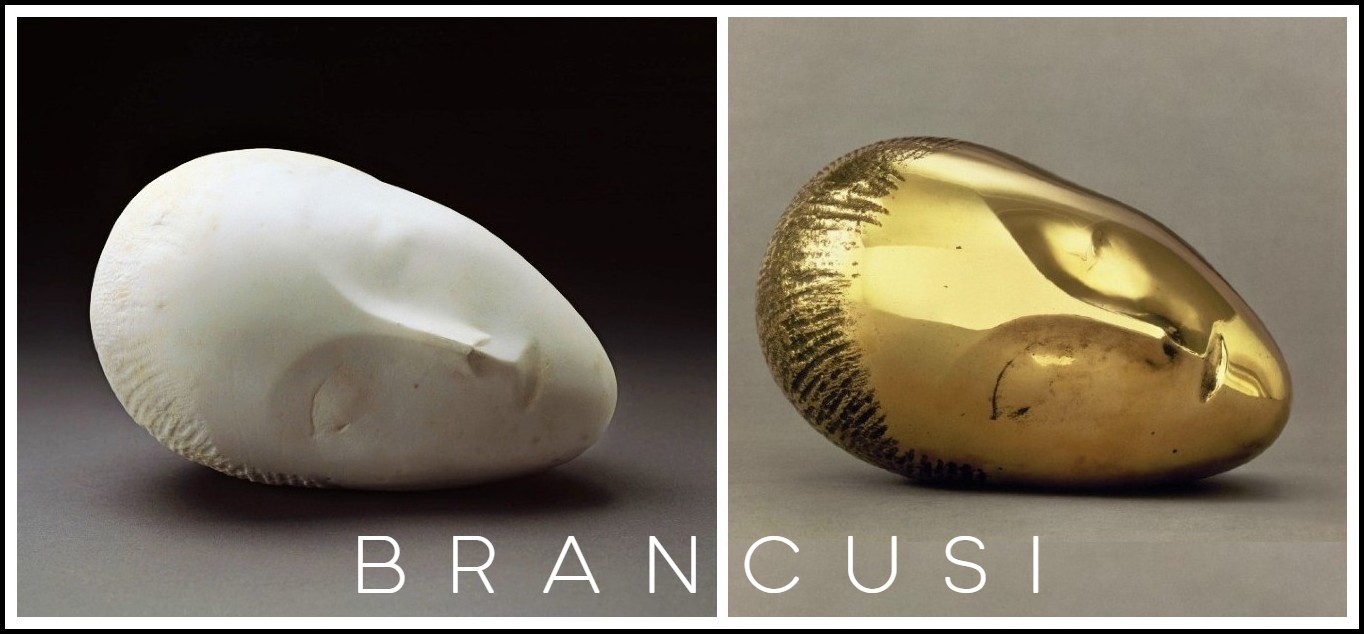

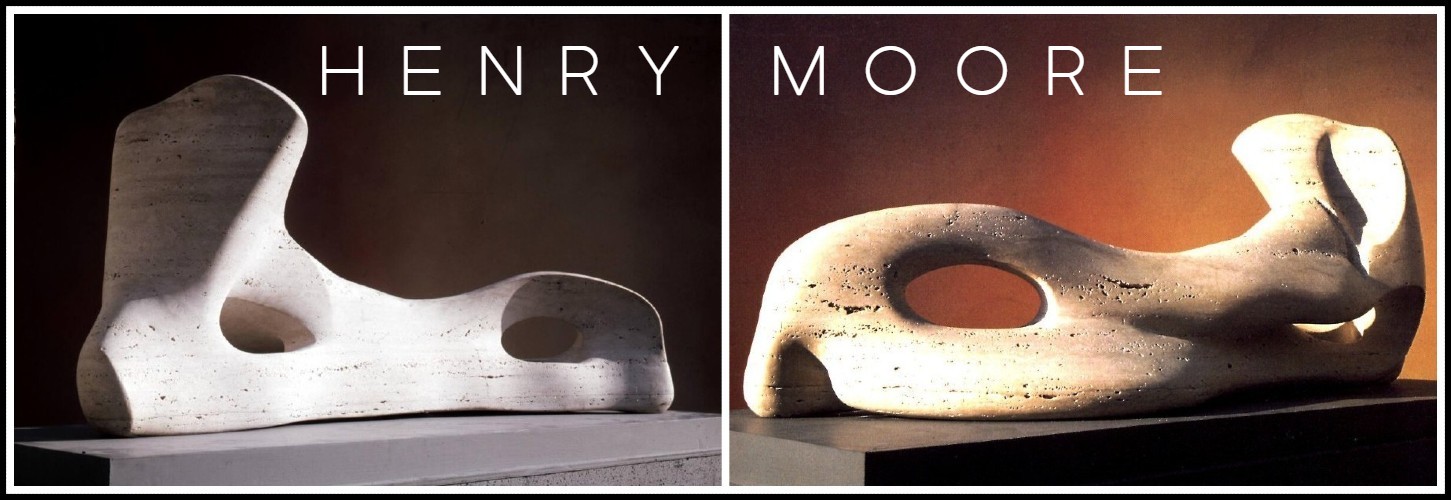

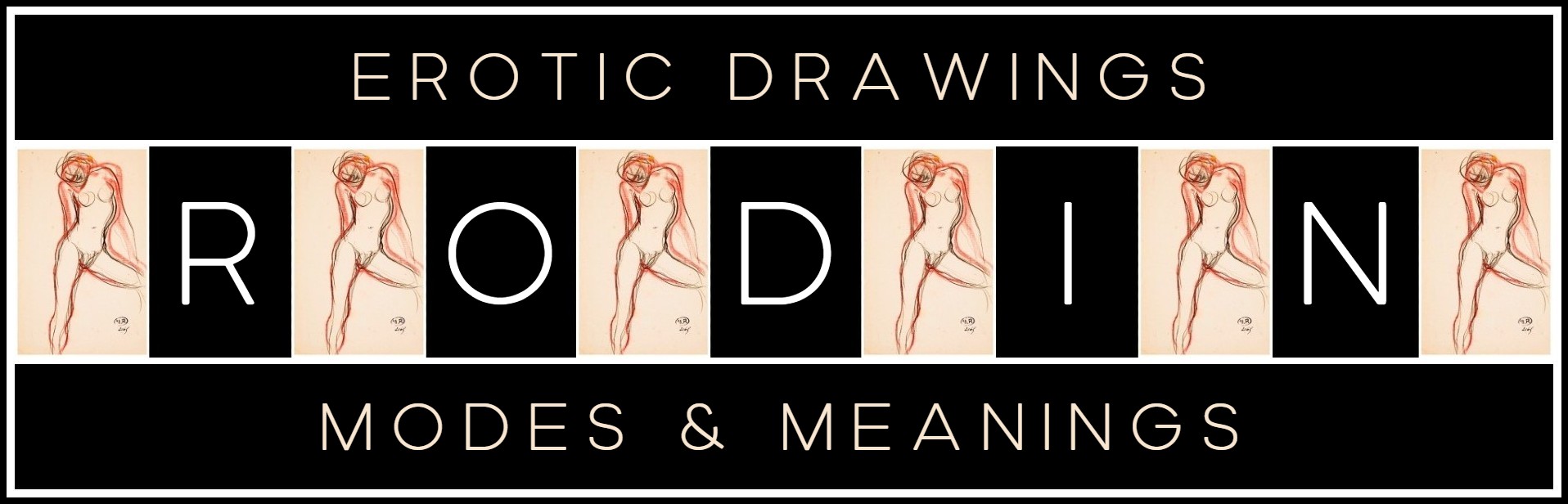

Rodin: The Erotic Drawings

RODIN’S EROTIC DRAWINGS: I. MODES & MEANINGS | II. GLORIOUS LUST | III. RODIN’S SECRET | IV. IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

I. KIRK VARNEDOE: MODES & MEANINGS IN RODIN’S EROTIC DRAWINGS

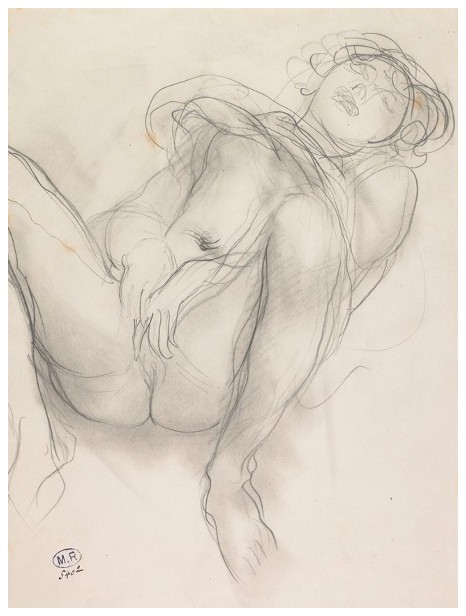

From Kirk Varnedoe, ‘Modes and Meanings in Rodin’s Erotic Drawings’ in Rodin: Eros and Creativity, ed. Rainer Crone & Siegfried Salzmann (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1997) pp. 203-09. I have edited the text to sharpen the focus on the erotic drawings.

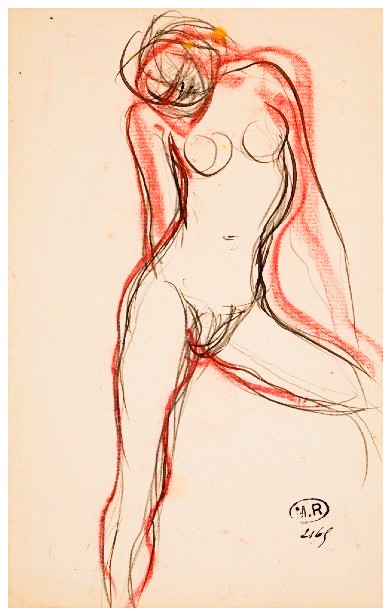

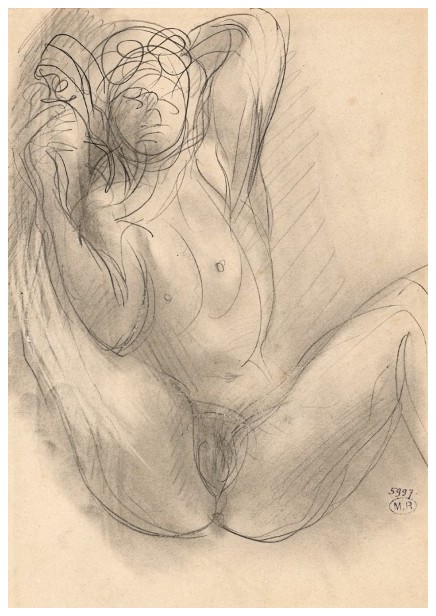

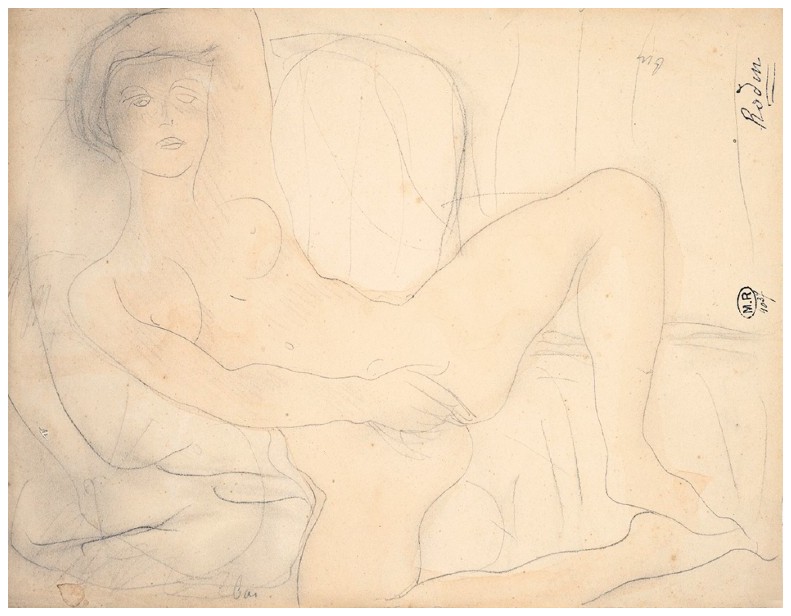

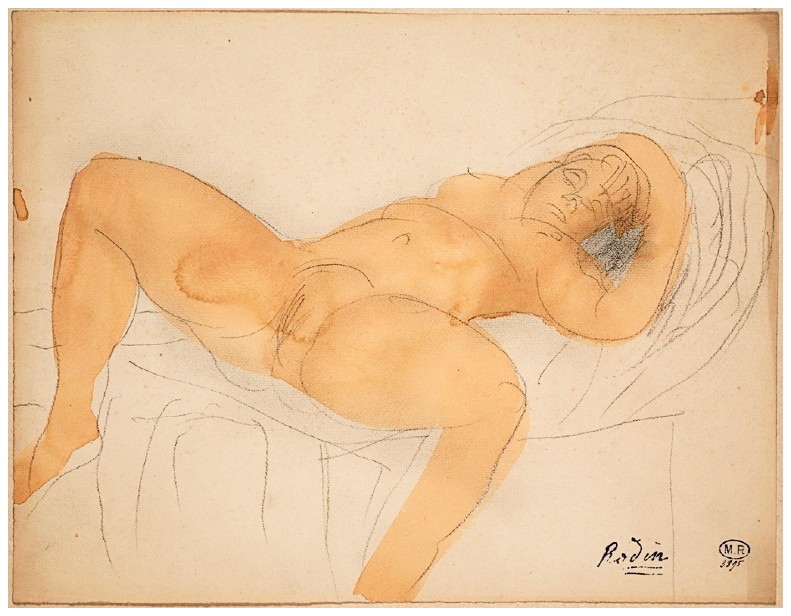

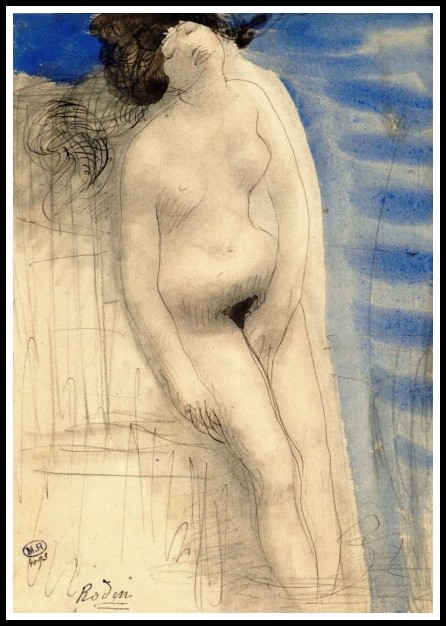

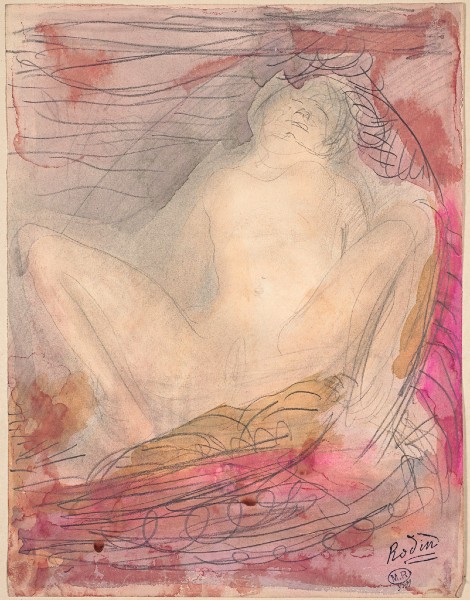

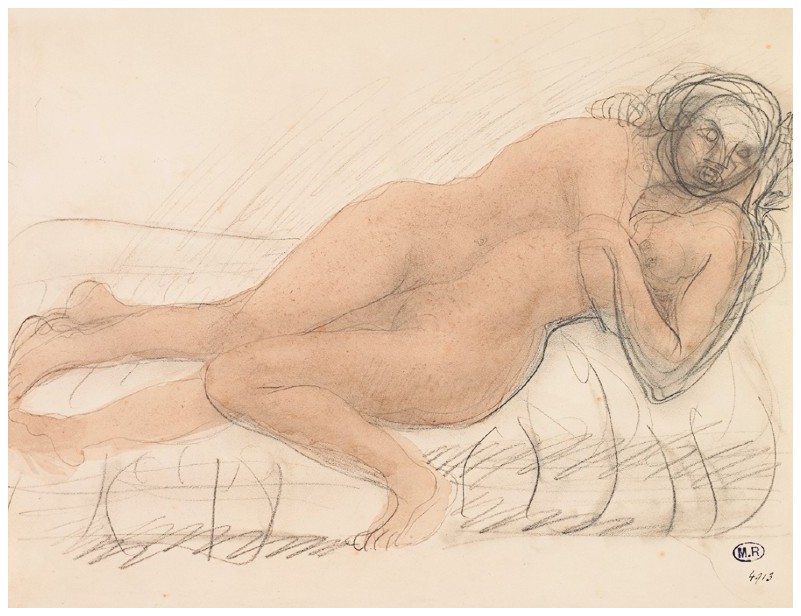

Rodin, Femme nue, jambe gauche écartée, 1895

Rodin has often been praised, in loose parallel with Freud, for ‘unmasking’ the centrality of the erotic in human experience. In such a view, the triumph of the modern outlook involved the bold removal of a crust of accumulated convention, in order to reveal ‘timeless’ truths beneath. Lately, however, we have become more skeptical about this kind of either/or opposition between ‘natural’ or unchanging aspects of humanity and time-bound, contingent aspects that are shaped by a particular culture and material circumstances. Freud himself, after all, can be read as saying something quite contrary: that our erotic behavior and even our erotic mental life, like everything else about us that may seem spontaneous and ‘natural,’ is always, and inextricably, the determined product of the contingencies of early individual experiences, and of the cultural constraints that surround us. His followers have gone even further in examining the unconscious as culturally structured, rather than primal and pre-existing. The erotic in Rodin’s art, then, may better be thought of as something made, rather than something simply found or discovered; and the forms in which eroticism appears in his work might profitably be examined, not as transparent vehicles for transmitting a transcendent truth, but as representational devices whose own nature and history are enmeshed in the meaning of the work. In this context, the artist’s later pencil and watercolor drawings of nudes are central.

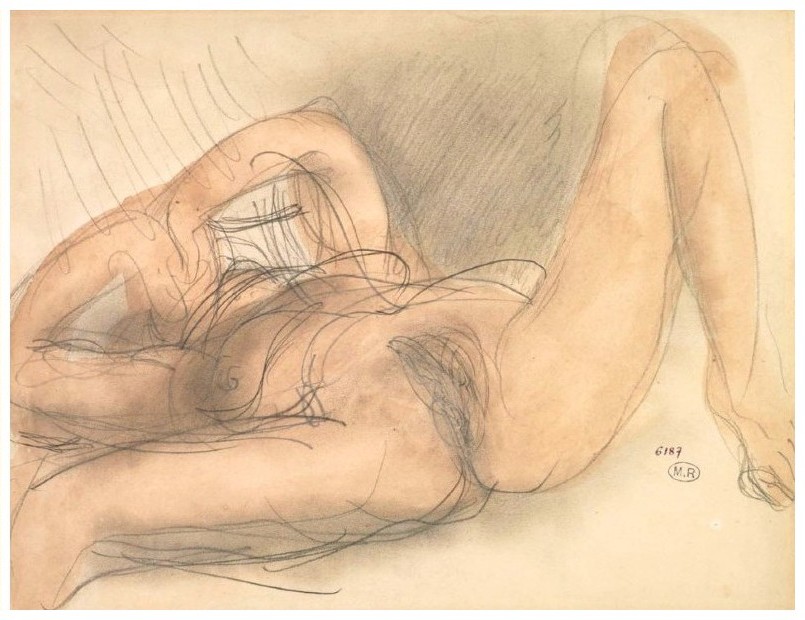

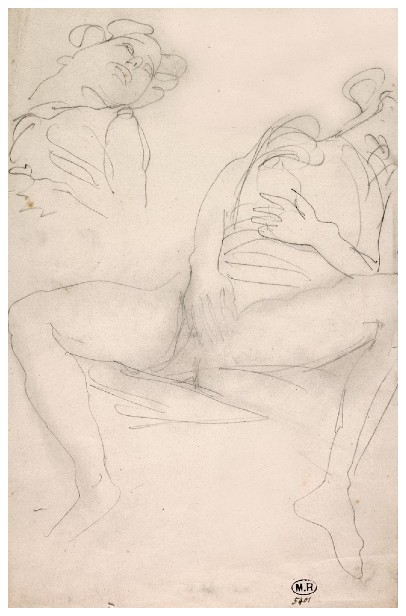

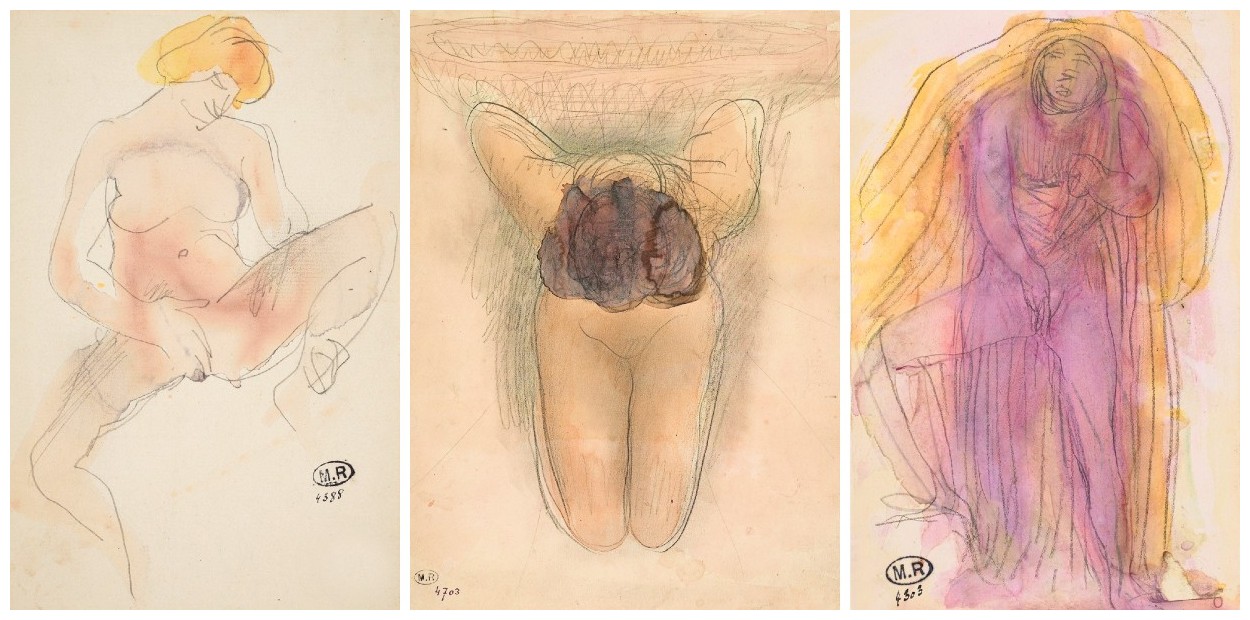

Rodin, Femme nue, cuisses hautes et écartées

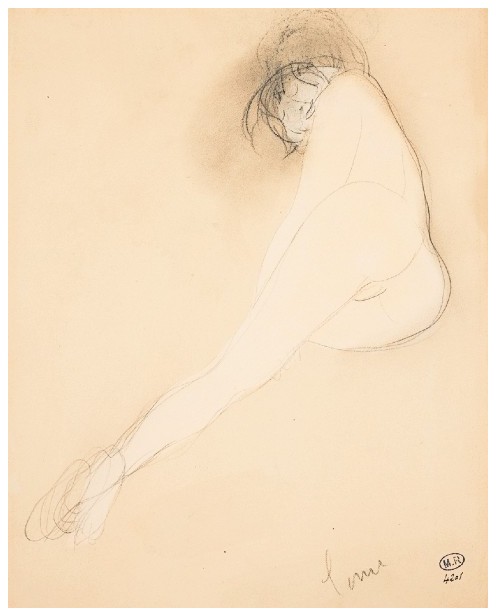

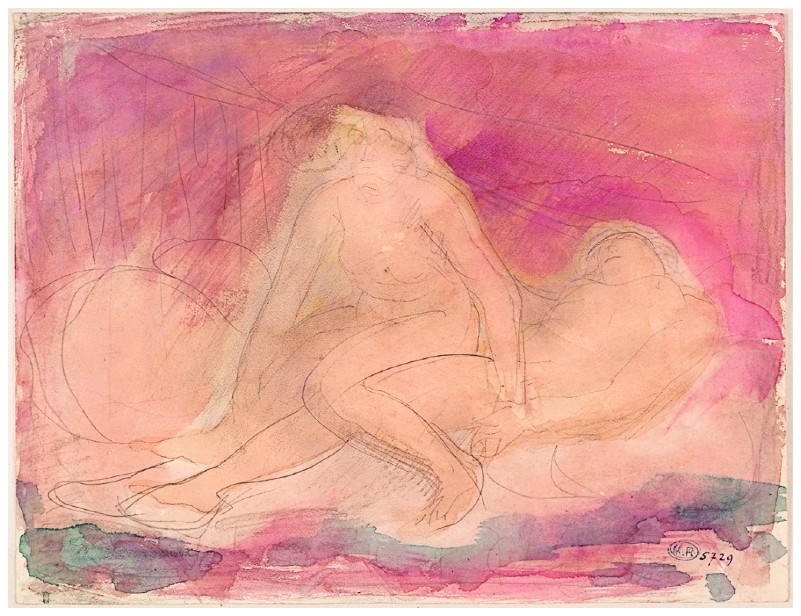

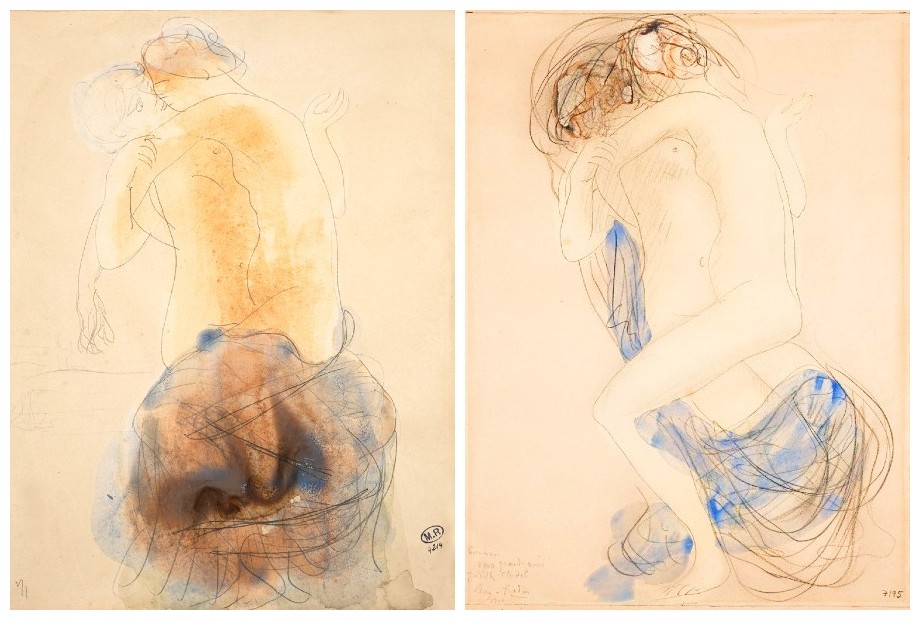

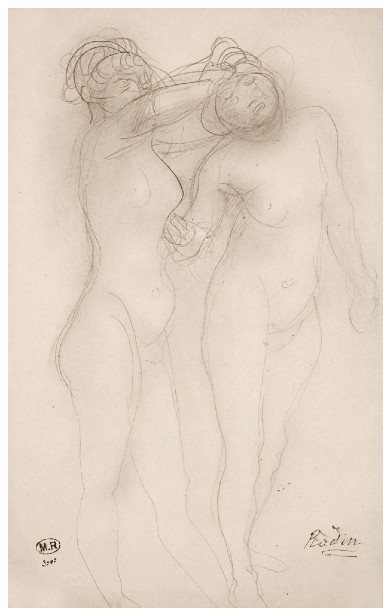

They contain the boldest and most frequent representations of sexual display, masturbation, and lesbian intimacy in the artist’s oeuvre; and, at the same time, everything about their conception—the random, unposed motion Rodin encouraged in his models, the rapid-fire way he initially drew without looking at the sheet on which he was working, and the extreme simplicity of the one-line contours and one-tone watercolor wash—seems to embody aspirations toward purified simplicity, and spontaneous freedom from convention, that are central to early modern ideals of art’s power to refresh our vision of the world.

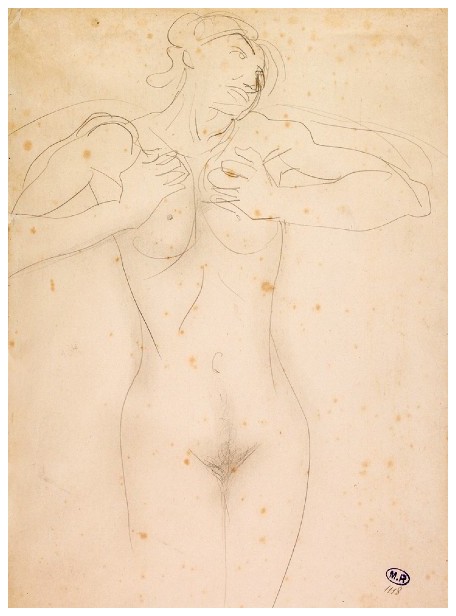

Rodin, Femme nue debout, se pressant les seins, 1900

The erotic in these works is as much a part of the dream of its time as of the specific inner history of its author. If we rethink the relation of these innovative images to the earlier drawings that most fully record Rodin’s development and education as an artist, we can establish a subtler set of linkages between Rodin and Freud, and also connect Rodin’s later focus on the erotic with the motivations of Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat, and others, stressing a powerful, shared conviction central to early modern ideals: the conviction that a powerful new art was to be made neither by merely imitating the ideal forms culture gave us from the past, nor by rejecting them entirely, but by rediscovering their truth in forms of immediate experience that had previously been marginalized or thought too ephemeral and chaotic to bear any significance.

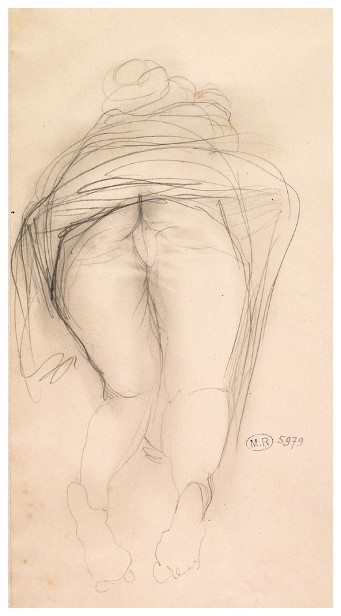

Rodin, Femme à quatre pattes, vêtement relevé

Poses in these life drawings originate in random movement, in patterns of instinct and spontaneity. Yet such works do not simply bespeak a frivolous escape from concern for human meaning. They constitute instead a declaration of belief, highly consistent with the time of their creation, that the basic significance of life is latent in its ephemeral, seemingly random, and unguarded manifestations. As early as the later 1870s, when he rejected Michelangelo’s poses in favor of studying without prejudice his models’ natural movements, Rodin implicitly affirmed that one does not equal the past by imitating it, and that the secrets of great creations must be rediscovered at their source rather than in venerated representations. Freud’s contemporaneous understanding of the significance of the apparently arbitrary, and his belief that the inherited representations of myth and religion are only reflections of basic human experiences recoverable from our own unconscious lives, are also relevant here. Indeed, Rodin erotic drawings deal with the natural energy of movements determined in subjective centers beyond the reach of social discipline, historical memory, or constraining doubt.

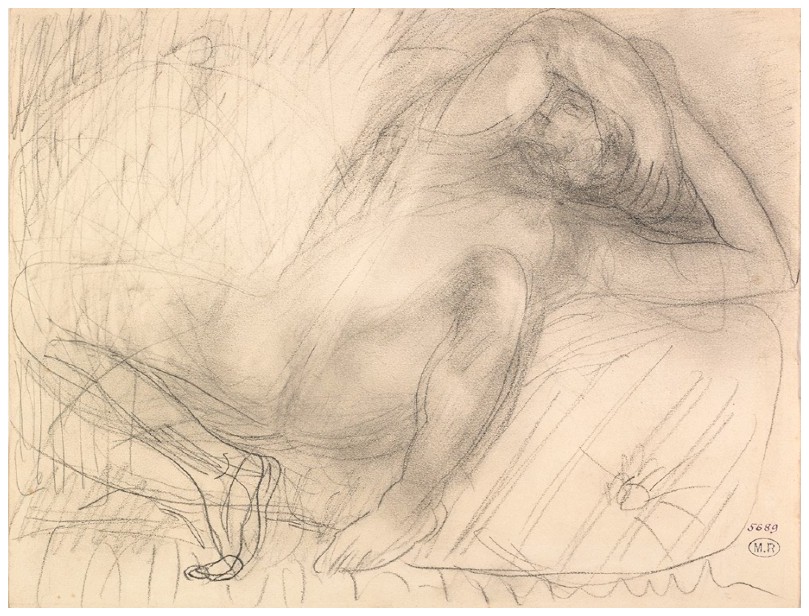

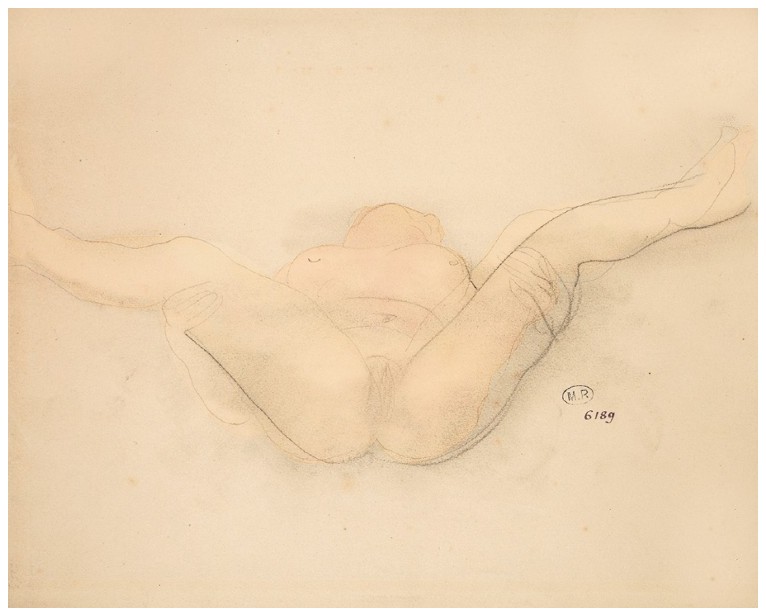

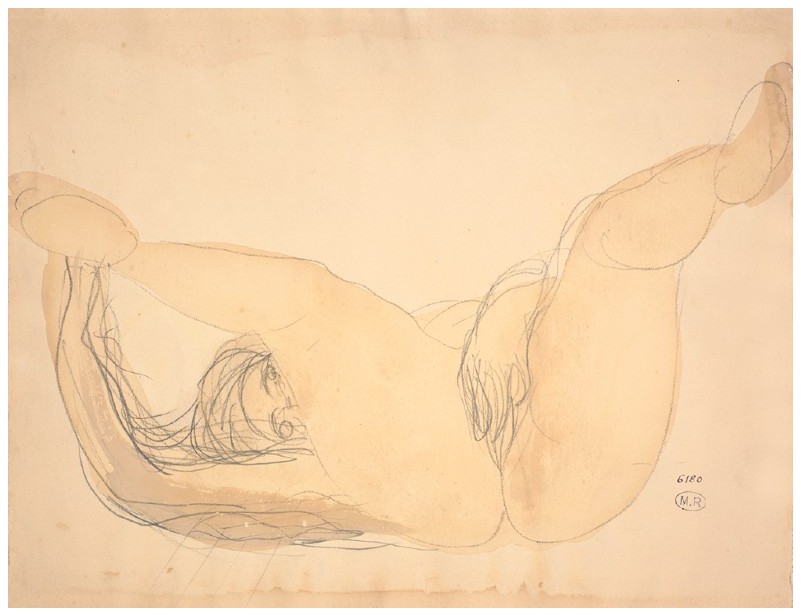

Rodin, Femme nue allongée aux jambes écartées

The nudity of the figures, purified to extreme simplicity, is an invented correlative of the freedom of uncensored instinctual life, not just in the models but also in the artist. The reduction of means and the renunciation of analysis in favor of dynamic summary, permit the unconstrained flow of the artist’s hand and the participation of his own instinctive gesture in response to the model’s. Rodin’s erotic drawings portray a feminine, labile world of unrestrained feeling and liberated, omnidirectional movement; the poses show forms of self-caress that manifest narcissism and the unchecked flow of erotic energy. The imaginative world here is that of the pagan, pseudo-Edenic in its celebration of unashamed sexuality. The realm of the mind, of the museum, of inherited culture is replaced by the false garden of the artist’s studio, the privileged space in which the cloaks of society can be removed and fundamental truths enacted. The artifice of this naturalness is constantly written between its lines, nudity and gesture now deriving from the context of performance, the artist’s presence, and the figures’ unconcealed roles as models.

Rodin, Femme nue étendue, une main au sexe

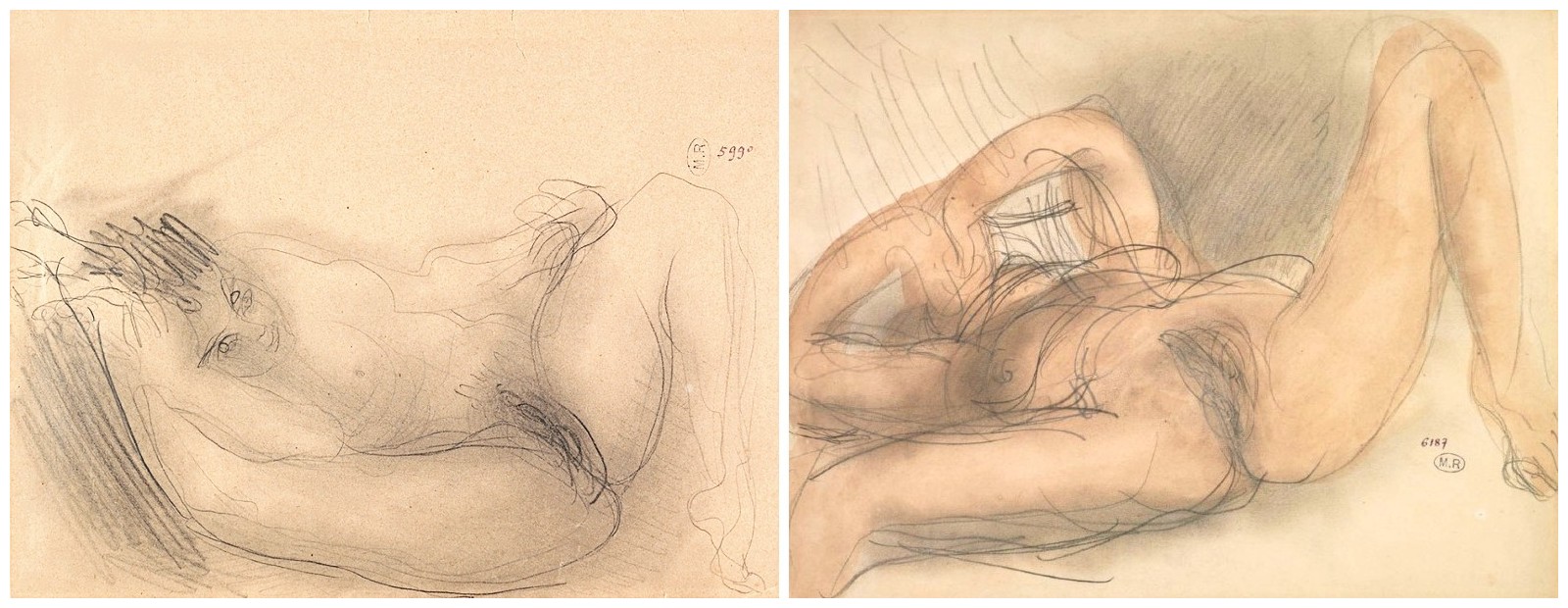

In these drawings the movement of the body and the manner of its presentation refer together, in league, to a belief structure regarding the appropriate concerns and purposes of art and the role of the artist’s mind in creating it. In their celebration of unconscious immediate experience, these Rodin drawings, seemingly casual and licentiously playful, only assume their full valence when taken in the multiplicity of their production, with the principles of their conception understood. Indeed, taken individually, many a late erotic drawing by Rodin may seem the titillating self-indulgence of a voyeur. When the drawings are seen in great number, though, the frequency of such investigations acts to change their meaning, and it becomes clear that these are only more pointed instances of the consuming erotic curiosity that is a mainspring of the entire mode. The nude women in the later drawings wheel, dance, and stretch in a dizzying kaleidoscope of poses, with a seemingly inexhaustible inventiveness of movement; but again and again, this freedom of motion pivots around, and refers to, the fixed axial center of their sex.

Femme nue sur le dos et de face, bras et jambes repliés et écartés

In a sequence of drawings, this centering phenomenon can be surprising. In several hundred, it becomes impressive. In several hundred more, and several hundred more beyond that, it can become by turns astonishing, tedious, numbing. Finally, passing from sheet to sheet through these later watercolors and drawings, in day after day of research, over hundreds of drawings after hundreds of drawings after hundreds of drawings drumming with unrelenting insistence on this same note of sexualized vision, I find all my skepticisms defeated, inadequate, and I am moved. These are not documents of idle self-indulgence, but of heated, driving fascination: they show, in the spirit of the aging artist, an ecstatic obsession with the mystery of creation taken at its primal source.

Rodin, Femme nue sur le dos, maintenant les cuisses écartées

II. GLORIOUS LUST: RODIN’S EROTIC DRAWINGS

ALINE MAGNIEN

Condensed from Aline Magnien, Rodin et l’érotisme (Paris: Hermann / Musée Rodin, 2016) pp. 93-100). Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

‘Glorious lust’ is a phrase from the ‘Bad Blood’ section of Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell.

See Arthur Rimbaud, Rimbaud Complete: Poetry and Prose, tr. Wyatt Mason (NY: The Modern Library, 2003) p. 196

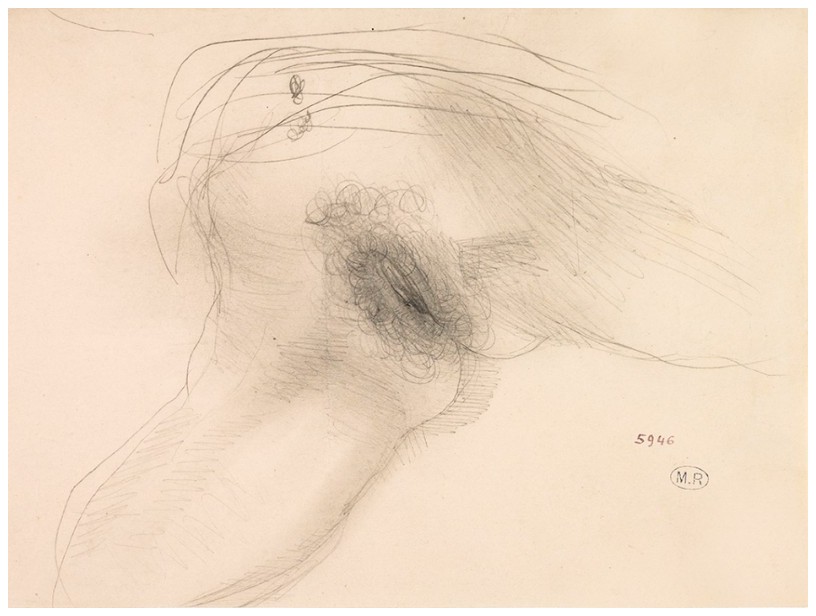

Rodin, Sexe de femme

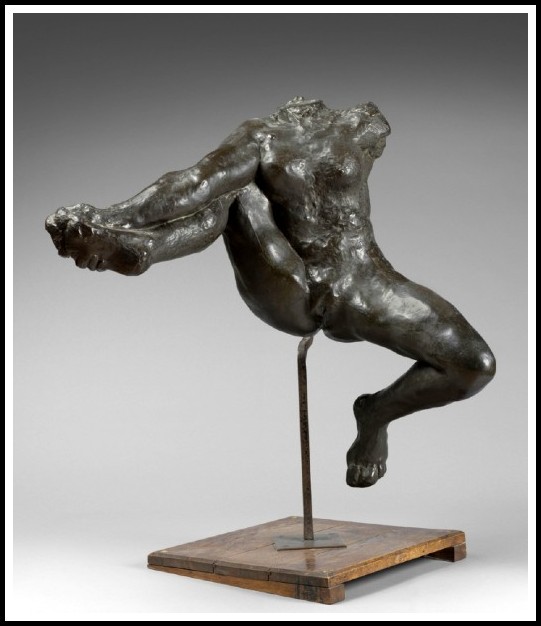

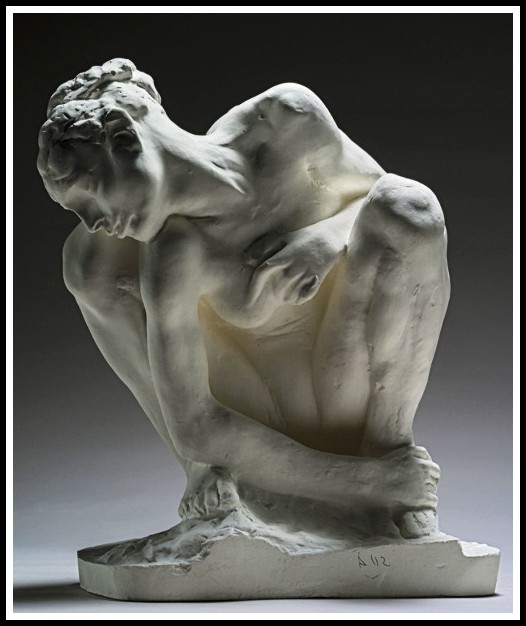

Iris, Messenger of the Gods, also known as The Eternal Tunnel, was designed to crown the monument to Victor Hugo—another great creator, another great lover of women. This dancing figure with legs wide-spread is more a body in ecstasy than a divine messenger; it could well be displayed in a supine position. The work is transgressive not only in its attitude and what it reveals of a woman’s sex,1 but also in its size and what it suggests. The sex act is inherently irrepresentable, and the female orgasm, which Rodin also tracks in his ‘erotic drawings’, even more so. The gaping openness of the female sex, that ‘craving vacancy’,2 that ‘hole’ inter feces et urinam, is also the site of a pleasure that, ever since Tiresias, we imagine irrepresentable in its intensity. With the disenchantment of the world, the art of the nineteenth century took ‘the path of the presentation of Absence’.3 No more than desire or jouissance4 can this ‘metaphysical vacancy be placed on a pedestal and presented’.5 In its own way, however, that is exactly what this Eternal Tunnel attempts to do. Its searing intensity is what founds the sculpture’s modernity. Indeed, ‘for the first time, we see firm flesh resolve itself into a symbol of perpetual flux. Rodin’s anatomy is not the fixed law of each human body but the fugitive configuration of a moment. And the strength of the Rodinesque forms resides in the irresistible energy of liquefaction, in the molten pour of matter as every shape relinquishes its claim to permanence’.6 The absence of the face and of one of the arms concentrates the expression in the body and foregoes the anecdote to go straight to the essential.

1 – The medical ring of ‘genitals’ being dissonant in this context, translating ‘sexe’ as ‘sex’ offers a harmonious contextual equivalent. Indeed, context will make it clear when ‘sex’ refers to the vulva and when it refers to the more common meanings of the term. On occasion, I will translate ‘sexe féminin’ as ‘vulva’. I could also have employed ‘pudendum’, a quaint term that works well in certain contexts, but its etymology—‘the shameful parts’—would contradict the drawings.

2 – I have qualified Aline Magnien’s ‘vacancy’ (vide) with ‘craving’, as Charlotte Brontë’s noun phrase is particularly apt in this context and, I’m convinced, the author, had she known it, would certainly have used it. See Susan Ostrove Weisser, A ‘Craving Vacancy’: Women and Sexual Love in the British Novel, 1740-1880 (NY: New York University Press, 1997) p. ix.

3 – Thierry de Duve, Voici: 100 ans d’art contemporain (Anvers/Paris: Ludion/Flammarion, 2000) p.53

4 – ‘Jouissance’ is defined as follows: “The pleasure principle functions as a limit to enjoyment; it is a law which commands the subject to ‘enjoy as little as possible’. At the same time, the subject constantly attempts to transgress the prohibitions imposed on his enjoyment, to go ‘beyond the pleasure principle’. However, the result of transgressing the pleasure principle is not more pleasure, but pain, since there is only a certain amount of pleasure that the subject can bear. Beyond this limit, pleasure becomes pain, and this ‘painful pleasure’ is what Lacan calls jouissance: ‘jouissance is suffering’. The term jouissance thus nicely expresses the paradoxical satisfaction that the subject derives from his symptom, or, to put it another way, the suffering that he derives from his own satisfaction.” Abbreviated from Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (Routledge, 2001) pp. 91-92

5 – Thierry de Duve, op. cit., p. 53

6 – Leo Steinberg, Other Criteria: Confrontations with Twentieth-Century Art (University of Chicago Press, 2007 [1972]) p. 325

Rodin, Iris messagère des dieux, 1895

This spread-eagle posture ‘exposes the woman to the violence of sexual play’, to use an expression of Georges Bataille. The posture in its bestiality, its toad-like stance, entails a defilement of the gaze and a fantasized penetration: Iris skewered on an iron rod. The devouring woman of whom only a mouth remains—the one between her legs—appears ‘supernatural’ and, from a Baudelairian perspective, even more disquieting and abominable. Over a twenty-year period, from 1890 to 1910, the vulva is omnipresent not only in Rodin’s drawings but also in his sculpture. This corresponds to the taste of his time, as seen in the popularity of shunga (Japanese erotic prints), and to the erotomaniacal obsessions expressed in books like My Secret Life, where the narrator pays prostitutes for nothing more than the pleasure of gazing at their vulva. Arthur Symons,1 in the special issue of the literary review La Plume devoted to Rodin in 1900, wrote: ‘The principle of Rodin’s oeuvre is sex, a self-conscious sex that employs the energy of desperation in a bid to attain the impossible’. Speaking of La Porte de l’Enfer, ‘that flight and impetuous fall’, Symons evokes ‘all that painful and tortured flesh consumed by desire’. And in his Confessions, Aleister Crowley, the English occultist, wrote: ‘Rodin had no intellect in the true sense of the word; his was a virility so superabundant that it constantly overflowed into the creation of vibrating visiions’.2

1 – Arthur Symons (1865-1945) was a noted poet, critic and magazine editor who did much to promote the French Symbolists in the English-speaking world.

2 – Aleister Crowley, The Confessions of Aleister Crowley: An Autobiography, ed. John Symonds & Kenneth Grant (London: Penguin Books, 1989) p. 339

Rodin, Femme accroupie (petit modèle), 1880-81

The relation between Rodin’s erotic work and Courbet’s L’Origine du monde was highlighted in the exhibition ‘Cet obscur objet de désirs: Autour de l’Origine du monde’.1

1 – Musée Courbet, 7 June-1 September 2014 (Ornans, Le Doubs)

Gustave Courbet, L’Origine du monde, 1866

From a formal point of view, however, there is a fundamental difference between Courbet and Rodin: Rodin’s women, at least in the majority of his drawings, have faces. In Avant la création, for example, the open mouth, the head thrown back, suggests the orgasm Rodin is trying to capture as he draws the woman abandoning herself to pleasure before him. They may be barely recognizable at times—these are not portraits—but they are always differentiated.

Rodin, Avant la création

Indeed, these women who masturbate before Rodin, spreading their labia that the gaze may more readily enter, are not absent from the scene but present, actively participating in it.1 Their face is there, with different features and expressions, and if it is not the expression of pleasure that one finds on it, it is the pleasure of the spectator looking at the forbidden sex or the pleasure experienced.

1 – We may wonder, looking at drawings such as these, what were the exact circumstances of their creation, and we cannot exclude the possibility that some of them were done in brothels, especially since a sculptor’s studio is cold and humid and does not lend itself to intimacy.

Rodin, Femme nue allongée aux jambes écartées

In the drawing Femme allongée et de face, une main sur les jambes écartées, a depiction of a woman masturbating, the woman’s face makes evident what interests Rodin: the capture of feminine pleasure.

Rodin, Femme allongée, main sur sexe, jambes écartées

The question of women’s sexual pleasure was a common topic in medical debates at the time.

Rodin, Naissance de Vénus, 1901

The theme was also common in contemporary literature, where ‘woman’, cold and self-sufficient, was assimilated to the moon. Feminine narcissism, of which lesbianism is an aspect, was highlighted in this context.

Rodin, Lune, 1898-1908

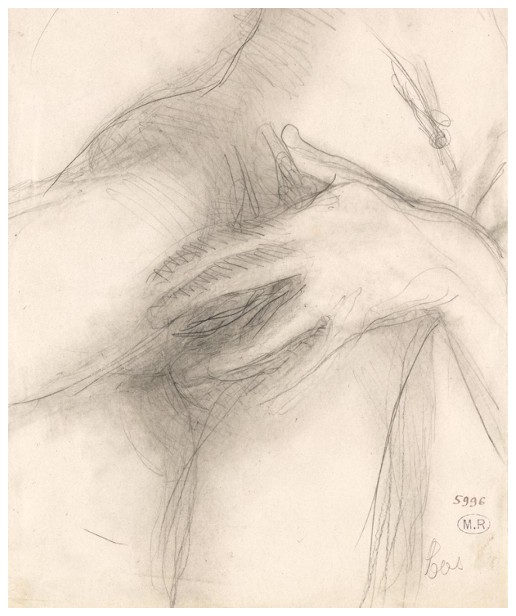

Feminine sexuality, that dark continent of which Freud spoke, became a field of study, and masturbation an object of psychological investigation and discourse. It became a means to treat hysteria, for example, with the ‘paroxysm’ it provokes coming to crown the doctor’s efforts. The vibrator, invented by English physician Joseph Mortimer Granville in the late 1880s, became a means to accelerate the treatment.1 During the same period, French law remained vague on what constituted an affront to public decency. Artists, while being aware of the subversive nature of certain representations, nevertheless enjoyed a measure of leeway regarding what could be represented or not. If women masturbating abound in Rodin’s drawings, the same does not hold for his sculpture. Even in the drawings, close-ups of the hand or the vulva alone are relatively rare.

1 – This assertion, though widespread, has been debunked. See ‘A Failure of Academic Quality Control: The Technology of Orgasm’.

Rodin, Main sur un sexe

Writers who have written on the ‘erotic drawings’ adopt different positions towards them. Camille Mauclair, for example, considered Rodin a quasi ‘zoologist’ of the female sexual apparatus, thus relegating him to a domain where the drawings would be less emabarrassing.1 Other writers—Catherine Lampert, for example—have highlighted the metaphysical quest that underlies the drawings, arguing that it is based on the question of the other: ‘What the aging Rodin is desperate to discover but cannot, as he realizes, is to “know” what it feels like from the other side. What sensations female languor, lust, lesbian pleasing, manual stimulation and finally ecstasy are comprised of. His work manifests his own libido and the animal beauty of women, but that is all.’2

1 – Camille Mauclair, Auguste Rodin, L’homme et l’oeuvre (Paris: La Renaissance du livre, 1905) pp. 91-93

2 – Catherine Lampert, Rodin: Sculpture and Drawings (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986) p. 171

Rodin, Femme nue sur le dos, de face, une main retenant un pied et l’autre sur le sexe

III. RODIN’S SECRET: THE EROTIC DRAWINGS

PHILIPPE SOLLERS

From Philippe Sollers, La Guerre du Goût (Paris: Gallimard, 1996) pp. 112-122. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

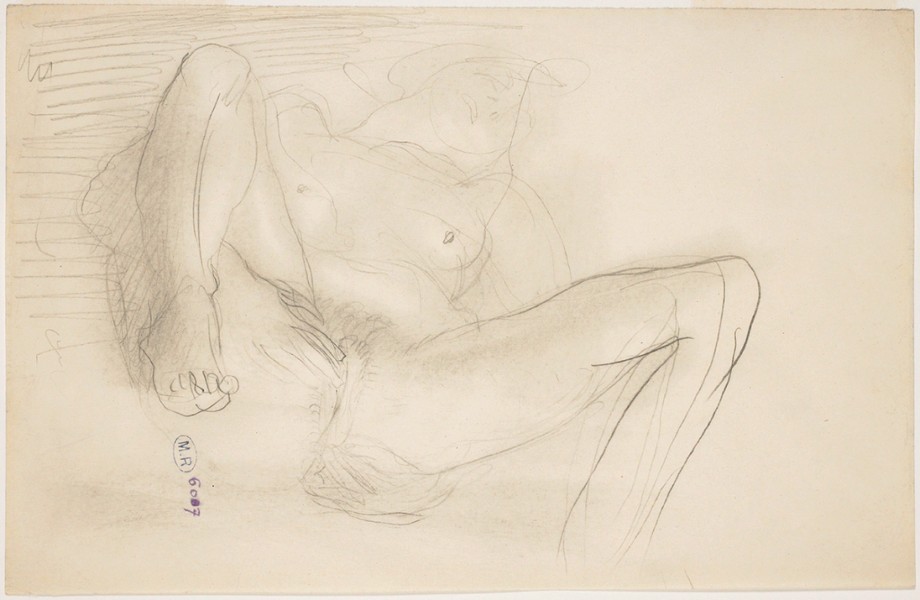

They were spoken about, one knew they were there, somewhere. Certain were seen here or there, but it was difficult to imagine them grouped for attack, forming a breach like no other in the representation of bodies. Here they are, then, these drawings. I believe one should imagine them as the true light of the sculptures scattered across the night, the true light of a darkroom revealing the meaning of the twisted bronzes and plasters in the museums, the gardens, the streets. What is The Thinker thinking about? That. What is Balzac—leaning back, closed in upon himself—contemplating? That. What do The Gates of Hell open out onto? That. What is Victor Hugo dreaming of, what is it that he cannot speak of? That. Where do so many busts and hands, legs and gestures, sinewy couples, tense faces, impetuous demi-gods and goddesses come from? From that. Yes, from these singular-plural women in an extreme situation, discovering in movement their sex, oblique or full frontal, directing a hand to it. And thus Medusa is stared down at last by a radical explorer and outlaw: the usual suspect, a Frenchman, focused and steadfast in the ambient regression. Propriety outside his restricted studio, furious action within. Is it any wonder the results could only be shown much later?

Rodin, Femme nue aux jambes écartées

With the hôtel Salé-Picasso, the hôtel Biron-Rodin definitively makes Paris the mysterious city. Sade, Baudelaire and Proust approve this construction. You who enter Paris, abandon all hope of learning more elsewhere: It is here, and only here, that lust comes under such scrutiny. Get yourself locked into the Rodin Museum at night. The Eiffel Tower and the Invalides will whisper to you, in the shadows, all manner of crude, venomous noises: the Serpent will be there. Paradise lost—you will learn why it can be regained through its inverse.

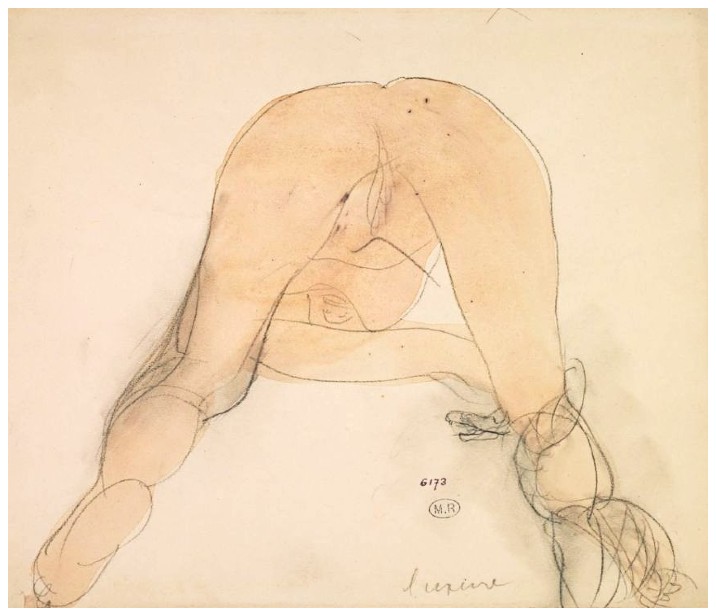

Rodin, Luxure

Do not forget against what these drawings are done: puritanical folly, the persistence of repression behind its passing disguises, the climate of opinion, journalism, Queen Victoria, modern style, the decorative turn of the turn-of-the-century, politics, advertising. And for what: in an ocean of lies, to keep the goal in sight. These positive incisions are there to allow the secretion of the precious, forbidden substance, the auto-erotic hormone that gives one the right to immediate consumption of all possible women, equivalent to all the other standing, modeled or cast bodies. Old Rodin? Old Picasso? Old Matisse? Here they are breaking the law of laws: biological prejudice. Never have they been younger, or rather: Satyric youth is only achieved by the delegation of a deep-seated energy, one without age, using pencil or brush. It’s not easy to become a god. Youth, so often insipid, inhibited, is only the shadow of potential divinity. When Rodin wanted to deliver Iris, Messenger of the Gods, he had her at hand, on his examination table. ‘A God’, Epicurus said, ‘is a happy, indestructible animal’. Rodin, like Picasso and Matisse after him, knew why and how he became, very late, ‘a happy, indestructible animal’.

Rodin, Deux femmes nues, l’une assise et l’autre allongée

Rodin is standing or kneeling, or lying beside them. He steps aside, he encourages them, he steps forward. What a musician! What a director! They show him what they show no-one else: their true nature, their wild abandon. He leans over. He entwines them. He asks them to masturbate—and no faking it! To make love with each other. To do it upfront, fearing neither disarticulation nor convulsion. He takes note of their spasms. Never before has that been seen. It will take no less than a pillar of Notre-Dame to counterbalance that! Or else brickloads of German philosophy. He exalts them, turns them over, drowns them; he gives them electroshocks. Nereids, nymphs, naiads? Yes, yes, but first they are working-class girls or mundane bourgeoises, hurrying to his studio and suddenly inhabited by that. It’s Dionysus in Paris, in the seventh arrondissement, under the nose of the Establishment’s police. They come in many guises: hypocritical young girls transformed into practiced whores, mothers lying one atop another, women of the world exhibiting their earthiness, dancers earning their salary, laundresses changed into goddesses. They go to Rodin as to a whorehouse. If these drawings could speak! Listen: they’re speaking: moans, cries, whispers, obscenities, murmurs…

Rodin, Amour et Psyché sortant d’un lotus | Deux femmes enlacées, 1908

Who is he, then, this Rodin, who obliges women to desire themselves, to strip off their clothes and touch themselves as they twist and turn before him? To come in his presence as he draws them? To offer themselves up as desire consumes them? To reveal, to be unable to conceal, the fire whose flames never die? He is, of course, a sculptor of genius, a prodigy of modelling–a handy man–but is that all? Why do women, like wild sleepwalkers, converge upon this point? What point? There’s no question here of making Rodin, even if it were the case, a man of good fortune, a sexual maniac, drawing toward him, almost mechanically, his maenads. In painting, especially with Picasso, we know how far the situation of the painter and his model can go: The canvas is penetrated, the landscape or studio turned upside down, the painter and his nude model embrace in an embodied brushstroke. With Rodin, nothing of the sort: He is not there—no man is or will be there. He is exempted from playing a visible role in the physiological script. It is from themselves that these women seem to draw their irrepressible confession.

Rodin, Couple de femmes nues, allongées et enlacées

A forgotten language speaks in Rodin: ‘Surrender, Juliette, surrender without fear to the impetuosity of your tastes, to the cunning variability of your caprices, to the fiery spirit of your desires; arouse yourself on their deviance, intoxicate yourself on your pleasures; take them for your sole law, have no other guide; may your voluptuous imagination vary our dissoluteness; it is only by multiplying them that we will achieve happiness. Don’t you see the star that shines upon us desiccating and invigorating by turns? Imitate it in your profligacy, as you paint it in your pretty eyes.’

RODIN

Femme nue assise, jambes écartées, main au sexe | Femme nue agenouillée, penchée en avant, mains derrière le dos | Femme nue debout, la main droite au sexe

And indeed, why not Coquille (D5990), as a portrait of Sade’s Juliette? The left leg is in the same position as in D6187. One must imagine what happens from one to the other. Rodin died in 1917. On the horizon of his erotic drawings are two world wars and unprecedented destruction. Rodin’s secret, hidden in his private works, stands the test of time. His secret is our secret.

RODIN: Coquille (D5990) | Femme nue sur le dos et de face, bras et jambes repliés et écartés (D6187)

IV. RODIN’S EROTIC DRAWINGS IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel, ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 15

When you surprised yourself in the mirror, when you became a stranger to yourself, who was the who you dreamt yourself to be?

̶ Mirror, mirror, tell no lies, how do I look in Rodin’s eyes?

̶ On cream-coloured drawing paper, in black lead and blending stump, you lie on your back with your legs apart. One hand is reaching up from under your buttocks, the other is rounding your raised thigh: Each is intent on satisfying your insatiable sex. Look! The line springs and swells as abandonment floods your body and your head fades away: Intimately feeling what the eye sees, the hand of the artist flows unconstrained…

Auguste Rodin, Femme nue sur le dos, les mains au sexe et les jambes soulevées

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 14

Should it rain, upon a Sunday afternoon, you’d cross the rue de Varenne to visit a gallery or two in the musée Rodin. You admired Rodin’s genius, but his sculptures never really moved you: It was the drawings, the erotic drawings, that touched you. Picasso’s were crude and illustrative in comparison to the evocative power of Rodin’s. In the pressure of his pencil you felt the touch of the sculptor’s hand; in the freedom of his line you felt the fascination of his desire.

Rodin, Femme nue allongée, jambes écartées, mains au sexe

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 15

̶ Diego, Isabelle, I’d like you to meet Marietta and Sprague.

There’s wisdom in her eyes, the blue sparkles with intelligence; from her sensual mouth the words come, trippingly on the tongue: She’s a psychoanalyst, she’s written a book on love.

̶ I could use your services, I say, but I fear if I did, my hand would no longer fit the glove.

̶ What glove?

̶ The one I wear to tell my story in shadows on the wall.

She gives me an enigmatic smile. In her stretch-leather pants and fetish boots, she is Eros with a death wish.

̶ It seems I’ve made my bed, Isabelle, and I’ve simply got to lie in it.

In the ice blue of her eyes, something melts: Would she lie with me in my bed, or want me on her divan? You jump in with a question for Diego:

̶ Would you agree that Picasso’s ceramics are the best things he did since Guernica?

Diego, a potter by day and a drummer by night, answers:

̶ I would. He lost the spark after that. Except for the erotic drawings!

̶ I find Rodin’s more moving.

̶ So do I, says Isabelle.

Again, the enigmatic smile. And then Adelaide returns to move us on.

Rodin, Deux femmes nues, l’une tenant l’autre aux cheveux