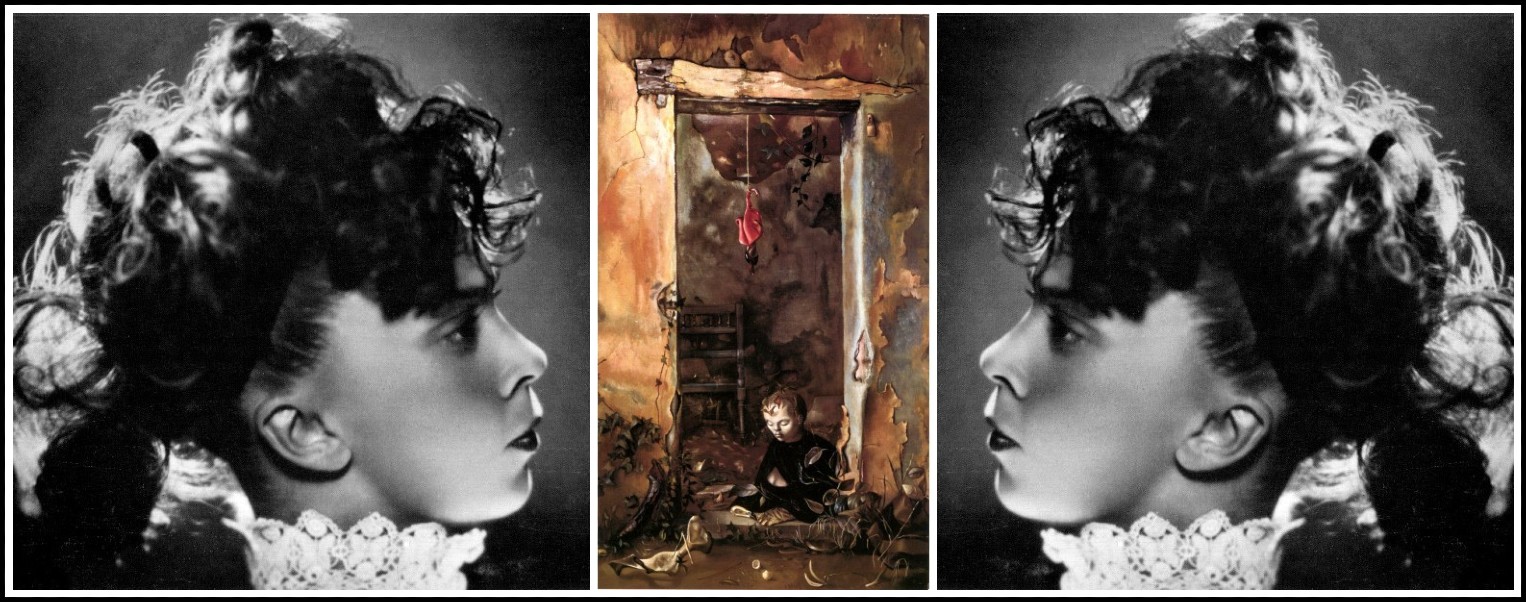

Fini, Colquhoun, Varo, Carrington, Agar, Rahon

WOMEN SURREALIST ARTISTS AND THE HERMETIC TRADITION – PART 1

Whitney Chadwick

Abbreviated from Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (London: Thames and Hudson, 1985/2021) pp. 230-252

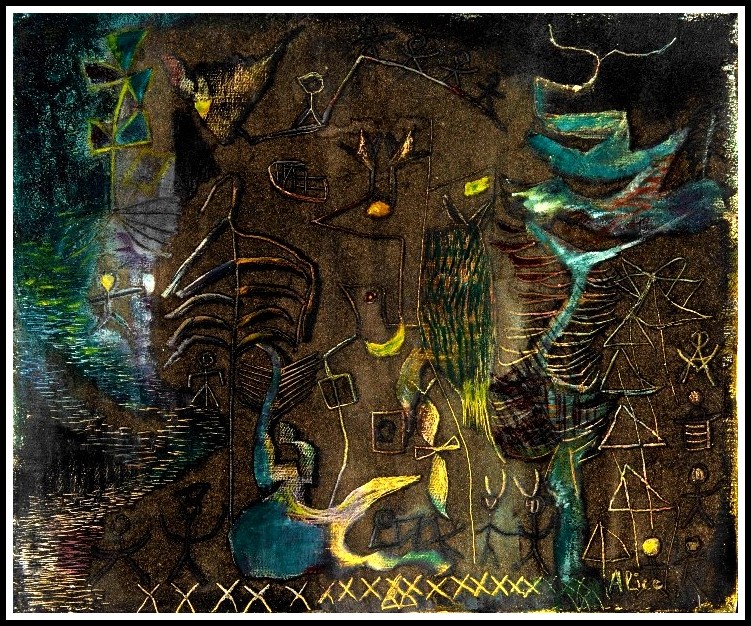

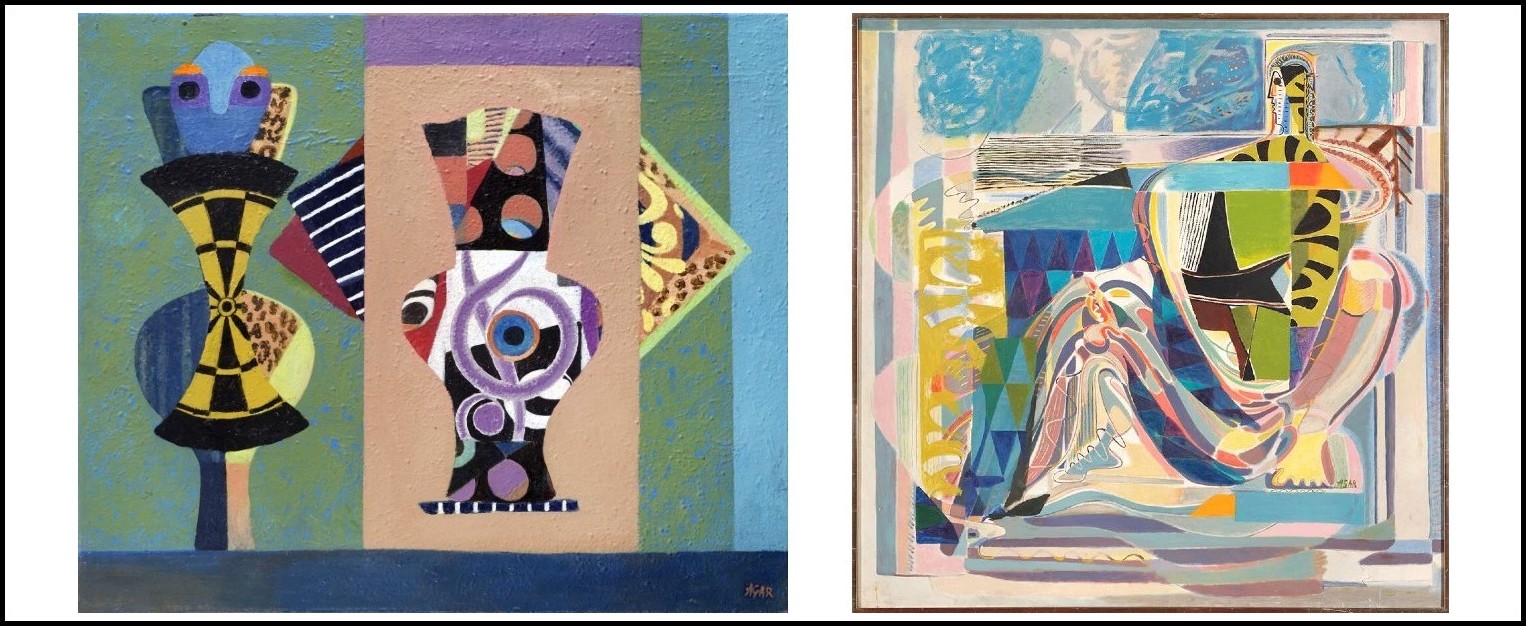

Alice Rahon, Boîte à musique III, 1945

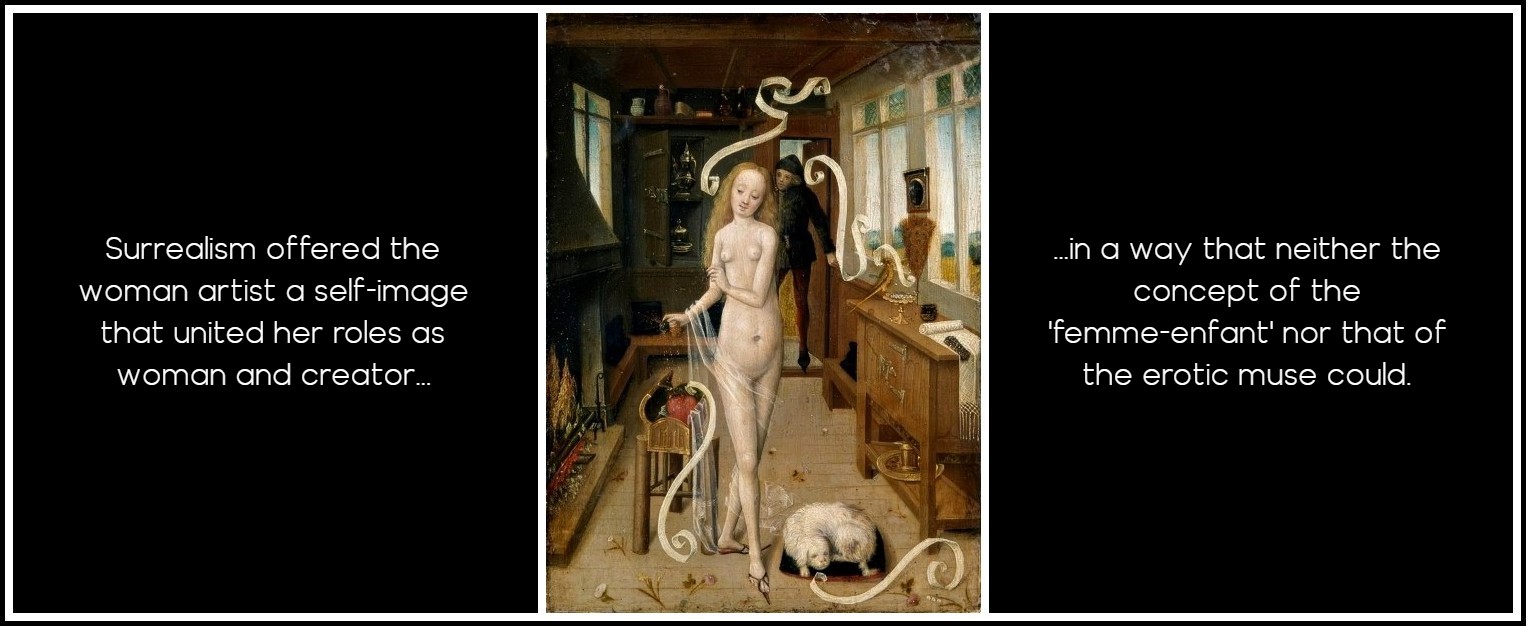

‘Witches they are by nature. It is a gift peculiar to woman and her temperament,’ wrote Jules Michelet in La Sorcière, an imposing study of the witch in medieval society that profoundly influenced Breton’s thinking on the subject of woman. He read and absorbed the book’s anti-positivist message, and its thesis tracing the witch’s historical origins to a time in which labor was divided between men who hunted and fought and woman who worked by her wits and her imagination, and he was quick to adapt Michelet’s conclusions to Surrealism. Among them was a view of the sorceress as a being endowed with two creative gifts: the inspiration of lucid frenzy and the sublime power of parthenogenesis or unaided conception. Both characteristics would become essential aspects of the act of creation in a Surrealist context; both pointed toward a seminal role for woman in the creative process. In recognizing her intuitive connection with the magic realm of existence that governed creation, Surrealism offered the woman artist a self-image that united her roles as woman and creator in a way that neither the concept of the femme-enfant nor that of the erotic muse could.

German/Netherlandish School, Der Liebeszauber (The Love Spell), c. 1500

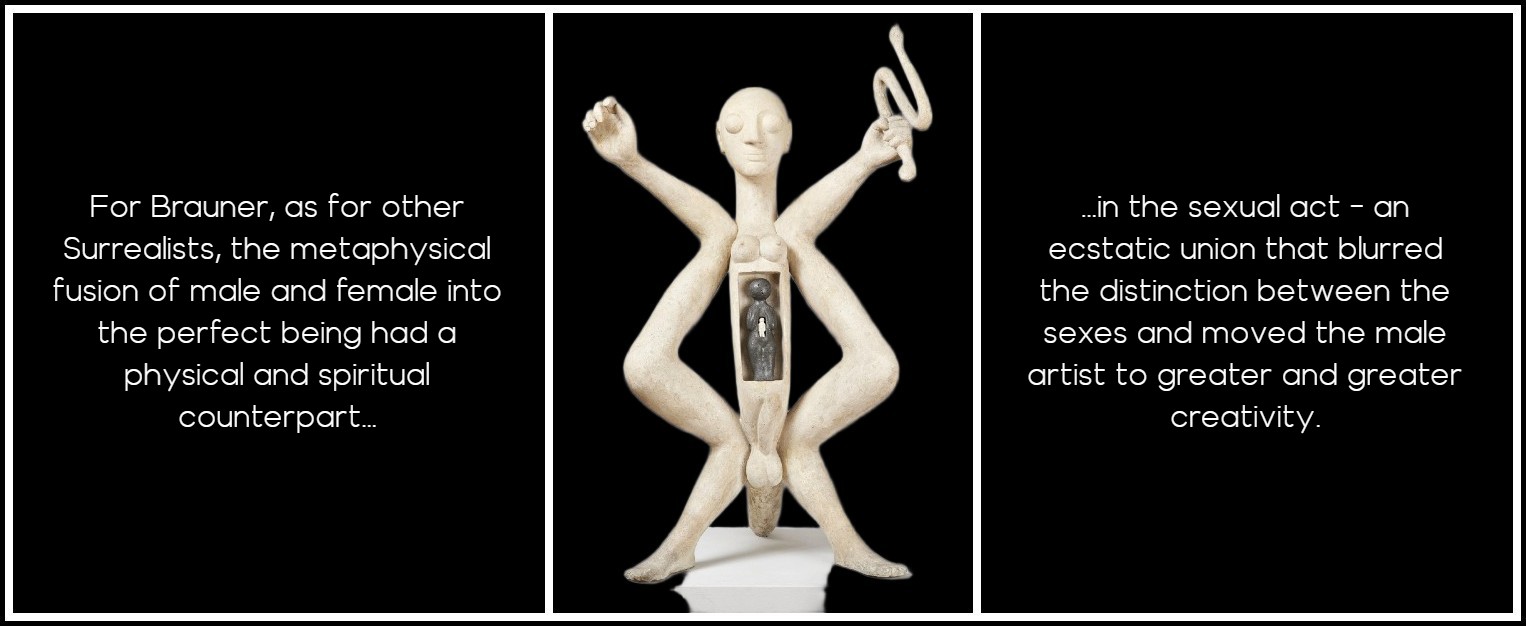

In Arcane 17 Breton clarified the need to resolve the inherent conflict between male and female principles. In the end it is the artist who will effect the synthesis, for he alone (Breton clearly refers here to the male artist) has access to both realms of being: ‘It is the artist who must rely exclusively on the woman’s powers to exalt, or better still, to jealously appropriate to himself everything that distinguishes woman from man.’ Breton, like Masson and other Surrealists, was influenced by the nineteenth-century German writer J.J. Bachofen, who had traced the development of ancient Greece through a matriarchal period characterized by the primacy of the blood relationship, the equality of all men, and a fundamental respect for human life and the power of love. The presence of a powerful female principle in the work of male Surrealists finds its final resolution in images of the couple or the androgyne. As a glorification of spiritual fecundity, the myth of the androgyne becomes a celebration of spiritual procreation. Viktor Brauner’s Number (1934) presents a gravid androgynous figure. Here male and female sexual organs are attached to the ends of a box-like womb, in which a tiny sculpted figure resides. For Brauner, as for other Surrealists, the metaphysical fusion of male and female into the perfect being had a physical and spiritual counterpart in the sexual act—an ecstatic union that blurred the distinction between the sexes and moved the male artist to greater and greater creativity.

Viktor Brauner, Number, 1943

Unlike the male Surrealist, who absorbed the image of woman into his own image through the metaphor of the androgyne or couple, women artists have often chosen to emphasize the fundamental biological and spiritual forces that distinguish woman’s experience from that of man, and that place her in direct contact with the magic powers of nature. Writing in the 1940s, Ithell Colquhoun related: It is harmful to attempt normal tasks—business, housework, the catching of trains—when, periodically, normality is absent and its place taken by intensified sensibility to hidden springs. At such times, a woman must become reconciled to the moon. She shall then seek to divine buried treasure, to speak oracular words, to consummate the ritual marriage. This is a natural break in outward routine, and to neglect it brings the loss of beauty and peace.

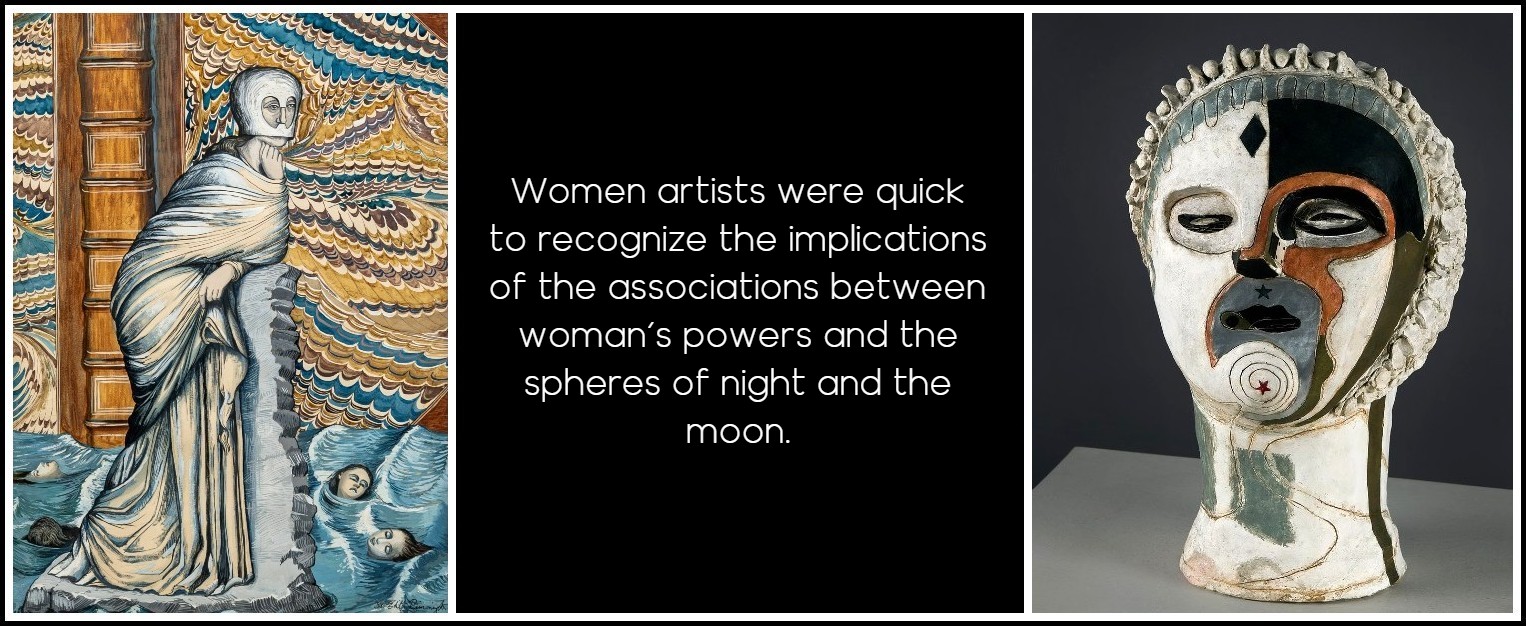

Ithell Colquhoun, Alcove, 1946

In directing attention toward the internal, the hidden, and the mysterious, to all that was inaccessible to the illumination of the sun and to rational control, Surrealism followed a path that led inexorably toward the domain of Faust’s Mothers.1 Women artists were quick to recognize the implications of the varied and legendary associations between woman’s powers and the spheres of night and the moon. The encrusted surface and mute echoing forms of Eileen Agar’s Mask of Night (1945) invoke the mysteries of night while in Rimmington’s pen and watercolor drawing of 1938, Washed in Lethe, the classically draped image of a woman presides over the sleeping figures of young women who float through the underworld waters of oblivion.

1 – See the Mothers scene in Goethe’s Faust, where ‘it is woman as mother, not as beloved, who attracts the protagonist and from whose fertility his own creativity springs’. Quotation from Heinrich Henel, review of Harold Jantz, The Mothers in ‘Faust’: The Myth of Time and Creativity (John Hopkins Press, 1969) Modern Philology, Vol. 69, No. 2 Nov. 1971, pp. 175-178.

Edith Rimmington, Washed in Lethe, 1938 | Eileen Agar, Angel of Mercy, 1934

Among the earliest paintings produced by women artists associated with Surrealism are a number that refer directly or indirectly to woman’s possession of these secret powers. In the two years before she joined the London Surrealist group in 1936, Eileen Agar had executed several paintings containing classical allusions to the ancient muse of poetry. The Modern Muse and The Muse Listening, both painted in 1934, treat this theme using the traditional iconography of female personification. In addition, the object called The Muse Listening juxtaposes the forms of the sacred harp or lyre and the heart, objects instrumental in the release of creative passions. But the 1936 collage My Muse, executed under the growing influence of Surrealism, suggests that the muse has ceased to exist as an external principle and has now been internalized, absorbed into the practice of automatism that allows the artist direct and unmediated access to the imagery of the unconscious. No longer an external metaphor, the muse has become part of an active internal creative principle, and although the idea of an art responsive to internal realities was shared by all Surrealist artists, male and female, it came to have specific meanings and associations for women artists.

EILEEN AGAR

The Muse Listening, 1934 | My Muse, 1936 | The Modern Muse, 1934

Agar’s Mysterious Vessel (1935) places its mythic references to the horses that draw the chariot of the sun and the entwined serpents of the underworld on the surface of a large urn that is set against the resonant ground of a Grecian blue sky. A few years later, discussing a painting titled the Muse of Construction (1939), she articulated the connection between the concept of the muse and an inner, private, and mysterious realm of being that is evoked through the image of the urn or vessel with which woman’s body has so often been identified: When I called the painting the Muse of Construction I wanted to emphasize the fact that although the word ‘construction’ is usually associated with buildings, architecture and things mechanical, I wished to associate it with the human form which is a marvellous construction, built and assembled over millions of years, adaptable and flexible. Although its skeleton is worn inside and the soft-ware outside, it goes through many changes and holds a lot of secrets in its trunk. At one time I thought of calling the painting the ‘Urn Goddess’ as I have always been interested in the shape of a vessel, but somehow the Muse of Construction seemed more mysterious and poetic.

EILEEN AGAR

Urn Burial, 1989 | The Muse of Construction, 1939

Myth, magic, and the occult joined together in shaping the Surrealist image of woman as the repository of hermetic knowledge. Breton’s vision was influenced by the importance attributed to woman by Simon the Magus, the New Testament sorcerer who bewitched the people of Samaria, and Eliphas Levi, a French nineteenth-century occultist, who had defined for her the role of an intermediary and who saw her as endowed with the power to intervene in tragic circumstances and to transform anguish into ecstasy. Both saw the need for a balancing of opposites and influenced Breton’s notion of a union of man with woman and her powers that would bring man into closer contact with the elemental transforming agents of the universe. For Breton, love was the means by which man moved into the circle of woman’s magic powers. Michelet’s La Sorcière had provided him with one guide; occult studies, particularly alchemy, which had fascinated modern poets from Baudelaire to Rimbaud and Apollinaire, offered another: an alternative to rational control, a means of reinvesting poetic language with a sense of mystery and coded meaning, and a vision of a poetic landscape brought into being through the transmutation of material and spirit. The Surrealist poet became an alchemist of language, the painter worked a metamorphosis of form and color, and the resulting work possessed the power to transform consciousness, life, and the world.

Joseph Wright of Derby, The Alchemist, 1771 | Leonora Carrington, The Chrysopeia of Mary the Jewess, 1964 | Francois-Marius Granet, The Alchemist, 1805

In Dorothea Tanning’s novel Abyss, written in 1946 during the first year of her stay in Arizona with Max Ernst, the main character is a painter named Albert Exodus who is described as ‘hiding behind his colors like an alchemist behind his fiery liquids, his sulphurs, his loathsome fumes.’ A linking of alchemy and the erotic offered the male Surrealist the surest means to the reconciliation of opposites and the unveiling of the ‘marvelous’; for the woman artist myth, alchemy, and the occult became a means of repossessing creative powers long submerged by Western civilization. ‘Reading The White Goddess was the greatest revelation of my life,’ recalls Carrington, who read Robert Graves’s monumental mythic study of the God of the Waxing Year’s losing battle with the God of the Waning Year for love of the capricious and all-powerful Threefold Goddess who reigned over poetic creation, shortly after its publication in 1948, but who had for many years drawn her imagery from the same sources. ‘The reason,’ wrote Graves, ‘why the hairs stand on end, the skin crawls and a shiver runs down the spine when one writes a true poem is that a true poem is necessarily an invocation of the White Goddess, or Muse, the Mother of All Living, the ancient power of fright and lust—the female spider or the queen bee whose embrace is death.’

Peter Paul Rubens, The Birth of the Milky Way, 1637 | Spider photo: Getty Images for Unsplash

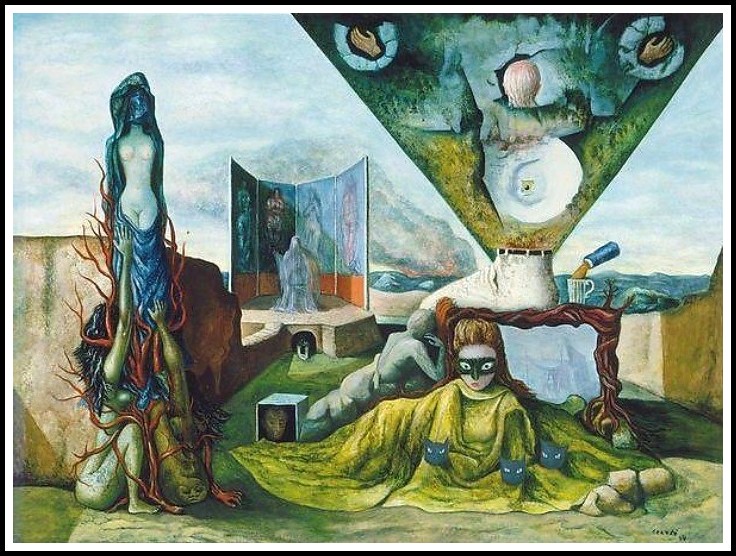

Whether conceptualized as the Celtic White Goddess who governed poetic inspiration and who presided over the tribe of the Tuatha de Danaan, the fertility and moon goddess Isis, the goddess of magic in Old Kingdom Egypt, or the female substance necessary for the commencement of the alchemical Work, the existence of an ancient female principle governing creation/fertility and death pervades much mythic and hermetic literature. Between 1939 and 1950, Fini, Carrington, Varo, and others executed numerous paintings that locate the origins of woman’s creative consciousness in this ancient tradition. Their quest was not a conscious search for the archetypal Great Goddess whose reclaimed existence has formed the core of much recent Feminist writing, for she was then a shadowy presence at best. But because they believed in fairy tales, legends, and the magical properties of artistic creation, and because they followed the threads of that creation deep into their dreams and unconsciouses, and derived specific and potent images from stories that, whether theosophical, legendary, or alchemical, confirmed these inner searches, they forged the first links in the chain that has more recently been used to reconnect contemporary Feminist consciousness with its historical and legendary sources. Alice Rahon wrote in 1951: In earliest times painting was magical. It was a key to the invisible. In those days the value of a work lay in its power of conjuration, a power that talent alone could not achieve. Like the shaman, the sybil and the wizard, the painter had to make himself humble, so that he could share in the manifestation of spirits and forms.

ALICE RAHON

Judas and the Chimera, 1952 | La Conjurations des Antilopes, 1943 | ¡Torito, Toro! 1951

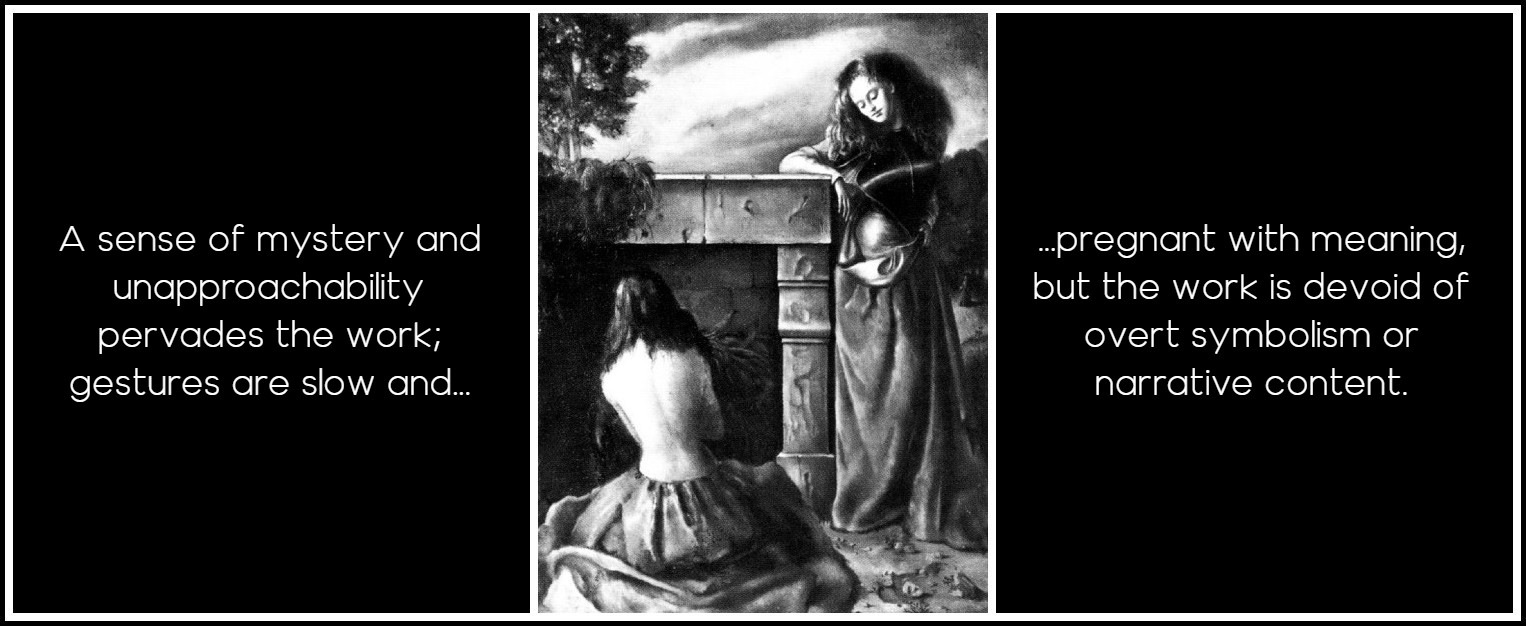

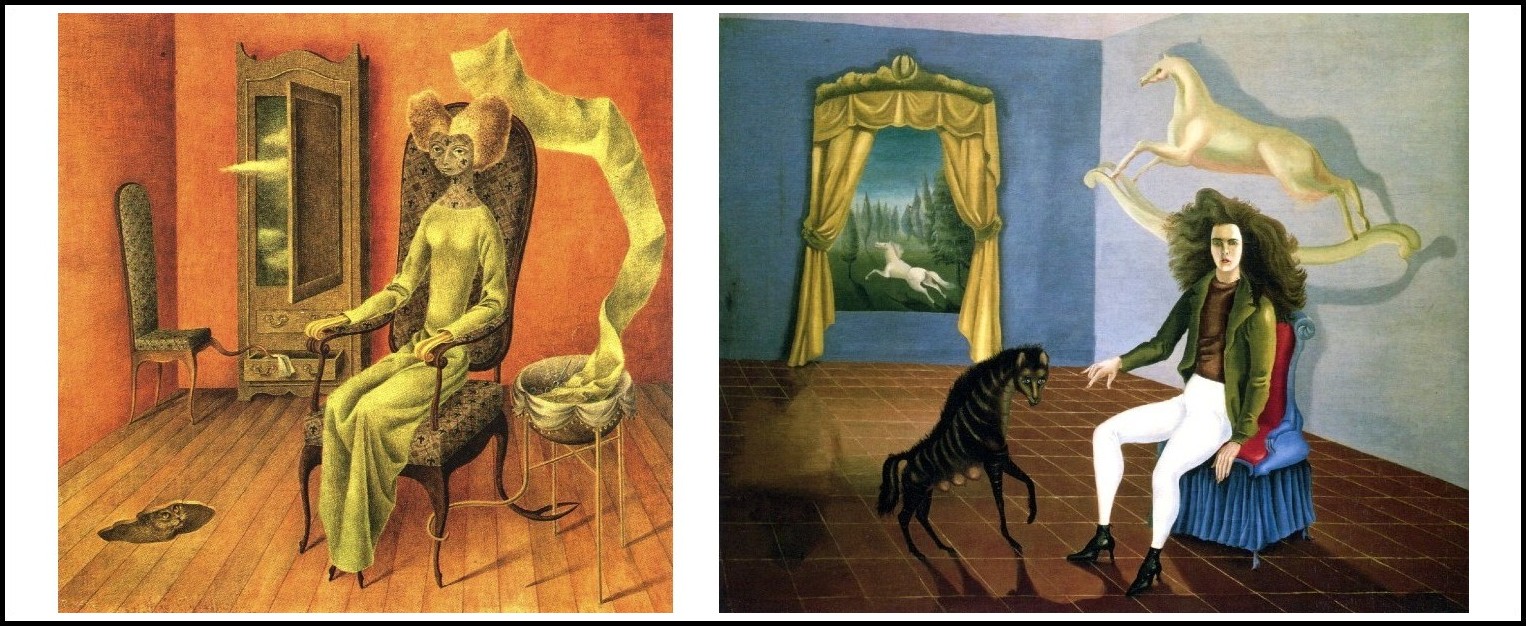

Leonor Fini’s Ceremony (1939) is one of the first of a group of paintings that recall this world in which ceremonies and rituals marked the cyclical passage of time, and in which life, death, the seasons, gods, and ancestors were observed with appropriate respect for the hidden powers that their presence called forth. The spectator arrives at Fini’s Ceremony as if coming into the middle of an event which, despite the clarity of its outward presentation, remains shrouded as to inner meaning. The main protagonist is woman, her image at the center of a mysterious ritual enacted before a stone altar and under the sign of nature, present in the leafy branches laid over the altar. The figures, one kneeling, one standing, one viewed from the back and naked to the waist, the other seen from the front and protected by a curved breastplate, reinforce the tension between interior and exterior, the protected and the vulnerable, the visible and the veiled. Colors are somber and details minutely rendered; Fini’s meticulous draftsmanship serves to heighten the sense of mystery and unapproachability that pervades the work. Gestures are slow and pregnant with meaning, but the work is devoid of overt symbolism or narrative content; ‘painting is immobile and silent and I love it thus,’ the artist has said.

Leonor Fini, Ceremony (Ritual), 1939

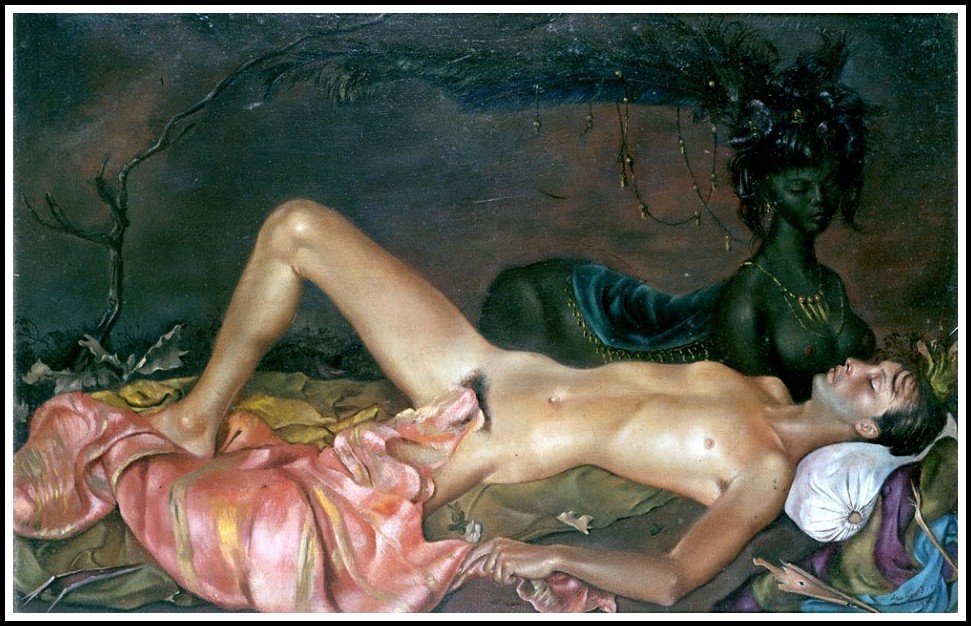

In other paintings, Fini situates her female figures at the juncture between a theatrically conceived external world in which the painting is a kind of staged set, and an inner world of stygian darkness and primordial chaos, and between a state of consciousness dominated by social interaction and one ruled by instinctual drive and animal need. Once again, it is Graves’ world of the White Goddess, and that of Michelet’s La Sorcière, which Fini had also read, that is being evoked. In Chthonian Divinity Watching Over the Sleep of a Young Man, a figure of darkness, night, water, and earth presides over the living. The passive androgynous male figure sleeps under the watchful eyes of a female sphinx who conveys the power of the earth and nature, of life and death. The sleeping figure is almost a parody of Mannerist reclining nudes, but the acid colors and ominous nocturnal glow shroud the figure with an air of menace.

Leonor Fini, Chthonian Deity Watching over the Sleep of a Young Man, 1946

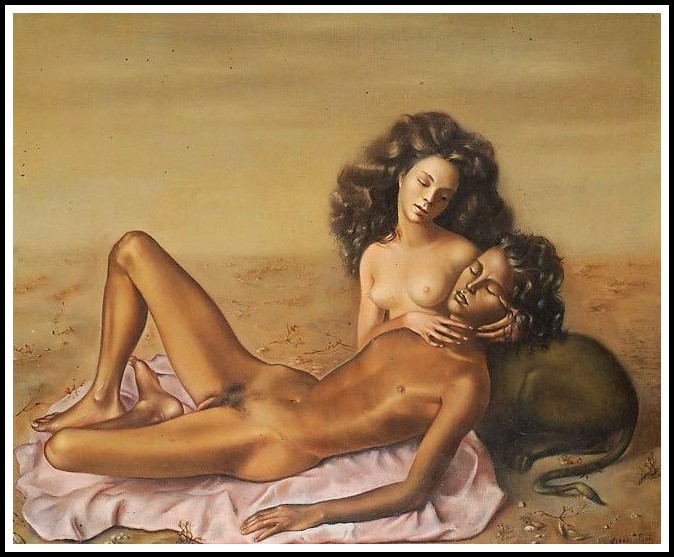

The hybrid sphinx mediates between the human and the bestial in Fini’s work. The image, which first appears around 1942, had deep personal significance for the painter, serving as a symbolic reunification of a human and civilized world that she views as lacking passion and animality, and an animal world in which the magical powers of animals may help humans to understand their own loss of connection to a more primordial nature. Her beasts have only a tangential parentage in antiquity, and replace the hermetic features of the Egyptian and Renaissance sphinx with the unkempt and pouting look of contemporary female figures. For Fini, woman is sorceress and priestess, beautiful and sovereign; by assuming the form of the sphinx she exercises all the powers that have been lost to contemporary woman. Fini’s refusal to depict woman as submissive or subordinate to man has often led critics to view her works as polemical or separatist statements, or to assert their lesbian content. Both readings have been emphatically refuted by the artist who, despite her dislike for orthodox Surrealism, has always adhered to the underlying Surrealist principle of the unification of opposites and the reclaiming of lost powers. She rejects the idea of social matriarchy as ‘a little grotesque,’ embraces an ambivalent sexuality rather than the Surrealist myth of the androgyne, and has argued that because she is a woman and finds woman’s physical form more beautiful than that of man, she has placed the responsibility for ‘Being’ in the hands of woman. Sympathetic to Jung, she has accepted his notion of the anima, the soul as feminine. To man belongs the animus and it is this which controls the constructed and social world, which slumbers in her paintings under the watchful eyes of a female being who embodies the intuitive world and who is willing to wait for man’s reawakened consciousness. She explains: The man in my painting sleeps because he refuses the animus role of the social and constructed and has rejected the responsibility of working in society toward those ends.

Leonor Fini, The Sphinx Amalburga, 1942

Fini’s sphinxes belong to the animal and the civilized worlds. Often situated in a nocturnal nature in the process of decomposition and regeneration, as in Sphinx Philagria and Sphinx Regina, they exist in a world described by Fini’s friend Jean Genet as one of ‘cruel kindness’ and ‘swampy odors.’ Nature dominates these visions, but it is a nature both destructive and regenerative.

LEONOR FINI

Sphinx Philagria I, 1945 | Sphinx Regina, 1946

Fini’s Petit sphinx ermite (1948), however, recalls the figure of the sphinx as sorceress and image of death. Here representations of necromancy and death surround the hybrid creature: a triangle, broken eggs, and a hermetic text.

Leonor Fini (Photo: Arturo Ghergo, Rome 1945) | Leonor Fini, Petit sphinx ermite, 1948

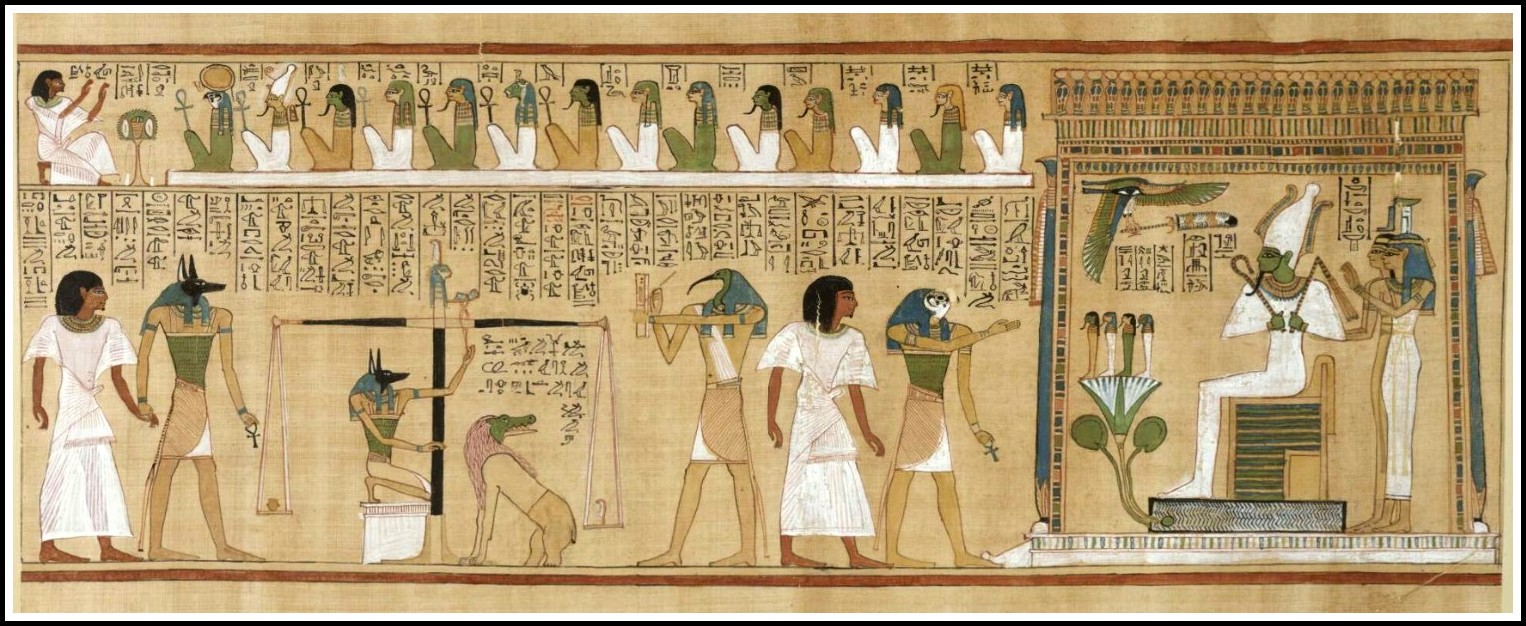

The true subject of the alchemical Great Work was the reconciliation of opposites through a process aimed at material and spiritual purification in the creation of divine harmony on earth and in heaven. ‘As above, so below’ read the inscription on the emerald tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, the semi-mythical founder of alchemy; on the material level, the process involved an analogous refining of base metals into gold. In the process of transmuting metals, the catalyst was the Philosopher’s Stone, which contained the secret not only of transmutation but also of health and life, for through its agency could be distilled the Elixir of Life. The first substances were mixed in an egg-shaped vessel in the presence of the Philosopher’s Stone and slowly warmed over a fire to produce a liquor called ‘chaos,’ containing the elementary qualities of cold, dryness, heat, and humidity. The liquor was then allowed to putrefy to a black material called the ‘crow’s head,’ or ‘raven,’ after which it was once more boiled in a white vase to obtain a white liquor called the ‘swan,’ which could then be broken down into white and red (gold). Alchemy became one aspect of a body of hermetic literature drawn from Neo-Platonism, Philonic Judaism, and Kabbalistic theosophy through which secret knowledge had been communicated for centuries. Often its secrets were hidden in vivid symbolic images that pointed the initiate toward the final goal of reconciliation and transformation.

Book of the Dead of Hunefer, Frame 3; Egypt, 19th Dynasty | The British Museum

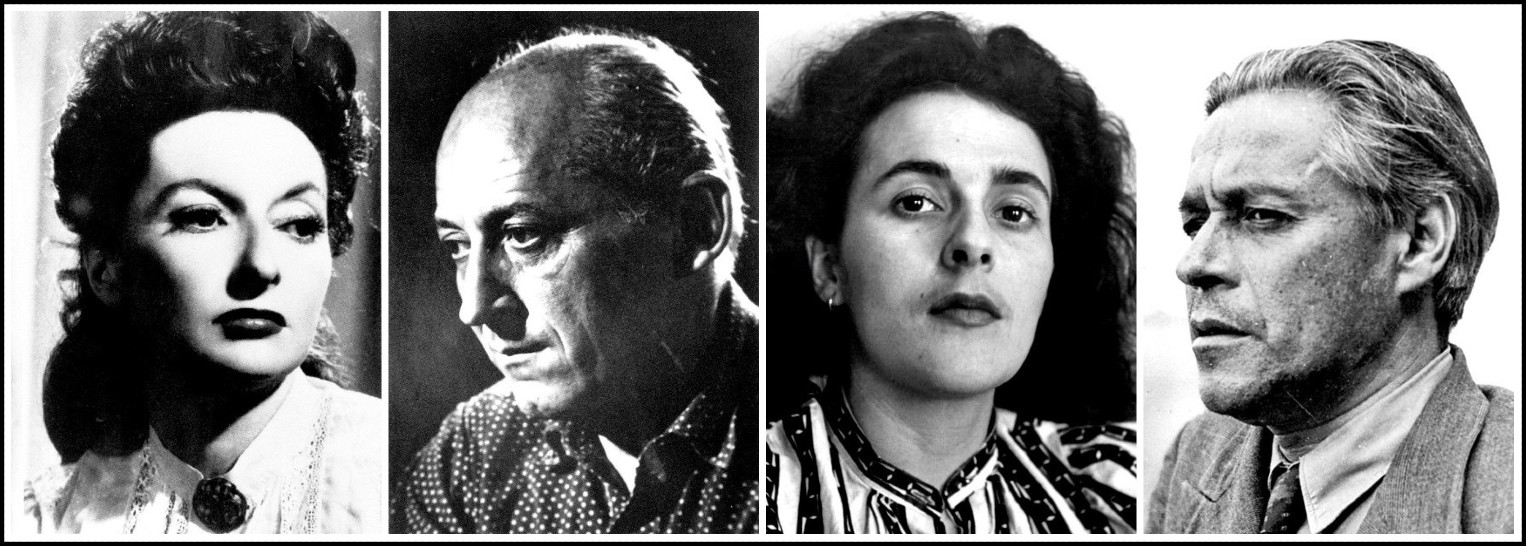

The most intense and far-reaching attempt to develop a new language through which the woman artist’s ‘other’ reality might be communicated occurred in Mexico during the 1940s and 1950s. In November 1941, after a long and difficult journey, Remedios Varo and her partner, the poet Benjamin Péret, arrived in Mexico. Prevented from traveling to New York with other Surrealist émigrés because of Péret’s leftist political affiliations and support for the Loyalist cause in Spain, the penniless couple had waited months in Casablanca because they didn’t have the right papers. Varo, remembering from childhood trips to North Africa with her father that Muslim dead must be wrapped in white for their final meeting with God, had raised small sums of money for the voyage by selling the few white bed sheets she had been able to pack. Finally, influential friends, working through Varian Fry’s French Relief Committee in Marseille, managed to secure steamer passage for the couple. They arrived in Mexico with no money other than the small allowance paid to Spanish political exiles by the Mexican government, and settled in a decaying apartment building on Gabino Barreda, not far from the ancient Aztec center of Mexico City and near the more recent Monument to the Revolution. Varo immediately began the wearying task of providing an income for the couple, an undertaking dictated by necessity, but one that would drain much time and energy from her own painting for the next ten years. Some months later, Leonora Carrington’s long odyssey also ended in the land that Breton had called the ‘Surrealist place par excellence’; she and Renato LeDuc moved into an apartment on Rosa Moreno, just a few blocks from Varo and Péret.

Remedios Varo | Benjamin Péret | Leonora Carrington | Renato Leduc

The huge apartment on Rosa Moreno was in a building that had once served as the Russian Embassy but had since been abandoned. Now the marble floors and curving staircases lay in a state of near ruin, and a tangle of tropical vegetation threatened the exterior. To Carrington, Mexico seemed extraordinary, an exotic locale pulsing with bright colors and life, filled with the evidence of past civilizations untouched by Western classical tradition. Many of LeDuc’s friends were bullfighters; the apartment was often filled with people. Even after the amicable end of the ‘marriage of convenience’ that had allowed Carrington to leave Europe in 1941, the couple remained close friends. Carrington and Varo soon became the center of a group of artists that included Gunther Gerzso and Enrique ‘Chiqui’ Weisz, who would become Carrington’s second husband, and the photographers Kati Horna and Eva Sulzer. Luis Buñuel was there periodically, as were former Surrealists now settled in Mexico like Wolfgang Paalen, Alice Rahon, and a few years later, Gordon Onslow-Ford. Paalen, who had arrived in 1939, had organized the 1940 International Exhibition of Surrealism with the Peruvian poet Cesar Moro and had founded the short-lived but influential art magazine Dyn.

Gerardo Lizarraga, Chiki Weisz, Jose Horna, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo,

Gunther Gerszo, Benjamin Péret, Miriam Wolf | Photo: Kati Horna, 1946

This new periodical published the work of many Surrealists living in Mexico, although the group around Péret, Carrington, and Varo kept their distance from the new publication and there was little contact between Paalen and Péret. Gerzso’s 1944 painting Los Días de la Calle de Gabino Barreda pays homage to the little band of exiled Surrealists with portraits of Carrington caught in the tendrils of a rapacious vine, Varo surrounded by cats, Péret, Esteban Frances, and on the reverse, a self-portrait of the artist. Varo and Carrington saw little of Kahlo and Rivera, however. Carrington recalls that the Mexican artist was already in deteriorating health, while Péret’s belief that Rivera had sanctioned an early attempt on Trotsky’s life by a group that included the Mexican painter David Siqueiros inhibited contacts.

Gunther Gerzso, Los Días de la Calle Gabino Barreda, 1944

The existence of an active group of exiled painters and writers in Mexico during the 1940s set the stage for the creative activity that flourished there during the next decade. More significant for the history of the women artists we have been discussing were the artistic results of the close emotional and spiritual relationship that developed between Carrington and Varo at this time and that propelled their work into a maturity distinguished by powerful and unique sensibilities newly independent of earlier influences of other Surrealist painters. The two, once friends in France, now became fellow travelers on a long and intense journey that led them to explore the deepest resources of their creative lives. For the first time in the history of the collective movement called Surrealism, two women would collaborate in attempting to develop a new pictorial language that spoke more directly to their own needs. ‘Remedios’s presence in Mexico changed my life,’ Carrington recalled, adding that she saw Varo and Péret almost every day.

Leonora Carrington & Remedios Varo

During their first few years in Mexico neither woman produced many paintings. Carrington seems to have found writing a better exploratory medium for her new imagery, and her serious production of paintings did not begin again until 1945. Varo’s works were first exhibited in 1954 and their dates of execution remain questionable. The meticulousness of her working methods indicates that at least some of the many paintings exhibited in 1954 may have been produced before that date. During the 1940s Varo worked at a variety of jobs, none of which paid particularly well, and all of which inhibited her own painting. She assisted in the building of small pro-British anti-Fascist dioramas documenting Second World War battles and designed to show the Mexican people that the Allies were winning the war; worked for Paalen secretly restoring pre-Columbian pottery for sale; designed costumes for Chagall’s 1942 production of Alekko, which had been moved to Mexico because of the war raging in Europe; and worked as a commercial artist designing advertisements for Bayer aspirin and painting furniture and screens for Clar Decor, an interior design showroom.

Remedios Varo & Leonora Carrington, 1950s [The man is a ‘Mr. Shepherd’.]

There is no indication that either woman looked forward to professional careers or public acceptance of their art. ‘I painted for myself,’ Carrington later said; ‘I never believed that anyone would exhibit or buy my work.’ But work they did. Carrington wrote plays and short stories, executed dozens of watercolors, many of them covered with the mirror writing that had led to her expulsion from school many years earlier, and began experimenting with egg tempera on gesso panels. Varo filled notebooks with accounts of dreams and with short stories, invented games, and magic formulas. Together the two women built and furnished a small model living room, perhaps as a moquette for a design project but perhaps just for pleasure, filling it with painted cardboard and papier mâché furniture, and they appear to have co-authored at least one Surrealist play during this period.

Leonora Carrington (Photo: Kati Horna) | Remedios Varo (Photo: Walter Gruen)

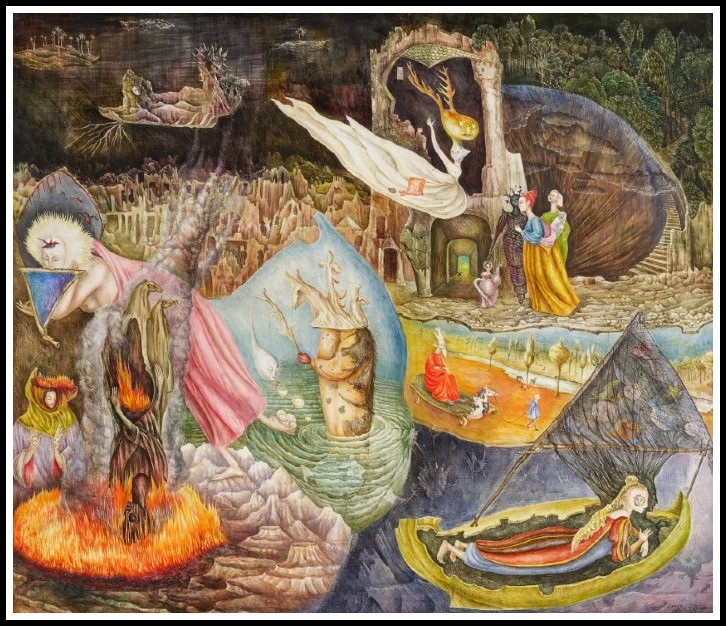

The friendship between the two women extended to the sharing of dreams, stories, and magic potions. What would later become some of Varo’s most persistent images—among them fantastic locomotor conveyances, particularly boats powered by the wind and sun, complex alchemical apparatuses, towers with conical roofs and deep interior spaces reminiscent of Chirico, and landscapes based on the technique of decalcomania—can be found in Carrington’s transitional works of the mid 1940s, in paintings like Les Distractions de Dagobert…

Leonora Carrington, Les Distractions de Dagobert, 1945

…and Tuesday, but disappear from the later works.

Leonora Carrington, Tuesday, 1946

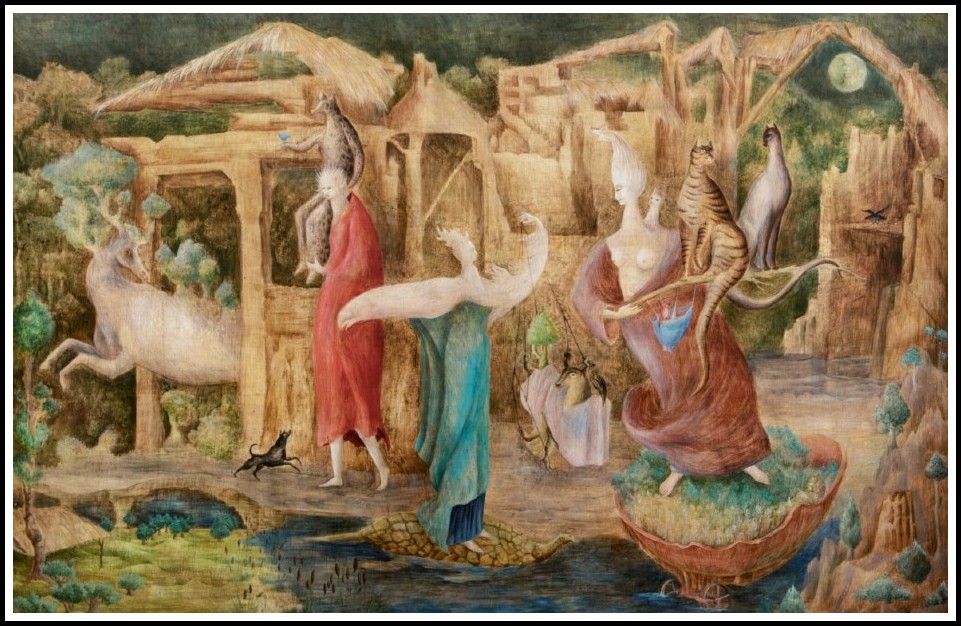

Varo’s stories of the period often include aristocratic English characters, and at least one dream jotted into her notebooks contains a reference to Leonora. In addition, Varo’s paintings of the 1950s sometimes include motifs from Carrington’s work. In Mimesis, for example, the human figure’s hands and feet mimic their furniture equivalents, while a chair in a corner kicks a cupboard. The work as a whole reworks the strange encounters and formal parodies of Carrington’s Self-Portrait. Nevertheless, the works executed by Carrington and Varo after 1946 are unmistakably the products of different sensibilities, even though they share a vision of painting as a recording of life’s many voyages: physical, metaphysical, and spiritual. In the works of both, reality is constantly being transformed and symbolic journeys undertaken. The women in Varo’s paintings, many of them depicted with the heart-shaped face and delicate features of her own image, are alchemists, magicians, scientists, and engineers who travel through forests, along rivers, and above the clouds in jerry-built conveyances that run on stardust, music, and sunlight. Carrington’s female protagonists are like the sibyls, sorceresses and priestesses of some ancient religion; their journeys are mythic voyages into magical worlds that unravel like fairy tales. It is as secret journeys to enlightenment, proceeding despite obstacles and despair, or bursting with creative life, that the works produced in Mexico by Carrington and Varo must be considered.

Remedios Varo, Mimesis, 1960 | Leonora Carrington, Self-Portrait, 1938

Gloria Orenstein, following a feminist model that has attempted to revise traditional definitions of madness and sanity as they relate to woman’s experience, has argued that the ‘breakdown’ Carrington underwent in 1940 might be more accurately viewed as a ‘breakthrough’ to new levels of psychic awareness. The paintings and writings produced in Mexico during the mid-1940s reveal the search for a pictorial language adequate to the task of communicating this psychic evolutionary process. In them, interior and exterior, upper and lower spaces are organized in relationships that suggest physical passages, the presence of the world of the dead (spirit) parallels that of the living (matter), and mythic and hermetic signs and symbols are used to trace the passage of the spirit. Among Carrington’s early paintings from the Mexico period are many, including Neighborly Advice…

Leonora Carrington, Neighbourly Advice, 1947

…and The Old Maids that use the image of the house and the domestic activities that take place within its walls as metaphors for woman’s consciousness.

Leonora Carrington, The Old Maids, 1947

CONTINUED IN PART 2 (SEE ‘RELATED POSTS’ BELOW)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2026 | All rights reserved

Comments