Fairytale Motifs – Gothic Reading – Expulsion from Eden

KAFKA: AMERIKA – ANALYSIS – PART 1

Patrick Bridgwater

From Patrick Bridgwater, Kafka, Gothic and Fairytale (Amsterdam-New York: Editions Rodopi, 2003) pp. 102-113.

I have edited the text very slightly to promote readability.

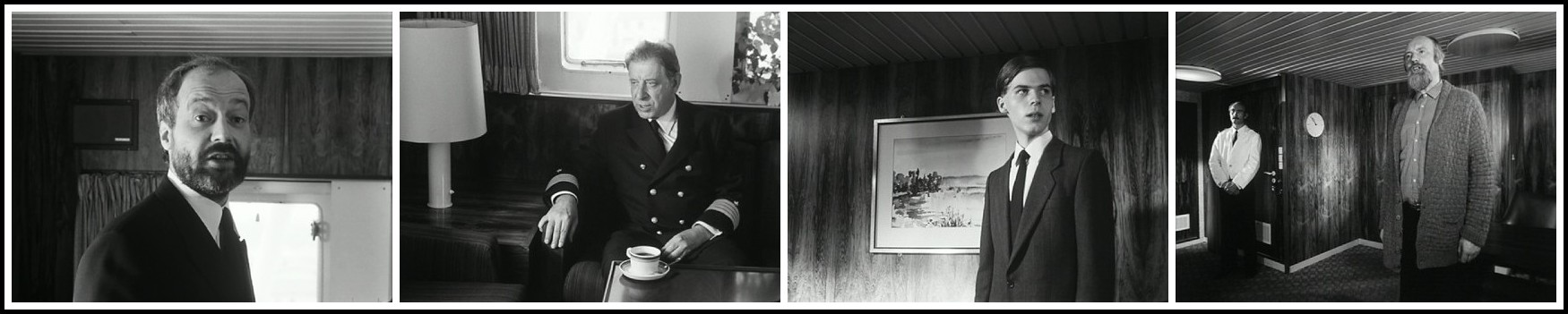

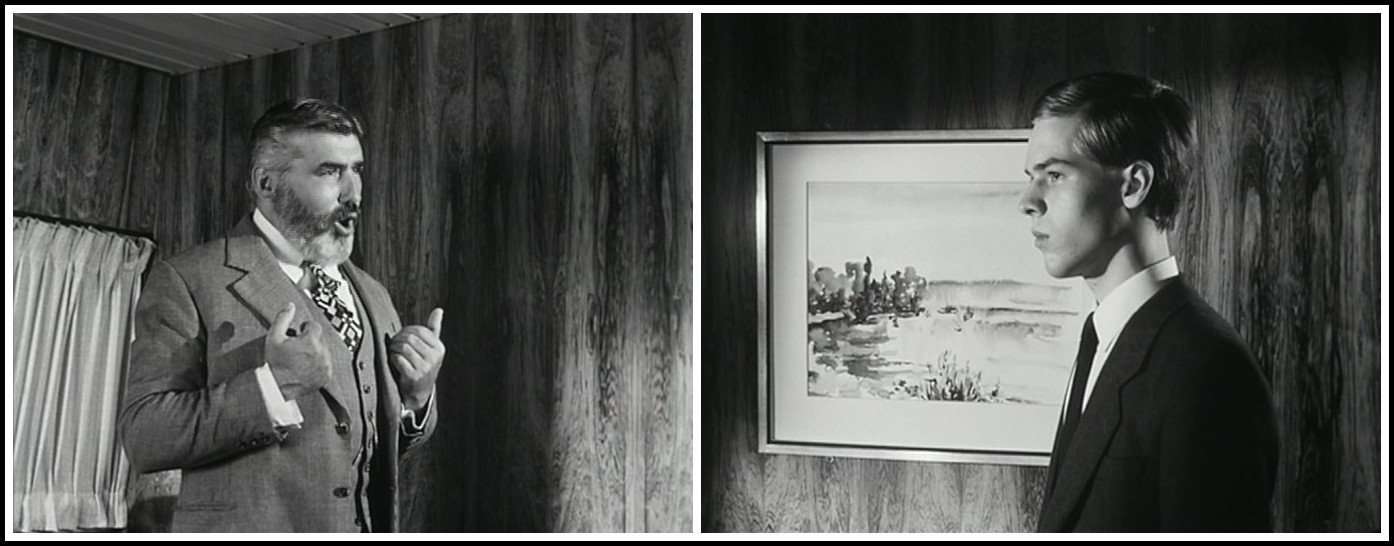

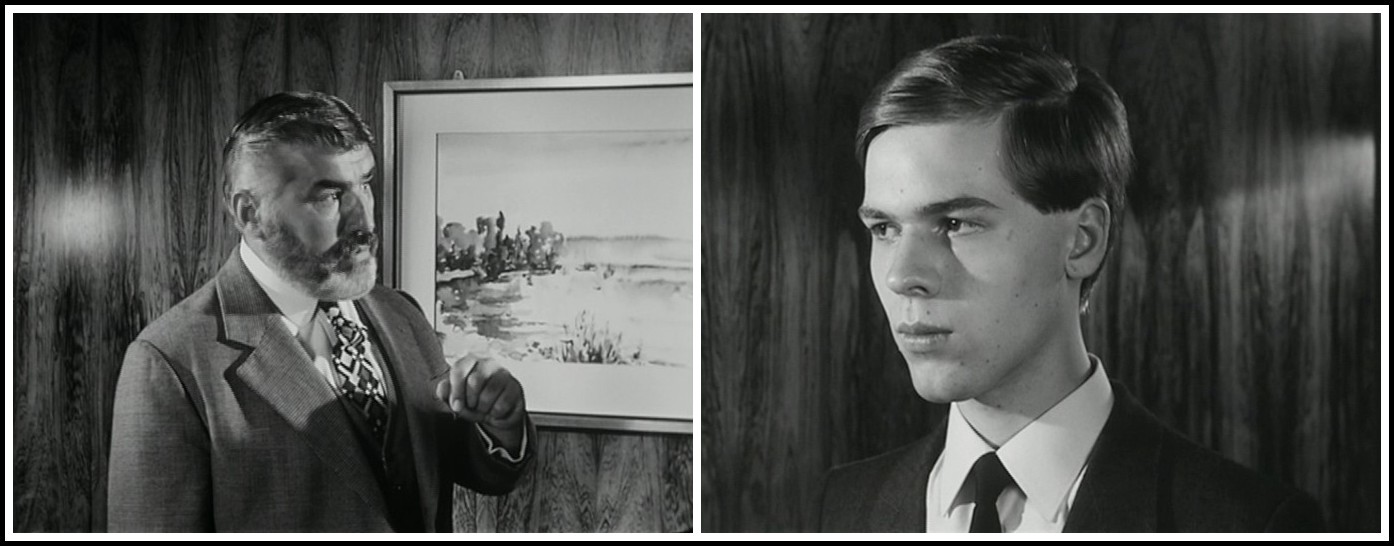

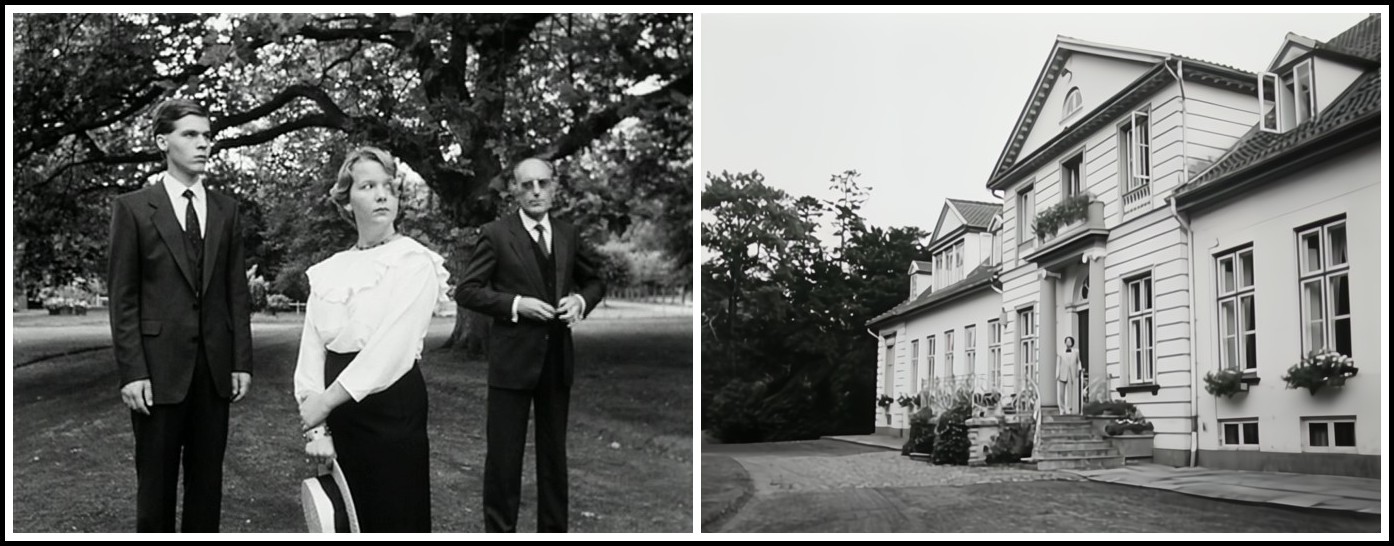

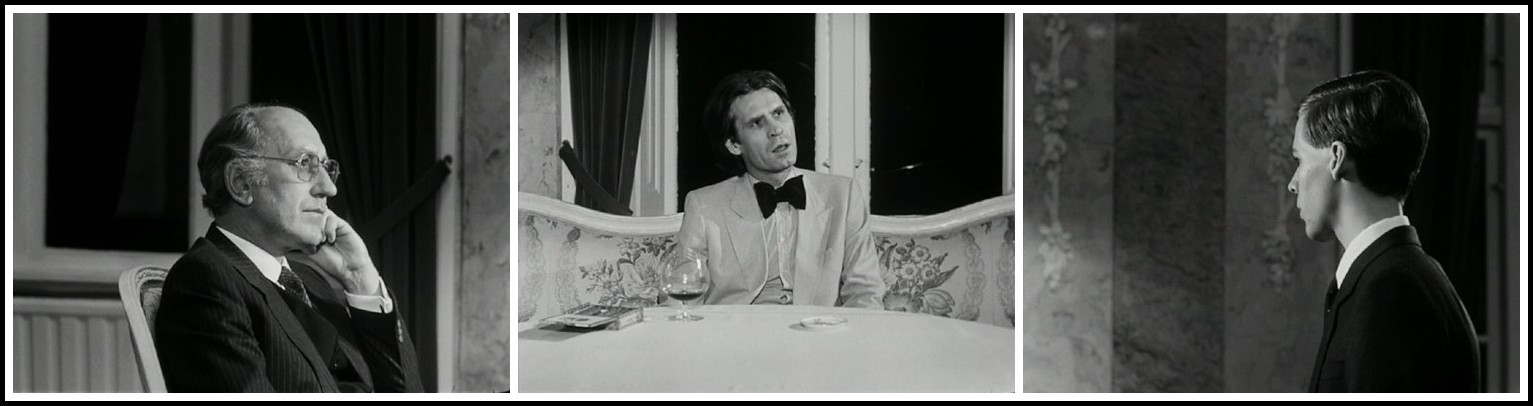

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

I. KAFKA – AMERIKA – FAIRYTALE MOTIFS

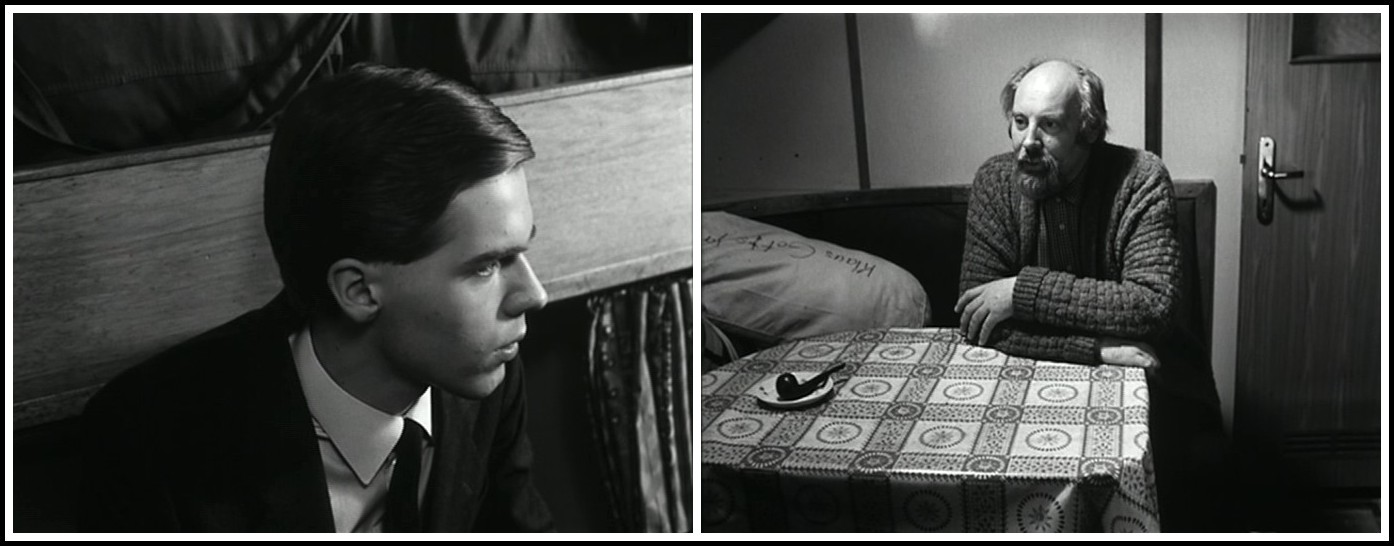

Pasley has rightly commented on the ‘quality of child-like innocence’1 informing Amerika. The ‘naive’ way in which the adult world is there presented in a pre-adult perspective is important, for it is the perspective of the fairytale, regardless of its target readership. Of the novels it is the first that is closest to fairytale in the sense of containing the greatest number of fairytale motifs and what Vladimir Propp called ‘functions’, that is, plot segments or component parts of the model tale. Of Propp’s thirty-one functions Amerika has half; to qualify as a fully-fledged fairytale it would have had to have all the functions, in the right order, but half the functions is a remarkable figure for a modern novel.

1 – In Franz Kafka, Der Heizer, In der Strafkolonie, Der Bau, ed. J.M.S. Pasley (Cambridge University Press, 1966) 9

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

Amerika embodies the constantly frustrated quest for a lost paradise that underlies all three novels and is seen at its most fairytale-like in the Parable of the Doorkeeper in The Trial. It is strikingly fairytale-like in story-line and structure. The structure of the novel is that of the classical fairytale, consisting of exposition (the crisis, outlined in the opening lines, of which Onkel Jakob gives the Captain an exposé), repeated peripeteia (shown literally as the ups and down of Karl’s experience, symbolized in his job of lift-boy), and lysis (complication and dénouement).1 The opening chapter, which sets the scene for the novel and establishes its major symbols, amounts to the fairytale formula: Once upon a time there was a young man named Karl Rossmann who was given the boot by his parents for allowing himself to be seduced by the kitchen maid. The ending of the novel, for its part, both corresponds to those of the most primitive stories, which simply peter out, and emphasizes the circular pattern of the novel, and with it the ‘weary sorrowful circle’ of existence, for the final journey replicates the initial one.

1 – See Marie Louise von Franz, III/3

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

The structural replication and symbolical re-enactments of the novel can be compared with the reprises of the folk fairytale: One and the same stylistic impulse permeates the entire folktale. From this impulse all episodes arise; it keeps on forming the same characters, so that they all resemble one another, while at the same time each stands alone. The subsequent scene resembles the preceding one so closely because it originates from the same source. In relation to each other, the two scenes are isolated, but they are formed and sustained by one and the same center.1 The structural replication in Amerika parallels the formulaic repetition of the folktale, though without running to verbal repetition. The stylistic impulse that keeps on forming the same figures (in the novel they are not ‘characters’) is clearly active in the naming of those figures. What Lüthi has written of the phenomenon of repetition and the relationship of the parts to the whole in the folk fairytale is, on the face of it, strikingly applicable to the scenes or episodes in Amerika, but there is a crucial difference between fairytale and novel in that in the novel the replication is necessitated by the idea of original sin, which it illustrates, whereas in the fairytale this is not the case.

1 – Lüthi, The European Folktale: Form and Nature, tr. J.D. Niles (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982) 50f.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

The paradise lost motif, common to myth and fairytale, involves both of Karl’s symbolical forebears, Adam and Lucifer. Banishment by the father is a common fairytale motif, as is the idea of failure or transgression leading to punishment. Karl’s banishment is clearly a punishment for breaking an unwritten and unvoiced commandment. Like fairytale, the novel teems with implicit interdictions (not to enter Johanna’s room, not to enter Klara’s room, not to enter Brunelda’s room, not to wait until a deadline has just passed before receiving Onkel Jakob’s letter, not to desert his post as liftboy, not to play a drinking song on his trumpet, and so on), the number of which serves to underline the enormity of the initial fateful transgression (dreams cannot and folk fairytales normally do not employ adverbs of degree, for which repetition stands in). Like the fairytale hero, Karl Rossmann is, following his banishment, no longer embedded in a family structure. His parents, though instigators of the plot, lack all reality; even the father, whom we assume to be the prime mover in Karl’s expulsion since all those who replicate his action are father-figures, is no more than a cipher or trigger of the action, much less real than the Captain, Onkel Jakob, and the Head Porter, all three of whom substitute for him, although Karl’s real Schädiger (evil genius) is his own id or shadow.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

If the story of Karl’s seduction by Johanna Brummer (the ‘false bride’ of fairytale) is also as it were a looking-glass or reverse-gender version of ‘La belle et la bête’, the ‘discovery of the rich uncle (who subsequently rejects Karl, like Cinderella, for failing to return by midnight) is a pure fairy-tale motif.1 Karl, as seduced rather than seducer, is appropriately seen as a reverse-gender Cinderella, this then being acted out in his pursuit by Klara (another fairytale motif), which necessarily also involves gender-reversal since it symbolizes his original pursuit and entrapment by Johanna. It is likely that this is another example of his subversion (reversal) of fairytale motifs. In terms of the novel, Klara is an avatar of Johanna; in fairytale terms she is the ‘beautiful daughter of the task-setting demon’—her father—who was responsible for Karl’s failure to return by midnight. As in tales of the ‘Amor and Psyche’ type, the deadline set (in our case, unbeknown to the protagonist) is just missed; typically, the novel lacks the second part, in which this is made good.

1 – In Franz Kafka, Der Heizer, In der Strafkolonie, Der Bau, ed. J.M.S. Pasley (Cambridge University Press, 1966) 11

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

If the discovery of the rich uncle is ‘sheer fairytale’ in the sense of being too good to be true, precisely the sort of thing that, according to Kafka, does not happen in real life, at least not nowadays the expulsion of Karl is as final and fatal as such negative outcomes always are. The ‘Head Porter’ at the Hotel Occidental, instead of preventing Karl from entering, ironically does all he can to prevent him from leaving, a Gothic reversal of the usual fairytale and mythological motif. In Amerika a spin is put on the violation-of-a-prohibition motif that is basic to fairytale in that Karl twice breaks a prohibition of which he had not been specifically aware; the third occasion is different (‘Being absent from duty without leave spells dismissal’) and, reversing fairytale convention, fatal.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

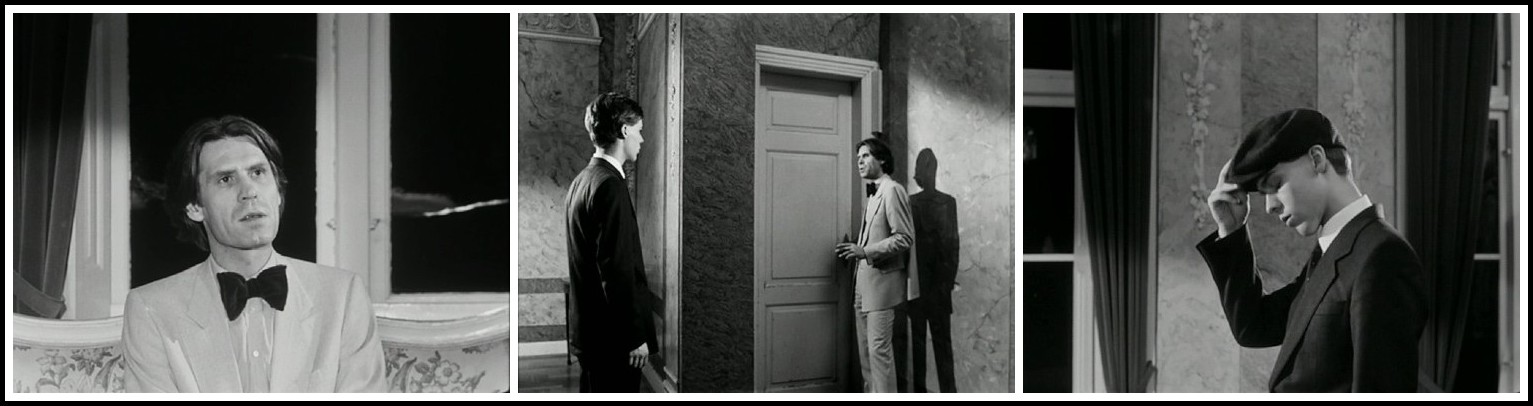

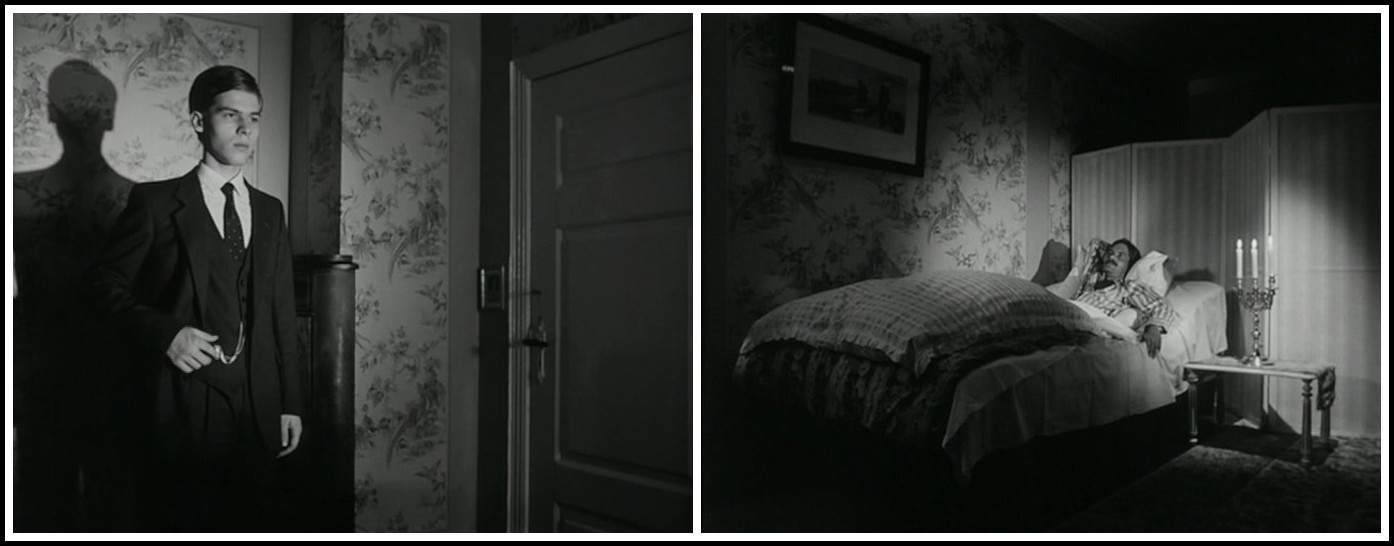

The forbidden door/chamber is another major fairytale motif, notably in the form of the motif of desired knowledge hidden behind a locked door. In the Grimms’ The Frog Prince’ it has the same Freudian connotation as in Amerika, whereas in the two K.-novels it appears, more literally, as the portal-motif of fantasy. In the present novel the ‘chamber of horrors’ is subverted in two ways: in that Karl was locked into the original chamber, his escape from which is re-enacted together with his expulsion, and in that it gives way to a positive ‘theology of the door’. In other words, Kafka reverses fairytale/Gothic motifs regardless of whether their original meaning was positive or negative. Subversion, it seems, is all.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

Pollunder, Robinson and Delamarche correspond to the robbers of fairytale and banditti of Gothic, the first two being identified as such by their names. The small inn, in which Karl falls in with Robinson and Delamarche is equivalent to the robbers’ den of both traditions. Grimm’s Thumbling (≈ Tom Thumb) is invited to become chief of banditti. Karl Rossmann, though ostensibly more robbed than robbing, is in an analogous position. Grete Mitzelbach, who is said to have worked at the ‘Golden Goose’ in Prague, plays the symbolical part of the ‘fairy godmother’, but is unable to save Karl. This part of the narrative also proving to be too good to last, a mere ‘fairytale’, Karl’s expulsion has to be re-enacted again, but not before he receives a gift appropriate to fairytale.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

The biblical and folkloric motif of the giving of an apple (by Eve to Adam, a reverse-gender version of Dionysos’s gift to Aphrodite) is duplicated in fairytale in the form of an ugly old woman (witch) giving a poisoned apple, which, like the philtre of Gothic, induces death-like sleep. This motif, which appears in ‘Snow White’, reappears shortly afterwards in Hoffmann’s The Golden Pot, and then in an apparently harmless, heavily censored form in Amerika, where it (appropriately, given the Freudian association of the apple with the vulva) constitutes a censored version of Johanna Brummer’s ‘gift’ to Karl, to which the account of Therese’s mother’s death also alludes. Karl’s three visits to Therese’s room, like the three enactments of his expulsion from paradise, involve the magic number so common in folktale, but without the positive outcome normally associated with the motif, the significance of which is here reversed. The dumping of Brunelda, the biblical Scarlet Woman and ‘giantess in a red dress’ of Icelandic fairytale, involves, as we have already seen, a reversal of the leitmotif of Musäus’s ‘The Abduction from the Seraglio’. There are also many allusive fairytale details (Green as ogre and, in symbolical terms, cannibal; Robinson as Schädiger; the dogs with their ‘great bounds’; the ‘old hag’; etc.).

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

Searching for a prize is a classical fairytale motif. In two of Kafka’s three novels the protagonist (Karl Rossmann, K.) goes out into the world like the wanderer-hero of fairytale, to seek his fortune, finding there not what he seeks, but what he deserves to find. Amerika is a Bildungsroman of sorts, in which a naive young man learns the facts of life and the world. The motifs of the ‘right way’ and the ‘wrong way’ or ‘false path’ being as central to fairytale as they are to Kafka’s work, the straight and narrow path that Karl Rossmann tries to tread corresponds to that trodden by the fairytale hero. In Kafka, as we have seen, there is no stroke of luck at the third attempt by which the fairytale hero may escape or recover, and neither does Kafka subscribe to the fairytale idea of rescue at the eleventh hour; with Kafka the eleventh hour is axiomatically too late. The vicious cycle of events in Amerika is thus reminiscent alike of fairytale and nightmare. America was to Kafka’s generation an enchanted land of boundless possibility, but Karl Rossmann’s experience of it is totally different, not least because his ‘America’ is so far from being what it seems to be. There is just enough of the real America in the mid-nineteenth century to put our model unwary reader off the scent, while the Cinderella motif, for its part, makes the reader expect a fairytale ending. Since this cannot be delivered, the reiterated Fall is accompanied by a reiterated disenchantment, the effect on the reader cumulative, each disappointment, to borrow a fairytale motif, more bitter than the one before.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

Just as Amerika as a whole takes the reader back to the German Utopian novel of c. 1800, only to disappoint any hopes that it too may be Utopian, so too does Kafka, in deploying fairytale motifs, trigger certain expectations in the reader which he then proceeds to dash, by reversing and subverting them, and by filling his mock-fairytale structure with an admixture of ‘Gothic’ motifs. It is the tension between fairytale wish-fulfilment on one hand and Gothic reality on the other that makes this first novel so remarkable.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

II. KAFKA – AMERIKA – GOTHIC READING – EXPULSION FROM EDEN

‘Der Verschollene’ [the German title of the novel] means ‘the man who went missing’ and ‘the man who went to the Devil’, but it also has a stronger, legal meaning, which is the key to the novel. Kafka, who had a degree in law and worked in a quasi-legal profession, would not have used a legal term unless he was absolutely satisfied as to its meaning and implications; he went to endless trouble to get words and phrases exactly right, and evinced the greatest skill in doing so. In legal German, jemanden für verschollen erklären means ‘to declare someone dead in law’. The implication is that the novel was to have ended in Karl’s virtual death, so that an optimistic reading, always impossible if the reading was a close one, seems to be out of the question. The title confirms what Kafka once said, that Karl Rossmann, though ‘guiltless’, was, by way of punishment for his sinfulness, to be brushed aside, as happens literally to Gregor Samsa’s remains in ‘The Metamorphosis’.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

If this sounds Draconian, it is even more so when one realizes that the novel shows Kafka pondering his own largely imaginary sexual initiation, greatly exaggerated by poetic licence, hence his reported description of ‘The Stoker’ as ‘the memory of a dream, of something that perhaps never took place’, and condemning himself for his role in it. This first novel is therefore Gothic not merely in its spaces and many of its situations, but as a whole, for Karl Rossmann was to be contemptuously swept aside by patriarchy militant. The structure is not only mock-fairytale, but distinctly Gothic, and beneath the Gothic and fairytale elements lies patriarchy’s ultimate model, the Old Testament. For all its motley, the novel is as much a punitive fantasy as The Trial. As such, it has much more to do with the newly created, newly transgressive world of Genesis than with the New World of America, which is a Kafkaesque literal symbol.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

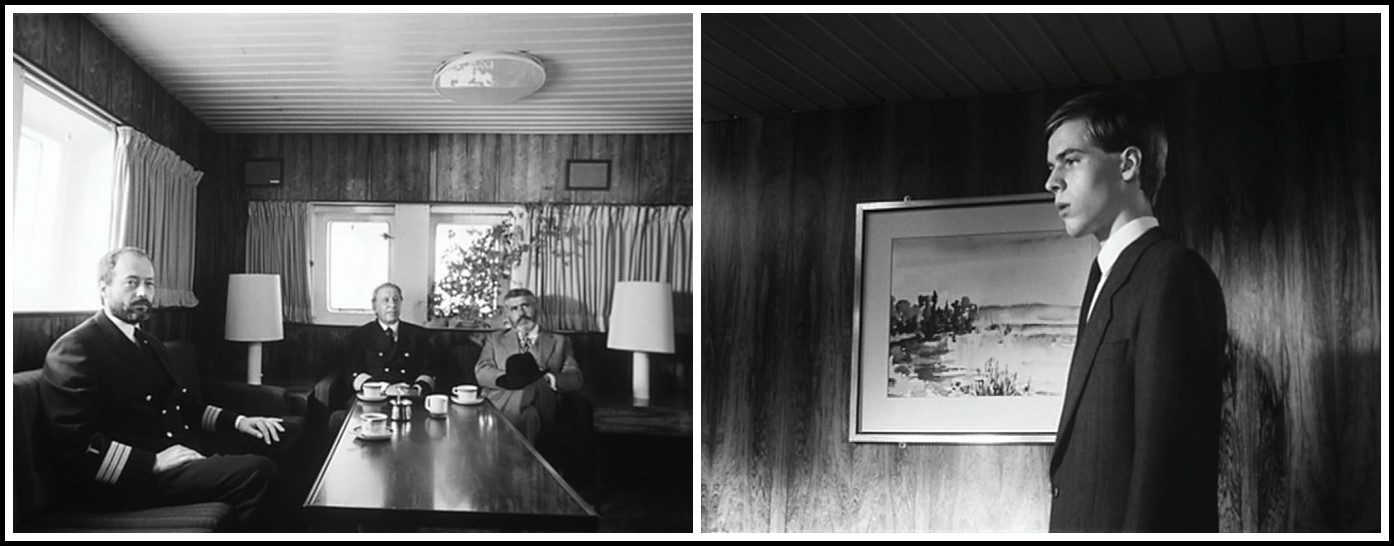

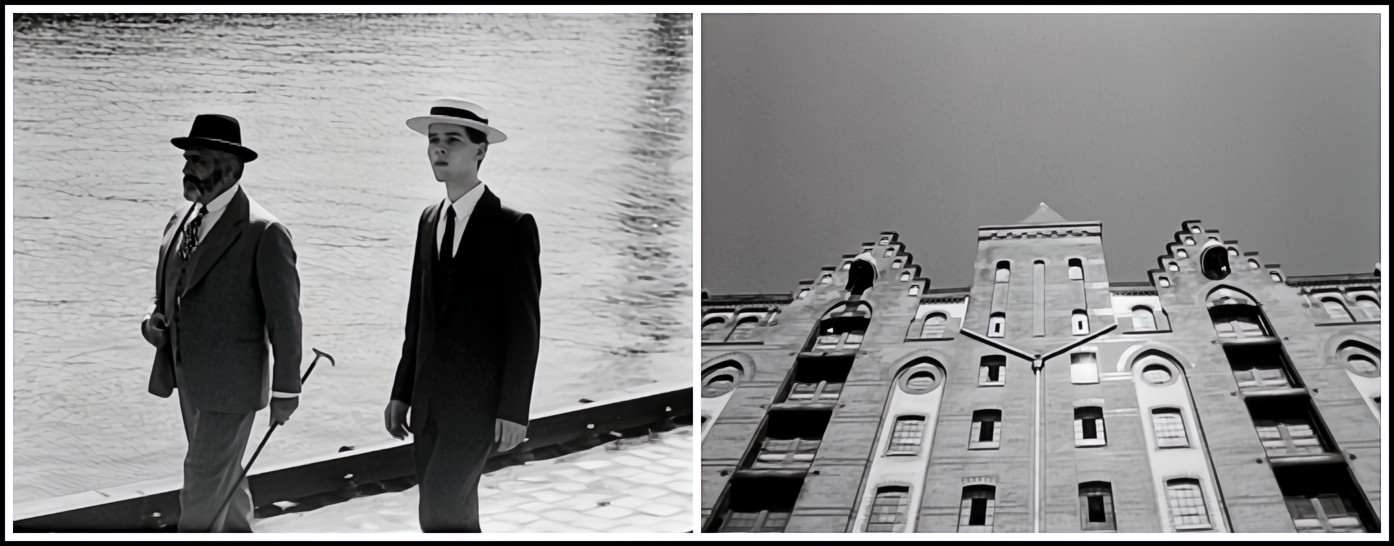

It is the key first chapter, centering on Karl’s transgression, that immediately reveals this ostensible ‘fairytale novel’ to be a Gothic novel in disguise. The sword held aloft by the Statue of ‘Liberty’ shows that Karl, entering the ‘new world’, has not escaped from the patriarchal law of the old world and the violence associated with it, which also surfaces in the no less symbolical sword worn by an immigration official. The Statue of Liberty has been replaced not merely by a menacing figure in the posture of Christ in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, right arm held aloft ready to pronounce judgment, but by one apparently ready to put mankind (for Karl Rossmann is also an Everyman figure) to the sword. A notably eschatological opening image for a novel that has, incredibly, been seen as optimistic and realistic, it goes back to a gesture used by Kafka’s father at his most forbidding and to the arms of the city of Prague and its Gothic past. It is in itself sufficient to show that Karl, far from entering a paradise, is trapped in a past that is no longer his now that he has been disinherited. The statue with the raised sword also shows that, having lost his innocence, he will be unable to regain it. Having been expelled from paradise, he will be unable to return there, the way to it being barred by the ‘flaming sword’ (Gen. III, 24) ‘at the East of the Garden of Eden’, for which the sword in the present context also stands.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

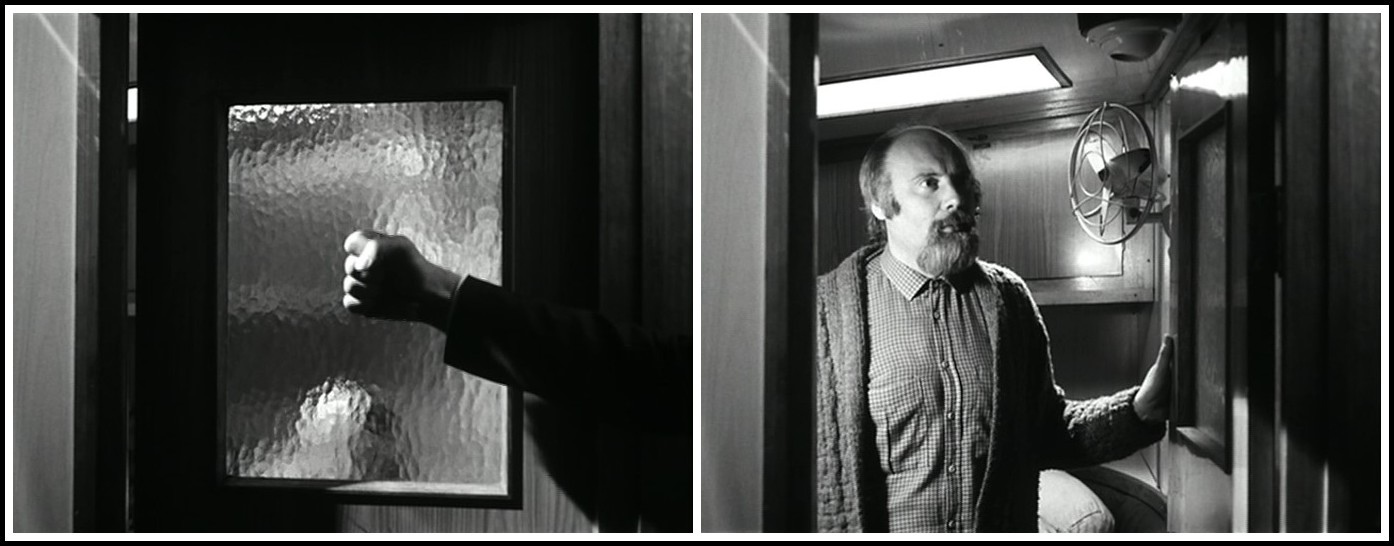

Since, according to the biblical and fairytale model that Kafka is following, one sin is decisive, Karl’s transgression constitutes a perpetual barrier to paradise. Having fallen, he can by definition only continue to fall. There is no going back to a status quo ante. That Karl is more sinned against than sinning makes no difference, for Johanna Brummer is, on one symbolical reading, a projection of his own ‘monstrous’ sexuality. The whole novel turns on Karl’s transgression. He may be a Gothic child of misfortune, burdened with an unhappy secret, and presumptuous to boot, but above all he is, in his half-innocent way, guilty not only of revolt against the patriarchal principles personified by Onkel Jakob and Head Porter Feodor, but, worse, of ‘uncleanness’. This sense of uncleanness is the ultimate reason for the fact that there are ritual lustration scenes in two of the three novels, washing in one form or another being involved in all three. As in the following novel, the tribunal before which the protagonist is repeatedly summoned is at bottom the court of his own conscience, but as yet Kafka’s symbolical method is not sufficiently developed for this to be reified in the form of a tribunal, although he comes close to it in the Captain’s cabin.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

The first chapter, published independently in 1913 as ‘The Stoker’, is the key to the novel in that the event related there in an inset tale—the sixteen-year-old Karl Rossmann’s seduction by the family maid, Johanna Brummer, and subsequent expulsion from his childhood ‘paradise’ in a re-enactment of the Fall—provides the model on which the other chapters of the novel are more or less ‘censored’ variations that show Karl trying to come to terms with what has happened. Read thus, Amerika centres on ‘the mythic expulsion of man from Eden’ and is therefore an exemplary Gothic novel, for the Gothic tradition replays with almost infinite variations the myths both of the temptation and fall in Eden and of the perilous experience of the post-lapsarian wilderness. The fruit consumed in Eden turns to poison, withering humanity’s world into one of suffering and death rather than opening it into the bloom of divine infinity Satan had promised.1 ‘America’ stands for the post-lapsarian wilderness, but also for the false paradise of fairytale and medieval (‘Gothic’) literary convention.

1 – Stephen Behrendt, in his Introduction to Shelley’s Zastrozzi and St Irvyne (Oxford University Press, 1986), xiv

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

Karl Rossmann’s first name both places him in relationship to Kafka, whose initial it echoes, and indicates that he is an Everyman figure1, while his surname refers to ‘riding’ in the Freudian sense, that is, to the traumatic riding lesson he had from the she-devil Johanna Brummer when he lost control.2 In a characteristic way Kafka slips in the key: Reiten als blosses Vergnügen means ‘riding as sheer pleasure’, the implication being, since bloss also means naked, that it is sexual pleasure that is in question. The phrase die primitivsten Vorübungen des Reitens, ‘the most rudimentary preliminaries to riding’, refers to Karl’s seduction. There is reason to think that Freud was on Kafka’s mind as he wrote his first novel.

1 – Karl = Kerl, man

2 – Cf. the phrase ihn reitet der Teufel [die Teufelin], ‘he lacks self-control’, literally: ‘he is ridden by the Devil [a She-Devil]’), which is a fair description of the seduction.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

The latent symbolism involved in Rossmann’s name can perhaps best be revealed by considering it in conjunction with the story ‘A Country Doctor’, in which the horse symbolism is more fully developed. The horses there represent the ‘nightmare visitor’ or night-fiend1, who drives them,2 but also those fiends in human guise, the doctor and his groom, the latter representing the doctor’s id, thereby revealing his hitherto repressed attitude towards Rosa. That all these guises are disguises underlines the structural role of disguise in Amerika. The horses appear as if by magic when the doctor needs them, but the magic is dubious, for it leaves the erstwhile country doctor reduced to an accursed-wanderer figure. There are two sides to the doctor: the quasi-sacerdotal figure and the repressed sex-fiend. In his study of nightmare, Ernest Jones considers ‘The Horse and the Night-Fiend’ at length, and the link between riding and coitus (of which Kafka had a positively Gothic horror) was made as long ago as 1872. So far as Rossmann’s name is concerned, it is the closely related sexual and diabolical connotations that need to be borne in mind, together with the fact that the name contains a hidden allusion to and identification with Kafka: in both German and Czech there is a verbal bridge between the black horse (and therefore the Devil) and Kafka’s name. Amerika has more hidden autobiographical significance than has hitherto been suspected.

1 – Ultimately the Devil, who in folklore is given to appearing in the guise of a horse, as riding a black horse, as driving a pair of black horses, and so on.

2 – Appropriate in that the story discloses a series of nightmare situations.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

Much the same symbolism is involved in Karl’s piano-playing, which has an equally clear sexual connotation: Freud argued that musical scales are a form of step, so that the symbolism of ‘mounting’ applies, with every step a gradus ad Parnassum. Mak, who links Karl’s piano-playing with his riding-lessons (and their meaning) by describing it as ‘amateurish’ and ‘very primitive’, clearly represents Karl’s super-ego: he is the libertine that Karl accuses himself of being, and the accomplished libertine that on a subconscious level he would like to be. In this extraordinary, heavily over-determined dream-scene we see sex, which has already damned Karl for ever and which even now he puts before conscience (Green), enthroned in all its glory in Mak’s subverted Gothic chapel of a bedroom. Having once succumbed, his self-image as a Lothario, hence his subsequent employment as lift-boy, in which he spends hours on end practising gallantry (or, better, chasing women in a cell-like space reminiscent of Johanna’s bedroom, is fixed. If Karl is nonetheless more hunted than hunter, his successors Josef K. and K. are seen as womanizers, from which it is, in German, but a short step to the idea of the witch-hunt. In the present context man is seen, in biblical-patriarchal terms, as the victim of woman, of an act of entrapment or engulfment. Gender roles, and with them readers’ expectations, are reversed. Johanna Brummer, the first in a series of phallic females in these novels, is also the first to be specifically likened to a witch. Like her grotesque avatar, Brunelda, she is a caricature of the Gothic enchantress (the false bride of fairytale), her bedroom a travesty of the enchantress’s bower.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

In this novel, as in the next, there is no escaping the idea of incarceration: one of the meanings of the verb brummen is ‘to do time’. Brummer also points forward to Brunelda in two different ways: firstly, in that ‘Brummer’ also means a ‘bad singer’, and Brunelda is both bad and a singer, and secondly in that Brunelda is also a ‘Brummer’ in the sense of ‘something large, fat and ponderous’. As if these meanings were not enough, the word ‘Brummer’ also refers to an insect that makes a rattling noise as it flies, notably a beetle; in this sense Brummer links with ‘The Metamorphosis’, and suggests, by backward association, that Gregor Samsa’s beetle-form may be connected with his past licentiousness, a meaning which is supported by the ‘comfort’ he derives from pressing himself against the picture of the woman muffled in furs in a way that corresponds to Johanna’s action in pressing her ‘naked belly’ against Karl’s. The word decken, which Gregor enacts, means ‘to cover’ and ‘to serve’ in the sense of a stallion serving a mare, which completes another circle of meaning. A third link between Amerika and ‘The Metamorphosis’, as well as being a link between these and The Trial, is the name of the kitchen-maid (Johanna, Anna). Again and again one is struck, in these works held together by a hidden autobiographical web, by the way in which the meanings of the names Kafka gives to his figures revolve around certain obsessive ideas. Invariably significant, these names are typically the point at which several meanings intersect and interact, the ‘nodal points of numerous ideas’, for, as Freud said, ‘The work of condensation in dreams is seen at its clearest when it handles words and names.’1

1 – Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, tr. James Strachey, 3rd imp. (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1967) 340

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

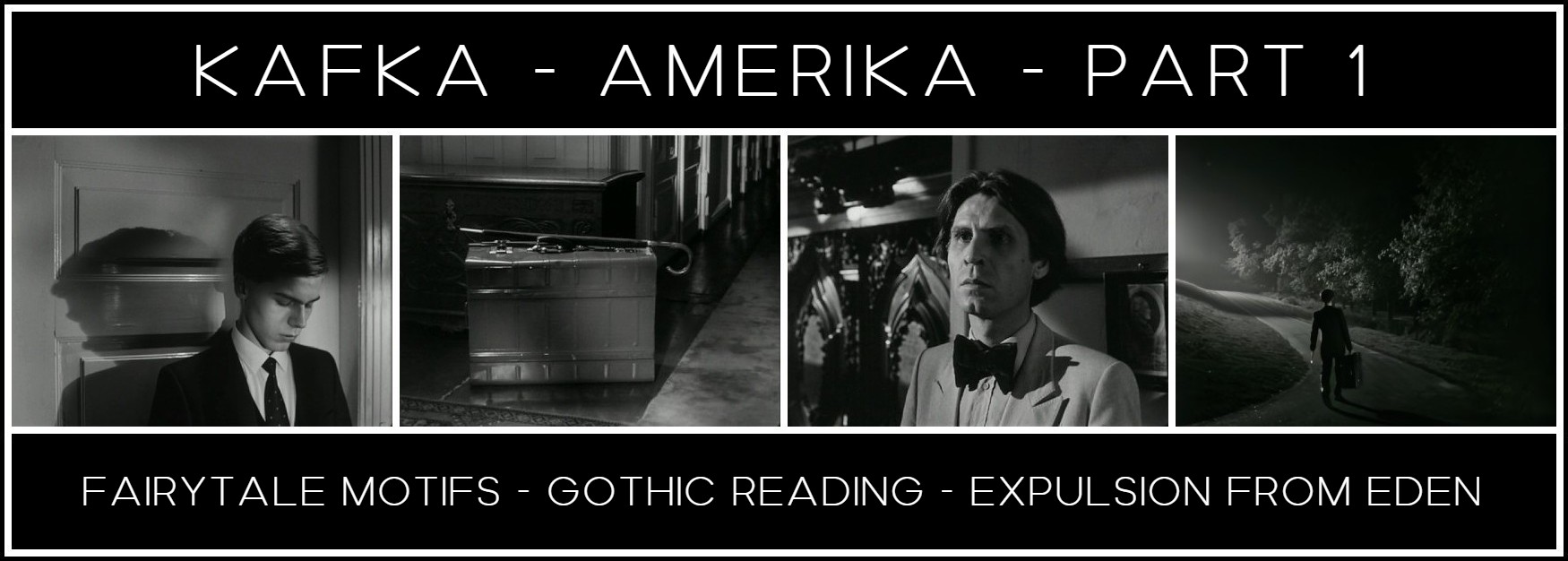

The ship, as the means by which Karl’s expulsion from paradise was effected, represents the reason for it. It is a floating Gothic world of infernal submarine vaults and caverns and dark rambling passages. By an invisible verbal bridge the ship is by implication a prison, since in colloquial German the word Kasten means both ship and prison. Above all, it is the locus of patriarchal authority, represented by the Captain, against which there is no appeal, so that he is in a similar position to the Old Commandant of the Penal Colony and the domestic autocrat [Kafka’s father] on whom they were both modelled, whose word was law. The symbolical parallelism is obvious enough: Karl’s descent into the bowels of the ship, down endlessly recurring stairways, along gangways (corridors) with countless doors and turnings, both replicates his fall and prefigures its further recapitulations in the novel. The realm he enters, the stoker’s realm, is an infernal underworld. In descending to it Karl is descending to a secular Hell. The Stoker’s realm, prison-cell, limbo (purgatory) and hell (inferno) in one, is a Gothic environment, with the stoker in his cell-like cabin very much in the power of the Captain.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

The Stoker stands for the devil in Karl; both his function and the umbrella which Karl leaves in the Stoker’s cabin can reasonably be interpreted in Freudian terms, hence his dismissal replicating Karl’s expulsion. The ship, connected by a verbal bridge with the nave of the Cathedral that ‘looms enormous in the dense haze’ from the balcony of Karl’s room in Onkel Jakob’s apartment, is not only the means whereby the sudden drastic change in Karl’s life is enacted; it also contains within itself much of the situational and spatial imagery of the novel. If it is as it were a secularization of the Cathedral nave, the skyscrapers of New York harbour are by the same token secularizations of the church towers of Gothic. It is ironic that Karl, living in a secular world, falls foul of a fossilized Old Testament theology that in the absence of God makes no more sense than do the moral codes in the penal colony of life following the death of their only begetter. Karl’s continual ups and downs, shown literally, represent his recurrent Fall and re-enact its cause (Freudian symbolism of stairways, Karl’s employment as lift-boy, cf. Robinson’s description of the lift-boys as ‘real devils’), are also, as it were, a pastiche of the preoccupation with the perpendicular that literary Gothic took over from Gothic Revival architecture.

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

Although Karl is being expelled and banished (a fairytale motif, the opposite of the usual Gothic motif of incarceration), the idea of imprisonment is present, both in the idea that applies to all three novels, that women are snares, the notion being as it were supported by the language, by the verbal bridge from Fall (Fall) to Falle (snare), and in the sense that the guilty conscience is a prison. The idea of incarceration is internalized: Karl is expelled into a prison of the mind, into the awareness of lost innocence, the ever-present idea of transgression, from which, disguise it as he may, he cannot escape, for the very feeling of yearning)was transgressive; Kafka, as often, uses the figurative word entsetzlich, ‘dreadful’, literally, to mean unlawful. The ship, as a Kasten (prison) carries with it, by extension, the idea of chastisement (kasteien, to chastise, to practise self-denial).

Danièle Huillet & Jean-Marie Straub, Amerika, Franz Kafka

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments