Brancusi: Mademoiselle Pogany | Bird in Space

I. BRANCUSI & MARGIT POGANY | II. BRANCUSI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’: MADEMOISELLE POGANY | III. EZRA POUND ON BRANCUSI | IV. BRANCUSI’S BIRDS: MATERIAL & TECHNIQUE | V. BRANCUSI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’: BIRD IN SPACE

I. BRANCUSI & MARGIT POGANY: A RESTRAINED LOVE

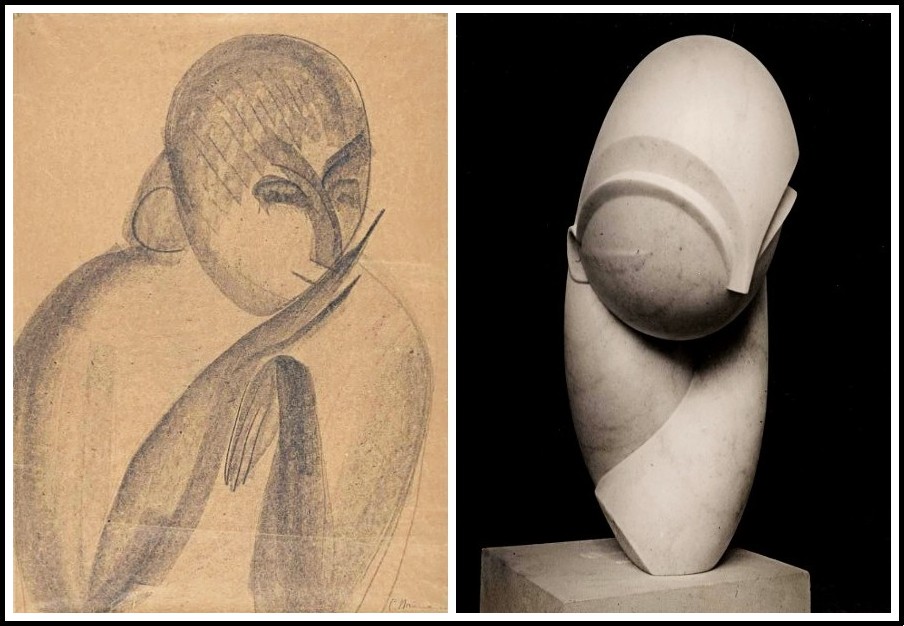

Mademoiselle Pogany

DOÏNA LEMNY

Abbreviated from Doïna Lemny, Brancusi et ses muses (Paris: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2023) pp. 34-45. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

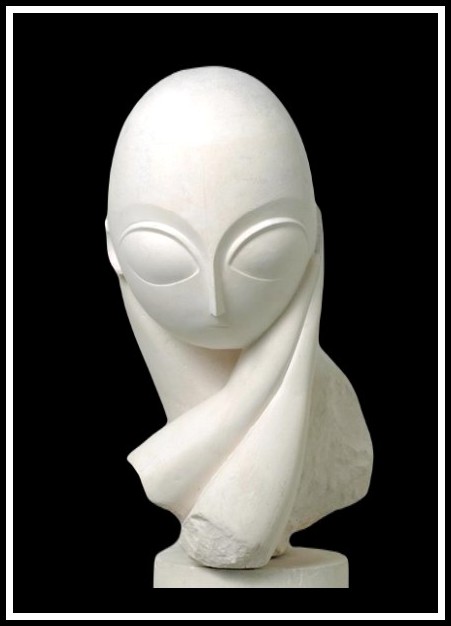

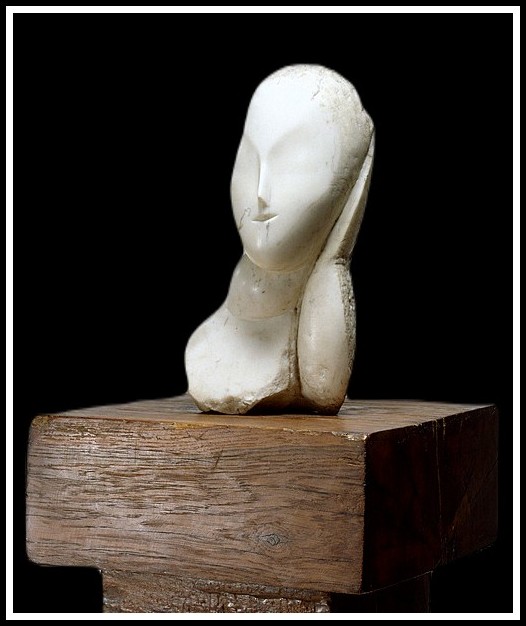

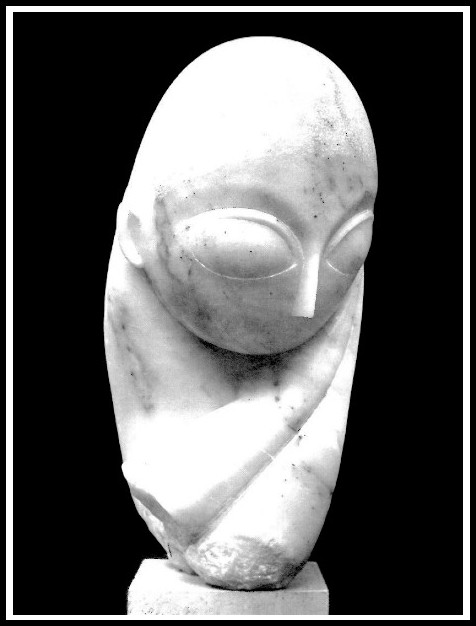

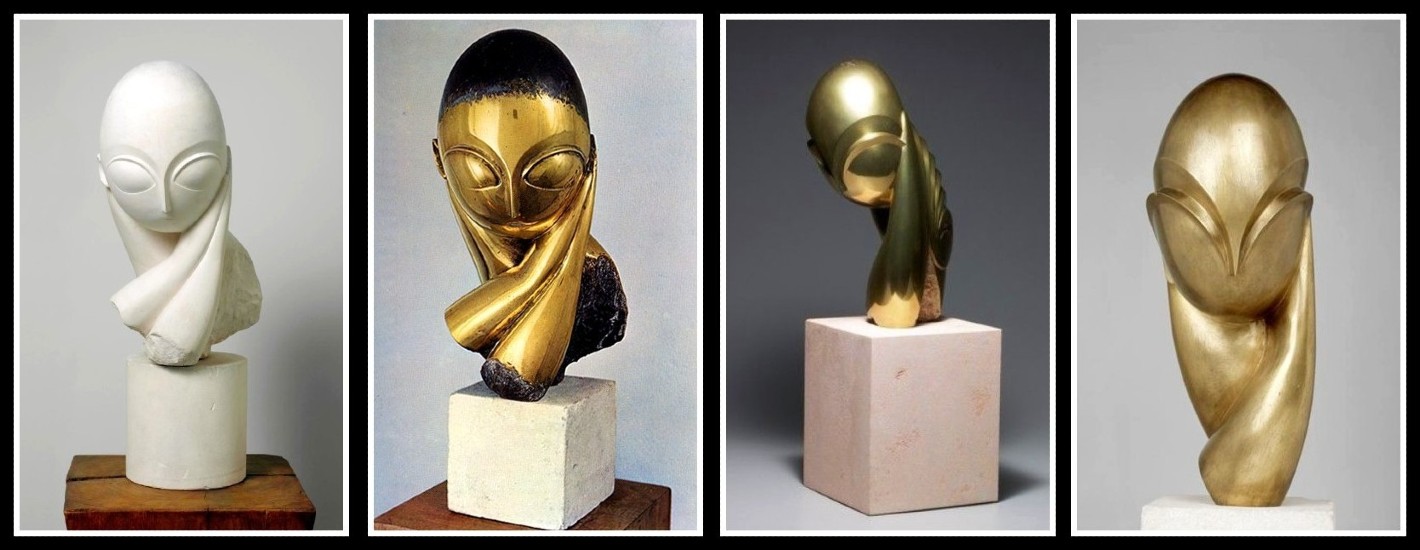

Mademoiselle Pogany, one of Brancusi’s most representative works, has become the modern icon of the bust of a woman. Right from its presentation at the 1913 Armory Show, the International Exhibition of Modern Art in New York, the bust has drawn the attention of both the press and the public who, in their puzzlement, ridiculed it. Concurrently, the sculptor, with the titles he gave his busts of women—Sleeping Muse, Danaïde, A Muse—totally effaced the identity of the women who served as his models. The works express an image of the ideal female portrait, evoking a woman’s beauty, the elegance of her bearing, and her mystery. Indeed, all the busts of women that Brancusi sculpted have an enigmatic aura that evokes calm, stability and balance. Mademoiselle Pogany, the bust that Brancusi sent to the Armory Show, is a fine example of this. The model’s physical features give way to the wide-eyed stare of exorbitant eyes, while the tilted oval of the head supported by the elongated neck amplifies the intensity of the inward-turned gaze. Failing to please, the work intrigued, and became, with Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, the most decried work of the exhibition, thus inaugurating its enduring fame. Right from the start, its great modernity meant that it could not be associated with the portrait of an identifiable woman in the artist’s milieu, or even give rise to a search for resemblance to anyone at all. This no doubt explains why contemporary critics considered the bust an abstract work.

Brancusi, Danaïde, 1913

For this reason, one may wonder why Brancusi titled his bust Mademoiselle Pogany, a name that evokes Margit Pogany, a Hungarian painter. Did she pose for him or did he simply observe her during her visits to his studio? And how did Brancusi respond to her during those visits? The relationship between the two remains ambiguous, shrouded in a veil of discretion. The few letters in the archives contain nothing precise about a possible love relation between the sculptor and the painter. In 1910, the date Pogany gives of her first visit to Brancusi’s studio, both artists were in the prime of life, Brancusi 34 and Margit 31.

Brancusi, Mademoiselle Pogany, 1912-13

Born to well-off parents in Budapest, Margit Pogany studied painting with Lucien Simon in Paris, staying in an apartment close to Brancusi’s studio. In July 1910, accompanied by a friend, she visited Brancusi for the first time and saw the sculptures he was working on. Three years earlier, in 1907, Brancusi had abandoned modelling and taken up direct carving, which offered him greater freedom of interpretation and the possibility of true dialogue with the material. In July 1910 he finished the bust of the baroness Renée Irana Frachon that became Sleeping Muse and A Muse. After a preliminary study in clay and another in stone, he conceived a figure, bearing no direct likeness to the model, that evokes his desire for a balance between particular and ideal form.

Brancusi, A Muse, 1912

Several other works, still in their early stages, awaited completion. Margit: ‘Among them was a head of white marble which attracted me strongly. I felt it was me, although it had none of my features. It was all eyes. I looked at Brancusi and noticed that while he was speaking to my friend, all the time he was slyly observing me. He was awfully pleased that I had recognized myself. (Later he gave me a photograph of the head)’.1 The sculpture she had noticed was probably Narcissus (1909-10), a head in alabaster that Brancusi would take up again in working on La Fontaine de Narcisse, which, however, he would never develop beyond the study stage.

1 – Margit Pogany, letter to Alfred H. Barr, Director of MOMA, 1952. Cited in Sidney Geist, Brancusi: A Study of the Sculpture (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1983) p. 190

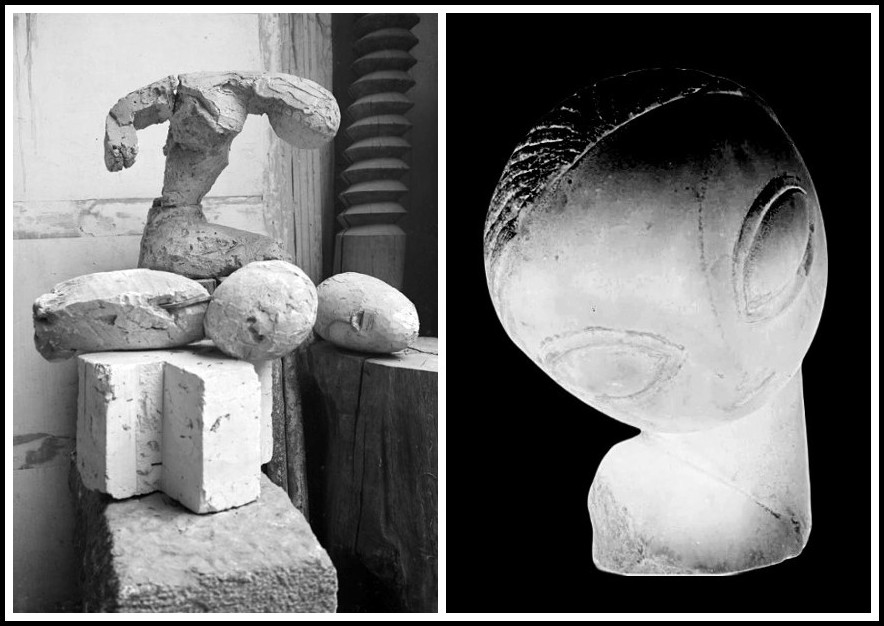

BRANCUSI: Project for Narcissus Fountain, 1910-13 | Narcissus, frontal view, 1910 (photograph)

After several visits and conversations, and after having realized that Brancusi was ‘a real artist, striving hard to find his own self, striving to find the expression for his own conception of art which differed greatly from that of others’,1 Margit let Brancusi know that she would like a bust of herself and offered to make available to him the funds he would require for this. Having observed her during her visits, and stimulated by the fact that she had recognized herself in his Narcissus, Brancusi set to work. Taking up the tilted-head position of the mythological character, he adapted it to the depiction of this young, wide-eyed woman. Margit recalls that she posed for him several times. He made several clay studies that he subsequently threw out, much to her regret, as she was happy with the likeness he had rendered. Once, she recalls, she posed just for her hands, simply because Brancusi wanted to commit them to memory, as he had her face.

1 – Margit Pogany, letter to Alfred H. Barr, Director of MOMA, 1952. Cited in Sidney Geist, Brancusi: A Study of the Sculpture (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1983) p. 191

BRANCUSI, 1912: Study of Hands | Bust of a Woman (study after Mademoiselle Pogany I) | Study of Hands

A number of drawings testify to this preliminary work. Contrary to his usual practice of carving directly in marble, Brancusi tried to sketch a portrait of Margit in an attempt to penetrate, via a certain position of the tilted head, the mystery of the young woman’s gaze. The same position is taken up again in his drawings, where he represents her either with her hair loose or drawn back tightly in a bun. The hands play an important role in the composition of his portraits. Either joined symmetrically at the chest or, providing support, forming an angle under the chin, they align in perfect harmony with the arc of the eyebrows and the nose. If for the bust of the baroness Frachon he left out the shoulders, the arms and the neck, keeping only the oval of the head that he lay on its side (hence the title Sleeping Muse), for Mademoiselle Pogany, in contrast, he returned to the classic bust and included all the elements that complete this mysterious head. Brancusi, at this precise moment, had probably not yet found the ideal form for rendering the essential traits—intelligent, calm, curious—of this young woman. He needed time to explore what intrigued him in her, which explains why he could not deliver this generous commission more quickly.

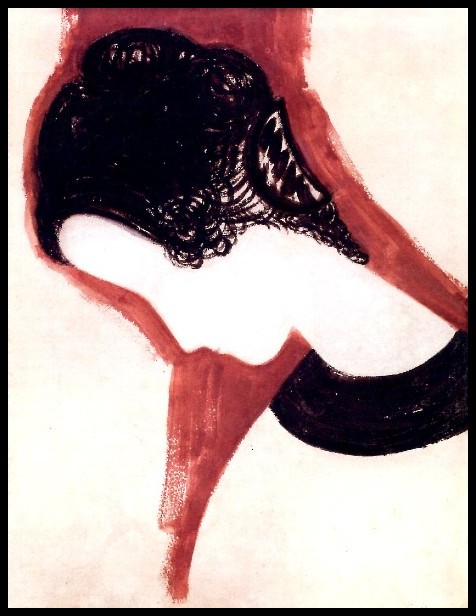

Brancusi, Femme au peigne (Profil de femme au chignon), 1912

In January 1911 Margit, finding Brancusi was getting under her skin, went to Lausanne to take a break from him. She confessed his charm had shaken her, as she explained in a self-questioning letter full of regret and insight: ‘It is not Joy you have given me as a companion, it is one of your Spells. The villain came in the disguise of Joy. I’m beginning to realize that I have left Paris and I’m wondering how I could have done that.’ By gently scolding Brancusi for ‘setting his spell’ on her, Margit, who had taken painting lessons in Transylvania and had exhibited there, is probably alluding to the customs of this Romanian region. Indeed, it was not a rare occurrence in Transylvanian villages to come across someone endowed with the power to cast spells. Brancusi himself cultivated this magic, enacting practices from another time and place that impressed his friends and acquaintances. He was also interested in Oriental cultures, and forged a personal philosophy that he expressed in aphorisms. It is not surprising, then, to find him referred to as a ‘shaman’ or a ‘wizard’.

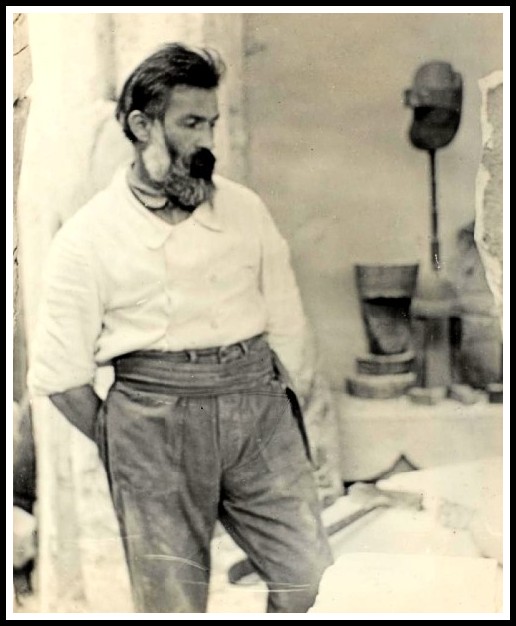

Brancusi, Self-Portrait, 1934

Margit was probably sensitive to the ‘magic’ in Brancusi’s sculptures. This virile little man with a mysterious gaze had opened not only the door to his studio to her, but probably the door to his heart as well. Beset by a thousand doubts, she realized that in leaving Paris she risked losing everything—would she not come to regret her failure to solidify her relationship with the man in whose company she felt so alive? She also reproached herself for telling Brancusi the bust would be for her mother, a woman who, like most people, was bewildered by unconventional art. ‘Let it be for you and me alone’, she wrote him. ‘If the others do not understand it, too bad for them. They might, by seeing it, eventually understand it. And if your conception is so great that I too could not understand it, then too bad for me as well. I know you are so far above me that I must grow if I hope to attain, if not creative power (perhaps I am not capable of it) then at least understanding’. Margit’s admiration for Brancusi was paralleled by a fear of feeling inadequate—how could she possibly measure up to the aesthetic charge of his work?

Brancusi, Head of a Child (Head of ‘The First Step’), 1913-15 & 1917

In January 1911, when Margit left Paris, Brancusi had not yet begun sculpting the bust. Certain that it would be a masterpiece, one that would embody the ‘beautiful’ that Brancusi had theorized in his aphorisms, she was confident it would enable the sculptor to attain his ideal of aesthetic perfection. Indeed, Brancusi subscribed to Plato’s conception of beauty, which maintains that beauty is the outcome of a quest for knowledge and wisdom via love and desire. That, at least, is Margit’s understanding of Brancusi. It is what she must have deduced from their conversations, and she hoped those conversations would continue: ‘You understand, don’t you, that I am not speaking of the ‘beautiful’ in the mundane sense of the term. I have seen very beautiful things, things that no-one else has seen because they are so simple. I had no desire to show them to others, but I would have liked to show them to you’.

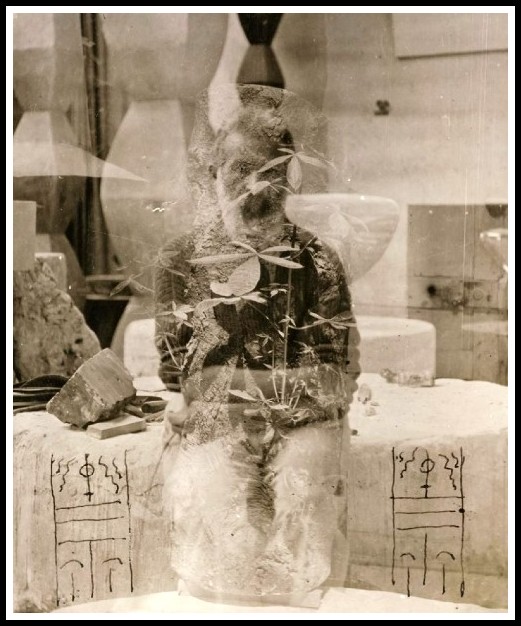

Brancusi in his Studio, 1922

Brancusi’s conflicted feelings about engaging in this kind of exchange with Margit troubled him to such an extent that he developed debilitating psychosomatic symptoms. Margit was concerned and offered advice about alternative medicine. However, the best medicine to cure him, she believed, was Goethe’s poem, ‘Prometheus’. Describing it as ‘a glass of very strong wine’, she wrote: ‘Do not get drunk on it, but do read it when you’re feeling listless and discouraged. It will give you strength and it will show you that a glorious death can’t compete with a courageous struggle. You will no longer think about death, glorious or otherwise.’ The effect of this ‘medicine’ was immediate. Brancusi had been engaged in a process of ever-greater refinement of the busts he was sculpting. Into this long series, represented by Head of a Child and Head of a Sleeping Child, he introduced an astonishing new work.

Brancusi, Head of a Child, 1921 & 1923-24

To this work, first in white marble then in bronze, Brancusi gave the title Prometheus. We see the rounded head of a child with the features reduced to fine allusions to eyebrows, nose and mouth. The ear with its well-defined contours opens toward the top like a funnel, while the rebellious child, in Goethe’s vision, defies and affirms himself against the God who has rejected him.

When I was a child,

Knew not my way out or in,

Perplexed I turned my eye

To the sun, as if there would be

And ear to hear my moans.

A heart such as mine is

Ready to pity those who suffer.*

This poem probably played a triggering role in Brancusi’s life, as it provoked a reckoning with himself. He came to understand that weakness of body and soul is but a passing phenomenon. Like Prometheus, he now understood that, rather than succumb to defeat, he had to get a grip on himself and continue the fight: his mission was to advance by giving form to his ideas. In these moments of doubt, Goethe’s verses went straight to his heart.

And didst thou dream, perhaps

I would hate life,

Fly to the desert

Because not all

Flower-dreams bore fruit?*

* Goethe, ‘Prometheus’, tr. Margaret Fuller

Brancusi, Prometheus, 1911

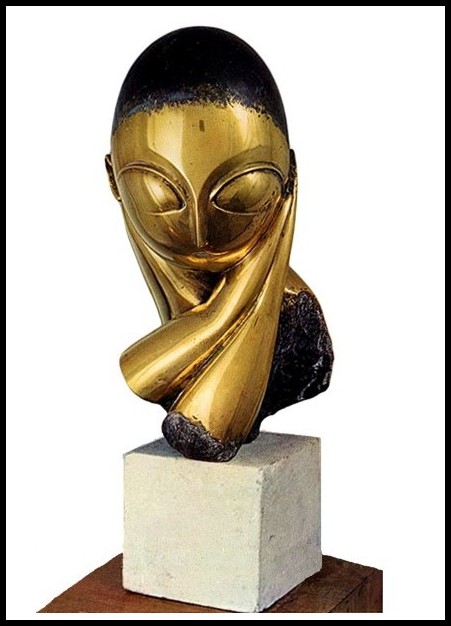

A few months later Brancusi began sculpting the bust for Margit. What he had in mind was a portrait dominated by wide-open eyes and an inward-turned gaze. He carved a bust in white marble that he then went on to refine. The head—where, except for the globular eyes, the facial features are reduced to signs and the hair is drawn back tightly into a bun—leans on the hands in a meditative position. In all likelihood, Brancusi had been preoccupied with the idea for this composition for some time. Had he not used several sittings to study Margit’s hands? Her departure from Paris, probably without any sexual relation having taken place between them, made Brancusi place her in an inaccessible realm, unattainable like a Madonna. The interior force this unidentifiable portrait radiates has elevated it to the status of symbol and earned it an eminent place in modern art.

Brancusi, Mademoiselle Pogany I (marble), 1912

At some point in 1912 Brancusi let Margit know that he had finished the bust. In early 1913 he made a version in plaster and prepared it for the Armory Show in New York. He then had it cast in bronze for Margit. Their correspondence during this period reveals an almost familiar friendship between them. It is an open question whether or not intimacy evolved out of that friendship (Margit wanted to present him to her family in Budapest; she also wanted to have him treated by her doctor friends). At any rate, it was more than just a transactional relation between sculptor and commissioner. On 6 January 1914, Margit announced to Brancusi that the bust had finally arrived. She praised it: ‘I am glad you sent me the bronze; I like it more than the marble.1 The effect of the color you put on it greatly increases its savage, archaic aspect, even while it makes it more natural.’

1 – She had not in fact seen the marble.

Brancusi, Mademoiselle Pogany I, 1912

One day in May 1914 Margit, having remained in Budapest, was surprised to find a note from Brancusi at her studio. She could not have imagined that he would visit Budapest. In fact, he was on his way to Romania. Margit greatly regretted this missed opportunity, as she explained in a letter: ‘It’s really a shame we couldn’t meet. I only saw your note at six in the evening, when I went to the studio’. Brancusi himself always remained secretive about this stopover in Budapest. A number of art historians have speculated that this missed ‘rendezvous’ suggests the commission of the bust hid a love relationship. But if that is in fact true, how can one explain Brancusi’s silence? And the fact that he continued to work on the bust for another twenty years, transforming it and photographing it dozens of times? Could that be a sign of an undeclared love? A love that drove him to ‘abstract’ the bust into the sublime?

Drawing, 1912 | Brancusi, Mademoiselle Pogany | Photograph, 1931

Seven years after the first Mademoiselle Pogany (1912), the globular eyes disappeared, absorbed by the oval of the face, leaving space for pronounced ridges. The joined hands on which the head had rested are now compressed into one, while the bun of coiled hair is now undone, enabling a fall of curls to give a rhythmic elegance to the stooped bust. Brancusi made barely noticeable modifications for the third and final Mademoiselle Pogany (1931), softening the lines of the head in its position of meditation and modesty. The sculpture is no longer the image of Margit Pogany—if it ever was—but the idealized portrait of the woman the artist loved in the intimacy of his studio. If, as legend has it, Pygmalion appealed to Aphrodite to breathe life into Galatea, Brancusi used his camera to caress Mademoiselle Pogany, photographing her under various lighting set-ups, day and night, as if he were bringing her to life. Under the luminous flow, from various angles, the bronze seems to liquify. It became an abiding vision of the artist.

Brancusi, Mademoiselle Pogany, 1931-1933

A few years later Brancusi’s standing in the American art world had increased significantly. Margit then realized the stature of the artist who, thanks to the title of a bust, had made her famous. On a visit to Paris in May 1923 she contacted him. It is uncertain whether they saw each other, either on this occasion or during Margit’s other stays in Paris. It was perhaps inevitable that distance would weaken their ties. All the more so as Brancusi had no lack of female friends. Most were young and pretty artists with whom he would fall in love—to their great pleasure. In 1931 he was working on the third phase of his transformation of Mademoiselle Pogany when, in July, he received a postcard from Margit that depicted the self-portrait she had painted in 1913. Head tilted, leaning on a hand, the portrait showed her in the same position as that of the bust. Had she painted her self-portrait using the bust as a model? At any rate, the coincidence showed she recognized herself in the work that had caused such a stir, a stir which, in turn, confirmed her belief that her meeting with Brancusi had given birth to a masterpiece of modern art. During her last trip to Paris, in 1937, Brancusi was in Romania. We see, then, that if Margit Pogany left a major mark in Brancusi’s work, she left barely a trace in his love life.

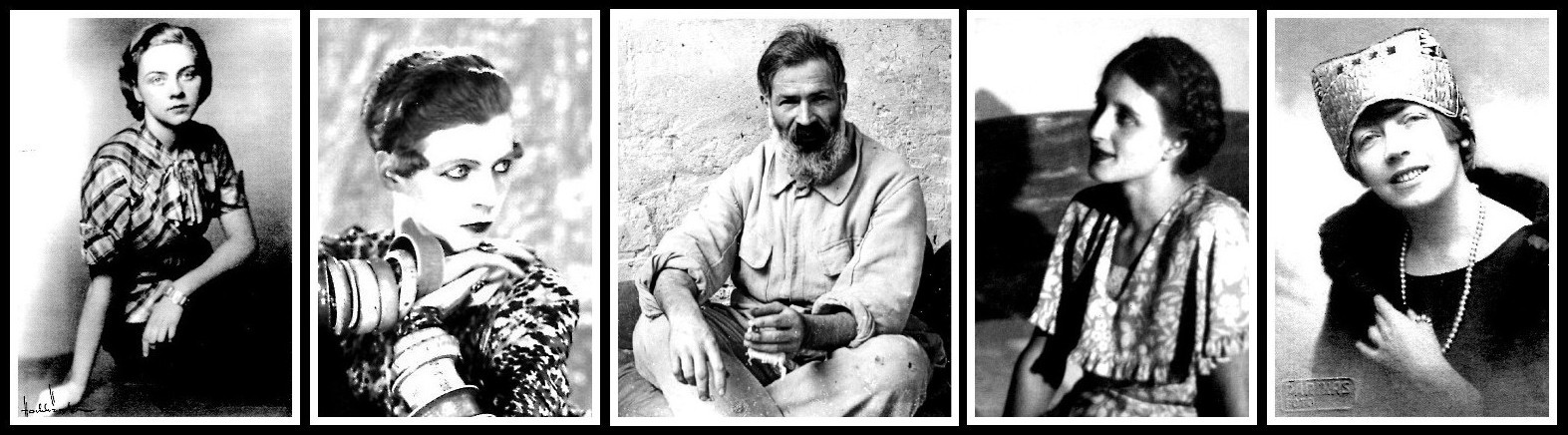

BRANCUSI WITH FOUR OF HIS MUSES

Juana Muller, 1936 | Nancy Cunard, 1925 | Brancusi, 1925 | Marthe Lebherz, 1930 | Renée Irana Frachon, 1922

After the war Margit settled in Australia. On 14 September 1949 she wrote a long letter to Brancusi in which she spoke of how happy she was in Melbourne. She also asked him how much the two bronze sculptures she had bought from him—Bust of a Child (1906) and Mademoiselle Pogany (1912)—were worth on the market. Indeed, she wanted to sell them to a museum since, having lost her fortune in the war, she needed the funds. Brancusi was in no hurry to answer her. A second letter from Margit arrived, sent on 25 November 1949, asking again for an estimate of the price the sculptures could fetch. She explained that it was very difficult for her to accept that she had to sell Mademoiselle Pogany, but her circumstances left her no choice. However, she wrote, she would like a deal with a museum whereby she could keep the sculpture until her death. In 1952, responding to MOMA’s expression of interest in buying Mademoiselle Pogany, she sent them information about the bust and its making. Shortly before her death she sold it to MOMA. It seems clear that Brancusi and the making of Mademoiselle Pogany had marked her for life. The tenderness with which he had approached her enabled him to capture the essence of the feminine in her, while the radicality of the sculpture assured her a place in the history of art.

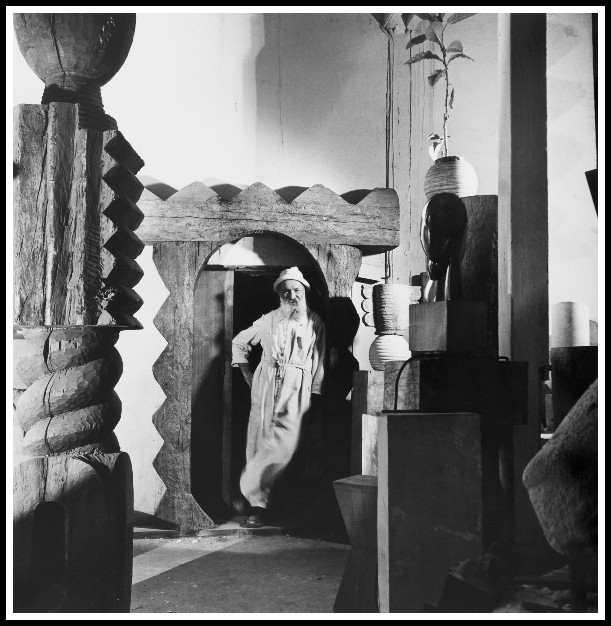

Wayne F. Miller, Constantin Brancusi, 1955

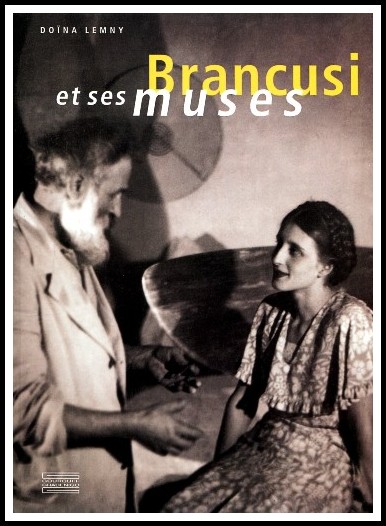

DOÏNA LEMNY: THREE BOOKS (IN FRENCH)

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

II. BRANCUSI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’: MADEMOISELLE POGANY

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel, ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 3

Warming to the art of sculptural observation, you found the different versions of Mademoiselle Pogany even more impressive than the Bird in Space group. ‘When his mistress left Paris for Lausanne, Brancusi carved her likeness from memory’: Does my mother want to make a sculpture of me because I’m not living with her anymore? But it is she who doesn’t want to live with me: Despite what she says, I can feel it. Circling the figures, Catherine pointed out how each version is more abstract than the previous one. Nika preferred the white marble rendering; you the bronze with the black patina: It was more wild and mysterious. When Nika rested a cheek on the back of her hand and struck a pose like that of Mademoiselle Pogany, you thought, ‘I’d rather be an artist than a model’, and made with graceful hand an undulation in the air.

Brancusi, Mademoiselle Pogany: I, 1912 | I, 1913 | II, 1919 | III, 1933

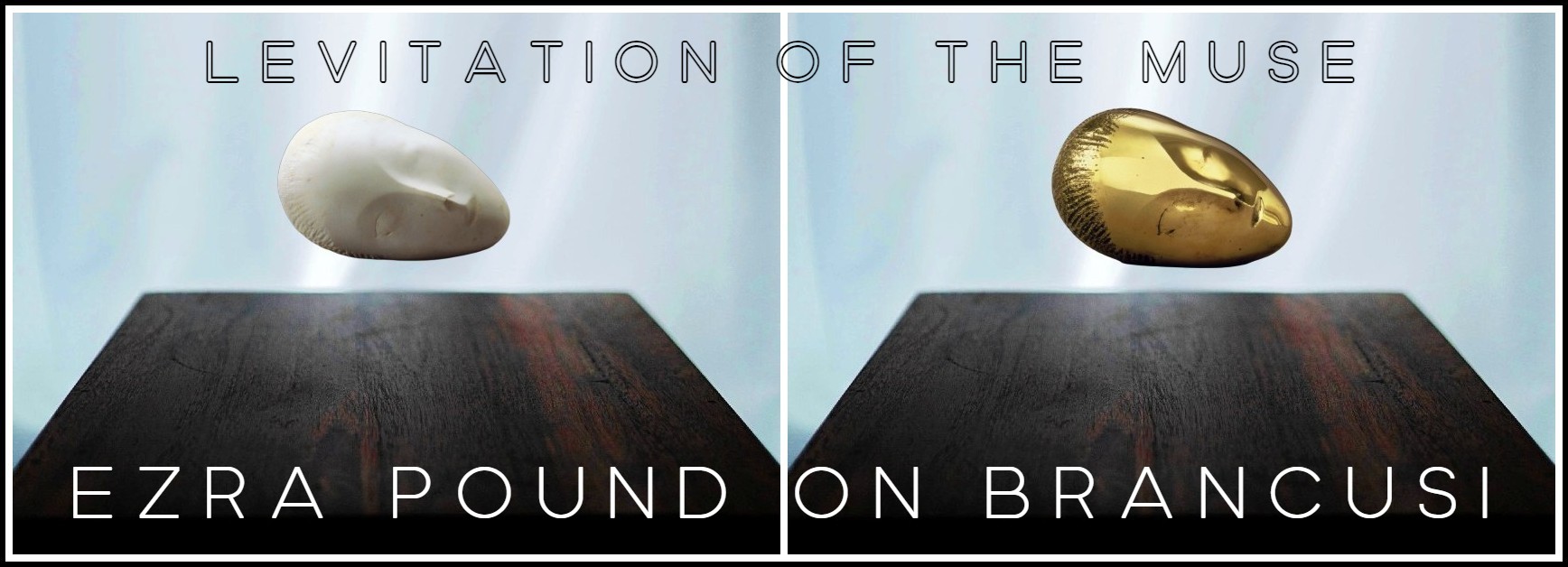

III. EZRA POUND ON BRANCUSI: LEVITATION OF THE MUSE

From Jon Wood, David Hulks & Alex Potts, eds., Modern Sculpture Reader (Leeds & Los Angeles, Henry Moore Institute & J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012) pp. 80-84.

Original Publication: Ezra Pound, ‘Brancusi’ (Paris: The Little Review, Autumn 1921) pp. 3-7.

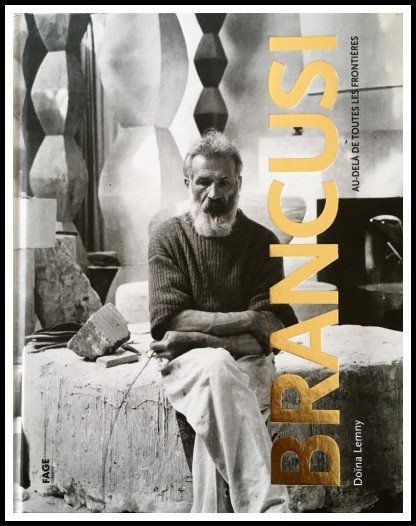

PRELIMINARY REMARK BY RICHARD JONATHAN

Artists often make excellent critics—Beckett on Proust, Nabokov on Tolstoy, Joyce on Ibsen—and this text by Pound is in that tradition. Henry Moore: There is a difference between literary criticism and art criticism in the sense that literary critics are working in their own medium. In their literary criticism, Baudelaire, Coleridge and Eliot really knew what they were talking about because they were poets, whereas very few art critics are practicing artists. Therefore they are more inclined to make stupid errors.1 From Moore’s perspective, Ezra Pound is an exception: A poet writing on a sculptor, he knew what he was talking about. I have, however, made considerable cuts in Pound’s 1921 text for the sake of gaining a clearer focus on Brancusi in our contemporary context.

1 – Henry Moore & John Hedgecoe, Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist (London: Ebury Press, 1986) p. 164

Brancusi, The Sleeping Muse, 1910

INTRODUCTION BY JON WOOD TO POUND ON BRANCUSI

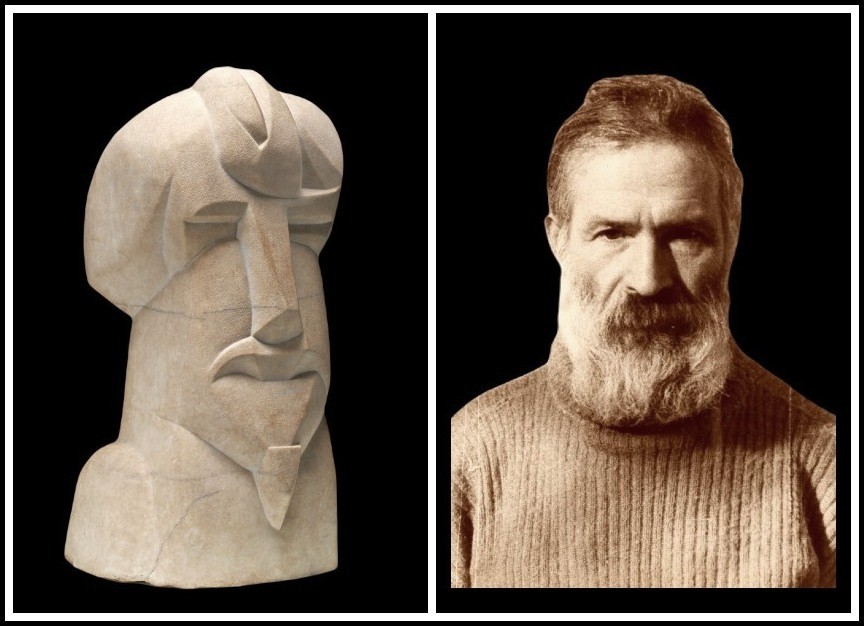

Ezra Pound (1885-1972) was an American poet and essayist whose active involvement with T.E. Hulme, Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticist movement in London before and during the First World War brought him into contact with modern sculpture, as represented by the direct carving of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Jacob Epstein. After the war, Pound settled in Paris, and the close relationship he had established with Gaudier-Brzeska and his subsequent writing on his work provided an important conduit for Pound’s later appreciation of Brancusi’s sculpture, as the poet acknowledges at the beginning of this 1921 article. Pound’s account of Brancusi’s radically pared-down, abstract stone carvings is conducted through a celebration of the sculpture’s deep sensitivity to its material constitution and through praise for the subtle and complex compression of forms and multiple viewpoints within a single free-standing work. Such is the inner and outer power of Brancusi’s sculptures for Pound that he sees them as ‘master keys to the world of form’, and reads this sculptor as being atavistically in touch with the structural and symbolic language of the ancients. The fact that Brancusi works in series and that changes occurred subtly and slowly over time from piece to piece serves to reinforce such sympathies.

Man Ray, Noire et Blanche, 1926 | A ‘homage’ to Brancusi*

* Marielle Tabart, Brancusi: L’inventeur de la sculpture moderne (Paris: Gallimard / Centre Pompidou, 1995) p. 33

For Pound, Brancusi’s work is not easy, ‘off- the-peg’ modern sculpture. Pound raises the question of how we look at the sculpture and introduces the idea of ‘levitation’ as a crucial part of the encounter and sculptural situation at stake for the viewer. Such an appreciation, he admits, might run the risk of being seen as a form of ‘crystal-gazing’ and ‘self-hypnosis’—mystifying self-projection and solipsism that overloads the seductive surfaces of these simplified sculptures with imagined and ‘divine’ meaning. What, however, prevents this from being the case, he concludes, is the fact that these sculptures materially demonstrate such associations, rather than refer to or illustrate them, since with Brancusi ‘the ideal form in marble is an approach to the infinite by form’. This was one of the first extensive articles written on Brancusi’s sculpture, and though highly influential, was not greeted with much enthusiasm by the sculptor himself. It was published in the Paris-based but American-owned magazine The Little Review. As well as providing an important early reading of the Romanian sculptor’s work, introducing it to a wider audience, The Little Review also printed a number of Brancusi’s own photographs of his sculpture to accompany the article.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound, 1914 | Brancusi, Self-Portrait of the Artist in his Studio, 1933-34

POUND ON BRANCUSI: LEVITATION OF THE MUSE

It is perhaps no more impossible to give a vague idea of Brancusi’s sculpture in words than to give it in photographs, but it is equally impossible to give an exact sculptural idea in either words or photography. T. J. Everets has made the best summary of our contemporary aesthetics that I know, in his sentence ‘A work of art has in it no idea which is separable from the form.’ I believe this conviction can be found in either vorticist explanations, and in a world where so few people have yet dissociated form from representation, I may as well approach Brancusi via the formulations by Gaudier-Brzeska:

– Sculptural feeling is the appreciation of masses in relation.

– Sculptural ability is the defining of these masses by planes.

– Every concept, every emotion presents itself to the vivid consciousness in some primary form. It belongs to the art of that form.

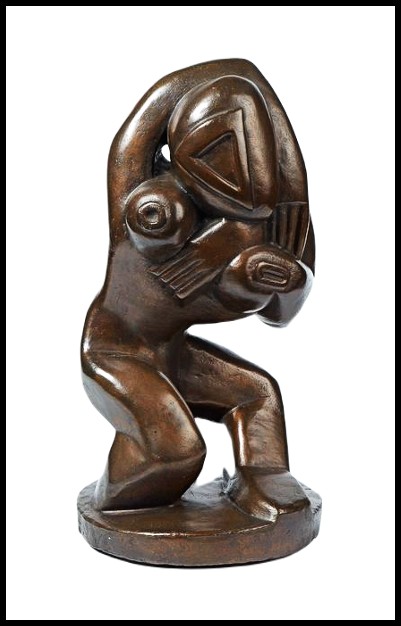

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Birds Erect, 1914

I have found nothing in vorticist formulae which contradicts the work of Brancusi, the formulae left every man fairly free. Gaudier had long since revolted from the Rodin-Maillol mixture; no one who understood Gaudier was fooled by the cheap Viennese Michaelangelism and rhetoric of Ivan Meštrović. One understood that ‘Works of art attract by a resembling unlikeness’; that ‘The beauty of form in the still stone cannot be the same beauty of form as that in the living animal.’ One even understood that, as in Gaudier’s brown [red] stone dancer, the pure or unadulterated motifs of the circle and triangle have a right to build up their own fugue or sonata in form; as a theme in music has its right to express itself.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Red Stone Dancer, 1913-14

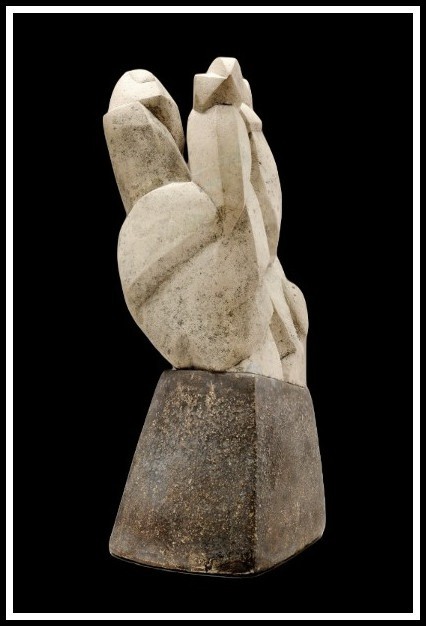

Gaudier had discriminated against beefy statues, he had given us a very definite appreciation of stone as stone; he had taught us to feel that the beauty of sculpture is inseparable from its material and that it inheres in the material. Brancusi was giving up the facile success of representative sculpture about the time Gaudier was giving up his baby-bottle; in many ways his difference from Gaudier is a difference merely of degree, he has had time to make statues where Gaudier had time only to make sketches; Gaudier had purged himself of every kind of rhetoric he had noticed; Brancusi has detected more kinds of rhetoric and continued the process of purgation. When verbally intelligible he is quite definite in the statement that whatever else art is, it is not a ‘crise des nerfs’; that beauty is not grimaces and fortuitous gestures; that starting with an ideal of form one arrives at a mathematical exactitude of proportion, but not by mathematics.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Duck | Dog, 1914

Where Gaudier had developed a sort of form-fugue or form-sonata by a combination of forms, Brancusi has set out on the maddeningly more difficult exploration toward getting all the forms into one form; this is as long as any Buddhist’s contemplation of the universe or as any medieval saint’s contemplation of the divine love. It is a search easily begun, and wholly unending, and the vestiges are let us say Brancusi’s Bird, and there is perhaps six months’ work and twenty years’ knowledge between one model of the erect bird and another. [Look at the Sleeping Muse.] I don’t know by what metaphorical periphrase I am to convey the relation of these ovoids to Brancusi’s other sculpture. As an interim label, one might consider them as master-keys to the world of form—not ‘his’ world of form, but as much as he has found of ‘the’ world of form. They contain or imply, or should, the triangle and the circle.

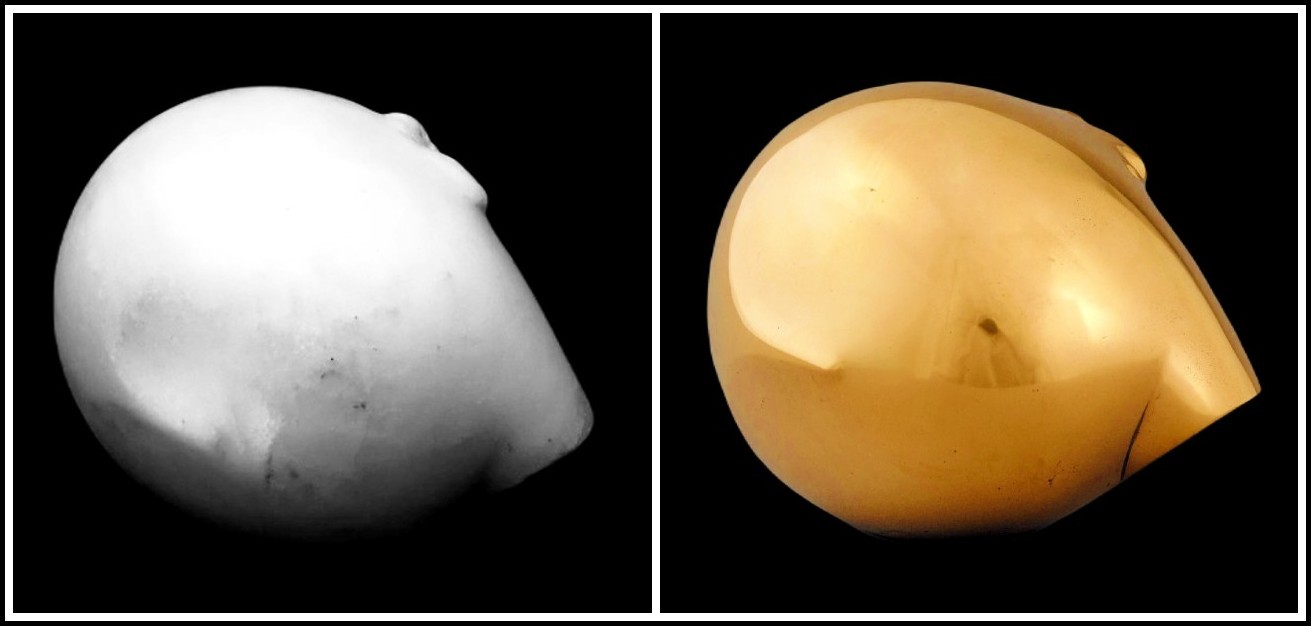

Brancusi, The Sleeping Muse, 1910

Or putting it another way, every one of the thousand angles of approach to a statue ought to be interesting, it ought to have a life (Brancusi might perhaps permit me to say a ‘divine’ life) of its own. It is also conceivably more difficult to give this formal-satisfaction by a single mass, or let us say to sustain the formal-interest by a single mass, than to excite transient visual interests by more monumental and melodramatic combinations. Brancusi’s revolt against the rhetorical and the colossal has carried him into revolt against the monumental, or at least what appears to be, for the instant, a revolt against one sort of solidity. Here I think the concept differs from Gaudier’s, as indubitably the metaphysic of Brancusi is outside and unrelated to vorticist manners of thinking.

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Bird Swallowing a Fish, 1914

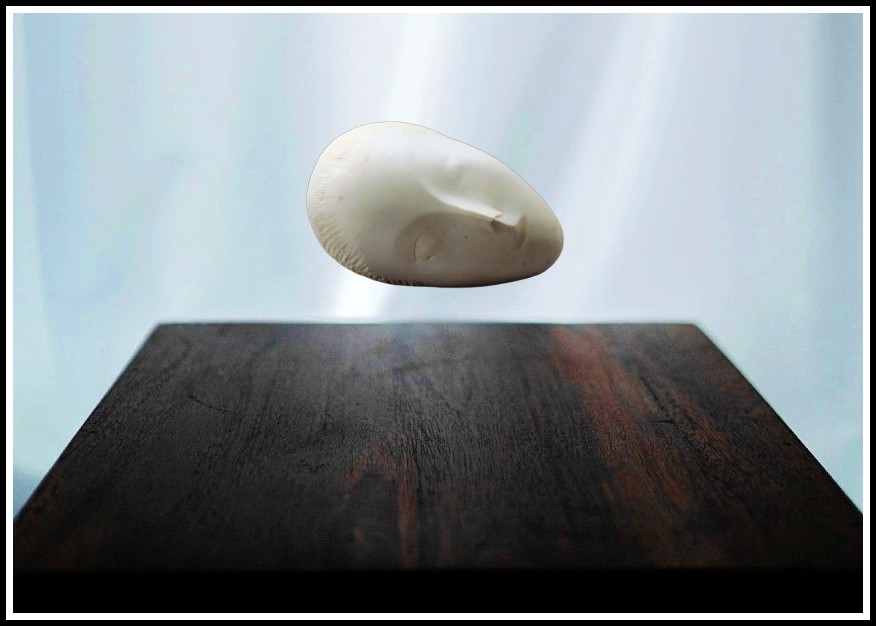

In the case of the ovoid, I take it Brancusi is meditating upon pure form free from all terrestrial gravitation; form as free in its own life as the form of the analytic geometers; and the measure of his success in this experiment is that from some angles at least the ovoid does come to life and appear ready to levitate. Crystal-gazing? No. Admitting the possibility of self-hypnosis by means of highly polished brass surfaces, the polish, from the sculptural point of view, results merely from a desire for greater precision of the form, it is also a transient glory. But the contemplation of form or of formal-beauty leading into the infinite must be dissociated from the dazzle of crystal; there is a sort of relation, but there is the more important divergence; with the crystal it is a hypnosis, or a contemplative fixation of thought, or an excitement of the subconscious or unconscious, and with the ideal form in marble it is an approach to the infinite by form, by precisely the highest possible degree of consciousness of formal perfection; free of accident.

Brancusi, The Sleeping Muse, 1910

IV. BRANCUSI’S BIRDS: MATERIAL & TECHNIQUE

Athena Spear

From Athena Spear, Brancusi’s Birds (New York University Press / College Art Association of America, 1969) pp. 22-27

1. ON ‘TRUTH TO THE MATERIAL’

Most of Brancusi’s friends and critics writing about his work emphasize that ‘truth to the material’ was one of his main preoccupations. However, as both critics and later artists who followed this principle often misunderstood Brancusi’s intention, I shall quote the clearest and most revealing statement of the sculptor’s ideas on this subject, presented in a little-known early article:

If art must enter into communion with nature to express its principles it must also follow the example of its action. Matter must continue its natural life when modified by the hand of the sculptor. The plastic role that it naturally fulfills must be discovered and preserved. To give matter another role than the one that nature intended it to have, is to kill it. Wood, for example, is already and under all circumstances inherently sculptural. One must not destroy it, one must not give it an objective resemblance to something that nature has made in another material. Wood has its own forms, its individual character, its natural expression: to want to transform its qualities is to nullify it and to render it sterile. And the same thing happens with other materials such as stone, marble, and metals; they must all continue their own lives, when, from natural sculptures they are developed into artificial sculptures under the thought and labor of man.

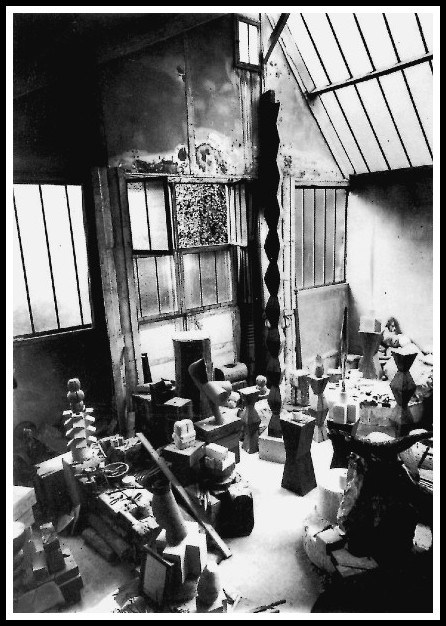

Brancusi, Studio impasse Ronsin, Paris 15e

Matter should not be used merely to suit the purpose of the artist, it must not be subjected to a preconceived idea and to a preconceived form. Matter itself must suggest subject and form; both must come from within matter and not be forced upon it from without. Generally, sculptors proceed with matter by addition when they ought to act upon it by subtraction. To use a soft material and keep on adding to it until the preconceived form is attained and then to inflict it upon a hard and permanent material is a crime of ‘lèse-matter’. All materials have within themselves the sculpture that the man wants; he must labor and get it out, eliminating the superfluous material that covers it. Sculpture is a human expression of nature’s actions. The artist should know how to dig out the being that is within matter and be the tool that brings out its cosmic essence into an actual visible existence.

Brancusi, Fernand Léger in Brancusi’s Studio, 1922 | Brancusi, Studio, 1943-46

And in another early article, by Dorothy Dudley, Brancusi repeats: We must not try to make materials speak our language, we must go with them to a point where others will understand their language. You cannot make what you want to make, but what the material permits you to make. You cannot make out of marble what you would make out of wood, or out of wood what you would make out of stone. Brancusi’s attitude toward the material has its source in his conception of form. The art-object must follow nature’s laws and give by its own organism that which nature gives by its own organization. And, in spite of his insistent and humble obedience to the material, Brancusi sometimes did allow the form to prevail at the expense of the material’s properties.

Brancusi, Carving an ‘Endless Column’ with an Axe, 1925

It is fundamentally true that Brancusi treated the three materials which he most frequently used—wood, marble and bronze—in very different ways. He limited jagged surfaces, complex or perforated forms and rough finish to wood; few of his pieces in wood are polished, and those are usually the ones that he transferred into bronze. Out of over twenty works made in different materials and versions, only four were transferred from wood into bronze, whereas thirteen were transferred from marble to bronze (and a single one, the Portrait of Mrs. Meyer of 1930, was made in both marble and wood).

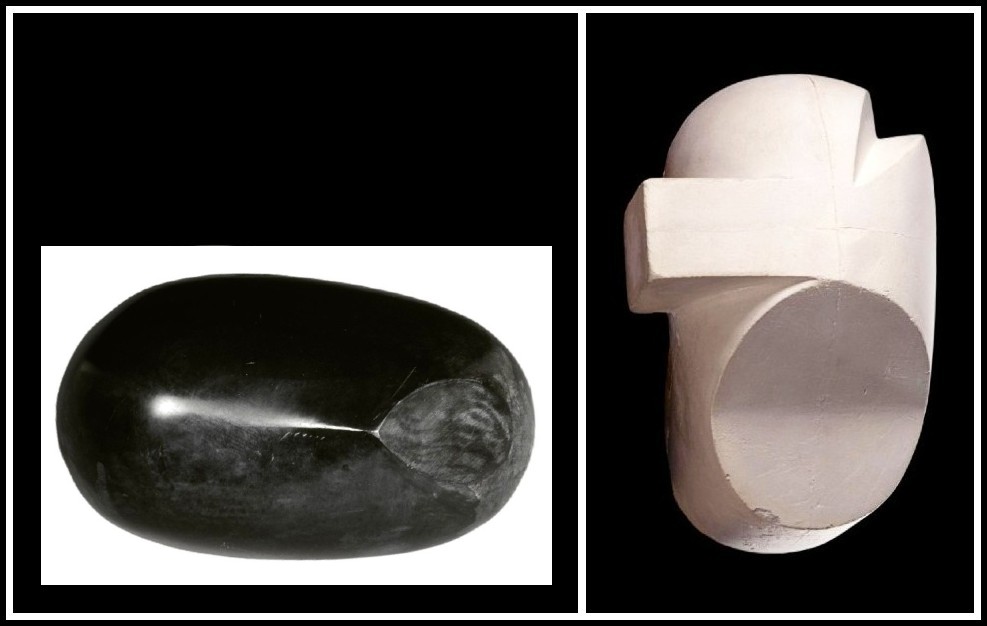

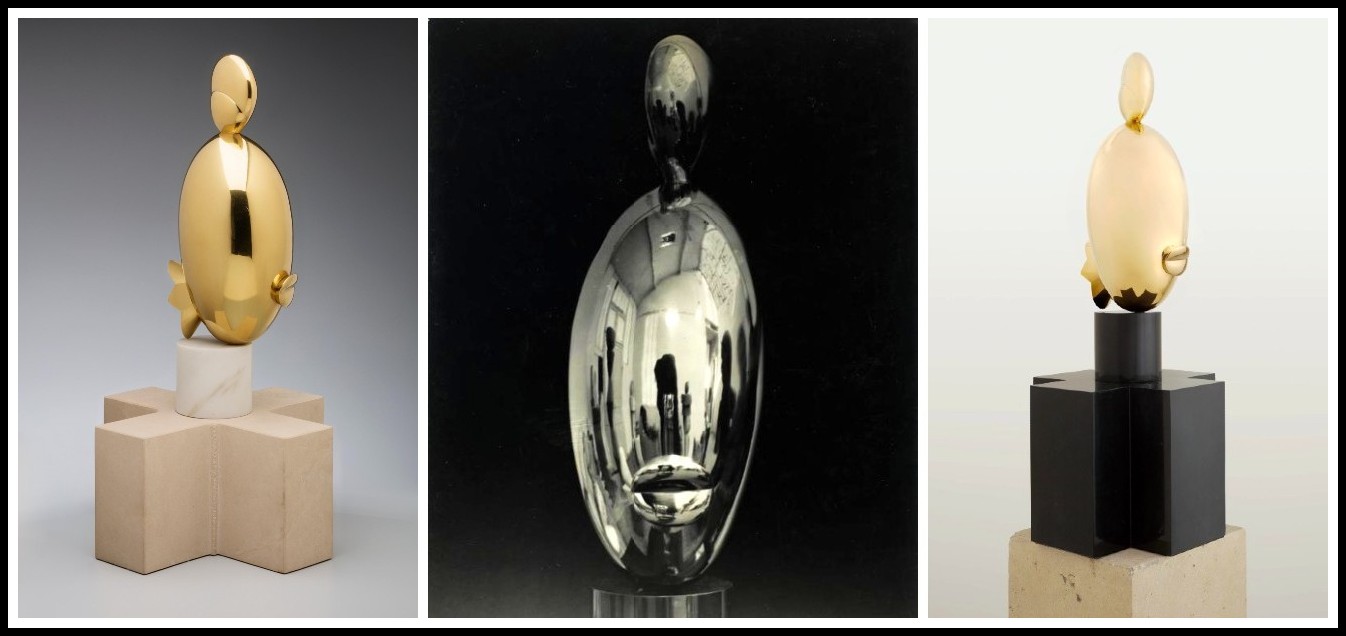

BRANCUSI: Newborn II, 1923 | White Negress II, 1928 | The Beginning of the World, 1924

Most of Brancusi’s works in marble are simplified, convex, self-contained volumes with no holes or projections; and both the precision of his forms and the fine grain of marble led to a polished surface. The even finer grain of bronze allowed an easy transfer from marble to bronze and an even greater precision through a higher polish. The bronze versions were, therefore, the advanced stages of the marbles. After 1908, when he abandoned the technique of modeling and through a two-year period of extensive stone carving reached his mature style, Brancusi almost never made a work first in bronze. With few exceptions, all his bronzes after 1910 were cast from pieces originally conceived and carved in marble (or sometimes wood), Consequently, Brancusi never exploited the elasticity and structural strength of bronze.

Brancusi, Leda, 1926

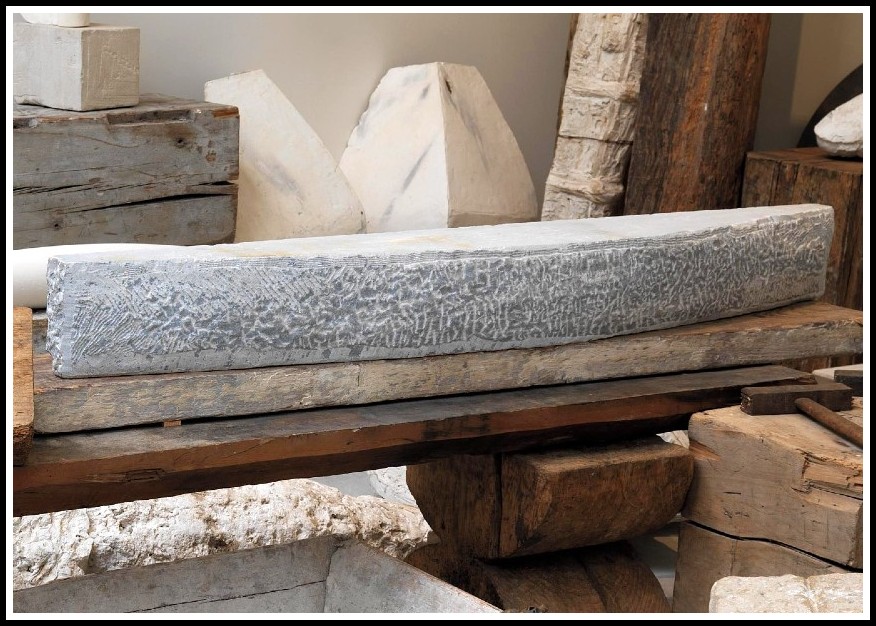

Another example of his untruthfulness to the nature of the material is his disregard for the very limited elasticity of marble in the case of the Bird in Space; as a result, half of his marble birds are broken at the waist in spite of the metal rod inserted in them. It is amazing, in fact, that Brancusi used marble for a form like the Bird in Space. The very challenge of achieving such a technical feat may be the explanation for his doing so. However, his consistent use of marble and the fact that there is not a single bird in wood point to a more serious reason. Wood is too thick-grained and too unreliable to allow for a form as subtle and as precise as the Bird. Moreover, it does not have the nobility and translucency of marble; its complete opacity and its concreteness do not lend themselves to an expression of immateriality or preciousness, which were among Brancusi’s highest aims. He used wood for fantastic, grotesque or witty forms, for supports (Caryatids), bases or furniture; but for his noblest pieces he used marble and bronze. And if he was not true to the structural resistance of bronze, he certainly exploited to the utmost extent the fineness of its grain. He not only achieved through extreme polish the highest perfection of form and surface, but he also revealed the homogeneity and internal purity of bronze in its most glorious aspect.

Brancusi, Blue Turquin marble for Bird in Space, 1950

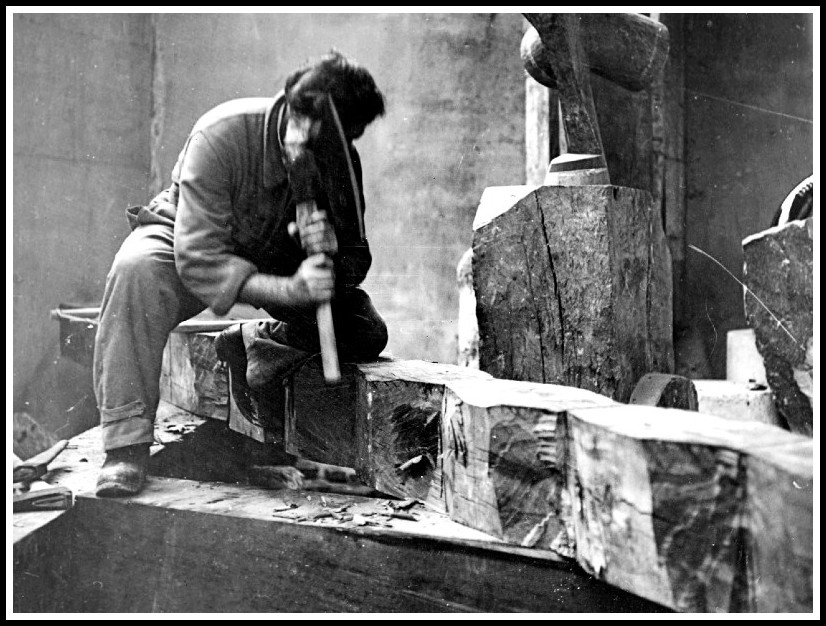

2. THE REASONS FOR AND THE EFFECTS OF BRANCUSI’S HIGH POLISH

Before we examine the reasons and the effects of Brancusi’s high polish we should briefly look into his technique. Reacting against Rodin’s modeling, Brancusi stressed the importance of direct carving in sculpture, especially early in his career: The work of art demands great patience and, above all, a determined struggle against the medium. This struggle can be fully maintained only in the carving process. Modeling is easier; you can revise, correct, add or change, whereas carving means a pitiless confrontation between the artist and the medium to be mastered. This demands craftsmanship. Actually, when you really think about it, sculpture has produced, not great artists but admirable craftsmen. And its decline began with the abandoning of carving, which had enabled the sculptor to win, with each successive work, his own victory over the medium. And in one of his famous aphorisms he said: Direct carving is the true road to sculpture, but it is also the worst for those who have not learned how to walk. And in the end, direct or indirect carving doesn’t mean a thing—it’s the finished work that counts.

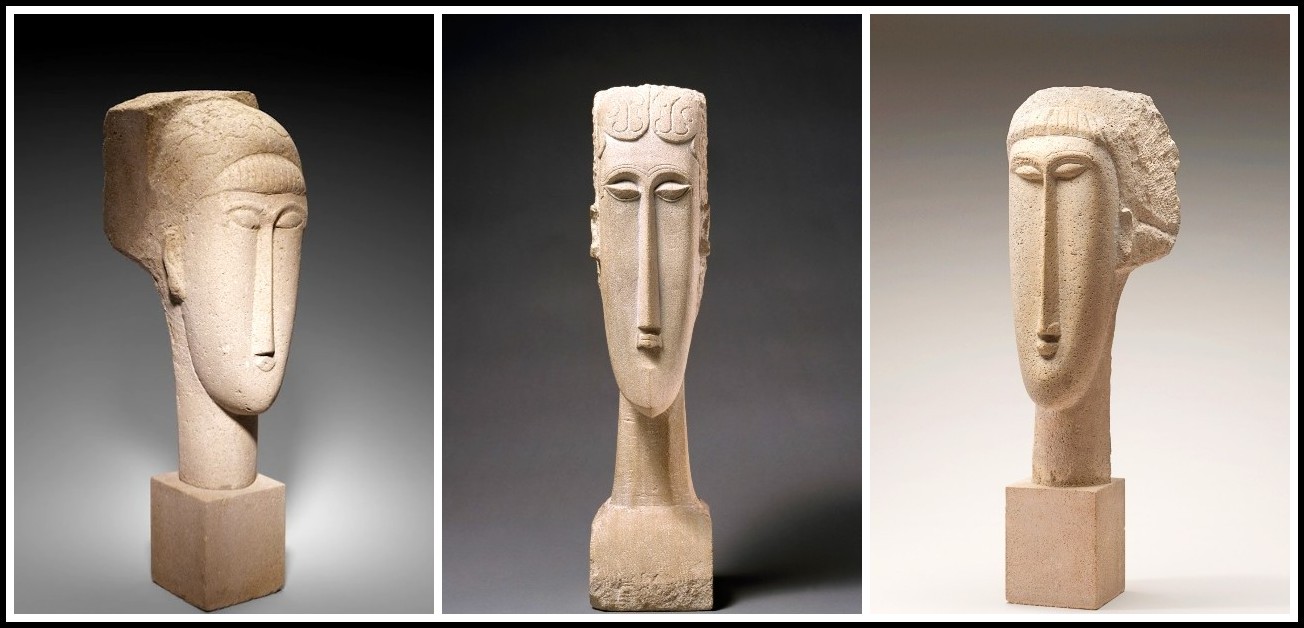

Modigliani, 3 Heads, 1912

Following a stimulating encounter with Brancusi in 1908, for several years Modigliani devoted himself more or less exclusively to sculpture.1

Modigliani: ‘The only way to save sculpture is to start carving again’.2 [Notes by RJ]

1 – Jeanne-Bathilde Lacourt, Amadeo Modigliani: The Inner Eye (Paris: Gallimard – LaM) p. 24

2 – Rudolf Wittkower, Sculpture (London: Peregrine Books, 1979 ) p. 261

In fact, although Brancusi generally cast his bronzes after a marble or a wood prototype, in the case of the Bird in Space there are a number of bronze versions which have no carved equivalents. They must have been made after plaster models, either cast from previous marbles and then modified, or directly built in plaster on a metal axis. Some of these plasters still carry the traces of negative molds which indicate that they were most likely cast after marbles. As far as I could determine when examining them, the rest of the plaster birds are perfectly smooth, which means that the mold marks have been removed or that these plasters were modeled directly. Brancusi’s bronzes. Therefore, from the very beginning had a more or less finished surface which he subsequently polished further, first with thinner and thinner files, then with thinner and thinner emery paper, and finally with a fine buffing powder or jeweler’s rouge, until every trace of his hand disappeared and the metal obtained a glossy sheen.

Brancusi, Bird in Space, 1927

As the sculptor Isamu Noguchi, Brancusi’s assistant in 1927, testifies, Brancusi did not believe in any kind of permanent preservation of the polish (lacquer or wax, and so on). He used ordinary brass polish to clean the surface every few weeks or months, and that is the treatment he recommended to both Quinn and Steichen. As he wanted his bronzes to be absolutely sparkling, he disliked lacquer or any other surface coating which would deaden the work. In this connection Noguchi relates: Brancusi exhibited his Leda at the Salon des Tuileries while I was there and I was sent each week to polish it with ordinary brass polish. The matter of finish was an obsession with him, to capture the pure essence of the material with no accidental blemish. When I saw him after the war, he told me of the difficulty he had in getting a proper mirror surface on the disk under one of his fish. He showed me one he had had made in Germany which he said was of course much better than what could be had in France, but still so far from perfect, as it was done by machine, that he had to redo the whole thing by hand himself.

Brancusi, Fish, 1926

Earlier in his career, on the occasion of the lawsuit about the Steichen Bird, Brancusi also stressed the manual aspect of his work: When the roughcast was delivered to me, I had to polish the bronze with files and very fine emery. All this I did myself, by hand. Indeed, although later in his life Brancusi did use electrically operated tools (buffing wheels, etc.), the ultimate finishing he always did by hand. The subtlety, vitality, and extreme precision of his surface could only be achieved by an artist’s sensitive hand, not by machine. Brancusi wished to achieve as perfect a finish as possible and tried to eliminate faults at the casting stage. He was very particular to secure bronze castings with as few pit holes as possible, continues Isamu Noguchi. For that reason he abandoned his earlier lost-wax founders and, in his mature years, preferred sand casting. As far as I have been able to determine, there are no foundry marks on any of the birds except for the Steichen and Graham Maiastras (nos. 2 and 3), but some of the early versions (e.g., Des Moines Maiastra, no. 5; Chicago Golden Bird, no. 8) have numerous pit holes, which suggests that they were probably cast with the lost-wax process.

Brancusi, Maiastra, 1911 (Graham) & 1912

The color of the bronze also raises some questions. Common bronze, composed of about 86% copper, about 14% tin, and a little zinc, has a pinkish color (see Brancusi’s small New Born in the Museum of Modern Art, New York). But each foundry has its own formula for the alloy, and apparently a considerable number of foundries use a greater percentage of zinc or other metal, which lends to their bronze a yellow color similar to that of brass (60 to 85% copper, and the remainder zinc). It is also possible that Brancusi always requested that his own alloy be yellower, as he declared he did for the Steichen Bird. But why did he wish to achieve this impression of gold? And how did he first arrive at the idea of high polish instead of using traditional gilding? Before answering these questions, we should determine which was Brancusi’s first polished bronze. We know that there is in the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris one bronze version of the Sleeping Muse, dated 1910, which is completely unpolished. The other bronzes of this work, as well as the first bronzes of the Muse (1912), Danaide (1913) and Mlle Pogany (1912), are polished only on the flesh areas and are rough and darkened on the hair area. Therefore, I believe that Brancusi’s first fully polished bronze is the Steichen Maiastra of 1911.1 What could suddenly have given him the idea of high polish? The difference between Nadelman’s rounded and smoothed forms and Brancusi’s extreme polish is too great to accept a possible influence from Nadelman. I find it more likely that his initial aim was to obtain the brilliance of gold so desirable for his Maiastra bird. We know from Edward Steichen and from Mme Iréne Codréano, who was Brancusi’s assistant in the mid-twenties, that Brancusi did try traditional gilding early in his career. But he soon abandoned it, because surface gilding could never create the inherent and immaculate shine that he wanted.

1 – As, to the best of my knowledge, there is no catalogue raisonné of Brancusi’s complete oeuvres, I am unable to explain the discrepancy between the dates given here for the Steichen Maiastra/Bird (1911 vs. 1926)

BRANCUSI: Newborn I, 1920 | Bird in Space, 1926 (Steichen)

Although Brancusi might originally have aimed only at the glamour and nobility of gold and at the perfection of surface, many other important effects resulted from his use of high polish. First, the broken highlights and shadows produced on a polished sculpture abolish mass. The continuous soft passage from light to shade, which our sense of sight is trained to interpret as volume, does not exist here; the traditional relation between chiaroscuro and surface modulation is definitively lost. Moreover, the polished work, by reflecting the surrounding space on its surface, creates an illusion of depth where convexity is normally expected and a spatial ambiguity is thus produced. At the same time, high polish inevitably relates the work with its environment—and with the spectator as well, because his image, too, is captured by the mirror-like surface which he cannot escape while looking at the sculpture. Both the environment and the spectator, of course, are deformed in reflection, since there is no large flat area in Brancusi’s sculpture. Semispherical or oval convex surfaces bend straight lines, giving to parallelepipedic interiors of buildings a rounded shape. These surfaces, having a considerably wider angle of reflection than flat mirrors, capture in miniature distant space, and disproportionately enlarge nearby objects which appear to be attracted toward the convex mirror as by a magnet. On the other hand, cylindrical convex surfaces lengthen all forms in the direction of their axis. Thus the spectator, captive of the polished sculpture, witnesses the amusing or terrifying deformations that he undergoes and over which he has no control.

Brancusi, Maiastra, 1912-13

Moreover, since these reflected images change continuously as one walks around the work, movement and time are introduced into sculpture. This was one of the effects of polish which Brancusi clearly enjoyed. “I asked him once,” writes James Thrall Soby, “whether the reflections caused by his sculptures’ high polish ever bothered him or altered the meaning he had in mind. ‘I don’t care what they reflect, so long as it’s life itself’ he replied.” He even placed several of his polished works on rotating bases in order to multiply and accelerate the moving reflections, thus heightening the fluidity of the forms through the gliding, fugitive highlights.

Brancusi, La Négresse blonde, 1926

However, the polished sculpture renews itself not only by capturing the surrounding movement, but also by being placed in different environments and under different light conditions. We know that Brancusi was especially interested in the lighting of his bronzes. Direct light creates on the crests of convex surfaces dazzling highlights echoing the light source itself. These ‘points generating light,’ as V. G. Paleolog calls the crests, can be controlled by the sculptor to a considerable extent. That Brancusi was aware of the placement of his projections is evident in the fact that only he was able to catch in photographs those flashes of light which make the sculpture burst into fireworks. He usually exploited sunlight to surprise the spectator and to give lo his works a sublime aspect, as the painter Reginald Pollack recounts: In conversation, Brancusi would suddenly whisk off the dust-cover with the aid of a long pole. A square of sunlight would fall miraculously on the brilliantly gleaming sculpture. The bevelled top of Bird in Space caught the full glare of sunlight, throwing it back into the visitor’s eyes, blinding him. The effect was miraculous and awe-inspiring and one had to check an impulse to fall to one’s knees before the sculpture. One can understand how Brancusi’s immaculate bronzes, exempt from material weaknesses and particularities, might become objects of worship. He did indeed plan to use them as such in his projected temple for the Maharajah of Indore. According to Roché’s description, on a sacred day of the year the sun was expected to hit the bronze Bird in Space and cover it with golden splendor. Thus, through high polish, Brancusi’s birds come back to their mythic origin. They respond to the call of the sun. Like the Phoenix, they dissolve their material body and transform themselves into sources of light. And, wearing their sacred aura, they join the solar divinities of all ages.

Brancusi, Bird in Space, 1932 & 1936 (middle photo: composite RJ)

V. BRANCUSI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’: BIRD IN SPACE

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel, ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 3

The next day your mother took you and Nika up the Empire State Building (the rush of exhilaration, the inspiriting power!) and then on to the Museum of Modern Art: She hadn’t giving up trying to persuade you to model for her. You and Nika were full of nervous energy, fooling around (and around) with the revolving doors in the lobby, competing to see who could make the best milk moustache in the cafeteria, trading T-shirts and sneakers in the washroom. And then your mother led you to the Brancusi exhibition. You were intrigued by the various versions of Bird in Space, their sleek form and soaring grace.

̶ He’s not sculpting birds, your mother explained, he’s expressing their essence.

They’re lovely, you thought, contemplating the serene swell of the elongated bodies.

̶ A bird in flight leaves nothing but a memory of movement—Brancusi’s sculptures leave nothing but their luminosity.

̶ Their light?

̶ Yes, that shine that comes from the perfection of the polishing.

Enlivened by a feeling of freedom, you thought: These sculptures would wake up any sleepwalker.

Brancusi, Bird in Space, 1923