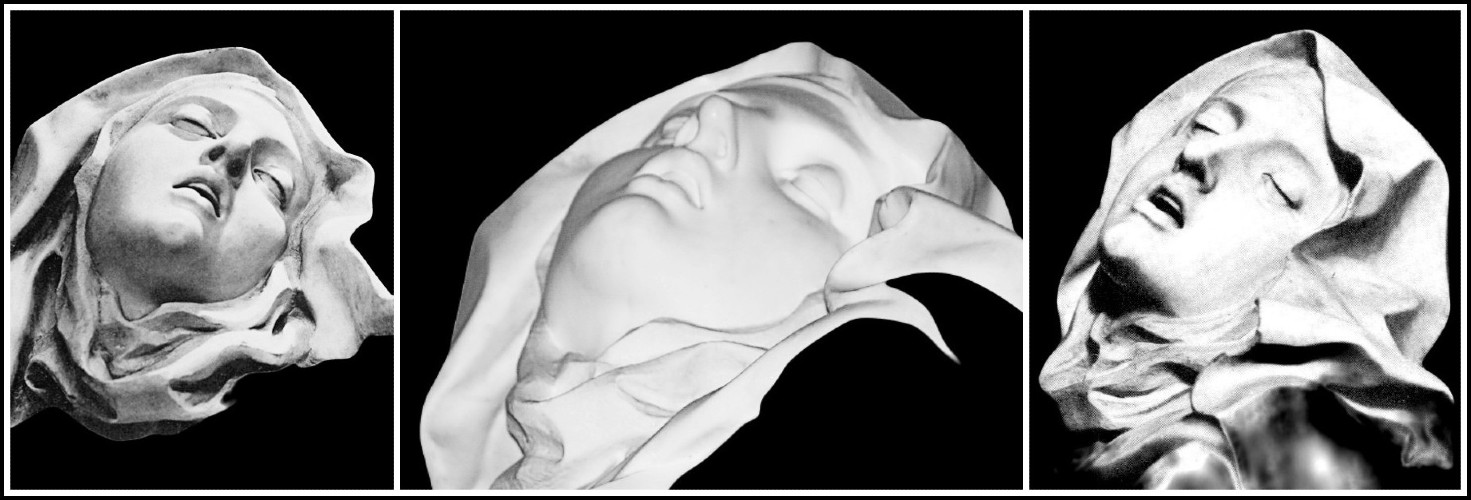

Bernini: Ecstasy of Saint Teresa

I. SAINT & SERAPH | II. BERNINI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’ | III. THE LIFE OF SAINT TERESA | IV. LACAN & FEMININE SEXUALITY | V. MYSTERICS: THE DOUBLING OF MYSTIC WITH HYSTERIC

BERNINI’S ‘ECSTASY OF SAINT TERESA’: AN ANALYSIS

SAINT AND SERAPH

Robert T. Petersson

From Robert T. Petersson, The Art of Ecstasy: Teresa, Bernini, and Crashaw (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1970) pp. 68-74

The figure peering from the right side is trying in vain to see the radiant saint and seraph in the centre. Their dominance in the chapel results in part from the special way they are lighted. At the top of the housing Bernini ordered to be built on the church’s outside wall are several windows which let in light from the outside, after which it is filtered by a pane of amber glass to soften its effect on the stark whiteness of the marble figures as it falls on them from above.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–1652 | Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

Bernini’s innovation of bringing natural light in from outside, which he had used earlier, comes into several other works, to particularly good effect behind the Cathedra Petri and over the reclining figure of the Blessed Lodovica Albertoni. The tinted light makes the ‘flesh’ of Teresa and the seraph look more real, yet also slightly transparent and impalpable. The light was originally gentler and less white than the light which now pours down from fluorescent tubes concealed in the architectural frame. A strange paradox when natural light is preferable to artificial in creating the illusion of a mystical event! However, if the imaginative effort is made to recover the miraculous scene as Bernini created it, one must take into account those things which interfere with both the mystery and the realism of the work. Nearly all photographs belie the subject by lighting it strongly from the front and by recording it horizontally rather than from the viewer’s lower angle of vision. Light, we quickly discover, is a crucial element of the form, and since it has symbolic value, of the meaning too. The effluence of God issuing from a divine, unseen source above, comes down the golden shafts behind Teresa to bathe her in heavenly brightness.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647–1652

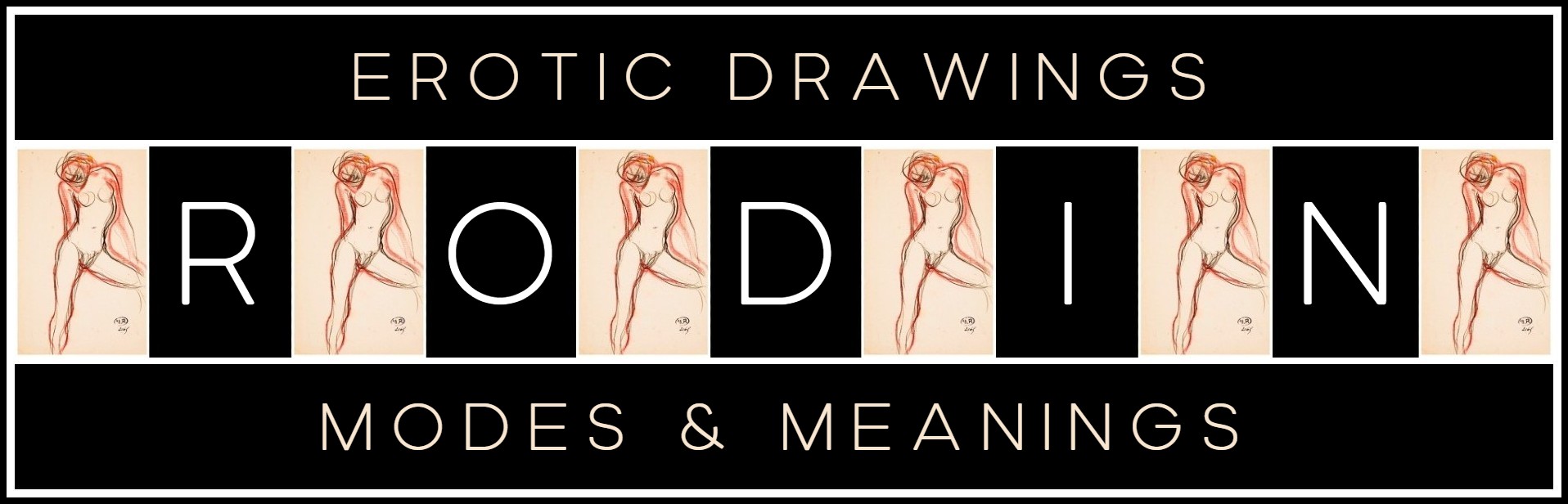

Like movement, light is a crucial artistic principle with which baroque artists experimented extensively, and often mastered for their individual purposes. Whether one thinks of Rodin, Michelangelo, or Bernini, sculptors and architects in general use light for much more than the ordinary necessities of vision. For the painter it is something different. Relatively speaking, the light in a painting is intrinsic, inherent, because it is painted in. In celebrated instances like Caravaggio’s Calling of St Matthew, Rembrandt’s Christ before Pilate, or la Tour’s St Sebastian and St Irene, intrinsic light composes the painting and produces the drama.

Caravaggio, The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1600

On the other hand a sculptor understands that light is absolutely essential—precisely the right light, in tone, in amount, in angle or angles—if a work is to achieve realization. It is relevant to the Teresan statue that when light strikes mat surfaces it is sopped up, and when it strikes polished surfaces it is fractured and flung off into dark areas. Consequently the light which accentuates details can also blur them and alter the total form. Yet that very blurring can also unite the form. Appropriate lighting can give to a work a feeling of unreality, or heightened reality, while preserving its realism. Here, by a kind of magic, light causes the shadows, dull areas, and bright points to coalesce. It serves the purpose of unity, which in this case is indistinguishably artistic and spiritual. A single form combining the two figures is dimly visible, although parts of it dissolve and escape into the light. Light determines the comparative significance of different areas of the chapel, and in a symbolic sense attaches Teresa to divinity.

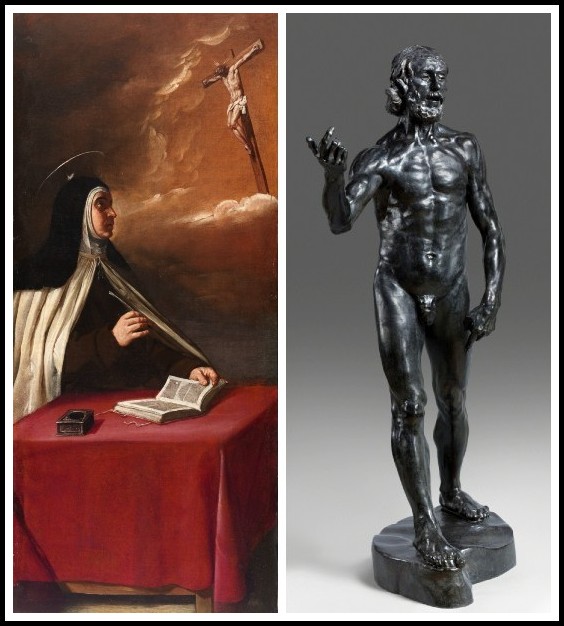

Alonso Cano, Christ – Teresa, 1629 | Rodin, Saint-Jean-Baptiste, 1880

The figures of the saint and seraph, which are Bernini’s own, are done with evident care and devotion. Excepting the slight possibility that he carved ‘the last Cardinal Cornaro’ (as Baldinucci says), it is only certain that Bernini did the central group, although of course he designed the chapel as a whole and supervised the work. In a zone beside and above the terrestrial zone Teresa appears life-size and expressively lifelike, and beside her appears grace in the form of an angel. To be sure, the life-likeness is illusionistically expanded to the breaking point. The saint’s facial features are classically idealized, seemingly perfect and imperishable.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652

She is the true sister of the Apollo Belvedere and Bernini’s own Apollo…

Apollo Belvedere, Roman copy of Greek original | Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652 | Bernini, Apollo & Daphne, 1625

… and the body beneath the folds of her habit is unnaturally long, the drooping hand and extended foot drawn out into a Mannerist look.

Francesco Mazzola aka Parmigianino, Madonna with the Long Neck, 1540 | Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652

In her figure Bernini continues to maintain his style of realistic illusion. At the same time, the carving of individual features such as the mouth, fingers, and toes is also relatively true to life. But the secret of the sculpture is that Teresa is quite withdrawn and nothing like as fully revealed as she at first appears to be. The large frame around Teresa and the seraph floats them in space so that they seem to have lost contact with the surrounding world. Below them the only support is a shadowy cloud. Behind them a panel of alabaster suggests indefinite and tenebrous distance. The long metal shafts of golden light which partly obscure the panel only augment the effect of her isolation from the world. Intentionally or not, Bernini’s arrangement expresses in graphic terms the distress of losing human connections felt by the historical Teresa in advanced states of contemplation. Though accessible to our perception, this marble Teresa does not perceive us.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1647-1652

In contrast to her white-monochrome intensity the frame is a mottle of colours. Beside her silence and secrecy the patterns of onyx move unquietly, spreading out toward other shapes and shades of marble in that part of the chapel. In good light one sees that the most vivid colouring in her vicinity is the green of the pilaster faces, which deepens into darker green next to the alabaster panel.

Bernini, Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

Especially at close range the colour and pattern of these greens have a marine effect, as though bright flecks of foam and sunlight were disturbing the water. The effect is more natural and literal than symbolic. The earth colours all around, particularly the rich brown of the panel behind, complete the impression of a terraqueous world. All these life-infused colours, together with the death colours below, appear to converge on Teresa, as though impinging on her from earthly life and rising up to her from the sea depths. Their meanings unite in her just as prismatic colours all unite into white. Teresa’s light is not all her own, however. As she says, in what only seems to be a paradox, visionary light ‘is like natural light and all other kinds of light seem artificial.’ From the spectator’s point of view the pavement of the chapel is passing death, the celestial landscape an anticipation, and the greens of nature a principle of ever-reviving life. The distance and isolation which seal in the meaning of ecstasy begin slowly to reveal it. Having been held at a respectful distance, the viewer is ultimately summoned forward by the sprung shape of the architectural aedicule. Seen thus, the frame resembles a richly classicized bow-front proscenium with a small opening. It is as if Bernini had begun with a heavy, flat frame whose pediment and entablature rest solidly on its double columns and pilasters, and then by main force had bent the entire frame into an advancing curve, breaking the pediment and entablature, in order to reveal the scene within.

Bernini, Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

The face of the Correggiesque1 angel is openly communicative. He (if angels have gender) has descended on the shafts of light and is poised with the dart of love in his hand. The softened lines of his body and arms bear no resemblance to those of the armed soldier or hunter. His left leg puts him in a position completely unsuited to an aggressive act. Instead he is an idealized picture of grace and celestial gentleness, a member of the benign order of the universe and Christ’s agent of love. His serenity stands out against the busier, more existential appearance of most of the Cornaros. The face is flawlessly sweet and luminous, not ruddy like those of other seraphs but glowing with cool, white ardour. And his face is silently fixed on Teresa.

1 – I find Caravaggio’s Cupid to be closer to Bernini’s angel than any angel by Correggio.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652 | Caravaggio, Victorious Cupid, 1602

All lines of perception meet in Teresa. The death-figures, the witnesses, and the glorification to come, compose the Teresan cosmos. Heaven and earth commune in her figure, its light radiating over the forms and into the space of the vertical chapel. The frame encloses her as she in turn encloses the mystery. On the earthly level where visitors come to worship, the relief of the Last Supper makes clear the sacramental purpose Bernini has in mind. Though common enough as a subject on earlier altar faces, it is noticeably absent on those in Roman baroque churches. Nearly always it is decorative marbles which appear there, not narrative scenes. In this chapel the Last Supper relief serves as the liturgical equivalent to Teresa’s more intense and exceptional communion with God.

Bernini, The Last Supper, Cornaro Chapel

The ecstasy itself is expressed solely in her figure, in the details and suggestions of her form and features. The ‘plastic sensibility’ which Bernini calls upon is responsive to volume, among other things, and in this instance the volume contains meaning. The outer form refers inwardly. It has an existence of its own, yet it exists also for what it discloses beneath the surfaces of her skin and clothing—provided, of course, that it makes sense to speak of outer and inner form separately, as Bernini would not. But the figure does not reveal itself quickly. When did the ecstasy occur? How did it occur, and what is the seraph’s part in it? Teresa’s face and posture seem to show her still engaged in the ecstasy, or just released from it. But since the seraph is holding the dart as if ready to plunge it into her, perhaps the event has not yet occurred. His somewhat relaxed posture only complicates the question. And again, if the dart has already been thrust into her breast, no wounds are evident. Finally we cannot say whether the event is to come, is occurring, or has come and gone. Bernini presents Teresa in the simplest terms possible, without cross, beads, cincture, or sandals. Choosing to interpret the word descalzo (‘barefoot’) literally, he omits her rope sandals. It is an essential Teresa he creates, a woman of indeterminate age—is she twenty or fifty?—whom he clothes in a plain, voluminous habit which makes her body all but disappear. Her reposeful and rapturous face (which a lesser artist might make into a monochrome mask) is carved into animation. The naturalistic appearance of the eyes Bernini achieved by incising very deeply beneath the lids, and by chiselling out the space around them to produce the bluish impression he saw in the faces of living people.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652

The face is idealized yet strongly sensuous. Of the erotic quality so often commented on, fleeting signs are visible in the hands and feet, in the contours of the mouth, chin, and brow, and in the posing of the body beneath the robes. Unquestionably the figure of Teresa is erotic, but in no exclusively physical sense.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652

The facial expression is full of passion yet its spiritual content distinguishes it very readily from, for instance, the pure earthly passion showing in the face of Costanza Bonarelli. Teresa seems to be breathing, her mouth warm, moist, and a little opened as if releasing the silent moan mentioned in the Vida: ‘not aloud, for that is impossible, but inwardly, out of pain.’

BERNINI: Costanza Bonarelli, 1638 | Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652

Without the overwhelming spiritual motive, Teresa would indeed be the woman William James saw as carrying on ‘an endless amatory flirtation’ with God. The motive is not overlooked by Simone de Beauvoir in explaining the body’s role in ecstasy—the same role it has had in Christian ecstasy generally, one might add, for not until recent centuries has it been necessary to explain that in genuine religious ecstasy body, mind, and spirit are all involved. As she says, St Teresa ‘in a single process seeks to be united with God and lives out this union in her body.’ But we recall that Teresa herself speaks at first-hand about this aspect of ecstasy: ‘It is not bodily pain, but spiritual, though the body has a share in it—indeed, a great share.’ In union Teresa’s human and divine natures both belong to God. Teresa’s moment of ecstasy looks to the resurrection of body and spirit alike. Yet the moment is obscure. As in the Vida, Teresa’s eyes are closed. She does not see the seraph of her vision with her physical eyes. Though he is necessarily visible to our wakened sight, he is visible only to her internal sight. Bernini seems almost to be asking that the seraphic vision be ‘seen’ through the saint, that it be re-experienced imaginatively through what is taking place within Teresa’s visible form. What shows is a symbolic presentment of her inward state. Enigmatic as that may be, we look more closely still.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652

In Teresa’s hands and feet her simultaneous excitement and quiescence are revealed. The right hand resting relaxed in her lap and the left hanging limply at her side make known the body’s assent to transport, and the exhaustion which follows. But her feet express a tenseness. The foot held perpendicular to the extended leg is flexed as though in spasm, and her taut right foot, almost invisible in the filmy billow of cloud, presses against it so hard that the cloud seems to resist like stone.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652

The somewhat regular folds of her rumpled habit apparently result from her inner vibrancy, from the agitation and strong fibrillations of her body in the grip of transport. To judge from the contours of the habit—and we should be able to, since Bernini’s handling of drapery became more abstract and symbolic as time went on—the tautness and vibrancy may run through Teresa’s whole body. But does it? The slim, indistinct form under the robes appears to be fully relaxed also. Perhaps the tension is only in the lower parts of the body and the rapture at this precise moment has released its grip on her upper body and is working its way out through her lower extremities. The figure of Teresa is a perfect mingling of tension and relaxation. But ordinary logical structures collapse before the spiritual reality. The carefully wrought ambiguities point to the ecstasy without encompassing it. Something is inevitably missing. The limits of understanding have been reached and we, like Dante’s pilgrim or Milton’s Adam—or Bernini—are not privileged to go further. Yet we are sure that there is an ecstasy, and that ecstasy, as Bernini and St Teresa show it, is a condition transcending the ordinary opposites of pleasure and pain, body and spirit, motion and rest, weight and weightlessness, time and timelessness. Bernini gives us the figure of a woman uniquely posed, neither sitting nor lying down. The tendency for the weight of her body to make her fall is weaker than the tendency for her cloud-borne figure to rise. The highest folds of her habit are more buoyant than air. The ecstasy is a troubled state of transition between existence on earth and existence above. While her exterior nature occupies space and time, very little of her interior nature, the secret scene of her experience, is still in the world.

Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652

The actual saint returned from her visionary moments to live her daily life, the same woman yet spiritually heightened and invigorated. Gradually these moments led to permanent change. She speaks of being touched by a kind of dreaminess. God, she explains, ‘has given me a life which is a kind of sleep; when I see things, I seem nearly always to be dreaming them.’ The borderline between actuality and spiritual transcendence is obliterated by Bernini and St Teresa both. Though Bernini’s marble likeness remains fixed it always seems ready to rise into the celestial zone. Teresa’s life in the statue, and in history, has by now become more than earthly. Her resemblance to sleep may actually be her awakening from time. As surely as Teresa’s ecstasy is happening within time, it is also happening beyond time, and we are beholding an event which has no duration.

José de Ribera, Figure of a Woman, 1636 | John Singer Sargent, Saint Teresa of Avila, 1903 | José de Ribera, Christ the Saviour, 1630

II. BERNINI’S ‘ECSTASY OF SAINT TERESA’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel, ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 17

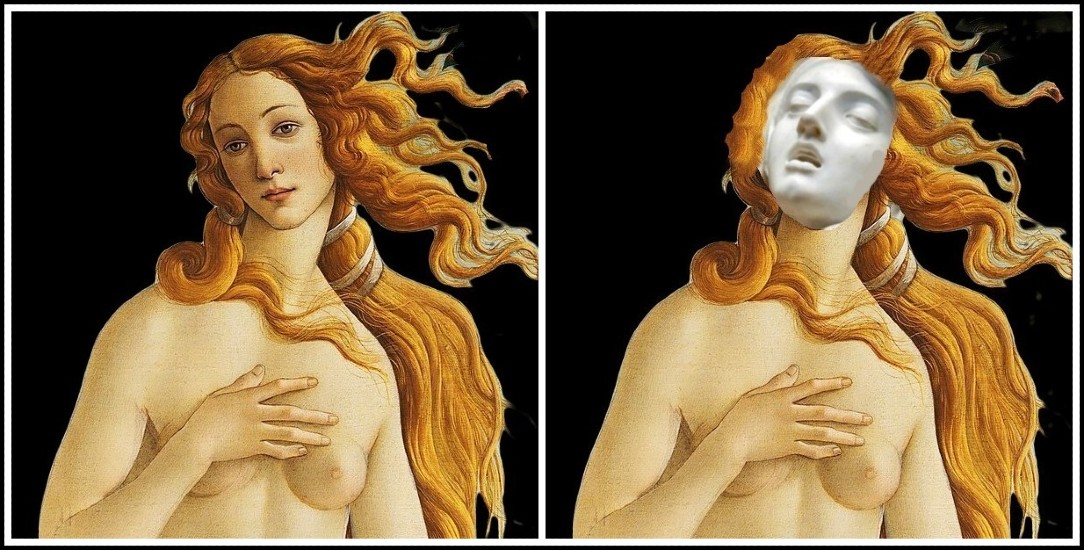

Spectacled bear, Asiatic black; Alaskan grizzly, polar bear: Compared with other carnivores, bears walk slowly and deliberately, with all five toes as well as their heels touching the ground: She hardly moves her feet, Julie, when she dances (I’m dancing with her while you’re dancing with Jean-Luc). She compensates, though, with a sexy to-and-fro of her torso and a charming je-ne-sais-quoi in her arm movements. There’s a fullness to her flesh, a real physical presence, yet as puppet artist she must have mastered the world as shadow play. Her modesty moves me. How many ways are there of being a woman? In the infinite variety of the universe, nothing touches me more than femininity. So many women, so little time! No, that’s not it. For in every woman there are all women. No, that’s not it either. What then? Shut up, just dance! I surrender to Bowie’s impeccable taste. Look! The Botticelli smile on Julie’s face has been replaced by the swoon of Bernini’s Teresa! Oh Julie, Julie, I tell you truly, more than how you dress, I love how you undress me! Use me, use me, my puppeteer, use me to burst your body into flame: Have no regrets when the dance is over.

Botticelli, Spring, 1482 (detail) with Bernini, Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, 1652 (detail)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

III. THE LIFE OF SAINT TERESA

Teresa of Ávila

From The Life of Saint Teresa by Herself, translated and with an introduction by J.M. Cohen (Penguin Classics, 1957), pp. 209-211.

O how often, when I am in this state, do I remember that verse of David, As the heart panteth after the water brooks, which I seem to see literally fulfilled in myself. When these impulses are not very strong, things appear to calm down a little, or at least the soul seeks some respite, for it does not know what to do. It performs certain penances, but hardly feels them; even if it draws blood it is no more conscious of pain than if the body were dead. But there are other times when the impulses are so strong that it can do absolutely nothing. The entire body contracts; neither foot nor arm can be moved. If one is standing at the time, one falls into a sitting position as though transported, and cannot even take a breath. One only utters a few slight moans, not aloud, for that is impossible, but inwardly, out of pain.

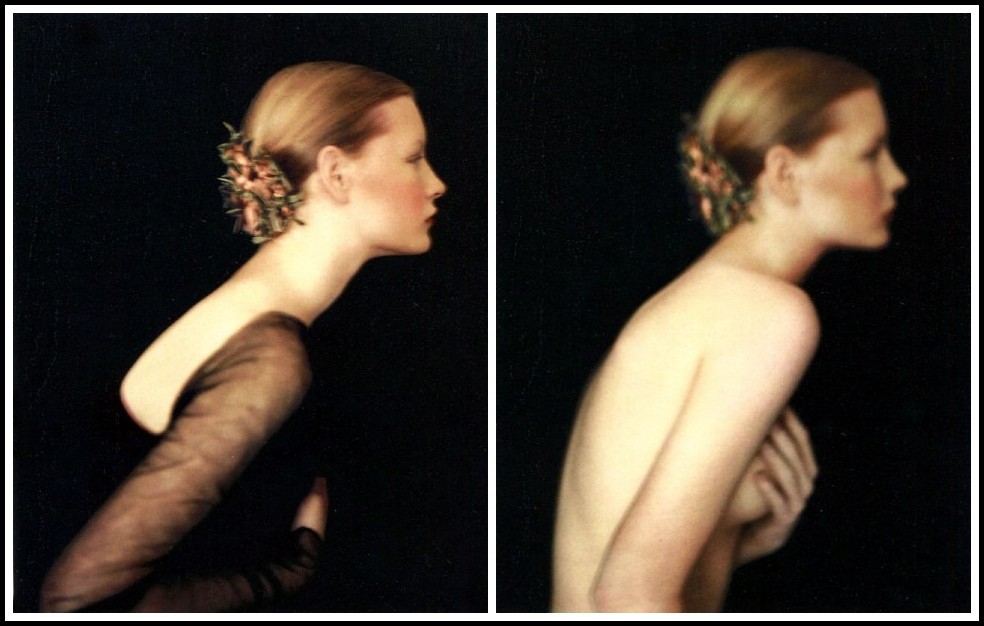

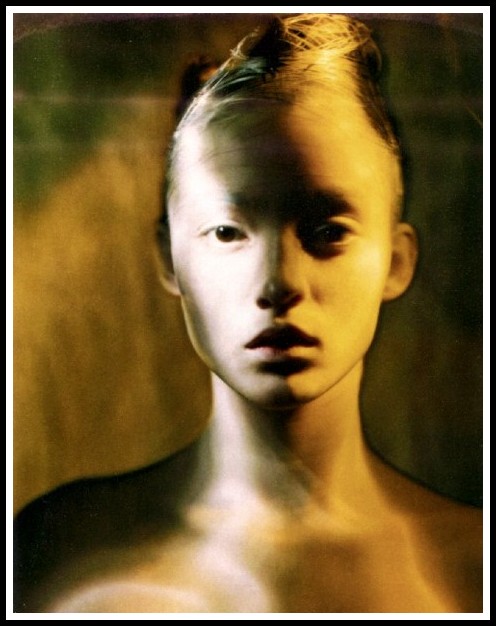

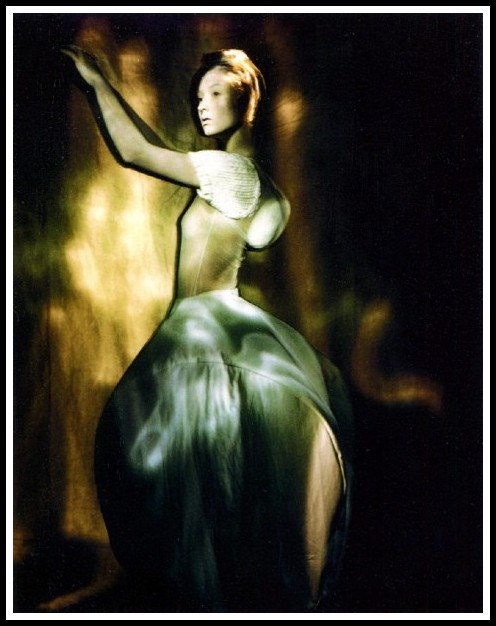

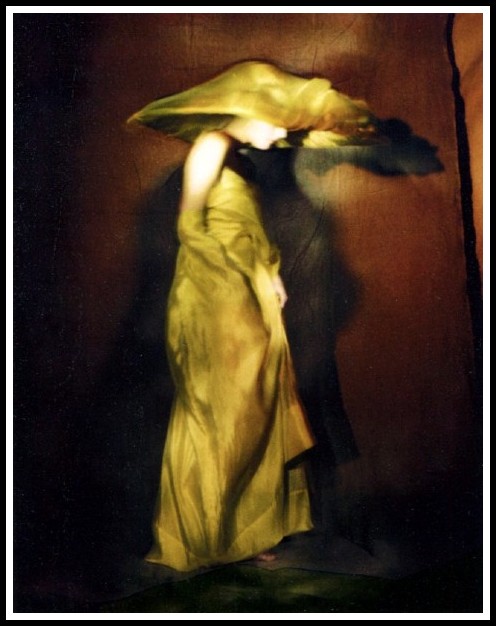

Paolo Roversi, Kirsten, Paris 1987

Our Lord was pleased that I should sometimes see a vision of this kind. Beside me, on the left hand, appeared an angel in bodily form. He was not tall but short, and very beautiful; and his face was so aflame that he appeared to be one of the highest rank of angels, who seem to be all on fire. They must be of the kind called cherubim. In his hands I saw a great golden spear, and at the iron tip there appeared to be a point of fire. This he plunged into my heart several times so that it penetrated to my entrails. When he pulled it out, I felt that he took them with it, and left me utterly consumed by the great love of God. The pain was so severe that it made me utter several moans. The sweetness caused by this intense pain is so extreme that one cannot possibly wish it to cease, nor is one’s soul then content with anything but God. This is not a physical, but a spiritual pain, though the body has some share in it—even a great share. But when this pain of which I am now speaking begins, the Lord seems to transport the soul and throw it into an ecstasy. So there is no opportunity for it to feel its pain or suffering, for the enjoyment comes immediately.

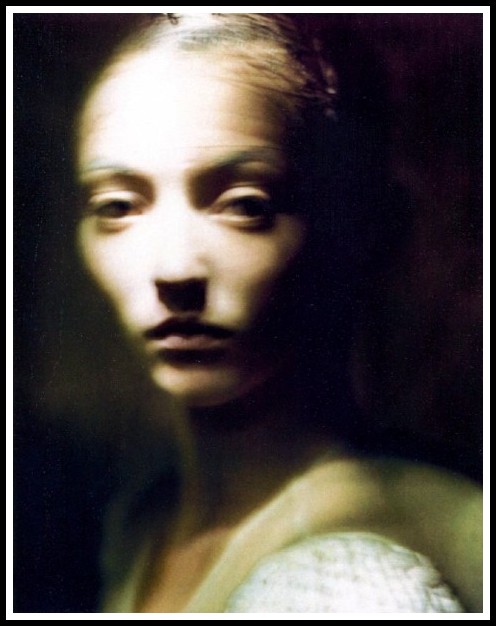

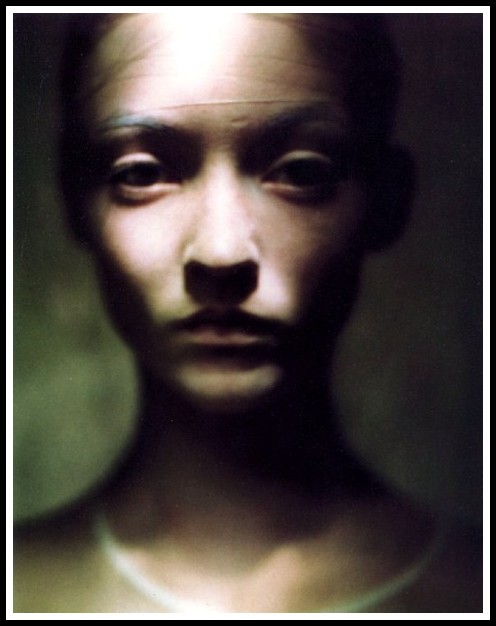

Paolo Roversi, Sharon / Sharon & Yelena, Paris 1996

IV. LACAN AND FEMININE SEXUALITY

Jacqueline Rose

From Jacqueline Rose, Feminine Sexuality: Jacques Lacan and the école freudienne, edited and introduced by Juliet Mitchell & Jacqueline Rose, translated by Jacqueline Rose (NY: W.W. Norton / Pantheon Books, 1985) pp. 32-33, 52.

You only have to go and look at Bernini’s statue of Saint Theresa in Rome to understand immediately that she’s coming, there is no doubt about it. And what is her jouissance, her coming from? It is clear that the essential testimony of the mystics is that they are experiencing it but know nothing about it.1

1 – Jacques Lacan, Seminar XX, Encore, 1972-73. In Feminine Sexuality: Jacques Lacan and the école freudienne, edited and introduced by Juliet Mitchell and Jacqueline Rose, translated by Jacqueline Rose (NY: W.W. Norton and Pantheon Books, 1985) p. 147

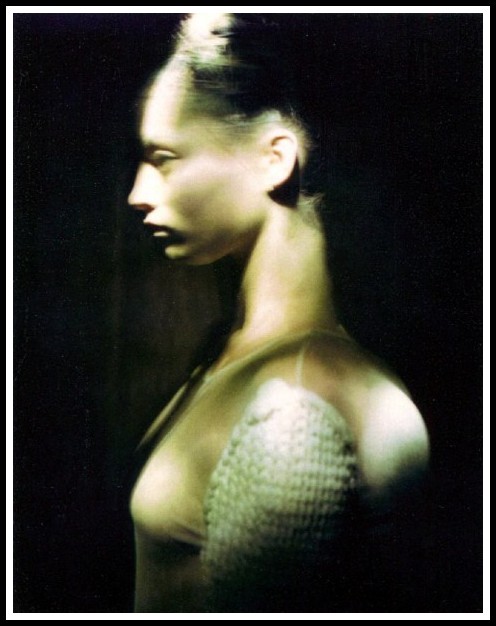

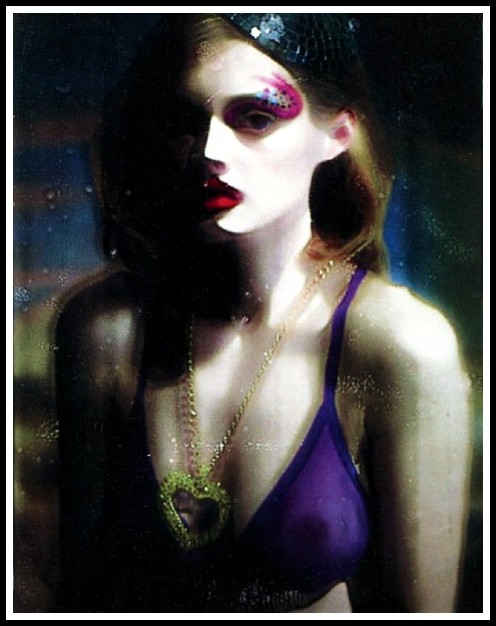

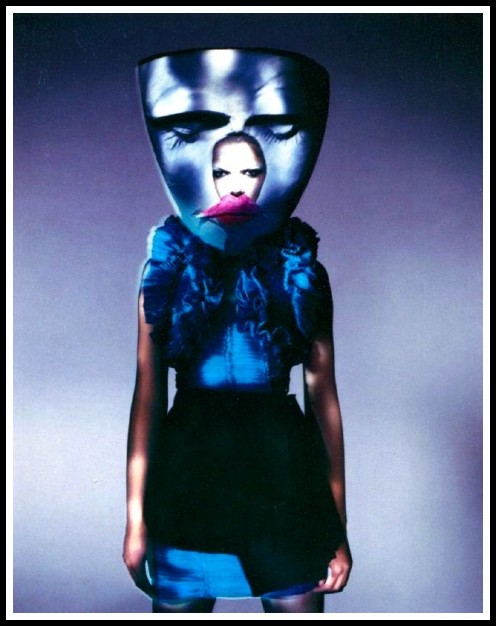

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

The concept of desire is crucial to Lacan’s account of sexuality. He considered that the failure to grasp its implications leads inevitably to a reduction of sexuality back into the order of a need (something, therefore, which could be satisfied). Against this, he quoted Freud’s statement: ‘We must reckon with the possibility that something in the nature of the sexual instinct itself is unfavourable to the realization of complete satisfaction’.1

1 – Freud, ‘On the Universal Tendency to Debasement in the Sphere of Love’ (1912), SE 11, pp. 188-189; PF 7, p. 258)

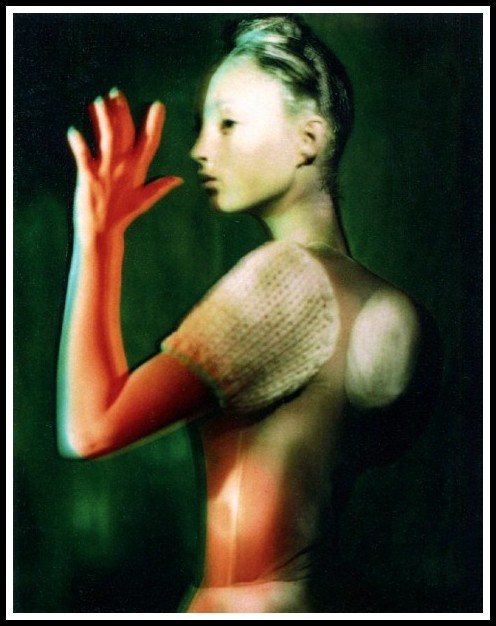

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

At the same time ‘identity’ and ‘wholeness’ remain precisely at the level of fantasy. Subjects in language persist in their belief that somewhere there is a point of certainty, of knowledge and of truth. When the subject addresses its demand outside itself to another, this other becomes the fantasied place of just such a knowledge or certainty. Lacan calls this the Other—the site of language to which the speaking subject necessarily refers. The Other appears to hold the ‘truth’ of the subject and the power to make good its loss. But this is the ultimate fantasy. Language is the place where meaning circulates—the meaning of each linguistic unit can only be established by reference to another, and it is arbitrarily fixed. Lacan, therefore, draws from Saussure’s concept of the arbitrary nature of the linguistic sign the implication that there can be no final guarantee or securing of language. There is, Lacan writes, ‘no Other of the Other’.

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

Sexuality belongs in this area of instability played out in the register of demand and desire, each sex coming to stand, mythically and exclusively, for that which could satisfy and complete the other. It is when the categories ‘male’ and ‘female’ are seen to represent an absolute and complementary division that they fall prey to a mystification in which the difficulty of sexuality instantly disappears: ‘to disguise this gap by relying on the virtue of the “genital” to resolve it through the maturation of tenderness, however piously intended, is a fraud’.1 Lacan therefore argued that psychoanalysis should not try to produce ‘male’ and ‘female’ as complementary entities, sure of each other and of their own identity, but should expose the fantasy on which this notion rests.

1 – Lacan, ‘The Meaning of the Phallus’, p. 81. [See Lacan, ‘The Signification of the Phallus’ in Jacques Lacan, Écrits, translated by Bruce Fink (NY: W.W. Norton, 2006) pp. 575-584.

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

The concept of jouissance (what escapes in sexuality) and the concept of signifiance (what shifts within language) are inseparable. Only when this is seen can we properly locate the tension which runs right through Lacan’s Encore between his critique of the forms of mystification latent to the category Woman, and the repeated question as to what her ‘otherness’ might be. A tension which can be recognised in the very query ‘What does a woman want?’ on which Freud stalled and to which Lacan returned. That tension is clearest in Lacan’s appeal to Saint Teresa, whose statue by Bernini in Rome he took as the model for an-other jouissance—the woman therefore as ‘mystical’ but, he insisted, this is not ‘not political’, in so far as mysticism is one of the available forms of expression where such ‘otherness’ in sexuality utters its most forceful complaint.

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

And if we cut across for a moment from Lacan’s appeal to her image as executed by the man, to Saint Teresa’s own writings, to her commentary on ‘The Song of Songs’, we find its sexuality in the form of a disturbance which, crucially, she locates not on the level of the sexual content of the song, but on the level of its enunciation, in the instability of its pronouns—a precariousness in language which reveals that neither the subject nor God can be placed (‘speaking with one person, asking for peace from another, and then speaking to the person in whose presence she is’). Sexuality belongs, therefore, on the level of its, and the subject’s, shifting.

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

V. MYSTERICS: THE UNEASY DOUBLING OF MYSTIC WITH HYSTERIC

Lynne Huffer

Abridged from selected ‘fragments’ in Lynn Huffer, ‘Mysterics: Extinction and Emptiness’ in Mary C. Rawlinson & James Sares, editors, What is Sexual Difference? Thinking with Irigaray (NY: Columbia University Press, 2023)

For a long time, the story goes, the mysterical face signaled the ecstatic mutism of sexual pleasure. The ‘uneasy doubling’ of mystic with hysteric, spiritual with terrestrial ecstasy, has been central to the modern constitution of sex as the problem of truth. Foucault relentlessly problematized this sex-truth relation over four volumes of the History of Sexuality. But the nineteenth-century assemblage of sex as science and Christian pastoral began to dematerialize even as it formed. Sexology—as much an ars erotica as a scientia sexualis—would proliferate its perverts through the ‘reversed and somber escutcheon’ of a self-hollowing bourgeoisie. Degeneration and subsequent generations of biopolitical thought would arrange themselves as sexology’s mise en abyme of its own fictions. The more sexual knowledge tried to add to its store of knowledge, the more it hollowed itself out. La mystérique is the archive of that hollowing. With its stuttering, stammering, short-circuited speech, the sexual assemblage she appears to represent is pocked with holes. Her Sapphic skin charred and crisscrossed with cuts.

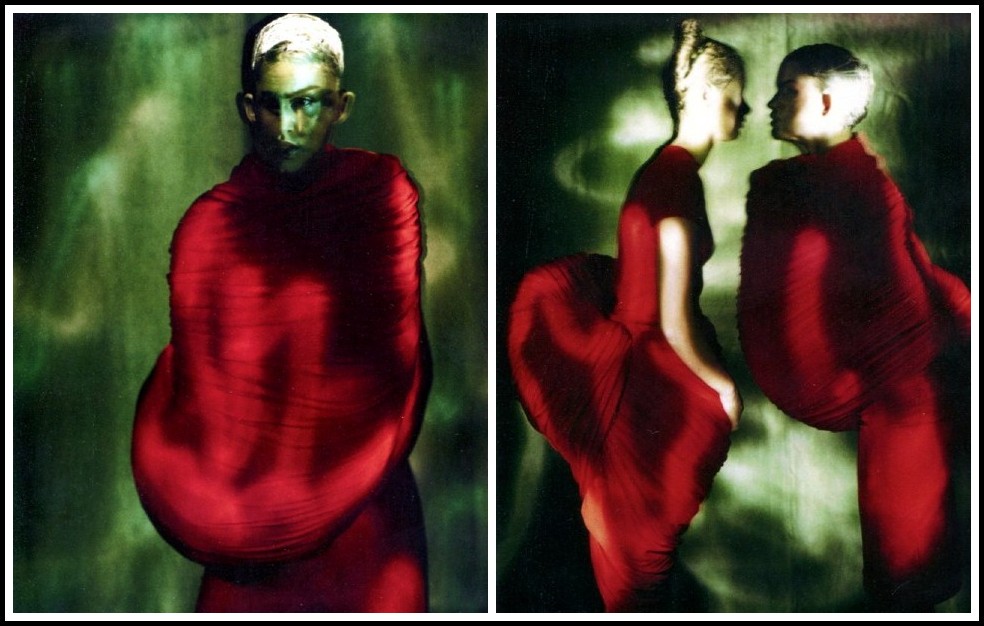

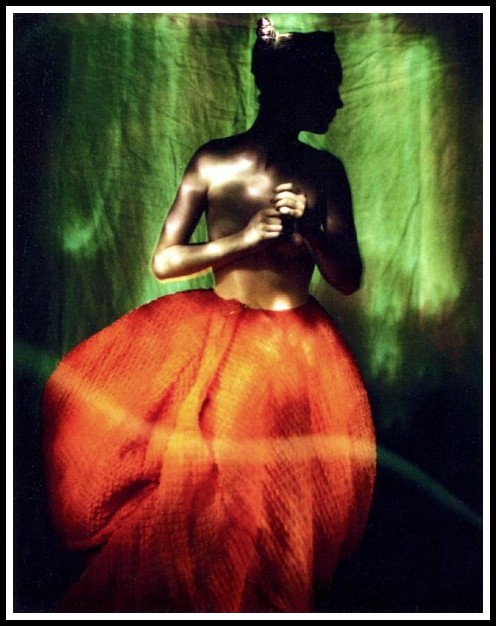

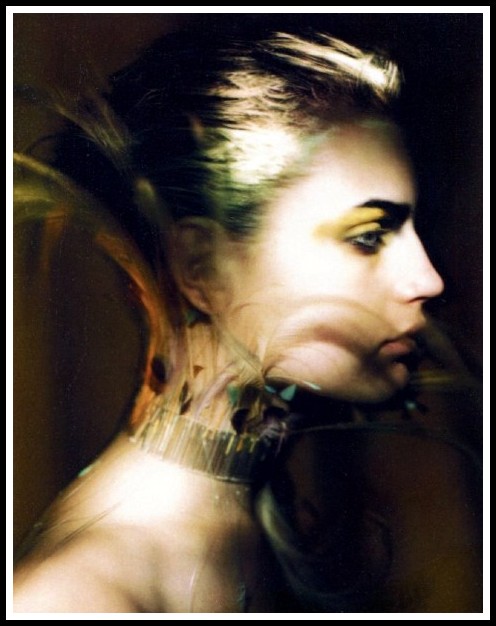

Paolo Roversi, Guinevere, Paris 2009

Liberated again by Freud into psychoanalysis at the end of the nineteenth century, the mystérique would reinvent herself in another form of capture: the specular, spectacular apparatus of sexuality. No need to put anyone in the panopticon’s central tower, which plays the role of what used to be God. The phallic tower would be the Irigarayan complement—Other of the Same—to the nothing to see: vagina, womb, anus, unconscious, death, crypt, cavern, tain, mother-matter. Half a century later, Lacan, the faithful Freudian son, would project the sexy starlet onto a psycholinguistic screen. La mystérique would become the stuff of wet dreams and mediatized fantasies of ecstatic departure: sex and death alone in the dark. Father Lacan says the obvious in Seminar XX: Encore: ‘As for Saint Theresa—you only have to go and look at Bernini’s statue in Rome.’ Wink wink. It sure looks like she’s coming but she’s stiff as a board. Once you see it, it’s undeniable. The mysteric is the will-have-been of living: a corpse. Speculum mundi. Cupped in these hands, you’re a sexy starlet. A crimson planet tilting off its axis. Lithic jouissance.

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

The lips convulse. Stuttering, spasmic, fiery. Mystics and hysterics for centuries now. Lacan’s Saint Teresa has become a star. You go to Rome and you ‘understand immediately that she’s coming, there is no doubt about it’. Encore! But, as usual, Father Lacan is toying with us. ‘What was tried at the end of the last century, at the time of Freud, was an attempt to reduce the mystical to questions of fucking, and that is not what it is all about.’ He knows it’s not about fucking. It’s about ‘that which puts us on the path of ex-istence’. Which is also the path of non-existence. No more breath, no more swooning. Just absence and silence. La crossed out. La femme. God may be dead, but Lacan still preaches the holy word. He is abundantly useful for thinking about nothingness.

Paolo Roversi, Guinevere, Paris 1996

La mystérique is the figure who makes possible this contemporary Lacanian speech about nothingness. Centuries of unreason confined or heretics burned at the stake produce a blank where God once was. God disappears over the horizon, leaving a silhouette, a trace darkened by the shadow of God’s fall. Covered in blood, God’s murderers crave transcendence. ‘The language of sexuality has lifted us into the night where God is absent,’ Foucault writes. Into the blank where God governed rushes the carceral speech of a swooning scientia sexualis. ‘Obey, keep quiet, your body will speak.’ Foucault barks, mimicking Charcot. The hysteric’s obedient body leaves open another gap: the mutism of her stigmatic wound. ‘Into the breach’—into that silent slit—comes the sexual speech, invented by science, now ventriloquized as medical evidence in the hysterics recounting of her ‘sexual life’.

Paolo Roversi, Kasia, Paris 2007

The mysteric collapses centuries of European history: Christianity’s mystics and sexuality’s hysterics flipped vertically, condensed into an absent-present figure-field of rupture. The mysteric is a breach, break, slit, fissure, crack. She looks like nothing and ‘knows nothing’. But she is not nothing. She empties. To empty is to ask to be filled. Into the emptying come those priestly intonations, from Lacan in the lecture hall to subreddit porn channels. Multitudes memorize these mysterical liturgies. But the mysteric we praise—look, she’s coming!—was always already a corpse.

Paolo Roversi, Guinevere, Paris 1996