ISAK DINESEN

Susan Hardy Aiken on Isak Dinesen

‘BABETTE’S FEAST,’ TERTIARY SYPHILIS, AND THE CARNIVALIZATION OF THE FEMALE BODY

From ‘Consuming Isak Dinesen’ in Isak Dinesen and Narrativity: Reassessments for the 1990s, Gurli A. Woods, editor (Carlton University Press, 1994) pp. 17-24

Susan Hardy Aiken is Professor Emerita of English at the University of Arizona

This laughter is ambivalent. It asserts and denies, it buries and revives. Such is the laughter of carnival.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World.

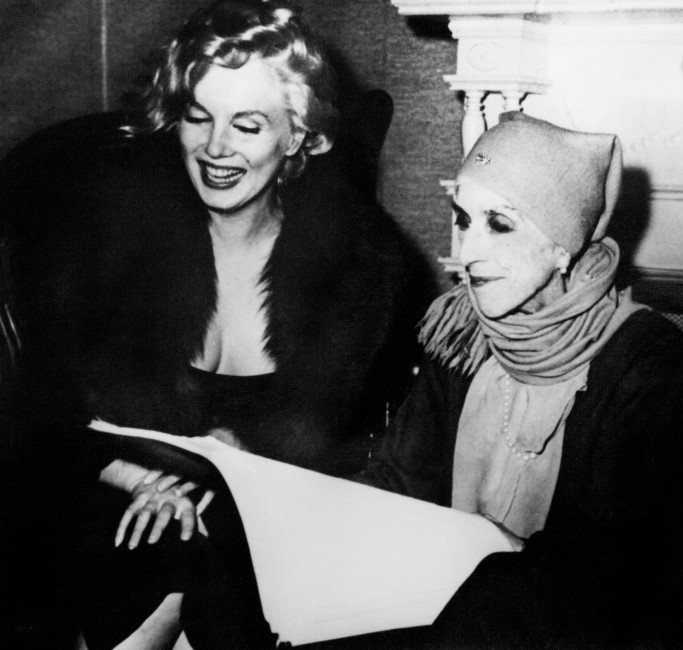

Isak Dinesen & Marilyn Monroe | © Karen Blixen Museet

When Karen Blixen contracted syphilis from her husband in 1914, it was to prove a fatal event in every sense: she would suffer for the rest of her life from the progressively debilitating effects of the disease. Yet like her loss in Africa, her malady also became, paradoxically, a major spur and source of her creativity, as she suggested through her wry description of her syphilis as a sign of the ‘pact she made with the devil in exchange for the gift of story-telling.’ It is hardly surprising that her tales appear so frequently inflected or infected by a poetics of illness, giving new meaning to the ‘decadence’ often associated, rightly or wrongly, with her literary corpus. That poetics becomes especially marked in many of her late productions. Her repeated observation that she ‘died’ into her art, becoming ‘a piece of printed matter’ (Daguerreotypes), was never more poignantly enacted than in the final years of her life, as her body gradually withered to skeletal, wraith-like proportions, and her writing ultimately had to proceed by dictation while she lay supine to ease the pain that racked her. Indeed, given the striking parallelism between European figurations of Africa as a contaminated or disordered body and traditional misogynist figurations of the female body as a primary site of disorder and disease, we might find it uncannily appropriate that it was precisely as disintegrating body that ‘Isak Dinesen’ would be most widely represented in the popular press.

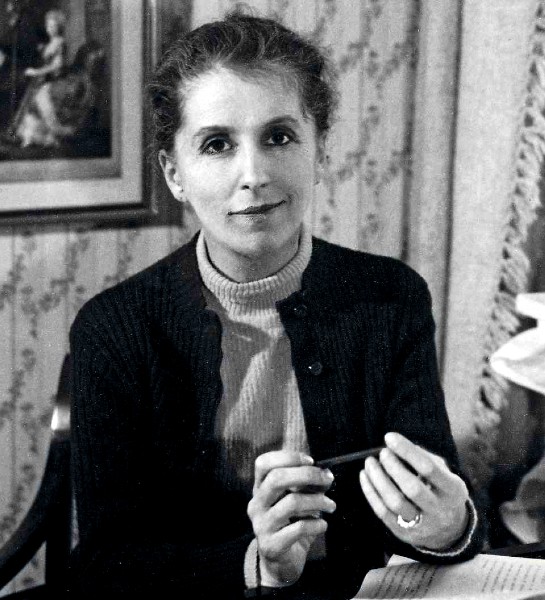

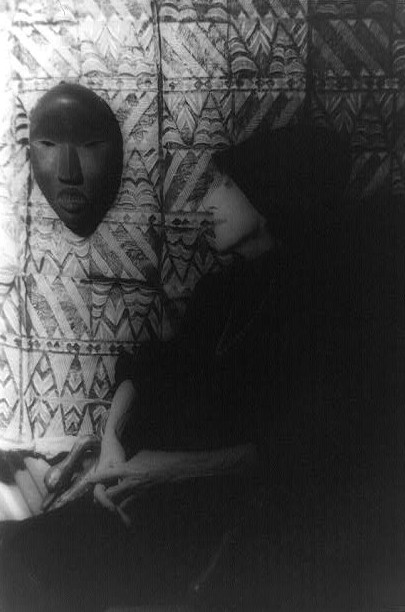

Isak Dinesen as Pierrot | Photo: Rie Nissen

But it was typical of Dinesen that she gallantly made the most even of these effects. In ‘The Diver,’ she had figured ‘poets’ tales’ as ‘disease turned into loveliness’—an apt description of her own narratives, which recurrently celebrate the transformative possibilities of suffering and loss. In related fashion, refusing the masochistic role as victim of her male-authored illness, she fabricated her fragile, disease-ridden body into a living work of art, extending her fiction-making into a wider semiotic space through the elaborate self-stagings which, like her several literary pseudonyms and the labyrinthine complexities of her narratives, concealed or put into question the existence of a ‘real’ Karen Blixen even as they flamboyantly proclaimed her presence. Ambivalent about photography, she nevertheless anticipated by her playful self-imagings the photographers who would find in her aging body such a compelling icon: one recalls especially the stunning late portraits made of her by Peter Beard and Cecil Beaton. ‘Every photograph,’ Edward Steichen has remarked, ‘is a fake from start to finish.’’ So, Dinesen had written, is every person, seen from the observer’s perspective: ‘Your own self, your personality and existence are reflected within the mind of each of the people whom you meet, into a likeness, a caricature of yourself, which still lives on and appears to be, in some way, the truth about you.’ (The passage represents the thoughts of Augustus von Schimmelman [in ‘The Roads Round Pisa,’ Seven Gothic Tales] who regards such representationalism with fear and loathing, but it nicely encapsulates Dinesen’s own repeated acknowledgement of the fabricated quality of the ‘self.’)

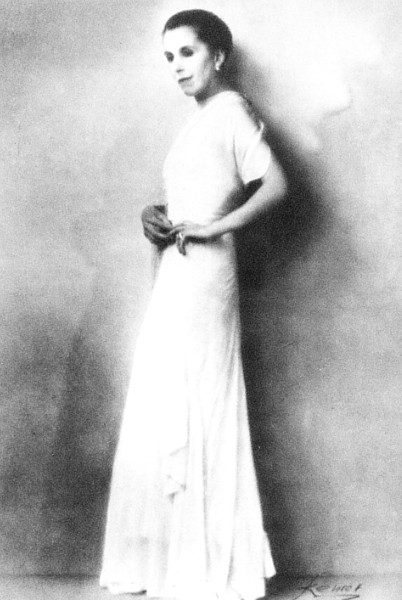

Isak Dinesen, Rungstedlund, 1935

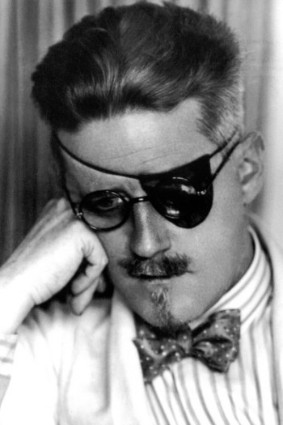

Most spectacular of all were her appearances on stage in her celebrated public readings in America in 1959, her emaciated body so frail that she could hardly stand without support. There she fashioned herself as a radical icon, like a design by Beardsley: dressed all in black, the large dark eyes re-inscribed through the added emphasis of kohl, the parchment-like face chalk-white. Both literally and figuratively, she made herself up, putting into practice the paradox by which she had lived and written: ‘By their masks ye shall know them.’ Posed as ‘herself’ or crafting herself as sibyl, witch, or clown—literally making a spectacle of herself—she transformed her dying body into a speaking text, defying mortality by becoming narrative—a self-consuming artefact in every sense. As she wrote in her posthumously-published ‘Carnival’, ‘Your own mask can give you that release from self toward which all religions strive— mystery, depth, and bliss. Only thus can great works of art be accomplished.’

Isak Dinesen, Rungstedlund, 1958

It is no accident that Dinesen’s compelling female figures repeatedly enact this observation; one recalls, for example, Malin Nat-og-Dag’s self-transformation from ‘death’s head’ to beatific agent of renewal and transcendence in ‘The Deluge at Nordemey’; Pellegrina Leoni’s recreation of herself as a kind of floating signifier, source of displacement and perpetual renewable fictions in ‘The Dreamers’; Anne-Marie, whose self-sacrifice also becomes a life-giving ritual recalling the spectacles of Dionysian vegetation ceremonies in ‘Sorrow-acre’; the ‘Heroine’ Héloise, who, in a spectacular put-on, offers herself as a vital element for the salvational communion of her imperilled compatriots; or Lady Flora Gordon, whose towering figure and ebullient spirits revitalize her fellow sufferers at the sanatorium for syphilitics, and who, reflecting on the sore that signifies her disease, unfolds a deconstructive semiotics focused on the undecidability and instability of the sign—’To what does this bear a likeness? To a rose? or to a seal?’ (Last Tales 98). So also their author presented herself as an enigmatic gift to be consumed by her audiences in her own festive productions, replacing the phallocentric economy, wherein men exchange women, with what Cixous calls dépense, woman’s lavish self-bestowal and generative power that overflows the bounds of restrictive masculine economies. Merging the body of her fiction with the fiction of her body, Dinesen made herself one of the preeminent figures of her own fictional corpus: ‘woman’ as both ‘flesh’ and ‘word.’ ‘And the word,’ as she observed in ‘On Mottoes of My Life,’ ‘taken in such earnest is a mighty thing:’ ‘In hoc signo vinces’ (Daguerreotypes).

Isak Dinesen, 1934 | Photo: Kehlet

Through such forms of serious play, ludic spectacles in which her body appeared resurrected from apparent ‘death’ through the medium of her own figuration, Dinesen composed herself into the very image of feminine generativity—suitable occasion for the ‘laughter’ inherent in the etymology of her pseudonym. A feast for the eyes or for the mind, at once consumed and consuming, she acted as both sign and signifying agent; her iconic self-representations, a festive celebration of the possibilities of feminine art, evoked a surplus unconfinable within a phallocentric economy. In her favourite role as ‘the storyteller who was three thousand years old and had dined with Socrates,’ she resembled the ‘laughing’ terracotta figures of old women that Bakhtin identified as the transgressive epitome of carnival: her body, like theirs, became the triumphal, uncanny image of ‘death that gives birth,’ combining ‘decaying and deformed flesh with the flesh of new life, conceived but as yet unformed’ (Bakhtin).

Isak Dinesen

Indeed, in her various playful poses as jester, transvestite, trickster–all prime agents of disruption—her reflexive enactment of parodic ‘laughter’ and what, describing woman’s subversive discourse, she had called ‘fearless’ feminine ‘heresy, ‘ Dinesen, like the ‘witty woman’ she had extolled in ‘The Deluge at Norderney’ (Gothic Tales), explicitly cast herself as an extravagant embodiment of the ‘carnival’ spirit, that spectacular outburst of energy that inverts, mocks, and destabilizes the dominant phallocentric social order. Textualizing woman’s body through both her literary corpus and her own carnivalesque poses and self-theatricalizations, she put quite literally into practice that ‘play with mimesis’ which, as Irigaray would later claim, allows women to subvert even as they seemingly conform to hegemonic cultural codes. Since phallocentric culture makes the female body a primary site of contestation, the originary property of which, in the Name of the Father, woman herself must be dispossessed, for a woman to (re)claim that body, to mimic ‘woman’ as spectacular object while simultaneously asserting her position as signifying subject, is to refuse the economy of masculine possession and exchange that would appropriate her, and to express, through the very process of feminine masquerade, that ‘elsewhere’ of another meaning, unspeakable within a phallocentric symbolic order. As Mary Russo astutely remarks in ‘Female Grotesques: Carnival and Theory’, ‘to put on femininity with a vengeance suggests the power of taking it off.’

Isak Dinesen

Similarly, to give centre stage to that which patriarchal culture marks as eccentric, marginal, deviant, and pathological—the old woman’s scandalous, diseased body as both subject and object of desire—is to play havoc with the reigning socio-symbolic order by opening it to the very forces it would most insistently cast out in the Name of the Father: autonomous femininity, illness, and mortality—all treated within traditional Western culture as contaminations that imperil both the phallic body and the phallocentric body politic. In this sense, Dinesen’s diverse self-fabrications as story/teller might be read not as ratifications of repressive ideologies or conformity to a consumerist economy but rather as disorderly enactments, in the most literal sense, of a radical écriture féminine: a writing of her body which was also a profound commentary on the body of her writing. Such a double inscription literally incorporated the linguistic interplay of theatre with theory, for as Cixous suggests, écriture féminine operates as a contestational form of theorizing woman’s place in a phallocentric culture and discourse. Dinesen’s play also recalled the common etymological roots of incarnation and carnival—what, in Out of Africa, she had called ‘the flesh made word’. Such performances were, in every sense, gestures of recuperation.

Isak Dinesen

These conjunctions are brilliantly interwoven in ‘Babette’s Feast,’ that consummately festive narrative about consumption. In its evident self-reflexivity, the fiction implicitly affirms Dinesen’s artistic transcendence of her own carnal infirmity through the story of the celebrated female chef who, after years of exile and anonymity, brought about precisely by her commitment to social revolution, simultaneously sacrifices and reclaims herself through the ‘great art’ of the feast she prepares for the assembled guests. Her subversive import is apparent from the outset: ‘massive, dark,’ and ‘deadly pale’—a woman who, like her author, knows what it means to have lost everything—she arrives ‘haggard and wild-eyed like a hunted animal’.

Stéphane Audran, Babette’s Feast, Gabriel Axel

Achille Papin’s letter suggests her revolutionary implications for a patriarchal symbolic order through the unintentional double entendre inherent in his definition of the term ‘Petroleuse,’ a ‘word used for women who set fire to houses’. Twelve years later, ostensibly to celebrate the name, day, and memory of the Father whose preternatural phallic power haunts his daughters’ lives, Babette overawes the unsuspecting sisters with the ‘incalculable nature and range’ of her culinary project, for which she imports strange, ‘undefinable’ objects and creatures, ‘monstrous and terrible to behold,’ converting the father’s sacred day and the confining paternal ‘house’ into sites of ‘a witches’ sabbath’ presided over by Babette as a kind of supernatural figure, ‘like the bottled demon of fairy tale grown to such dimensions that her mistresses felt small before her’.

Nightmare of the “Witches’ Sabbath”, Babette’s Feast, Gabriel Axel

Out of her labours comes a meal beyond imagining, a feast that undoes established oppositions and unsettles hegemonic identities and discourses: the urbane, articulate general is ‘startled’ into ‘silence,’ ‘seized by a queer kind of panic’, while the ordinarily ‘taciturn’ parishioners receive ‘the gift of tongues’. Transported into an ‘exalted state of mind,’ lifted ‘off the ground, into a higher and purer sphere’, all are moved to contemplate what ‘one might venture to call miracles’. In Dinesen’s figure of this dinner as ‘a kind of love affair’, woman’s art becomes a source of jouissance, that blissful state of openness ‘in which one no longer distinguishes between bodily and spiritual appetite or satiety.’ The meal her guests consume is at once a resurrection and a kind of secular Eucharist.

Babette’s Feast, Gabriel Axel from Isak Dinesen

Emblematized by the sarcophages that mark it as her production, it revives those long ‘dead,’ effecting a regenerating, carnivalizing outpouring of good spirits in every sense, a festive transubstantiation in which oppositions like ‘righteousness and bliss kiss one another’. In this enchanted comic space, ‘anything is possible’: the assumed boundaries between body and soul, self and other, past and present are momentarily abolished, and ‘time itself’ is ‘merged into eternity’. Inspired by the ‘intoxication’ of the woman’s ‘blessed’ art and the ‘infinite grace’ of the festival, the celebrants experience a kind of psychological ‘millenium’ that heals old wounds and reconciles deeply-entrenched differences in ‘a heavenly burst of laughter’. It is a ‘miracle’ of multiple incarnations—flesh, quite literally, made word in a stream of overflowing benedictions, a kind of linguistic excess: ‘Bless you, bless you, bless you,’ like an echo of the harmony of the spheres rang on all sides’.

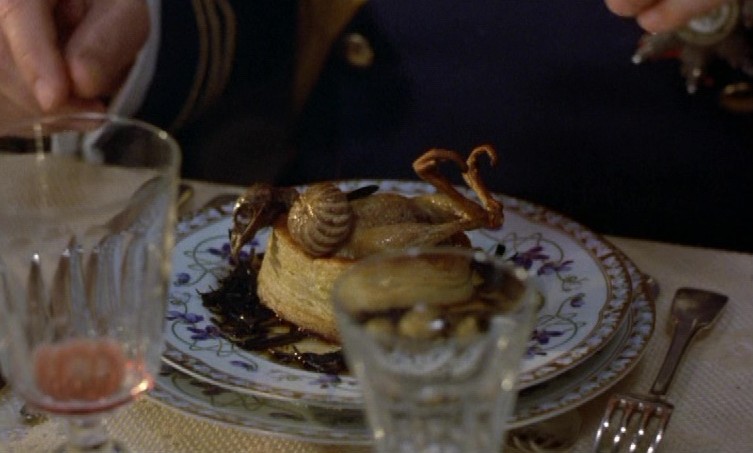

‘Cailles en sarcophages’, Babette’s Feast, Isak Dinesen

The reflexive connection of Dinesen’s own ‘self’-sacrificial art with Babette’s is made explicit in the concluding scene. As Dinesen implies through the sarcophages that epitomize Babette’s creation, it is ultimately the woman’s own body that is offered up, in displaced form, through the culinary corpus she prepares. It is no accident that afterward she is found, ‘deadly exhausted,’ ‘on the chopping block’. Having ‘given away all [she] had’ to create the feast, she is emptied out, left again with nothing—in effect consumed by her own artistic production. For the sisters, this ‘self-sacrifice,’ like the festival it enables, is ‘beyond comprehension’.

Stéphane Audran, Babette’s Feast, Gabriel Axel

The discourse on art with which Babette answers their condolences also illuminates the simultaneous self-annihilation and self-creation Dinesen associated with her own engendering of narrative: ‘A great artist is never poor. We have something of which other people know nothing. Through all the world there goes one long cry from the heart of the artist: Give me leave to do my utmost!’. It is poignantly appropriate that she wrote ‘Babette’s Feast,’ that splendid celebration of transformative consumption, at a time when she herself was beginning slowly to starve to death, her own body literally devouring itself. In this, as in many of her other fictions and public performances, the female body becomes the duplicitous corpus whereby woman projects ‘woman’ as a form of fabrication associated with a transformative vision of narrative, a festive enactment of the redemptive possibilities of a certain ‘feminine’ writing in the face of illness, suffering, loss, and death.

Stéphane Audran, Babette’s Feast, Isak Dinesen

In the posthumously-published ‘Carnival’—which was, of course, also one of her earliest texts and hence brackets her entire career—Dinesen narrates these interactions of carnality, incarnation, and carnivalization as a process of infinite play with identity, a destabilizing fluidity of sexual rules and roles that writes woman’s generativity as the blissful ‘joke’ that undoes both paternal preeminence and the order(s) it has underwritten in the Name of the Father: ‘Like all women, she believed in her heart in the immaculate conception, and did not give the father a thought’. In this mobile, laughing space of creation, woman may change ‘the rules of the game’ by posing the ‘self’ as a dynamic of multiplicity and perpetual transformation rather than uniformity and stability, rupturing the reigning symbolic order with a burst of bawdy puns that declare her desire and voice as ‘musical’ significations outside the strictures of phallocentric law: ‘You are mistaken when you think that we love cocks—we love nightingales. We want a melody that repeats itself, and will go on. Alas, that you cannot play us’.

Figs as sexual cipher, Babette’s Feast, Gabriel Axel

Here, as in Out of Africa and elsewhere in Dinesen’s oeuvre, the nightingale, that Ur-figure of the wounded woman, also becomes the image of blissful creativity: ‘a long ecstatic festival of song’ (Daguerreotypes). Just as Philomela, quintessential embodiment of woman’s displacement, dismemberment, and enforced muteness, filled the world with the ‘abundance and sweetness’ of her music, so Dinesen, out of radical discontinuity, bodily decay, incalculable loss, and death, fabricated narratives which, as she wrote in ‘The Blank Page’ of ‘all old story-telling women,’ make ‘silence speak’, turning malady into melody ‘that repeats itself, and will go on.’

North Italian School, Still Life with Lemon, Bird and Bouquet of Flowers, 18th c.

This ebullient, paradoxical spirit informs the final line of ‘Carnival,’ which proclaims the end of final lines: ‘Everything is infinite, and foolery as well’. That vertiginous double entendre (spoken by a woman disguised, like her author, not only as a man but as a mask—the commedia dell’arte character Arlecchino) might be read retrospectively as a carnivalizing commentary on Dinesen’s own narratives, both written and lived. Dissolving the boundaries between youth and age, health and sickness, truth and fiction, body and text, the notion of ‘infinite foolery’ recalls the ‘laughter’ inherent in the name with which she signed her literary corpus. And if that laughter is infectious, what it signifies is not contagion or disease, but the inexhaustible play of language which resists, by its ludic subversions of stable placement, the ontological structures on which hegemonic definitions of ‘male’ and ‘female,’ ‘selfhood’ and ‘otherness,’ ‘civilization’ and ‘barbarism’ rest. As with the narratives of Scheherazade, to which she so often compared her own, Dinesen’s ‘infinite foolery’ leads not to domination and death, but to the freedom and perpetually revitalizing possibilities inherent in what she called ‘immortal story.’

August Macke, Ballets Russes I (Schumann, Carnaval), 1912

ISAK DINESEN IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo I: Lilo

Lilo’s in love with Karen Blixen. She told me so, last Saturday over wine and cheese at the Café Engel. All day she had Katie skipping across the gutters, from panel to panel, her quick fingers rifling cosmetic counters and racks of silken lingerie. Come evening, the work having gone so well, she was euphoric.

̶ Isak Dinesen’s right, Sprague. Playing with personas is more rewarding than pretending to be yourself.

She dabs some pear jam on her pecorino and bites into the rustic bread.

̶ It’s naïve, pretending to be yourself?

She sips her wine, a dark Valpolicella.

̶ Yes. It means you have no distance, you take yourself too seriously.

̶ And what were Blixen’s masks?

̶ Spiritual courtesan, Baroness, witch, siren, Isak Dinesen. That’s what kept her free, those aliases.

The wrap bodice and dolman sleeves, the low-cut crossover tucked into the deep waistband: She wears it well, Liselotte, the vintage top I bought her for her birthday.

Karen Blixen at Rungstedlund | © Karen Blixen Museet

̶ Don’t you think Karen’s example could serve you, Sprague?

She pops a hazelnut into her mouth and dabs onion jam on her burrata.

̶ What do you mean?

̶ Well, your letter to Marietta—she’ll never read it. Why don’t you just write more stories like Katie Quickfinger? Something less personal. Wear a mask, forget yourself.

Revelling in the burrata, she mops more up with a piece of bread and pops it into her mouth.

̶ Like Isak Dinesen?

̶ Yes.

I sip my Tocai Friulano, ordered in honour of Pasolini.

̶ I play the hand I’m dealt, Lilo. I play it the best I can. Time will tell whether I’ve wasted my time. Do you know the hand Karen Blixen was dealt?

̶ Yes. I’ve read Out of Africa.

̶ That’s another mask, that’s mythology. You can see Isak’s hand in it, but not Karen’s cards.

̶ And do you know the hand she was dealt?

̶ I do.

̶ Tell me.

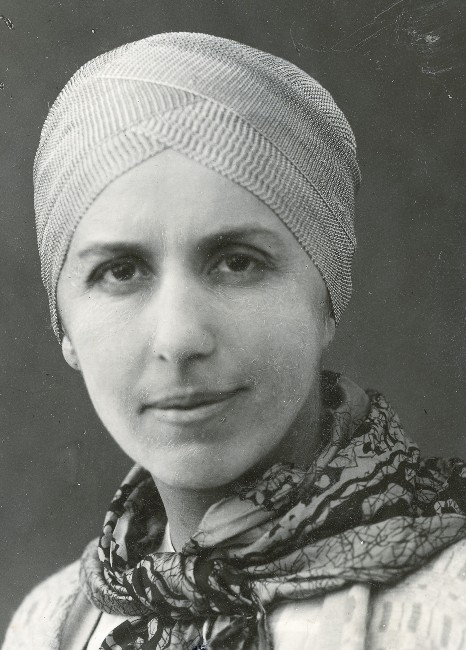

Karen Blixen, passport photo | © Karen Blixen Museet

And thus I came to speak of how syphilis forfeited Karen’s claims to a real human life. Of how, when she was ten, her father hanged himself in a boarding house because he couldn’t bear to live with the disease. And then, as if by some transgenerational curse, she herself, within a year of her marriage, contracted the disease from her husband. ‘Light comes from darkness’, she’d written, ‘daybreak from night’: Stoical, undaunted, she believed her storytelling talent blossomed precisely because she had decided to live with her syphilis. Her sexual life sacrificed, she fell back on her imagination. The scandal of the disease, the secret, the taboo, meant that she led a double life, shuttling between intimacy and alienation. And thus, isolated, self-absorbed, condemned to be her body while feeling herself other to it, she developed an ironic distance to herself that was both alienating and liberating—and made her the artist she became.

Liselotte sips the ruby-red darkness of her Valpolicella.

̶ So you see, Lilo, every artist has their own curse.

Over her grey eyes comes a blue cast; over her face, a shadow.

Isak Dinesen – African Mask | Photo: Carl van Vechten, 1959