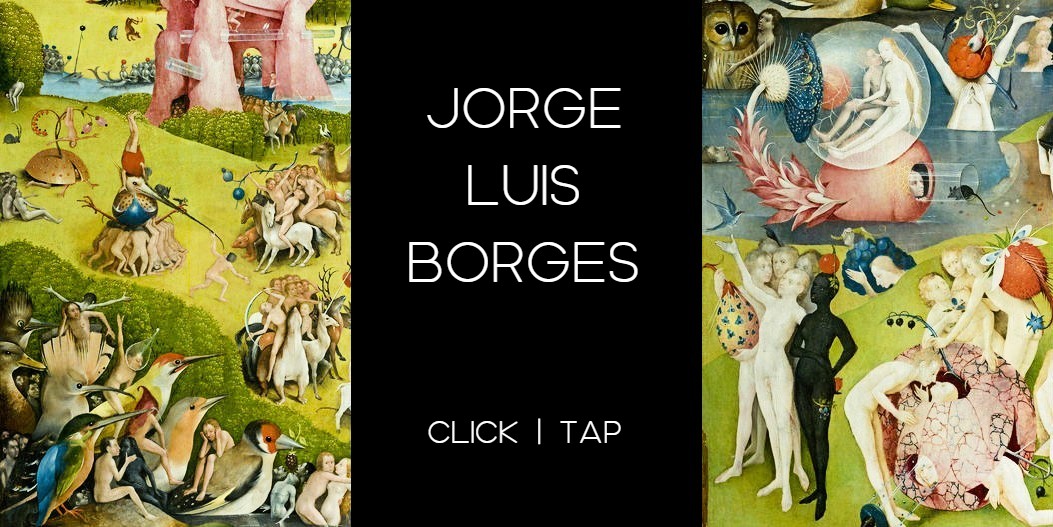

Rimbaud I

Le Dormeur du val | Chanson de la plus haute tour | Veillées I

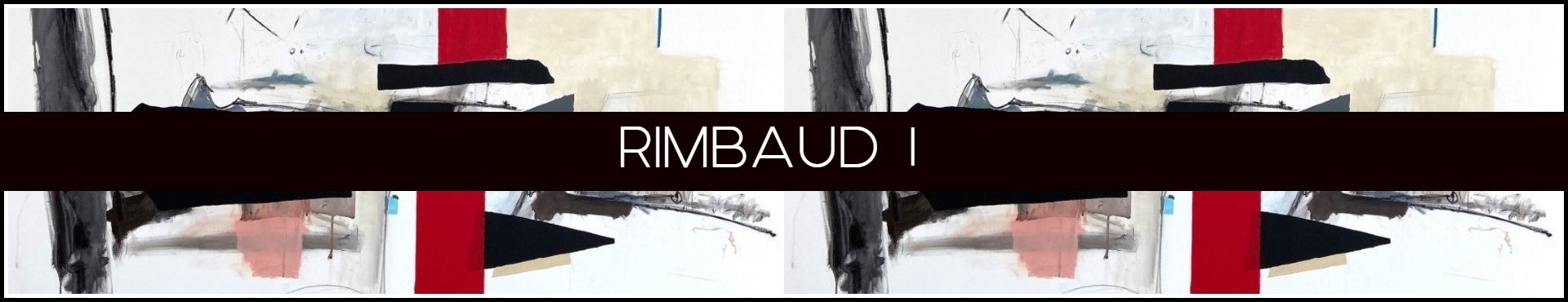

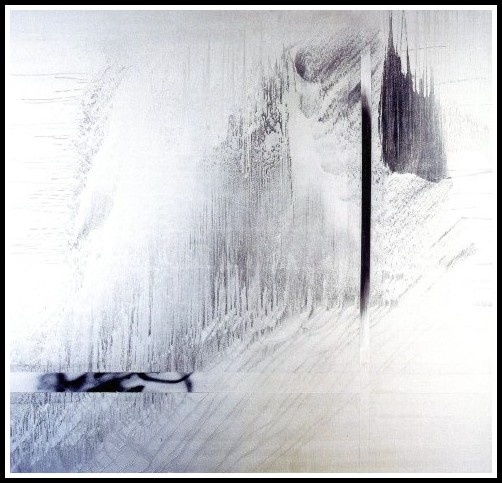

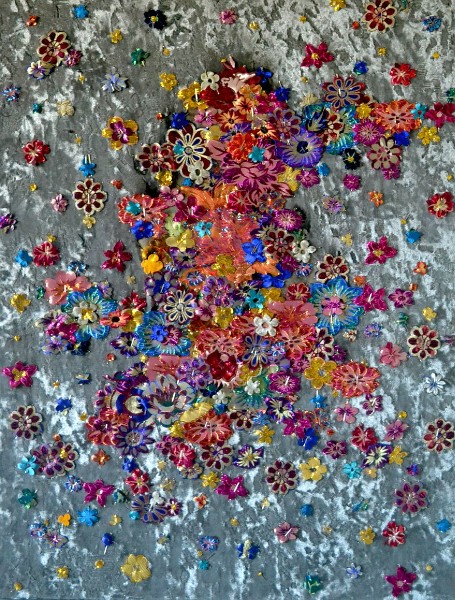

Adrienn Krahl, Tienmu Horizon, 2021 (detail)

LE DORMEUR DU VAL

Arthur Rimbaud

C’est un trou de verdure où chante une rivière,

Accrochant follement aux herbes des haillons

D’argent ; où le soleil, de la montagne fière,

Luit : c’est un petit val qui mousse de rayons.

Un soldat jeune, bouche ouverte, tête nue,

Et la nuque baignant dans le frais cresson bleu,

Dort ; il est étendu dans l’herbe, sous la nue,

Pâle dans son lit vert où la lumière pleut.

Les pieds dans les glaïeuls, il dort. Souriant comme

Sourirait un enfant malade, il fait un somme :

Nature, berce-le chaudement : il a froid.

Les parfums ne font pas frissonner sa narine ;

Il dort dans le soleil, la main sur sa poitrine,

Tranquille. Il a deux trous rouges au côté droit.

Adrienn Krahl, Tienmu Horizon, 2021

A SLEEPER IN THE VALLEY

Arthur Rimbaud | Wyatt Mason

A green hole where a river sings;

Silver tatters tangling in the grass;

Sun shining down from a proud mountain:

A little valley bubbling with light.

A young soldier sleeps, lips apart, head bare,

Neck bathing in cool blue watercress,

Reclined in the grass beneath the clouds,

Pale in his green bed showered with light.

He sleeps with his feet in the gladiolas.

Smiling like a sick child, he naps:

Nature, cradle him in warmth: he’s cold.

Sweet scents don’t tickle his nose;

He sleeps in the sun, a hand on his motionless chest,

Two red holes on his right side.

Jacqueline Humphries, Untitled, 2006

‘LE DORMEUR DU VAL’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 7

And from London too she brought back music: Not the radio fare of ‘Nights in White Satin’ and ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’, but ‘John, I’m Only Dancing’ and ‘Virginia Plain’. One rainy day she played you The Doors, casting Chinese shadows on the wall to ‘Riders on the Storm’; you quickly got the knack of it, and together to ‘Hyacinth House’ you improvised a shadow-play. Then she played you Sapho’s fiery version of ‘Le Dormeur du val’…

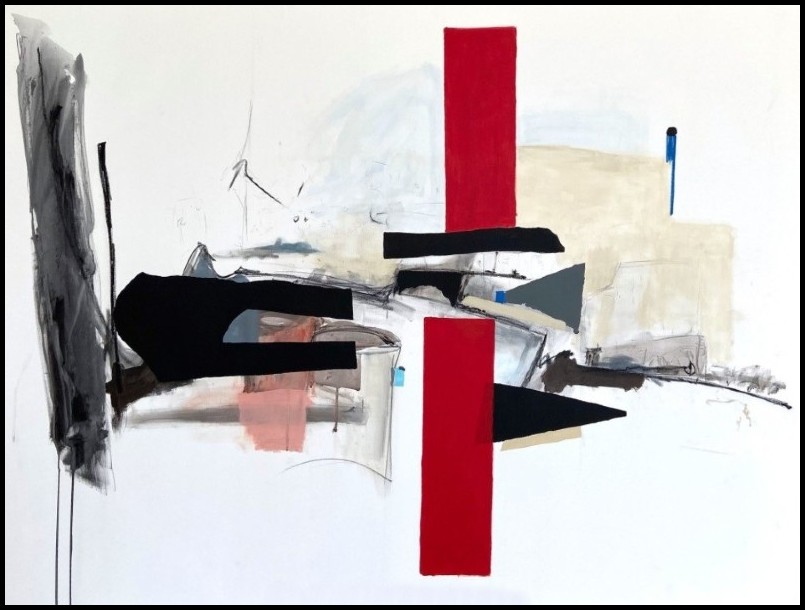

Sapho

CHANSON DE LA PLUS HAUTE TOUR

Arthur Rimbaud

Oisive jeunesse

A tout asservie,

Par délicatesse

J’ai perdu ma vie.

Ah ! Que le temps vienne

Où les cœurs s’éprennent.

Je me suis dit : laisse,

Et qu’on ne te voie :

Et sans la promesse

De plus hautes joies.

Que rien ne t’arrête,

Auguste retraite.

J’ai tant fait patience

Qu’à jamais j’oublie ;

Craintes et souffrances

Aux cieux sont parties.

Et la soif malsaine

Obscurcit mes veines.

Ainsi la prairie

A l’oubli livrée,

Grandie, et fleurie

D’encens et d’ivraies

Au bourdon farouche

De cent sales mouches.

Ah ! Mille veuvages

De la si pauvre âme

Qui n’a que l’image

De la Notre-Dame !

Est-ce que l’on prie

La Vierge Marie ?

Oisive jeunesse

A tout asservie,

Par délicatesse

J’ai perdu ma vie.

Ah ! Que le temps vienne

Où les cœurs s’éprennent !

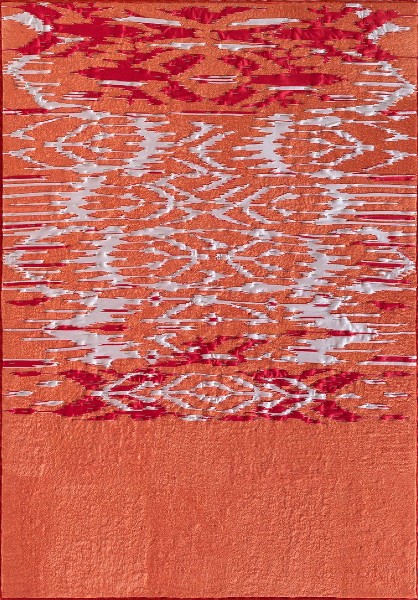

Jacqueline Humphries, Pile, 2008

SONG FROM THE TALLEST TOWER

Arthur Rimbaud | Wyatt Mason

Idle youth,

Slave to all,

Sensitivity

Was my fall.

Let the moment come

When hearts will be one.

Just say: let go,

Disappear:

Without hope

Of greater joy.

Let nothing impede

August retreat.

I’ve been so patient

I nearly forgot;

Fear and suffering

Have taken wing.

Unwholesome thirst

Stains my veins.

So the meadow

Surrendered,

Lush and blossoming

With incense and weeds,

And the fierce buzzing

Of a hundred flies.

A thousand widowings

Of the indigent heart

Left with nothing

But our lady’s face—Nôtre Dame!

Can one really pray

To the Virgin Mary, today?

Idle youth,

Slave to all,

Sensitivity

Was my fall.

Let the moment come

When hearts will be one.

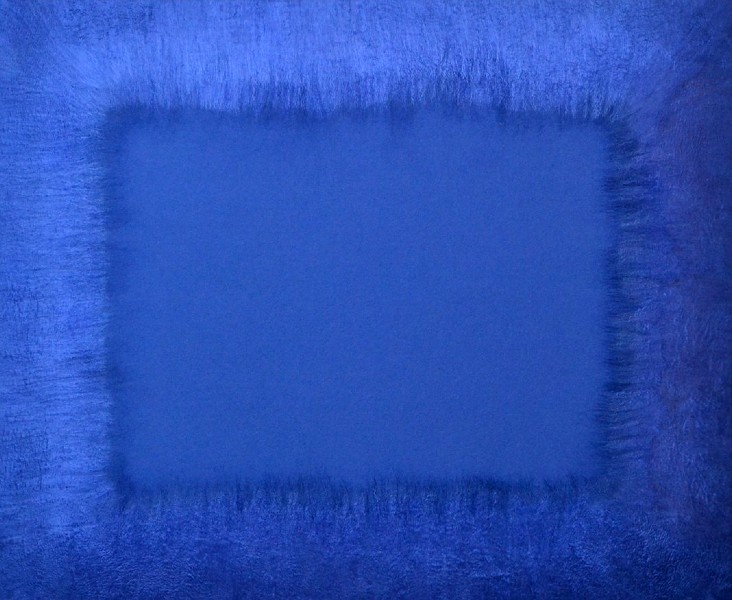

Jacqueline Humphries, Blue, 2007

‘CHANSON DE LA PLUS HAUTE TOUR’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 7

… you constructed a turban from twists of astrakhan and jersey, put it on your head and passionately declaimed ‘Chanson de la plus haute tour’.

VEILLÉES I

Arthur Rimbaud

C’est le repos éclairé, ni fièvre ni langueur, sur le lit ou sur le pré.

C’est l’ami ni ardent ni faible. L’ami.

C’est l’aimée ni tourmentante ni tourmentée. L’aimée.

L’air et le monde point cherchés. La vie.

̶ Était-ce donc ceci ?

̶ Et le rêve fraîchit.

Jacqueline Humphries, Indigo, 2007

VIGILS I

Arthur Rimbaud | Wyatt Mason

Enlightened leisure, neither fever nor languor, in a meadow or a bed.

A friend neither ardent nor weak. A friend.

A love neither tormenting nor tormented. A love.

The air and the world, unsought. A life.

̶ Was this it?

̶ And the dream grows cool.

Jacqueline Humphries, Mercury’s Moon, 2006

‘VIGILS I’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 13: Tasha

She then gave me a translation of her first novel, The Dream Grows Cool. I opened it on the epigram: ‘Neither fever nor languor, in a meadow or a bed. A friend neither ardent nor weak. A friend. The air and the world, unsought. A life’. Rimbaud, Vigils I. I took her in my arms and pressed her body to mine. She kissed me. Then, without a word on our breath, we said goodbye.

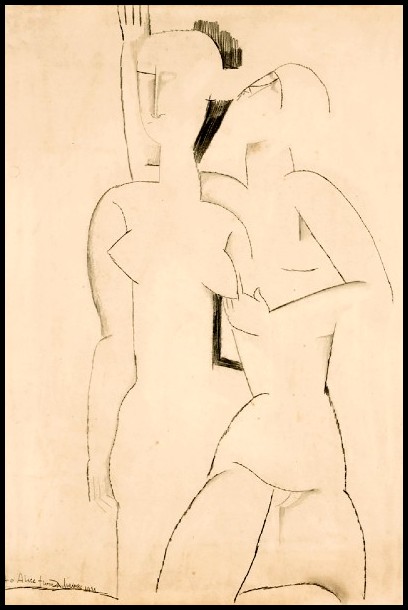

Ossip Zadkine, Le Couple, 1921

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

YVES BONNEFOY ON RIMBAUD

From Yves Bonnefoy, Notre besoin de Rimbaud (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2009) pp. 67, 246-47.

Translated here by Richard Jonathan

To understand Rimbaud read Rimbaud, strive to separate his voice from the cacophony of other voices that have become mixed up with his. There is no need to look far, no need to look elsewhere, when we have close at hand what Rimbaud himself tells us. Few writers have sought to know themselves as determinedly as he has, few have tried as doggedly to define and transform themselves and become, through self-knowledge, a different person. There is nothing more serious than this quest: let us take it seriously.

Gulnur Mukazhanova, Post-Nomadic Reality #1, 2021

The grandeur of Rimbaud will always reside in his refusal of the little freedom that in his time and place he could have made his, a stance taken in order to bear witness to man’s alienation as well as to call him to shift from joyless consent to tragic confrontation with the absolute. It is this decision—and the firmness with which he upheld it—that make Rimbaud’s poetry the most liberating in the French language. A tomb, if you like, for salvation forsaken, for humble joys foresworn, for a life separated by its own exacting standards from all equilibrium and joy. Yet the Phoenix of freedom, the one who forms its body from the hopes consumed in the fire, comes to beat this air with its new wings.

Gulnur Mukazhanova, Moment of the Present #8, 2019

THE BREVITY OF THE ESSENTIAL: YVES BONNEFOY ON ‘ILLUMINATIONS’

From Yves Bonnefoy, Notre besoin de Rimbaud (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2009) pp. 407-09.

Translated here by Richard Jonathan

To dive at once into a body of work whose propositions take form with clarity and vehemence is to encounter thought in its nascent state: thought demonstrated and developed has already lost its freshness. In Rimbaud this dive is very revealing. More than with most poets, this depth in him leaps up, literally, before the person sounding it. Facing life with impatience, holding oneself to strict account, makes it rid itself, violently, of almost everything that ordinarily accompanies and supports intuition and feeling. Rimbaud never tries to prove anything: he goes straight to what he considers the absolute truth now, at the present moment, believing that this approach enables him to access what is essential in the human condition. And so he writes: ‘Love must be reinvented’. Or: ‘True life is absent’. Or: ‘One must be absolutely modern’.

Gulnur Mukazhanova, Moment of the Present #24, 2021

What exactly does this brevity signify? A hope. Yes, Rimbaud feels (as he wrote in a letter to Paul Demeny) that he is putting an end to centuries of error, if not of lies; he expects his revelations—‘what I’m saying is oracular’—to spread like a great salutary fire in a redeemed society. This elliptical intensity expresses an immense desire that imagines it will soon be fully satisfied. So let us join this boy in his cry, a cry almost of joy: it will be more a sharing of expectation than an expression of understanding. Even if it will amount, sometimes, to no more than sharing a dream, it will still be a refusal to consign revolt to futility and the rebel to solitude.

Gulnur Mukazhanova, Post-Nomadic Reality #22, 2019

After that we will stay close to Rimbaud when, in a second phase of his experience, he will understand—yes, in solitude—that he will have failed to ‘change life’. This conviction came to him early, and cruelly, leaving no delusions that any lingering hope could harbor. ‘Along rivers, little children choke down curses’ (‘Youth’, Illuminations), he wrote then, speaking for many others than himself in this unhappy society. There is in Rimbaud, so stirred with desires, an admirable lucidity that quickly recognizes impossibility. He knows his own inhibitions, which he blames on the Christian exaltation of suffering. ‘Enough tears!’ the ‘Drunken Boat’ exclaims in its last stanzas: an exultation, first, of a crude freedom conquered. No other poet has as forcefully and in so few words expressed the dead ends into which the West has wandered. Rimbaud’s departure for Africa, an act expressing a judgement that he wants to be final, is the most striking example of the impetuous brevity of his speech. Indeed, it shuts down discourse and contents itself with saying: ‘Enough of Europe!’. Meaning: ‘Departure for fresh affection and noise!’ (‘Departure’, Illuminations).

Gulnur Mukazhanova, Moment of the Present #12, 2019

Yes, let us stay with Rimbaud, and listen to these Illuminations in which the child who feels himself damned and vanquished devotes himself to his dreams, alone with ‘memories that come to visit’ (‘Youth’, Illuminations). After the searing intensity of the denunciations and demands, after the exhilaration of the revolt that believed it had prevailed, Rimbaud wrote the Illuminations for himself alone, a work one may consider impenetrable. But no, it is not, and whoever dives into these fast-flowing currents, among these patches of shadow, will bring back the glitter of a dream light: the light we would see in the morning if our minds were more attuned to the promise of the world.

Gulnur Mukazhanova, Moment of the Present #26, 2021