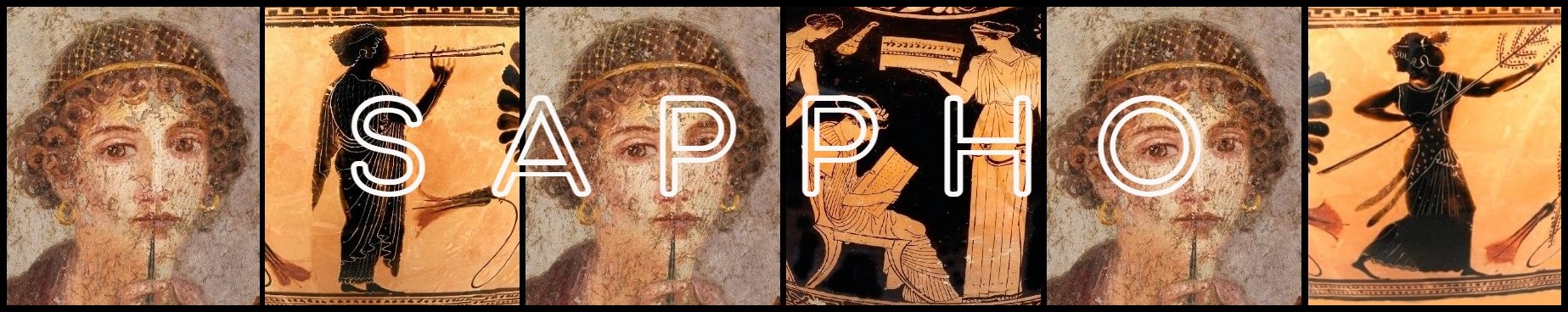

Sappho

SAPPHO: ARTICULATING SEXUALITY & DESIRE

Simon Goldhill

Posted by kind permission of Simon Goldhill, Fellow of King’s College, Professor of Greek Literature & Culture, University of Cambridge.

From Simon Goldhill, ‘Longing for Sappho’, in Love, Sex & Tragedy: Why Classics Matters (London: John Murray, 2004) pp. 78-86

Sappho shows more than any other figure how modern sexuality has used ancient Greece as a mirror in which to find itself. She is a model of how the West uses ancient Greece to think about desire. Since so little is actually known about the real Sappho, she is a wonderful canvas on to which to project an image of desire. Two Victorian paintings will help make this process of projection visible. They are two images from hundreds which could have been chosen. Sappho has constantly been used to express female longing in a man’s world.

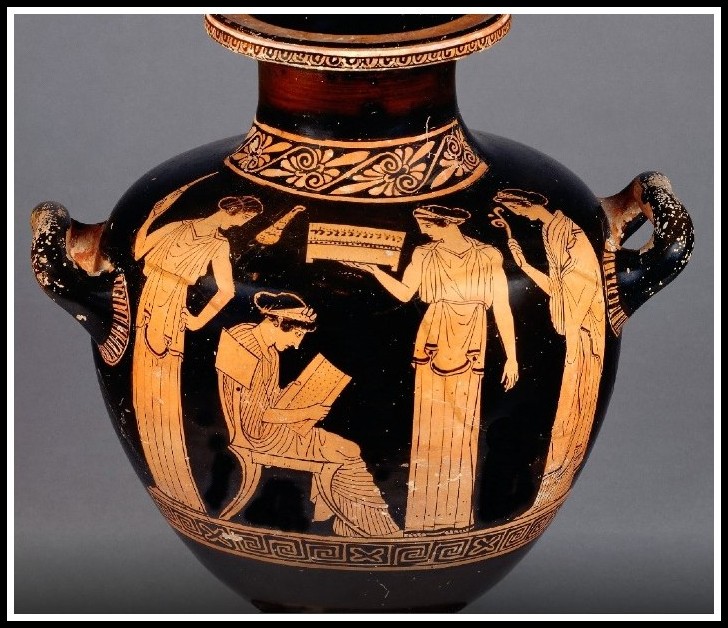

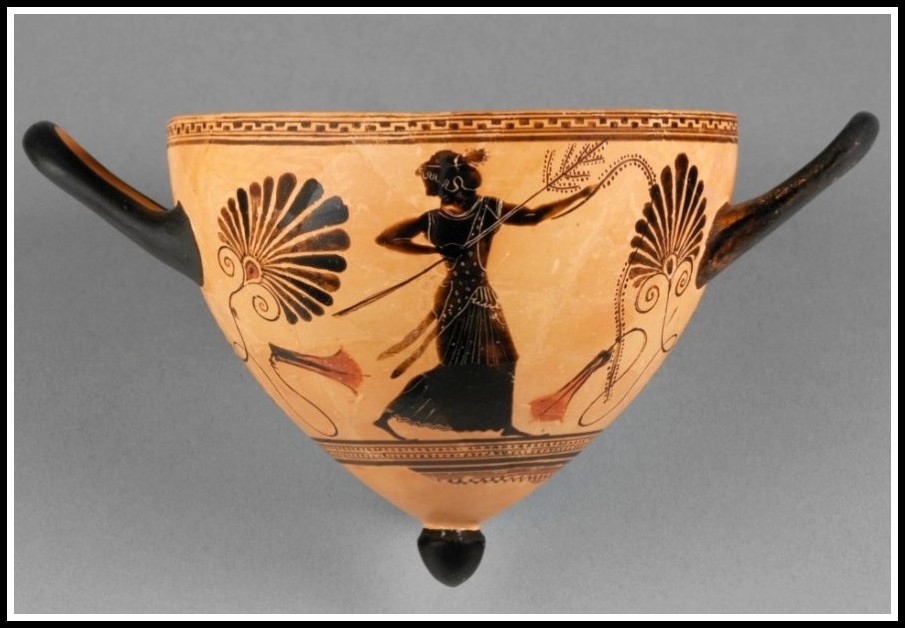

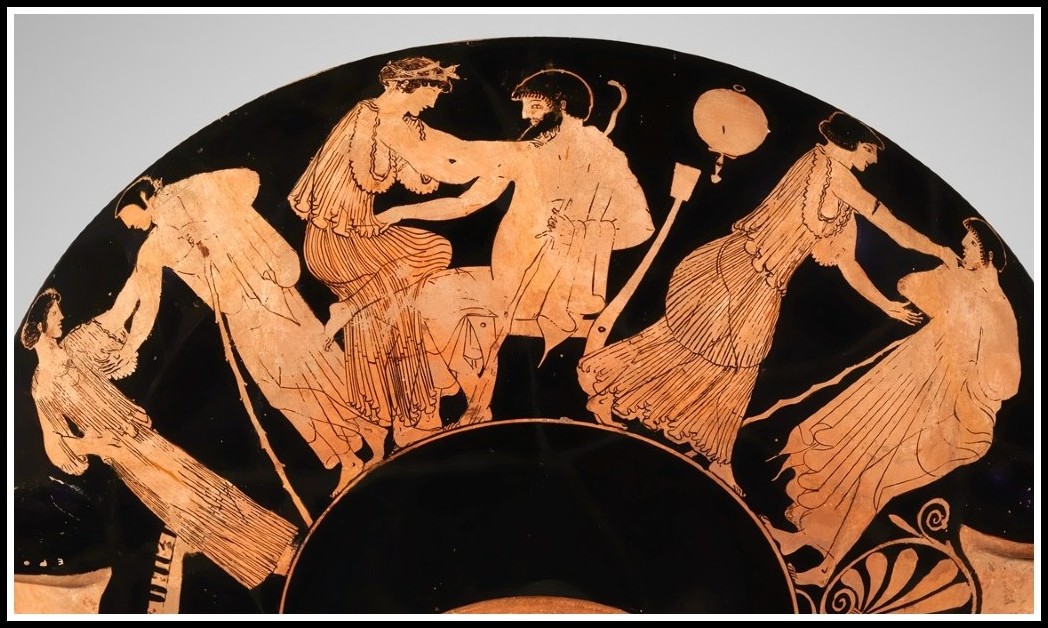

Amphora likely depicting Sappho, 450 BC | British Museum

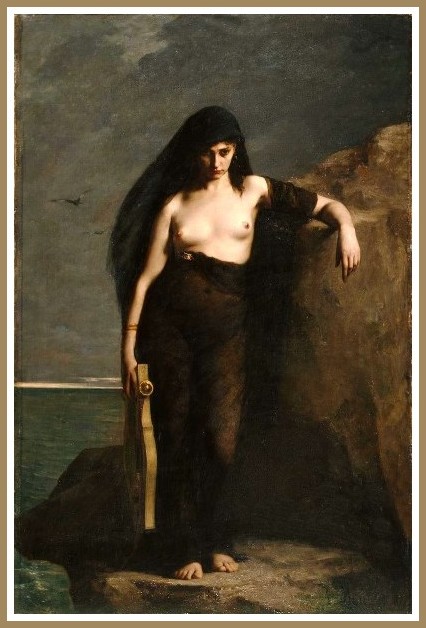

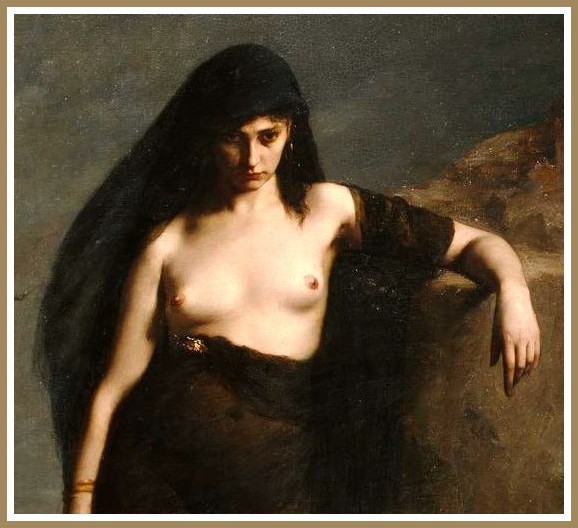

The first picture is a brooding, full-length portrait of Sappho painted by Charles-Auguste Mengin in 1877. Mengin is an undistinguished Parisian painter, but this is a memorable picture. Sappho, ‘dark’ as Ovid describes her, though not perhaps so short or so ugly, appears as a passionately moody young Romantic artist. Her left arm is languorously draped over a shadowy pillar, her right holds the lyre, her instrument and symbol of her authority. She stares with an inward gaze, her face shadowed by her hair and robe which run into each other, her eyes hooded by her brows. Her black tunic also flows into the shadows around her. She emerges into and from the darkness. This is not the Greece of light and purity, sunshine and rationality. This is the embodiment of a burning and dangerous passion. Since Byron, himself the archetypal hero of dangerous romantic passion, wrote ‘the isles of Greece, the isles of Greece, where burning Sappho loved and sung’, Sappho has indeed burnt and smouldered.

Charles-Auguste Mengin, Sappho, 1877

But in a powerfully erotic gesture Mengin has bared Sappho’s breasts and shoulders, and allowed these parts of her body to be as brightly illuminated as the rest of her is shaded. It’s not clear where the light could come from to irradiate her body in just this way and leave such deep shadows elsewhere in the picture. It seems as if the light from her breasts reveals what we can see of her face. This is a totally bizarre dress code, as if we are meant to think that this is how poets wandered about in archaic Lesbos. Mengin’s dream of the Greek world and of Sappho’s life lets the viewer gaze at the young girl’s exposed body. The painting could be intellectualized as a metaphor for the passion of artistic creativity: the burning love in her breast is a passion which flares out, and puts light in her face, the mirror of the soul. But the viewer is actually caught in a more obvious erotic stare at the girl’s fleshy breasts, and takes pleasure in the looking. This is a very sexy painting about a poet of love.

Charles-Auguste Mengin, Sappho, 1877 (detail)

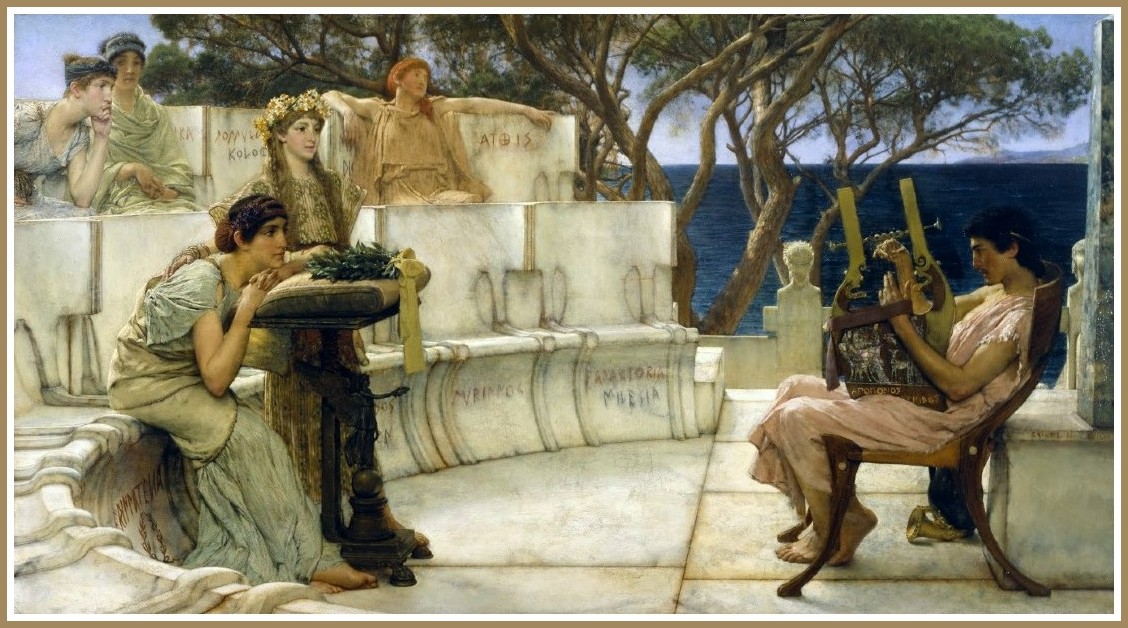

The second picture is a glorious canvas by one of the great popularizers of a vision of Greece for Victorian society, Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Alma-Tadema painted a string of lush and often louche images of the ancient world whose decorousness and archaeological accuracy scarcely conceal the titillating fascination with corruption, decadence and voyeuristic pleasure. The performing poet here, lyre in his arms, is Alcaeus, a man who is said in some stories to be Sappho’s lover. He is depicted as young and beautiful and, as he plays, he stares intently across the performance space at Sappho, who sits resting her head on her arm against a lectern. She returns his stare with a dreamy intensity. On the lectern, between the listening female poet and performing male poet is a laurel wreath, a victor’s crown awaiting a head. Behind Sappho, arranged on the marble benches, are three girls in various states of concentration, rapture and critical observation. A fourth stands behind Sappho. She is crowned with daisies, and, while she too looks at Alcaeus, her arm is draped across Sappho’s shoulders in an affectionate and protective manner. The stone benches are scratched with graffiti, which spell out in Greek the names of girls who were said to be the lovers of Sappho – Anaktoria, Atthis, Gongyla.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Sappho and Alcaeus, 1881

The sexual tensions of this painting are carefully calibrated. Sappho is transfixed in her shared gaze with Alcaeus. Is this erotic? Or is this a poetic rivalry? The laurel wreath is set between them, and the two poets are linked also by the wood of the lectern, Sappho’s reading stand, and the wood of Alcaeus’ chair and lyre, his performance space. This is poet face to face with poet. At the same time, the discarded golden drinking cup beneath Alcaeus’ chair suggests a certain decadent ease. Sappho, however, is placed among her girls. The graffiti listing her lovers’ names, set like plaques for each seat, spell out a history of poetical love affairs.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Sappho and Alcaeus, 1881 (detail)

The blazoned names and the protective hand of the beautiful standing girl suggest that, if there is an erotic tension here, it might be between the tradition which has Sappho dally with girls and the tradition which has her daily with boys. Is Sappho to cross the line between her band of girls and Alcaeus? The picture asks the viewer to read desire in this painting. Who wants whom and on what terms?

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Sappho and Alcaeus, 1881 (detail)

This is a quite remarkable painting, particularly for the Victorian period, precisely because of its rare ability to suggest–thanks to its classical veils–a tension between a woman’s sexual love for women and her love for a man. In the heart of Victorian high culture, something is articulated on canvas that cannot be named. Through Sappho and her Greek landscape, silenced desire finds a voice.

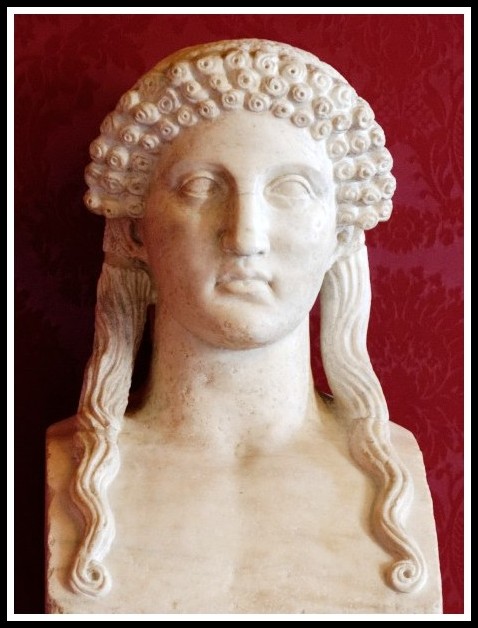

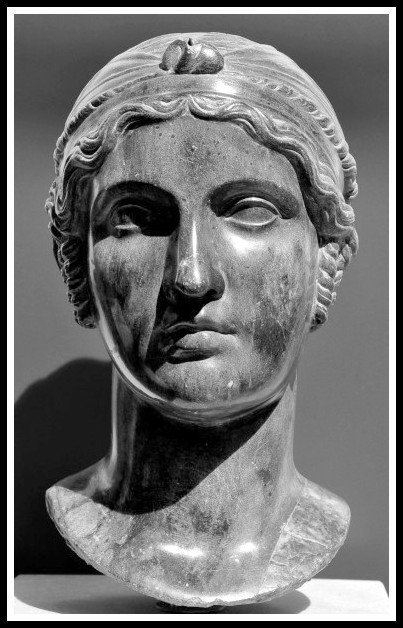

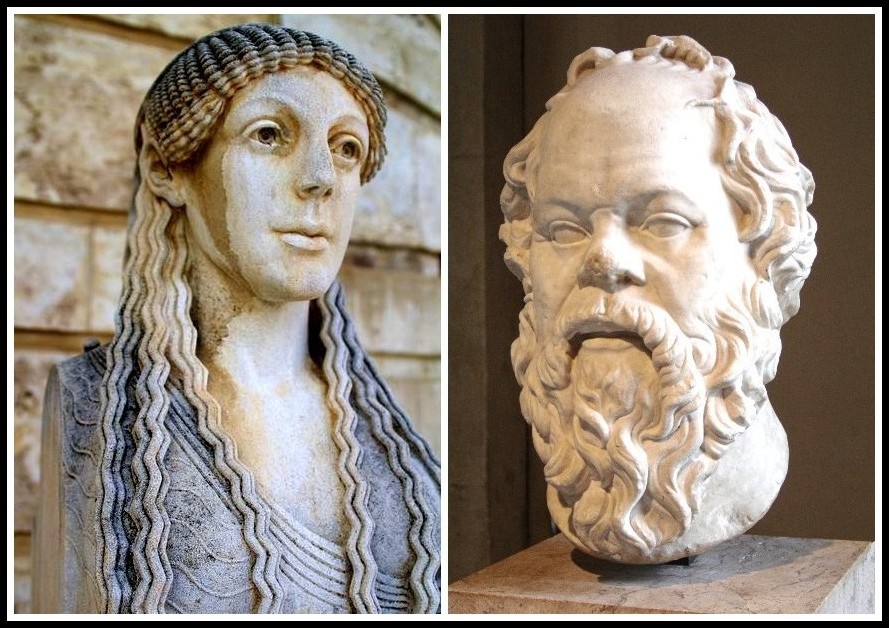

SAPPHO FROM ERESOS

Roman copy of Greek original, 5th century BC

Sappho shows brilliantly how Greece inhabits the modem sexual imagination. She is a figure through whom to talk about desire, to paint desire, to fantasize desire. The perfect male body of Greece provides a canonical image which shapes our vision of masculinity. Sappho has no one physical form–but the idea of Sappho provides the shifting mirrors on which a kaleidoscopic range of expressions of desire is produced. Sappho lets the modern world articulate and feel desire.

SAPPHO | POMPEII

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, c. 565 AD

SAPPHO: THREE BOOKS

ANNE CARSON

Eros the Bittersweet

SIMON GOLDHILL

Love, Sex & Tragedy

ANNE CARSON

If Not, Winter: Sappho

SAPPHO IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 14

̶ Are you afraid to look back, Sprague? Do you think you’re going to lose your Eurydice like Orpheus did?

There’s a steely edge to the blue of her eyes, echoed by the blue of the jacket and pants she’s wearing. White T-shirt and tennis shoes: Cool.

̶̶ To tell the truth, I’ve never understood that mysterious moment when Orpheus looks back. All that effort to reach Eurydice in the Underworld, and then—just before reaching the light—he looks back and loses her. I confess, I just don’t get it.

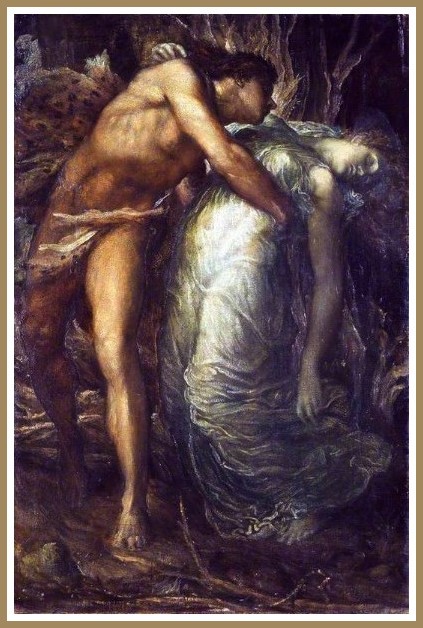

George Frederic Watts, Orpheus & Eurydice, 1878

̶ It’s about faith, Simona says.

̶ Faith?

̶ Yeah. Rumour has it that love can’t survive without it.

The scalloped hem of her voile skirt falls to just above her knees: I won’t fall that far. She continues:

̶ He didn’t have the faith to believe she’d still be there. He didn’t love her enough.

She loves me, she loves me not: White daisies pattern the navy skirt, white as the white of her sweater.

George Frederic Watts, Orpheus & Eurydice, 1870

Riva comes in:

̶̶ Then again, it could be the opposite. Maybe he loved her too much. Maybe it was excess of love that made him look back.

Beneath her plush burgundy blazer, the black of her silk-chiffon top is transparent. As transparent as she is?

̶̶ Either way, she continues, we all know what happened to him!

̶ Remind me, I say. I’ve forgotten.

I like her red lips and long hair. I like the light in her eyes.

̶̶ A lost soul, Sprague. That’s what he became. Ended up getting ripped apart by the Maenads.

̶ Who were jealous of his love, Héloïse specifies.

̶ Legend has it only his head survived, Nicole adds. Fell into a river, drifted down to the sea. And do you know where it washed up?

̶ Where?

̶ In Lesbos. That’s how Sappho got her gift of song.

ATTIC BLACK-FIGURE MASTOS, C. 515 BC | J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM

‘This side depicts a woman flourishing a branch and an ivy sprig which, together with the nebris (animal skin) that she wears over one shoulder, identify her as a maenad, a female follower of Dionysos.’

I think of a Sappho fragment. I want to recite it, but the words won’t come. Instead, I ask:

̶̶ Am I in the way, Riva?

̶ What are you talking about? We’re happy to meet Marietta’s lover.

She raises her glass:

̶̶ Here’s to the two of you!

̶ And to your beautiful eyes! Héloïse says.

̶ Yes, Nicole adds, they go very well with Marietta’s.

Vodka and gin, rum and Bourbon—is that the taste of ambiguity?

Sappho bust | Museo Nazionale Romano

Stand to face me beloved

And open out the grace of your eyes:

It comes to me now, this fragment of Sappho;

It comes to me from the depths of my soul.

Sappho, I hear your voice in the hills of Mitylene,

I hear your lyre in the mixolydian mode:

With unabashed frankness you reveal yourself,

With undeceived insight you lay love bare.

I would like to pay you homage, however humbly;

I would like to pass on what you have given me:

The conviction that love needs no premeditation,

That in the being of another one’s self expands.

And so I tune my lyre to your intonations,

From my lyric I expunge ornament and explanation:

It is enough that I open myself to grace.

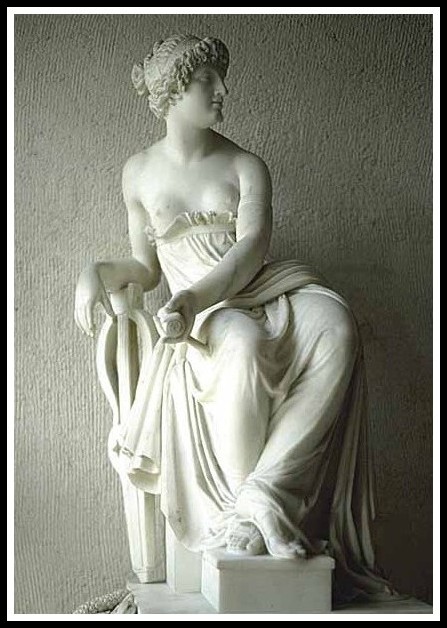

Claude Ramey, Sappho, 1800

̶ So, what are you up to these days? you ask Riva.

̶ Translation. I’ve just finished an anthology of erotic fiction. By women, of course.

̶ Of course. French to Italian, or the other way around?

̶ The other way around. Italian to French.

̶ And how long have you been working as a translator?

̶ You don’t remember?

̶ No.

̶ I’d already started when I was going out with Inès.

̶ Is that so?

̶ Yes. Now I can afford to translate only what I like.

̶ You must be very good.

̶ I’ve worked hard…

So this is Riva, the woman who, before she met Inès, had never had an erotically satisfying relationship. Neither with a man nor a woman. Struggled against her homosexuality. On experiencing its power, she was shocked and desperate, appalled at her own response. Felt condemned, as if she’d just signed her own death sentence. This Inès told you in the Lounge of Neon Lies.

Gustave Courbet, The Sleepers, 1866

Simona approaches you.

̶ I’m working on a new project.

̶ Great. What is it?

̶ I’ve been commissioned to design a perfume bottle.

̶ Congratulations!

̶ It’s for Leonora. They’re launching a new scent, Demoiselle de la nuit.

̶ What’s it like?

̶ Wonderfully perverse! A mixture of masculine and feminine, woody patchouli and white floral, with blackcurrant, lime, and a touch of liquorice. And—here’s the real kicker—something overripe and perfectly louche!

̶ I like it! And the bottle, will it be louche too?

̶ Louche, no. Erotic, yes!

Your eyes sparkle.

̶ Tell me more!

̶ I first toyed with the idea of a bottle that goes against the scent. You know, something for prim girls in glasses.

̶ Who go wild at night?

̶ Exactly!

̶ Like Riva! Héloïse jumps in.

Riva whirls her head wildly, then pulls a prim, perfectly straight face. Everybody laughs.

Gerda Marie Fredrikke Wegener, The Connoisseurs, 1917

̶ As it turned out, Marketing didn’t like the idea. Then I took the opposite tack—baroque and humorous, in the spirit of Ladies Almanack.

Djuna Barnes—the slow narcotic of Nightwood, the anatomy of love: through a black diamond, lucidly.

̶ You know, tipping the velvet, tongue in cheek.

The joyful wit of her Vanity Fair portrait, white wine with Joyce at the Deux Magots.

̶ In a word, louche, but ironic.

Sticking her tongue in Nicole’s ear, Héloïse flicks it languorously. Everybody laughs.

̶ No, Marketing didn’t like that either. So finally I decided to combine the sober and the obscene, without irony. A naked woman kneeling, head thrown back.

That’s exactly the photos we made at Sint-Idesbald! I say:

̶ The essence of power, the scent of submission!

̶ Yeah!

Héloïse pulls her belt out of her pants and wields it over her head like a whip.

̶ On your knees, Sprague! Lick my boots!

Everybody laughs.

̶ Yeah, that’s what I’m going for. But not so straight! The key to my figurine-bottle will be ambiguity.

Gerda Marie Fredrikke Wegener, The Circle of Love, 1917

̶ Maybe Demoiselle will become the Kouros for girls, Riva says. Then they could smell us. I’m sick of being taken for straight.

Héloïse jumps in:

̶ Oh Riva, not that again! Every lesbian who’s not butch simply has to accept that femme and hetero are indistinguishable.

̶ I don’t like false advertising, Héloïse. It makes for frustration all round.

̶ Do you want to live in a ghetto?

̶ No. But I do want to be recognized for what I am.

̶ Oh come on, you’re not exactly living in the well of loneliness!

̶ Of course not. But the fact remains, for the butch we don’t belong, and for the straight we’re one of them. Why do we have to walk down the street holding hands to be recognized for what we are?

̶ Is it really such a big deal?

̶ You can handle being come on to by guys. I can’t.

I jump in:

̶ Why don’t you wear a T-shirt, Riva, saying, ‘This is what a lesbian looks like’?

̶ What do you know about it, Sprague?

̶ Well, I know a pigeon in a box can easily be recognized, but it can’t fly like one who is free.

William Rothenstein, Two Women, 1895

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

The Power of Eros: Sandra Boehringer on Sappho

GENDER AND EROTIC FLUIDITY IN A ‘PRE-SEXUAL’ SOCIETY

Posted by kind permission of Sandra Boehringer, Professor of Greek History, University of Strasbourg

From Sandra Boehringer, ‘La force d’éros: Genre et fluidité érotique dans une société d’« avant la sexualité »’. Revue française de psychanalyse, 2019/5 Vol. 83 (pp. 1555-1562). Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

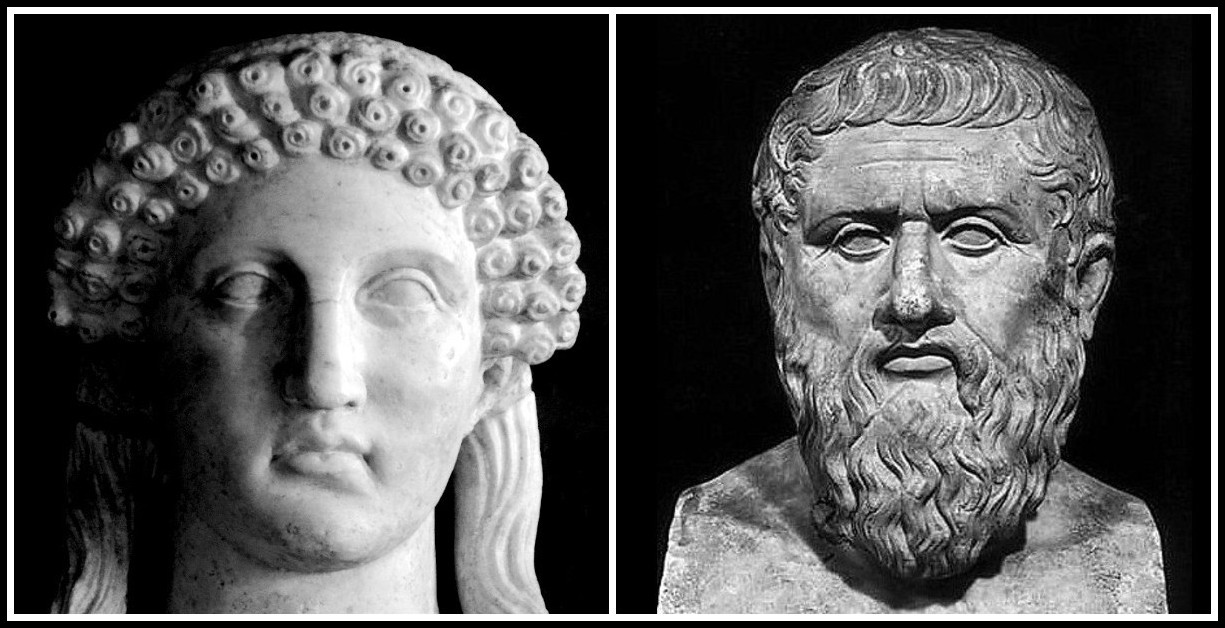

Sappho | Plato

Freud’s invention of the concept of ‘psychic bisexuality’ is a milestone in the development of his theory of sexuality. In the humanities, the historicity of the psyche (that of psychoanalysis is not that of the ancient Greeks) and the historicity of sexuality and its structure (contemporary sexuality is not classical eroticism) have been extensively studied during the twentieth century, from a psychoanalytic perspective as well as from a historical and philosophical one. Yet what are we to make of the prefix ‘bi’ in ‘bisexual’— to what exactly does it refer? Can the dual polarity of a sexuality derived from the belief in two ‘biological’ sexes be conceived in a manner consistent with the historicity and fluidity of a broader conception of ‘psychic bisexuality’?

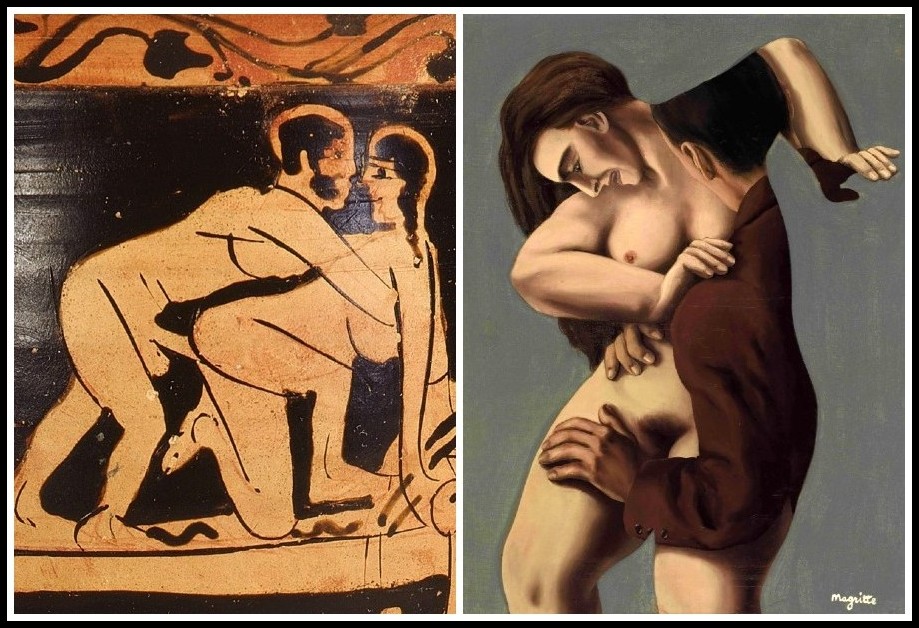

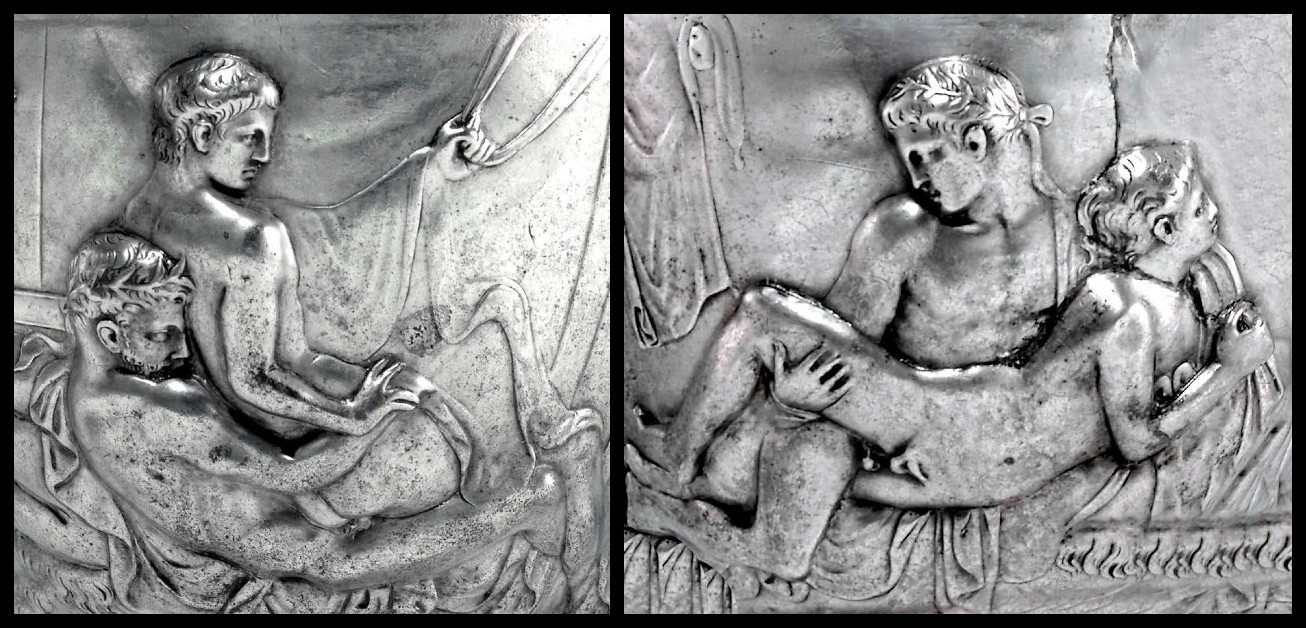

Man & Woman Making Love, Attica, 550 BC (detail) | René Magritte, Les jours gigantesques, 1928

To address this question, approaching the concept of ‘bisexuality’ from the perspective of historical anthropology and cross-cultural analysis will prove fruitful. Within the framework of the anthropology of ancient Greece, then, this paper endeavours to show that a consideration of Plato’s eros in the light of the lyric poetry of archaic Greece yields surprising insights.

Prosper d’Epinay, Sappho, 1895 | B.H. Fowler, Archaic Greek Poetry | Plato, The Symposium

I. ANCIENT EROTICISM IN ‘PRE-SEXUAL’ SOCIETIES

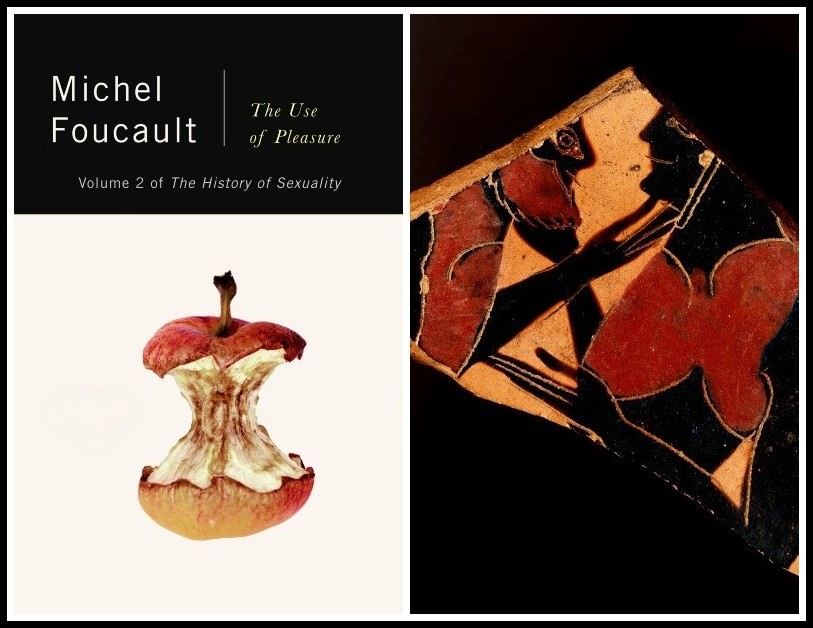

Sexuality is neither invariable nor a natural ‘given’. As Michel Foucault writes in The Use of Pleasure, ‘There is a rich and complex field of historicity in the manner in which an individual is called upon to recognize himself as a moral subject of sexual conduct’. Indeed, in Greece as in Rome, sexual activity is not perceived independently of other practices of the body. From a social perspective, what is evaluated morally is not a sexual practice as such (there is no ban, for example, on sodomy) but rather the individual, in terms of sex, age and social status, and his sexual practices. As for the supposed truth of the subject, it does not reside, for the ancients, in his sexual desires.

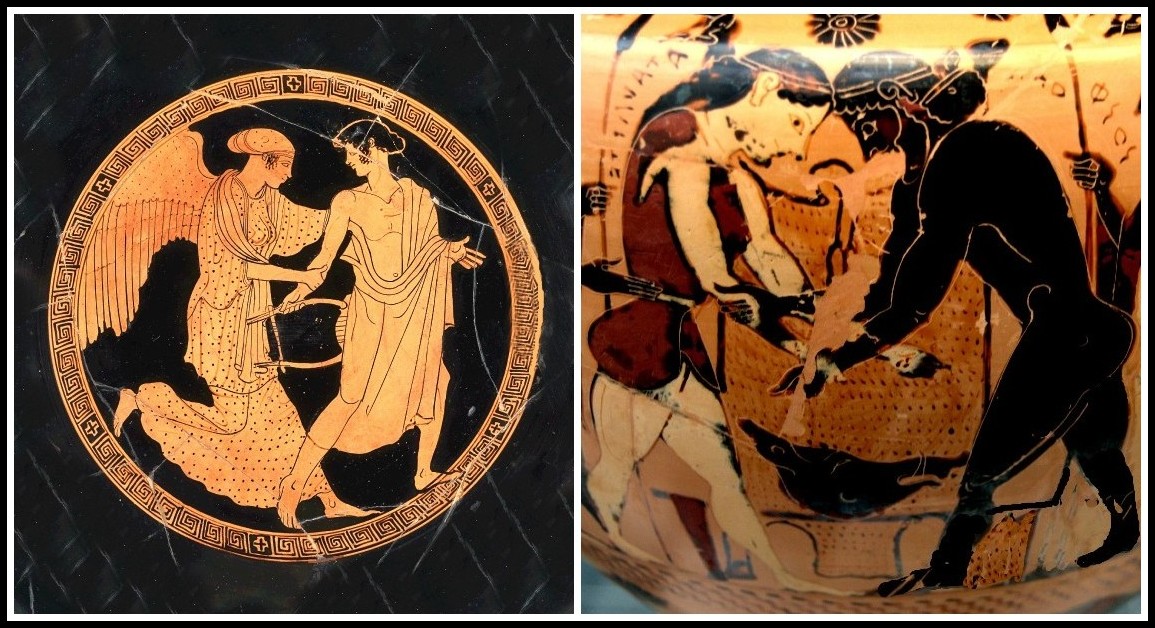

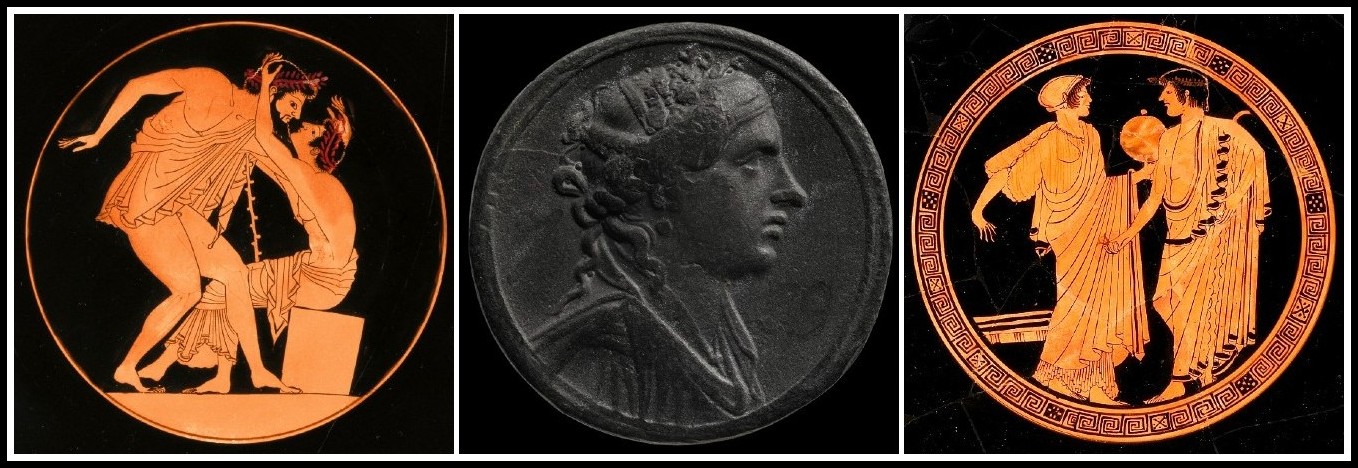

Michel Foucault, The Use of Pleasure | Bearded Man Courting Boy, Attica, 560 BC

It follows all the more strongly, then, that if there is no ‘structure of sexuality’ bearing a truth, it is not possible to identify in the ancient world the equivalent of today’s sexual categories. Indeed, the ancients never conceived a homogeneous category that would indistinctly encompass men and women of all social milieux having nothing in common but same-sex attraction—no more than they posited an opposing category that would embrace men and women of opposite-sex attraction. In short, the categories ‘heterosexual’ and ‘homosexual’ did not exist.

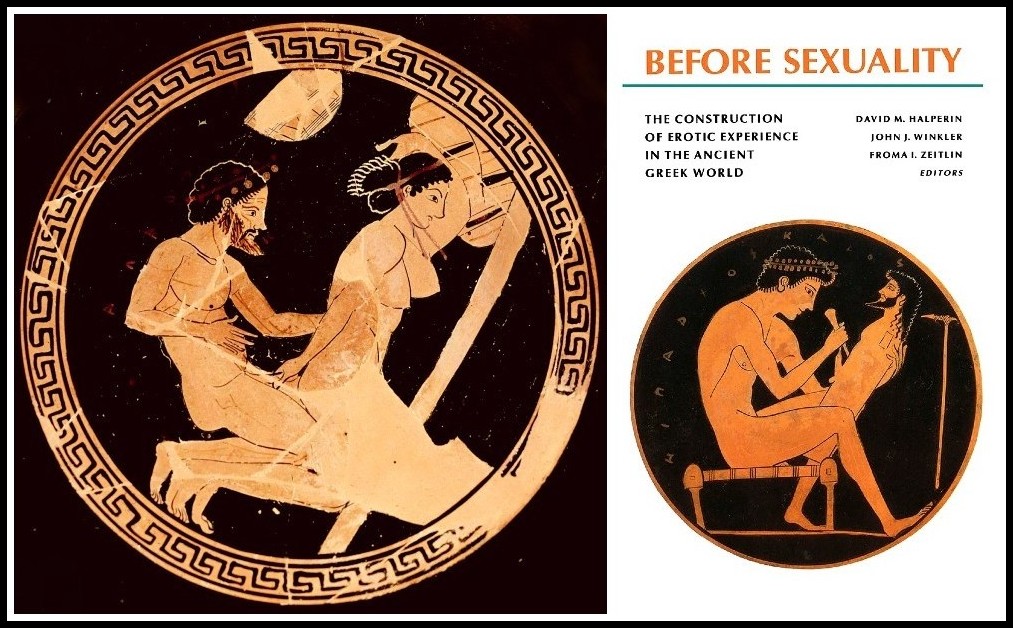

Man & Woman Making Love, Attica, 505 BC (detail) | David Halperin, ed., Before Sexuality

These configurations, and the moral evaluations they give rise to, change over the centuries. One observes, for example, the esteem bestowed on love between men and boys in Greece, in contrast to Rome where sexual relations with a future citizen were forbidden, but where male homoeroticism remained prominent in cultural representations, in the idealization of Greece, and in the relations between citizen/freed slave and citizen/slave. All these variations enable us to see apparently natural classifications as historically conditioned.

Two Scenes of Male Homosexual Love-Making, Rome, 15BC-AD15 (detail) | British Museum

II. SAPPHO’S EROS

Sappho lived on the island of Lesbos in the 6th century BC. She did not write ‘love poetry’, as we, caught up in a time where love is a private and intimate matter, often say anachronistically.

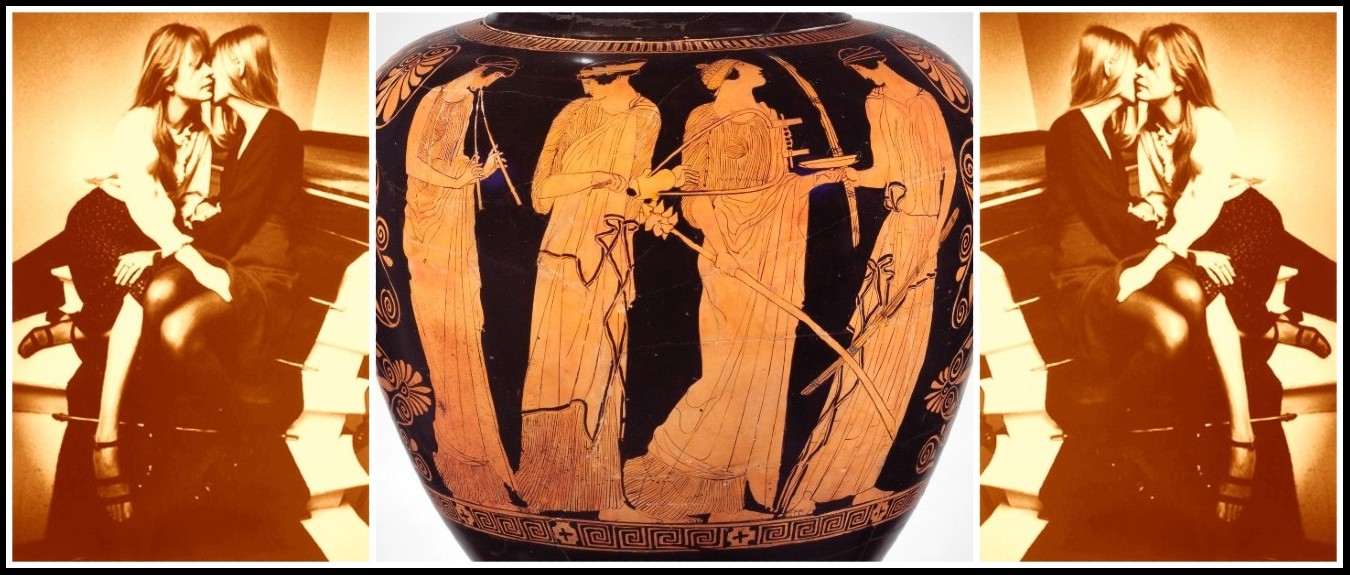

Jeanloup Sieff, Couple de femmes dans l’escalier, 1971 | Maenads Making Music, Attica, 450 BC

In a society where the separation of body and soul does not exist, Sappho evokes thumos, a zone of the body that experiences the effect of eros. Eros is an external force that can be devastating: ‘Eros shook my mind like a mountain wind falling on oak trees’ (Sappho fr. 47, tr. Anne Carson).

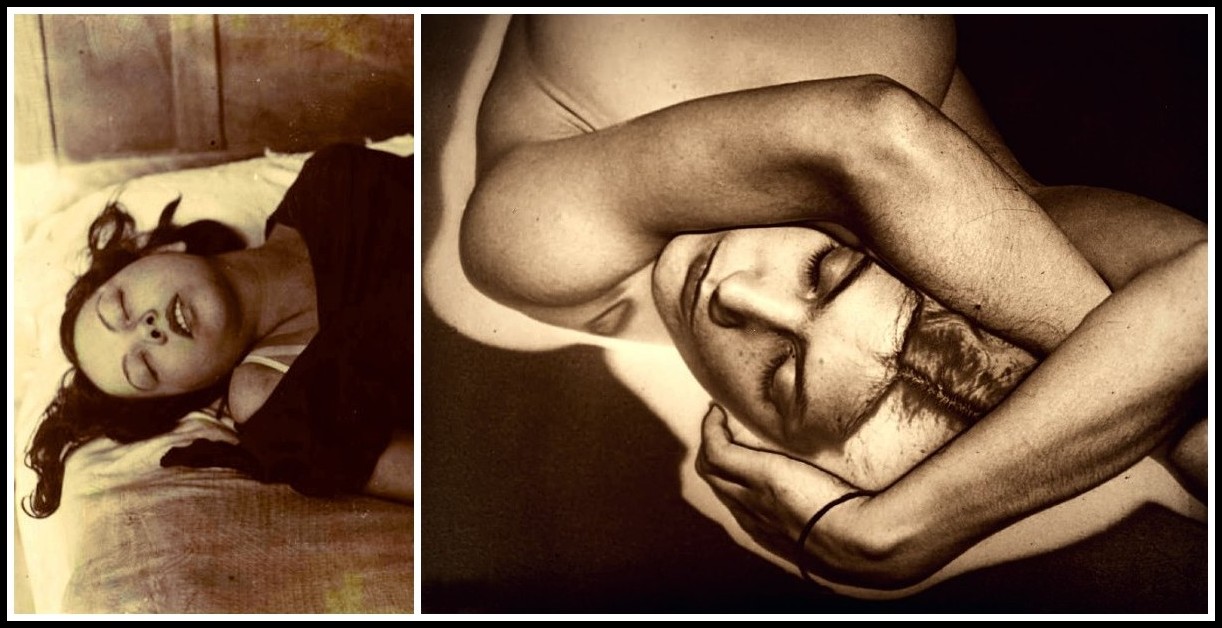

Bassaï, Phénomène de l’extase, 1933 | Man Ray, Natasha, 1931

In her poems for solo or choral public performance, Sappho invents in words and music a mapping of the body that would become epoch-making. Her most well-known poem portrays the symptoms of a person struck by eros:

He seems to me equal to gods that man

whoever he is who opposite you

sits and listens close

to your sweet speaking

and lovely laughing—oh it

puts the heart in my chest on wings

for when I look back at you, even a moment, no speaking

is left in me

no: tongue breaks and thin

fire is racing under skin

and in eyes no sight and drumming

fills ears

and cold sweat holds me and shaking

grips me all, greener than grass

I am and dead—or almost

I seem to me

But all is to be dead, because even a person of poverty

Sappho, Fr. 31, tr. Anne Carson

SAPPHO FR. 31: TRIANGULATION OF DESIRE

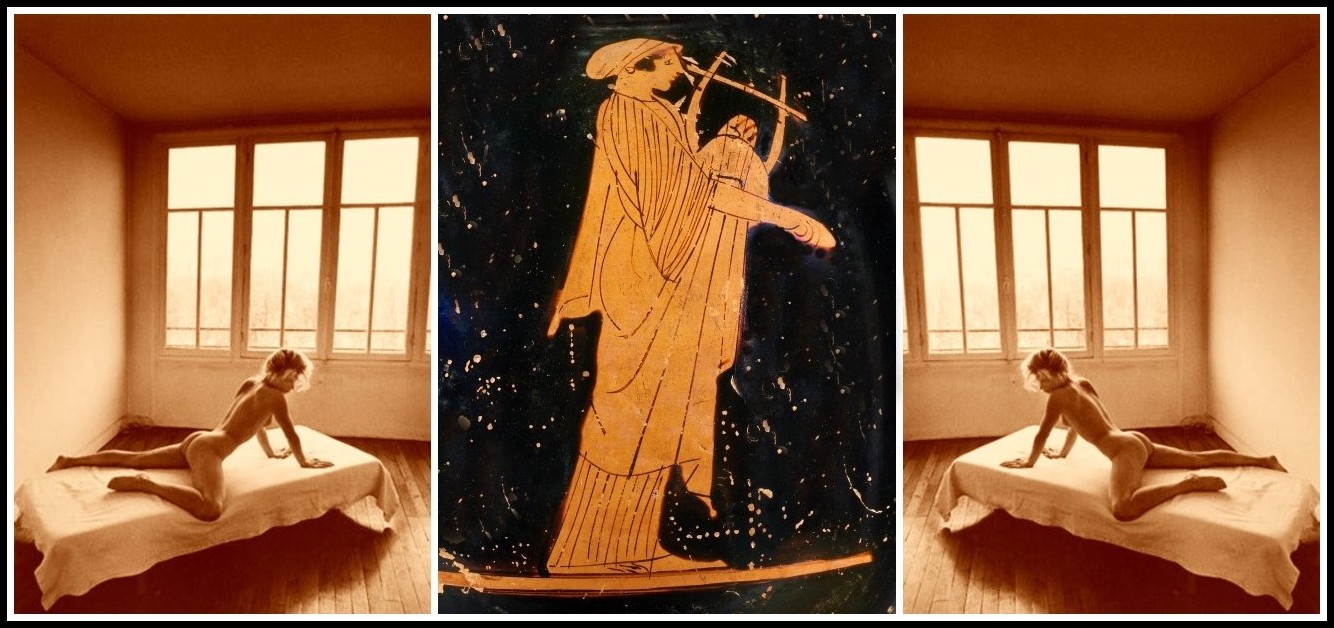

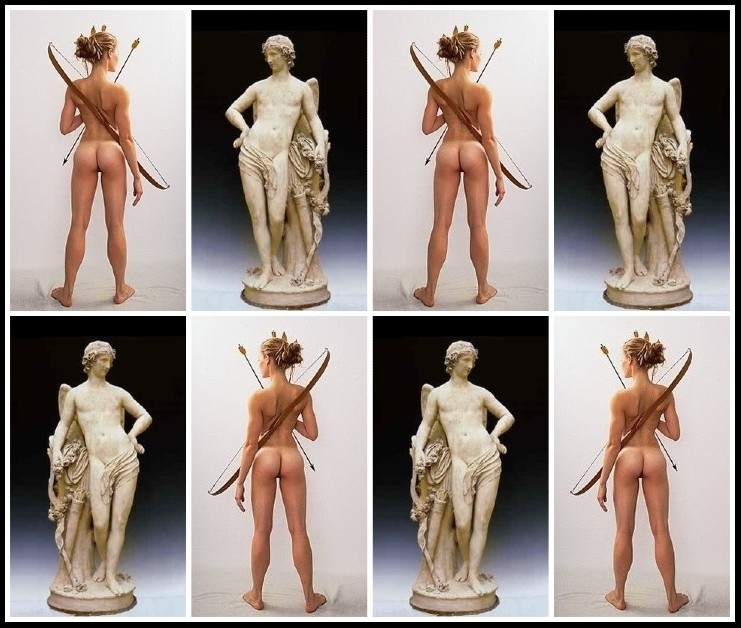

Singer Playing Kithara, 490 BC, MET | Photos: G. Ridderstrom, K. Vilaysing

In the erotic configurations sung by Sappho, eros makes of the lover a victim, in the sway of its power, while the beloved takes advantage of the lover’s subjugation to exert power over him/her. This dynamic is captured in ‘The New Kypris Song’, a poem by Sappho discovered in 2014:

How is it possible, now, not to feel endlessly dizzy,

O Kypris, mistress, whoever the person whom one loves here;

how is it possible not to want to be unburdened of the suffering

fallen upon one?

What is your intention in stirring me up and tearing me apart madly

with desire that unsettles so? I implore you, mistress,

You’re making me suffer terribly; once you were not […

and you didn’t turn me away […

…] you, I want […

…] to suffer that […

…] for my part, I am

aware of that.

Sappho, tr. Dirk Obbink; modified by Sandra Boehringer

Young Man & Woman, Attica, 520-510 BC | Photo: Luis Galvez

The lover is in the grip of nausea and vertigo; the body becomes the site where emotions are expressed, where paradoxical symptoms arise to make of the song a moment of metamorphosis. What’s more, these effects of eros are sung in public by a choir. Far from a privacy and an intimacy that are all too contemporary, what we have here is a performance, a spectacle that speaks to the whole audience.

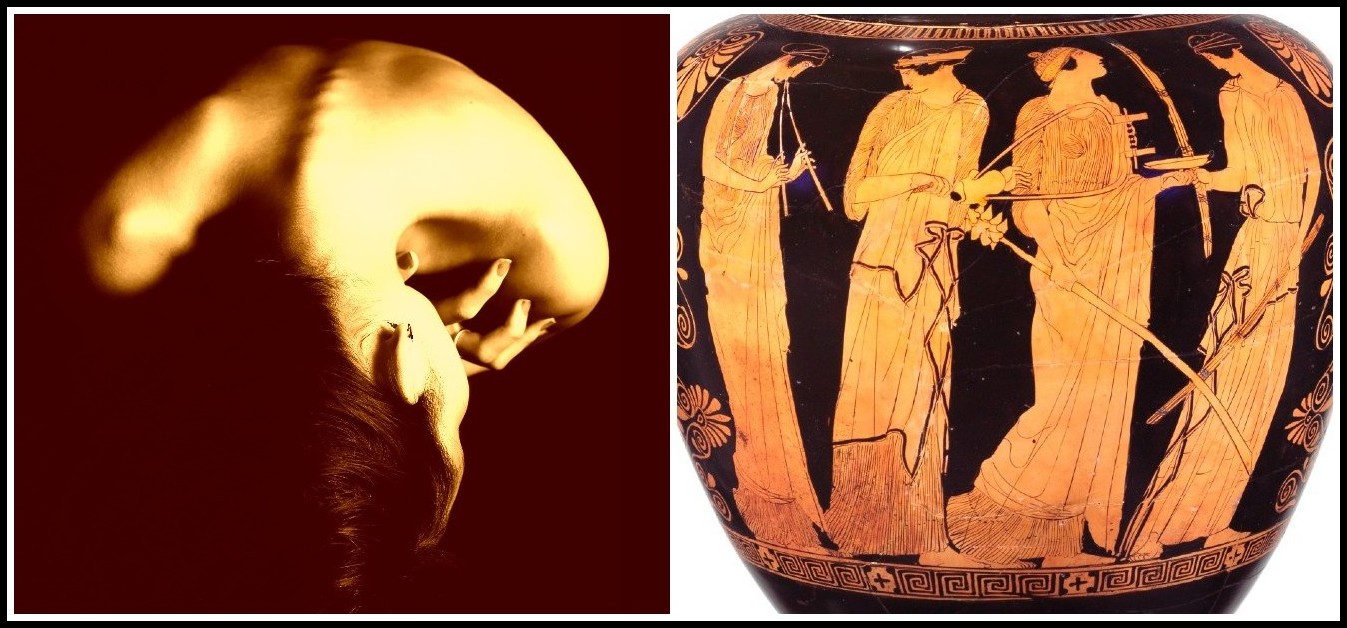

Photo: Jairo Alzate | Maenads Making Music, Attica, 450 BC

In almost all Sappho’s poems both lover and beloved are women, yet the vocabulary of the body is plural. Sappho often uses forms characteristic of both sexes, and the effects produced by eros are not dependent on the sex of the lovers.

Jeanloup Sieff, Marie-Odile, 1986 | Woman Playing a Lyre, Attica, 465 BC

When one examines the gender of the protagonists in the erotic poetry of Sappho’s century, one discovers a real fluidity. In a poem by Theognis of Megara, for example, one finds a comparison between a handsome young man and the fierce heroine Atalanta, while in Sappho’s fragment 58 (augmented 2004 version) a beloved woman is compared to Tithonus, a Prince of Troy taken as a lover by the goddess Eos. As for the poet Anacreon, he portrays himself as a bashful lover of a ‘boy with a girlish gaze’ (fr. 360).

Eos Pursuing Tithonus, Attica, 460-450 BC | Atalanta Wrestling Peleus, Chalkida, c. 550 BC

A force which sets in motion, a spirit which moves body and soul, a cartographer that ‘zones’ the body (as Jean-Luc Nancy writes in Corpus), outside of all sexuation: this pre-classical eros is characterized by gender fluidity, preceding the very idea of any binary structure.

EVFROSINA: Fly, 2017 | Up, 2017

III. PLATO’S EROS

Two centuries later, around 380 BC, Plato, at a banquet at the house of Agathon, stages a friendly contest of extemporaneous speeches in praise of eros. The structure of the Symposium, as the text is known, is a succession of speeches whose order enables one to understand the philosopher’s overall argument. Before the drunken Alcibiades, alive with desire for Socrates, bursts in and gives his celebrated agalmata speech, Plato has Socrates speak. Socrates relates the philosophy of love taught him by Diotima of Mantinea, which asserts that wisdom implies a progression from love of beautiful bodies to love of beautiful souls and finally, to love of philosophy and the contemplation of pure ideas.

Victor Wager, Diotima of Mantinea, 1937 | Socrates, marble copy of bronze, 1st c. AD

Aristophanes’ speech plays a key role in the proceedings, marking an inflection point in the structure of the work, as it prepares for Diotima’s affirmation of the dissociation between the motive force and the object of the motive force. Aristophanes, in real life a famous author of Athenian comedy, resorts not to any Greek myth alive in popular belief, but to a zany story of three spherical creatures—male, female, androgyne—cut in two by Zeus and forever thereafter search for their missing half.

Plato, The Symposium, Aristophanes

It is to this story that Freud refers when he evokes ‘the eros of the divine Plato’ in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. He writes: ‘The popular view of the sexual instinct is beautifully reflected in the poetic fable which tells how the original human beings were cut up into two halves—man and woman—and how these are always striving to unite again in love.’ Staying with the theme, Freud echoes Aristophanes again when he writes, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, that ‘a drive might be seen as a powerful tendency inherent in every living organism to restore a prior state’, and goes on to refer to ‘the theory that Plato has Aristophanes expound in the Symposium, which deals with the origins not only of the sexual drive, but also of its most important variation in relation to the object’. At this point, Freud explicitly evokes the figure of the androgyne.

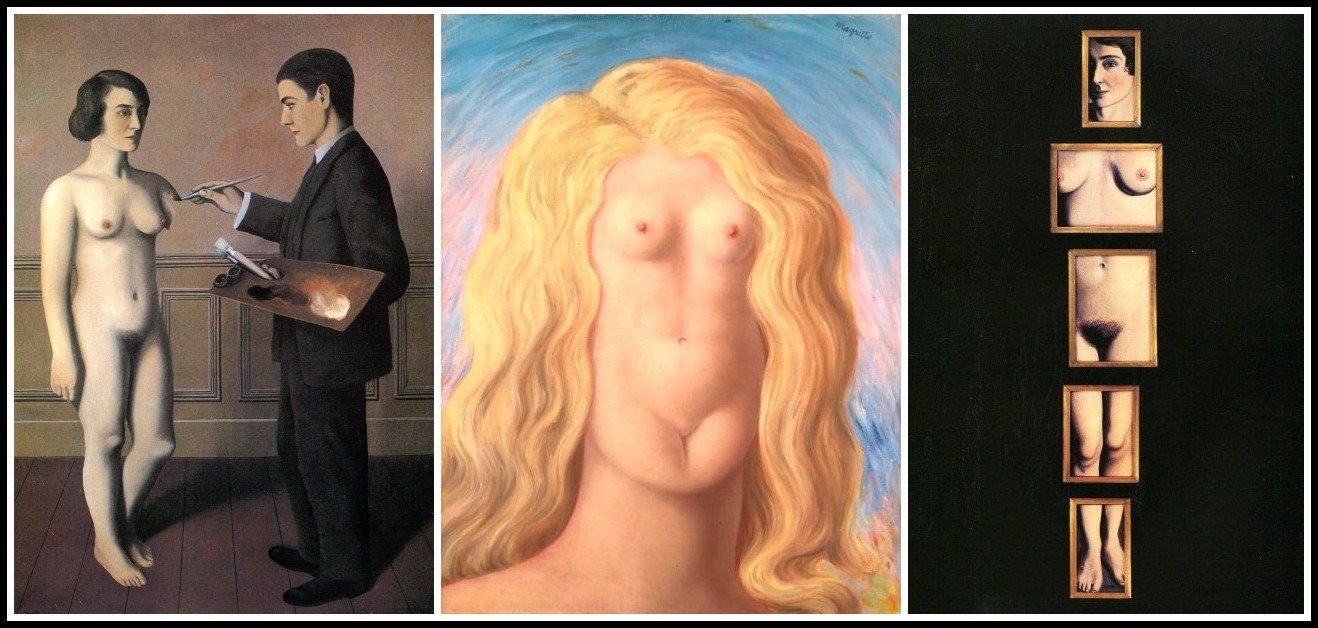

RENÉ MAGRITTE: Attempting the Impossible, 1928 | The Rape, 1945 | Eternal Evidence, 1930

In the burlesque story told by Aristophanes, however, the sexual configuration is rather more complex. Indeed, the eros that drives the search for the other half concerns not only heterosexual attraction but the entire set of separated parts, male and female, of the three spheres (male, female, androgyne). The heterogeneous sphere is only one of three possible configurations.

Lovers, 480 BC | MET

Analysis of Aristophanes’ speech in its entirety brings its essential elements into relief. The common feature that distinguishes the manner in which the half-creatures are driven by eros is not the sex of the beloved but rather the intensity of the drive to find the other half. Each sentence describing the search for the other half characterizes the strength of the drive as either normal or intense. So, for those split from the mixed sphere, there are husbands or seducers of women, wives or seducers of men; for those split from the female sphere, there are hetairistriai (and not ‘lesbians’, which would be the term today for those animated by a normal-strength drive), and finally, for men who intensely seek a male half, Plato has Aristophanes say there is no term for them except ‘shameless’ (which is inappropriate), implying that it is always ‘normal’ to intensely search for a male partner when one has been split from a male sphere. Moreover, Plato-Aristophanes adds, it is these men who are ‘bold, brave and masculine, and… the only ones who end up as politicians’.

Kiss, 505 BC, Getty | Sappho, 16th c., British Museum | Man Offering Woman a Flower, 480 BC, Getty

So much for the etiological dimension of this zany fable. Now what of its theoretical aspect? We see that it is eros who set the half-creatures in motion, whatever their sex may be. In his preamble to the succession of speeches, Plato recounts Diotima’s philosophy of love that posits love of philosophy as its highest form, and goes on to dissociate the drive not only from its object but also from the sex of the beloved. He has Aristophanes sum up his speech by saying, ‘eros is the name for the desire and pursuit of wholeness’. The eros of Aristophanes is not simply the attraction of a man for a woman (characteristic of those split from an androgynous sphere) nor is it the Platonic eros described by Diotima. To what tradition, then, does this eros belong? To what exactly is Freud referring when he cites this poetic fable?

Guy le Baube, Cupidon, 2013 | Gilles Lambert Godecharle, Cupidon, 1804

IV. FROM SAPPHIC EROS TO THE FREUDIAN DRIVE: A LITTLE-KNOWN GENEALOGY

Even when we take into account the distortions induced by Plato’s staging of Aristophanes’ comic mode, eros, in the first part of the fable, unsettles, brings awareness of incompleteness, causes longing, activates desire, impels movement, and leads to despair and even devastation. It must be emphasized that these effects are operative for every person, no matter which of the three spheres they were split off from; moreover, the sex of the lover or the beloved has no effect on the nature of eros.

GUY LE BAUBE: Dogs, 2002 | Eyelashes, 2005

These characteristics are, without a doubt, those of the eros of the archaic poets, elements of a cultural and specifically musical past familiar to the ancient Greeks. Plato takes them up here in order to buttress Aristophanes’ fable with tradition. Indeed, for all his criticism of the poets, Plato owes a great deal to them. This debt is made clear by Socrates in Phaedrus, particularly as regards erotic matters: he explicitly cites Sappho and Anacreon, poets well-known to his audience.

Adolf Steinhäuser, Cupid, n.d. | Guy le Baube, Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, 1987

What Freud is referring to when he cites Plato’s Symposium, then, is the passage where the influence of archaic poetry on the banqueters’ description of how eros operates is most pronounced. In citing the passage from Aristophanes’ ‘poetic fable’, Freud, while putting the accent on the androgynous sphere, nevertheless highlights the key aspects of the concept: a drive without an object, and the effects the force produces. In a footnote he added in 1910 to the Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, he writes: ‘The most striking distinction between the erotic life of antiquity and our own no doubt lies in the fact that the ancients laid the stress upon the instinct itself, whereas we emphasize its object. The ancients glorified the instinct and were prepared on its account to honour even an inferior object; while we despise the instinctual activity in itself, and find excuses for it only in the merits of the object.’

JEANLOUP SIEFF: Corset, 1962 | Carel, 1985

An alternative genealogy can now be posited. While Freud cites Plato, he in fact draws on the eros of the archaic poets in constructing his theory of the drive (‘instinct’ in early translations). To the discourse of Diotima-Socrates-Plato, Freud prefers that of Aristophanes. And thus we recognize, contrary to common belief, that Freud’s theory of sexuality owes less to the classifications of a philosophical fable imagined by a thinker of the 4th century BC than it does to the fluid eros of the poets of earlier centuries. From Sappho to Freud, the link is now restored.

JEANLOUP SIEFF: Nu sur un lit, 1976 | Téléphone, Paris; 1981

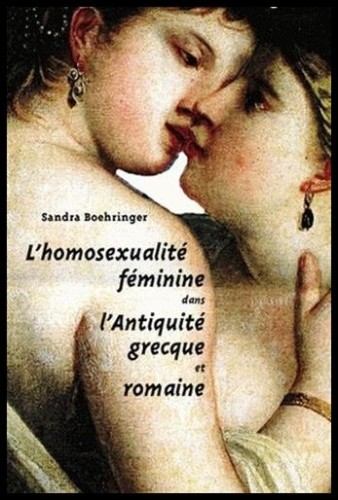

SANDRA BOEHRINGER BOOKS: MEN, WOMEN & SEXUALITY IN ANCIENT GREECE

SANDRA BOEHRINGER

Homosexualité féminine – Antiquité

SANDRA BOEHRINGER

Hommes et Femmes – Antiquité

SANDRA BOEHRINGER

Female Homosexuality – Ancient Greece

SAPPHO OF MYTILENE

SAPPHO IN SONG

Prosper d’Epinay, Sappho, 1895 | Angélique Ianatos

Sappho Sung by Angélique Ionatos & Nena Venetsanou

The following text, freely adapted and translated by Richard Jonathan, is based on a concert review by Veronique Mortaigne that appeared in the French newspaper Le Monde in 1991.

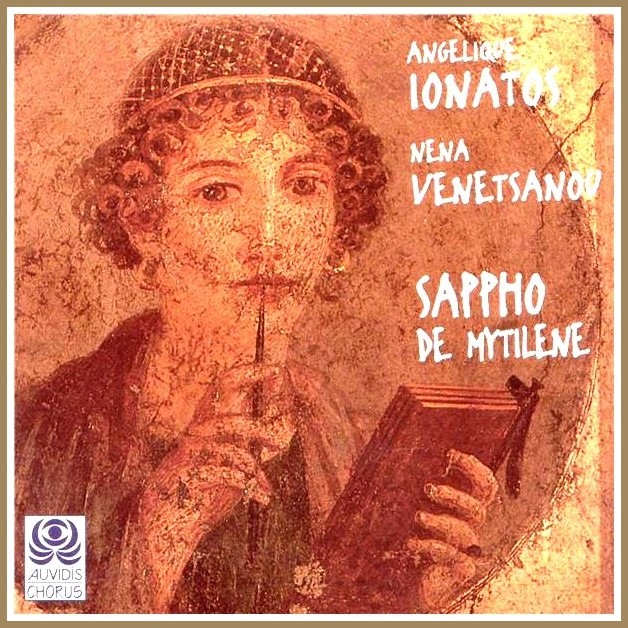

Angélique Ianatos, Sappho de Mytilène, 1991

SAPPHO DE MYTILÈNE: ANGÉLIQUE IONATOS & NENA VENETSANOU

Two, they sing as one the lyrics of Sappho of Mytilene, the feisty poet of 2,600 years ago who Plato called the ‘tenth muse’. Two: Angélique Ionatos, contralto, easy to imagine as a rebellious girl in Greece running barefoot on a stony path; Nena Venetsanou, a mezzo-soprano with the stature of a diva. Both outstanding singers, they intertwine their voices in the silence and sound of Sappho’s poetry.

Angélique Ianatos

Ionatos starts singing a melancholy song, ‘I write my lyrics with air’. Venetsanou, an Athenian familiar with the verses, for having sung them, of Éluard, Garcia Lorca and Kazantzakis, remains silent. She lets the words flow, bathing in the music that Ionatos has composed (with Christian Boissel), then comes in: ‘I saw picking flowers a joyful child of tender years, whiter than milk, more supple than meandering water’, accompanied by Ionatos on guitar and four multi-instrumentalists (clarinet, oboe, keyboards, percussion, lute, marimba) who create a starkly noble music that is authentically Greek. They weave together threads from the imagination of a young woman, distant in time but contemporary in sensibility, of whom the Nobel prize-winning poet, Odysseus Elytis, her translator into modern Greek, has said: ‘I see her as a distant cousin who played in the same gardens, around the same pomegranate trees, above the same wells, as I did.’

Angélique Ianatos | Photo: Marion Lefebvre, 2014

The eighteen poems chosen for Sappho of Mytilene are sung in modern Greek (translated by Elytis) as well as in ancient Greek, out of respect for ‘their natural musicality’. A difficult task, for of Sappho’s poems time has delivered but scattered fragments interlaced with enigmatic blanks. Rising to the challenge, Angélique Ionatos took advantage of the blanks either to fill the silences, buttress the word upon which a phrase turns, amplify the voices, give space to the instruments or, instead, to commune with the features of the Sapphic universe, the fire of desire, the disquieting gaze. In this, Angélique Ionatos proves once again how at home she is in the world of poetry.

Angélique Ianatos