Giacometti: Presence & Repetition

I. GIACOMETTI & MERLEAU-PONTY | II. GIACOMETTI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’ | III. GIACOMETTI’S REPETITIOUS ART

I. GIACOMETTI & MERLEAU-PONTY, OR ‘THE PRESENCE AT THE ROOT OF THE PHENOMENON’

Thierry Dufrêne

Posted by kind permission of Thierry Dufrêne, Professor of Art History, Université Paris Nanterre

From Thierry Dufrêne, Giacometti: Les dimensions de la réalité (Geneva: Éditions Skira, 1994) pp. 128-32. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

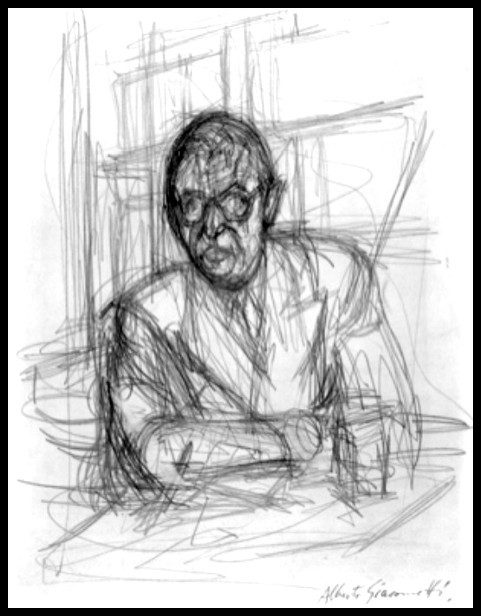

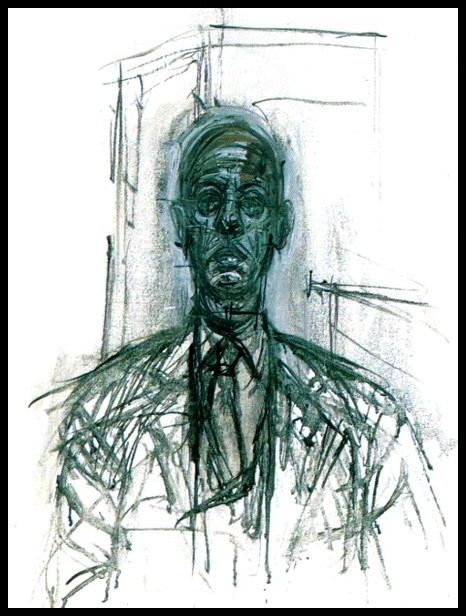

Giacometti, Seated Nude in the Studio, 1953

The conviction that one is bringing into awareness an original sensation akin to ‘being-in-the-world’ is apparent in both Giacometti’s approach to art and Merleau-Ponty’s to philosophy. That presence derives from ‘the root of the phenomenon’, an expression we owe to Jacques Lacan.1 He speaks of ‘the purity of the presence at the root of the phenomenon, in what it can anticipate of its evolution in the world’. Qualifying that statement, however, Lacan asserts that ‘the idea that there is a locus of unity somewhere’ is not one to which he can subscribe. Giacometti’s works of 1947—brutal objectifications of a phantasy, radically excluded from alignment with the world (cf. le Nez or Tête sur tige)—had largely anticipated this objection.

1 – Jacques Lacan, ‘Maurice Merleau-Ponty’ in Les Temps modernes n° 184-185, 1961

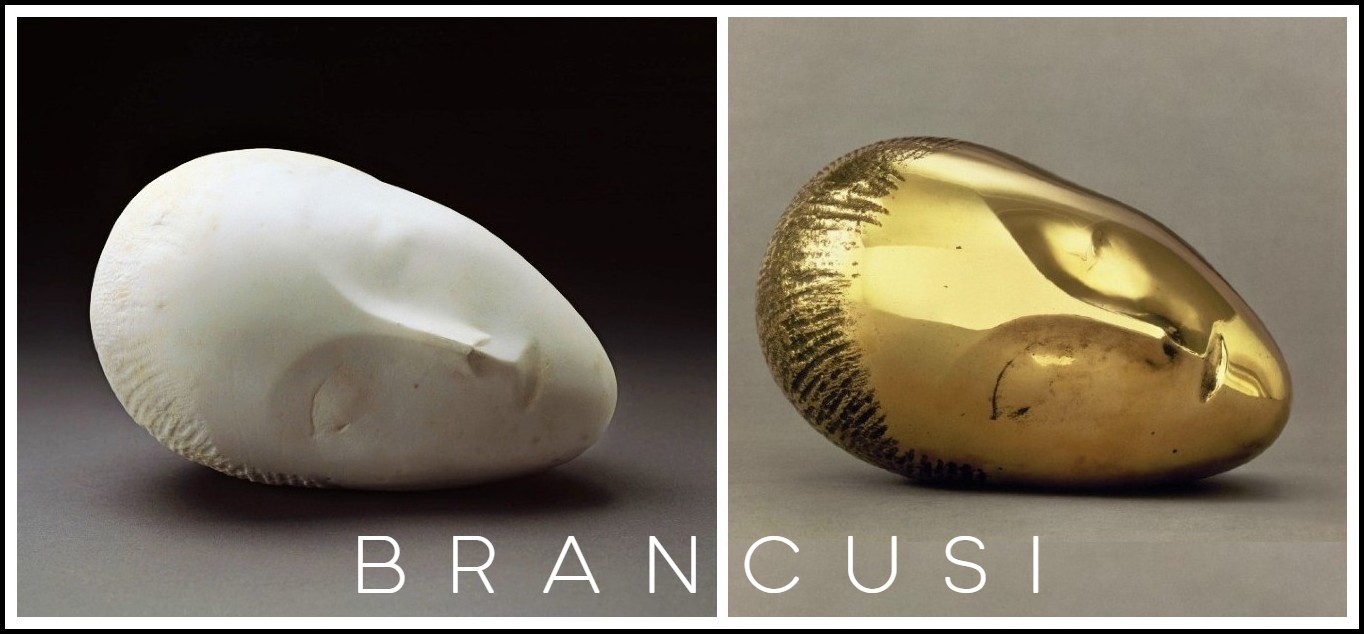

GIACOMETTI: Tête sur tige, 1947 | Le Nez, 1947

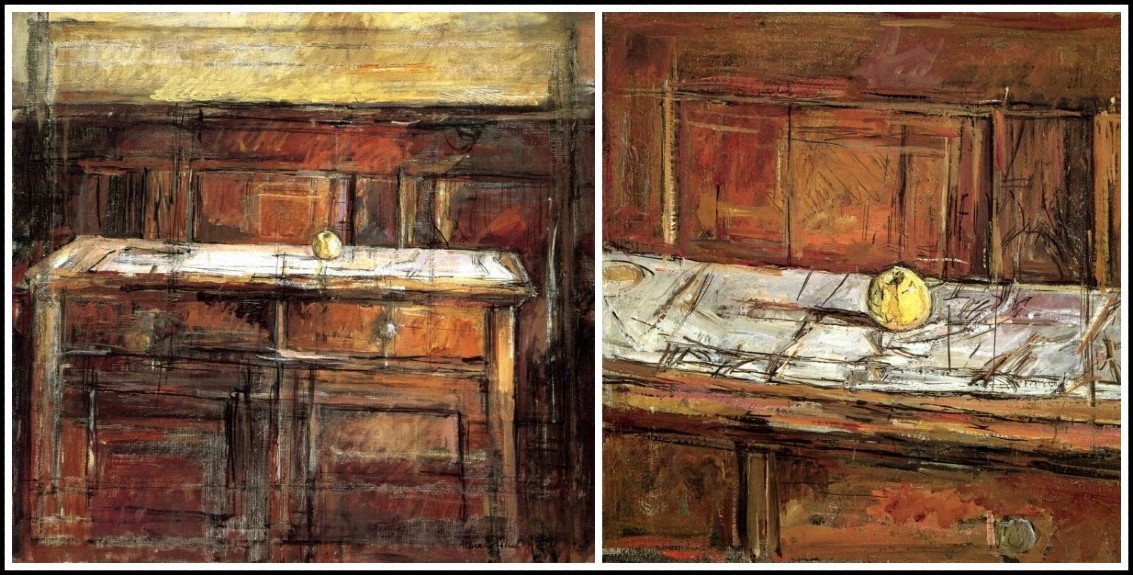

‘The presence at the root of the phenomenon’ is an expression that can characterize the work of both Giacometti and Merleau-Ponty. Independently, each developed, as early as the 1930s, an aesthetic of being-in-the-world. Merleau-Ponty’s analysis of perceptual consciousness follows his model of the creation and analysis of a painting. In many respects, the phenomenology of perception is a phenomenology of creation. The artist undertakes to make of the unfolding and clarification of his gaze the driver of his work. In both art and philosophy there is a ‘return upstream’, to use René Char’s expression, a return to primordial vision, to an experience of reality in one’s ‘full coexistence with the phenomenon’.1 In this experience the world and consciousness are one. The quest for what we can now call ‘nascent vision’ entails a description of reality. ‘The real is to be described’,2 writes Merleau-Ponty, while Giacometti practices a return to ‘appearances’. This attests to a confidence in sensibility, apt to provide guidelines for consciousness. Merleau-Ponty aligns himself here with Husserl, Giacometti with the confidence of Cézanne in his ‘petite sensation’. Description supposes a suspension of judgement or of the imaginary, and it is this suspension that comes across as astonishment in the Phenomenology of Perception3 and as magical reality in Pomme sur le buffet, where what accounts for the reality of the apple is precisely what distances it from us and makes it impossible for us to possess it.

1 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Taylor & Francis, 2013 [1945) p. 332

2 – Ibid. p. LXXIII

3 – Merleau-Ponty speaks of a ‘momentary pause in the perceptual process’ and compares it to how, in a cinema, the ‘interruption of the sound invades the screen with the form of a sort of stupor’ (Ibid. p. 242, 243).

Giacometti, Pomme sur le buffet, 1937

Merleau-Ponty’s description of the world derives from his model of painting. In the era of scientific description, that is highly original. Defining ‘style’ as one’s perception of the world, he writes: ‘Along with existence, I received a way of existing, or a style’.1 Style is not a ‘manner’, a conscious application of a pre-conception; rather, it is perceptual consciousness itself. Perception is individual and engages personality in its entirety. It projects itself into the future in the form of an intentionality that maintains it: ‘… my world is carried forward by lines of intentionality which trace out in advance the style of what is to come’.2 Every man hopes for something different and finds accents of something familiar. Thus Giacometti’s amazement when he ventures into the unknown and is told that in his painting we recognize his brother Diego or his wife Annette. If my perception constitutes a ‘certain accent of the world’s style’,3 it is because ‘my phenomena solidify in a thing and follow a certain constant style in their unfolding’.4 It is this durational dimension that enables one to grasp the reality of a perception that is volatile in its essence, a state of consciousness subject to the unfolding of time.

1 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Taylor & Francis, 2013 [1945) p. 482

2 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, tr. C. Smith (New York: The Humanities Press, 1962), p. 416

3 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Taylor & Francis, 2013 [1945) p. 428

4 – Ibid., p. 429

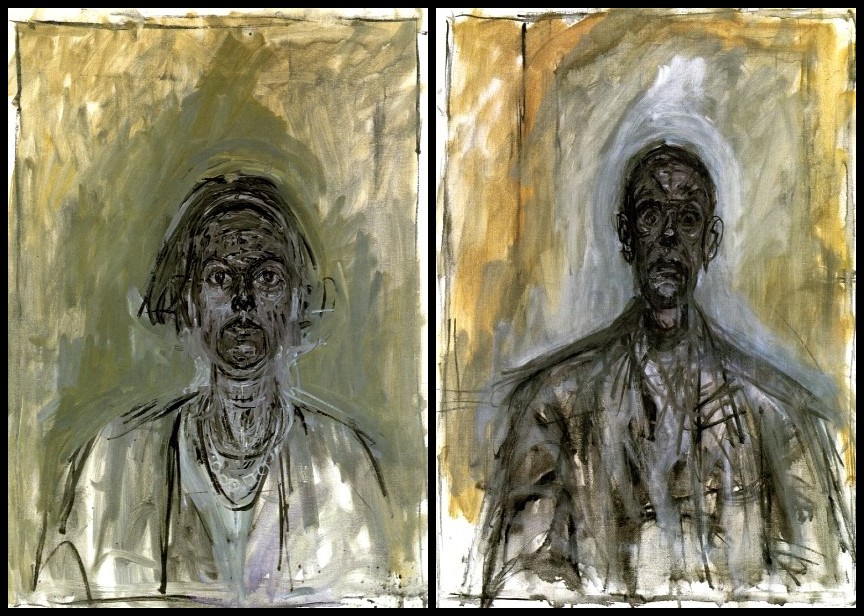

GIACOMETTI: Portrait of Annette, 1964 | Head of a Man III (Diego), 1964

Merleau-Ponty places at the origin of perception ‘an indeterminate vision, a vision of something or other’;1 elsewhere he uses the expression ‘halo of indeterminacy’2. That is what he calls the ground. This ground is already a framework, with perception governed by physiological factors (‘the structure of my retina necessitates my seeing the surroundings as blurred if I wish to see the object in focus’3), by the bodily organization of the perceiving subject (verticality, angle of vision) and by basic factors (light, and above all, depth, ‘the most existential of all dimensions’4). Then comes attention: ‘To pay attention is not merely to further clarify some pre-existing givens; rather, it is to realize in them a new articulation by taking them as figures’.5 This substitution of figure for ground must not obscure the fact that ‘the ground continues beneath the figure’.6 This fact envelops the whole problem of the presence of the object. This is a key point, for it explains what Giacometti found lacking in both the film and photographic image: what is missing is the background, the underlying framework, which is much more than the image. It is the possibility of the figure to dissolve into the ground, and in that case, it is depth that becomes sensible, almost in a pure state, as a latency, a permanent reserve of ‘stupor’. This faculty of dissolution no longer exists in cinema, which is a positive, linear art in which the dissolve (fade-in/fade-out) can only be a narrative procedure. Painting is never a ‘freeze frame’, since it enables hallucinatory play to be present as figure and absent as ground in a to-and-fro movement, similar to the ‘fort/da’ game described by Freud. This accords consciousness the freedom to attend to an object or to ignore it, so that at each instant the object is at once grasped and abandoned to its dependence.

1 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Taylor & Francis, 2013 [1945) p. 6

2 – Ibid., p. 22

3 – Ibid., p. 70

4 – Ibid., p. 267

5 – Ibid., pp. 31-32

6 – Ibid., p. 26

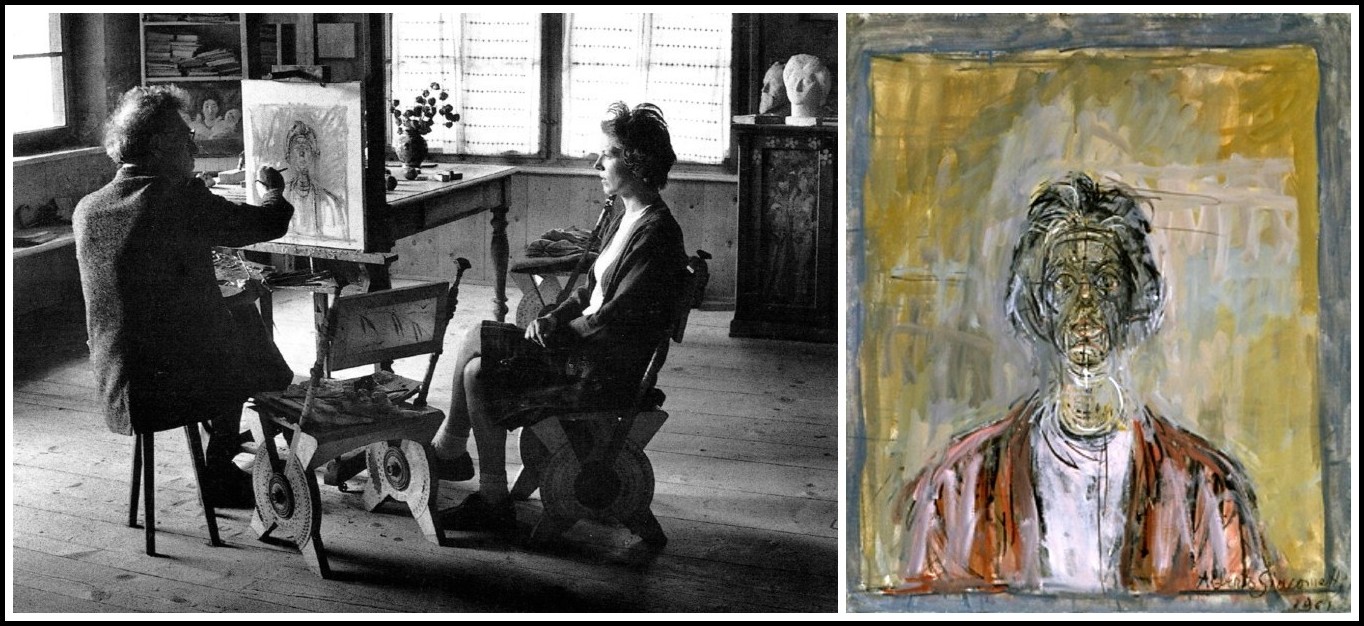

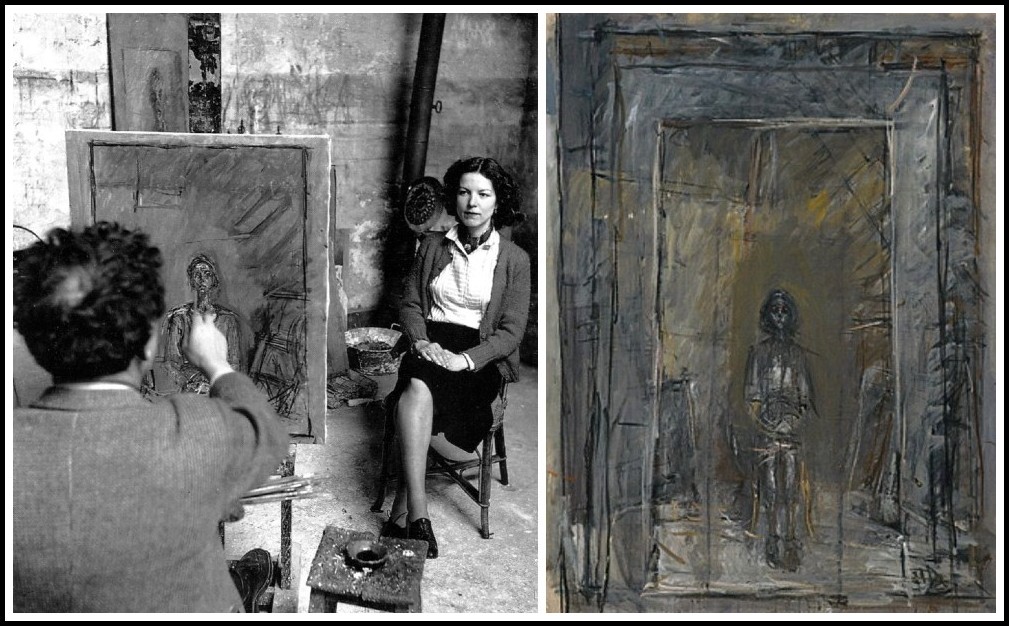

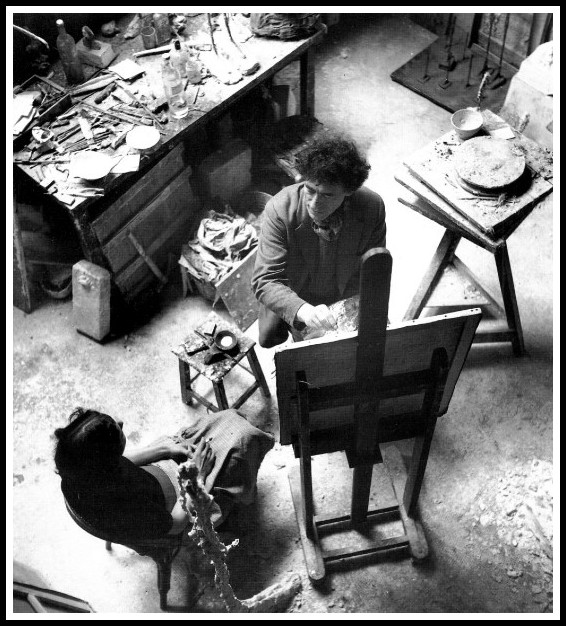

Ernst Scheidegger, Giacometti Painting a Portrait of Annette, 1960 | Giacometti, Annette, 1961

How does Merleau-Ponty conceive of visible phenomena? They are ‘sensible emblems that appear from a certain hold on things.’1 He writes: ‘Our perceptual field is made up of things and the gaps between things’.2 To perceive an object is literally ‘to inhabit it and to thereby grasp all things according to the sides these other things turn toward this object’.3

1 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Taylor & Francis, 2013 [1945) p. 406

2 – Ibid., p. 16

3 – Ibid., p. 71

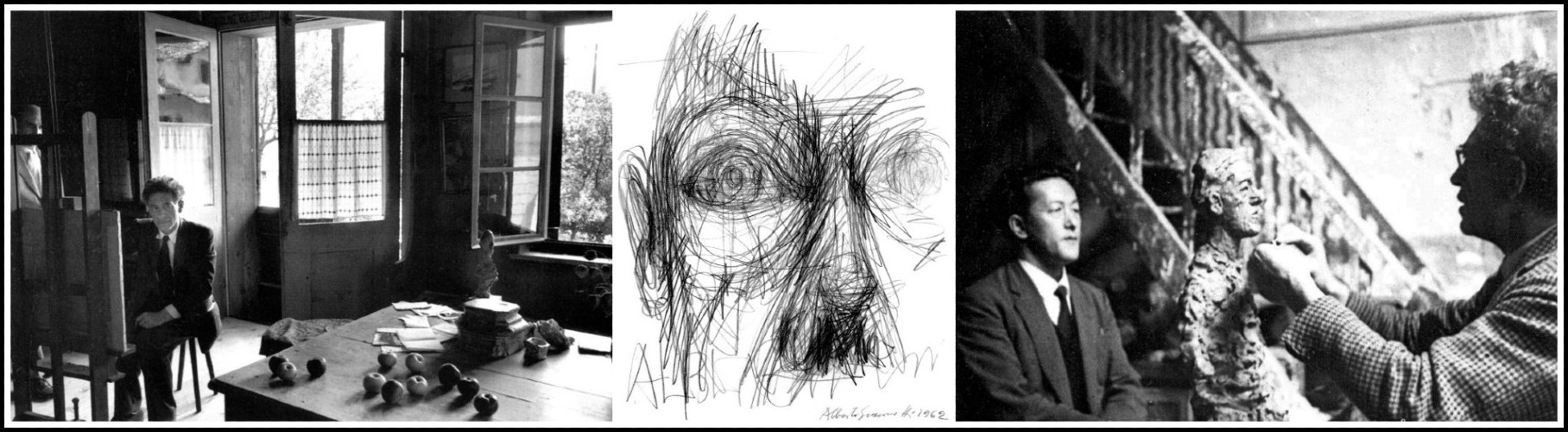

Cartier-Bresson, Giacometti in Stampa, 1960 | Giacometti, Les Yeux, 1962 | James Lord, Giacometti – Isaku Yanaihara, 1960

Giacometti and Merleau-Ponty both emphasize that one sees with one’s body-in-situation, and they point out the limits of human vision. In The Prime of Life, Simone de Beauvoir writes: ‘Giacometti’s point of view is phenomenological, because he sets out to sculpt a face-in-situation, in its existence-for-others, thus overcoming the errors of both subjective idealism and false objectivity’. In my book Giacometti: Portrait de Jean Genet, ou le scribe captif (1991), I showed how Giacometti’s analysis of perception and Merleau-Ponty’s converge. They both take account of the existential dimension of depth, they both distinguish between a central vision in focus and a blurred peripheral one, and they both pay attention to the ‘living gaze’ and the existence of a face situated at a distance in the here and now.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty | Giacometti, Figure grise, 1957 | Kurt Blum, Giacometti in Berne, 1965

In addition, both Giacometti and Merleau-Ponty adopt Cézanne’s dictum that ‘nature is on the inside’. They show that there is an ‘internal equivalence, a carnal formula within us of the presence of things’.1 Reality, then, is ‘soluble’ within us and the eye restitutes to the visible via the traces of the hand the impact the world has made on it. Merleau-Ponty cites Giacometti’s statement to Charbonnier: ‘What interests me in all painting is resemblance, or what for me is resemblance, what enables me to discover more of the world’.

1 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Eye and Mind in The Merleau-Ponty Reader, ed. Leonard Lawlor & Ted Toadvine (Northwestern University Press, 2007) p. 355

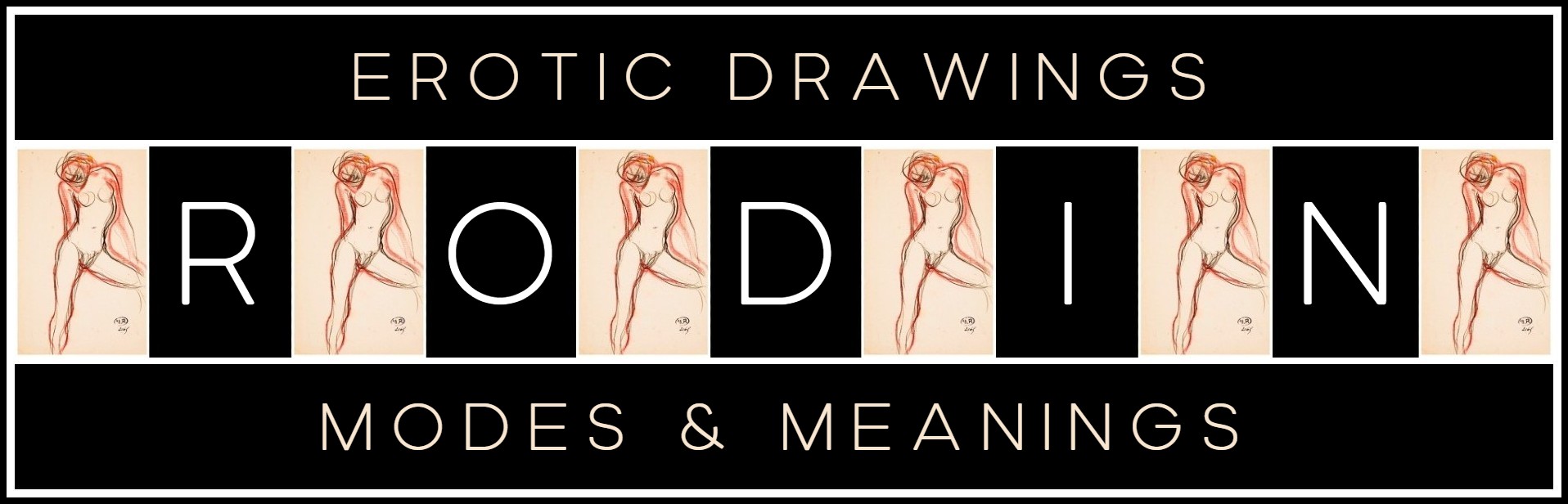

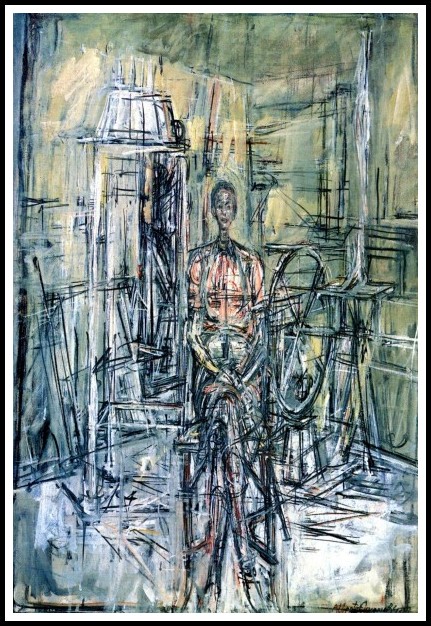

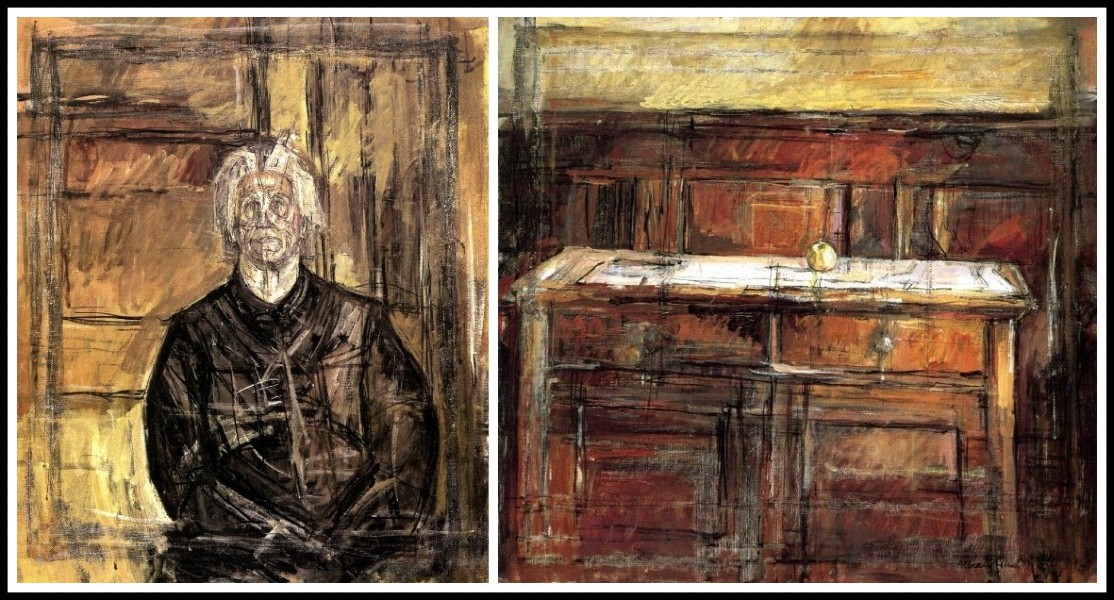

GIACOMETTI: Nature morte aux pommes, 1946 | Le Buffet, 1957

The artist can produce what he feels, and not only create relays via which his thought would be, as in the Cartesian model of vision, ‘stimulated to conceive’; he can trigger a sensation that touches the viewer. The work is vision itself, that combination or mixture of perceiving subject and perceived object, the union of the visible and the invisible. As Giacometti said to Parinaud, ‘Modern artists all endeavour to grasp something that continually escapes capture. They want to possess the sensation they have of reality, more than reality itself’. Note the similarity with Cézanne’s statement: ‘What I am trying to express is more mysterious; it is entangled in the very roots of being, in the shadowy source of emotions’. We can see why Merleau-Ponty is drawn to both Cézanne and Giacometti. Phenomenology since Husserl is indeed the art of making explicit the way beings and things appear, a ‘return to thing in themselves’, to the sources of the evident, to nascent vision.

Giacometti, Annette au chariot, 1950

The ‘return to things in themselves’, however, requires a ‘conversion of the gaze’: things hide from us the manner in which they appear; their truth always lies behind the screen of our knowledge. The immediate is not what comes at once or the most easily. Moreover, phenomenology seeks to make apparent the intentional activity of consciousness which ordinarily never appears but effaces itself instead in the light of what it shows. In Pomme sur le buffet, the painter shows us the intentionality of the gaze and the very transparency of this intentionality becomes visible: lines that construct vision, focused central vision and blurred peripheral. It is not a question of hesitation, nor a practical question of how to proceed, but rather a matter of the rising into the painter’s awareness—via phenomenological reduction—of the pure ‘spectacle of the world’ (relations in space, opposition of the whole and the part, identity and contradiction) that an interpretation of the painting as a memento mori or still life1 has hidden. The painter maintains a distance that enables him to see himself seeing before plunging into an infinite perceptual discovery. This is probably what gives the two 1937 paintings—Pomme sur le buffet and La Mère de l’artiste—their paradoxical luster of indifference: primordial vision, but vision suspended, acetic and ecstatic.

1 – Which, ‘into the bargain’, it is also.

GIACOMETTI: La Mère de l’artiste, 1937 | Pomme sur le buffet, 1937

It is in his reflections on intersubjectivity, however, paralleling those of Sartre, that Merleau-Ponty comes closest to Giacometti’s concerns. The other is always objectified by perception: the head becomes a mineral, a box. Is it possible to encounter the other as subject while nevertheless rendering his alterity? Alter ego and ego alter. Will every gaze, every smile end up as glass beads as they do for the Egyptian Scribe in the Louvre and in a grin such as we see in the Tête sur tige? Merleau-Ponty will discover with pleasure the way Giacometti, in a mobile gaze, will retrace in ever-renewed sketches the ways the model facing him appears. What do we see? Multiple vortices that render the flux of intersubjectivity, the moment of encounter; a work in progress where nothing is fixed.1 A never-ending effort at precision without ever resorting to reduction. It is the style of the other, his manner of appearing, his unique self-affirmation, that Giacometti will seek to capture. It is a technique that repels the contour, indicates and transcends volume: it must be recognized, and as Bachelard says, ‘One easily recognizes what one does not know’.

1 – When Merleau-Ponty asked Giacometti to make the frontispiece for a book on the history of philosophy, the artist chose to draw Heraclitus, the philosopher of perpetual change, after an antique bust.

Giacometti, Jean-Paul Sartre accoudé, 1949

Like Giacometti, Merleau-Ponty attempts to represent the articulation between the inside of the subject and the outside of the world. ‘Subject and object must be conceived as two abstract moments of a unique structure which is presence.’1

1 – Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Eye and Mind in The Merleau-Ponty Reader, ed. Leonard Lawlor & Ted Toadvine (Northwestern University Press, 2007) p. 430

Sabine Weiss, Alberto Giacometti Painting a Portrait of Annette, 1954 | Giacometti, Annette Seated, 1954

THIERRY DUFRÊNE: THREE BOOKS (TWO IN FRENCH, ONE IN ENGLISH)

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

II. GIACOMETTI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel, ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms’

Except for the sentences in italics, which quote Giacometti statements,* the following text did not in fact make the final cut of my novel; nevertheless, I give it here as it effectively evokes the artist. Note that in Mara, Marietta, the artist is a woman. (* Giacometti in Qu’est-ce qu’une tête? Michel Van Zele, ARTE France-Les Films d’ici, 2000, DVD)

The painter

The curve of the eye, the root of the nose, everything flows from that: Five strokes of black on the blank canvas begin the portrait. Index, thumb and middle finger grip the end of the long stem; his head through her eyes spurs the muscles in the hand that move the sable tuft. The outstretched arm descends and dips the brush in turpentine; a rag in the paletted hand absorbs the excess. She touches the brush to a blob on the palette, then again to the canvas extends her hand: On the taut surface his head comes into being. Upright he sits, hands falling easily between spread-apart legs, feet drawn in under the chair.

— Look at me! she calls.

Her captive, her quarry, he both resists and abandons himself to her gaze as she pursues her vision of an unencumbered man.

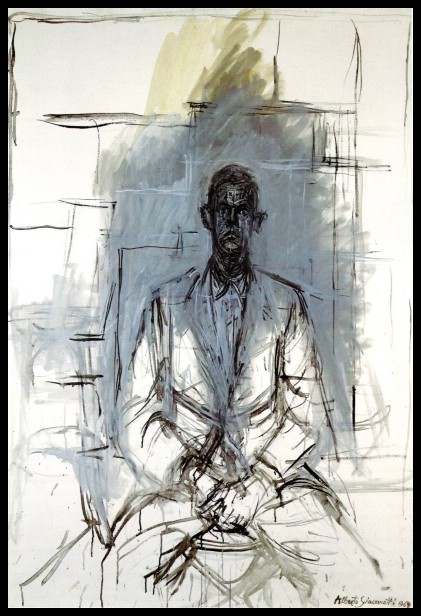

Giacometti, James Lord, 1964

The sculptor

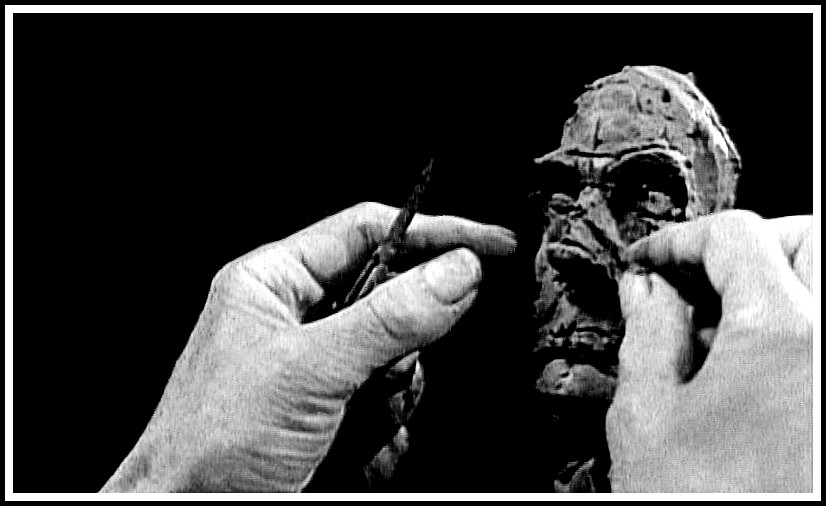

Into the wire egg of the armature she stuffs a crumpled sheet of newspaper; over the embryonic head she pulls a brown paper bag. Upon the surface she lays slabs of clay which deft thumbs work into one. Daylight floods the tiny studio, bringing a glow to the pulverized plaster and clay that dusts every object in it. On a countertop, tarnished knives, teaspoons and squeezed-out tubes of paint lie within a felled forest of brushes. Absorbed in their own world, three figurines stand behind a cluster of turpentine bottles. On a wall, a human figure emanates through a palimpsest of paint. Look! Down the middle of the head she lays a length of rolled clay; with the heel of her hand she works it in. Fingers rough-in nose, lips and chin; thumbs sweep back the matter from the midline of the face. She gazes at the man. His head unfolds itself in space; the eyes, the nose, the mouth—in the abyss of space everything is vulnerable. The fragility of all that lives impresses itself upon her; in her vision the head secretes the void around itself, the object and its envelope are one. Clay, a knife, a spoon, her fingers: These she will employ in a ceremony of intimacy and distance to capture death at work.

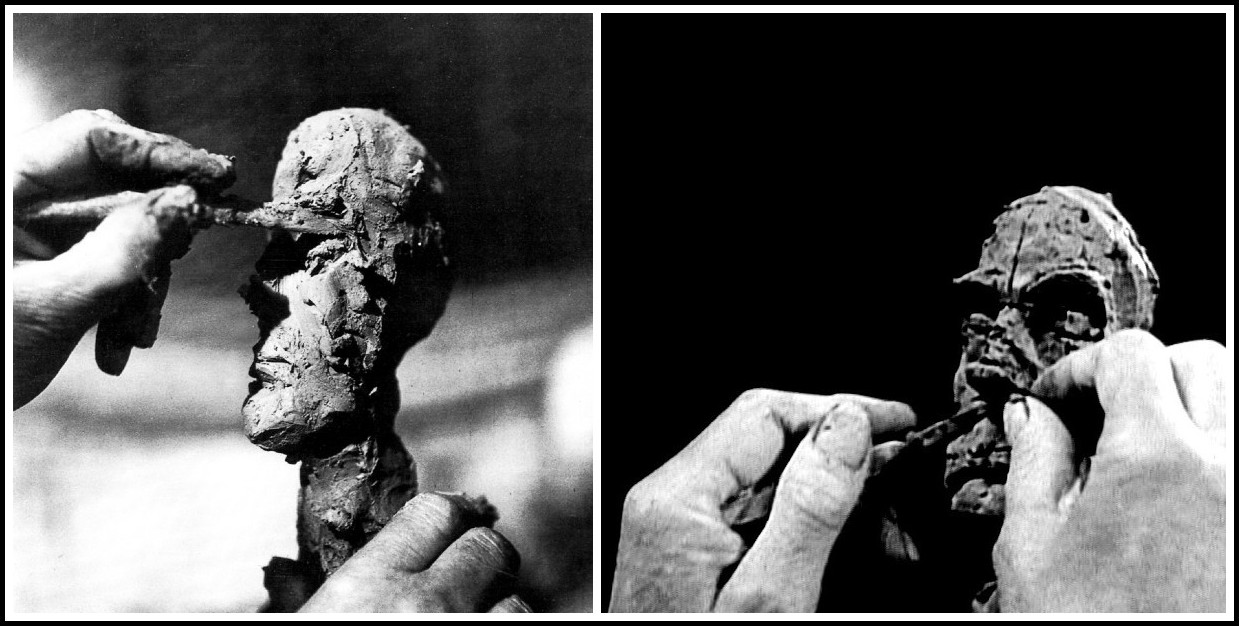

Giacometti Modelling a Head (Diego): Franco Cianetti, 1962 | Michel Van Zele (from Qu’est-ce qu’une tête? DVD)

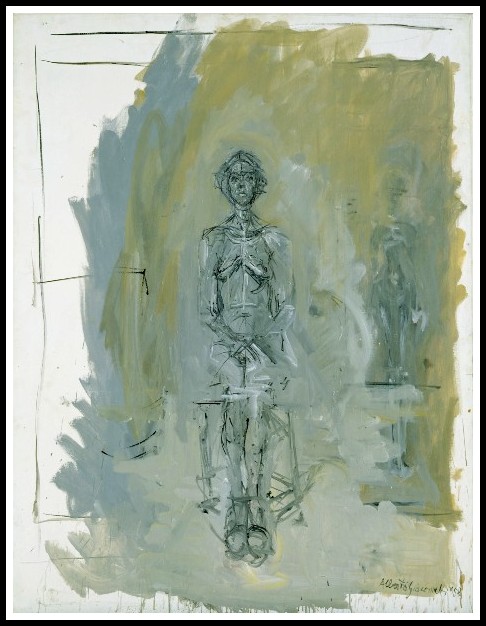

The painter

On the canvas in the painter’s studio, the body to below the knee is sketched in, but the head alone captures our gaze: All else is expelled. The painter in her crumpled blouse is tired, she lacks sleep but she must go on: She has just glimpsed an opening. She touches her brush to black and outlines the eye again: The head pulsates, trembles, struggles to affirm itself in space. Into turpentine she dips the brush then touches the tip to gray. Darting her eye between canvas and man, she circles the head in fluid strokes: One line questions the next, death inhabits the living. She sees the skull beneath the skin, she sees the soul inside: Before this head disappears, it must be given all its strength to resist! And yet she refuses to enclose her subject, to protect it from the void: She refuses the contour, she will not transfix her captive.

Giacometti, Maurice Lefebvre-Foinet, 1964

The sculptor

There is only success to the extent that there is failure; the more it fails, the more it succeeds: Not concerned with convention, the sculptor works her vision into the clay. Fingertips and eye gauge the volumes as she pinches and presses, proportioning the face. Down the cheek to the throat, redefining the facial planes, with steady pressure from her fingertips she drags a pliable blade. The terrible thing about dying is that you can only do it once. With a loop of wire she plucks a globule of clay out of the eyeball: the iris. The head becomes familiar and very close: Now she must make it as she sees it: inaccessible. Between the eyelid and the prominence of the orbit she drags the edge of a teaspoon. With damp fingertip she touches the eye, endeavoring to restore to the head what is most irreducible in it: Its solitude, what is left when illusions dissolve. With a penknife she opens up the lips: Identity shifts, and language speaks the loss.

Michel Van Zele, Giacometti Modelling a Head (Diego), from Qu’est-ce qu’une tête? DVD

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

SUBTRACTIVE ACTS

III. GIACOMETTI’S REPETITIOUS ART

Steven Bindeman

From Steven L. Bindeman, Silence in Philosophy, Literature, and Art (Leiden & Boston: Brill-Rodopi, 2017) pp. 93-96

Ernst Scheidegger, Giacometti painting a portrait of Annette

The act of repetition was a significant aspect of the artwork of Alberto Giacometti. James Lord1 and David Sylvester2 have both spoken about their experiences sitting for portraits by him. At the end of each and every day of painting from a live model, Giacometti would simply paint out his work to that point, slowly and gradually obliterating his subject through careful over-painting. With his sculptures, too, a similar act of subtraction within the wider act of repetition would take place. Here is how Sylvester described this: When he modeled from life, the coming and going of the form was gradual and continuous: he obliterated a part, rebuilt it, sharpened it, softened it, constantly modified here and there, sometimes slowed down and concentrated for hours on a detail, sometimes demolished sweepingly, but always retained the broad outlines of the mass. Giacometti seemed never to see the same face twice, since each time he would perceive different things in it differently.

1 – David Sylvester, Looking at Giacometti (NY: Henry Holt, 1997) p. 83

2 – James Lord, A Giacometti Portrait (NY : Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980) passim

Giacometti, Annette Seated, 1958

Giacometti clearly worked through subtractive acts. His thoughts on the subject present an uncommon intensity of focus: I just wanted to make ordinary heads. That never worked out. But since I always failed, I always wanted to make a new attempt. I wanted once and for all to make a head as I saw it. Since I never succeeded, I persevered in the effort. The more I looked at the model, the more the screen between his reality and mine grew thicker. One starts by seeing the person who poses, but little by little all the possible sculptures of him intervene. And when there were no more sculptures, there was such a complete stranger that I no longer knew whom I saw or what I was looking at.1 The motive that makes one work is surely to give a certain permanence to what is fleeting.2 If one could actually make a head as it is, that would mean one can dominate reality. It would mean total knowledge, Life would stop. It’s curious that I can’t manage to make what I see. To do that, one would have to die of it.3

1 – James Lord, A Giacometti Portrait (NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1980) p. 165

2 – Ibid., p. 307

3 – Ibid., p. 417

GIACOMETTI: Annette VII, 1962 | Annette IX, 1964 | Annette X, 1965

Giacometti spoke of an internal tension between the unattainable perfection of what he saw with his mind’s eye, and the mundane reality of what he saw with his physical ones. The constant rejection of this mundanity might even be seen as a kind of philosophical quest, for the purely eidetic essential thing. This would also explain why Giacometti found it far easier to sculpt by memory than with live subjects, since with the imperfect evidence of his memory there would be no need to reject anything. Giacometti’s sculptures seem to present figures as if they were captured during the perception of actual time passing; they carry a charged atmosphere around them and appear to expand and contract in their atmosphere like a lung. His art conveys precisely why our sensations of reality cannot be conveyed precisely. In looking at his sculptural portraits we experience the artist’s experience of his distance from his subjects. What seems to have been especially frustrating to Giacometti was the realization that his sculptures as human figures were separate from his sculptures as objects, their imagery detachable from their inherent physical nature. He realized that: The model can go on standing still forever, but the work will nonetheless be the product of an accumulation of memories none of which is quite the same as any other, because each of them is affected by what has gone before, by the continually changing relation between all that has already been put down and the next glance at the model.1

1 – David Sylvester, Looking at Giacometti (NY: Henry Holt, 1997), p. 36

GIACOMETTI: Buste de Diego, 1954 | Diego au chandail, 1953 | Diego au manteau, 1954

While Giacometti is best known for his sculptures, at a key point in his life it was painting that provided him with a way out of a paralyzing dilemma. In his quest for achieving the creation of something real, he had gotten stymied by the necessity of the sculptor’s art—or at least as he still envisaged it—to shape his portraits without reference to their surroundings. His painted portraits of the time, however, enabled him to set the depth and confines of the optical field which existed between the model and himself looking at it. And suddenly the object in front of him (in this case an apple, in what became the painting Apple on the Sideboard, 1937) was not just an apple, but became that particular apple, present at that particular moment on that sideboard at the far end of the room. In this instance of Giacometti’s art, the desire to capture the mystery of existence had taken precedence over merely depicting the aspects of the thing seen. Because he had yielded to the impulse to simply paint, and then to reduce the object he intended to paint to its bare essence (by removing everything extraneous to the scene, including a bowl, some plates, some flowers, and three apples), he discovered a way to express Being. He had found a way to reveal its presence, where previously he had been able to reproduce only the appearance of his models in terms of their external form.1

1 –Yves Bonnefoy, Alberto Giacometti: A Biography of His Work (Paris: Flammarion, 2012) p. 256

Giacometti, Apple on the Sideboard, 1937

There is also a self-defeating, ironic quality to Giacometti’s work. He once noted that: If I managed to do what I was aiming at, it would be something almost intolerable to look at because it would seem real, or give too much the illusion of being real’.1 Giacometti wanted what he couldn’t have, even as he knew he couldn’t have it. If the sculpture appears as too real yet cannot move, he said, then it’s little more than a dead object. And if you give it eyes, and paint them on, and they don’t move, then it becomes an unpleasant object. What gives a sculpture reality is that the viewer sees it as real because of its pent-up energy, its tension. So tension takes the place of movement; it’s as if it were movement. And then the thing becomes tolerable.2 It is not surprising that Giacometti’s works recede from view even as we look at them, for what is left has been so pared away that they appear to us as if seen from a distance, even up close.

1 – Yves Bonnefoy, Alberto Giacometti: A Biography of His Work (Paris: Flammarion, 2012) p. 128

2 – Ibid., pp. 127-128

GIACOMETTI: Grande femme III, 1960 | Femme de Venise, 1956 | Grande femme VI, 1960

Blanchot noticed this feature in Giacometti’s work, too: When we observe Giacometti’s sculptures there comes a point at which they are no longer subjected to the fluctuations of appearance or the laws of perspective. We see them absolutely: not cut down to size but abstracted from size, sizeless, and in space, dominating space through their ability to replace it by an intractable, inexistent depth—the depth of imagery. This point at which we see time as sizeless involves us in infinity and is the point where ‘here’ coincides with ‘nowhere.’1 Blanchot’s insight brings us to Bachelard’s observation about the poetic moment’s capacity to liberate a person from the imprisonment of horizontal time. Our experience of authentic works of art, like with the sculptures of Giacometti, begins only when this form of external time has been stopped.

1- Maurice Blanchot, The Sirens’ Song: Selected Essays by Maurice Blanchot. Gabriel Josipovici, ed., S. Rabinovitch, tr. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982) p. 119

GIACOMETTI: Trois hommes qui marchent, 1948 | Homme qui marche sous la pluie, 1948 | Quatre femmes sur socle, 1950