Fairytale Motifs – Gothic Readings – Castle in the Air

KAFKA: THE CASTLE – ANALYSIS

Patrick Bridgwater

Abbreviated from Patrick Bridgwater, Kafka, Gothic and Fairytale (Amsterdam-New York: Editions Rodopi, 2003) pp. 147-160

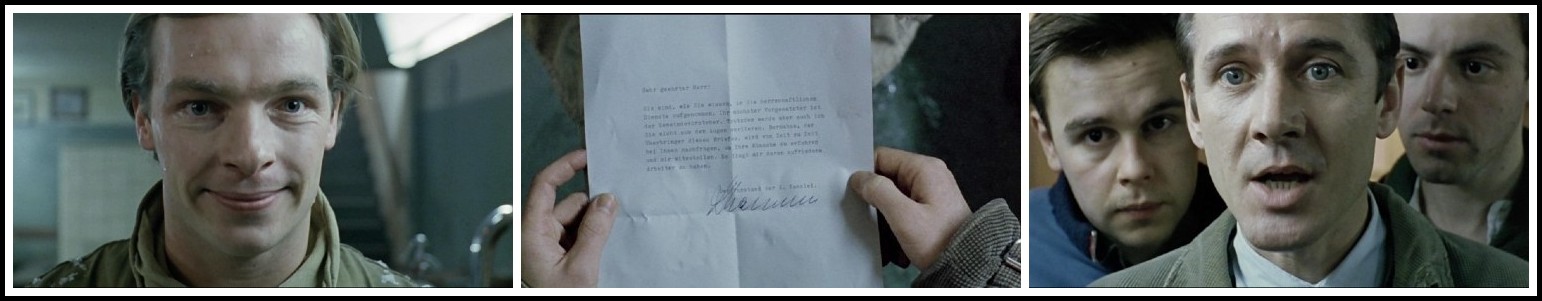

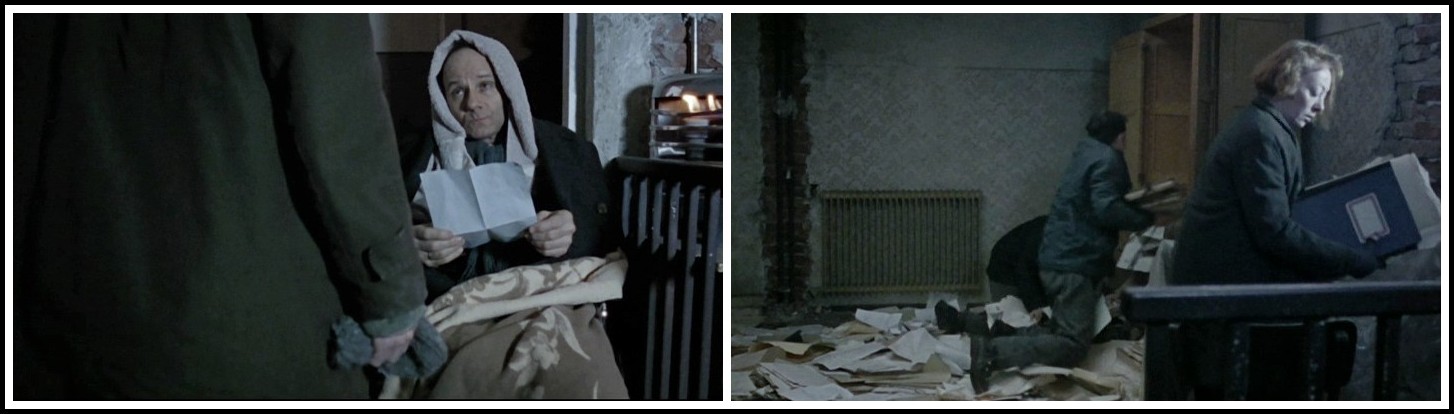

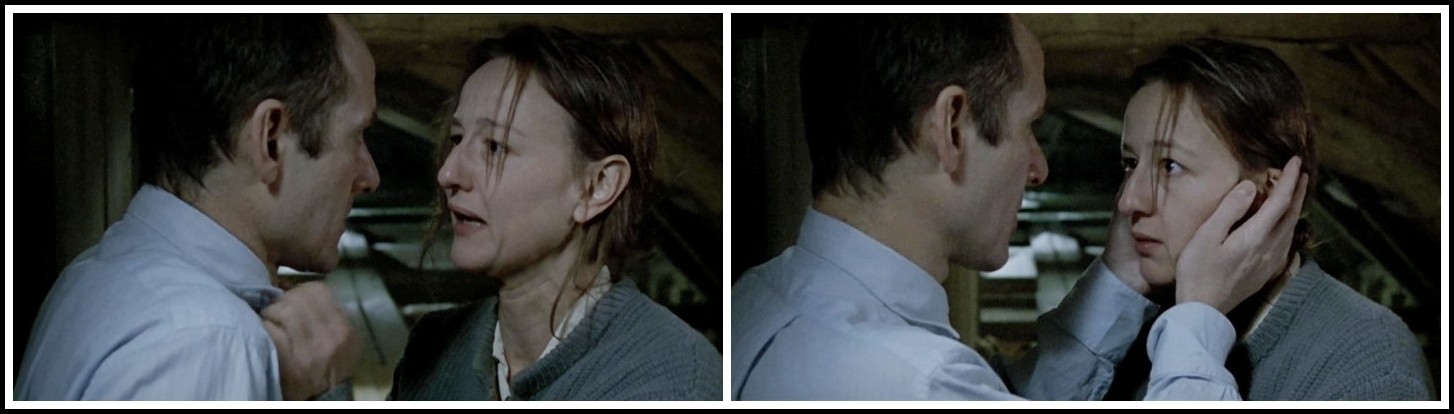

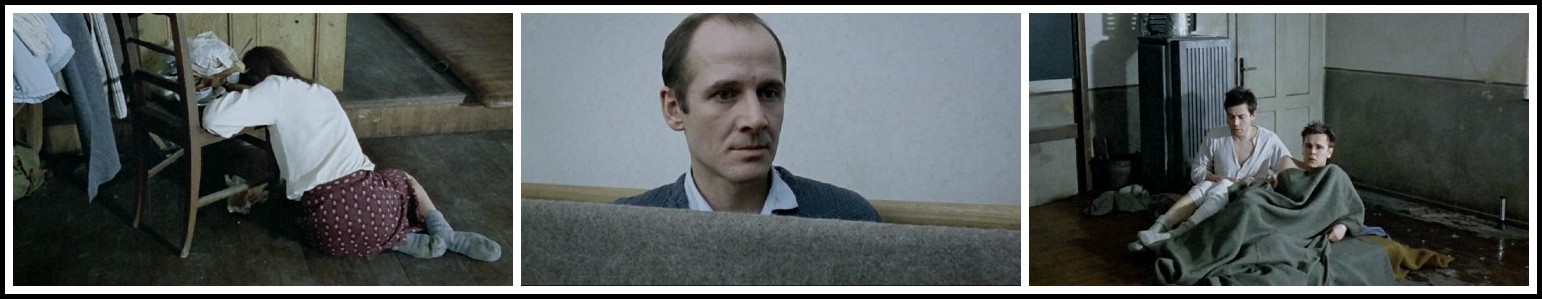

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

I. FAIRYTALE MOTIFS

The Castle follows a common fairytale pattern in that while the opening paragraph bears some resemblance to reality, the protagonist swiftly passes ‘through the looking-glass’, here represented by the bridge, into an inside-out world of externalized inner reality. We are not told where K. comes from or what he has been prior to his arrival on the bridge that symbolizes his transition to a realm of increasingly challenged consciousness. Kafka goes beyond some versions of the fairytale motif in introducing his hero not at the moment of departure, but at the moment of arrival in a new, alien world. The bridge on which K. is found standing in the first paragraph is tantamount to the ‘bridge to the otherworld’ of fairytale, except that here the otherworld is internalized. Arriving to take up a post is itself a fairytale motif, and the fact that K. travels from afar seeking to gain entrance to an arguably empty castle is a version of the fairytale motif of the stranger who travels from afar and enters an empty, silent castle.1 The telephone by means of which contact appears to be established with the Castle is an example of ‘prop shift’ in the modern fairytale. The enchanted or accursed castle as such is an important motif borrowed from fairytale by Gothic, but The Castle involves, more specifically, the castle that suddenly appears, standing on a mountain. This is what K. sees when he steps outside following his first night in the village. The Castle has many features that equate it with the ‘edifice’ of fantasy.1 In fairytale the enchanted castle may be the Devil’s house; in many ways that is what it is for K.

1 – Cf. Max Lüthi, The Fairytale as Art Form and Portrait of Man, tr. Jon Erikson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1987) 119

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

More specifically, this castle supposedly inhabited by Klamm, who comes to loom so large in K.’s mind, is reminiscent of the castle-in-the-air inhabited by a Giant. Both are possible metaphorical models for Kafka’s Castle. In other respects it resembles the magic or accursed castle of folklore and fairytale, being magic in having neither entrance nor exit and in changing its appearance to the extent to which it does. Its ambiguity is itself a fairytale feature, for it combines the Castles of Light and Darkness of fairytale. The Castle of Light, representing a lofty, spiritual goal, often appears and disappears like a mirage, and is usually set on a height. All this applies to Kafka’s castle, which, although veiled in mist and darkness when he arrives, is, on the following morning, revealed ‘clearly defined in the sparklingly clear air’, the covering of fresh snow seeming to emphasize its identity as a Castle of Light. In the novel, unlike in fairytales, the castle does not suddenly appear in the path of the wanderer; on the contrary, it is so shrouded in mist and darkness as to appear non-existent, the irony being that in symbolic terms it really is non-existent, so that it is its appearance in the full light of day, as an apparent Castle of Light, that is truly misleading. The darkness in which it is hidden associates it with the Castle of Darkness representing a fearful challenge and symbolizing evil and death. Such a castle contains a treasure to be wrested from dark powers within it. That the symbolism of darkness prevails, suggests that this is also the ‘castle of no return’ of fairytale: the will to salvation, symbolized by the castle, may be there, but there is no sign whatsoever of salvation as such, just every sign of the triumph of chaos and darkness, in other words, of death.

1 – See John Clute and John Grant, The Encyclopedia of Fantasy (London: Orbit, 1997) 309f.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

The figures in The Castle resemble those in fairytale in extending all the way from Count to stable-lad. Like fairytale figures, they are figures without substance, inner reality or history; they lack any relation to past and future. Even Klamm, a figurative ogre who looms so large in K.’s thinking, is a shadowy figure who in his inscrutability and intangibility retains the aura of otherness of the fairytale. K.’s attempts to obtain from this ogre-like figure the boon of certainty are reminiscent of the fairytale motif of attempting to capture the ogre’s treasure. The ‘maiden from the castle’ is reminiscent of the same figure in Icelandic fairytale, who gives the hero directions on his quest. The ‘maiden from the castle’ also involves an echo of the Bluebeard tales, as does the sinister Sortini, one of Klamm’s personae, and the story of K.’s violation of Klamm’s sledge, too, contains the basic elements of the Bluebeard story, that is, a forbidden chamber, an agent of prohibition and punishment, and a figure who violates the prohibition. K.’s ‘assistants’ are caricatures of the ‘helpers’ of fairytale, here subverted into useless, comic figures. Barnabas is the ‘bringer of good news’ of fairytale, subverted into a bringer of unreliable, ambiguous news.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

The episode in Chapter 11 of The Castle, when a large black cat bounds in in the middle of the night, giving K. ‘the biggest fright he had experienced since his arrival in the village’, is reminiscent of the two big black cats who bound in towards midnight in Grimm’s ‘Tale of one who set out to learn how to be afraid’. In Grimm the incident takes place, suggestively enough, in an enchanted castle. The black cat, in folklore the witch’s familiar, stands for her.1 Amalia’s garnet necklace may have been suggested by the miller’s daughter’s necklace in ‘Rumpelstiltskin’, the reason for the reference, if intended, being the fact that the tale embodies the ‘impossible task’ which is at the heart of Kafka’s view of life in general and of this novel in particular. The three versions of Amalia’s story (as told/seen by Amalia, Olga, and their father) are reminiscent of the three tales told by the Queen in ‘Snow White’. In the background, in the Bürgel episode, is the fairytale motif of resisting sleep for an impossibly long time. The way in which K. falls asleep at precisely the wrong time links him with the villain of fairytale, while the way in which he was to have been cheated by death at the end of the novel involves the reversal of the common fairytale motif of deceiving death by disguise, shamming, or substitution. While it clearly does not lack fairytale features, The Castle as a whole is closer to nightmare, and therefore to Gothic, than to the fairytale as such, although elements of the two forms are intertwined, for when the tale of wonder is deprived of its wonder, what remains is the tale of terror. The way in which K.’s life slips further and further beyond his control is Gothic through and through.

1 – Cf. Gisa, whom K. calls ‘a sly, deceitful cat’.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

II. GOTHIC READINGS – CASTLE IN THE AIR

Kafka’s last novel, The Castle was written in 1922, although an early fragment went back as far as June 1914, that is, to the time when he was writing The Trial. Published posthumously in 1926, this fragment, which does not figure in the novel as such, is a fairytale version of the beginning: ‘One summer evening I came to a village in which I had never been before.’ When Kafka came to write The Castle, he began writing it in the first person, only to change this later. As these first-person, ‘fairytale’ beginnings indicate, the protagonist, K., is again a part-autobiographical figure. In effect he is an older, refocused and therefore altered version of Josef K., relating to Kafka in partly different ways. The Castle is a reformulation of The Trial with a different emphasis, as self-definition is now challenged by feelings less of guilt than of nonentity and worthlessness.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

In order to underline his point that one cannot hope to understand things from the outside, Schopenhauer wrote ‘In that case one would be like a man walking round a castle, looking in vain for an entrance’.1 On one level this gave Kafka his starting-point, but his Castle, as the enigmatic remainder of a metaphor whose first term has been suppressed, is not only a thoroughly Gothic one; it is also an ‘air-built vision’, a ‘castle-in-the-air’, for Kafka ‘built many castles in the air, and peopled them with secret tribunals’.2 What makes K.’s Castle different is the fact that it represents his self. It is his own castle, his inner citadel, the key to the lock of which is in his hands alone, if he can but find it. The Castle therefore cannot be approached from outside, which K. is necessarily shown trying to do in the novel, although the fact is misleading, for in truth he is trapped inside it in the sense of being trapped within his own mindset, his delusion of significance. The Gothic motif of trying to escape from the castle-prison, inverted on the literal level, applies on the figurative level.

1 – Arthur Schopenhauer’s sanuntliche Werke in sechs Banden, ed. Eduard Grisebach (Leipzig: Reclam, n.d.), I, 150

2 – Like Scythrop (Shelley) as described by Peacock in his spaghetti-Gothic Nightmare Abbey. See Shelley, Zastrozzi, ed. Behrendt, 81.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

Klamm, who comes to symbolize the Castle in K.’s mind, is similarly non-existent in any objective sense. In Czech klam means ‘delusion, fallacy, error, deception’, each term more relevant and, from K.’s point of view, negative than the one before. Klamm’s name therefore carries the idea of deception, delusion, beguilement. All appears to be klam a mam.1 The question is whether Klamm is real. His name implies that he is not, but there is no certainty when the name is Deception. The fact that Kafka, in his manuscript, twice wrote Klam, and then changed it into Klamm, confirms the meaning of Klamm’s name, and is also as good an illustration as any of the fact that one of his main reasons for making amendments to his text was to disguise his meaning. He needed to express and thereby exorcize his inner demons without exposing them too openly to prying eyes.

1 – Lies and deception; cf. Klamm and Momus.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

K. in his new guise is the mysterious stranger and wanderer of Gothic convention, the accursed wanderer of fantasy. The length of K.’s journey is stressed, as is the ‘fact’ that he lost his way several times and only arrived in the village ‘by mistake’, an ominous inversion of the fairytale formula ‘as if by magic’. Once K. has arrived, the novel is, on the face of it, about his attempts to have his appointment as ‘land-surveyor’ confirmed. If one remembers that the Castle is in reality not a ‘great Castle’, but a little town, and thus tantamount to a village, and that the verb sich vermessen means ‘to make a wrong measurement, to misjudge’,1 it will be clear from the outset that there is again much more to this novel than meets the eye, and that ideally the eye needs to be reading it in German, for much of the meaning of this novel is buried in German secondary meanings and puns and then develops in a formally realistic narrative which is in reality the very opposite of realistic in the anticipated sense. The anticipation is the reader’s, for Kafka reality is unrealistic and inward. What this means is that The Castle is less straightforwardly or superficially ‘Gothic’ than it seems, and a great deal more sophisticated, especially in a linguistic way, than any Gothic novel. Late Gothic here shades into high modernism.

1 – There is also the simple verb vermessen, ‘to survey’, and the adjective vermessen, ‘presumptuous’.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

Rambling, mysterious, ominous, this Castle, if castle it is, possesses, to an exemplary degree, the phantasmagorically shifting outline of the archetypal Gothic castle, its features, like those of Montoni’s castle in The Mysteries of Udolpho, ‘lost in the obscurity of evening’. In accordance with the spirit, if not the letter, of Gothic, the Castle is—apparently, arguably, symbolically—not a castle at all. The reader is told that ‘if K. had not known it was a castle, he might have taken it for a little town’, which is a glorious piece of misinformation, for K. knows no such thing; he is merely under an impression which practically everything shows to be mistaken. Phantasmagorically, its outline shifts as K. approaches it, so that it appears to be now a castle, now a kind of glorified village, and now simply an hallucinatory image, a shimmering mirage or castle-in-the-air. Alternatively, it can be seen not as a glorified village, but as a run-down town, the tatty remains of the once-celestial city of medieval art. In that case, K. as ‘land-surveyor’ might be compared to the ‘measurer’ of the New Jerusalem’s outer walls, but for the fact that K. is not a land-surveyor or measurer, but a mis-measurer, and even that only in a symbolic sense. Either way, the ‘suggestive obscurity’ of the Gothic novelist has never been put to better use.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

As in Gothic, the castle is dilapidated, its tower in particular scarcely tower-like. The village, where the castle authorities do their business, so that it is just as much a castle1 as the castle is a village, has its equivalent of the tower in the form of a church that turns out to be only a chapel. The village school has ‘a look of great age’ because in a symbolic sense it goes back to the Renaissance and its undermining of patriarchal authority in the form of the church. The school is linked to the Castle via ‘Schwarzer’.2 Castle and village are either image and counter-image, or identical one with the other, according to the perspective that continues to shift throughout the novel, which means that no one view of the Castle totally precludes another, and that there can be no certainty, only ever greater uncertainty. That the Castle is not only K.’s but Kafka’s is shown by the crows swirling round it: because kavka means ‘jackdaw’ in Czech, Kafka was in the habit of using black birds (ravens, crows, blackbirds) as an emblem and cryptic self-reference. The crow is moreover said to be ‘the devil’s bird’, and the raven too conceals further meanings.3 There is a highly appropriate, and quite invisible, further meaning involved, too, for kavka also means a dupe or gullible person, just the sort of person to be taken in by someone whose very name, Klamm, proclaims him to be a figment or phantom.

1 – Cf. that corridor full of doors in the public house, so reminiscent of a prison and therefore of Gothic.

2 – Cf. Karl R.’s nickname (Negro) at the end of Amerika, with its diabolical connotations. The Priest in The Trial is also a Schwarzer (Catholic priest), although he is not so dubbed in the text. And, of course, the school is linked to the Castle via K. himself, of whom all these figures are projections. K. is the one who needs to learn: Aphorism 22: ‘You yourself are the task. There is no other pupil in sight’.

3 – Colloquially, Rabe means a young offender, in which sense it is said to derive from Czech rab (in German, Knecht, groom, labourer, the status to which K. is finally, and appropriately, reduced).

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

Like the typical Gothic castle, K.’s Castle is the major locus and focus of the plot, ‘decaying, bleak and full of hidden passages’,1 and is associated with the feudal/patriarchal past, the age of superstition. The bureaucratic administrative forms associated with the Castle are, implicitly, as hollow and void of meaning as those practised in the Penal Colony following the death of the Old Commandant. Given the nature of the Castle and the identity of Klamm they could not be otherwise. With its wanderer hero, The Castle also points back to the last great early Gothic novel, Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer. Like it, The Trial dwells on religious superstition and The Castle on the spiritual emptiness of the post-Christian world. Both novels, in other words, are imbued with religious feeling, although it is a fugitive, self-doubting feeling, not to be identified with any particular religion claiming to validate it. If the Castle could be taken at face value, it would be true to say that ‘The unapproachable and unfathomable nature of law and authority is presented, in The Castle, as the looming, dark and distant edifice of Gothic terror’,2 for this Castle seems, like that of Udolpho, to be a ‘figure of power, tyranny and malevolence’.3 Evidence of the feudal past, with which the Castle is linked by its phantom owner, Graf Westwest, appears to be further provided by the treatment of Barnabas’s family by the ‘Castle-authorities’. In short, the Castle seems to be the seat of just the sort of arbitrary, autocratic patriarchal power that in Grosse’s Der Genius controls even people’s private actions.4 Kafka’s castle-authority thus appears to locate itself, loosely, in the German Gothic tradition, and Castle Westwest to be the locus of seemingly arbitrary power of Gothic convention, although the convention is reversed in that K. is, on the face of it, attempting to get into the castle (a fairytale motif), not escape from it (a Gothic one). In reality he needs to escape from his obsession with it, so this Gothic motif too is internalized.

1 – Fred Botting, Gothic (London: Routledge, 1996) 2

2 – Ibid., 160

3 – Ibid., 68

4 – The designation of the ‘Mädchen aus dem Schloß’ by whom K. is captivated is reminiscent of Grosse’s Die Dame vom Schloße (in Des Grafen von Vargas Novellen, 1792).

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

Like the road to Montoni’s castle winding round the base of a mountain in The Mysteries of Udolpho, the Village has just one street twisting its way round the Castle. More to the point, however, is Schopenhauer’s ‘walking around a castle’ simile, for this village road seems never to get any nearer to, or further away from, what one may therefore be wrong in thinking of as its goal; more certainly it represents a vicious circle, leading nowhere. The ‘sense of ruined structure, lost connections, and closed routes’1 is inescapable. The obvious inference is that the Castle is the centre of the Village, and Castle and Village identical, for, as K. is told, ‘This village belongs to the Castle, anyone living or spending the night here is living or spending the night as it were in the Castle.’ That ‘as it were’ is a transparent attempt to beguile the reader. In seeking access to the Castle, K. is seeking validation of his existence, hence personal empowerment, but whereas the conventional motif of escape from the Gothic castle is about personal empowerment through liberation, K., as his creator’s surrogate, seeks, at least subconsciously, the empowerment that comes from knowledge and above all from self-knowledge. The Castle is the symbol both of everything he seeks and of all that prevents him from attaining it; it is the citadel of the self from which he is alienated by radical self-doubt and therefore the very reification of the ambiguity in which Gothic is clothed.

1 – Virginia Hyde, ‘From the “Last Judgment” to Kafka’s World: A Study in Gothic Iconography’, in The Gothic Imagination: Essays in Dark Romanticism, ed. G. R. Thompson (Washington State University Press, 1974) 134

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

Apparition-like in being now there, now not there, and in presenting now one face and now another, this Castle marks the ascendancy of the irrational over the rational, of dream over ‘reality’, of dream logic over what normally passes for logic. In all of this it may be thought to symbolize the ascendancy of the Gothic. It represents what ought to be order, yet is not, and is haunted by figures, foremost among them Klamm, who seem to represent order in K.’s mind, but are in truth merely phantoms representing his mind’s disorder. Although these figures exist only as figments of his imaginative fears, those fears are so strong that it could be argued from this point of view too that K. is all the time within the limits of his own castle. In being unable to escape from his obsession with the Castle, K. is symbolically trapped within it, both insofar as it represents a fixation on his part and insofar as it is at the same time the embodiment of those negative attributes of fear and doubt that lie behind that fixation and prevent him from escaping from it. That the Castle lacks not only the ‘gate, whose portals were terrible even in ruins’ of Gothic convention, but any door as such, again brings it close to the enchanted castle of fairytale.1 In terms of Gothic convention, it is the ‘massive inaccessibility’ of the Castle that is its most Gothic feature, for here indeed the self is blocked off from something to which by reason it ought to have access.2 That something is itself. Whether the process is defined in the positive terms of achieving individuation or the negative ones of escaping from a state of alienation ultimately makes no difference, for there is no way of reaching either goal. Either way the key to the Castle is a magic that no longer exists, a serenity that K. so signally lacks.

1 – It is the symbolic opposite of the Hotel Occidental in Amerika (to which it is linked via the name of its owner, Count Westwest) with its myriad doors.

2 – Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, The Coherence of Gothic Conventions (New York: Arno Press, 1980, repr. London: Methuen, 1986) 12f.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

Like the Castle of Otranto in Walpole’s Gothic folly, Castle Westwest is the controlling fiction of The Castle. It governs the protagonist’s every act; his mind is haunted by it. Indeed, what Frank has written of the Gothic castle as such—‘The Gothic castle itself becomes the novel’s principal character, a superhuman personality. The Gothic building possesses the human characters, surrounds them with identity crises, and the castle becomes a metaphoric embodiment of the precarious structure of the mind.’1— is arguably more applicable to Kafka’s Castle than to the castles of early Gothic. The point, first made by Montague Summers,2 has been glossed by Michael Aguirre in words that could be a description of Kafka’s Castle and indeed of Pollunder’s country house: ‘The Gothic castle is ‘alive’ with a power that perplexes its inhabitants or visitors. It tends to have an irregular, asymmetrical shape; its geometry is uncanny, whether because of an actual distortion of the whole or because part of it remains unknown. This distortion yields mystery, precludes human control.’3 Kafka’s Castle has many Gothic features, but the comparison with Castle Dracula shows that it is only partly Gothic. In some ways it has more in common with Shelley’s air-built castles, and with Bunyan’s Doubting Castle, than with any ostensibly more solid Gothic edifices.

1 – Frederick S. Frank, The First Gothics (New York & London: Garland, 1987), xxiiif.

2 – Montague Summers, The Gothic Quest (New York: Russell & Russell, 1964) 410

3 – Manuel Aguirre, The Closed Space: Horror Literature and Western Symbolism (Manchester University Press, 1990) 92

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

That K. first sees the castle ‘in the air’ is a sure indication that it is an ‘airy fabric of fancy’,1 as unreal as every such edifice, but at the same time as real, and, to K., as psychologically necessary, as every obsession. The Castle is Klam(m). Haunted by the idea of the mysterious Klamm and increasingly identified with him, it is an example of ‘sacred space’, that is, space set aside for encounters of the mystical kind, encounters with the mysterium tremendum, the presence of which appears to be suggested by a strange, unearthly humming on the telephone line.2 K. receives two mysterious messages purporting to come from Klamm, but the ‘K’ with which they are signed, aping his own initial, is close enough to ‘X’, the sign of the unknown, to aggravate the doubt in his mind. He may appear to see Klamm when he peers through the keyhole, but his eyes deceive him into ‘seeing’ what he wants to see; what he cannot see is how his own mind is deluding him. Klamm is the equivalent of the Castle: both he and it exist only in the sense of being figments of K.’s imagination. In Gothic and in The Castle there is a similar underlying question: Are apparitions ‘real’, or are they projections of a psychic disturbance in those to whom they manifest themselves? Klamm may be defined in many ways. Thus he is:

– a ghostly apparition haunting the ‘Castle’ in K.’s mind, no more real than the average Gothic ghost, yet as real as every fixation or figure of nightmare;

– K.’s diametrically opposed alter ego, but also his super-ego, for he is empowered in the way in which K. would be empowered, the very embodiment of everything K. lacks and for which he searches in vain;

– K.’s devil or Gothic lower self, his id or shadow, and as such the embodiment of all that prevents him from attaining what he seeks.

1 – Charles Maturin, Fatal Revenge (Far Thrupp: Alan Sutton, 1994) 4

2 – Although this could equally well be a fault on the line or a matter of K. ‘hearing things’ as the labyrinth of the inner ear misleads him, or part of the web of misunderstanding that is so sedulously spun round the reader.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

It is the fact that The Castle closely resembles the typical Gothic ‘demonic quest-romance, in which a lonely, self-divided hero embarks on insane pursuit of the Absolute’,1 that has spawned so many religious misinterpretations of the novel. In truth the Castle represents not only the absolute certainty that K. seeks, which in the end turns out to be a deadly truism, but also the absolute uncertainty by which he is possessed. Insofar as Klamm is the Castle, he must also be Graf Westwest. Insofar as he is the Castle, he must also be K., in whose mind alone the castle exists. In the manuscript of the novel Kafka, on several occasions, wrote KIa’s instead of K.’s; while obviously a mistake, it reveals the secret identity of K. and Klamm, who is described as the head of Department X of the Castle, and as such the very source and quasi-guarantor of the certainty that K. seeks. This department is a mysterious one, for X is, in Roman numerals, the sign of the unknown, suggesting that Klamm represents the unknown and indeed the unknowable. The very fact that Klamm’s name is Delusion means that the certainty that K. thinks he could obtain from Klamm is itself an illusion.

1 – G. R. Thompson in The Gothic Imagination: Essays in Dark Romanticism, ed. G. R. Thompson (Washington State University Press, 1974) 2

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

Klamm is an obsession based on Angst, the fear of insignificance, of life, of death. Even so he is an ambiguous figure: does he signify that it is a delusion on K.’s part to think that he can find the meaning of his existence anywhere except within himself? Or that his life has no given meaning, and therefore no meaning whatsoever? The former meaning is certain; the latter cannot be discounted. K. thinks he has been appointed land-surveyor, but in truth he has not, and the reality/unreality of Klamm and Castle alike follow from that initial misapprehension. Besides, what is ‘reality’? Was it not above all in his preoccupation with precisely that question that Kafka revealed his kinship with Hoffmann and the proximity of his work to the fairytale? The meaning of the illusory figure of Klamm in K.’s mind resides in his ambiguity. On the one hand he is an inscrutably patriarchal, even divine-seeming figure, K.’s ‘god’, though more a deus absconditus than a real presence; on the other he is even more clearly K.’s personal devil or demon, for it is a diabolical notion that one should go outside oneself for what can only be found within oneself or not at all. The Devil, be it remembered, was believed to be able to assume any form in order to lure human beings on to self-deception and thence to self-destruction. It is only in his negative guise of K.’s devil that Klamm has anything to offer K., and that is simply the certainty of uncertainty, a diabolical, self-deceiving protraction of the situation and state in which K. has found himself since crossing that fateful bridge on the first page of the novel, precisely the state with which Josef K. was unable to live.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

Kafka’s Castle is naturally more complex than its remote historical precursor, the Castle of Otranto, for it exists only in K.’s mind and is accordingly as much his construct as he is its. It is the Other to which K. cannot attain because he is already effectively imprisoned within it in the guise of his alienated, self-doubting self. The Castle is about self-image and therefore, like so much of Kafka’s work—and so much of Gothic (including Dostoevsky)—about identity, notably the identity of the man who has no raison d’être and therefore no self-respect. But it is also about the identity of the author, who, as a writer (‘surveyor’) surveying his life’s work, fears that his judgments may be misjudgments and his works mere hollow constructs. That these are Gothic themes is shown by The Devil’s Elixirs, although the fact must not blind us to the many significant differences between Kafka’s novels and Hoffmann’s most powerful and most Gothic work, not least among them the fact that at the end of The Devil’s Elixirs Medardus has risen above what he was at the beginning of the novel, whereas at the end of Kafka’s novels the protagonist has signally failed to do so.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

The Castle is in line with Gothic convention at its most cerebrally refined in including within the narrative an inset novella or story-within-a story-within-a story à la Maturin. Within the main narrative is the story of Barnabas and his family, and within that the story first of the fire brigade fête, and then of Amalia’s Secret and Fall. The first of these is a fascinating, somewhat over-determined interlude. It is the story, again a parable, of the fire brigade fête on 3rd July, Kafka’s birthday.1 At this ceremony Castle and Village come together for the first and last time in the novel. The symbolic season is summer, the setting a riverside meadow outside the Village which contrasts so strongly with the wintry wilderness that is, otherwise, all that K. knows in the seven days of this reverse Creation, as to appear positively paradisal. That is the whole point. The meadow here stands for Eden (Canaan, the promised land), the river is the river Pishon (Gen. II, 11); the ‘Spritze’, now a phallic symbol symbolizing Sortini’s lust, is the Serpent, for although Amalia does not succumb to Sortini, she does eat of the tree of knowledge: her eyes are opened and she knows good and evil.

1 – The occasion was to be marked by the ‘Übergabe der neuen Spritze’ (literally, the handing over of a new fire engine or hose; but what no translation can ever reveal is the fact that ‘Spritze’ is a slang term for a girl, so that it also refers to the demanded handing over of Amalia to Sortini.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

If the setting of this ceremony is reminiscent of the Paradise myth in Genesis, it has further points in common with another form of the myth in Ezekiel,1 viz. the ‘stones of fire’ (cf. the fireworks here), the music of tabrets and pipes (cf. the trumpets here), and the precious stones of the iniquitous Tyre (cf. Amalia’s garnet necklace, by which Sortini is attracted, and all the discussion of the iniquity involved). There is plenty of evidence that the meadow beside the river outside the village represents a symbolic Paradise that is about to be lost, for the scene is reminiscent not only of the Fall of Man, but of the Apocalypse and the Fall of Babylon, with the fire engine as the ‘great red dragon’ and the trumpets as the seven trumps of doom. The latter, presented to the fire brigade by the Castle, are stressed by Olga, who is telling the story. She speaks of the ‘entsetzlicher Larm’ they make, the word ‘entsetzlich’ (figuratively, horrible [din]; but literally, lawless, contrary to the Law) revealing Kafka’s meaning. He hated noise, which he thought of as ‘wüster Larm’ (terrible din; but wüst also means licentious). The noise here therefore connotes Wüstheit (licentiousness), and is such that one would have thought the Turks had arrived, although even the Turks are not unambiguous, for the word ‘Türken’ implies, by extension, that the episode is made up (einen Türken bauen means to concoct a cock-and-bull story). The typical subjunctive formulation, on the other hand, means that the Turks2 are symbolically present in the hordes of licentious Castle-servants, previously identified as demons.

1 – XXVIII 12-19

2 – Who occupied and traumatized part of Austro-Hungary in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

The scene is reminiscent of the one that greeted Karl Rossmann in the Nature Theatre, when he tried out the tune of a drinking-song on Fanny’s trumpet. The trumpets in the Nature Theatre produced, alternately, angelic and satanic sounds; those presented to the local fire-brigade by the ‘Castle’ produce similar sounds, ecstatic yet satanic. It is an appropriately ambiguous sound to be heard in this re-enactment of the Fall and ritual celebration of the Castle Mysteries which makes it as clear as may be that the subject is again original sin or the corruption of Man, the theme of many an earlier Gothic interlude. It was shortly after this that Sortini (an alias of Klamm) showed himself in his true colours when he jumped over (‘sprang über’) the shaft of the (horse-drawn) fire-engine. The reader cannot afford to overlook (überspringen) the significance of the episode (‘Deichsel’, shaft → Deixel, Devil). Kafka even has Sortini sit on the shaft in order to show, in the manner of dreams, that he is the devil in question.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

The story of Amalia’s Secret is, on one level, an elaborate story of transgression with a difference, in that the real transgression is not the one for which Amalia’s father wishes to accept the blame, but a transgression against Amalia: a gross abuse of power on the part of the ambiguously named Sortini (alias Sordini), who seems a pretty conventional Gothic villain in the mould of Radcliffe’s Schedoni in using his arbitrary patriarchal power in an attempt to possess himself of the courageous Amalia. When interiorized, however, the story is a study of guilty conscience, in which what counts is not the fact but the sense of guilt. Each of Kafka’s novels has its figure of the almost obligatory Italian of Gothic convention,1 but Kafka again (assuming his awareness of it) puts a spin on the convention by ostensibly making Olga, whose name means that she is to be seen as saintly for giving herself to the Castle menials, into the heroine of the story, which relates to the main narrative as the Parable of the Doorkeeper did in The Trial. Olga’s story is indeed relevant to that parable. Josef K., in The Trial, is unable to prove his innocence because he is guilty; Amalia’s father, for his part, is unable to prove his guilt because he is innocent. In his prime he once carried Galater out of the blazing Herrenhof at a run.2

1 – Giacomo; the Italian; Sortini/Sordini, Vallabene.

2 – Cf. the Devil as strong man; insofar as Galater is another alias of Klamm/Sortini, and therefore of the Devil, his superhuman strength seems, on this occasion, to have been projected on to Amalia’s father.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

As for his daughters, they are symbolic types representing not so much the fortunes of vice and misfortunes of virtue, as the pros and cons of yielding to fate (Olga) and struggling against it (Amalia). Each is both right and wrong: the crass moral inversions of Sade are avoided, but the comparatively subtler antinomies of Gothic are still unresolved. On the face of it, they both represent the Gothic heroine suffering at the hands of a corrupt and tyrannical patriarchal power, as well as corresponding to the opposing sisters/pairs of opposites of Gothic and fairytale convention, their counterparts in the main narrative being Frieda and the ‘girl [maiden and mother] from the castle’, who in terms of aphorism 79 represent profane and sacred love respectively. However, here too there is a point beyond which the Gothic analogy ceases to apply, for the context in which the story of Amalia and Olga is told and set is Gothic only on the surface. Beneath the surface the machinery of Gothic is used to power a more individual sort of craft.

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

At the end K. was to have been told that he had not in fact been appointed land-surveyor, but was free to remain in the village until his death, which was then to have taken place. Left incomplete, though not inchoate, all three of Kafka’s novels were thus to have ended, like so many of his tales, in the final alienation of death. This, it could be argued, is their most Gothic feature of all, for the prison-house of Gothic fiction houses not only patriarchy and the self, which caused Kafka more problems than most, but, beyond that, mortality: all those ever-shrinking enclosures, physical and metaphysical alike, foreshadow that ultimate Gothic locus, the charnel house or grave, of which K. said to Frieda, in a remarkably open, Gothic-Romantic way: ‘I dream of a grave, deep and narrow, where we could clasp each other in our arms as with iron bars, and I would hide my face in you and you would hide your face in me, and nobody would ever see us any more’. The Castle therefore ends with the bottomless pit, the chaos from which the world came and to which it is now returned in what has been well called a ‘cosmogony in reverse’,1 a point which serves to underline the metaphysical weight of what, if less weighty, might well have been thought of as Kafka’s Gothic.

1 – Heinz Politzer, Franz Kafka: Parable and Paradox (Cornell University Press, 1966) 248

Michael Haneke, The Castle, Franz Kafka

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments