Winged Mare, Owl-Cat, Sphinx-Cat

LEONORA CARRINGTON, REMEDIOS VARO, LEONOR FINI: ANIMAL SYMBOLISM – PART 1

Georgiana M. M. Colvile

From Georgiana M. M. Colvile, ‘Beauty and/Is the Beast: Animal Symbology in the Work of Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Leonor Fini’ in Surrealism and Women,

edited by Mary Ann Caws, Rudolf Kuenzli & Gwen Raaberg (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1991) 159-170

Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Leonor Fini

I. INTRODUCTION

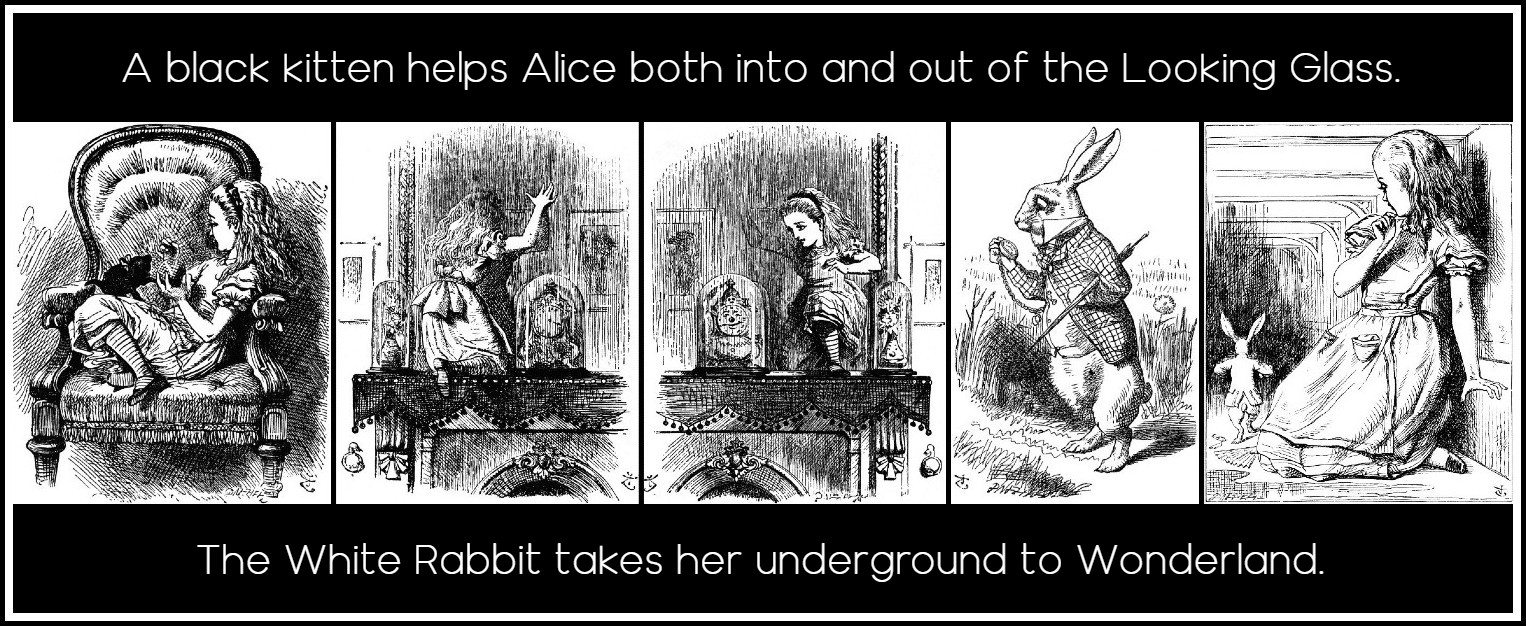

Iconographic representations of both familiar animals and fabulous beasts are as old as human history. The basic belief in a ‘woman and nature’ association can be traced back almost as far. Some feminists have objected to this cliché; others, like the painters I am about to discuss, have turned it to their advantage. Lewis Carroll’s Alice, who has fascinated Surrealists and feminists over the years, is led on her two oneiric journeys by animal guides: the White Rabbit takes her underground to Wonderland; the dream metamorphosis of a black kitten helps her both into and out of the Looking Glass. In these strange places, humans, ordinary animals and fantastic creatures interrelate quite naturally.

John Tenniel, Through the Looking Glass & Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

Tzvetan Todorov bases his definition of the fantastic on the hesitation and ambiguity which occur between reality and the inexplicable, much like the gap the Surrealists sought to bridge between everyday contingencies and secondary states, such as dream, fantasy, illusion, madness and death. To Todorov, any phenomenon which can eventually be rationalized is merely strange, like Freud’s ‘uncanny’ and the mechanisms of dream-work, whereas the utterly undefinable in terms of ‘real-world logic’ belongs to the category of the ‘marvelous’. To André Breton, ‘the marvelous is always beautiful, anything marvelous is beautiful, in fact only the marvelous is beautiful’. Breton and his friends included women in this pattern, conveniently putting them on a distant pedestal and maintaining them as inexplicable creatures like the Sphinx and the Chimaera. Xavière Gauthier, in Surréalisme et sexualité, was one of the first to expose the Surrealists’ inconsistency toward sexuality and their own ideology. She catalogues the ironic metamorphoses to which they subjected the female objects of their desire, including reconstitution of the lost androgyne, woman-as-nature, earth, flower, fruit, star, witch, voyante, and threatening beast.

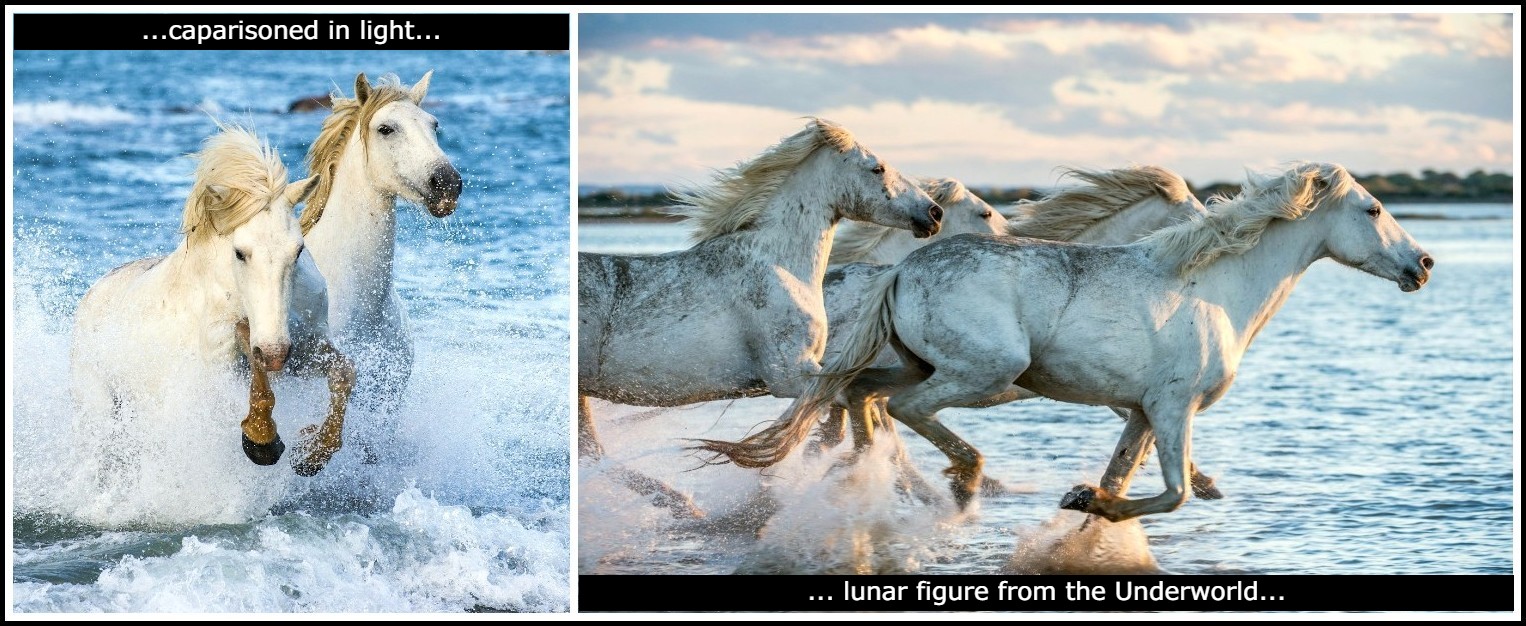

Photos: Danielle Suijkerbuijk, Unsplash

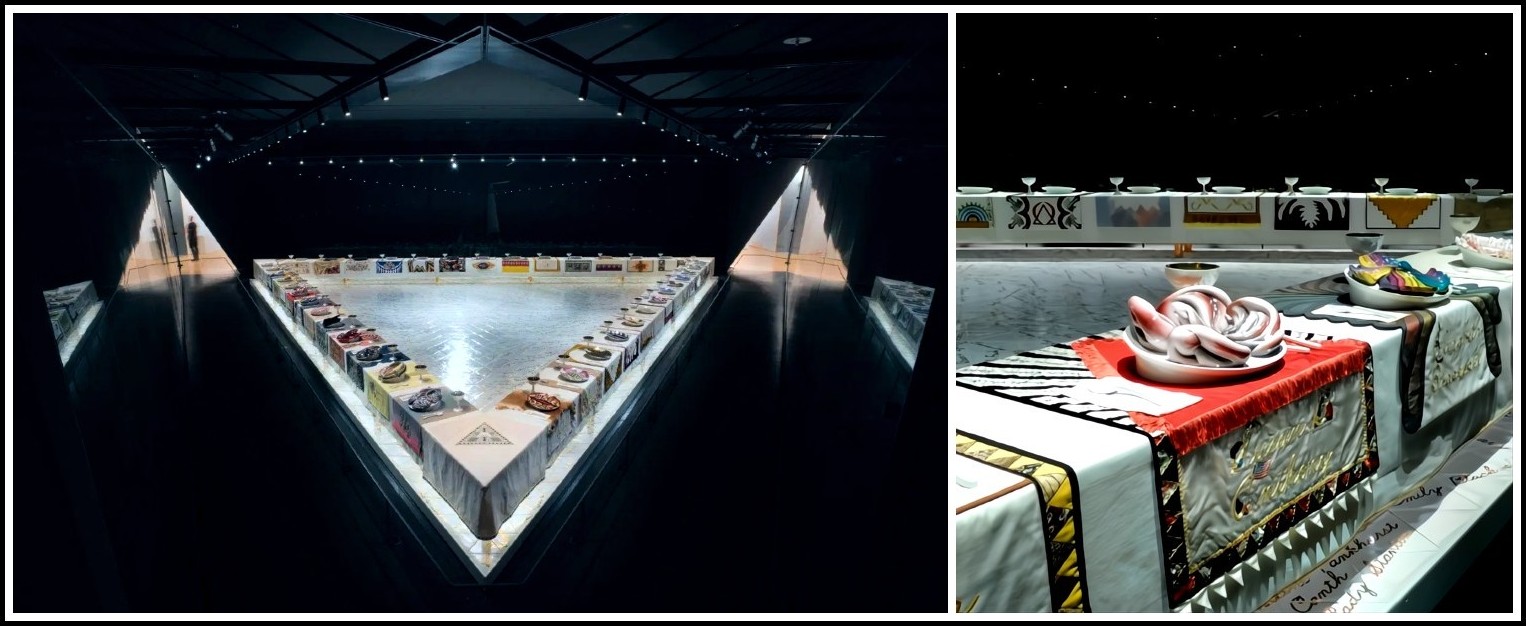

Except for the indomitable Leonor Fini, most women artists first became connected with the Surrealist movement as wives or companions of members of Breton’s circle or of other internationally recognized avant-garde artists. However quiet and subdued they may have appeared within the group, they continued to weave their own independence as artists, using all the material and freedom the Surrealist framework could provide them with. As Whitney Chadwick has pointed out, in recognizing her intuitive connection with the magic realm of existence that governed creation, Surrealism offered the woman artist a self-image that united her roles as woman and creator in a way that neither the concept of the femme-enfant nor that of the erotic muse could. Just as Judy Chicago chose ‘women’s work’ like embroidery and china painting to make a feminist statement in her 1979 exhibit The Dinner Party, women Surrealists made extensive use of their own beauty in self-portraits and explored the worlds of childhood and madness, where men tried to confine them, as passages to their true identity.

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974-79

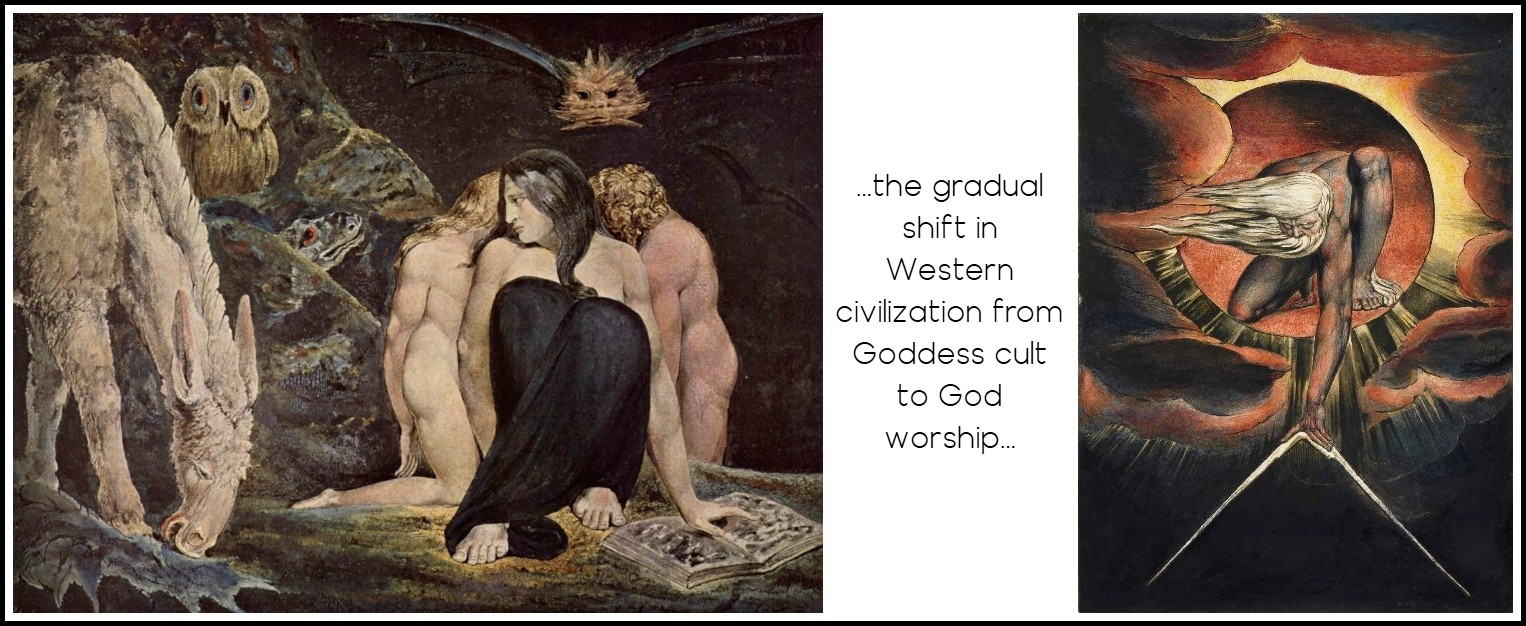

Most of these women’s animal imagery comes from dreams or myths. Indeed, animals appear frequently in dreams. Freud identifies small animals as genital symbols, wild beasts as representing passionate impulses, and beasts of prey or wild horses as substitutes for a dreaded father figure. Jung relates animals to unconscious manifestations of the ‘animus’ and ‘anima’ and man’s basic instinctual drives. In Genesis, Adam appropriates and dominates the animals by naming them, prefiguring his subsequent treatment of Eve. The alliance between Eve and the snake is a deformed version of the older matriarchal Celtic myth from the time when, as Robert Graves writes, ‘all totem societies in Ancient Europe were under the dominion of the Great Goddess, the Lady of the Wild Things’. According to Graves, the Goddess could undergo any number of animal metamorphoses—into, for example, a mare, she-bear, sow or hind. She mated yearly with her snake-son, killed him and burned the egg she had laid: he would be reborn each year from the ashes. Graves has traced the gradual shift in Western civilization from Goddess cult to God worship. Vestiges of the former often appear in animal form, like the Old Testament golden calf and the male preference for female or animal masks at carnivals.

WILLIAM BLAKE

The Night of Enitharmon’s Joy (Hecate), 1795 | The Ancient of Days, 1827

Links between women, children, animals, and various forms of magic are a constant in Western art. Borges comments on the legend that only virgins could approach and catch unicorns.

Domenichino, Virgin with a Unicorn, 1605 | French tapestry, The Lady with a Unicorn, 1500

Fabulous beasts, like Sphinxes, Chimaera, and Gorgons, tend either to be female or to symbolize male fear of female sexuality. In his study of monsters in Western art, Gilbert Lascault associates the artist’s creative anguish with the death drive and a terror of procreation, all of which find an outlet in vampiric representation. He looks to women to break that pattern: ‘It is only by retrieving the naïve power within themselves, that women can avoid the sterile, perverse pitfall of male sexuality, which is rooted in violence’.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Head of Medusa, 1618

In order to find herself, the Surrealist woman artist was not appropriating nature as divorced from culture, but retracing her steps back to matriarchy and the Goddess cult, to the pre-human world of animals, to the original confusion between man and animal species, to her own prelinguistic infancy and intimacy with the mother, to the nursery world of toys, pets, and animal fairy tales in which the father becomes the monster. Baudrillard insists on the perfectly ritual fascination emanated by animals, and equates it with female charm. He maintains that the attraction of animals lies not in their wildness but in ‘the feline, theatrical nostalgia for parade and ornament they arouse in us.’ Leonor Fini’s elaborate costumes and catlike attitudes come to mind. Baudrillard’s definition of the ‘paradoxical space, where the distinction between nature and culture is abolished in the concept of ornament and parade in which woman and animal alike are reflected’, points to a place from which women can create.

Photo: Mackenzie Taylor, Unsplash | Augustus John, The Marchesa Casati, 1919 (detail)

Each of the women artists I have chosen favors one specific animal, although others will appear in her work. Like the Mayan ‘Naguals’, these animals can be seen as personal totems, symbols of another world, alter egos and mirror images, or as a metamorphosis of the loved one. Hence Beauty and/is the Beast. Beauty in the fairy tale is a model daughter, who asks her father for no more than a rose (respect for her virginity). He steals the rose from the Beast’s garden. Beauty goes willingly to the Beast’s kingdom, first to save her father, then to save the Beast, who is dying without her. When she discovers she loves him and agrees to marry him, he turns into a handsome prince. According to Bettelheim, Beauty has normally crossed the Oedipal bridge from father to husband. She is able to love the Beast when sex (his bestial form) has ceased to threaten either her or her father. Jung sees the tale as illustrating a ‘process of awakening’ which instructs women on how to recognize their ‘true function of relatedness’ and the required feminine submissive response to the ‘animal man’. Another reading: Beauty’s father is poor, foolish, and steals other people’s flowers. His absence and mistakes lead her to discover a new enchanted realm, the Beast’s palace, where all her wishes come true and a magic mirror abolishes time and space. She returns to the imaginary world of childhood, where her companion resembles the fuzzy toys and furry pets she once cherished. She falls in love with the Beast, not the prince. The prince is her father’s fantasy, a mirror image of his younger self, who will enable him to possess her vicariously. This leads us to Leonora Carrington, who rewrote ‘Beauty and the Beast’ at least twice.

Alain Gauthier, La Belle et la Bête, 1988

II. LEONORA CARRINGTON

At the beginning of her career as an artist and writer, Leonora Carrington chose the horse as her personal totem. In two early texts, the short story ‘The Oval Lady’ and the play Pénélope, Carrington’s adolescent Beauty (Lucrecia/Penelope) is in love with her hobby-horse (all at once toy, animal and fantastic Beast) Tartarus (‘Tartar’ in the original French versions). Tartar returns the girl’s love. Her father threatens to burn the hobby horse to stop her from ‘playing’ with him/it. Penelope escapes by turning into a horse herself and flying off like Pegasus with her uncanny lover. As Gloria Orenstein has explained: Tartar, derived from Tartarus, the Greek underworld, links another Celtic white horse divinity, Epona, to the realm of the otherworld. Shortened to Tartar, a double anagram of ART, it indicates that through ART we can attain divine and occult knowledge. ART is also the archaic ‘thou’ form of the verb ‘to be’ and the girl could thus address her inanimate horse-lover as he comes alive, and/or her newly found identity: ‘ART! ART!’ In addition, Leonora Carrington had practiced mirror-writing since childhood, and ‘TARTAR’ in the mirror would read ‘RAT RAT’. An appropriate insult for the murderous father, the epithet probably refers back to Apollo’s other name, Smintherus, meaning ‘rat.’ For the Greeks and Romans, the rat was a noxious chthonian beast, propagator of the plague. Such animals hardly appear in the matriarchal Celtic mythology Carrington has always adopted, and she seems to have banished them, like the father, from her work. In dream symbolism, rats represent gnawing sexual desires: the father’s problem, as in ‘Beauty and the Beast.’

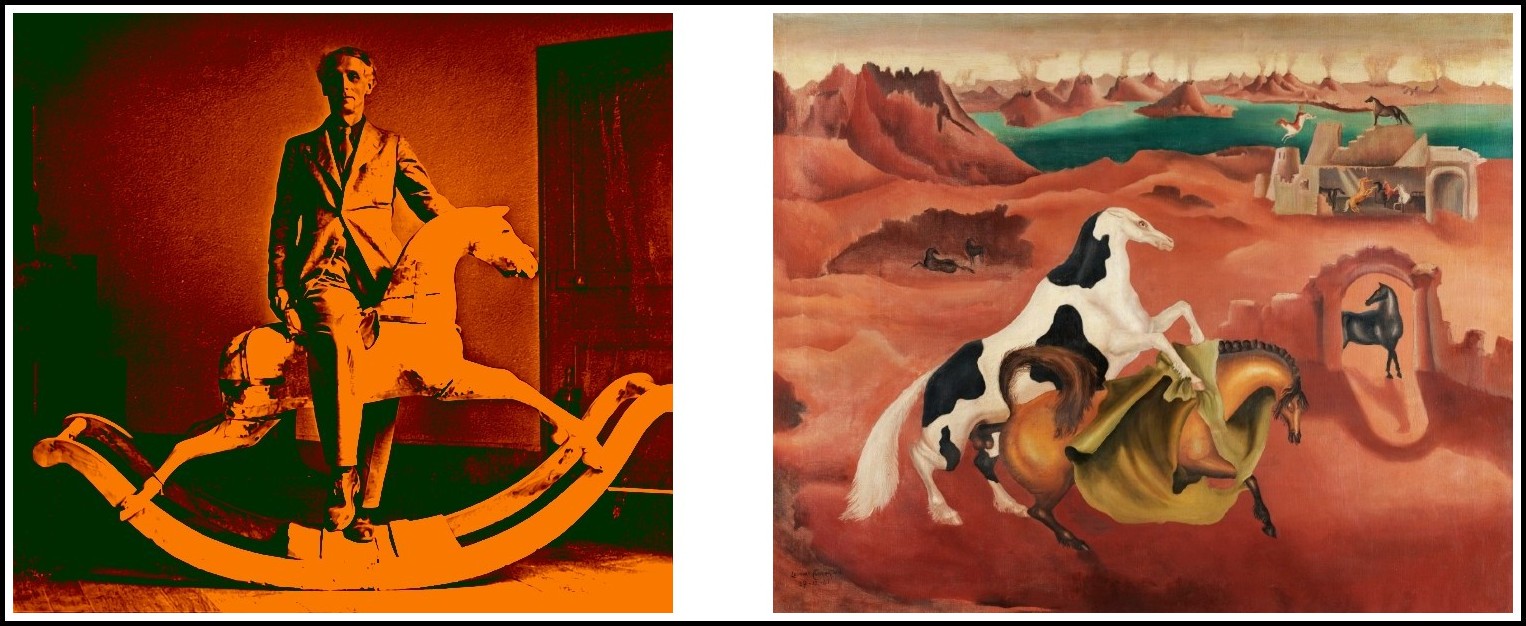

Leonora Carrington, The Horses of Lord Candlestick, 1938

Like her symbolic animal carrier, Leonora Carrington was almost constantly on the move from 1926 to 1942, when she finally settled in Mexico. Her bestiary increased as she went through the various passages of her life, from her Celtic ancestry to the land of the Mayas. Her later paintings and writing are marked by the multiplicity of her experience, including the hybrid creatures of her imagination, part human, part beast, anchored in Todorov’s uncertain space of the fantastic. In Carrington’s early work, the horse remains the dominant animal. From the beginning, she has sought to abolish the difference between humans and other animals, even in love, as she has said, In l’amour-passion, the loved one is the other who gives the key. Now the question is: Who can the loved one be? It can be a man or a horse or another woman. The connection with the Earth Goddess, who was able to take almost any animal form, seems obvious.

Photos: Getty Images for Unsplash

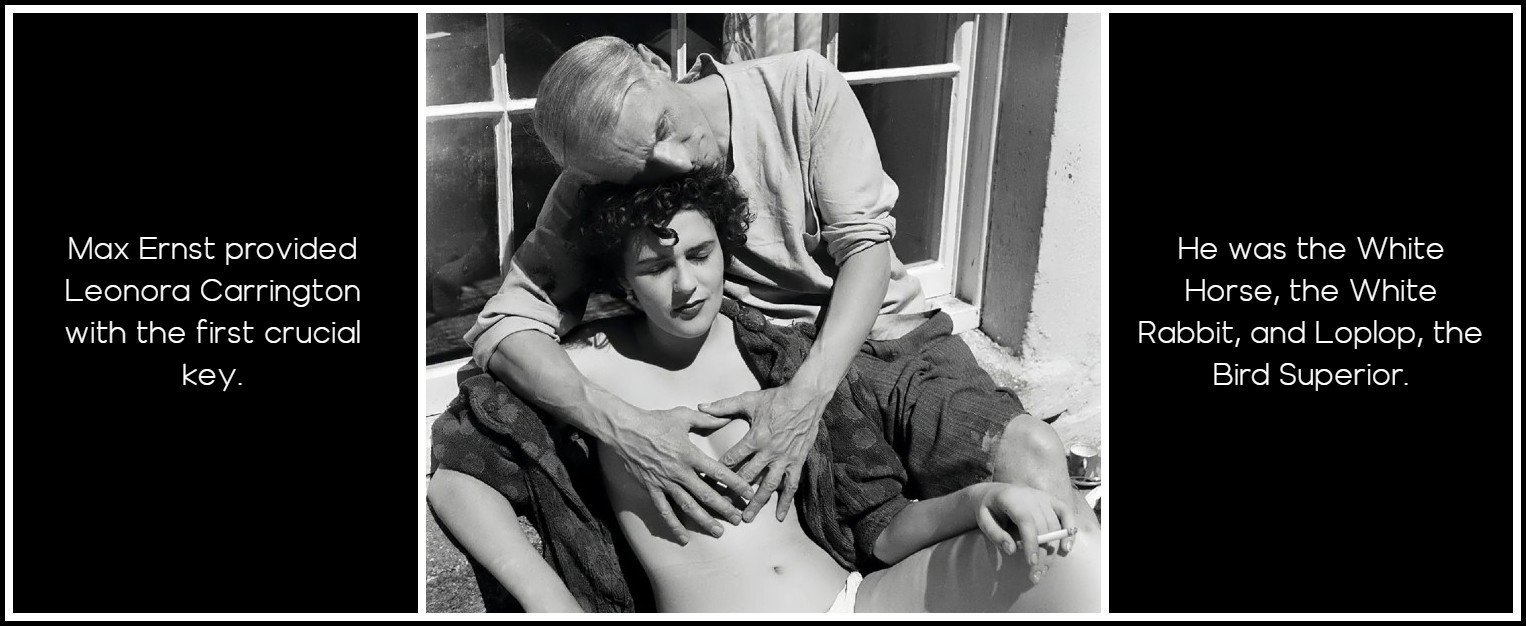

Man, bird and horse, Max Ernst provided Carrington with the first crucial key. The already white-haired Ernst was the White Horse who helped her escape from her stuffy upper-class British environment, and the White Rabbit who led her to the Underground of the Surrealist group in Paris. Ernst had already created his own totem and legend: Loplop, the Bird Superior, reborn after ‘the death of Max Ernst in 1914’.

Leonora Carrington & Max Ernst, 1937 | Photo: Lee Miller

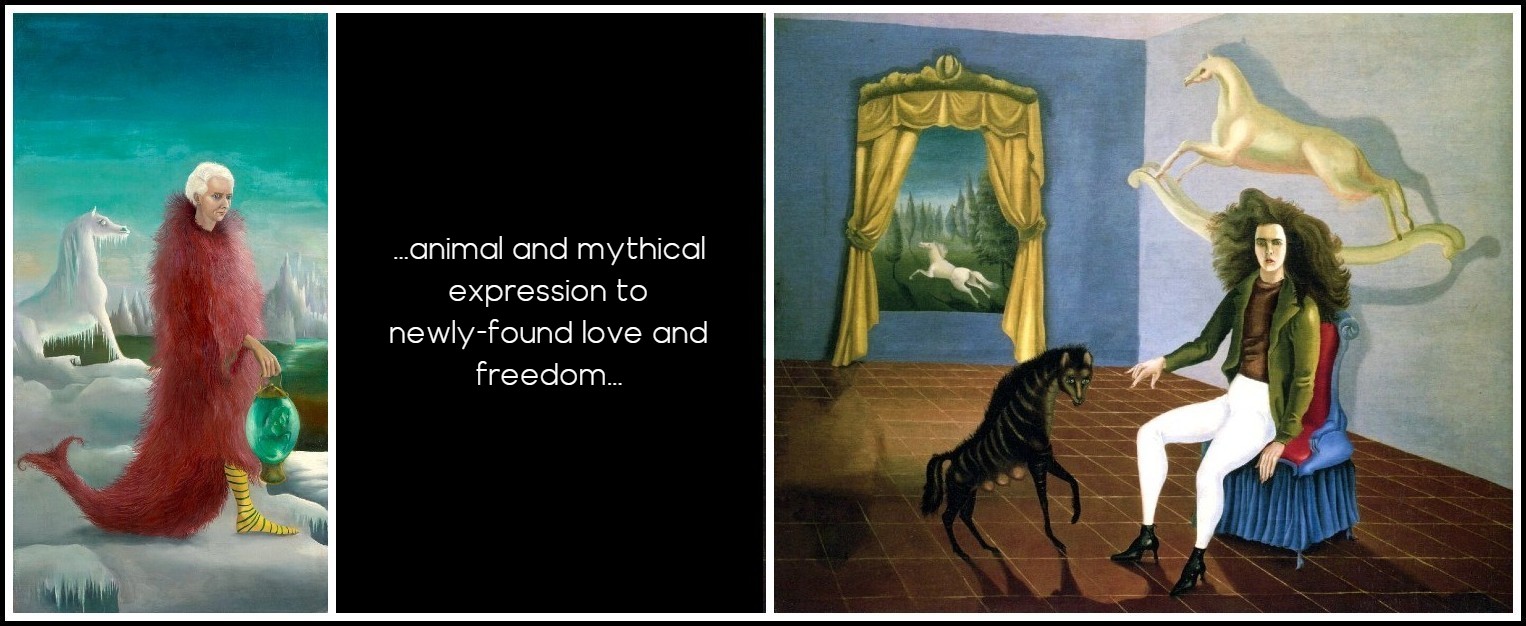

For Carrington, he was also a horse. They both appear in equine form in her twin portraits Self-Portrait and Portrait of Max Ernst. The former gives animal and mythical expression to newly-found love and freedom.

LEONORA CARRINGTON

Portrait of Max Ernst, 1939 | Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse), 1937-38

This first important picture contains the basics of the magical code Carrington was to develop in her later work.

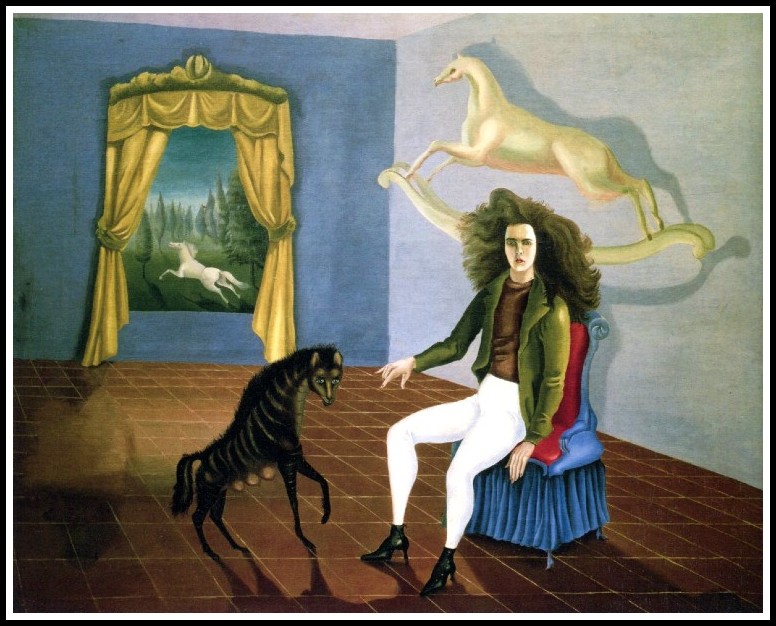

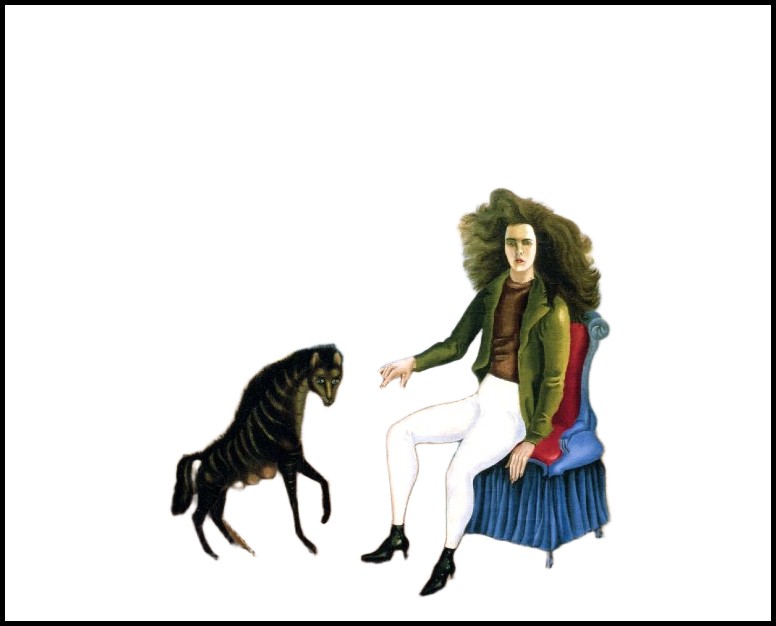

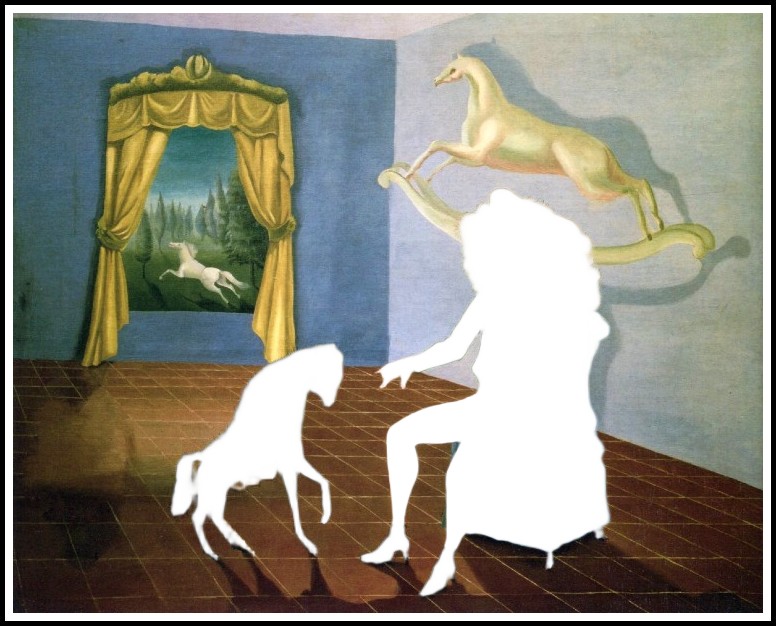

Leonora Carrington, Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse), 1937-38

The horses are intertextually related to the written works Pénélope and ‘The Oval Lady,’ and the hyena reappears in the short story, ‘The Debutante’. In Self-Portrait the seated woman’s mane-like hair finds an echo in the horse’s mane and the hyena’s color. The black female hyena coming toward the seated Leonora from the left has its feet on the earth-brown floor and matches the woman’s black shoes. The white rocking horse (Tartar), on the right, is positioned in the air, above her, his rocker touching her mane, his white color matching her riding breeches, apparently galloping toward the window in the background. The color of the window wall and of the sky seen through it is blue, the color of imagination and the other side of the mirror: time and space have been abolished outside the room, where the hobby horse has become a real steed speeding into the trees. The natural green landscape reflects the color of the woman’s jacket; she is also both outside and in. Green is the color of the plant world, of regeneration, life’s awakening, strength and hope; also of acidity and of Persephone’s pomegranate seeds, Hades’ gift of male temptation.

Leonora Carrington, Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse), 1937-38

Green is the color of Carrington’s mother’s native Ireland, her earliest source for the Celtic mythology so essential to her work. The yellow-gold curtains are a sign of renewal and of the earth’s fertility, as well as of the knowledge of celestial light conveyed by the alchemists’ precious metal. The red and blue chair Carrington is sitting on represents an alliance between the male and female principles and at the same time the competitive struggle between heaven and earth. The three colors of the alchemists and of the Moon Goddess are already manifested here: the alchemist Abraham Juif represents three riders on three lions, black for gold in maceration, red for its inner ferment, white for the conquest of death. The New Moon is the White Goddess of birth and growth, the Full Moon the Red Goddess of love and battle, and the Old Moon the Black Goddess of Death. The two animals, the white horse and the black hyena, represent the goddess’s duality—positive versus negative, life versus death, Earth Mother versus devouring monster—so inherent to human nature and to man’s fear of woman. Self-Portrait contains all the components of a young woman’s initiation to the world. The hyena never reappears in Carrington’s later work. The animal’s presence, like its devouring role in ‘The Debutante,’ adds an element of malicious humor to the picture: the little girl has grown up and the nursery is undergoing a perverse transformation. A disruptive animal, the hyena was already despised as ‘a dirty brute’ for its apparent androgyny in an early medieval bestiary.

Leonora Carrington, Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse), 1937-38

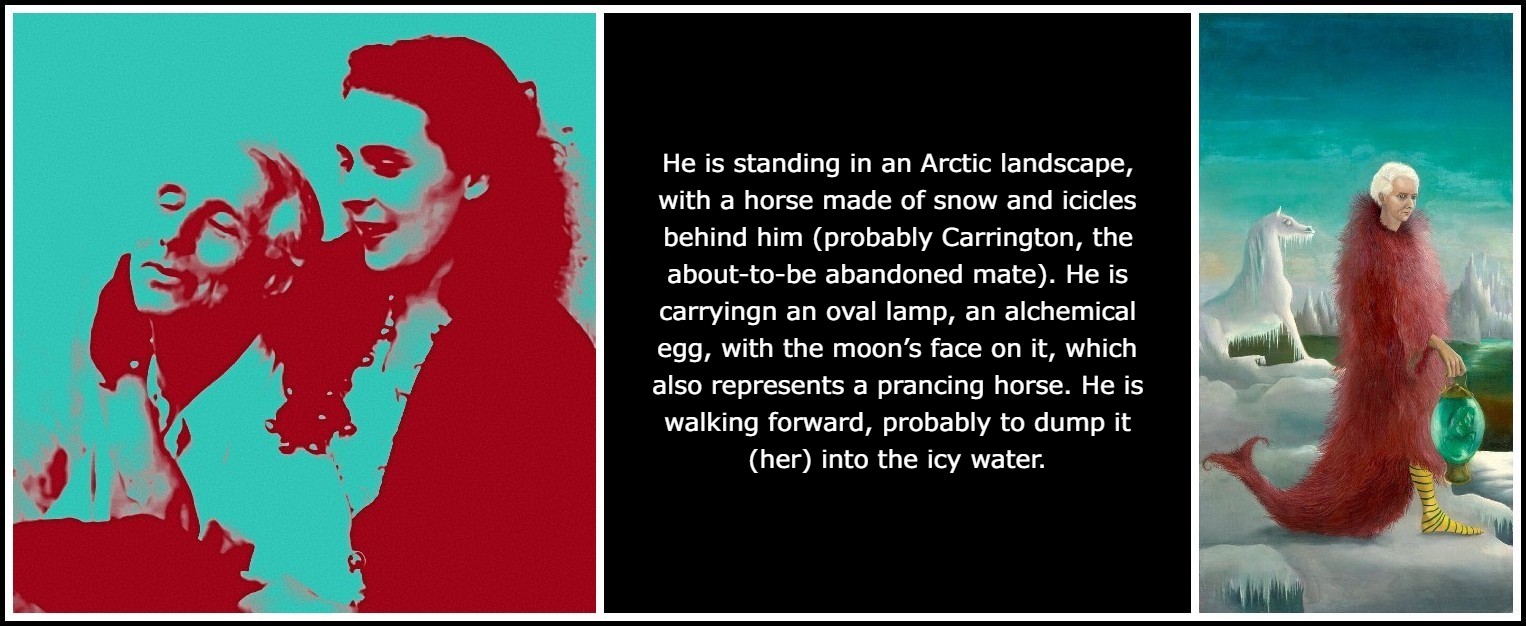

The Portrait of Max Ernst is situated on the other side of the window. Max, with a pinched stubborn expression, appears as a hybrid creature: his own human head, hand and foot (the yellow-and-black striped sock evoking a stinging insect) emerge from an aggressively male red fur garment in the shape of a seahorse. He is standing in a desolate blue-and-white Arctic landscape, with a horse made of snow and icicles behind him (probably Carrington, the abandoned or about-to-be abandoned mate). He is nonchalantly carrying at arm’s length an oval green lamp, an alchemical egg, with the moon’s face on it, which also represents a prancing horse. He is walking forward, probably to dump it (her) into the icy water. He seems to be leaving her,1 just as Uncle Ubriaco abandons Little Francis in Carrington’s tragicomic story ‘Histoire du petit Francis,’ which can be read as a barely disguised account of the couple’s years in St. Martin d’Ardèche, where they had moved from Paris in 1937. The war brutally dislodged and separated them in 1940.

1 – Note by RJ: Joanna Moorhead, in her biography The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington, convincingly demonstrates the opposite, namely that it was Leonora who left Max: The problem for the still only twenty-four-year-old Leonora was that next to Max she was almost invisible. As a girlfriend who was also a practitioner, she was almost unique among the Surrealist women: avant-garde the movement may have liked to think it was, but when it came to women the Surrealists’ views and expectations were depressingly narrow and conventional. She now felt very strongly that if she went back to him, her life as an artist would be for ever overshadowed by his work, by his story and by his fame. So it was in New York that she made her decision to finally leave him. Joanna Moorhead, The Surreal Life of Leonora Carrington (London: Virago, 2017, p. 138)

Max Ernst & Leonora Carrington, 1937 (Photo: Lee Miller) | Leonora Carrington, Portrait of Max Ernst, 1939

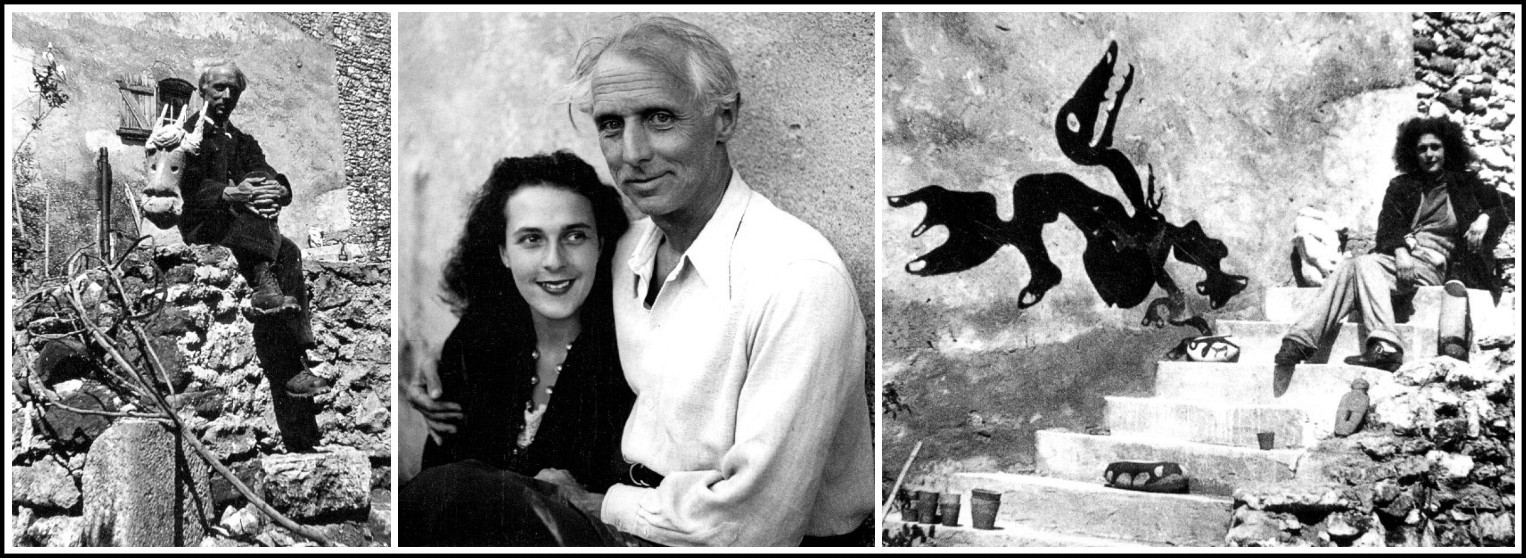

Whitney Chadwick’s description of their extraordinary dwelling place in St. Martin d’Ardèche posits it as the obvious model for Carrington’s first published story, ‘The House of Fear’, illustrated by Max Ernst: Carrington’s life with Ernst strengthened both their associations with nature. At St. Martin d’Ardèche they renovated a group of ruined buildings, covering the walls with cement casts of birds and mythical animals. Carrington’s paintings of the period reveal a growing vocabulary of magical animals, at the center of which lies the image of the white horse.

Leonora Carrington & Max Ernst, St. Martin d’Ardèche, 1939 | Photo: Lee Miller

In 1940, Ernst painted Leonora in the Morning Light, in which Carrington’s head and shoulders, framed by her dark mane, are seen emerging from a jungle of fantastic flora and fauna, from which she remains inextricable, a vision of the Earth Goddess. The horse Ernst is again the helpful animal guide in the text ‘The House of Fear.’ He wrote a little introductory story, ‘Loplop Presents the Bride of the Wind,’ in which she reads her tale to a group of fascinated animals. (Carrington refers to her Orphic power over animals at the end of En-Bas, her lucid account of her nervous breakdown in 1940, following Ernst’s internment in a concentration camp. Her sensitized state gave her a strange insight, still manifest in her painting.)

Max Ernst, Leonora in the Morning Light, 1940

Carrington replied in 1942 with the text ‘The Bird Superior, Max Ernst,’ illustrated with her portrait of him. Concerning the appellation ‘Bride of the Wind’, the White Goddess, according to Robert Graves, was in charge of the winds, one of which was the answer to a riddle, just as ‘man’ was the answer Oedipus correctly gave the Sphinx. Only pigs and goats (sacred to the Goddess) could see the wind, and mares could conceive merely by turning their hindquarters to the wind. This equine myth was transmitted to the Greeks, who personified the North Wind as Boreas, the sire of twelve wondrous colts. These legends posit the wind as a pre-patriarchal male, giving his Bride an original matriarchal context. In another early picture, Horses, Carrington uses the same colors as in Self-Portrait, but here the noble animals have the world to themselves; no Yahoos or other creatures are to be seen in the reddish brown landscape, resembling the decor of a Western. The foreground shows a closeup of a black-and-white stallion and a golden mare happily copulating, a blanket loosely wrapped about her neck. Other horses of various hues are scattered in the background, some inside of or atop a building. In the distance a mirage-like lake hints at the unreality of this prehuman paradise.

Max Ernst, Paris 1938 | Leonora Carrington, Horses, 1941

Carrington’s later painting, after her arrival in Mexico in 1942, becomes increasingly rich and hermetic. She has evolved from more personal themes to a pictorial cosmology, the key to which is her underlying feminism. Her paintings are invitations to an alternative world of harmony, where humans, animals, plants and inanimate objects are on an equal footing, just as they all speak the same language in her stories and plays. Fabulous hybrid creatures abound, such as the Chimaera of Who Art Thou, White Face? and the butterfly-people of Lepidopteros.

LEONORA CARRINGTON

Who Art Thou, White Face? 1959 | Lepidopteros, 1969

In her quest for woman’s freedom and wholeness, Carrington uses her own experience, her accumulated knowledge of Celtic and Mayan myths (she studied with the Chiapas Indians before completing her 1963 mural El mundo mágico de las Mayas)…

Leonora Carrington, El mundo mágico de los Mayas, 1964

…alchemy, the Tarot, and the teachings of Gurdjieff and Carlos Castaneda, among others.

LEONORA CARRINGTON – TAROT CARDS

Sun (XIX) | Wheel of Fortune (X) | Star (XVII)

Her symbology and color wheel have no doubt been influenced by the Irish Book of Ballymote, which divides the year into a system of letters, numbers and colors, and by the even more complex Aztec calendar. In the latter, days were regarded as animate beings and individually represented by deities corresponding to numbers, animals, plants, elements, planets, death, etc.—in fact all the essential components of the life cycle.

Piedra del Sol (‘Aztec Calendar’), c. 1515

Both sides of the paradoxical eating theme as related to the Goddess-provider of good crops and natural foods, on the one hand, and devourer of her own young (an attribute of two of her animal forms—the sow and the cat— on the other, are amply represented in Carrington’s fiction. People enjoy good meals in The Hearing Trumpet and in ‘Jemima et le loup,’ for example, but violence and cannibalism color ‘The White Rabbits,’ ‘The Debutante,’ and ‘The Sisters.’ Yet in Carrington’s paintings meals seem to consist uniquely of fruit, herbs and vegetables, the Goddess’s peaceful gifts. In Hunt Breakfast, a table has been set in a forest clearing, surrounded at a distance by live game, deer, and wild boar (two of the goddess’s main forms), while the meal, like the Lepidopteros’, is composed only of fruit. Two ‘huntsmen’ are arriving with a gift of live birds. The hostess has a butterfly’s head, perhaps in reference to the Mexican Zapotec butterfly god symbolizing rebirth. The message is clear: the butterfly goddess has transformed the hunting ritual into peace and harmony between men and animals.

LEONORA CARRINGTON

Hunt Breakfast, 1956 | Lepidopteros, 1969

Alchemy has been defined by Arturo Schwarz as an all-male, misogynous, celibate activity, reducing the still and the reconstituted androgyne to the alchemist’s onanistic fantasy. Carrington, Varo, and Fini invented their own alchemy, seeking to create the gold of a fulfilling woman’s world. In their work, the recurring egg is a fertility symbol. Carrington’s fantastic creatures resemble both the winged dragons and bird-serpents of alchemists like Abraham Juif and Nicolas Valois, and the Mayan plumed serpent Wind and Corn God Quetzalcoatl. She pointedly titled one of her medieval-looking paintings The Chrysopeia of Mary the Jewess, combining Mary the Christian goddess figure with a feminized (Abraham) le Juif.

Joseph Wright of Derby, The Alchemist, 1771 | Leonora Carrington, The Chrysopeia of Mary the Jewess, 1964 | Francois-Marius Granet, The Alchemist, 1805

The White Goddess of the Celts and the Aztec Coatlicue are both Earth and Moon Goddess. Carrington portrayed her in these two functions in two separate pictures, one titled The Ancestor and the other The God Mother. The first seems to represent the nocturnal Moon Goddess. Cloaked and hooded in white, against a misty Irish green background, she has the appearance of a ghost. The white of passage and the green of regeneration and hope situate her between both worlds. Green was also the color of the north and of royalty to the Mayas. Moreover, she is standing at the crossroads of the four cardinal points, each of which is guarded by a little lemur, symbol of the lost continent of Lemuria. They are white like her, and her jet black left eye matches theirs. Her other eye (a red rose) and the green cabbage she is holding in her hands point to life. She is human, animal, and vegetable. The celestial vault behind her and the fading moon in the upper right-hand corner suggest that dawn is near, but the picture remains obscure and mysterious.

Leonora Carrington, The Ancestor, 1968

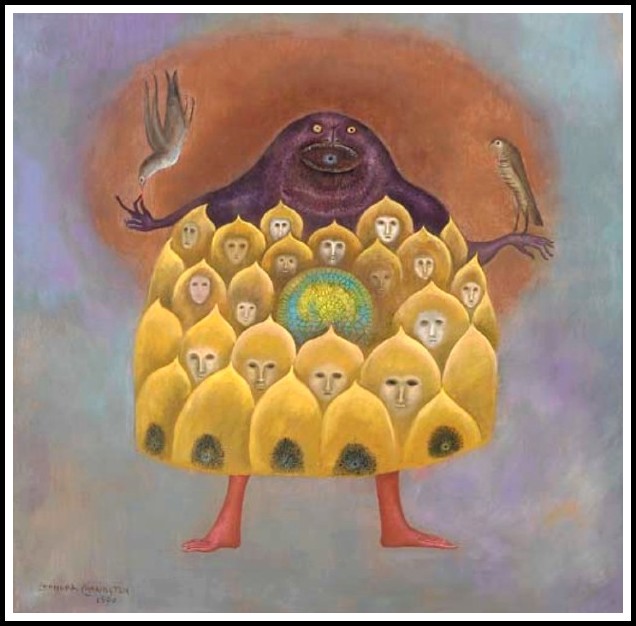

The God Mother is bursting with animal vitality. This fat fertility figure, whose head and shoulders could belong to either an owl or a she-bear, is holding out her arms as perches to two birds: the dove of peace and the wise owl. Her large body is made up of the golden-haired heads of countless women, with a round celestial fire in her center. Her top is haloed with red, matching her red feet. The background creates a bluish white diaphanous light. Her shape is that of the Grail or the half-egg of the alchemical still. The dark matter of her top is being turned into gold and light. Her vase-body is upside down, like the values put forward by Carrington: the Goddess has devoured the women to unite them and their strength; the gold color of alchemy, the sun, and corn have been feminized.

Leonora Carrington, The God Mother, 1970

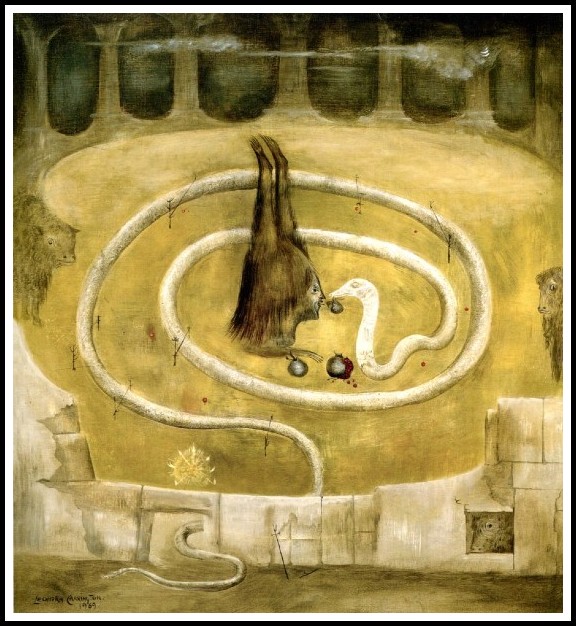

Carrington never discards the male principle, and between The Ancestor and The Godmother she painted Forbidden Fruit. A small, disproportionate woman is doing a headstand and rubbing noses with a long snake, twice curled around her in egg-shaped coils. They are sharing fruit, more like pomegranates than apples, and are guarded by sacred animals, two oxen and a lemur. The title seems ironical, as the goddess’s pleasurable mating rite eclipses the guilt-ridden Eve story. The picture is probably a humorous reference to Graves’s description of Osiris’s ‘fifty-yard-long phallus looped around the world like a serpent’.

Leonora Carrington, Forbidden Fruit, 1969

Carrington’s animals are often the guardians of the goddess or a substitute female figure. In The Return of Boadicea, the Celtic warrior queen is represented with a double bird and horse head. Her fiery chariot is being drawn and protectively surrounded by a team of fierce and sturdy half-horse, half-ox hybrids. The sheep and goats of Round Dance form a ring around a compact circle of women dancers. Here the central female principle unites Christian sheep and pre-Christian goats. With the secret magic of her art, Carrington is forever trying to create a wondrous creature in whom feminine, childlike, animal, and plant qualities would harmoniously merge. She/it appears at the beginning of her story ‘Quand ils passaient’: It was quite a sight: fifty black cats, fifty yellow cats and her. Whether or not she was really human, was impossible to determine. Her very smell made it seem doubtful. She exuded a blend of spices, wild game, stables and fur-like herbs.

Leonora Carrington, The Return of Boadicea, 1969

CONTINUED IN PART 2 (SEE ‘RELATED POSTS’ BELOW)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2026 | All rights reserved

Comments