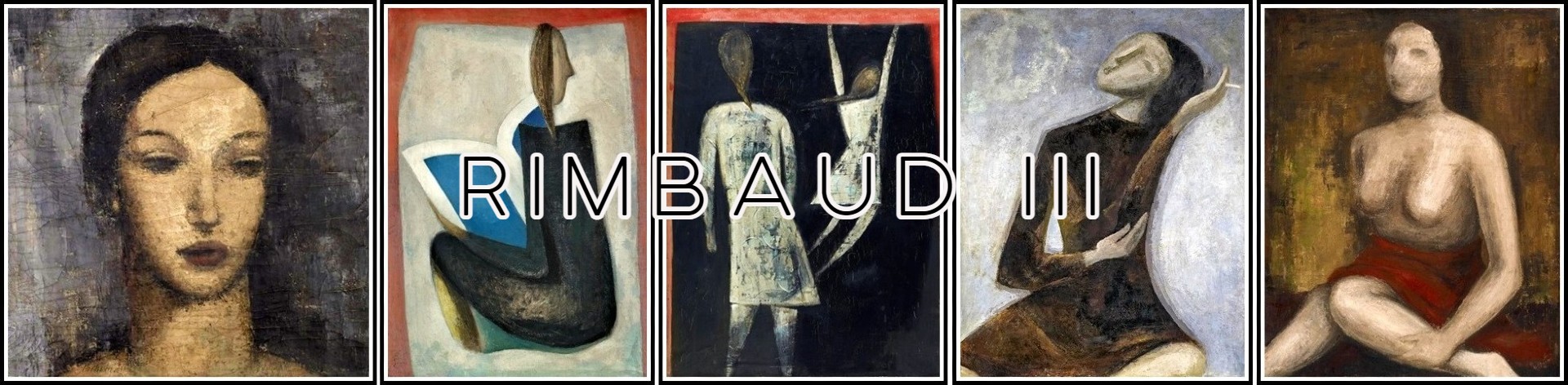

Rimbaud III

Mes petites amoureuses

MES PETITES AMOUREUSES | MY LITTLE LOVES

Arthur Rimbaud | Wyatt Mason

Un hydrolat lacrymal lave

Les cieux vert-chou

Sous l’arbre tendronnier qui bave,

Vos caoutchoucs

Blancs de lunes particulières

Aux pialats ronds,

Entrechoquez vos genouillères,

Mes laiderons !

Nous nous aimions à cette époque,

Bleu laideron !

On mangeait des œufs à la coque

Et du mouron !

Un soir, tu me sacras poète,

Blond laideron :

Descends ici, que je te fouette

En mon giron ;

J’ai dégueulé ta bandoline,

Noir laideron ;

Tu couperais ma mandoline

Au fil du front.

Pouah ! mes salives desséchées,

Roux laideron,

Infectent encore les tranchées

De ton sein rond !

A teary tincture slops

Over cabbage-green skies:

Beneath saplings’ dewy drops,

Your white raincoats rise

With strange moons

And ripe spheres,

Knock your knees together,

My ugly little dears.

How we loved each other once:

Eating chickweed

And soft-boiled eggs,

My ugly, blue-eyed dear

One night you hailed me poet:

You hopped on my lap

For a spanking,

My ugly, blonde dear

Your brilliantine made me puke:

Your heavy brow

Could break a guitar,

My ugly, dark-haired dear

My dry jets of sputum,

Fester between

Your round breasts,

My ugly, red-headed dear

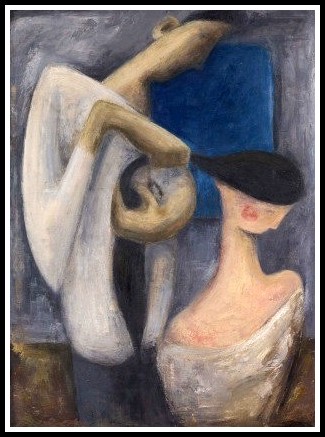

Peter Herkenrath, Two Figures

Ô mes petites amoureuses,

Que je vous hais !

Plaquez de fouffes douloureuses

Vos tétons laids !

Piétinez mes vieilles terrines

De sentiment ;

– Hop donc ! soyez-moi ballerines

Pour un moment !…

Vos omoplates se déboîtent,

Ô mes amours !

Une étoile à vos reins qui boitent

Tournez vos tours !

Et c’est pourtant pour ces éclanches

Que j’ai rimé !

Je voudrais vous casser les hanches

D’avoir aimé !

Fade amas d’étoiles ratées,

Comblez les coins !

– Vous crèverez en Dieu, bâtées

D’ignobles soins !

Sous les lunes particulières

Aux pialats ronds,

Entrechoquez vos genouillères,

Mes laiderons !

My little loves:

I hate you.

I hope your ugly tits blossom

With painful sores.

You trample my stores

Of feeling;

And then, voilà: you dance

For me once more.

Your shoulders dislocate,

My loves.

Stars brand your hobbled hips

While you do your worst.

And yet, for these sides of beef,

I made the lines above:

Hips I should have broken,

I filled with acts of love.

Guileless clumps of fallen stars

Accumulate below;

Saddled with trifling concerns

You’ll die with God, alone.

Beneath strange moons

And ripe spheres,

Knock your knees together

My ugly little dears!

Peter Herkenrath, Young Woman Seated, Smoking

‘MES PETITES AMOUREUSES’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 6

Fearless and carefree, that was the reputation you gained—a sign of your success, you believed, in disguising your suffering. Indeed, proving your ability to conceal your feelings, demonstrating your independence from your peers, became a source of great satisfaction to you.

O mes petites amoureuses,

Que je vous hais!

Plaquez de fouffes douloureuses

Vos tétons laids!

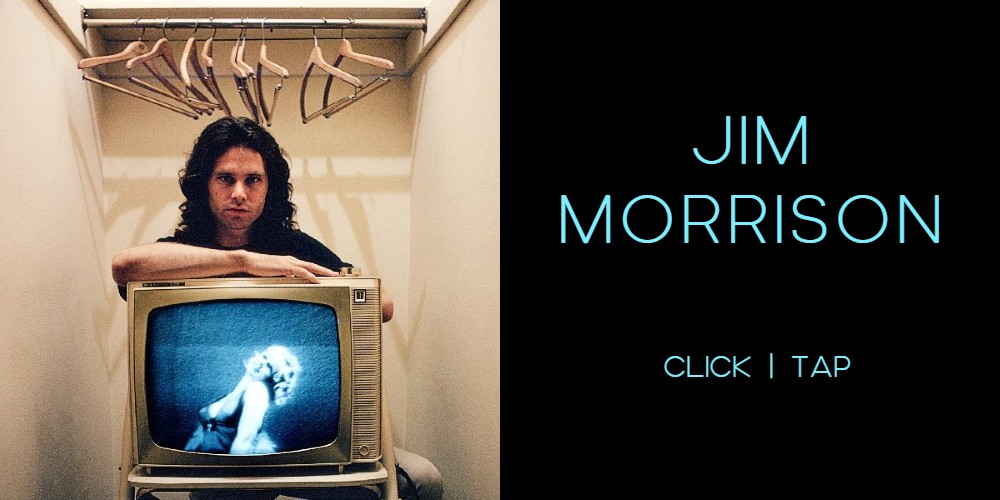

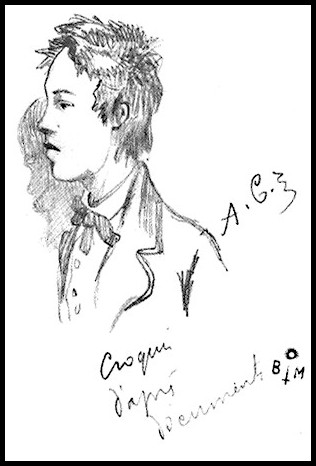

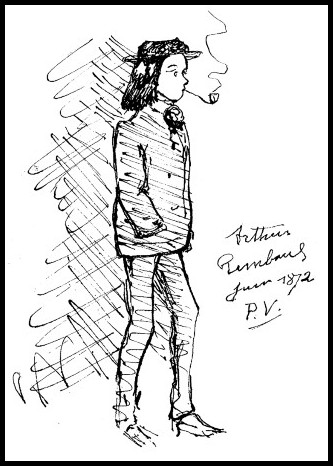

Rimbaud became your hero. On your wall you pinned Rimbaud et son ombre, the sketch by Cazals: Your resemblance to the poet in this pencil drawing—the carelessly-cropped hair, the finesse of the profile—confirmed your affinity with him.

Cazals, Rimbaud et son ombre

Fade amas d’étoiles ratées,

Comblez les coins!

— Vous crèverez en Dieu, bâtées

D’ignobles soins!

Next to Cazal’s sketch you pinned Verlaine’s drawing, Rimbaud à Paris: Hand in pocket, hat on head, he stands in profile, smoking his pipe. For you a Gitane would do: Sitting on your bed, you’d blow smoke rings of love to the boy whose poetry so engaged your emotion.

Blancs de lunes particulières

Aux pialats ronds,

Entrechoquez vos genouillères,

Mes laiderons!

But if you were proud of your ability to conceal your feelings, if you took pleasure in your independence from your peers, did you realize that in cutting off your hair you had cut the link between yourself and your body? As that body ripened, your inability to connect to it gave rise to greater and greater anxiety.

Verlaine, Rimbaud à Paris

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 10

Is one ever finished with adolescence, then? … And what about Gudrun’s ingenious transcription of this dangerous passage? Neither Narcissus bedazzled by her new-found sex nor a nymph bent on seduction, she did not recoil before her discoveries nor rush into deploying her powers; no, her rocking before me demanded nothing but recognition. Thus I offered her Rimbaud, an interpretation for her sensations, a fellow adolescent about to walk the world.

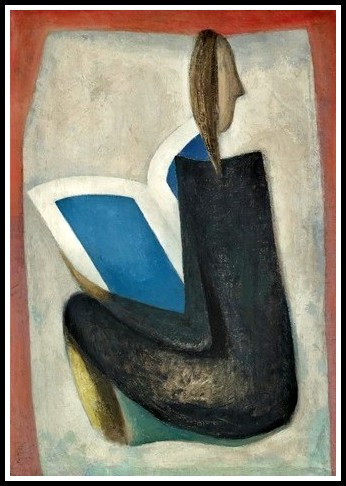

Peter Herkenrath, The Beautiful Book, 1948

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 1: Lilo

We speak of Egon Schiele, dead at twenty-eight. Lilo says she likes the drawings on her wall, but she prefers Egon’s earlier work. I agree that Edith’s too old to be a girl like Rimbaud (my first gift to Lilo) but not Gerti, Wally and the working-class girls.

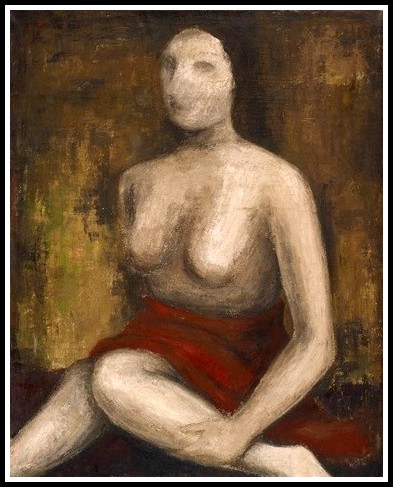

Peter Herkenrath, Nude

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 10: Bettina

̶ Yes. It’s pure cinema. It struck a chord in me, as a girl.

̶ And as a boy?

̶ I’m not Rimbaud.

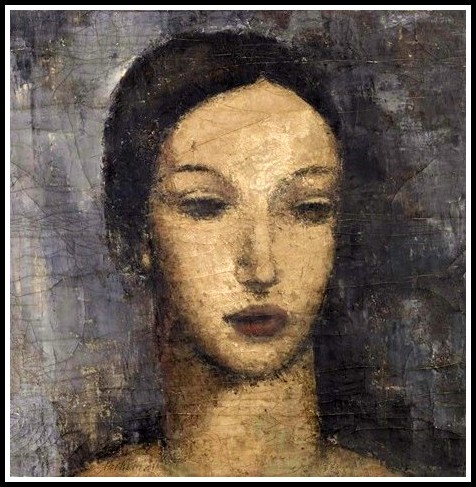

Peter Herkenrath, Head of a Woman

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 4

̶ But what if she never decides?

I jump in to answer Brynjar’s question:

̶̶ Then she’ll be an artist, a dancer.

̶ A dancer?

̶ Yes. She’ll run garlands from star to star and she’ll dance.

̶ Sprague, what are you saying?

̶ I’m saying that in the house of the soapmaker, those who don’t fall learn how to dance.

Suspended between delight and unease, Brynjar hestitates. I myself am surprised by my pirouette from the poem to the proverb. Why do I always associate Rimbaud with girls’ becoming? Because of you, of course! Because of your evocation—way back when, in our conversation on the floor—of what this boy has meant to you.

̶̶ Maybe, Sprague. Maybe she’ll become a dancer.

̶ I think she will.

Peter Herkenrath, Hairdressing, 1945

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RIMBAUD I (Le Dormeur du val | Chanson de la plus haute tour | Veillées I)