Part 4 of 4

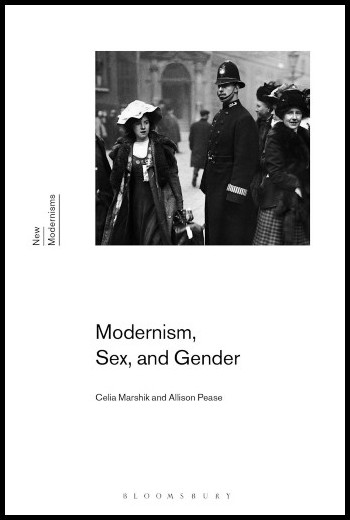

JAMES JOYCE AND AUBREY BEARDSLEY: AESTHETICS OF OBSCENITY

Allison Pease

Posted by kind permission of Allison Pease, Professor of English, Provost and Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York.

From Allison Pease, Modernism, Mass Culture, and the Aesthetics of Obscenity (Cambridge University Press, 2000) pages 115-135

THIS IS PART 4 OF 4 PARTS. READ PART 1 FIRST.

James Joyce, c. 1935 (Photo: Boris Lipnitzki) | Aubrey Beardsley, 1890 (Photo: Frederick Hollyer)

VII. GENDER-BENDING AND HOMOEROTICS

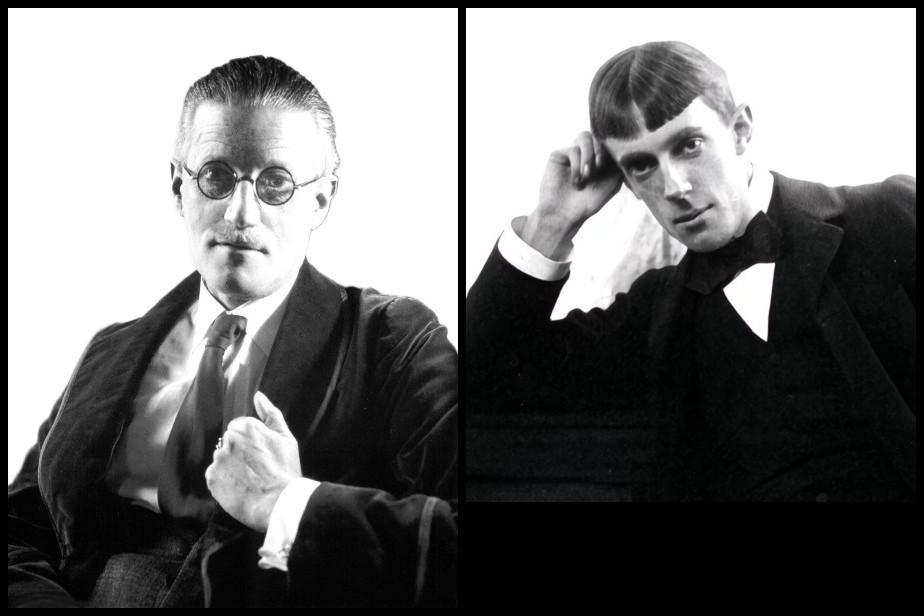

In a continuation of the masochistic theme, ‘Circe’ plays out the social implications of the classed body in a gender-bending fantasy scenario that provides acerbic social commentary. In Bloom’s submission to Bella/o (a parody of Sacher-Masoch), his transformation from nun to woman, and from woman to prostitute, makes obvious the hegemonic cultural association between the working classes and the sexual body. The prostitute is the sexualized, working-class body. What’s more, her body becomes the object of capitalist penetration: whoever will pay may subject it to his will. When Bloom becomes a whore in the masochistic fantasy, the tone shifts from the playful subjection of masochistic fantasy to the tough whore-house commercialism of Bello: My boys will be no end charmed to see you so ladylike, the colonel, above all. When they come here the night before the wedding to fondle my new attraction in gilded heels. First, I’ll have a go at you myself. A man I know on the turf named Charles Alberta Marsh (I was in bed with him just now and another gentleman out of the Hanaper and Petty Bag office) is on the lookout for a maid of all work at a short knock. Swell the bust. Smile. Droop shoulders. What offers? (He points.) For that lot trained by owner to fetch and carry, basket in mouth. (He bares his arm and plunges it elbowdeep in Bloom’s vulva.) There’s fine depth for you! What boys? That give you a hardon? (He shoves his arm in a bidder’s face.) Here, wet the deck and wipe it round! The association of the prostitute’s body with an animal’s is made clear not just in the above quote where Bloom’s fee is compared to a dog’s, but several lines later where Bello brands his initial C into his rump, marking possession and capital interest. The prostitute’s body marks the intersection of the working-class body and the sexual body.

Egon Schiele, Prostitute, 1912

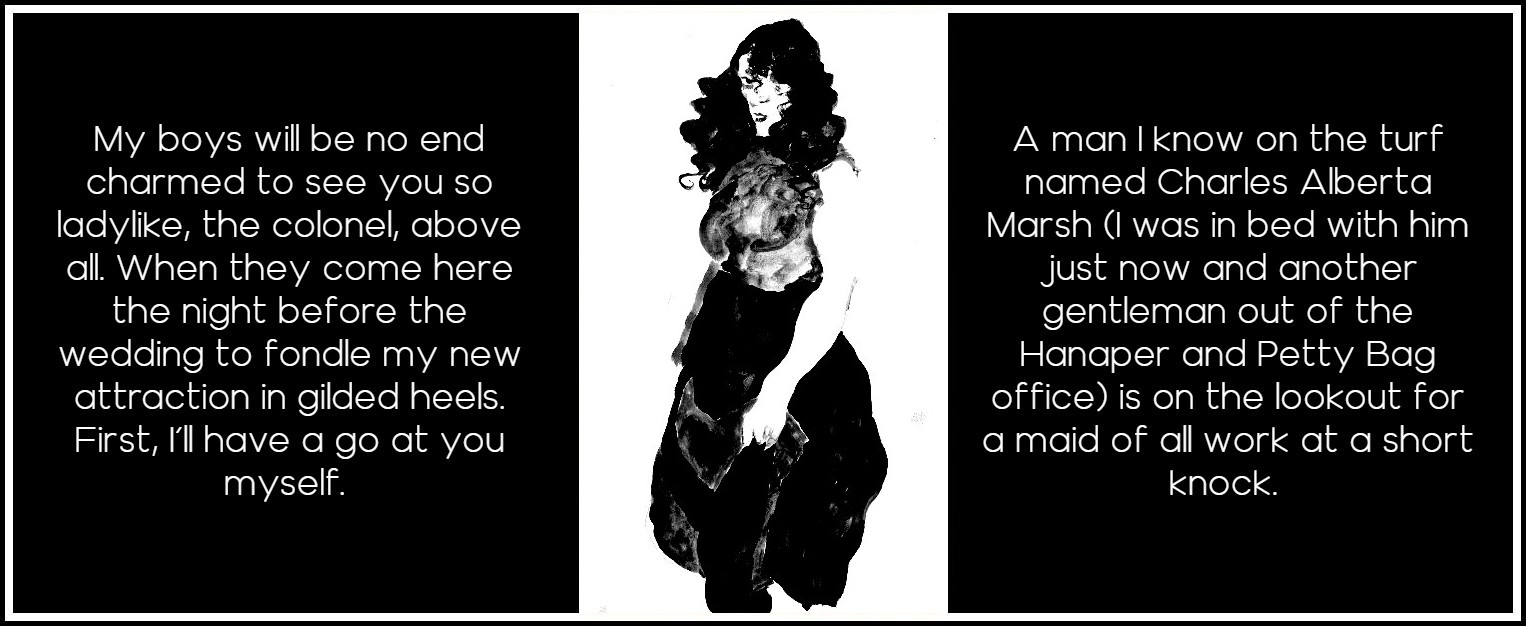

If the body of the prostitute was an accepted sexualized body, probably the least accepted of sexual bodies at the turn of the century was the homoerotic one, unless, that is, it formed part of a male fantasy about female eroticism. Beardsley’s works are rife with images of homoeroticism and gender-bending, but as in most of his drawings, he is able to get past censorship of such representations by using bawdy symbology to complete his indeterminate inferences, and by presenting such inferences in a high-cultural surrounding. An interesting example of this is his cover design for The Savoy, no. 2. In the cover design, two women are shown hats by a midget salesman. Hats, hat-boxes, and clocks were emblematic in eighteenth-century illustrative tradition of female genitalia; they continued to signify such things in the music hall of the early nineteenth century. The drawing is filled with hats, hat-boxes, and clocks. The bed at right sits unmade and the inference is clear that the two women have recently left it. In this home where the portrait hanging on the wall is of a woman, the man’s diminutive stature suggests that the female lovers have no place for a full-grown male in their bedroom.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Savoy No. 2, 1896

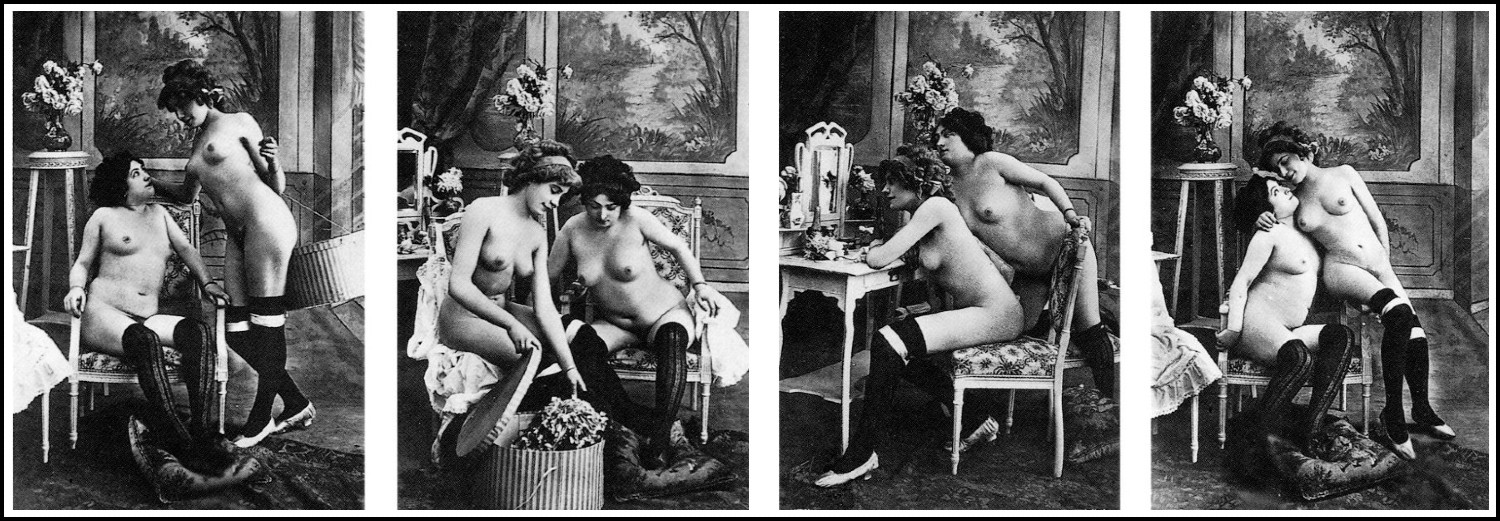

Though all of the inferences in this picture are subtle and an observer not acquainted with the slang might see in the drawing two ladies of fashion picking out a hat, a photographic sequence of erotic postcards taken around 1910 makes the homoeroticism of women, hats, and hatboxes clear. In this series a nude woman gives a hat in a hatbox to another nude woman. Gazing into a mirror in a moment of self-reflexive sexual knowledge, the two then go on to gaze into one another’s eyes in an acknowledgment of their shared sexual knowledge. Such a photo sequence exposes the latent meaning of the Beardsley drawing, and equally suggests his dependence on the pornographic tradition to complete his meaning. In as much as he draws on pornography, however, he also depends on a vast bourgeois ignorance of the trope to keep his intentions more vaguely suggestive than overt.

Photos: Anonymous. From 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839-1939 (Uwe Scheid Collection, Taschen)

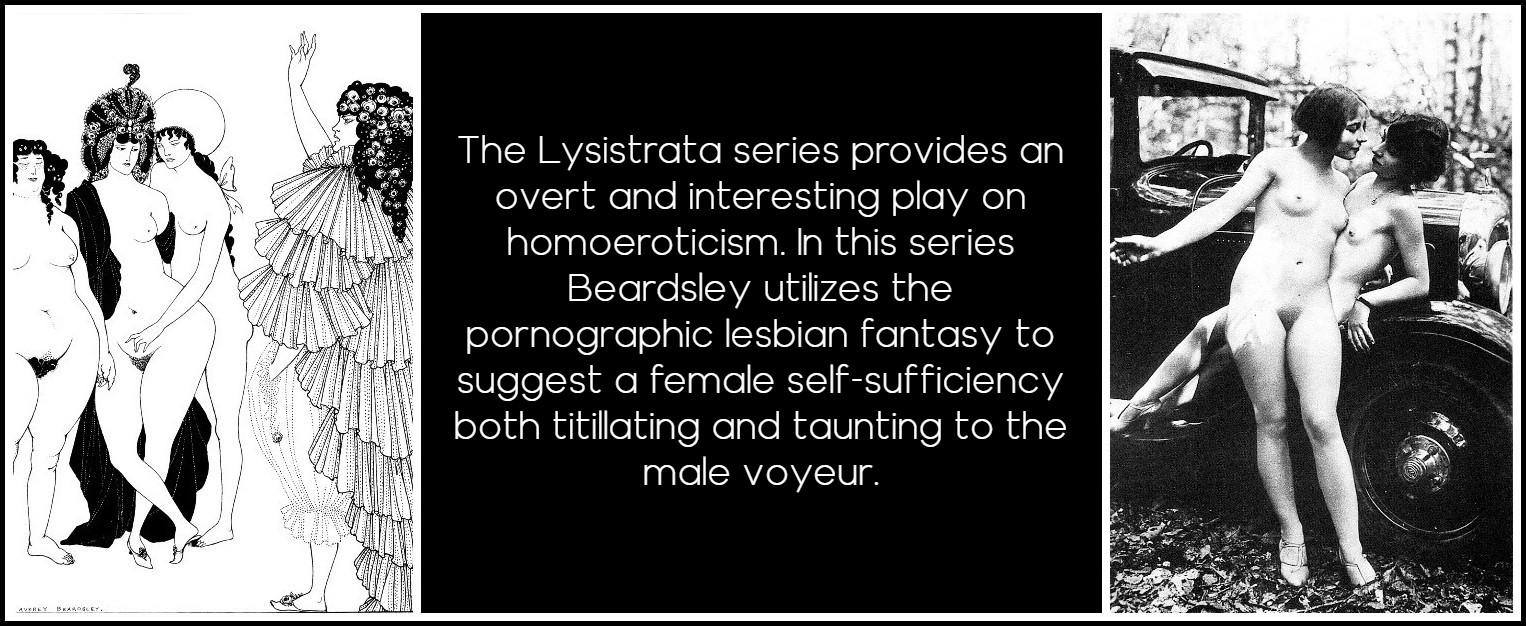

The Lysistrata series provides an overt and interesting play on homoeroticism. In this series Beardsley utilizes the pornographic lesbian fantasy to suggest a female self-sufficiency both titillating and taunting to the male voyeur. Lysistrata Haranguing the Athenian Women, for instance, plays upon the multitude of erotic photographs featuring nude women in sexual flirtation. There is little to differentiate Beardsley’s representation from those of pornography save the notion that his is an artistic interpretation of a classical play. The bodies are not overly realistic, and there is a pleasant balance in the picture as a whole, but the technique does not seem to ‘master’ the content. There is no distancing technique and the sexual body is highlighted rather than denied.

Aubrey Beardsley, Lysistrata Haranguing the Athenian Women, 1896 | Anonymous. From 1000 Nudes: A History of Erotic Photography from 1839-1939 (Uwe Scheid Collection, Taschen)

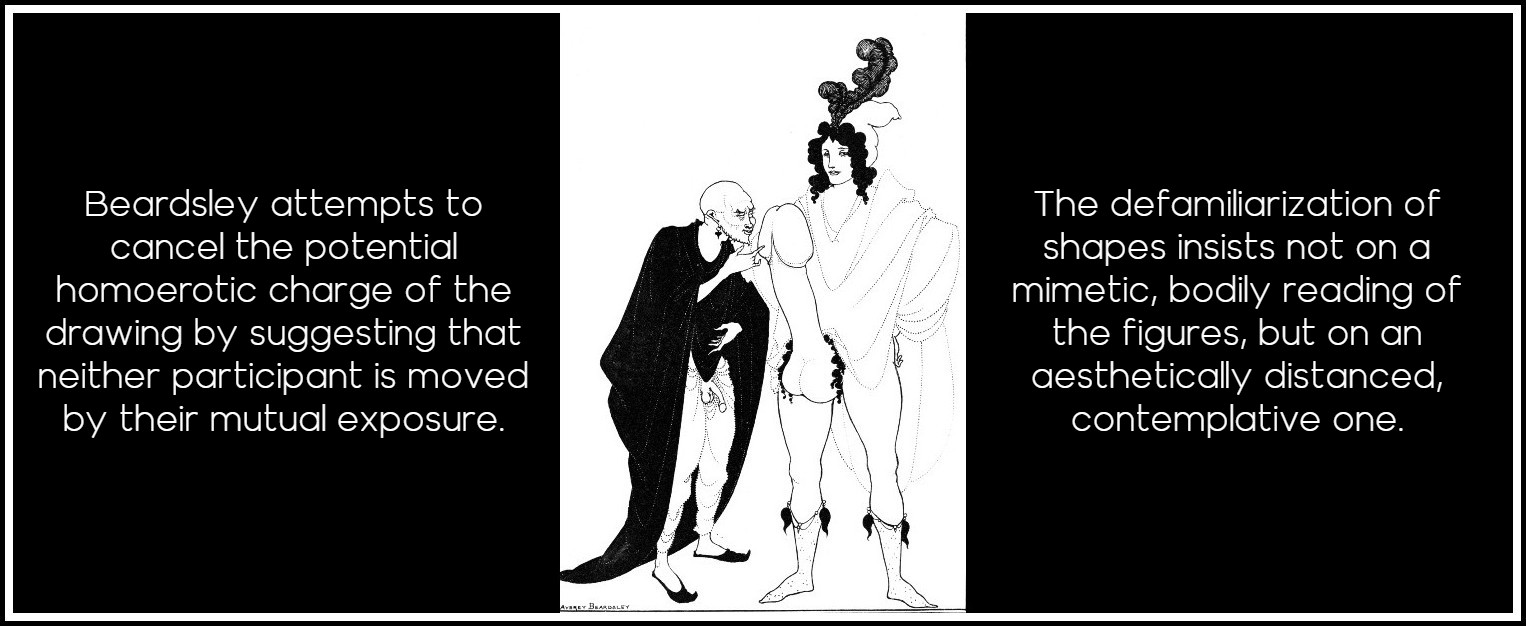

Beardsley attempts to cancel the potential homoerotic charge of The Examination of the Herald by suggesting that neither participant is particularly moved by their mutual exposure. The herald reveals his pornographically grand penis to the orientalized old man who, penis adroop, finds the organ an object of curiosity, but, as the flaccid state of his penis attests, not especially stimulating. The herald’s equipoise is demonstrated by his easy posture. Hands upon his hips, lips in a grin of complacency, he merely stands to allow the old man an inspection. A gesture with potentially powerful homoerotic content, a man fingering another’s penis, is drained of its subversive charge in the apparent disinterest with which each undertakes the inspection. The penis is not a sexual subject, but rather a mere object of curiosity. The exoticism of the older man, whose symbolic earring renders him less overtly masculine, and the grotesque disproportion of the herald’s organ to his body, distance the realistic portrayal of a pornographic pleasure. The defamiliarization of shapes insists not on a mimetic, bodily reading of the figures, but on an aesthetically distanced, contemplative one.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Examination of the Herald, 1896

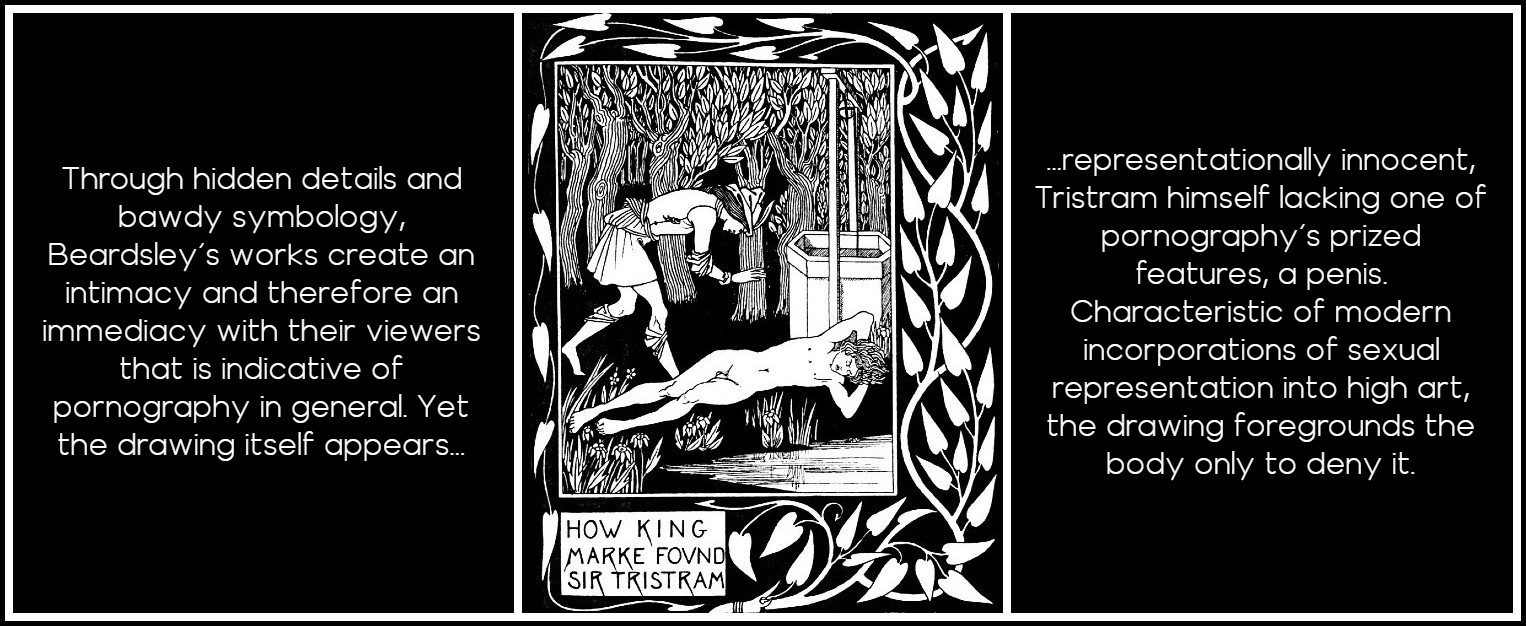

In How King Mark Found Sir Tristram Sleeping, the male genitalia are equally the object of a gaze, this time one that assimilates either shock or excitement. Each of the bodies in this illustration is gender-problematic. The sleeping Tristram is, with his long hair, accentuated chest, and oddly ambiguous genitalia, an androgynous figure. King Mark’s tunic folds at his midriff in such a way as to emphasize a feminized opening and a phallic lack. In Mark’s gaze upon Tristram’s genitals there is a sense of a homoerotic shame, compounded by the heart-shaped leaves that form the illustration’s border. Their insistence and directionality give phallic potency to the scene, as if to expose what isn’t realized by the characters. In Snodgrass’s words: Predisposed to hide salacious details within the structure of other images, Beardsley compounds the illusion (characteristic of pornography generally) that he is taking the voyeuristic reader into his confidence, providing a surreptitious (and often projective) glimpse into the guilty secrets of the text and perhaps even of the author himself.1 Through hidden details and bawdy symbology, Beardsley’s works create an intimacy and therefore an immediacy with their viewers that is indicative of pornography in general. Yet the drawing itself appears representationally innocent, Tristram himself lacking one of pornography’s prized features, a penis. Characteristic of modern incorporations of sexual representation into high art, the drawing foregrounds the body only to deny it.

1 – Christopher Snodgrass, Aubrey Beardsley: Dandy of the Grotesque (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995) 254

Aubrey Beardsley, How King Mark Found Sir Tristram, 1893

VIII. ANIMALS

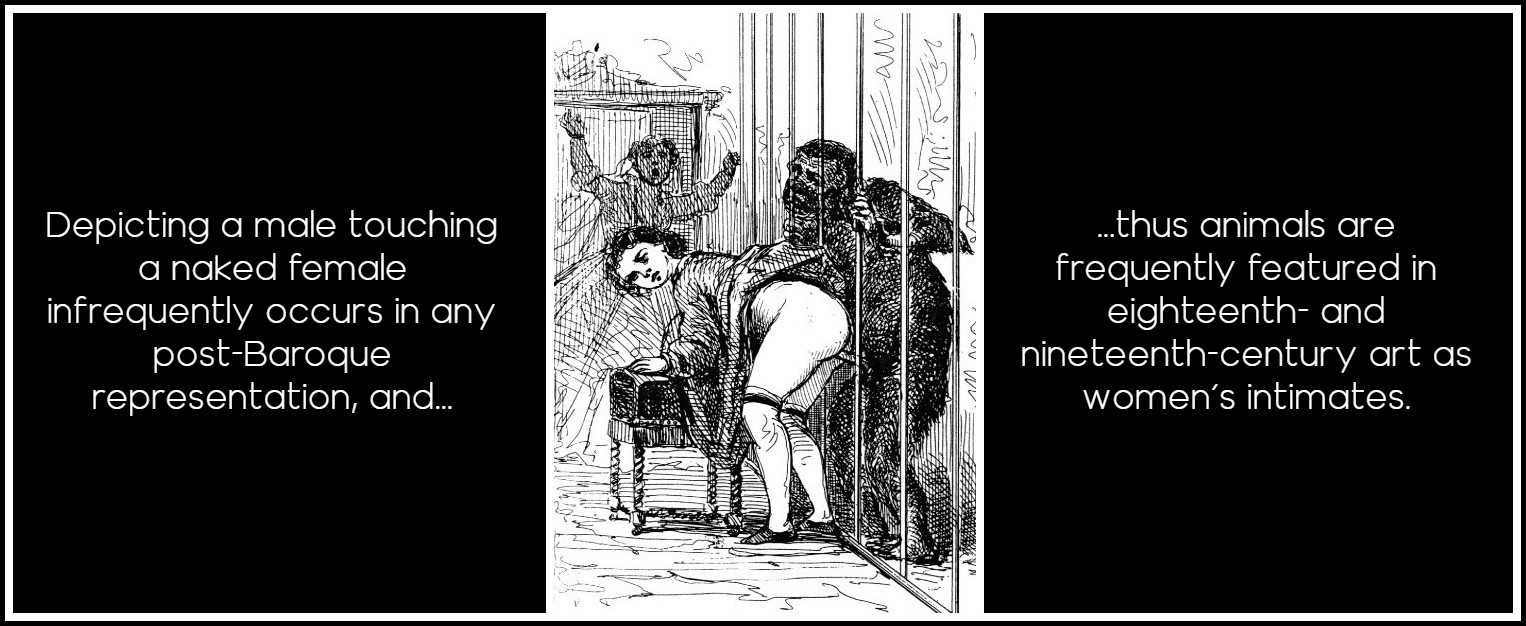

An intimacy with the symbolic tradition of women and animals is necessary to understand Beardsley’s continuation of and play upon these pornographic tropes. A long-standing pictorial tradition, women have frequently been paired with animals, typically dogs or monkeys, as functional male substitutes. Depicting a male touching a naked female infrequently occurs in any post-Baroque representation, and thus animals are frequently featured in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century art as women’s intimates. When in the nineteenth century scientific discoveries led to an entire discourse associating women with the ‘less evolved’ sensuousness of beasts, late nineteenth-century representations of women with animals began to take on a different overtone, a practical assimilation of erotic interests. Playing upon these associations, there was an entire sub-genre of Victorian pornography featuring women in erotic poses with animals. One illustration from Alfred de Musset’s The Gamiani, or a Night of Excess—a pornographic work from the first half of the nineteenth century that Beardsley specifically mentions having received from Smithers in a letter in 1896—features a woman about to receive an ape from the rear.

Alfred de Musset, Gamiani, ou deux nuits d’excès, Anonymous illustration, 1864

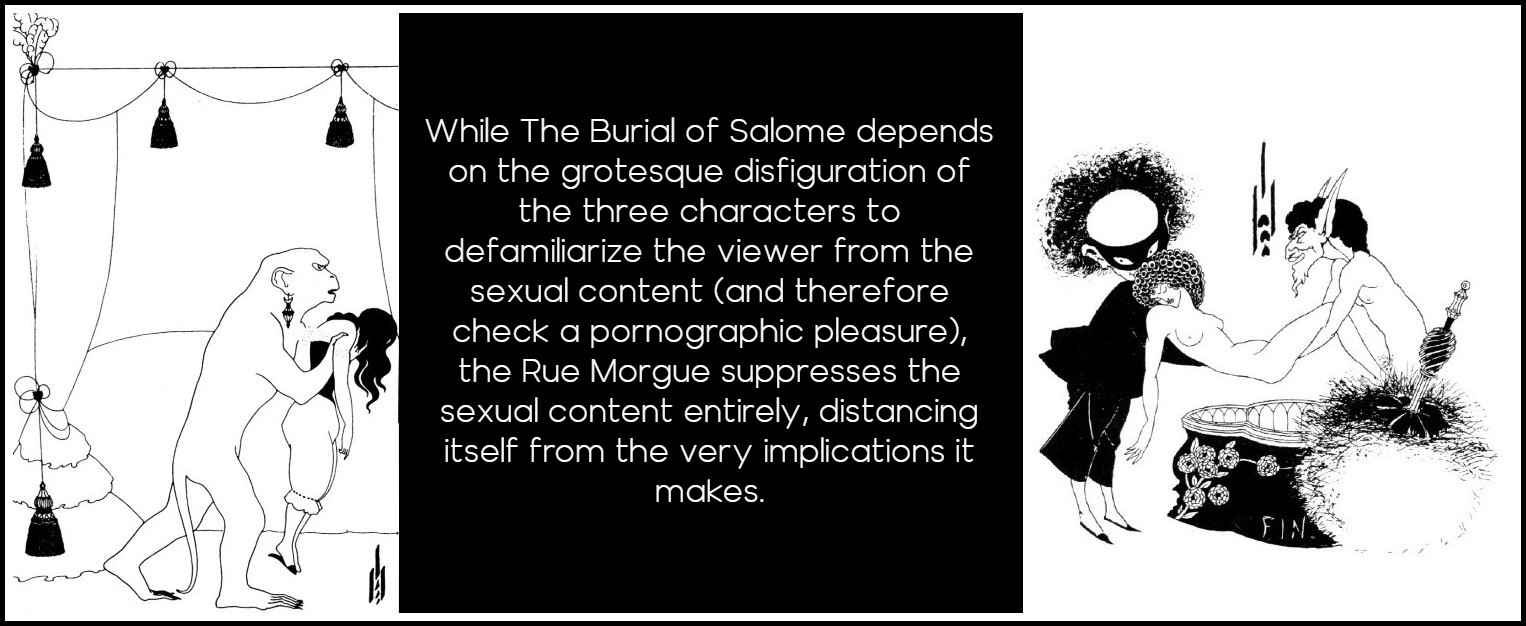

Knowing of Beardsley’s likely familiarity with the drawing, his illustration for the cover of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue takes on a more sinister and pornographic tone than what is implied by the drawing alone. His depiction appears more sinister because, as opposed to the pornographic representation where the woman shows herself to be an initiating partner, in the Rue Morgue, as in The Burial of Salome, a bestial figure appears ready to take advantage of an unconscious, if not dead, female corpse. In The Burial of Salome, for instance, the satyr figure appears fully aroused as he lowers Salome’s legs into her powder casket. His ears phallicly alert, eyes locked into a gaze, and mouth wearing a salacious grin, the growth from his pubic tuft is masked by Salome’s angularly located, phallic leg. His hands are notably hidden between her legs and he seems poised for sexual action, if not already partially engaged. While the ape figure of the Rue Morgue cover is less sexually overt, its association with a tradition of male substitutes makes the intention clear. Beardsley suppresses the directly pornographic depiction of sexual action or genitalia, using its tropes to signify a similar intent. While The Burial of Salome depends on the grotesque disfiguration of the three characters to defamiliarize the viewer from the sexual content (and therefore check a pornographic pleasure), the Rue Morgue suppresses the sexual content entirely, distancing itself from the very implications it makes.

Aubrey Beardsley: Cover design for Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue, 1896 | The Burial of Salome, 1894

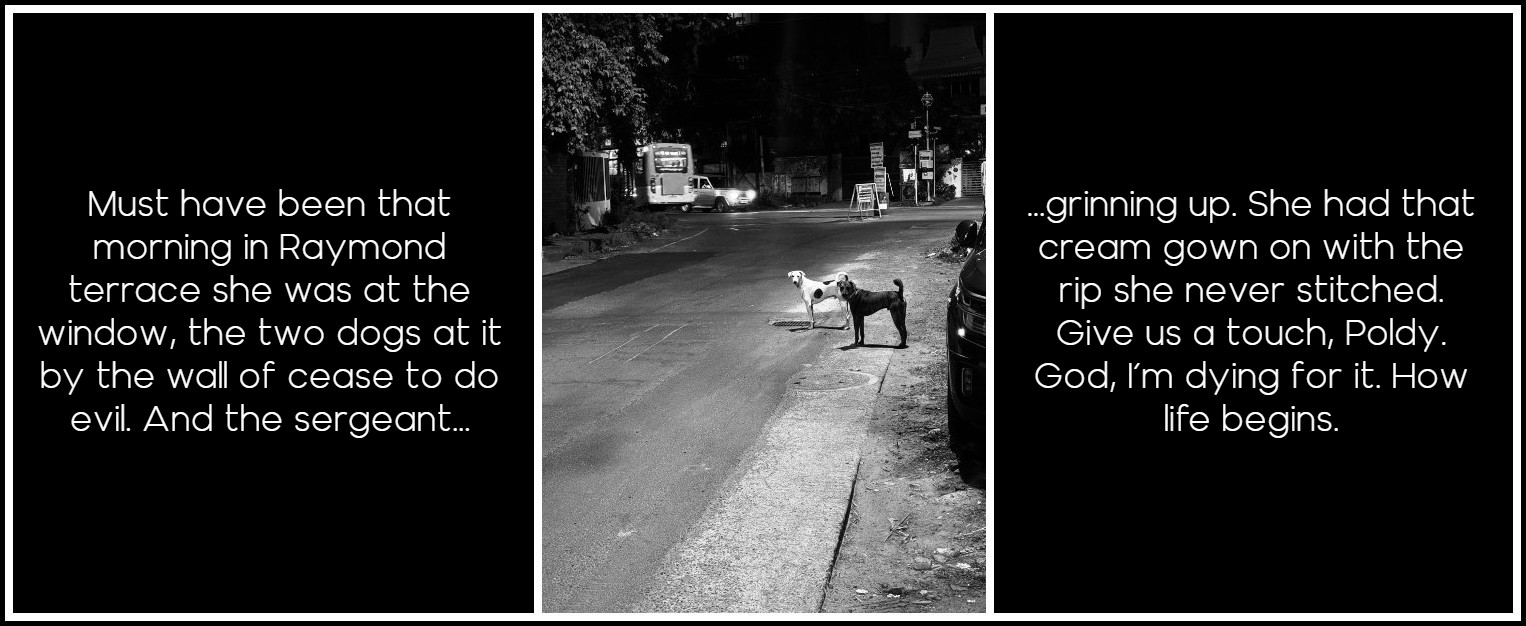

In a passage in Ulysses that conflates bestiality with voyeurism, Bloom recalls how he and Molly conceived their son Rudy: Must have been that morning in Raymond terrace she was at the window, the two dogs at it by the wall of cease to do evil. And the sergeant grinning up. She had that cream gown on with the rip she never stitched. Give us a touch, Poldy. God, I’m dying for it. How life begins. In a typical pornographic translation of the visual, Molly demonstrates a desire to set into practice what she has seen. The desire is made more illicit, more ‘dirty,’ in that she has seen animals have sexual intercourse. By turning to Bloom she acknowledges her desire to ‘do it like an animal,’ an assimilation that perpetuates the stereotype of the lower-class (and feminine) body as the bestial, sexualized body. While the sexualized intent of the passage is obvious, the narrative, a series of fleeting, semi-formed thoughts, briefly touches upon the pornographic moment. The moment is distanced from a representational realism by the use of slang terms for sexual intercourse, ‘at it,’ and ‘give us a touch’ Metonymizing the full acts, Joyce effectively delimits and controls the pornographic, bodily content contained within the narrative.

Photo: Arvind Mahesh, Unsplash

IX. THE EXOTIC OTHER

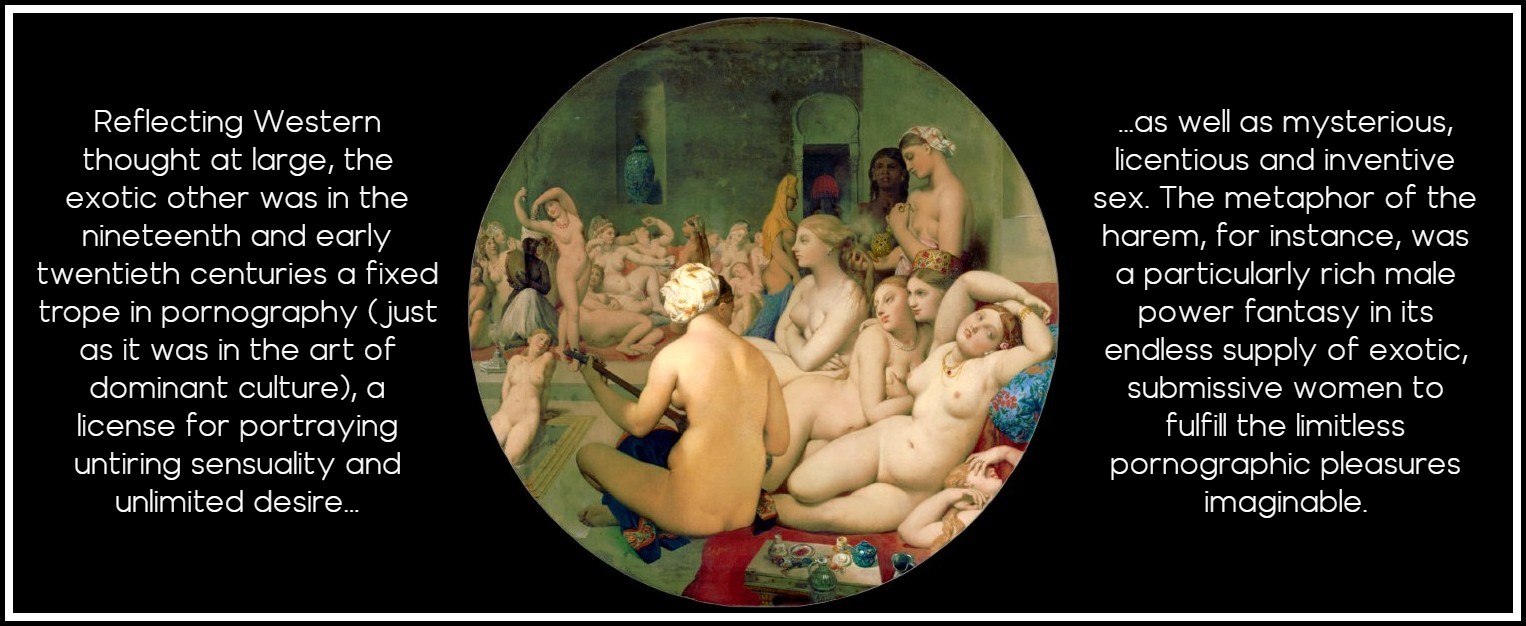

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century pornography capitalizes on imperialistic fantasy in countless ways, playing upon the Western idealization of the Orient (considered in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to be what is now called the Near East and North Africa) as a locale seemingly unfixed by the more rigid social and institutional codification of sexuality in the West, and therefore open to its fantasies. As a subject for art, the exotic lies outside the restrictive operations of classical rules and opens up an entirely unexplored imaginative region. Pornographic notions of the Orient, just as hegemonic cultural notions, do not necessarily reflect any specific reality of the Orient, but, as Edward Said has suggested, do reflect a particular European definition of itself as contrasting image, idea, and experience to its exoticized other.1 Reflecting Western thought at large, the exotic other was in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a fixed trope in pornography (just as it was in the art of dominant culture), a license for portraying untiring sensuality and unlimited desire as well as mysterious, licentious and inventive sex. The metaphor of the harem, for instance, was a particularly rich male power fantasy in its endless supply of exotic, submissive women to fulfill the limitless pornographic pleasures imaginable. Many a pornographic novel played upon this—The Lustful Turk (1828), Scenes in the Seraglio (c. 1860), and A Night in a Moorish Harem (c.1906) being but a few examples of the exotic’s lasting hold on the British imagination. Buck Mulligan expressed his own version of the harem fantasy in ‘Oxen of the Sun,’ where he proposed to set up a national fertilising farm to be named Omphalos with an obelisk hewn and erected after the fashion of Egypt where he would offer his dutiful yeoman services for the fecundation of any female of what grade of life soever who should there direct to him with the desire of fulfilling the functions of her natural.

1 – Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978) 1-2, 188, 190

Ingres, The Turkish Bath, 1862

Joyce shows travel writing to be an important ‘empirical’ source feeding the abstractions of Bloom’s vaguely pornographic fascination with all things Turkish. While attending Dignam’s funeral Bloom imagines the cemetery caretaker luring a woman back to his home for a sexual encounter. The association recalls for him ‘Whores in Turkish graveyards’, the Turkish custom of prostitution in graveyards frequently noted by nineteenth-century travel writers (Bloom possesses several books of travel writing in his library). The lugubrious practice looms large in Bloom’s imagination, and, in combination with the other commonly encountered expressions of Oriental sexuality played up in the pantomime or music-hall songs, exposes how Oriental sexuality was a mass-produced cultural fantasy of exotic, sexualized otherness. Intermittently throughout the day Bloom imagines Molly in Turkish pants, and in ‘Circe’ has a vision of her in Turkish costume: Opulent curves fill out her scarlet trousers and jacket slashed with gold. A wide yellow cummerbund girdles her. A white yashmak violet in the night, covers her face, leaving free only her large dark eyes and raven hair. Prepared for a pantomime performance, Molly’s costume conflates the sexual description of the Sweets of Sin (her ‘opulent curves’) with the eroticism of the theater (a public, bodily performer) and the mysterious, exotic Orient (her face but half revealed by the yashmak). The transgressiveness is further compounded by the fact that Molly is dressed as a man. She is in this image an exotic other, an image for pornographic fantasy.

Eugène Delacroix, Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement, 1834

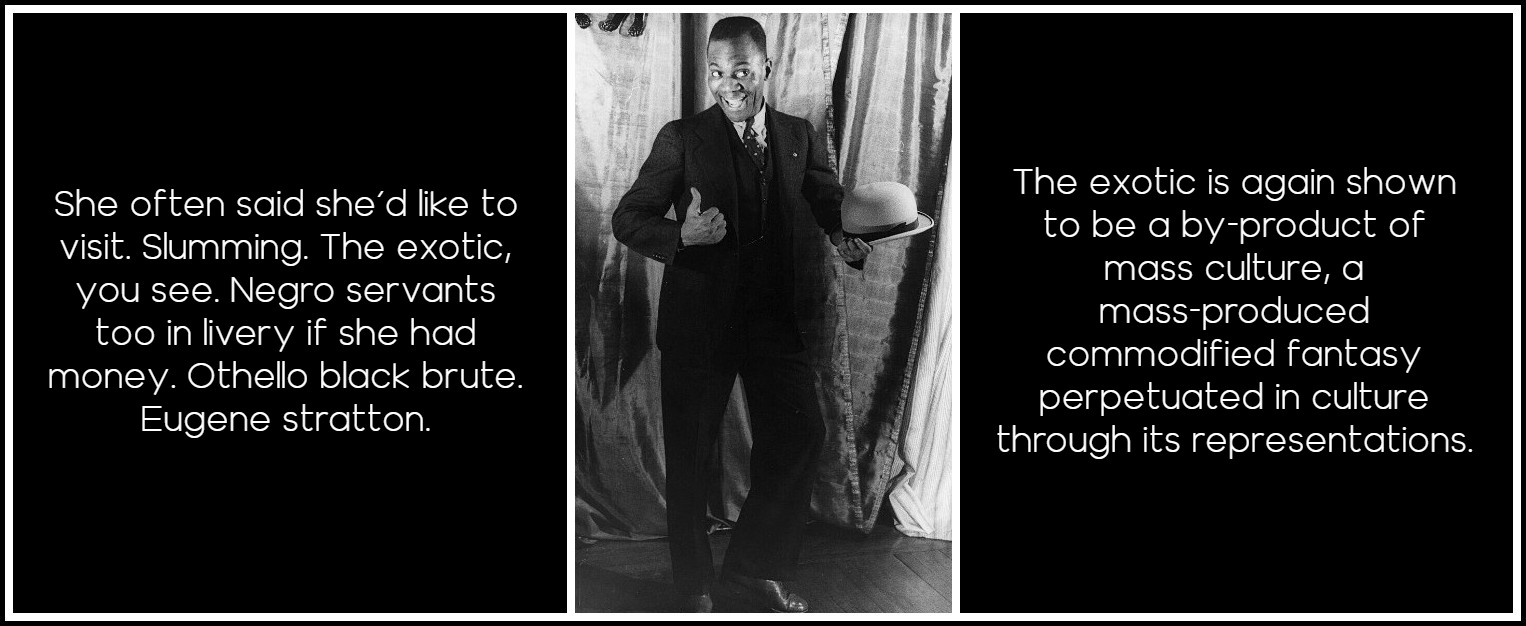

Bloom claims in ‘Circe’ that Molly also harbors exotic sexual fantasies. Explaining his appearance in nighttown to Mrs. Breen as a participation in or extension of Molly’s fantasies, he says: She often said she’d like to visit. Slumming. The exotic, you see. Negro servants too in livery if she had money. Othello black brute. Eugene stratton. Even the bones and cornerman at the Livermore christies. Bohee brothers. Sweep for that matter. Each of these references is to black performers or their impersonators, personalities of the music-hall stage. The exotic is again shown to be a by-product of mass culture, a mass-produced, commodified fantasy perpetuated in culture through its representations. The commodification of the exotic as sexual fantasy is made startlingly clear in the multiplicity of turn-of-the-century French postcards featuring exotic women.

Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson, 1925 | Photo: Carl Van Vechten

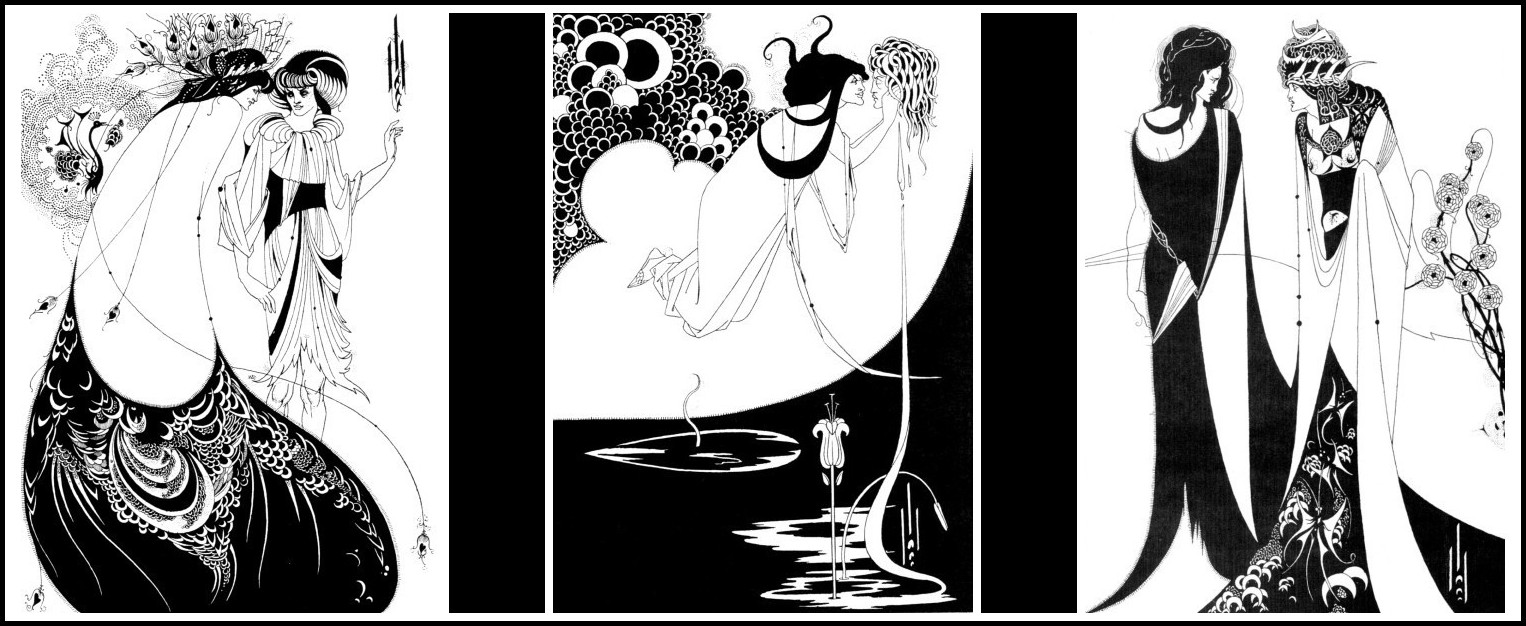

The myth of the exotic other is the enabling myth of Beardsley’s illustrations to Wilde’s Salome. That is, based on cultural assumptions of the Orient as sexually fecund, licentious, and libidinally voracious, other to the bourgeois Anglo-Saxon self, Beardsley is given greater freedom with Wilde’s already suggestive play than might otherwise have been the case if he had been representing, say, the Arthurian legend (which equally features a woman-as-temptress in the figure of Guinevere). Pornographic details abound in the Salome drawings, and perhaps for the first time in a work of art with such obvious high-cultural aspirations, tumescent penises make their way into public visibility.

Aubrey Beardsley, Salome, Oscar Wilde

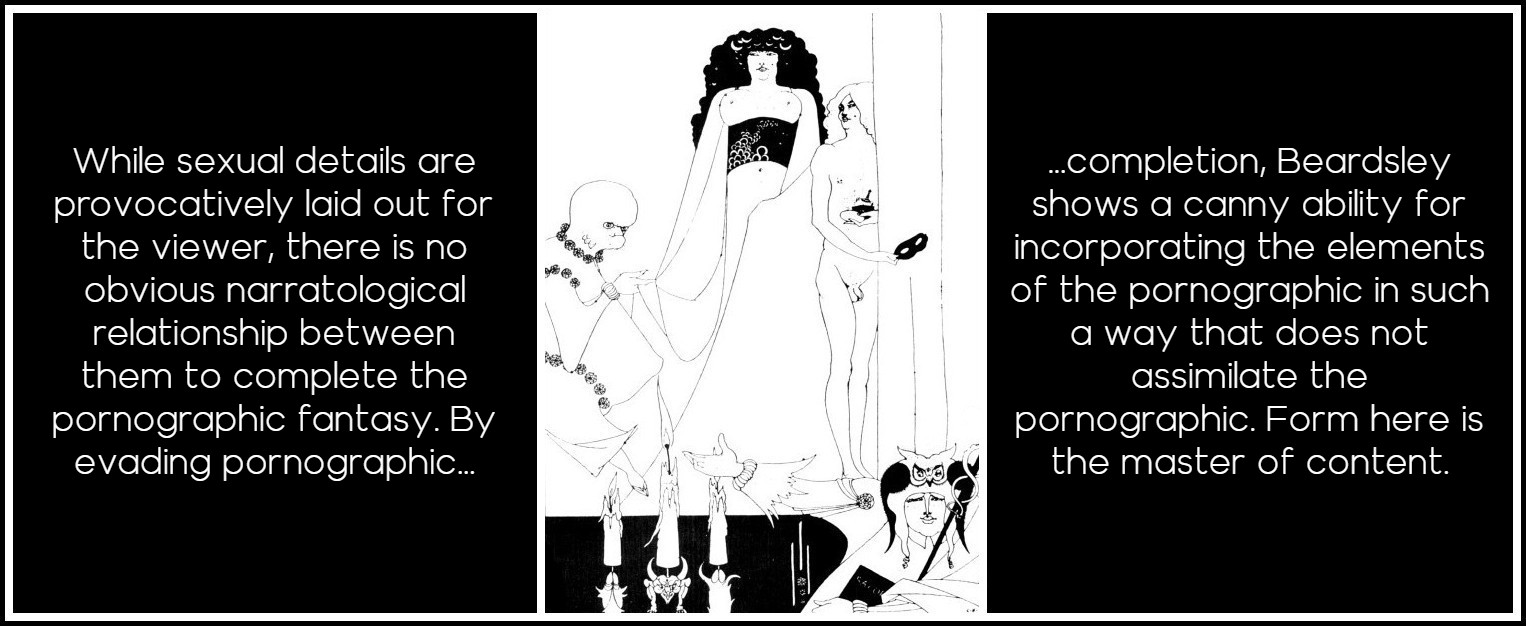

Enter Herodias is an amalgamation of exotic others, each figure representing Beardsley’s penchant for the grotesque. The bizarre form of Herodias at center, with her huge balloon-like breasts and her pillar-like posture, would seem to be the illustration’s focus, and yet none of the characters in the drawing directs their gaze at her. To her left, an undressed, effeminate page boy stands, genitals exposed and notably flaccid in Herodias’s attendance. While his genitals betray him as male, his face and hair suggest the female. He is holding a mask, as if to suggest that his sexuality is itself a performance. He is in every sense a sexual other, denying not only a heteronormative response to Herodias’s sexualized presence, but sexual classification itself. The figure on Herodias’s right, a grotesque combination of Beardsley’s foetus and old man figures, displays a rather large erection protruding through his clothing. Though again, oddly, he gazes not at the presumed sexual focus of the drawing, Herodias, but offstage. To emphasize the figure’s erection, three candles burn in the lower left portion of the frame, two held up by erect-penis candlesticks. There is sexual excitement in the frame, but, unlike a pornographic representation, it is an undirected excitement. In a pornographic representation, energy is focused on the sexualized object of the gaze, often directed there through a mediating voyeur figure whose own excitement in gazing at the sexual object is intended to function as a model to the viewer’s. While Herodias would seem to be the intended object of the gaze, the mediating figures of the drawing offer the viewer no assistance, and in fact distract attention from her rather than reinforce it. What is overtly sexual in this picture, exposed breasts, protruding erections, and upright penis candlesticks, is juxtaposed and circumvented in the style of a Joycean narrative. While sexual details are provocatively laid out for the viewer, there is no obvious narratological relationship between them to complete the pornographic fantasy. The visual organization of a pornographic image relies on a narrative telos to engage the reader in completing that telos in his or her imagination, and, by extension, on his or her body. By evading pornographic completion, Beardsley shows a canny ability for incorporating the elements of the pornographic in such a way that does not assimilate the pornographic. Form here is the master of content.

Aubrey Beardsley, Enter Herodias, 1894

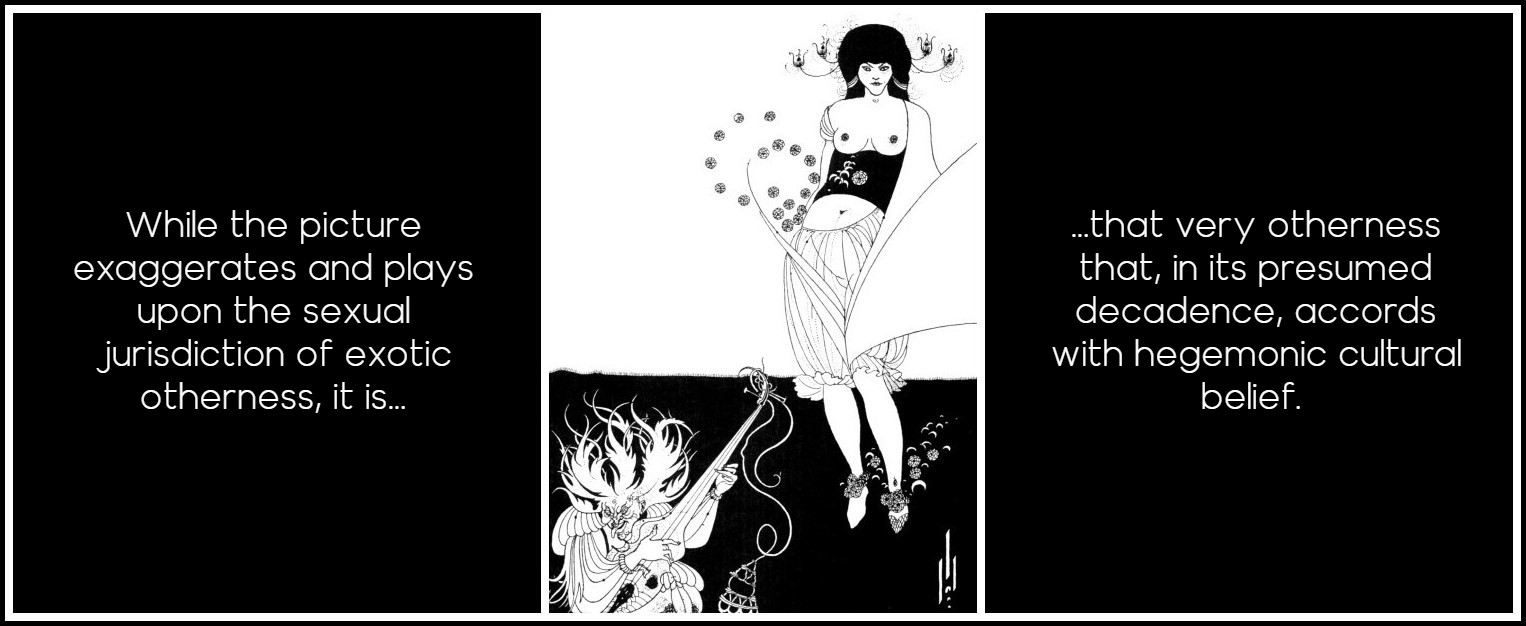

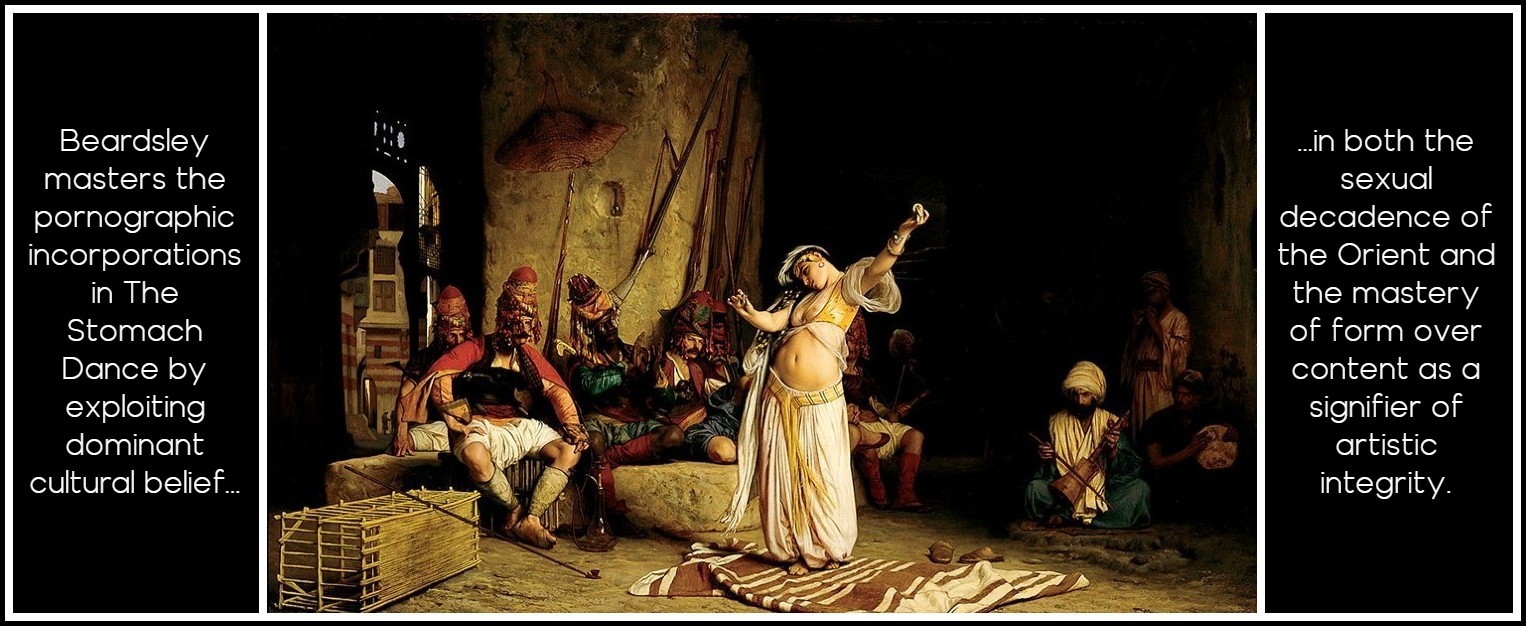

In a similar depiction of the exotic other, The Stomach Dance, Beardsley is able to present a more accessible pornographic pleasure while still maintaining the hegemony of form. In The Stomach Dance the implied gyrations of Salome’s body provoke an erection from the grotesque musician accompanying her, but the swollen penis is skillfully drawn to blend in with the folded design of his costume. While the picture exaggerates and plays upon the sexual jurisdiction of exotic otherness, it is that very otherness that, in its presumed decadence, accords with hegemonic cultural belief.

Aubrey Beardsley, The Stomach Dance, 1893

A painting of almost identical subject, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s La Danse de l’almée, created a controversy when it was first exhibited at the Salon of 1864, but was a major success with the public and certain critics who, not surprisingly, found high-art, classical validations for it in the qualities of stasis and universality. The painting was noted by one critic for the universal combination of the frenetic movement of the arms and the torso set upon ‘legs of marble.’1 Beardsley masters the pornographic incorporations in The Stomach Dance by exploiting dominant cultural belief in both the sexual decadence of the Orient and the mastery of form over content as a signifier of artistic integrity.

1 – The Orientalists: European Painters in North Africa and the Near East, ed. Mary Anne Stevens (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1984) 139

Jean-Léon Gérôme, La Danse de l’almée, 1863

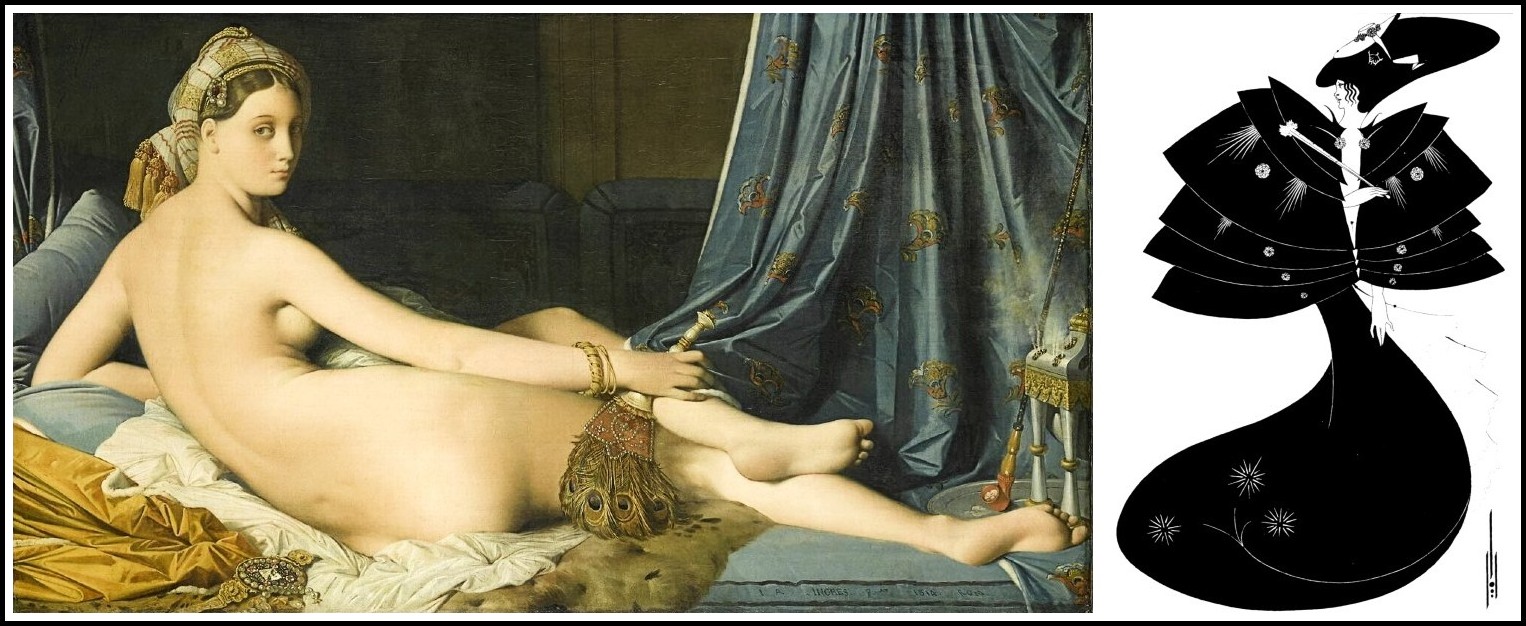

It is nowhere more clear than in the Salome drawings that Beardsley fully exploited high-cultural beliefs and signals in order to introduce into his works the potentially subversive. That subversive material, however, points out the merely stylized quality of the art that attempts to contain it, and by doing so travesties, or parodies, the very nature of high art. Though Beardsley successfully appropriated the pornographic for high-cultural consumption, importantly, the pornographic, unlike Gerty MacDowell’s attempt to be ‘Greekly perfect,’ successfully embodied high art. Inasmuch as the formal techniques of Joyce and Beardsley limit the pornographic tropes and images that they employ, those tropes still speak the body, and render a more diverse form of discursive representation than offered in post-Renaissance art.

Ingres, Une odalisque, dite La grande odalisque, 1814 | Aubrey Beardsley, The Black Cape (Salome), 1894

I call the incorporation of pornographic tropes and images into art an ‘aesthetic of the obscene:’ a paradoxical phrase that captures the tenuous nature of representing the unrepresentable. Beardsley and Joyce were masters of the aesthetic of the obscene in that they were foremost masters of the distancing techniques of a formal aesthetic. As critical focus moved in their time from the represented to the representing, a mode of aesthetic reception was privileged that served once again to de-emphasize the body, ironically in a move that made way for the representation of bodies. Bodies could be portrayed so long as readers or viewers could be taught to concern themselves not with the bodies themselves, but with how those bodies were portrayed, in what form they were manifest. The idealization of the body continued with the privileging of form. There were plenty of people, however, who remained unschooled in this aesthetic understanding, and, in their affiliation with the body, were labeled ‘the mass.’ While the masses were seen as bodily consumers of art in an oppositional mode to bourgeois reception, a mode of aesthetic reception gradually developed throughout the twentieth century that was more akin to a sensuous subjugation.

Aubrey Beardsley, Self-portrait, 1896 | Djuna Barnes, Portrait of James Joyce, 1922

This, ironically, can be attributed in part to the increased visibility of sensuality on the pages and canvases of the works of writers and artists such as Joyce and Beardsley. For while it is possible to read their incorporation of pornographic tropes and images into high art as an aesthetic appropriation or domination of the pornographic, such domination lasts only as long as the techniques with which they were conceived can be interpreted; that is, the distancing techniques of parody soon turned to simple pastiche as sexual representation in art became itself normative. We in the late twentieth century can no longer discern the parodic edge accompanying pornographic representations in modern artworks because they no longer bear the shock of the pornographic. The genre as it existed then is lost to us except as we are able to recover it through historical investigation. The acute sense of separation by which art and pornography existed previous to these artists has been mitigated by them and the artists that followed. Though to be sure pornography as a genre still exists today, it has, as a category, been altered by the emergence of explicit sexuality in works considered art. More obviously, art has been colonized by pornography. What is considered pornographic persistently pushes at the periphery of art. Through the agency of modern artists, the boundaries between art and pornography have shifted dramatically.

James Joyce, 1937 (Photo: Josef Breitenbach) | Aubrey Beardsley, 1894 (Photo: Frederick Evans)

ALLISON PEASE: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments