Fiona Apple, 1999 | Photos: Eric Mulet

FIONA APPLE: TEN SONGS, TEN ECHOES (PART 1 OF 2)

TEN FIONA APPLE SONGS THROUGH THE PRISM OF TEN SONGS BY OTHER ARTISTS

Richard Jonathan

In this post I endeavor to offer a deeper appreciation of Fiona Apple’s songs by taking a detour

through songs by David Bowie, Magazine, Joy Division, Pete Townshend and The Cure (in Part 1),

and Garbage, Bob Dylan, Liz Phair, Leonard Cohen and Tanita Tikaram (in Part 2).

Fiona Apple, 1999 | Photo: Eric Mulet

INTRODUCTION

I could say Fiona Apple is the Sappho of the erotic lyric, I could say she is the Nietzsche of song; I could say Fiona Apple is the Rimbaud of poetic revenge, I could say she is the Kate Moss of music; I could say Fiona Apple is the Miles Davis of defiant dignity, I could say she is the Erik Satie of irony. I could, yes—but no, I won’t. I won’t say any of that. Why not? The fact of the matter, dear reader, is that Fiona Apple simply is. She fully assumes her singularity, and takes full responsibility for it: however fine a mesh of discursive discourse one may weave, it can never capture her soul, that locus of negativity, that capacity to say No, that founds her freedom and constitutes her individuality. If, in the domain of popular music, that is not unique, it is nevertheless rare. (Other names that come to mind, in this regard, are Laura Nyro, David Bowie, and Tom Verlaine.)

Fiona Apple, 1999 | Photo: Eric Mulet

To bare one’s soul, more often than not, comes across as embarrassing. The songwriter who refuses self-censorship, who refuses to put water in their wine, has several means at their disposal to forestall embarrassment. The most common are a set of distancing devices, ways of inserting an intermediary between performer and listener. Using the third person instead of the first or second—saying ‘he’ and/or ‘she’ instead of ‘I’ and/or ‘you’—is a frequently employed device, but one that Fiona Apple never (almost never) uses. Of the 55 songs on her 5 albums, all but one half of one song—’For Her’ on Fetch the Bolt Cutters—are in the ‘I’ and/or ‘you’ voices. This fact alone shows the extent to which Fiona puts herself on the line: she is a high-wire walker with no safety net, a tumbling acrobat on a bare floor. How, then, does she avoid the pitfall of embarrassment when she ‘bares her soul’?

The trick, one might think, is to do what painters do: turn the ‘naked’ into the ‘nude’, find a lyrical equivalent for lover/self-as-mythological-being, lover/self-set-in-a-historical-scene, lover/self-as-a-pretext-for-abstraction. This is what Springsteen does with his backstreet misfits, Bryan Ferry with his jaded-but-sensitive romantic persona, Heather Nova with her foregrounding of the feminine. But it is not what Fiona Apple does. Indeed, never, in any of her 55 songs, does she adopt this trick; always, she prefers the naked to the nude, direct address to disguise. This fact, too, shows the extent to which she puts herself on the line: her figures of speech have flesh and blood, her masks bear the mould of the bare face. So just how, then, does she avoid embarrassment when she ‘bares her soul’?

Intelligence, organic form, conviction; attitude, self-belief, derision: these six terms, I maintain, capture much of how Fiona, despite foregoing the classic distancing devices of third-person voice and nude-over-naked, manages to ‘bare her soul’ without embarrassment, and does so across the entirety of her work, with no lapses in artistic integrity. Adopting a comparative approach, I will argue this thesis in my discussion of the songs that follows*. By taking a detour through other artists’ songs, I hope to gain access to the core of Fiona’s.

* For each pair of songs, following the discussion, you will find a Spotify player and the lyrics.

I. FIONA APPLE: TO YOUR LOVE | DAVID BOWIE: STAY

On hearing ‘To Your Love’ and ’Stay’, one is immediately struck by the conviction and authority they convey. ‘Stay’ develops organically from a guitar riff that stops you dead in your tracks and compels your attention, while ‘To Your Love’ captures you out of the gate in its reticulate rhythm, its seductive web of contradiction: at once relaxed and intense, loose and tight, spacious and dense. In both songs the lyric—against the immediacy of the music, against its robust embrace—asserts a sense of doubt: into the music’s muscularity the lyric injects a note of vulnerability. Hesitancy is the stance of ‘Stay’: ‘maybe… hope… what I meant to say… you can never really tell… life is so vague… this time tomorrow I’ll know…’, while ‘Please forgive me for my distance’ is a recurring line in the refrain of ‘To Your Love’, which concludes with a request to end indecision: ‘And now you, so now you have it, so tell me baby what’s the word? Am I your gal, or should I get out of town? I just need to be reassured.’ The ‘decisiveness’ of the music, then, collides with the ‘indecisiveness’ expressed by the words, and it is this clash that confers on the songs their distinctive ‘attitude’: both the Bowie and the Fiona characters refuse to abase themselves by begging, both show dignity and pride in their pleading. In both songwriters, again, this attitude comes across as ‘cool’: for Bowie, the cool of the ‘thin white duke’; for Fiona, the cool of one who’s got a reserve of ‘fuck you’s on her tongue, ready to be delivered at the least provocation.

Lyrically, a clear difference between the two songs is that while both reflect on a refusal to go further with an encounter (Bowie) or a relationship (Apple), ‘Stay’ is solipsistic and ‘To Your Love’ is dialogical. The Bowie character is talking to himself, reflecting on the fact that he did not act, that he refused an opportunity for relation. The Fiona character, already in a relationship, is addressing her would-be lover: conquer me or let me go, show me your stuff or get stuffed: the status quo is untenable. Fiona wants day or night, not twilight; hot or cold, not lukewarm. She demands not only celebration of her individuality, but also opportunities for risk-taking: she cannot love a man around whom she can ‘dance the rigadoon’. She dares the man to rise to the occasion: ‘Do you just deal it out or can you deal with what I lay down?’ Could it be the case that for men an intimate relationship is less often the prime vehicle for self-affirmation than it is for women? If so, that would account for Bowie’s detached steeliness and Fiona’s ambivalent derision.

TO YOUR LOVE

Fiona Apple, ‘When the Pawn’, 1999

Here’s another speech you wish I’d swallow

Another cue for you to fold your ears

Another train of thought too hard to follow

Chugging along to the song that belongs to the shifting of gears

Please forgive me for my distance

The pain is evident in my existence

Please forgive for my distance

The shame is manifest in my resistance

To your love, to your love, to your love

I would’ve warned you, but really what’s the point?

Caution could but rarely ever helps

Don’t be down when my demeanor tends to disappoint

It’s hard enough even trying to be civil to myself

Please forgive me for my distance

The pain is evident in my existence

Please forgive for my distance

The shame is manifest in my resistance

To your love, to your love, to your love

My derring-do allows me to dance the rigadoon around you

But by the time I’m close to you I lose my desideratum

And now you, so now you have it, so tell me baby what’s the word?

Am I your gal, or should I get out of town?

I just need to be reassured

Do you just deal it out or can you deal with what I lay down?

Please forgive me for my distance

The pain is evident in my existence

Please forgive me for my distance

The shame is manifest in my resistance

To your love, to your love, to your love

STAY

David Bowie, ‘Station to Station’, 1976

This week dragged past me so slowly

The days fell on their knees

Maybe I’ll take something to help me

Hope someone takes after me

I guess there’s always some change in the weather

This time I know we could get it together

If I did casually mention tonight

That would be crazy tonight

Stay! That’s what I meant to say, or do something

But what I never say is, stay, this time

I really meant to so badly this time

‘Cause you can never really tell

When somebody wants something you want too

Heartbreaker, heartbreaker, make me delight

Life is so vague when it brings someone new

This time tomorrow I’ll know what to do

I know it’s happened to you

Stay! That’s what I meant to say, or do something

But what I never say is, stay, this time

I really meant to so badly this time

‘Cause you can never really tell

When somebody wants so much too

II. FIONA APPLE: OH WELL | MAGAZINE: YOU NEVER KNEW ME

Lyrically, ‘Oh Well’ is uncharacteristic of Fiona Apple in that it construes the betrayed lover as passive victim, a woman without agency, reduced to impotent suffering. ‘What you did to me’: from the get-go, things are black and white: he acts, she is acted upon. Even in the most extreme situations, however, human agency can never be cancelled out. Sartre put it this way: ‘You are what you make of what others have made of you.’ Out of what has been done to her, the heroine of ‘Oh Well’ makes herself ‘something awful’. Her feeling is thus in bad faith. Moreover, she is hypocritical: her love is conditional on fidelity, yet she speaks of her ‘unconditional love’. No need to call on the insights of anthropology and argue that monogamy is unnatural: Fiona herself says as much in ‘Cosmonauts’: ‘Your face ignites a fuse to my patience, whatever you do is gonna be wrong’.

And for the dimwits who don’t get it, she spells it out in her April 2020 interview with Vulture: ‘Some people are made for it [monogamy] and some people aren’t’ and ‘I don’t know if I want to be together with anybody forever’. That the heart contradicts reason is of course what makes us different from machines, however extraordinary. It is because, I suspect, the infidelity caught the lover in a particularly vulnerable state (‘I was feeding on the need for you to know me’) that she felt the sting of infidelity so intensely. Listen again to ‘Sleep to Dream’, ‘Limp’, ‘Fast as You Can’ and ‘Get Gone’ and recognize that ‘meek and muffled’ and ‘peace and quiet’ are atypical stations in Fiona’s journey of the heart. And for other responses by women musicians to their lover’s infidelity, listen to Marianne Faithfull’s ‘Why’d Ya Do It?’* (lyrics by Heathcote Williams) and Joni Mitchell’s ‘Woman of Heart and Mind’.

* While the word ‘fuck(ing)’ occurs frequently in Fiona Apple’s lyrics, it is always used as invective or fuel to the fire, never in reference to the sexual act. Might this have something to do with the fact that the poet is American, working in a culture still mired in sexual Puritanism? See my posts on Vanessa Redgrave in ‘The Devils’, a film that holds a mirror to America today.

‘Oh what a cold and a common low way to go / When I was feeding on the need for you to know me / Devastated at the rate you fell below me’: the final verse, in particular, of ‘Oh Well’ echoes Magazine’s ‘You Never Knew Me’ (lyrics by Howard Devoto). While ‘Oh Well’ foregrounds the betrayal that brought the romance down to earth and ‘You Never Knew Me’ focuses on a relationship that never really got off the ground (‘We had to kill too much before we could even kiss’), both songs highlight the notion of love as recognition (what Martin Buber calls the ‘I-Thou’ relation). ‘I was feeding on the need for you to know me’, Fiona sings, referring, perhaps, to the longed-for feeling of being ‘settled’ that arises when the gaze of the other returns an image of oneself in harmony with one’s own self-image. The hero of the Magazine song, for his part, is far from ‘settled’: ‘I don’t want to turn around and find I’d got it wrong’, he sings, while ‘We get back, I bleed into you’ suggests his insecurity is ontological. In a gesture of resistance, he adds: ‘I’m sorry I can’t be cancelled out like this’.

While both Apple (‘devastated at the rate you fell below me’) and Devoto (‘all of that’s behind me now still seems to be above you’) assert their superiority over the unfaithful/departed lover, only the Fiona character, content with expressing anger and regret (‘what wasted unconditional love’) refuses to intellectualize her suffering. Indeed, the Devoto character lacks the humility to frankly express his hurt; to hide it, he gets on his high horse and sings, ‘Do you want the truth or do you want your sanity?’ and ‘You think you’ve understood, you’re ignorant that way’. Having expressed her anger and hurt, Fiona ends her song with a resigned, ‘Oh well’: the relationship is over, and I’ll get over it. Devoto, however, having declared ‘Thank God that I don’t love you’, finally dismounts his high horse and sings, ‘You never knew me – Do you want to?’. Yes, he still loves her, but his love appears to be more neurotic than nourishing: ‘You’re what keeps me alive, you’re what’s destroying me’. Both songs elicit pathos as well as a touch of the pathetic: ‘You Never Knew Me’ because of its attempt to intellectualize emotional pain (a typically masculine stratagem) and ‘Oh Well’ because of its bad faith (a typically feminine stratagem).

OH WELL

Fiona Apple, ‘Extraordinary Machine’, 2005

What you did to me made me see myself something different

Though I try to talk sense to myself but I just won’t listen

Won’t you go away, turn yourself in, you’re no good at confession

Before the image that you burned me in tries to teach you a lesson

What you did to me made me see myself something awful

A voice once stentorian is now again meek and muffled

It took me such a long time to get back up the first time you did it

I spent all I had to get it back and now it seems I’ve been outbidded

My peace and quiet was stolen from me

When I was looking with calm affection you were searching out my imperfections

What wasted unconditional love

On somebody who doesn’t believe in the stuff

You came upon me like a hypnic jerk when I was just about settled

And when it counts you recoil with a cryptic word and leave a love belittled

Oh what a cold and a common low way to go

When I was feeding on the need for you to know me

Devastated at the rate you fell below me

What wasted unconditional love

On somebody who doesn’t believe in the stuff

Oh, well

YOU NEVER KNEW ME

Magazine, ‘The Correct Use of Soap’, 1980

I don’t want to turn around and find I’d got it wrong

Or that I should have been laughing all along

You’re what keeps me alive

You’re what’s destroying me

Do you want the truth or do you want your sanity?

You were hell and everything else was just a mess

I found I’d stepped into the deepest unhappiness

We get back, I bleed into you

Thank God that I don’t love you

All of that’s behind me now still seems to be above you

I don’t know

You never knew

I don’t know whether I ever knew you

You never knew

But I know you

I know you never knew me

Do you want to?

Hope doesn’t serve me now, I don’t move fast at all these days

You think you’ve understood, you’re ignorant that way

I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry

I’m sorry I can’t be cancelled out like this

We had to kill too much before we could even kiss

I don’t know

You never knew

I don’t know whether I ever knew you

You never knew

But I know you

I know you never knew me

Do you want to?

Marianne Faithfull, ‘Why’d Ya Do It?’

Joni Mitchell, ‘Woman of Heart and Mind’

III. FIONA APPLE: NEVER IS A PROMISE | JOY DIVISION: LOVE WILL TEAR US APART

‘Is this a lasting treasure or just a moment’s pleasure?’, Carole King writes in ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow?’*. ‘Tonight with words unspoken you say that I’m the only one’, she continues, ‘but will my heart be broken when the night meets the morning sun?’. Writing in her journal of a similar experience, Fiona Apple wrote the lyric of ‘Never Is a Promise’. That the poignant simplicity of ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow?’ and the touching sophistication of ‘Never Is a Promise’ spring from the same prompt gives the measure of Fiona Apple’s ability to filter emotion through intelligence and sensibility to produce lyrical art of the highest order.

* Bryan Ferry’s version shows how effectively the lyrics can still be delivered.

‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ is a station down the line from ‘Never Is a Promise’ (which, for its part, is down the line from ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow?’). Fiona’s song breathes forth a freshness tinged with nostalgia; experience overcomes innocence as girl becomes woman. For the heroine, the future is open, the horizon visible, even if ‘shades and shadows undulate in [her] perception’. Her feelings ‘swell and stretch’, she sees ‘from greater heights’, and even if she doesn’t ‘know what to believe in’, her ‘courage’, the ‘heat of [her] soul’, her ‘understanding’ of what she is ‘too proud’ or ‘too smart’ to mention, will, we sense, see her through: when this relationship is over, she will find a world elsewhere. In contrast, in ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, not only is what was once fresh now stale, but the future is foreclosed: nowhere is elsewhere, elsewhere is nowhere: there is no horizon. Indeed, Ian Curtis, the 23-year old lyricist, killed himself within weeks of recording the song.

The impasse in Curtis’ marriage, his inability to leave his wife and start a new life with his lover, was certainly a factor in his suicide. Everyone who’s been in a couple has experienced the lyrics of ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’, but very few have killed themselves in consequence: the distribution of ‘precipitating factors’ is highly variable. Twenty-year old Fiona Apple had this to say on the matter: ‘I’m underwater most of the time, and music is like a tube to the surface that I can breathe through. It’s my air hole up to the world. If I didn’t have the music I’d be under water, dead.’ (Spin, Nov 1997) ‘Never Is a Promise’ is but the first of Fiona’s songs that served her as a ‘tube to the surface’: many more would follow. By age forty-two, she had reached a point where she could declare: ‘There’s absolutely hope that I could find a relationship. But I don’t really want to. I really just don’t want to. I like my life how it is, and I don’t feel very romantic these days.’ (Vulture, 17 April 2020).

Many of Fiona’s songs address the breakup of a relationship, from the precocious maturity of ‘Never Is a Promise’ to the just-shy-of-jaded ‘Drumset’. The theme, of course, is a pop song staple; innumerable writers have wiped their boots on it, which is why it is so threadbare. Fiona, for her part, combines discernment and sensibility, frankness and wit, to bring a depth to it. There’s depth, too, in Ian Curtis’ lyric, but unlike Fiona, he was not able to use his music as an ‘air hole up to the world’.

FRANCO LA CECLA: ‘Why don’t we accept the idea that separation is a constitutive aspect of love itself? Why has our culture never made of the provisional a blessing, a fidelity to life and its metamorphoses? Why can’t we undo our ties without becoming undone? A talent for abandoning things, as psychoanalysis has shown, is a prerequisite to living a healthy life.’

If La Cecla’s ‘loving break-up’ were to become more common, we’d have fewer desperately sad people—and fewer great songs.

Franco La Cecla, Je te quitte, moi non plus, ou l’art de la rupture amoureuse. French translation from the Italian by Eliane Deschamps-Pria (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 2004) p. 98, p. 100, p. 166, p. 152. Translated here from the French by Richard Jonathan. Franco La Cecla is an Italian anthropologist.

NEVER IS A PROMISE

Fiona Apple, Tidal, 1996

You’ll never see the courage I know

Its colors’ richness won’t appear within your view

I’ll never glow the way that you glow

Your presence dominates the judgements made on you

But as the scenery grows, I see in different lights

The shades and shadows undulate in my perception

My feelings swell and stretch, I see from greater heights

I understand what I am still too proud to mention to you

You’ll say you understand, but you don’t understand

You’ll say you’d never give up seeing eye to eye

But never is a promise and you can’t afford to lie

You’ll never touch these things that I hold

The skin of my emotions lies beneath my own

You’ll never feel the heat of this soul

My fever burns me deeper than I’ve ever shown to you

You’ll say, don’t fear your dreams, it’s easier than it seems

You’ll say you’d never let me fall from hopes so high

But never is a promise and you can’t afford to lie

You’ll never live this life that I live

I’ll never live the life that wakes me in the night

You’ll never hear the message I give

You’ll say it looks as though I might give up this fight

But as the scenery grows, I see in different lights

The shades and shadows undulate in my perception

My feelings swell and stretch, I see from greater heights

I realize what I am now too smart to mention to you

You’ll say you understand, you’ll never understand

I’ll say I’ll never wake up knowing how or why

I don’t know what to believe in, you don’t know who I am

You’ll say I need appeasing when I start to cry

But never is a promise and I’ll never need a lie

LOVE WILL TEAR US APART

Joy Division, 1980

When routine bites hard and ambitions are low

And resentment rides high but emotions won’t grow

And we’re changing our ways, taking different roads

Love, love will tear us apart again

Why is the bedroom so cold, turned away on your side?

Is my timing that flawed, our respect run so dry?

Yet there’s still this appeal that we’ve kept through our lives

Love, love will tear us apart again

Do you cry out in your sleep, all my failings exposed?

Get a taste in my mouth as desperation takes hold

Is it something so good just can’t function no more?

But love, love will tear us apart again

Love, love will tear us apart again

Bryan Ferry, ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow?’

IV. FIONA APPLE: LEFT ALONE | PETE TOWNSHEND: A LITTLE IS ENOUGH

Having ‘cultivated a callus’ since the end of the relationship she’d entered as a ‘dewy petal’ and left as a ‘moribund slut’, the heroine of ‘Left Alone’ declares: ‘I’m hard, too hard to know’. Why her love ‘wrecked’ her beloved we don’t know, but we do know that when he left it ‘hurt more than it ought to hurt’. Now when she’s sad she doesn’t cry, but fears arise when her tears ‘calcify’. ‘How can I ask anyone to love me’, she wonders, ‘when all I do is beg to be left alone?’. Are these just the vicissitudes of love, an expression of an understandable despondency, or is there something more here? ‘I can love the same man in the same bed in the same city, but not in the same room’, she laments. ‘Same man’: a relationship. ‘Same bed’: a sexual relationship. ‘Same city’: neutral ground. ‘Same room’: personal space—the ground of emotional intimacy, of love or its refusal, of interpersonal boundaries. And yet, because the guy’s worth it (‘this guy, what a guy’), the heroine tries to love. Could the problem be that she tries too hard? Could it be that she’s too much of a bee and not enough of a flower?

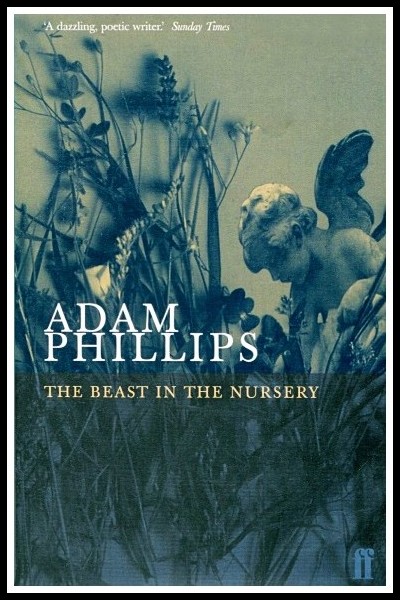

In this regard, consider these reflections from British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips:

It is better to be a flower than a bee: the bee is busy with intentions, it is harassed by its aims, whereas the flower is receptive, it is open to every insect that favors it with a visit. The flower can take a hint.

The most important things just happen to you. We are profoundly unconscious of who we are—or what we might be moved by—and of what we might become. We are unconscious of where our affinities, our psychic affiliations, might come from, and where they might lead us. Like a cue, each hint taken furthers the drama; but the play is not one we can know.

The good hint is always in the eye of the one who takes it. And these hints are freely taken in the sense that they are not felt as compromising, but as a kind of release. How could anyone know, least of all you, what will really work on you? You can acquire a sense of what turns you on—indeed, you might be in too much of a hurry to find out—but you can still be surprised. The fear of pleasure can blind one to its prompts.

Adam Phillips, The Beast in the Nursery (London, Faber & Faber, 1998) pp. 67-73

Adam Phillips, The Beast in the Nursery

The hero of Pete Townshend’s ‘A Little Is Enough’ is more flower than bee. ‘You give me an overdose of love’ he declares, ‘but just a little is a enough’. Partaking of the mystic, he knows that ‘love often passes in a second’, but in that second ‘eternity may beckon’. Just as the contact of a single oyster, singularly felt, procures no less pleasure than a plateful; just as the perfume of champagne cognac, receptively received, is hardly less satisfying than the taste, ‘a smile sets [him] reeling, a kiss feels like stealing’. Without ‘trying to love’—’All I have to have’s a little time with you’—Townshend-the-flower finds, like the mystics (in his case, Meher Baba) the truth of his ‘empty glass’: the cup dissolves, but the cupful remains.

One may argue that in love, a woman has to be more on her guard than a man, that in ‘letting go’, in going the way of the ‘empty glass’, she runs more risk than a man. That may be true, but remember that the heroine of ‘Left Alone’, in an earlier incarnation, was not more bee than flower, but was able to simply ‘be’. Indeed, she let down her armour and did not throw everything into question: ‘And all my armour falling down in a pile at my feet, and my winter giving way to warm as I’m singing him to sleep’ (‘Pale September’).

LEFT ALONE

Fiona Apple, ‘The Idler Wheel’, 2012

You made, you made your overtures

When you were a sure and orotund mutt

And I was still a dewy petal

Rather than a moribund slut

My love wrecked you

You packed to twirl your skirt at the palace

It hurt more than it ought to hurt

I went to work to cultivate a callus

And now I’m hard, too hard to know

I don’t cry when I’m sad anymore, no no

Tears calcify in my tummy

Fears coincide with the tow

How can I ask anyone to love me

When all I do is beg to be left alone?

Oh, when I try to love

And I can love the same man in the same bed in the same city

But not in the same room, it’s a pity, but

Oh, it never bothered me before

Not ‘til this guy, what a guy, oh God what a good guy

And I can’t even enjoy him

‘Cause I’m hard, too hard to know

I don’t cry when I’m sad anymore, no no

Tears calcify in my tummy

Fears coincide with the tow

How can I ask anyone to love me

When all I do is beg to be left

When all I do is beg to be left alone, alone, alone

My ills are reticulate, my woes are granular

The ants weigh more than the elephants

Nothing, nothing is manageable

So couldn’t we skip the valedictories

I can see a door there

Shut it and forget my number

‘Cause I’m hard, too hard to know

I don’t cry when I’m sad any more, no no

Tears calcify in my tummy

Fears coincide with the tow

How can I ask anyone to love me

When all I do is beg to be left

When all I do is beg to be left alone

A LITTLE IS ENOUGH

Pete Townshend, ‘Empty Glass’, 1980

They say that love often passes in a second

And you never can catch it up

So I’m hanging on to you as though eternity beckoned

But it’s clear that the match is rough

Common sense would tell me not to try and continue

But I’m after a piece of that diamond in you

So keep an eye open, my spirit ain’t broken

Your love’s so incredible, your body so edible

You give me an overdose of love, but just a little is a enough

I’m like a connoisseur of champagne cognac

The perfume nearly beats the taste

I eat an oyster and I feel the contact

But more than one would be a waste

Some people want an endless line that’s true

But all I have to have’s a little time with you

A smile sets me reeling, a kiss feels like stealing

Your love is like heroin, this addict is mellowing

I can’t pretend that I’m tough, just a little is enough

Just like a sailor heading into the seas

There’s a gale blowing in my face

The high winds scare me but I need the breeze

And I can’t head for any other place

Life would seem so easy on the other tack

But even a hurricane won’t turn me back

You might be an island on the distant horizon

But the little I see looks like heaven to me

I don’t care if the ocean gets rough, just a little is enough

Common sense would tell me not to try and continue

But I’m after a piece of that diamond in you

So keep an eye open, my spirit ain’t broken

Your love’s so incredible, your body so edible

You give me an overdose of love, a little is enough

V. FIONA APPLE: CARRION | THE CURE: BARE

FIONA APPLE: A lot of my friends mistook the word ‘carrion’ for ‘carry on’. And it’s not ‘carry on’, it’s ‘carrion’, as in ‘dead flesh’, as in’ dead body of animal’. And the reason why it means that is because I have this vision that when two lovers are not in love anymore but they hang around each other anyway out of obligation, or just out of habit, I see the love that they had between them as a corpse, as a dead body between them, as dead flesh. And it’s kind of like you were sitting in your room with a dead guy and you just couldn’t bring yourself to admit that he was dead, and you were talking to him and serving him things. It’s like that when people are together and they shouldn’t be together. That’s the way that I see it and that’s what this is about. It’s about realizing that and saying, ‘Listen, the thing is dead, let’s get rid of it’. (Introduction to a 1996 performance of ‘Carrion’)

Fiona’s introduction to ‘Carrion’ spells out for witless listeners what attentive listeners already understand: The song conveys the woman’s conviction that the relationship is over and the right thing to do is to walk away, not hang around: something the man can’t bring himself to admit. So she has to get it through his head that no appeal to spirits (‘seance’), no probing in the dark (‘searchlight’), no attempt to rekindle romance (‘love song’), no intellectualizing (‘questions’), no striving to get closer (‘distance’) and no violence (‘fist’) can change her conviction that the relationship is over and that nothing he can do can persuade her otherwise. Upon the jazz-feel of the music the voice floats, a velvety kindness enrobing steely resolve. (Three years later, on ‘Get Gone’, the iron fist would dispense with the velvet glove.)

There’s an admirable honesty in ‘Carrion’, a kindness that minimizes the cruelty, encapsulated in the ‘Honey, I’ve gone away’ refrain. ‘Bare’ presents us with the exact same situation as the one in ‘Carrion’—a lover taking their leave of their now ex-beloved—but does so in a more ambivalent way. Indeed, while the leaver arrogates to himself the control of the discourse—’If you’ve got something left to say, you’d better say it now; anything but “stay”, just say it now’—it quickly becomes clear that he is not as self-assured as he at first appears. Against the muscularity of the drums the string quartet is lush with nostalgia; against the steel strings of the guitar, the voice is fragile and plaintive. When got-it-together control fails to convince the leaver, he adopts the stance of jaded lover: ‘Well at least we’ll still be friends: yeah, one last useless vow.’

And when that stance too fails to convince, he resorts to world-weary inevitability: ‘It all just slips away, it always slips away eventually’. Finally, when world-weariness too doesn’t work, he declares his own despair: ‘There are long, long nights when I lay awake and I think of what I’ve done; of how I’ve thrown my sweetest dreams away, and what I’ve really become’. In ‘Bare’, then, honesty is the point of arrival of the leaver’s journey: in ‘Carrion’ it is the point of departure. So, if breaking up inevitably entails the leaver inflicting a measure of cruelty on the one being left, then sparing him or her the stances of control, jaded lover and world-weariness is a form of kindness. That the heroine of ‘Carrion’ takes full responsibility for her stance right from the get-go, that she forswears ambivalence and is decisive, is typical of Fiona Apple’s heroines. Indeed, with the exception of ‘Oh Well’ (where she plays the passive victim), she never indulges in posturing, as the hero of ‘Bare’ does. Such honesty is refreshing.

CARRION

Fiona Apple, ‘Tidal’, 1996

Won’t do no good to hold no seance

What’s gone is gone and you can’t bring it back around

Won’t do no good to hold no searchlight

You can’t illuminate what time has anchored down

Honey, I’ve gone away

Won’t do no good to sing no love song

No sound could simulate the presence of a man

Won’t do no good asking no questions

Your divination should acquaint you with the plan

Honey, I’ve gone away

My feel for you, boy, is decaying in front of me

Like the carrion of a murdered prey

And all I want is to save you, honey

Or the strength to walk away

Won’t do no good to go no distance

The space between us is as boundless as the dark

Won’t do no good to throw no fist, babe

You can’t intimidate me back into your arms

Because honey, I’ve gone away

BARE

The Cure, ‘Wild Mood Swings’, 1996

If you’ve got something left to say, you’d better say it now

Anything but ‘stay’, just say it now

We know we’ve reached the end, we just don’t know how

‘Well at least we’ll still be friends’: yeah, one last useless vow

‘There are different ways to live’: yeah, I know that stuff

‘Other ways to give’: yeah, all that stuff

But holding on to used to be is not enough

Memory’s not life and it’s not love

We should let it all go, it never stays the same

So why does it hurt me like this when you say that I’ve changed

When you say that I’ve aged, say I’m afraid

And all the tears you cry, they’re not tears for me

Regrets about your life, they’re not regrets for me

It never turns out how you want, why can’t you see

It all just slips away, it always slips away eventually

So if you’ve got nothing left to say, just say goodbye

Turn your face away and say goodbye

You know we’ve reached the end, you just don’t know why

And you know we can’t pretend after all this time

So just let it all go, nothing ever stays the same

So why does it hurt me like this to say that I’ve changed

To say that I’ve aged, to say I’m afraid

But there are long, long nights when I lay awake

And I think of what I’ve done

Of how I’ve thrown my sweetest dreams away

And what I’ve really become

And however hard I try I will always feel regret

However hard I try I will never forget

I will never forget

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2021 | All rights reserved

Comments

1 thought on “Fiona Apple: Ten Songs, Ten Echoes (Part 1 of 2)”

Ah, man! Such great writing. A rare read in that without knowing Fiona Apple’s work well, I am engrossed in the writing, dazzled by the ideas.