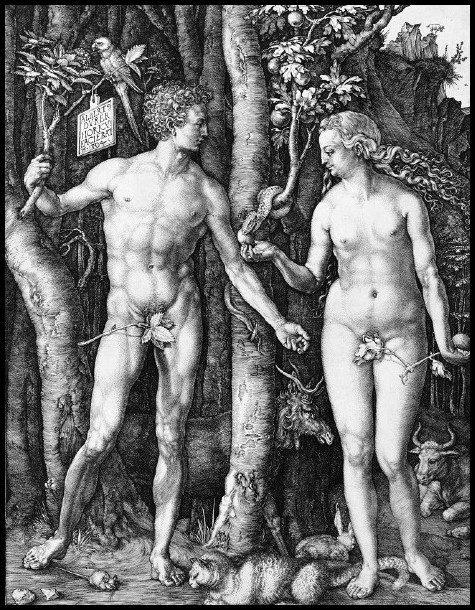

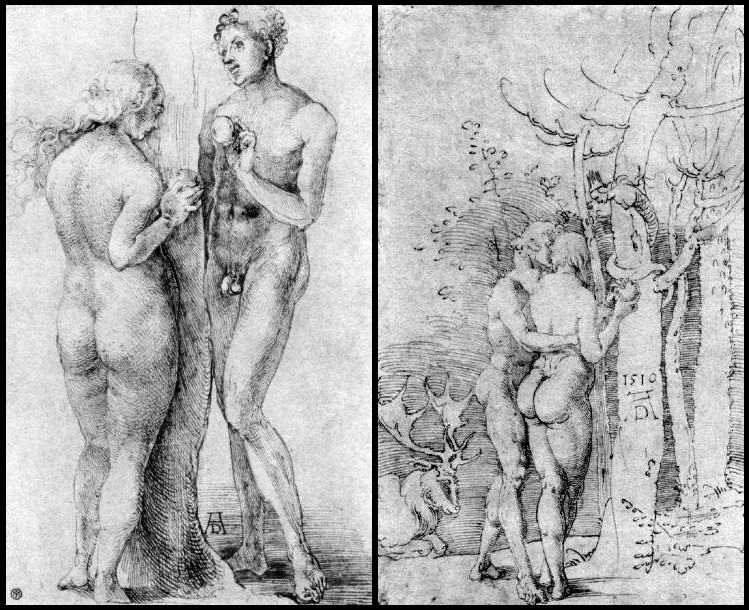

Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1504

THESIS SEVEN

In the last analysis, the place we assign to pornography depends on the goals we set for our own consciousness, our own experience.

Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1495 | Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1510

SUSAN SONTAG: THREE BOOKS

A REVERBERATION OF SUSAN SONTAG IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 4

̶ Have you ever felt ashamed, Sprague? About sex, I mean.

̶ No, never. Have you?

̶ Yes. I went through a really bad patch at thirteen-and-a-half, fourteen.

̶ After that incident with Dédé?

̶ Yes. I just couldn’t cope with my body.

As the guitar threads its way through the texture of reeds, the flute devises traps for feeling.

̶ Your body escaped you, so to speak?

̶ Completely! It’s effects were out of my control.

Is it the quiet fire of the torch ballad that’s giving my tea this scintillation?

̶ It’s strange, how the baggage you think you’ve jettisoned can suddenly resurface. I think I’ve touched all the extremes.

̶ In sex, you mean?

̶ Yes. And sometimes in a single night!

Edvard Munch, Puberty, 1894-95

Vigil lights flicker, the city sleeps; in harmony with the elemental river, the elliptical music flows.

̶ What do you think? Can one ever really get rid of one’s baggage?

̶ No, I’d say not.

̶ I’d like to get rid of mine. It’s just too heavy sometimes!

Your hair in the light is pale blonde, the colour of a corn tassel; in the shadows the ambers of your eyes shine.

̶ You know, Marietta, a lot of women who seem so free with their bodies are simply caught up in a cycle of repetition. They’ve stopped growing, and instead of changing their lives, they wrap their sterility in a semblance of freedom. They forget their responsibility to themselves.

̶ What are you getting at?

̶ That even the lightest of travellers can bring heavy baggage to bed.

̶ It’s not easy, is it?

̶ No.

You sip your tea.

̶ And yet, there was a time when it was easy.

Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1895

Holding your cup, your fingers manifest the dignity of your hand.

̶ With Marco?

̶ No. Jürgen. He was a fantastic lover. Everything was happening for the first time, but somehow I knew exactly what to do—my instinct was infallible.

̶ You were… what? Sixteen, seventeen?

̶ Fifteen, almost sixteen.

̶ And then you met Marco?

̶ Yes. Suddenly there was love, and sex became complicated. After he died things changed drastically. Out of the blue, I found it difficult to accept being penetrated by a man. It’s something you submit to, after all. It’s a kind of responsibility. And then, to accept that a man sees you come, to accept that he makes you come, that’s the highest degree of intimacy. To accept that is to accept everything. Well, at fifteen it was easy. At seventeen, it was impossible!

Edvard Munch, Ashes, 1894

Mercurial, responsive, revelling in its capacity to experience changes of form, the river absorbs my emotion.

̶ We are what we remember, Marietta.

̶ But why at the most unexpected moments? Complicated, isn’t it?

̶ Put things in perspective—think of the millipede.

̶ The millipede?

̶ Yes. On his wedding night, a millipede said to his bride, ‘Darling, I know this night is special; it’s the first time for both of us, and I want to do things right. But we’ve both had a long, tiring day, so why don’t you just take off your stockings yourself and tell me which legs I should spread?’.

Your teacup rattles in its saucer; shakily, you set it on the table then slap your thigh, doubling over in laughter.

Edvard Munch, The Voice (Summer Night), 1896

Air is the element of acquiescence, transparent and insubstantial: In the daring glass of the glazing, floating in luminous black, the white roses and Peruvian lilies affirm me in my resolution: For you I will redouble the energy of delusion, for you I will sacrifice drugs and sleep: You are inexhaustible, and everything is mine to learn.

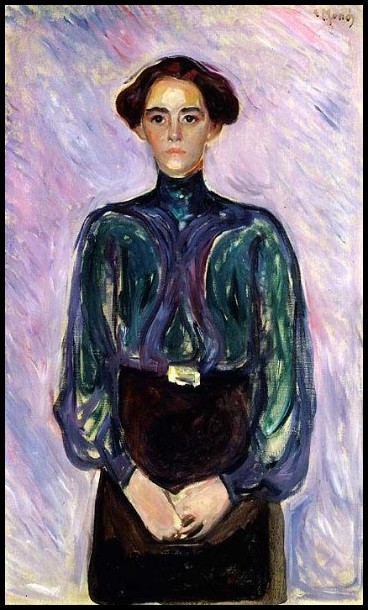

Edvard Munch, Mrs. Schwarz, 1906