The Art of Fiction

GRAHAM GREENE ON THE NOVEL: AN INTERVIEW

Marie-Françoise Allain

From Marie-Françoise Allain, The Other Man: Conversations with Graham Greene, translated from the French by Guido Waldman (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1984) pp. 119-151. Interview conducted by Marie-Françoise Allain in Antibes in 1979. Intertitles added and text edited by Richard Jonathan. The editing was governed by the decision, firstly, to focus exclusively on Greene’s discussion of the novel, and secondly, to group under one heading remarks on the same topic that were scattered across the interview. Most of the black-and-white photos have been colorized.

Graham Greene | Irving Penn

I. A WRITER HAS TO BE HIS OWN JUDGE

Your loyalties sometimes seem to defy coercion. You have admitted that you are an extremist. Are you also a perfectionist?

I’m not a perfectionist in politics or in love. I try to be a perfectionist when I write. I aim to be content with what I produce. It’s an aim I never achieve, but I go over my work word by word, time and again, so as to be as little dissatisfied as possible. I write not to be read, but for my own relief. My only readership is me. Novelists who write for a public are, in my opinion, no good. They’ve discovered who their readers are and, in submitting to their judgement, they’re dishing things up like short-order cooks. But a writer has to be his own judge, for his novels contain faults which he alone can discern. The harshest judgements should be his own. As a rule I’m quite clear about what I’ve written. I know when it’s good or bad. I know, for instance, that I find it difficult to render action. That’s the hardest thing for a novelist. Hemingway managed it. He wrote The Sun Also Rises fifty times. A street fight is harder to put across than our conversation. So is the notion of time. Take Stamboul Train. It was not a great success from that point of view. I had to compress time for the sake of the action.

Graham Greene | Dmitri Kasterine, 1984

II. WRITING HAS TO DEVELOP ITS OWN ROUTINE

How do you work?

If one wants to write, one simply has to organize one’s life in a mass of little habits. Where writing is concerned, I’m obsessive as it’s a question of life and death. Writing has to develop its own routine. When I’m seriously at work on a book, I set to work the first thing in the morning, about seven or eight o’clock, before my bath or shave, before I’ve looked at my post or done anything else. If one had to wait for what people call ‘inspiration’, one would never write a word. I count my words, I count them all up with my finger. When I’m hard at work, I try to keep to a minimum daily word-count. A chapter contains so many words, and one wants to know exactly how one chapter balances another by its weight in words. For me it’s also a way of forcing myself to work; I used to set myself a quota of at least 500 words a day—which doesn’t mean that I never wrote more. My quota has dropped to 300; when I reach this number I note it in the margin. You’ll find my manuscripts peppered with little crosses and the annotation ‘600’, ‘900’, ‘1,200’, etc. I know by and large how long a book will be when I finish it. As for my ‘productivity’, I used to write a book in nine months, but now it’s one every three years.

Graham Greene, Antibes, 1982 | Ralph Gatti

III. THE ROLE OF THE UNCONSCIOUS

In some of the introductions to the collected edition of your works you mention your chance encounters with your own characters, whom you seem quite surprised to run Into. And yet the style and structure of your books give the impression that you are a writer in total control. How do you reconcile the foreseen and the unforeseen, the unconscious and the conscious?

The craftsmanlike aspect of my work is a very conscious one. I pay attention to point of view, for instance, and I re-read aloud what I have written, making a good number of corrections for the sake of euphony. On the other hand I’ve mentioned the character of Minty in England Made Me. He was quite a minor character to begin with, but he suddenly asserted himself almost to the point of taking charge. In all my novels I’m content to have blank spaces which I don’t know in advance how to fill. The characters are thus able to follow their bent more freely. That’s why the novel is, to my mind, more interesting than the short story. The novelist reserves for himself surprises, which he can’t afford to do in a short story which is conceived almost entire before the writing has begun.

Graham Greene, England Made Me, 1935

When I started to write Travels with my Aunt, I didn’t expect to be able to finish it. This is rather unusual, because generally I can at least anticipate a beginning, a middle and an end. I’d embarked on this adventure for my own amusement, with no notion of what might happen the next day. A number of ideas I expected to use in short stories became recollections of old Augusta. I was surprised that they all cohered into a logical sequence, and that the novel became a finished product, for I’d been regarding it more as an exercise based on the free association of ideas, though I had it clearly in mind that it was to be a book written for the fun of it, on the subject of old age and death. So one shouldn’t speak too much of technique or craftsmanship. I place great reliance on what I take to be the unconscious, no doubt because of my experience of psychoanalysis as an adolescent. This isn’t to say that writing is magic, though magic does take a hand in little touches—the right element to make the various parts cohere drops into place at the proper time without my realizing it. One has to be borne up by a sort of faith in one’s unconscious; one has to maintain good relations with it. One enters into contact with this side of oneself by means of dreams and of those unexpected elements which slip into a novel, and one becomes aware of the role played by the unconscious only at the instant when it materializes, surreptitiously.

Graham Greene, Travels with My Aunt, 1969

So you have to have the sensation of discovering certain things, of being caught unawares?

Oh yes, indeed, this happens with every book. For example Castle, the double agent in The Human Factor, finds at one point that he needs to talk to someone. He goes into a Catholic church. In the confessional there’s a priest who treats him abysmally and suggests that he go and see a psychiatrist. Castle comes out of the confessional, and at that precise moment he realizes that he has come face to face with a man as lonely as he is. I had not anticipated this scene, and I liked it. The priest was not after all gratuitously disagreeable. This took me completely by surprise, because I’d started out with the idea of satirizing a certain kind of priest.

Graham Greene, The Human Factor, 1978

Do you not yourself cultivate this sense of the unreal which these unexpected developments bring about? One has the feeling that your stories are sometimes tales for adults written for your own benefit. I am thinking especially of that strange story in which a sick man returns to the home of his childhood and sees, as he is about to go to sleep, the adventures of the little boy who had gone for a walk ‘under the garden’. What is the meaning of this dream inside a dream about a dream? Is it just a story which you took pleasure in writing?

Oh, I never ‘take pleasure in writing’. But I did perhaps free myself temporarily from the tensions of reality, or rather from too realistic a way of writing. No doubt I wanted to go back to my childhood, because the house depicted in Under the Garden is similar to the one in which we spent our summer holidays. There was also a pond with an island in the middle—and when I went back many years later, like the narrator in the story, I discovered that there was no need for a raft or a boat to take one across to the island. A jump was all that was needed, for the pond was scarcely bigger than a puddle. The gardener, on the other hand, was still the real gardener. I make the same sort of escape in a passage in The Human Factor in which Castle, the adoptive father, tells his son the story of the dragon which hides on the Common and only comes out in order to visit him in school. I never knew a dragon, but as a small boy, I knew of plenty of caves which might have been its lair, because the Common was riddled with trenches dating back to the First World War.

Graham Greene, Under the Garden, 1963

These flights into the fantastic, into what you call ‘fantasy’, to which you return, notably in Doctor Fischer of Geneva, what do they represent for you?

I don’t really know. Perhaps you’re right: I’m escaping. For example, if one can remember an entire dream, the result is a sense of entertainment sufficiently marked to give one the illusion of being catapulted into a different world. One finds oneself remote from one’s conscious preoccupations.

Graham Greene, Doctor Fischer of Geneva or The Bomb Party, 1980

What in your work is the proportion of ‘entertainment’ to these ‘conscious preoccupations’?

I really couldn’t say. In my earlier books I didn’t permit myself many of these flights. The sense of entertainment crops up for the first time in Stamboul Train, and more markedly in England Made Me, but it doesn’t come fully into the open until after 1945. I’ve noticed, in working on the introductions to the collected editions, that all my humorous stories date from the Second World War, as though the proximity of death provoked this irresistible urge to laugh and to ‘unwind’. Travels with my Aunt was also written when I was well up in my sixties, in the awareness that I was gradually approaching the wall that does not give way.

Graham Greene, Stamboul Train, 1932

So you think it is preferable to maintain a certain degree of unconsciousness in order to write a novel?

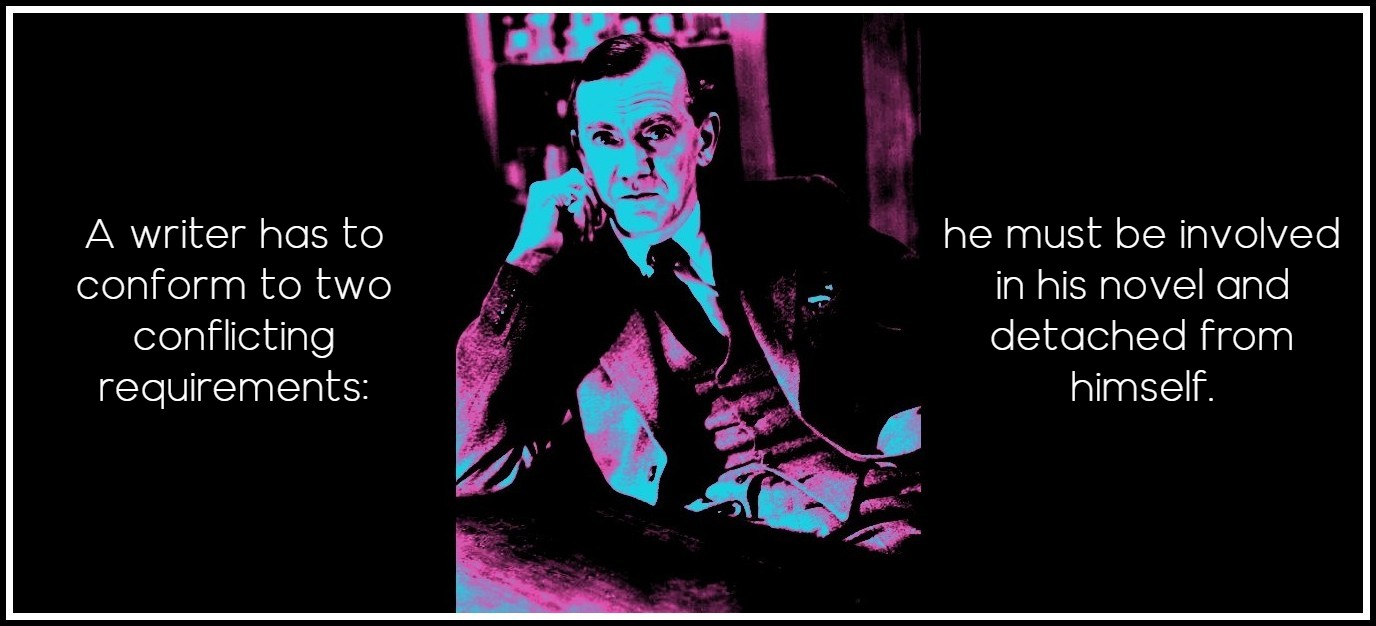

Yes. I can’t stand being made too aware when people highlight obvious links between my novels. These repetitions are necessary and unavoidable, but they need to remain buried in the unconscious of the writer. My first novels, The Name of Action and Rumour at Nightfall, were bad because the romantic young author I was at the time was too recognizable in the characters. A writer has to conform to two conflicting requirements: he must be involved in his novel and detached from himself. One detaches oneself in the course of merging into the characters. One doesn’t think, ‘Would I do this or that?’ One notes that ‘Smith has done it’. One doesn’t even say, ‘How would Smith react in this or that situation?’ because Smith acts on his own account. One simply forgets one’s own existence. It’s not so much a question of taking Ieave of oneself, if you like; it’s more a case of taking leave of one’s conscious ‘I’. Telling one’s dreams to a psychoanalyst every day gives one the same sensation: while the dreams are a part of oneself, in reciting them one has the illusion of their being part of quite another life. Books and dreams have that much in common, I suppose.

Graham Greene | Lida Moser, 1954

What do you do with your first drafts? Do you revise a great deal?

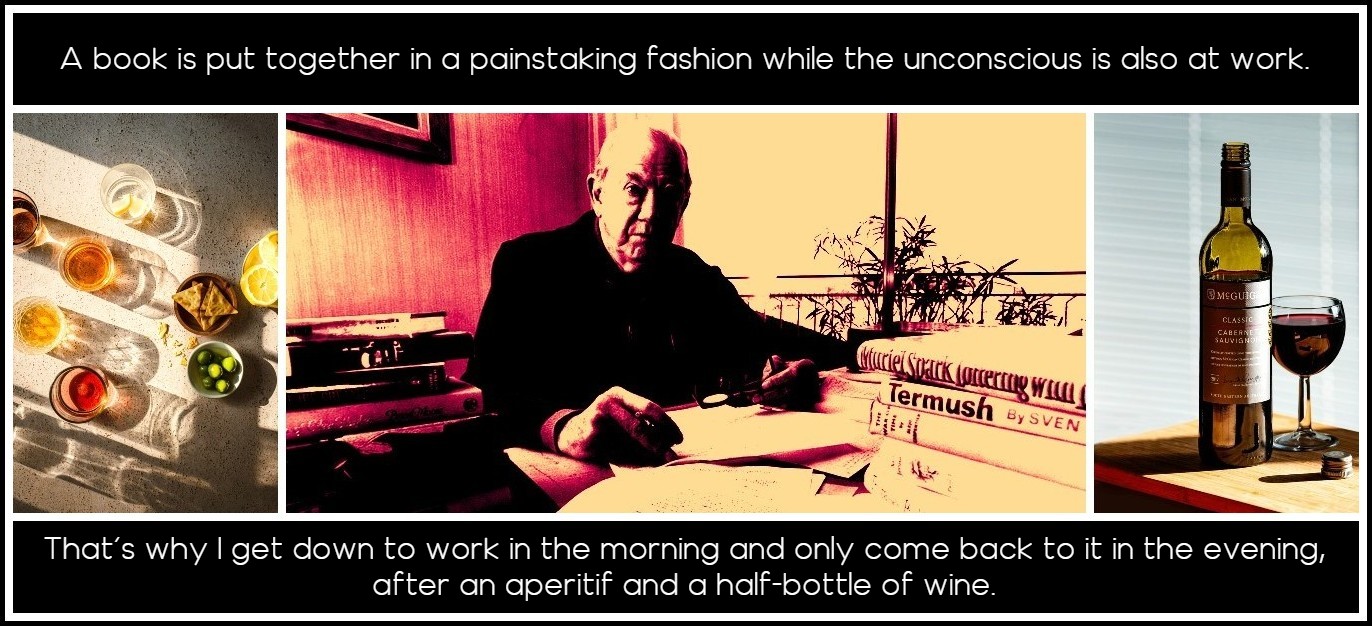

I correct my first draft until even I can hardly decipher it, Then I record it on dictabelts and send it to my secretary who types it out. Afterwards I correct the typewritten copy over and over again until I have to record it on dictabelts again. Sometimes I repeat this operation at least four times. Between the manuscripts and the final typed version I achieve a half-dozen drafts all corrected and recorrected to the point of illegibility. So a book is put together little by little, in a painstaking fashion while the unconscious is simultaneously at work. That’s why I get down to work first thing in the morning and only come back to it in the evening, after an aperitif and a half-bottle of wine. Then I set about corrections, relying on sleep to enable me to complete the work in the morning. I re-read my morning’s work just before bedtime, to stimulate my unconscious—or my subconscious if you prefer—in the hope that it will sort out the problems. In practice the unconscious, faced with secondary difficulties (stylistic or structural in any given chapter), accomplishes its task like a good parent, one who has first inspired the book and now sees it through to the finish. I choose the title, usually, right at the beginning, before I start writing. This means that I have a precise idea of what the book will turn out to be—except for Travels with my Aunt, as I’ve said, and the thriller The Confidential Agent, written under the influence of Benzedrine.

Graham Greene writing in Antibes | Apéritif – Natalie Behn, Unsplash | Wine – Brett Jordan, Unsplash

IV. SIMPLIFICATION OF STYLE

Has the theatre influenced you as a novelist?

I think it’s a necessary release from the solitude of being a novelist. The advantage with a stage play is that I only work at it for six weeks, which is little compared with the two or three years devoted to a book. There follows the work of ‘carpentry’ which I really enjoy: one removes or adds a bit here and there to meet the criticisms of the director and actors. One attends the rehearsals. There one has to take care that the actors don’t distort the rhythm of the play. The theatre is a release. I had recourse to it early on— I started at sixteen. But I don’t see that the theatre’s had any direct influence on my novels. I’ve always enjoyed writing dialogue. I think I’m quite good at it.

Graham Greene

What are the writer’s ‘conscious preoccupations’ you mentioned earlier on?

I don’t obey any particular rules. There are, of course, basic principles to be observed: adjectives are to be avoided unless they are strictly necessary; adverbs too, which is even more important. When I open a book and find that so and so has ‘answered sharply’ or ‘spoken tenderly’, I shut it again. It’s the dialogue itself which should express the sharpness or the tenderness without any need to use adverbs to underline them.

Graham Greene, Antibes, 1978

Your style has grown much simpler, has it not, since A Burnt-Out Case?

Even earlier. It gradually became simpler with The Quiet American and The End of the Affair. My first books were very bad, full of metaphors which I chose for their extravagance, influenced as I was by my readings in the twenties, when I was very attached to the English Metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century, who devoted themselves to highly complex rhetorical exercises. Today my early novels horrify me, they’re so absurd. There’s nothing worse than poetic prose.

English metaphysical poetry’s influence on Graham Greene: ‘There’s nothing worse than poetic prose.’

You never describe your characters directly. One never ‘sees’ the face of Querry, or Castle, even though you give other information about them.

When I read a novel and have to commit all those details to memory—she’s a red-head, she has a long nose, she wears her hair in this way or that, and so on— I get annoyed. I prefer leaving the reader to do this work, to form his own image, so he doesn’t have to worry about forgetting if a character’s hair is straight or curly.

Photos: Oleg Moroz, Unsplash | Getty Images + Unsplash | Mihail Tregubov, Unsplash

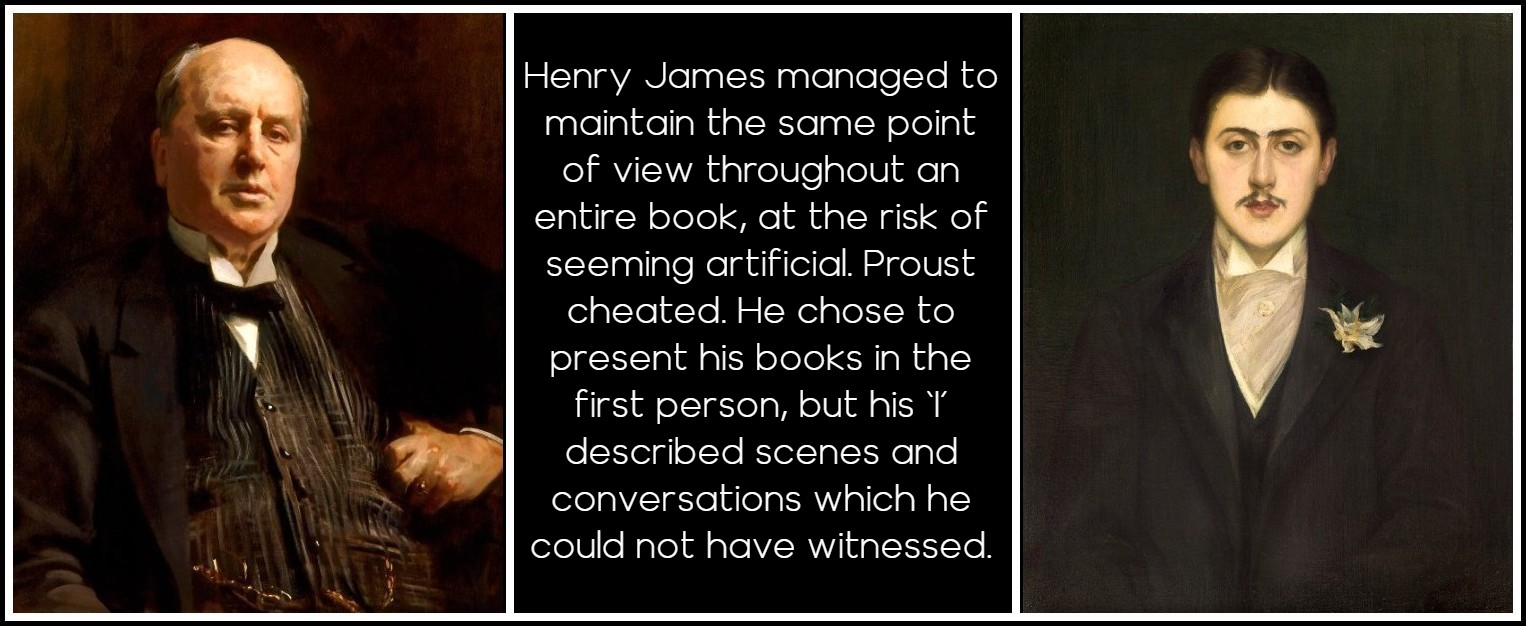

Among the rules to observe, you have mentioned the ‘point of view’. How do you conceive it?

I think that during a scene one must always place oneself in the ‘point of view’ of a single character; this doesn’t totally exclude the author, whose viewpoint may emerge in a metaphor, a comparison or what-have-you. But if you have a scene involving several characters, and you describe it first through one person’s eyes, then through another’s and so on, the whole structure of the scene becomes muddled and loses in intensity. This happens now and then with writers whom I’d call ‘secondary’—and invariably with bad writers. Henry James managed to maintain the same point of view throughout an entire book, at the risk of seeming artificial. Proust cheated. He chose to present his books in the first person, but his ‘I’ described scenes and conversations which he could not have witnessed. It’s a great failing in Proust—on a grand Proustian scale—for the narrative occasionally lacks credibility. Only God and the author are omniscient, not the one who says ‘I’.

John Singer Sargent, Henry James, 1913 | Jacques-Émile Blanche, Marcel Proust, 1892

V. CHARACTERS

What is your relationship with your characters?

I try to be as detached from them as possible. When I feel that the book is on the point of taking off, that the story is coming to a life of its own, I can feel that the characters have a will of their own. I tend to leave them to their own devices. When I construct a scene, I don’t describe the hundredth part of what I see. I see the characters scratching their noses, walking about, tilting back in their chairs—even after I’ve finished writing. So much so that after a while I feel a weariness which does not derive all that much from my effort of imagination, but is more like a visual fatigue: my eyes are tired from watching my characters.

Richard Attenborough & Carol Marsh as Pinky & Rose in the film Brighton Rock | Graham Greene

Your characters, do they not sometimes refuse to come to life?

That’s not a problem. There are always on or two characters who rebel, but that’s almost necessary in a sense; if they all lived with equal intensity, the novels might become over-crowded. One needs a background on which to project silhouettes who don’t necessarily have to take a leading role. My favourite book, the one that bothers me the least, is The Honorary Consul, because I’ve succeeded in showing how the characters change, evolve. And no doubt the next is The Power and the Glory, which was more like a seventeenth-century play in which the actors symbolize a virtue or a vice, pride, pity, etc. The priest and the lieutenant remained themselves to the end; the priest, for all his recollection of periods in his life when he was different, never changed. The action was contained within a short time-span. Now in The Honorary Consul the doctor evolves, the consul evolves, the priest too, up to a point.

Eduardo Barrios, Unsplash

By the end of the novel, they have become different men. That’s not easy to bring off, but I think that in this book I’ve succeeded. But I found writing it hard work; until one reaches a certain point one has to work very hard and with complete lucidity. Then something happens which is rather like an aeroplane taking off; one drives on and on down the runway, suddenly the plane leaves the ground, picks up speed, rises into the air—at that moment one feels a sense of victory. One may have to stay at the controls, but the worst is over. I knew well enough how I would tackle the last chapter of The Honorary Consul. I had all the material I needed. Plenty of choice. It wasn’t organized by my mind, but it was all there, and I relied on my ability to set it down on paper. And yet the wretched book seemed never to take off. It kept rolling along the runway even when the last chapter was approaching. Only when I’d actually finished the novel and discovered that the end worked as I wanted, only then did I realize that we had in fact, quite unwittingly, taken wing a long time before.

Graham Greene, The Honorary Consul, 1973

Are you inspired by people you meet?

No. I think that the main characters always have to exist somewhere within the writer. I might conceivably draw secondary characters from acquaintances, but they’re never the motive force of a book. But your question about characters reminds me of a page from Darwin’s Origin of Species which I was re-reading a little while ago. I had been reading it first when I was writing Under the Garden, with a witch-like character called Maria. Beside the words ‘wild plant’ I’d scribbled the name ‘Maria’. She is a Darwin-borne character. Further on I’d underlined a whole passage where Darwin explains that bumble bees abound near towns and villages where there are cats. The reason is that the cats eat field mice—and field mice are enemies of bumble bees. Around these villages, certain plants grow more abundantly than in places where there are no cats. This is because where there are no cats, the field mice decimate the bumble bees, who used to fecundate the plants. The presence of the plant is indirectly related to the presence of cats. The same is true of characters and creativity. It seems as difficult to trace them back to their origins as it is to trace back the link between the plant and the cat.

Darwin’s The Origin of Species & Greene’s ‘The Origin of Characters’

VI. THE NEGATIVE CAN BE PLEASANT, THE POSITIVE UNPLEASANT

There is an incredible sense of anguish in your novels. How do you explain it? Anguish is a contagious disease.

I’m not conscious of it. I don’t go out of my way to communicate it to the reader. How do you expect one to be able to notice a trait which is so much a part of daily life? I can capture anguish when certain characters betray it, at certain points in a novel, but I don’t recognize it as a constant in my books. This is not to say that you’re wrong, but once again, I don’t want to be confronted with the pattern in the carpet: it would become too much of an obsession. Well, I suppose anguish is perhaps contagious, but I wouldn’t say that a contagious disease is something negative. Where a virus develops in your blood it’s very positive—very active. If I found myself in battle and poison gas was being used, I wouldn’t consider the gas as a negative element. Surely it’s a very positive weapon, because the gas will kill me. It’s most effective. I’m sorry to tease you a little when you say that an illness is negative. Health, now that’s a negative thing. One is in a state of flat calm, one has nothing to fight. The negative can be pleasant, the positive can be unpleasant. I found that boredom was a neurosis until it provoked me to positive action. But one doesn’t react immediately. The negative phase can last a long time, whole days when there’s nothing but boredom. You see why I might be glad to contaminate my readers with anguish? One is more likely to discover love in the midst of war, courage where there is danger.

Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, 1 May 2025 | Photo: Kateryna Klochko/AP

In your Essays you seem to be attracted by Henry James and his way of anatomizing the mechanisms of human behaviour in all its horror.

That’s true. Most people will tell you that James liked to describe delicate scenes of picnics on English-style lawns. One of my reasons for liking Henry James is his sense of corruption and horror. I suppose one can work very hard to accomplish a certain task—writing—and that as a result one can’t be a very diligent husband or lover. Perhaps writers are fickle by temperament, because the individual who finishes a novel bears little resemblance to the one who began it. One lives so long with one’s characters that they tend to influence one. For instance, my last bout of depression, my worst, I think, coincided with the gestation of A Burnt-Out Case. I can find reasons for this in my private life, but also in my two-year cohabitation with the deeply depressive Querry, with whom I never in fact identified myself. The fact is, one is changed by one’s own books. The writer plays God until his creatures escape from him and, in their turn, they mould him.

Graham Greene, A Burnt-Out Case, 1960

VII. POPULARITY

When readers say that they are transported to ‘Greeneland’, everybody understands that they are referring to a kind of atmosphere which you have succeeded in creating. When a paper uses the headline ‘Our Man in Antibes’, the allusion to Our Man in Havana, etc., is grasped at once. What do you think of that?

I’ve acquired a certain popularity which many another author deserved. This is partly because I’m a storyteller, unlike writers of the previous generation such as Virginia Woolf and E. M. Forster. Forster complained, in a study of the novel, ‘Oh, a story, I suppose we have to have a story.’ Well, I’ve always enjoyed telling stories, and my impression is that readers prefer this to the nouveau roman, for instance. The life-expectation of the nouveau roman has turned out to be limited. I like Robbe-Grillet very much, but I think that certain experiments in writing can’t be extended beyond a rather limited number of years. But luck does play a large part in an author’s popularity.

Graham Greene: ‘I’ve acquired a certain popularity which many another author deserved.’

Do you not believe that your success is due to an absence of sophistication?

I try to write more and more simply, but I don’t believe that this makes for attraction, quite the contrary. The really popular books are full of clichés, people ‘flushing with anger’ or ‘going pale with fear’. Popular authors bring nothing new to their readers, and I have no wish to belong to that type of popular writer. On the other hand, I wouldn’t want to belong to an intellectual élite. I don’t dislike intellectuals. I have friends who could be called intellectual. But to my mind the intellectual is often academic and sometimes a shade pretentious.

Graham Greene | Lord Snowdon, 1984

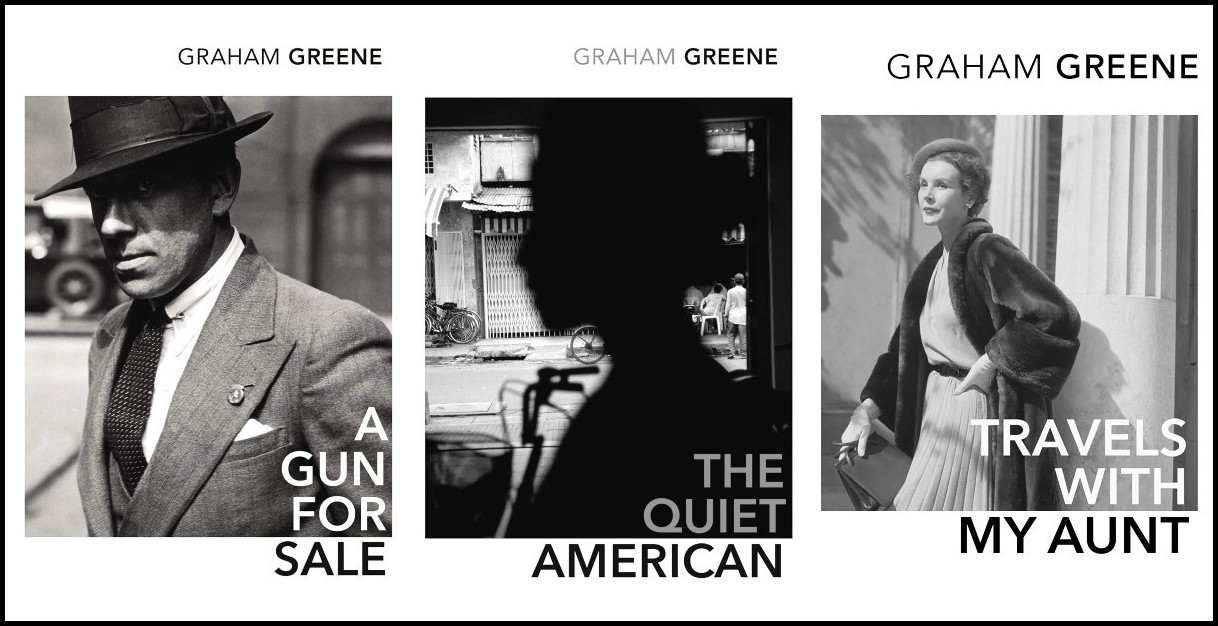

Have you suppressed the distinction between your ‘entertainments’ and your novels in order to escape an excessive popularity?

No. I established the distinction originally in order to escape ‘melodrama’. I’ve subsequently concluded that melodrama isn’t all that baneful. Anyway I told myself—wrongly as it happens—that if I occasionally wrote what in England is termed a thriller, in the manner of John Buchan’s The Thirty-nine Steps, which I greatly admired, the ensuing novel might be free of melodrama. I started making this distinction with A Gun for Sale. I’d even considered writing under another name, but my publisher warned me, ‘We can’t give you more than a £50 advance, because in that case you’re a new writer on the market.’ So I gave up the idea and classed the novel as an ‘entertainment’. The last one to be conceived in this category was The Ministry of Fear. After that, novels and entertainments resembled each other more and more. Brighton Rock, for instance, started in my mind as a thriller. From the first sentence, my intention was to write a crime novel, but the novel eventually moved in quite a different direction. But the most absurd case, I think, is The Quiet American. I recently came across the manuscript, which one of my publishers kept in his safe. The first page is entitled, ‘Novel Number Thirteen—Entertainment’. I really can’t understand how I could ever have seen this book as a simple thriller. I abandoned the dichotomy once and for all with Travels with my Aunt, for it served no further purpose.

Graham Greene: A Gun for Sale | The Quiet American | Travels with My Aunt

VIII. A FINAL WORD FROM MARIE-FRANÇOISE ALLAIN

Graham Greene died on 3 April 1991 in Corseaux, Switzerland.

Graham Greene had said one day, ‘I suppose I am a good popular writer.’ The source of his writing (but only the source) is the adventure novel. What raises him, though, in spite of himself, to the level of the greatest writers is the consummate lucidity of his style, a style as evasive as he is. For in a world where condescension is fashionable, he has been able to stoop without sentimentality to the level of commonplace sorrows, those within anyone’s reach: the nail parings on the unmade bed of brittle love, the blood on the over-polished shoes of Pyle; the evening’s whisky in which the double agent drowns his loneliness, or that unhappy spider slowly suffocating beneath the tooth-mug—all these tangible shreds of life’s absurdity and misery remind us with almost sadistic force of our own secret agonies. Greene forces an entry obliquely, in order to reach for what is universal.

Graham Greene’s grave in the cemetery in Corseaux (Switzerland) | Photo: Vanessa Cardoso

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments