Part 1 of 4

JAMES JOYCE AND AUBREY BEARDSLEY: AESTHETICS OF OBSCENITY

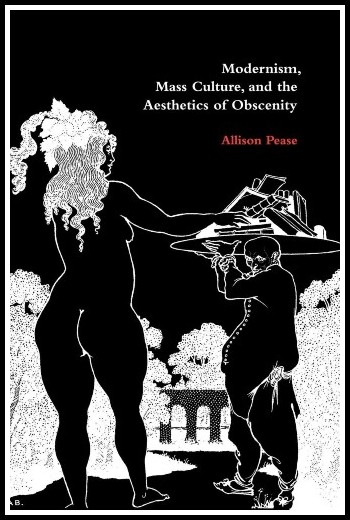

Allison Pease

Posted by kind permission of Allison Pease, Professor of English, Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York.

From Allison Pease, Modernism, Mass Culture, and the Aesthetics of Obscenity (Cambridge University Press, 2000) pages 72-83

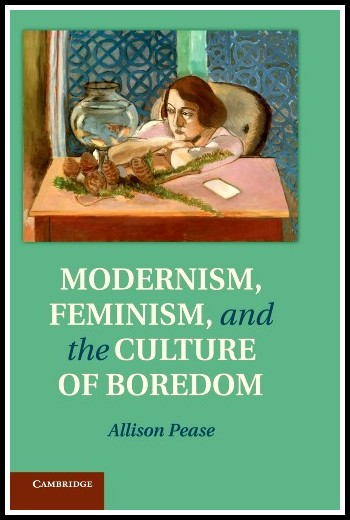

James Joyce, 1918 (Photo: Camille Ruf) | Aubrey Beardsley, 1896 (Photo: Henry Cameron )

I. DENOMINATIONS

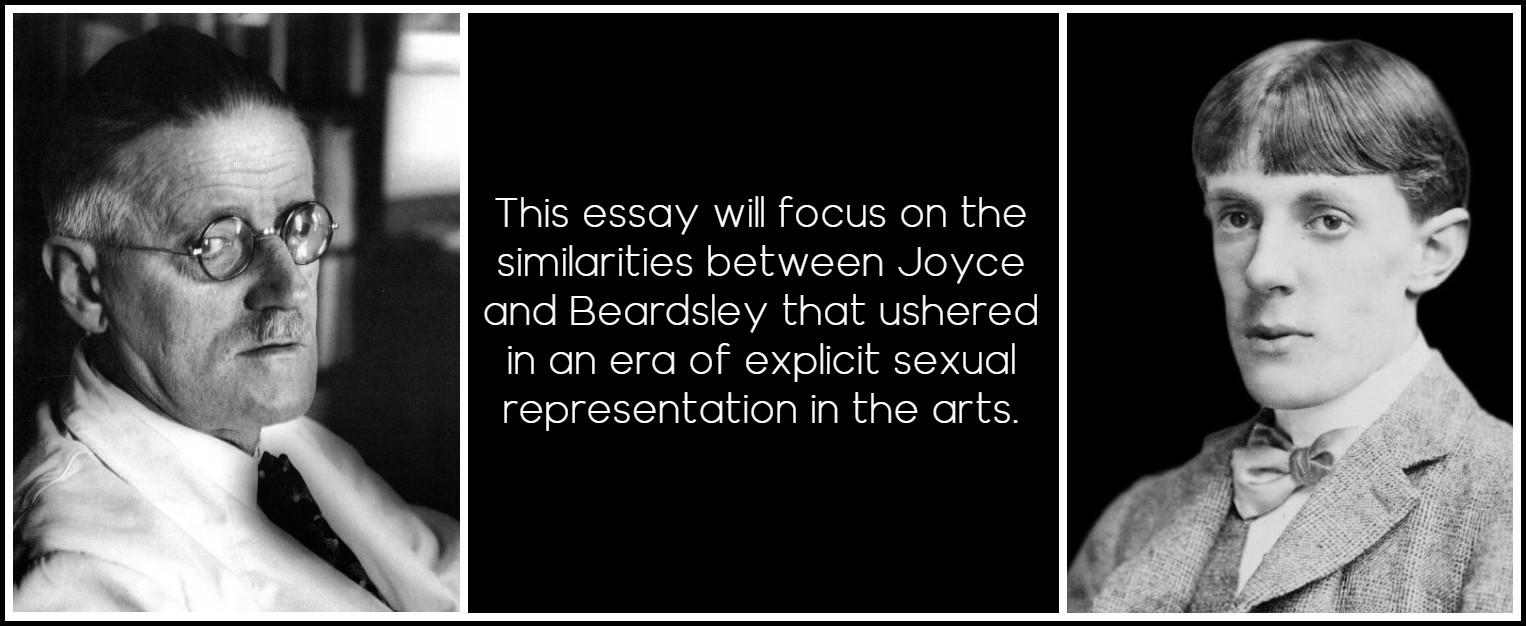

Aubrey Beardsley and James Joyce may at first glance seem unlikely partners in any aesthetic project. Beardsley was a pen-and-ink artist of small-scale drawings that reached their peak of popularity between 1895 and 1930, but have continued to enjoy a small, appreciative audience since, and Joyce was a writer of large-scale novels that have dominated literary thought throughout much of the twentieth century. Both, however, have enjoyed a particular success with the academy, the institution which in the twentieth century best represents upper-middle-class, high aesthetic tastes. Equally, both artists had a penchant for depicting explicit sexuality in their works. With these two connections in mind, this essay will focus on the similarities between these two artists that ushered in an era of explicit sexual representation in the arts.

James Joyce, 1937 (Photo: Josef Breitenbach) | Aubrey Beardsley, 1890 (Photo: James Russell)

In his 1925 book The Beardsley Period, art critic Osbert Burdett recognized the affinity between Joyce and Beardsley, and, after praising the ‘technical accomplishment’ of Beardsley’s works, reflected: It seems, too, hardly more than an accident of time that Ulysses was not published in the nineties. Its vast experiment would have interested them. They would have recognized the learning, and been beguiled by the effects, of its immense vocabulary. Even the absence of punctuation in the last chapter would have seemed to Beardsley, if not to Johnson, a legitimate experiment. In Burdett’s eyes the two artists are linked together not by the sexual content of their art, but by the technical experimentalism and cultural capital of their work. While Burdett may have tried to buttress his own scholarly seriousness by purposefully avoiding discussion of the content of the last chapter of Ulysses—Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in ‘Penelope’ was often labeled and censored as pornography in the 1920s and 1930s—his evasion is symptomatic of a larger movement to disavow the sexual content of art even as it was pressing more thoroughly against traditional aesthetic conventions. To him, and to many who legitimated Beardsley’s and Joyce’s work in the fin-de-siècle and the first decades of the twentieth century, their artistic competence is based on the formal qualities of the works and the cultural capital expressed in them; in other words, their ability to represent the codes of artistic integrity as defined by the high culture of their time.

Aubrey Beardsley & Oscar Wilde, Salome | Osbert Burdett, The Beardsley Period | James Joyce, Ulysses

Beardsley and Joyce were masters of aesthetic form. Each introduced into his works sexually explicit images and tropes that until their time could only be found in pornography.1 It is my contention that Beardsley and Joyce successfully incorporated the explicitly sexual tropes and images of pornography into their works even while cultivating reputations for these works as high art precisely because of their formal mastery over the material introduced. Critics were able to focus on form as enabling the aesthetic because Kant’s reification of the art object as autonomous expression through form dominated aesthetic thought in the final decades of the nineteenth and the first decades of the twentieth centuries. Kant’s Critique of Judgment concretized a high-cultural shift in the eighteenth century from viewing the art object as having an instrumental value (e.g., to delight and instruct) to viewing the art object as having an autonomous value, existing for the sake of its own internal perfection. As Kant’s aesthetic philosophy became culturally dominant in Britain in the latter half of the nineteenth century, form became the primary signifier of that which was considered beautiful, and hence high art.

1 – In Joyce’s case, some of the sexually explicit language he uses can be traced to medical tracts and advertising. The ‘Circe’ episode, for instance, is often linked to the medical writings of Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (1886). An explicit, genitally focused sexual discourse developed out of a medical-scientific discourse, enabling the pornographic genre. Such a discourse remained solely within the province of pornography and medicine until the early decades of the twentieth century.

Kant, Critique of Judgement, Oxford World’s Classics

Form, as opposed to any ‘charm’ that might induce a necessarily subjective and particular sensation or emotion in the viewer/reader, is according to Kant that which is capable of constituting a delight of reason that, apart from any concept, is universally communicable and so capable of forming a judgment of taste. Form in this sense should be understood as that which gives reality and objectivity to the thing known and which Kant regarded as due to mind. Form as conceptualized in post-Renaissance aesthetics is always aligned with the shaping powers of the mind, those of the artist as well as the viewer. Shaftesbury, in considering form, asked: What is it you admire but mind, or the effect of mind? It is mind alone which forms. In Kant, form cannot be based on either the material or conceptual structure of the aesthetic object. Instead, as Samuel Weber has suggested, form in Kant amounts to something like a silhouette, that is, the minimal trait required to individualize a perception and to distinguish it from its surroundings. Form becomes something like a unified temporal and spatial moment distinguishing shape from shapeless elements. For the purposes of this essay, form should be considered as bearing a double-fold valence, empirical and metaphysical. Empirically, form is realized as style, the shaping of figures, the line or touch of Beardsley’s drawings, the punctuation and syntax that Joyce employed so deliberately. Metaphysically, form is realized as an effect of mind that can be realized as having some reference outside oneself. The metaphysical manifestation of form should be conceived as responsible, in part, for the distancing effect of the aesthetic, that which marks fixity from movement or dislocation, the individual from the mass, uniqueness from multiplicity. The assertion of form, the effects of mind, holds off a collapse into the pornographic.

Photo: Galina Nelyubova, Unsplash

In the 1890s, British artists took their lead from the French Art-for-Art’s Sake movement (which in turn had followed Kant), and in addition to repeating Gautier’s rallying cry for aesthetic autonomy, followed his practice of asserting a beautiful form upon a subject seemingly inharmonious. Perfection of form was in itself seen as an aesthetic virtue. Subjects that heretofore had remained outside of art were allowed into art under the pretense that a beautiful form purified an ugly, sinful, or sensuous content. Thus in Arthur Symons’s elegiac commentary on Beardsley’s work he noted that the spiritual corruption represented in Beardsley’s work is revealed in beautiful form and that beauty transfigures the evil depicted.1 Similarly, Osbert Burdett remarked that in an age when beauty had been pushed to its extreme, Beardsley took this degradation for his subject and proved how beautifully degradation itself could be depicted. While neither commentator was comfortable embracing the decadent, sinful subjects of Beardsley’s works, they both were quite ready to qualify the treatment as artistic, beautiful.

1 – Arthur Symons, Aubrey Beardsley (London: J. M. Dent & Co., 1905) 37

Portrait de Théophile Gautier, 1858 | Théophile Gauthier, Panthéon charivarique, 1870

Treatment became the defining narrative of Beardsley’s work according to the critics of the early twentieth century. The importance of Beardsley’s works was not in the represented, but rather the representing—his transfiguring touch. Focusing on form, critics maintained a pretense to disinterest, and thus perpetuated the high-cultural vantage point begun in the late eighteenth century with the division of high and low arts by intrinsic or instrumental value. By foregrounding their own form, Beardsley’s works, portraying images that in another context would clearly be considered pornographic, deny, in Peter Michelson’s words ‘the necessary connection between pornography and vulgarity, or immorality and ugliness.’1 Drawing on the empirical resonance of form to reconfigure the pornographic into the aesthetic, Beardsley relied on a vast technical vocabulary to assert classical lines against sexually moved subjects. Joyce also adopted this technique. As Stephen Dedalus says in Stephen Hero, ‘A classical style is the symbolism of art, the only legitimate process from one world to another.’ Beardsley’s elegant and controlling line was the key to his aesthetic reception and perpetuation by the high-culture institutions that value autonomy, control, and disinterest as conveyed through form.

1 – Peter Michelson, ‘Beardsley, Burroughs, decadence and the poetics of obscenity,’ Tri Quarterly, no. 12 (spring 1968) 140

Aubrey Beardsley, 1890 | Photo: Frederick Hollyer

The aesthetic criteria by which Joyce’s works were judged were similar to Beardsley’s. T. S. Eliot’s classic 1923 essay ‘Ulysses, Order and Myth’ privileged formal considerations over those of content by imposing the ‘mythical method’ onto Joyce’s novel. In Eliot’s conception the myth itself serves as the ordering principle by which Ulysses is given form. Eliot argued that manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity is simply a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history. The keywords in Eliot’s analysis, ‘manipulating:’ ‘ordering,’ and ‘controlling:’ joined later by a compliment to Joyce’s formal ‘discipline,’ each suggest a politicized mode of dealing with the ‘anarchy’ of modern culture. To Eliot, aesthetic technique effects a social and physical ordering, and that ordering is intentionally imposed. The mythical method serves as a signifier of artistic intention not just through the imposition of form, but also through its drawing upon that proprietary reserve of high culture: classical literature.

T.S. Eliot, 1926 (Photo: Henry Ware Eliot) | James Joyce, 1935 (Photo: Boris Lipnitzki)

The emphasis on formal concerns arose and was perpetuated by middle-class anxiety about the increased access to art and literature enjoyed by the working classes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The boom of print journalism in the 1890s, which catered largely to the newly educated working classes and the petit bourgeois, created alarm in the high-cultural sphere about the spread of certain forms of literacy that it troped in images of contagion. Words in the mass-cultural sphere became ‘promiscuous’ words. The printed word, Osbert Burdett commented in 1925, is beginning to lose all distinction in newspapers and books that do no more than reflect the illiteracy of the mass of readers. ‘Words,’ as Stephen remarks in Stephen Hero (mimicking the high-cultural viewpoint, as he does so often in regard to aesthetic taste), ‘have a certain value in the literary tradition and a certain value in the marketplace—a debased value’ (SH 33). Words are debased because they take on meanings beyond the pure sphere of the literary; they are contaminated by meanings imposed by the crowd, by interest, personal and financial.

New York City subway, 1946-47 | Photo: Stanley Kubrick, Look Magazine

The debased value of art in the commercial, public sphere catalyzed artists, beginning with the artists of the 1890s, to discover more abstruse ways of expressing their art. Burdett claimed that the ‘extravagance’ of artistic assertion in the 1890s was a protest against a commercial society, in which the pressure of numbers had become so great that the needs and standard of the multitude necessarily dominated everything. John Rothenstein, a contemporary of Burdett’s who also wrote on the artists of the 1890s, argued that machinery [and its attendant commercialism] destroyed within the space of a few years the instinctive good taste of the people of England. Artists such as Aubrey Beardsley, he contended, were forced to create a fantastic and exotic refuge from the present. There was a defensive, high-cultural consensus around the turn of the century that ‘true’ art was a project set in opposition to mass culture and mass-cultural forms. Given modernism’s purported high-cultural bias against mass culture, it is interesting to note how frequently mass-cultural forms made their way into art that aspired to high-cultural status. The emergence of a mass market for cultural commodities created by the expanding wealth and literacy of the lower classes freed artists at the same time that it constrained them. For while, on the one hand, increasing numbers of the working and lower middle classes beginning to purchase art and literature expanded the market, on the other hand, the proliferation of literary products tended to erode a cultural consensus that had for most of the nineteenth century been based on shared upper-middle-class patterns of consumption. Artists were forced to find new means of expression that, while acknowledging and often exploiting this new market, continued to play upon the traditional signifiers of high art in order to perpetuate their place within high culture, to maintain an artistic aristocracy.

Photo: Vishwanth Pindiboina, Unsplash

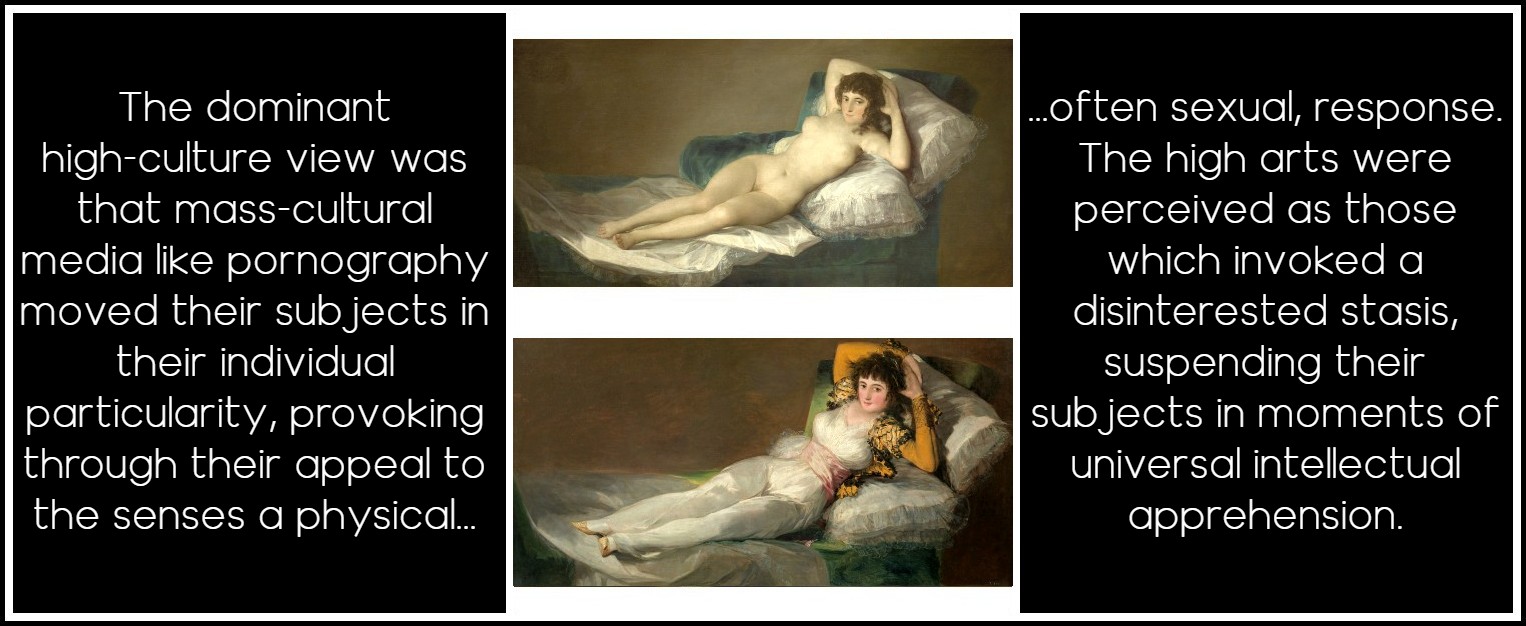

Inheriting the prevalent tenets of aesthetic philosophy developed in the tradition of Shaftesbury and Kant, the dominant high-culture view was that low-and mass-cultural media, like pornography, moved their subjects in their individual particularity, provoking through their appeal to the senses a physical, often sexual, response. The high arts were perceived as those which invoked a disinterested stasis, suspending their subjects in moments of (the idea of) universal intellectual apprehension. A stunning recapitulation of these values can be found in the oft-cited scene in Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in which Stephen Dedalus distinguishes between the kinetic emotions, those excited by what he calls the improper arts—pornographic or didactic—and the aesthetic emotions, those characterized by stasis and elicited from art proper. High art, as the domain of a certain segment of the middle class, was predicated on a censorship of the body as self-constituting subject. While art appreciation is a subject-centering activity, in Kantian and post-Kantian aesthetic philosophy it is based on the removal or suppression of the body from the aesthetic interaction in place of the more outwardly, community oriented understanding, or reason. Francis Barker, writing about the bourgeois disavowal of the material body, suggests that in post-Renaissance middle-class discourses, the body and its passions are at work in and around the portions of discourse in which the subject is present to itself, but only as the effects of a guilty evasion, a turning aside uttered by the subject but in an important sense unknown to it.1 The body was other to the bourgeois subject.2

1 – Francis Barker, The Private Tremulous Body: Essays on Subjection (New York: Methuen, 1984) 64

2 – Barker’s view may seem to be at odds with Foucault’s well-known theory expressed in The History of Sexuality, vol. 1 that the middle-classes were in fact talking quite constantly about their sexuality in the nineteenth century through a proliferation of discourses, medical and otherwise. However, these discourses can be seen to be consistent with Barker’s point in that they address one’s sexuality indirectly, substituting themselves for more direct attempts to realize the body. They are, like the Kantian aesthetic, distancing, rational accounts of the irrational body.

Goya, La maja desnuda; La maja vestida, c. 1800

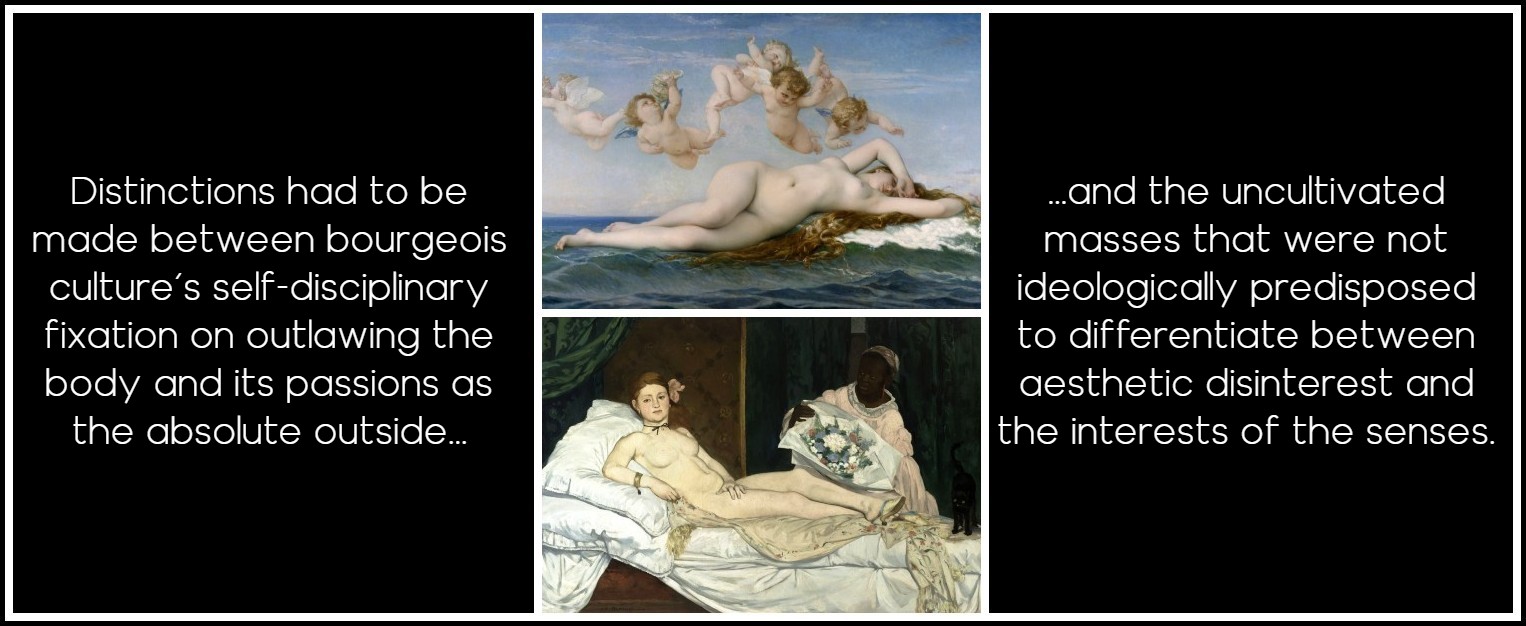

If the body was other, increasingly distinctions had to be made between the bourgeois culture that operated under a self-disciplinary fixation predicated on the outlawing of the body and its passions as the absolute outside, and the uncultivated masses that were not ideologically predisposed to differentiate between aesthetic disinterest and the interests of the senses. Adorno has classified this latter group as those that exhibit, an animal-like attitude toward the object, say, a desire to devour it or otherwise subjugate it to one’s body.1 The middle classes associated the working classes with disease, consumption, the bestial, the feminine, and the uncivilized. To the middle classes the working classes represented the body, and as such were outside the culturally hegemonic bourgeois realm (while simultaneously functioning as a necessary other, as necessary as one’s own body). In his 1896 work The Crowd, Gustave Le Bon inscribed the masses in a narrative of degeneration, assessing them as belonging to inferior forms of evolution, women, savages, and children, for instance. Le Bon’s work is a testament to the fact that by the end of the nineteenth century, the working classes were formed symbolically into a new, externalized and abstract phenomenon enabled by the rapid production of mass media forms: the mass or crowd. The crowd was seen as impetuous, physically oriented, and mentally inferior.2 Beyond any realistic conception, it should be clear, the mass was a construct of haut bourgeois self-assertion, a perpetual metaphor of an other that enabled self definition. The symbolic constituents of the abstract mass did not adhere to actual individuals, but functioned as an imaginary category for organizing class relationships.

1 – T.W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. C. Lenhardt (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul) 16

2 – Le Bon’s work is based on a late nineteenth-century psychiatric distinction between an unconscious level of emotion, reflex and automatism, and consciousness as associated with reason and conscious memory. Consciousness was, in Le Bon’s view, a relatively recent development. The state of being in the crowd was therefore identical to being unconscious, a state in which individuality is absorbed into the crowd or the mass.

Alexandre Cabanel, The Birth of Venus, 1863 | Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863

[The Birth of Venus, clothed in myth, was acclaimed at the Paris Salon | Olympia, naked in reality, was disdained.] RJ

The symbolic construction of the mass represented a distinctly separate construction of the citizenry than the eighteenth-century conception of the public sphere. The public sphere, developed after the Glorious Revolution when the powers of parliament began to supersede those of the monarchy, implied active, rational participation in government. The mass, or crowd, implied a separation between rational government and the body of the people. The public sphere of middle-class citizens that engendered high culture in the eighteenth century was predicated on a denial of the body. Inheriting those biases two hundred years later, the mass was all body. If high-culture art appreciation rested on a denial of an interest of the senses, the masses were seen as subjugating art to their bodies in a mode of conspicuous consumption antithetical to the repressed pleasures of disinterested contemplation. Though a difference between modes of aesthetic consumption marked the occasion of the philosophies of taste and the aesthetic in England and Germany in the eighteenth century, the early twentieth century observed a more complete rupture between high and low modes of consumption. Importantly, the Oxford English Dictionary first published a distinction between literature and popular literature in 1904, associating the popular with mass-cultural modes of consumption. While the low, or popular, arts were allied with profits and ‘interest,’ the high arts were associated with disinterest, symbolic capital over economic capital. With its priority on profit, consumption, and sensual enjoyment, mass culture was demonized by the defenders of high culture.

Photo: Roberta Sant-Anna, Unsplash | Text on image: RJ

Walter Benjamin outlines this distinction in his essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,’ where he sets up a paradigm of high and low modes of consumption. He describes phenomena much like those I have been describing as distance and immediacy as ‘distraction’ and ‘concentration.’ Distraction and concentration, he says, form polar opposites which may be stated as follows: A man who concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it. He enters into this work of art. In contrast, the distracted mass absorbs the work of art. As in the Kantian model, the aesthetic experience is authenticated by an attitude that disavows consumption in commercial or appetitive terms, aiming instead to remove the subject from himself and from an economy of endless personal interests. Aesthetic form is that which accommodates, perhaps even forces, distance. The desire of the contemporary masses, Benjamin writes, is to bring things ‘closer’ spatially and humanly, which is just as ardent as their bent toward overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by accepting its reproduction. The bent towards bringing things closer is explained by Adorno in Aesthetic Theory in his claim that as art became more and more similar to physical subjectivity, it moved more and more away from objectivity, ingratiating itself with the public. That mass (re)production has facilitated the perception of a universal equality of things is to Benjamin simply the result of the adjustment of reality to the masses and the masses to reality.

Walter Benjamin, Berlin, 1929 | Photo: Charlotte Joël

Both Benjamin and Adorno indicate that changes in the social structure and the accessibility of the arts in the early decades of the twentieth century fundamentally challenged the ideal of an achieved objectivity in aesthetic contemplation/consumption. Before there was mass-cultural consumption, Benjamin proposes, art was characterized by its ‘aura,’ which he defines loosely as the unique phenomenon of a distance however close an object may be. While temporally Benjamin places the art of aura as having preceded the art of exhibition (of which mass-reproduced works form a part), I would argue that the notion of art as defined by a distance, or in associative Kantian terms, disinterest, arose and was further concretized in direct response to the perceived threat of marginalization by the arts of interest, the commercial arts. Pornography, sexual literature written for profit with the specific purpose of identifying with and/or creating a physical subjectivity and a bodily reading/consumption, is the antithesis of the art of aura, for distance is anathema to a bodily reading. Reaching its zenith in an age of mass reproduction, pornography, especially in its visual forms, represents mass-culture and its physical repudiation of distance (even if its solipsistic pleasures are enabled by that very distance).

Theodor Adorno, 1963 | Photo: Stefan Moses, Munich City Museum

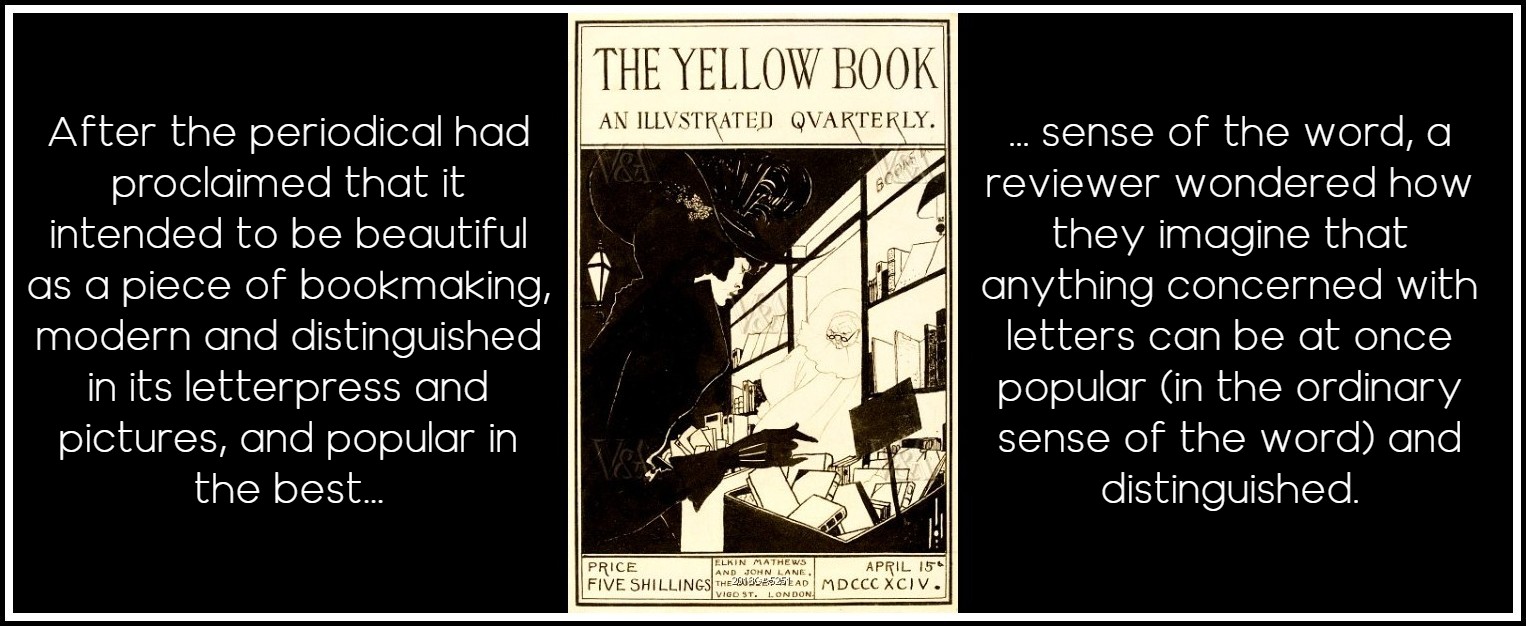

Verbal distinctions between mass and high culture resonated throughout the reviews of Aubrey Beardsley’s art and James Joyce’s literature, and while they had their high-cultural defenders, their introduction of pornographic representational techniques exposed them to the critics of mass culture. When the Yellow Book first hit the stands, there was a critical outcry over its affront to tradition. After the periodical had proclaimed that it intended to be beautiful as a piece of bookmaking, modern and distinguished in its letterpress and pictures, and popular in the best sense of the word, a reviewer for The National Observer wondered how they imagine that anything concerned with letters can be at once popular (in the ordinary sense of the word) and distinguished. The reviewer then mockingly identified the Yellow Book’s readership as the petit bourgeois, a new readership whose patterns of consumption were supposedly but an imitation of the more studied ones of the reviewer’s ilk: Now we have it: you can see men going home from their labour in the city, bearing the work deferentially in their arms: it flames from the forehead of many an ‘occasional table’ in Brixton and Bayswater. For the great world likes to be told what it is to admire, especially when it is to admire something new. It stands to reason that a quarterly, which boasted its intention of throwing aside the ‘traditions of periodical literature’ as ‘old’ and ‘bad’ was assured of a welcome from the obedient suburban populace, which since it cannot be the apostle of The Newness is content to be its acolyte.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Yellow Book, 1894

More explicitly, the Pall Mall Gazette belittled the Yellow Book’s constituency: The lower middle class is in the movement. Highbury and Brixton are arrayed in yellow, and Mr. Aubrey Beardsley is already the patron-saint of the back parlour. The gleeful disdain with which each reviewer comments on the interior decor of the petit bourgeois home, its ‘occasional table’ and ‘back parlour,’ reveals a contempt for lower-middle-class assimilation (and perceived imitation) of upper-middle-class patterns of consumption, aesthetic or decorative. That the lower middle class would proudly display Beardsley’s works on their tables or in their parlors is an indication of a conspicuous consumption (equivalent to Leopold Bloom hanging the picture of the nymph from Photo-Bits in his bedroom) that exposes their pretension to class and their ‘false’ aesthetic consciousness. The Yellow Book in Bayswater and Brixton can be nothing but kitsch.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Yellow Book, April 1894

Just as popularity was perceived as a fault with Beardsley’s periodical, the association with the populace was likewise a burden to Ulysses. The most often cited critique of Joyce’s work when it first appeared in 1922 was its similarity in appearance to a telephone directory. The reviewer for The Sporting Times declared: As the volume is about the size of the London Directory, I do not envy anyone who reads it for pleasure. The Daily Herald noted that the book was as large as a telephone directory or a family Bible, and with many of the literary and social characteristics of each. Shane Leslie of the Quarterly Review worried that Ulysses, resembling in size and colour the London Telephone Book, was a danger to the unsuspecting. Surely its resemblance in the minds of its reviewers to a telephone book reflects nothing so much as their fear that such a ‘dangerous work’ might create a ‘direct-dial’ connection with the masses, who in turn might read a sexually explicit work like Ulysses with their bodies rather than employ the cultivated stance of intellectual distance. Equally dangerous, a telephone book is read only for certain passages, those items one ‘looks up’; in Ulysses’ case, its sex scenes. That those under-educated in the techniques of cultured reading might have access to Ulysses was a fear repeatedly recognized in the reviews. A reviewer for the European edition of the Chicago Tribune worried: What it will mean to the reader is a question. Too many are the possibilities of this human flesh when finally in contact with the crude, disgusting and unpalatable facts of our short existence. One thing to be thankful for is that the volume is in a limited edition, therefore suppressed to the stenographer or high school boy.

James Joyce, Ulysses, first edition Paris 1922 | London Telephone Directory, 1923

The Dublin Review was relieved: As for the general reader, it is, as it were, so much rotten caviare [a high-cultural signifier if ever there was one, though in this case working to suggest the degenerate], and the public is in no particular danger of understanding or being corrupted thereby. Thus extracted, these reviews all share an abhorrence of the general, the popular, and the new class of clerks and typists that emerged with their small disposable incomes after late-nineteenth-century educational reforms took hold. Where the works of Beardsley or Joyce seemed to cater to the mass’s sensuous tastes through sexualized representations, the middle-class defenders of high culture trembled. Yet where the works provided difficulty, reserve, or elegance of form—all signifiers of a higher aesthetic that enforces distance—the reviewers delighted. Despite the tenuous reception of Joyce and Beardsley’s works by solid middle-class reviewers and their significantly documented battles with censorship, one needs hardly to be reminded that, especially in Joyce’s case, the works were almost instantly canonized. Their canonization was dependent on their ability to assert a high-cultural aesthetic, even while appropriating—even flaunting—the pornographic. By discursively controlling the potentially revolutionary material(ism) of the masses, and by checking a sensuous reaction to their works through a disjunctive style that disrupts the normative flow of a pornographic pleasure, Joyce and Beardsley effectively rendered the sensuous and low in their works impotent while maintaining the hegemony of form, the high-art signifier of culture. To be sure, the pornographic in these works asserts its immediacy and constantly threatens to destabilize the aesthetic. But by prioritizing form in its empirical and metaphysical manifestations, these works foster the disinterestedness that is the supposed guarantee of the aesthetic quality of contemplation.

James Joyce, 1927 (Photo: Berenice Abbott) | Aubrey Beardsley, 1894 (Photo: Frederick Evans)

One manifestation of the form by which Joyce and Beardsley gain aesthetic distance from the pornographic tropes they use is through employing parody or ironic distance. The pragmatic function of irony, as Linda Hutcheon has noted, is to signal evaluation, a critical distance.1 The deployment of the pornographic in Beardsley and Joyce is almost always accompanied by an ironic distancing that focuses not on the sexual representation itself, but on how that representation is mediated and received. This technique serves to set the text itself apart from the representations of the pornographic in order to signal a critical distance from them by repeating and reproducing them in a sociologically incongruent context. This has the effect of rendering the pornographic representations incongruous or even absurd, simply by making them perceptible as arbitrary conventions.2 Once recognized as a system of tropes, pornographic images lose their performative effect.

1 – Linda Hutcheon, A Theory of Parody (New York: Methuen, 1985) 53

2 – See Pierre Bourdieu ‘The Field of Cultural Production,’ The Field of Cultural Production (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993) 31

Buckley’s Slot-Machine Parlor, Las Vegas, 1953 Calendar | Photo of Marilyn Monroe: Tom Kelley, 1949

If a reader is not complicitous with the parodic attitude, unable to understand the tropes as deconstructed, such technique may work against the agent of parody, for parody equally highlights its own artifices in such a way that the parodic text becomes a site of contestation, despite the mutually constitutive nature of such parody. It may seem the intention of the parodic text to control and indicate a difference from the parodied text, but a failure to appeal to an audience through a normative system of recognizable codes or ‘ideolects’ through which one can ridicule marginalized languages or styles may result in what Frederic Jameson has described as pastiche: Pastiche is, like parody, the imitation of a peculiar or unique style, the wearing of a stylistic mask, speech in a dead language. But it is a neutral practice of such mimicry, without parody’s ulterior motive, without satirical impulse, without laughter, without that still latent feeling that there exists something normal compared to which what is being imitated is rather comic. Pastiche is blank parody.1 Parody, then, is a local and temporal phenomenon. It can only exist for a specific group of people within a specific time frame, after which it fades, like all cultural memories, into mere pastiche.

1 – Frederic Jameson, ‘Postmodernism and Consumer Society,’ The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1983) 114

Hal Foster, editor, The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture | Frederic Jameson (Photo: Marit Hommedal)

The question remains whether what Joyce or Beardsley did with the pornographic in their texts should be read in the modernist way as parodic, or in the postmodernist way as pastiche. Surely one can rigorously read their works both ways. But an investigation into the marriage of the pornographic and the aesthetic in high art at the turn of the twentieth century needs to be mindful of the audiences to whom these works were aimed and the critics who guided these audiences into modes of reception, for the works’ contemporary critics were the ones who, as the reviews above make clear, would have harbored a keener sensitivity to the pornographic as antithetical to the aesthetic. Representing the represented, the parodic text must perform the cultural labor of transformation. As readings of their works will show, Beardsley and Joyce assumed this labor.

James Joyce, 1937 (Photo: Josef Breitenbach) | Aubrey Beardsley, 1894 (Photo: Frederick Evans)

Though Joyce and Beardsley incorporated seemingly subversive tropes, Bakhtin’s theory of the carnival helps to remind us of the nature of parodic inversion. In transgressing norms, the very norms that are transgressed are also posited in their notable absence.1 Parody’s transgressions are ultimately authorized by the norms it seeks to subvert. A high-art work that incorporates the pornographic transgresses high-art norms, but in doing so it foregrounds the very norms violated. In this sense, as Barthes has pointed out, parody can suggest complicity with high culture, which is merely a deceptively off-hand way of showing a profound respect for classical-national values.2 However, because parody is a dialogue between two texts, as this essay will show, it can cut both ways, each text deconstructing the conventions of the other. The pornographic tropes and images incorporated often work to subvert their high-cultural context. A parody of pornography, Susan Sontag has written, so far as it has any real competence, always remains pornography.3 But in Joyce and Beardsley, the parodying of pornographic texts functions primarily as a conservative and appropriating force for high art. Though foregrounding the constructedness of both pornography and aesthetics, Joyce and Beardsley’s works relied on a complicity with their audiences to recognize the ironic distance from the pornographic tropes employed as subversive of both pornography and aesthetics, but formally in compliance with the aesthetic in the tradition of Shaftesbury and Kant. By resignifying and recontextualizing pornography, Joyce and Beardsley are frequently successful at limiting and dominating it. They appropriated pornography for high art, making sexual representation safe for the middle classes.

1 – Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and his World, trans. Helene Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984) 1-59

2 – Roland Barthes, Critical Essays, trans. Richard Miller (New York: Hill & Wang, 1972) 119

3 – Susan Sontag, ‘The Pornographic Imagination,’ Styles of Radical Will (New York: Doubleday, 1969) 51

Aubrey Beardsley, 1893 (Photo: Frederick Evans) | James Joyce, late 1920s (Photo: Berenice Abbot)

ALLISON PEASE: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments