Part 2 of 4

JAMES JOYCE AND AUBREY BEARDSLEY: AESTHETICS OF OBSCENITY

Allison Pease

Posted by kind permission of Allison Pease, Professor of English, Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York.

From Allison Pease, Modernism, Mass Culture, and the Aesthetics of Obscenity (Cambridge University Press, 2000) pages 83-98

THIS IS PART 2 OF 4 PARTS. READ PART 1 FIRST.

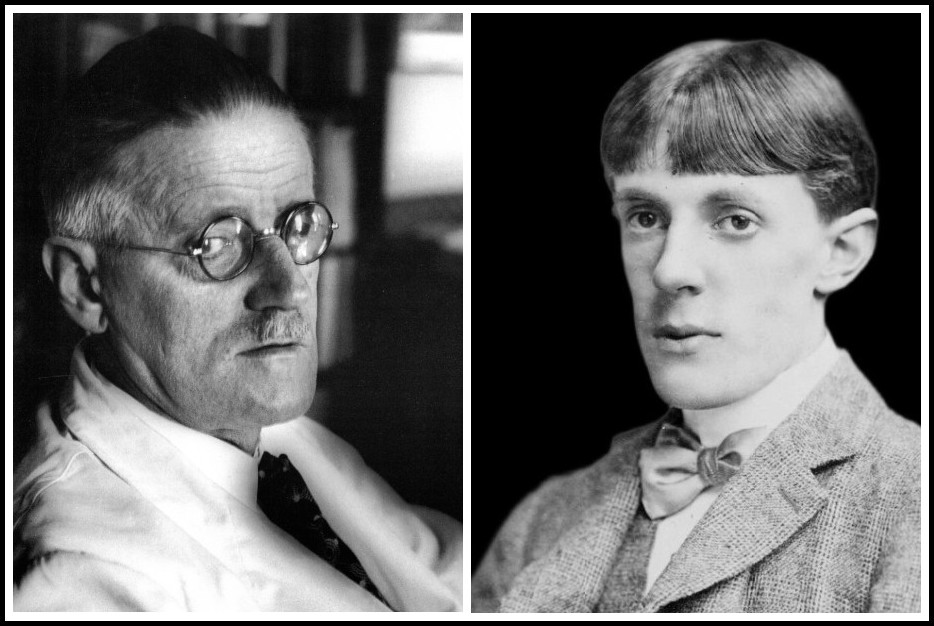

James Joyce, 1937 (Photo: Josef Breitenbach) | Aubrey Beardsley, 1890 (Photo: James Russell)

II. APPROPRIATIONS

Beardsley’s and Joyce’s interest in and familiarity with a variety of pornography has been well documented by numerous scholars. Both artists incorporated pornographic images and narratives in their works in such a way that allowed them to use, control, and limit the literature of and for the body to maintain high-art hegemony. While it should be clarified that such manipulations cannot be said to have been conscious decisions on the part of Beardsley or Joyce, who frequently demonstrated the will pour épater le bourgeois, such a power was effected through them by the very techniques they articulated. As Laura Kipnis suggests, a class becomes hegemonic not through its capacity for sheer domination, but through its ability to appropriate visions of the world and diverse cultural elements of its subordinated classes, but in forms that carefully neutralize any inherent or potential antagonism and transform these antagonisms into simple difference.1 The appropriation of the pornographic into high art resulted in neutralizing the potentially subversive effects of the increasing demand for underground sexual literature and pictures (market share) while exposing and therefore perpetuating the haute bourgeoisie control over/denial of the body as self-constituting subject (symbolic capital). The discursive exposure of the body as controlled form in high art is but a continuation of its distancing and objectification.

1 – Laura Kipnis, Ecstasy Unlimited: On Sex, Capital, Gender, and Aesthetics (University of Minneapolis Press, 1993) 30

Photo (detail): Bettina Rheims

Modern art has been noted for its appropriating impulse, and Ulysses is its classic example. But Joyce’s acquisitiveness, like Beardsley’s, can never be solely one-sided. As much as the images and tropes of pornographic texts are subverted from their primary aims when displaced into these artists’ works, so they subvert their high-cultural surroundings, cutting at their contexts in often unforeseen irony. In the political analogy I have drawn throughout this work, the entrance of lower-class forms, or the body (politic), into high art enacts a social reintegration of representational types on the page. Put simply, mind meets body, whether this discourse is controlled by the high-cultural aesthetic techniques that deploy it, or if it indeed enacts a pluralist mode of representation. Regardless of the interpretations a late twentieth-century reader might put on these discursive appropriations, it is significant that these works were and have since been taken seriously as art (as opposed to pornography). As I will show below, their success is due to their treatment of such pornographic tropes.

Photo (detail): Bettina Rheims

III. THE VOYEUR

Visual consumption is pornography’s primary mode. It is not a passive act of watching, but rather a consumption, a taking in of an image for personal use, a subjection of the image to the body. All who enjoy visual pornography are, logically, voyeurs. Likewise, written pornography, which invariably contains scenes of voyeurism in order to mimic and incite the action intended for its readers, is a form of literature intended for the bodily consumer, one who will subject the written images to his or her body’s passions. Seen as such, pornography is an inversion of the anti-materialist high-culture norms of aesthetic reception. It epitomizes the commercial, as Jennifer Wicke has commented, by foregrounding the ease and rapidity of mass-cultural consumptive visual strategies that are appallingly emblematized by pornography itself, where the languor and voluptuousness of consumption in general gets raised to its apotheosis.1

1 – Jennifer Wicke, ‘Through a Gaze Darkly: Pornography’s Academic Market,’ Dirty Looks: Women, Pornography, Power, ed. Roma Gibson and Pamela Church Gibson (London: BFI, 1993) 67-68

Photo: Grove Press/Black Cat cover image (detail) of Alain Robbe-Grillet, The Voyeur, 1958

Developed in the last decades of the nineteenth century, erotic postcards and photographs served as a cheap mass medium for the transmittal of erotic fantasies. By 1899, over 14 million postcards had been produced and distributed in Great Britain alone. The erotic postcard, most typically featuring a nude or semi-nude woman gazing playfully at the camera or wistfully into the unknown (though the variety of poses is not limited and sometimes features a male partner), represents the organization into visibility of the sexual fantasy. Prepackaged into an inexpensive, mass-produced commodity, erotic postcards create the voyeur as much as they are created by voyeurs. That is, they teach a method of looking and reacting to their subjects by creating a set of expectations of what can be found and seen. They set into practice a technique of consumption that is simultaneously a sexual practice.

Photos: Anonymous. From 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839-1939 (Uwe Scheid Collection, Taschen)

Stephen Dedalus proves himself inculcated into the voyeuristic practice in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, where in thinking of his lust for Emma he is ashamed to recall the sootcoated packet of pictures which he had hidden in the flue of the fireplace and in the presence of whose shameless or bashful wantonness he lay for hours sinning in thought and deed. Trained by erotic pictures to engage the sexual imagination upon the visible image, Stephen translates this practice into everyday experience: He bore cynically with the shameful details of his secret riots in which he exulted to defile with patience whatever image had attracted his eyes. The practice of pornography teaches its subjects to desublimate the sensuous apprehension. In this instance, the practice of pornography teaches its subjects to desublimate the sensuous apprehension of the image to effect an immediacy. Living beings are turned into images, photographic or cinematic displays to set into motion the bodily reader, the voyeur.

Photos: Anonymous. From 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839-1939 (Uwe Scheid Collection, Taschen)

Leopold Bloom is likewise inculcated into the voyeur’s mentality. It is not, per se, by nature that he is sexually stimulated by watching Gerty MacDowell reveal herself on the beach, but rather he has been readied for this experience (and knows how to exploit it) by a deep familiarity with pornographic, voyeuristic practice. The voyeuristic practice in its most troped pornographic form surfaces in the ‘Circe’ episode where Blazes Boylan suggests to Bloom that he watch while Boylan and Molly have adulterous sex: You can apply your eye to the keyhole and play with yourself while I just go through her a few times. The keyhole/spyhole trope figures throughout pornography, a typical example being found in My Secret Life where Walter, having arranged with a prostitute to watch unseen while she engages with another man, gloats that through the slightly opened door, I heard every sigh and murmur, saw every thrust and heave, a delicious sight. I seemed to have almost had the pleasure of fucking her as I witnessed him.1 The voyeuristic practice is focused on a solipsistic engagement with the visual, a bodily incitation to reproduce the pleasure of the seen. In the self-reflexive moment of voyeuristic pleasure, Bloom clasps himself, according to the stage directions, and shouts, Show! Hide! Show! Plough her! More! Shoot!. In so doing, Bloom exhibits a keenly pornographic, voyeuristic sensibility.

1 – My Secret Life. In John Cleland’s Fanny Hill or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, a sexually uninitiated Fanny first discovers sexual intercourse by hiding in a closet where ‘seeing everything minutely, I could not myself be seen’. In Romance of Lust the protagonist and his wife visit a bawdy house in Paris where ‘through cleverly arranged peep-holes, any operation in the next room could be distinctly seen’.

Photos: Anonymous. From 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839-1939 (Uwe Scheid Collection, Taschen)

Bloom is, in fact, a high-cultural stereotype of the lower-class bodily reader/voyeur. Untrained in bourgeois sublimation, Bloom seeks to subjugate the majority of his experience to the interests of his senses. Whereas Stephen, displaying a more typically middle-class and Catholic sensibility, separates sexual experience, discursive, pictorial, or real, into a realm apart from the high-cultural sphere he seeks to identify with himself, Bloom makes no differentiation, no sublimation of his bodily interests. Where Stephen’s sexuality is constructed around shame at his sexual subjection, Bloom exhibits relatively little shame (the ‘Circe’ episode must be taken as an exhibition of an emotion quite different from Bloom’s conscious shame). Though he is sexually dysfunctional with his wife, Bloom has no difficulty identifying himself as a sexual subject, and thus is able to bring that with him to all of his interactions.

Milo O’Shea as Leopold Bloom & Maurice Roëves as Stephen Dedalus in Joseph Strick’s film of Ulysses (1967)

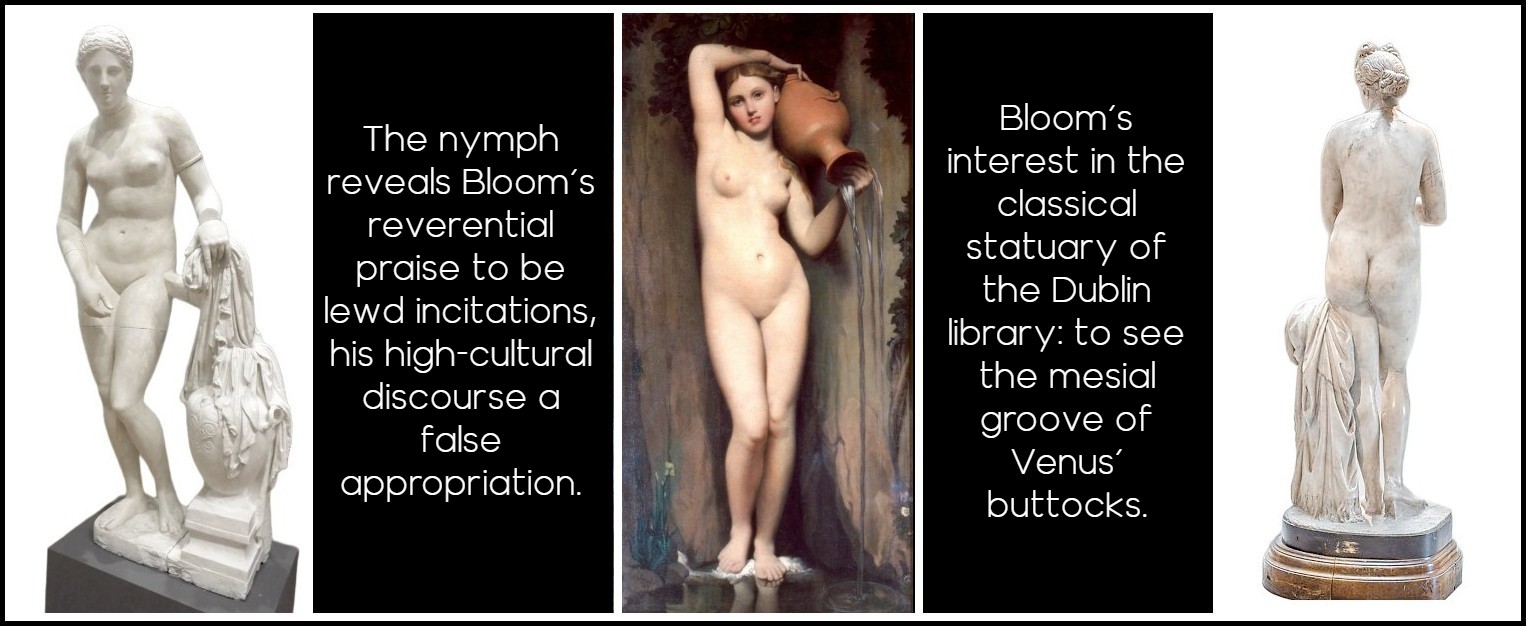

Bloom’s interest in the classical statuary of the Dublin library is, in contrast to its presumed high-cultural function as a symbol of metaphysical harmony, that he may see the mesial groove of the Venus of Praxiteles’s buttocks. He hangs the Bath of the Nymph over his bed in a gesture that, by displaying a mass-produced, pseudo-classical work in his home, demonstrates his complicity with lower-middle-class aspirations to imitate high-cultural patterns of consumption. While reverencing the splendid masterpiece in art colours as a signifier of a tradition he hasn’t the vocabulary to relate to, Greece: and for instance all the people that lived then, he relates to the work in the only way he knows how, with the pornographic, voyeuristic mentality. We learn in ‘Circe’ that Bloom has kissed the nymph of the poster in ‘four places,’ and that with ‘loving pencil’ has shaded her eyes, breasts, and pudendum. When accused of doing so by the nymph, Bloom ironically responds in high-cultural discourse. Your classic curves, beautiful immortal, he pleads, I was glad to look on you, to praise you, a thing of beauty, almost to pray. Yet the nymph reveals Bloom’s reverential ‘praise’ to be lewd incitations, his high-cultural discourse a false appropriation. In a lower-class subversion of high-cultural practices, the distinctions between high-art ‘aura’ and pornographic voyeurism are lost on Bloom. The nymph’s ritual value to Bloom is not in creating a metaphysical moment of universalized apprehension, but rather in experiencing a particular physical reaction to her visually organized eroticism.

Aphrodite of Knidos (1895 cast of Roman copy of Praxiteles’ 350 BCE Greek original) | Ingres, La Source, 1856

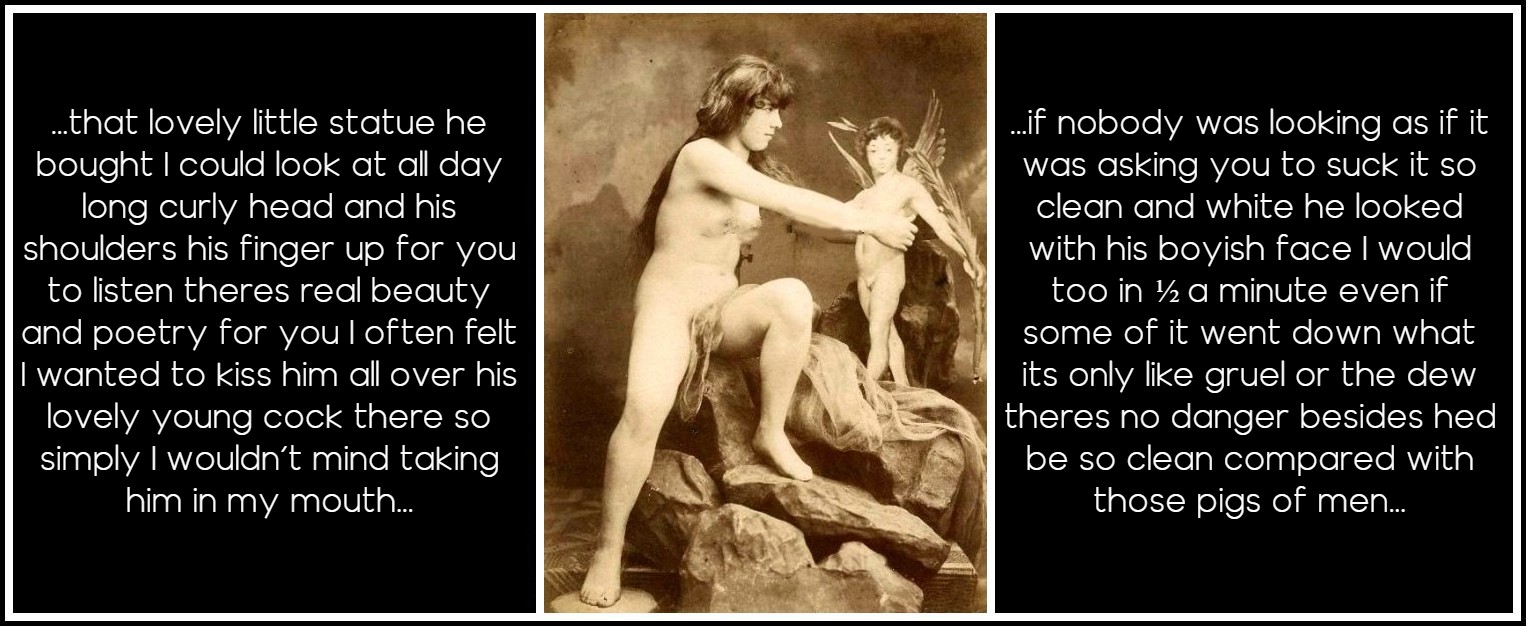

Again and again in Joyce one sees the conflation of the aesthetic and the pornographic, both in terms of the consumptive attitudes they are intended to provoke as well as the objects that manifest their supposedly different effects. Ulysses posits a series of sites of contestation between the two, a confrontation so aggressive that their dialectical relationship is both exposed and threatened. Molly Bloom’s response to her kitsch, classical statue of Narcissus (which Bloom bought and carried home in the rain for art for art’s sake, is even more heated than her husband’s to the classical nymph. Here Joyce is playing upon a pictorial tradition featuring women in sexual dalliance with classical cherubim. In one photograph taken around 1870, a woman attempts to pull a painted cherub closer to her, a gesture that plays out, in part, Molly’s explicitly sexual fantasy:1 that lovely little statue he bought I could look at all day long curly head and his shoulders his finger up for you to listen theres real beauty and poetry for you I often felt I wanted to kiss him all over his lovely young cock there so simply I wouldn’t mind taking him in my mouth if nobody was looking as if it was asking you to suck it so clean and white he looked with his boyish face I would too in ½ a minute even if some of it went down what its only like gruel or the dew theres no danger besides hed be so clean compared with those pigs of men.

1 – The pornography here may very well be playing on the Renaissance tradition of painting Eros and Aphrodite, and as such it underscores the mutually parodic, mutually constitutive, nature of both the aesthetic and the pornographic.

Photo: Gaudenzio Marconi, 1870

Such a scene, relayed in such sexually explicit language, was before 1922 unimaginable in writing with literary pretenses. One of the striking features of Molly’s soliloquy, however, that serves as a continual reminder of the force and presence of aesthetic form, is its absolute lack of punctuation. Performing a carnivalesque inversion, the passage relies on the very hegemonic form it denies. That is, its very formlessness is an assertion of aesthetic form (that simultaneously questions form itself), a perpetual reminder of the technical mastery controlling the desire on the page. The teleological pornographic narrative is here controlled by a syntactical confusion where modifiers subvert direct relationships. In grammatically mimicking the feature of pornographic novels whereby each protagonist ‘modifies’ or has a sexual relation to every other protagonist and no direct relationships are privileged, Joyce plays upon the very form he denies while demonstrating his formal mastery.

Aedin Moloney in Yes! Reflections of Molly Bloom, co-created by Aedin Moloney & Colum McCann | Photo: Carol Rosegg

A more condensed version of the same technique can be found at the end of ‘Nausicaa’ when Bloom enters upon a series of associations that function as sexually suggestive, but are nowhere pornographically representative. Recapping his masturbatory encounter with Gerty he thinks, O sweety all your little girlwhite up I saw dirty bracegirdle made me do love sticky we two naughty Grace darling she him past the bed met him pike hoses frillies for Raoul to perfume your wife black hair heave under embon señorita young eyes Mulvey plump years dreams return tail end Agendath swoony lovey showed ale her next year in drawers return next in her next her next. This excerpt serves as a perfect example of Joyce’s incorporation and defamiliarization of pornography. The quote is interlarded with references to the pornography Bloom himself has read or seen, ‘for Raoul,’ and ‘heave under embon’ being quotes from the pornographic novel Sweets of Sin Bloom has browsed for Molly earlier in the day, and señorita referring to the erotic photocard he owns of buccal coition between nude senorita (rear presentation, superior position) and nude torero (fore presentation, inferior position), itself a parody of the technical language that attempts to control the subversive content of the pornography within. Each word in the passage is pared to its metonymic function, suggesting the full pornographic fantasy while controlling that fantasy from taking over the narrative. There are no verbs to connect actions. There is no representative language to give the linear account that is pornography’s discursive form. In a masterly display of modernist abstraction, predicates are denied (fittingly enough) their copula, everything is modified by everything else but full meaning in terms of a continuous and explicit representation is denied. Joyce’s avant-garde, modernist form necessarily violates the pornographic forms used within, recoding such works for the high-brow reader.

Photo: Anonymous. From 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839-1939 (Uwe Scheid Collection, Taschen)

Molly’s perpetual drifting in and out of sexual narrative functions as a check to a possible bodily reading. The potential pornographic pleasure is always disrupted, held at bay by an intervening discourse. For example, when Molly is recalling her afternoon with Blazes Boylan, the sexual narrative is interrupted by a series of other related, but non-contributing, discourses. At length she says: then he goes and burns the bottom out of the pan all for his kidney this one not so much theres the mark of his teeth still where he tried to bite the nipple I had to scream out arent they fearful trying to hurt you I had a great breast of milk with Milly enough for two what was the reason of that he said I could have got a pound a week as a wet nurse all swelled out in the morning that delicate looking student that stopped in No 28 with the Citrons Penrose nearly caught me washing through the window only for I snapped up the towel to my face that was his studenting hurt me they used to weaning her till he got doctor Brady to give me the Belladonna prescription I had to get him to suck them they were so hard he said it was sweeter and thicker than cows then he wanted to milk me into the tea well hes beyond everything I declare somebody ought to put him in the budget if only I could remember the one half of the things and write a book out of it the works of Master Poldy yes and its so much smoother the skin much an hour he was at them Im sure by the clock like some kind of a big infant I had at me they want everything in their mouth all the pleasure those men get out of a woman I can feel his mouth O Lord I must stretch myself I wished he was here or somebody to let myself go with and come again like that I feel all fire inside me or if I could dream it when he made me spend the 2nd time tickling me behind with his fingers I was coming for about 5 minutes with my legs round him I had to hug him O Lord I wanted to shout out all sorts of things fuck or shit or anything at all only not to look ugly or those lines from the strain

Aedin Moloney in Yes! Reflections of Molly Bloom, co-created by Aedin Moloney & Colum McCann | Photo: Carol Rosegg

The pornographic in this text is imbricated within a larger network of discourses—medical, aesthetic, economic, mythological and culinary—each intervening upon the other. As Bakhtin has theorized, when heteroglossia, or diversified social discourses, exists within a novel, it constitutes what he calls a ‘double-voiced discourse.’ That is, at any given time a speaker may express the intentions of his or her language while simultaneously that language is being refracted through the authorial representation of that language. Incorporated forms are in Bakhtin’s words ‘indirect, conditional, distanced.’1 In the end, all the forms for dialogizing the transmission of another’s speech are directly subordinated to the task of artistically representing the speaker and his discourse as the image of a language, in which case the others’ words must undergo special artistic reformulation.2 By creating the image of a pornographic language (and, arguably, the image of all languages) Joyce emphasizes his formal stylization, the aestheticization that at all moments signifies his high-cultural aspirations. Form masters the language parodied therein in order to distance itself from the representation. It creates a distance from the reader by disavowing a complete pornographic pleasure in the narrative. Though gaining ground in terms of its public visibility, the sensuous content of Ulysses’ narrative is rendered impotent by form.

1 – M. M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination, trans. Caryl Emerson & Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 992) 323

2 – Ibid., 355

Photo: Alina Grubnyak, Unsplash

IV. THE CORRUPTED READER

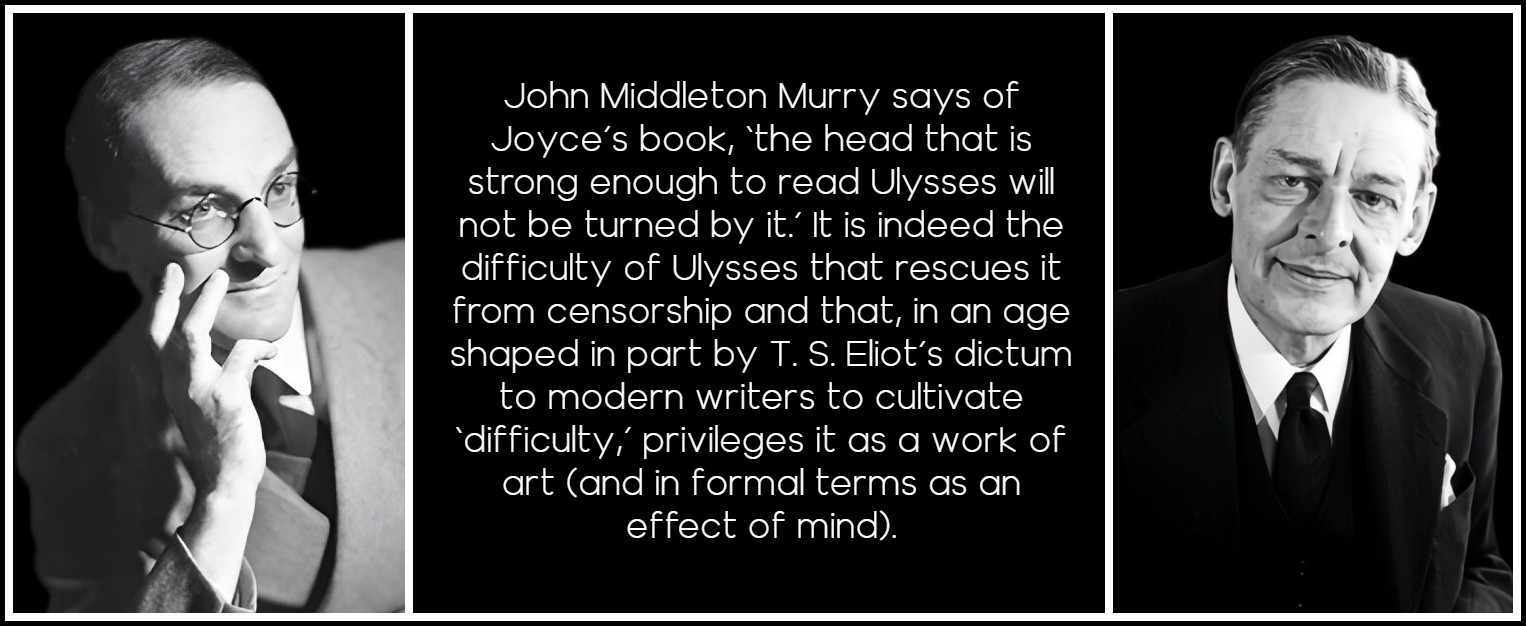

If images and statues offer themselves for voyeuristic consumption, books, especially in the fin-de-siècle, come equally in the eyes of hegemonic culture to represent a potential corruption. For, while in the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries the middle and upper classes continued to be trained in reading techniques that foregrounded an ideal disinterest, the large new reading population, including women and the working classes, was still being trained in a more rudimentary fashion that, in trying to prepare them for their stations in life, failed to pass on high-cultural ideals. Left to their own devices, it was believed, works of a questionable nature might ‘deprave and corrupt’ the working classes who, in the middle-class imagination, were likely to subject such works to an interest of the senses because of their own more base, sensuous constructions. Women of all classes were viewed as particularly susceptible to the influences of literature and the sway of their senses. As a majority of women in the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were new readers, and as they infrequently received the classical education rendered in public schools, they were just as liable as a working-class male to succumb to an interest of the senses. It is in this context that John Middleton Murry says of Joyce’s book, the head that is strong enough to read Ulysses will not be turned by it.1 It is indeed the difficulty of Ulysses that rescues it from censorship and that, in an age shaped in part by T. S. Eliot’s dictum to modern writers to cultivate ‘difficulty,’ privileges it as a work of art (and in formal terms as an effect of mind). For while Ulysses features, and in some ways celebrates, mass man in the form of Leopold Bloom, it is, as John Carey has suggested, also true that Bloom himself would never and could never have read Ulysses or a book like it.2

1 – John Middleton Murry, Nation and Athenaeum, 31 (April 22, 1922) 124-125

2 – John Carey, The Intellectuals and the Masses (Boston: Faber & Faber, 1992) 20

John Middleton Murry, 1934 (Photo: Howard Coster) | T.S. Eliot, 1929 (Photo: Lady Ottoline Morrell)

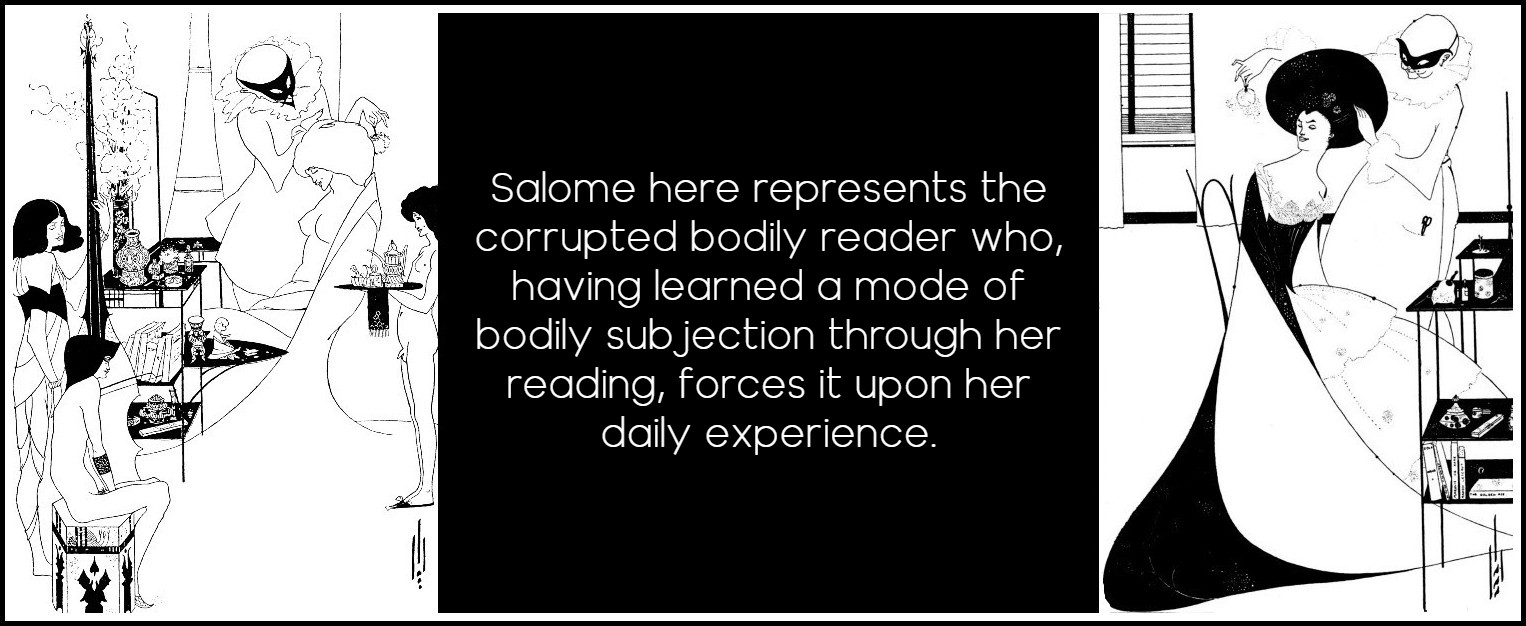

A drawing that reinforces the notion of the corrupted or corruptible reader is Beardsley’s The Toilette of Salome, second version. His initial drawing of Salome’s toilette having been rejected for its blatant display of masturbation, Beardsley was forced to try to convey the same ideas in a more conventionally acceptable manner. He chose to do so by providing Salome with a bookshelf filled with books that would have raised an eyebrow had they sat upon any middle-class woman’s shelf. Salome has been reading such works of decadence and overt sexuality as Nana, Zola’s story of a Parisian prostitute; Manon Lescaut, the story of another great courtesan by Abbé Prévost; the works of the Marquis de Sade; Verlaine’s Les Fêtes galantes; and Apuleius’ The Golden Ass. Rather than show his characters in the act of masturbating, Beardsley makes the more indirect suggestion that such works as lie on her shelf incite the voracious sensual appetite Salome displays later in the play. Salome here represents the corrupted bodily reader who, having learned a mode of bodily subjection through her reading, forces it upon her daily experience.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Toilette of Salome, versions 1 & 2, 1893-94

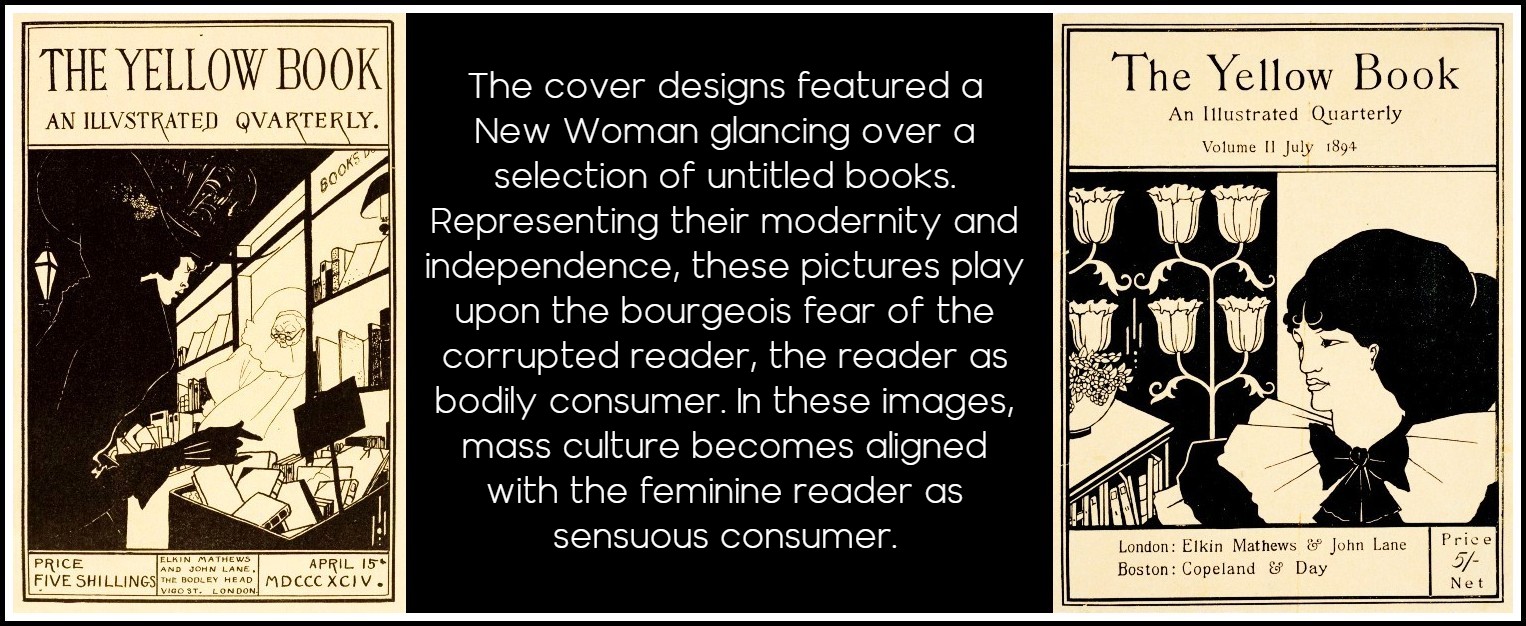

It is interesting that in this drawing Salome is featured in modern dress and fashion. As opposed to the rest of the Salome drawings where she is featured in exotic garb, here she resembles many of the ‘New Women’ Beardsley drew during his Yellow Book phase, women Holbrook Jackson once described as sardonic creatures who looked as if they were always hungering for the sensation after next.1 The association is important, for so many of the drawings that upset reviewers of the Yellow Book were not only evocative of the New Woman, but featured a New-Womanish figure looking at or choosing books. Contemporaneous reviewers frequently saw in the ‘Beardsley Woman’ disturbing signs of corruption, sexual deviance, and emancipation.2 The cover designs for the Yellow Book’s first and second volumes each featured a New Woman glancing over a selection of untitled books. Representing their modernity and independence, these pictures play upon the bourgeois fear of the corrupted reader, the reader as bodily consumer. In these images, mass culture becomes aligned with the feminine reader as sensuous consumer, ‘hungering for the sensation after next.’

1 – Holbrook Jackson, The Eighteen Nineties (1913; London: Jonathan Cape, 1931) 100

2 – Bridget Elliott, “New and Not So ‘New Women’ on the London Stage: Aubrey Beardsley’s Yellow Book Images of Mrs. Patrick Campbell and Rejane,” Victorian Studies, vol. 31, no. 1 (Autumn 1987) 33-34

Aubrey Beardsley, The Yellow Book, April & July 1894

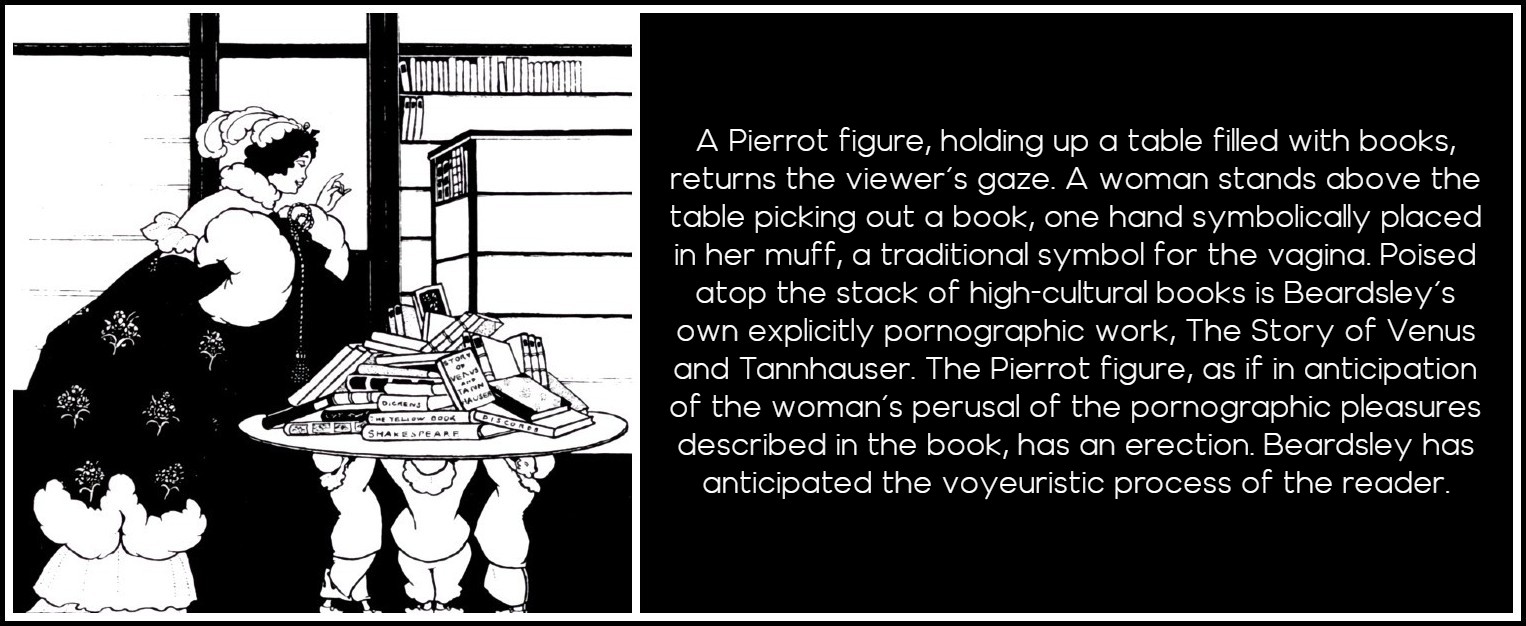

An unused cover design for the Yellow Book plays upon the theme of the New Woman and her books, but goes further in combining the ethos of the bodily reader with that of the voyeur. As in many of his drawings, Beardsley uses a mediating figure to poke fun at, subvert, and expose the eroticism embedded within the voyeur’s gaze. In this particular drawing, a Pierrot figure holds up a table filled with books and returns the viewer’s gaze. A woman stands above the table picking out a book, one hand symbolically placed in her muff, a traditional symbol for a woman’s genitals. Poised atop the stack of high-cultural books1 is Beardsley’s own explicitly pornographic work, The Story of Venus and Tannhauser. The Pierrot figure, as if in anticipation of the woman’s perusal of the pornographic pleasures described in The Story of Venus and Tannhauser, has an erection. Beardsley has anticipated the voyeuristic process of the reader. The voyeur figure, however, also functions as a typical pornographic trope. The narrator/mediator digests the sexually exciting material in advance of a reader/viewer in order to stimulate a similar response in him or her. Beardsley has managed to portray an entire pornographic scenario without appearing to abandon the aesthetic to the pornographic. By using the traditional English bawdy symbology of the lady’s muff, he merely refers to a possible interpretation. Likewise, the Pierrot’s erection is but one in a series of suggestive, graceful lines. The pornographic book, The Story of Venus and Tannhauser, is also a classical tale, a culturally sanctioned myth also used by Swinburne in ‘Laus Veneris’ that operates as a signifier of high culture. All of the pornographic signifiers in the picture—a lady’s muff, a sweeping line, and a classic tale—function doubly as signifiers of bourgeois culture and high art. As with so much of Beardsley’s work, meaning is indeterminate and the erotic content cannot be fixed.

1 – Shakespeare and Dickens; authors reputed to have enjoyed mass audiences, thereby blurring the distinctions between high and low.

Aubrey Beardsley, unused cover design for The Yellow Book, 1894-95

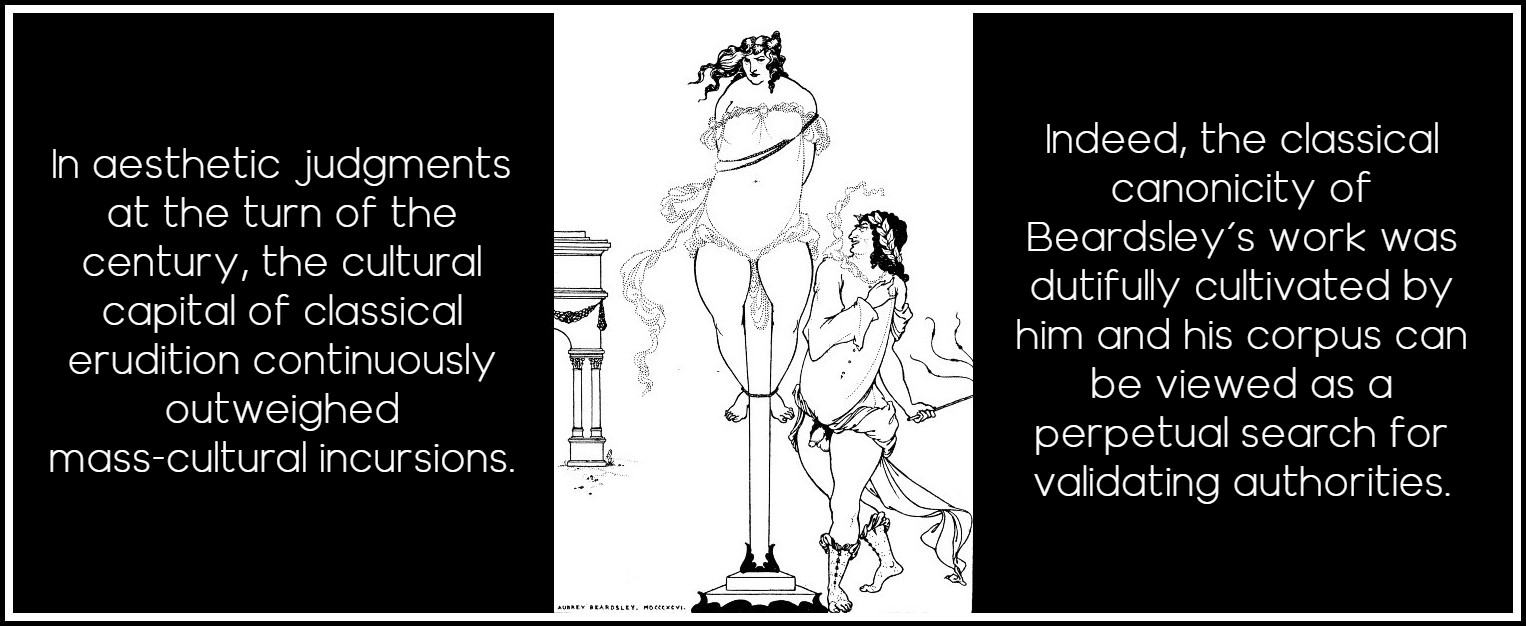

Like Joyce, there are remarkable moments in Beardsley’s works that draw off and imitate the pornographic to such a degree that they challenge the ability of the aesthetic to posit the viewer in a relation of distance and disinterest with them. As also with Joyce, it is Beardsley’s technical skill—the formal elements of his art—that provides a remove from, or a hold upon, the sexual images portrayed. It is no accident, then, that the Lysistrata drawings, while being the most sexually explicit, are also the most consistently praised as ‘the most masterly of all his drawings.’1 Robert Ross found in the Lysistrata drawings a series of validating canonical correspondences, remarking, conceived in the spirit of the eighteenth century, the period of graceful indecency, there is here, however, an Olympian air, a statuesque beauty, only comparable to the antique vases.2 Ross’s comparison was no doubt led by the fact that the drawings are ‘illustrations’ of Aristophanes’ classical play. Indeed, as in the use of the Ulysses myth, there was a remarkable leniency granted to art conceived in the classical vein. Yet Ross’ comments also reveal an anxious effort to classicize what was clearly perceived as ‘indecent.’ In aesthetic judgments at the turn of the century, the cultural capital of classical erudition continuously outweighed mass-cultural incursions. Indeed, the classical canonicity of Beardsley’s work was dutifully cultivated by him and his corpus can be viewed as a perpetual search for validating authorities. In his letters, Beardsley described his work as ‘severe in execution,’ and indeed the Lysistrata drawings are stark, simple, and balanced—all words which conjure up classical design. Referring to the pornographic nature of the Lysistrata and Juvenal drawings, a reviewer for the New Statesman noted: He is haunted by the male genitals, and he exaggerates their proportions in a way normally associated with the vulgarest pornography; but they must be among the most refined, meticulous, decorative and reverential drawings of the male genitals ever devised.1

1 – Holbrook Jackson, The Eighteen Nineties (1913; London: Jonathan Cape, 1931) 103

2 – Robert Ross, Aubrey Beardsley (London: John Lane, the Bodley Head, 1921) 48

3 – Christopher Snodgrass, Aubrey Beardsley: Dandy of the Grotesque (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995) 171

Aubrey Beardsley, Juvenal Scourging a Woman, 1896

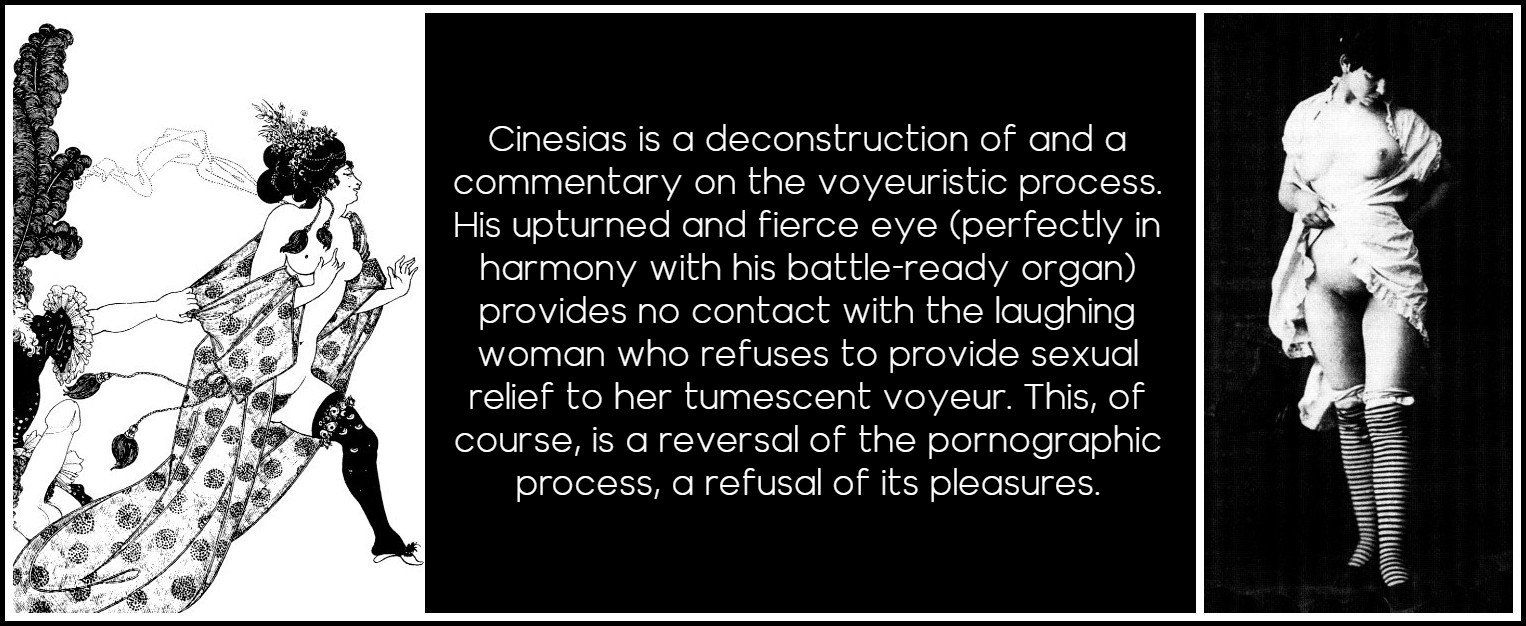

Cinesias Entreating Myrrhina to Coition demonstrates a unique balancing between the aesthetic and the pornographic. That the image depicted was common to pornography can be demonstrated in its likeness to a photograph of a woman in similar garb taken around 1880. Each image presents a frontally exposed woman in stockings, loosely draped with a robe. The photograph, organized for the consumption of the voyeur, features the ‘bashful wantonness’ Stephen Dedalus found in the pictures he used, leaving the viewer’s gaze unchallenged. Myrrhina both complies with and disrupts this visual organization. For while her eyes are cast aside from the viewer’s, it is not in a gesture of ‘bashful wantonness.’ She is all but laughing, seemingly unconcerned with the viewer. As in the unused cover for the Yellow Book where the voyeuristic Pierrot figure stands diminutively aside while eyeing a sexually self-satisfied woman, Cinesias is in this picture marginalized to a grotesquely small shape at the drawing’s edge, made comic by his overwhelmingly disproportionate, erect penis. As with the Pierrot figure above, Cinesias is a deconstruction of and a commentary on the voyeuristic process. Cinesias’ upturned and fierce eye (perfectly in harmony with his battle-ready organ) provides no contact with the laughing woman who refuses to provide sexual relief to her tumescent voyeur. This, of course, is a reversal of the pornographic process, a refusal of its pleasures. Cinesias’ grand penis, however, is quite in keeping with the pornographic, where the prodigious size of male genitals is a continuous source of sublime wonder, especially to the women who encounter them.1

1 – A classic example of this can be found in Fanny Hill when the heroine describes the penis of a young messenger in the following manner: I saw, with wonder and surprise, what? not the plaything of a boy, not the weapon of a man, but a maypole of so enormous a standard that, had proportions been observed, it must have belonged to a young giant. As is typical of pornography, the penis evokes the sublime. In Fanny’s words, it stood, an object of terror and delight.

Aubrey Beardsley, Cinesias Entreating Myrrhina to Coition, 1896 | Anonymous. From 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839-1939 (Uwe Scheid Collection, Taschen)

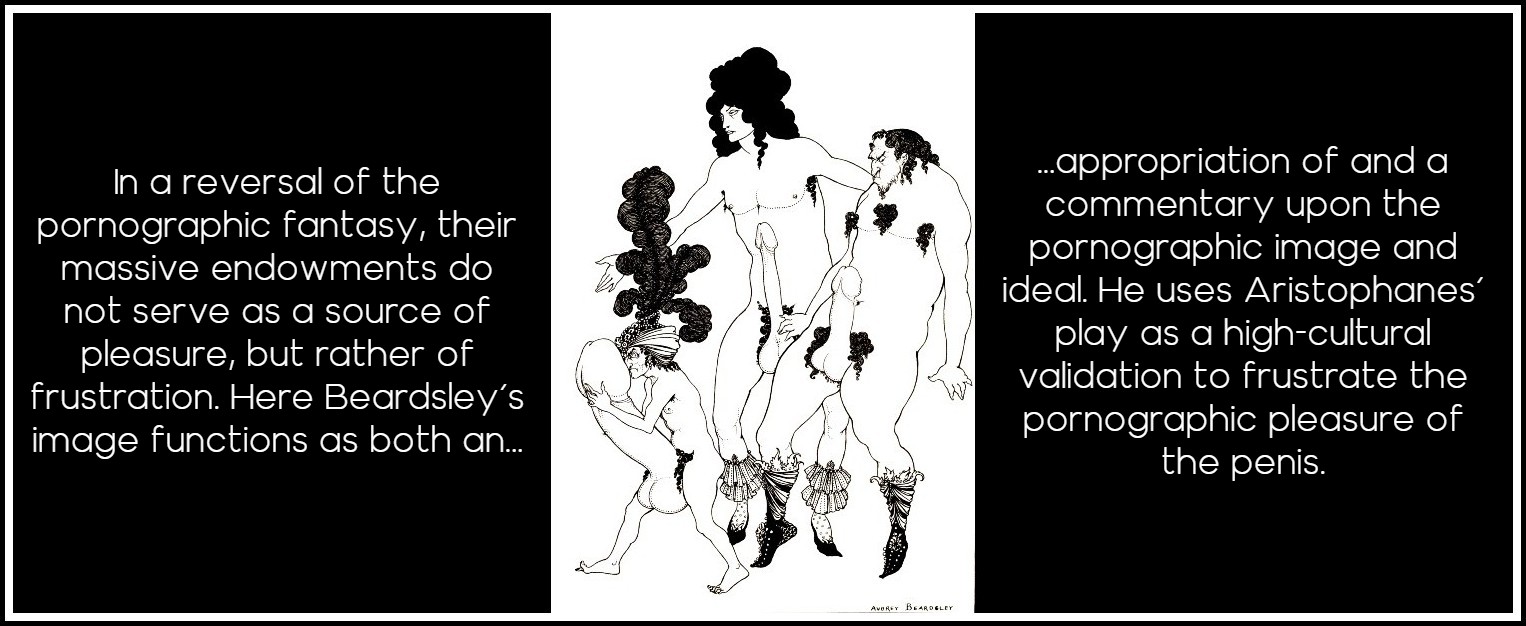

The Lacedaemonian Ambassadors is certainly a tribute to, and a poking fun of, the pornographic tradition of the sublime penis, particularly in the knowledge that these men will not find pornography’s quintessential willing partner. In a reversal of the pornographic fantasy, their massive endowments do not serve as a source of pleasure, but rather of frustration. Here Beardsley’s images function as both an appropriation of and a commentary upon the pornographic image and ideal. Beardsley uses Aristophanes’ play as a high-cultural validation to frustrate the pornographic pleasure of the penis. In Cinesias Entreating Myrrhina to Coition he further orders and distances the art from the pornographic by creating a visual focus apart from the bodies depicted. As Christopher Snodgrass has commented, the eye-catching focus of the drawing is, rather than the sexually displayed bodies, the decoratively designed clothing and headpieces. The dark or shaded parts of the work, those that call attention to themselves, are indeed the decorative details, such as costume, headpiece, or hair. The physically exposed parts of bodies are left in white, the same as the background upon which they lie. In this way the bodies themselves are underemphasized even while they are in fact the occasion of the drawing

Aubrey Beardsley, The Lacedaemonian Ambassadors, 1896

ALLISON PEASE: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments