Could an artist in the vein of Miller make his voice heard today?

HENRY MILLER: OBSCENE OTHER OF THE LAW

Rob Herian

Posted by kind permission of Robert Herian, Professor, Centre for Science, Culture and the Law, University of Exeter

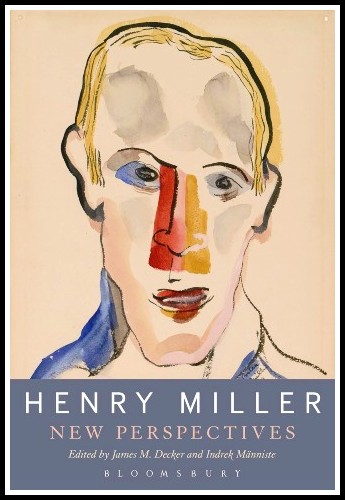

From Henry Miller: New Perspectives, edited by James M. Decker & Indrek Männiste (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015) pp. 95-108

Let each one turn his gaze inward and regard himself with awe and wonder, with mystery and reverence; let each one promulgate his own laws, his own theories; let each one work his own influence, his own havoc, his own miracles. Let each one as an individual assume the roles of artist, healer, prophet, priest, king, warrior, saint.

Henry Miller, The Cosmological Eye (Norfolk: New Directions, 1939) 174-175

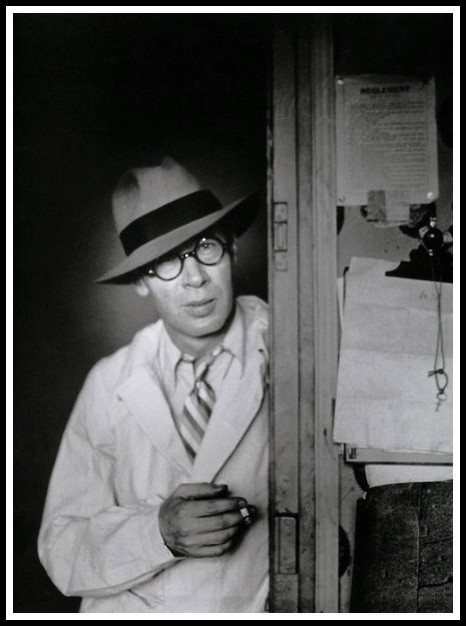

Brassaï, Henry Miller, 1931

I. INTRODUCTION

Ban Henry Miller! Do it, as this might be the only way to save what is truly great about this writer. Take his books from the shelves. Put them out of the reach and the delectation of the public. Take them from the musty, dusty shelves of the bookshop. Hide Miller’s books from the lustful, hungry roving eyes and the all-consuming gaze. Wrap Miller’s Tropics and his triadic Rosy Crucifixion in deep circumspection. Disguise and mask if you like in the improvised jacket of the bootlegged edition, just make sure those books slip from the conscious imaginings of the many. Conceal, disavow, reject, deny, overlook, but above all let the mainstream and all those that jump on the fashion wagon once more return to a state of blissful ignorance where Miller is concerned.

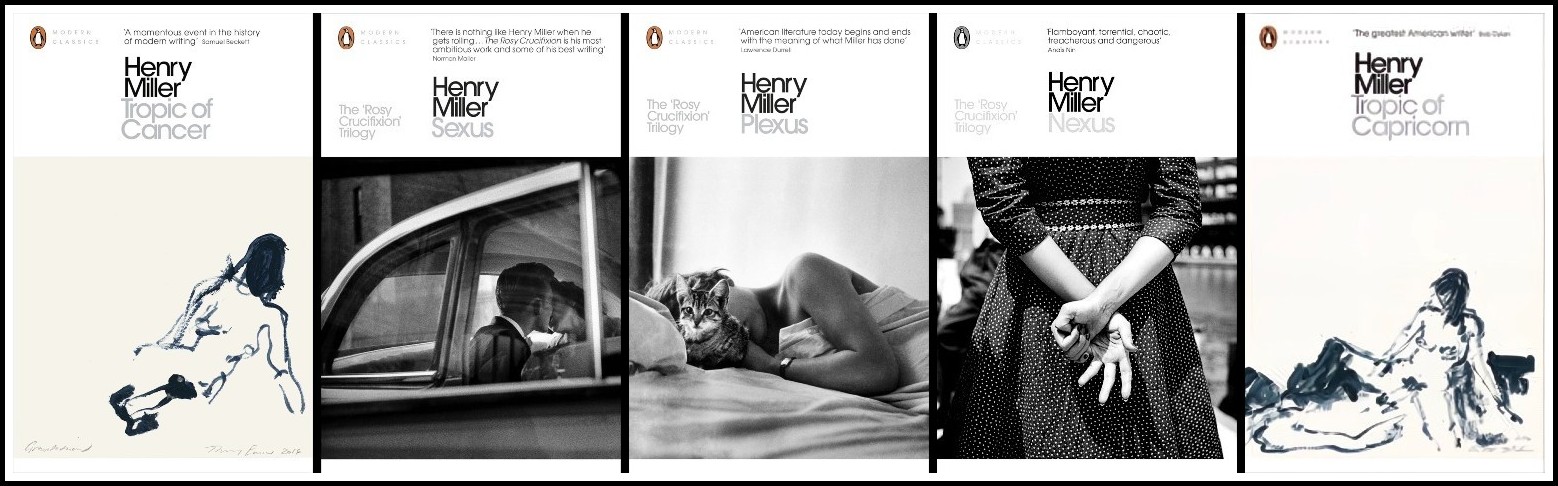

Henry Miller: Tropic of Cancer, The Rosy Crucifixion (Sexus, Plexus, Nexus), Tropic of Capricorn

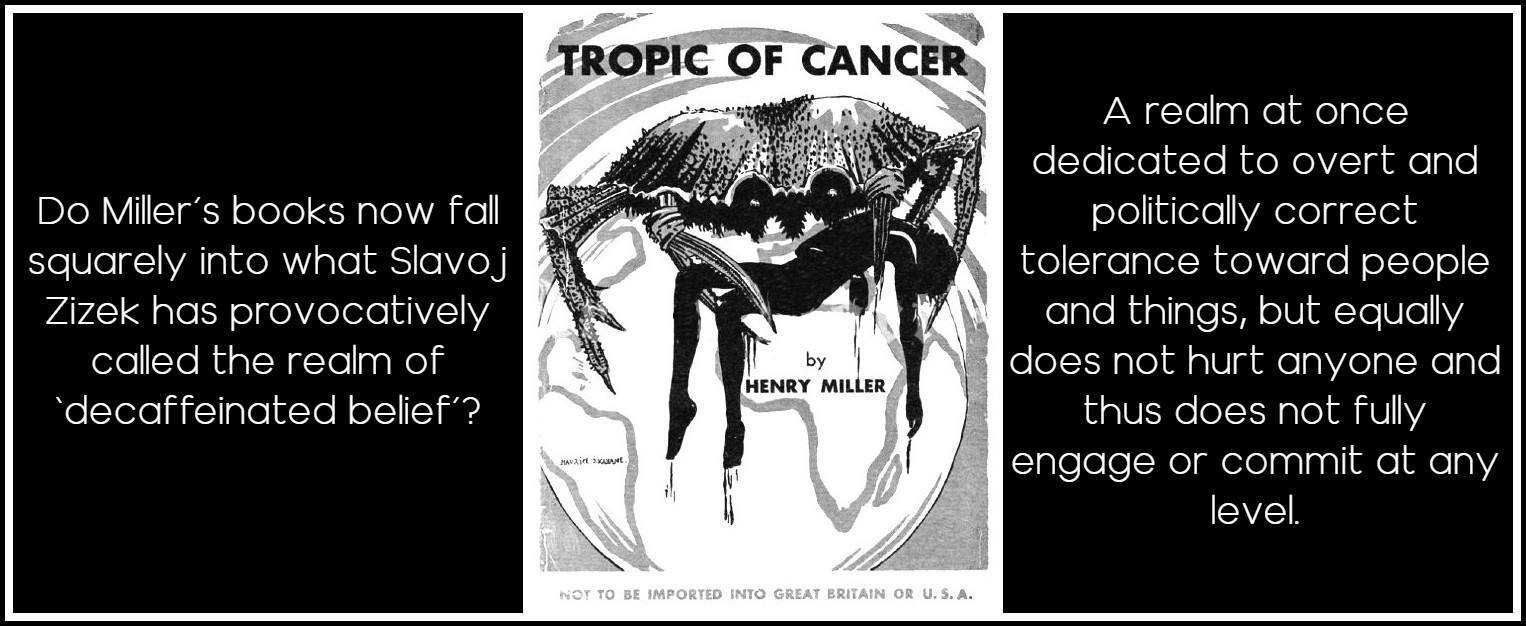

But it’s too late… In bringing Miller forth from the shadows, in allowing him to cross that boundary from the dark, fetid reaches of perversion and obscenity to the (en)lightened halls of normality, have we, the judging reader subjects, lost much of the promise Miller as a writer and an artist held? In short, do Miller’s books now fall squarely into what Slavoj Zizek has provocatively called the realm of ‘decaffeinated belief’? A realm at once dedicated to overt and politically correct tolerance toward people and things, but equally does not hurt anyone and thus does not fully engage or commit at any level.1 Miller’s proto-punk aesthetic, his ‘gob of spit in the face of Art’ could surely never be accused of not committing. Certainly, ‘a kick in the pants to God,’ is seemingly less of a provocation today. Indeed, for the legions who now consider themselves anywhere on the spectrum of (militant) atheism that ‘kick’ is simply sport.2 Are we therefore able to extrapolate anything from Miller’s work to counter and render problematic this cultural sway in which, ‘you can enjoy everything, BUT deprived of its substance which makes it dangerous’?3 Moreover, what responsibility or role does law have apropos the (re)caffeine-nation of Miller (to reverse and transform Zizek’s idea into an admittedly awkward linguistic construct)?

1 – Slavoj Zizek, ‘Passion in the Era of Decaffeinated Belief,’ The Symptom, 5, Winter 2004, http://www.lacan.com/passion.htm

2 – The citations are from Tropic of Cancer (New York: Grove Press, 1961) p. 2

3 – Zizek, ‘Passion in the Era of Decaffeinated Belief.’

Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, first edition cover (1934)

II. CAFFEINE AND LAW?

Far from conjuring the type of images recognizable from classic police dramas of overworked cops guzzling cup after cup of a questionable filtered brew, the connection being made here, for the purposes of quick clarification, is that sense of full-throttle alertness that caffeine provides tempered as it is by the fetters of asceticism, prohibition, and proscription. A sense of what it means to fully commit, ‘up to the hilt’ as Miller might have it, is the caffeine in Miller that needs to be sought out. We might even search in Miller for that same counterlegal representative much in the way that his character in Tropic of Cancer looked about his world with flaming eyes, searching amid the damp squibs for one that would ignite: There is only one thing that interests me vitally now, and that is the recording of all that which is omitted in books. Nobody, so far as I can see, is making use of those elements in the air which gives direction and motivation to our lives. Only the killers seem to be extracting from life some satisfactory measure of what they are putting into it. The age demands violence, but we are getting only abortive explosions.1

1 – Tropic of Cancer, p. 11; my emphasis

Photo: Christina Rumpf, Unsplash

The following discussion centers on the law, but not from a strictly doctrinal or positivist legal perspective; far from it. Rather, this essay will draw on those aspects born in the psychic space of the subject, as elucidated by psychoanalysis, which are in dialogue with the external socio-juridical structure called ‘law,’ and which strive to better understand affective and culturally engrained notions of obscenity. Henry Miller, as the essay will seek to demonstrate, occupies an ideal position in order to explore this, and the many questions which flow from it. And many do. There is no shortage of question marks here; but they do not denote a discussion that has stalled or is grasping for purchase on the sheer face of understanding. No, each of those marks is a fissure, a break in the tree line revealing another path. They are marks of pure contingency.

Freud’s psychoanalytic couch (Freud Museum London) | Lady Justice (Tingey Injury Law Firm, Unsplash)

III. THE JUSTIFIABLY OBSCENE?

If Zizek, after Jacques Lacan, is correct in his measure of contemporary cultural products of which literature is one—that is, a degree of liberal toleration premised upon (cultural) products now containing the agent of their own containment,1 for example, pleasure and containment bound up in a single easily consumable artifact—then where does this leave Miller, or rather his body of work? Is Miller’s work still vital in the twenty-first century precisely because within its dark recesses we may still find that which skews the agent of its own containment and bends it out of true; can his work be read from this point and still inspire through its heady blend of cosmic vulgarity; or does his work for the reader, writer, artist, or whosoever should come to it in the here-and-now, simply represent exotic dalliance with or sentimentality for a more parochial era? Indeed, there are many questions Miller and his work still kick up. In order to address some of them, this essay will revisit the moment when the juridical line or limit apropos Miller was (re)drawn during the obscenity cases heard across the United States, up to the Supreme Court, during the middle of the twentieth century: cases in which the complainants sought to reinforce a discourse of normality as much as one of decency under the rubric of ‘contemporary community standards,’ and which decried Miller’s work, among others, as obscene by virtue of it running counter to favored, legally mandated norms.

1 – Zizek, ‘Passion in the Era of Decaffeinated Belief.’

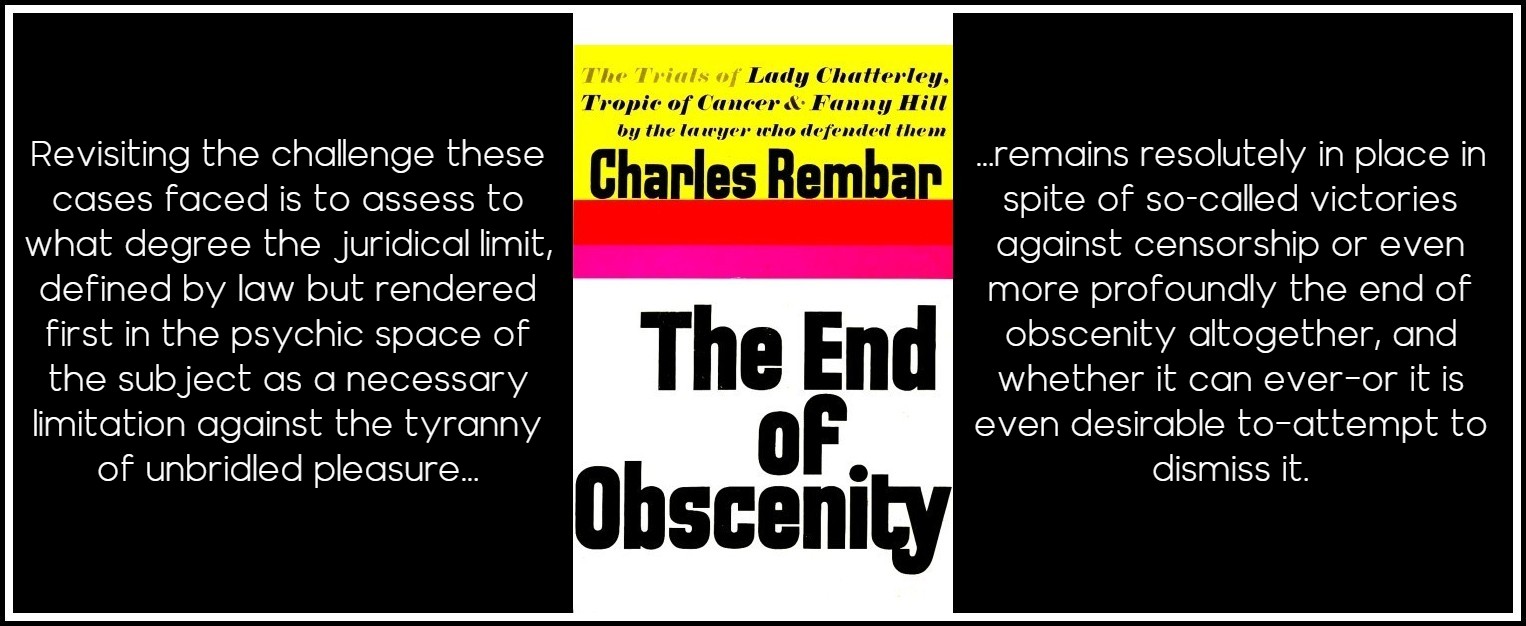

Jacques Lacan (photo: Jerry Bauer) | Henry Miller (photo: Arnold Newman) | Slavoj Zizek (photo: Roger Cremens)

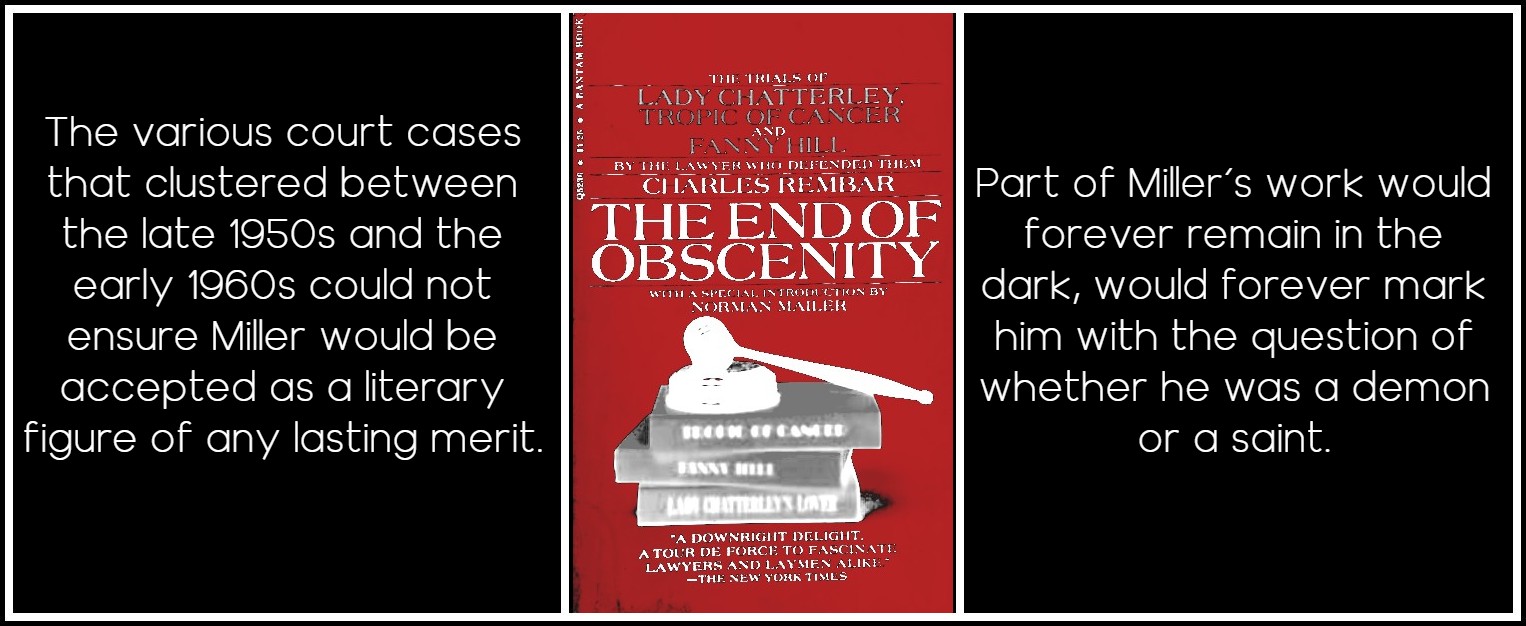

The series of landmark obscenity cases, which were bookended in the main relative to Miller by Roth v. United States (1957) and Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964), have during the last fifty to sixty years had an undeniable material effect upon public perceptions of media previously deemed obscene. As such some of them now also represent well-known ‘free-speech’ narratives in their own right, notably in opposition to the perceived erosion of First Amendment rights—having been made the subject of inter alia contemporary films, including The People vs Larry Flynt (1996) and Howl (2010). Revisiting the challenge these cases faced, and subsequently disposed of, however, is to assess to what degree the juridical limit, defined by law but rendered a priori in the psychic space of the subject as a necessary limitation against the tyranny of unbridled pleasure, remains resolutely in place in spite of so-called victories against censorship or even more profoundly the end of obscenity altogether,1 and whether it can ever or it is even desirable to attempt to dismiss it. In short, as the firebrand introduction to this essay proclaimed, in giving their seal of approval to Miller, the U.S. Supreme Court failed to recognize a certain value and importance inherent to the community of keeping Miller on the side of obscenity, and thus of ensuring that his passion was not too quickly exhausted for our benefit. Miller’s work could be rebanned, but in truth that misses the point. Rather, another aim of this essay is to understand the merits of writers and artists, such as Miller, who shine a light on the limit from beyond, so to speak, and as such serve to enrich the psychical fabric of the subjects who make up the community.

1 – This is the title of the book published by the lawyer who helped overturn the obscenity laws relating to literature in the United States during the mid-twentieth century. See Charles Rembar, The End of Obscenity: The Trials of Lady Chatterley, Tropic of Cancer and Fanny Hill (New York: Random House, 1968).

Charles Rembar, The End of Obscenity, hardback cover

We need(ed) Miller and others like him in this avant-garde form to remain obscene, even dangerous, in order to direct the rest of us toward a better understanding of obscenity. This is a somewhat trite statement but one nevertheless possessing a recognizable truth traceable to the foundations, at least, of Western philosophy and its relationship with art. As Iris Murdoch has suggested: Art breaks the grip of our own dull fantasy life and stirs us to the effort of true vision. Most of the time we fail to see the big wide real world at all because we are blinded by obsession, anxiety, envy, resentment, fear. Great art is liberating, it enables us to see and take pleasure in what is not ourselves.1 Therefore, to invite a broader discussion on the merits of the obscene and its operatives, it may well be asked whether or not we need tension between art and law in order to approach an understanding of obscenity. The suggestion being made here is that we most certainly do. But are we as a community still prone to an acceptable and healthy degree of shock, which is both transformative and redefining?

1 – Iris Murdoch, Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature, ed. Peter Conradi (New York: Penguin, 1999) p. 14

Photo: Darius Bashar, Unsplash

Law alone has failed in maintaining that tension. There is a degree even of which it can be said that the law is too self-aware, too quick to agree or satisfy fleeting popular mandates. Therefore, the last place we should seek definitions of obscenity is the law. Perhaps that is why the closest the community can now hope to get to the obscene are terrorist acts. This is not to condone such acts. But Miller’s manifestation in Tropic of Cancer would and does maintain something not dissimilar; and how much has changed since those words, that world, was conceived, which makes his ideas more relevant or vital today: For a hundred years or more the world, our world, has been dying. And not one man, in these last hundred years or so, has been crazy enough to put a bomb up the asshole of creation and set it off. The world is rotting away, dying piecemeal. But it needs the coup de grâce, it needs to be blown to smithereens.1

1 – Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, p. 27

Photo: Unsplash

In the twenty-first-century U.S., a ‘workable’ definition of obscenity still turns on the tripartite test established in Miller v. California (1973) (no relation to Henry), although Burger CJ in that case recognized the concern articulated by his colleague Mr. Justice Harlan in an earlier case of the ‘intractable obscenity problem,’1 which in essence turned and continues to turn upon whether or not a piece of work could or should be deemed pornographic relative to the impact that it has upon the moral fabric of the community. Something else is in evidence here; a certain anarchical spirit which Miller brings to the world. Rather than couching it in terms of anarchy, however, it is important to confront the notion of an intractable obscenity and see where it takes us. Hence, it is Miller as obscene other of the law which is favored and proposed. In short, we need the obscene other of the law in all its artistic glory, as the two polarities, if indeed that is a suitable term, to fundamentally support one another. As Zizek suggests in relation to this obscene other, it is, ‘the unacknowledgeable ‘spectral,’ fantasmatic secret history that effectively sustains the explicit symbolic tradition, but has to remain foreclosed if it is to be operative’.2 It is the issue of revealing the foreclosed, the confession of the otherwise unsaid, which marks a primary concern. Miller enacts this reveal, and does so with gusto, from his earliest work.

1 – Clearly the ‘intractable obscenity problem’ remains intractable as much across the media platforms of the twenty-first century, namely the Internet, as it did throughout the twentieth century in books and later videos, not to mention artworks, painting, sculpture, and so on. For example, see Matthew Dawson, ‘The Intractable Obscenity Problem 2.0: The Emerging Circuit Split over the Constitutionality of “Local Community Standards” Online,’ Catholic University Law Review 60 (2010-2011): 719-748.

2 – Slavoj Zizek, ‘The Act and Its Vicissitudes,’ The Symptom, 6 (2005). http://www.lacan.com/symptom6_articles/zizek.html

Slavoj Zizek | Photo: Roger Cremens

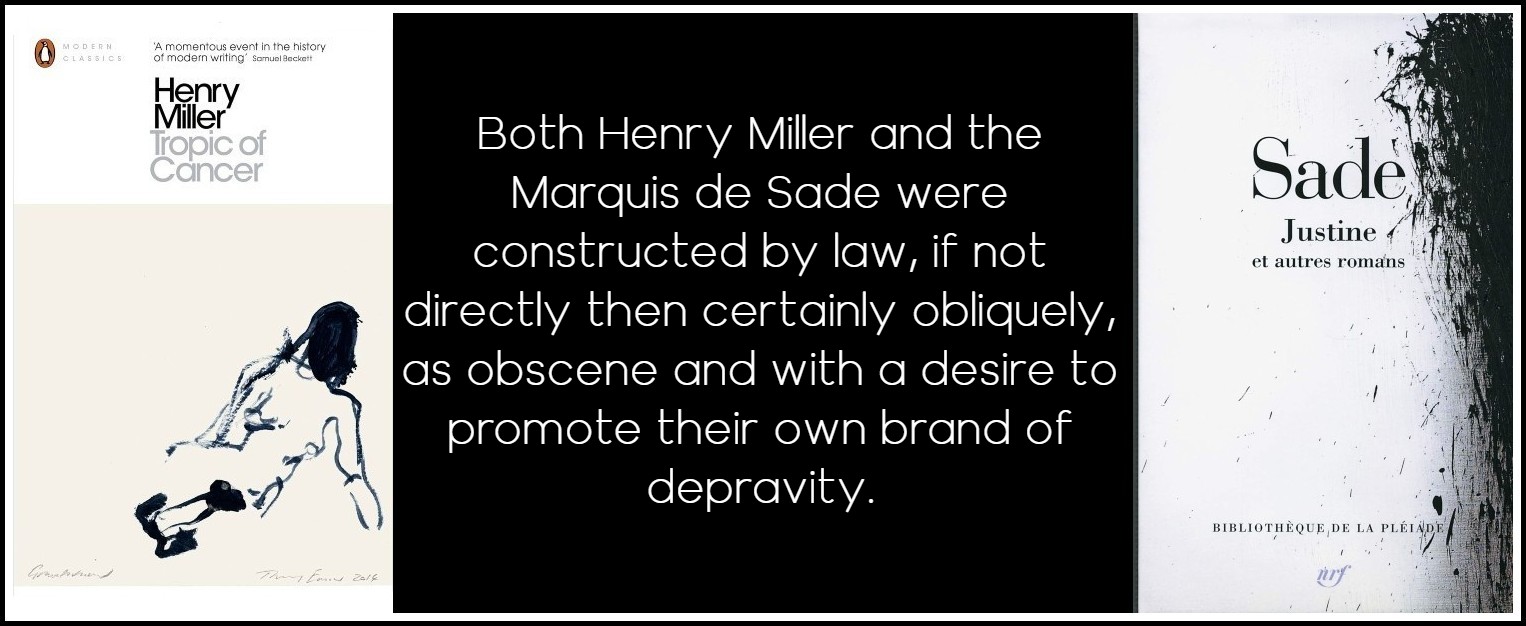

IV. WELCOME TO THE LIMIT

Obscenity as a form of corruption of high moral values has a long history in society and thus in law. Indeed, to outline societal confrontation with ideas of obscenity (née pornography) is well beyond the scope of this essay, even by focusing on the United States alone. There are, however, clear parallels that can be drawn relative to the form of juridical demarcation suggested above across the recent and not so recent history of Western legal thought, between Miller and the Marquis de Sade for example. After all, both were constructed by law, if not directly then certainly obliquely, as obscene and with a desire to promote their own brand of depravity. A notable example of juridical common ground between Miller and Sade resides in them as obscene other to the symbolic construct of decency. While Miller himself reportedly retreated from the works of Sade, and others find a substantive comparison between the two ‘frivolous,’ such a comparison nonetheless provides a useful point of reference beyond the legal for highlighting what is perhaps best referred to as the limit, and which inaugurates this obscene other of the law.

Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer | Marquis de Sade, Justine

Indeed, in his short story, ‘The Mystified Magistrate’ Sade enacts a scene in which the obscene other to the law confronts the law directly, making its presence felt literally on the corpus juris: Without further ado the poor judge was taken and placed facedown on a narrow bench, to which he was securely tied from head to foot. The four wanton spirits each took a leather thong five feet long and, striking up a cadence among them, proceeded to let the lashes fall with all the strength their arms could muster, on every square inch of poor Fontanis’s bare body. In law, it is entirely possible, in a doctrinal sense at least, to reverse and unpick the authority that paved the way from one state of legal being to the next—from the obscene to the legally decent for example, as demonstrated by Miller. At least that is the level of authority the law wishes for itself and in turn demands of us. Once a judge’s opinion overturns what is obscene and is recorded as such, and all the more so once that opinion forms the backbone of precedence and thus shapes the law, greater distance opens up from the moment when a writer was obscene to when that nomination was lifted. Yet such outwardly clear and precise delineations of states of being are of course deceptive, so entangled is the law with culture—and is it not so much harder to reverse the direction of cultural fancies and the prejudices of individuals?

Charles Rembar, The End of Obscenity, updated hardback cover

There is therefore a problem with casting Miller out or plunging him from whence he came unto the depths of depravity where he may live eternally as, in his own self-reflective words, ‘a dirty saint,’ and wipe the slate clean so to speak.1. Miller’s ascent to a degree of community acceptance and thus also the decaffeinated realm cannot be unremembered and as such cannot be undone. To be sure, communities collectively can and often do (temporarily) forget the works and lives of many writers before revisiting them or have them reemerge in unexpected and unanticipated ways. Writers, indeed any artists, are after all subject to the vagaries of fashion: a cultural centerpiece one minute, a denizen of the bargain bin the next. But this toing and froing from the depths of the cultural archive, which attaches to so much human endeavor, does not turn the clock back and cannot undo the initial casuistry of an artist’s work. ‘It’s out there!’ as we so often hear in the troubled contemporary parlance of information and big data dissemination, rife as it is in our post-X-Files, WikiLeaks world. Similarly, we cannot in the here and now say therefore, with regards to Miller, that the genie has not been set free.

1 – Henry Miller, Reflections, edited by Tiwnka Thiebaud (Santa Barbara: Capra Press, 1981)

Man Ray, Reproduction of a photographic portrait of Henry Miller, 1960

Miller’s journey from darkness into light and from obscenity to a relative ideal of mainstream decency was conducted largely (and formally) by the hands of the law, but against a highly charged affective backdrop. Mary Kellie Munsil suggests via the reasoning of Edward S. Silver, the district attorney who wrote Brooklyn’s complaint against Miller and his publisher Grove Press following the release of Tropic of Cancer in the United States: ‘For Silver the danger of the book lies in its creation of unacceptable mental and emotional states in the reader.’1 Did the law’s operatives, albeit working for a self-proclaimed community good equally exemplified and underwritten by certain conservatism, not fail in their aims however? Well, yes and no. On the facts Miller et al. tipped a delicate balance thereby eschewing the chains restricting the artistic mind. But as Roland Barthes has demonstrated in his work,2 the author’s (the artist’s) perspective is but one amid a matrix which inform the artwork as such in the wider field of perception: We know that a text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the ‘message’ of the Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture.3

1 – Mary Kellie Munsil, ‘The Body in the Prison-house of Language: Henry Miller, Pornography and Feminism,’ Critical Essays on Henry Miller, ed. Ronald Gottesman (New York: G.K. Hall, 1992) p. 286

2 – Roland Barthes, ‘The Death of the Author,’ Image-Music-Text, translated by Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977) pp. 142-148

3 – Barthes, ‘The Death of the Author,’ 146

E.R. Hutchinson, Tropic of Cancer on Trial, cover | Barney Rosset, Grove Press, 1968

Thus, the groundswell of cases that played out during the mid-twentieth century redefined the limit and shifted it, seemingly, to a new libertarian location in which Miller was welcomed. Yet, this new locus, as time has indicated, would prove not to be defined relative to traditional notions of community standards—that is, so much by external, objective notions of obscenity—but rather by a transference of that regulatory agency back on to the subject, be they consumer, reader, and so on. As a result, inaugurating a new era of asceticism contrived as something wholly freeing for the subject. In order to prevent or counteract ‘lecherous thoughts and desires’ in those that came into contact with Miller’s books, Silver along with other operatives of the law attempted to reaffirm, perhaps even reconstitute, the line of juridical reasoning traceable to Scots judge Sir James Alexander Edmund Cockburn’s definition of obscenity laid down in the case Regina v. Hicklin (1868); a baton picked up soon after in the United States by the Comstock Act (or Law) 1873, which as an ‘Act of the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use’ sought to deal with the unpalatable issue of obscene material by severing the postal supply lines, which ultimately kept those hungry for it fed.

Sorting mail in a railway carriage, 1930s | Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer & Tropic of Capricorn

It was reasoning, one presumes, Silver hoped to rely on in order to maintain the status quo—that is, a community standard enforced, perhaps less by the fierce moral notions of ‘Comstockery’ than by a resolute adherence to the dictates of the law. Those that had supposedly succumbed to the corruptible influence of Miller’s ideas, of his ‘manifesto,’ would fall foul of Silver’s strict legal limit, thus opening themselves first to chastisement at the hands of ‘the community’ before subsequent return to its bosom via the suppression or rather repression of their prurient thoughts under the name of rehabilitation. It was doubtless, however, a double bind for Silver: in order to achieve the (continued) suppression of obscene material, which in actuality many people either already knew about or were already engaging with—Miller’s work was both lauded and available in Europe and thus had already made its way via smugglers and fans to the North American shores during this time—it was necessary to expose and render conscious the underbelly, the very kernel of obscenity that signaled his complaint. From a Foucauldian perspective this may signal a form of power that serves to generate the very excess it would censor. For Zizek, Foucault does not go far enough, as he suggests: ‘What Foucault’s notion misses is the way in which censorship not only affects the status of the marginal or subversive force that the power discourse endeavours to dominate but, at an even more radical level, splits the power discourse itself from within.’1

1 – Slavoj Zizek, The Plague of Fantasies (London: Verso, 2008) p. 31

Michel Foucault | Slavoj Zizek

How was this split evidenced in terms of Silver’s case against Miller? The form of reveal alone, both exposing and exemplifying the level of obscenity he found so disconcerting, must have been troublesome enough for Silver. But perhaps, for the man who stated with resolve that there was a duty incumbent upon the people of America to grasp the importance of the administration of criminal law in their country, that it was also necessary for Silver to expose the weakness in the (criminal) laws he held in such high regard is the more notable and compelling thing. That was his radical splitting of the power discourse from within.

Photo: Nick Fancher, Unsplash | Faruk Tokluoglu, Unsplash | Composite: RJ

Is this not also an interesting, further inversion of Zizek’s notion of a product containing the agency of its own containment?—one which clearly demonstrates that censorship of obscene publications as such has never gone away, but has been marked by transference of censorial agency. Rather than an emphasis on the self-contained, internal agency working tirelessly against the perils of prurience as we might see today in a post-obscene world—for example, the sex shops once veiled as to their contents from the street while their presence is advertised in lurid, bright neon; or the pornographic magazines, their covers veiled by opaque plastic, once present but just out of reach on the top shelf of the magazine rack—there roamed from town to town externalized agents, picking off obscene materials one by one, their only desire/reward being inter alia the succor of organized religion (Comstock), or the maintenance of the legal order (Silver). Clearly, the internalized limit within each subject, which triggers, with varying degrees of success, the ability to personally gauge levels of obscenity, did not suddenly appear in order to counteract the change in the law. After all, Freud had outlined his notion of the superego—broadly speaking, as an updated notion of conscience befitting the scientific age—many years prior to the obscenity cases, and conscience as a register of individual ethical values had been prevalent far longer still. Therefore, in considering the limit between law and decency and its obscene other as a phenomenon simpliciter, it is necessary to consider its relationship to agency, and more specifically to those parties as agents who stood to gain, so to speak, from the definitive internalization of the limit and the subsequent corollary of a laissez faire approach on the part of the law. While the question of who ‘stood to gain’ injects a sense of the conspiratorial that will not be entertained here, the notion of agency does once again return to Zizek’s containment thesis.

Photo: Maxence Pira, Unsplash

V. THE LIMIT IN LAW AND IN THE PSYCHE

Law in this context simply represents limit: nothing more, nothing less. Imagined as a slider on a scale of ‘decency,’ it is those with a firm grip on the reins of power, the guardians of community standards, who set the (symbolic) limit in place. But it is important to contrast it with the parallel sense of the limit at work here, which is the psychoanalytical determination outlined by Freud relative to the Pleasure Principle. In other words, the law is never just ‘law,’ but is, I argue, tied inexorably to unconscious psychical evaluations relative to the subject’s approach toward the thing—the object of the subject’s desire. The point being that the law relative to obscenity apes the actions of the limit known as the Pleasure Principle inasmuch as for the subject to surpass it, to go beyond the limit (the law) as such, invites unpleasure psychically, which in terms of community standards manifests as anxiety and disavowal at the level of the symbolic law.

Photos: Planet Volumes, Unsplash | Bikesh Deshar, Unsplash

Obscenity, like many other legal terms and phrases, escapes singular or rather settled definition per se and therefore invites contestation. But, as Charles Rembar, the erstwhile defender of free speech against this limit as such during the mid-twentieth century on behalf of inter alia Miller’s publisher at the time, Grove Press, proclaimed in a manner peculiarly sympathetic in tone to the statements of his counterpart Edward Silver: ‘Laws are hard to apply and enforce; this does mean we should not have them’. Comprised of both action and idea, obscenity is a regulated limit we, either as individuals or as a community, dare to cross. Instead we leave it, necessarily, to the artist. It is also an exceedingly affected or affective line, or at least has been in recent history as the question of obscenity has been raised time and again, with each iteration seeking to limit different media—first literature, then theater, then film ad infinitum. As Rembar maintained in the late 1970s with a degree of hindsight as to his part in the obscenity trials: ‘Obscene’ for legal purposes should be discarded altogether. It carries an impossible burden of passionate conviction from both sides of the question. And it diverts attention from real issues. Quite what Rembar’s ‘real issues’ are and whether they are any easier for a community to define is open to question, although at a certain level those issues are guaranteed to represent a knot of conflicting desires. Nevertheless, the limit (or ‘question’ in Rembar’s terms) at first appearance simply separates the obscene from the decent based on what passes for each of those nominations at any one period in time. But it is not a limit defined solely or simply by the binary divisions it inaugurates.

Photo: Andrej Lišakov, Unsplash

Rather, by rendering the limit and by extension the motivations of those that control it as a regulatory mechanism in, for example, the vein of Freud’s superego is to color it more perverse than a mere dividing line. Instead, it is revealed as a limit that bids those that approach to cross, before hurriedly gathering the dark forces of guilt to condemn their actions. In that sense it is a psychical feedback loop as much as a legal prohibition which ensures our insatiable desire remains at a certain biting point. This is the psychical dimension that cannot be easily uncoupled from the juridical. To return to a couple of allusions made previously: this bidding of the superego transliterates into the neon sign of the sex shop, or the opaque plastic veil of the pornographic magazine. There is a sense of temptation here in the theological mold. But, equally, there is a sign of healthy allegiance to the law of our own being, of our own desire. An allegiance analogous to that conjured by Miller as he continued to make sense of the Parisian world he moved through: I found God, but he is insufficient. I am spiritually dead. Physically I am alive. Morally I am free. The world which I have departed is a menagerie. The dawn is breaking on a new world, a jungle world in which the lean spirits roam with sharp claws. If I am a hyena I am a lean and hungry one: I go forth to fatten myself.1

1 – Tropic of Cancer, p. 103

The Limit: Desire and Guilt | Photos: Anne Nygard, Unsplash |Beyza Yurtkuran, Unsplash

VI. MILLER’S CROSSING

It was the line of judicial reasoning that ultimately ended with the decision in Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964), which to all intents and purposes clothed Miller in the acceptable and protective cloth of symbolic legal decency. In that sense Miller crossed the limit from obscenity to decency, and with it his fortunes, largely financial in nature, were also transformed. The legal decision also transformed his fortunes to the extent that he was able to openly enjoy international recognition as an author and artist. Moreover, it even became relatively safe for the mainstream media to court Miller for the enthusiastic titillation of their audiences. Miller surmounted the heady and treacherous heights of cultural savoir faire to become a popular icon, albeit as the reluctant ‘king of smut.’1 But becoming known or better known, infamous or popular even, is not the same as becoming accepted as such and Miller only remained a liminal figure as far as the mainstream and the regulated standards of the community was concerned, irrespective of any official rubber stamping of his acceptability. Clearly, the period following Miller’s legal acceptance was offset to a certain degree by the failure of community standards to keep in step with the changes. And the gap between the two was ripe for exploitation from a number of angles. Perhaps one of the better known being Miller’s Playboy interview shortly after the Supreme Court ruling, in which the interviewer and Miller’s friend, Bernard Wolfe, playfully suggested that having been stamped with Court’s seal of approval, Miller was now ‘socially acceptable among all but the ladies’ auxiliary tea societies.’2

1 – Mary V. Dearborn, The Happiest Man Alive: A Biography of Henry Miller, (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), p. 279

2 – Bernard Wolfe, ‘Playboy Interview: Henry Miller,’ Playboy September 1964, p. 78

Playboy, September 1964 | Henry Miller

Miller, rendered unobscene, fissured so-called ‘standards’ and exposed the tender marrow within, which would not invite plaudits from certain conservative factions, namely tea societies. The Supreme Court ruling had, to some degree and in Miller’s own words, brought down barriers and shattered ‘the wretched molds in which we’re fixed.’1 But as this essay has sought to illustrate, the general optimism of Miller’s declaration was overstated. The various court cases that clustered between the late 1950s and the early 1960s could not ensure Miller would be accepted as a literary figure of any lasting merit—an idea he fleshed out in stark contrast to a degree of entitlement he felt toward an award of the Nobel Prize.2 Rather, those cases sought only to deal with the limit of what was deemed acceptable and decent as opposed to obscene and depraved in the eyes of the law. In other words, part of Miller’s work would forever remain in the dark; would forever mark him with the question of whether he was a demon or a saint.3

1 – Wolfe, ‘Playboy Interview: Henry Miller,’ Playboy September 1964, p. 77

2 – Henry Miller, Reflections, p. 112

3 – Ibid. p. 113

Charles Rembar, The End of Obscenity, Bantam paperback cover (colorized)

While Miller may have been given the Court’s seal of approval, does a part of him remain beyond the limit? What use is there to the cultural landscape of elements if not whole sections of Miller’s oeuvre remaining below this conscious Plimsoll line? It’s as if the Supreme Court ruling opened a door to decency through which Miller passed, but that same door slammed shut too soon severing his arm (that element of Miller as a metaphor for his obscenity) and leaving it on the other side where it continued working—an image one cannot help but evoke in full consideration of Miller’s great friendship and respect for the one-armed writer Blaise Cendrars, creator of his own obscene and monstrous figures, including the perverse Moravagine. Is this element of Miller held back in the name of obscenity that which suggests acceptability at a deeply unconscious level of desire, but that which must equally remain unacknowledgeable (unconscious) in order to ensure the continuation of a more powerful and explicit symbolic tradition engendered by all that is acceptable? In other words, this line of high-profile cases engaged only at the level of explicit symbolism, all the while leaving untouched the otherwise unconscious world of fantastical desire that represents the heart and soul of Miller’s work.

Ansel Adams, Henry Miller, 1959

To evoke Jacques Lacan at this point: correlation may be found between the hypothetical example of Miller’s severed limb and Lacan’s notion of the Real. Notwithstanding, Lacan oversaw a number of iterations of the Real during the course of his life, and while developing his many concepts and their interrelatedness, there remains a continuous sense throughout that the Real is that which escapes symbolization and cuts through the imagination. Further, Miller’s severed limb is analogous to the Real because both represent a semblance of pure desire. To imagine the severed, disembodied limb furiously scribbling its chaotic and obscene reflections of the world, its hymn to vast expansive unknowns, is to imagine a thing more Miller than Miller. This is Miller residing beyond Freud’s pleasure principle; beyond the limit, enraptured in the throes of the death drive. In this sense Miller ceases to be obscene, in any ordinary or linear understanding of the term, and emerges, even while considered acceptable, as something of an extraordinary and traumatic intervention in the world of the symbolic—that is, the world in which the law holds sway and grants Miller approval. We cling to Miller’s work precisely because he functions to disrupt the everyday and the parochial. As Zizek, again following Lacan, contends: The Real, at its most radical, has to be totally de-substantialized. It is not an external thing that resists being caught in the symbolic network, but the fissure within the symbolic network itself.1

1 – Slavoj Zizek, How to Read Lacan (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007) p.72

Jacques Lacan | Slavoj Zizek

It is precisely this latter concept that needs to be grasped relative to the continued importance of Miller’s work. It reveals that small but vital space between the conscious assertions of the symbolic law (Miller as saint) and the unconscious desires of the community of subjects (Miller as demon). More now than ever, the agency splitting the power from within, where once it resided in agents such as Silver, now resides in each and every subject as we (as community) traverse the cultural landscape, often unsure at which point we stray too close to the edge, to the psychical limit saving us from ourselves.

Ansel Adams, Henry Miller, 1959 (colorized)

VII. A CONCLUSION

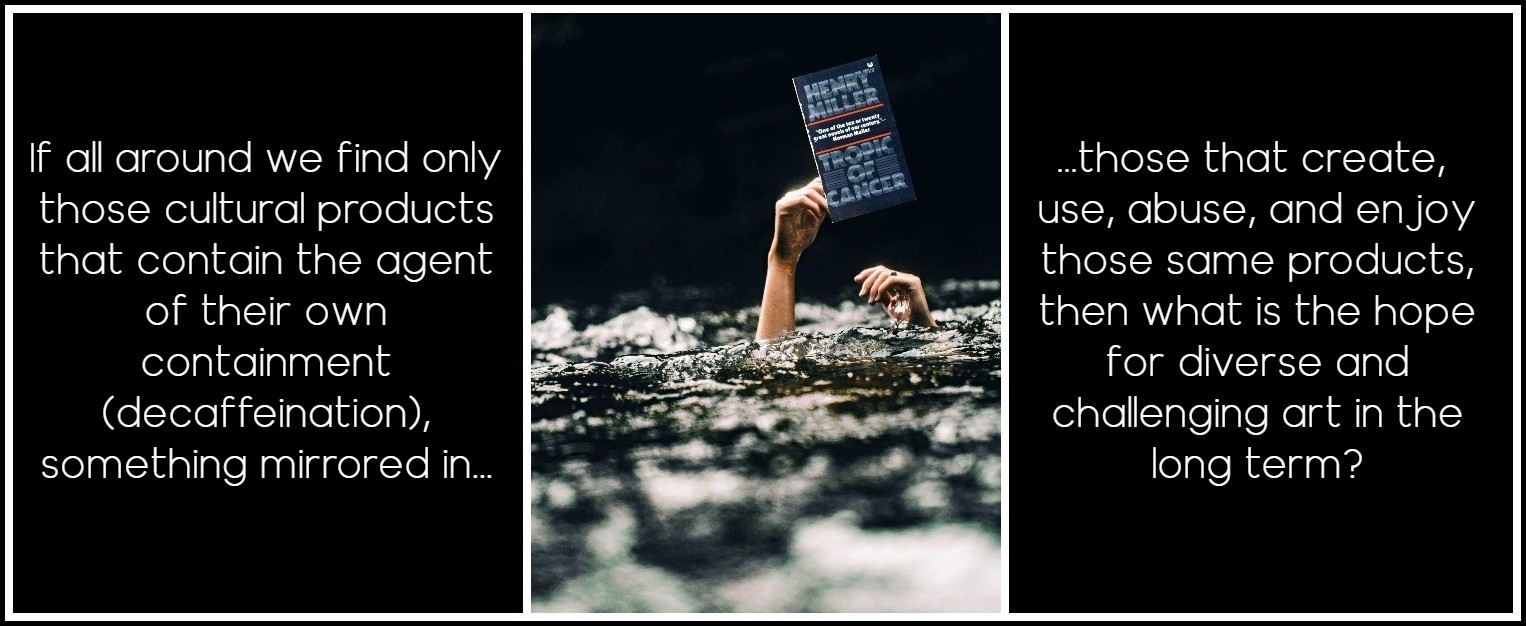

Miller cannot be returned to the position he was in prior to Jacobellis, but it is possible to approach his work now and for future generations with the knowledge that parts of it continue to reside in the beyond of the limit as obscene other. This may sound like an argument romanticizing a lost past of strict moral virtue, but I assure you that is not the intention. We need obscene others, or perhaps an ‘Enemy’ to couch it the terms Miller reserved for Wyndham Lewis.1. That is the thrust of the argument here and one that has hopefully been made plain. There can be no doubt that contemporary examples exist and indeed thrive in their own way; examples that even ape Miller such as Eric Miles Williamson.2 Perhaps the concern underlying the argument therefore is less about the continued existence of artists such as Miller, and more about the landscape in which are propagated the ideas such artists hope to bring to the fore. After all, if all around we find only those cultural products that contain the agent of their own containment (decaffeination), something mirrored in those that create, use, abuse, and enjoy those same products, then what is the hope for diverse and challenging art in the long term?

1 – Henry Miller, The Cosmological Eye (Norfolk: New Directions, 1939) p. 188

2 – Eric Miles Williamson, Welcome to Oakland (Hyattsville: Raw Dog Screaming Press, 2009)

Photo: Blake Cheek, Unsplash | Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, cover | Composite: RJ

Moreover, not everyone can do what Miller and his like have done, namely lead us, the community, to the limit, sometimes to its very edge, even challenging us to take that additional fateful step. The landscape for creativity is suggestively open and wide in the contemporary era and technologies have cemented that reality. But does that in itself not dilute the impact, and more worryingly detract from voices like Miller’s? Could someone, an artist, a writer, or a musician, in the vein of Miller make his voice heard today? In closing, it seems only appropriate to leave the final word to Miller himself—a summing up encompassing both the need for the obscene other and its manifestation, its very encroachment, into the everyday reality of the community and the subjects who comprise it: The day face of the world is unbearable, it is perhaps true. But this mask which we wear, through which we look at the world of reality, who has clapped it on us? Have we not grown it ourselves? The mask is inevitable: we cannot meet the world with naked skins. We move within the grooves, formerly taboos, now conventions. Are we to throw away the mask, the lying face of the world? Could we, even if we choose? It seems to me that only the lunatic is capable of making such a gesture—and at what a price! Instead of the conventional but flexible groove, which irks more or less, he adopts the obsessional mould which clamps and imprisons. He has completely lost contact with reality, we say of the insane man. But has he liberated himself? Which is the prison—reality or anarchy? Who is the gaoler?1

1 – The Cosmological Eye, p. 192

Photo: Philipp Pilz, Unsplash

ROB HERIAN: TWO BOOKS AND A CHAPTER

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments