MADNESS: SCHIZOPHRENIA & SCHIZOID STATES

GISELA PANKOW & THE PSYCHOTHERAPY OF PSYCHOSES

PREFACE TO CASE STUDY: ‘JACQUES AND THE GYPSY’

From Florent Poupart, ‘Hommage à Gisela Pankow’ (Psychothérapies 2014/1 Vol. 34) pp. 51-58. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Gisela Pankow (1914-1998) is one of the great figures in the psychotherapy of the psychoses. Even if the evocation of her clinical practice is sometimes reduced to her use of clay modelling with her patients, should we be annoyed by this caricature? Perhaps not, because Gisela Pankow’s use of modelling is a condensation of the essence and vivacity of her approach: the appeal to the body (manipulation of clay, three-dimensionality of the modelled object) in the service of bringing about a true encounter with the most inaccessible patients. Through recourse to modelling, Pankow strives to find the means to gain access to the patient’s lived psychotic experience: she invites us to nothing less, in order to meet the patient in his world, than to accompany him in his ‘descent into hell’.

Gisela Pankow

Once, when I used this expression (‘descent into hell’) at a conference, I was taken to task by the psychiatrists present, who were offended by the violence of the metaphor. Indeed, the institution that deals with madness is sometimes tempted, on the pretext of upholding science and humanism, to deny that psychosis is eminently enigmatic and disturbing; it is tempted to reduce psychiatry to neurology, to consider mental illness the result of errors in judgement that can be corrected. Psycho-education, the emblem of this re-educative approach to psychosis, consists in imposing on the patient a framework that is not his own, one that spurns his lived experience, his particular relation to himself and the world. In short, the re-educative approach forgets that what is at stake in psychotherapy with psychotics is always the encounter, as Pankow tirelessly reminded us: The task is to help the patient recover what psychosis has denied him, namely ‘access to the other, to someone who is not oneself and who can be desired’.

GISELA PANKOW

L’être-là du schizophrène

GISELA PANKOW

L’homme et sa psychose

GISELA PANKOW

Structure familiale et psychose

INTRODUCTION TO CASE STUDY: ‘JACQUES AND THE GYPSY’

From Psychosis: Phenomenological and Psychoanalytical Approaches, ed. Jozef Corveleyn & Paul Moyaert (Leuven University Press, 2003) pp. 27-29

The schizophrenic, finding himself in an unlivable situation, escapes from his own body. Should he attempt to return to it, he fails: the body remains behind, uninhabited and abandoned, like a form without content, an empty shell. This radical turn away from the libidinal body inevitably leads to a loss of identity, since along with loss of the lived body, there is also a loss of bodily experienced memory, a loss of the libidinal history in which the ego sinks its roots. The subject becomes entrapped and enclosed in a timeless, inhuman space.

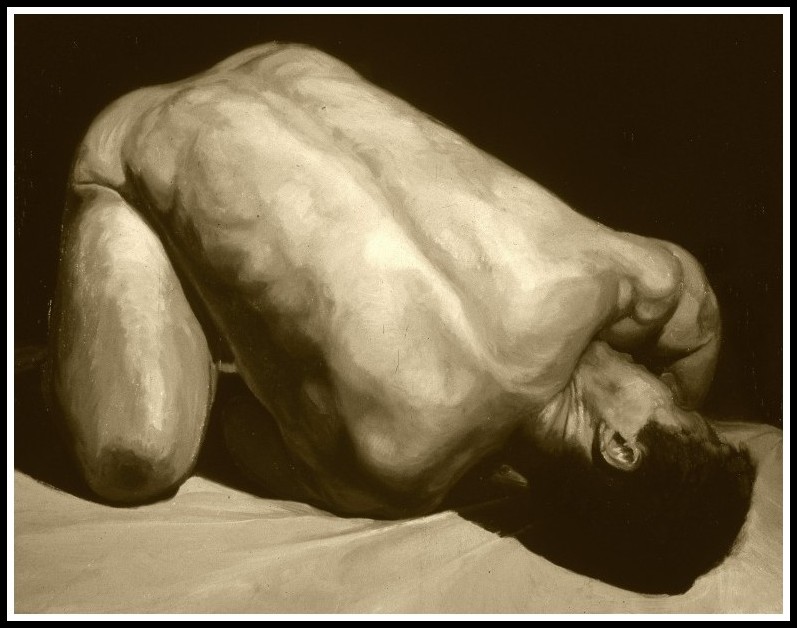

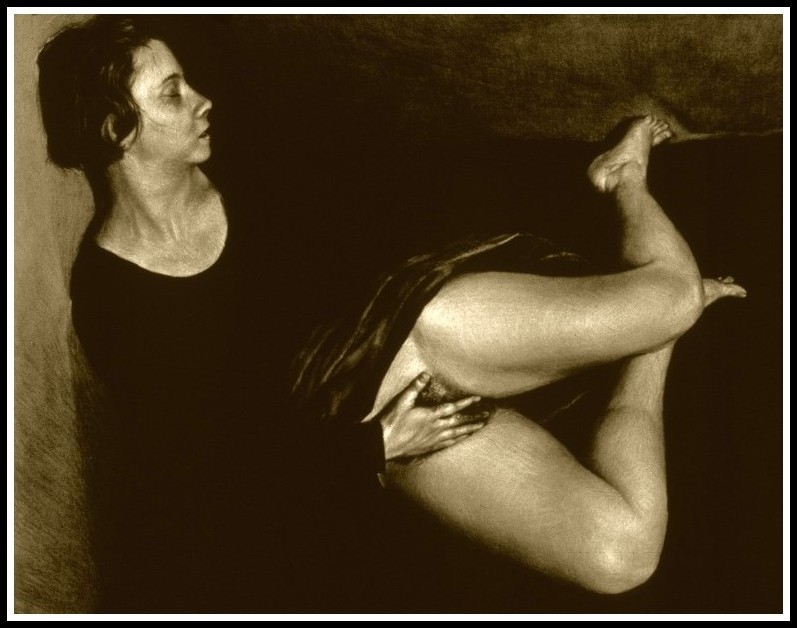

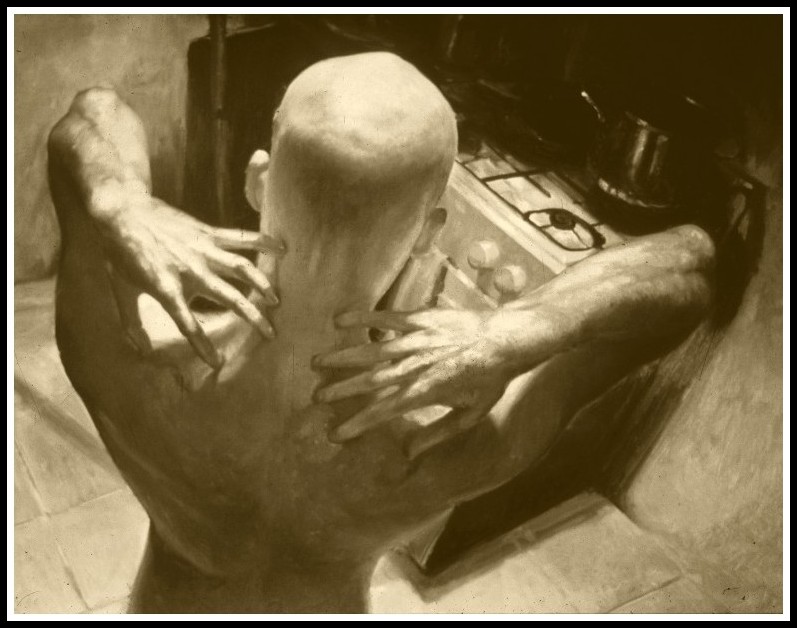

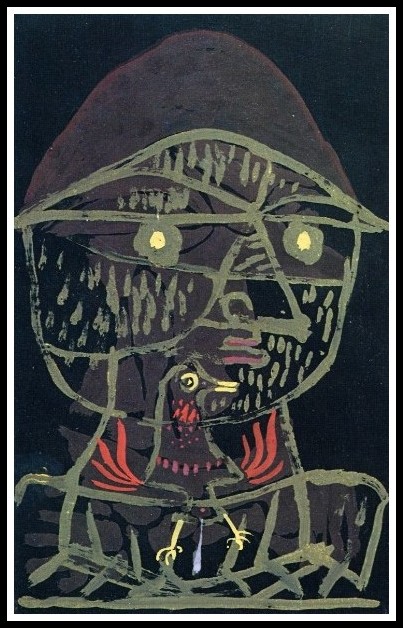

Image: Paul Beel

Given this archaic level of psychic functioning, the therapist is faced with the difficult task of bringing about an encounter with the patient. Gisela Pankow’s originality lies precisely in the way in which, in her practice, she gains access to the life-world of her schizophrenic patients. She defines the body image on the basis of two symbolic functions inherent in the symbolic structures that are contained and controlled by one’s earliest bodily experiences. The first function of the body image makes it possible to recognize a dynamic link between the various parts of the body and the whole. This function is only concerned with the spatial aspect of form: it is a matter of the structuring of the body as a spatial totality in which the parts dynamically refer to one another. She calls this aspect the ‘felt body’. The second function of the body image concerns the body as the bearer of primarily interpersonal meanings. This function organizes the body image in the subject’s meaningful interaction with the world on the basis of the culture’s symbolic laws transmitted from one generation to the next. This she calls the ‘recognized body’. With this second function, Pankow has in mind the psyche’s intentional directedness to what is other (the object). This directedness is linked with the temporal dimension and, hence, with the construction of one’s own libidinal history.

Image: Paul Beel

Pankow shows that in schizophrenic psychosis, the symbolic structures of the body image are radically destroyed, whereas in the various forms of psychosis in which hallucinations and delusions are prominent and in neurosis, they are only partially affected (only the relational functions are impacted). Disturbances of the first function of the body image are typical of schizophrenia. Pankow refers to this as ‘dissociation’, a destruction of the body image in which the parts lose their link with the whole and subsequently reappear in the external world in the guise of voices or visual hallucinations. These fragments of the body are no longer recognized by the subject as its own. For this reason, the distinction and the link between the inner world and the outer world loses its clarity. Body parts can sometimes still be experienced in a limited way, but they no longer refer to the whole body: they form a totality unto themselves. In order to gain access to the patient’s spatial world, Pankow asks him or her to make a clay model. These models are then considered as representations of the lived body, and they form the main point of reference for her technique.

Image: Paul Beel

Family Structure and Schizophrenia

CASE STUDY: JACQUES AND THE GYPSY

First Encounters with a Chronic Schizophrenic

Gisela Pankow

From Gisela Pankow, Structure familiale et psychose (Paris: Éditions Flammarion, 2004 | Éditions Aubier Montaigne, 1977) pp. 86-96. (The case itself dates from the late 1950s.) Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

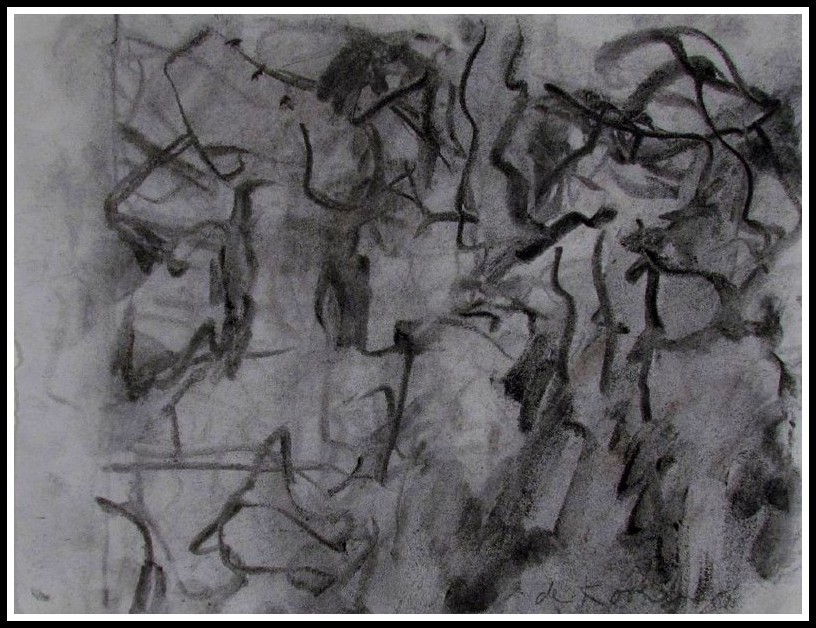

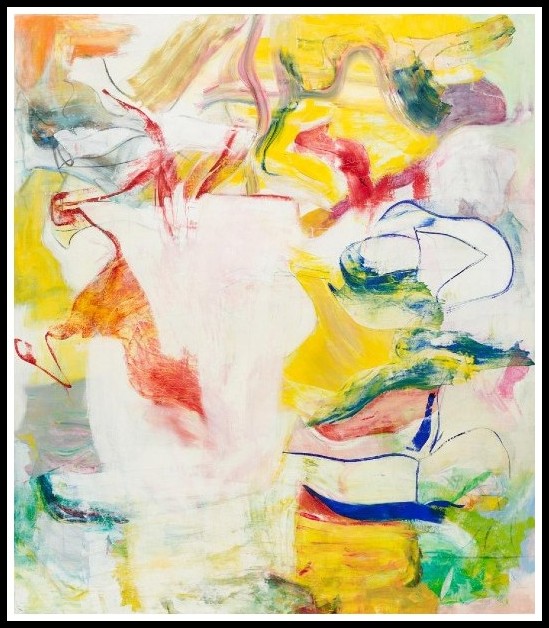

Willem de Kooning, Untitled, c. 1978-80

Where can a son land up if, for his mother, he is but ‘the bad of both parents’? Jacques, aged thirty-seven, a professor of philosophy, had been hospitalized four times. In parallel, a psychotherapist had tried a therapeutic approach with him. Jacques told me that he ‘had lived every possible experience of psychotherapy on this planet’. Tracing circles around his head, he continued: ‘Inscribed in these trajectories is all possible knowledge and revelation in psychotherapy’. He was in a state of anxious despair about his illness; at the same time, he felt caught up in a ‘struggle between systems’ and, particularly, in a ‘fight between the lunar and earthly worlds’.

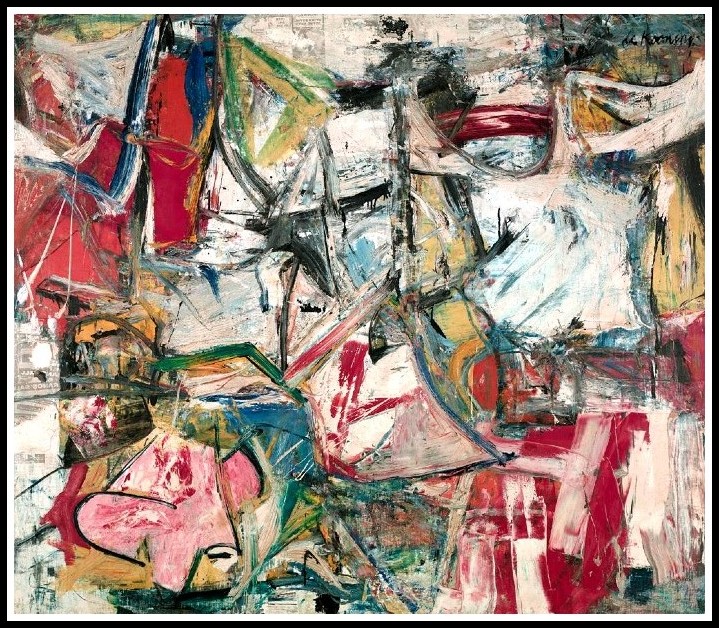

Willem de Kooning, Pirate (Untitled II), 1981

During our third session, I invited Jacques to take some of the modelling clay in different colors that I had on my desk and make something for me. He replied: ‘Every creation of a form is a threat to my existence. The moment I accept a determinate form, I’m lost’. And thus Jacques formulated, out of his disquieting lucidity—that lucidity that very often is the sign of schizophrenia—the central problem facing every schizophrenic: He cannot accept any limit, because the schizophrenic does not inhabit his body. Indeed, schizophrenics live in fragments, each one of which might become a center of their universe. For them, limits and restrictions are equivalent to death, because a limit or restriction would put an end to their state of ‘can-be-everything’ and ‘can-be-everywhere’.

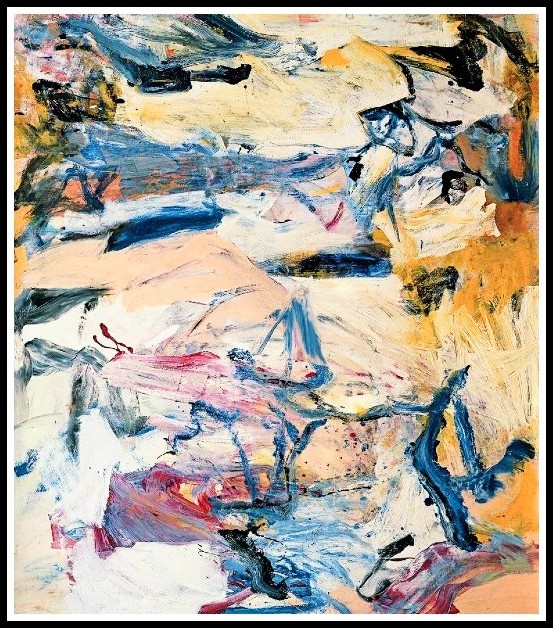

Willem de Kooning, Gotham News, 1955

Two weeks went by before Jacques dared to touch the clay. He made only heads. Once, when he’d made a dog’s head in red, I asked him to whom might that head belong; he was able to recognize it as part of a dog’s body. When I gingerly asked him if he couldn’t model a little more than a head, he pushed the head a meter away from his body; turning very pale and sweating profusely, he then extracted some clay from inside the head and shaped into two appendages to the temples. Exhausted, he then placed his model on the desk. I was trying, in this closed and fragmented world where it is impossible to introduce any outside substance, to induce a waking dream. My hope was that, through speech, this closed world might open up.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled IV, 1978

The dog could not belong to anybody. An old woman, who Jacques called an ‘aunt’, might throw sulphuric acid on the dog’s back if the dog happened ‘to stray between her legs’. Then the dog would go into ‘the uncle’s printing works, where a steel bar would fall on his back’. When the dog would want to escape and cross the road, he would get run over by a car that would ‘cut his tail from his body’. As ‘his tail is very sensitive’, this incident would be enough to kill the dog. I did not try to pursue any associations to do with the ‘aunt’ and the ‘uncle’: I wanted to stay within the spatial dynamics that Jacques had tried to trace. That is why I asked him to describe for me the dog’s burial, the decomposition of his body, and the plants nourished by his corpse. Since the world of the dog represents the way Jacques inhabits his body in relation to the analyst, one can only create a new possibility for inhabiting that body if the old way is completely destroyed.

Willem de Kooning, Two Figures in a Landscape, 1967

It was not by chance that Jacques was able to spontaneously model, very primitively, an entire human body after his parents had come to see me. It is my customary practice to listen to the parents separately, in order to understand what a psychotic child represents and signifies for them. Moreover, I aim to enter into the lived experience of the parents and try to free them from their own parents; I try to give them the right to have a child who is something other than a part of themselves.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled V, 1977

The father, totally incapable of recognizing and accepting that his son was mentally ill, said: ‘It’s a question of willpower; he only has to want to be well.’ This was the father’s way of ‘solving’ all problems and conflicts related to his son’s schizophrenia: hiding behind the superego of his civil-servant world, a superego equivalent to that of his own parents. As this father was uncooperative, it was not possible to see him often enough to ‘discover and understand’; I therefore could not free him from his superego world. I thus had to intervene from neutral ground, and I chose that of a gardener. I asked the father if he had ever noticed that a gardener cannot accomplish ‘everything’ and that, despite all his efforts, the same plant, in the same soil, may develop differently from what he had expected. ‘Who’s fault would that be?’ I caught a glimpse of understanding in this obsessive-compulsive civil servant.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled I, 1977

Jacques’ mother, who did try to cooperate, was marked by her life with this rigid and dry husband. She had never really been able to let down her guard and attain a state of inner joy. If, for the father, the son’s illness went unrecognized and his incapacity was put down to a ‘lack of willpower’, the mother went further and located the guilt in the body itself. ‘At bottom, this son has the bad of both parents within him’, she concluded. The mother thus recognized a symbiosis between son and parents, locating the ‘bad part’ of each parent in the body of her son.

Willem de Kooning, North Atlantic Light (Untitled XVIII), 1977

Given such a symbiosis with the bad, is it surprising that this mother sought a way out via the body itself, in order to control it and expel the bad? Ingeniously, anticipating the breakout of schizophrenia while retracing its development since her son’s earliest infancy, the mother, in her lucid sickness, had invented a rare remedy, at first glance abrupt and brutal, but significant for the family psychosis: Every morning she would weigh, on kitchen scales reserved for this magical and revelatory purpose, her son’s feces. Why? She wanted to check if ‘the bad had left’ the son’s body.

Willem de Kooning, Abstraction, 1949-50

The son, the bad part of the parents; feces, the bad part of the family body: It is the scales, by the weight they indicate, that take on the burden of expelling the bad. This is a world under the spell of the psychosis encompassing the family body, a world pathologically closed to any opening; a world where each person is part of another and an existence in one’s own right—a body lived within its limits and opening out an existence of one’s own, an existence for oneself—is excluded.

Willem de Kooning, Untitled XXII, 1982

The parents’ visit was a hiatus in our work, a fault-like opening into the family’s psychotic depths; it could enable us to gain access to the structuring elements required to repair the symbolizing system, at least in Jacques’ experience of his body. Indeed, he dared to model interesting bodies during the two sessions that followed his parents’ visit—of which he was informed and for which he had offered to make the appointment. Each time the models represented an egg-like figure about twelve centimeters in height. At the top, instead of a head, there was a hat; the feet, formed from clay drawn out of the body, served as a base. The arms were not made by adding clay, but rather by drawing clay off the primitive body and modelling it. They looked, therefore, like fins or vestigial arms. This way of modelling is characteristic of schizophrenics. Indeed, for them, the world of matter—in whatever fragmented form it may occur—cannot bear any enlargement, any ‘prop from outside’. There is a kind of omnipotence in this fragmentary world where anything can become anything and where differentiation according to an immanent law of the body, that is to say a law defining a form and a function that cannot take the place of another form and function, is excluded. Note that the degree to which a schizophrenic indulges in the practice of drawing off matter and leaving behind hollows can serve as an index of the severity of his case.

Willem de Kooning, Quality of a Piece of Paper, 1987

‘Red man with hat and penis despite the clothes’: this is how Jacques presented the first ‘egg body’. In the session that followed, Jacques, despite his state of extreme anxiety, again modelled an ‘egg body’, this time in green. In the place of the missing head he made a red hat, for the first time daring to add clay to make it, whereas the day before he had made the hat from clay drawn out of the body. He presented his model thus: ‘The red man’s brother with hat and penis’. I attempted a waking dream. The day before, Jacques had evoked a worker in a Cuban plantation, a worker who became brutal when drunk. In the present session, Jacques presented ‘a hawker of bread rolls on a beach in Havana’. The man would be stripped of his clothes in the street. Afterwards, he would meet ‘a very powerful snake’ that would bite him ‘very close to his penis’. The man would not be hurt, however, because he’d be wearing a bracelet around his ankle. After a long pause, Jacques continued: ‘Yes, the gypsy also wore an ankle bracelet. She was number 41 on the list of my women’. (He was referring to the list of prostitutes he said he had visited.) Up to now, he had visited forty-three women and had returned to the gypsy fourteen times, whereas he had never returned to any other woman.

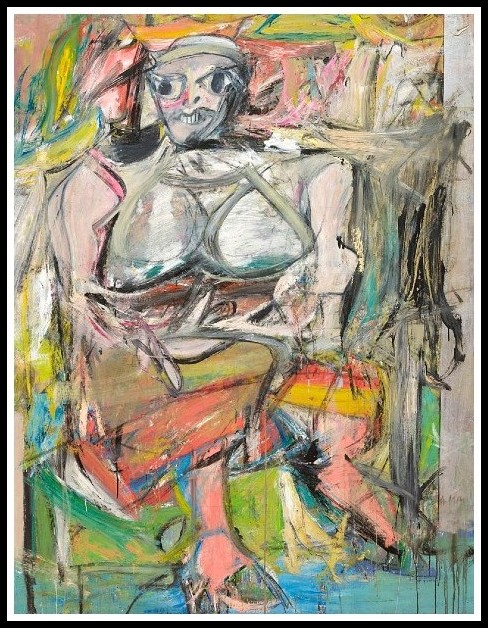

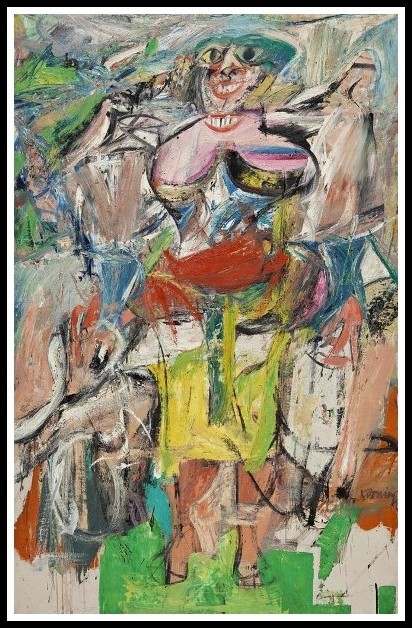

Willem de Kooning, Woman I, 1950-52

He would have liked to have visited the gypsy again last week during my absence (I was attending a conference in Germany); he would have liked, for the first time, to spend a whole night with her. When I asked him why he did not do so, he replied that it would have ruined him financially.

– Why?

– One night with the gypsy would have cost 20,000 to 30,000 francs [$420 to $655 in 2020].

– What? How much is one visit?

– 2,000 to 3,000 francs [$40 to $65].

– But why is one whole night so expensive?

– In May, during the political crisis in France [the return to power of Charles de Gaulle following the collapse of the Fourth Republic in 1958], I visited her only very briefly and gave her 40,000 francs [$875]. I hoped to save France. Had I not paid that high price, France would have been lost.

I tried to establish a link between the high price and the ‘ambitious goal’ of spending a whole night with a woman. If the little boy tried to have sexual relations with his mother, wouldn’t that goal be just as ‘ambitious and unachievable’ as this one? To calm the expected fury of the father, wouldn’t he have to pay just as high a price? And to calm General de Gaulle—‘father of the nation’—and get him to grant one the right to spend a whole night with the gypsy, wouldn’t such a high price be required? The patient relaxed, took a cigarette, and smoked about half of it. Before this moment, he had always put it out after a single puff.

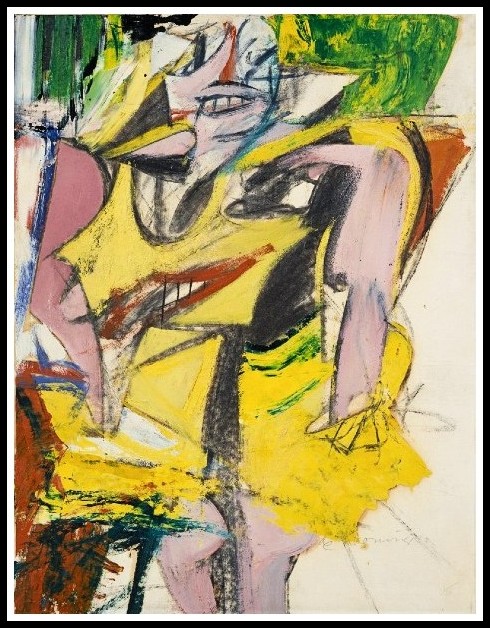

Willem de Kooning, Woman, 1948

Let us try to understand why Jacques was able to open up his world thanks to the structuring image of ‘the gypsy’s ankle bracelet’. First, we have to grasp how the structure of the lived body is involved in and revealed by this dynamic image; next, we have to situate the material of Jacques’ lived story as it was brought to light and structured through ‘the gypsy’s ankle bracelet’. We first see ‘a hawker of bread rolls on the beach’ who, once in the street, gets his clothes stripped off and stolen. Without clothes the man is naked, but this seems to play no role in the difficult human interactions evoked in Jacques’ waking dream. Nobody appears on the scene to intervene. Attracted by this nakedness, something, however, does appear. What? A big, strong snake that bites the man ‘very close to his penis’. The response to the nakedness thus consists in an attack by a snake, making a bite ‘very close to the penis’. While the dog ‘with the sensitive tail’ was destined to die when the car cut the tail from the body, the hawker of bread rolls survives despite the bite.

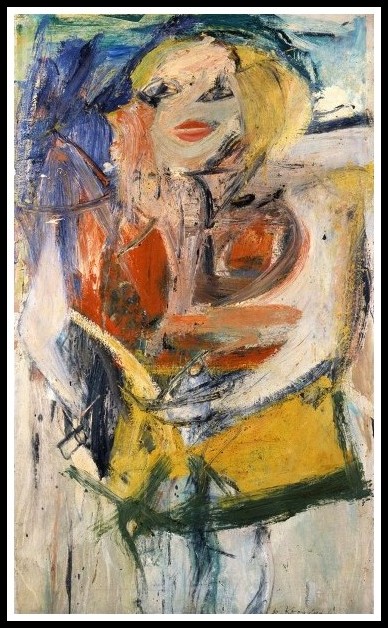

Willem de Kooning, Woman and Bicycle, 1952-53

How are we to interpret the fact that the hawker is protected thanks to the ankle bracelet he wears? First, we can assume that the ‘bracelet protecting the foot’ also protects the penis. Jacques thus understood that a dog’s tail, a penis, and a man’s foot represent the body’s ‘danger zone’. Wearing an ankle bracelet protects the hawker from the snake’s bite; the attack on the naked body is not fatal because the foot is protected by the ankle bracelet. Even if the bracelet is inanimate, as an appendage to the naked body it can be seen as something living. The bracelet surrounding the ankle provides protection; the foot (the penis) is no longer on its own. By piercing another ‘body’ (the bracelet), the foot is protected from being pierced in turn. Such structuring images, which show in dynamic fashion how the body can pierce or be pierced, are the basis of our structuration work. We speak of a ‘structuring phantasy’ that we distinguish from an ordinary fantasy. The phantasy shows us the way in which a schizophrenic inhabits his body, and it enables us to situate him in relation to an ‘other’, so that that ‘other’ may enter into the schizophrenic’s world of desire.

Willem de Kooning, Woman, 1953

Is it a coincidence that Jacques recognized, for the first time, his desire to spend a night with a woman after having evoked the fact that the ankle bracelet of the hawker, who he had spoken of in his waking dream, made him invulnerable? The woman who Jacques wanted to visit is a gypsy, and she is the only woman he was able to visit several times in succession. Was he able to feel secure with her because she wore an ankle bracelet? Can we assume that the danger of ‘being pierced by a foot’ was averted because the gypsy had directed her ‘desire to pierce’ towards another ‘body’, namely the ankle bracelet she ‘pierced’ with her foot? If the bracelet was able to ‘transform’ the body of the gypsy so that Jacques could feel secure with her, all the same, during a political crisis, he had to pay her 40,000 francs [$875] to uphold General de Gaulle in his role of ‘father of the nation’. Jacques, faced with his father’s strict superego, needed a ‘super-father’.

Willem de Kooning, Grumman, 1964

The gypsy’s ankle bracelet, then, enabled us, after eighteen difficult sessions, to gain access to the threatening and threatened world of this schizophrenic. The structuring phantasy of ‘the gypsy’s ankle bracelet’ not only enabled Jacques to safeguard his body in his human interactions, but also to recognize, for the first time and without guilt, his desire for a woman, a sexual partner.

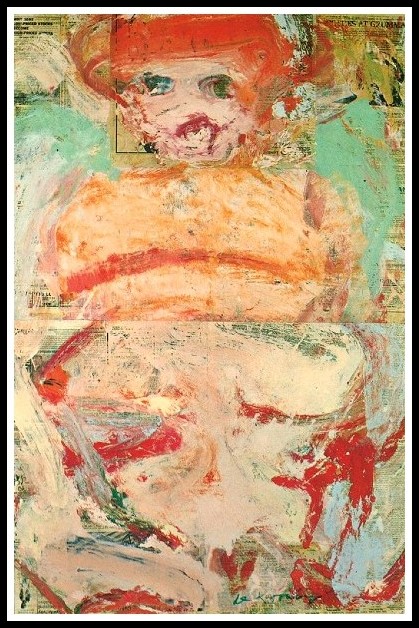

Willem de Kooning, Marilyn Monroe, 1954

MADNESS IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 11

He had gentle hands, my father, but his touch was not enough for me. But it did make being sick less miserable: I could have told you that, but I didn’t.

̶ Did you ever think of becoming a doctor yourself?

̶ Never. I was too busy trying to become a human being.

̶ And just what do you mean by that?

̶ Sometimes when I think of what I’ve been through, I can’t believe I’m still alive.

̶ What happened?

̶ I was buried alive.

̶ Sprague!

̶ It’s been very hard, clawing my way back to the surface.

̶ What are you talking about?

̶ One day, if ever you love me a little, I’ll tell you.

̶ Sprague, you’re frightening me!

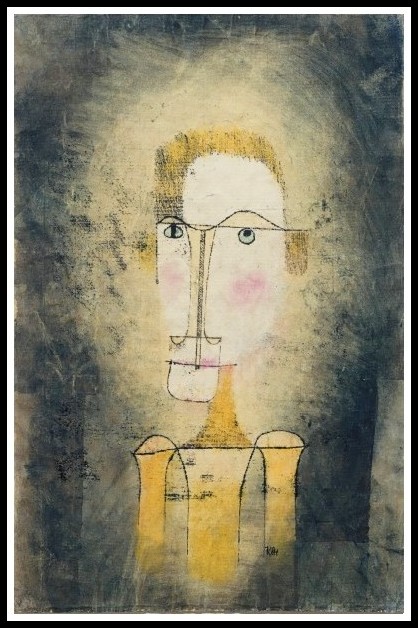

Paul Klee, Portrait of a Yellow Man, 1921

̶ Sorry.

̶ No, I mean…

̶ What?

̶ Your face, your voice—you’re not kidding.

̶ No, I’m not. I know what it is to be dead, Marietta.

̶ Sprague!

̶ Am I frightening you?

̶ No, but…

̶ What?

̶ Just give me some idea what you’re talking about.

Paralyzed, frozen,

Numb: To the last redoubt

I retreated, dumb

̶ I told you: One day, if ever—

̶ Okay, but give me a little clue now!

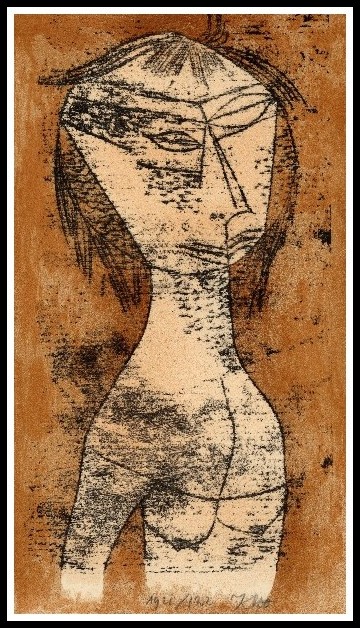

Paul Klee, Diavolo Player, 1923

̶ All right. I was eleven when we took a ship to Canada. No one ever told me why we’re leaving, where we’re going. I had no idea why we were on the boat.

̶ But that’s impossible! Your parents must have told you.

̶ If they did, I didn’t get it. It didn’t register.

̶ You could have asked your sisters.

̶ I have no memory of them even being on the boat! All I remember is feeling totally lost, with no idea of what’s going on.

̶ My God!

̶ And when we arrived at last, in Toronto, the daily torture started.

̶ Sprague!

̶ Outside the house I was a target. Inside, I was invisible. I don’t know which was worse.

Wild, your eyes drill into me.

̶ My mind was a kite in a windstorm. My heart the ball of string. Or maybe it was the other way around.

̶ What do you mean?

̶ Only when the kite was grounded did I feel no pain. I became a zombie. Every day I was stoned.

̶ Drugs?

̶ No. Violence. Cruelty. Humiliation.

Here it comes, the old pain, just like I knew it would.

̶ Sprague!

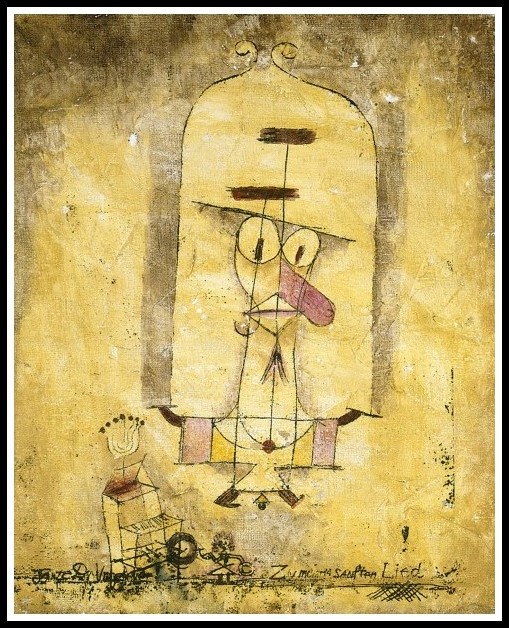

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus, 1920

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Four Chapter 2

A boy slides open a shower curtain. Fǣringa! His heart leaps as a stranger steps out of a mirror. The boy stares into the glass: His face configures a double of the stranger.

Was he insane? Every shower an ordeal, he fearing he’d become unreal should he fall under the spell of the pelting water and forget to think about himself. Unable to inhabit his body, he was incapable of inhabiting the world.

With reading it was the same: Persecuted by his own lucidity, obliged to be permanently aware of himself, he was unable to get beyond the first pages of a book. To lose himself in a narrative, to leave himself behind—that was simply too much of a risk.

And his horror of drugs: When everyone was smoking dope and popping pills, he refused to, afraid that if he got out of his mind he’d never be able to get back in. When he finally took the leap—lipstick on a reefer was something he couldn’t resist—drugs were an anti-climax: Nembutal couldn’t match his own capacity for self-benumbment, nor could marijuana make animals laugh the way he could.

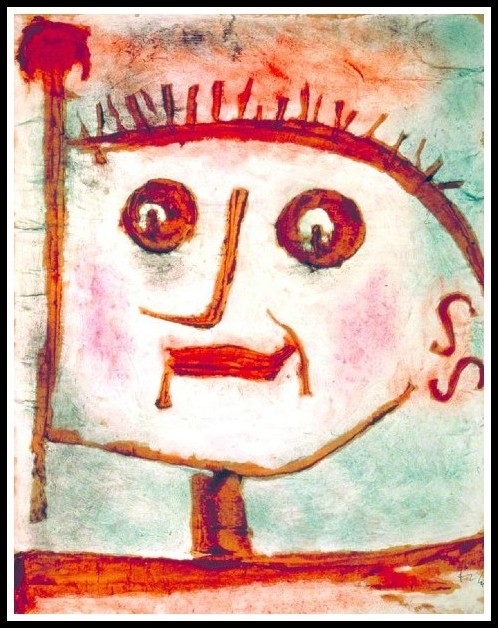

Paul Klee, Nearly Hit, 1928

And, once more, his madness: That time with Phoebe in her basement. She took an atlas off the shelf so he could show her where he comes from. Opening it up, he felt he was opening up a world he might be able to slip into. South Africa, here. East London, Cape Town, the SS Carinthia to Southampton. Stopped over in Madeira. On the ship, an English girl with blue, blue eyes. They stood at the railing, staring at the horizon. She seemed to recognize him. He’d hardly said a word in weeks. He couldn’t form a sentence. She wasn’t afraid. She didn’t walk away. Looking into his eyes, she said: ‘I lingered round them, under that benign sky; watched the moths fluttering among the heath and harebells, listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass, and wondered how anyone could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth.’ He felt himself drowning in the blue of her eyes. ‘That’s the ending of the book I’ve just read. Meet me here tomorrow at ten. I’ll read something new to you.’ The next morning, side-by-side in deck chairs, she read Angela Carter’s Heroes and Villains to him. He began to speak. She took off her glasses and kissed him. He spoke the story. Pages and pages of it. Then she disappeared, the girl with blue, blue eyes, never to be seen again.

Paul Klee, The Saint of the Inner Light, 1921

Had she ever been on the ship? Had he ever read Heroes and Villains? Had it all been a dream? Questions without answers. He was eleven years old. The girl was thirteen. ‘I’ll find her when I get to London’, he told Phoebe, ‘Maybe her mother and father would adopt me’. Why didn’t Phoebe tell him he was mad? That Wuthering Heights and Heroes and Villains are fictions, that he’s neither Heathcliff nor Marianne? Did she believe his fantasy could make him a meaningful world? Did she think the girl with blue, blue eyes was a wish fulfilled in a dream? Or did she believe it’s better not to undeceive him because no girl, not even one with blue, blue eyes, could ever save him?

Paul Klee, Dance You Monster to My Soft Song, 1922

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 8

And now once again I am overcome with love, once again I give thanks for the light: And then the shadow falls. I can’t forget the abortive search, the darkness of asylum; I can’t forget the silent screams, the air grabbed in gasps. Yes, I remember the dread of impending madness, the head-banger banging at my door; I remember the days when I couldn’t be still, fearing I’d lose myself, forget to think about myself, slip out of reality. I’d watch the clock, keep busy, for if I didn’t I’d no longer know who I am. I tried to read, but reading had become a game of infinite regression, an exercise in stealth: Persecuted by my own lucidity, obliged to be constantly aware of myself, I couldn’t accept the coin of signifiers lest it depredate my soul. No girl’s touch came to remind me that the most immediate, the most trustworthy, the most integral source of knowledge is the body. Then again, I didn’t have a body. I was weightless, a wisp of smoke escaping from the citadel of myself, a faint signal of a murdered soul: I was an idiot. Look! Walking across a field of white, a boy feels a tremor running up his spine: He’s just realized the bare feet trudging through the snow are commanded by his mind. Look! The girl in the school bus, the terror in her eyes as the boy stares into them: ‘Know me. I want you to know me’. Look! The creeping rootstalks, the tender grass—look at the boy watching them grow; the mangy dog, the stray cat—see them licking his face. I can’t forget, I can’t forget, I can’t forget!

Paul Klee, Voice from the Ether: ‘And you will eat your fill’, 1939

And I, born into emptiness, had but a flame in my heart, a gentle flame in the last redoubt. And with me, always, the chill chafing of a hand, the hand of madness awaiting me should the flame go out.

Paul Klee, Bird Catcher, 1930