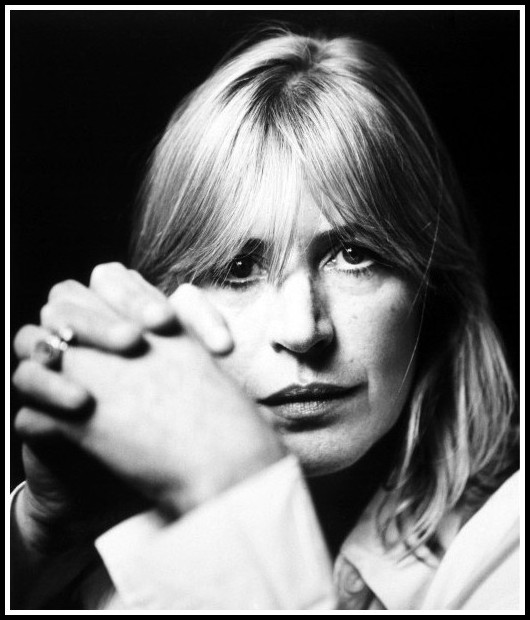

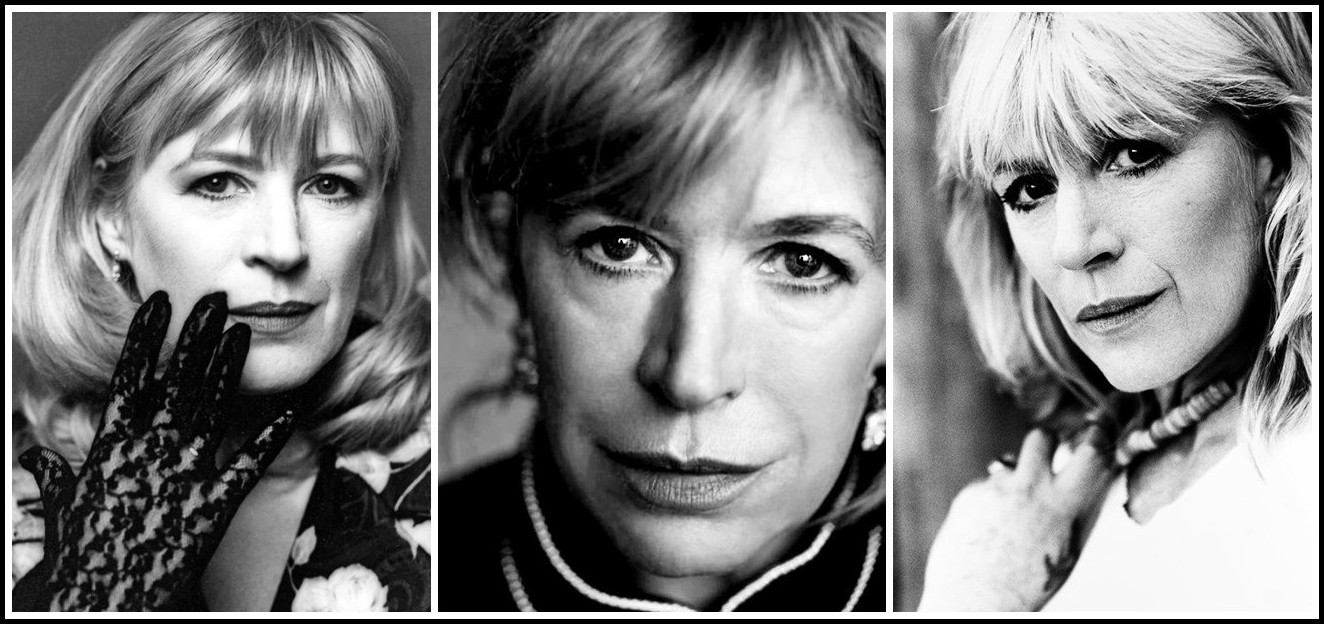

ART & AUDIENCE III: MARIANNE FAITHFULL

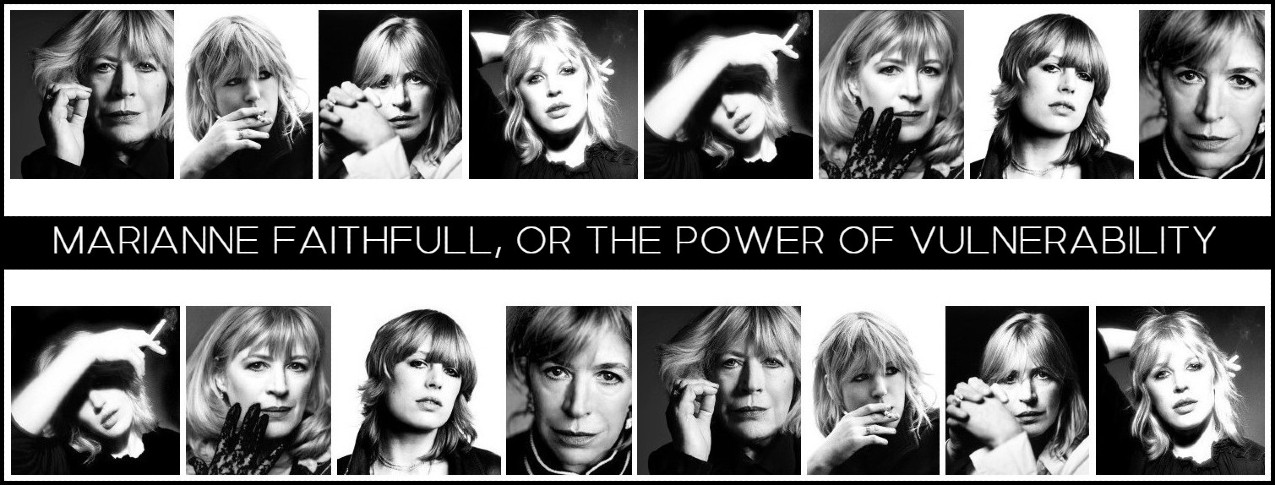

MARIANNE FAITHFULL, OR THE POWER OF VULNERABILITY

Marianne’s audiences tend to be small, not at all commensurate with the greatness of her art. Why?

Richard Jonathan

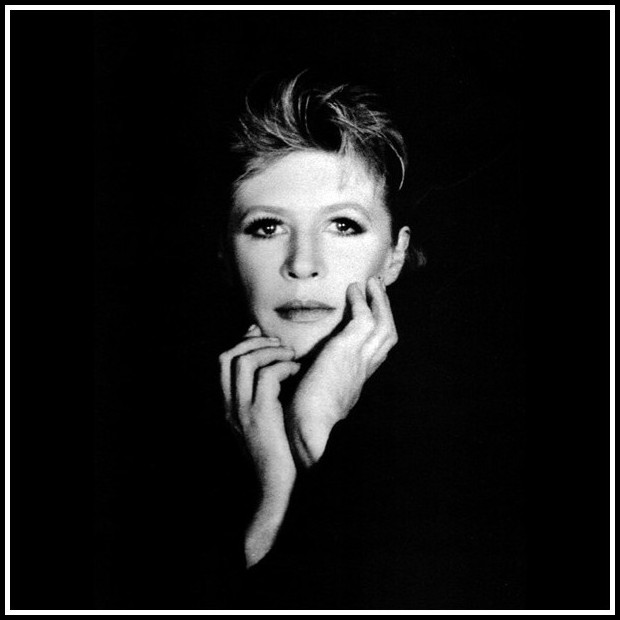

Marianne Faithfull | Dennis Morris, 1979

I – MARIANNE FAITHFULL: THE MUSIC MACHINE, CAMDEN HIGH STREET, 1978

An autumn evening in 1978. The Music Machine, Camden High Street, London. Despite the name, there’s nothing techno about the place: a three-tier theatre in faded red and gold, it dates from Victorian times. I like this marriage of the chic and the seedy, the louche air of it all: I imagine a powdered tart with scarlet lips drinking sherry in a brothel lounge, a shiny trinket dangling between her hard-working tits.

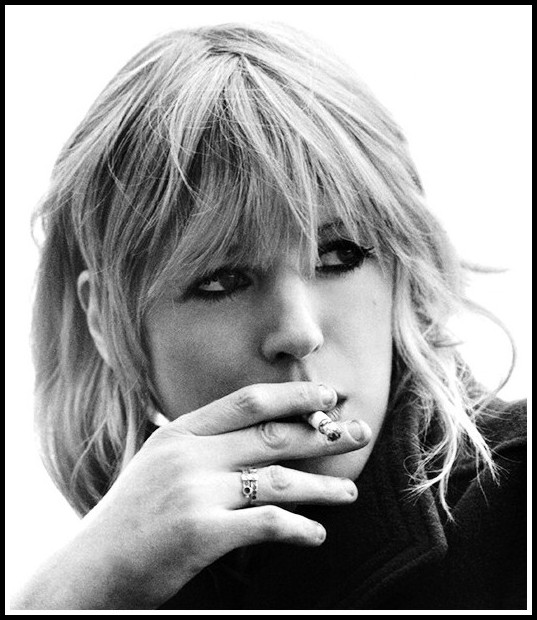

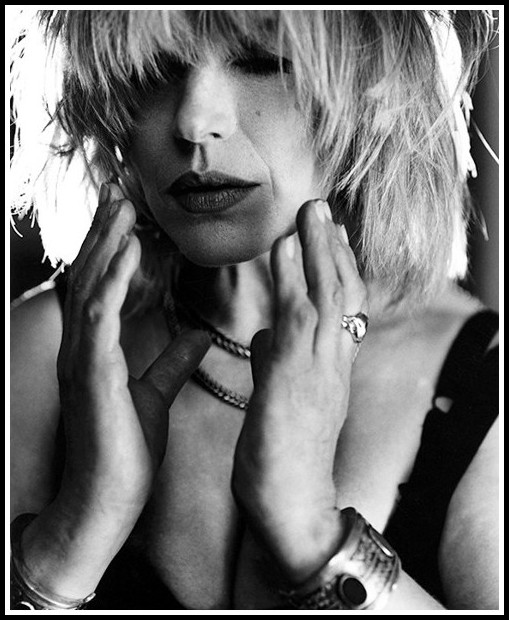

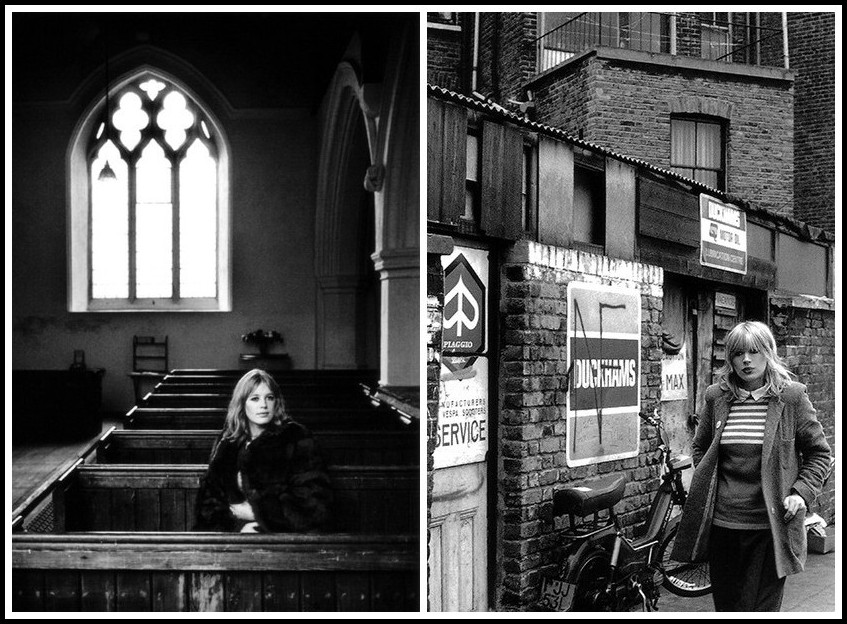

Marianne Faithfull | Terence Spencer, 1979

The house lights go down, the band steps on stage. Two guitars, bass and drums, the centre mike unmanned. As the stage lights go up, the band launches into the ‘Sweet Jane’ intro, silvering the electricity of Steve Hunter’s majestic lines. Listen! The burning tears of Orpheus emerging from the underworld, a phoenix rising defiant from smouldering ruins. Look! Waiting in the wings, Marianne Faithfull stands, smoke curling from her fingers, the pallor of her body bright against her black mini-dress. There’s an expectant calm in her expression; I sense the fire and ice in her veins. The intro segues into Lou Reed’s signature riff, the cue for Marianne to step on stage: she doesn’t take it. No matter, keep it going: the riff’s meant to be repetitive. Still Marianne stands, a contented spectator. Turning to face her, the Strat guitarist coaxes her to come out. A touch of sass in her stride, she walks to the microphone. ‘Standing on a corner, suitcase in my hand’: Gravelly, the voice comes; instantly I am transported. To where? To where I belong.

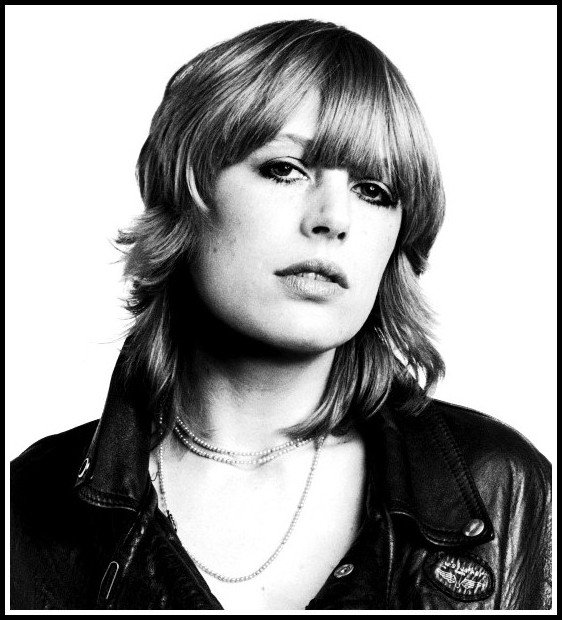

Marianne Faithfull | Martin-Richardson, 1978

Midway through the concert Marianne sang a new song: ‘Brain Drain’. To end the evening, another new one: ‘Why D’Ya Do It?’. And thus, to the two hundred or so of us in the audience, she let it be known that Marianne Faithfull is back, and back on her own terms: From now on, she will be no-one but herself. The beauty of that self, still struggling with heroin, touched me deeply. And when, a few months later, Broken English was released, I felt in every fibre of my being the freedom that comes when pretences fall.

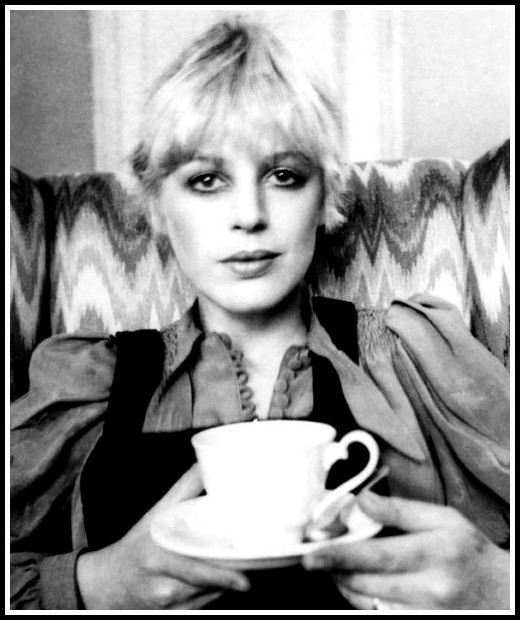

Marianne Faithfull | Dennis Morris, 1979

II – MARIANNE FAITHFULL: COURAGE AND ENDURANCE

Marianne Faithfull sings dark songs. Never-ending longing, not happy endings; courage and endurance, not flash-in-the-pan bravado. Though she may venture out into spring and summer, autumn and winter are her seasons. Falling leaves and driving snow, not honeyed sunlight and hyacinths. Hers is the world of night, not daylight; beauty, not prettiness. It is a world where I am at home.

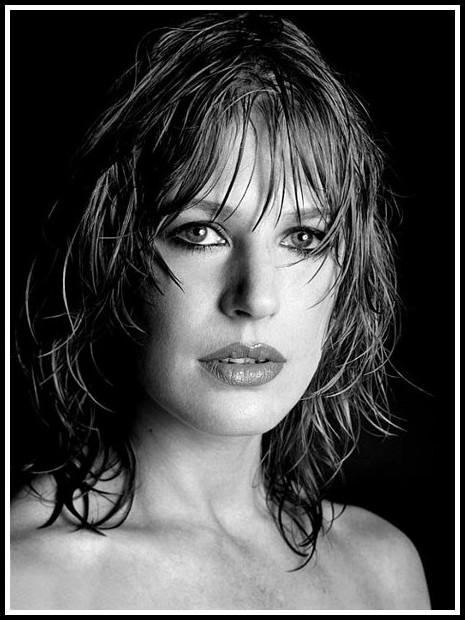

Marianne Faithfull | Robert Mapplethorpe, 1974

I am, I realize, one of a relative few. Not many people are at home in such a world: Marianne’s audiences tend to be small, not at all commensurate with the greatness of her art. This is not surprising. The nerve she touches in the heart is a nerve connected to vulnerability: a state that puts us at risk. Indeed, heightening our humanity, vulnerability calls forth kindness; making us cut the crap, it forces us to get real. For many people, this is a terrifying prospect. Whatever the cost, the self-satisfactions of narcissism, the safety of ‘self-sufficiency’, are what they prefer. Fools, I say. And they return the compliment. How can you be attracted to someone so dark and depressing? they ask. Normally I just smile and walk away, but now I’ll try to provide an answer. And for that, I’ll turn to Greek tragedy.

Marianne Faithfull | Jean-Pierre Masclet, 1996

The pain of emotions, pity and fear, the pleasure of catharsis: that’s part of it, no doubt. As Anne Carson puts it her preface to Grief Lessons—Four Plays by Euripides:

There is a theory that watching unbearable stories about other people lost in grief and rage is good for you—may cleanse you of your darkness. Do you want to go down to the pits of yourself all alone? Not much. What if an actor could do it for you? Isn’t that why they are called actors? They act for you. You sacrifice them to action. And this sacrifice is a mode of deepest intimacy of you with your own life. Within it you watch yourself act out the present or possible organization of your nature. You can be aware of your own awareness of this nature as you never are at the moment of experience. The actor, by reiterating you, sacrifices a moment of his own life in order to give you a story of yours.

Substitute ‘Marianne Faithfull’ for ‘an actor’ and you’ll have a fair idea of my position.

Marianne Faithfull | Bruce Weber, 1994

There are many ways of dividing up the world. Those who can dance and those who can’t. Those who have a chip on their shoulder and those who don’t. Those who sleep on their stomach in free-fall and those who sleep in the fetal position. The one that resonates most with me is the divide between those who see themselves reflected in the social world and those who look outside themselves and find no reflection. Marianne’s music, like the paintings of Francis Bacon, the photographs of Francesca Woodman or the poetry of Sylvia Plath, boldly asserts its individual vision; in doing so, it offers a reflection to those who find none in the world of convention.

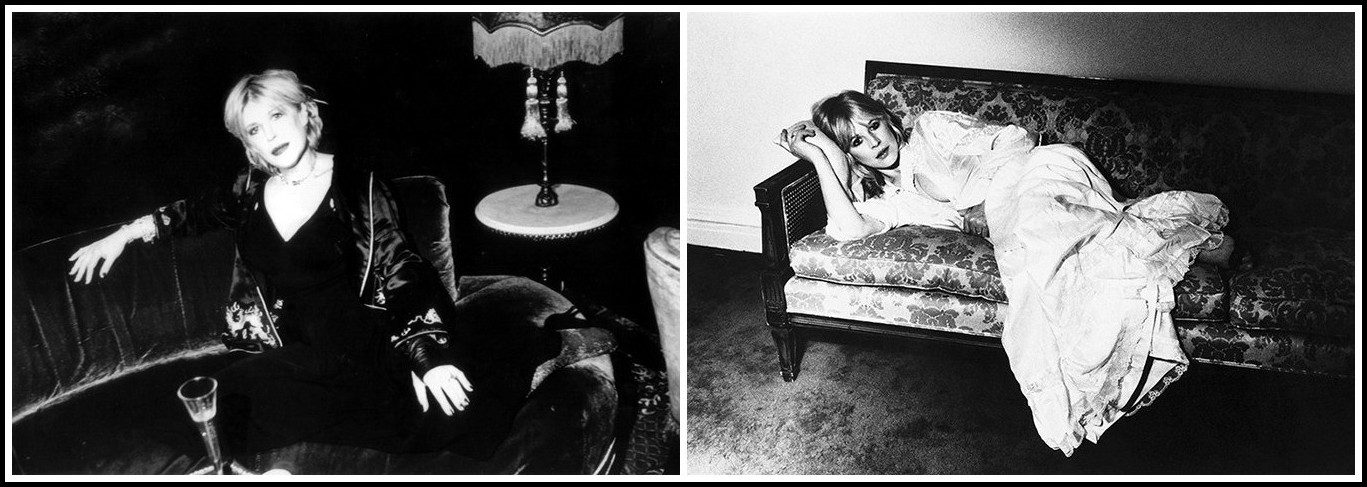

Marianne Faithfull | Ellen von Unwerth, c. 1990 | Scott Heiser, 1980

This, I believe, is the appeal of all ‘dark art’: it offers an echo of our inner tragedies, tragedies the outside world cannot accommodate. And, as most of us sacrifice our individuality to achieve oneness-with-the-world, ‘dark art’ is necessarily a minority art. Indeed, reminding us of our vulnerability, it restores our individuality and puts our oneness-with-the-world at risk. Its beauties, as Marianne’s albums prove, are particularly intense, and thus reserved for those who find ‘fitting in’ not an option: beauty, unlike prettiness, induces terror: terror isolates.

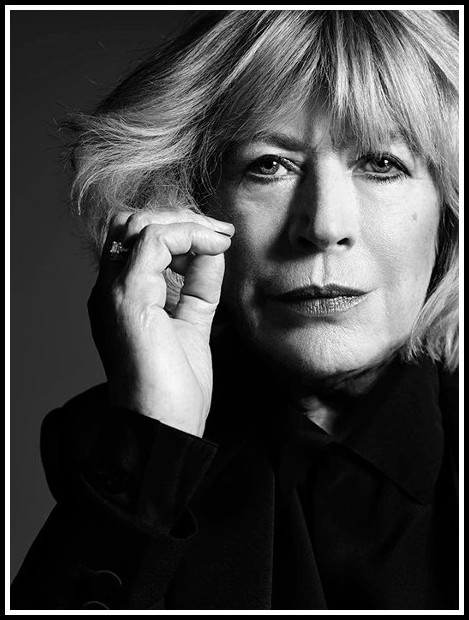

Marianne Faithfull | Hedi Slimane, 2014

Grief is a private experience, singular and secluding. Yet the paradox of ‘dark art’ is that, out of private grief, it creates a community of ‘fellow-feelers’, a shareable story of suffering. And it does this while heightening individuality, not sacrificing it: ‘Happy people are all alike; every unhappy person is unhappy in their own way’ (to paraphrase the narrator of Anna Karenina). To this community, this audience for ‘dark art’, Marianne’s music is enlivening. While others, imprisoned in their self-protection, are content in their pact with convention, those unafraid of vulnerability partake of the sublime.

Marianne Faithfull | George DuBose, 1987

III – MARIANNE FAITHFULL: EVERY SYMPTOM IS AN ATTEMPT AT SELF-CURE

In London, in St. Anne’s Court, behind the wall of a bombed-out building, Marianne Faithfull spent the 1970s. Addicted to heroin, she’d had enough of living in squats with junkies and had nowhere else to go.

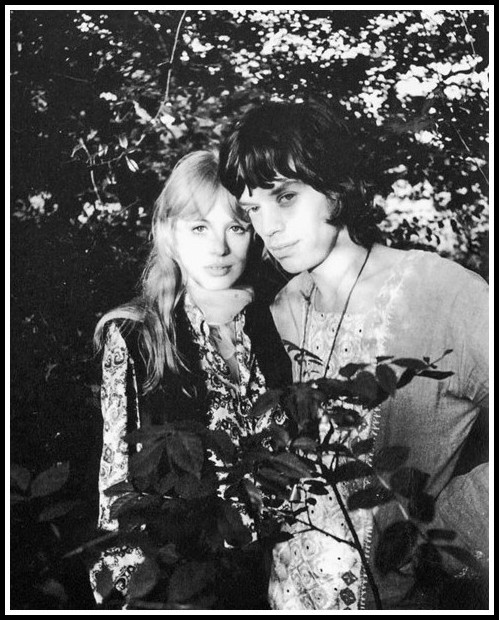

Marianne Faithfull | Terry O’Neill, 1973 | Terence Spencer, 1979

Before that she’d lived in a gilded cage, Mick Jagger by her side. Yet she felt hollow, despite Mick’s love and vitality, and decided to blank out her natural spirit with heroin. (Eventually, of course, Marianne left Mick, despite the majesty of ‘Wild Horses’ that he wrote to make her stay.)

Marianne Faithfull & Mick Jagger | Michael Cooper, 1967

If addiction is a symptom, and every symptom an attempt at self-cure, of what was Marianne attempting to cure herself? In an interview she spoke of her ‘loneliness, emptiness, futility, absolute repressed fury—you cannot say anything, if you told anyone what you felt, they would be consumed on the spot; so what the addict does, what I did, is take it out on myself’ (Marianne Faithfull: Dreaming My Dreams; Eagle Vision DVD, Paris 1999). But why, one may wonder, the ‘loneliness, emptiness, futility, absolute repressed fury’? ‘Why not?’ might be the better question. May as well ask why one can’t find the right size to be in the universe: ‘We are so small between the stars, so large against the sky’ (Leonard Cohen, ‘Stories of the Street’). For Marianne’s audience, the answer is within themselves, and its ideal expression is her music.

Marianne Faithfull | Clive Arrowsmith, 1981

Other mothers have had their children taken from them, have succumbed to heroin, have lived on the street. Other women have suppressed their selfhood, diminished their ambition, melted into the scene (whether swinging London, like Marianne, or sedate suburbia, like Lucy Jordan). Marianne is among the few (Nico being another, though less fully realized) who have forged from such experience a body of work that is sublime in its beauty: heroic, mysterious, numinous. And her sublime is not derived from a romantic imagination, but fashioned from everyday tensions inherent in the experience of being human: the ability to risk the subversiveness of kindness, to bear vulnerability, to assert one’s individuality in the face of conformity.

Marianne Faithfull | Don McCullin, 1980 | Julian Broad, 2007

‘She’s Got a Problem’ was another new song Marianne and the band performed at that 1978 concert in London. Let’s divide the world once more, this time between those whose experience problematizes their humanity and those for whom being human is unproblematic. An impossible division, you might say: everybody’s got a problem, everybody experiences the difficulty of living. True. But how many, in facing up to that difficulty, risk their skin in refusing the comfort of the crowd? Go to a Marianne Faithfull concert and count them. Or sum up her record sales. This will give you an idea of the proportion. For my part, when I saw Marianne again, in 2007 at the Halle aux Grains in Toulouse, I knew we were not many, but we were the happy few.

Marianne Faithfull | Detlev Schneider, 1998 | Paolo Roversi, 2009 | Peter Nicholls, 1997

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments