The Primitive of Everyone Else’s Way

GAUGUIN, CÉZANNE, THE PRIMITIVE AND SYMBOLISM – PART 1

Richard Shiff

Posted by kind permission of Richard Shiff, Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art at The University of Texas at Austin; Director of the Center for the Study of Modernism.

From Richard Shiff, ‘The primitive of everyone else’s way’ in Gauguin and the Origins of Symbolism, editor Guillermo Solana

(London: Philip Wilson Publishers in association with Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza and Fundación Caja Madrid, 2004) 65-71

THREE EPIGRAPHS

Edouard Vuillard, Portrait of Cézanne | Text: Paul Cézanne, 1904, quoted by witnesses

Pissarro, Portrait of Gauguin (detail) | Text: Paul Gauguin, 1890, quoted by Charles Morice

Odilon Redon, Portrait of Paul Sérusier, 1903 | Text: Paul Sérusier, 1905

I. INTRODUCTION

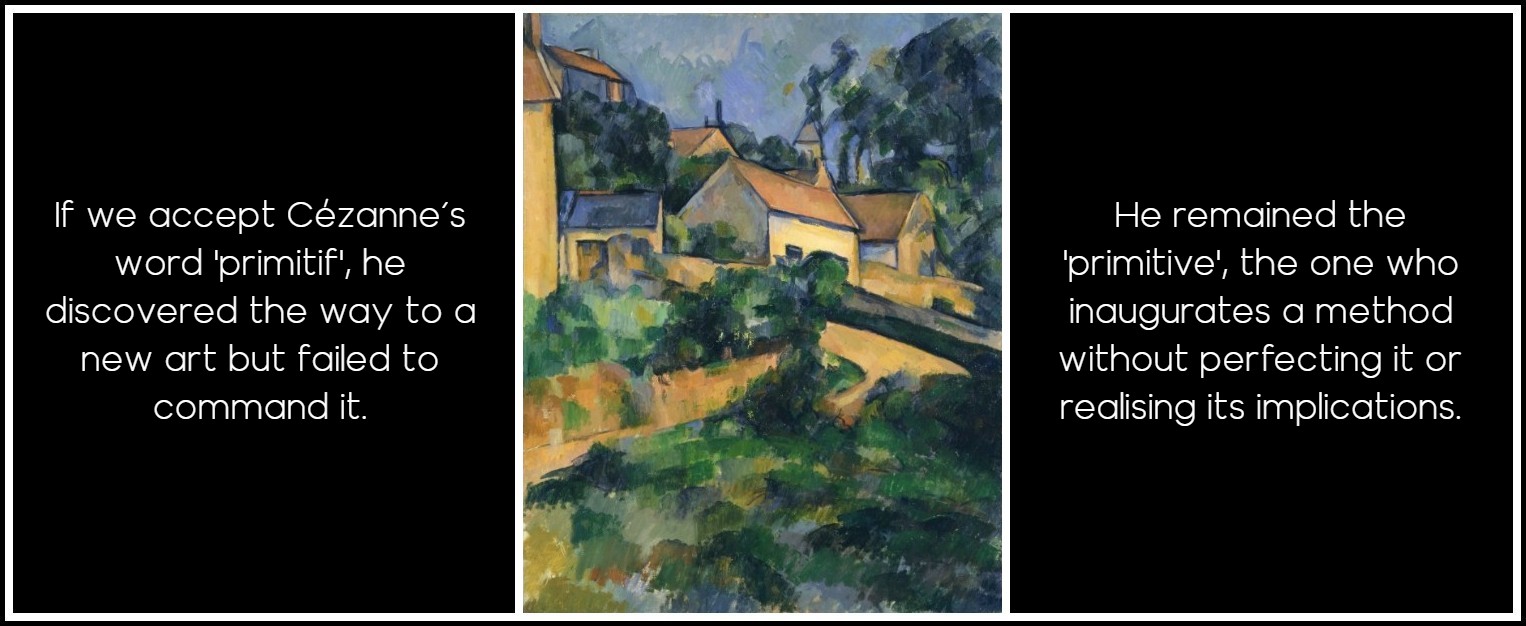

If we accept Cézanne’s word primitif, he discovered the way to a new art but failed to command it. He remained the ‘primitive’, the one who inaugurates a method without perfecting it or realising its implications. ‘Will I reach the goal I’ve sought so much and so long pursued’, he asked in September 1906, only a month before he died. ‘I’m working from nature as always, and I think I’m making some slow progress.’ Cézanne continued to distrust his results, leaving many canvases in an unfinished state. In this respect his progress was as ‘slow’ as he claimed. Perhaps his sense of ‘working from nature’ prevented him from proceeding along the path he had already cleared. Doubting his innovations but never questioning his definition of painting—‘the concrete study of nature’—Cézanne may have misconceived the significance of the art that his years of practice gradually brought into being. From Gauguin’s position, Cézanne’s painting represented human feeling, not nature.

Cézanne, Winding Road at Montgeroult, 1898

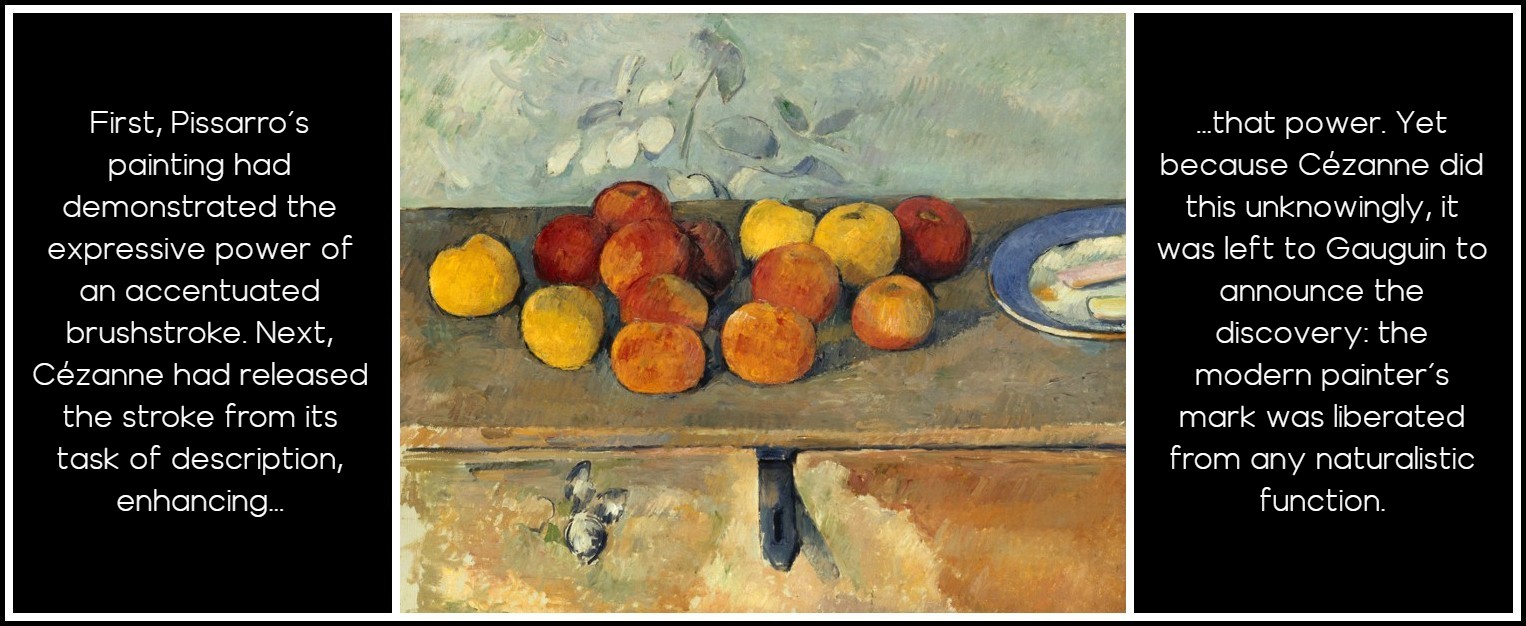

In 1905, Paul Sérusier suggested as much when he responded to a survey not only on Cézanne but also on Gauguin, who had died in 1903. His statement offered a condensed history of Symbolism in modern art. First, Pissarro’s painting had demonstrated the expressive power of an accentuated brushstroke. Next, Cézanne had released the stroke from its task of description, enhancing that power. Yet because Cézanne did this unknowingly, it was left to Gauguin to announce the discovery: the modern painter’s mark was liberated from any naturalistic function, like the primitive artist’s mark, which was ‘primitive’ by the very fact that it never developed analogous concerns. No longer in the service of nature—to the contrary, served by nature—modern painting had now established a direct link to the imagination and its associated emotions. In words of his own, Sérusier repeated the lesson of Gauguin’s Cézanne: ‘He is a pure painter. Of an ordinary painter’s apple, you say “I could take a bite out of it”. Of Cézanne’s apple, you say “How beautiful!”.’ With the viewer responding emotionally to a specific configuration of line and color, the sensation of beauty—or simply sensation itself—became the primary meaning of Cézanne’s form. His ’apple’ was not an apple to eat, but an imaginative fantasy to dream. In the Symbolist painting that Gauguin and Sérusier conceived, dreaming replaced eating and every other banal aspect of existence. Such a condition changes the quality of living.

Paul Cézanne, Apples and Biscuits, 1880

II. HARD TO LIVE

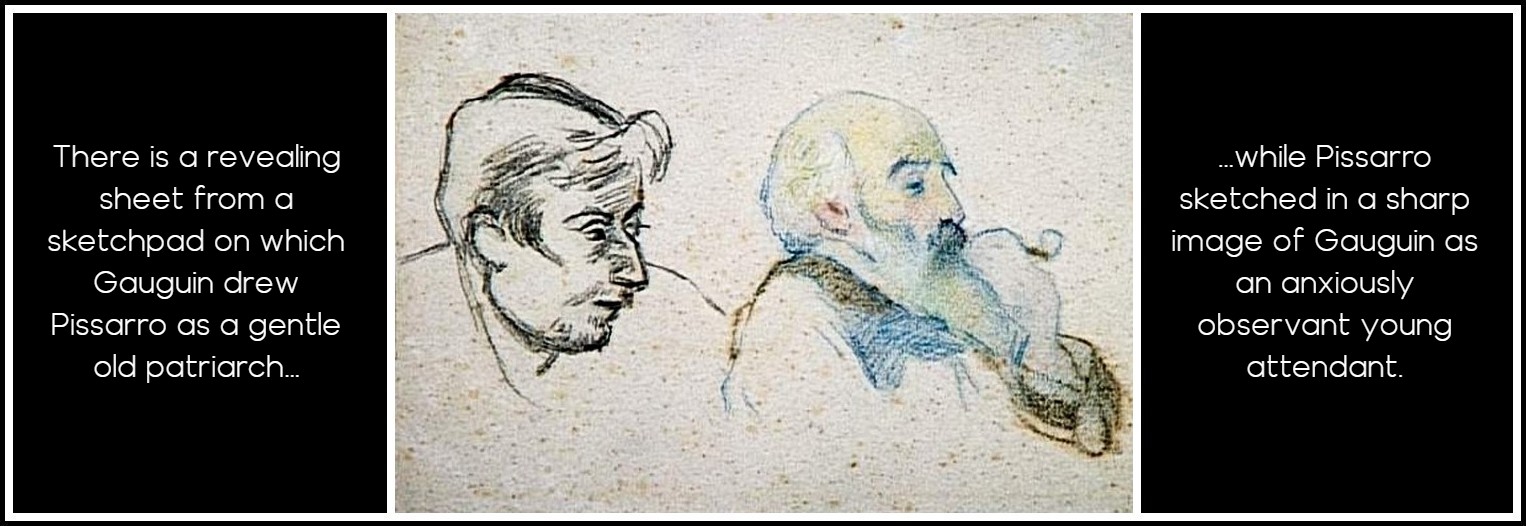

[Pissarro invited Gauguin to spend the summer of 1879 with him in Pontoise. It was exactly what Gauguin needed, a period of consistent work on his art with a little gentle guidance. That summer, as the two men worked side by side, out in the fields, Gauguin absorbed the Impressionist technique from the perfect guide, a man who did not attempt to dragoon his junior into a set style but let him take what he felt he needed.1]

1 – David Sweetman, Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1995) p. 91

Gauguin & Pissarro, Portraits réciproques, 1880 [Text: David Sweetman, Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life, p. 90]

[The relationship between Gauguin and Pissarro was that of patron to teacher…

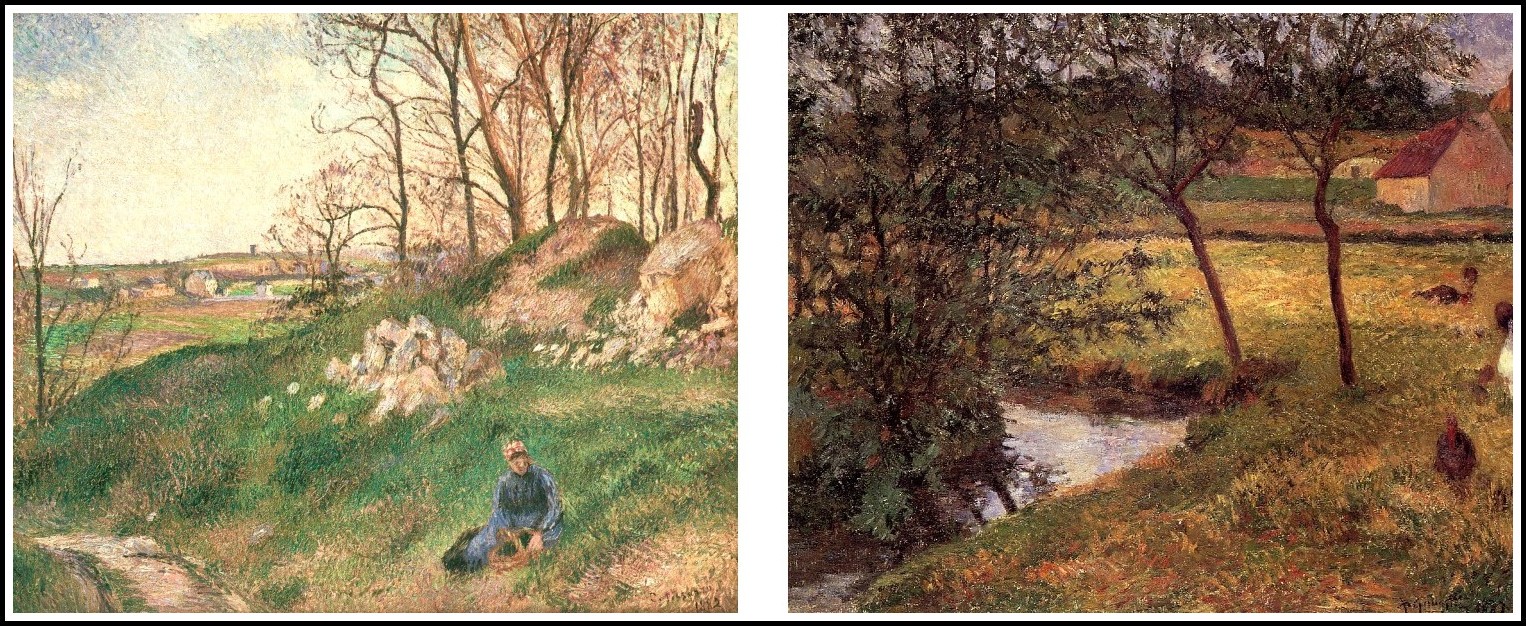

Pissarro, The Quarry at Le Chou (Pontoise), 1882 | Gauguin, Les Saules, 1883

…with both needing the other to continue their work.1]

1 – David Sweetman, Paul Gauguin: A Complete Life (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1995) p. 90

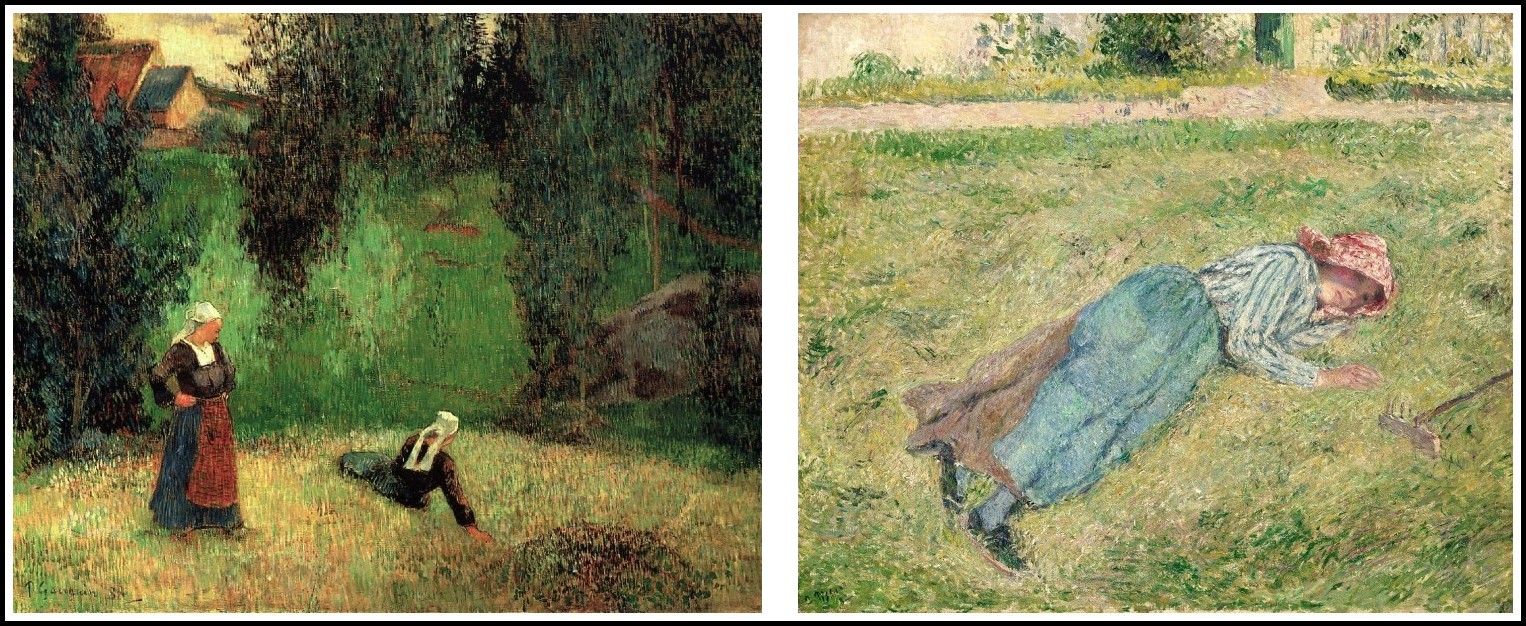

Gauguin, Spring at Lézaven, or The First Flowers, 1888 | Pissarro, The Rest: Peasant Girl Lying on the Grass, 1882

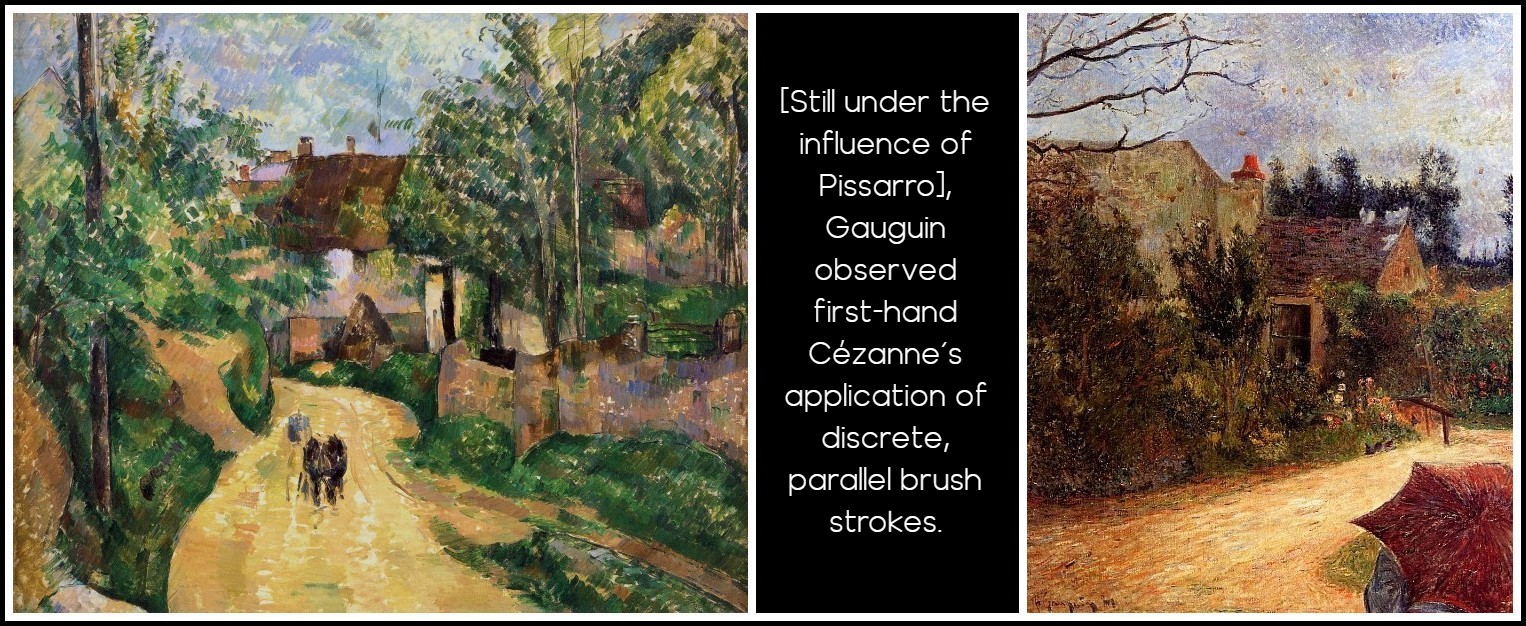

Gauguin’s interest in Cézanne developed when he painted beside both Pissarro and Cézanne at Auvers in 1881, observing first-hand Cézanne’s application of discrete, parallel strokes. (This interest was never reciprocated: Cézanne disapproved of the linear ‘abstraction’ and unmodulated colour apparent in the style Gauguin derived from him.)

Cézanne, Winding Road in Valhermeil (Auvers-sur-Oise), 1881 | Gauguin, Pissarro’s Garden (Quai du Pothuis, Pontoise), 1881

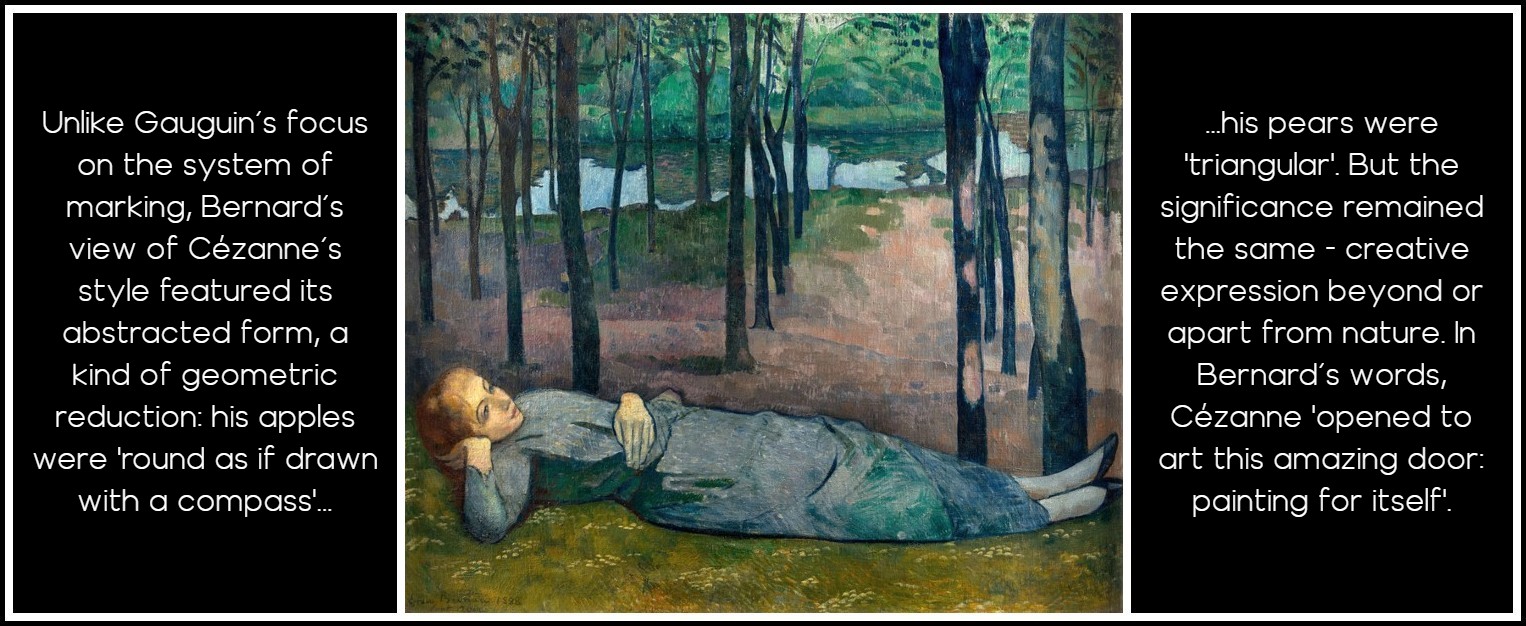

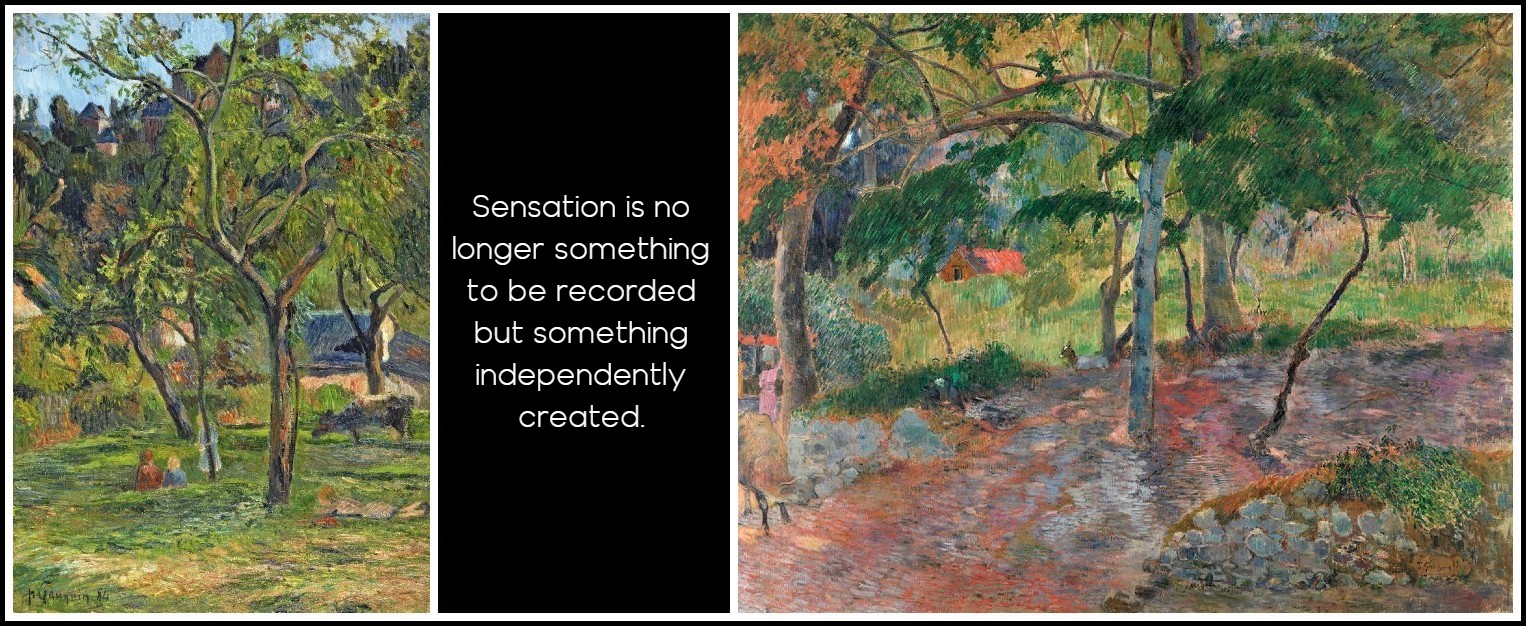

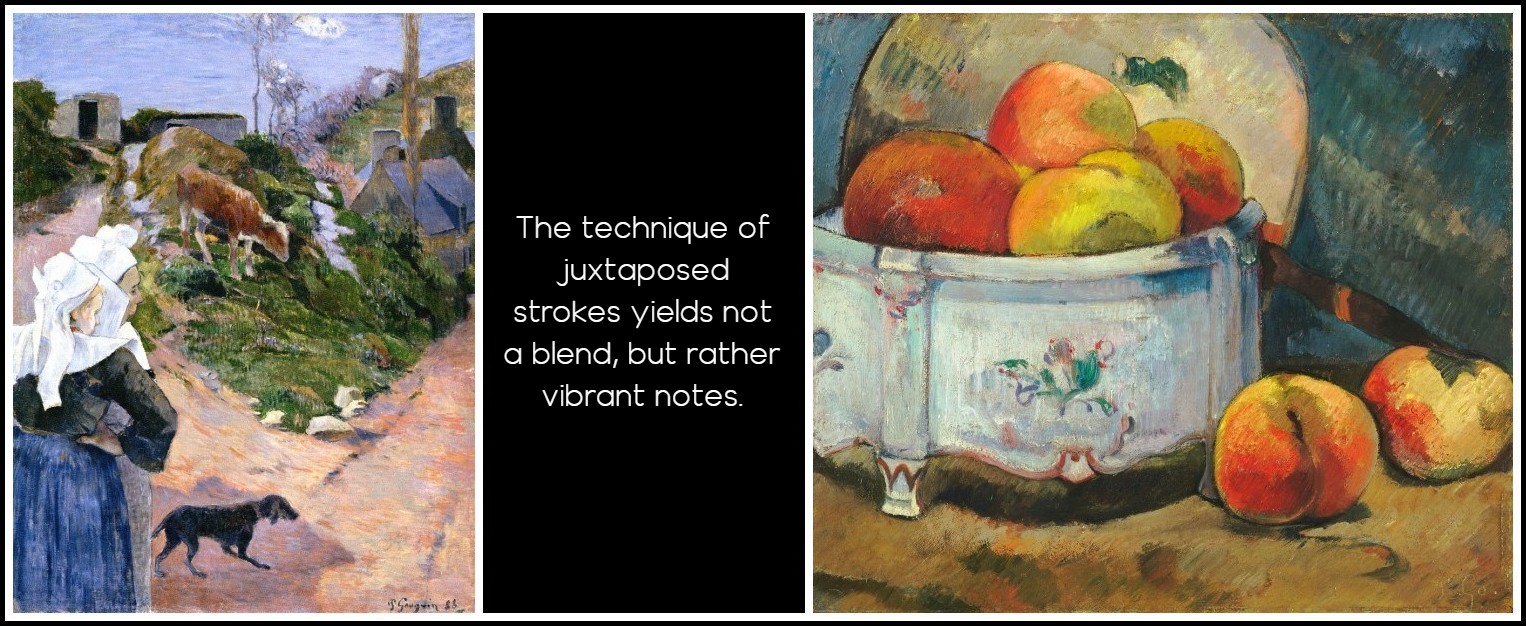

Whatever Cézanne happened to do and say in 1881 led Gauguin to understand the separate, juxtaposed marks as the painter’s successive ’sensations’. Gauguin either adopted, appropriated, or stole Cézanne’s technique—the choice of verb would depend on the attitude or allegiance of whoever was telling this story—and along with Cézanne’s mark came his sensation. ‘Forthright, uniform, supple, and grand’, was Maurice Denis’s description of Gauguin’s own brushstroke; and he added immediately that its character had been ‘acquired evidently from Cézanne.’ ‘Gauguin, absolutely the first in this respect, had a limitless admiration for Cézanne.’ Gauguin perceived that the patterning of Cézanne’s side-by-side marks, their orientation in relation to the picture surface, did not necessarily follow the volumetric contouring of the cultivated fields, the trees, or the still-life objects being represented. An apple was round; its constituent marks might be vaguely rectilinear. Beyond the fact that Cézanne’s technique defied the conventions of naturalistic imitation, it bore a remarkable implication: ‘sensation’ was no longer something to be recorded (as a view or ’study’ of nature) but something independently created (as the painter’s internalised vision or dreamlike, imaginative projection [rêve]). This was noted by Emile Bernard, who in 1891 became the first to devote an interpretive essay to Cézanne; like Sérusier, Bernard had been a member of the ‘School of Pont-Aven’ during the late 1880s (see Madeleine in the Bois d’Amour, 1888). He developed his interest in Cézanne prior to meeting Gauguin, but Gauguin caused that interest to deepen. Unlike Gauguin’s focus on the system of marking, Bernard’s view of Cézanne’s style featured its abstracted form, a kind of geometric reduction: his apples were ‘round as if drawn with a compass;’ his pears were ‘triangular’. But the significance remained the same—creative expression beyond or apart from nature. In Bernard’s words, Cézanne ‘opened to art this amazing door: painting for itself.’

Émile Bernard, Madeleine au Bois d’Amour, 1888

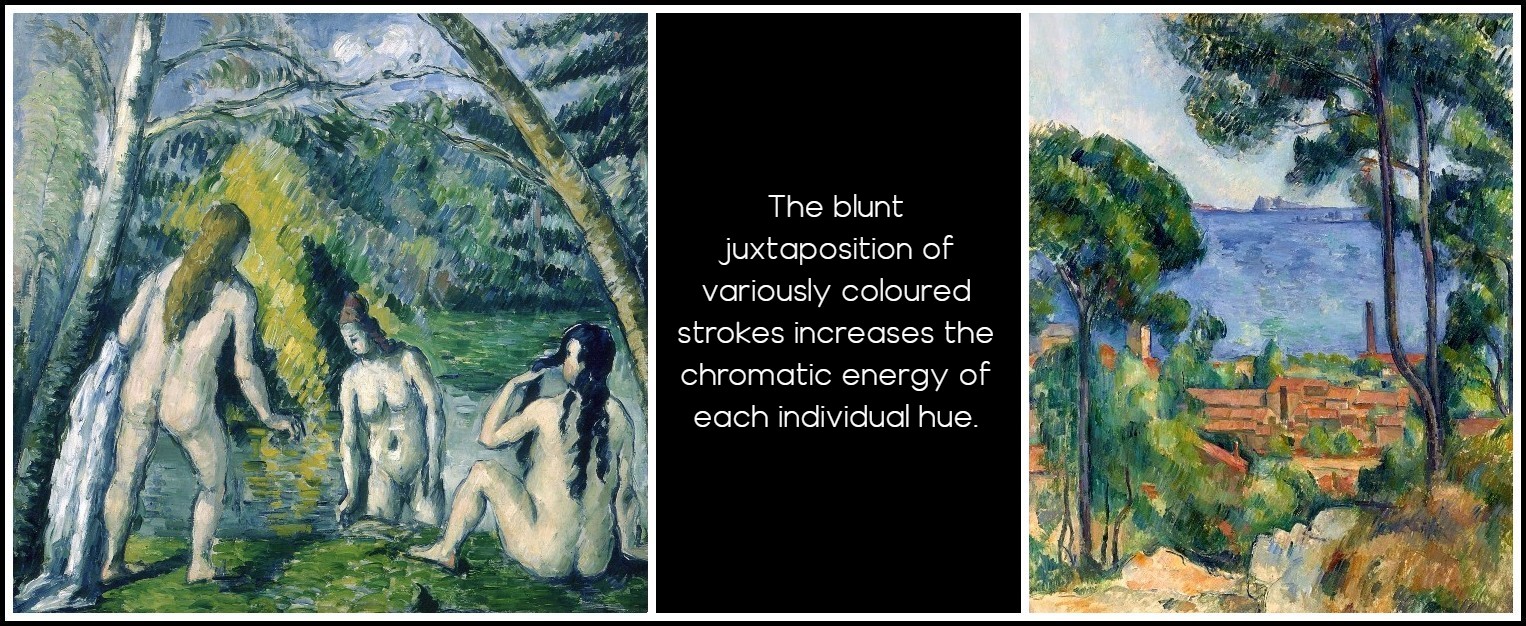

The blunt juxtaposition of variously coloured strokes (the feature Gauguin stressed) was much more insistent in Cézanne’s painting than in Pissarro’s. This increased the chromatic energy of each individual hue; accordingly, Cézanne’s imaginative vision became that much more moving, its emotional force intensified. The effect that Cézanne produced in Three Bathers (c.1879-1882) or View of L’Estaque (c.1883-1885)…

Cézanne, Three Bathers, c.1879-1882 | Cézanne, View of L’Estaque, 1883-1885

…Gauguin self-consciously adapted to his own expressive purposes in An Orchard Below the Church of Bihorel (1884), River Under the Trees (1887)…

Gauguin, An Orchard below the Church of Bihorel, 1884 | Gauguin, River under the Trees, 1887

…Breton Women by a Bend in the Road (1888), and Still Life with Peaches (c.1889). In 1885 Gauguin reflected on his new practice, indicating that the technique of juxtaposed strokes was at its core: ‘People complain about our unblended colours, set one against the other. Yet a green beside a red does not yield a reddish brown, as in physical mixture, but rather two vibrant notes.’

Gauguin, Breton Women by a Bend in the Road, 1888 | Gauguin, Still Life with Peaches, 1889

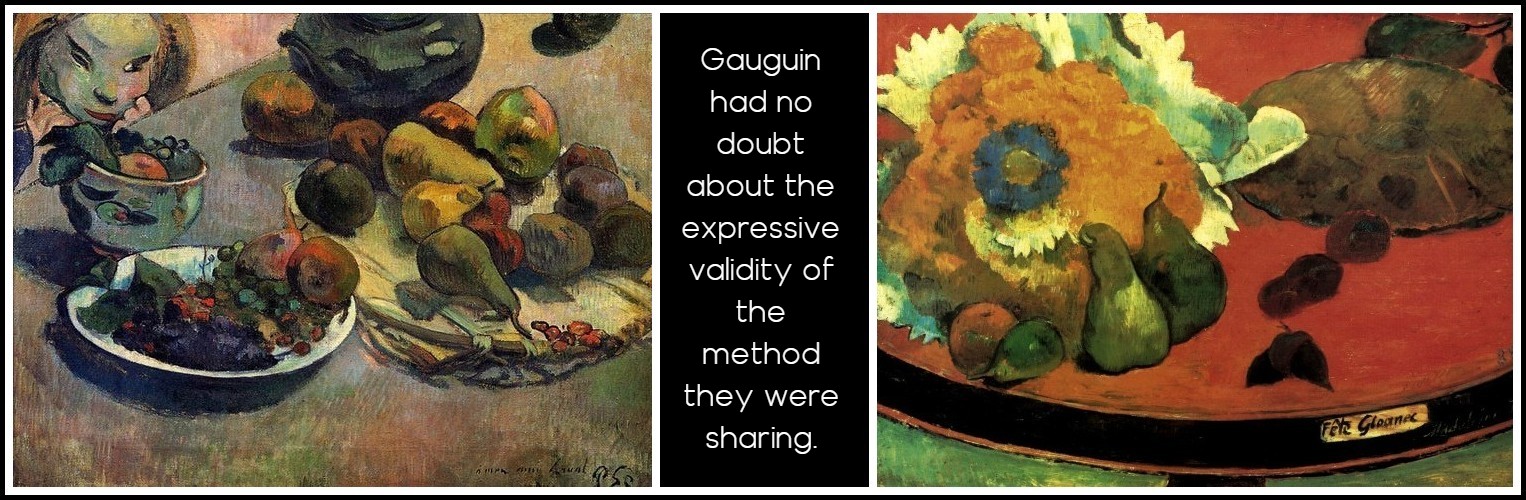

At issue in Gauguin’s response to Cézanne were two distinct but related applications of the concept of the primitive (or primitiveness). First, the term would be applied to art that possessed qualities associated with ‘primitive’ expressiveness (often linked in turn to the native societies that Europeans were colonising). Second, it would designate the ‘primitive’ status of the initiator of any radically original form of art (from anonymous Egyptian sculptors, to Gothic stonemasons, to Giotto, to Cézanne himself). In Gauguin’s view, Cézanne was at least doubly primitive. He was the ‘primitive’ of something more than a new technique or type of form; he had invented a new kind of artistic expressiveness. Or perhaps he had redeemed an old, exhausted naturalistic art, returning it to a fecund state of savagery, recovering its wildness. A stubborn Cézanne never seemed to grasp what he had done. Only Gauguin understood the potential significance of the achievement. Unlike Cézanne, he had no doubt about the expressive validity of the method they were sharing.

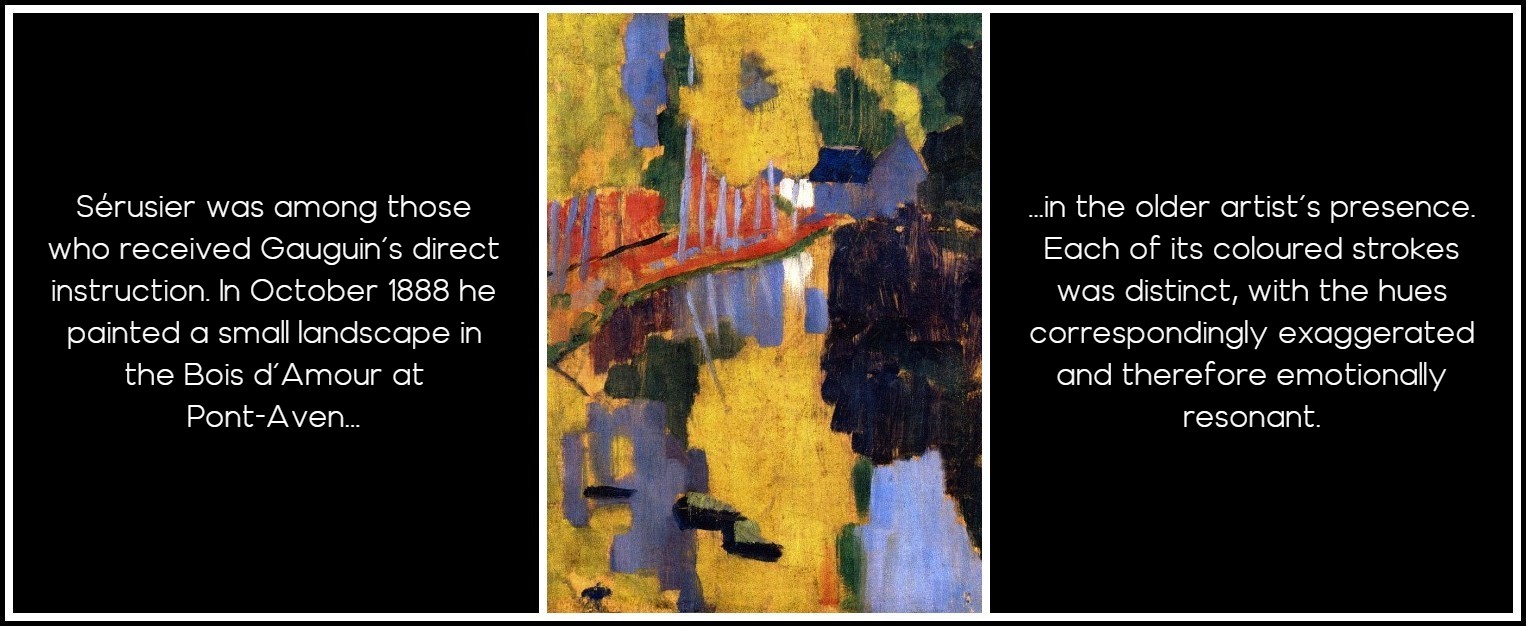

Gauguin, Still Life with Fruit, 1888 | Gauguin, Still Life: ‘Fête Gloanec’, 1888

By the late 1880s,Gauguin had purchased several Cézannes for his personal collection and was proclaiming Cézanne’s genius to anyone who would listen. His impromptu lessons emphasised that the technical details of painting, when sufficiently liberated from illustrational requirements, would convey emotional and psychological force independent of formulaic narrative and thematic content (which he called ‘literature’, or superficial anecdote). According to Gauguin, the motivation for primitive art was spiritual, speculative, and above all emotional. Primitive art had its origin in the mind and its expression proceeded directly through colour and form as much as through the freely imagined subjects that transformed an artist’s mundane experience of nature. All this was to be clearly distinguished from the empirical and utilitarian concerns that guided the realism of conventional painting and sculpture. Sérusier was among those who received Gauguin’s direct instruction, especially in October 1888 when he painted a small landscape in the Bois d’Amour at Pont-Aven in the older artist’s presence. Each of its coloured strokes was distinct, with the hues correspondingly exaggerated and therefore emotionally resonant. Sérusier’s painting (which remained unfinished) came to be known as the Talisman, because he used it to convey the understanding—beyond any ordinary words and beyond ‘literature’—that Gauguin, his ‘liberator’, had conveyed to him. Sérusier would later say of Cézanne: ‘He cannot be described with words. He is too pure a painter.’ Gauguin had probably said something very similar.

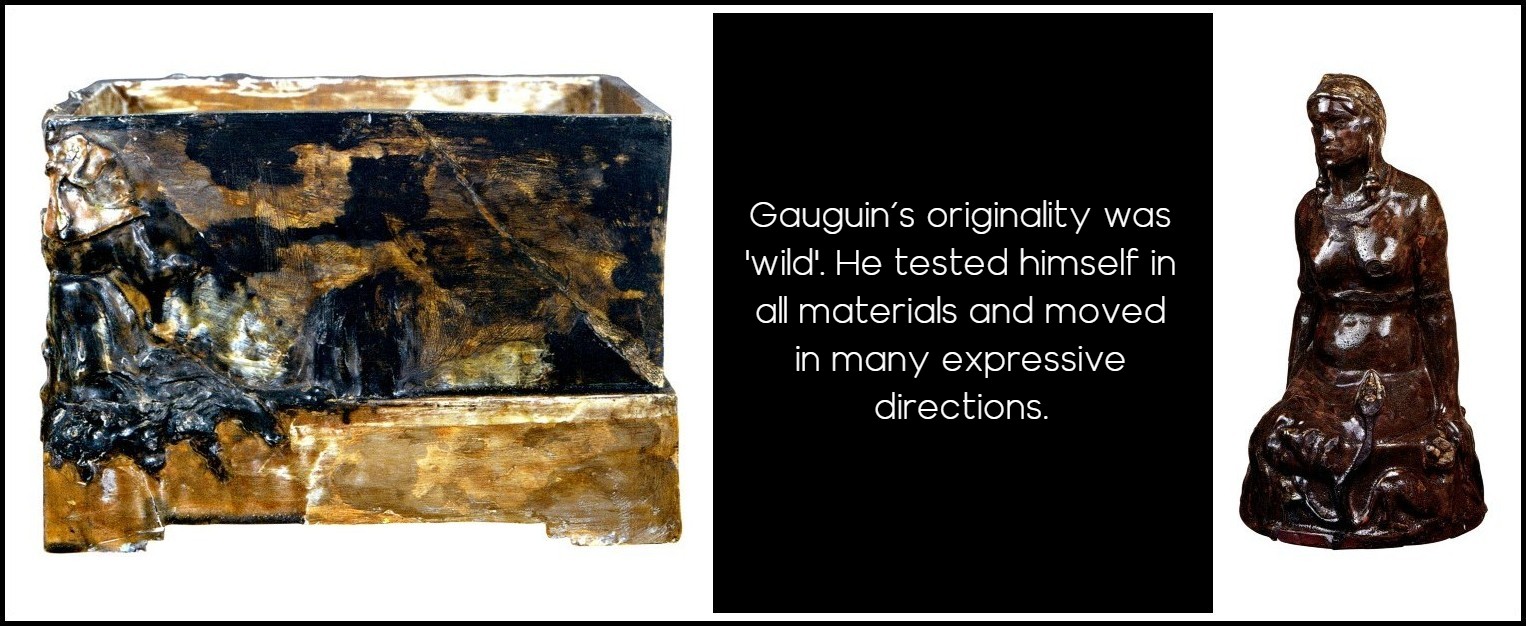

Paul Sérusier, Le Talisman: Paysage au Bois d’Amour, 1888

Despite the acknowledged chain of leadership (from Pissarro the Impressionist, to Cézanne the anti-Impressionist, to Gauguin the Symbolist, and finally to Sérusier, Bernard, Denis, and their associates), Gauguin never received unqualified approval, perhaps because he was truly ‘wild’(sauvage). This was a description he often applied to himself: ‘Puvis de Chavannes is Greek [civilized] whereas I am a savage, a wolf in the woods without a collar.’ ‘Puvis explains his idea’, Gauguin insisted; and it was an idea that corresponded to a preexisting symbol (in effect, Puvis was an allegorist). But Gauguin painted his idea, discovering its symbolic form as he proceeded. His identification with the wildness of the proverbial wolf suggested a lack of social constraint or socialisation. More significantly, wildness connotes imaginative freedom: ‘let your thoughts run wild’, we sometimes say; and uncharted, untamed land is called wilderness or simply ‘the wild’. A man in the wild, un sauvage, is not out of control, although he may be uncontrollable. In this sense, Gauguin’s originality was ‘wild’—unbounded and impossible to comprehend. He tested himself in all materials and moved confusingly in many expressive directions (see Window Box with Breton Scenes (1886); Black Venus (1889).

Gauguin, Window Box with Breton Scenes, 1886 | Gauguin, Black Venus, 1889

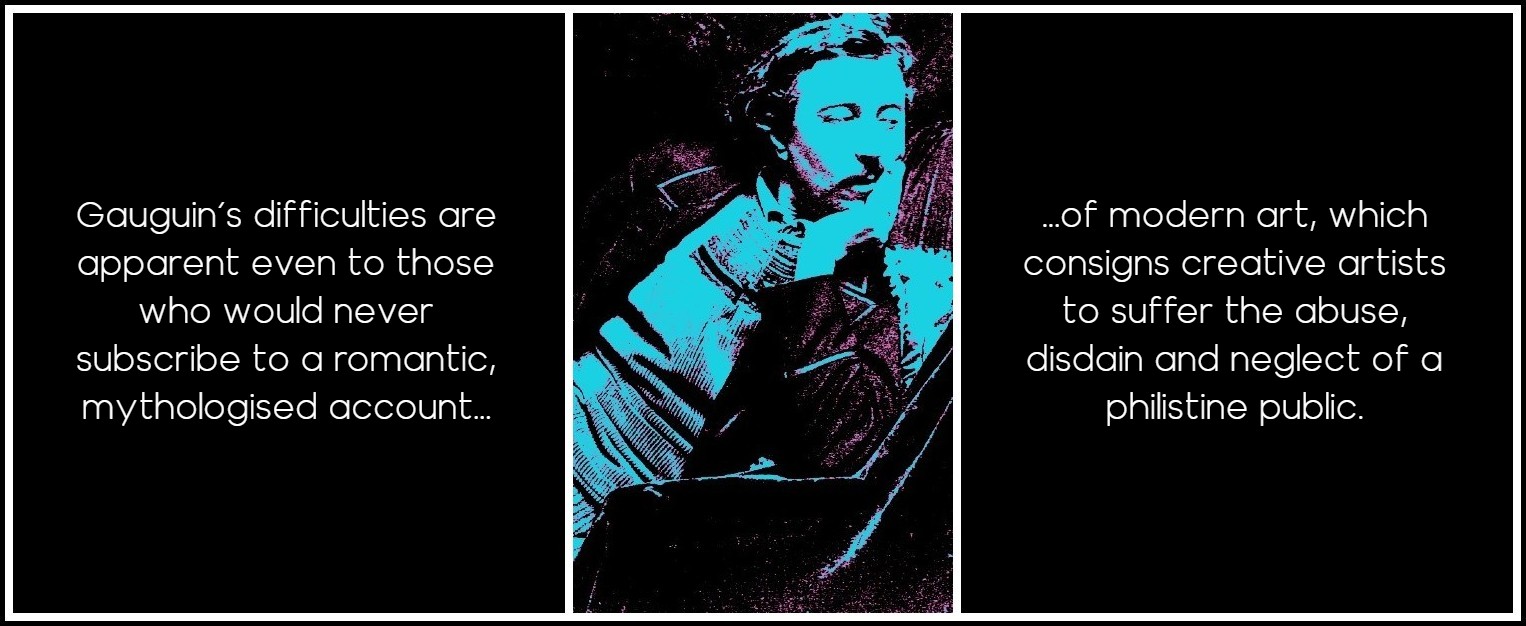

Odilon Redon described Gauguin as ‘full of gifts, capriciously expressed in diverse mediums. Do not look for perfection in Gauguin because the powerful stream of his production prevents him from achieving it.’ Cézanne denied himself success because of nagging doubts about how his painting related to nature. Ironically, having set external nature aside in order to free his imaginative forces, Gauguin may have failed because of his own hyperactivity. Meeting continual resistance to his multifaceted creative provocations, he led a hard life. For him, living was difficult—just living. Gauguin’s difficulties are apparent even to those who would never subscribe to a romantic, mythologised account of modern art, which consigns creative artists to suffer the abuse, disdain and neglect of a philistine public. Charles Morice—Gauguin’s literary collaborator, eventual biographer, and something of a mythologizer—dated the artist’s ‘solitude and misery’ to the day he decided to end his career in finance and devote his life to painting. Although unusually resourceful in managing his new art career, Gauguin was nearly always in debt and often felt betrayed by the dealers, collectors and critics he believed were controlling his market. His habitually aggressive behaviour negated the benefits of his charisma and charm. Appraising his qualities in 1903, Denis listed his ‘inexhaustible imagination’ but also his ‘spitefulness’ and ‘capacity for alcohol.’ Gauguin, in other words, tended to get into fights. He cultivated lasting friendships with fellow artists and writers, but generated just as many cases of enmity.

Gauguin in a Breton Waistcoat, 1891 | Photo: Boutet de Monvel

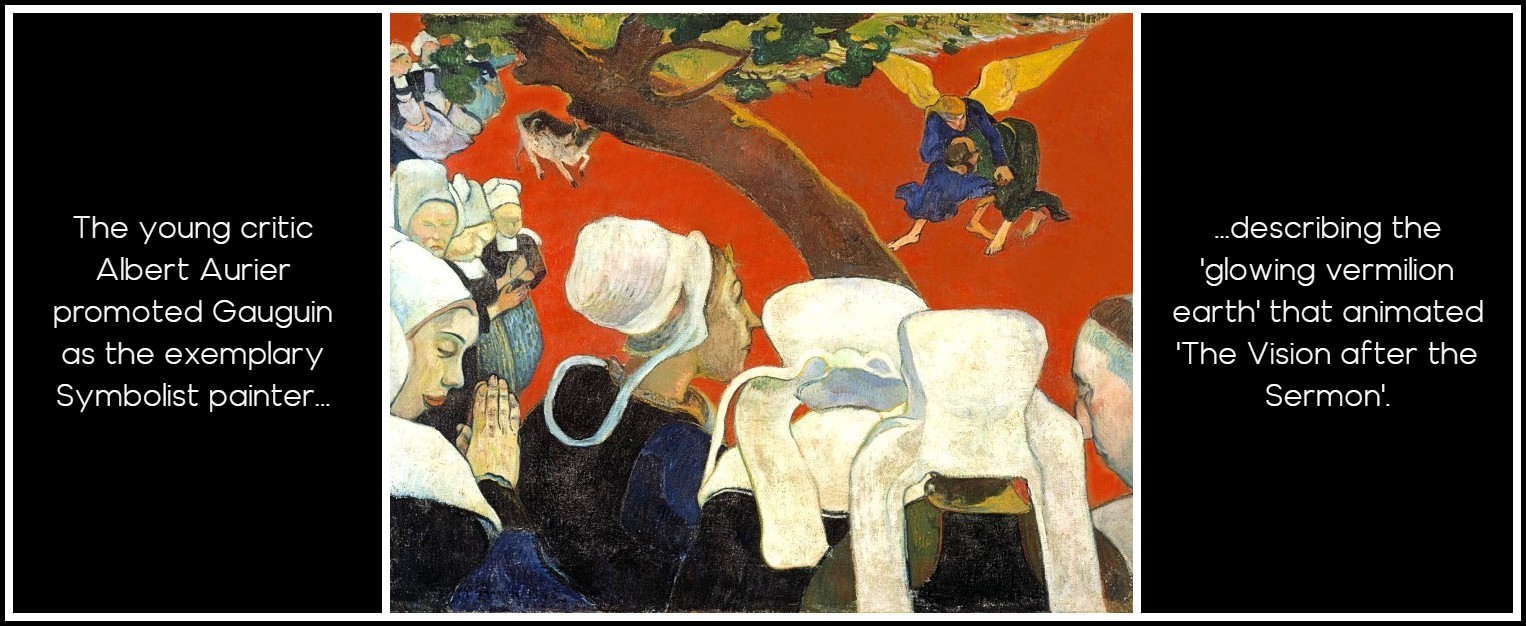

Luck often turned against Gauguin, even when it seemed to be with him. After a disappointing response to two exhibitions of his work in 1889, he found a source of enthusiastic support in the young critic Albert Aurier, a friend of Sérusier. In the March 1891 issue of Mercure de France, Aurier promoted Gauguin as the exemplary Symbolist painter, describing the ‘glowing vermilion earth’ that animated The Vision After the Sermon and calling its creator ‘the initiator of a new art who knows how to read the abstract meaning in every object in nature.’

Gauguin, The Vision after the Sermon, 1888

Aurier’s second article on Symbolist painters (April 1892) reconfirmed Gauguin’s Symbolist identity, characterizing his art as ‘Platonism plastically interpreted by a wild man of genius.’ Gauguin, so to speak, was a genius in ‘the wild.’ At that time, he was on his first visit to Tahiti (April 1891 to July 1893),where he was enacting the theoretical links between primitif, sauvage and Symboliste. Calling Gauguin a Platonist made him appear more philosophical and programmatic than he was, but Aurier’s position was true to the artist in stressing as the source of his expression imaginative fantasies, dreams and emotionally evocative ideas, as opposed to delimited observations of the external environment. Having received word in distant Tahiti that Aurier was continuing to praise him, Gauguin was inspired to proclaim his Symbolist leadership even more boldly: ‘I created this movement in painting and many young artists benefit from it. Nothing in them comes from them; it comes from me.’ In October 1892, however, Aurier died suddenly from typhoid fever; and Gauguin lost his most effective literary aIly. Aurier’s successor at Mercure de France was Camille Mauclair, who would declare that Gauguin’s theoretical statements on the topic of pictorial expression were ’as naïve as they are useless’. In this respect, Gauguin’s theory was hardly different from his pictures: ‘His dogs painted red, his cabbage-green trees, his pink skies.’ To Aurier such exaggerated, simplified color conveyed the kind of ‘abstract meaning’ he advocated, ‘the ever-changing drama of abstractions’—pure ideas, symbols, at once intellectualised and spiritualised. To Mauclair, these claims were nonsense.

Albert Aurier | Camille Mauclair

Aurier may have impressed Gauguin, but many others were either puzzled by or actively refuted his analysis. Among them was Pissarro, whom Aurier faulted (along with Impressionism in general) for concentrating on the material aspects of reality. Pissarro, in turn, took offense at the critic’s use of the concept of émotivité, which, for an artist, is both a sensitivity to emotional stimulation and the capacity to project emotion. Aurier identified Gauguin with émotivité, while implying that Pissarro lacked it. With regard to subjectivity or emotional content, Pissarro saw little fundamental difference between the old Impressionism and the new Symbolism; both were, or should be, imaginative in their content, individualistic yet fully rational in their technique. Pissarro presented the matter to his son Lucien, who observed that émotivité was just another word for what the Impressionists had always called ‘sensation’—an impassioned, personalised, emotional act of perception. Pissarro inferred from Aurier’s ‘Le Symbolisme en peinture’ that with so much emphasis on intellectual musing and fantasy, art would lose its physical involvement with material form. It would become all conception and no execution, no work. Pissarro concluded that if Aurier’s position were taken to its inherent ‘absurdity’, artists would ‘no longer need to draw or paint.’ At one point, the writer Octave Mirbeau, friend of Pissarro and occasional supporter of Gauguin, encountered Aurier on the street: ‘I explained to him that you were a great idealist’, Mirbeau reported to Pissarro in December 1891. Mirbeau was implying that, like Pissarro, he failed to see any clear division between Impressionist and Symbolist ends. To this, as to all that Mirbeau asserted, Aurier placidly concurred, as if unable to articulate a contrary opinion. With the same sarcastic exasperation, Mirbeau suggested that ‘aII this Gauguinesque foolishness’ instilled in him the desire to contemplate ‘a cabbage leaf’. Cabbage was unpretentious, something familiar to ordinary working men, and a subject Pissarro treated with dignity.

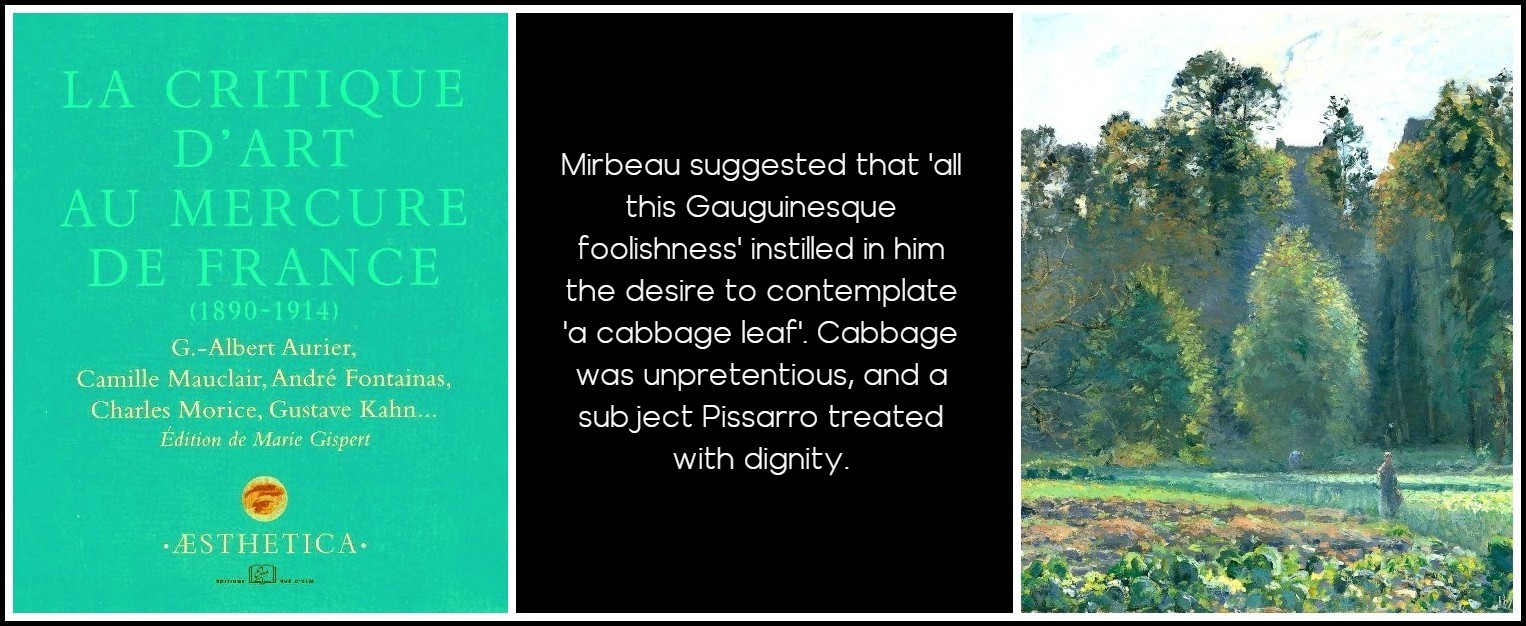

La Critique d’Art au Mercure de France (1890-1914) | Pissarro, Cabbage Field in Pontoise, 1873

CONTINUED IN PART 2 (SEE IMAGE LINK IN ‘RELATED POSTS’ BELOW)

RICHARD SHIFF: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments