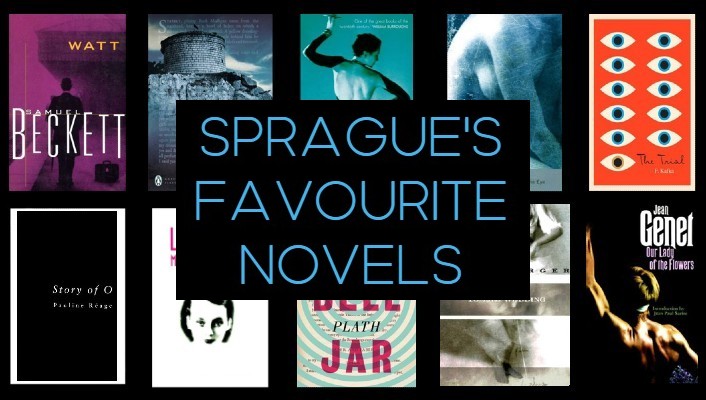

SPRAGUE’S FAVOURITE NOVELS

THE HERO’S ‘SELF-PORTRAIT’ IN TEN NOVELS

This list is an item in the ‘self-portrait’ that Sprague gives Marietta as they part. (He’s the hero, she the heroine, of Mara, Marietta.) Following the excerpt from MM, I present the opening paragraphs of each novel on the list.

Beckett, Watt, 1953

Joyce, Ulysses, 1922

Barnes, Nightwood, 1937

Bataille, Story-Eye, 1928

Kakfa, The Trial, 1925

Réage, Story of O, 1954

Duras, The Lover, 1984

Plath, The Bell Jar, 1963

Berger, To the Wedding, 1995

Genet, Our Lady, 1943

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 6

I reach into my jacket pocket and take out my notebook.

̶ I’ve made a portrait of myself.

I rip out a page and hand it to you.

̶ Will you keep it for me?

You peruse the page.

̶ All right, Sprague. I’ll do that.

MY FAVOURITE NOVELS

1. Watt, Samuel Beckett

2. Ulysses, James Joyce

3. Nightwood, Djuna Barnes

4. Story of the Eye, Georges Bataille

5. The Lover, Marguerite Duras

6. Story of O, Pauline Réage

7. Our Lady of the Flowers, Jean Genet

8. The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath

9. To the Wedding, John Berger

10. The Trial, Franz Kafka

̶ A good self-portrait. But you’ve left it unsigned.

̶ After coming so far for beauty?

Playful, imploring, pensive: your heart in the mirror of your eyes. You fold the paper and put it in your bag.

̶ I’ll keep it. Always. But I don’t need it: I know who you are.

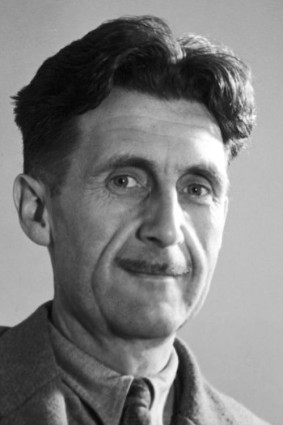

WATT, SAMUEL BECKETT

Samuel Beckett, Watt, 1953

Mr Hackett turned the corner and saw, in the failing light, at some little distance, his seat. It seemed to be occupied. This seat, the property very likely of the municipality, or of the public, was of course not his, but he thought of it as his. This was Mr Hackett’s attitude towards things that pleased him. He knew they were not his, but he thought of them as his. He knew they were not his, because they pleased him.

Halting, he looked at the seat with greater care. Yes, it was not vacant. Mr Hackett saw things a little more clearly when he was still. His walk was a very agitated walk.

Mr Hackett did not know whether he should go on, or whether he should turn back. Space was open on his right hand, and on his left hand, but he knew that he would never take advantage of this. He knew also that he would not long remain motionless, for the state of his health rendered this unfortunately impossible. The dilemma was thus of extreme simplicity: to go on, or to turn, and return, round the corner, the way he had come. Was he, in other words, to go home at once, or was he to remain out a little longer?

Stretching out his left hand, he fastened it round a rail. This permitted him to strike his stick against the pavement. The feel, in his palm, of the thudding rubber appeased him, slightly.

But he had not reached the corner when he turned again and hastened towards the seat, as fast as his legs could carry him. When he was so near the seat, that he could have touched it with his stick, if he had wished, he again halted and examined its occupants. He had the right, he supposed, to stand and wait for the tram. They too were perhaps waiting for the tram, for a tram, for many trams stopped here, when requested, from without or within, to do so.

Mr Hackett decided, after some moments, that if they were waiting for a tram they had been doing so for some time. For the lady held the gentleman by the ears, and the gentleman’s hand was on the lady’s thigh, and the lady’s tongue was in the gentleman’s mouth. Tired of waiting for the tram, said Mr Hackett, they strike up an acquaintance. The lady now removing her tongue from the gentleman’s mouth, he put his into hers. Fair do, said Mr Hackett. Taking a pace forward, to satisfy himself that the gentleman’s other hand was not going to waste, Mr Hackett was shocked to find it limply dangling over the back of the seat, with between its fingers the spent three quarters of a cigarette.

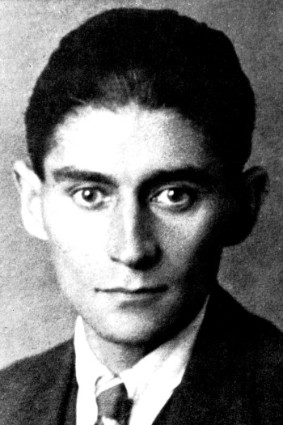

ULYSSES, JAMES JOYCE

James Joyce, Ulysses, 1922

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed. A yellow dressing gown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind him on the mild morning air. He held the bowl aloft and intoned:

—Introibo ad altare Dei.

Halted, he peered down the dark winding stairs and called out coarsely:

—Come up, Kinch! Come up, you fearful jesuit!

Solemnly he came forward and mounted the round gunrest. He faced about and blessed gravely thrice the tower, the surrounding land and the awaking mountains. Then, catching sight of Stephen Dedalus, he bent towards him and made rapid crosses in the air, gurgling in his throat and shaking his head. Stephen Dedalus, displeased and sleepy, leaned his arms on the top of the staircase and looked coldly at the shaking gurgling face that blessed him, equine in its length, and at the light untonsured hair, grained and hued like pale oak.

Buck Mulligan peeped an instant under the mirror and then covered the bowl smartly.

—Back to barracks! he said sternly.

He added in a preacher’s tone:

—For this, O dearly beloved, is the genuine christine: body and soul and blood and ouns. Slow music, please. Shut your eyes, gents. One moment. A little trouble about those white corpuscles. Silence, all.

He peered sideways up and gave a long slow whistle of call, then paused awhile in rapt attention, his even white teeth glistening here and there with gold points. Chrysostomos. Two strong shrill whistles answered through the calm.

—Thanks, old chap, he cried briskly. That will do nicely. Switch off the current, will you?

He skipped off the gunrest and looked gravely at his watcher, gathering about his legs the loose folds of his gown. The plump shadowed face and sullen oval jowl recalled a prelate, patron of arts in the middle ages. A pleasant smile broke quietly over his lips.

—The mockery of it! he said gaily. Your absurd name, an ancient Greek!

NIGHTWOOD, DJUNA BARNES

Djuna Barnes, Nightwood, 1937

As the opening paragraphs of Nightwood are given in DJUNA BARNES, here I give the closing ones.

On a contrived altar, before a Madonna, two candles were burning. Their light fell across the floor and the dusty benches. Before the image lay flowers and toys. Standing before them in her boy’s trousers was Robin. Her pose, startled and broken, was caught at the point where her hand had reached almost to the shoulder, and at the moment Nora’s body struck the wood, Robin began going down. Sliding down she went; down, her hair swinging, her arms held out, and the dog stood there, rearing back, his forelegs slanting; his paws trembling under the trembling of his rump, his hackle standing; his mouth open, his tongue slung sideways over his sharp bright teeth; whining and waiting. And down she went, until her head swung against his; on all fours now, dragging her knees. The veins stood out in her neck, under her ears, swelled in her arms, and wide and throbbing rose up on her fingers as she moved forward.

The dog, quivering in every muscle, sprang back, his tongue a stiff curving terror in his mouth; moved backward, back, as she came on, whimpering too, coming forward, her head turned completely sideways, grinning and whimpering. Backed into the farthest corner, the dog reared as if to avoid something that troubled him to such agony that he seemed to be rising from the floor; then he stopped, clawing sideways at the wall, his forepaws lifted and sliding. Then head down, dragging her forelocks in the dust, she struck against his side. He let loose one howl of misery and bit at her, dashing about her, barking, and as he sprang on either side of her he always kept his head toward her, dashing his rump now this side, now that, of the wall.

Then she began to bark also, crawling after him—barking in a fit of laughter, obscene and touching. The dog began to cry then, running with her, head-on with her head, as if to circumvent her; soft and slow his feet went padding. He ran this way and that, low down in his throat crying, and she grinning and crying with him; crying in shorter and shorter spaces, moving head to head, until she gave up, lying out, her hands beside her, her face turned and weeping; and the dog too gave up then, and lay down, his eyes bloodshot, his head flat along her knees.

STORY OF THE EYE, GEORGES BATAILLE

Joachim Neugroschal, translator

Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye, 1928

I grew up very much alone, and as far back as I recall I was frightened of anything sexual. I was nearly sixteen when I met Simone, a girl my own age, at the beach in X. Our families being distantly related, we quickly grew intimate. Three days after our first meeting, Simone and I were alone in her villa. She was wearing a black pinafore with a starched white collar. I began to realize that she shared my anxiety at seeing her, and I felt even more anxious that day because I hoped she would be stark naked under the pinafore.

She had black silk stockings on covering her knees, but I was unable to see as far up as the cunt (this name, which I always used with Simone, is, I think, by far the loveliest of the names for the vagina). It merely struck me that by slightly lifting the pinafore from behind, I might see her private parts unveiled.

Now in the corner of a hallway there was a saucer of milk for the cat. ‘Milk is for the pussy, isn’t it?’ said Simone. ‘Do you dare me to sit in the saucer?’

‘I dare you,’ I answered, almost breathless.

The day was extremely hot. Simone put the saucer on a small bench, planted herself before me, and, with her eyes fixed on me, she sat down without my being able to see her burning buttocks under the skirt, dipping into the cool milk. The blood shot to my head, and I stood before her awhile, immobile and trembling, as she eyed my stiff cock bulging in my trousers. Then I lay down at her feet without her stirring, and for the first time, I saw her ‘pink and dark’ flesh cooling in the white milk. We remained motionless, both of us equally overwhelmed…

Suddenly, she got up, and I saw the milk dripping down her thighs to the stockings. She wiped herself evenly with a handkerchief as she stood over my head with one foot on the small bench, and I vigorously rubbed my cock through the trousers while writhing amorously on the floor. We reached orgasm at almost the same instant without even touching one another. But when her mother came home, I was sitting in a low armchair, and I took advantage of the moment when the girl tenderly snuggled in her mother’s arms: I lifted the back of her pinafore, unseen, and thrust my hand under her cunt between her two burning legs.

THE LOVER, MARGUERITE DURAS

Barbara Bray, translator

Marguerite Duras, The Lover, 1984

One day, I was already old, in the entrance of a public place a man came up to me. He introduced himself and said: ‘I’ve known you for years. Everyone says you were beautiful when you were young, but I want to tell you I think you’re more beautiful now than then. Rather than your face as a young woman, I prefer your face as it is now. Ravaged.’

I often think of the image only I can see now, and of which I’ve never spoken. It’s always there, in the same silence, amazing. It’s the only image of myself I like, the only one in which I recognize myself, in which I delight.

Very early in my life it was too late. It was already too late when I was eighteen. Between eighteen and twenty-five my face took off in a new direction. I grew old at eighteen. I don’t know if it’s the same for everyone. I’ve never asked. But I believe I’ve heard of the way time can suddenly accelerate on people when they’re going through even the most youthful and highly esteemed stages of life. My ageing was very sudden. I saw it spread over my features one by one, changing the relationship between them, making the eyes larger, the expression sadder, the mouth more final, leaving great creases in the forehead. But instead of being dismayed I watched this process with the same sort of interest I might have taken in the reading of a book. And I knew I was right, that one day it would slow down and take its normal course. The people who knew me at seventeen, when I went to France, were surprised when they saw me again two years later, at nineteen. And I’ve kept it ever since, the new face I had then. It has been my face. It’s got older still, of course, but less, comparatively, than it would otherwise have done. It’s scored with deep, dry wrinkles, the skin is cracked. But my face hasn’t collapsed, as some with fine features have done. It’s kept the same contours, but its substance has been laid waste. I have a face laid waste.

So, I’m fifteen and a half.

It’s on a ferry crossing the Mekong river.

The image lasts all the way across.

I’m fifteen and a half, there are no seasons in that part of the world, we have just the one season, hot, monotonous, we’re in the long hot girdle of the earth, with no spring, no renewal.

STORY OF O, PAULINE RÉAGE

Translator not credited. More’s the pity, as this translation (Corgi Books, 1972) is, in my view, better than the one Richard Seaver did (under the pseudonym Sabine d’Estrée) for Grove Press in 1965.

Pauline Réage, Story of O, 1954

Her lover one day takes O for a walk, but this time in a part of the city – the Parc Montsouris, the Parc Monceau – where they’ve never been together before. After they’ve strolled awhile along the paths, after they’ve sat down side by side on a bench near the grass, and got up again, and moved on towards the edge of the park, there, where two streets meet, where there never used to be any taxi-stand, they see a car, at that corner. It looks like a taxi, for it does have a meter. ‘Get in,’ he says; she gets in. It’s late in the afternoon, it’s autumn. She is wearing what she always wears: high heels, a suit with a pleated skirt, a silk blouse, no hat. But she has on long gloves reaching up to the sleeves of her jacket, in her leather handbag she’s got her papers, and her compact and lipstick. The taxi eases off, very slowly; nor has the man next to her said a word to the driver. But on the right, on the left, he draws down the little window-shades, and the one behind too; thinking that he is about to kiss her, or so as to caress him, she has slipped off her gloves. Instead, he says: ‘I’ll take your bag, it’s in your way.’ She gives it to him, he puts it beyond her reach; then adds: ‘You’ve too much clothing on. Unhitch your stockings, roll them down to just above your knees. Go ahead,’ and he gives her some elastics to hold the stockings in place. It isn’t easy, not in the car, which is going faster now, and she doesn’t want to have the driver turn around. But she manages anyhow, at last; it’s a queer, uncomfortable feeling, the contact of silk of her slip upon her naked and free legs, and the unattached garters are sliding loosely back and forth across her skin. ‘Undo your garter-belt,’ he says, ‘take off your panties.’ There’s nothing to that, all she has to do is get at the hook behind and raise up a little. He takes the garter-belt from her hand, he takes the panties, opens her bag, puts them away inside it; then he says: ‘You’re not to sit on your slip or on your skirt, pull them up and sit on the seat without anything in between.’ The seat-covering is a sort of leather, slick and chilly; it’s a very strange sensation, the way it sticks and clings to her thighs. Then he says: ‘Now put your gloves back on.’ The taxi goes right along and she doesn’t dare ask why René is so quiet, so still, or what this all means to him: she so motionless and so silent, so denuded and so offered, though so thoroughly gloved, in a black car going she hasn’t the least idea where. He hasn’t told her to do anything or not to do it, but she doesn’t dare either cross her legs or sit with them held together. One on this side, one on that side, she rests her gloved hands on the seat, pushing down.

OUR LADY OF THE FLOWERS, JEAN GENET

Bernard Frechtman, translator

Jean Genet, Our Lady of the Flowers, 1943

Weidmann appeared before you in a five o’clock edition, his head swathed in white bands, a nun and yet a wounded pilot fallen into the rye one September day like the day when the world came to know the name of Our Lady of the Flowers. His handsome face, multiplied by the presses, swept down upon Paris and all of France, to the depths of the most out-of-the-way villages, in castles and cabins, revealing to the mirthless bourgeois that their daily lives are grazed by enchanting murderers, cunningly elevated to their sleep, which they will cross by some back stairway that has abetted them by not creaking. Beneath his picture burst the dawn of his crimes: murder one, murder two, murder three, up to six, bespeaking his secret glory and preparing his future glory.

A little earlier, the Negro Angel Sun had killed his mistress.

A little later, the soldier Maurice Pilorge killed his lover, Escudero, to rob him of something under a thousand francs, then, for his twentieth birthday, they cut off his head while, you will recall, he thumbed his nose at the enraged executioner.

Finally, a young ensign, still a child, committed treason for treason’s sake: he was shot. And it is in honor of their crimes that I am writing my book.

I learned only in bits and pieces of that wonderful blossoming of dark and lovely flowers: one was revealed to me by a scrap of newspaper; another was casually alluded to by my lawyer; another was mentioned, almost sung, by the prisoners – their song became fantastic and funereal (a De Profundis), as much so as the plaints which they sing in the evening, as the voice which crosses the cells and reaches me blurred, hopeless, inflected. At the end of the phrases it breaks, and that break makes it so sweet that it seems borne by the music of angels, which horrifies me, for angels fill me with horror, being, I imagine, neither mind nor matter, white, filmy, and frightening, like the translucent bodies of ghosts.

THE BELL JAR, SYLVIA PLATH

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar, 1963

It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York. I’m stupid about executions. The idea of being electrocuted makes me sick, and that’s all there was to read about in the papers—goggle-eyed headlines staring up at me on every street corner and at the fusty, peanut-smelling mouth of every subway. It had nothing to do with me, but I couldn’t help wondering what it would be like, being burned alive all along your nerves.

I thought it must be the worst thing in the world.

New York was bad enough. By nine in the morning the fake, country-wet freshness that somehow seeped in overnight evaporated like the tail end of a sweet dream. Mirage-gray at the bottom of their granite canyons, the hot streets wavered in the sun, the car tops sizzled and glittered, and the dry, cindery dust blew into my eyes and down my throat.

I kept hearing about the Rosenbergs over the radio and at the office till I couldn’t get them out of my mind. It was like the first time I saw a cadaver. For weeks afterward, the cadaver’s head—or what there was left of it—floated up behind my eggs and bacon at breakfast and behind the face of Buddy Willard, who was responsible for my seeing it in the first place, and pretty soon I felt as though I were carrying that cadaver’s head around with me on a string, like some black, noseless balloon stinking of vinegar.

(I knew something was wrong with me that summer, because all I could think about was the Rosenbergs and how stupid I’d been to buy all those uncomfortable, expensive clothes, hanging limp as fish in my closet, and how all the little successes I’d totted up so happily at college fizzled to nothing outside the slick marble and plate-glass fronts along Madison Avenue.)

I was supposed to be having the time of my life.

I was supposed to be the envy of thousands of other college girls just like me all over America who wanted nothing more than to be tripping about in those same size-seven patent leather shoes I’d bought in Bloomingdale’s one lunch hour with a black patent leather belt and black patent leather pocketbook to match. And when my picture came out in the magazine the twelve of us were working on—drinking martinis in a skimpy, imitation silver-lamé bodice stuck on to a big, fat cloud of white tulle, on some Starlight Roof, in the company of several anonymous young men with all-American bone structures hired or loaned for the occasion—everybody would think I must be having a real whirl.

Look what can happen in this country, they’d say. A girl lives in some out-of-the-way town for nineteen years, so poor she can’t afford a magazine, and then she gets a scholarship to college and wins a prize here and a prize there and ends up steering New York like her own private car.

Only I wasn’t steering anything, not even myself. I just bumped from my hotel to work and to parties and from parties to my hotel and back to work like a numb trolleybus. I guess I should have been excited the way most of the other girls were, but I couldn’t get myself to react. (I felt very still and very empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.)

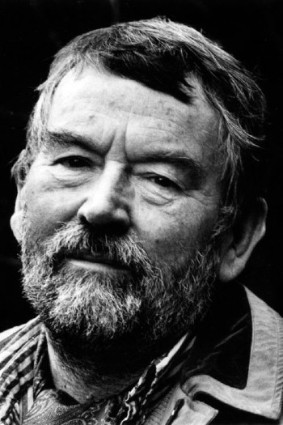

TO THE WEDDING, JOHN BERGER

John Berger, To the Wedding, 1995

Wonderful a fistful of snow in the mouths

of men suffering summer heat

Wonderful the spring winds

for mariners who long to set sail

And more wonderful still the single sheet

over two lovers on a bed.

I like quoting ancient verses when the occasion is apt. I remember most of what I hear, and I listen all day but sometimes I do not know how to fit everything together. When this happens I cling to words or phrases which seem to ring true.

In the quartier around Plaka, which a century or so ago was a swamp and is now where the market is held, I’m called Tsobanakos. This means a man who herds sheep. A man from the mountains. I was given this name on account of a song.

Each morning before I go to the market I polish my black shoes and brush the dust off my hat which is a Stetson. There is a lot of dust and pollution in the city and the sun makes them worse. I wear a tie too. My favourite is a flashy blue and white one. A blind man should never neglect his appearance. If he does, there are those who jump to false conclusions. I dress like a jeweller and what I sell in the market are tamata.

Tamata are appropriate objects for a blind man to sell for you can recognise one from another by touch. Some are made of tin, others of silver and some of gold. All of them are as thin as linen and each one is the size of a credit card. The word tama comes from the verb tázo, to make an oath. In exchange for a promise made, people hope for a blessing or a deliverance. Young men buy a tama of a sword before they do their military service, and this is a way of asking: May I come out of it unhurt.

Or something bad happens to somebody. It may be an illness or an accident. Those who love the person who is in danger make an oath before God that they will perform a good act if the loved one recovers. When you are alone in the world, you can even do it for yourself.

Before my customers go to pray, they buy a tama from me and put a ribbon through its hole, then they tie it to the rail by the ikons in the church. Like this they hope God will not forget their prayer.

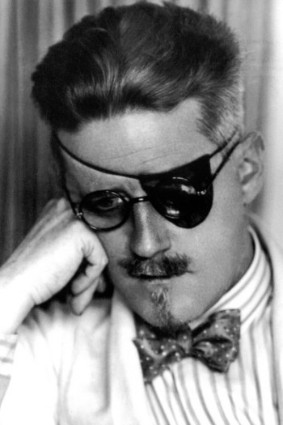

THE TRIAL, FRANZ KAFKA

Breon Mitchell, translator

Franz Kafka, The Trial, 1925

Someone must have slandered Josef K., for one morning, without having done anything truly wrong, he was arrested. His landlady, Frau Grubach, had a cook who brought him breakfast each day around eight, but this time she didn’t appear. That had never happened before. K. waited a while longer, watching from his pillow the old woman who lived across the way, who was peering at him with a curiosity quite unusual for her; then, both put out and hungry, he rang. There was an immediate knock at the door and a man he’d never seen before in these lodgings entered. He was slender yet solidly built, and was wearing a fitted black jacket, which, like a traveler’s outfit, was provided with a variety of pleats, pockets, buckles, buttons and a belt, and thus appeared eminently practical, although its purpose remained obscure. ‘Who are you?’ asked K., and immediately sat halfway up in bed. But the man ignored the question, as if his presence would have to be accepted, and merely said in turn: ‘You rang?’ ‘Anna’s to bring me breakfast,’ K. said, scrutinizing him silently for a moment, trying to figure out who he might be. But the man didn’t submit to his inspection for long, turning instead to the door and opening it a little in order to tell someone who was apparently standing just behind it: ‘He wants Anna to bring him breakfast.’ A short burst of laughter came from the adjoining room; it was hard to tell whether more than one person had joined in. Although the stranger could hardly have learned anything new from this, he nonetheless said to K., as if passing on a message: ‘It’s impossible.’ ‘That’s news to me,’ K. said, jumping out of bed and quickly pulling on his trousers. ‘I’m going to find out who those people are next door, and how Frau Grubach can justify such a disturbance just opposite me.’ Although he realized at once that he shouldn’t have spoken aloud, and that by doing so he had, in a sense, acknowledged the stranger’s right to oversee his actions, that didn’t seem important at the moment. Still, the stranger took it that way, for he said: ‘Wouldn’t you rather stay here?’ ‘I have no wish to stay here, nor to be addressed by you, until you’ve introduced yourself.’ ‘I meant well,’ the stranger said, and now opened the door of his own accord. In the adjoining room, which K. entered more slowly than he had intended, everything looked at first glance almost exactly as it had on the previous evening.