Winged Mare, Owl-Cat, Sphinx-Cat

LEONORA CARRINGTON, REMEDIOS VARO, LEONOR FINI: ANIMAL SYMBOLISM – PART 2

Georgiana M. M. Colvile

From Georgiana M. M. Colvile, ‘Beauty and/Is the Beast: Animal Symbology in the Work of Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Leonor Fini’ in Surrealism and Women,

edited by Mary Ann Caws, Rudolf Kuenzli & Gwen Raaberg (Cambridge MA: The MIT Press, 1991) 170-179

THIS IS PART 2 – READ PART 1 FIRST

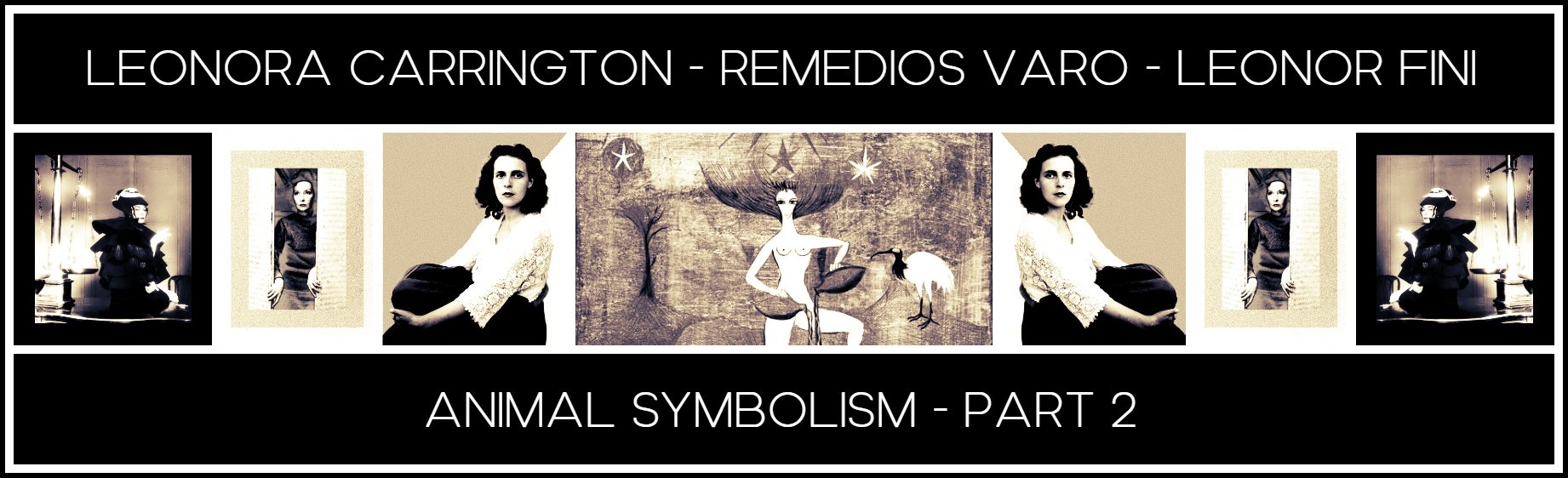

Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Leonor Fini

III. REMEDIOS VARO

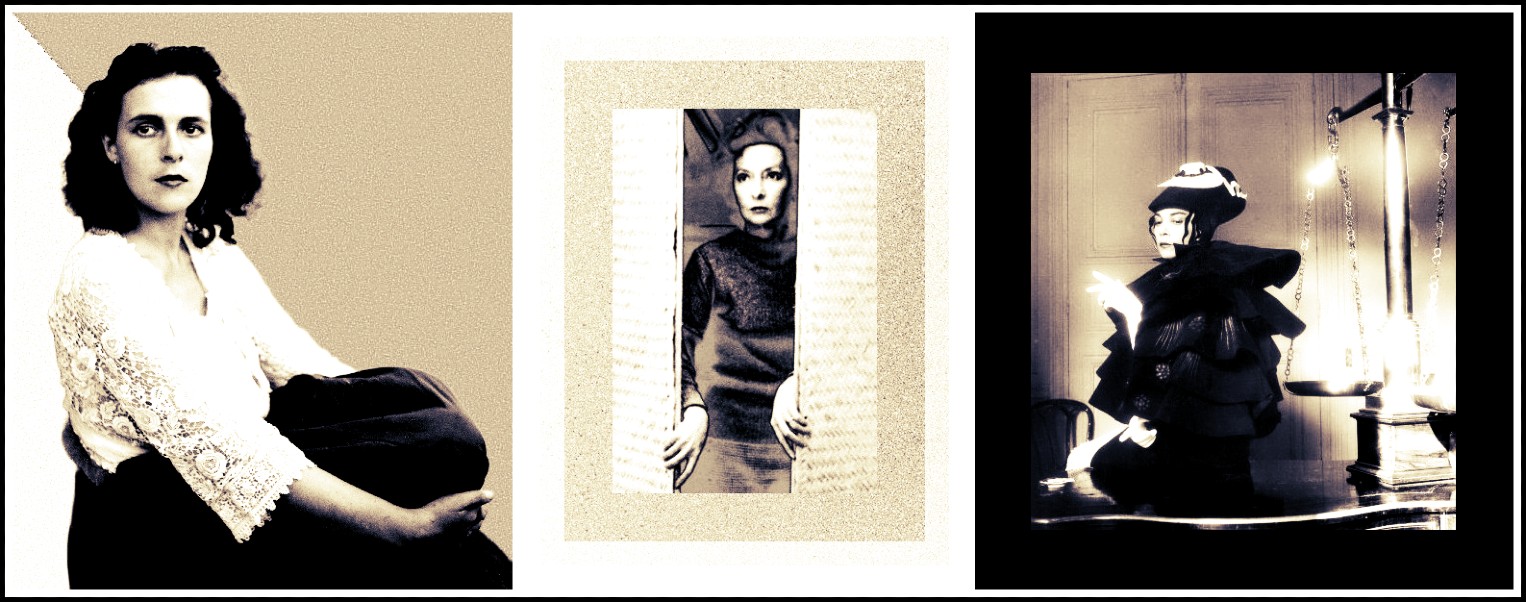

Varo’s exquisite draftsmanship and scientific precision place her technique somewhere between Leonardo and Magritte. Like Carrington, Varo projected another world and was fascinated by the magic arts. Her transformational process through painting is, however, a different one. Indeed, whereas Carrington used her art to create a potential metamorphosis of the world according to the female and animal principle of the Goddess, Varo’s alchemy consisted in transforming her own inner world of nightmarish visions and closing-in contingencies into art. The two women enjoyed a close friendship, shared each other’s dreams, studied the hermetic arts and belonged to a Gurdjieff group together. Varo’s wild, wandering youth resembles Carrington’s: she escaped from a stifling family life in Madrid to the avant-garde circles of Barcelona. There she met French Surrealist poet Benjamin Péret, followed him to Paris, and frequented Breton’s group. The war took the couple to Mexico, where Varo settled for the rest of her life. She produced the main body of her work there from the early 1950s to her premature death in 1963.

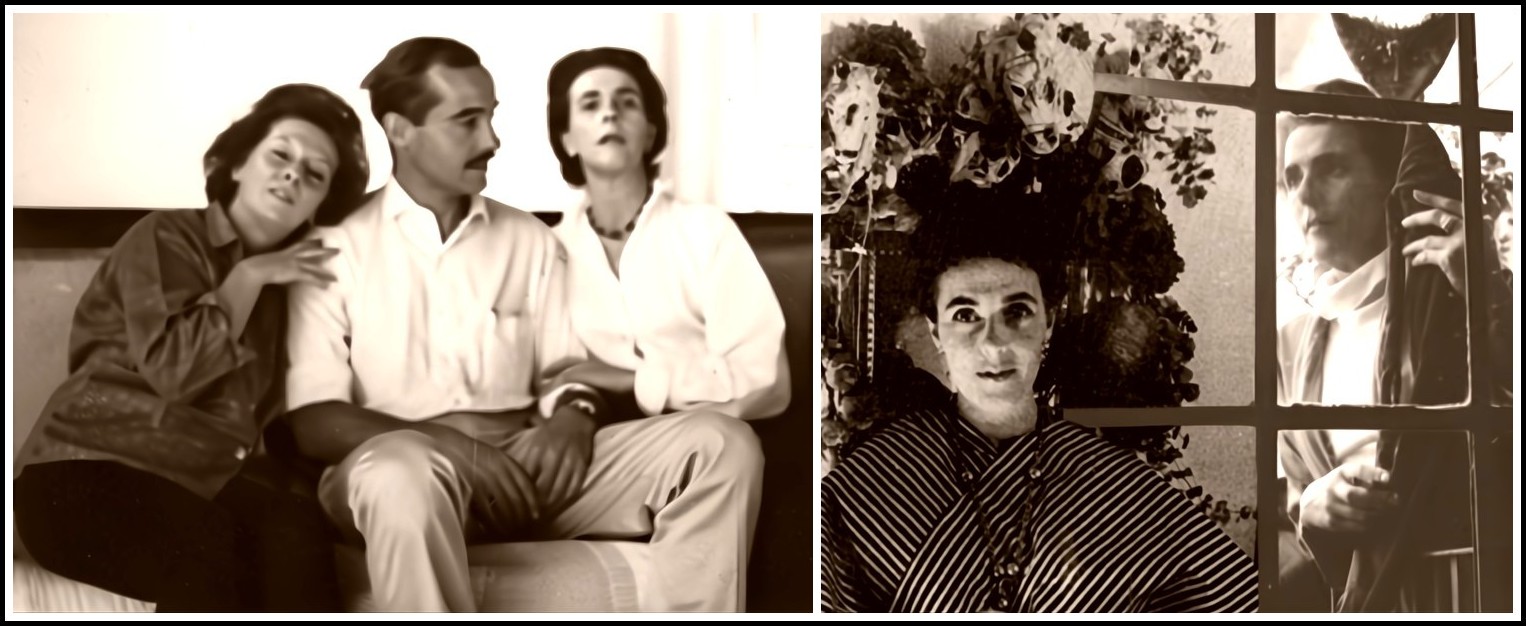

Remedios Varo & Leonora Carrington, 1950s [The man is a ‘Mr. Shepherd’.]

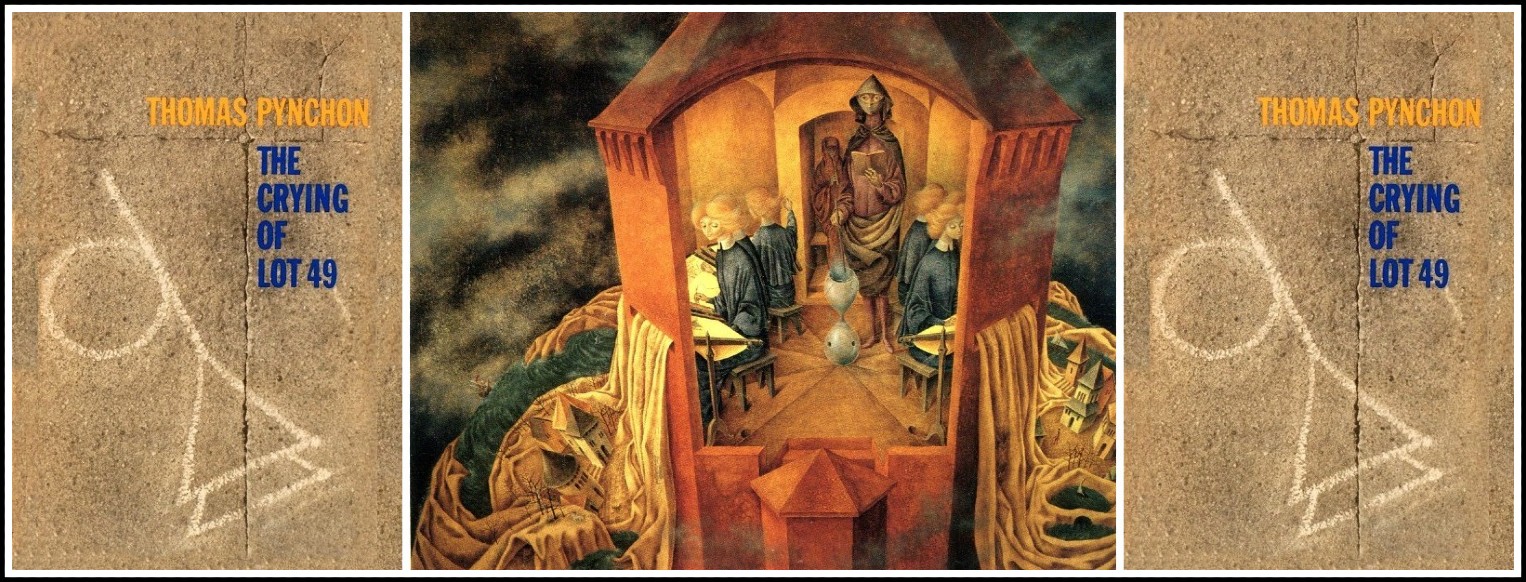

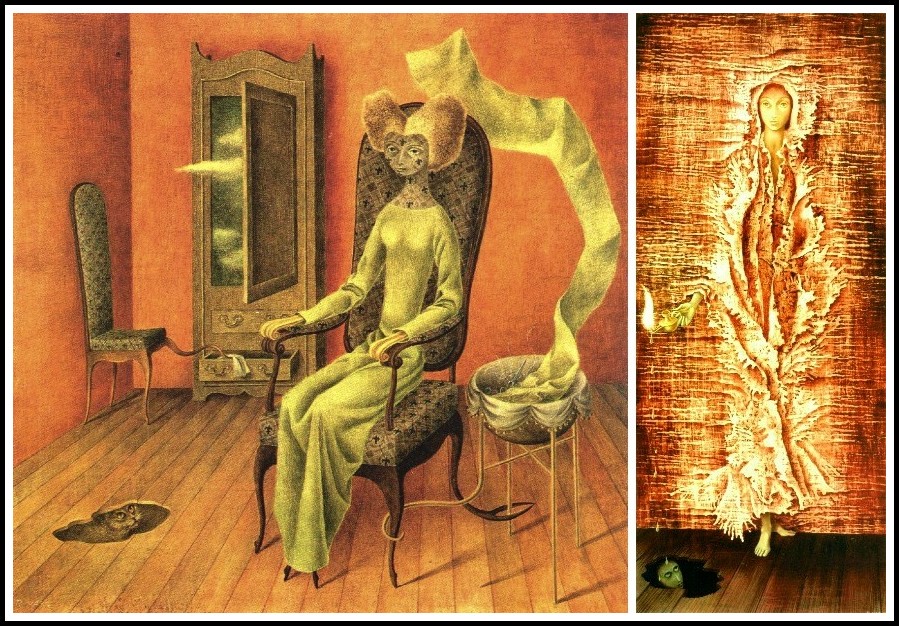

In his novel The Crying of Lot 49, Thomas Pynchon’s heroine Oedipa Maas gazes at the center panel of Remedios Varo’s triptych, Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle, recognizes her own Rapunzel pattern, and weeps. On the one hand, Varo’s picture of maidens imprisoned in a tower, weaving a world they cannot reach or see with threads emerging from an alchemist’s still, reflects the predicament of Pynchon’s Everywoman heroine; on the other, the latter’s first name, Oedipa, perfectly suits Varo’s omnipresent specular woman protagonist, described as follows by Janet Kaplan: Most of Varo’s personages bear the delicate heart-shaped face with large almond eyes, long sharp nose and thick mane of lively hair that marked the artist’s own appearance. The personae she created serve as self-portraits, transmuted through fantasy. Oedipa’s Sphinx remains invisible, the riddle purloined, and the only answer is to go on painting.

Remedios Varo, Embroidering Earth’s Mantle, 1961 | Thomas Pynchon, The Crying of Lot 49, book cover

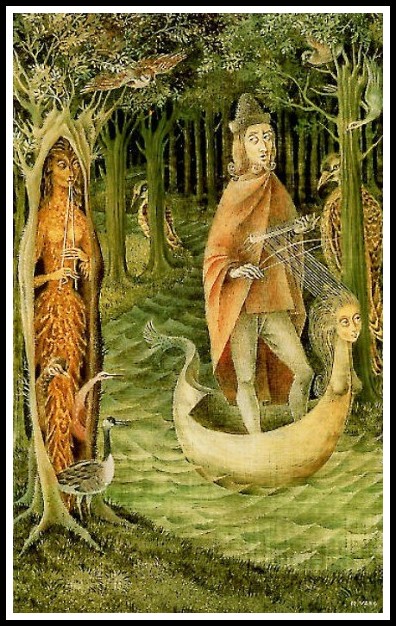

There is less marvelous in Varo’s universe than in Carrington’s, but an eerie viewpoint pervades it, similar to the one Todorov attributes to Kafka. The only fantastic object is (wo)man him/herself; the fantastic becomes the norm. To Varo, dreams, real and metaphorical voyages or quests, and the magic arts are interwoven with everyday ‘reality.’ Her canvas reflects the deforming mirror of the mind. Varo’s animal imagery is more limited and more intimate than Carrington’s. She often uses birds as symbols of escape or simply as decorative motifs, which is the case in Troubadour. Were it not for Varo’s characteristically uncanny way of making animate and inanimate matter merge and overlap, the wandering Orphic minstrel in his little boat, surrounded by attentive birds, might well be part of a sixteenth-century tapestry. Varo’s birds, which often accompany human figures, can also be Jungian symbols of transcendence.

Remedios Varo, Troubadour, 1959

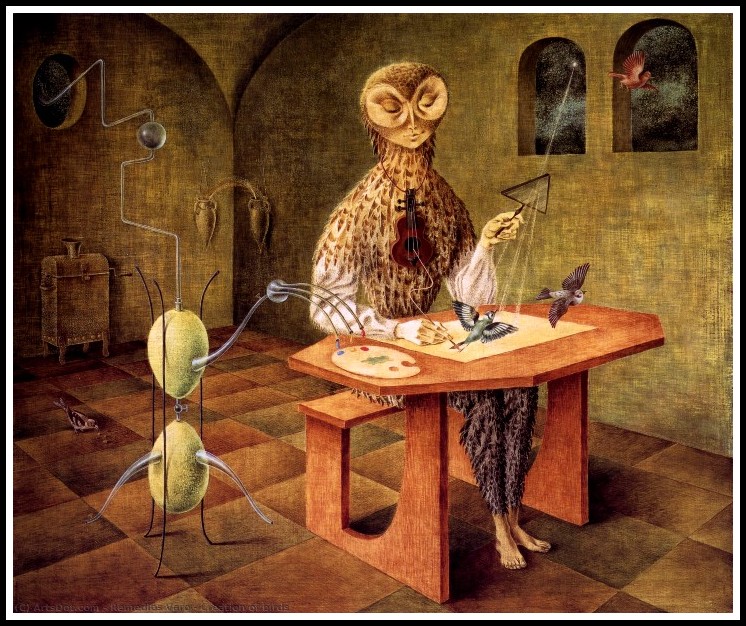

Two compatible nocturnal beasts stand out in Varo’s work: the owl and the cat. The owl is an ambivalent bird: for the Greeks it was a symbol of sadness, solitary retreat, and darkness. For the Egyptians it brought night, cold, and death. Like the cat, it accompanies sorcerers, brings thunder and lightning, and is also the positive bearer of wisdom and clairvoyance. Varo’s most famous and significant owl-picture is The Creation of the Birds. Here an androgynous owl figure, with human arms, feet and lower face, represents the artist as alchemist, painter and musician, with multiple sources of creative energy. The painter’s palette is connected to an alchemist’s still, and the artist is filtering the light of a star through a magnifying glass held in his/her left hand, while the right hand is drawing with an extended string of the musical instrument hanging from his/her neck. This serenely performed activity is producing live birds, one still attached to the sheet of paper in front of the creator, others flying off toward the window. The colors, as in most of Varo’s work, are those of alchemy: reddish-golden brown, black, and white. The wise owl represents Varo’s ideal vision of herself as an artist, and the birds her vicarious escape from the world through painting.

Remedios Varo, The Creation of the Birds, 1957

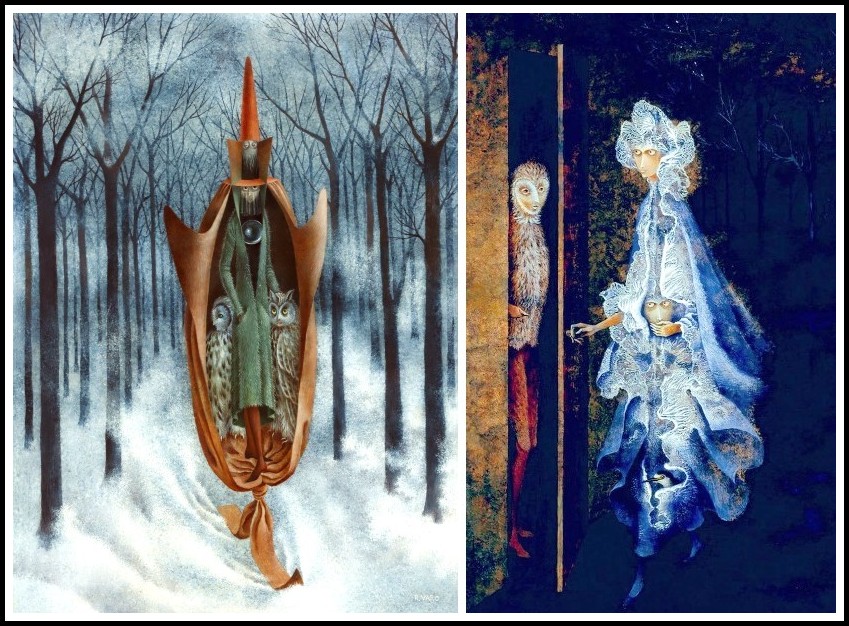

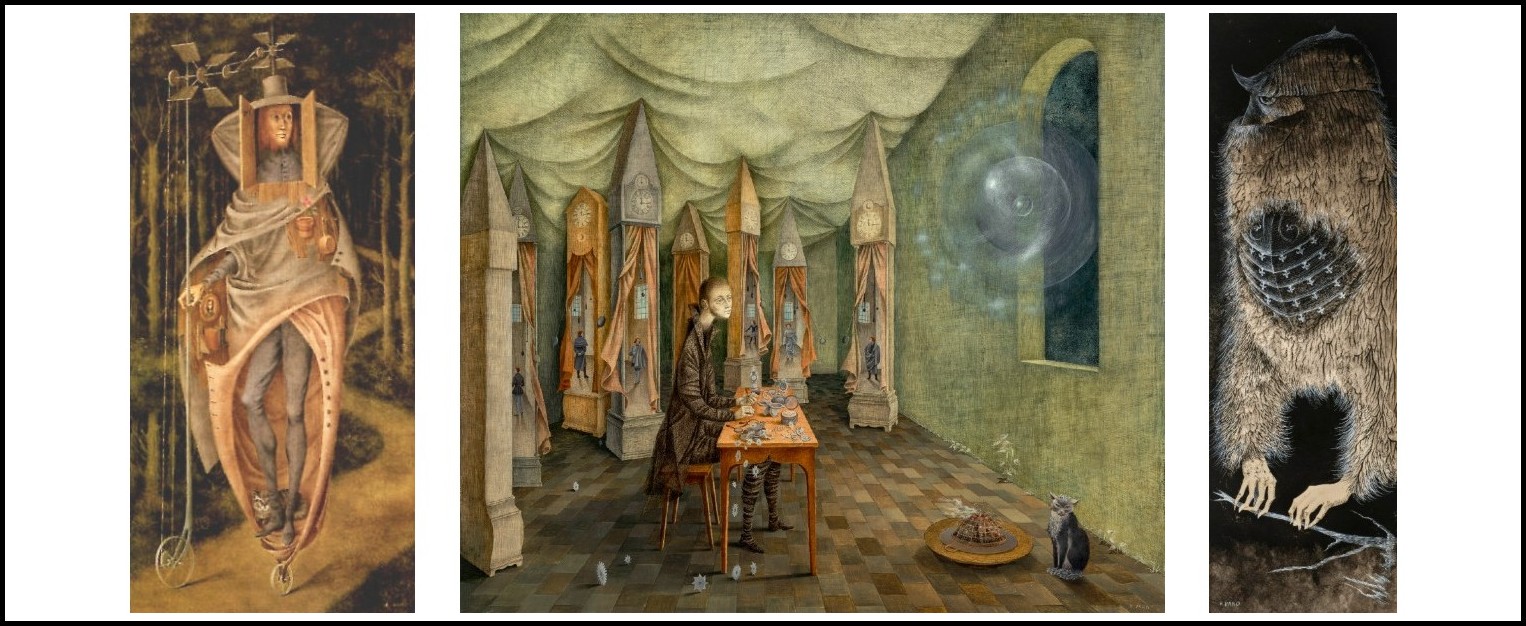

Several of Varo’s owls are more disquieting. Traveling Skier portrays a magician standing in a strange contraption with a knotted ribbon at the bottom serving as a ski; he is traveling through a landscape of snow and barren trees. His head beneath his conical hat is upside down, then doubled right-side-up below. A crystal ball gleams inside his coat, while two owls stand on either side of him. The woman at the center of The Encounter is cloaked in blue, the unreal color. A bird is peeping out from a flounce at the bottom of her leafy gossamer garment. The woman holds a replica of her face in one hand and is opening a door with the other. On the other side of the door, she encounters an owl, whose face is yet another version of her own, with a calmer expression, and whose human legs seem to belong to a very young man. Here Varo, looking like a femme fleur, meets her creative animus and/or potential lover. In Varo’s work, as in Fini’s, men and women are barely differentiated.

REMEDIOS VARO

Traveling Skier, 1960 | Encounter, 1962

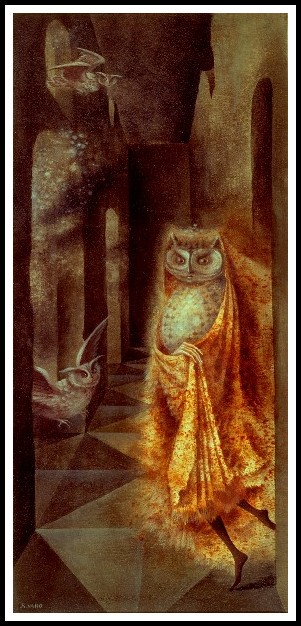

In Nocturnal Hunt, an owl is draped in gold cloth. Dark, stick-thin thin human legs protrude from the side of the cloak-like cloth. She is being observed from behind by two normal all-bird owls, flying about the Chirico-style building. The childlike humor in this picture also appears in several of the cat paintings. It seems to indicate animals’ ‘normality’ as opposed to the complex, fundamentally hybrid nature of human beings.

Remedios Varo, Nocturnal Hunt, 1958

The cat, like the owl, can signify clairvoyance, on the one hand, and darkness or death on the other This opposition is a constant in Varo’s world. The cat has a more paradoxical symbology than any other animal. In world mythology it ranges from goddess and sacred animal to evil omen and dangerous pest; it can also be a comical creature. Varo exploits this last aspect when she creates a green Fern-Cat, or an odd, somewhat reptilian cat constituted by falling dead leaves in Unexpected Visit. In such pictures, Varo appears to be making good-natured fun of her own creative process.

REMEDIOS VARO

The Fern Cat, 1957 | Unexpected Visit, 1958

In Varo’s world, the cat is the owl/artist’s ideal silent companion and usually a friendly creature. Such a cat looks on with anxious empathy in Mimesis as his mistress melts into her Magritte-like surroundings. He is looking up through a hole in the floorboards, exactly like the woman protagonist’s second face in Emerging Light. The cat can therefore be an alter ego.

REMEDIOS VARO

Mimesis, 1960 | Emerging Light, 1962

Small decorative cat companions or doubles often appear, like the one curled up at the feet of the Vagabond, in his strange little house on wheels, or the one imperturbably sitting under the window in Revelation (Clockmaker), while a ball of light comes whirling in. The oneiric subject of Enchanted Gentleman is actually disguised as a cat, probably indicating human envy of a cat’s simpler existence.

REMEDIOS VARO

Vagabond, 1957 | Revelation (Clockmaker), 1955 | Enchanted Gentleman, 1961

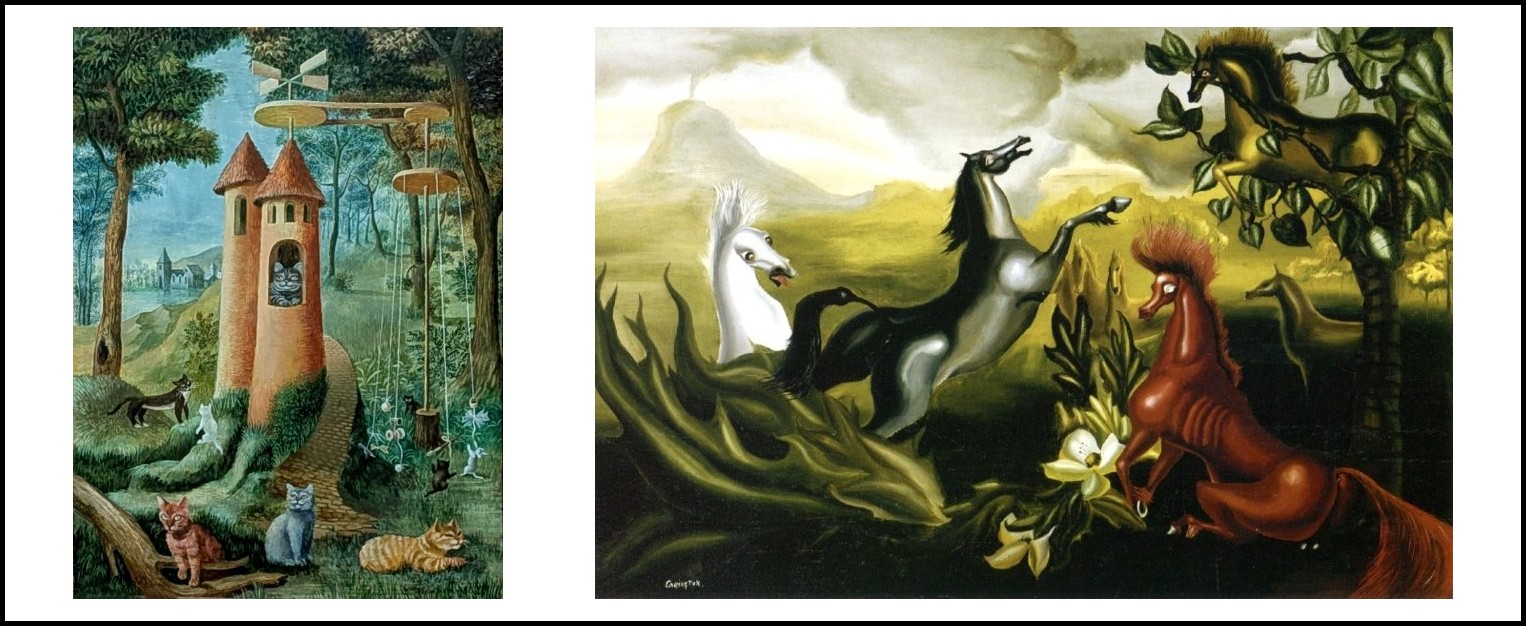

There are only two pictures in which cats are given more importance than the human figures. Cats’ Paradise is atypical of Varo. As in Carrington’s Horses, no humans are present: cats have taken over the world. Two towers (an obsessional motif with Varo) blend into the landscape: extensions of large tree-roots at the bottom, they are connected to a curious windmill at the top in an interesting nature-culture configuration. Various happy-looking cats are sitting, standing or lying about. The one gazing out of the tower window is no Rapunzel: he has the large square head of a tom, and we know he can climb down at will. The cats convey the ‘ritual fascination’ described by Baudrillard and a form of contentment unknown to Varo’s human characters.

Remedios Varo, Cats’ Paradise, 1955 | Leonora Carrington, Horses, 1938

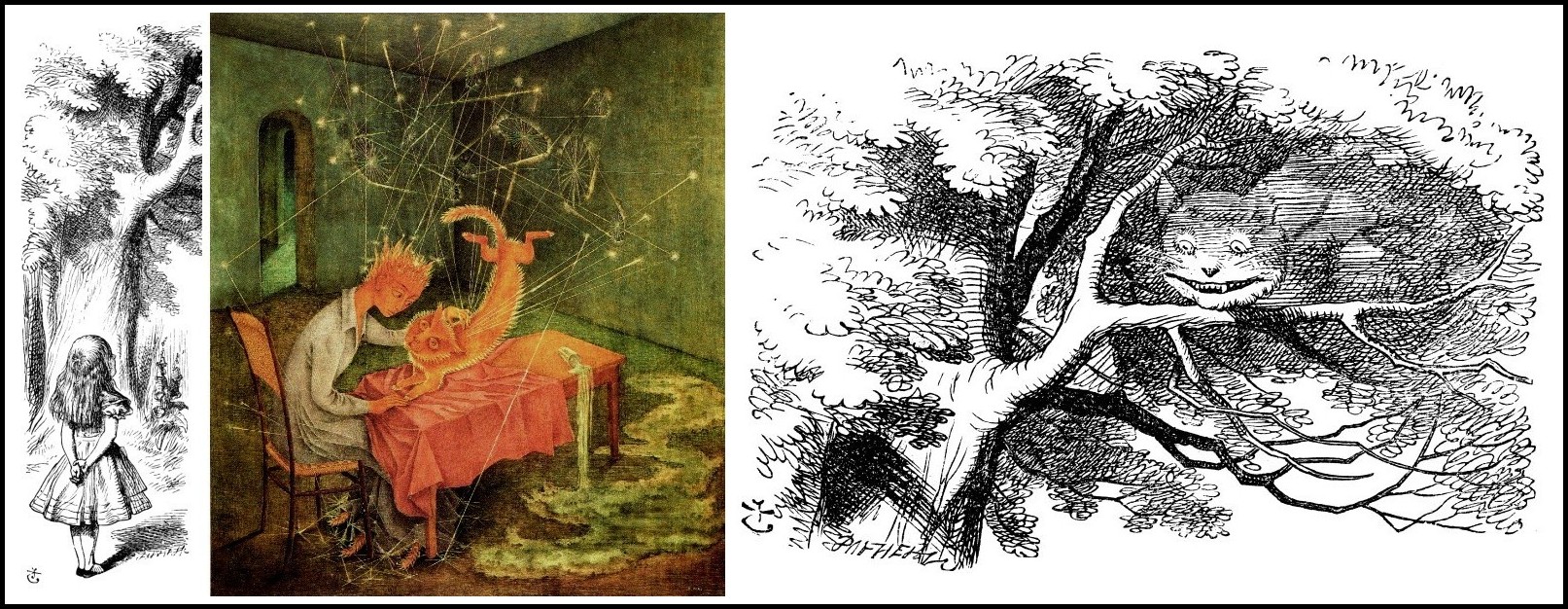

In Sympathy, the cat is caught in arrested movement, jumping onto a table and thus forming an alchemical egg-shaped figure with the woman seated there. The animal has rumpled the cloth and knocked over a glass. Woman and cat have similar bright, astonished eyes. She is meeting the cat’s rapturous gaze a little anxiously. Above them is a chaos of electric sparks, originating from the cat’s fur, the woman’s hair, and what looks like the tails of other cats, hidden under the table. The liquid from the glass, like Alice’s tears, has spread into a lake. The magic electricity refers to an exclusive complicity between the woman and the cat. To Varo’s solitary woman alchemist, the owl and the cat seem to provide a slightly reassuring sibling or specular presence which connects her to a receding reality. However, the comforting feline of Sympathy may also be paradoxically infecting the woman with madness, like Carroll’s Cheshire Cat, and hence generating anguish. Varo’s world is never truly serene.

John Tenniel, Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll | Remedios Varo, Sympathy, 1955

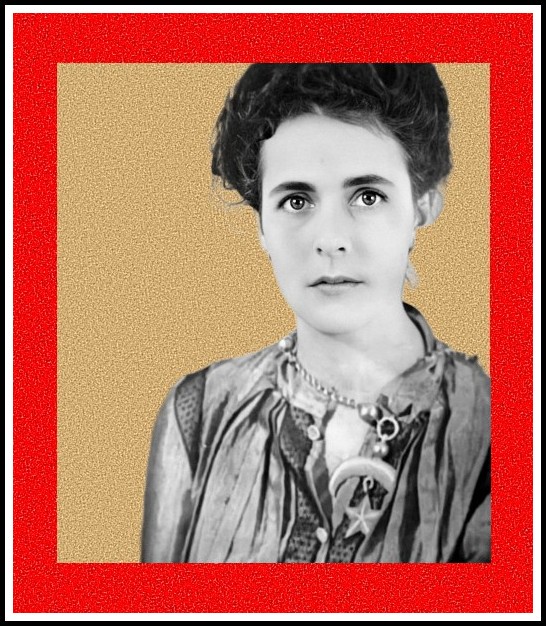

IV. LEONOR FINI

Like her name, Leonor Fini is definitively feline: her first name is an essential component of her varying mythical monster, the Sphinx, and closely related to her basic totem animal, the cat. Fini’s mother left Argentina and a tyrannical Neapolitan husband for her native Trieste when the child was a year old. Xavière Gauthier reports that Leonor was often disguised as a boy, to avoid being kidnapped by her father: androgyny began early. In 1937, at seventeen, Fini moved to Paris, the same year as both Carrington and Varo, but on her own. Fini rejected Breton’s authority and always refused to join his group, but became friends with several Surrealists and other rebels, including Ernst, Bataille and later Genet. She spent the summer of 1939 at St. Martin d’Ardèche, and painted a portrait of Carrington looking like both herself and Fini.

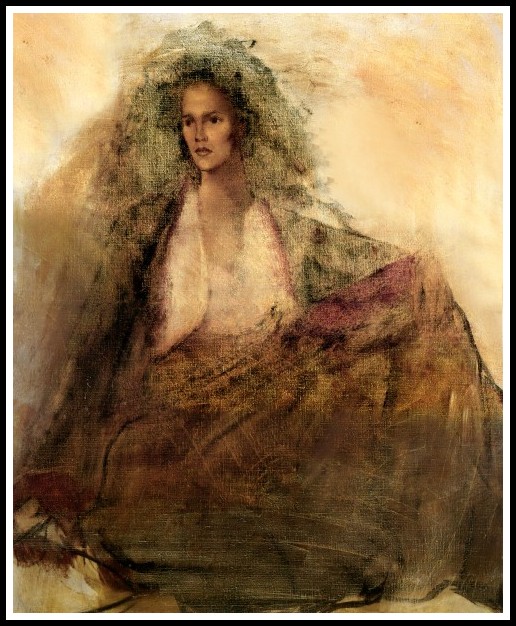

Leonor Fini, Portrait of Leonora Carrington, 1939

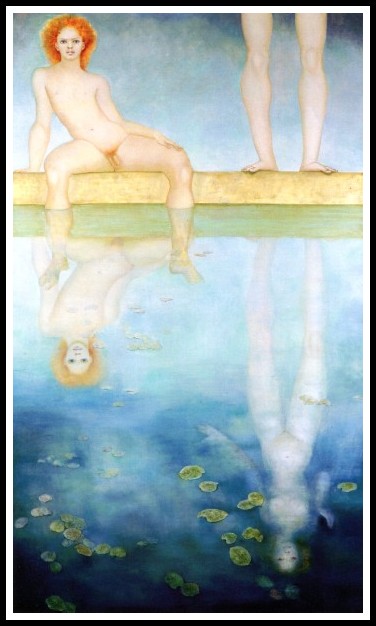

If Varo was Oedipa, Fini was Narcissa, forever contemplating her own image and reproducing it on canvas. She told Gauthier: The painting instinct draws a whole world out of me and that world is me. It is always an ambivalent and contradictory place where I find myself, and that can be an astonishing experience. Baudrillard recalls Pausanias’s version of the Narcissus myth: the young man, in mourning for his beloved twin sister, first mistook his image in a stream for hers and later used it as a consolation for her loss. In Fini’s Incomparable Narcissus. Narcissus is sitting, naked, with his feet in the water. Next to his own reflection stands another: a female identical twin, naked and upright. Outside the water, only her legs, which now look masculine, are visible. For Fini, as for Baudrillard, mirrors, like seduction, are always deceptive, and seduction is always self-seduction.

Leonor Fini, Incomparable Narcissus, 1971

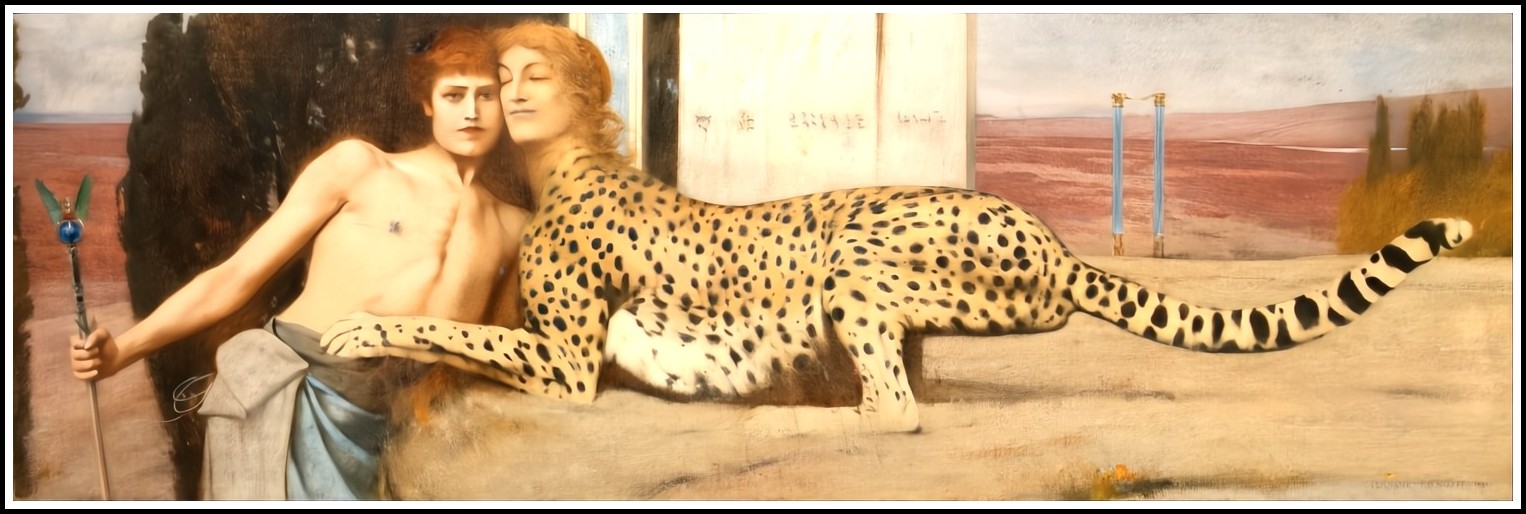

While Carrington and Varo were inspired by Renaissance artists and medieval alchemists, Fini acquired an early taste for Klimt, Munch, Beardsley, the Pre-Raphaelites, Art Nouveau and Art Deco. She descends from the Symbolists and Decadents. Fernand Khnopff’s L’art ou les caresses could be a symbolic portrait of her. It in fact represents Khnopff and his sister, cheek to cheek, she with a woman’s head and the body of a cheetah, he leaning his naked torso against her; they have almost identical faces, forming an androgynous ensemble. Together they constitute a perverse combination of the Greek Sphinx—a woman’s head and breasts, a bird’s wings and a lion’s body—and of the earlier Egyptian version, a reclining lion with a man’s head.

Fernand Khnopff, L’art ou les caresses, 1896

Fini’s numerous Sphinxes are always female, with the artist’s face. The Sphinx Amalburga has her hands around the neck of a delicate sleeping youth.

Leonor Fini, The Sphinx Amalburga, 1942

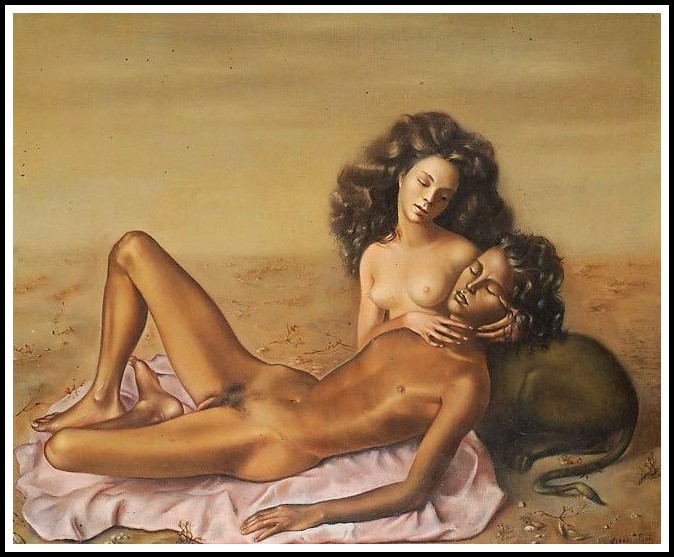

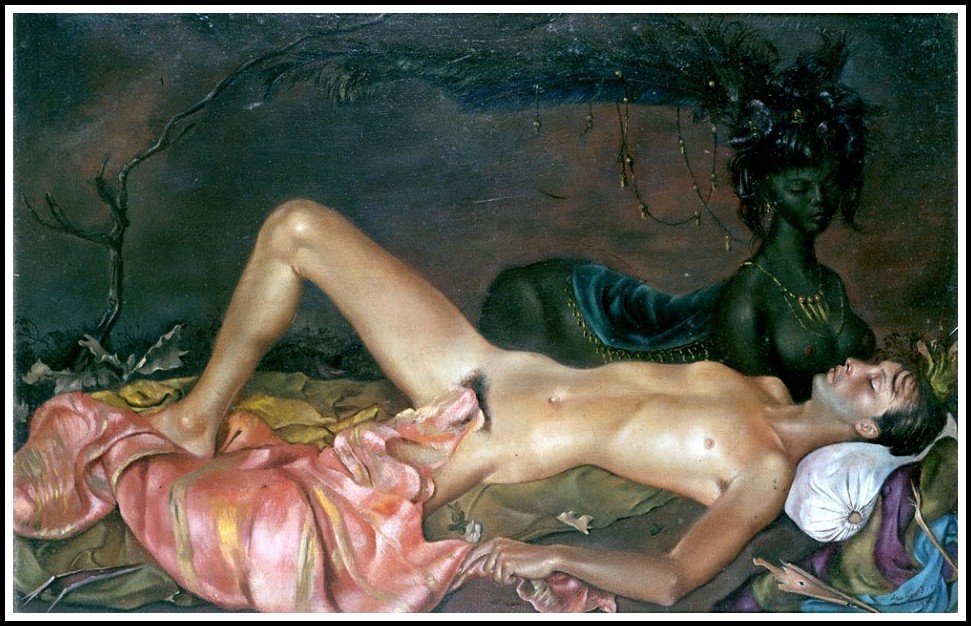

Chthonian Deity Watching Over the Slumber of a Young Man conveys the usual sexual ambivalence. Death always lurks in Fini’s work. She creates a surreal antinomy between the worlds of the living and the dead. For her, as for Cocteau’s Orpheus, stepping through the looking glass means falling in love with death. Her Sphinxes ominously guard the limits between masculine and feminine, human and animal, the world and the underworld.

Leonor Fini, Chthonian Deity Watching over the Sleep of a Young Man, 1946

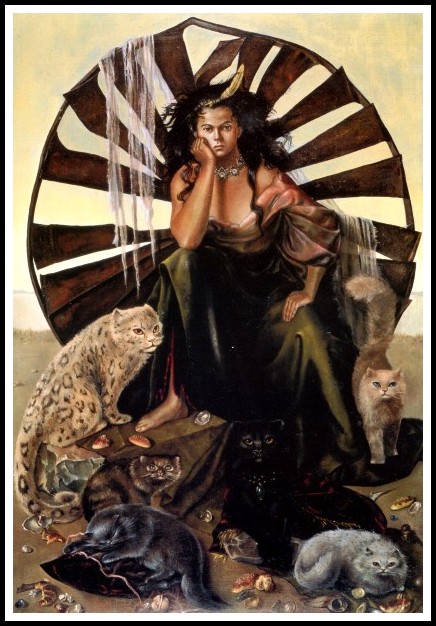

Cats take the place of Sphinxes in real life. No animal illustrates Baudrillard’s theory of ritual and ornament so well as the cat. Fini always portrays cats with a woman (herself), reflecting each other’s grace and dangerous beauty. The Ideal Life provides the finest example of Leonor as Cat-Goddess. Five Persian cats and an ocelot are gathered around her in a counterbalancing circle: a pale-coated cat to her left, the ocelot to her right, the black witch’s cat in the center and the others in front. All but one of the animals and the woman are staring straight at the spectator with cold, hard eyes.

Leonor Fini, The Ideal Life, 1950

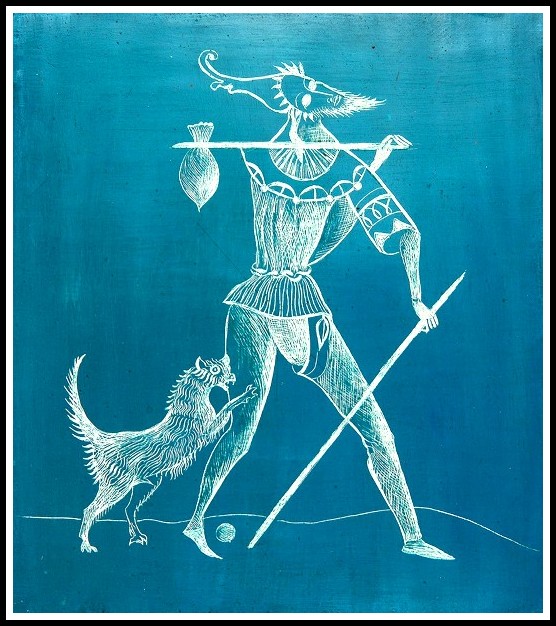

The cat, with its double nature, takes on its full significance in Fini’s work as a miniature reflection of the mother/monster, earth/hell, life/death goddess Fini wishes to incarnate herself. The last card of the Tarot, the Fool, is represented with a cat clawing and biting the Fool in the leg and probably the testicles. Much has been said about Fini’s castrating effect. Several photographs show her hair provocatively styled to imitate Medusa’s snakes.

Leonora Carrington, The Fool, 1955

Conversely, Fini has expressed the earth and fertility aspect of the Goddess in a series of pictures representing a woman with a shaved, egg-shaped head holding a large egg in each of the alchemical colors. In the third painting, titled (like Carrington’s story) The Oval Lady, the even larger white egg has become the woman’s pregnant belly; a winglike cloak draped about her against a black background suggests the presence of death.

Leonor Fini, The Oval Lady, 1956

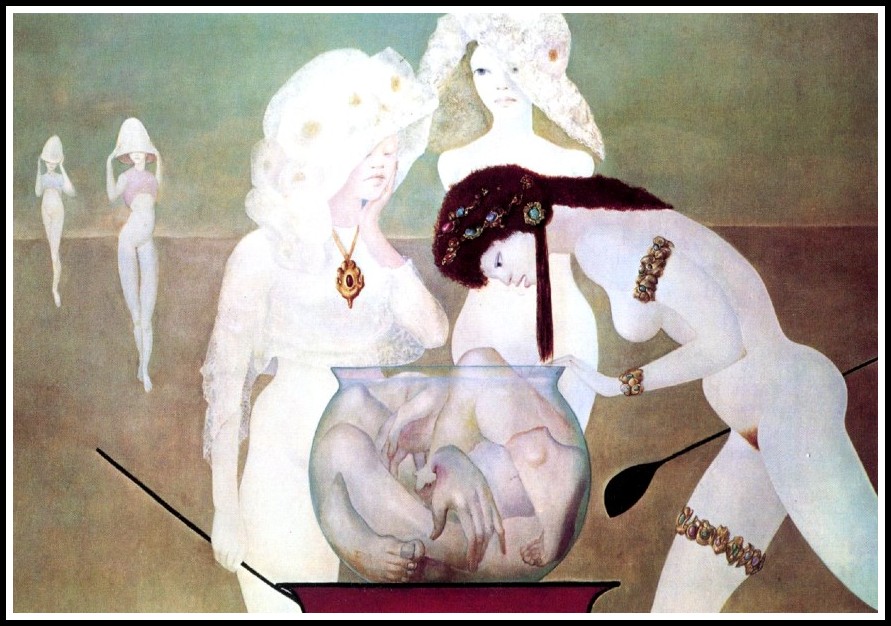

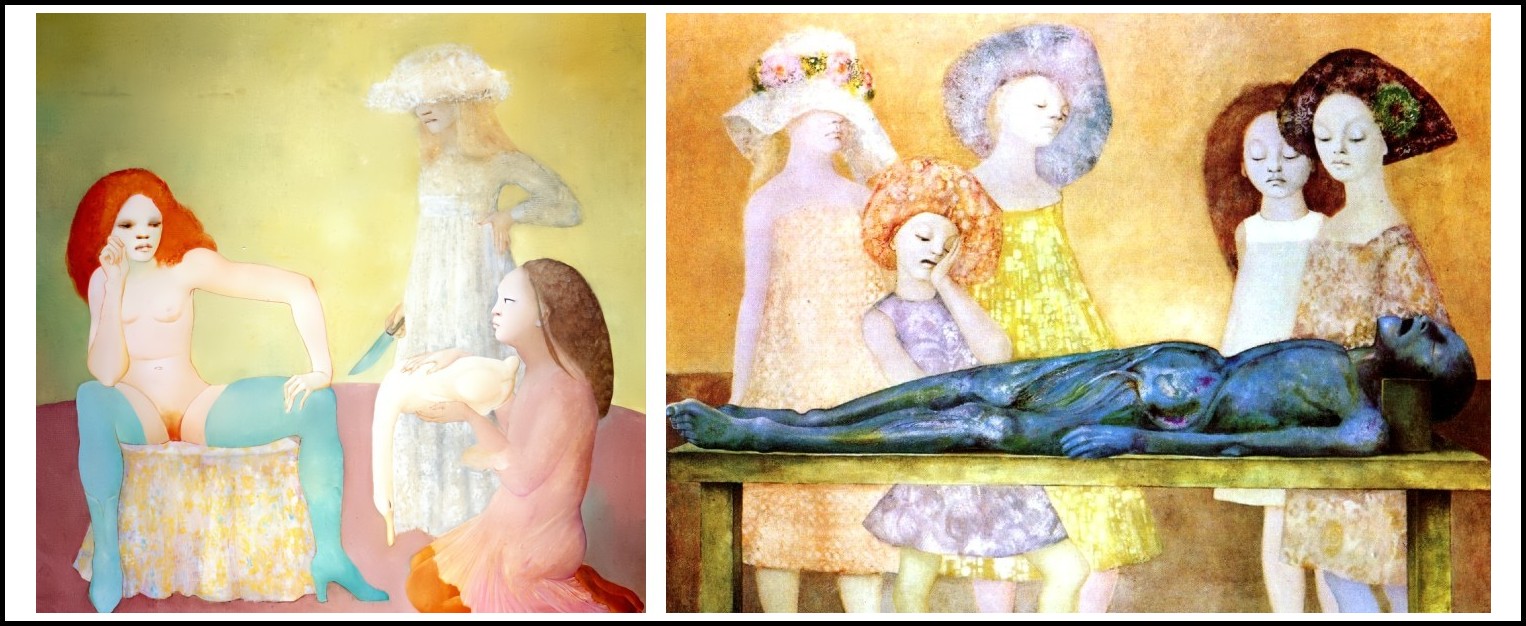

Like the Goddess in her macabre aspect, and unlike Carrington’s and Varo’s fruit-eaters, Fini’s protagonists can be murderous, carnivorous and even cannibalistic. In The Strangers, three women with wooden spoons stand around a glass bowl of human limbs.

Leonor Fini, The Strangers, 1968

Unsavory dissections and operations appear in several pictures. This type of horror recalls fairy tales, some of Carrington’s stories (not her painting), and the Red Queen’s ‘Off with their heads!’ Witches, ogres, monsters and assassins are natural components of a child’s imagination. Fini told Gauthier that she had decided long ago to remain at the stage when a child thinks she is the whole world: ‘I am the snake that bites its own tail. I am the moon, Astarte, metaphysically a virgin, an Amazon’.

LEONOR FINI

Capital Punishment, 1969 | Anatomy Lesson, 1966

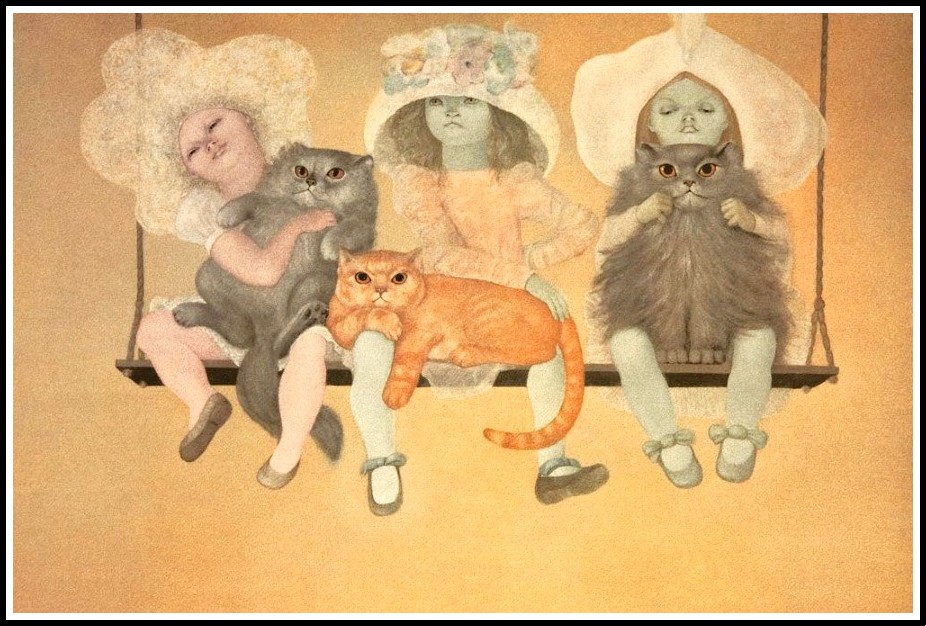

Like Varo, Fini believes in the superiority of cats, and like Carrington, she would prefer humans to be more animal-like. The Girl Mutants shows three little girls turning into cats. Their features seem so feline that one expects them to start purring. Each one is clasping a large cat between her legs, the site of her ‘pussy’. This picture reads like a perverse adult interpretation of a child’s dream. There is an underlying irony and self-irony about Fini’s work, creating a distance between herself and the world, such as can be perceived in cats, in Baudelaire’s idea of Beauty, and in Baudrillard’s fascination for women and animals. Neither Carrington’s passionate feminist quest nor Varo’s anxious inner peregrinations can be sensed behind Fini’s perfect aesthetics: she never removes her mask.

Leonor Fini, The Girl Mutants, 1971

Three artists, three witches, three animal incarnations of the Goddess (winged mare, owl-cat, sphinx-cat), and three symbolic colors, representing the microcosms of three ‘fantastic’ women painters: red for the molten gold of Carrington’s feminist life-drive…

Leonora Carrington

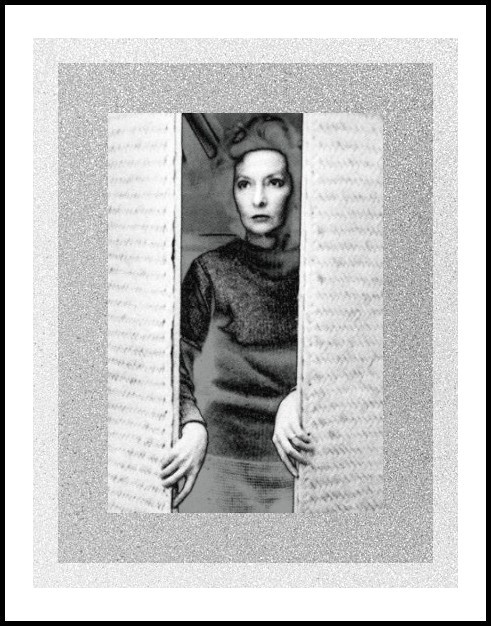

…white for Varo’s moonlit dream universe…

Remedios Varo

…and black for Fini’s chthonian otherworld.

Leonor Fini

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2026 | All rights reserved

Comments