Part 3 of 4

JAMES JOYCE AND AUBREY BEARDSLEY: AESTHETICS OF OBSCENITY

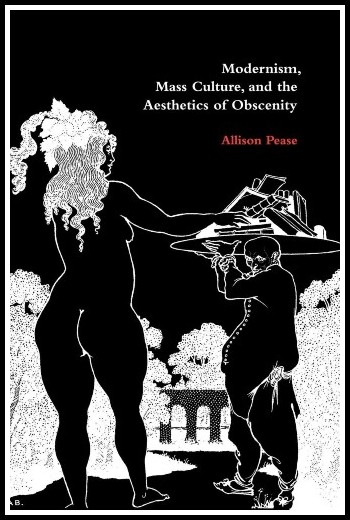

Allison Pease

Posted by kind permission of Allison Pease, Professor of English, Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York.

From Allison Pease, Modernism, Mass Culture, and the Aesthetics of Obscenity (Cambridge University Press, 2000) pages 100-115

THIS IS PART 3 OF 4 PARTS. READ PART 1 FIRST.

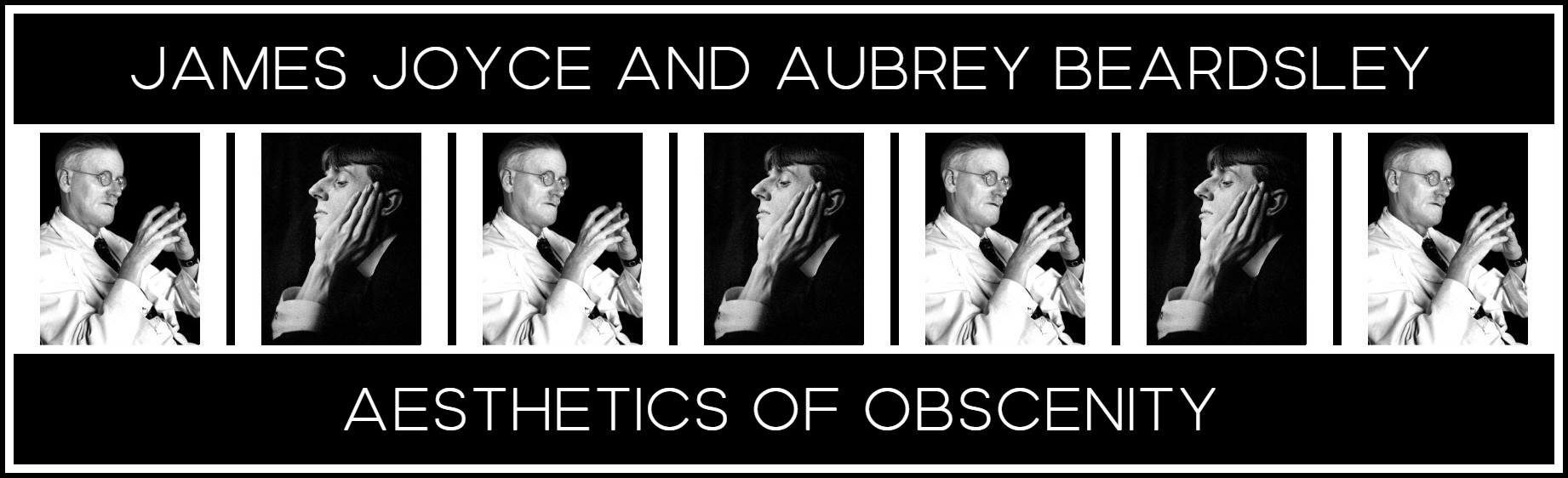

James Joyce, 1927 (Photo: Berenice Abbott) | Aubrey Beardsley, 1890 (Photo: Frederick Hollyer)

V. MASTURBATION

The corruption attributed to sexually overt pictures and books takes a material form in the temptation such works offer to ‘self-abuse,’ or masturbation. The term ‘self-abuse’ serves as a reminder of the conflicted subject-formation implicated in the bourgeois denial of the body and its ‘spurious’ pleasures. While certainly masturbation was the feared outcome of access to ‘dangerous’ works, it was absolutely beyond the margins of the representable, for in representing masturbation one acknowledged the possibility of a selfishly physical and sexual subjectivity. Both Beardsley and Joyce represent the physically stimulating powers of books as well as representations of the act of masturbation itself. When Bloom opens the Sweets of Sin in ‘Wandering Rocks’ and begins to read the sexual body—Her mouth glued on his in a luscious voluptuous kiss while his hands felt for the opulent curves inside her deshabille—the narrative features the reaction of a bodily reader:1 Warmth showered over him, cowing his flesh. Flesh yielded amid rumpled clothes. Whites of eyes swooning up. His nostrils arched themselves for prey. Melting breast ointments (for him! For Raoul!). Armpits’ oniony sweat. Fishgluey slime (her heaving embonpoint!). Feel! Press! Crushed! Sulpher dung of lions! Bloom surrenders to the technology of pornography and subjects his reading to the interests of his senses. He enters into a specific reading practice that is intended to engage the mind and body in a sexual interrogation or incitation. In this passage Bloom exhibits a self-reflexivity about his bodily pleasure peculiar to the modern pornographic sensibility.

1 – The actual pornography is italicized, as in the text.

James Joyce, Sketch of Leopold Bloom, with first line of Homer’s Odyssey in Greek, 1926 | Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections

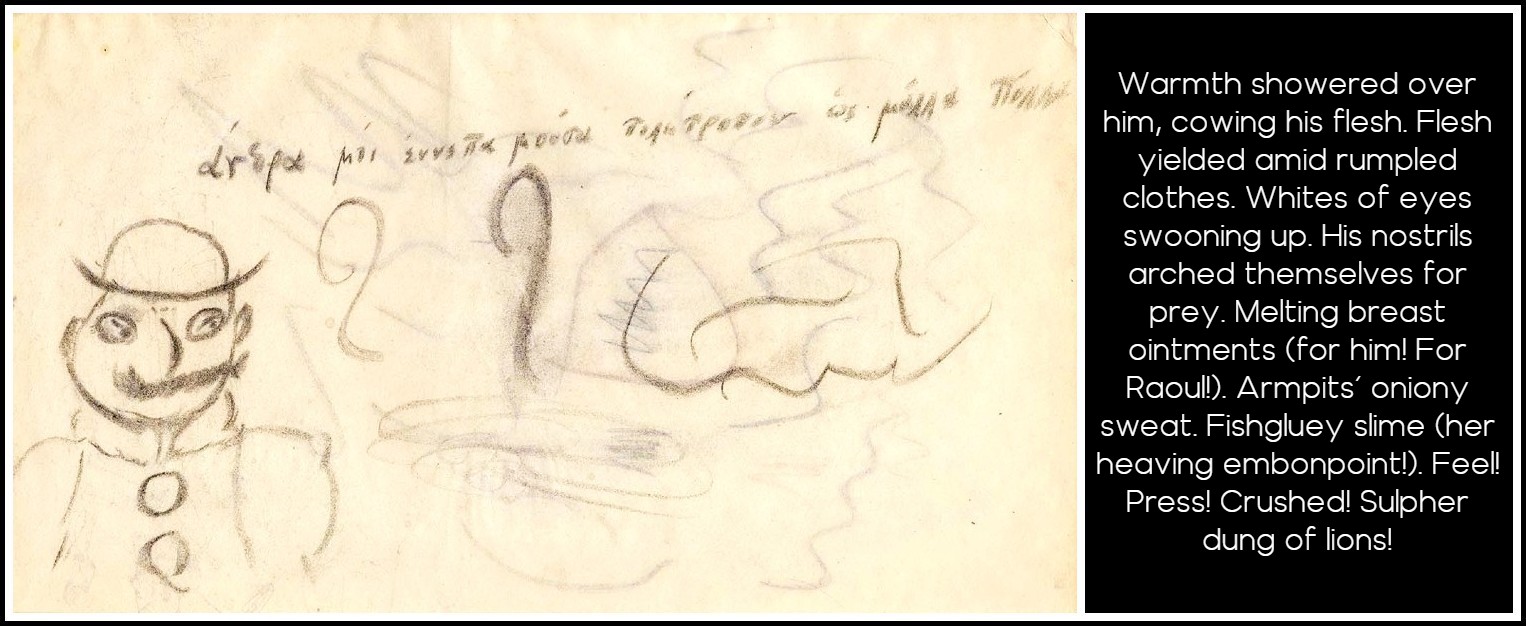

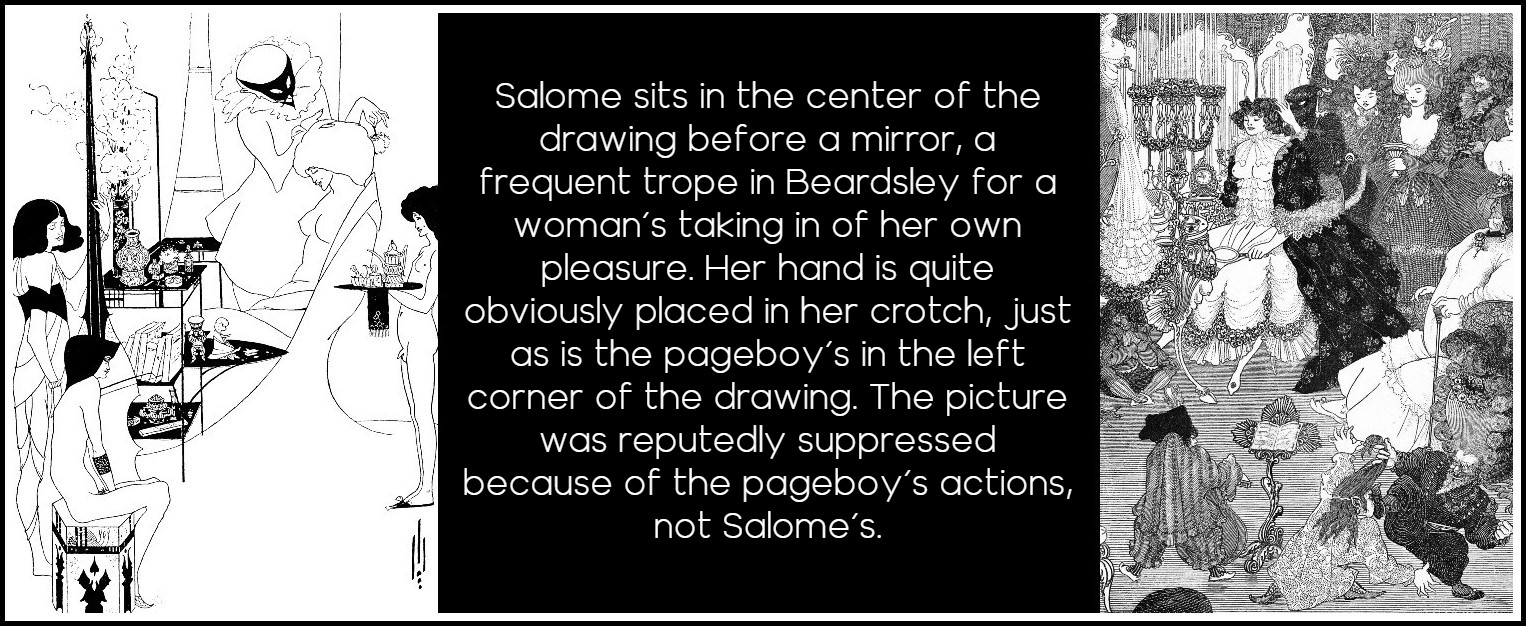

Equally peculiar to the modern pornographic sensibility is the admission and acceptance of masturbation. For while good Victorians like My Secret Life’s Walter denied the impulse to masturbate, moderns, beginning quite radically with Beardsley, acknowledged masturbation. Two of Beardsley’s toilet scenes, The Toilette of Salome, first version, and The Toilette of Helen, feature the act in notably similar ways. After the 1893 Salome drawing was suppressed, the 1895 Helen drawing appeared as a reinterpretation of the same theme with an attempt to get the picture past his censors. In The Toilette of Salome, first version, carnal desire is quite simply represented. Salome sits in the center of the drawing before a mirror, a frequent trope in Beardsley for a woman’s taking in of her own pleasure. Her hand is quite obviously placed in her crotch, just as is the pageboy’s in the left corner of the drawing. The picture was reputedly suppressed because of the pageboy’s actions, not Salome’s, and one must infer that the depiction of a barely disguised penis extending from a pubic tuft in the male crotch makes his gesture more overt, more anatomically representational and therefore similar to pornography. Snodgrass also points out that the pageboy possesses the buckling spine traditionally associated in the Victorian mind with what results from seminal fluids being wasted in autoeroticism.1

1 – Christopher Snodgrass, Aubrey Beardsley: Dandy of the Grotesque (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995) 65

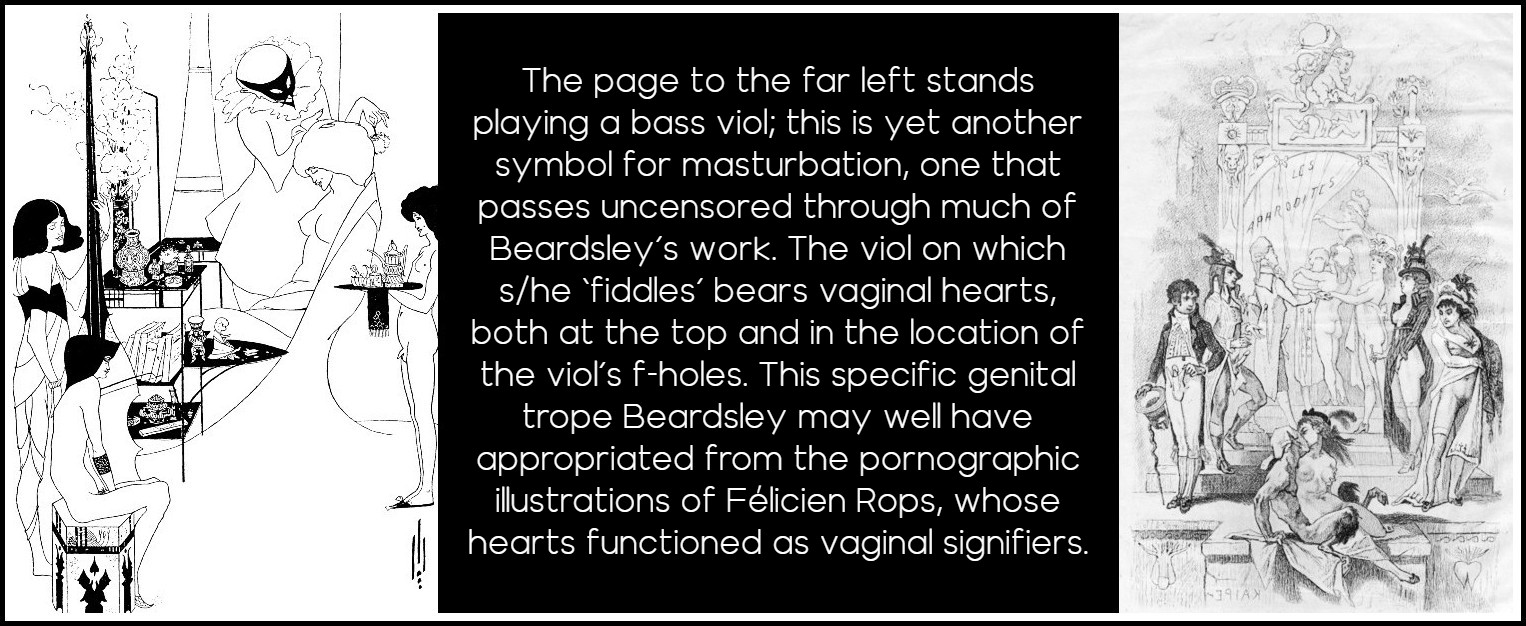

Aubrey Beardsley: The Toilette of Salome, 1893 | The Toilette of Helen, 1895

The page to the far left stands playing a bass viol; as noted by Freud, this is yet another symbol for masturbation, one that passes uncensored through much of Beardsley’s work. The viol on which s/he ‘fiddles’ bears vaginal hearts, both at the top and in the location of what are called the viol’s f-holes. This specific genital trope Beardsley may well have appropriated from the pornographic illustrations of Félicien Rops, whose hearts functioned as vaginal signifiers. The page holding a tray of coffee has exposed genitals (noticeably different from the erect shape of the coffee pot spout he holds). The action is quite bare and—despite the sweeping harmonious lines, integrating symmetry, and the unity of theme—it is a dangerous theme that outweighed the few high-cultural signifiers to save this work from censorship. This is one instance where style does not invoke form. The pornographic, itself always stylized, asserts itself over the aesthetic.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Toilette of Salome, 1893 | Félicien Rops, Les Aphrodites, 1864

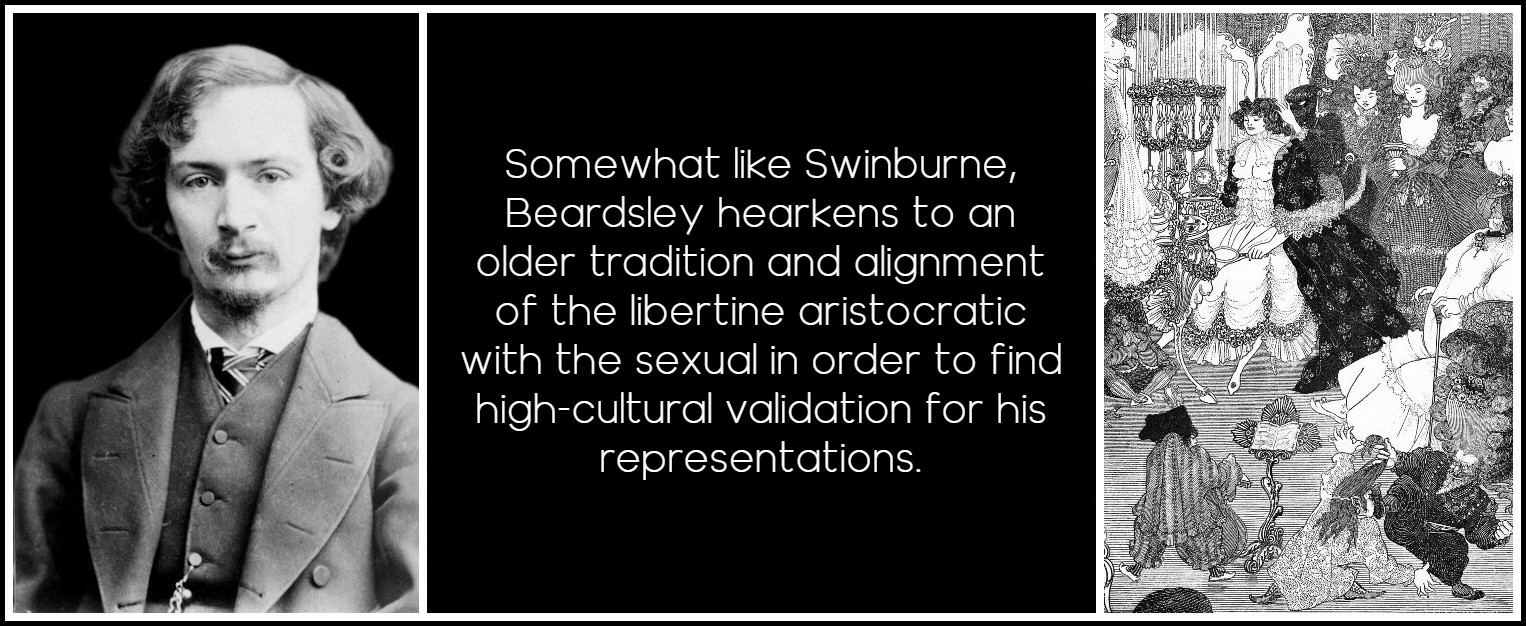

In contrast, The Toilette of Helen features none of the blatant sexual exposure of the Salome drawing. Though sexuality and self-pleasuring are its themes, the drawing masks them successfully through ornate, rococo designs and eighteenth-century bawdy symbology. Helen/Venus appears at center and embodies a series of high-cultural and low-cultural contradictions. Dressed in refined, aristocratic undergarments, her breasts are exposed. The shaggy ribbing of her corset is set in contrast to the smooth simplicity of her breasts, a contrast evocative of a centaur or satyr, thus implicating her with the bestial. The implication is furthered by the juxtaposition of the cloven-hoofed leg of her dressing table against her own similarly shaped foot. Here the sexual is co-implicated with the bestial and Helen is shown to be both refined and aristocratic while at the same time bestial, sexual. Helen captures in miniature the paradoxical nature of Beardsley’s sexual art. It is elegant, civilized, and aspires toward beauty (Beardsley’s women at toilette are a frequent evocation of the artificial beauty to which he aspires) while containing within that form an untamed lust barely permissible by the society that seeks to control it. By placing Helen in the eighteenth century and positioning her as an aristocratic lady with attendants, Beardsley purposefully circumvents the bourgeois hegemony of his own century. Indeed, somewhat like Swinburne, he hearkens to an older tradition and alignment of the libertine aristocratic with the sexual in order to find high-cultural validation for his representations.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, 1865 | Aubrey Beardsley, The Toilette of Helen, 1895

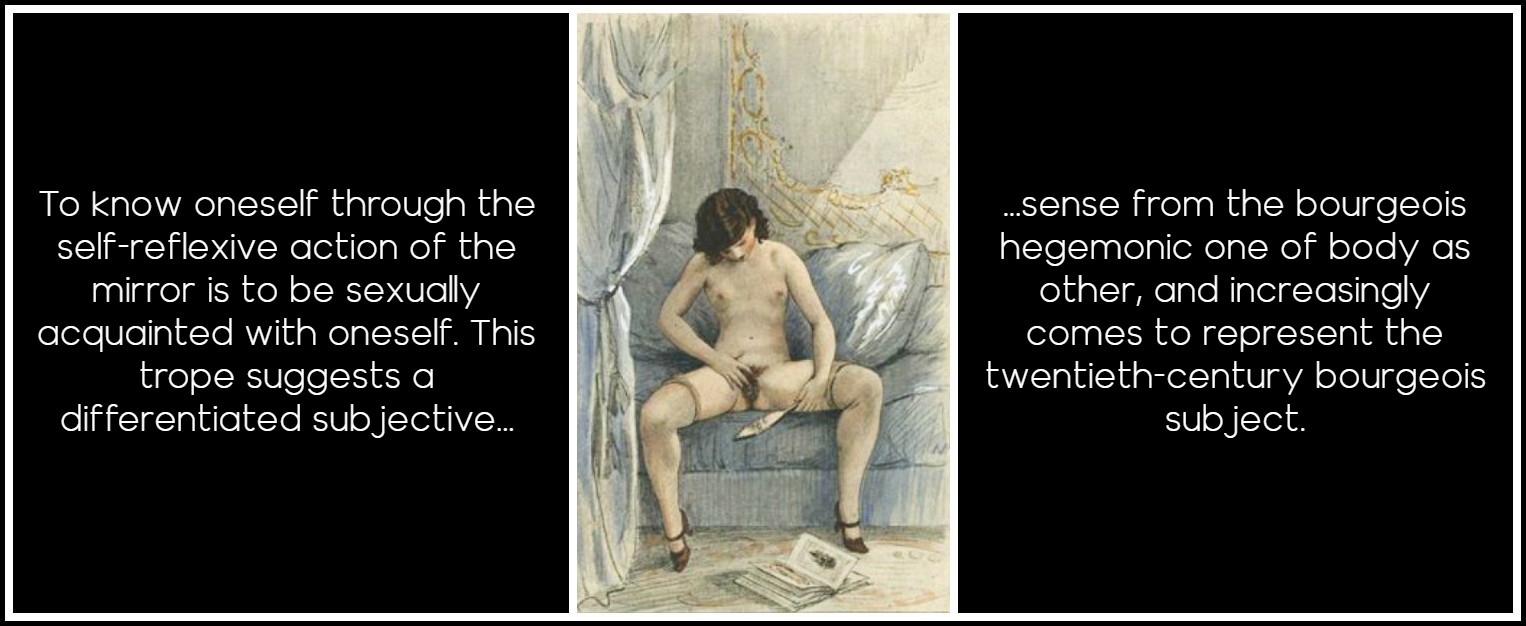

The mirror positioned between Helen’s widely spread legs functions as a symbol of self inspection, i.e. masturbation. A picture drawn for a 1920s era pornographic ‘best-seller,’ An Up-to-date Young Lady by Helena Varley, featured a similar gesture on the part of its heroine. To know oneself through the self-reflexive action of the mirror is to be sexually acquainted with oneself. This trope suggests a differentiated subjective sense from the bourgeois hegemonic one of body as other, and increasingly comes to represent the twentieth-century bourgeois subject. That is, with the deeper penetration of moral-medical health into bourgeois subjectivity, sexual subjecthood found its answer in the new fields of sexology which created sexual subjects in order to further establish health and morality. One can see in the illustration to An Up-to-date Young Lady that the young woman has on the floor with her a medical sexual manual of some sort that encourages her self-exploration. While the manual is on the one hand subversive in its incitement to sexual behavior, it is on the other a scientifically sanctioned validation of the sexual body, a bourgeois affirmation that recodifies what was once subversive. A sexual self becomes, in the twentieth-century, a healthy self, an integration of two previously separate categories. This is an attitude, however, that doesn’t penetrate the cultural consciousness completely until well into the 1960s, and while D. H. Lawrence was an early advocate, Beardsley and Joyce remained equivocal about sexual self-knowledge and moral-medical health.

Illustration by Paul-Émile Bécat for Une jeune fille à la page by Michele Nicolai, aka Héléna Varley, 1938

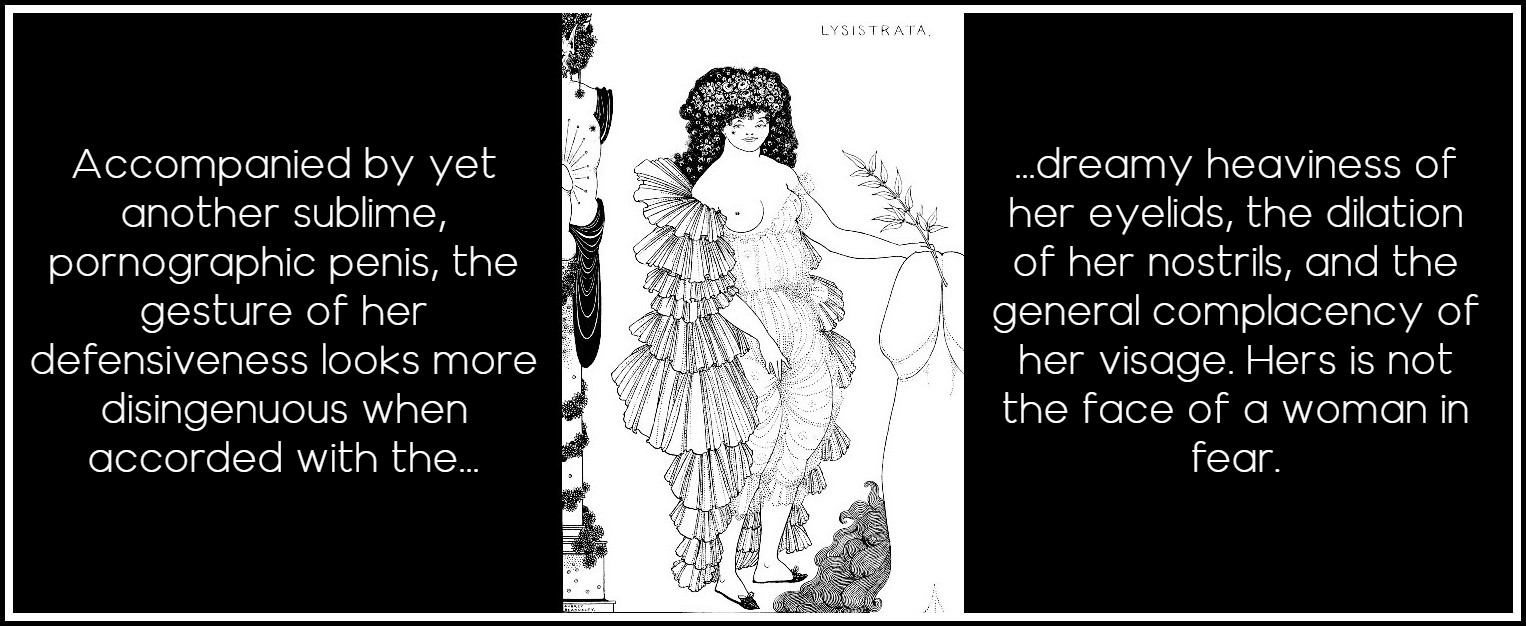

Equivocality functions as an important guise for the masturbatory incitements of many of Beardsley’s representations. In Lysistrata Shielding her Coynte, Lysistrata has her hand ambiguously placed before her genitals. The illustration’s title directs a reading of the gesture, while the depiction itself is ambiguous. As Linda Zatlin has commented, the parting of her fingers in what might be construed as a caress instead of an attempt to shield her genitals reinforces her sexual knowledge even as it subverts the generally accepted public view against masturbation.1 Accompanied by yet another sublime, pornographic penis, the gesture of her defensiveness looks more disingenuous when accorded with the dreamy heaviness of her eyelids, the dilation of her nostrils, and the general complacency of her visage. Hers is not the face of a woman in fear. The opened rosebuds in her hair, usually drawn much tighter in Beardsley’s works, suggest a dilated opening below. This is further accentuated by the placement of her two fingers at her crotch, suggesting the labia that might be seen through her otherwise transparent dress. The hand both covers and uncovers, shields and displays. The erect terminal god at her right functions as a voyeur to her pleasure (and another mediating figure for the viewer’s gaze) while simultaneously exposing, as in Joyce and a certain class of pornography, the latent sexuality of the classical figure.

1 – Linda Gerstner Zatlin, ‘Aubrey Beardsley’s “Japanese” Grotesques,’ Victorian Literature and Culture, 25:1 (Spring 1997) 87-108

Aubrey Beardsley, Lysistrata Shielding her Coynte, 1896

Beardsley’s publisher, Leonard Smithers, published a book, Priapeia, in 1888 that housed a series of epigrams on ‘terms’ or statues of Priapus, phallic ornaments erected in the gardens of wealthy Romans. The short Latin verses of Priapeia, translated on opposing pages into English, were written mostly from the point of view of the sinister, proud Priapus who threatens all who trespass his garden with a spearing by his 12-inch grand pole. The term is flirtatious with women, boys, and men, and will pierce anything. One brief example can be found in verse forty-eight: Although you see that part of me to be wet by which I’m signified to be Priapus; tis not dew, believe me, nor is it hoarfrost, but that which is wont to gush forth spontaneously when my mind recalls a wanton girl. The term was featured prominently in pornographic illustrations of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Beardsley’s close access to Smithers’s library makes it likely that he was familiar with Priapeia as well as many of the typically French pornographic novels in which such figures were celebrated. As in Ulysses, the Lysistrata series displays an apparent relish in exposing high culture’s beloved classical culture for the sexually suggestive culture Beardsley read it to be. Beardsley favored representing periods predicated on order, symmetry, and harmony—the classical and neo-classical—in order to exploit their contradictions, to suggest that the formal, aesthetic qualities so typically associated with the classical were in fact bound up with the pornographic.

Priapus | British Museum

One of literature’s most notorious masturbation scenes is the passage in ‘Nausicaa’ where Bloom masturbates before a partially exposed Gerty MacDowell. Couched in the mass-produced language of sentimental romance, ‘Nausicaa’ is the story of low culture’s longing and attempt to assimilate, or be appropriated by, high culture (in a more radical sense it could be said to be the opposite: Ulysses’ longing to assimilate and be appropriated by low culture). It is also the story of its inevitable failure as a result of the false ideology perpetuated through mass man’s inevitable interpellation by the commercialism of popular culture, which colonizes the high merely as a set of empty signifiers to promote desire. For in addition to Gerty’s pretense to class through commercial products and ladies’ magazines, Gerty vies for Bloom’s attention by imitating high art rather than the ‘improper’ ones. That is, as Margot Norris has pointed out, she gives a static rather than a kinetic performance, trying desperately to portray an idealized figure (of the sentimental sort she reads about).1 Gerty’s narrative, describing the waxen pallor of her face was almost spiritual in its ivorylike purity though her rosebud mouth was a genuine cupid’s bow, Greekly perfect, reveals a longing in Gerty to assimilate herself to the cultural standards of high art, to become the reified manifestation of that metaphysical aura that can only exist for her as desire and the wish to be so desired. Bloom’s bodily consumption of her high-art imitation becomes not just another instance of kitsch consumerism, but a poignant one in their mutual submission to a desire for a cultural validation from which they are both debarred.

1 – Margot Norris, Joyce’s Web: The Social Unraveling of Modernism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992) 177

Fionnula Flanagan as Gerty MacDowell in James Joyce’s Women | Michael Pearce, director, 1985

Schematically, ‘Nausicaa’ is another of Joyce’s exercises in controlled figuration. It effects the formal sublimation associated with high art even while it exposes the ‘low’ genres of affect: sentimental fiction and pornography. By displacing and metaphorically figuring rather than mimetically representing what happens, the text draws attention to the action, making it all the more ridiculous as it is filtered not through the language of pornography, but of sentimental romance. While Bloom’s actions are those reserved for pornography, and he demonstrates the pornographic technique of consumptive voyeurism, it is not until he pulls the metaphors of Gerty’s passage together with his anatomy, My fireworks. Up like a rocket, down like a stick, that any connection between Bloom and the carnivalesque masturbation scene is linguistically made. Obviously such a connection is quite insistently implied throughout, but the language itself is untainted. This is made clear in the climactic scene: and she let him and she saw that he saw and then it went up so high it went out of sight for a moment and she was trembling in every limb from being bent so far back he had a full view high up above her knee no-one ever not even on the swing or wading and she wasn’t ashamed and he wasn’t either to look in that immodest way like that because he couldn’t resist the sight of that wondrous revealment half offered like those skirt-dancers behaving so immodest before gentlemen looking, and he kept on looking, looking. She would fain have cried to him chokingly, held out her slender, snowy arms to come to him, to feel his lips laid on her white brow the cry of a young girl’s love, a little strangled cry, wrung from her, that cry that has wrung through the ages. And then a rocket sprang and bang shot blind and O! then the Roman candle burst and it was like a sign of O! and everyone cried O! O! in raptures and it gushed out of it a stream of rain gold hair threads and they shed and ah! they were all greeny dewy stars falling with golden, O so lively! O so soft, sweet, soft!

Mariette Lydis, Leopold Bloom, 1925

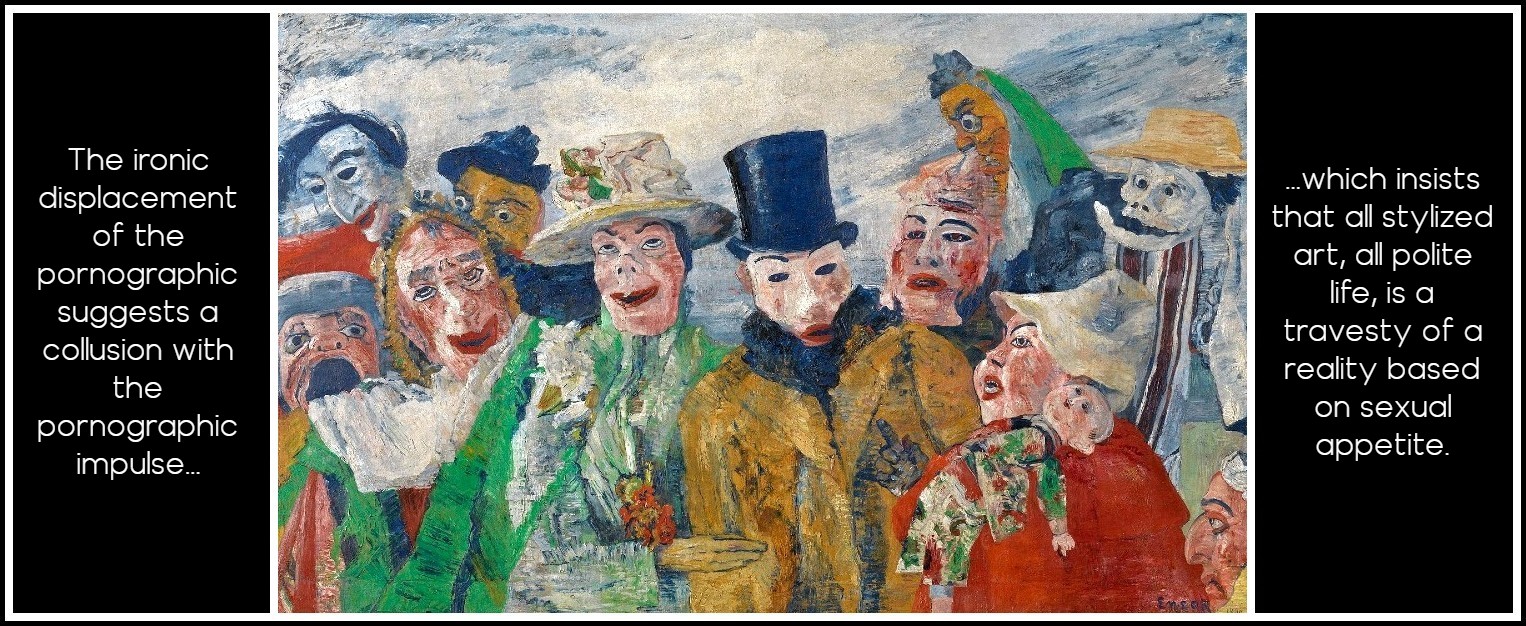

Much in the style of Molly’s soliloquy, the preceding passage is syntactically askew. It denies the very form typically used to express such actions, and in doing so foregrounds that form’s absence. Relying on hegemonic pornographic form to produce its own inversion, the passage is but another example of the Bakhtinian carnivalesque. As in the carnival where high culture is inverted or suspended in order to celebrate the body of the people (the grotesque as opposed to the classical in Bakhtin’s conception), so here the normative narrative form one would expect to depict such an action, pornography, is denied in order to subvert the body. The body is displaced; it evades narrative form. The body is at once everywhere and nowhere. Gerty and Bloom seek their private bodily pleasures while the beach itself is filled with the bodies of pleasure-seekers watching the fireworks. What is lost is the distance upon which the aesthetic form relies, uniqueness is lost to multiplicity. All pleasure is conflated into climactic ‘O!’s where individual pleasure is indistinguishable from the whole. Desire in the reader is controlled by a flow of intervening discourses and a denial of the mimetic. Pleasure is aesthetically controlled by decentering it from individual pleasure to carnivalesque pleasure. The ironic displacement of the pornographic in ‘Nausicaa’ suggests a collusion with the fundamental pornographic impulse which insists that all stylized art, all polite life, is a travesty of a reality based on sexual appetite. Thus while Ulysses disdainfully mocks low-cultural pulp fiction, its high-cultural aspirations are simultaneously undermined by the pornographic discourse it denies only to highlight later.

James Ensor, The Intrigue, 1890

After Gerty’s narrative, Bloom makes the connections between his reaction to Gerty’s exposure and his acquaintance with pornography clear. Anyhow I got the best of that, he says, Damned glad I didn’t do it in the bath this morning over her silly I will punish you letter. Bloom searches for representations that will approach the pornographic in order to subject them to his bodily pleasure, a practice he has learned from pornography. Fantasizing about the ‘shoals’ of women typists and clerks (with whom he classes Gerty) who want sexual gratification, Bloom recalls A Dream of Well-Filled Hose, a mutoscope series ‘for men only’ that he has seen at Mutoscope pictures on Capel Street. Bloom continues to reinforce the turn-of-the-century stereotype of mass man and mass culture. Exposed to the debasing effects of mass culture, mass man becomes an effect of their technique, an expression of the urge to subjugate art and representations to the body. The irony of the attempt to bring representations closer to the body is that the representations quickly become the mediation of the body. Bloom is a perfect example of one whose sexuality becomes mediated not through his own imagination, but rather through the discursive and representational practices set into motion through pornography. When Bloom hires a prostitute to say dirty words to him, the woman’s own sexuality is displaced onto the words she can generate for him. What is exciting for him is not her body, but her own reproduction of discursive practice.

James Joyce, Sketch of Leopold Bloom, 1926 (detail) | Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections

VI. SADO-MASOCHISM

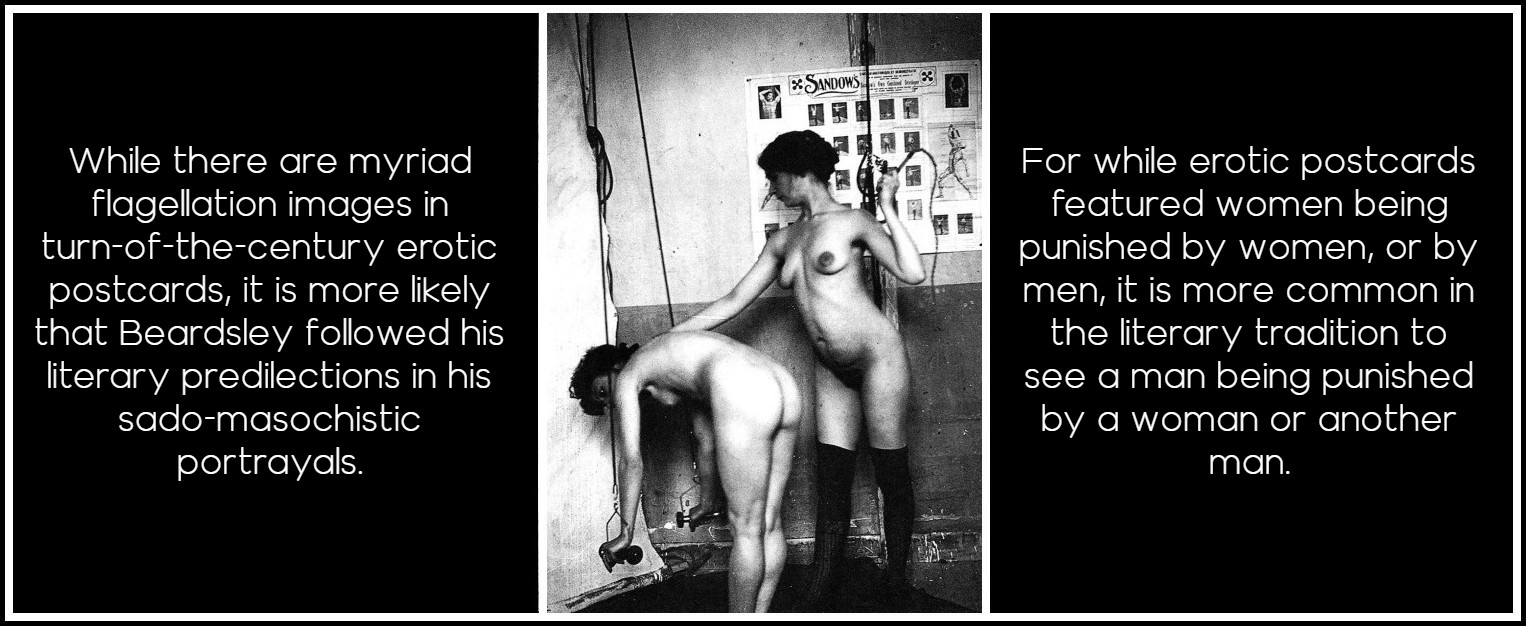

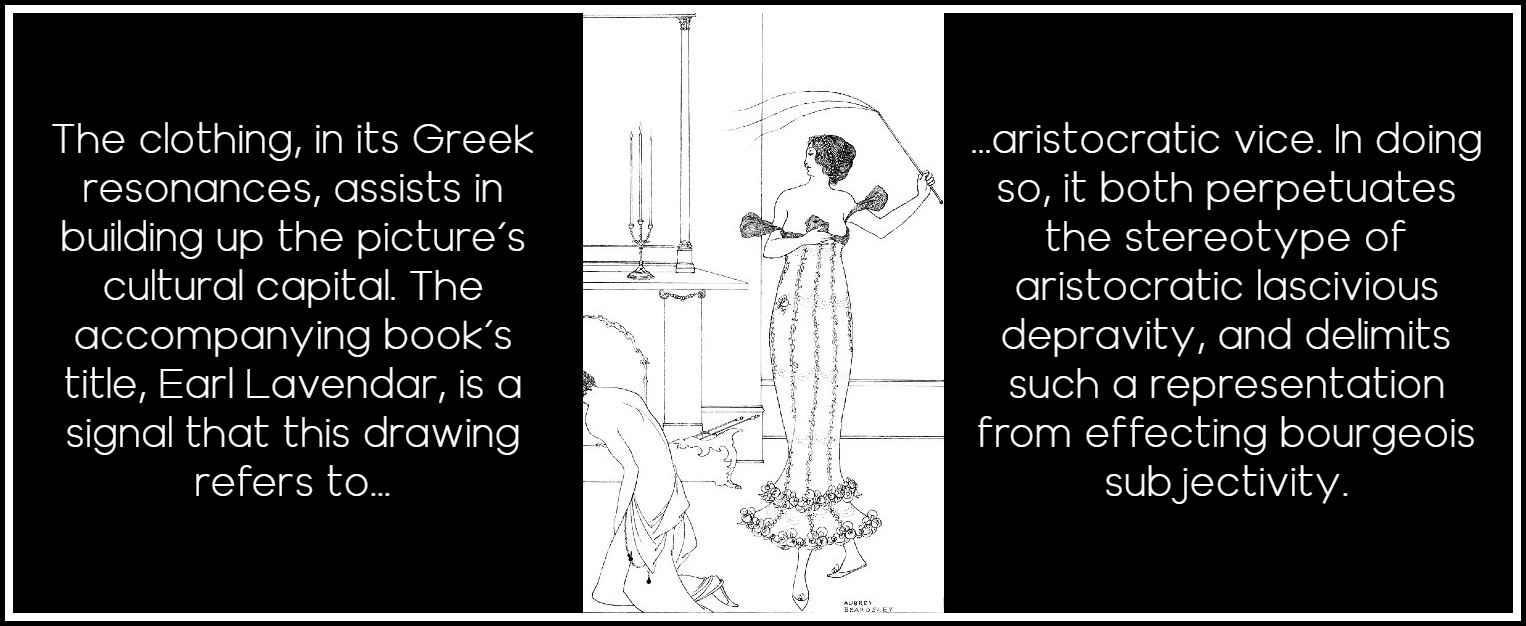

If masturbation was a sexual practice infrequently expressed in Victorian pornographic works, sado-masochism was a well-worn trope that Beardsley and Joyce made use of in their works. Steven Marcus has suggested that in the nineteenth century the literature of flagellation assumed in its audience an interest in and a connection with the higher gentry and aristocracy, those with the common experience of education at public school.1 Indirectly, then, sado-masochism (in its most commonly expressed form, flagellation) is a signifier of high culture and/or high-cultural vice. Beardsley plays on this notion of flagellation in his frontispiece for John Davidson’s Earl Lavendar (1895). While there are myriad flagellation images in turn-of-the-century erotic postcards, it is more likely that Beardsley followed his literary predilections in his sado-masochistic portrayals. For while erotic postcards featured women being punished by women, or by men, it is more common in the literary tradition to see a man being punished by a woman or another man. In that Beardsley depicts an aristocratic woman at flagellant play with a submissive man, he both associates his illustration with that tradition and removes it from either the bourgeois or mass-cultural realm where such a depiction would create an uproar.

1 – Steven Marcus, The Other Victorians (New York: Basic Books, 1964) 253

Photo: Anonymous. From 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839-1939 (Uwe Scheid Collection, Taschen)

The drawing features a woman dressed in a gown of elegant Greek simplicity about to whip a kneeling man, semi-clad in a Greek, robe-like garment. Each of the characters approaches undress. The woman is just holding her dress from falling down her breasts, and the man is about to lower his robe to reveal his buttocks. If Beardsley had chosen to go a step further in undress, surely the picture would have been labeled obscene, for then it would have depicted an action overtly sexual, overtly in connection with the pornographic photographs that feature the same action. His restraint, however, is not simply a capitulation to censorship, but an important signifier of gentlemanly intention. The clothing, in its Greek resonances, assists in building up the picture’s cultural capital. The accompanying book’s title, Earl Lavendar, is a signal that this drawing refers to aristocratic vice. In doing so, it both perpetuates the stereotype of aristocratic lascivious depravity, and delimits such a representation from effecting bourgeois subjectivity. As other to itself, the representation is rendered safe for bourgeois consumption. The impotence of the picture’s threat to bourgeois hegemony is reinforced in its depiction of impotent aristocratic male subjection. The three candles, typically a Beardsleyan phallic symbol, are superseded by the three prongs of the woman’s switch. While there are pokers for the fire (another reference to the switch), there is no blaze in the fireplace (the eighteenth-century symbol for sexual activity). The impotence is quite finally rendered in the male subject’s essential decapitation by the drawing’s frame.

Aubrey Beardsley, Earl Lavender, 1895

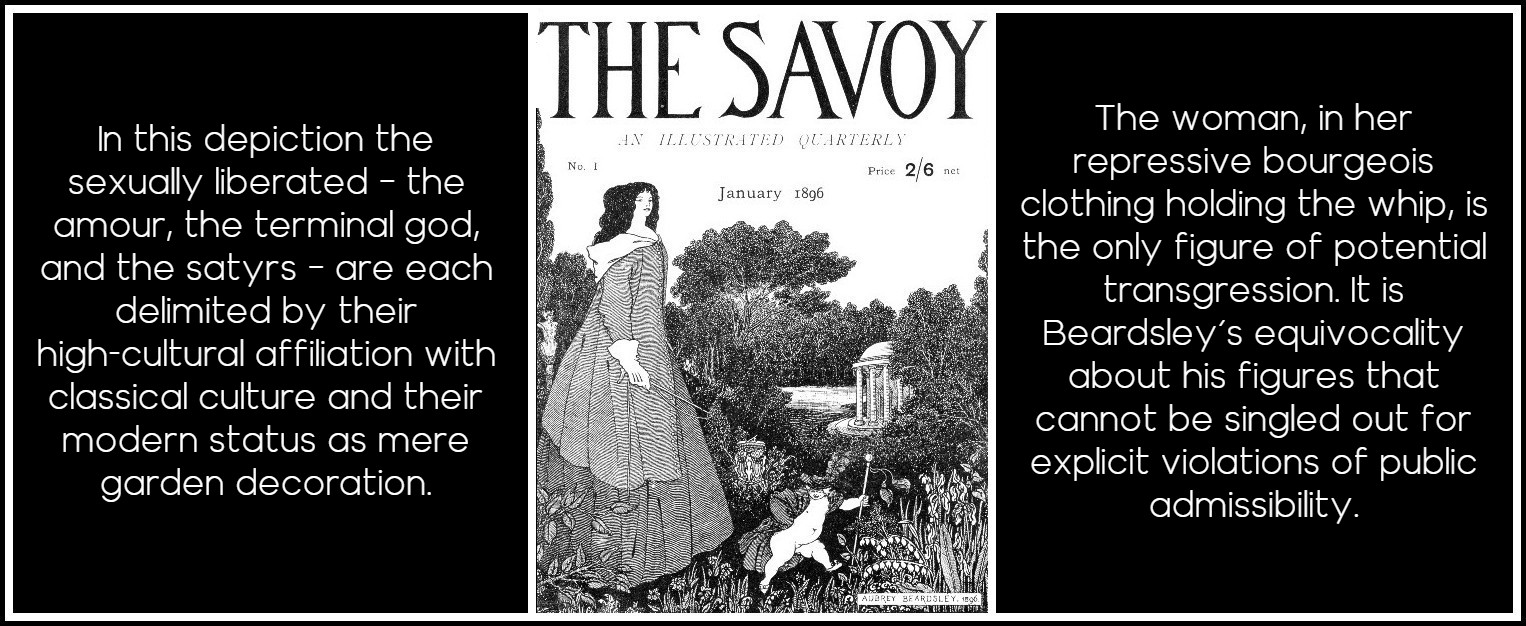

The cover design for the first issue of The Savoy uses the sexual implications of flagellation to create an atmosphere of barely suppressed sexuality. In this instance, Beardsley uses the pornographic to unsettle the culturally staid (in a reversal that nevertheless depends on the culturally staid to preserve its place for art). The Beardsley New Woman is here depicted in staunch dignity, her heavy and severe buttoned coat cloaking any hint of her body (and in that sense drawing attention to it). Standing at attention with whip in hand, she oversees a frontally exposed, dancing amour who exposes the sexuality her clothing and stiff posture repress. Her whip, functioning as a display of control to restrain the amour, functions on the other hand to signify the loss of control that accompanies the sexual perversity for which the whip might be used. If the woman cannot control the amour, neither can she control the seething sexuality of the drawing as a whole. Behind her stands a terminal god, so frequently seen in Beardsley as the signal of lust, and below her sits a sundial decorated by three satyrs. A pagan temple balances the female figure and the whole is surrounded by distinctly pubic vegetation. In this depiction then, the sexually liberated—the amour, the terminal god, and the satyrs—are each delimited by their high-cultural affiliation with classical culture and their modern status as mere garden decoration. The woman, in her repressive bourgeois clothing holding the whip, is the only figure of potential transgression. And again, it is Beardsley’s equivocality about his figures that, while perhaps viewed as threatening by dominant culture, cannot be singled out for explicit violations of public admissibility.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Savoy, No. 1 January 1896

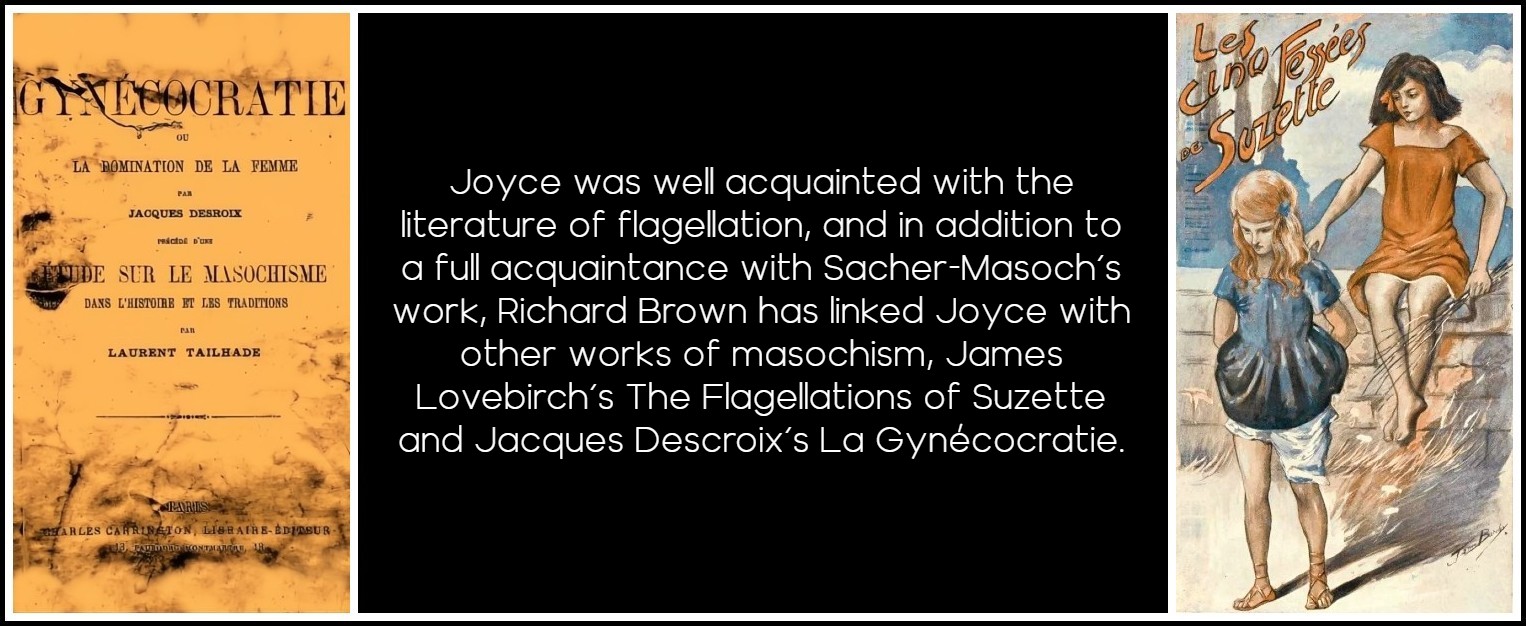

Joyce was well acquainted with the literature of flagellation, and in addition to a full acquaintance with Sacher-Masoch’s work, Richard Brown has linked Joyce with other works of masochism, James Lovebirch’s The Flagellations of Suzette and Jacques Descroix’s La Gynécocratie.1 La Gynécocratie contains many similarities to the ‘Circe’ episode; Joyce may have taken several ideas from the work for his own. In the French story, the protagonist Vicomte Julian Robinson is made, throughout his ‘education’ to wear women’s clothes. Just as Bloom becomes female in the ‘Circe’ episode, Julian becomes Julia; and as Julia is forced to entertain a suitor called Lord Alfred Ridlington who later turns out to have been a woman, so Bloom is offered to Charles Alberta Marsh. Under the governess that Julia serves there are three female pupils—Maud, Beatrice, Agnes—who alternately help or hinder her. Bella Cohen also has three assistants: Kitty, Florry, and Zoe. By featuring Bloom as the masochistic subject, Joyce transgresses the typical class boundaries of the literature of flagellation. He plays upon them interestingly, however, by showing Bloom take the part of the masochist to three upper-class women, Mrs. Yelverton Barry, Mrs. Bellingham, and Mrs. Mervyn Talboys. Bloom’s actions are a commentary on class relations: he is submissive with these women whereas with the housemaid, Mary Driscoll, he is sexually aggressive, laying hold of her body and, when rebuked, commanding silence from her. With the Dublin society ladies, however, the tone changes from commanding to obsequious. While Bloom seeks to be the master of Mary Driscoll’s working-class body, he seeks to be mastered by the ladies’ upper-class bodies.2

1 – Richard Brown, James Joyce and Sexuality (Cambridge University Press, 1985)

2 – Interestingly, for Stephen in Stephen Hero, the middle-class body is anti-sexual. Thinking of Emma he imagines, He would have liked nothing so well as an adventure with her now but he felt that even that warm ample body could hardly compensate him for her distressing pertness and middle class affectations.

Jacques Descroix, La Gynécocratie & Laurent Tailhade, Études sur le masochisme | James Lovebirch, Les cinq fessées de Suzette

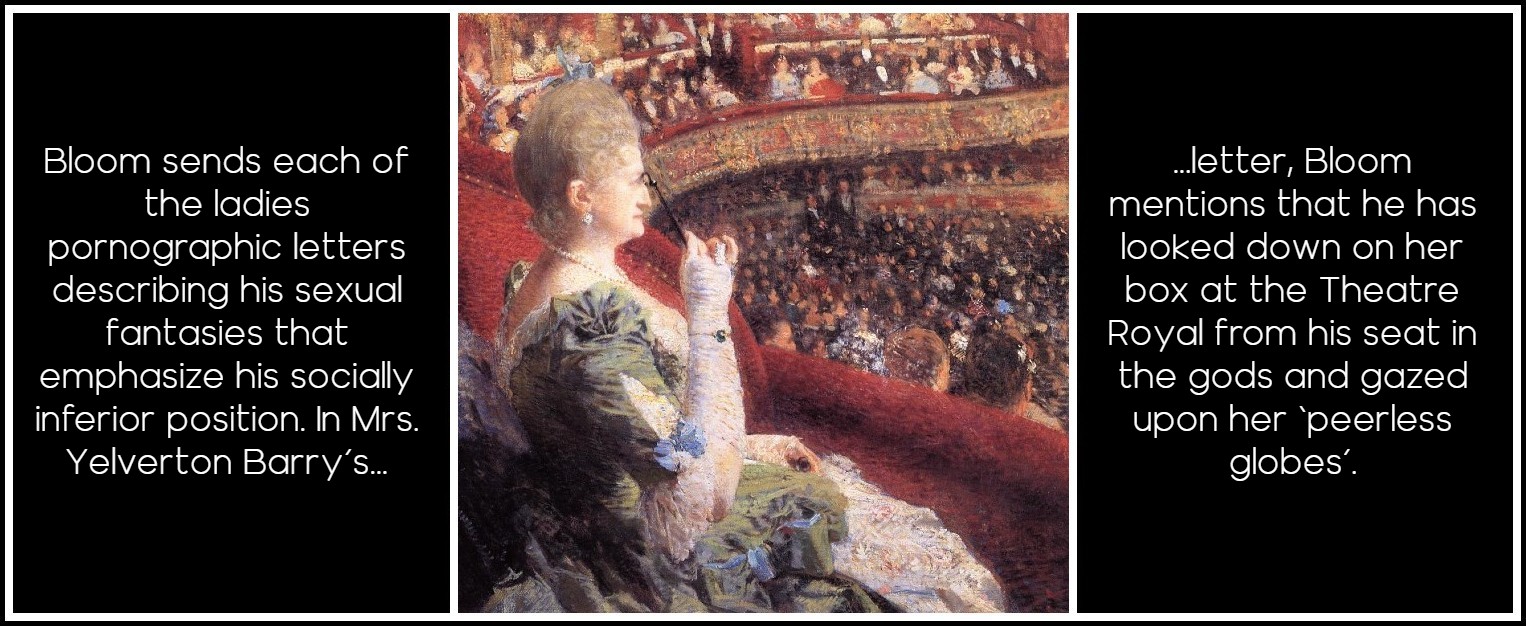

Bloom sends each of the ladies pornographic letters describing his sexual fantasies that emphasize his socially inferior position. In Mrs. Yelverton Barry’s letter, Bloom mentions that he has looked down on her box at the Theatre Royal from his seat in ‘the gods,’ and gazed upon her ‘peerless globes’. Mrs. Bellingham’s account emphasizes her personal wealth, her possession of a personal coachman and ‘hidden treasures in priceless lace’. Her position of domination is further emphasized in Bloom’s denomination of her as ‘a Venus in furs’. Calling Bloom a ‘plebeian Don Juan,’ Mrs. Mervyn Talboys is urged by him to complete her social superiority via a masochistic fantasy where he urges her, to chastise him as he richly deserves, to bestride and ride him, to give him a most vicious horsewhipping. In each of his confessions to the ladies, Bloom attempts to script a fantasy according to the pornographic traditions with which he is familiar. With Mrs. Yelverton Barry he signs his letter with the moniker of pornographic author James Lovebirch. He asks her, as he does with each of the ladies, to perform certain sexual acts, and tells her he wishes to send her a copy of Paul de Kock’s The Girl With the Three Stays.1 Addressing Mrs. Bellingham in several letters as his ‘Venus in furs,’ Bloom writes her physical description in a mock pornographic encomium that she later describes: He lauded almost extravagantly my nether extremities, my swelling calves in silk hose drawn up to the limit, and eulogised glowingly my other hidden treasures in priceless lace which, he said, he could conjure up. He urged me, stating that he felt it his mission in life to urge me, to defile the marriage bed, to commit adultery at the earliest possible opportunity.

1 – Joyce’s English translation of a real book entitled La femme aux trois corsets published in Paris, 1878

Theo van Rysselberghe, Madame Edmond Picard in Her Box at Theatre de la Monnaie, 1886

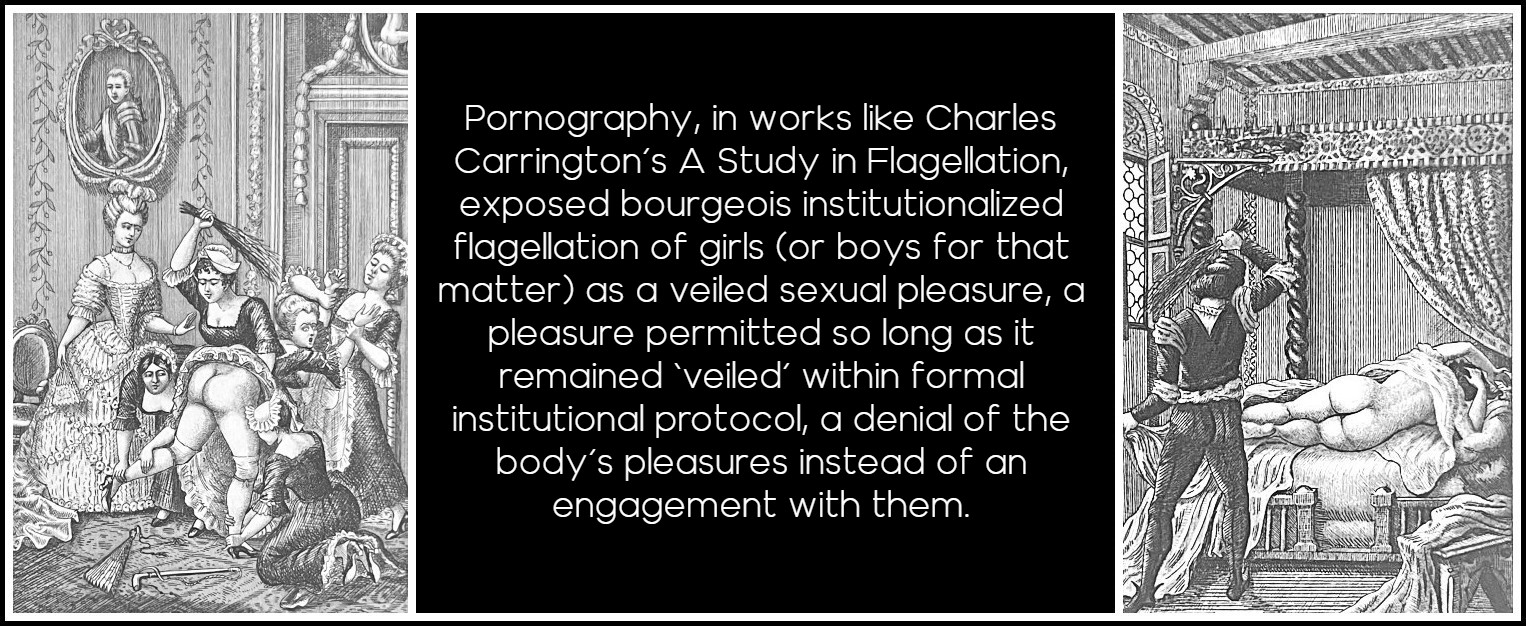

Bloom creates or passes on a form of pornography to each of the ladies (a book, a picture, his own pornographic descriptions) in the attempt to fulfill his own erotic imagination, which in turn has been formed by these very pornographic media. The text shows that Bloom’s sexuality is produced discursively or visually in the mass-produced sexual fantasies of pornography, the myriad of books and pictures produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. If commercial capitalism mass-produces a particularly idealized sexuality as seen in Gerty’s cosmetic longing, Art thou real, my ideal?, it is equally busy mass-producing the hard-core materialist fantasies of a Bloom who seeks sexual satisfaction in reproducing for himself (and imprinting onto others) such pornographically mediated fantasies. An interesting commentary on the mass-production of the sado-masochistic fantasy is suggested in Bloom’s stashed away press cutting from an English weekly periodical Modern Society, subject corporal chastisement in girls’ schools. The subject of wide public debate as well as pornographic novels and photographs, chastisement in girls’ schools and reformatories marked a provocative intersection between bourgeois high-cultural denial of the body and mass culture’s exploitation and subjugation of the body to its pleasures. Pornography, in works like Charles Carrington’s A Study in Flagellation (1901), exposed bourgeois institutionalized flagellation of girls (or boys for that matter) as a veiled sexual pleasure, a pleasure permitted so long as it remained ‘veiled’ within formal institutional protocol, a denial of the body’s pleasures instead of an engagement with them.

Flagellation de la Dame de Liancour & Vengeance du Chevalier | The Charles Carrington Collection, Paris Olympia Press: A Collectors Blog

ALLISON PEASE: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments