DJUNA BARNES

Ladies Almanack

SUSAN LANSER ON DJUNA BARNES – LADIES ALMANACK

Speaking in Tongues: ‘Ladies Almanack’ and the Discourse of Desire

Susan Lanser is Professor Emerita of English, Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies, and Comparative Literature at Brandies University

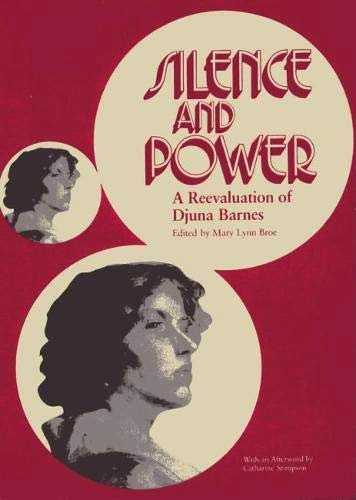

Excerpts from Susan Lanser’s chapter in Mary Lynn Broe, ed., Silence and Power: A Reevaluation of Djuna Barnes (Southern Illinois University Press, 1991)

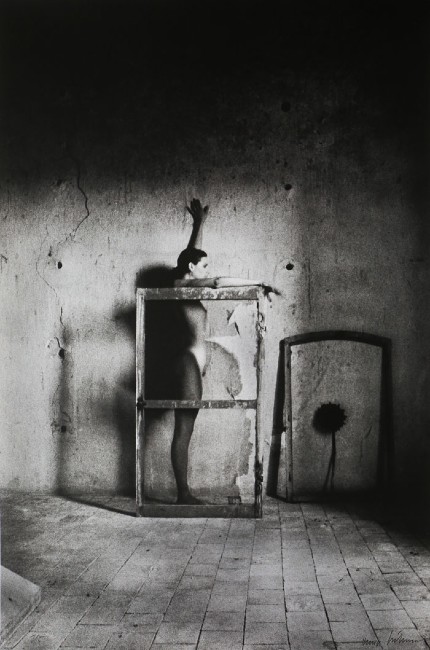

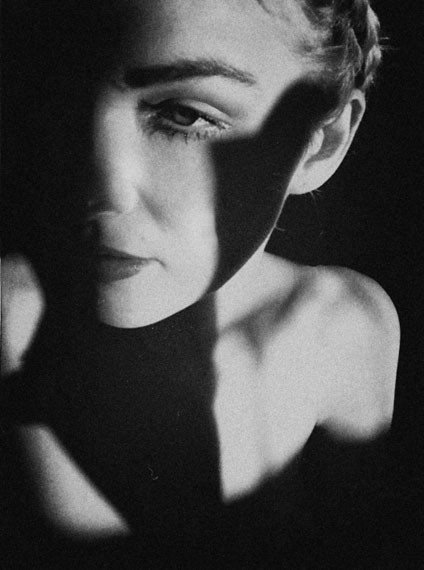

ALL PHOTOGRAPHS BY KARIN SZÉKESSY

© Karin Székessy | 1-8 Courtesy Galerie 36 | 9-17 Courtesy Johanna Breede Photokunst

Its author calls it a ‘slight satiric wigging’ (even as she sets it next to Proust); its 1972 publishers claim she regarded it as ‘a simple piece of fun, in no way to be considered among her serious works.’ Its original, anonymous, and private publication, though in a foreign tongue, was so threatening that its distributor withdrew and the book was sold by its author’s friends on Paris streets. It has confounded critics, intimidated readers, enticed feminists, outraged conservatives, and delighted for decades the people it parodies. But mostly it has been unnoticed and unread: only now is Ladies Almanack beginning to assume a place of distinction in the complicated corpus of Djuna Barnes and the differently complicated intertext of lesbian literature. In both canons, Ladies Almanack stands apart, posing a challenge to questions of writing, reading, and authorship.

Karin Székessy, One Sits, One Jumps, 1969

The discourse of Ladies Almanack is a dense and highly allusive prose through which almost nothing is made clear; the text speaks cryptically, figurally, and evasively. Sentences are winding, inverted, unfinished or impossibly long. Antecedents get misplaced, verbs dangle, pronouns lose their source. Key words are sometimes elided from sentences whose meanings remain forever indeterminate, as in ‘I came to it as other Women, and I never a Woman before nor since’. Archaisms are common—some as old as Chaucer, some barely obsolete; neologisms are frequent; grammatical forms are resurrected from the Renaissance or invented on the spot. There is a continual mingling of registers as well as lexicons: plain modern English coexists with fancy Elizabethan; obscure terms are juxtaposed with blunt Anglo-Saxon unpleasantries. Metaphors often make one strain desperately and still end up not quite making sense: ‘the anomaly … that, affronted, eats its shadow’; ‘she thaws nothing but Facts’; ‘Outrunners in the Thickets of prehistoric probability’; ‘two Creatures sitting in Skull’ are frustratingly typical. And enshrouding the whole are the Capital Letters: most nouns and a few adjectives and verbs are capitalized, so that the text seems at once Ancient and Fantastical.

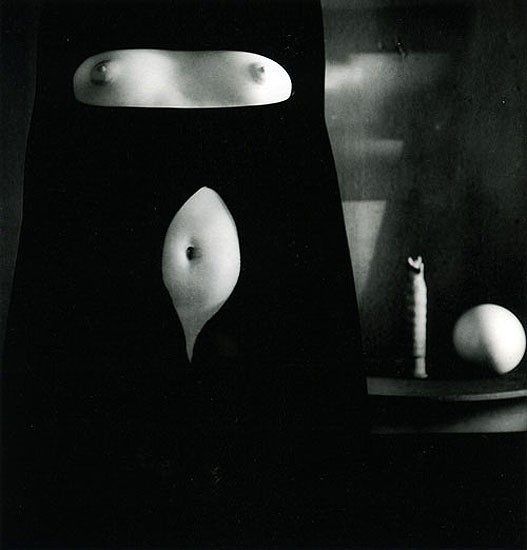

Karin Székessy, Palm Fan, 2001

The perspective and tone of Ladies Almanack are sometimes equally indeterminate, clouded by indirect discourse, rhetorical questions, oxymorons, and maxims of uncertain intent. Lesbian sexuality is called a ‘Distemper’ and a ‘Beatitude’ in the same paragraph; women who love women are like ‘a tree cut of life’ yet they make ‘a Garden of Ecstasy’; ‘Love in Man is Fear of Fear,’ but ‘Love in Woman is Hope without Hope’. These contradictory and coded messages generate a narrative voice that is evasive, devious, playfully indirect. There are moments when the narrator does say or imply ‘I’ and ‘we,’ but never in a context that commits her to a single, coherent textual identity. The result is ‘a Maze, nor will we have a way out of it’: a text that speaks in tongues.

Karin Székessy, Simone Framed, 1999

At least three different modes of discourse combine to create this maze. First and most prominent are the narrative segments that tell the story of Dame Musset and her coterie of allegorically named characters (each with a historical counterpart). These narrative passages are the most ribald sections of the book and the most accessible. A second set of sequences fashions a fanciful Amazonian lore, using song and poetry, illustration and myth, to turn patriarchal discourse to gynocentric ends, as if anticipating Monique Wittig’s call to women in Les guérillères to ‘remember, or failing that, invent.’

Karin Székessy, Staircase (Homage to Marcel Duchamp), 2015

The third and least common mode of discourse in Ladies Almanack is expository, pondering questions of a social and philosophical sort; perhaps because these passages cannot rely on fictional visions, they are the most ambiguous and ambivalent segments of the text, yielding much of its contradiction and its few moments of gloom. These three kinds of discourse are usually interwoven and interspersed rather than sequential and discrete: a myth about woman’s Edenic origins slides into the story line as Eve becomes Daisy Downpour; Dame Musset’s friends take on the philosopher’s role and shift narrative to essay-in-dialogue; a single page juxtaposes poem and picaresque. Though each chapter is named for a month of the year and is headed by apt illustration, the segments vary in length, mode, and formal composition: some tell the story of Dame Musset; others are essays; several are composites of poetry, story, and inquiry.

Karin Székessy, With Mask and Cactus, 1979

This mélange of modes and media permits an exploration of lesbian culture and female experience from multiple points of view, each form or voice carrying another shade of difference, another piece of the prism that constitutes the book’s elusive rhetorical stance. The interweaving of philosophic, mythic, and narrative modes, each with its particular tendencies of mood, creates a sense of motion in the text: not a beeline or a circle, but an uneven, irregular expedition, now meandering, now dashing, now turning back, like one of Dame Musset’s romps through the Bois. Like all almanacs, this one allows time to be both cyclic and linear. (It is no accident that Barnes used the almanac form on several occasions: given her preoccupation with time, the almanac may have afforded her a way to mark its passage without despair.) As it progresses the text becomes at once more radical and more covert, until clarity is restored as narrative turns mythic in a climactic account of Dame Musset’s death.

Karin Székessy, For Werner Kunze, 1969

Barnes herself was demonstrably ambivalent about both the book and the personal questions it raised. Although fame and fortune (understandably) preoccupied her rather strongly in her later years, and although Ladies Almanack had been unavailable since its initial private printing of 1,050 copies, Barnes was reluctant to reissue it and did not include it in the 1962. edition of her Selected Works. Natalie Barney and others in the group urged her repeatedly to reprint it. ‘Why not let that side of us appear in your complete works?’ Barney wrote to her in 1963; ‘Why not open the eyes of ‘Seuil’ [French publishers of Nightwood] to this masterpiece?’ she asked again in 1968. Barnes’ responses are always ambivalent, claiming that Ladies Almanack was a work ‘of another kind,’ one meant for ‘the private domaine [sic], … written as a jollity and distributed to a very special audience,’ though she promised it would be included in any ‘collection of the entire corpus’ that might appear. She also feared charges of ‘salacious[ness]’ even as she demurred that Ladies Almanack was ‘much too mild’ for ‘present taste.’ It was probably with complex emotions, then, that Barnes gave reprint rights to Harper and Row in 1972, allegedly fearing the kind of literary piracy that had already occurred with The Book of Repulsive Women.

Karin Székessy, Lying over a Chair, 1984

Barnes’ ‘codedness’ about Ladies Almanack mirrors, of course, the codedness within the text itself. There are political explanations for both Barnes’ own reticence and the ambiguous discourse and perspective of Ladies Almanack, beyond the particular resonance of modernist discourse and the Barney circle’s delight in innuendo and obscurity, beyond the fact too that Ladies Almanack was first a private document that probably embeds a host of private references. Barnes did not reveal her personal life to her reading public and was displeased at the claims on her identity made by lesbian historiographers. Literary biography—that dangerous, irresistible game—does tell us that Barnes had relationships with both women and men, and that probably the major love of her life was Thelma Wood, with whom she was stormily involved for the decade surrounding the writing of Ladies Almanack. Her biographer Andrew Field considers her ‘basically heterosexual,’ accepting all too readily, I think, Barnes’ own reported comment, ‘I’m not a lesbian; I just loved Thelma.’

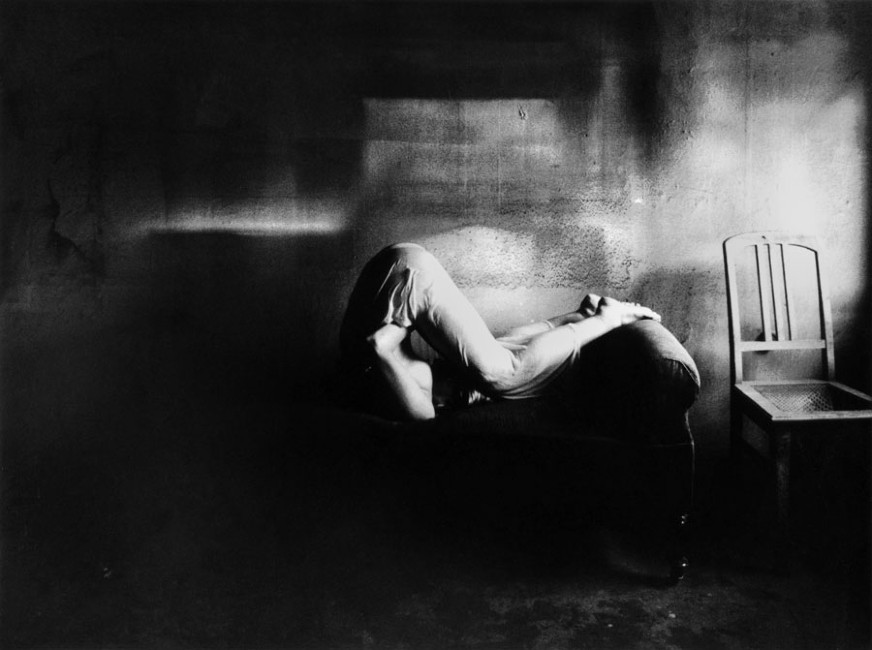

Karin Székessy, Jutta on the Sofa, 1967

For Thelma Wood was not the only woman with whom Djuna Barnes was involved; she had a profound and possibly sexual relationship with Mary Pyne, and at least a brief affair with Natalie Barney. Indeed, it is possible to read Ladies Almanack itself as a love letter to Natalie: the February section calls itself a ‘Love Letter for a Present,’ and claims that its author has nothing original except her words to give the legendary lover Dame Musset; if she cannot ‘make a New Path where there be no Wilderness,’ then ‘Fancy’ will be her ‘only craft’. Barnes’ ambivalence about declaring her sexuality may have played a role in the elision, from various collections of her short works, of texts with lesbian implications such as ‘Dove,’ ‘Khalidine,’ and ‘Paprika Johnson.’ It may also be significant that while Barnes usually identifies those to whom she dedicates her work (her mother, Peggy Guggenheim, and Mary Pyne, for example), in the dedication to Ryder Thelma Wood is discreetly coded as ‘T.W.’

Karin Székessy, Leo, Pascale and Sandrine, 1985

Barnes’ reticence is a ‘problem’ only because so many critics seem reluctant even to contemplate a lesbian-centered reading of Ladies Almanack without a definitive ‘corroboration’ from Barnes’ own life. The shape of critical controversy over the perspective of Ladies Almanack suggests the degree to which literary criticism can bathe itself in both biography and intentionality, especially when a discourse is ambiguous or politically sensitive. For whatever Barnes’ own attitudes, and however elusive and shifting the narrative perspective of this book, the rhetorical stance of Ladies Almanack is an inside stance. The charged word ‘lesbian’ is mentioned only once in the entire text—a significant sign of self-censorship—but its context, interestingly, is a reference to the ‘Lesbian Eye,’ which suggests a lesbian point of view and, homonymically, the affirmations ‘I’ and ‘aye.’ Were there no information whatever to suggest a biography of lesbian experience, the textual perspective would remain.

Karin Székessy, Shadow Hand, 2000

There is another important reason for the ambiguity and codedness of Ladies Almanack: the constraints on sexual discourse, especially by and about women, still prevailing in 1928. A journalist, Barnes must have understood that lesbian material, as the book itself puts it, ‘could be printed nowhere and in no Country, for Life is represented in no City by a Journal dedicated to the Undercurrents, or for that matter to any real Fact whatsoever’. Better to shroud the Undercurrents in obscurity, generating a prose whose meanings dissolve beneath a torrent of difficult words and sentences. The political implications of Barnes’ discourse would surely ‘loom the bigger if stripped of its Jangle, but no, drugged such it must go. As foggy as a Mere, as drenched as a Pump; twittering so loud upon the wire that one cannot hear the message. And yet!’. The ‘Jangle’—a common strategy in the artistic performances of women and other outsiders—protects the discourse from those whose understanding would be dangerous, while providing a signal to those whose understanding the writer seeks. Without Barnes’ ‘Jangle,’ even private publication in a foreign land might have been impossible; after all, the much more accessible and far more decorous Well of Loneliness was subjected to legal censorship in just that year.

Karin Székessy, Two Cut-Outs, 1970

Indeed, it is especially illuminating to see the Almanack against this more conventional and chaste counterpart, for together these texts—respectively the most infamous and most obscure lesbian writings of 1928 —frame the borders of the textually possible in their moment of history. Hall’s novel offers a clear, carefully plotted psychological narrative in the (conservative, for 1928) nineteenth-century realist mode. Although the plot engages the reader in a mimesis of lesbian life, the story is otherwise a conventional Bildungsroman with a tragic denouement. Radclyffe Hall understood The Well of Loneliness to be a compromise; she consciously cramped her politics inside the conventions of the realistic novel and the Victorian mind in order to reach a wide audience of heterosexual, middle-class intellectuals, with the express purpose of portraying lesbian existence and identity in a voice that would plead for ‘tolerance.’

Karin Székessy, Madame Récamier, 1975

A passionate plea and a cry of rage, audacious enough in theme, The Well of Loneliness could not afford to dare in structure, language, or tone. Ladies Almanack, in contrast, takes lesbian existence almost for granted, eschews realism and even readability, and seeks to ‘reach’ only the already converted audience of Barnes’ own friends. Its purpose is not to plead but to delight. In Ladies Almanack there is no question of a tragic denouement, because there is neither a plot nor an audience that would demand or even tolerate it. Yet only in privacy could Ladies Almanack exist in 1928. (One can measure the distance lesbian discourse has traveled simply by noting Harper and Row’s decision to publish Ladies Almanack in 1972, a decision that as far as I know was not a controversial one.) What Ladies Almanack may finally tell us, then, is the degree to which reading and even writing becomes a function of the reader’s desires, and the degree to which desire, in turn, creates both the frustrations and the pleasures of the text. In this context it is worth remembering that Ladies Almanack was written for an audience both lesbian and modernist, and that it presupposes a specific world view.

Karin Székessy, Lita (for MKW), 2008

Read inside its author’s own intertext, Ladies Almanack also becomes a commentary on the Barnesian corpus, that body of darkness upon which the two 1928 parodies, Ryder and Ladies Almanack, dance a light and often playful melody. In a language as ribald as Ryder’s, Ladies Almanack counters Ryder’s heterosexual mythology—with Dame Musset the lesbian counterpart to Wendell Ryder—even as it amplifies the feminist elements already present in Ryder. Like The Book of Repulsive Women before it, which opens with a blatantly sexual lesbian poem, Ladies Almanack dares a discourse of desire; like Nightwood after it, Ladies Almanack creates a problematics of that desire.

Karin Székessy, Cotta by the Window, 2013

But by the time of Nightwood, where hope has died not only politically with the imminence of fascist plague but personally for Barnes in the final rupture with her own Nightwood, love has lost its enchantment if not its force, and sexuality has become more bondage than bond. The 1928 books offer one moment in Barnes’ work in which the troublesome questions of gender, love, and sex converge with at least the hope of happiness. Perhaps Ladies Almanack and Ryder are parodic works because they mock not only a particular literary tradition, but the inward and tormented tendencies of Barnes’ own consciousness.

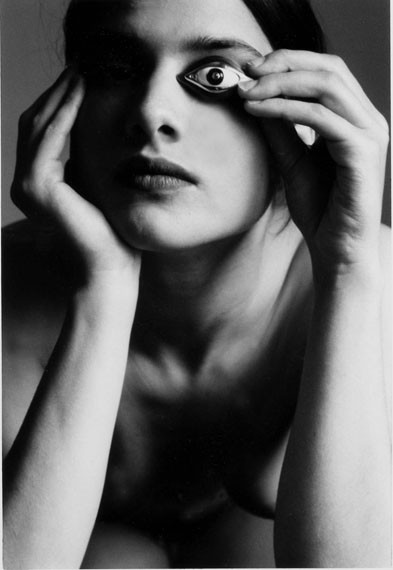

Karin Székessy, The Eye (for P.W), 2000

For Ladies Almanack is finally an extraordinary text in the Barnesian chronicle (as in all its canons—lesbian, female, modernist), sharing theme and form with other works, yet far more radical in its politics, far more gynocentric in its consciousness. As such, Ladies Almanack suggests the power of a moment—of an intersection of cultural circumstances—virtually to overpower personal ‘identity’ in shaping the voice and vision of a text. There is finally no authorization from Barnes herself—from her public statements, her private correspondence or her published works—for the radical implications of Ladies Almanack, no moment in Barnesian discourse that matches the vision of this text. And had Djuna Barnes been presented with the political implications of her work as I have drawn them here, she might well have disavowed them entirely.

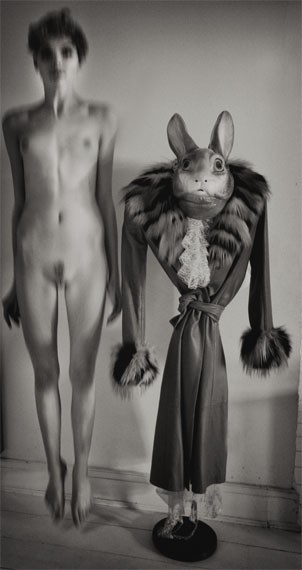

Karin Székessy, Hare and Model, 2014

Barnes may finally, then, have been articulating a universe less of her own desire than of the desires of those who were at once her friends, readers, and characters. Such a concept challenges notions of the unitary writing subject and traditional images of the nature of writing in relationship to authorial identity. We may then have to account for the radical vision of Ladies Almanack in the euphoria and daring of a cultural moment of which Barnes found herself the articulating voice. And if context is able so profoundly to shape discourse, virtually to generate its vision, then the notion of ‘author’ becomes inconceivable or irrelevant apart from ‘text.’ The problem lies, then, not in attempting to reconcile the historical Barnes with the textual voice of Ladies Almanack but in having thought the two equivalent. It is within the freedom of this more complex vision of reading and writing, of Ladies Almanack and Djuna Barnes, that one may discover the pleasures and perils of speaking in tongues.

Karin Székessy, Shadow and Light, undated

SUSAN LANSER: TWO BOOKS & A BOOK CHAPTER

DJUNA BARNES IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 15

Or the two of you, in black capes and manly hats (a nod to Djuna Barnes and Thelma Wood), walking hand-in-hand down the boulevard.

William Rothenstein, Two Women, 1895

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 14

̶ My loss, Marietta, my loss. But I’ll get over it! I’m working on a new project.

̶ Great. What is it?

̶ I’ve been commissioned to design a perfume bottle.

̶ Congratulations!

̶ It’s for Leonora. They’re launching a new scent, Demoiselle de la nuit.

̶ What’s it like?

̶ Wonderfully perverse! A mixture of masculine and feminine, woody patchouli and white floral, with blackcurrant, lime, and a touch of liquorice. And—here’s the real kicker—something overripe and perfectly louche!

̶ I like it! And the bottle, will it be louche too?

̶ Louche, no. Erotic, yes!

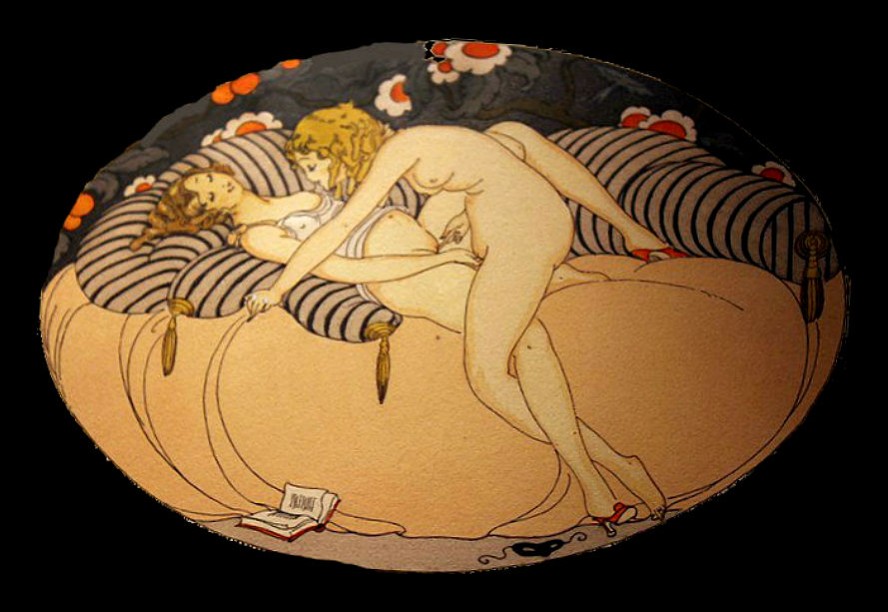

Gerda Wegener, The Circle of Love, 1917

Your eyes sparkle.

̶ Tell me more!

̶ I first toyed with the idea of a bottle that goes against the scent. You know, something for prim girls in glasses.

̶ Who go wild at night?

̶ Exactly!

̶ Like Riva! Héloïse jumps in.

Riva whirls her head wildly, then pulls a prim, perfectly straight face. Everybody laughs.

̶ As it turned out, Marketing didn’t like that idea. Then I took the opposite tack—baroque and humorous, in the spirit of Ladies Almanack.

Djuna Barnes—the slow narcotic of Nightwood, the anatomy of love: through a black diamond, lucidly.

̶ You know, tipping the velvet, tongue in cheek.

The joyful wit of her Vanity Fair portrait, white wine with Joyce at the Deux Magots.

̶ In a word, louche, but ironic.

Gerda Wegener, The Connoisseurs, 1917

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A novel by Richard Jonathan

DJUNA BARNES, ‘LADIES ALMANACK’: PROLOGUE

From Djuna Barnes, Ladies Almanack (First published privately in Paris, 1928)

Now this be a Tale of as fine a Wench as ever wet Bed, she who was called Evangeline Musset and who was in her Heart one Grand Red Cross for the Pursuance, the Relief and the Distraction, of such Girls as in their Hinder Parts, and their Fore Parts, and in whatsoever Parts did suffer them most, lament Cruelly, be it Itch of Palm, or Quarters most horribly burning, which do oft occur in the Spring of the Year, or at those Times when they do sit upon warm and cozy Material, such as Fur, or thick and Oriental Rugs, (whose very Design it seems, procures for them such a Languishing of the Haunch and Reins as is insupportable) or who sit upon warm Stoves, whence it is known that one such flew up with an “Ah my God ! What a World it is for a Girl indeed, be she ever so well abridged and cool of Mind and preserved of Intention, the Instincts are, nevertheless, brought to such a yelping Pitch and so undo her, that she runs hither and thither seeking some Simple or Unguent which shall allay her Pain! And why is it no Philosopher of whatever Sort, has discovered, amid the nice Herbage of his Garden, one that will content that Part, but that from the day that we were indifferent Matter, to this wherein we are Imperial Personages of the divine human Race, no thing so solaces it as other Parts as inflamed, or with the Consolation every Woman has at her Finger Tips, or at the very Hang of her Tongue?”

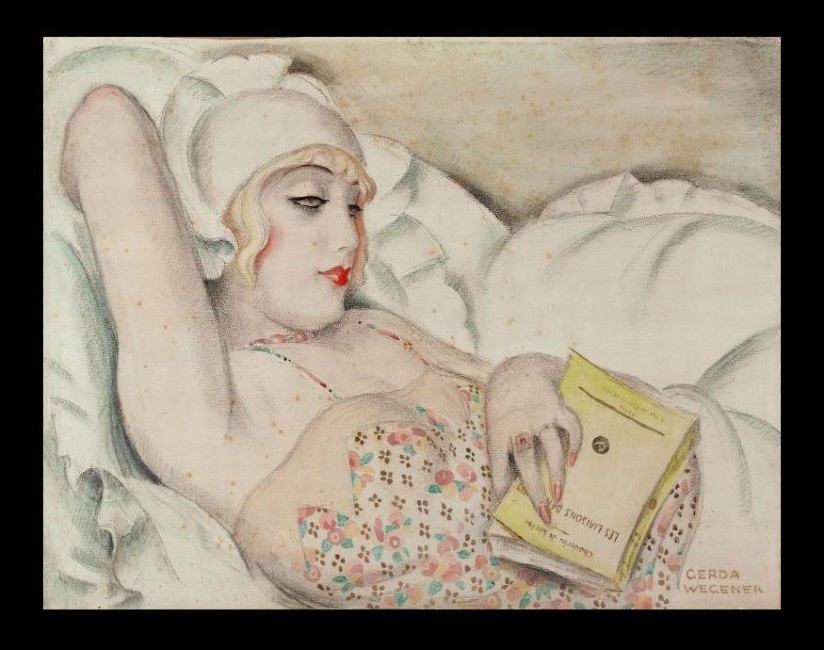

Gerda Wegener

For such then was Evangeline Musset created, a Dame of lofty Lineage, who, in the early eighties, had discarded her family Tandem, in which her Mother and Father found Pleasure enough, for the distorted Amusement of riding all smack-of-astride, like any Yeoman going to gather in his Crops; and with much jolting and galloping, was made, hour by hour, less womanly, “Though never”, said she, “has that Greek Mystery occurred to me, which is known as the Dashing out of the Testicles, and all that goes with it!” Which is said to have happened to a Byzantine Baggage of the Trojan Period, more to her Surprise than her Pleasure. Yet it is an agreeable Circumstance that the Ages thought fit to hand down this Miracle, for Hope springs eternal in the human Breast.

Gerda Wegener

It has been noted by some and several, that Women have in them the Pip of Romanticism so well grown and fat of Sensibility, that they, upon reaching an uncertain Age, discard Duster, Offspring and Spouse, and a little after are seen leaning, all of a limp, on a Pillar of Bathos. Evangeline Musset was not one of these, for she had been developed in the Womb of her most gentle Mother to be a Boy, when therefore, she came forth an Inch or so less than this, she paid no Heed to the Error, but donning a Vest of a superb Blister and Tooling, a Belcher for tippet and a pair of hip-boots with a scarlet channel (for it was a most wet wading) she took her Whip in hand, calling her Pups about her, and so set out upon the Road of Destiny, until such time as they should grow to be Hounds of a Blood, and Pointers with a certainty in the Butt of their Tails ; waiting patiently beneath Cypresses for this Purpose, and under the Boughs of the aloe tree, composing, as she did so, Madrigals to all sweet and ramping things.

Gerda Wegener

Her Father, be it known, spent many a windy Eve pacing his Library in the most normal of Night-Shirts, trying to think of ways to bring his erring Child back into that Religion and Activity which has ever been thought sufficient for a Woman ; for already, when Evangeline appeared at Tea to the Duchess Clitoressa of Natescourt, women in the way (the Bourgeoise be it noted, on an errand to some nice Church of the Catholic Order, with their Babes at Breast, and Husbands at Arm) would snatch their Skirts from Contamination, putting such wincing Terror into their Dears with their quick and trembling Plucking, that it had been observed, in due time, by all Society, and Evangeline was in order of becoming one of those who is spoken to out of Generosity, which her Father could see, would by no Road, lead her to the Altar. He had Words with her enough, saying : “Daughter, daughter, I perceive in you most fatherly Sentiments. What am I to do ?” And she answered him High enough, “Thou, good Governor, wast expecting a Son when you lay atop of your Choosing, why then be so mortal wounded when you perceive that you have your Wish? Am I not doing after your very Desire, and is it not the more commendable, seeing that I do it without the Tools for the Trade, and yet nothing complain?”

Gerda Wegener, La Sieste, 1922

In the days of which I write she had come to be a witty and learned Fifty, and though most short of Stature and nothing handsome, was so much in Demand, and so wide famed for her Genius at bringing up by Hand, and so noted and esteemed for her Slips of the Tongue that it finally brought her into the Hall of Fame, where she stood by a Statue of Venus as calm as you please, or leaned upon a lachrymal Urn with a small Sponge for such as Wept in her own Time and stood in Need of it.

Gerda Wegener

Thus begins this Almanack, which all Ladies

should carry about with them, as the Priest his

Breviary, as the Cook his Recipes,

as the Doctor his Physic, as

the Bride her Fears,

and as the Lion

his Roar!

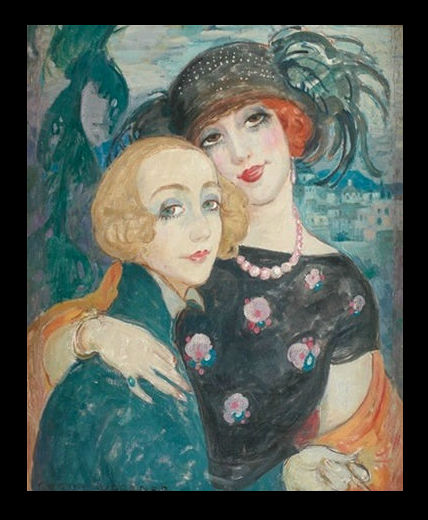

Gerda Wegener, Les deux amies de Capri, 1921

DJUNA BARNES, ‘NIGHTWOOD’: OPENING

From Djuna Barnes, Nightwood (First published in London by Faber and Faber, 1936)

BOW DOWN

Early in 1880, in spite of a well-founded suspicion as to the advisability of perpetuating that race which has the sanction of the Lord and the disapproval of the people, Hedvig Volkbein—a Viennese woman of great strength and military beauty, lying upon a canopied bed of a rich spectacular crimson, the valance stamped with the bifurcated wings of the House of Hapsburg, the feather coverlet an envelope of satin on which, in massive and tarnished gold threads, stood the Volkbein arms—gave birth, at the age of forty-five, to an only child, a son, seven days after her physician predicted that she would be taken.

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait of Mrs Boucard, 1931

Turning upon this field, which shook to the clatter of morning horses in the street beyond, with the gross splendour of a general saluting the flag, she named him Felix, thrust him from her, and died. The child’s father had gone six months previously, a victim of fever. Guido Volkbein, a Jew of Italian descent, had been both a gourmet and a dandy, never appearing in public without the ribbon of some quite unknown distinction tinging his buttonhole with a faint thread. He had been small, rotund, and haughtily timid, his stomach protruding slightly in an upward jutting slope that brought into prominence the buttons of his waistcoat and trousers, marking the exact centre of his body with the obstetric line seen on fruits—the inevitable arc produced by heavy rounds of burgundy, schlagsahne, and beer.

George Grosz, Der Spiessbürger, 1928

DJUNA BARNES: FOUR EXCERPTS FROM LETTERS, FOUR PHOTOS

All excerpts from letters are from Mary Lynn Broe, ed., Silence and Power: A Reevaluation of Djuna Barnes (Southern Illinois University Press, 1991)

We have known, for some time now, that we are the vestiges of an ancient and lost line, tho the youth of today, I’m told, find the ‘twenties’ utterly fascinating— and the days pull out and go off to somewhere I have no interest in… The time of the twenties and thirties seems the property of someone else, to be observed, in the mind, with Greta Garbo’s murmur, when sitting through Camille, or Anna, etc. ‘Watch, see her now, she is going to—’ When you look up, you are sitting in your particular house number— No one can stand it, that’s certain… but one can parry, parry, or try to foil… or draw a measure—

Djuna Barnes, letter to Peter Hoare, 19 September 1964 (first part) & 5 January 1974 (second part). [Broe, p. 337 and p. 339]

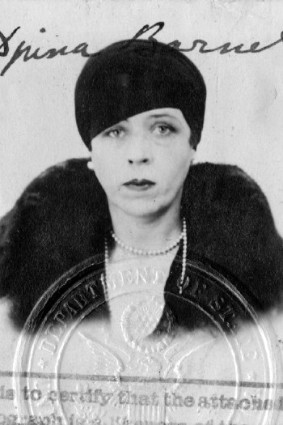

Djuna Barnes in Paris, 1921-22

Courtesy University of Maryland Digital Collections

What is my dear Paris like now? People tell me it is the same, but it can’t be — nothing is the same — they are used to it — probably I would be as shocked as any friend who comes upon a friend too suddenly. Is Natalie still about — and all of as old as God? Looking back in this day is very precarious position — what a world we have of it now — alreading computing carefare [sic] to Mars — or for you, Hesperus — the morning star! — the ancient amenities out the window, and sins more bloody awful, free and pointless. I’d give my teeth for a day or two back in time, in Paris, at a sidewalk bistro (there’s a words got away!) for the purpose of correcting, no reinforcing, the apprehensions of memory — as say Proust. All my public is talking Royal Jelly… I did not write letters anymore myself, but writing to you is like that Proustian madeleine — and that uneven courtyard stone that set him pitching headfirst into his past. I hope you are not too somber, that you have some of your former hilarious sorrow…

Djuna Barnes, letter to Dan Mahoney, 14 November 1958 [Broe, p. 155]

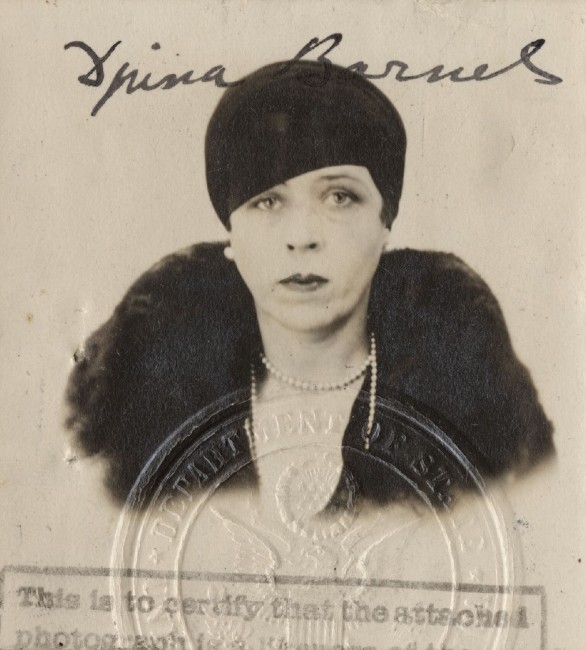

Djuna Barnes, passport photo, 1929

Courtesy University of Maryland Digital Collections

How does one arrange for life… how do writers keep on writing? Professional ones do, I don’t see how my kind can—the “passion spent”, and even the fury—the passion made into Nightwood, the fury (nearly) exhausted in The Antiphon… what is left? “The horror,” as Conrad put it.

Djuna Barnes, letter to Peter Hoare, 18 July 1963 [Broe, p. 337]

Thelma Wood & Djuna Barnes, Provincetown, 1925-26

Courtesy University of Maryland Digital Collections

‘No personal life, and now no home.’ I don’t know what to say, that is, what could be said to comfort you. What comfort is there for a person when they feel life falling away. Only the old advice, so old no one believes it, or believing partially still does not care about it, or feels it in applicable to his or her case etc, etc, as the King of Siam said. In the end, as far as I can see, there’s exactly nothing left for it but the mind and the spirit. Faith and books… one at least, two if possible… and a hobby. That you have, bookbinding. It’s at least merciful you have an income. What an aging woman does without that I’ll surely find out.

Djuna Barnes, letter to Mary Reynolds, 14 June 1949 [Broe, p. 155]

Djuna Barnes, 1957, aged 65

Courtesy University of Maryland Digital Collections